5

Policy Responses to Support Children’s Mental Health

The fourth webinar in the series featured three speakers from different backgrounds who focused on the best ways to generate a comprehensive policy response to children’s changing mental health needs. Benjamin Miller, chief strategy officer at Well Being Trust, Alex Briscoe, principal at California Children’s Trust, and Nathaniel Counts, senior vice president of behavioral health innovation at Mental Health America, emphasized the downstream negative effects of the current mental health epidemic, highlighted ways to integrate children’s mental health more sustainably into the overarching system, and proposed ways to change methods to transform outcomes. Neal Halfon, founding director of the Center for Healthier Children, Families and Communities at the University of California, Los Angeles, moderated the discussion. This chapter discusses national-level policy solutions and plans for action, examples of state-level practices, and finally emphasizes the need for in-depth system changes in order to reach the desired goals and outcomes.

NATIONAL-LEVEL POLICIES

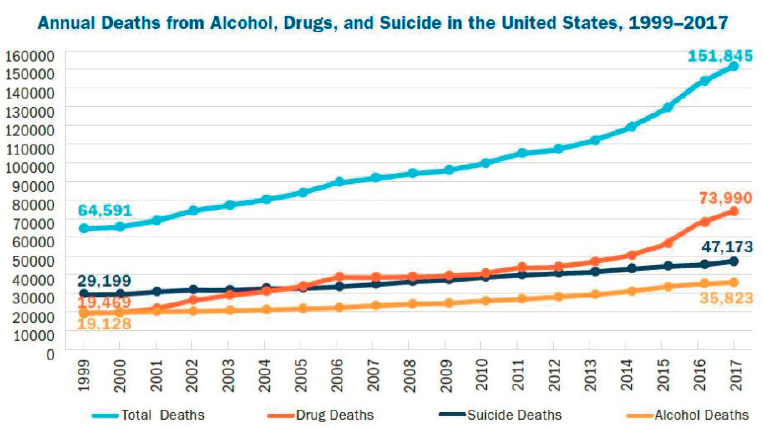

Miller opened his remarks by noting, “Our country has a mental health problem right now, but the solutions are as fragmented as the problems that created it.” He presented data showing raw number increases in all-age deaths from drugs, suicide, and alcohol over the last several years, with 2017 deaths reaching nearly 152,000 (see Figure 5-1).

SOURCE: Trust for America’s Health and Well Being Trust, 2020.

Miller noted a combination of individual-level factors (loneliness and isolation), systemic elements (fragmented care delivery and a lack of access to health services), and social and community conditions (housing and food insecurity, racism, intergenerational trauma, and economic exclusion) have together resulted in “deaths of despair.” For the past 3 years, Miller explained, Americans have died at increasingly lower ages, primarily due to deaths from drugs, alcohol, and suicide. There have been some glimmers of success with recent declines in life expectancy, he said, but the battle against the opioid crisis shows how fragmented and narrow the approach to urgent needs still remains (Auberach and Miller, 2020). This crisis will not be solved by business as usual, he said, calling for a comprehensive, systemic response to address these complex issues. There is a need for short- and medium-term actions immediately, as well as longer-term investment in intergenerational work. The country’s approach should be broadened, reducing risk factors such as trauma and the impact of poverty and racism.

Guidance for Congress

To more clearly lay out comprehensive solutions for Congress, Miller shared a guide that was created by Well Being Trust, called Healing the Nation to advance mental health and addiction policy (Well Being Trust, 2019). There is a clear need to shift the focus further upstream to focus on root causes and meet people where they are, so they created downloadable

policy briefs keyed to different sectors like health care, education, the judicial system, the workplace, and unemployment.1 They provide actionable solutions, highlighting that there are multiple entry points where mental health can be addressed, enabling a multifaceted approach. As part of their solutions, Well Being Trust also developed a framework for excellence in mental health and well-being, which focuses on health promotion through the creation of vital community conditions, as well as prevention, treatment, and maintenance for those at greater risk.

Miller reiterated the importance of using the life course health development (LCHD) perspective in pursuing efforts to promote mental health and well-being, which defines health as a developmental process and is built on a rapidly expanding evidence base. It not only goes beyond connecting early exposures to later disease states, he said, but elucidates the ways in which physical, social, and emotional environments are embedded into developing biobehavioral regulatory systems (Halfon, 2014). Emerging models have proved able to provide a synthesis of several different fields and an understanding of the mechanisms and dynamics of interactions. If we do not address issues early in life, he added, they will have an even bigger impact downstream in later decades, resulting in outcomes such as school failure, obesity, depression, hypertension, diabetes, and eventually memory loss and premature aging. We need a systems lens across the life course to fully address these complex issues, he concluded.

Leveraging the Congressional Budget Office

Counts began his presentation with a question: What is holding us back from investing in children’s mental health? It is not a politically contentious issue, he said, and the economics of prevention, which highlights the fiscal savings resulting from mental health services, should be in our favor, but we still don’t see meaningful levels of investment. One of the biggest issues, he continued, is that budget neutrality dominates the political process, as both parties try to avoid increasing fiscal deficits.

To determine whether or not a policy that increased spending through such preventive investment has actually saved money in the long run, Counts explained, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analyzes the economic effects of federal policy options they might potentially fund on the federal budget over 10 years. Their findings determine whether or not a potential policy or program may increase or decrease the federal deficit, which can affect the likelihood of getting supporting legislation passed. Counts provided some background on the issue of “dynamic scoring,”

___________________

1 These briefs are available for download from the Well Being Trust website: https://healingthenation.wellbeingtrust.org/.

the process of calculating the secondary effects of a spending decision.2 In federal budgeting, direct effects amount to program expenditures, whereas secondary effects constitute the savings that accrue from that spending. Determining the downstream economic benefits of interventions for health and well-being programs, then, would require CBO to consider the secondary effects. Counts explained that CBO typically defines “prevention” in terms of things like increased screenings and costly diagnostic devices rather than the typical LCHD interventions that are often more oriented toward development and behavior. CBO put out several guidance documents to help understand their process for examining preventive health programs in which they ask a series of questions, comb the literature for answers, and create an economic model to see what they can find.3 While this might work in some areas, Counts said that LCHD literature does not really utilize the kinds of clear studies that show that if you do X in childhood, Y will occur decades later. This makes it difficult for CBO to provide clear analysis that can fully validate LCHD approaches as certain and trustworthy. Further, there is evidence that many of the greatest budget effects may arise from the macroeconomic effects of large-scale LCHD investments, but there is even less literature tying LCHD interventions to potential changes in the larger economy.

CBO is willing to use different modeling and simulation approaches, but they do not currently have the resources to build necessary models for LCHD. If they were able to create a model similar to the one used by Washington State Institute for Public Policy (WSIPP) that could begin to answer some of these questions, it would be much easier to score budget impacts for LCHD-related policies. Unfortunately, Counts said, CBO has not been able to create something like that because it lacks additional resources, which has been one of the biggest barriers to scoring health prevention policy at the national level. If at some point it was possible for them to demonstrate the savings accruing from prevention policy, then the government would be more willing to pay for investments in LCHD interventions and services proposed in legislation. As an example, he presented a WSIPP estimate from a Triple P Positive Parenting Program, a multi-tiered family-support and intervention program that, evidence demonstrated, was effective at reducing childhood maltreatment. The economic models created to evaluate Triple P’s cost effectiveness found it to be very effective: it showed a 9:1 benefit-to-cost ratio (Washington State Institute for Public Policy, 2019). This model was also able to determine where the benefits would

___________________

2 For more information, see https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-aredynamic-scoring-and-dynamic-analysis.

3 See https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2020-06/56345-CBO-disease-prevention.pdf.

be realized, and because of the program’s multifaceted nature, the benefits were spread out across multiple sectors.

While CBO does not have the right models currently in place, Counts said, there is still a lot that can be done to bring about positive change. For starters, he explained, we must ensure that the people advising the many academics on CBO’s advisory panels understand prevention science. We also need people who understand how to compile the LCHD literature in a way that makes modeling easier for them. The CBO staff is required to be accessible and available to meet and consult with experts, he added. When a particular issue is not a congressional priority and the modeling and compilation takes too much time, it just often does not get finished. If they were able to create a WSIPP-type model, it would be much easier to pass policies, he added.

Alternative Payment Models to Capture Return on Investment

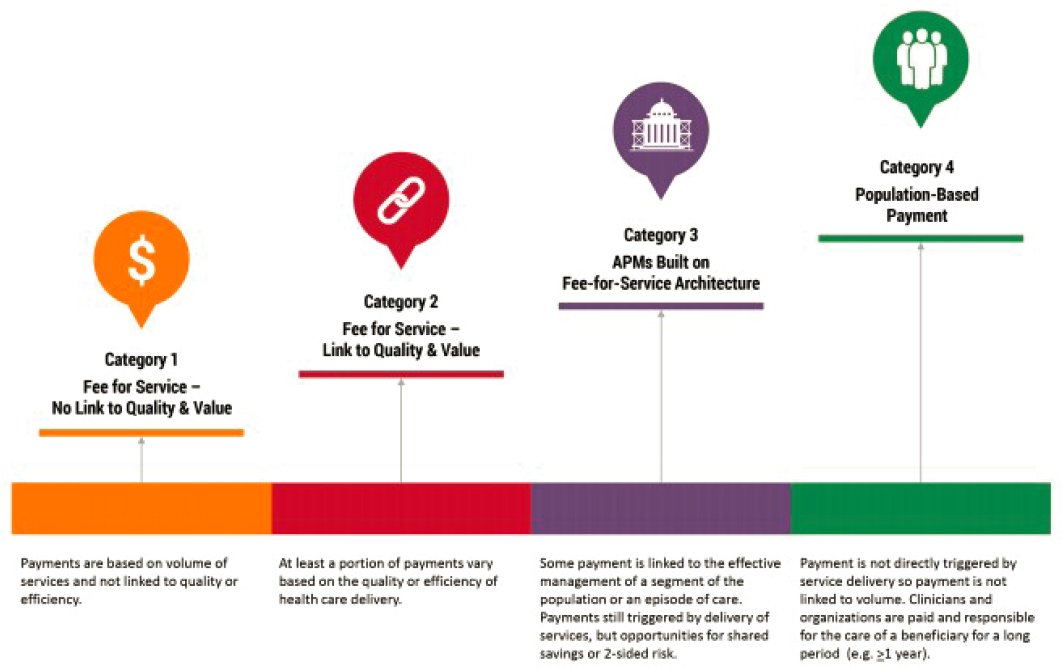

While urging mental health professionals to work with CBO to establish new funding through congressional legislation, Counts also encouraged the participants to simultaneously take advantage of money already being spent. We are on a path to spend close to $4 trillion each year in health care, he said, but it is distributed poorly, and the majority of spending goes toward specialized treatments and end-of-life care with almost nothing going toward prevention. As the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and other health care institutions around the country continue to shift to more value-based payment models, Counts said the entire field is realizing there are other ways to finance health care. He explained the CMS framework, the goal of which is to move up categories, incentivizing organizations to increase provider accountability and focus on population health management (see Figure 5-2). He said he and Halfon are exploring ways to extend this category framework to better capture life course health.

Miller offered suggestions for payment recommendations, noting that the main issue is not the way we pay for mental health, but the need to change the way we pay for overall health care and medical practice, which includes mental health. One way to doing this is to move as quickly as possible away from fee-for-service reimbursement toward ensuring payment for the delivery of services to keep the patient healthy instead of charging per patient visit, similarly to how the CMS framework works. Additionally, he urged the creation of established incentives to encourage clinicians to work closely with mental health providers. In doing so, this can increase the accountability of the general physician for certain behavioral health conditions.

SOURCE: Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network, 2017.

In addition to these alternative payment models, Counts also introduced the concept of pay-for-success models and social-impact bonds. While these are typically found more in the realm of social services and not health care, there are plenty of situations in which their use could be applicable. Investors will have to fund projects or interventions up front in places where intermediaries and direct-service providers deliver services to target populations. The outcomes for this project would be measured and validated by an independent evaluator and the results forwarded to a back-end payer. If the project successfully saves money, a portion of that shared savings would go back to the original investors, while another portion would stay with those implementing the project. Both of these examples do have their problems, Counts cautioned. Pay-for-success projects are often a one-off deal, are difficult to scale up, and can backfire if they do not work, threatening investors with financial losses. Such high-stake ventures force people to think myopically and miss important nuances within a mental health context.

Combining concepts from both pay-for-success ventures and alternative payment models can offer a path forward by engaging more sectors over longer time periods, but in a more iterative way that supports long-term incentive realignment. Alternative payment models are often structured to run in fiscal-year increments, which is too short a time to show improved outcomes or savings. Counts did highlight the benefits, though, saying that whether they are administered through Medicaid, state, or local health plans, most of these types of contracts are just that: contracts. They consequently do not require full policy change or legislative action, giving people on the ground an opportunity to bring investors together to take action if they see a strong prospect. Both types of contracts—pay-for-success and alternative payment models—have benefits that communities can build from, and together they represent what’s missing in LCHD financing. A blend of contracts that borrow from pay-for-success and alternative payment models can align finances on the ground for LCHD (Counts, 2018). Overall, Counts said, the money exists somewhere, and life course health promotion has a positive return on investment, but we as a sector need to get creative about capturing this value at the national and local levels to better tell the story.

STATE-LEVEL POLICY

To solve the challenge of integrating mental health more sustainably into a nontraditional medical setting, Miller suggested looking more closely at the financial roots of the problem and offered some examples of how programs are working across the country.

Colorado SHAPE

One Colorado program launched a novel payment model called Sustaining Healthcare Across Integrated Primary Care Efforts (SHAPE), a partnership between Collaborative Family Healthcare Association, Rocky Mountain Health Plans, Colorado Health Foundation, and the University of Colorado School of Medicine’s Department of Family Medicine. Miller described the program as “liberated from fee-for-service,” and it demonstrates what can happen when primary care has a budget to manage everything they need. They see comprehensive care as contributing to cost savings, and an analysis comparing practices that received SHAPE payments with those that didn’t found those receiving SHAPE payments generated $1.08 million in net cost savings for their public payer population over an 18-month period, primarily through reducing downstream hospitalizations (Ross et al., 2019). They had improved screenings and diagnoses in addition to cost savings. “You have to always think of the person in the context of the family, and the family in the context of the community,” Miller added.

California’s Vision for Change

Briscoe discussed another state-level example being tested in California that highlighted the true mental health crisis happening across the country. Between 2006 and 2014, mental health hospital days for children have increased by 50 percent. Inpatient visits related to suicide, suicidal ideation, and self-injury by children 17 years old and younger have increased 104 percent, and the increase for children ages 10 to 14 has been even greater. Everyone pays a high price for this, he added, making the search for solutions to this crisis fiscally and morally imperative. Reiterating Miller’s introductory points, Briscoe stated that mental health and substance-abuse disorders are the leading causes of disease burden in the United States. As an example, he pointed to the fact that 37 percent of high school students with mental illness drop out of school, the highest dropout rate of any disability group.

To inject some optimism into the conversation, Briscoe suggested that California has arrived at a once-in-a-generation opportunity in which public opinion, community support, policy agendas, political will, and an economic rationale have all converged to enable support for funding and investing in children’s mental health. Even though it has the fifth-largest economy in the world, California has realized that the problem has become so dire that the state cannot bring transformational change simply by providing more therapists or stigma reduction. The leader in this statewide reform, California Children’s Trust, has cast a bold vision that urges that

“every child in the state has a fair and intergenerational opportunity to attain their full health and development potential free from discrimination,” but there are four challenges that stand in the way:

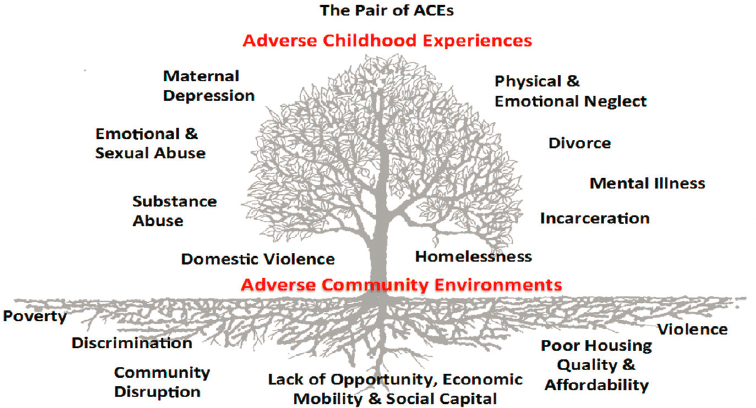

- Addressing the root causes of social inequality and racism. One in two children in California live in or near poverty. The systems we live in corrode human relationships (see Figure 5-3).

- Bridging the access gap. Eligibility has increased, but access has declined.

- Fixing a broken model. No common framework for defining and understanding behavioral health exists, and there are fewer providers than needed.

- Integrating a fragmented children’s health service system. Children receive services from multiple different systems with little connectivity or continuity.

Briscoe added that California Children’s Trust is working to find solutions to the problem of fragmented systems and presented the framework as a means to achieving this vision (see Figure 5-4). They have three strategic priorities, centered on equity and justice. First, they plan to maximize funding through state and local administrative reform, fully claim the federal match, and follow Medicaid dollars to find money that’s been “left on the

SOURCE: Center for Community Resilience, 2020. Reprinted with permission.

SOURCE: Alex Briscoe presentation, February 13, 2020.

NOTE: For more on the Framework for Solutions, see https://cachildrenstrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/framework4.pdf.

table” due to the complex system of waivers and intermediary programs. They will also expand access and participation by redefining “medical necessity” and allow provision of services without a confirmed diagnosis. This priority will also include the integration of community-based organizations in care delivery and the expansion of peer-to-peer and social models. Finally, they want to reinvent systems to increase transparency and accountability. Briscoe said that they will address this by integrating data systems, mandating common assessment tools, defining a common set of outcomes, and creating collaborative financing models.

GOING BEYOND TECHNICAL SOLUTIONS

Halfon asked the three speakers to elaborate on where to go from here, how to prioritize action with so many challenges to tackle, and whether policy makers should seek broad and transformative priorities or focus on addressing specific things. Miller emphasized points made throughout

the webinar, saying that there is a need to be more creative in developing solutions and think differently about providing resources. Merely referring patients to other facilities or adding more clinicians to a roster will not solve the challenges. Instead, Miller suggested bringing providers into churches and other places of worship or thinking more meaningfully about task shifting. Echoing Hoagwood’s third horizon approach, he stated, “We have to be disruptive in changing the culture to think about where the care is needed instead of just where we provide care right now.” He also highlighted the need for a more intentional focus on recruiting and training clinicians who look like the people asking for help. Counts and Briscoe both highlighted the concept of sharing power in communities as an important next step. Counts said that they are learning and making strides in certain areas, but replicating that will be difficult. He also added that in order to build solidarity in communities and test out new innovations, participation by programs such as the Accountable Health Communities4 movement, the Healthcare Anchor Network,5 and others that feature collective impact and distributive leadership will be an important first step. Briscoe offered transformative suggestions, saying there needs to be a broad social movement to reinvent the social contract, a movement that answers such questions as what we owe each other and how we need to treat each other. The next level down from there would be reexamining the power dynamic between the system and the patient so that people receiving the services can be structurally empowered to make decisions and take ownership of their health. Thinking more incrementally, Briscoe suggested that states could remove and reform the definition of “medical necessity,” allowing mental health to be reinvented as a support for healthy development, and they could formally include peers in social models in reimbursement structures and practices. Building on all three suggestions, Halfon mentioned the All Children Thrive project in Cincinnati and described their attempts to redefine “collective impact.” The state of Ohio and Cincinnati together are using this approach to rethink the mental health system. He also added that, in collaboration with the UCLA Center for Healthier Children, Families, and Communities and Public Health Advocates, the California Department of Public Health is in the process of launching All Children Thrive California (ACT California). Building upon the All Children Thrive Cincinnati prototype, ACT California is engaging cities across the state to prioritize the well-being of all children. Moving upstream and working in new and different ways must involve more than the manner in which we work with

___________________

4 For more on the Accountable Health Communities with CMS, see https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/ahcm.

5 For more on the Healthcare Anchor Network, see https://healthcareanchor.network.

the service system, Halfon said. It also involves changing the ecosystems in which children live and designing comprehensive change packages.

Leveraging Financing

As financing remains a fundamental piece for implementing any changes, Halfon also asked about the potential major policy change that would occur in spinning Medicaid off as a block grant program and what such a fundamental shift in Medicaid financing might mean for children’s mental health. The Trump administration issued guidance in early 2020 under which states could apply for waivers that would convert many Medicaid programs for adults into a type of block grant, with capped federal funding and new authorities that could also cut coverage (Aron-Dine et al., 2020). Briscoe strongly voiced his opposition to using any kind of block grant device within the current levels of funding across the country. Miller added that several legal challenges to the administration’s proposal are already working their way through the courts. If, he said, we fail to address underlying socioeconomic factors that cause poverty in communities while at the same time limiting the availability of resources to serve those at highest risk, then shame on us. Medicaid has strengthened itself and become a robust program over the years, said Miller. If we now limit the growth of a program that could have an effect on communities that need it without addressing underlying economic factors, we would only be setting ourselves up for major downstream negative outcomes.

Identifying and Using Factors for Growth

Children often grow up unprotected in risky environments and can spiral downward into despair and alienation, Halfon stated. On the other hand, he pointed to other protective factors at the social and individual level that can help children learn to modulate their emotions in such environments: support programs for families experiencing significant social, economic, and emotional challenges, as well as programs that enhance children’s adaptive and coping skills like mindfulness, meditation, and other techniques. He asked the speakers to consider how mental health services could better address multiple types of interacting risk factors and develop better protective factors for coping with different forms of adversity that promote better health and well-being outcomes for children. Miller responded that the mental health and addiction communities have not embraced the need to address these important factors and have been slow to integrate them within an overall comprehensive and integrated strategy. “This is really at

the heart of what we have done wrong as a field,” he said. “We’ve talked about factors but haven’t done it in a comprehensive way that allows us to create a plan lifting up protective factors in a community or creating a policy with the top five risk factors in mind.” Briscoe strongly agreed, noting that reimbursement systems actually structurally deny the ability to pay for those factors that encourage social and emotional development. He mentioned the Kauai longitudinal study of risk and resilience that elevated the importance and role of resilience, identifying three protective factors that were key in enhancing that adaptive capacity: having a caring adult, maintaining hope for the future, and developing the ability to adaptively distance (separating out from your own sense of self what happened to you) (Werner, 1989). None of these are currently reimbursable, though, he said. To help measure success, our system needs to start paying for services, the enhancement of these protective factors, and techniques such as mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy, Counts said, because we know these will help build individual resilience and promote children’s health and welfare. Counts added that he envisions something along the lines of Communities That Care, an evidence-based, prevention-science process that brings together entire communities to help youth thrive (Oesterle et al., 2018). Many evidence-based interventions in this field were first tested in the 1980s and 1990s, so they are a bit dated, he noted. In a time of rapid technological change in which the risk factors and context have shifted, it is difficult to judge the continued validity of these interventions and somewhat dated evidence-based frameworks. Success, Counts added, requires us to lean on the wisdom of communities, and consider the changes in epidemiology as part of a “continuous quality improvement” process, which guarantees regular updates and built-in growth. Recognizing the importance of socioeconomic determinants, one of the keys to success will be a whole-community approach that involves business, the workforce, and education to ensure that all interventions and policies are working toward people’s financial health as well as socio-emotional health.

Miller described two essential takeaways. If we do not approach mental health comprehensively throughout the full life course, he said, we are failing people in their communities. We have to take into account the complexities of health and use multifaceted policy approaches to solving these complex problems, such as including friends and partners who have not always been included in health reforms before. In closing, Halfon explained that the forum had undertaken this webinar series because progress in life course health science, through landmark studies like the Kauai study have clearly demonstrated the role that risk and protective factors play in the onset and unfolding of mental health problems across a person’s life

course. Informed by ambitious and influential intervention programs like Communities That Care, new broad-based community-level initiatives like All Children Thrive Cincinnati are pushing forward with change. Halfon suggested that the real challenge is combining and bundling successful interventions into an ecosystem of services and support that can be successfully scaled up at a population level. There is much more we can and should be doing, he said.