3

Developmental Origins of Children’s Mental Health Disorders

The third webinar in this series was led by Pilyoung Kim, director of the Family and Child Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of Denver. Kim reviewed some of the scientific advances in the developmental origins of children’s mental health disorders, especially in relation to their environment and their experiences with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). The sixth and final webinar featured Erin C. Dunn, assistant professor at the Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, who made a case for identifying sensitive periods in development linked to greater risk for depression and other brain health challenges among children and adolescents and how using shed teeth could possibly do so (Davis et al., 2020). This chapter first defines ACEs and their associations with mental health challenges in children, then outlines the biological mechanisms responsible for these associations through various developmental stages of a child’s life, discusses the reasons for studying timing of an exposure and ways of measuring when a child may be most affected. It concludes with discussing opportunities for intervention.

ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES AND MENTAL DISORDERS

Kim began saying that, historically, research often focused on individual adversity factors people may have experienced, such as maltreatment or neglect, but more recently, the concept of ACEs has emerged with a growing research base. This concept focuses instead on the many different

adversities people experience during childhood and the ways in which they relate to mental disorders later in life.

Defining Adverse Childhood Experiences

To understand how these ACEs relate to various mental disorders, it is first necessary to define them and understand what type of experiences could be categorized as ACEs. Kim explained that ACEs are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood and can include 10 different negative experiences across categories of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction (see Figure 3-1). In one of the first and largest studies of ACEs done by Kaiser and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from 1995–1997, researchers found that nearly two-thirds of adults surveyed reported experiencing at least one ACE, and most who reported one reported multiple (Felitti et al., 1998).

Almost one out of six surveyed reported experiencing four or more ACEs during childhood, Kim explained. This is concerning because the relationship is dose-dependent, meaning that the experience of more ACEs exerts a greater effect on things like health, behaviors, and life potential for adults. This can include things like obesity, diabetes, depression, smoking, alcoholism, lower graduation rates, and lost time from work. Additionally,

SOURCE: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2013. The Truth About ACEs. Used with permission from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

the effects of ACEs encountered early in life go even further than poor health. According to the CDC, at least five of the top 10 causes of death are associated with ACEs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019).

Secondary Poverty Interactions

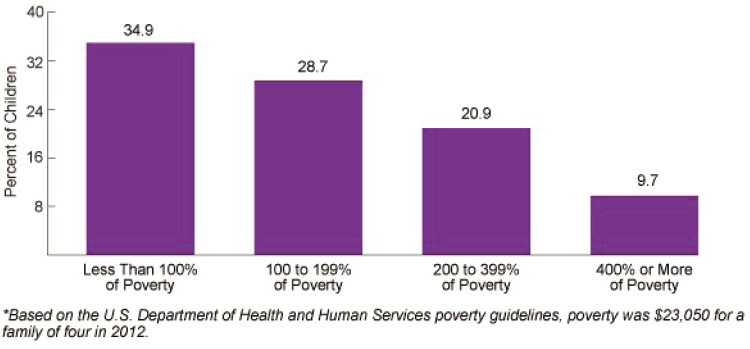

Similar to other disparities being uncovered due to systemic failures, research also shows a somewhat unsurprising interaction between poverty and ACEs. The federal poverty level (FPL) for a family of four in the United States in 2019, Kim said, was $25,750. Looking at 2016 data, 19 percent of children were living in poverty and another 22 percent were living at twice the FPL (around $50,000 per year for a family of four). These two groups are collectively classified as part of the low-income category, and they capture 41 percent of children living in the United States (Jiang and Koball, 2018). As an age demographic, Kim explained, children younger than 18 are most likely to experience poverty compared to adults and seniors over 65 years of age. This is additionally concerning because children living in poverty are more likely to experience ACEs than their wealthier counterparts. Data from the CDC and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) show that nearly 35 percent of children living in households earning less than 100 percent of the FPL experience two or more ACEs from birth onward, compared to 28.7 percent of those living between 100–200 percent of FPL, and just 9.7 percent for those living at 400 percent of FPL (see Figure 3-2).

Kim went on to describe the high level of chronic, multiple risks that children are exposed to when living in poverty compared to children living in wealthier households. Quoting a review paper, she noted that income and socioeconomic status tend to differentiate people systematically, which affects the quality of their environments, and often dictates the levels of pollution, toxins, crowding, noise exposure, and exposure to violence (Evans and Kim, 2010). In addition to these physical effects on living conditions for people in lower socioeconomic statuses, she said, people in these conditions often have more psycho-social risk factors and worse relationships with family members and their community. When both types of these risk factors come together—especially for children—health outcomes can worsen as well. This was clearly demonstrated by examining the number of specific risks children were exposed to by being exposed to poverty (Evans and Kim, 2010).

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015.

STRESS PATHWAYS IN THE BRAIN AND IMPACTS ON DEVELOPMENT

While the linkages seem to be clear and increasingly well established between stressful environments and child development, Kim also expanded on why childhood adversity leads to negative mental health outcomes and the things that happen in the body such as the development of stress pathways in the brain and the neurobiological mechanisms that affect a person across their life course.

Overview of Biological Mechanisms

Stress and adversity affect development in the brain, Kim said, namely in the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex, which are the signature brain regions involved in emotional and self-regulation. If someone is living in an environment that is always stressful, the amygdala is constantly activated, she explained, which over a period of time leads to hyperactivity of the amygdala. This hyperactivity results in hypervigilance, where the brain is always on and conducting threat assessments so it can protect itself from negative cues. Clinically, this is also linked to high levels of anxiety. Normally, when the amygdala is activated, the rest of the brain helps to evaluate what an appropriate reaction to the negative cue should be. The brain takes information from past experiences and the current context and makes a decision. For individuals exposed to chronic stress, Kim added, the exposure to stress can result in ineffective emotional regulation.

Repeated exposure to stress leads to synapse loss and changes in dendritic branching of neurons, leading to impaired morphology and functional connectivity in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, Kim explained. These become early neural markers for emotion dysregulation and are commonly observed in psychiatric disorders across the life course (Klumpp et al., 2014).

Prenatal Period

Now that we have such advanced technology, Kim said, researchers can track brain activity in the womb. During the third trimester of pregnancy, the brain is forming 40,000 synapses per minute. Even before birth, the baby’s brain is already developing programming so that it can be ready to detect threats from the environment. During the first year of life, the brain volume subsequently increases by 100 percent. Biological systems like these that have such rapid developmental changes are also especially vulnerable to adversity.

Research has found that maternal anxiety, inflammation, and the presence of cortisol during pregnancy are associated with altered amygdala and prefrontal cortex functionality in newborn babies. Additionally, maternal depression during pregnancy has been associated with decreased amygdala functional connectivity with the prefrontal cortex in newborns (Posner et al., 2016), and lower white matter organization in the right amygdala (Rifkin-Graboi et al., 2013). This suggests a prenatal transmissibility of vulnerability to depression. Such exposure to adversity during infancy and this period of rapid brain development can lead to more hyperactivity in the amygdala of the infant. Even just being exposed to more angry voices can have this effect, Kim noted. To demonstrate the point, she referenced a 2013 study by Hanson and colleagues that measured brains of young children across the socioeconomic spectrum (Hanson et al., 2013). They found that children living in households with lower socioeconomic status had slower trajectories of brain growth compared to other income levels and lower volumes of gray matter.

Childhood and Adolescence

Research has also tracked the impacts of poverty on brain development during childhood and adolescence, said Kim. She referenced a 2015 study which demonstrated that among lower-income households, even small differences in family income corresponded to relatively large differences in cortical surface area, which was further linked to poor cognitive development among children (Noble et al., 2015). These data indicate that brain structure is influenced most by income level among the most disadvantaged

children. A similar study found that low family income levels were associated with a lower level of organization in the white matter involved in cognitive and emotional function for children at age 9 (Dufford and Kim, 2017). This same association was found for those children exposed to multiple stressors such as violence, family conflict, separation, and housing problems.

As children progress into adolescence, their brain begins to change. The prefrontal cortex is not quite mature enough in children to down-regulate the amygdala when needed, Kim explained, but that typically switches once they reach adolescence. For children who experience maternal deprivation, however, this development is accelerated. When compared to children in a control group, those who had a history of early adversity had brain structure more similar to adolescents with more mature connectivity (Gee et al., 2013), but the communication between systems is not effective enough, so these children still have higher levels of anxiety. Studies have also corroborated this developmental period as children age. Shaw and colleagues found a negative correlation between intelligence and cortical thickness in early childhood, shifting to a positive correlation in late childhood (Shaw et al., 2006). This plasticity is even more pronounced in children with high levels of intelligence, who typically have delayed development of the prefrontal cortex and try to first take advantage of all input from the environment before devising a reaction.

Long-Term Impacts into Adulthood

Childhood is a sensitive period of development, Kim said, and research now shows that exposure to socioeconomic disadvantages during childhood is associated with poor health outcomes in adult life. Cohen and colleagues found that socioeconomic status exposures during childhood can be predictors of all-cause mortality, as well as specifically cardiovascular mortality and morbidity (Cohen et al., 2010). This comes at a cost to society too, with aggregate costs of childhood poverty estimated in 2008 at $500 billion each year (Holzer, Schanzenbach, and Duncan, 2008). Authors also estimate that each year, childhood poverty reduces productivity, raises the costs of crime, and raises health expenditures, all by more than 1 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product.

Kim presented the findings of a 2005 neuroimaging study in which 49 participants were followed from ages 9 to 24 years old. Half of the participants lived in poverty throughout childhood, but many moved out of poverty by the age of 24. During the study, participants were shown images intended to elicit a negative emotional response and were instructed to either “maintain” by naturally reacting, or “reappraise” by voluntarily regulating emotions. By following this emotional regulation paradigm,

researchers were able to observe the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, areas of the brain that are active in emotion regulation. Compared to the participants who did not grow up in poverty through the age of 9, participants in households below the poverty line displayed lower activity levels in the prefrontal cortex. In the same participants that displayed lower levels of prefrontal cortex activation, a higher brain activity pattern was observed in the amygdala, which could be responsible for their ineffective regulation of emotions. Additionally, the study found an association between lower prefrontal cortex activity and exposure to multiple stressors from ages 9 to 17 years old, Kim explained. The results yield a significant association between childhood income and brain activation in adulthood, while current adulthood income was not noted to have an impact on neural activity. The study’s findings further support the association between childhood adversity and lifelong emotional regulation (Phan et al., 2005). Kim has conducted further research on the impact of childhood income on the structure of the brain, yielding similar patterns emphasizing the association between childhood income and the increase in exposure to multiple stressors which leads to lost surface areas in the adult brain (Dufford and Kim, 2017).

Adaptation and Vulnerability

In summary, Kim explained that this neural embedding of childhood adversity contributes to producing mental health disorders. Multiple stressors, in other words, lead to altered morphology, function, and connectivity in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, which in turn increase the risks for emotional and behavioral dysregulation across a person’s life course. Childhood being such a sensitive period, the opportunities for preventing many of these downstream effects lie in reducing early-life adversity. Modifying the environment through interventions can play a role because the timing and duration of these ACEs make a difference.

Kim provided examples of this modification, saying that the number of years living in poverty between ages 11 and 18 were associated with lower amygdalar volumes and a more negative association with resting-state functional connectivity in emotion regulation networks (Brody et al., 2017). For those whose parents participated in a “supportive parenting” intervention, though, this association between poverty and amygdalar gray matter volume was not present (Brody et al., 2019). At age 25, in other words, these individuals had similar emotional regulation function as those who did not live in poverty during adolescence. The timing and duration of exposure are also factors to consider.

When addressing adverse exposure, Kim presented two models: the biological embedding model and the accumulative model. Throughout her presentation, Kim referenced the biological embedding model perspective

the most, which focuses on the influence of risk exposures during sensitive periods such as the prenatal period and also brain development as a means to inform interventions. One limitation of this model is not considering life experiences outside of the sensitive period (Finch and Crimmins, 2004; Hertzman, 1999). Accumulative models also show that early adversity can lead to modifications in an individual’s later environment and behavior. Kim said, “Adversity begets adversity,” noting that a consequence of prolonged exposure to adversity and the resulting accumulated chronic stress on the body can lead to more severe damage in neurobiological systems (Kuh, Ben-Shlomo, and Ezra, 2004).

While research has now demonstrated the plasticity of the brain, its adaptiveness or maladaptiveness can determine what kinds of pathways are being created. The allostatic load model says that the wear and tear on the body from chronic stress causes negative disruptions of brain structure and function that are precursors of later impairments in learning and behavior, resulting in chronic physical and mental illnesses (McEwen, 2012). For example, Kim explained, if children develop hypervigilance in response to discriminatory threats in their living environment, a focus on reducing their hypervigilant responses will not be helpful since it is a response to the threat. The active calibration model of stress responsiveness extends this theory of the stress-health relationship, stating that these tradeoffs between response to threats and costs to mental and physical health are actually life-stage-specific, adaptive decision strategies in the allocation of behavioral and physiological resources (Ellis and Del Giudice, 2014). Kim explained that this series of decision nodes can optimize the individual’s adaptation to and resulting fitness for a particular environment, whether threatening or nurturing. The two models are only partially complementary and sometimes may support different approaches to intervention. The models should be applied on a case-by-case basis when developing interventions to address the developmental origins of mental health disorders in targeted individuals.

IMPACT OF STRESS DURING PERIODS OF DEVELOPMENT

To begin her presentation, Dunn commented that boys and girls experience similar rates of depression as young children, but once they begin approaching adolescence, rates for girls increase disproportionately. This gender difference is associated with numerous downstream consequences including anxiety, suicide, or other comorbidities. Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide, she said, so finding ways to prevent it is key, because once depression does emerge, it recurs very frequently

(three-quarters of people experience relapse). The time of onset is significant, she continued: We know that 20–40 percent of people with a major depressive disorder experience the first onset before the age of 18. She argued, based on these empirical data, that there is a need to better understand the etiology of this disease process so that we can do a better job of targeting prevention and intervention.

In its efforts to target policies and interventions appropriately, the mental and emotional health field, Dunn said, generally tends to focus mainly on who is most at risk. She noted that we spend a lot of energy determining what types of therapies to recommend and where these services should take place. Increasingly, the field has also started to consider how therapeutic services are delivered, face to face, virtually, or otherwise. Dunn explained that her work has really focused more on the still much neglected question of when interventions should occur. This type of research can help identify better ways to prevent mental health problems in children because it could enable us to use interventions in ways that make the most effective use of limited public health dollars by tailoring them to life stages when experience matters even more.

Varying Theoretical Models to Describe the Relationship between Adversity and Depression Risk

There are at least four life course theoretical models in the literature that explain how exposure to childhood adversity increases risk of depression, Dunn explained. Each of these models also points to different opportunities for intervention. The exposure model simply suggests that people who are exposed to adversity have an increased risk of depression compared to people who are unexposed. When we have data that maps to the exposure model, this suggests, we can intervene at any time by identifying people with lifetime exposure. The accumulation model suggests that there is a dose-response relationship between adversity and the risk for depression. If the data are more consistent with the accumulation model, then we should intervene early to prevent accumulated exposure. The recency model suggests that risk for depression following exposure to adversity is elevated for a short time right after the exposure, but this risk disappears over time. The recency model urges quick interventions, but also acknowledges that children may naturally recover over time without intervention. Finally, the sensitive period model suggests intervention during or shortly before sensitive periods of development. These sensitive periods constitute windows of vulnerability in which the risk of depression is more acute, but conversely they can also be windows of opportunity where protective factors might be

just as beneficial.1 Dunn’s goal is to identify precise recommendations about when to intervene, using a high-resolution time scale so that interventions can be targeted and uniquely timed for greatest efficiency and effectiveness in preventing depression and other brain health conditions.

To achieve this goal, there are four primary unanswered questions remaining that Dunn’s research group is seeking to answer. Finding the solutions will be key to understanding the mechanisms that underlie the risk of depression. These remaining questions include:

- When are the developmental periods of greatest vulnerability to depression following exposure to stress and adversity?

- What matters more: exposure, accumulation of exposure, recency of exposure, or developmental timing?

- How does exposure to stress and adversity during sensitive periods increase the risk for depression (in other words, what are the biological mechanisms)?

- Do genes regulate the occurrence of sensitive periods, and if so, which genes are involved, and do these genes play a role in shaping the risk of depression?

Importance of Timing of Exposure

Dunn described a retrospective study of young adults in which respondents were asked whether or not they had been exposed to sexual or physical abuse and how old they were when it first happened. This information was used to calculate the odds of experiencing elevated depressive systems in adulthood, and Dunn et al. found that generally people exposed to physical abuse had higher odds of depressive symptoms compared to those who were never exposed to abuse. On the other hand, when they compared the timing of exposure, they found that children who first experienced physical abuse as preschoolers had a 77 percent higher risk of depression compared to youth who were first exposed as adolescents. Children who had been sexually abused faced increased odds of depression compared to those who were unexposed, but after examining timing differences, they found that those respondents first exposed to sexual abuse in early childhood experienced a 146 percent increase in the odds of suicidal ideation compared to respondents who were abused as adolescents (Dunn et al., 2013). Other

___________________

1 These life span theoretical models are summarized here: Dunn, E.C., Soare, T.W., Raffeld, M.R., Busso, D.S., Crawford, K.M., Davis, K.A., Fisher, V.A., Slopen, N., Smith, A.D.A.C., Tiemeier, H., & Susser, E.S. (2018). What life course theoretical models best explain the relationship between exposure to childhood adversity and psychopathology symptoms: recency, accumulation, or sensitive periods? Psychological Medicine, 48(15), 2562–2572. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6109629.

studies she shared that found measurable biological effects in response to adversity also emphasized that the timing of the exposure really mattered. If we had just looked at exposed cohorts versus unexposed cohorts, we would have completely missed important results, she said.

As an example, she summarized the results of a study examining the time-dependent effects of childhood adversity on DNA methylation, which is a type of epigenetic mechanism known for decades to affect gene expression and has been posited to explain how childhood adversities “get under the skin” to increase subsequent risk for depression. For one of the first times, her study revealed that the effects of childhood adversity on epigenetic patterns were not simply due to the presence versus absence of exposure. Instead, the biggest driver of epigenetic changes was based on when the adversity occurred, with the period from birth to age 3 emerging as a sensitive period serving as a precursor to further epigenetic changes at age 7 after continued exposure to adversity. (Dunn et al., 2019).

Current measures of exposure have serious limitations, Dunn commented. Many rely on retrospective reports that have a tendency to introduce different types of recall bias and susceptibility to interview quality. Conversely, she said, prospective reports also have problems, including the unawareness of parents to some exposures and parental reluctance to share this information.

Using Teeth as a Biomarker

To address the limitations of current measures of childhood adversity and potentially provide new information, Dunn posed this question: “Can children’s shed teeth serve as a biomarker of ACE exposure?” She referenced a conceptual model exploring the use of this strategy to prevent mental illness by targeting interventions during sensitive periods of children’s development (Davis et al., 2020). Starting in prenatal development, she explained, ameloblasts (the cells that form enamel) lay down enamel in daily intervals. As that matrix of enamel is formed, a record of that process is permanently recorded in the tooth, a physical trait humans share with other mammals and even with trees, which mark their age with growth rings. We also know that teeth record insults or disruptions that occur during their development that result from illness, malnutrition, and heavy-metal toxicity.

To date, most of the research on teeth has focused on physiological stressors to the almost complete exclusion of work that examines psychosocial stressors. The existing literature, which studies primates, suggests that teeth can capture psycho-social stress. A range of studies in gorillas and monkeys have measured stressors such as separation from mothers, caregiving disruptions, or separation from social groups, and these studies

found evidence of that social disruption in teeth. Additionally, human studies have examined the associations of environmental toxicants with mental health outcomes. These stressors recorded in teeth have been shown to predict neuropsychiatric risk. Given all of this information, Dunn said that teeth may provide enormous and unique opportunities for primary prevention of mental health disorders. She said each time point when teeth are lost represents an opportunity to intervene. The first chance would be around ages 5–6 (when teeth are naturally falling out), the second at ages 10–12 (when kids often have teeth removed for orthodontic work), and a third during wisdom teeth removal between ages 18–22. To marry all of these concepts and identify whether teeth can in fact be used as a powerful new biomarker, Dunn said she has become the “Science Tooth Fairy.” Her group recently launched a study in December 2019 at Massachusetts General Hospital called the STRONG (Stories Teeth Record of Newborn Growth) study, which is studying kids of moms who were pregnant during the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.2 In addition to studying this specific population, she said that they are also trying to better understand the dosing of exposure and answer conceptual and empirical questions, as well as piece together feasibility studies to examine what the social and cultural factors will allow for a more frequent use of teeth in research.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR INTERVENTION

Neal Halfon, director of the UCLA Center for Healthier Children, Families, and Communities, led the discussion with Kim on opportunities for intervention to try and offset some of the adverse consequences of ACEs for children and families. Following a question on recommended clinical and societal interventions, Kim stressed that these findings highlight the importance of early life intervention, especially in the family and environment. There are usually multiple stressors involved, though, and even identifying a positive, effective intervention for one source of adversity is a challenging task. She suggested first identifying the individuals who are at higher risk and then designing interventions to be as effective as possible for those populations that cut across multiple systems such as family, neighborhood, and society.

While the associations between exposure, health, and brain development are becoming clear, the research identifying the types of interventions that are most successful and the populations in which they work best is unfortunately much less uncertain, Kim said. Current neuro-imaging literature lacks the depth sufficient enough to distinguish between cultural differences and provide specific brain evidence for different racial or ethnic groups. Nonetheless, she noted, a broad ongoing effort to include more

___________________

2 For more on the STRONG Study, see https://teethforscience.com.

diverse groups of children is under way, so hopefully in the future, these nuances will gain greater clarity. Similar to cultural differences, varying differences exist between the challenges facing rural and urban populations. Kim referenced a study that examined challenges encountered by children in urban and rural poverty settings. One risk factor identified in urban settings is high levels of mobility in the family versus the geographical stability of children in rural settings. The unique challenges of both cultural and poverty differences are understudied, Kim said, and should be better understood. While neuro-imaging literature has successfully contributed to identifying mechanisms that link stressful experience and maternal health outcomes as well as those that link sensitive, region-specific developmental periods to adversity exposure, further research could help identify risk factors related to culture and demographics, as well as factors that may protect children from risk.

Another participant asked about individual resilience and was wondering whether any existing research has explored why some children faced with many ACEs in early life go on to become very successful and healthy as an adult. Kim acknowledged this, saying that it is an area that certainly needs more study, as there is huge individual variability. Just because you have encountered adversity as a child, she said, does not mean you are destined to have mental illness later in life. She added that brain plasticity plays a big role and can change in response to different things that happen even while the ACEs are present. For example, children may move out of poverty after a period of time or may have a strong network of supportive relationships in their life, so their brain may look different than others in similar situations who do not have those advantages. In similar ways, Dunn added, the COVID-19 pandemic may help us to develop more policies at the societal level to help share understandings of social determinants of health in a way that can promote child mental health and well-being.

Despite the serious lack of attention given to this area, Dunn presented an encouraging example, describing the Brain Health Initiative in Florida. In response to the state’s national ranking in relation to mental health issues—50th in per capita spending on mental health support and 44th in the number of available mental health providers per capita (Florida Behavioral Health Association, 2018)—the Brain Health Initiative has sought to identify, develop, and implement interventions across the life course to optimize brain health. They are working to study the role of genes and lifestyle factors in shaping brain health, as well as to understand how certain interventions can reduce the risk of brain-related diseases and promote optimal brain health. Once they determine how all of these factors impact development, they can more effectively identify the right time for intervention in order to have the best and most valuable impact.3

___________________

3 For more information, see www.brainhealthinitiative.org.

This page intentionally left blank.