INTRODUCTION

Much has changed in the technology and media landscape in the past two decades that has had an impact on sexually transmitted infection (STI) acquisition, prevention, screening, and treatment. Taking into account these recent changes, this chapter provides a high-level overview of the following:

- Various technological innovations and their trends, including social media, virtual reality (VR)/augmented reality (AR), artificial intelligence (AI), electronic health records (EHRs), and a historical background on traditional media and television (see Box 6-1 for definitions of the technologies and relevant technological terms included in this chapter);

- The risks and benefits of these innovations (if applicable);

- Considerations for implementation and ethical issues, including the financial costs associated with implementation; and

- The role that the COVID-19 pandemic is playing on potential innovations relevant for sexual health.

Critical Observations to Conceptualize the Role of Technology in the STI Response

The broad key takeaways from this chapter are the following:

- A large and growing number of technological innovations are affecting sexual health and STI risk.

- Each innovation is only a tool that can (if designed properly) be used to reach and engage masses quickly; it is not inherently “risky” or “health promoting” by itself, as this depends on the use.

- Some of these innovations are ready for immediate implementation; others require more research.

- The technological innovations in this chapter have typically been led by industry (e.g., media and technology companies). The tools have become highly effective in improving identification, targeting, and behavior change of individuals and groups. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and public health departments would benefit greatly from working directly with industry to learn about these tools, their risks and benefits, and how to incorporate them into STI policy and practice. See Chapter 12 for more information on the effects of COVID-19 on STIs and sexual health.

- Research on this topic has often been designed for and/or in collaboration with health departments, in order to address potential barriers and improve likelihood of implementation.

The chapter concludes with a recommendation to CDC regarding how to leverage these technological innovations to improve STI prevention and control efforts.

Due to the large and growing number of and constantly changing trends in innovations, this chapter does not provide an exhaustive review of all possible innovations but seeks to offer a number of diverse key examples and their associated risks and benefits. Additionally, eHealth and mHealth are both defined and referred to in this chapter, but the focus is not specifically on prevention through the use of technology overall but the associations between specific technologies and their risks and benefits related to STIs. More information specific to interventions, such as those used in eHealth and mHealth efforts, are described in Chapter 8.

The chapter is structured with subsections for each innovation, including (1) a description of and trends in its use, (2) an example of research conducted with it, and (3) ways that it potentially increases STI risk and/or promotes sexual health (if applicable). Due to the novelty and recency of these technologies, this chapter sometimes references research on technologies in other domains (e.g., HIV, influenza) if research within the field of STIs is limited. Importantly, this chapter highlights that technology itself is just a platform/tool and therefore not problematic or beneficial but how technologies are used is what affect STI acquisition, prevention, and control. While some technologies may be associated with sexual health outcomes, the mechanisms through which effects may occur are unclear (see Chapter 8 for a discussion of possible mechanisms that may influence effectiveness). Additionally, it is likely that technology can have

a variety of impacts that could influence STIs, including at the different levels highlighted in the committee’s conceptual model (see Chapter 1).

The technologies discussed are associated with sexual health across all levels identified in the committee’s conceptual model (see Chapter 1). For example, dating apps may influence the interpersonal level, as they allow for connections between individuals, but they also may have an effect at the community level, affecting expectations more broadly. Immersive pornography, viewed on VR devices, may influence the individual level but may also have an impact at the community/institutional level by affecting norms. (See Chapter 8 for additional examples of how technology and media fit within the committee’s conceptual model.) Data from technologies, such as from a mobility/global positioning system (GPS),

which can be integrated into AI approaches, may influence all levels of the model, depending on how the data are applied.

Technological innovation has advanced greatly in recent years, but many opportunities and areas of study remain to be explored and further studied. Areas related to each of the technologies described for which evidence does not exist are noted throughout the chapter.

Overview of Technology, Media Use, and Trends

Digital technology and media use have seen shifts in the past 20 years. For example, nearly 60 percent of U.S. individuals use a streaming digital service to view television content, with Netflix as a primary platform (Liesman, 2018). Additionally, 20 percent of survey respondents

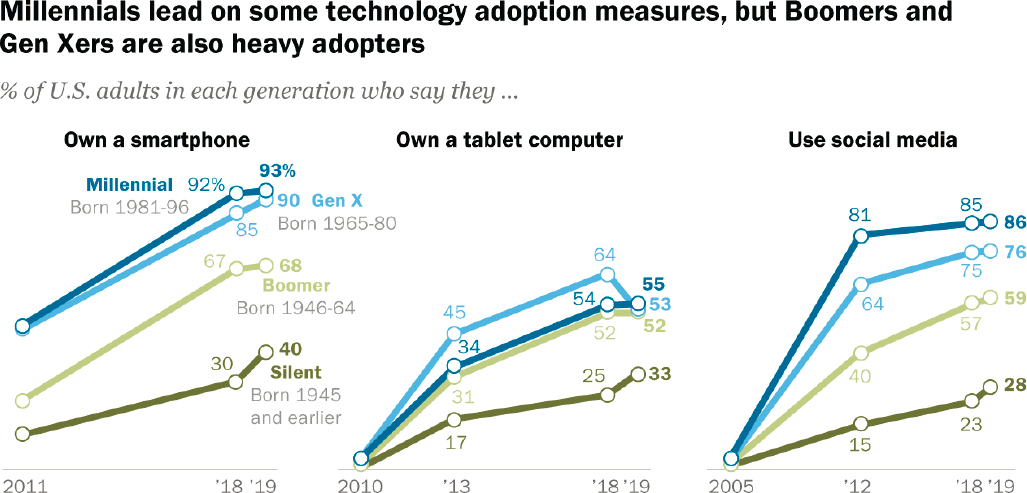

used streaming only (Liesman, 2018). The digital divide, or the ability for higher socioeconomic status groups to have greater Internet access, has decreased (Anderson and Kumar, 2019), with most U.S. individuals now having Internet access and some using smartphones for primary Internet access (Anderson, 2019). According to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, approximately 70 percent of adults who live in a household with an income of less than $30,000 per year have a smartphone, 56 percent have broadband, and 54 percent have a computer (Anderson and Kumar, 2019). These trends continue to rapidly change, as smartphones are becoming nearly ubiquitous, with 96 percent of 18–29-year-olds owning or having access to one (Anderson, 2019). Figure 6-1 shows the 2019 percentage of U.S. millennials, Boomers, and Gen Xers who said that they own a smartphone, own a tablet computer, and use social media.

Traditionally, the digital divide has been defined as the gap between people who do and do not have access to communication technology, with a focus on being able to physically access such services (Van Dijk, 2017). However, work later moved to also focus on skills and competencies (Van Dijk, 2017), including media literacy (i.e., the ability to apply critical thinking to media messages) and digital literacy (i.e., the cognitive and technical ability to navigate online environments). In a Pew Research Center survey, participants’ digital knowledge varied greatly based on educational attainment and age, with better educated and/or younger adults (i.e., those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree or under the age of 50) scoring higher (Vogels and Anderson, 2019). Research suggests that, as mobile and digital health continue to increase, limited digital health literacy may impact demographic groups that experience disparities related to health and health care (Smith and Magnani, 2019). Coupled with limited health literacy, limited digital literacy presents additional challenges in digital health services. Additionally, some people who traditionally experience the digital divide (e.g., lower-income, racial and ethnic minorities) are also populations that tend to suffer inequities related to sexual health (see Chapter 3 for a discussion on priority populations). Out of more than 1,900 women who were part of an HIV study, researchers found that daily Internet use was associated with higher quality of life, and women who had an annual income of more than $12,000 and were non-Hispanic white were more likely to have daily Internet access (Philbin et al., 2019). The authors concluded that providing reliable Internet access could improve access to health promotion and may lead to improved health outcomes.

NOTES: Those who did not give an answer are not shown. Survey conducted January 8–February 7, 2019.

SOURCE: Pew Research Center, 2019a.

TECHNOLOGIES

Social Media

Social media is the first example technology we will explore in this chapter. Social media has great potential to impact sexual health, including STI prevention and care services. Social media are websites and apps that allow users to create and share digital content; a variety of platforms are currently available. This chapter covers certain platforms, recognizing that they may be similar in some ways and different in others, depending on affordances (i.e., the benefits generated by the use of technology where behavior-oriented goals become concrete actions [Bobsin et al., 2019]).

Statistics on Use

Social media use by U.S. adults continues to increase, with 72 percent on at least one platform by 2019 (Pew Research Center, 2019a). In 2019, the most popular platforms were YouTube and Facebook, followed by Instagram, Pinterest, LinkedIn, Snapchat, Twitter, WhatsApp, and Reddit (Perrin and Anderson, 2019). Facebook, founded in 2004, was used by 69 percent of U.S. adults in 2019 (Perrin and Anderson, 2019). Since its advent, social media has continued to expand. YouTube, created in 2005, has been used by 73 percent of U.S. adults (Pew Research Center, 2019c). A similar trend occurs among teens and young adults (15–25 years old), with YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook as the top three sites, followed by Snapchat, Twitter, Pinterest, Reddit, Tumblr, LinkedIn, WhatsApp, and Periscope (Clement, 2019b).

Certain social media platforms are more popular among different demographic groups. For example, Facebook use has declined among teenagers in recent years (Anderson and Jiang, 2018), but Instagram and Snapchat are both used by more than 70 percent of 18–24-year-olds (Perrin and Anderson, 2019). These platforms provide different user characteristics, such as the ability to like and share content (Bucher and Helmond, 2018). People use platforms for different purposes (Kane et al., 2014), including to connect with friends, find employment, share health information, and other personal and professional activities.

More frequent use of social media has also led to changes in the way people acquire information. Reading of traditional newspapers for news has declined (Pew Research Center, 2019c). In 2017, only half of U.S. adults reported getting news regularly from television (Shearer and Matsa, 2018), which has also been in decline. In contrast, nearly two-thirds (68 percent) get at least some news from social media (Shearer and Matsa, 2018); Reddit, Twitter, and Facebook are the primary social media platforms, with 73 percent of Reddit users getting their news there.

Social media allows anyone to share and pass information on without an effective method for filtering out invalid sources and information; thus, misinformation1 and disinformation2 are common (Wang et al., 2019). See Box 6-2 for a discussion on misinformation, which relates to social media.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Increase STI Risk

Social media has been associated with behavior that can elevate users’ risk for STIs, causing claims that this technology increases STI transmission. For example, a study of young, urban men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women found that they used social media (i.e., Facebook and Twitter) and sexual networking/dating apps (i.e., Grindr, Adam4Adam; more information about dating apps appears in a later section) to seek sexual partners (56.7 percent), exchange sex for money or clothes (19.6 percent), or obtain drugs (9.8 percent) (Patel et al., 2016). Carmack and Rodriguez (2020) examined the influence of Facebook on sexual risk behaviors among college students. The results suggested that Facebook usage was significantly associated with intercourse without a condom and that those who used Facebook 3 or more hours per day were 1.9 times more likely to not use a condom in the past 30 days (B = .71, p = 0 .04) (Carmack and Rodriguez, 2020). This association does not necessarily indicate causality, however, and other research has not found an association between using the Internet for sexual purposes (e.g., having Internet partners) and increased STI prevalence (Al-Tayyib et al., 2009). Overall, research on this topic has been shifting from whether social media leads to increased risk to how different methods of using social media might lead to increased risk.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

Research also suggests that social media can serve as a tool to decrease STI risk, illustrating that it might both facilitate (as above) and decrease risk behaviors, depending on how it is used and by whom. A study by Stevens et al. (2017) sought to examine the influence of sexual health information sources on their subsequent sexual risk reduction behaviors among Black and Latino/a youth. They found that exposure to health messages on social media increased the likelihood of using contraception during the last sexual encounter (odds ratio [OR] = 2.69, p < 0.05).

___________________

1 Misinformation is “false information that is spread, regardless of whether there is intent to mislead” (University of Washington Bothell and Cascadia College, 2020).

2 Disinformation is “deliberately misleading or biased information; manipulated narrative or facts; propaganda” (University of Washington Bothell and Cascadia College, 2020).

Intervention studies to increase STI testing have been successful on Facebook for a variety of diseases. For example, a targeted advertisement was created for a sexual health campaign aimed at young women to promote home-based chlamydia testing, with a 277 percent increase in visits to the chlamydia testing kit page and 41 percent increase in test kit requests compared to the period before the advertisement ran (Nadarzynski et al., 2019). Other investigators have used YouTube as part of a randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of an Internet-based health and sexual education intervention among youth. The intervention group was provided links to publicly accessible educational content, such as interactive websites and YouTube videos. Participants in the intervention group had a significant reduction in condomless vaginal or anal sex compared to the control group (12.5 versus 47.6 percent, adjusted odds ratio = 7.77, p < 0.05) (Whiteley et al., 2018). Importantly, these results should not be attributed to the technology itself but to the combination of the appropriate technology and psychological intervention elements (Young, 2020) (see Chapter 8 for more information).

Mobile Apps

Mobile apps are software developed to run on smartphones and tablets across many platforms. They range in purpose, functionality, features, and activities, including games, fitness, travel, ride-sharing, entertainment, and education (Clement, 2019a). Research indicates high general interest in apps related to STIs, emphasizing their potential in supporting awareness and prevention (Jakob et al., 2020). Mobile apps can include conversational agents, such as Siri3 and Alexa,4 as well as chatbots (which can be included on mobile apps or mobile websites). Mobile apps can also include social media, dating, and other technologies listed in this chapter but are primarily described here to include those that are focused on sexual health and/or research. Therefore, this section does not mention these technologies’ potential to increase STI transmission, as specific types of apps (e.g., dating apps) related to STI transmission are discussed separately.

Statistics on Use

The popularity of mobile apps continues to grow, with 204 billion downloads worldwide in 2019 (Perez, 2020). In the Apple App Store, as

___________________

3 See https://www.apple.com/siri (accessed January 29, 2021).

4 See https://developer.amazon.com/en-US/alexa (accessed January 29, 2021).

of 2020, there were more than 48,000 health care apps available (Statista, 2021b), and Google Play had more than 47,000 (Statista, 2021a).

Examples: Potential of Technology to Increase STI Risk

See the section in this chapter on dating apps/websites for examples of potential risks.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

Mobile apps may be used to address sexual health in a variety of ways. While apps that address sexual health education may exist, a review of 2,693 apps found in a search with keywords related to sexual health found that only 25 percent (n = 697) addressed sexual health (Kalke et al., 2018). Additionally, the majority of those apps (99 percent) did not provide comprehensive programs, with only a small subset providing information on STIs and pregnancy prevention (Kalke et al., 2018). Such findings emphasize the need for collaboration between researchers and app designers to develop evidence-based apps. In terms of data collection, mobile apps allow researchers to survey participants at multiple points in time close to when an event might occur, such as through ecological momentary assessment (EMA), using their smartphone. EMA has been well received by participants in STI/HIV studies (Hensel et al., 2012; Trang et al., 2020). For example, Santa Maria et al. (2018) relied on EMA to examine the sexual behaviors of homeless youth. The study results suggested that sexual urge and drug use are factors that increase sexual activity among this population (Santa Maria et al., 2018).

A three-armed randomized control trial by Wright et al. (2018) applied ecological momentary intervention (EMI), a technique similar to EMA that instead uses participant information to tailor content provided to participant responses, to decrease alcohol consumption among young adults. The EMI group received a short text message as feedback from their EMA survey during six drinking events. The other two arms included an EMA group with no feedback and control group with no contact at all. Although investigators did not see significant differences in the number of drinks consumed by the three groups, EMI was well received by study participants (Wright et al., 2018), who stated that the feedback was useful (69 percent) and relevant (88 percent) and agreed that “receiving the messages helped me to keep track of my drinking and spending” (58 percent) (Wright et al., 2018). STI investigators may take note of EMA’s acceptability in this research field to develop a trial with feedback text messages to encourage condom use or initiate a conversation with their partner about recent STI testing. An additional component could be examining

participant location and creating an algorithm (see the data section below as an example) that provides behavioral suggestions based on the EMA response and location (i.e., completing the EMA at a bar). Such interventions may also have similarities to just-in-time, adaptive interventions, which are a type of intervention that offers tailored support at specific time points. Such interventions were found to have moderate to large effect sizes in a meta-analysis that looked at studies addressing health behaviors and outcomes but not focused on addressing STIs (Wang and Miller, 2020).

A variety of intervention types use mobile apps and may be useful for addressing STI prevention (see Chapter 8 additional information). For example, research has found a media literacy mobile app may be helpful for addressing media literacy and sexual health (Scull et al., 2018). Researchers examining a media literacy program delivered in an app to community college students found that the intervention reduced self-reported high-risk sexual behaviors and was associated with increased media skepticism. Media literacy may be useful for interpreting the complex social media environment in which people may encounter disinformation and misinformation. There are also many examples in the field of HIV of how mobile apps and other technologies more broadly can increase HIV testing and the importance of studying this work (Hightow-Weidman et al., 2018; Horvath et al., 2020; Muessig et al., 2015), which can be applied to STI prevention and control efforts. For example, researchers have studied games to improve sexual health and HIV-related outcomes, with preliminary evidence of positive effects. Increasingly, this research has been expanding to develop and test mobile gaming apps to achieve sexual health outcomes (Aung et al., 2020; Karim et al., 2020; Muessig et al., 2015). There are also a growing number of chatbots being explored for use in sexual-health-related fields (Brixey et al., 2017; Nadarzynski et al., 2020).

Dating Apps/Websites

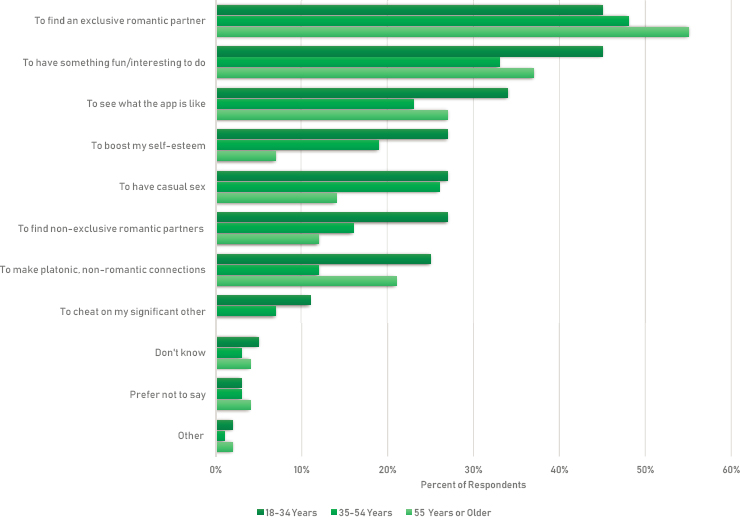

Dating apps (a type of mobile app) and websites, such as Tinder, Ship, Match, Bumble, Happn, Grindr, and Hornet, have rapidly grown in popularity. A dating app is designed to enable persons who do not know one another to meet online, often facilitating face-to-face social interactions. They often rely on GPS to locate current app users in close proximity (Burrell et al., 2012). Many are freely available for both Apple and Android devices, though some offer subscription services for extra features. As shown in Figure 6-2, dating apps and websites can be related to both risk and non-risk activities, which could include health promotion.

NOTES: Field work dates: January 29–30, 2019; 383 respondents; 18 years and older; sample: U.S. adults who have used a dating website or app.

SOURCE: Created using data from YouGov (see https://today.yougov.com).

Statistics on Use

Approximately 30 percent of U.S. adults have used a dating site or app, higher for 18–29-year-olds (48 percent) and 30–49-year-olds (38 percent) and lower for those 50 and older (16 percent) (Hobbs et al., 2017). Gay, lesbian, and bisexual adults have a higher reported rate (55 percent) of ever using a dating site or app than heterosexual adults (28 percent) (Brown, 2020; Vogels, 2020a).

As use of these apps varies by several demographic factors, so do perceptions of them. Nearly half (46 percent) of U.S. adults said that dating sites and apps were either “not at all safe” or “not too safe,” but younger respondents, LGBTQ+ respondents, and those with higher education were more likely to see them as “somewhat safe” (Anderson et al., 2020). People may use dating apps for a variety of reasons, from finding a long-term partner to a casual “hookup” (Hobbs et al., 2017). Although 26 percent of respondents thought dating sites and apps have a mostly negative effect on dating and relationships (Vogels, 2020a), users may find dating apps to be more efficient than other methods of searching for a

partner, believe they can lead to an expanded social network, or see them as an opportunity to highlight certain aspects of themselves to prospective partners (Hobbs et al., 2017).

Example of Potential STI Risk Related to the Technology

A review of Tinder that included 34 articles found that, while casual sex occurred, sexual activities outside of a committed relationship were the main predictor of casual sex (Ciocca et al., 2020). Men also used Tinder more for casual sex in comparison to women (Ciocca et al., 2020).

Chemsex, the use of drugs during sexual intercourse, which is significantly associated with bacterial STIs, was studied among MSM in the Netherlands who were recruited either from a dating app (Grindr) or an STI clinic. Chemsex was found to occur at a higher rate among dating app users (29.3 percent) compared to STI clinic visitors (17.6 percent) (Drückler et al., 2018). Compared to those from the clinic, participants from the dating app reported lower frequency of sober sex within the past month (87.0 percent versus 76.8 percent; p < 0.001). A similar trend was seen by Beymer et al. (2014) for those who used dating apps to find sexual partners. App users had greater odds of testing positive for gonorrhea (OR: 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06–1.48) and for chlamydia (OR: 1.37; 95% CI 1.13–1.65) compared to those who met partners through in-person methods only (Beymer et al., 2014). Apps like Tinder (Timmermans and Courtois, 2018) and Grindr (Licoppe et al., 2016) may facilitate sexual encounters for those who intend and are motivated to use that app to find sexual partners, with frequent in-person meetings significantly associated with the number of one-night stands and casual sexual encounters (Timmermans and Courtois, 2018).

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

Research has also investigated dating apps as a platform for prevention messaging. A study examined the effectiveness of advertising in various forms of digital tools for prevention messages to MSM during a hepatitis A outbreak. Investigators found that apps garnered 85 percent of the impressions during the campaign. Click rates also differed across dating apps and websites, with significantly more clicks on ads on Grindr compared to websites, while clicks on PlanetRomeo and Scruff were significantly lower than websites (Ruscher et al., 2019).

Sun et al. (2015) used four different dating apps targeting the MSM community to determine their acceptability and feasibility in providing sexual health messages: 63.8 percent of participants were receptive to health information presented in dating apps and 26 percent of initiated

chats resulted in requesting referrals to local HIV/STI testing sites (Sun et al., 2015). Huang et al. (2016a) examined the effectiveness of targeted advertisements with online requests of free HIV self-test kits among Black and Latino Grindr users: the advertisement led to 284 unique visitors to the study website per day during the campaign and resulted in 334 requests for kits (Huang et al., 2016a). This approach could be similarly applied for STI prevention interventions.

In addition, some dating apps targeting MSM have brought increased attention to HIV status, with information available on profiles related to testing status and timing (Howell, 2019; Patterson, 2019). A review of safe sex messages in dating apps (Huang et al., 2016b) found that, of 60 dating apps reviewed, only 9 included sexual health content; 7 of those apps were targeted toward MSM. See Chapter 3 for a discussion of MSM as a priority population and Chapter 2 for a discussion of disassortative mixing and social networks (an important consideration for STI prevention and control).

Online Pornography

With the increase in technology availability, online pornography has also become more accessible. Much of this is free, making it highly accessible to young persons and even children.

Statistics on Use

With the expansion of the Internet, audiences who view pornography have increased, as cost and social stigma barriers are eliminated when materials are accessible online. A cross-sectional convenience survey found that 75 and 56 percent of men and women, respectively, watched pornography videos (Solano et al., 2020), with such videos being easy to access online. In their sample of 1,392 adults aged 18–73, the researchers found that 92 percent of men and 60 percent of women had consumed pornography in the past month across various platforms (Solano et al., 2020). Videos, pictures, and written pornography were the most common formats (Solano et al., 2020).

Even when people are not searching for sexually explicit content, it may be displayed online. In a meta-analysis of youths’ exposure to unwanted online sexual media, researchers found that approximately one in five adolescents was exposed to unwanted sexually explicit materials online, and one in nine received online sexual solicitations (Madigan et al., 2018).

Examples: Potential of Technology to Increase STI Risk

In a review of 20 years of pornography research, Peter and Valkenburg (2016) found that adolescents’ use of pornography was associated with more permissive sexual attitudes, increased casual sex, and more sexual aggression. Other reviews have also noted the association between pornography and sexual risk behaviors, including decreased condom use (Lim et al., 2016). However, such research often relies on correlation and does not demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship (Lim et al., 2016). Similarly, in a meta-analysis of nonexperimental studies, researchers noted a significant association between violent pornography use and attitudes that support violence against women (Hald et al., 2010), but other factors may explain the association, such as men with a violent disposition seeking out that content (Lim et al., 2016). Lim et al. (2016) conclude that while online pornography is “extremely common,” its impact on outcomes such as sexual health and well-being are uncertain. Similarly, Peter and Valkenburg (2016) noted a dearth of “consistent, robust, and cumulative evidence” between pornography use and sexual risk behaviors (p. 523).

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

Peter and Valkenburg (2016) noted the bias of pornography research in focusing on potential negative outcomes. Other reviews have also mentioned this tendency (Lim et al., 2016). As Lim et al. (2016) note, there are advocates for the benefits of pornography, and the body of supporting literature is limited but growing. The research primarily relies on subjective assessments (Lim et al., 2016). Research on Danish and Australian adults, for example, found from self-reports that participants believe pornography has more positive than negative effects, including feelings of comfort and open-mindedness about sex, is associated with an improved sex life, and is associated with more attentiveness to a partner’s sexual pleasure (Hald and Malamuth, 2008; McKee, 2007).

Virtual Reality/Augmented Reality

VR is a computer-generated environment that allows users to experience immersive realistic or fictional situations with which they can interact. Oftentimes, users require special equipment (such as Oculus or Google Cardboard). VR apps have allowed individuals to experience online pornography in a more realistic, immersive way, which has currently unknown effects on the field of STI research.

Statistics on Use

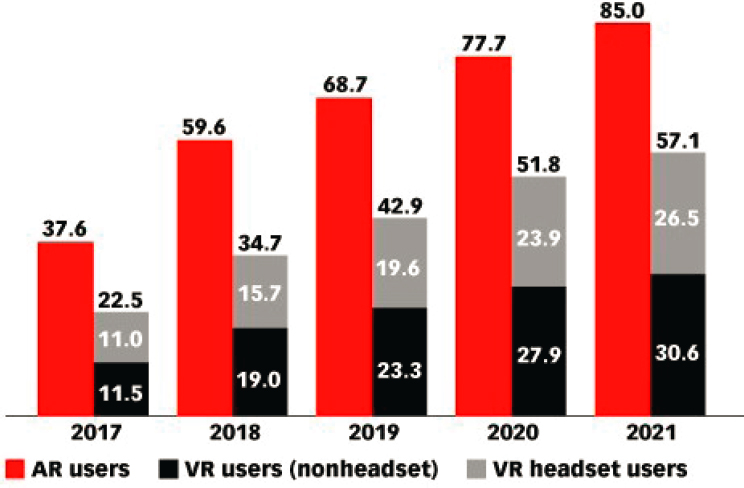

Industries that invest in VR/AR/mixed reality include gaming, health care and medical devices, education, military and defense, manufacturing and automotive, movies and television, live events, workforce development, marketing and advertising, retail, and real estate (Tankovska, 2020). Figure 6-3 shows the growth in millions of VR and AR users from 2017 through 2021 (estimated).

Examples: Potential of Technology to Increase STI Risk

VR and AR apps related to sexual experiences have rapidly gained in popularity. In an unpublished study, Bychkov and Young (2017)5 found that within 1 month in 2017, on YouTube and Pornhub alone, a search for

NOTES: Virtual reality (VR) users are individuals of any age who experience VR content at least once per month via any device; augmented reality (AR) users are individuals of any age who experience AR content at least once per month via any device.

SOURCE: eMarketer, 2019.

___________________

5 Unpublished manuscript by David Bychkov and Sean D. Young, provided to National Academies staff on December 8, 2020, for the Committee on Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Infections in the United States. Available by request from the National Academies Public Access Records Office via email at PARO@nas.edu.

videos of “sex” uncovered more than 300 VR-related titles that gained more than 13 million views. Although limited research has been conducted on this topic, the fast growth and potential of VR for immersive sexual encounters may influence STI risk.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

The immersive nature of VR opens many potential uses, depending on how the devices are deployed. For example, VR provides an opportunity for people to engage in virtual (rather than real-world) high-risk behavior, thus potentially reducing the risk for STI transmission through physical sex. Researchers have used VR for health outreach (Khan et al., 2012; Read et al., 2006), for example, by targeting efforts toward high-risk individuals in engaging ways to promote testing, safe sex practices, and condom use (Mustanski et al., 2017; Read et al., 2006). In addition, VR might be an effective tool to mitigate STI-related stigma by enabling individuals to talk about STIs to other 3-D virtual humans. VR has already been used clinically to relieve symptoms of anxiety, phobias, and posttraumatic stress disorder and the stigma around sharing health information (Rizzo and Shilling, 2017).

VR games might be developed to help increase self-efficacy in discussing STI testing with sexual partners or a health care provider. The games could provide role-play situations and environments offering conversations that allow users the opportunity to think, learn, and gain confidence in how to safely and healthily respond to different scenarios that might present a risk.

Read et al. (2006) studied the effect of a virtual environment on participants’ behavior and engagement in safer sex practices through a randomized controlled trial. The intervention group received peer counseling and an interactive video, while the control group received only the peer counseling. The intervention group had higher levels of protected anal sex and lower levels of condomless anal sex compared to the control group (Read et al., 2006).

Text Messaging

Text messaging, or texting, is sending electronic messages to one or more mobile devices. There are now various options for messages, depending on the platform, such as short message service (SMS) or multimedia messaging. Although text messaging started in the 1990s (Erickson, 2012), it is now ubiquitous and has been used in different ways, including those relevant to STIs.

Statistics on Use

Ninety-six percent of U.S. individuals own a cell phone as of 2019; 81 percent own a smartphone, a substantial increase from 35 percent in 2011 (Pew Research Center, 2019b). These numbers are even greater for younger age groups: 99 percent of 18–29-year-olds own a cellphone, with 96 percent owning a smartphone. The majority of cell phone owners send text messages (Pew Research Center, 2019b).

Examples: Potential of Technology to Increase STI Risk

According to a systematic review of 31 studies, sexting has been defined by researchers as sending sexually suggestive texts and/or sexually explicit photos (Klettke et al., 2014). Among 13 studies with an adult sample, with 9 of them on undergraduate university students, the estimated mean prevalence of sexting was 53.5 percent. The review noted that, based on the studies analyzed, 10.2 percent of adolescents reported sexting, with 11.9 percent specifying photo content. More adolescents reported receiving than sending sexts. Among studies that measured sexual activity, all found that people who reported sexting were significantly more likely to be sexually active. Among the two studies reviewed that examined the presence of STIs, one study noted that people who sexted were more likely to report being diagnosed with an STI and the other found no association.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis on sexting behaviors among youth, researchers concluded that sexting has increased in recent years and as youth age, and that sexting without consent also occurred, through either forwarding (12 percent) or receiving (8.4 percent) a sext (Madigan et al., 2018). In a separate meta-analysis of sexting among youth, researchers found sexting associated with sexual activity, having multiple sexual partners, and lack of contraception, as well as other health outcomes, and such outcomes were stronger in younger adolescents (Mori et al., 2019). The authors concluded that additional longitudinal work is needed to assess directionality and further understand the mechanisms of such correlations. Both Madigan et al. (2018) and Mori et al. (2019) identified a need to raise awareness related to digital health and safety among youth to navigate these issues.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

A variety of text message–based interventions exists for sexual health promotion (Lim et al., 2008; Willoughby and Muldrow, 2017). Lim et al. (2008) concluded that while SMS has been used in many ways to improve

sexual health, studies of the effectiveness of such efforts are limited. In a meta-analysis of the efficacy of text message–based interventions for health promotion more generally, researchers found a mean effect size of d = .329, showing that such interventions can have moderate effects (Head et al., 2013). Messages that were tailored and targeted were the most efficacious. A newer meta-analysis again focused on text messages to change health behavior more generally, which included four studies on text messaging for sexual health promotion, found an overall effect of d = .24 (Armanasco et al., 2017). Interventions of 6–12 months were found to be most effective, with no differences based on tailoring or targeting message content. In a randomized controlled trial that examined the effect of e-mail and text messaging on the sexual health of young people (ages 16–29), after the yearlong intervention, the intervention group had higher STI knowledge and its female participants were more likely to have received an STI test or discussed sexual health with a provider (Lim et al., 2012) (see Chapter 8 for additional information on digital interventions).

Digital Contact Tracing and Digital Exposure Notification

Current STI contact tracing methods typically involve having the patient inform partners or a health department inform people about a positive test result (NCSD, 2017). The evolution of contact tracing from paper to digital (Ha et al., 2016) to mobile app (Apple and Google, 2020) is documented for airborne communicable diseases and has recently been applied to COVID-19.

Statistics on Use

The most recent data on digital contact tracing apps relates to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the largest country-wide adoption occurring in Australia, Turkey, and Germany (Clement, 2020). The United States was not included in this list due to lack of adoption of a national digital contact tracing method (it was left up to states). Digital contact tracing and exposure notification have been available for STIs for a number of years, and the increasing use of these apps as a result of the pandemic will likely lead to greater future use for STI prevention and control.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Increase STI Risk

There are not clear examples of how digital contact tracing and exposure notification apps may be related to increased STI risk.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

Partner notification apps for STIs already exist. As dating apps are a popular method to meet potential sexual partners, a contact tracing app that uses information from the user’s dating apps could be developed to notify partners of seroconversion. Research has already found electronic communication technology to notify partners about STIs as an acceptable strategy (Pellowski et al., 2016). In a review of 23 studies of technology (e.g., the Internet, text messaging, or phone calls) for STI partner notification, researchers found high interest and acceptability of e-notifications. Despite this, the researchers noted little evidence of use of e-notification services and that such services may work best for more casual partnerships (Pellowski et al., 2016). This would support the example described above as a possible scenario or use of technology for partner notification and potentially alleviate some of the barriers previously noted for such resources. Current studies evaluating the success of digital contact tracing for COVID-19 will help to inform future needs and the potential role of these technologies in STI prevention and control.

Wearable Devices/Biosensors

Sensors are increasingly being incorporated into public health research and practice, as well as daily life for health monitoring. A large number of sensors are available for detecting health-related outcomes, including movement, sleep, and biochemical reactions. Many of these sensors are packaged into convenient wearable devices, including Fitbits and Apple watches, to provide a user-friendly way for individuals to monitor their health. Data from sensors can therefore be included into mobile phone apps, or they can be collected through standalone devices other than a mobile phone. Although limited research has studied wearable sensors in the context of STI prevention, a number of potential application areas are available and will likely be implemented in the near future, especially as a result of the rapid advancements in sensors for detecting infectious diseases due to the COVID-19 pandemic, making it important to be aware of this growing area.

Statistics on Use

There are many types of wearable devices and biosensors, and wearables continue to gain popularity. For example, one in five people in the United States uses a fitness tracker or smart watch (Vogels, 2020b). This chapter does not go into detail on all possible types of wearables but discusses some specifically related to STIs.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Increase STI Risk

There are not clear examples of how wearable devices and biosensors may be related to increased STI risk.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

Wearable condoms are one example of a sensor that can collect physiological data and function beyond prophylactic needs. For example, iCon is a novel wearable device that tracks performance during sexual intercourse, including calories burned and thrust (British Condoms, 2020). The Smart Condom Ring uses nano-chip and Bluetooth technology to transmit data to the user’s cell phone. The developers also claim to have a feature that can detect STIs such as chlamydia and syphilis through built-in indicators (PRWeb, 2017).

There has also been development in modern condoms, designed to increase condom use. For example, two graduate students created a condom prototype with electrodes that sends electrical impulses to the penis to stimulate pleasure during sexual intercourse (Dodge, 2014). Such innovative design, if successful in increasing pleasure, might increase frequency of condom use and thereby decrease STI transmission.

Television, Radio, and Print

Television, radio, and print have been prominent channels of communication for decades. However, we have seen and continue to see shifts in how these technologies are used. Television, for example, has moved from a communal form of entertainment in the 1950s, when it first became available, to individual viewing opportunities on a variety of devices. Although use of these devices is declining compared to use of newer digital tools, making them less likely to be considered a “technology,” they are worth describing in this chapter, as they are the oldest current forms of media and continue to influence the ways in which more modern technologies evolve.

Statistics on Use

Traditional television use peaked in 2010, with U.S. households watching approximately 9 hours per day (Madrigal, 2018). This number has declined over the past few years, possibly due to the other ways people can obtain media content (e.g., YouTube, Facebook) (Madrigal, 2018); but, on average, adults are still watching more than 4 hours of television content per day (Nielsen, 2019b), with older adults spending the greatest amount of time watching television (Nielsen, 2019a). Although

people spend less time with radio overall, it still accounts for nearly 2 hours of daily media time for U.S. adults (Nielsen, 2019b). Streaming has also become a popular way to view television content and access music, with COVID-19 stay-at-home orders further associated with increases in streaming (Nielsen, 2020).

How consumers interact with print media also continues to shift. The majority of U.S. adults report having read a print magazine in the last 30 days, but 42 percent of survey respondents had read a magazine distributed electronically (Nicholas and Mateus, 2018).

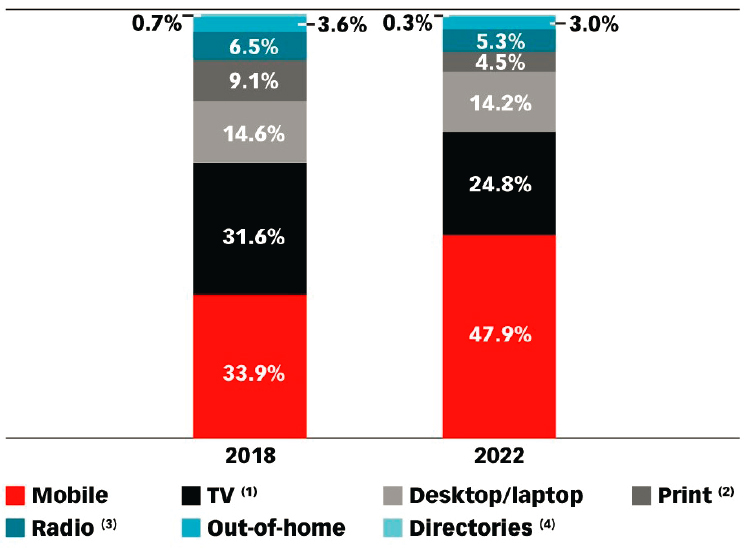

Figure 6-4 shows the percentage of total media advertisement spending by type of media in 2018 and 2020. As later sections address, advertising on mobile devices has already exceeded other types of communication tools. This trend is expected to increase, making it important for public health departments to invest in digital approaches.

NOTES: Percentage of total. Numbers may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding; (1) excludes digital; (2) includes newspapers and magazines, excludes digital; (3) excludes off-air radio and digital; (4) print only, excludes digital.

SOURCE: eMarketer, 2018.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Increase STI Risk

Rape myth acceptance (false assumptions that result in denying or excusing sexual violence) is a troubling finding for researchers, as it may portend increased risk for intimate partner violence (Yapp and Quayle, 2018) or increased STI risk behaviors. A meta-analysis of 59 studies found that exposure to sexual media content had a significant effect on sexual attitudes and behaviors (Coyne et al., 2019). Participants with greater exposure had more permissive sexual attitudes and rape myth acceptance. Increased exposure was positively associated with general sexual experience and higher-risk sexual behaviors (e.g., number of partners, no contraception) and negatively associated with age of sexual initiation (people exposed to more sexual media initiated sex younger). The overall effect size was small (r = .14); however, stronger effects were found for adolescents than young adults, boys than girls, and white compared to Black participants. Previous meta-analyses have also found effects, although effect sizes and specific outcomes may differ (Ferguson et al., 2017; Fischer et al., 2011).

Such effects have also been noted in specific media types. For example, a meta-analysis of 26 studies of sexual content in music and its association with sexual attitudes and behaviors among adolescents and young adults found significant if small effects (r = .25 for attitudes and r = .16 for behaviors) (Wright and Centeno, 2018). Different types of music exhibited different effects. Wright and Centeno’s (2018) meta-analysis supports the findings in Coyne et al. (2019), finding again that effects were stronger for adolescents than young adults.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

Media, including television, radio, and print, may also serve as a useful tool for promoting behavior change. In a meta-analysis of 63 studies on the effects of health communication mass media campaigns on health outcomes across a variety of health topics (not specific to STIs), campaigns affected health attitudes and behaviors (Anker et al., 2016). On the topic of sexual health, a number of campaigns have focused on HIV prevention. In a meta-analysis of mass media interventions for HIV prevention, campaigns were associated with increased condom use (d = .25) and knowledge, including on HIV transmission (d = .30) and prevention (d = .39). Longer campaigns were associated with increased condom use (LaCroix et al., 2014). These findings highlight the applicability of mass media campaigns to sexual health, more broadly. Additionally, campaigns can be useful for prompting interpersonal discussion. A meta-analysis of 28 studies, though not specific to STIs, found that conversations generated from campaigns had a positive effect on the targeted outcomes (Jeong

and Bae, 2017). Relatedly, interpersonal discussion can affect outcomes pertinent to sexual health. For example, in a study of adolescents who viewed a television show featuring a pregnancy announcement by a main character followed by a discussion of the effectiveness of condoms (i.e., Friends), youth who talked to an adult reported that they were more likely to learn about condoms from the episode and perceive condom efficacy as higher (Collins et al., 2003).

Although campaigns may positively affect sexual health, they can be expensive to create and distribute. Health communication campaigns may benefit from formative research, a grounding in theory, and audience segmentation (Noar, 2006), which can contribute to creation costs. However, state and local health departments may lack resources to create, distribute, and evaluate campaign messages (Ruebush, 2019; Walton, 2019; Weiss, 2019). Some campaigns have been made more widely available, such as Get Yourself Tested (CDC, 2019). For this campaign, CDC made available sample social media posts, customizable articles, graphics, and a widget that allows users to locate an STI testing location as an option for STD Awareness Month. Preliminary research found that the campaign reached youth and, based on STI testing data pre- and post-campaign, may have been associated with increased STI testing (Friedman et al., 2014). In a survey of 4,017 adolescents and young adults, participants aware of the campaign were more likely to report engaging in STI and HIV testing and talking to partners and providers about it (McFarlane et al., 2015). Research that has looked at versions of the campaign adapted for a high school setting found promising results, with increased testing in participants from a school that implemented the campaign compared to one without it (Liddon et al., 2019).

Entertainment education, embedding educational content in entertaining formats (Singhal and Rogers, 2012), is another strategy that often uses media formats, such as television and radio, to positively influence health outcomes. Such work has been conducted in a variety of settings, including television, radio, and print, and through digital media, including social media and text messaging (Moyer-Gusé et al., 2011; Rideout, 2008; Smith et al., 2007; Willoughby et al., 2018). A meta-analysis of 10 studies found small but significant effects of entertainment education narratives on sexual behaviors, with an association with reduced number of partners, reduced condomless sex, and increased STI testing and management (Orozco-Olvera et al., 2019).

Electronic Health Records

In contrast to the communication methods described above that are primarily focused on the general population/individual, EHRs are

primarily designed for health providers and administrators. EHRs have evolved from a billing and accounting system to also being a patient care delivery and management system, patient educational tool and resource, and a system for administrative support processes (Reza et al., 2020). The benefits of EHRs include improved patient care, care coordination among health providers, reduced unnecessary tests and procedures, direct access to one’s own health records, improved patient participation, and reduced paperwork (HealthIT.gov, 2018). In addition, EHRs can also be useful for public health surveillance, reporting of notifiable conditions, and outbreak monitoring and response (Reza et al., 2020).

Statistics on Use

More than 85 percent of office-based physicians have reported using any EHR (CDC, 2020). In 2017, hospitals with a certified EHR ranged from 93 percent in small, rural, and critical access hospitals to 99 percent in large hospitals (more than 300 beds) (HealthIT.gov, 2019).

Examples: Potential of Technology to Increase STI Risk

There are not clear examples of how EHRs may be related to increased STI risk.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

Marcus et al. (2019) developed a machine learning model designed to identify patients at risk of HIV among adult members of a large health care organization. Investigators used 81 EHR variables to predict incident cases within 3 years of the study period. The full model, which retained 44 predictive variables, was able to discriminate between HIV cases and non-cases (C-statistic of 0.86, 95% CI 0.85–0.87) (Marcus et al., 2019). In clinical settings, the implications of this work are that patients identified as high risk for HIV might be targeted and recommended prevention methods, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis. Similar work could be applied in the context of STIs.

Furthermore, clinical decision support (CDS) tools (e.g., guidance and alerts delivered through an EHR to health care providers to remind them of STI screening guidelines during a patient visit) might be integrated into patient care (Chadwick et al., 2017; Goyal et al., 2017). However, given the issue of “alert fatigue” (an increasing number of EHR alerts being ignored by health providers) (Ancker et al., 2017), the benefits and risks of developing CDS tools for STI clinical settings needs to be thoroughly considered in advance. CDC is taking steps to make the STI treatment guidelines

available electronically and in real time and make screening and treatment guidelines readily accessible in EHRs to guide clinician treatment (NAPA, 2018). In 2019, a pilot project began, to demonstrate the feasibility of posting the treatment guidelines in the cloud and working with EHR vendors to automatically update screening and treatment recommendations whenever CDC updates the guidelines to facilitate updating CDS tools in electronic medical records. Findings from the pilot show that further refinement of the guidelines is needed “to incorporate flexibility to support clinician’s local workflows and tele-health considerations” and emphasize the need for “more open Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) to integrate with clinician workflow and additional study to understand barriers for CDS adoption amongst clinician users.”6,7

In the community setting, researchers have examined the impact of EHRs in facilitating a discussion about STI testing between college students and their potential sexual partners. Survey respondents reported that access to their EHRs would help lead them to discuss STI testing earlier in the relationship (60 percent) and improve communications about STI prevention (63.6 percent) (Jackman et al., 2018).

EHRs as an avenue to increase testing among youth was examined in a hospital emergency department by Ahmad et al. (2014). Youth who visited the emergency department were asked to complete a self-interview about their sexual history. Physicians were prompted by the EHR to view these answers based on the audio-enhanced computer-assisted self-interview and decision tree and offer recommended testing to at-risk youth. STI testing increased during the study period, to 17.8 percent compared to 3 months before (9.3 percent) and 3 months after (12.4 percent) (Ahmad et al., 2014). Although the intervention mainly focused on implementation, this study highlights EHRs as a vehicle to potentially target at-risk populations to increase desired preventive behaviors. Finally, EHRs can also facilitate opt-out screening for STIs, such as chlamydia screening for women under 25 (Tomcho et al., 2021).

___________________

6 Middleton, B., M. Burton, K. Simon, S. Farzeneh, N. Mohanty, R. Padilla, S. Pohl, J. Carr, and N. V. Collins. 2020. Clinical decision support in the real world: Learnings from a scalable CDS implementation and suggestions for accelerating adoption and ensuring future success. Apervita, AllianceChicago, and the Public Health Informatics Institute. Report from CDC, provided to National Academies staff on November 6, 2020, by Raul Romaguera for the Committee on Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Infections in the United States. Available by request from the National Academies Public Access Records Office via email at PARO@nas.edu.

7 Middleton, B., and N. Mishra. 2018. CDS in the cloud: Deploying a CDC guideline for national use. Presented at HIMSS18, Las Vegas. Presentation from CDC, provided to National Academies staff on November 6, 2020, by Raul Romaguera for the Committee on Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Infections in the United States. Available by request from the National Academies Public Access Records Office via email at PARO@nas.edu.

Blockchain

Blockchain technology is a relatively new and growing type of infrastructure that may affect many areas of sexual health in the future. Blockchain is a shared, immutable repository of linked data. The technology has been suggested to benefit users by increasing security and transparency because all transactions are chronologically recorded and difficult to manipulate, even by the data owner (IBM, 2020). It is increasingly being discussed as a potential tool for biomedical and health care applications to improve medical records management, enhance insurance claim management, accelerate clinical research, and incorporate an advanced biomedical data ledger, or accounting system, for data management (Kuo et al., 2017).

Statistics on Use

In a 2017 survey of nearly 3,000 global C-suite executives, about 33 percent reported considering or already engaging with blockchain technology (IBM, 2017), with health care fast becoming a growing industry in blockchain adoption (Casino et al., 2019; Hogan et al., 2016).

Examples: Potential of Technology to Increase STI Risk

There are not clear examples of how blockchain may be related to increased STI risk. As cryptocurrency uses blockchain, see the relevant section in this chapter, which provides examples of bitcoin and potential risk.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

Although no known research studies exist on the utility of blockchain in decreasing STI transmission, Hopper conceived an idea using a popular digital tool. To decrease STI transmission and improve transparency about current infection status with a potential sexual partner, Hopper suggested merging blockchain technology with a dating app. For example, before using the dating app, there could be a two-step verification process whereby a user would (1) register for an account and (2) get tested for a full panel of STIs (Hopper, 2019). Because users own their testing results, they could give permission for the testing facility to share this verified information with the app.

Blockchain technology might also be applied to sex work/transactional sex. Similar to Hopper’s idea, blockchain might be used to verify clients and their STI status, creating a safer work environment for sex workers. For example, Gingr is an end-to-end scheduling platform that

uses blockchain technology and allows booking a meeting location and accepting a payment method (van Rijt, 2019). Through Gingr, sex workers might be able to reduce their STI risk and improve sexual health (oreofekari, 2019).

Cryptocurrency

Cryptocurrency is virtual, does not exist outside of the digital world, and uses blockchain technology to record and facilitate transactions on distributed networks (FTC, 2018), making it one type of example of how blockchain technology might influence sexual health. In 2009, Bitcoin, the first established cryptocurrency, was made publicly available; by 2011, several alternatives began to emerge (Marr, 2017b). As people have secretly purchased illicit items (e.g., drugs) through the “underground” Internet with cryptocurrency, it is also relevant to sexual health because it is likely being used for transactional sex.

Statistics on Use

Cryptocurrency’s popularity has grown exponentially. It is traded in billions of dollars per day (Kharif, 2019). Many companies and industries, such as Microsoft, Overstock, BMW, and AT&T, accept it as payment (Paybis, 2019).

Examples: Potential of Technology to Increase STI Risk

Although limited research has been conducted on this topic due to the recency of the technology, numerous popular press examples report on cryptocurrency in transactional sex and illicit activities (Andrews, 2019; Foley et al., 2018; Nguyen, 2015).

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

Similar to blockchain, there are no known academic studies on the impact of cryptocurrency on STIs. It is an acceptable form of payment on Gingr, however, and could be applied in the blockchain example above (Flavour of Boom, 2019). Another idea might be to partner with Safely, a mobile app focused on sexual health, or a similar app to allow marginalized communities to pay for STI self-tests using cryptocurrency. This would obviate the need for a bank account or credit card to access testing and would provide privacy and confidentiality for the user. Additionally, the Safely app does not require a physician’s order (The Safe Group, n.d.),

which could be convenient for those without a primary care physician or who might feel uncomfortable getting tested at a clinic due to stigma.

“Big Data” and Artificial Intelligence

It is estimated that 2.5 quintillion (i.e., 1 million times 1 million) bytes of data are being created by technologies every day, with 90 percent of the world’s data created within the past 2 years (Domo, 2020). This includes a large amount of “social data,” such as from social media, wearable devices, and Internet search, which can provide information about people’s attitudes, behaviors, locations, mobile apps and websites used, searches for health information, and other digital behavioral outcomes (Evans and Chi, 2008; Olshannikova et al., 2017; Olteanu et al., 2019). It was previously not possible to aggregate and analyze such a large amount of data due to technology infrastructure limitations. Recent advances in “big data” infrastructure tools and AI modeling methods, however, have made it possible to collect, aggregate, and analyze massive amounts of data. These newer modeling methods—often interchangeably called “AI,” “data science,” “machine learning,” and “big data statistical modeling” (these terms and approaches do differ, but that is not essential to this chapter)—enable the ability to find patterns and associations within data at a faster pace than ever before. Although big data is not a standalone tool like the other technologies described above (e.g., social media, mobile apps), it has been included in this chapter because the technologies described above often lead to massive amounts of data that can be analyzed using “big data” modeling methods.

Although these data are being analyzed to gain insights about individuals, their behaviors, health outcomes, and other factors, they can also help generate insights and approaches into new methods of identifying and engaging people to do things.

Companies such as Google, Amazon, and Facebook have led the way in applying these new modeling methods to understand and predict human behaviors, often with a goal of identifying people who will be most likely to purchase specific products or click on advertisements. Companies have used massive amounts of data from their users to send them advertisements, improve features, and otherwise analyze user behavior. For example, in the domain of sexual risk, hookup/sexual encounter mobile apps use large amounts of data on their users’ locations, sexual identities, HIV status, and other data to tailor information for their users to make it easier for them to find sex partners.

These data have paved the way for new ways to conduct health outreach by identifying patients most in need and most likely to be responsive

to outreach and to expand the use of AI methods and tools in health settings outside the hospital and clinic (Aggarwal et al., 2020). Health-related companies, such as pharmaceutical companies, are already beginning to purchase and incorporate these types of data and digital communication outreach approaches. For example, a pharmaceutical company interested in recruiting STI patients for a clinical trial or to advertise a medication can target mobile devices based on statistical datasets, including mobility patterns. The company can access data on STI patients via a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant dataset, use AI/statistical approaches to identify millions of mobile devices that fit the (statistical) profile of individuals likely to have contracted an STI, and serve mass advertisements to these devices. Compared to typical methods of online outreach, such as Facebook or Grindr advertisements, device ID outreach methods can more accurately identify and engage a substantially larger group of participants. The implication is that CDC and health departments could apply these methods to scale their outreach efforts quickly.

These AI-based digital outreach methods are increasingly being used during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the need to identify and engage patients online so as to adhere to social distancing policies. In fact, these methods are already being applied by health departments, including CDC, to COVID-19 prevention (Ad Council, 2020). In the next 10 years, they may become a mainstream part of public health outreach and engagement, including for sexual health.

However, a number of potential implementation-related issues exist, including ethical issues in the way these data are collected, analyzed, and used, making it important to continually explore these changing ethical questions and consider the rapid changes in technologies during implementation, as many of the dominant approaches in digital advertising just 2–4 years ago are being phased out due to new methods designed to improve privacy and effectiveness of outreach.

Examples: Potential of Technology to Increase STI Risk

Data from AI and related technologies could be used in ways that might increase risk for STIs. For example, data/hookup apps could purchase and/or use their own online data collected on users to identify individuals most interested in purchasing sex in order to serve ads to these individuals (and the app owners are likely already doing so). Individuals may be able to use data themselves to search through thousands of recent classified advertisements to find other individuals wanting to have or

exchange sex with them, potentially putting them and others at risk for STIs (Wang and Young, 2021).8

Examples: Potential of Technology to Decrease STI Risk

Similar to private-sector companies and corporations, researchers and public health departments can also analyze large amounts of data to inform their surveillance and intervention efforts, and many have already begun to study and implement these approaches. For example, Internet search data from Google and social media data from Twitter have been used to predict future syphilis cases (Young et al., 2018a,b). Mobile phone app data can be analyzed to identify individuals’ locations and map potential areas of risk (Duncan et al., 2018); social network and text data from social media sites can be used to monitor STI- and HIV-related trends in discussion topics and predict future testing rates (Ireland et al., 2016; Schneider et al., 2013; Young and Jaganath, 2013; Young et al., 2014). Furthermore, website analytics data (e.g., Google Analytics) can inform surveillance and intervention efforts by identifying whether, when, and how people are visiting websites (Johnson et al., 2016; Young et al., 2018b). All of these types of analyses can be integrated into mapping and other surveillance software to provide near-real-time data on individuals’ HIV- and STI-related perceptions of risks, behaviors, and outcomes (Benbow et al., 2020). Finally, integrating these data and models into interventions has great potential. For example, public health departments may be able to send advertisements to individuals identified by AI models as at risk for STIs and incorporate other intervention methods described above.

There are two primary methods of research with technology data: population-level and individual-level analyses. The former typically involve publicly available, naturally occurring data (e.g., tweets that are viewable by anyone). Studies using these data have rapidly collected data from many users (e.g., hundreds of millions of users within a few months). Population-level data, however, typically lack personal identifiers and personally linked health information, making them appropriate for surveillance efforts and/or models designed to predict trends at the population or regional levels rather than to inform prevention or treatment at an individual level.

In contrast, individual-level analyses involve data that are typically private, from individuals, and require user consent. Because

___________________

8 Unpublished manuscript by Jason Wang and Sean D. Young, provided to National Academies staff on February 2, 2021, for the Committee on Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Infections in the United States. Available by request from the National Academies Public Access Records Office via email at PARO@nas.edu.

individual-level analyses require recruiting individuals to provide their data (e.g., by consenting to download an app or share their social media usernames or other online activity), individual-level analyses and models typically have a much smaller number of individuals and data points compared to population-level analyses. Individual-level data analyses, however, can have higher validity and address many of the limitations of population-level analyses.

One primary benefit of digital data for surveillance is the ability to address limitations in current surveillance methods. For example, traditional surveillance methods typically rely on case reporting, surveys, interviews, and other direct patient data collection and so often suffer from long time lags in reporting, aggregating, and releasing data, often when it is urgent to access these data to prevent transmission. Similarly, these methods are costly, are time consuming, require tremendous financial and personnel resources to scale and reach a large number of people (e.g., large-scale campaigns to promote testing and treatment), and can contain confidential patient information, decreasing the likelihood that all local health departments would have the resources to use them frequently.

In contrast, technology data are often available in near or perfect real time, free, publicly available, and, of course, massive compared to traditional surveillance data, helping to address limitations in current surveillance methods and enabling these data to be used as an additional surveillance tool. Some limitations of technology data include lack of resources and access to personnel/skills needed to analyze the data, difficulty in achieving access/partnerships with companies/technologies who would be willing to share data, and lack of direct/valid data (as technology data are typically used as proxies/predictors of STI cases but are not verifiable compared to providing patients with an actual STI test and measuring their results).

Researchers may also be able to collect data on individuals’ social media posts and Internet searches for sexual encounter opportunities. These near-real-time data can be combined with traditional surveillance approaches to better understand regional differences in STI risk in order to inform intervention efforts (Young et al., 2018a,b; Zhang et al., 2019).

Importantly, all of the digital technologies described in this chapter also provide “big data footprints” that researchers and others can use to infer information about people’s attitudes and behaviors. For example, STI and HIV intervention studies occurring on social media sites, such as Facebook, leave digital footprints of information, such as network ties, people’s conversations, and data on topics that are engaging (Pagkas-Bather et al., 2020; Young et al., 2014, 2020). Researchers can analyze this information to better understand people’s STI-related behaviors and improve delivery of future digital outreach and interventions.

IMPLEMENTATION CONSIDERATIONS: COSTS AND FEASIBILITY

The AI-based approaches described in this chapter are included because of the existing support for their ability to be feasible to implement and design, while keeping in mind the resource constraints of state and local health departments. For example, as described above, CDC has already partnered with researchers to use Internet search and social media data to monitor STIs (Young et al., 2018a,b). Similarly, directors of state and local health departments have worked with researchers to develop visualization and mapping tools that leverage AI to identify, map the location, and detect trends in social media posts related to HIV, including perceptions of stigma and views about pre-exposure prophylaxis (Benbow et al., 2020). Publicly available AI-based maps and tools such as this are increasingly being developed, enabling health departments to use AI in their work for little to no cost.

AI approaches also may be cost effective in their ability to inexpensively scale outreach to highly targeted groups. For example, the AI methods being used for highly targeted consumer outreach by advertising companies such as Google could be applied to STI prevention and care. AI methods that leverage people’s data from the technologies described in this chapter can be used to help identify groups in need of STI services. If health departments were to use traditional (non-AI-based) methods, they would typically need to collect resource-intensive data, such as surveys and interviews, each time they target a new population (e.g., young men who have sex with men). A traditional method of outreach (print advertising and venue-based recruitment) also would require extensive resources. AI-based methods could reduce these costs, however, as the same model for outreach can be slightly tweaked after “learning” the differences between the new population attempting to be targeted. This could lead to potentially dramatically reduced costs and also more targeted outreach.

Although AI-based approaches are being designed to be cost effective and feasible for implementation by health departments, as with any approach, costs are still a potential issue. As work on the application of AI to health outreach is still in its infancy, health departments that can afford to hire an individual or team with technical expertise in this area (or collaborate with relevant researchers) will have an advantage in applying these new approaches to their unique needs before tools become more widely accessible for general public health use. More information about potential costs of various approaches is provided in Recommendation 6-1.

IMPLEMENTATION CONSIDERATIONS: ETHICS AND THE RAPIDLY CHANGING ENVIRONMENT

Although a full review of ethical considerations is beyond the scope of this report, ethical considerations need to be addressed when implementing tools and approaches that rely on technologies and their data. A growing amount of research has been conducted around ethical issues relating to technologies in public health research and practice. The general public has been found to be generally supportive of public health researchers and officials using their digital information to improve public health outcomes (Romero and Young, 2021).

Determining the most ethical way to implement the technologies and research approaches described in this chapter, however, is not an easy task. Many questions first need to be addressed, including the following:

- Do companies, individuals, and/or public health departments and researchers bear the ethical responsibility of using technologies in STI prevention and care?

- What role, if any, should public health and safety organizations, including law enforcement, play in using these technologies and gaining access to their data?

- Should policy decisions around implementation of technologies be based on data (which are often outdated) versus future projections?

For example, one challenge in conducting ethical research on technologies relates to the time lag between research and implementation. Because technologies are rapidly changing and their use affects people’s ethical views about them, by the time a study is finished and a policy implemented, public views have often already changed. One possible question is whether it makes sense to determine policy based on research studies if these data are no longer applicable. Another possibility is for policy to be informed by prior data and trends but also based on predictions of what people’s beliefs will be. Yet another possibility is a policy that allows for flexibility and rapid updates to keep up with the changing times and ethical perspectives. Regardless, it remains extremely important to accelerate the rate of ethics and acceptability research on technologies to ensure that health departments are investing in and applying tools that are still relevant and impactful.

The COVID-19 pandemic might serve as a case study. For example, one study surveyed approximately 150 individuals on their preferences and willingness to share digital data (e.g., social media, wearable device/GPS tracking, Internet search, and EHR data) to improve public health just before COVID-19 cases were identified in the United States and related

policies implemented. The team then went back in April 2020, at the peak of the stay-at-home policies, and interviewed 25 participants, half of whom had originally reported being willing and half unwilling to share their data. Not surprisingly, the majority who had originally expressed willingness remained willing. However, surprisingly, approximately 70 percent of participants who had reported being unwilling to share data were now willing if it were used to address the pandemic. All participants generally reported being more willing to share their data if researchers and health officials rather than companies led the work (Romero and Young, 2021). This example illustrates how quickly ethical views can change as a result of external factors, making it essential that researchers and policy makers develop and implement approaches that can account for changing ethical views on technologies to keep up to date with current perspectives.