3

Including Youth and Family Voices as a Means to Help Adolescents Flourish

Presenters and discussion participants repeatedly mentioned that ensuring that adolescents, their families, and their caregivers are heard when creating policies and systems that affect them is essential to understanding how adolescents flourish in life. This chapter describes best practices for including such voices and perspectives as expressed by several national organizations, helping young people relate their first-hand experiences living with mental health conditions, and equipping adults to better support adolescents and help them feel heard.

BEST PRACTICES FOR INCLUSION

Leslie Walker-Harding, chair of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Washington and senior vice president and academic officer for Seattle Children’s Hospital, introduced the panel, saying that we know it is important to include youth and family voices, but we sometimes struggle with the best ways to do that. This section highlights different examples of including important voices from youth and families to bring valued experience into policy and advocacy.

Autism Speaks

Kelly Headrick, senior director of state government affairs and grassroots advocacy for Autism Speaks,1 introduced the mission of her organization,

___________________

1 See https://www.autismspeaks.org/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIma6ZwJ-86wIVGIvICh1Z5QyEAAYASAAEgIYoPD_BwE.

saying that they are dedicated to promoting solutions for individuals with autism and their families. Autism refers to a broad spectrum of conditions, she explained. Some consider their autism a gift, but for others it can sometimes be more severe, resulting in many challenges in daily life. Individuals with autism may be nonverbal, have trouble understanding people’s feelings or body language, and avoid eye contact. People may notice repetition with words or actions in individuals with autism, which for physical movements is called a “stim.” They also really depend on predictable routines, so there are added challenges when those routines are disrupted, such as during the current COVID-19 pandemic. The prevalence of autism has been increasing over the last few decades, which is likely a combination of more testing and environmental factors, Headrick said. In 2020, the prevalence had risen to 1 in 54 children on the autism spectrum, which is up from 1 in 166 in 2004 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

She explained the role of the advocacy team at Autism Speaks, which focuses on relationships among their community members and using their voices and stories to influence public policy. Some of their specific public policy objectives include:

- Federal autism research funding through the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and other federal agencies.

- Services and support coverage in private and public insurance plans (speech, behavioral, occupational, and physical therapies).

- Home and community-based services funding and regulation.

- Special education, including transition services into the school system, and then from there into adulthood.

- Personal safety and anti-discrimination.

- New employment.

They also coordinate with researchers and colleagues on relevant efforts. She explained the role of “advocacy ambassadors” who are grassroots volunteers selected to serve as contacts for their respective federal legislators. They are often either on the autism spectrum themselves or have a loved one with autism. Their main responsibilities are to develop relationships with legislators at the federal level, serve as a local media advocacy stakeholder, recruit other volunteers in their area for autism advocacy efforts, and report district activities and meetings as well as any outcomes to Autism Speaks staff members. “We have a goal of having an ambassador for every member of Congress,” Headrick commented. “Right now, we have about 350 ambassadors, so we are getting closer to reaching that goal.” To recruit these ambassadors, she explained that Autism Speaks conducts a formal application and interview process annually to select ap-

plicants for their roles for each congressional district. Selected candidates participate in a 90-minute training before starting, are given regular policy briefings, and hold monthly conference calls, but Headrick emphasized that these ambassadors do not need to be experts in the policy space. They are encouraged to focus on telling their own story and relating it to current policy advocacy goals. “We really strive to build this community of ambassadors, keeping them connected and trying to speak with a unified voice as much as possible,” she said. Ambassadors often comment on their experiences, especially the sense of satisfaction they get from influencing the decisions of elected officials, said Headrick. Many advocates are able to enhance advocacy skills for other future life activities and often include this role on their resume as evidence of leadership development.

National Organizations for Youth Safety

Tameka Brown, director of National Organizations for Youth Safety (NOYS),2 presented her organization’s work on using an interprofessional approach to engaging young people. The mission of NOYS, which Brown shared, focuses mainly on traffic safety, but it also includes other relevant issues such as injury prevention, substance abuse prevention, and violence prevention. She described interprofessionalism as a practice that is generally used in health care settings but works extremely well in many team settings because it gives value to each team member. She shared her own experiences working in a community-based mental health program and also a nursing school, which taught her that interprofessionalism is crucial for organizations that require a range of perspectives. There are four core competencies:

- Values and ethics for interprofessional practice

- Roles and responsibilities

- Interprofessional communication

- Teams and teamwork

Brown explained that any discussion of values and ethics should not only consider one’s own area of work, but also understand and incorporate other perspectives. With regard to roles and responsibilities, it is important to use your knowledge appropriately to “stay in your lane,” Brown said. Further, Brown noted that communication should always be clear and timely. In building teams, it is important to effectively build relationships to accomplish the stated mission.

NOYS, Brown said, typically engages youth between the ages of 13 and 23, which crosses two very different generations: Generation Y and Genera-

___________________

2 See https://noys.org/.

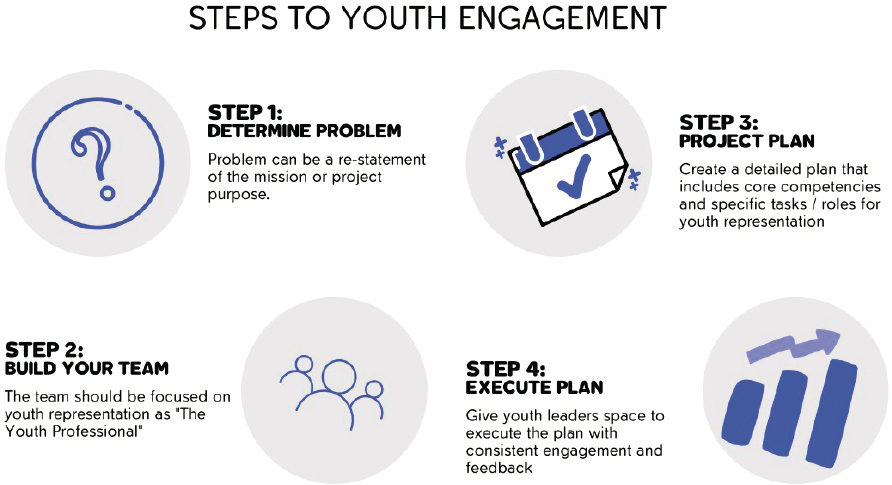

tion Z. A lot of outreach takes place through attending youth conferences around the country and by using social media and texting to engage a broader youth population. “Interprofessionalism requires us to view young people as experts and professionals,” Brown explained. Generations Y and Z respond well to being legitimately heard, so NOYS works to engage representatives of these generations at the table as experts in regard to their own safety and that of their peers. NOYS creates a space for them to guide the mission and the organization’s intended outcomes, giving them room to lead. Staff appreciation of the youth encourages meaningful youth engagement. At NOYS, youth do not feel that they are just taking up space at the table. Brown offered a four-step plan for organizations looking to intentionally use interprofessionalism to engage and maintain the empowerment of young people (see Figure 3-1).

To do this well, she explained, youth need to be given specific roles related to the project that will help guide them and measure their performance so they know they are successfully contributing. Emphasizing that they are needed and their input is valued keeps youth committed. Finally, she shared a list of things to do and things to avoid for this process. Things to consciously avoid include tokenizing young people as “others,” asking them to work for free, or having them work in silos. Instead, she said, organizations can design the roles given to youth strategically and intentionally and listen to what they have to say. Part of this process is about changing our minds as adults and seeing young people as valuable professionals who have something important to contribute.

Youth Thrive

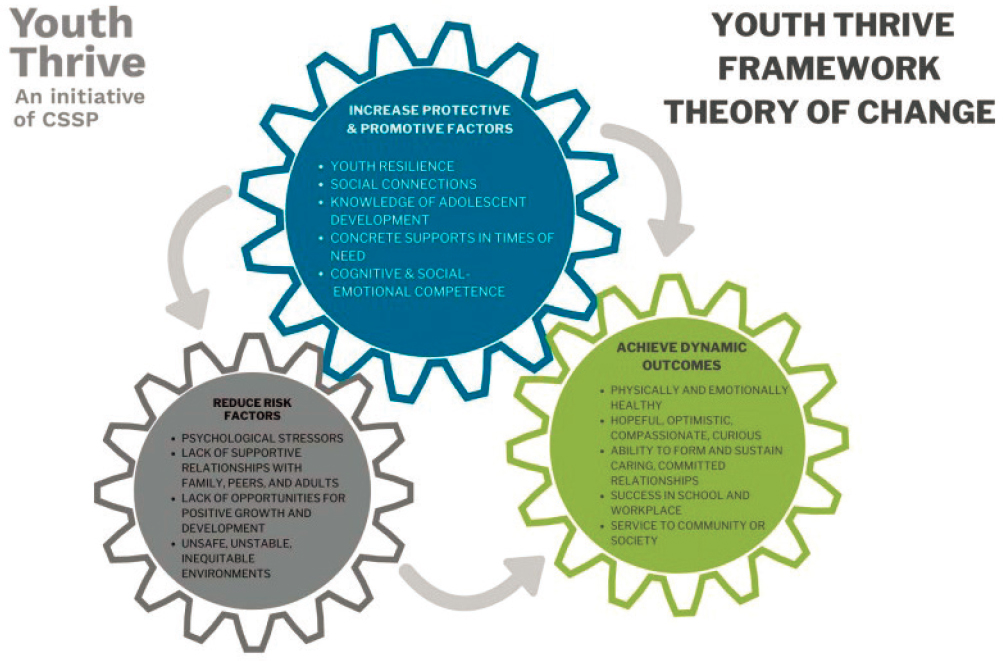

Francie Zimmerman, senior associate at the Center for the Study of Social Policy (CSSP), shared that Youth Thrive3 is focused on increasing opportunities for all young people. They base their work on a Youth Thrive framework (see Figure 3-2), which is built on a myriad of lessons synthesized across a variety of areas including neuroscience, development, and trauma research. They focus on youth from ages 9 to 26 years old and spend a lot of time on the protective factors in the top blue circle.

Differing slightly from other groups on this panel, Zimmerman said Youth Thrive spends most of their time concentrating on the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. They have identified several levers of change to help them implement their framework, but they found youth engagement and leadership to be one of the most powerful catalysts for making the system more responsive to youth needs. There is a myriad of roles that young people can fulfill, she said, and she encouraged the audience to think

___________________

SOURCE: Brown presentation, May 5, 2020.

SOURCE: Francie Zimmerman presentation, May 5, 2020. Youth Thrive, an initiative of the Center for the Study of Social Policy, https://cssp.org/our-work/project/youth-thrive.

beyond just having someone on a panel. Young people can review written materials, participate in a decision-making body, or act as site visitors and give feedback.

To give a more concrete illustration of the impact of youth on systems and the operational changes needed, Zimmerman presented two examples on how to leverage youth voices in order to change both practice and policy. Regarding practice change, she suggested giving power and authority to young people to develop case plans,4 which a number of states and jurisdictions have tried. This allows them to choose what they are working on, set their own goals, and choose who will participate. She said this process is developmentally appropriate and changes the level of investment and commitment for young people as their responsibilities increase. It also changes how staff members understand youth and the things that matter to them. Employing a case planning and implementation strategy with youth in the lead can help avoid some of the pitfalls that often arise when youth are ignored or misdiagnosed and labeled with a mental health or behavioral problem.

Another example Zimmerman presented related to policy change. In child welfare, there are often youth advisory boards that are asked to review proposed changes and give feedback. She described a group of well-meaning child welfare managers who proposed a reduction to the youth stipend that young people are given in independent living programs. They thought it would help them learn about self-sufficiency and manage their money better, but upon bringing this idea to the youth advisory board, they were met with strong disagreement. The advisory board said this policy would make it seem like young people were being punished for doing the right thing. Instead of reducing the stipend, the managers made a different decision and held budgeting workshops and created incentives for savings. This was a great example of young people challenging an agency’s plans and bringing about more meaningful policy change.

Regarding training, Zimmerman said that is probably where they find the most “aha” moments. Their staff training is co-led by youth with expertise in the child welfare system. The young people themselves have created a very comprehensive curriculum called Youth Thrive 4 Youth (CSSP, undated). They use engaging activities so youth can learn about adolescence and what they are going through, understand their strengths, and gain the tools needed to manage their lives and promote their own healing and health. For those interested in research and evaluation, she

___________________

4 Case plans are tools used primarily in the social work field to ensure children’s safety, well-being, and permanency. For instance, case plans are written documents required by law for children who are receiving foster-care maintenance payments (see https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/caseplanning.pdf).

described a validated and reliable assessment tool called the Youth Thrive Survey. It is designed to measure the presence and growth of protective and promotive factors as proxy indicators of well-being (CSSP, undated). The survey can be used to inform case planning and practice, as well as for evaluation and quality improvement efforts. The survey tool is currently free to use, she said, and all of the content has been vetted and found appropriate by young people. There is a webinar on CSSP’s website explaining how to use it.5

Finally, Zimmerman shared lessons learned from their experiences, the first being compensation for time. She suggested including those stipends in your budget at the very beginning design stage of a project. Beyond money, think about how to make youth participation worthwhile for them. Are there skills they can build in the process? Can they network? The same type of approach can be used here as when considering professional development opportunities for staff. Next, she said, changing the narrative is very important. Taking a step back to examine videos and reports to see how young people are portrayed can really inform how they will see themselves and how others will see them. Are youth being depicted as broken or described with a list of negative outcomes? Instead of carrying that narrative forward, she encouraged everyone to think about the inequitable policies and problematic environments that have led young people to such outcomes and shift the conversation toward discussions about changing those factors. Additionally, ensure that there aren’t barriers keeping young people from participating such as transportation, work, or other obligations. Lastly, she said, if you are asking youth for advice, take it. If they suggest changes, work toward carrying them out. If it is not possible, explain why you cannot make them and keep an active dialogue. Do not wait for the right time, Zimmerman said, because you will never feel quite ready to engage young people. Just figure out small steps you can take to get started. Getting a few young people involved will lead to an increase in interest and participation, and you can continue to build on successes. Start now, though.

Youth as Self Advocates

Matthew Shapiro, adult ally of Youth as Self Advocates (YASA),6 described the goal of his work as giving attention to the challenges of youth advocates and exploring how he can support them. He said that trusting that the young people he oversees have a voice of their own can be difficult, as is ensuring that their voices are heard rather than jumping straight

___________________

5 For additional information, see the CSSP website: https://cssp.org/our-work/project/youththrive/#survey-instrument.

into problem solving. Each year, Shapiro said, YASA decides what issues it wants to tackle, such as lack of transportation for young people with disabilities. They then work to make an advocacy plan for that issue. Shapiro reiterated the importance of the role of the adult ally, saying that knowing the ways the youth work together and their personal strengths and weaknesses are key. Adult allies have to know the youth to be able to lead them to success. Again, it is important to sometimes step back and remember that adults are there in a supportive role, but the ship needs to be steered by the young people. He also agreed with earlier speakers about ensuring that the youth are compensated for their work. He suggested thinking further about how young people can be given more leadership opportunities beyond just a board or advisory role. Mentoring young people in these types of roles is also a key component of being an adult ally, Shapiro noted. When he is working with young people, he always gives out his cell phone number and e-mail address and encourages them to reach out if they have questions about a particular challenge or transition that he has already experienced. What is it like, for example, to transition from high school to college to the work world? Or what is it like to go to college? Shapiro said he tries to make himself available to talk as young people try to navigate these new and different experiences that can sometimes be scary or frustrating.

Authentically Incorporating Young People

“What does it take for adults to be prepared themselves, to be engaged, and to promote youth voices?” Walker-Harding asked during the discussion and question and answer portion of the panel. Headrick replied that when thinking about an organization, it is important to help people understand the value in having youth and family voices represented and to maintain the mindset that those contributing their voices are experts in their own experiences. It is important to think about the culture that exists within that circle and embrace it as an organizing principle. Shapiro added a personal experience, saying that when he was a young person himself, it used to bother him when he was not taken seriously or invited to events just so that the organization could check a box. He explained that it was difficult to tell what his role was, when it was appropriate to speak up, and whether his input was valued or just politely acknowledged. Brown reiterated the point about communication, saying that if a person is making a suggestion or giving requested feedback, their recommendation should be validated in some tangible way. The key here is to stop “othering” young people, she said. It comes down to valuing their place at the table just as much as that of anyone else present. Zimmerman also added that it is important for adults to be mindful and respectful of boundaries that young people set. She shared that she has witnessed situations where adults ask very in-

trusive questions that young people were not ready to answer. In addition to adults being prepared for engagement, they also need to be trained to respect boundaries.

Walker-Harding also highlighted the importance of not tokenizing the voices of young people and asked how many voices are ideal to ensure a broader perspective is heard. Shapiro responded that within YASA, they always try to work in pairs. In addition to providing more than one perspective, it also gives young people additional support in a new setting and helps them lean on one another if needed. A final question was asked about whether consent forms were needed for youth to participate in the activities described by the panelists. Brown said that through NOYS, they always obtain consent from the youth professionals as well as their parents, especially because they work with people as young as 13. NOYS always focuses on cycling in the parent and keeping them in the loop, she said, but the bulk of responsibility for participating remains with the young person.

YOUTH PERSPECTIVES

Carlos Santos, associate professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, moderated a discussion of first-person youth perspectives on the importance of mental health supports. This section highlights thoughts from adolescents on what supports they need to thrive.

Detroit Flutter Foundation

DeAngelo Hughes, founder of Detroit Flutter Foundation7 and sophomore at Ferris State University in Michigan, introduced himself and described how he struggled with difficult feelings of grief at a young age after he lost his mother at age 13. Eventually, these feelings of grief made Hughes feel abandoned, unloved, and unsupported. As he got older, he began feeling lonely. These difficulties led him to launch the Detroit Flutter Foundation during his sophomore year in high school in 2015. With the help of the Future Project, the foundation began helping other youth struggling with loss and grief to find hope and comfort within a community.8 On Christmas Eve 2018, a suicide attempt put him in the hospital, and he was eventually diagnosed with bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. He explained that he had many personal challenges early in life but did not understand them because after his mom died, he was told it was just grief. Hughes shared that he faced many challenges following his diagnosis, including adjusting to various medications and their side effects

___________________

7 See http://detroitflutter.weebly.com.

8 For more on the Future Project, see http://thefutureproject.org.

and believing that his mental health condition now defined who he was. He felt that he had the label of a “crazy person,” and suffered losses in his personal life, even the ability to focus or concentrate. Many young people are diagnosed with mental health disorders in adolescence, he said, which can really affect the course of their education, their ability to work, and their relationships. He also commented on the stigma and heightened life difficulties associated with mental illness, especially for young people. In the year since his diagnosis, Hughes has tried a long list of medications and endured difficult side effects and mood swings, but he is finding what works. Many young people lack needed social support, he said, but also feel embarrassed seeking professional help or fear telling friends and family.

The power of peer-to-peer support is one of the main reasons Hughes started the Detroit Flutter Foundation. It is difficult to talk to someone and trust them, he shared, but peer-to-peer support can help adolescents discuss things that happen on a daily basis and help those with mental illness realize that there is a network of people similar to them. Many adolescents struggle with depression, yet too often adults say things like “You’re too young to stress,” Hughes emphasized. Nearly 43 percent of young people are diagnosed with depression, which can often lead to withdrawal from friends and family. This sometimes results in substance abuse or self-medicating with alcohol or marijuana. Depression can sometimes lead to suicide, he explained, which is the second leading cause of death in young people ages 12 to 24, rates for which have actually increased by 35 percent since 1999. Hughes said that these statistics really speak to him since he contemplated suicide over and over until he came to his breaking point and almost lost his life in 2018. Young people would greatly benefit from having a place to talk about things they are going through in their everyday lives, whether that be depression, loneliness, grief, or trauma. He said many youth feel more comfortable seeking out peer-to-peer models rather than professionals. He advised building more youth-led organizations to support adolescents with what they are going through.

Youth as Self-Advocates

Emily Ball, disability specialist from Manchester Community College and coordinator with YASA, began her remarks with an introduction to her personal life and challenges. She explained that she was born 3 months prematurely with a perforated intestine and hydrocephalus, which made early life complicated. As a toddler, she was diagnosed with cerebral palsy, which resulted in a string of 25 operations. When she reached puberty, Ball shared, she began experiencing anxiety symptoms. At the time, she did not recognize the symptoms as pointing to anxiety, but 13 years later at age 23, she was put on medication, and it has helped immensely. Ball was

additionally diagnosed with bipolar disorder at age 19. Following middle school, Ball experienced intense bullying, but her teachers and the adults in her school environment did not believe her, which led to several depressive episodes and tremendous emotional struggles. She experienced additional challenges after high school while trying to transition to college, but eventually was able to find stability once she was diagnosed as having bipolar II disorder. Bipolar II disorder is a mood disorder categorized by two phases, Ball explained. The primary phase is depression, but there are also phases of hypomania, which can include distress in certain situations, a decreased need for sleep, and a constantly high energy level. Medications are helpful, but highs and lows still occur on the road to breakthrough.

Ball learned through her experiences that her mental health condition played a major role in shaping who she is today. It was really difficult, she said, to identify her symptoms because they came during the formative adolescent years. She emphasized the importance of having a strong support system and a good medical care team to help navigate difficult moments.

Mental Health Support in Schools

Conor Curran, currently a high school student at Old Mill High School and president of the Chesapeake Regional Association of Student Councils9 in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, began his presentation by emphasizing the need for advocacy on behalf of school counselors. He said that youth need counselors to play less of an administrative role and maintain lower caseloads so that they can interact more with the students. Unfortunately, this is not possible with current school budgets, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curran also highlighted the mental health inequities affecting minority communities, noting the lack of bilingual staff needed to serve students for whom English is a second language. In Anne Arundel County, he shared that they have recently created a mental health task force comprised of school staff, counselors, and other relevant stakeholders in the county. Additionally, they have created a mental health teen advisory committee composed of two students from each high school in the district, with which the superintendent meets to talk about the inequities in the system that they witness. Curran believes that conversations would bring great benefits if they happened in school systems countrywide, noting that nothing will happen without meaningful communication.

Despite the complexities of mental health needs and conditions, he said, a student’s critical need is mostly to be heard, feel safe, and have a community that they can trust. Many students in the United States in places

___________________

9 See http://www.southriverhi.org/special-programs/chesapeake-regional-association-ofstudent-councils.

where the inequities exist do not have such support systems. Counselors and support staff are not able to be sincere and dedicate themselves to the students who need them because their caseloads are too overwhelming. Many students just do not feel heard, which Curran believes is a major flaw in the American education system. Additionally, COVID-19 is presenting a new set of challenges for students. Students usually spend 10 months of the year following a routine that involves daily school attendance, he said, but for the last 6 months, students have been at home instead of being in class experiencing normal personal interactions. This can be damaging to social development, especially for younger students. When the pandemic and stay-at-home orders first started, it was difficult even for counselors to connect with students remotely because of insurance restrictions. Luckily, those have recently been lifted, but it can still be difficult for students and support staff to personally connect like they normally would do during the school day. The moment in which we find ourselves illuminates the need for schools across the country to ensure that their students have adequate resources and equal access to education, whatever form that might take for the near future. Some students do not have the access to technology so vital to distance learning, Curran said, forcing them, for instance, to share one laptop with other school-age children in their family. This can be incredibly stressful, since students feel that their grades and academic future are at stake. He suggested that school systems nationwide implement a pass-fail grading system during the pandemic so that students can focus on staying healthy and safe. School boards should also provide more funding for access to technology and methods for support staff and counselors to reach out to students while they are at home. “All means all,” he noted, emphasizing the need to work together through this and have faith in society to do what is best.

Helping Adolescents Feel Heard

Santos noted the stigma often related to mental health and asked for the speakers to comment on how they might advise other youth in seeking support. Hughes first suggested talking to a parent, and if not comfortable with that, a student can try a school counselor. He shared that he developed a great relationship with his high school counselor, and that just having someone to talk with who supported him really helped him get the resources he needed. Ball said that if you feel something different going on that you have not noticed before, don’t assume it is just part of your personality as she did. Seek help from your parents or a doctor, she said. Curran echoed both responses, saying it is all about reaching out for help from caring people who want the best for you.

In a follow-up question, Santos asked if there were any suggestions on how schools can better support student mental health. Ball said that giving proper attention to the troubles she experienced in high school could have taken up a school psychologist’s entire day, so increasing the length of sessions with school counselors beyond 30 minutes each week would help greatly. For school districts in his home state of Michigan, Hughes suggested hiring additional social workers. In Detroit, there are social workers who work with kids with individualized education plans, he said, but the kids without that formal document have no one to talk to when they need it. There is a need for more social workers in schools just to be available for whoever needs them. Curran agreed as well, mentioning that in Maryland, the school maintains one “pupil personnel worker”10 in every high school. Since schools are fairly large, though, it is extremely difficult for that individual to interact with every student when there are 2,000 students. Hughes emphasized this point as well, saying that the system can’t allocate available social workers or psychologists only for kids who are right on the edge and ready to break. Instead, these counselors and support staff should be available further upstream for kids to access before their problems become so dire.

Suggestions from Speakers for Adults, Schools, and Organizations

To further the discussion, Santos also asked how agencies and policy makers could engage young people in their advocacy work. Ball suggested that agencies put out youth-friendly language tip sheets on mental illnesses. Personally, she shared, she did not know much about her mental illness when diagnosed, so she had to dive into really technical medical language that was difficult for a 19-year-old to understand. To address this, those who produce such resources might want to imitate the speaking style of youth in the future. Hughes agreed that language is a big factor, and that change has to start with the policy makers. Once they change it, he said, it might trickle down and help remove the stigma. If more people are talking about it, more resources will be out there for those who need it. Curran added that in his district, the board of education has included a fully voting student member. In Maryland, student voices are being heard, he said, because they have a place at the table with adult members where budgets and policies are created, allowing them to be part of the process.

Santos asked how school systems can train students to act as suicide prevention peer counselors or social workers. Ball offered a personal story, saying that following the death of a student in her high school, students cre-

___________________

10 Pupil personnel workers are specialists trained to assess student needs, serve as student advocates, and act as a motivating force in removing barriers to student achievement. For more information, see http://marylandpublicschools.org/about/Pages/DSFSS/SSSP/PPW/index.aspx.

ated their own suicide prevention organization called “Rachel’s Friends,” which focused on uplifting others and creating activities to help students feel engaged and connected. Hughes elaborated on suicide support, emphasizing that the language around suicide has changed. Instead of asking tangential questions (such as “Are you going to do something stupid?”), current protocol calls for directly asking if people are thinking about hurting themselves. He also suggested bringing more awareness to suicide prevention and noted that while in high school, he helped host panels and assemblies, realizing that many kids would stay afterward to talk to speakers because they had similar feelings. As a result, they were able to bring in more resources, set up activities after school, and address some of the issues with which many students struggle. Curran said that his school system worked with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention to administer its Youth Mental Health First Aid training. This allows youth to have difficult conversations with a peer to make sure they are safe and direct them to a professional so they can take further steps. He highlighted the training’s great value, having used it several times, and he suggested scaling it up to make it more widely available. Currently the training lasts 8 hours, so he acknowledged that it is not a great fit for the school curriculum, but they are working on condensing it to be more accessible to high school students.

Building on these suggestions, Santos asked about what type of behavioral supports around mental health and emotional well-being would be useful for youth outside of the school environment. Hughes first emphasized the importance of youth-led organizations out in the community. It involves not just going to a facility for a counseling session, he explained, but maybe also featuring resources on mental health at recreation centers where youth already spend time. Ball added that teaching future students of social work how to work with children and youth is quite important. Curran offered another idea, suggesting that communities or organizations could host community events, bringing in groups and tools that promote mental health awareness and featuring other organizations or advocacy groups to discuss the importance of mental health with the community.

How to Leverage Professionals

Santos asked how professionals such as those present at the workshop, could better support youth. Ball recommended that anyone who works alongside youth with disabilities should go through a mental health training focused on youth experiences. Hughes said that most young people in these situations really just need someone to listen. Young people are often tuned out, both at home and in other settings, so having the ear of someone willing to listen to their concerns is critical. They do not have to respond with solutions, he said. They just have to listen and communicate that they hear and understand you.

Centering Youth

Santos asked the panelists why it is often so challenging for youth to be heard. He noted that in some ways, we are more connected in the social media age, but in other ways, it is harder to find community. Ball said that having experienced so much turmoil prior to her diagnosis, she felt great embarrassment that hindered her from admitting that she had emotional disabilities. Curran added that it requires you to put yourself in a very vulnerable position, which can make it difficult to build a community, especially in a group of people you do not know. He added that his school system in Maryland started a restorative justice practice called “Community Circles,” which aims at building those relationships and getting to deeper questions.11 Santos also asked about the COVID-19 pandemic, and how the illness itself and numerous downstream effects such as school cancellations are affecting the mental health of youth. Hughes replied that it is affecting youth on a huge scale. The quarantine orders make it impossible for youth to see their friends, much less their usual counselors. While they can talk on the phone, the level of privacy is not the same, so many might feel that they are not able to have safe conversations. Additionally, people are losing family members while simultaneously dealing with mental illness, and many are left to grieve in isolation. People have not been able to get away and tap into their usual coping mechanisms and activities to help process feelings. Curran agreed that many students are negatively affected, due to being unaccustomed to being at home all the time and not having their normal social interactions with friends and teachers at school. When they do see other people, everyone seems scared, which impacts how you see society.

Finally, Santos asked for advice on the best ways to encourage young people who might resist seeking mental health services to accept that this is what they need. Hughes agreed that it can be a challenge, admitting that he had experienced this himself. When he first began visiting a therapist in high school, he initially refused to open up and share things that were bothering him, but he learned that it is helpful to be able to talk to someone like himself who is a young person of color with similar experiences, which helps build that trust. Curran added that trust depends on feeling safe to be vulnerable, which is easier with someone who knows what you have gone through on a personal level, Without this commonality of experience, it is difficult for a counselor to be sincere. Santos wrapped up the discussion saying this is really a call to arms involving rethinking how we can engage youth in various efforts and exploring what needs to be done differently.

___________________

11 For more on Community Circles, see http://www.centerforrestorativeprocess.com/teaching-restorative-practices-with-classroom-circles.html.