INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) cause significant morbidity and mortality in the United States and around the world. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that one in five people in the United States had an STI on any given day in 2018, totaling nearly 68 million estimated infections. Furthermore, an estimated 26 million new STIs occurred in 2018 in the United States (CDC, 2021). Such infections can range in seriousness from no symptoms and no long-lasting harm to severe disability and death. These infections have burdened humankind throughout recorded history and, as with other pathogens, they will continue to evolve in their relationship with humankind. Moving beyond complacency to action for both long-standing and emerging STIs is critically important to the nation. (See Box 1-1 for key STI facts and statistics.)

URGENCY OF ADDRESSING STIs

STIs representing an array of more than 30 viral, bacterial, and protozoal pathogens are among the most common infections affecting humans, with chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis leading the list of notifiable infections in the United States (CDC, 2019b). The long-term sequelae, including infertility, chronic pain, miscarriage or newborn death, as well as the increased risk of HIV infection and sometimes cancer and death mean that these infections have long been identified as public health priorities. Most famously, Surgeon General Dr. Thomas Parran did so in his treatise on syphilis, Shadow on the Land (Parran, 1937). Given the blame, embarrassment, shame, and stigma attached to STIs, compounded by a general uneasiness in discussing sexuality and sexual health in the United States, the STI epidemic has largely remained hidden (see Chapters 2, 3, and 9 for in-depth discussions of stigma and structural factors related to STIs). Nonetheless, over the decades, numerous public and private entities have endorsed the goal of controlling and ultimately eradicating STIs. The United States has seen great scientific progress related to STIs in the past 20 years that has resulted in important public health benefits. This progress demonstrates that efforts to treat and prevent STIs are not futile. Substantial problems remain, however, and progress combating bacterial STIs has made little progress in the past two decades. For example, marginalized groups—youth; women; members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) community; and Black, Latino/a, American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN), and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Island people—continue to experience a disproportionate share of STI cases in the United States. Limitations of the current STI surveillance system are also problematic (see Chapters 2 and 12). This report seeks to address these persistent problems while addressing the issue of STIs in the broader context of sexual health.

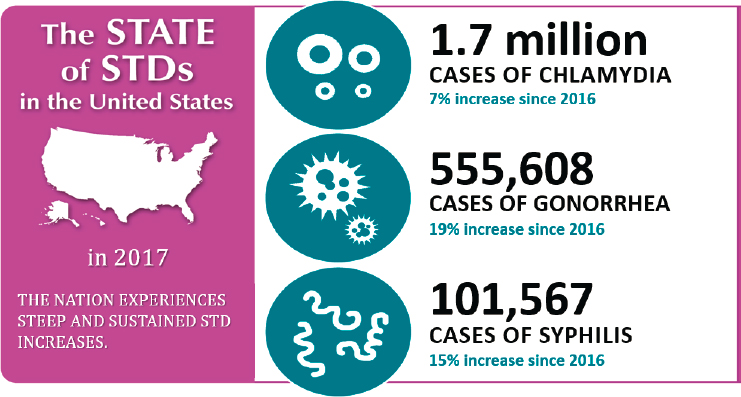

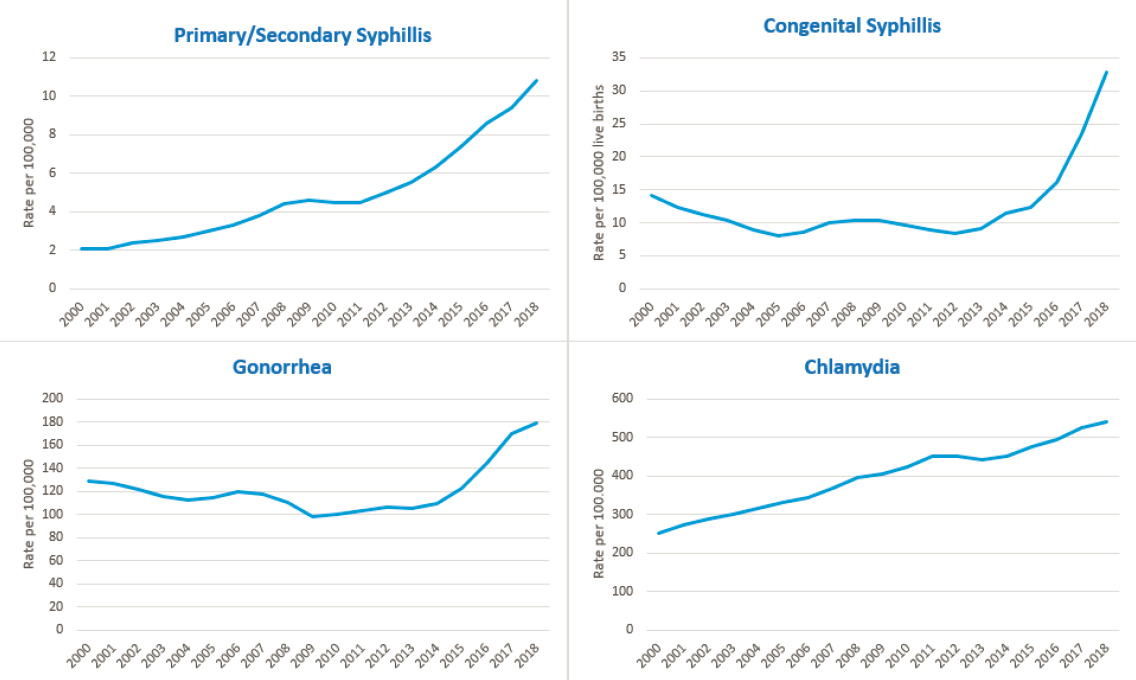

STI rates are increasing; in 2018, combined rates of reported chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis were at an all-time high (see Figures 1-1 and 1-2). These rates underestimate the full scope of the U.S. STI epidemics, in part because many cases can be asymptomatic and therefore go undiagnosed and unreported. Asymptomatic individuals may not know they are infected but can still pass infection to their sexual partners. Furthermore, other STIs of public health significance, such as human papillomavirus (HPV) and herpes simplex virus, are not nationally notifiable conditions; thus, data on these infections are not routinely reported in the same way. The Institute of Medicine released a report, The Hidden Epidemic: Confronting Sexually Transmitted Diseases, more than 20 years ago (in 1997), yet the problems and barriers described there persist today. Furthermore, STIs remain an underfunded and neglected field of practice and research (Unemo et al., 2017). For example, chlamydia, gonorrhea, and

syphilis rates have been on the rise for the past 5 years, with a 44 percent increase in congenital syphilis in 2017 (CDC, 2019d). CDC estimated that incident STIs, including HIV, imposed an estimated $16.0 billion (25th–75th percentile: $15.0–17.1 billion) in lifetime direct medical costs in the United States in 2018 (Chesson et al., 2021) (see Chapter 4 for an in-depth discussion of the U.S. economic burden of STIs).

Given the burden of STIs, CDC, through the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), requested the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to review the current state of STIs in the United States, the economic burden, current public health strategies and programs (including diagnostics, vaccines, monitoring and surveillance, and treatment), and barriers in the health care system. Based on its review, the committee’s mandate was to provide direction for the future of public health programs, policy, and research in STI prevention and control (see Box 1-2 for the full Statement of Task and Appendix E for the committee member biographies).

COMMITTEE’S APPROACH

For purposes of this report, the committee’s review encompasses all STIs; the report’s primary emphasis, however, is on addressing the growing epidemics of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis. These three conditions produce significant morbidity and are nationally reportable conditions for which both diagnostic tools and therapeutics are currently available, and there are current national efforts to reduce the

SOURCE: Bolan, 2019.

SOURCE: Data from CDC, n.d.

impact of them. The committee believes that the framework and recommendations offered in this report will strengthen the response to a broad range of STIs.

Although HIV is an STI, the committee’s charge prevented it from making HIV-specific recommendations (the report sponsors—CDC and NACCHO—asked the committee to focus its recommendations on STIs other than HIV, given the alarming increasing rates of STIs). The impact of the HIV epidemic on STIs in the United States, however, cannot be overlooked. Without treatment, HIV is almost universally fatal, and it continues to pose a serious threat to population health. An estimated 1.2 million U.S. individuals are living with HIV; after decades of concerted effort, annual new infections have fallen from more than 130,000 per year in the mid-1980s to approximately 38,000 in 2018 (CDC, 2016, 2020). Similarly, the number of deaths has declined dramatically from a high of about 50,000 in 1995 to 15,820 deaths by any cause among those with diagnosed HIV infection in 2018 (HIV.gov, 2020). Thus, the committee’s consideration of HIV was focused on understanding the interplay between HIV and the acquisition, transmission, and clinical manifestations of other STIs (see Chapter 5 for more information), as well as considering how current

public health programs at the federal, state, and local levels integrate HIV and STI prevention, care, and research programs.

Furthermore, STIs cannot be addressed without also attending to the root causes of poor health—racism, discrimination, poverty, and health inequity for certain groups, including a lack of access to health care, education, and transportation (Brown et al., 2019; NASEM, 2017). Centering health inequities and structural factors is critical when approaching most health concerns, and the committee discusses and assesses this throughout this report.

The following sections describe the committee’s approach, including the guiding principles and conceptual framework that steered this report.

Ethical Principles Guiding This Report

More than other issues of public health importance, STIs are subject to stigma, misconceptions, discrimination, and differences in values and beliefs about sex and sexuality. The committee therefore relied on several core principles to guide the development of this report. Specifically, the committee considered the ethical concepts of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice and endorses the concepts of sexual health and overall wellness.

Beneficence: Promoting Sexual Health and Wellness

STIs are inherently linked to sexuality and to sexual behaviors fundamental to human existence and a critical source of well-being and pleasure. From that perspective, the committee finds that STIs often reflect the untoward effects of otherwise normal, healthy, and desired behaviors in the context of consensual relationships. Preventing and controlling STIs cannot be considered outside of the larger realm of sexual health. The committee therefore asserts that a framework based on sexual health and well-being is a necessary starting point to guide this report.

Nonmaleficence: Fighting Stigma

STIs have been shrouded in shame, embarrassment, and discrimination, creating stigma with serious consequences at both the societal and individual levels. STI stigma is directly related to a society that holds negative views of sexuality, particularly outside of monogamous, heterosexual relationships. As a result, discussions about sexuality and sexual health are avoided at multiple levels, including within families and schools and even by some health care practitioners. At the individual level, societal stigma shapes individuals’ willingness and knowledge about whether,

how, and where to seek information about and screening for STIs. This may lead to failure to seek recommended screening or vaccination and delays in diagnosis and treatment, resulting in negative health outcomes and the risk of ongoing STI transmission. The committee concludes that unbiased and impartial discussions regarding sexuality, sexual health, and STIs need to occur at all levels of society, including within families, schools, faith communities, and other community settings, especially in clinical encounters. Educational discussions between health care providers and their patients are imperative in the fight against STI-associated stigma.

Autonomy: Respect for Individual Decision Making

The principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence imply the centrality of individual autonomy (i.e., respect for individual sexual decision making and sexual expression free of external coercion, whether by partners, family, friends, figures of authority, or society at large). This principle also requires us to respect the autonomy of a partner and to speak out forcefully against sexual or gender-based violence in all of its aspects (see Chapter 3 for more information on sexual and gender-based violence in relation to STIs).

Justice: Addressing Disparities; Affirming Sexual Rights as Human Rights

The epidemiology of STIs in the United States reveals deep disparities by age, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity, perpetuated by overarching social and economic inequities, racism, and discrimination. These factors are associated with barriers to access to education, health, and prevention services above and beyond the stigma already discussed. Thus, effective interventions to prevent and control STIs also need to address larger social and sexual health inequities. The committee concludes that efforts to eliminate STIs need to be expanded from interventions in the private and public health domains to encompass a productive policy-making sexual health discourse at the local, state, and federal levels that leads to legal protections and opportunities regardless of socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or ability to pay for care. Addressing sexual injustice requires the affirmation of sexual rights as basic human rights that are enjoyed by all. Thus, the committee endorses the 10 sexual rights formulated by the International Planned Parenthood Federation in 2008 (see Table 1-1).

TABLE 1-1 Sexual Rights

|

All persons are born free and equal in dignity and rights and must enjoy the equal protection of the law against discrimination based on their sexuality, sex, or gender. |

|

All persons are entitled to an environment that enables active, free and meaningful participation in and contribution to the civil, economic, social, cultural, and political aspects of human life at local, national, regional and international levels, through the development of which human rights and fundamental freedoms can be realized. |

|

All persons have the right to life and liberty and to be free of torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment in all cases, and particularly on account of sex, age, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, marital status, sexual history or behavior, real or imputed, and HIV/AIDS status, and shall have the right to exercise their sexuality free of violence or coercion. |

|

All persons have the right not to be subjected to arbitrary interference with their privacy, family, home, papers, or correspondence and the right to privacy, which is essential to the exercise of sexual autonomy. |

|

All persons have the right to be recognized before the law and to sexual freedom, which encompasses the opportunity for individuals to have control and decide freely on matters related to sexuality, to choose their sexual partners, to seek to experience their full sexual potential and pleasure, within a framework of nondiscrimination and with due regard to the rights of others and to the evolving capacity of children. |

|

All persons have the right to exercise freedom of thought, opinion, and expression regarding ideas on sexuality, sexual orientation, gender identity, and sexual rights, without arbitrary intrusions or limitations based on dominant cultural beliefs or political ideology, or discriminatory notions of public order, public morality, public health, or public security. |

|

All persons have a right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, which includes the underlying determinants of health and access to sexual health care for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of all sexual concerns, problems, and disorders. |

|

All persons, without discrimination, have the right to education and information generally and to comprehensive sexuality education and information necessary and useful to exercise full citizenship and equality in the private, public, and political domains. |

|

All persons have the right to choose whether or not to marry, whether or not to found and plan a family, when to have children and to decide the number and spacing of their children freely and responsibly, within an environment in which laws and policies recognize the diversity of family forms as including those not defined by descent or marriage. |

|

All persons have the right to effective, adequate, accessible, and appropriate educative, legislative, judicial, and other measures to ensure and demand that those who are duty bound to uphold sexual rights are fully accountable to them. This includes the ability to monitor the implementation of sexual rights and to access remedies for violations of sexual rights, including access to full redress through restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction, guarantee of nonrepetition, and any other means. |

SOURCE: Adapted from IPPF, 2008.

Sexual Health

As described in the committee guiding principles and framework (see below), sexual health is a critical frame when approaching STI prevention and control. This section provides a brief historical overview of sexual health in the United States and includes important considerations for moving forward. In the first decade of the 20th century, organized efforts to promote control of STIs were led by Prince Morrow, founder of the American Society for Sanitary and Moral Prophylaxis, a “coalition of … the settlement movement, charity groups, moral reformers, and the church” who emphasized moral duty to remain chaste and healthy (Brandt, 1985).

Over the remainder of the 20th century, sex education and efforts to control STIs were led by similar organizations, such as the American Social Hygiene Association (predecessor of the American Sexual Health Association). These organizations were joined by the U.S. Armed Forces and Public Health Service in leading provision of sexual education and guidance of efforts to prevent and manage STIs. These groups’ efforts tended to emphasize the deleterious consequences of STIs and link them to stigmatized terms (e.g., “promiscuity,” “infidelity”) and adverse health consequences (e.g., congenital infections, infertility). Such attitudes appear to have dominated STI prevention messaging throughout the 20th century as the role of the federal government and particularly CDC grew to preeminence in guiding U.S. STI policies.

Evolution of Sexual Health Paradigms

In parallel, the scientific study of human sexuality and function developed as an interdisciplinary specialty, sexology, encompassing the medical, psychological, and cultural aspects of sexual development and relationships throughout the life span. From the outset, sexual health experts focused their studies on healthy sexuality in the absence of disease and dysfunction. In 1975, the World Health Organization (WHO) first published a brief definition and discussion of sexual health (WHO, 1975). Progress in the field was modest, catalyzed by the so-called sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, but began to grow with recognition of the inextricable interaction of human sexuality and risk of HIV. In collaboration with the Pan American Health Organization and, soon thereafter, the larger WHO, a working group was convened and created an expanded definition of sexual health (see Box 1-3), which began to impact public health efforts in Europe and Australia (Coleman, 2011). In 2001, U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher issued his Call to Action, which provided the foundation for U.S. public health interest in sexual health (Satcher, 2001).

U.S. attempts to incorporate sexual health into HIV and, subsequently, STI control as part of efforts to address stigma, were further articulated in the late 2000s. For example, Swartzendruber and Zenilman (2010) discussed the need for a shift from a stigmatizing focus on STI morbidity toward a strategy focused on health rather than disease. In 2010, CDC held a consultation on sexual health; however, CDC did not formally adopt a sexual health approach at that time (Douglas, 2011; Douglas and Fenton, 2013). Satcher et al. (2015) suggested a hierarchical “pyramid” sexual health framework with five elements (starting from the top): counseling and education, clinical interventions, long-lasting protective interventions, changing the context to make individuals’ decisions healthy, and socioeconomic factors. This framework could enhance disease control

and prevention activities using four principles: emphasis on wellness, focus on positive and respectful relationships, acknowledgment of sexual health as an element of overall health, and an integrated approach to prevention. CDC embraced these efforts (Douglas and Fenton, 2013) and the CDC/Health Resources and Services Administration Advisory Committee on HIV, Viral Hepatitis, and STD Prevention and Treatment (CHAC) culminated in a definition of sexual health that built on the 2002 revision of the WHO definition (WHO, 2006) (see Box 1-3).

Importantly, the WHO definition includes “pleasure,” whereas the CHAC definition does not. Pleasure is sufficiently central to many perspectives on sexual health, however, as to support its inclusion in a sexual health definition. In its “Declaration on Sexual Pleasure,” the World Association for Sexual Health recognizes sexual pleasure as “the physical and/or psychological satisfaction and enjoyment derived from shared or solitary erotic experiences, including thoughts, fantasies, dreams, emotions, and feelings” (WAS, 2019). Furthermore, “Self-determination, consent, safety, privacy, confidence and the ability to communicate and negotiate sexual relations are key enabling factors for pleasure to contribute to sexual health and wellbeing.” Finally, “The experiences of human sexual pleasure are diverse and sexual rights ensure that pleasure is a positive experience for all concerned and not obtained by violating other people’s human rights and well-being” (Ford et al., 2019; WAS, 2019). The latter statement, however, also points to a potential negative corollary: traumatic experiences, especially in adolescence, may be linked to adverse STI outcomes (London et al., 2017). Thus, trauma-responsive approaches need to be considered that address interpersonal and structural violence as part of a public health approach independent of technological advances in diagnostics, vaccines, and pharmacotherapies.

Over the past decade, people working in the field have increasingly incorporated the sexual health discourse into discussion of STI control efforts. Information provided by CDC, although beginning to be less negative, continues to first emphasize the negative consequences of STIs (infertility, congenital infections, STI-related cancers, amplified HIV transmission and acquisition) before celebrating the potential to identify and address preventable causes of these sequelae. Furthermore, it seems that the “sexual health perspective” has not yet been widely accepted by providers working in settings other than those devoted to reproductive health and STI management. While still limited in comparison to risk-focused studies, the literature on sexual health–positive interventions is growing. In a summary of data from 58 studies (1996–2011), mostly from individual and group-based interventions addressing sexual behaviors and attitudes/norms, Hogben et al. (2015) found that all but one study reported positive outcomes in at least one domain, and half found null

effects in at least one domain. Positive effects were seen particularly in studies focused on sexual minorities, marginalized populations, and parental communications (Hogben et al., 2015). Importantly, multi-dimensional sexual health models have been empirically operationalized to demonstrate that higher levels of sexual health awareness are associated with preventive measures (i.e., sexual health is an important construct for promoting positive sexual development), including abstinence, higher proportion of condom-protected events, and absence of STIs (Hensel and Fortenberry, 2013). In addition, while research into trauma-responsive interventions for STI prevention is still in its infancy, studies linking screening for sexual trauma and uptake of HIV testing (Cuca et al., 2019; Reddy et al., 2019) support their potential.

In promoting a sexual health discourse to inform the STI prevention agenda, it is important to ensure that the sexual health of all people is addressed, especially marginalized populations that are often disproportionally affected by STIs, including LGBTQ+ populations; Black people; Latino/a people; AI/AN people; sex workers; immigrants; incarcerated populations; and people affected by mental health and substance use

disorders. Thus, attention needs to be given to potential barriers that these populations encounter at points of contact throughout the health care system. In this context, service provision needs to be informed by shared decision making among providers and patients, which requires that the health care system sheds its image as a benevolent patriarchy that is dominated by traditional privileged groups. The recent restructuring of the STI clinic system in New York City to address delivery of care, including renaming STD clinics into “Sexual Health Clinics,” carried out by extensive community involvement, is an encouraging example (NYC Health, 2017).

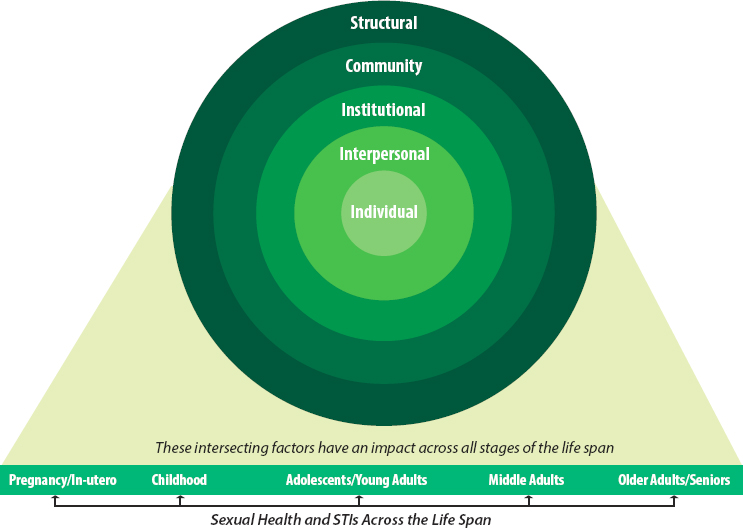

Report Conceptual Framework: A Modified Social Ecological Framework of Sexual Health and STI Prevention, Control, and Treatment

The conceptual framework that provides a unifying approach for the committee’s report on the U.S. STI epidemic describes multiple and interrelated influences on STI risk, prevention, health care access, delivery, and treatment, as depicted in Figure 1-3 and further detailed with selected examples in Box 1-4. Specifically, this framework adapts the Ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and the succeeding Social Ecological model (Baral et al., 2013; Brawner, 2014; McLeroy et al., 1988; Sallis and Owen, 2015; Sallis et al., 2008), which integrates tenets of social and structural determinants of health and health inequities (CDC, 2010; Hogben and Leichliter, 2008; NASEM, 2017, 2019; WHO, 2010). The committee extended the Social Ecological model to include concepts from the Intersectionality (Bowleg, 2012; Collins, 2015; Collins and Bilge, 2020; López and Gadsden, 2016) and Sexual Health (Satcher et al., 2015; WHO, 2006) frameworks. Thus, the core elements of this report’s conceptual framework emphasize the importance of the following.

Variation in STI Pathogens

Acquisition and transmission of STIs vary by pathogen type (e.g., viral, bacterial, protozoan) and species-to-species variation, that are determined by the confluence of many interconnected factors, including host characteristics, the epidemiology of infection in the community, individual behavior, sexual partner selection, and other sexual network influences within the broader social (institutional and community) and societal (structural) domains (CDC, 2010; Hogben and Leichliter, 2008).

Interrelated Social Ecological Factors

Individual agency in sexual health decision making and behavior is synergistically influenced by contextual factors that occur in interpersonal relationships (e.g., family, peers, sexual partners, health providers) and within the broader social and societal domains (Baral et al., 2013; McLeroy et al., 1988).

Social and Structural Determinants of Health and Health Inequities

Societal conditions (e.g., health and social policies, social norms, governance practices) shape the social context and determinants (e.g., socioeconomic resources, inequitable health care delivery) that facilitate STI transmission and prevention beyond individual behavior (Brawner, 2014).

Intersectionality

Social identities, such as race and ethnicity, gender and gender identity, sexual orientation, and disability, are multi-dimensional, interdependent, and mutually intrinsic experiences operating at the individual level that intersect with social inequalities (e.g., poverty, racism, heterosexism, sexism, transphobia) operating at the societal level that provide the context for vast STI disparities in resource-limited, marginalized, and minoritized communities (Bowleg, 2012; Brawner, 2014; Collins, 2015).

Sexual Health

Comprehensive STI surveillance, disease control, prevention, and treatment require a holistic view that recognizes that sexual health is inextricably linked to overall health and wellness. Because sexuality and sexual expression occur across the life span, healthy, safe, and respectful relationships are important and sexual rights for all need be protected (Satcher, 2001; WHO, 2006) (see Table 1-1).

In sum, effective STI prevention, control, and treatment needs to move beyond individual-level behavior and behavior-change models toward a comprehensive framework that understands and addresses the interconnected and mutually reinforcing social and structural determinants of health and health inequities. Successfully applying this framework necessitates multi-pronged and multi-level evidence-based sustained approaches that integrate individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and structural facilitators to overcome barriers to sexual health and STI prevention, control, and treatment in the United States. Moreover, successful application of this framework requires a shift in current siloed funding mechanisms to an integrated and sustained funding approach

NOTE: This figure illustrates the multiple interrelated influences on STI risk, prevention, health care access, delivery, and treatment across the life span.

SOURCE: Adapted from NASEM, 2019.

that not only addresses STIs as discrete health outcomes but also addresses the social and structural determinants that influence STI risk, prevention, health care access, delivery, and treatment (see Chapter 2 for a detailed description of the core elements in the conceptual framework).

Moving from a Narrow View of STIs to a Broader Sexual Health Approach

As highlighted in this chapter and discussed throughout this report, STI prevalence is determined by interrelated individual, social, community, and structural factors operating simultaneously in a person’s environment (e.g., partners, family, community, society) that have led to extensive disparities across groups in terms of socioeconomic status, ethnicity and race, sexual orientation, and gender identity. These disparities limit access to and the availability of care and are perpetuated by stigma that effectively blames marginalized individuals and communities while ignoring overarching determinants of health. These disparities cannot be

overcome by individual behavior change alone, but require an integrated approach that acknowledges the importance of sexual health, structural and social determinants of health, and intersectionality as key factors for addressing STI inequities across the life span. The committee was guided by such an approach in its ethical considerations and recognizes that the ongoing STI epidemic in the United States is a societal problem that demands a societal solution.

Conclusion 1-1: The committee concludes that the persistence and growth of STIs pose a serious threat to the health of those residing in the United States.

Conclusion 1-2: The nation’s response to STIs since the beginning of the 20th century has mostly focused on individual risk factors and individual behavior change and has neglected the social and structural determinants of sexual behavior. This approach has tended to fuel stigma and shame, which have hindered the successful prevention and control of STIs.

Conclusion 1-3: STI prevention and control efforts to date have centered on treatment of infections and prevention. To successfully address STIs, a holistic approach that focuses on sexual health in the context of broader health and well-being is needed. To carry out this change, significant efforts will be needed to eradicate stigma and to promote sexual health awareness.

The committee acknowledges that the United States is a diverse country of almost 330 million people, and how one operationalizes a sexual health paradigm will inevitably vary. The sexual health component of STI prevention and care, however, has not been adequately addressed, due in part to STI stigma and long-standing cultural norms that hinder open dialogue about sexuality. This paradigm shift is needed given the history of how marginalization has contributed to the proliferation of STIs. There is a cost that society is paying for this marginalization, and significantly shifting the cultural environment to be supportive of this framework will take dedication and investment, as well as strategic actions outlined in this report (for more on this topic, see Chapter 12). The committee does not view this as a political issue or one that needs to be in conflict with religious beliefs or ethical standards. For example, promoting sexual health in a manner that facilitates STI prevention, diagnosis, and treatment does not constrain faith communities from teaching about sexual responsibility and sexual health in a way that is consistent with their own faith traditions and ethical frameworks. The committee holds an inclusive vision of respect and appreciation for diversity in religious belief, culture, gender, and sexual orientation.

CHANGES IN THE STI LANDSCAPE IN THE PAST 20 YEARS

The committee is completing its work as the nation and the world continue to grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated disruptions in economic activity. A growing challenge of misinformation is exacerbating declining trust in public institutions in general and public health and public health agencies in particular at a time when the urgency of following public health guidance (even if it changes and evolves with new knowledge) has life-or-death implications. The burden of responding to the COVID-19 crisis has been felt heavily by local, state, and federal STI programs. Under-resourced STI programs have to compete for

funding and staff with this new public health threat as states are experiencing declining revenues at the same time that STI program staff have been diverted as they were to the HIV response in prior decades; they are professionals with the appropriate training and expertise to lead the COVID-19 response, so this diversion was necessary and appropriate. Nonetheless, it has meant less attention to STIs and fewer critical services being delivered. A May 2020 survey of health department STI programs found that 83 percent were deferring STI services or field visits, 62 percent cannot maintain their HIV and syphilis caseloads, and 66 percent of clinics reported a decrease in sexual health screening and testing (NCSD, 2020). Furthermore, the pandemic has led to a shortage of STI diagnostic

test kits and laboratory supplies (Bolan, 2020). For example, it is estimated that these STI health disruptions may lead to hundreds of new HIV cases and thousands of STI cases in Atlanta alone (Jenness et al., 2020). (See Chapter 12 for more information on the STI–COVID interface; examples and lessons learned from COVID are used throughout the report, as appropriate.)

This report also comes more than two decades after the release of the foundational report The Hidden Epidemic: Confronting Sexually Transmitted Disease (IOM, 1997). The committee believes that that report remains relevant today and broadly endorses its recommendations. In particular, the committee was guided by the report’s vision:

An effective system of services and information that supports individuals, families, and communities in preventing [STIs], including HIV infection, and ensures comprehensive, high-quality [STI-related] health services for all persons.

One of the committee’s goals for this report is to build on and extend the work of The Hidden Epidemic by reflecting the changes in context of STIs since 1997. At the time, the nation appeared on the verge of eliminating syphilis, and chlamydia and gonorrhea rates also were declining. The next year, CDC announced a detailed plan to eliminate sustained syphilis transmission (Valentine and Bolan, 2018). CDC noted that annual cases had declined by 86 percent from the last outbreak in 1990 and half the reported cases arose in 28 counties, out of more than 3,000 U.S. counties (CDC, 2007). Unfortunately, Congress cut funding for STI prevention and control, and the plan’s objectives were not realized. In 2000, there were 5,979 cases of primary and secondary syphilis and 589 cases of congenital syphilis (CDC, 2001). By 2018, the reported cases had risen to 35,063 (an almost 6-fold increase), and they are growing rapidly. Congenital syphilis cases had risen to 1,306 (more than doubling since 2000). Reported cases of chlamydia and gonorrhea have followed a similar pattern of explosive growth that continues today (CDC, 2019c).

Since The Hidden Epidemic, family structure has changed considerably (Brown, 2020; Pew Research Center, 2019). For example, among heterosexual people, increasing divorce rates, delayed marriage, and an increase in those choosing to not marry, coupled with a longer life span, have resulted in more single heterosexual adults (Brown, 2020; Karney and Bradbury, 2020). More U.S. adults are single than ever before. In the 1960s, 72 percent of U.S. adults were married; in 2017, that declined to 54.8 percent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). Changing attitudes about extramarital sex also may be influencing adults’ sexual behavior. Those who agree that extramarital sex is not wrong at all have gone from 29 percent in the

1970s to 58 percent in the 2012 (Twenge et al., 2015); however, a 2017 study found that the number of Americans who report having extramarital sex has remained relatively constant over the past 30 years at about 16 percent (Wolfinger, 2017). The challenge of preventing and controlling STIs is exacerbated by larger syndemics that include growing epidemics of methamphetamine and opioid addiction (NASEM, 2020), which can also indirectly lead to more STIs by practice of high-risk behavior.

A key factor affecting the challenges and opportunities for addressing STIs is Internet usage. In 1997, fewer than one in four U.S. individuals were estimated to use the Internet, whereas by 2020, this has risen to more than 9 in 10. U.S. adults spend more than 11 hours per day interacting with media (Nielsen, 2018). The iPhone was not introduced until 2007, and the widespread adoption of this and other smart and mobile devices has led to significant transformation in how people communicate and interact through millions of readily accessible apps. While apps facilitate activities from shopping to improving workplace productivity, the introduction of apps that allow individuals to meet others for socialization and sex has been revolutionary. The massive amount of “big data” from apps and digital devices has facilitated development of artificial intelligence–based machines that can influence sexual-health-related attitudes and behaviors. While it is easy to denounce such technologies for potentially facilitating greater STI transmission, a balanced assessment of them may find both positive and negative effects. Technology and media also may serve as a useful tool for sexual health behavior change. Millions of people use these technologies and they continue to develop, so policies and interventions to improve sexual health and wellness and to prevent and control STIs also need to consider this reality. (See Chapter 6 for more on the role of technology and media.)

Not all changes since 1997 have been negative. The broad adoption of the Internet has allowed for wide-scale data collection that both produces new risks to privacy and personal safety and also facilitates greater analysis of information that can dramatically improve our effectiveness at identifying and responding to disease outbreaks. The increasing use of machine learning and artificial intelligence means that this revolution is ongoing, so they will continue to pose both new threats and new opportunities for preventing and controlling STIs. Clinical advances also have continued over the past decade that have delivered more diagnostic tools, such as telehealth, app-based interventions, home-based testing, and rapid and point-of-care tests, and other innovations, such as the HPV vaccine and hepatitis C curative treatment. Such advances will be significant in fostering greater STI control.

It is also important to reflect on and learn from the very important progress in responding to the HIV epidemic. The Hidden Epidemic was

released 1 year after highly active antiretroviral therapy was introduced in the United States, and the nation has become accustomed to the stunning declines in deaths among people living with HIV. Moreover, scientific innovation has continued to deliver more and better therapeutics, and researchers appear to be on the cusp of transformative change, with envisioned numerous long-acting agents for HIV treatment and prevention that will not require daily dosing. Effective pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV, which has proven to be safe and highly effective, has been available for less than a decade. More HIV PrEP options are anticipated, including lower cost generic drugs that may increase access. Furthermore, starting in 2020, the United States Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation for HIV PrEP began to require private health plans and Medicaid expansion programs to provide PrEP when clinically indicated without cost sharing, a move that is expected to greatly expand access.

Despite these promising developments, the growing STI crisis starkly outlines what has not changed since 1997. The United States continues to rely on long-standing and outdated medications for bacterial STIs. There are too few vaccines and both a weak pipeline for new therapeutics and growing concerns over drug resistance to existing therapies, especially for gonorrhea. STI prevention, care, and research remain dramatically underfunded at the federal level in relation to their public health burden, and state and local funding is nonexistent or miniscule in most U.S. jurisdictions. Unfortunately, this situation is but one component of the defunding and underfunding of public health. As the nation and the world face emerging pandemics, the nation will pay an increasing price for neglecting to invest in public health and neglecting STIs or placing them in funding competition with other seemingly more urgent infectious diseases.

The committee considered whether the response to STIs should focus on all individuals in the United States, as anyone can be at risk, or on specific groups or communities. A disheartening reflection of what has not changed in the past 20 years is how much the impact of STIs is not equally distributed, but is rather highly concentrated, in terms of both place, with the southern region bearing the heaviest burden, and people, with racial and ethnic minorities, transgender people, and gay and bisexual men and other sexual and gender minorities being highly disproportionately impacted. This disproportionality cannot be neatly attributed to individual behavior alone but is embedded in historical experience and individuals’ social, cultural, and physical environments.

Young people also account for a very large share of STIs; people aged 15–24 comprise half of all annual diagnoses among sexually active individuals even though they make up only one-quarter of the population. Moreover, whereas men may be at greater risk of acquiring certain STIs than women, the consequences of untreated STIs are often more severe

for women in terms of pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, and in transmitting infection to their offspring. Men are essential in transmitting STIs to women, but historically have been underserved in STI prevention and care programs.

The national response to the STI crisis needs to recognize that the nation’s collective efforts will be most successful if funding and programs prioritize health equity and address broader factors that are associated with an increased STI risk (such as racism, discrimination, unemployment, income insecurity, poverty, and unstable housing) while also increasing access to comprehensive STI health services. Nonetheless, the committee believes that even as resource allocations are aligned with the groups with the greatest needs and that bear the greatest consequences of STIs, a successful national effort needs to engage individuals broadly.

Recent STI-Related Reports

Recently, several significant STI-focused reports and documents have been published. The National Coalition of STD Directors engaged the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) to undertake a two-part study of the STD epidemic in the United States (NAPA, 2018, 2019). The Treatment Action Group (TAG) analyzed ongoing research in the pipeline for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis, and concluded that the current toolbox for addressing them is inadequate (TAG, 2019). Finally, the first-ever federal STI National Strategic Plan (STI-NSP): 2021–2025 was developed and released for public comment in 2020, and the final plan was released in December 2020 (HHS, 2020). It builds on the NAPA and TAG reports, as there are many synergies between them. A description of these reports and the STI-NSP is available in Chapter 12; in that chapter and throughout this report, the committee identifies alignment and variations in approach. Given the synergies between the STI-NSP and this report, the implementation of the STI-NSP offers an important opportunity to execute many of the recommendations provided in this report.

STUDY PROCESS AND REPORT OVERVIEW

The committee gathered information through a variety of means. It held seven information-gathering meetings or webinars between August 2019 and September 2020 (the agendas are available in Appendix D) on a range of topics, including trends in sexual behavior and reproductive health; opportunities and barriers at the state and local levels; structural, behavioral, biomedical, and health system interventions and technological tools; economic burden; and international perspectives. The committee held two webinars to hear individual and community perspectives

on how to better respond to STIs—the comments and discussions were very informative and added depth to the issues discussed in this report. Quotes from these meetings are included throughout the report to illustrate the complex and intersecting barriers and opportunities related to sexual health and STI prevention and control. The committee also held deliberative meetings and received public submissions of materials for its consideration throughout the course of the study.1 The committee’s online activity page also provided information to the public about its work and facilitated communication with the public.2

Report Terminology

Over time, terminology for sexual health (as discussed above) and STIs has significantly evolved. Stigmatizing language used in the naming, terms, and classification of STIs has contributed to blame and alienation of the very persons who need to be engaged and assisted. Therefore, throughout this report, the committee strived to use language that is respectful, accurate, and maximally inclusive. This relies on attempting to reflect preferences for how individuals and groups wish to be addressed, but there is not always consensus on preferred terms, and these preferences may evolve over time. As a general matter, this report uses Black people when referencing African Americans and others that are part of the African diaspora, as the term is often understood to be broader and include persons whose cultural history is not grounded in the United States. Similarly, the committee has chosen “Latino/Latina” for consistency to refer to persons with cultural connections to Latin America, recognizing that some people may prefer “Hispanic,” “Latinx,” or another term.

Societal understanding of gender identity is rapidly evolving. This report uses “transgender/non-binary” as an inclusive term that is intended to encompass non-binary, gender fluid, and other persons. Gender-related terms are also used, but when applicable, broader terms, such as “pregnant people” in place of “pregnant women,” are intended to acknowledge the diversity of gender identities and point to ways that our common language can be updated to accord greater respect to all people. “Gender expansive” is used to describe people that expand notions of gender expression and identity beyond what is perceived as the expected norms for their society or context. “LGBTQ+” refers to individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning. Sometimes the terms, however, are determined by the terms or definitions in data systems or a specific research study referred to or summarized. The

___________________

1 Public access materials can be requested from PARO@nas.edu.

2 See nationalacademies.org/PreventSTIs (accessed July 14, 2020).

committee also recognizes the current discourse on the use of inclusive and destigmatizing language when discussing sexual behaviors, such as the preference for “condomless” rather than “unprotected” sex (Editors, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 2020). Finally, the committee uses “sexually transmitted infections” instead of “sexually transmitted diseases” unless referring to the actual diseases rather than to the infections. (See Box 1-5 for a comparison of these terms.)

Methodology

The committee undertook a comprehensive review of the peer-reviewed and gray literature, including governmental and academic databases and websites.3 Studies that evaluate the effectiveness and applicability of interventions are important for assessing which interventions are most effective and suitable for a general or more specific population. Many interventions, however, have not been adequately evaluated for their effectiveness. In addition, studies vary in their design and setting, quality of execution, interactions with other interventions, and consideration of economic consequences (NASEM, 2019). Therefore, in large part, the committee relied on existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and comprehensive reviews with strong methodologies. Certain populations are frequently systematically excluded from or not the primary focus of intervention studies or other STI research, including persons who are transgender, AI/AN people, and persons with disabilities. In those cases, the committee needed to rely on smaller or fewer studies. The committee notes throughout the report where this is the case and where more

___________________

3 The date range for the search was October 2009 to May 2020.

research is needed. Research on HIV was included throughout the report where lessons from that body of research could be applied or when research on STIs was lacking. Regarding STI data, the committee used the most recent data available—as of the writing of this report, the most comprehensive was the 2019 CDC surveillance report containing data from 2018 as the 2019 CDC STI surveillance report was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Report Overview

Throughout this report, the committee provides conclusions and recommendations for action, guided by the conceptual framework introduced earlier in this chapter. To do so, the committee has organized its recommendations under four key themes:

- Adopt a Sexual Health Paradigm

- Broaden Ownership and Accountability for Responding to STIs

- Bolster Existing Systems and Programs for Responding to STIs

- Embrace Innovation and Policy Change to Improve Sexual Health

These themes are explored in detail in the following chapters. Chapters 1–5 provide background and address the first two components of the committee’s charge, and Chapters 6–12 address the third component of the charge—advice on future public health programs, policies, and research in STI prevention and control (some of these chapters provide conclusions, and others provide conclusions and recommendations for action). Chapter 2 provides an overview of the status of STIs in the United States and the contextual factors and drivers (such as the social and structural determinants of health) that need to be considered when working to prevent and control STIs. Chapter 3 further explores these contextual factors that drive STIs for priority populations. Chapter 4 discusses the policy, financing, and economic factors that shape the STI landscape today, including the economic burden. Chapter 5 highlights the important interface between HIV and STIs and why they cannot be viewed in silos. Chapter 6 explores the potential risks and benefits of technology and media and how they can be used to improve the nation’s response. Chapters 7, 8, and 9 examine biomedical, psychosocial and behavioral, and structural interventions, respectively, and the need for these different types of interventions to work together as part of multi-level interventions to address STIs at every level. Chapter 10 examines the health care system and the considerable gaps in addressing STIs. The report culminates with Chapter 11 (which examines the current STI workforce and delineates how to prepare and expand it to achieve the recommendations laid out

in this report) and Chapter 12 (which offers a plan for actions to make progress toward reducing STIs).

The committee provides a range of recommendations in Chapters 7–12 related to health care practice and access, policy, and research, including some recommendations that will take time and sustained commitment and funding to achieve. CDC’s STI funding over the past two decades has remained flat (with a 40 percent reduction in inflation-adjusted dollars). Although the committee’s charge did not specifically ask it to make recommendations related to funding levels and other necessary resource allocations for STIs, the committee notes that some of the recommendations will require new or substantial realignment of resources to implement, and the authority and political support to modify existing systems at the local, state, and federal levels. Stronger leadership and coordination of national STI prevention and control efforts are also needed to improve STI prevention and control. Furthermore, because the committee’s primary focus was on providing clear policy guidance and a framework for action, it does not uniformly offer specific implementation steps or metrics for each recommendation. The committee acknowledges that to provide more specific implementation steps would have required a more in-depth understanding of STI resources, policies, and other circumstances at the state, local, and federal levels and an understanding of the communities and stakeholders who would have critical roles in operationalizing these recommendations. The committee understands that resources, policies, and stakeholders vary across the country and that flexibility in implementation of recommendations will need to adjust to those circumstances.

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

Although much has changed since The Hidden Epidemic in 1997, many conditions in the United States have not changed markedly. Despite the dedicated commitment from many individuals and agencies committed to reducing the burden of STIs and elevating sexual health, STI research, policy, and services continue to suffer from neglect. Relatively flat federal investments and declining state and local investments in the face of all-time high numbers of reported cases of STIs underscores the failure of the crisis to capture the attention of the public.

The committee’s exploration of the complexities of the challenge, however, has instilled in its members a firm belief that it is possible to create a different and better future where fewer adults are infected, fewer babies are born with STIs, people, starting in adolescence but across the life span, are taught the language and skills to conceptualize and enact their own vision for what it means to be sexually healthy, and the nation records progressive reductions in STIs, including the current epidemics of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis.

The required changes will take concerted commitment and action, but it is possible to reduce the impact of STIs on society and take bold actions recommended in this report to control STIs in the immediate future. In turn, this can create a platform where the nation can return to the ultimate task of planning to eliminate these serious health threats.

REFERENCES

Baral, S., C. H. Logie, A. Grosso, A. L. Wirtz, and C. Beyrer. 2013. Modified Social Ecological model: A tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health 13:482.

Bolan, G. 2019. Division of STD prevention. Presentation to the Committee on Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Infections in the United States, Meeting 1 (August 26). https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/08-26-2019/docs/D3423E23A3A4A9B4447C205483C8F840EF1481A1EEE2 (accessed February 17, 2021).

Bolan, G. 2020. Dear colleague letter: Shortage of STI diagnotic test kits and laboratory supplies. https://www.cdc.gov/std/general/DCL-Diagnostic-Test-Shortage.pdf (accessed October 25, 2020).

Bowleg, L. 2012. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health 102(7):1267-1273.

Brandt, A. 1985. No magic bullet. A social history of venereal disease in the United States since 1880. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brawner, B. M. 2014. A multilevel understanding of HIV/AIDS disease burden among African American women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing 43(5):E633-E650.

Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brown, A. 2020. Nearly half of U.S. adults say dating has gotten harder for most people in the last 10 years. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Brown, A. F., G. X. Ma, J. Miranda, E. Eng, D. Castille, T. Brockie, P. Jones, C. O. Airhihenbuwa, T. Farhat, L. Zhu, and C. Trinh-Shevrin. 2019. Structural interventions to reduce and eliminate health disparities. American Journal of Public Health 109(Suppl 1):S72-S78.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2001. Syphilis elimination key facts. https://www.cdc.gov/stopsyphilis/media/SyphElimKeyFacts.htm (accessed February 10, 2021).

CDC. 2007. The national plan to eliminate syphilis from the United States—executive summary. https://www.cdc.gov/stopsyphilis/exec.htm (accessed February 10, 2021).

CDC. 2010. Establishing a holistic framework to reduce inequities in HIV, viral hepatitis, STDs, and tuberculosis in the United States. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services.

CDC. 2016. CDC fact sheet: Today’s HIV/AIDS epidemic. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/todaysepidemic-508.pdf (accessed December 11, 2020).

CDC. 2019a. Congenital syphilis—CDC fact sheet. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfactcongenital-syphilis.htm (accessed February 19, 2021).

CDC. 2019b. National notifiable diseases surveillance system, 2018 annual tables of infectious disease data. CDC Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance. https://wonder.cdc.gov/nndss/static/2018/annual/2018-table1.html (accessed January 28, 2020).

CDC. 2019c. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services.

CDC. 2019d. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/STDSurveillance2018-full-report.pdf (accessed October 25, 2020).

CDC. 2020. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States 2014-2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-25-1.pdf (accessed December 11, 2020).

CDC. 2021. Sexually transmitted infections prevalence, incidence, and cost estimates in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/prevalence-2020-at-a-glance.htm (accessed January 28, 2021).

CDC. n.d. CDC Atlas Plus: STD data. https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/nchhstpatlas/charts.html (accessed January 29, 2021).

Chesson, H. W., I. H. Spicknall, A. Bingham, M. Brisson, S. T. Eppink, P. G. Farnham, K. M. Kreisel, S. Kumar, J.-F. Laprise, T. A. Peterman, H. Roberts, and T. L. Gift. 2021. The estimated direct lifetime medical costs of sexually transmitted infections acquired in the United States in 2018. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001380.

Coleman, E. 2011. What is sexual health? Articulating a sexual health approach to HIV prevention for men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior 15:S18-S24.

Collins, P. H. 2015. Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology 41(1):1-20.

Collins, P. H., and S. Bilge. 2020. Intersectionality. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Cuca, Y. P., M. Shumway, E. L. Machtinger, K. Davis, N. Khanna, J. Cocohoba, and C. Dawson-Rose. 2019. The association of trauma with the physical, behavioral, and social health of women living with HIV: Pathways to guide trauma-informed health care interventions. Women’s Health Issues 29(5):376-384.

Douglas, J. M. 2011. Advancing a public health approach to improve sexual health in the United States: A framework for national efforts. https://www.cdc.gov/sexualhealth/docs/douglasnhpchivpx081611last.pdf (accessed January 28, 2021).

Douglas, J. M., Jr., and K. A. Fenton. 2013. Understanding sexual health and its role in more effective prevention programs. Public Health Reports 128:1-4.

Editors, Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2020. Making our words matter: Reflections on terminology to describe behavioral risk factors in STD and HIV prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 47(1):4.

Ford, J. V., E. Corona Vargas, I. Finotelli, Jr, J. D. Fortenberry, E. Kismödi, A. Philpott, E. Rubio-Aurioles, and E. Coleman. 2019. Why pleasure matters: Its global relevance for sexual health, sexual rights and wellbeing. International Journal of Sexual Health 31(3):217-230.

Hensel, D. J., and J. D. Fortenberry. 2013. A multidimensional model of sexual health and sexual and prevention behavior among adolescent women. Journal of Adolescent Health 52(2):219-227.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2020. Sexually Transmitted Infections National Strategic Plan for the United States: 2021-2025. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

HIV.gov. 2020. Fast facts. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics (accessed October 23, 2020).

Hogben, M., and J. S. Leichliter. 2008. Social determinants and sexually transmitted disease disparities. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 35(12 Suppl):S13-S18.

Hogben, M., J. Ford, J. S. Becasen, and K. F. Brown. 2015. A systematic review of sexual health interventions for adults: Narrative evidence. Journal of Sex Research 52(4):444-469.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1997. The hidden epidemic: Confronting sexually transmitted diseases. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IPPF (International Planned Parenthood Federation). 2008. Sexual rights: An IPPF declaration. London, UK: International Planned Parenthood Federation.

Jenness, S. M., A. Le Guillou, C. Chandra, L. M. Mann, T. Sanchez, D. Westreich, and J. L. Marcus. 2020. Projected HIV and bacterial STI incidence following COVID-related sexual distancing and clinical service interruption. MedRXiv.

Karney, B. R., and T. N. Bradbury. 2020. Research on marital satisfaction and stability in the 2010s: Challenging conventional wisdom. Journal of Marriage and the Family 82(1):100-116.

London, S., K. Quinn, J. D. Scheidell, B. C. Frueh, and M. R. Khan. 2017. Adverse experiences in childhood and sexually transmitted infection risk from adolescence into adulthood. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 44(9):524-532.

López, N., and V. L. Gadsden. 2016. Health inequities, social determinants, and intersectionality. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC.

McLeroy, K. R., D. Bibeau, A. Steckler, and K. Glanz. 1988. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly 15(4):351-377.

NAPA (National Academy of Public Administration). 2018. The impact of sexually transmitted diseases on the United States: Still hidden, getting worse, can be controlled. Washington, DC: National Academy of Public Administration.

NAPA. 2019. The STD epidemic in America: The frontline struggle. Washington, DC: National Academy of Public Administration.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. Communities in action: Pathways to health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2019. Vibrant and healthy kids: Aligning science, practice, and policy to advance health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2020. Opportunities to improve opioid use disorder and infectious disease services: Integrating responses to a dual epidemic. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NCSD (National Coalition of STD Directors). 2020. COVID-19 & the state of the STD field. https://www.ncsddc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/STD-Field.Survey-Report.Final_.5.13.20.pdf (accessed October 25, 2020).

Nielsen. 2018. Time flies: U.S. Adults now spend nearly half a day interacting with media. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2018/time-flies-us-adults-now-spend-nearly-half-a-day-interacting-with-media (accessed July 7, 2020).

NYC Health. 2017. Health department announces historic expansion of HIV and STI services at sexual health clinics. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/about/press/pr2017/pr003-17.page (accessed April 3, 2020).

Parran, T. 1937. Shadow on the land: Syphilis. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock.

Pew Research Center. 2019. Marriage and cohabitation in the U.S. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/11/06/marriage-and-cohabitation-in-the-u-s (accessed February 19, 2021).

Reddy, S. M., G. A. Portnoy, H. Bathulapalli, J. Womack, S. G. Haskell, K. Mattocks, C. A. Brandt, and J. L. Goulet. 2019. Screening for military sexual trauma is associated with improved HIV screening in women veterans. Medical Care 57(7):536-543.

Sallis, J. F., and N. Owen. 2015. Ecological models of health behavior. In Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice, 5th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass/Wiley. Pp. 43-64.

Sallis, J. F., N. Owen, and E. Fisher. 2008. Ecological models of health behavior. In Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass/Wiley. Pp. 465-482.

Satcher, D. 2001. The surgeon general’s call to action to promote sexual health and responsible sexual behavior. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44216 (accessed February 10, 2021).

Satcher, D., E. W. Hook, 3rd, and E. Coleman. 2015. Sexual health in america: Improving patient care and public health. JAMA 314(8):765-766.

Singh, S., A. Mitsch, and B. Wu. 2017. HIV care outcomes among men who have sex with men with diagnosed HIV infection—United States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 66(37):969-974.

Swartzendruber, A., and J. M. Zenilman. 2010. A national strategy to improve sexual health. JAMA 304(9):1005-1006.

TAG (Treatment Action Group). 2019. Gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis pipline report. https://www.ncsddc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/TAG_Pipeline_STI_2019_draft.pdf (accessed October 25, 2020).

Twenge, J. M., R. A. Sherman, and B. E. Wells. 2015. Changes in American adults’ sexual behavior and attitudes, 1972-2012. Archives of Sexual Behavior 44(8):2273-2285.

Unemo, M., C. S. Bradshaw, J. S. Hocking, H. J. C. de Vries, S. C. Francis, D. Mabey, J. M. Marrazzo, G. J. B. Sonder, J. R. Schwebke, E. Hoornenborg, R. W. Peeling, S. S. Philip, N. Low, and C. K. Fairley. 2017. Sexually transmitted infections: Challenges ahead. Lancet Infectious Diseases 17(8):e235-e279.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2017. Unmarried and single Americans week: Sept. 17-23, 2017. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/cb17ff16.pdf (accessed February 10, 2021).

Valentine, J. A., and G. A. Bolan. 2018. Syphilis elimination: Lessons learned again. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 45(9S Suppl 1):S80-S85.

WAS (World Association for Sexual Health). 2019. Declaration on sexual pleasure. https://worldsexualhealth.net/declaration-on-sexual-pleasure (accessed February 10, 2021).

WHO (World Health Organization). 1975. Education and treatment in human sexuality: The training of health professionals, report of a WHO meeting (held in Geneva from 6 to 12 February 1974). Geneva, Switerzland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2006. Defining sexual health. Report of a technical consultation on sexual health, 28-31 January 2002, Geneva. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2010. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Wolfinger, N. H. 2017. America’s generation gap in extramarital sex. Charlottesville, VA: Institute for Family Studies.

This page intentionally left blank.