4

STI Economics, Public-Sector Financing, and Program Policy

INTRODUCTION

To offer recommendations for future public health programs, policy, and research, it is important to understand the historical experience and current status of public efforts to respond to sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Several findings emerged from the committee’s review of

STI prevention and control efforts in the United States (see Box 4-1). First, despite evidence that the burden of STIs has potentially increased, federal funding to address STIs has remained stagnant. In addition, state funding as a share of total funding has decreased, reflecting a decline in funding at the state level in absolute terms. Finally, current methods and resources for tracking progress in decreasing the rates of STIs are inadequate or nonexistent.

These findings reflect a lack of programmatic coordination in how the United States addresses STIs at the federal, state, and local levels and within its health care and public health systems. A highly fragmented patchwork of programs has resulted in a lack of timely and consistent data on overall funding investments, creating difficulty in tracking progress of and investment in prevention and control efforts over time. In addition, progress in other outcomes has also been difficult to measure. For example, recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) studies estimated the prevalence and incidence of many STIs and their associated direct medical costs in 2018 (Chesson et al., 2017; Kreisel et al., 2021). This was the first update to both estimates in the past 10 years. Because of data limitations and changes in methodology, however, these estimates cannot be compared over time. Thus, whether the investments in STI programs and research are truly providing value and decreasing the burden of STIs is difficult to ascertain.

Finally, the fragmentation of U.S. efforts has resulted in a lack of information on how control and prevention efforts are prioritized and measured within the federal government and by state and local public health departments. If measuring and quantifying change signal the importance of progress toward the intended outcomes, then the inability

or unwillingness to measure change reflects a lack of importance or prioritization and will considerably hinder progress.

This chapter describes current federal and state programs that finance and deliver STI screening, prevention, and treatment services and support STI research and provides an overview of the economic burden of STIs in the United States. The committee does not offer specific funding recommendations as it was beyond the scope of its work; however, the chapter points to funding barriers and opportunities for STI prevention and control.

ROLE OF GOVERNMENT IN PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF STIs

An important starting point to understanding the legal and operational underpinnings of how the current system addresses STIs is to examine which level of government is responsible for STIs and public health and how the leadership and financing for STI programs has evolved. In the United States, STI prevention activities fall into two arenas, with diagnosis and treatment mostly occurring at the local level and surveillance activities and partner services mostly (with exceptions in larger cities) funded and coordinated at the federal and state levels.

Cooperative Federalism and Public Health

The 10th Amendment to the Constitution helps to define federal and state government powers and responsibilities under the U.S. system of federalism. It reserves to state governments the power and primary responsibility for protecting the public health of their respective populations (NCSL, 2014). The Constitution’s Commerce Clause, however, gives the federal government certain authority to order quarantines or take other measures in response to a public health threat, such as an infectious disease transmitted across state borders. Nonetheless, most state–federal relations in the public health context operate under what is called cooperative federalism: federal policy makers may seek to achieve uniform national policies and practices through funding state efforts. Instead of attempting to compel states to take actions (for which the Constitution may not grant the authority), they provide federal funding and condition these funds on states’ taking specific actions, but states’ acceptance of such funding remains voluntary.

Public health is nested within this cooperative federalism construct as a state responsibility with federal input and partial funding through CDC, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and

others. In its most recent funding announcement for state STI programs, for example, CDC states that as a condition of receiving federal funding, “all applicants are required to implement a program of core STD prevention and control strategies and activities across the public health functions of assessment, assurance, and policy development,” with more specific conditions articulated in the announcement (grants.gov, 2018).

While states retain responsibility for public health and state health officials are essential leaders in responding to STIs, the current state–federal partnership has evolved away from the Founders’ intention expressed by cooperative federalism. Given that the federal government is such a dominant funder of STI and other public health programs, yet it is still faced with large variations in the scope and quality of STI services across the states, it is questionable whether cooperative federalism is working in this context. Governors and other state officials could assert their constitutional prerogatives for public health yet also excuse shortcomings by blaming inadequate federal funding. While it is beyond the scope of this committee to make recommendations on whether the current federal–state funding dynamic is consistent with the ideals of the Constitution, a broader evaluation of the role and relative contributions of states in enhancing STI and other public health responses may be necessary.

OVERVIEW OF FEDERAL PROGRAMS

Background

STI control efforts are supported through a combination of private and public funds, including private insurance payments, public coverage programs like Medicaid, and out-of-pocket expenditures for billed clinical services. Similarly, numerous federal, state, and local funding streams support STI prevention efforts, either as a standalone program or as a part of other health services funding programs (e.g., Title X funding for family planning and Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act [PHSA] for HRSA funding for qualifying health centers). Reports by the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA), commissioned by the National Coalition of STD Directors (NCSD), provide a comprehensive overview of these funding streams (NAPA, 2018, 2019).

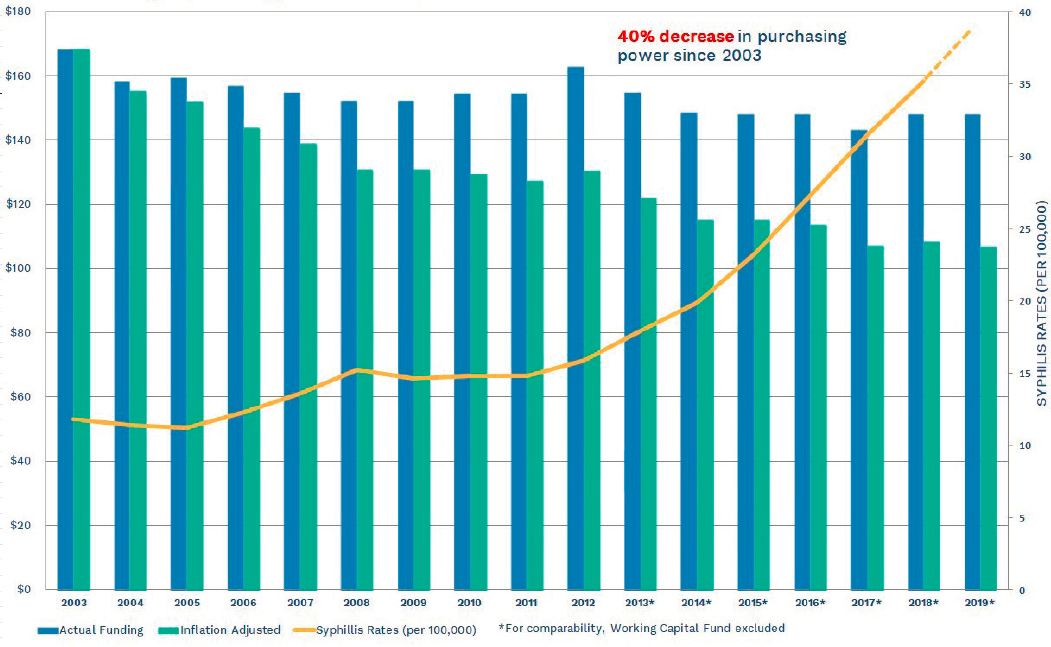

The only federal categorical funding stream specifically dedicated to STI prevention and control is authorized by Section 318 of the PHSA and primarily administrated by the Division of STD Prevention (DSTDP) in the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention at CDC. Current funding for CDC’s STI programs has been level for many years at approximately $157 million (with the 2020 budget

increasing slightly to $160.8 million); after adjustment for inflation, this is a reduction of about 40 percent since 2003 (NAPA, 2018).

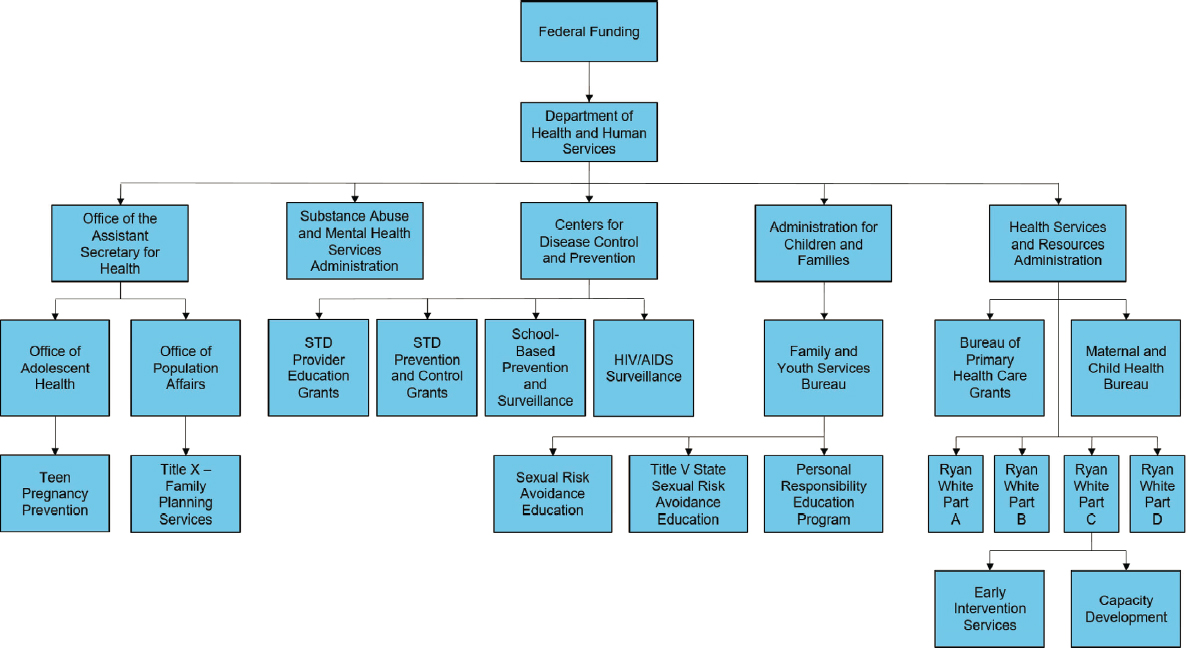

The vast majority of national and community-level programs to address STIs are supported by components of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) (see Figure 4-1). Its primary functions include (1) data surveillance; (2) prevention and control programs, including direct health care provision; (3) workforce development and capacity building; and (4) research and evaluation. In addition, coverage programs like Medicare and Medicaid, as well as private insurance, finance clinical services and treatment for most U.S. residents. Many uninsured individuals have access to screening, testing, and treatment services through a network of clinics and safety-net providers that are supported largely through the government-funded programs discussed below. This fragmented system leaves many without affordable and accessible opportunities for regular STI services and perpetuates the transmission of these preventable conditions.

Overview of Federally Funded Public Health Programs

Most federal support for STI services is provided by HHS and underpins the operation of a wide range of programs funded and administered by CDC, the HHS Office of Population Affairs (OPA), HRSA, SAMHSA, the Indian Health Service (IHS), the National Institutes of Health, and public coverage programs, including Medicaid and Medicare through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (see Figure 4-1). This section provides an overview of public programs (both within and outside of HHS) that support STI surveillance, training, and research and discusses public and private support of programs that finance services to prevent, screen for, and treat STIs. A comprehensive review is also available in the 2019 NAPA report The STD Epidemic in America: The Frontline Struggle (NAPA, 2019).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

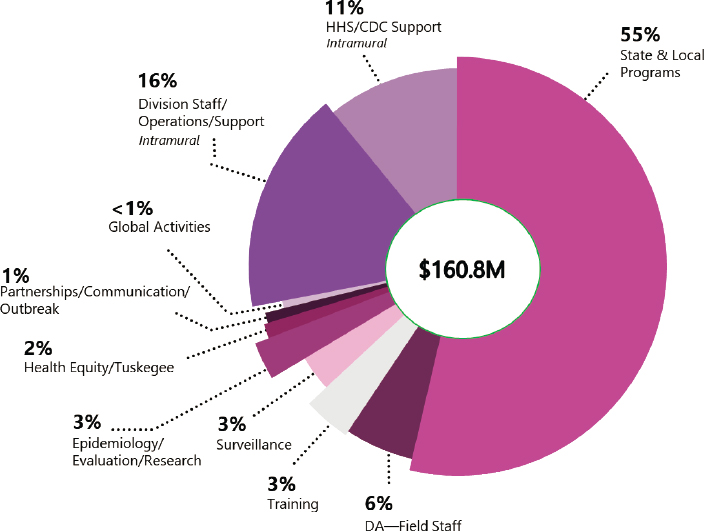

Despite the increase in STI rates, federal funding for CDC programs that support STI services over the past 10 years has been level (as noted, after adjustment for inflation, this reflects a 40 percent reduction since 2003) (see Figure 4-2). DSTDP oversees all STI programs operated by CDC. The majority of funding goes toward state and local program grants and staffing. A small share of the STI budget goes toward workforce training, data surveillance, and research and evaluation (see Figure 4-3). CDC’s current STI goals include (1) eliminating congenital syphilis and preventing primary and secondary syphilis, (2) preventing antimicrobial-resistant

SOURCE: Adapted from NAPA, 2019, to reflect organization as of December 2020.

SOURCE: NCSD, 2019.

NOTES: Developed by CDC for this report; supporting data are available by request via the project Public Access File via email at publicac@nas.edu. CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DA = direct assistance; HHS = Department of Health and Human Services.

gonorrhea, and (3) preventing STI-related pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility (NAPA, 2018). Given its limited resources, DSTDP has defined its primary responsibilities as encompassing “assessment, assurance, policy development, and prevention strategies” (CDC, 2017a). Primary responsibility for STI research and treatment is viewed as outside of its purview, and while CDC is not primarily responsible for directly providing clinical services, it does seek to ensure that clinical services exist, along with local health departments.

CDC programming is primarily focused in the following areas:

- Evidence-based scientific information for providers, public health professionals, and patients and communities: CDC develops provider guidelines including Recommendations for Providing Quality Sexually Transmitted Diseases Clinical Services

- (Barrow et al., 2020), Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines (Workowski and Bolan, 2015), and Provider Pocket Guides (CDC, 2015). Patient education/community outreach includes online/printable brochures (CDC, 2016b), fact sheets (CDC, 2016a), infographics (CDC, 2020j), and STD Awareness Week (CDC, 2020h).

- STI surveillance to assess the burden, outcomes, and costs of STIs: CDC conducts annual surveillance of reportable STIs (CDC, 2019c). It provides the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention AtlasPlus tool so users can build custom reports from these surveillance files (CDC, 2019a). CDC also tracks the antimicrobial-resistant bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae through the STD Surveillance Network (CDC, 2016d) and the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (CDC, 2020e). In addition, CDC helps publish action plans on antibiotic-resistant bacteria, such as the National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria report that sets goals to maintain the prevalence of ceftriaxone-resistant gonorrhea below 2 percent, maintain capacity for rapid response to antimicrobial resistance, and support surveillance efforts (Federal Task Force on Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria, 2015, 2020).

- Funding for state and local prevention and control programs: In addition to basic program support, CDC provides targeted funding to address particular issues or public health priorities. For example, the Strengthening STD Prevention and Control for Health Departments program provides cooperative agreements/grants to state, local, and territorial health departments to address chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis (CDC, 2018). Another example is the Community Approaches to Reducing STDs initiative, which funds recipients to address STI health equity (CDC, 2020a) (see Chapter 8 for more information). CDC also helps providers implement Project Connect, an intervention that aims to increase youth access to sexual and reproductive health care (CDC, 2020g). CDC offers several tools for program management and evaluation (CDC, 2019b), including program evaluation training (NCSD, 2020), a gap assessment toolkit (CDC, 2016c), and effective interventions guidelines (CDC, 2020b). Through the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases’ Vaccines for Children Program, CDC also buys (at a discount) and distributes vaccines, including for hepatitis B and human papillomavirus (HPV), recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, to its grantees to provide free vaccination for children younger than 19 years of age and who are

- Medicaid eligible, uninsured, underinsured, and/or American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) (CDC, 2016f).

- Workforce development and capacity building: CDC funds multiple training opportunities (CDC, 2013), including in-person training for public and private providers at the STD Clinical Prevention Training Centers (PTCs) (CDC, 2017b). Several online learning tools are also available, including webinars for clinicians, physicians, and public health practitioners (CDC, 2016e) and the online National STD Curriculum, which offers continuing education credits upon completion (CDC, 2020f). Through the PTCs, CDC also funds the STD Clinical Consultation Network, which provides expert consultation to providers who need assistance with complex clinical cases (National STD Curriculum, n.d.). (See Chapter 11 for more information on STI workforce development.)

- Research and evaluation: A small fraction of CDC’s budget supports STI research on the priority populations of adolescents and young adults, men who have sex with men, transgender persons, and pregnant persons and on STI vaccines, therapeutics, and point-of-care diagnostics. CDC collaborates with professional associations, such as the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), to conduct surveys to assess the level of publicly funded STI services offered at the state and local levels (NAPA, 2018). Every 2 years, CDC hosts an STI prevention conference, bringing together scientific evidence in the field (CDC, 2020i).

Office of Population Affairs

HHS’s OPA plays an important role in supporting STI prevention and treatment services for low-income individuals through grants for family planning services at sites throughout the country and guidance on providing family planning services.

OPA’s primary responsibility has been to administer the Title X Family Planning program, which supports clinical family planning services (including STI and HIV prevention education, counseling, and testing) at sites nationwide that serve low-income patients (OPA, 2020). The most current Title X regulation defines family planning services to

include preconception counseling, education, and general reproductive and fertility health care, in order to improve maternal and infant outcomes, and the health of women, men, and adolescents who seek family planning services, and the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infections and diseases which may threaten childbearing capability or the health of the individual, sexual partners, and potential future children. (GPO, 2019)

The regulation also notes that programs are permitted, but not required, to “diagnose, test for, and treat STDs” (Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, 2020).

Clinics that have participated in the program include federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), state and county health departments, Planned Parenthood clinics, and specialized family planning providers. Participating sites receive federal support and are eligible for the federal 340B drug pricing program (see the relevant later section in this chapter for more details).

The Title X program underwent significant changes in 2019 as a result of new regulations that block Title X support to clinics that provide abortion services and referrals in addition to family planning and STI services. Participating sites fell from 4,515 in 2009 to approximately 3,825 in 2019 (OPA, 2020). The new regulations have not only resulted in these sites losing funding available to provide low-income individuals with contraceptive services but also may have affected the availability of clinics that continue to offer free or low-cost STI testing and treatment services in many communities. The new regulations opened the door for organizations that do not provide contraception or even condoms to receive federal family planning funds, limiting their services to abstinence or natural family planning. Patients who are tested and treated for STIs at these new Title X-funded sites are not given condoms but rather prescribed abstinence for prevention (Varney, 2019).

Family planning clinic users who obtained services from supported providers fell by 21 percent from 2018 to 2019 (OPA, 2020). There was also a reduction in both the number and share of users (both men and women) who had chlamydia and gonorrhea tests (OPA, 2020). Information on STI treatment and referral, however, is not available. In addition to losing federal funding, some sites that have withdrawn from the program can no longer qualify for 340B discounts, which enabled clinics to offset the cost of medications.

In partnership with CDC, OPA published recommendations for Providing Quality Family Planning Services, which includes STI and HIV testing and treatment guidelines. Family planning providers are recommended to assess the patient’s reproductive life plan, screen patients for STIs based on risk, provide HPV vaccines, treat patients with STIs and their partner(s), and provide risk counseling for sexual behavior risk reduction (CDC, 2014). OPA also oversees activities regarding adolescents and sexual and reproductive health and funds the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program (TPP), which has about 65 grantees and a budget of about $101 million (OPA, n.d.-b). The TPP provides up to 3-year grants to implement interventions that aim to improve adolescent health, prevent teen pregnancy, and reduce STIs. OPA also hosts resources and training for providers working with adolescents and STIs (OPA, n.d.-a).

Despite its importance in financing publicly funded family planning services for low-income populations, the Title X program is small, with a budget of $286 million in 2019; over the past decade, the program has shrunk in actual and constant dollars (OPA, 2021). To put this in context, between 2008 and 2018, health care costs increased by 21.6 percent (Claxton et al., 2018). The reduced Title X funding has also been associated with reductions in the number of people who have been served by clinics receiving support from the program (OPA, 2020). On January 28, 2021, President Biden ordered a review of the 2019 Title X rule, but any changes would require notice-and-comment rulemaking, meaning that they could not be immediately put into effect (The White House, 2021).

Health Resources and Services Administration

HRSA is largely responsible for supporting services to medically underserved and rural communities and oversees several divisions and programs that work on STI prevention and treatment, including the Women’s Preventive Services Guidelines, which include recommendations for behavioral counseling for all sexually active adolescents and adult women at increased risk for STIs (HRSA, 2020e).

340B Drug Pricing Program

This is a drug discount program administered by HRSA’s Office of Pharmacy Affairs. Its purpose is “to stretch scarce federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services” (HRSA, 2020a). By design, the 340B program helps to subsidize the operations of safety-net providers by permitting them to obtain discounted outpatient pharmaceuticals and retain higher reimbursements, when available, from private insurance, Medicare, and, in some states, Medicaid.

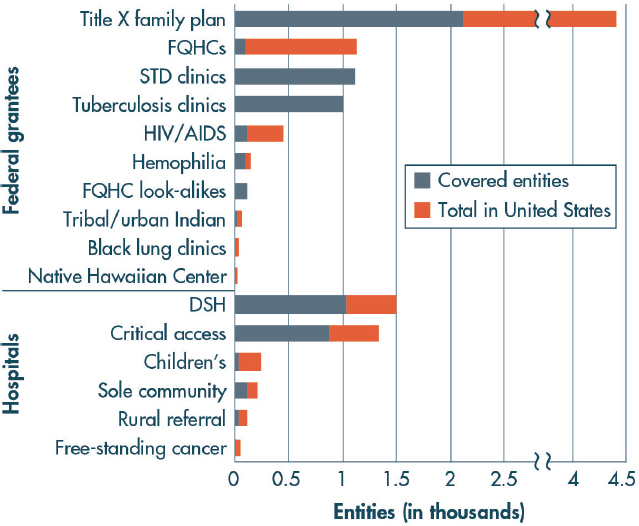

The 340B program is not a health coverage program, but it enables eligible participants to generate revenue that can be used to extend coverage to more people or enhance the scope of services offered. Only nonprofit health care organizations that have a certain federal designation or receive funding from specific federal programs can be considered “eligible entities.” Figure 4-4 shows the categories of covered entities and their 2014 participation rates.

STI clinics that receive funding from CDC under Section 318 of the PHSA are eligible recipients, as are FQHCs, Ryan White HIV/AIDS program grantees, and sites that receive Title X family planning funding (HRSA, 2020c). They must apply to HRSA to participate, and once accepted, these “covered entities” can purchase drugs at prices that are the same as or lower (often significantly lower) than the Medicaid rebate price. Currently, 3,226 STI clinics participate in the 340B program (HRSA, n.d.).

NOTE: DSH = disproportionate share hospital; FQHC = federally qualified health center; STD = sexually transmitted disease.

SOURCE: Mulcahy et al., 2014.

Covered entities cannot resell or transfer drugs to other entities. Although the clinic or health provider is defined as 340B eligible, the outpatient drug discount can only be secured for “eligible patients,” defined by federal rules as those who meet the following criteria:

- Have an established relationship with the covered entity, as demonstrated by the covered entity maintaining a medical record for the patient;

- Receive services from a health care professional who is either employed by the covered entity or provides health care under contractual or other arrangements (e.g., referral for consultation) such that responsibility for the care provided remains with the covered entity; and

- Receive a service or a range of services from the covered entity, which is consistent with the grant funding or the FQHC lookalike status that has been provided to the entity (GPO, 1996).

While there is no formal guidance, if a patient meets the 340B patient definition at a visit and tests positive for an STI, then 340B-acquired drugs may be used for them and expedited partner therapy (EPT) (see Chapters 7 and 10 for more on expedited partner therapy). The rationale is that EPT actually treats the eligible patient because it prevents reinfection (FPNTC, 2017; NFPRHA, 2019).

The required discount is either 13 percent (generic) or 23.1 percent (brand name) from the average manufacturer price. Additional discounts are also required if the manufacturer has chosen to increase the price faster than the rate of inflation and/or offers a lower price to certain other purchasers. Manufacturers also may voluntarily offer deeper discounts. Manufacturers are prohibited from providing a discounted 340B price and Medicaid drug rebate for the same drug.

In addition to the program providing the most deeply discounted prices for medications, an important advantage has been allowing covered entities to bill payers (Medicare, private insurance, and decreasingly Medicaid programs) the regular reimbursement rates for drugs and receive reimbursement greater than their costs. For many clinics and programs, the difference between the payment and reimbursement is a significant revenue generator. This revenue must be used consistent with the purpose of the 340B-qualifying program (for STI clinics, this is the purpose of CDC funding), such as to serve more low-income people in need of sexual health services or provide a broader range or higher level of services (Schwartz, 2015). Some 340B entities have expressed concerns that this policy has been interpreted overly restrictively, so the current restrictions may merit reconsideration. For example, Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program recipients have been precluded from using 340B income for pre-exposure prophylaxis and other preventive services (HRSA, 2016). Furthermore, others have claimed that the lack of clear guidance acknowledging that EPT is a permissible use of 340B income has limited the effectiveness of the program in supporting this critical public health purpose (FPNTC, 2017; Golden and Estcourt, 2011; NFPHRA, 2019). As the distinctions between treatment and prevention blur, wherein effective prevention reduces the need for HIV treatment services within a community, these entities believe that the purpose of the grant in the context of the 340B program could be interpreted more broadly to enable providers to serve more individuals in need of services.

Bureau of Primary Health

The bureau administers the Health Center Program, which provides grants to support primary care and related services through a network of more than 1,400 health centers that operate at about 12,000 service delivery sites in every state, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories (McDevitt, 2019). In addition to receiving federal

grants, FQHCs also qualify for the 340B discount drug program, are reimbursed using an enhanced Medicare and Medicaid payment system, qualify for Health Professional Shortage Area designation, and may obtain clinicians through the National Health Service Corps. Certain health centers located in medically underserved communities are designated federal “look-alike” status; they do not receive federal grants, but they offer the same range of services as FQHCs and qualify for the other benefits granted to FQHCs discussed above (HRSA, 2018). According to HRSA, more than 28 million people were seen at HRSA-funded health centers in 2019 (McDevitt, 2019). Health centers serve individuals regardless of ability to pay or immigration status. Participating clinics are required to provide primary care services; it is assumed that STI services would be included, but the terms of participation do not specify prevention, testing, and treatment of STIs other than HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C (McDevitt, 2019). The Uniform Data System, the database that tracks the number and types of services that health centers provide, reports 376,840 visits for STI services and 256,203 visits with an STI diagnosis in 2018.1

Maternal and Child Health Bureau

The bureau administers the Title V Maternal and Child Health Program, a block grant to improve maternal, child, and family health. Title V goals include improving maternal and child health (through improved access, quality, and prevention) for low-income women (HRSA, 2020d). The program provides grants for Sexual Risk Avoidance Education, whose regulations require that education heavily focus on sexual risk avoidance rather than risk reduction strategies (i.e., STI education) (FYSB, 2020; SSA, n.d.). For more information on sexual education in schools, see Chapter 8.

CDC/HRSA Advisory Committee on HIV, Viral Hepatitis, and STD Prevention and Treatment

The committee is a collaboration between CDC and HRSA, currently focusing on HIV and opioids.

HRSA HIV/AIDS Bureau

The bureau administers the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, which “provides a comprehensive system of HIV primary medical care, essential support services, and medications for low-income people living with HIV who are uninsured and underserved” (HRSA, 2020b). This program funds health care services for individuals living with HIV and also supports other STI services for low-income people with HIV or at risk. See Chapter 5 for information on the intersection of HIV and STIs.

___________________

1 Data obtained from the HRSA National Health Center Data website. See https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/data-reporting/program-data/national (accessed October 20, 2020).

Indian Health Service

IHS, an operating division of HHS, is responsible for providing direct clinical services, including STI care, to AI/AN individuals. IHS partners with CDC on STI prevention and control, outreach and educational programming, and data surveillance (IHS and CDC, 2018). For information on the challenges and opportunities related to STIs for AI/AN people, see Chapter 3.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

SAMHSA collaborates with other governmental organizations (including CDC and HRSA) on co-occurring mental illness and STIs. It also publishes practice guidelines and data surveillance related to STIs and mental health. Its STI-related resources include the following:

- Data Spotlight: a brief that highlights data on colocation of substance abuse treatment and STI screening (SAMHSA, 2013)

- SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions: Supporting Clients in Sexual Health: a brief for providers on the overlap among sexual, behavioral, and mental health (SAMHSA, 2017)

- Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) 37: Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons with HIV/AIDS (SAMHSA, 2000)

- TIP 42: Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons with Co-Occurring Disorders (SAMHSA, 2020)

- TIP 51: Substance Abuse Treatment: Addressing the Specific Needs of Women (SAMHSA, 2009)

Department of Defense and Department of Veterans Affairs

The Department of Defense (DOD) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) run several programs that address STIs among service members and their dependents and for veterans. Active-duty service members and veterans receive health care, including STI care, through TRICARE and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Additionally, DOD oversees the following two programs in data surveillance and clinical research affecting active-duty members of the military.

Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center

The center monitors and evaluates surveillance data in the military, including STIs, using the Defense Medical Surveillance System and produces a medical surveillance monthly report based on trends in health-related conditions.

Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program

The program supports clinical research in the military health system, including STI-related studies, such as the GC Resistance Study and the GC Reference Laboratory and Repository study (IDCRP, n.d.). One goal is to support STI prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Veterans Health Administration

The VHA served approximately 2.8 million working-age veterans in 2016; about one-quarter (732,000) did not have any other health coverage and used the VA as their only source of coverage. The remaining VA population has employer insurance, individually purchased coverage, Medicaid, or other government coverage (TRICARE or Medicare). Because eligibility is based on veteran status, service-connected disability status, income level, and other factors, not all veterans qualify for VA care (Holder and Day, 2017). The VA offers a wide range of services, including STI screening and testing.

Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Prisons

The Federal Bureau of Prisons, an agency under the Department of Justice, is responsible for providing direct clinical services, including STI care, to individuals in the federal prison system. It also publishes clinical guidelines for preventing and treating STIs in prison settings, such as the following:

- The Infectious Disease Management Program Statement states that (1) all inmates entering bureau facilities will receive education on viral hepatitis and STIs, including general review of current information on transmission, treatment, and prevention, and (2) testing for viral hepatitis and STIs is performed based on clinical indicators and guidance from the medical director (BOP, 2014).

- The Preventative Health Care Screening Clinical Guidance offers screening and testing guidance for HIV, hepatitis C, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and HPV (BOP, 2018).

- The Clinical Practice Guidelines include guides available for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV management, and medical management of exposures (including sexual exposures) (BOP, n.d.).

- The Inmate Information Handbook has a section on STIs that includes frequently asked questions (BOP, 2012).

STATE AND LOCAL EFFORTS

While much of the on-the-ground work to tackle STIs happens at the state and local levels, the vast majority of funding comes from the federal government and coverage programs, such as Medicaid and private insurance. At the state level, formula funding from CDC is mostly used to support STI surveillance and epidemiology and provide partner services. Some states support local public health programs in their jurisdictions, but Section 318 of the PHSA does not specifically authorize the direct provision of STI diagnostic and treatment services. Recipients of the Strengthening STD Prevention and Control for Health Departments (PCHD) cooperative agreements, authorized by Section 318, can spend no more than 10 percent of their funding on direct STI services, unless special approval is obtained.

PCHD-funded programs are relatively well aligned and coordinated with one another for three reasons. First, they all respond to the same grant provisions and associated performance measures. Second, they receive designated supports from expert staff in DSTDP’s program, surveillance, and epidemiology branches. Finally, they are represented by a very active and well-resourced nonprofit organization, NCSD, which advocates for them with CDC and with Congress.

Such cohesiveness, however, is lacking at the local level, where most of the frontline STI services occur. There are no categorical STI funding streams that benefit local public health programs, other than flow-through funding from PCHD grantees, especially in states where the state health departments are directly in charge of local STI programs. In addition, local STI programs and clinics depend on a number of other funding sources, including city/county and state transfers (often bundled with other funding); Title X family planning grants; Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program funding; HRSA’s Health Center Program (authorized by Section 330 of the PHSA) that includes funding for FQHCs; and the 340B program. Besides fragmented funding, the quality of local STI programs further depends on local leadership and academic affiliations. As a result of this patchwork of resources, program quality varies greatly. Some have evolved into STI centers of excellence and been able to attract additional resources as training and research centers, whereas others have floundered and clinics have closed. Public funding for STI services appears to be declining in the past decade; in a study of local health departments from 2013 to 2014, 61.5 percent reported recent budget cuts. This means that clinics sometimes needed to decrease hours (42.8 percent), decrease routine screening (40.2 percent) and partner services (42 percent), and increase fees or copays (25 percent) (Leichliter et al., 2017). Other data have shown similar consequences of budget cuts; funding reductions have also caused decreasing

numbers of staff and clinicians and STD clinic closures (NAPA, 2019). Unfortunately, some of the areas with the highest morbidity have the fewest resources.

Important support for local STI programs and clinics comes from the CDC-funded National Network of STD Prevention Training Centers, consisting of eight regional centers that provide STI workforce training and technical assistance (Stoner et al., 2019). (See Chapter 11 for more information.) In addition, NCSD has recently stepped up to develop an STI clinic initiative, “Reimagining STD Clinics for the Future,” which advocates for public and private STI clinics and envisions ultimately developing a “community of practice” for STI clinics. These are important resources; they are, however, insufficiently funded to cover current technical assistance and workforce development needs and do not directly address funding levels for clinical operation (NAPA, 2019). Thus, much more needs to be done to reverse the downward spiral many STI clinics are experiencing and shore up the front lines in STI prevention.

Less commonly, nongovernmental organizations offer funding opportunities. For example, one of the focus areas for NACCHO, consisting of nearly 3,000 local health departments, is to support local health departments in addressing STIs. NACCHO partners with CDC to offer Local Innovations in Congenital Syphilis Prevention, which provides at least five health departments with up to $25,000 to decrease congenital syphilis in their areas (Horowitz, 2019). With funding from CDC, NACCHO also conducts the Supporting the Delivery of Quality STD Services project to support the use of CDC STI recommendations at local health departments and the STI Express Initiative to assess evidence for “express STI visits” or “fast-tracking” STI services (NACCHO, 2019; Rodgers, 2019). In addition, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials works to support state and territorial health departments in preventing and responding to STIs, in collaboration with CDC and other partners. It has published resources, including National STD Trends (ASTHO, 2019), which outlines key STI information for public health leadership; Investing in STD Prevention (ASTHO, 2018), which helps local actors make the case for STI funding; and other resources for how to integrate STI prevention into public health and primary care models (ASTHO, n.d.).

Given the critical importance of providing STI care at the local level for STI prevention nationally, action needs to be taken to reverse these trends. Elsewhere in this report (see Chapter 12), specific suggestions are made toward increasing local community planning for STI prevention, strengthening the role of STI clinics in cities and selected nonurban areas, and developing STI prevention and care resource centers in every state.

ECONOMIC BURDEN OF STIs

As part of its Statement of Task, the committee was asked to examine—to the extent possible—the economic burden associated with STIs. While the literature on this is not extensive, a CDC study (Chesson et al., 2021) estimated the lifetime medical costs of incident cases of eight STIs in 2018 in the United States: Chlamydia trachomatis (chlamydia), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrhea), Trichomonas vaginalis (trichomoniasis), Treponema pallidum (syphilis), genital herpes (due to herpes simplex virus type 2), HPV, and hepatitis B virus and HIV attributed to sexual transmission. With the exception of HPV, the study estimated the direct medical cost burden of each STI by multiplying the lifetime medical costs per infection of treating each STI and its sequelae with the number of incident cases of each STI in 2018. The estimates of cases and costs were obtained from existing peer-reviewed studies.

The lifetime medical care costs per infection varied: from $5 for trichomoniasis to more than $420,000 for HIV for men and from $36 for trichomoniasis to more than $420,000 for HIV for women (Chesson et al., 2021). The incidence in 2018 also varied; fortunately, incidence was inversely related to lifetime costs per infection. For example, there were more than 7 million incident cases of trichomoniasis but fewer than 37,000 incident cases of HIV (HIV.gov, 2020).

The study estimated that the total lifetime direct medical cost of incident STIs in the United States in 2018 was almost $16.0 billion (25th–75th percentile: $14.9–$16.9 billion). HIV accounted for the vast majority of this, at $13.7 billion, followed by $1 billion for chlamydia and gonorrhea combined and $0.8 billion for HPV. Excluding HIV, the lifetime cost of incident STIs was $2.2 billion. The majority of this burden was borne by women, at about $1.6 billion excluding HIV. Youth also accounted for a significant fraction of total lifetime costs: $4.2 billion (25th–75th percentile: $3.9–$4.5 billion) for persons aged 15–24 years, of which about $3.0 billion was for HIV, $0.6 billion for chlamydia and gonorrhea combined, and $0.4 billion for HPV (Chesson et al., 2021).

While the lifetime medical care costs of incident STIs in 2018 are high in absolute terms, they are small relative to total health care spending in the United States. In 2019, total health care spending was $3.8 trillion (CMS, 2020), so incident STIs accounted for less than 1 percent. However, the lifetime medical care costs of STIs might vastly underestimate the true disease burden. STIs impose costs not only in terms of dollars spent on health care but also by influencing the quality of life of people who are infected or currently uninfected but might be at risk in the future. For those who are infected, the costs include not only the lifetime medical costs of treating STIs but also the loss in quality of life due to the health

and social consequences of living with the STI. Measuring the long-term impacts of STIs and their sequelae on quality of life might be challenging (Weatherly et al., 2009). Some prior studies have addressed these challenges and suggest that the loss in quality of life from STI infection can be significant (Chesson et al., 2017; Jackson et al., 2014; Ong et al., 2019; Tran et al., 2015).

STIs also can impose significant costs on the uninfected. These costs are often ignored because they are difficult to measure, but they could be much higher than the direct medical costs of STIs. The committee commissioned a pilot study2 to explore methods that could be used to help quantify the impact of STIs on the quality of life of the uninfected, which could arise through multiple channels. For example, people might worry about getting an STI due to present sexual activity. This worry or anxiety might reduce quality of life in the present. Such concerns could also lead people to change sexual behaviors, such as having fewer sexual partners and being more likely to wear condoms, which might lead to less enjoyable sexual experiences.

The commissioned pilot study used an innovative application of a well-established strategy called the “time trade-off” method to measure the impact of STIs on quality of life (Muennig and Bounthavong, 2016; Torrance and Feeny, 1989). The goal is to find out how many years of life people are willing to give up to eliminate the risk of STIs. For example, if people are indifferent, on average, about living 10 years of life with their current STI risk and living 9 years with no STI risk, that implies that people are willing to give up 1 out of 10 years to eliminate the risk of STIs. This implies that the risk reduces quality of life by 0.1 quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

The pilot study, while preliminary, shows that the time trade-off method produces reasonable estimates of the loss of QALYs due to risk of STIs. For example, the QALY loss was higher for people who worry more about getting STIs; those that were very worried about getting an STI suffered a QALY loss of 0.39 years, and the somewhat worried lost 0.21 years. Similarly, QALY loss from STIs was higher for those who practice riskier sexual behavior and thus face a higher risk of STIs. The QALY loss was robust to alternate techniques for measuring it.

A separate nationally representative survey also commissioned by the committee and conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation showed that 3 percent of the U.S. population was very worried and 5 percent somewhat worried about STIs (Kirzinger et al., 2020). Combining these results with the QALY loss for each group suggests that the current risk

___________________

2 The pilot survey questions are available by request via the project Public Access File email at publicac@nas.edu.

of STIs for those who are uninfected but worried about an STI results in a loss of close to 6 million QALYs. Prior research suggests that 1 QALY is at least worth $100,000 (Hirth et al., 2000; Ubel et al., 2003). This implies that the risk of STIs among those worried or somewhat worried about it imposes a quality of life loss valued at about $600 billion. These studies are preliminary, and more refined methods might alter the results.

Overall, the review of studies on costs or burden of STIs shows that eliminating STI risk can generate significant economic value through reducing direct medical costs and improving quality of life for people both with and without infections. Other chapters in this report and a recent issue of Sexually Transmitted Diseases discuss several proven and promising interventions for STI prevention (CDC, 2020c). Juxtaposing the two facts suggests that implementing these interventions and scaling up efforts to prevent STIs can generate tremendous economic value.

CONCLUSIONS

DSTDP has been basically flat-funded for years and, adjusting for inflation, has lost approximately 40 percent of its purchasing power since 2003 (NAPA, 2019). Similarly, at the local level, many STI programs have curtailed their services due to lack of funding or programmatic changes in policy, as is the case for the Title X program, even though increased health care coverage due to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act may be increasing access to STI care. In a survey, the majority of local health departments (61.5 percent) reported recent budget cuts. Of those with decreased budgets, the most common impacts were reductions in clinic hours (42.8 percent), routine screening (40.2 percent), and partner services (42.1 percent) (Leichliter et al., 2017).

Conclusion 4-1: While the reasons for the increases in STI rates are multi-factorial, experts have suggested that STI rises are in part a symptom of insufficient public health infrastructure, particularly at the local level. The countervailing trends between rising STI rates and stagnant public health funding on STIs require a careful re-examination of the current STI prevention infrastructure and levels of STI care.

Conclusion 4-2: Efforts to address and curb the growing threats posed by STIs require an urgent response to reinforce the existing public health infrastructure for providing sexual health and STI health services.

There are many opportunities to improve local and state capacity to address STIs. For example, CDC could develop a new funding mechanism to support dedicated sexual health clinics. These clinics would ideally

exist in all cities and nonurban areas that are underserved and provide walk-in comprehensive sexual health treatment and care to explicitly seek to serve the highest morbidity and underserved populations to address inequities. Grants provided by CDC in 2019 to strengthen the infrastructure of STD clinics serving a high volume of racial and sexual minorities to enhance and scale up HIV prevention services in three local clinics (Baltimore City, DeKalb County, and East Baton Rouge Parish) under the Ending the HIV Epidemic program represent an example of this type of funding (CDC, 2020d). Another example would be to expand funding for state and local epidemiologic capacity related to STIs, which would fill another important need, including funding for cities (not only states) to monitor STI epidemiology and service provision at the local level. To do so, the current relationship between CDC and states and cities may need to be revised (see Chapter 12 for recommendations on STI surveillance). To overcome barriers related to capacity in this area, CDC would need to send trained epidemiologists to local health departments or foster new collaborations to expand epidemiologic capacity in the long term. While there are many financial barriers to overcome, doing so is necessary to implement the needed changes outlined later in this report.

REFERENCES

ASTHO (Association of State and Territorial Health Officials). 2018. Investing in STD prevention: Making the case for your jurisdiction. https://www.astho.org/generickey/GenericKeyDetails.aspx?contentid=20314&folderid=5150&catid=7184 (accessed December 31, 2020).

ASTHO. 2019. National STD trends: Key information on sexually transmitted diseases for public health leadership. Arlington, VA: Association of State and Territorial Health Officials.

ASTHO. n.d. Public health and healthcare integration for STD prevention. https://www.astho.org/Programs/Infectious-Disease/Hepatitis-HIV-STD-TB/Sexually-Transmitted-Diseases/Integration-Webinar-Series (accessed December 9, 2020).

Barrow, R. Y., F. Ahmed, G. A. Bolan, and K. A. Workowski. 2020. Recommendations for providing quality sexually transmitted diseases clinical services, 2020. MMWR Recommendations and Reports 68(5):1-20.

BOP (Federal Bureau of Prisons). 2012. Inmate information handbook. https://www.bop.gov/locations/institutions/spg/SPG_aohandbook.pdf (accessed November 19, 2020).

BOP. 2014. Infectious disease management. https://www.bop.gov/policy/progstat/6190_004.pdf (accessed November 19, 2020).

BOP. 2018. Preventive health care screening. Clinical guidance. https://www.bop.gov/resources/pdfs/phc.pdf (accessed November 19, 2020).

BOP. n.d. Health management resources. https://www.bop.gov/resources/health_care_mngmt.jsp (accessed November 19, 2020).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2013. Sexually transmitted diseases: Training. https://www.cdc.gov/std/training/default.htm (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2014. Update: Providing quality family planning services—recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 63(4):231-234.

CDC. 2015. STD treatment guidelines pocket guide. https://www.cdc.gov/std/products/provider-pocket-guides.htm (accessed November 17, 2020).

CDC. 2016a. CDC fact sheets. https://www.cdc.gov/std/healthcomm/fact_sheets.htm (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2016b. The facts brochures. https://www.cdc.gov/std/healthcomm/the-facts.htm (accessed November 19, 2020).

CDC. 2016c. STD preventive services gap assessment toolkit. https://www.cdc.gov/std/program/gap/default.htm (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2016d. STD surveillance network (SSuN). https://www.cdc.gov/std/ssun/default.htm (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2016e. STD webinars. https://www.cdc.gov/std/training/webinars.htm (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2016f. Vaccines for children program (VFC). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/index.html (accessed November 17, 2020).

CDC. 2017a. Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). About the division of STD prevention. Strategic summary. https://www.cdc.gov/std/dstdp/strategic-summary.html (accessed June 24, 2020).

CDC. 2017b. STD clinical prevention training centers. https://nnptc.org (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2018. NOFO: Ps19-1901 strengthening STD prevention and control for health departments (STD PCHD). https://www.cdc.gov/std/funding/pchd/default.htm (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2019a. NCHHSTP AtlasPlus. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/atlas/index.htm?s_cid=bb-od-atlasplus_002 (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2019b. Program management & evaluation tools. https://www.cdc.gov/std/program/default.htm (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2019c. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services.

CDC. 2020a. Community approaches to reducing sexually transmitted diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/std/health-disparities/cars.htm (accessed October 25, 2020).

CDC. 2020b. Effective interventions. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/effective-interventions/index.html (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2020c. Effective interventions. https://www.cdc.gov/std/program/interventions.htm (accessed January 26, 2021).

CDC. 2020d. Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE): Scaling up HIV prevention services in STD specialty clinics. https://www.cdc.gov/std/projects/ehe/default.htm (accessed February 3, 2021).

CDC. 2020e. Gonococcal isolate surveillance project (GISP). https://www.cdc.gov/std/gisp/default.htm (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2020f. National STD curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2020g. Project CONNECT. https://www.cdc.gov/std/projects/connect/default.htm (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2020h. STD awareness week. https://www.cdc.gov/std/saw (accessed November 19, 2020).

CDC. 2020i. STD prevention conference. https://www.cdc.gov/stdconference/default.htm (accessed November 18, 2020).

CDC. 2020j. STD prevention infographics. https://www.cdc.gov/std/products/infographics.htm (accessed November 17, 2020).

Chesson, H. W., P. Mayaud, and S. O. Aral. 2017. Sexually transmitted infections: Impact and cost-effectiveness of prevention. In Major infectious diseases, edited by K. K. Holmes, S. Bertozzi, B. R. Bloom, and P. Jha. Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. Pp. 203-232.

Chesson, H. W., I. H. Spicknall, A. Bingham, M. Brisson, S. T. Eppink, P. G. Farnham, K. M. Kreisel, S. Kumar, J.-F. Laprise, T. A. Peterman, H. Roberts, and T. L. Gift. 2021. The estimated direct lifetime medical costs of sexually transmitted infections acquired in the United States in 2018. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001380.

Claxton, G., M. Rae, L. Levitt, and C. Cox. 2018. How have healthcare prices grown in the U.S. over time? https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/how-have-health-care-prices-grown-in-the-u-s-over-time (accessed January 22, 2021).

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2020. National health expenditure data. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical (accessed February 11, 2021).

Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. 2020. Electronic code of federal regulations. Title 42: Public health. Part 59—grants for family planning services. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=9e7d4b25c907ce15ad3499765fe34bd3&mc=true&node=pt42.1.59&rgn=div5 (accessed October 20, 2020).

Federal Task Force on Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. 2015. National action plan for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Agriculture, and Department of Defense.

Federal Task Force on Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. 2020. National action plan for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria, 2020-2025. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Agriculture, and Department of Defense.

FPNTC (Family Planning National Training Center). 2017. 340B drug pricing program frequently asked questions for Title X family planning agencies. https://www.fpntc.org/sites/default/files/resources/340b_faq_2017-12-08.pdf (accessed June 10, 2020).

FYSB (Family and Youth Services Bureau). 2020. Title V competitive sexual risk avoidance education grant program. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/fysb/title-v-competitive-sexual-risk-avoidance-education-grant-program (accessed November 18, 2020).

Golden, M. R., and C. S. Estcourt. 2011. Barriers to the implementation of expedited partner therapy. Sexually Transmitted Infections 87:ii37-ii38.

GPO (Government Publishing Office). 1996. Health Resources and Services Administration. [0905-za92]. Notice regarding section 602 of the Veterans Health Care Act of 1992 patient and entity eligibility. Federal Register 61(207):55156-55158. http://www.hrsa.gov/opa/programrequirements/federalregisternotices/patientandentityeligibility102496.pdf (accessed June 23, 2020).

GPO. 2019. Department of Health and Human Services. 42 CFR Part 59. [HHS-OS-2018-0008]. Rin 0937-za00. Compliance with statutory program integrity requirements. Federal Register 84(42):7714-7791. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-03-04/pdf/2019-03461.pdf (accessed May 29, 2020).

grants.gov. 2018. CDC-rfa-ps19-1901. Strengthening STD prevention and control for health departments (STD PCHD). Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control—NCHHSTP. https://www.grants.gov/web/grants/view-opportunity.html?oppId=304454 (accessed April 24, 2020).

Hirth, R. A., M. E. Chernew, E. Miller, A. M. Fendrick, and W. G. Weissert. 2000. Willingness to pay for a quality-adjusted life year: In search of a standard. Medical Decision Making 20(3):332-342.

HIV.gov. 2020. Fast facts. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics (accessed October 23, 2020).

Holder, K. A., and J. C. Day. 2017. Health insurance coverage of veterans. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2017/09/health_insurancecov0.html (accessed October 15, 2020).

Horowitz, R. 2019. Request for applications: Local innovations in congenital syphilis prevention. https://www.naccho.org/blog/articles/request-for-applications-local-innovations-in-congenital-syphilis-prevention (accessed November 19, 2020).

HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). 2016. Frequently asked questions. March 21, 2016. Policy clarification notices (PCNs) 15-03 and 15-04. https://hab.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hab/Global/faq15031504.pdf (accessed October 23, 2020).

HRSA. 2018. Health center program look-alikes. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/programopportunities/lookalike/index.html (accessed January 27, 2021).

HRSA. 2020a. 340B drug pricing program. https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/index.html#:~:text=The%20340B%20Program%20enables%20covered,entities%20at%20significantly%20reduced%20prices (accessed June 10, 2020).

HRSA. 2020b. About the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program. https://hab.hrsa.gov/about-ryan-white-hivaids-program/about-ryan-white-hivaids-program (accessed June 23, 2020).

HRSA. 2020c. Sexually transmitted disease clinics. https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/eligibility-and-registration/specialty-clinics/sexually-transmitted-disease/index.html (accessed June 23, 2020).

HRSA. 2020d. Title V maternal and child health services block grant program. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/maternal-child-health-initiatives/title-v-maternal-and-child-health-services-block-grant-program (accessed November 18, 2020).

HRSA. 2020e. Women’s preventive services guidelines. https://www.hrsa.gov/womens-guidelines-2019 (accessed November 8, 2020).

HRSA. n.d. Office of Pharmacy Affairs. 340B OPAIS. https://340bopais.hrsa.gov/CoveredEntitySearch/000032539 (accessed June 10, 2020).

IDCRP (Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program). n.d. Sexually transmitted infections. https://www.idcrp.org/research-area/sexually-transmitted-infections (accessed November 17, 2020).

IHS (Indian Health Service) and CDC. 2018. Indian health surveillance report—sexually transmitted diseases, 2015. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services.

Jackson, L. J., P. Auguste, N. Low, and T. E. Roberts. 2014. Valuing the health states associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infections and their sequelae: A systematic review of economic evaluations and primary studies. Value in Health 17(1):116-130.

Kirzinger, A., C. Muñana, M. Brodie, B. Frederiksen, G. Weigel, U. Ranji, and A. Salganicoff. 2020. KFF polling and policy insights: Abortion and STIs. San Francisco, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Kreisel, K. M., I. H. Spicknall, J. W. Gargano, F. M. Lewis, R. M. Lewis, L. E. Markowitz, H. Roberts, A. S. Johnson, R. Song, S. B. St. Cyr, E. J. Weston, E. A. Torrone, and H. S. Weinstock. 2021. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: Prevelance and incidence estimates, 2018. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001355.

Leichliter, J. S., K. Heyer, T. A. Peterman, M. A. Habel, K. A. Brookmeyer, S. S. Arnold Pang, M. R. Stenger, G. Weiss, and T. L. Gift. 2017. US public sexually transmitted disease clinical services in an era of declining public health funding: 2013-14. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 44(8):505-509.

McDevitt, S. 2019. Powerpoint presentation to the Committee on Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Infections in the United States. Irvine, CA (presented remotely). December 16, 2019. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/12-16-2019/prevention-and-control-of-sexually-transmitted-infections-in-the-united-states-meeting-4 (accessed November 17, 2020).

Muennig, P., and M. Bounthavong. 2016. Cost-effectiveness analyses in health: A practical approach, 3rd edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mulcahy, A. W., C. Armstrong, J. Lewis, and S. Mattke. 2014. The 340B prescription drug discount program: Origins, implementation, and post-reform future. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE121.html (accessed January 15, 2021).

NACCHO (National Association of County and City Health Officials). 2019. Supporting the delivery of quality STD services: A NACCHO project to facilitate implementation of CDC’s recommendations for providing quality STD clinical services. Washington, DC: National Association of County and City Health Officials.

NAPA (National Academy of Public Administration). 2018. The impact of sexually transmitted diseases on the United States: Still hidden, getting worse, can be controlled. Washington, DC: National Academy of Public Administration.

NAPA. 2019. The STD epidemic in America: The frontline struggle. Washington, DC: National Academy of Public Administration.

National STD Curriculum. n.d. STD clinical consultation network. https://www.std.uw.edu/page/site/clinical-consultation (accessed February 11, 2021).

NCSD (National Coalition of STD Directors). 2019. Fifth-straight year of STD increases demands urgent action. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/fifth-straight-year-of-std-increases-demands-urgent-action-300934045.html (accessed January 28, 2021).

NCSD. 2020. STD program evaluation trainings and tools. https://www.ncsddc.org/std-pett (accessed November 18, 2020).

NCSL (National Conference of State Legislatures). 2014. Responsibilities in a public health emergency. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/public-health-chart.aspx (accessed April 24, 2020).

NFPRHA (National Family Planning & Reproductive Health Association). 2019. 340 drug pricing program for family planning providers. NFPRHA winter meeting 2019. https://www.nationalfamilyplanning.org/file/2019-december-meeting-pdfs/12.9---340B-Training.pdf (accessed June 10, 2020).

Ong, K. J., M. Checchi, L. Burns, C. Pavitt, M. J. Postma, and M. Jit. 2019. Systematic review and evidence synthesis of non-cervical human papillomavirus-related disease health system costs and quality of life estimates. Sexually Transmitted Infections 95(1):28-35.

OPA (Office of Population Affairs). 2020. Title X family planning annual report: 2019 national summary. Rockville, MD: Office of Population Affairs.

OPA. 2021. Title X program funding history. https://opa.hhs.gov/grant-programs/archive/title-x-program-funding-history (accessed January 22, 2021).

OPA. n.d.-a. Adolescent health. https://opa.hhs.gov/adolescent-health?adolescent-development/reproductive-health-and-teen-pregnancy/stds/index.html (accessed December 31, 2020).

OPA. n.d.-b. Teen pregnancy prevention (TPP) program. https://opa.hhs.gov/grant-programs/teen-pregnancy-prevention-program-tpp (accessed February 10, 2021).

Rodgers, K. 2019. Executive summary: Supporting the establishment, scale up, and evaluation of STI express services. https://www.naccho.org/blog/articles/executive-summary-supporting-the-establishment-scale-up-and-evaluation-of-sti-express-services (accessed November 19, 2020).

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2000. TIP 37: Substance abuse treatment for persons with HIV/AIDS. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

SAMHSA. 2009. TIP 51: Substance abuse treatment: Addressing the specific needs of women. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

SAMHSA. 2013. Forty-two percent of substance abuse treatment facilities offer on-site screening for infectious diseases. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/spot070-infectious.pdf (accessed November 19, 2020).

SAMHSA. 2017. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions (CIHS). https://www.samhsa.gov/integrated-health-solutions (accessed November 18, 2020).

SAMHSA. 2020. TIP 42: Substance abuse treatment for persons with cooccurring disorders. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Schwartz, K. 2015. New analysis: Who benefits from contract pharmacy arrangements in 340B program? PhRMA. http://catalyst.phrma.org/who-benefits-from-contract-pharmacy-arrangements-in-340b-program (accessed June 23, 2020).

SSA (Social Security Administration). n.d. Title V—maternal and child health services block grant. https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title05/0500.htm (accessed December 31, 2020).

Stoner, B. P., J. Fraze, C. A. Rietmeijer, J. Dyer, A. Gandelman, E. W. Hook, 3rd, C. Johnston, N. M. Neu, A. M. Rompalo, G. Bolan, and National Network of STD Clinical Prevention Training Centers. 2019. The national network of sexually transmitted disease clinical prevention training centers turns 40—a look back, a look ahead. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 46(8):487-492.

The White House. 2021. Fact sheet: President Biden to sign executive orders strengthening Americans’ access to quality, affordable health care. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/28/fact-sheet-president-biden-to-sign-executive-orders-strengthening-americans-access-to-quality-affordable-health-care (accessed January 28, 2021).

Torrance, G. W., and D. Feeny. 1989. Utilities and quality-adjusted life years. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 5(4):559-575.

Tran, B. X., L. H. Nguyen, A. Ohinmaa, R. M. Maher, V. M. Nong, and C. A. Latkin. 2015. Longitudinal and cross sectional assessments of health utility in adults with HIV/AIDS: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Services Research 15(1):7.

Ubel, P. A., R. A. Hirth, M. E. Chernew, and A. M. Fendrick. 2003. What is the price of life and why doesn’t it increase at the rate of inflation? Archives of Internal Medicine 163(14):1637-1641.

Varney, S. 2019. Federally funded Obria prescribes abstinence to stop the spread of STDs. https://californiahealthline.org/news/federally-funded-obria-prescribes-abstinence-to-stop-the-spread-of-stds/#:~:text=But%20Obria%20will%20not%20advocate,according%20to%20the%20group’s%20application (accessed January 22, 2021).

Weatherly, H., M. Drummond, K. Claxton, R. Cookson, B. Ferguson, C. Godfrey, N. Rice, M. Sculpher, and A. Sowden. 2009. Methods for assessing the cost-effectiveness of public health interventions: Key challenges and recommendations. Health Policy 93(2-3):85-92.

Workowski, K. A., and G. A. Bolan. 2015. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recommendations and Reports 64(RR-03):1-137.