3

Considerations for Decarceration

A selective draw-down of correctional populations raises the obvious question of which individuals should be either released or diverted from prisons and jails and what criteria should be used to make those decisions. The COVID-19 pandemic illustrates that the harms of incarceration also include diminished public health. At the same time, there are cases of incarceration where the immediate impact on public safety may be small to negligible—such as those incarcerated due to failure to pay small amounts of bail, due to a technical or parole revocation, or imprisonment of the elderly or medically compromised—even as continued incarceration exposes the incarcerated person to a heightened risk of COVID-19–related sickness and death.

In order to reconcile public safety and public health considerations, in this chapter the committee argues that, in light of the current public health crisis, a more inclusive assessment of the impacts of incarceration on society is needed. To this end, the chapter first reviews research on recidivism and the effects of incapacitation through incarceration on crime. It then outlines legal mechanisms for decarceration, through diversion and release. Finally, the chapter reviews efforts made by prisons and jails to depopulate since the start of the pandemic, cataloguing an inability to meet the crisis brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

BALANCING PUBLIC SAFETY AND PUBLIC HEALTH

There are several candidate criteria for identifying which individuals should be released or diverted. One might prioritize releasing and divert-

ing incarcerated individuals for whom the risk of death and serious illness associated with contracting COVID-19 is relatively high. While a small proportion of incarcerated individuals are in the high-risk age range,1 incarcerated individuals in the nation’s prisons and jails are less healthy on average than the general population, with a high age-adjusted prevalence of conditions that elevate the COVID-19 mortality risk, such as asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (Skarupski et al., 2018; see also Chapter 2). Moreover, there is evidence of premature aging of people living in prisons and jails and of the early onset of age-related cognitive impairment and other age-related health problems (Ahalt et al., 2018; Greene et al., 2018). Hence, despite the younger average age of the incarcerated population, the high prevalence of comorbid conditions that are likely to enhance the risk of serious COVID-19–related complications implies that age-based infection mortality rates for people living in prisons and jails may differ from those of the general public. To the extent that correctional administrators prioritize reducing mortality and health equity within institutions, such preexisting conditions that increase vulnerability may provide key considerations.

Beyond health conditions, correctional authorities will certainly be concerned with the impact on public safety of reducing their institutional populations. Research on recidivism reveals that a large proportion of individuals released from prison2 are subsequently rearrested, with many being returned to prison custody. A substantial portion of these arrests and returns to custody are for technical violations and relatively less serious offenses (Alper, Durose, and Markman, 2018; Carson, 2020). In some instances, however, individuals released from prison subsequently commit serious offenses. This is also true in some instances when individuals are released from jail either due to time served or a pretrial release.

Overall, there is great heterogeneity among incarcerated people and their likelihood of future serious offending, and there have been recent reductions in correctional populations in the United States that have not caused a measurable increase in serious violent crime (see below and Appendix A). Moreover, steps can be taken to reduce recidivism risks through reentry planning and the provision of supports, especially during the first few weeks following release, when both the recidivism risk and the mortality risk are particularly high. Appendix A provides a detailed discussion of

___________________

1Carson and Sabol (2016) document that while the U.S. prison population has aged since 1993, the proportion over 65 years of age is relatively small. Specifically, the authors estimate that 2.2 percent of people prison in 2013 were over age 65. For comparison, roughly 16 percent of the U.S. population is 65 or older.

2 Much of the research exploring recidivism focuses on individuals sentenced to prison. Most individual admitted to jail are not ultimately sentenced to prison, with a large percentage of them released within a few days of booking and prior to the adjudication of their cases.

what is known about the recidivism rates of incarcerated individuals from national studies: the evidence indicates that correctional authorities can use information at hand to identify individuals at high risk of recidivism and potential factors that might mitigate that risk through supportive reentry planning. This section briefly discusses the predictability of recidivism rates and key implications of that literature for the current pandemic.

Predictability of Recidivism

The likelihood of recidivism varies greatly among people who are incarcerated. Moreover, recidivism risk changes over the life course. For example, one of the strongest empirical regularities in criminology is the large reduction in the likelihood of criminal justice involvement with age, even among individuals with lengthy criminal histories (Gottfredson and Hirschi, 1990; Laub and Sampson, 2003). Moreover, recidivism risk varies considerably with time since release, being particularly high in the first few weeks following release (as is also the case for health outcomes, including drug overdoses and death) and declining thereafter.

A report by the National Research Council (NRC, 2008) summarizes the factors correlated with the likelihood of subsequent criminal justice involvement after release from incarceration. Many of these factors are static, in that they are part of someone’s past and cannot be altered, while other factors are dynamic in that they can change and can decrease the risk of recidivism by careful reentry planning and service provision. Among the static factors, individuals released from their first term of incarceration have lower recidivism rates, as do individuals with less lengthy criminal histories and individuals who are older. The content of one’s criminal history—the current conviction offense as well as what one has been convicted of in the past—also has some predictive power. With respect to dynamic factors, they include substance use disorders, extreme material deprivation, homelessness, and antisocial thoughts and beliefs. Since these factors are changeable, such services as income support, housing assistance, substance use treatment, and cognitive-behavioral therapy can lower the recidivism risk for many and are particularly important during the transition period within the first few months of release (NRC, 2008). For released people with severe mental illness, planning for continuity in mental health care is also likely to be important for avoiding adverse outcomes upon release (see, e.g., Theurer and Lovell, 2008).

Another line of research relevant for jail depopulation in the context of the pandemic finds, in different ways, that pretrial detention is often poorly calibrated to the risk to public safety. Research on risk assessment finds that it is possible to release some groups of the jail population with no effect on later arrests or failure to appear in court. For example, analyzing New York court

data, Kleinberg and colleagues (2018) report that 41 percent of the pretrial detention population could be released with no increase in crime. Indeed, risk instruments have been used in an effort to reduce pretrial populations (Viljoen et al., 2019). Research on racial disparity point to relatively high rates of incarceration among Black (and low-income) defendants, which may in part be due to an inability to pay bail (Demuth, 2003; Schlesinger, 2005; Wooldredge et al., 2015), and racial bias in detention decisions (Arnold, Dobbie, and Yang, 2018; Spohn, 2009). The findings suggest that Black defendants are often over-incarcerated relative to their risk to public safety, and they could be released with no greater risk than similar White defendants. Research exploiting the random assignment of judges, along with other natural experiments, finds that pretrial detention for low-level offenses is often causally related to continuing criminal justice involvement. Studies find that pretrial detention is associated with criminal conviction, longer sentences, and imprisonment (Dobbie, Goldin, and Yang, 2018; Heaton, Mayson, and Stevenson, 2017; Stevenson, 2018), and related work finds that pretrial detainees are more likely to later be rearrested (Leslie and Pope, 2017). Under pandemic conditions, ongoing court involvement and incarceration is associated with greater exposure to infection. Taken together, evidence for the overuse of pretrial incarceration for low-risk defendants and extra-legal disparities by race and economic status suggest that reductions in the jail population are possible with little negative effect on crime.

An issue particularly relevant to criteria for decarceration during COVID-19 is that individuals who are at high-risk for COVID-related complications and mortality due to advanced age and comorbid health conditions tend to be serving long prison sentences for a serious violent offense. Releasing individuals convicted of serious violent offenses is often politically fraught. Such releases may be viewed as undermining the retributive purpose of the sentence and may turn public opinion against policy makers in cases of reoffending. Hence, policy reform discussions and even policy design often exclude individuals convicted of violent offenses from consideration, regardless of objective assessment of the risk posed by such individuals.

This exclusion in the policy reform discussions poses specific challenges to release policies that prioritize individuals at high medical risk during COVID-19. Research on how recidivism varies by conviction can inform this discussion. Prescott, Pyle, and Starr (2020) review research on recidivism rates for individuals convicted of violent crimes and how they compare to people convicted of nonviolent crimes. The authors also present new analysis of data from the National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP). The review of past research generally finds individuals in prison convicted of violent offenses, including those convicted of murder, consistently have lower recidivism rates relative to individuals convicted of

nonviolent offenses. In their analysis of NCRP data, the authors find that individuals convicted of murder are somewhat more likely to be returned to prison custody for a new murder relative to otherwise comparable releases, though the recidivism rate for this crime for all individuals is low. Interestingly, the authors find that people convicted of violent offenses have lower overall recidivism rates for all age groups compared with individuals convicted of nonviolent offenses, though the recidivism rates are particularly lower for people 55 and over.

Research also indicates that the prison population in some states can be drawn down quickly by limiting returns to custody for technical parole violations. The 2011 experience in California can prove instructive in this regard. Reforms to parole practice caused a sharp and permanent decline in prison admissions, from roughly 2,200 a week to roughly 500 a week. Interestingly, releases, which also hovered at around 2,200 a week prior to the reform, also dropped to match the lower level of weekly admissions, although with a lag (Lofstrom and Raphael, 2016). The effect of the permanent and sharp decline in admissions together with the lagged alignment of releases was a decline in the prison population by nearly one-fifth and much smaller flows of individuals into and out of the state’s prisons. There is no evidence of an impact of this change on violent crime, although there is some evidence of a relatively small effect on property crime (Lofstrom and Raphael, 2016).

Sustained declines in crime and incarceration have been observed in other cities and states over the past two decades. In New York City, the incarceration rate declined by 55 percent from 1996 to 2014 while violent crime fell in this period 54 percent (Greene and Schiraldi, 2016). Similar trends can be seen in Michigan, where the prison population declined by 20 percent from 2006 to 2016, with corresponding declines in both violent (-19%) and property (-41%) crimes (Schrantz, DeBor, and Mauer, 2018). Connecticut, Mississippi, New York, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and South Carolina achieved similar prison population reductions and also experienced falls in crime rates (Mauer and Ghandnoosh, 2015; Schrantz, DeBor, and Mauer, 2018). Although causality is difficult to disentangle, these states’ experiences suggest that incarceration can be reduced without necessarily increasing crime.

Implications of Recidivism Evidence for Responding to COVID-19

Recidivism research suggests that there is substantial heterogeneity among incarcerated people and that correctional authorities could decarcerate in a number of ways that would minimize public safety risk if given the flexibility to do so. Such flexibility could include diverting from jail, releasing incarcerated people most at risk for COVID-19 complications

and mortality, and limiting return to custody for technical parole and probation violations. Like release, diversion based on considerations of future offending will inevitably result in cases of individuals who are released committing new crimes, as well as cases where individuals who would not reoffend are either not diverted or not released. That there is harm in both directions is often a point that is lost in public discussions of public safety. In the context of a public health crisis and the need to create the capacity to implement physical distancing protocols and not overwhelm correctional medical facilities, correctional authorities will need to use all the available information to devise population reduction strategies across jails and prisons that minimize the likely impacts on crime rates.

PRISON AND JAIL DEPOPULATION IN 2020

Prisons, jails, and immigration detention facilities have all experienced declines in population during the COVID-19 pandemic. A national overview of the decline in incarceration since the onset of the pandemic is provided by Franco-Paredes and colleagues (2020). Based on their own compilation and data from the Vera Institute of Justice, they find that the incarcerated population declined by about 250,000 from the pre-pandemic period to July/August 2020, a decline of more than 10 percent of the total incarcerated population. Jails contributed nearly two-thirds to the total decline in incarceration, and jail populations fell by more than 20 percent. State prisons also registered population decline, but of less than 5 percent3 (see Table 3-1).

There are two ways to reduce the population of jails and prisons: by diverting from custody people who would otherwise be incarcerated and by releasing those already incarcerated. Since the start of the pandemic, public officials across the country have pursued both strategies. This section outlines some of the approaches that have been used to reduce the number of people in custody in both prisons and jails through diversion and release efforts. The discussion here represents only a sampling of the efforts under way; given the many initiatives being undertaken in real time at the federal, state, and local levels, it is impossible to be comprehensive. The aim of this review is twofold: to emphasize the range of pathways to decarceration

___________________

3 The committee notes, however, that total declines in system-wide populations by themselves may contribute little to mitigating the spread of the virus. For example, if the state of Pennsylvania incarcerated 100,000 people in January 2020 and released 20,000 in March 2020, the incarcerated population in Pennsylvania would have declined by 20 percent. However, if the state achieved that population decline by closing two facilities that housed 10,000 individuals each and did nothing to affect the population size of the remaining facilities in its system, the remaining incarcerated individuals would remain at the same risk as they were prior to the 20 percent reduction, if nothing else was changed.

TABLE 3-1 Reductions in Incarcerated Populations from the Pre-Pandemic Period to mid-2020

| Jurisdiction | Period | Pre-Pandemic | In Pandemic | Population Decline | Percent Decline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Prisons | Dec. 31, 2019–May 1, 2020 | 1,260,393 | 1,207,710 | 52,683 | 4.2 |

| Federal Prisons | March 5, 2020–August 13, 2020 | 175,315 | 156,968 | 18,347 | 10.5 |

| Jails | Dec. 31, 2018–July 22, 2020 | 738,400 | 575,952 | 162,448 | 22.0 |

| Immigration (ICE) | March 20, 2020–Aug. 8, 2020 | 37,888 | 21,118 | 16,770 | 44.3 |

| Total | 2,211,996 | 1,961,748 | 250,248 | 11.3 |

NOTE: ICE, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

SOURCE: Adapted from Franco-Paredes et al. (2020, p. 2). Reprinted from The Lancet, September 29, 2020, Franco-Paredes et al., Decarceration and community re-entry in the COVID-19 era, p. 2, 2020, with permission from Elsevier.

and to identify obstacles that may prevent officials from undertaking more far-reaching decarceration efforts.

Despite the constraints of current law and criminal justice policy, prisons and jails across the country experienced population declines as the pandemic spread. The COVID-19 crisis in correctional facilities was acute, but these population reductions likely improved the health environments inside penal facilities. How large were they, and how were they achieved?

Diversion from Jail

In early 2020, as the risk of viral spread in crowded facilities became clear, local officials around the country took steps to reduce the number of people housed in and churning through their jails.4 In East Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Fort Worth, Texas, for example, law enforcement officers stopped arresting people for most misdemeanors and, instead, issued citations for low-level offenses (D’Angelo, 2020; Skene, 2020). In Racine County, Wisconsin, the sheriff’s office restricted admission to the jail to

___________________

4 During this same period, some state prison systems also halted or limited intake (e.g., Wisconsin; see https://madison.com/wsj/news/local/crime-and-courts/wisconsin-gov-tonyevers-halting-prison-admissions-to-prevent-covid/article_032e01f1-931c-5347-9e96-b9dd2894248a.html). But because the people affected were bound for state prison, these efforts merely created a backlog in county jails. It is therefore only diversionary efforts at the local level, which prevent the intake of new arrivals into jails, that would reduce population density in carceral facilities as a whole.

those individuals suspected of violent crimes (Mauk, 2020). In Maine, the chiefs of the state’s superior and district courts issued an order vacating more than 12,000 outstanding warrants for failure to appear or any unpaid fines or fees (State of Maine, 2020), and in South Carolina, the state supreme court directed courts not to issue bench warrants for failure to appear and to release without bond anyone charged with a noncapital crime (Chief Justice Beatty, 2020).

While fine-grained correctional data for the first 8 months of 2020 are not systematically available, several new data collection efforts help illuminate recent trends. The Jail Data Initiative (JDI) at New York University’s Public Safety Lab has collected publicly available jail counts each day at the county level by scraping public databases. As of September 2020, the data file included populations in 1,034 jails across the country. Several large jurisdictions, such as New York City, Los Angeles County, and Cook County, Illinois, are missing from the data collection in the critical period through the first half of 2020. Despite these limitations, the data provide a broad overview of jail trends in the first months of the pandemic.

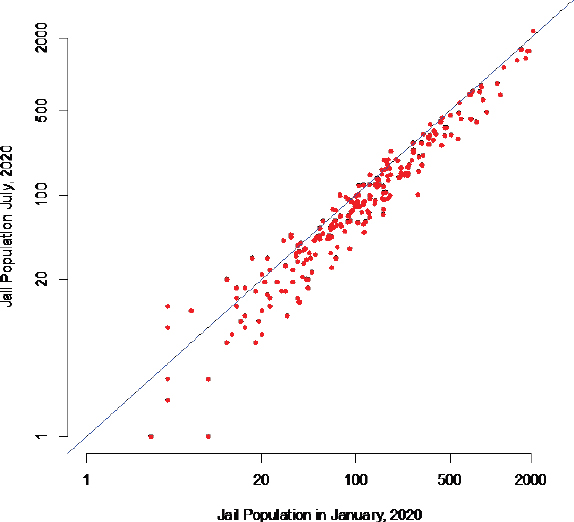

Using these data, the committee examined jail populations in all counties for which data had been reported as of March 15, 2020, and July 31, 2020—a total of 553 local jurisdictions. These counties accounted for 145,000 incarcerated people, about 19 percent of the midyear jail population in 2019. Figure 3-1 shows the jail population plotted on the log scale on July 31 against that on March 15. Almost 88 percent of the jails in the database recorded declines in population during this period, falling below the 45-degree line. Declines in the jail population were recorded in both small and large facilities, with the reduction in population averaging 22 percent in the 4 months from March to July. Information on large jurisdictions not included in the database also shows similar population reductions at jails in New York City; Cook County, Illinois; and Los Angeles County.

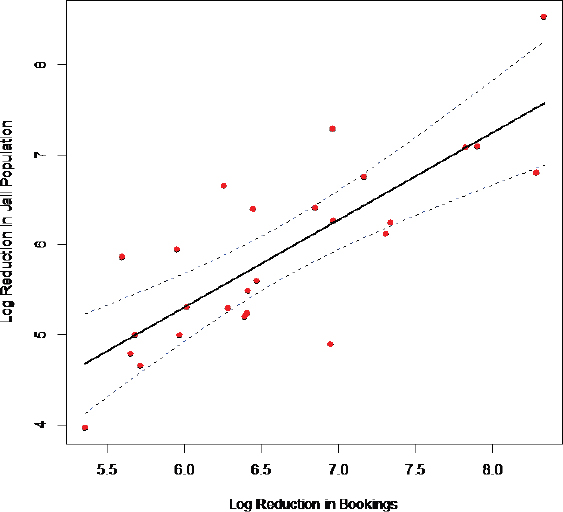

The JDI database offers few clues as to why the jail population fell so much in such a short period, but information from the much smaller sample of the Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC) at the MacArthur Foundation provides useful detail.5 In the 26 jurisdictions reporting data, the jail population declined by 27 percent on average from February to June 2020. The SJC data also record bookings into jail that result from police arrests, not from any diversion from incarceration at court. Figure 3-2 plots the log decline in the number of bookings against the log decline in the jail population. The close relationship between the decline in bookings and the decline in the jail population suggests that depopulation in those sites was not substantially the result of specific efforts by the courts to divert defendants from jail un-

___________________

5 SJC is a jail reform project working in local jurisdictions and collecting detailed data on jail population dynamics.

SOURCE: Data from Jail Data Initiative (2020).

der pandemic conditions. Instead, under the stay-at-home guidance widely adopted across the counties, both criminal activity and arrests by police slowed significantly, and the caseloads in the courts were greatly reduced.

The SJC sites in the study adopted measures in the areas of policing, case processing, pretrial release, and probation that aimed to reduce COVID-19 exposure in the initial stages of the criminal justice system. Police in the SJC sites broadly attempted to resolve situations in the field without making arrests. This involved making increased use of citations and suspending arrests for traffic and misdemeanor warrants. Many counties released defendants facing nonviolent charges on a bond or to pretrial supervision. In around half the counties, parole and probation offices relaxed incarceration for technical violations. Still, some efforts to ease court activity tended to reverse the move to jail depopulation. Trials and hearings were widely postponed. As a result, lengths of stay in jail tended to increase for those already incarcerated. Indeed, lengths of stay in jail increased in more than half of the SJC sites, suggesting that defendants awaiting trial before the onset of the pandemic remained incarcerated as activity in the criminal courts slowed.

These examples suggest that law enforcement officers have played an important role in reducing jail admissions, but other actors can also con-

NOTE: The regression line summarizes the relationship.

SOURCE: Data from MacArthur Foundation (2020).

tribute to diversion. Prosecutors could also decide to decline to seek pretrial detention in all but the most serious cases. Law enforcement officers might thus be deterred from arresting people they might otherwise have brought into jail. Judges, too, could exercise their discretion to refrain from ordering the pretrial detention of people who come before them. Judges could curtail the use of bail and increase the number of defendants released on their own recognizance. In sentencing, judges could also use noncustodial sanctions for probation violations and misdemeanor offenses.6

Release

The picture with respect to releases is more complicated. Here, the difference between jails and prisons matters greatly. As noted in Chapter 2, these institutions house different populations. Jails are waystations, most often housing people who are awaiting trial, are awaiting sentencing,

___________________

6 In cases where people have not been incarcerated prior to their hearings, these actions serve the goal of diversion rather than release.

have committed probation violations, or are serving short sentences for misdemeanors.7 By contrast, prisons are places where people go to stay: they house people serving sentences for felonies, which are crimes that carry sentences of more than 1 year in prison. The discussion below turns first to available levers for releasing people from jail and then to mechanisms for releasing people from prisons. As detailed below, prisons face the strongest legal and political pressures to retain people in custody and, as a result, obstacles to meaningful decarceration for prisons are greatest. Indeed, there is little evidence that release efforts have occurred on a large scale since the pandemic’s inception. Of those releases that have occurred, little demographic data as to the race and ethnicity of releasees are available. Without attention to racial equity, experts in correctional health have raised concerns that pandemic responses could exacerbate racial disparities (see Chapter 5). For example, Illinois and Connecticut provide some of the only available data and preliminary reports that find that decarceration of Whites has been substantially higher than that of Blacks during the COVID-19 pandemic (Franco-Paredes et al., 2020; Hoerner and Ballesteros, 2020; Lyons, 2020).

Jails

During the first months of the pandemic, some public officials acted to depopulate their local jails. In San Francisco, for example, the district attorney ordered prosecutors not to oppose motions to release people facing misdemeanor charges or felony drug charges absent evidence that they posed a public safety threat (BondGraham, 2020). In Los Angeles, the sheriff ordered the release of 1,700 people who had been sentenced to jail time for nonviolent offenses and had less than 30 days left to serve (Carissimo, 2020). And in New York City, the mayor ordered the release of 300 elderly, medically compromised individuals from Rikers Island (Budryk, 2020). In several cases, similar releases from county jails were the product of collaborative efforts among various officials.8 Higher state courts may also direct

___________________

7 Jails may also house people on immigration holds. Reductions in this subset of the jail population would depend on actions by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) or by the municipal agencies that act in concert with ICE.

8 In Washington County, Arkansas, local jail officials pursued collaborative strategies to reduce their jail populations, working with local prosecutors and circuit judges to release approximately 150 people on home monitoring and seeking (and receiving) state approval to release 33 people serving 90-day sentences on technical parole violations (Sissom, 2020). In New Jersey, following mediation involving the Office of the Attorney General, the County Prosecutors Association, the Office of the Public Defender, and the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey, the state’s supreme court ordered the release of anyone serving time in jail as a condition of probation, on a probation violation, pursuant to a municipal court conviction, or for a misdemeanor (Supreme Court of New Jersey, 2020).

trial courts to noncustodial sentences, and district attorneys may choose to endorse them rather than advocating for bond requirements or custodial sentences. Sheriffs often have legal authority to release people from pretrial detention or to release, prior to the expiration of their sentences, people who are serving short sentences for misdemeanor offenses. Depending on the jurisdiction, mayors, too, may have the authority to release people from incarceration.

Prisons

Several officials possess legal authority to release people serving prison time. Many governors (or, in the case of the federal system, the President) can use their pardon or commutation power to reduce judicially imposed sentences.9 Parole boards, often acting in concert with departments of corrections, can grant parole or issue medical furloughs.10 Courts can order releases as remediation for constitutional violations, and in the federal system, can entertain and grant petitions for compassionate release brought by people in the custody of the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). In addition, legislatures can exercise their inherent authority to revise prison sentences imposed pursuant to the state’s sentencing laws.

Available data on imprisonment show a trend toward declining incarceration of approximately 4 percent in state prisons and roughly 10 percent in federal prisons (Franco-Paredes et al., 2020). Because the numbers of new bookings into jail and new cases at court slowed dramatically, particularly as the pandemic spread rapidly in March and April 2020, it appears likely that prison admissions during this period also slowed significantly. The data suggest that prisons were receiving significantly fewer new commitments from courts in this period. Although this appears to be a likely explanation, research is needed to explain prison depopulation when more complete data become available.

___________________

9 In California, for example, the governor accelerated by up to 60 days the releases of 3,500 people who had already been found suitable for parole but were awaiting expiration of the statutory waiting period (St. John, 2020). Similarly, in Kentucky, the governor commuted the sentences of more than 900 people serving prison sentences for nonviolent, nonsexual crimes (Planalp, 2020). And in Pennsylvania, the governor used his reprieve power to accelerate the releases of more than 400 people with medical conditions that put them at high risk of complications from the virus (Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Office of the Governor, 2020).

10 In North Dakota, for example, the state’s parole board held a special session at the outbreak of the pandemic and granted early parole release to 120 individuals (Baumgarten, 2020; Martin, 2020). In early June, the Arkansas Board of Corrections certified more than 1,200 people as eligible for parole consideration. As of early July, 730 people had been released from Arkansas prisons, leaving that state’s prison system roughly at capacity for the first time since 2007 (Arkansas Department of Correction, 2020).

Anecdotal reports from correctional leaders suggest that state prison systems tried to reduce populations through parole release, compassionate release, and home monitoring, but there is little evidence that these efforts occurred on a large scale. Barriers to implementing these release mechanisms likely stem from the fact that everyone in prison has been sentenced to a custodial term following a criminal conviction, and few legal mechanisms are available for releasing people from imprisonment. Moreover, those mechanisms that are available follow a penological model that creates a strong presumption against release prior to the expiration of a sentence. As a consequence, the percentage of people released from prison in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic has been considerably lower than the percentage released from jails.

Barriers to Exercising Discretionary Release Powers

In April 2020, Attorney General William Barr issued a memorandum directing BOP officials to prioritize the use of home confinement, to release, “where appropriate,” those individuals who both are vulnerable to COVID-19 and pose a low public safety threat (Office of the Attorney General, 2020). According to BOP, more than 7,600 people have been released under this guidance since this memorandum was issued (BOP, 2020).11

While some states have taken steps to reduce their prison populations, as described above, the overall effect has been relatively small. Governors and parole boards appear to be hampered in taking such steps by several factors: processes not designed for exigent circumstances; concern about risks to public safety, understood largely in terms of crime prevention; and concerns about public reactions and backlash. As a consequence, review of release petitions at all levels is slow and painstaking, and such factors as the original offense of conviction remain highly salient, even for people who have been incarcerated for decades and are now elderly or physically infirm and thus pose little risk of recidivism.

The power to grant compassionate release is even more limited. In 2018, Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM) conducted a comprehensive review of all state compassionate release regimes. It found that, although “49 states plus the District of Columbia provide one or more forms of compassionate release,” these regimes are rarely used. The

___________________

11 According to Prescott, Pyle, and Starr (2020), “on March 26, Attorney General William Barr issued a memo urging federal prisons to transfer older and medically vulnerable prisoners to home confinement—but it was limited to those with nonviolent offenses who were deemed low-risk.” The authors note that by April 3, 2020, only 552 incarcerated people had been released, out of approximately 175,000 people living in BOP facilities. A subsequent April 2020 memo made the requirements more flexible and more people were released.

FAMM report identifies several obstacles to the granting of compassionate release petitions. including “strict or vague eligibility requirements; categorical exclusions; missing or contrary guidance; complex and time-consuming review processes; and unrealistic time frames” (Price, 2018). To be eligible in Mississippi, for example, the petitioner must be “bedridden.” Georgia requires showing that people are “entirely incapacitated” and “reasonably expected” to die within 1 year. In California, “medical parole” is restricted to those people who are “permanently medically incapacitated, unable to perform activities of daily living,” and who “require constant care.” In Kansas, a person must be projected to die within 30 days. In many states, even people whose medical conditions fall within the ambit of the regulations may still be denied on the basis of their crimes or unless they have served a minimum term. Procedures are often unclear and time-consuming for incarcerated people in terminally poor health. In states where the final decision is made by the parole board, a body typically focused on punishment and evidence of rehabilitation and not on the needs or vulnerabilities of those seeking release, a decision to grant compassionate release is rare. Together, these features explain why compassionate release has historically been so rarely granted and why it has not proved a meaningful channel for release from state prisons during the pandemic.

Federal prisons have taken a different path with compassionate release since the onset of the pandemic. The majority of petitions for compassionate release filed by federal prisoners have been denied, but a non-negligible number—approximately 1,495—have been granted. The reason for this relatively broader use of compassionate release is the greater scope for advocacy the federal system allows on behalf of vulnerable individuals in federal custody. In the vast majority of states, parole boards make compassionate release decisions, but in the federal system these decisions are made by federal courts. Prior to passage of the First Step Act of 2018, only the BOP director could petition the court to reduce a prison sentence for reasons of age, medical condition, family circumstance, or some other “extraordinary or compelling reason,”12 as long as the director had determined that the individual seeking release was “not a danger to the safety of any other person or to the community.” While the First Step Act did not change the factors a court considers, it granted those seeking release the right to bring the matter to court themselves. Petitioners must still first file a request with the warden in their facility, but if BOP does not bring a motion for release to the federal courts within

___________________

12 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A); United States Sentencing Guidelines Manual § 1B1.13.

30 days, petitioners can now file such a motion themselves.13 This procedural change has brought the increased use of compassionate release. In the year prior to passage of the First Step Act, the federal courts granted only 24 motions for compassionate release; in the year after passage, that number was 145.

Despite the increase in motions for compassionate release, the court’s criteria for assessing such a petition are unchanged. Whether a motion is brought by the BOP director or the person seeking release, the court must take account of the sentencing factors listed in the law (18 USC § 3553), which include “the nature and circumstances of the offense and the history… of the defendant,” as well as the various purposes of punishment, including the need “to reflect the seriousness of the offense, to promote respect for the law, and to provide just punishment for the offense”; to “afford adequate deterrence to criminal conduct”; and to “protect the public from further crimes of the defendant.”14 These factors are the same considerations federal courts use when sentencing people convicted of crimes. Because federal courts are statutorily obliged to consider them when entertaining a compassionate release petition, these factors continue to narrow the possibility of prison release regardless of how much time a person may have already served or however strong the public health grounds for release. Box 3-1 further describes the role of federal courts in releases.

In sum, there is evidence of a decline in incarceration in the first half of 2020, though this appears to be largely due to declines in crime, arrests, and court processing rather than deliberate efforts at depopulation in response to the pandemic. While prison and jail populations fell, there is also evidence of an increase in incarceration in the period from June 2020 to the time of this writing in October 2020, as cities and courts begin to reopen. Figures are incomplete and highly preliminary, but the data scraping effort at JDI reports rising incarceration in the 348 jails they have been tracking since March 2020. For those 348 jails, they find the total population was at a minimum for 2020 on May 2, at 57,305. By October 4, the population had increased to 70,350.15 The increase in incarceration combined with high rates of daily new infections underscores the continuing need for mechanisms for decarceration in support of public health.

___________________

13 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A).

14 The statute also lists as relevant the need “to provide the defendant with needed educational or vocational training, medical care, or other correctional treatment in the most effective manner” (18 USC § 3553).

CONCLUSION

Available data on changes in the incarcerated population since the onset to the pandemic show that total prison populations have declined by roughly 5 percent nationwide and total jail populations have declined by roughly 20

percent. While noteworthy, diversion efforts have largely been the results of decreases in criminal activity, arrests by law enforcement, and court processing. Releases have generally been procedurally slow (due to requirements to consider individual circumstances on a case-by-case basis) and not well-suited for addressing crisis conditions. Reports of continued outbreaks in correctional facilities across the country suggest additional efforts are needed, specifically on a system and facility-by-facility basis.

Furthermore, the committee’s review of research on recidivism and legal analysis of diversion and jail and prison release have two main implications. First, it is possible to reduce incarceration significantly without a large increase in crime. Prior to the pandemic, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Connecticut sustained large reductions in prison populations, while crime rates in those states fell or remained at historically low levels. Perhaps the most relevant example is provided by California, where the policy of realignment adopted in response to court order to bring down the state’s prison population reduced the number of people in prison rapidly by about one-third, with no measurable effect on violent crime.

Second, despite the feasibility of decarceration from the viewpoint of public safety and its desirability from the perspective of public health, there is too little scope in current law for accelerating releases for public health reasons. Indeed, medical or health criteria for release, even in pandemic emergencies, are largely nonexistent at the state level and highly circumscribed in the federal system. For correctional officials to implement decarceration, steps can be taken to mitigate public safety and public health risks through reentry planning and the provision of supports, including testing upon release, which is the focus of the next chapter.

This page intentionally left blank.