2

Overview and Trends in Children’s Mental Health

The first webinar in this series, led by Neal Halfon, director at the UCLA Center for Healthier Children, Families, and Communities, began by reviewing current and emerging trends in mental health disorders among children and youth. Halfon and Kimberly Hoagwood, Cathy and Stephen Graham Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at New York University’s School of Medicine, presented data on the state of children’s mental health and the need for viewing health development across the entire life course. The second webinar, featuring Stephen Buka, professor of epidemiology at Brown University School of Public Health, complemented the initial discussion with perspectives on changing epidemiology in the field. This chapter summarizes sections of both discussions, focusing on the drivers of change behind the shift in the epidemiology, the reasons behind the increasing numbers of mental health disorders among children and youth, and the important developmental implications these disorders represent for our society. It also includes a presentation during the February webinar by Alex Briscoe, principal at California Children’s Trust, in which participants discussed how children’s mental health is financed and administered, and the consequences of the fragmented and underresourced strategies for promoting the social and emotional health of children.

SHIFTING EPIDEMIOLOGY AND DRIVERS OF CHANGE

Introducing participants to the motivation behind the webinar series and the desire for a better system, Halfon shared that mental health disorders are the leading cause of disability in individuals between the ages

of 15 and 44 (Friedrich, 2017). He also described mental health disorders as an important contributor to the recent decline of life expectancy in the United States, as what he described as the “deaths of despair” continue to increase. Three-quarters of mental health disorders begin to exhibit themselves by age 24, making the first few decades of life an important strategic target for mental illness prevention and mental health promotion. Additionally, Halfon demonstrated that the significant increases in mental health disorders for children and adolescents reflected in several national studies and data sets result in increasing rates of suicide, self-harm, anxiety disorders, and depression among young people. This relatively rapid shift in the epidemiology of mental health disorders, he said, suggests an underlying shift in the ecosystem of risks that results from four deep drivers of human ecosystem change:

- Changeover in historical eras. Having previously transitioned from being an agrarian society to being an industrial society, we are now transitioning toward becoming a technological-digital society.

- Major ecosystem disruptions. This transition is tremendously disrupting ecosystems that influence human development and is significantly altering cultural scaffolding, relationships with the environment and planet, and global economic production models.

- Agents accelerating change. Globalization, digital technology, and climate change all interact and require rapid, highly responsive adaptation.

- Increasing pace of change. Change seems to be happening faster than we can adapt to it.

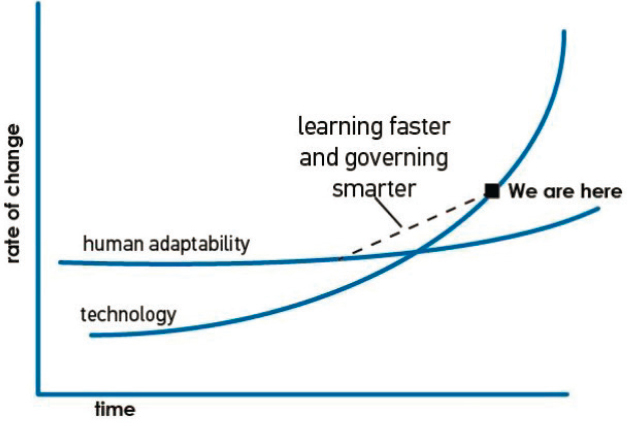

All of these drivers converge to present society with a serious adaptive challenge (see Figure 2-1).

INCREASING MENTAL HEALTH DISORDERS IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

Hoagwood elaborated on these statistics as well, saying that one in six children between 6 and 17 years old suffers from a treatable mental health disorder. Of these children, 32 percent have anxiety, 19 percent have behavior disorders, and 14 percent have diagnosed depression. Among young people between the ages of 15 and 24, suicide is the second most common cause of death. She pointed out that these numbers have gotten worse, and that even with all of the research and knowledge accumulated over the last few decades, trends in youth suicide rates have risen.

SOURCE: Graph—Ability of Humans to Adapt to Change from “That Other Line” from “What the Hell Happened in 2007?” from THANK YOU FOR BEING by Thomas L. Friedman. Copyright © 2016 by Thomas L. Friedman. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Using Available Data to Track Prevalence

During his presentation at the October webinar, Buka reinforced the notion that mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders are becoming more common and are fundamentally different from children’s diseases in the 1970s and 1980s such as infectious disease and nutritional problems. These “new morbidities” are rooted in social difficulties, behavioral problems, and developmental issues, he said. Though the number of children with mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders has increased, the lack of long-term longitudinal cohort data on the subject makes it difficult to understand causes and develop strategic and responsive policies and interventions. Unfortunately, there is no dedicated surveillance system for mental health in children in the United States, he said, so it is difficult to provide an overall estimate of prevalence for all childhood mental disorders. He suggested there is some evidence that this prevalence is increasing.

Buka shared a systematic review from 2014 that compared data from the 21th century with similar data from the 20th century. Exploring changes in internalizing and externalizing factors, it showed that one in five children now experience mental health problems. Researchers concluded that the burden of internalizing symptoms is increasing in adolescent girls, an increase not restricted to Western countries (Bor et al., 2014). Another study, in which he participated, examined the odds of serious depressive symptoms associated with different types of negative experiences on Facebook.

They found that any type of adverse experience on Facebook actually doubled the risk of depression (Rosenthal et al., 2016).

In an effort to better understand this potential rise in children’s mental disorders, Buka described a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Supplement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2013 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). The authors summarized mental health surveillance among children from 2005–2011 and identified an increasing prevalence of attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorders, and bipolar disorder, as well as changes in drug use patterns in children compared to 1994. One CDC survey indicated a 21.8 percent increase in ADHD diagnoses from 2003–2007, while another data set revealed a nearly four-fold increase in autism rates from 1997–1999 to 2006–2008. While some of these increases could be attributed to case definitions or changes in methodology, he noted, deaths are a clear outcome that can be counted without variability. After a relatively stable period from 2000–2007, Buka shared that suicide rates for ages 10–24 increased from 2007–2017, even as homicide rates were decreasing (Curtin and Heron, 2019). Most alarming, the data showed that in the younger part of the cohort, those between 10 and 14 years of age, suicide rates decreased from 2000–2007 but then nearly tripled from 2007–2017.

Disparities Between Populations

When the data were segmented by different population groups, other varying trends emerged. Buka presented the findings of a 5-year study on racial disparities in pediatric mental health emergency department (ED) visits, which looked at more than 293,000 patients from 2012–2016 (Abrams, Goyal, and Badolato, 2019). While the rates increased significantly overall for all groups, the rate of increase for non-Hispanic black children was nearly double that of non-Hispanic white children. Demographic patterns from the CDC MMWR show higher estimates of ADHD among boys, children living in households where the highest level of education was high school, and those living below the federal poverty level. Similarly, for students aged 14–18, feeling sad or hopeless every day for 2 weeks was more likely among girls than boys. Hispanic students similarly experienced higher rates compared to white or black non-Hispanic students.

In summarizing 21st-century mental health research trends, Buka pointed out that even without a singular surveillance system, the aggregate testimony of published literature, insurance claims, and ED visits paint a picture of increasing rates of mental disorders in children. This includes increased numbers of adverse childhood experiences, increased anxiety among females, dramatic increases in completed suicides since

2007, increases in reported ADHD and autism, and increases in ED visits for mental disorders. He again also emphasized the evidence showing that negative Facebook experiences such as bullying, meanness, unwanted contact, and misunderstandings are associated with increased rates of depressive symptomatology.

DEVELOPMENTAL IMPLICATIONS

It is clear from a variety of sources that rates of mental illness in children and adolescents are increasing, Buka noted, but what are the developmental implications of that? How concerned should we be as a society? The immediate burden is important, but there is also a need to examine the consequences that will continue later in life and to understand the etiology of these diseases, especially if we want to develop, implement, and fund increasingly effective prevention and mental health promotion interventions.

Mental Health Costs

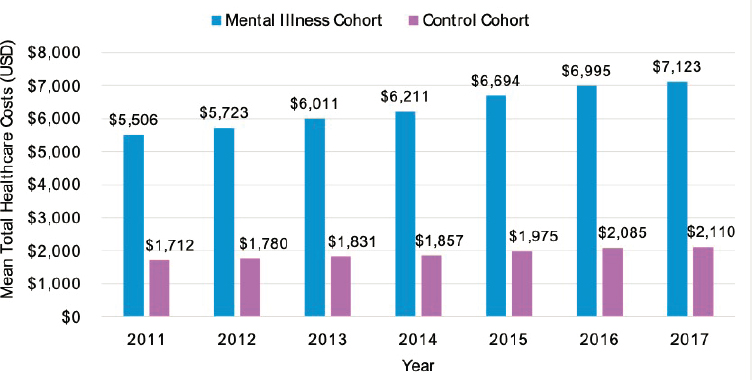

While health care costs in the United States have grown massively in recent years due to several factors, Buka cautioned that there should be a great amount of economic concern related to these increases in mental illness. Half of all mental illnesses begin by the age of 14, and 75 percent of them are diagnosed by the time a person reaches their middle 20s (Kessler et al., 2007). Other evidence demonstrates the increasing rate of childhood mental illness and its associated health care costs in the United States. Tkacz and Brady found the incidence of mental illness increased 19 percent and prevalence increased 30 percent from 2011–2017 (Tkacz and Brady, 2019). Over this same period, the prevalence of depression, anxiety, attention disorders, and developmental disorders all increased. They found a clear economic link as well, with the presence of a mental health diagnosis being associated with at least double the annual health care costs compared to similar families with unaffected children for the years assessed (see Figure 2-2).

During his presentation, Briscoe also warned participants about the costs of mental health, saying that everyone—individuals, hospitals, and society—pays a high price. This makes finding solutions a fiscal and moral imperative. Briscoe also detailed the uncapped and unfulfilled federal entitlement that children in Medicaid enjoy under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit and the financing opportunity that can be leveraged with its creative application. Between 2006 and 2011, $11.6 billion was spent on hospital visits for mental health. Mental health and substance abuse disorders are now the leading causes of disease burden in the United States, and while everyone pays, he said, the burden is not equally shared

SOURCE: Tkacz and Brady, 2019.

across populations. The “price” is higher for certain racial groups in terms of economic and life costs. Seventy-five percent of children on Medicaid in California are black or Hispanic, meaning they often get the wrong services at the wrong time in highly restrictive settings, and there are important race and class divides between providers and beneficiaries. The suicide rate for black children ages 5–12 is double that of their white peers in the same age range. These realities demand action that goes far beyond a mere tweaking of the system, he said. More details on the rest of Briscoe’s presentation and his proposed solutions are described in Chapter 5.

Genetic and Environmental Roles in Mental Health

While some mental illness has always been understood to have a genetic component, the rise in rates and newer technological abilities to conduct genetic research has led to studies that better highlight the critical interface between environmental factors and manner in which these exacerbate the genetic risk for certain diseases. Buka described a 2014 study exploring biological insights from schizophrenia-associated loci that examined nearly 37,000 cases (Ripke et al., 2014). In addition to genes involved with brain development, the study found possible connections between genetic risks and brain tissue involved in immunity, demonstrating the speculated link between the immune system and schizophrenia. A related 2018 study demonstrated how the intrauterine environment modulates the association of schizophrenia with genomic risk (Ursini et al., 2018). They concluded that a subset of some of the most significant genetic variants associated with schizophrenia “converged on a developmental trajectory sensitive to events that affect the placental response to stress.” Risk for schizophrenia

was much higher—sometimes as much as 800 percent higher—if there were in-utero complications during the mother’s pregnancy such as diabetes, obesity, pre-eclampsia, or smoking. Conversely, conditions that would produce a “high-risk” genetics score would raise the risk by 50 percent if the pregnancy was healthy. Researchers posit that the placental stress results in an inflammatory response that can then “turn on” genes related to immune response, increasing the risk, but polygenic risk scores account for less than 2 percent of the risk for schizophrenia, Buka said. He agreed with the study authors that a new risk score is needed for schizophrenia that also incorporates placental health (Begley, 2018). He called for a greater emphasis on surveillance, understanding the course and costs of disease, and overall prevention.

Leveraging Research to Optimize Development

Buka shared the strategic plan for the National Institutes of Mental Health and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the mission of both is to address serious mental illnesses and emotional disturbances, improve data collection, optimize outcomes, and test interventions for effectiveness in community settings. Commenting on the potential environmental influences, Buka said that even with schizophrenia, a mental illness with a strong genetic component, we now know that the genetic risk can remain low with a healthy pregnancy. It took decades to figure this out, he said, but we cannot wait another 30 years to make the same discovery for depression and anxiety.

Halfon mentioned new longitudinal cohort studies in other countries with built-in interventions where children are followed developmentally and the state tries to optimize that development through tested interventions. Recognizing that early interventions are critical to improving life chances for children and reducing inequalities, the lack of research and long timelines needed for randomized control trials led to the innovative experimental cohort of Born in Bradford’s Better Start in England (Dickerson et al., 2016). The research team began recruiting participants between January 2016 and December 2020 and planned to implement 22 interventions to improve outcomes for children ages 0–3 in ethnically diverse inner-city areas of Bradford. Similarly, Halfon mentioned, GenV, a research initiative in Melbourne, Australia, is striving to answer persistent questions regarding preterm birth, mental illness, obesity, and other issues facing children today (GenV, 2019). Launched in 2013, the GenV researchers have sought to discover links and find answers in a smarter and faster way than traditional research that only focuses on one singular aspect of child development at a time. While these are both exciting developments, Halfon said that we are still a long way from understanding if activities such as teaching young children meditation and yoga constitute adequate tools for protecting children’s mental health.

This page intentionally left blank.