INTRODUCTION

Structural interventions in public health are interventions that promote population health and/or health equity by altering the structural context within which health is produced (Blankenship et al., 2006). Structural interventions hold great promise for advancing both population health and health equity because they change or influence social, economic, or political environments (the root causes of health and health inequities) in ways that help many people collectively, often even without their knowledge or relying on individual behavior change (CSDH, 2008; Miller et al., 2018b; NASEM, 2017). Structural interventions may promote population health overall or address health inequities in particular (Blankenship et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2019).

While both are important, there is a difference between addressing individuals’ social needs (e.g., providing relief for an immediate housing need) and using structural interventions to address the underlying structural-level social, economic, and political factors that drive these individual social needs, which is the focus of this chapter (Brown et al., 2019; Castrucci and Auerbach, 2019; Green and Zook, 2019; WHO, 2010).

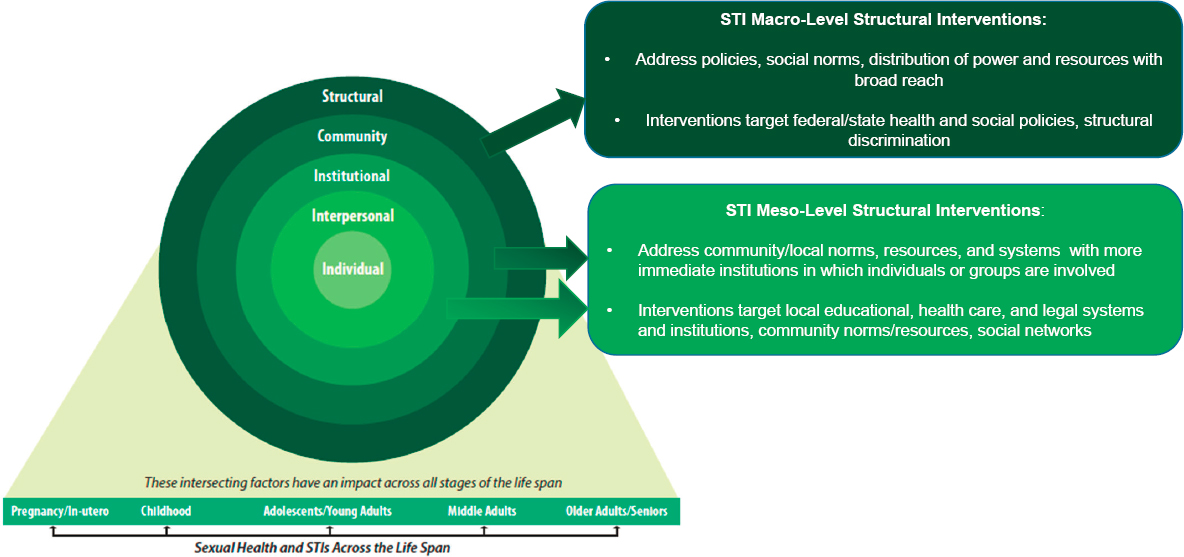

Structural interventions for sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention include policies, programs, practices, and norms that address the structural-level social, economic, and political drivers of STIs and STI inequities. They target social contextual factors at both the macro (e.g., policies, social norms, societal distribution of power and resources) and meso (e.g., social networks, community resources, local health care system) levels (see Figure 9-1). Macro-level structural interventions target factors such as federal and state health and social policies and structural discrimination related to race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity, among other dimensions of social inequality. Meso-level

interventions target factors such as local educational, health care, and legal systems and institutions, community norms and resources, and social networks. As noted, structural interventions can be implemented at multiple levels—including the national, state, local, and institutional levels (Bonell et al., 2006; Rhodes et al., 2005; Sumartojo, 2000). Structural and social behavioral interventions should work together as part of multilevel interventions to address the societal determinants of STIs.

This chapter covers structural interventions that address the high rates of STIs among marginalized social groups in particular and the U.S. population in general at both the macro level—including health and social policies addressing structural inequities—and the meso level—including structural interventions in health and social systems and community mobilization strategies to advance structural change.

STRUCTURAL INTERVENTIONS TO DECREASE STIs IN MARGINALIZED U.S. GROUPS AND REDUCE STI INEQUITIES

The federal government, at least for many Black people, is not widely trusted due to years of racism at all levels, medical and research misconduct like the Tuskegee syphilis cases, and just general lack of trust. To get information out there, it has to come from more trusted sources.

—Participant, lived experience panel1

Root Causes of STI Inequities

As noted earlier in this report, STI incidence and prevalence show pronounced inequities across a number of dimensions of social inequality (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, sexual orientation). Scholars and researchers have observed that health inequities ultimately stem from social, economic, and political contexts and mechanisms (also referred to as social and structural determinants of health [e.g., laws, policies, political practices, social norms]). These inequities are shaped by historical factors and organize the unequal distribution of power, prestige, and other resources among social groups defined in relation to race, ethnicity, gender identity, socioeconomic position, sexual orientation, and immigrant status, among other axes (NASEM, 2017; WHO, 2010).

These structural determinants of health in turn cause and operate through the social determinants of health: housing, education, income,

___________________

1 The committee held virtual information-gathering meetings on September 9 and 14, 2020, to hear from individuals about their experiences with issues related to STIs. Quotes included throughout the report are from individuals who spoke to the committee during these meetings.

wealth, social cohesion and support, psychosocial stressors (including interpersonal discrimination), built environment, and health care, among others. Due to their inequitable distribution and access for social groups, these determinants shape not only population health but also health equity (CSDH, 2008; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010; NASEM, 2017).

In particular, research suggests that structural inequities—societal-level policies, practices, norms, and conditions that undermine the social position of marginalized populations and their access to health-promoting social, economic, political, and health care resources—influence the disproportionate burden of STIs among marginalized racial, ethnic, gender identity, and sexual orientation groups, among others (CSDH, 2008). Although promising, research examining the effect on STI inequities of structural interventions that target structural inequities, however, remains scarce (Brown et al., 2019). This section discusses the small but growing literature that has addressed how structural inequities—structural racism and structural stigma against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) individuals—shape STI inequities, including in the distribution of STIs across sexual orientation identity and racial and ethnic groups, respectively. It also offers insights into the types of structural interventions that might help decrease STI rates in marginalized communities.

Structural Anti-LGBTQ+ Stigma and Sexual Orientation Inequities in STIs

Research indicates that the health of sexual minority (e.g., LGBTQ+) groups can be negatively impacted by structural stigma, defined as “societal-level conditions, cultural norms, and institutional policies and practices that constrain the lives of the stigmatized” (Hatzenbuehler and Link, 2014, p. 2). Structural stigma is often operationalized as discriminatory state-level policies that undermine the health and rights of sexual minorities.

To date, most studies examining structural stigma and health among sexual minorities have focused on mental health outcomes—including psychiatric morbidity (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010), substance use (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2015), and suicide attempts (Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Raifman et al., 2017)—and have shown that sexual minorities living in states with high levels of structural stigma have worse mental health outcomes than their counterparts living in states with low levels of structural stigma. Few studies have examined the association between structural stigma and sexual health. Charlton et al. (2019) found, however, that sexual minority adolescent women living in states with lower compared to higher levels of structural stigma were significantly less likely to have an STI diagnosis, adjusting for individual- and state-level covariates. Stigma was measured

by the density of same-sex partner households, proportion of high schools with gay–straight alliances, a composite variable of five state-level protective policies related to sexual orientation (e.g., employment nondiscrimination policies), and public opinion toward sexual minorities data. This study suggests that changing state-level laws and policies and social norms to be inclusive of sexual minorities may be a structural intervention to mitigate the STI burden of young sexual minority women (Charlton et al., 2019).

Additionally, Oldenburg et al. (2015) found that state-level structural stigma toward sexual minorities (as measured by state-level density of same-sex households, proportion of gay–straight alliances, state laws protecting sexual minorities, and public opinion toward sexual minorities) was associated with lower odds of condomless anal sex and higher odds of post- and pre-exposure prophylaxis awareness and use and of comfort discussing male–male sexual behavior with health care providers among U.S. gay, bisexual, same-gender-loving, and other men who have sex with men (MSM), adjusting for individual- and state-level covariates. Additional research is needed to better ascertain the role of structural stigma in shaping STI inequities related to sexual orientation among both women and men in the United States. This study suggests, however, that structural interventions such as changing state-level laws and policies to prevent discrimination and stigma against sexual minorities and norms to be more favorable toward sexual minorities may help decrease STI rates among MSM (Oldenburg et al., 2015). Along with community-based interventions that seek to decrease anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination and stigma at the institutional/organizational, community, and interpersonal levels, these state-level structural interventions could contribute to a decrease in STIs in LGBTQ+ communities.

In a global context, Pachankis et al. (2015) found that MSM living in European countries with high levels of structural stigma related to sexual orientation (as measured by national laws, policies, and attitudes regarding LGBTQ+ individuals) had higher odds of sexual risk behaviors, unmet HIV prevention needs, HIV testing nonuse, and sexual orientation nondisclosure compared to their counterparts in countries with low levels of structural stigma. The authors also found that MSM migrants in European countries with high levels of anti-LGBTQ+ and anti-immigrant structural stigma (as measured by national laws and policies toward LGBTQ+ populations and national attitudes toward immigrants) had lower levels of human papillomavirus (HPV)-related prevention knowledge, behaviors, and service coverage compared to those in countries with low levels of structural stigma (Pachankis and Bränström, 2018). Similar research could be conducted in the U.S. context by comparing individuals living in states with high versus low levels of structural stigma related to both sexual minorities and immigrants.

Structural Racism and Racial and Ethnic Inequities in STIs

Structural racism refers to “the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination, through mutually reinforcing inequitable systems (in housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, criminal justice, and so on) that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources, which together affect the risk of adverse health outcomes” among populations of color (Bailey et al., 2017). One example is Black individuals living in systematically under-resourced neighborhoods that have high levels of unemployment, homelessness, and incarceration (Bailey et al., 2017). While structural racism has broad population health impacts, historical and contemporary practices and patterns of pervasive discrimination toward Black, Latino/a, and Indigenous people and other individuals of color in health care and social systems both directly and indirectly shape STI outcomes in marginalized racial and ethnic groups. Of note, historical and contemporary factors related to the health care system that shape access to and use of STI testing and treatment services among marginalized populations have historically included coercive experimental gynecological surgery on enslaved Black women, the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study on Black men, unethical medical research on the bodies of Black people, such as Henrietta Lacks (whose biopsied cells were used without consent to create the HeLa cell line, which has been used in research for more than 50 years and remains the oldest and most commonly used cell line in existence), and forced and coerced sterilization of Black, Latina, and Indigenous women throughout the 20th and 21st centuries (Roberts, 2016)—all of which promote medical mistrust and the delay and avoidance of STI-related care (IOM, 2003).

Moreover, discrimination in other social systems, including housing, education, employment, criminal justice, and media, indirectly shape racial and ethnic STI inequities in the United States by undermining the access of marginalized groups to health-promoting resources (e.g., income), increasing exposure to STIs (e.g., mass incarceration, racial residential segregation), and promoting negative stereotypes (e.g., media representations) about their behavior, including sexual behavior, that undermine equitable treatment in society in general and the health care system in particular (Adimora and Schoenbach, 2005; Bailey et al., 2017; Friedman et al., 2009; Krieger, 2003). For example, in a 2019 ecological study, researchers found a statistically significant positive association between the median number of Black individuals killed by police (racialized police brutality, a form of structural racism) and syphilis and gonorrhea rates among Black residents across 75 large U.S. metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) (Ibragimov et al., 2019c). Furthermore, scientists found a statistically significant positive association between residential segregation of

Black individuals, a dimension of structural racism, and gonorrhea rates across 277 U.S. MSAs (Pugsley et al., 2013).

Similarly, one study found a statistically significant positive association between racial residential segregation and newly diagnosed HIV cases among Black heterosexual individuals across 95 large U.S. MSAs and evidence that this association may be mediated by Black/white socioeconomic inequality (Ibragimov et al., 2019a). This research suggests that developing, testing, and implementing structural interventions that address the effect of structural racism (e.g., mass incarceration, racial residential segregation, racialized policing) may decrease STIs among communities of color and reduce racial and ethnic inequities in STIs (Adimora and Auerbach, 2010; Blankenship et al., 2000, 2006; Ibragimov et al., 2019a).

Additionally, very few interventions addressing the effect of intermediary social determinants of health influenced by structural racism (e.g., housing, employment, access to health care, incarceration) on racial and ethnic STI inequities have been developed and tested or evaluated using experimental or quasi-experimental research methods. One example is a randomized controlled trial Towe et al. (2019) focused on homeless individuals living with HIV/AIDS to see if rapid rehousing would improve housing and HIV viral suppression more than standard housing assistance. Those in the rapid rehousing group were placed faster, more likely to be placed, and twice as likely to achieve or maintain suppression. Another recent example is the Adolescent Trials Network study (Work to Prevent—ATN 151), which aims to test whether an employment intervention, including working with employers, can reduce HIV/STI transmission behaviors among sexual and gender minority adolescents of color (Hill et al., 2020). In 2020, the Community Preventive Services Task Force concluded that that economic evidence shows that benefits exceed the intervention cost for Housing First programs in the United States and that these programs showed health benefits and reduced health services use (Peng et al., 2020). For clients living with HIV infection, Housing First programs reduced homelessness by 37 percent, viral load by 22 percent, and mortality by 37 percent (Peng et al., 2020). Clinical trial networks, however, rarely support interventions such as these.

Looking to the Future

Public health researchers and research funders need to conduct and support the development, evaluation, implementation, and dissemination of new or existing interventions that address both the upstream structural and intermediary social determinants of racial and ethnic inequities in STIs at the federal, state, county, city, or neighborhood level by engaging

government agencies, advocates, community-based organizations, community organizers, activists, and members, and other key stakeholders (Adimora and Auerbach, 2010; Blankenship et al., 2000, 2006; Boyer et al., 2016; Valdiserri and Holtgrave, 2019). For example, Los Angeles County health officials recently attributed the rise in STI rates to structural racism and vowed to evaluate and address its effects in partnership with communities (Karlamangla, 2018). Public health researchers could help to evaluate such efforts in partnership with government officials and community organizations and, in turn, contribute to the evidence base on structural interventions and racial and ethnic inequities in STIs.

Furthermore, in a recent editorial, Fullilove (2020) urged STI researchers to stop focusing on race and instead move toward examining the “proxy factors” that shape racial and ethnic inequities in STIs and designing programs, policies, and other interventions to address them. This recommendation is aligned with the committee’s call to examine and address how structural racism, as a root cause, shapes racial and ethnic STI inequities (see Recommendation 9-1).

Several public health and health care organizations (e.g., American Public Health Association, American Medical Association), states, cities, and counties, academic institutions, and scholars have declared racism a public health crisis (AMA, 2020; APHA, 2020, n.d.; ASTHO, 2020; Dirr, 2019; Jones, 2018; Thulin, 2020; Vestal, 2020; Walters, 2020; Yearby et al., 2020). Such declarations should seek to raise public awareness and discourse about how structural racism affects population health outcomes and health inequities, including STI rates and inequities. These declarations also need to determine key societal actions, inform the allocation of public funds, and lead to committing other social, economic, and political resources to address structural racism and other social inequities and their effect on the health of marginalized racial and ethnic groups and the U.S. population as a whole.

MACRO-LEVEL STRUCTURAL INTERVENTIONS TO DECREASE STIs IN THE U.S. POPULATION OVERALL

Health Policies

Research suggests that federal and state health policies, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) (including federal and state provisions, such as the optional Medicaid expansion, summarized in Chapters 4 and 10) and state HPV vaccination policies, sexuality education policies, and minor STI testing consent laws, may influence the distribution of STIs across and within U.S. social groups—by increasing access to prevention education and information and testing and treatment

services. Moreover, several states have implemented HIV exposure criminalization laws, with the stated purpose of preventing further HIV infections by requiring that people living with HIV disclose their status to sexual partners (Harsono et al., 2017). In addition to the harm caused to individuals with HIV who are charged or prosecuted under these laws, they also increase stigma toward people living with HIV and populations with a high burden of HIV (e.g., MSM). Research examining the effect of such laws on HIV/STI-related sexual behaviors provides little evidence that they deter persons from engaging in sex without disclosing HIV status or of any reduction in HIV transmission or increase in HIV/STI prevention behaviors (Harsono et al., 2017).

The ACA did much to expand access to comprehensive and more affordable coverage for health services, including STI testing and treatment. The Medicaid expansion, subsidies for lower-income individuals to purchase individual policies, and a requirement that all employer plans offer coverage for dependent adult children up to age 26 resulted in an important structural change for those most affected by STIs, particularly young adults and low-income individuals.

Another aspect of the ACA that could produce structural change are provisions that require coverage of preventive services that have been given a high rating by the United States Preventive Services Task Force and those that are recommended for children by Bright Futures and for women by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (discussed in Chapter 10). Eliminating cost sharing can remove a financial barrier to access, and the broad reach of the requirement across essentially all private health plans can create a standard of access to critical preventive services. A review of the research on the impact of the ACA preventive services coverage (Chait and Glied, 2018) identified studies that have documented increases in preventive visits, diabetes screening, glucose testing, and HIV screening among low-income adults who were newly eligible for Medicaid (Simon et al., 2017). One study analyzed the impact of the dependent coverage expansion for adults aged 18–25 and found a 3–5 percent increase in the share receiving preventive services, although the study did not focus specifically on sexual and reproductive health care services.

The committee could not, however, identify any empirical study that directly examined the association among the ACA, state HPV vaccination policies, state minor STI testing consent laws, and STIs in the U.S. population overall or in disproportionately affected social groups in particular, at the individual or societal levels. Nonetheless, one study found that federal and state ACA provisions would result in greater HIV testing, which could decrease HIV cases and also suggests that the ACA may have resulted in higher levels of STI testing and lower STI rates (Wagner et al.,

2014). Furthermore, several studies found a positive association between ACA provisions that went into effect soon after enactment, but before the law’s major coverage expansions in 2014 (coverage for extended dependency and of preventive services with no cost sharing) and HPV vaccination among young U.S. women overall (Corriero et al., 2018; Lipton and Decker, 2015) and lesbian and bisexual women in particular (Agénor et al., 2019).

Several studies examined the association between state HPV vaccination policies and HPV vaccine uptake. Many of these studies found no association among U.S. adolescents, potentially because of the lenient opt-out provisions (Cuff et al., 2016; Perkins et al., 2016; Pierre-Victor et al., 2017). One study found that the Rhode Island HPV vaccination school entry mandate, however, was associated with an increase in vaccination initiation among adolescent boys but not girls (Thompson et al., 2018). Another study identified a set of state health policies that was consistently associated with vaccine uptake among U.S. adolescents: Medicaid expansion, policies permitting HPV vaccination in pharmacies, school entry requirements, and classroom sex education (Roberts et al., 2018).

Additionally, one study examined the association between state sexuality education policies for high school students and STIs (Hogben et al., 2010), finding that states with no mandates for abstinence had the lowest mean STI (gonorrhea and chlamydia) rates in the overall U.S. population and among U.S. adolescents in particular, whereas states with sexuality education policies emphasizing abstinence had the highest mean STI rates; the burden of STIs in states with mandates to cover but not emphasize abstinence fell in between (Hogben et al., 2010).

More research is urgently needed on the role of health policies in STI rates and prevention, especially among groups who are disproportionately affected by STIs. Empirically guided research is limited on the relationship between federal and state health policies (federal and state ACA coverage and benefit provisions, state HPV vaccination policies, state sexuality education policies, and state minor STI testing consent laws), alone and in combination, and STIs in the U.S. population overall and in disproportionately affected social groups. Additionally, health policy research should strive to identify the potential mechanisms that drive the association between health policies and STI impact such that interventions could also target these mechanisms to decrease the overall effect of STIs and STI inequities.

Social Policies

Federal and state social policies shape individuals’ and communities’ access to health care, social, and economic resources, which influence

population health and health inequities (McLeroy et al., 1988; NASEM, 2017; WHO, 2010). Research that focuses on the effects of social policies on STIs in the U.S. population overall is scarce (CSDH, 2008). Nonetheless, Ibragimov et al. (2019b) found that MSAs in states with a $1 higher minimum wage had lower rates of syphilis (19.7 percent) and gonorrhea (8.5 percent) compared to MSAs in states with a $1 lower minimum wage among U.S. women, suggesting that state-level policies that increase the minimum wage may help decrease STIs among women overall.

Moreover, federal and state policies and laws that decriminalize commercial sex work may help decrease STIs for both commercial sex workers and the U.S. population overall. For example, Cameron et al. found that criminalizing sex work in a district in East Java, Indonesia, increased STIs among female sex workers and potentially their clients, especially by decreasing condom access and use, and decriminalization had the potential to improve population STI outcomes (Cameron et al., 2020). In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 1900–2018 quantitative and qualitative research from around the world, Platt et al. (2018) found that criminalizing sex work with aggressive policing of sex workers was associated with higher levels of HIV and STI risk and condomless sex with clients (Platt et al., 2018). Additionally, Cunningham and Shah (2014) found that, when Rhode Island decriminalized indoor commercial sex work in 2003, rape and gonorrhea among women decreased by 31 and 39 percent, respectively, from 2004 to 2009. However, given the observational nature of these studies, more research is needed.

MESO-LEVEL STRUCTURAL INTERVENTIONS TO DECREASE OVERALL STI RATES AND STI INEQUITIES

Structural Interventions in the Health Care System

Several studies have examined STI-related structural interventions in health care settings (Taylor et al., 2016) and identified several clinic-based interventions that effectively promote STI screening and thus may help decrease STIs in the U.S. population, including the strategic placement of specimen collection materials within clinics, automatic screening as part of routine health care visits, modifying electronic health records (EHRs) to remind health care providers to screen all patients, patient testing reminders, providing testing services at no or low cost, rapid express clinic functionality, and hiring staff positions dedicated to screening activities (Taylor et al., 2016). Automatic STI screening, EHR reminders, and patient reminders led to the highest improvement at the lowest cost. Noninvasive specimen collection methods, such as self-collection or even home testing, likewise might facilitate recommended STI screening (see Chapter

7). Dedicated STI staff was associated with the highest improvement in screening at the highest cost (Taylor et al., 2016). Further research is needed to identify whether, in addition to facilitating STI screening in the U.S. population overall, these clinic-based structural interventions also help mitigate STI inequities related to race, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, and sexual orientation among other social factors.

Across multiple health care financing and delivery models, various stakeholders have sought innovative approaches to incentivize wellness and maintenance of health rather than solely focusing on remedying illness or providing treatment. These include Medicaid managed care, health maintenance organizations, sexual health clinics that focus on self-efficacy for prevention, and targeted services for key populations, such as adolescents and LGBTQ+ communities. All are suitable for persons living in households and alone, but health care services for institutionalized populations cannot be neglected. These populations include residents of correctional and penal institutions, persons living on military bases or camps, school or college dormitories, and health care facilities, both short and long term, including hospitals. Such institutions are theoretically even more easily influenced toward sexual health interventions, given the accessibility of the target populations.

Structural Interventions in the Education System

Although the committee could not identify any study that explicitly examined STI-related structural interventions in educational settings, limited research has investigated such interventions in the context of HIV prevention in schools (Rotheram-Borus, 2000) and showed that school-based health centers and making condoms available are the types of interventions that facilitate access to HIV prevention and testing services and decrease HIV risk behaviors among youth, including increasing condom use during sexual encounters (Rotheram-Borus, 2000). (See Chapter 8 for an overview of school-based sexual education interventions.)

Structural Interventions in the Criminal Legal System

In the United States, we have about 12 million incarcerations a year. About 11 million of them happen in county jails, so these are places where people come in and go out very quickly. Unless you are part of a big public health agency like we were in New York City, it can be difficult to implement some types of screening. Chlamydia screening is one where you absolutely need [it] if you care about the public health. The impediment is almost exclusively cost because it is quick now, and it’s easy to do. When I go around the country looking at correctional health settings, I rarely find a county jail that’s doing

this, but they could be. Certainly, if they wanted to address all of the morbidity and mortality that is related to this, they could expand, as we did in New York City, to include a systematic test coming into the correctional facility.

—Participant, lived experience panel

No studies that explicitly examine STI-related structural interventions in relation to the criminal legal system were identified; several challenges and opportunities were noted (see Chapter 3 for background on individuals who are criminal legal system involved and STIs, including STI screening). Challenges for prevention and treatment in these institutions are many, including financing, short stays in many jails and juvenile detention centers, lack of sexual health training among some health providers, suboptimal diagnostic capacities, and stigma that may influence policy makers to direct health resources elsewhere (NCCHC, 2020). Nonetheless, incarceration or detention represents an important window of opportunity for intervention. For example, though the Federal Bureau of Prisons guidelines are explicit as to screening strategies for incarcerated persons, considerable variability can be seen in the degree of success for state prisons, local jails, and juvenile detention programs to mount comparable programs. Furthermore, solicitations for contractors to provide health care services in prisons, jails, immigration detention, or juvenile detention entities rarely mandate routine STI screening and treatment as a core requirement. Modern trends of privatizing prisons and health services may work against deploying STI screening programs.

Although correctional policies often do not permit specific structural interventions in carceral settings, such as condom provision and needle-exchange initiatives, this does not mean that such programs are ineffective. In fact, previous empirical research suggests that these interventions are feasible, do not threaten security, and lead to greater use of condoms and sterile injection equipment in prison settings (Belenko et al., 2009; Donaldson et al., 2013; Underhill et al., 2014). Policy changes that integrate structural interventions, psychosocial programs, and drug treatment could reduce the impact of incarceration and criminal justice involvement on individuals and communities at risk for HIV and other STIs (Underhill et al., 2014).

Structural Interventions in Congregate Care Systems

Individuals living in congregate care systems may have varying degrees of freedom of movement, depending on the living arrangements and their independence and capacities. Such persons include adolescents and children in transient foster care or in group homes (St Lawrence et al., 1994). Too often, the congregate care or detention settings themselves

may increase STI risk due to child sexual abuse (Beal et al., 2018). Adults may live in supervised halfway houses, nursing homes, intermediate care facilities for people with intellectual disabilities, assisted living facilities, homeless shelters, or residential treatment settings. Persons of all ages may live in communities that may focus on mental health or substance use and provide opportunities for sexual health interventions. There are also “safe homes” and shelters for persons experiencing abuse for whom a return to the home could be dangerous due to intimate partner violence or other abuse.

Programs built as alternatives to prison or for formerly trafficked youth and adults may have clients in a variety of housing arrangements but typically can serve as an effective conduit to prevention and care opportunities (Marshall et al., 2009). Parolees or prisoners reentering society also may find themselves in some of these congregate care settings (Levanon Seligson et al., 2017).

Structural interventions for congregate care and STI prevention and control have rarely been examined. Because former foster youth are at increased risk of housing instability and STIs during the transitional period following foster care, Lim et al. (2017) used administrative records in New York City, New York, to assess whether a supportive housing program was effective at improving their housing stability and STI rates. The program was positively associated with a pattern of stable housing and negatively associated with diagnosed STI rates. The authors note that these positive impacts highlight the program’s importance for this population. Other opportunities for youth in foster care or transitioning out include offering testing at intake, altering the consent process to allow them to consent to confidential testing, and mandating that foster care parents receive sexual health education (Willard et al., 2015). Congregate care settings have too infrequently taken the opportunity to intervene in sexual health and STI prevention.

COMMUNITY MOBILIZATION FOR STRUCTURAL CHANGE RELATED TO STIs AND HIV

As described earlier in this chapter, achieving structural change related to STIs is critical to support and sustain extant and forthcoming interventions (Chutuape et al., 2014), and community mobilization and community coalitions are an important mechanism through which to enable this change (Chutuape et al., 2010). Community mobilization interventions require getting community members together for programs that address defined issues and include collaboration between and empowerment of community members and grassroots organizations with shared interests (Ziff et al., 2006). This was seen in the earliest responses to HIV,

led by gay activists and community-based organizations that educated people, raised awareness, and advocated for funds and better government responses, as well as in the People with AIDS self-empowerment movement, which used the Denver Principles (People with AIDS Advisory Committee, 1983) to highlight that those affected by HIV need to be respected as people and be actively involved in shaping responses to the HIV epidemic. Such community participation underscores the importance of empowering communities to advance their own health and aligns with the principles of health equity (Valdiserri and Holtgrave, 2019).

This section summarizes the current knowledge on community mobilization for structural change for prevention and risk reduction leveraging literature on HIV, notes the gaps of this kind of research and substantive findings on STIs, and discusses the implications of the existing HIV research that can be applied to STIs.

Approaches and Strategies

A recent STI-focused example is the STI Regional Response Coalition (STIRR), which aims to promote healthy sexual behaviors and reduce STI incidence in the St. Louis community through education, collaboration, and evidence-based practice. The faculty at the Division of Infectious Disease and the Institute for Public Health at Washington University and key stakeholders organized STIRR in early 2015. STIRR is largely a provider-led coalition, with participants from state, city, and county health departments; academic medical centers; hospital emergency departments; urgent care centers; community health centers (i.e., federally qualified health centers); community-based organizations; and private providers. A provisional goal of STIRR is to work toward a regional management plan for STIs in the St. Louis area by using evidence-based medicine, expert opinion, and national guidelines (STIRR, n.d.).

The majority of publications on community mobilization for structural change related to the HIV continuum of care in the United States, however, are focused on Connect to Protect (C2P). C2P is a national multisite intervention located in 14 cities across the United States (inclusive of Puerto Rico) that focuses on working with diverse community coalitions to alter policies, practices, programs, and environmental influences associated with HIV among youth (Ziff et al., 2006). Its specific communities reflect a diverse array of urban populations and include youth subpopulations at highest risk for HIV infection, such as Black and Latina heterosexual adolescent and young adult women and young MSM. C2P was created and implemented by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) in 2001, and coalition sites were initially located in urban areas with high

rates of youth STIs and of youth at risk for HIV transmission and infection (Ellen et al., 2015). The C2P coalitions are based on the community empowerment framework, build on “AIDS-competent communities” as a concept (collaborative support for achieving objectives across the community) (Boyer et al., 2016), and focus on intermediate, or meso-level, structural determinants (Ziff et al., 2006). Coalition members include decision makers, local volunteer stakeholders, and content experts who effectively worked together to identify HIV-related structural changes (Boyer et al., 2016). They were involved with entities that served Black and Latino/a youth, LGBTQ+ youth of color, and youth with additional needs and concerns (e.g., sexual abuse, homelessness, etc.), and some were youth themselves (Miller et al., 2018a).

Approaches for community mobilization for structural change around HIV include initiatives that adjust the intricate networks of services and organizations connected to the HIV continuum of care (Boyer et al., 2016). The most promising strategies capitalize on community mobilization efforts that create synergy between various community actors (Wagner et al., 2014). Overall success documented at the C2P sites was partially due to their ability to form meaningful, collaborative relationships (Ziff et al., 2006). In this vein, multiple studies highlight the need for multi-sectoral support and inclusion of community members and organizations for community mobilization to heighten the import of HIV prevention. A multi-sectoral, multi-partnered approach is appropriate, given that various determinants contribute to health outcomes and health inequities and increase success in achieving structural change objectives (Chutuape et al., 2010, 2014; NASEM, 2017; Valdiserri and Holtgrave, 2019). Researchers also note that structural changes need engagement from multiple stakeholders to reach the decision makers who hold the power to enact structural change (Chutuape et al., 2014). Other coalitions formed a linkage-to-care subcommittee that included members representing various health-related fields, sectors, and systems (e.g., health care agencies, criminal justice system, school-based health centers, health departments, crisis centers, AIDS education and training centers, public schools, Planned Parenthood, etc.) (Boyer et al., 2016).

Additional approaches and strategies the C2P coalitions employed include the following:

- developing stakeholder relationships and building partnerships, particularly with those most impacted, and publicly honoring key stakeholders (Chutuape et al., 2010; Harper et al., 2012);

- empowering the community through improved relationships with those in power (e.g., law enforcement) (Pachankis and Bränström, 2018);

- gaining community buy-in through meetings, surveys, public awareness building, education, and community events (Chutuape et al., 2010; Harper et al., 2012);

- using a systematic planning process from the Community Toolbox with a logic model and strategic planning materials to help them develop localized structural changes to maximize relevance and community acceptance (Chutuape et al., 2010; Ellen et al., 2015);

- implementing a root cause analysis process and embedding it within the C2P strategic planning framework in order to think structurally (Boyer et al., 2016; Reed et al., 2014);

- building coalition members’ capacity (Chutuape et al., 2010; Harper et al., 2012);

- gathering diverse supporters and identifying change agents (Chutuape et al., 2010);

- employing flexibility and patience;

- cross-sharing information (Boyer et al., 2016) and offering technical assistance (Chutuape et al., 2010);

- using the Anderson and May model for HIV infection transmission dynamics (Ziff et al., 2006);

- collecting data from youth about HIV risk behaviors (Harper et al., 2012); and

- employing social network data collection and intervention (Pagkas-Bather et al., 2020).

Another community mobilization example is the HIV Prevention Community Planning effort: since 1994, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has required that 65 health department grantees that receive funding for HIV prevention interventions engage in a community planning process to involve affected communities in local prevention decision making, among other goals (CDC, 2012; Johnson-Masotti et al., 2000). Local community planning groups are charged with identifying and prioritizing unmet HIV prevention needs in their communities. They also prioritize prevention interventions designed to address those needs. Their recommendations form the basis for the local health department’s request for HIV prevention funding from CDC (Johnson-Masotti et al., 2000). Some lessons learned from this effort include the following:

- Rules and bylaws are needed to insure inclusion and proper deliberation about data, and community planning groups need to be organized to carry out their tasks and decide how to delegate work within the group (Jenkins et al., 2005).

- A coherent organization is essential to group members’ being able to use data to adequately understand local needs (Jenkins et al., 2005).

- A basic tenet of HIV planning is parity, inclusion, and representation. “Parity is the ability of HIV planning group members to equally participate and carry out planning tasks or duties in the planning process” (CDC, 2012, p. 11). CDC notes that to achieve parity, opportunities for orientation and skills building should be made available to representatives to participate in the planning process and have an equal voice in voting and other decision-making activities. “Inclusion is the meaningful involvement of members in the process with an active role in making decisions” (CDC, 2012, p. 11).

- The planning process should ensure that interagency services are considered and linked to HIV planning, as appropriate (CDC, 2012).

Finally, another example from the HIV field is the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program Planning Councils and Planning Bodies funded through HRSA (Planning CHATT, 2018). These councils determine the needs of those who are identified as high risk for HIV and those already infected, establish priorities for prevention and treatment services, and make recommendations to best meet the prioritized needs in their state. No other federal health or human services program has a legislatively required planning body that is the decision maker about how funds will be used, has such defined membership composition, and requires such a high level of consumer participation (at least 33 percent) (Planning CHATT, 2018).

Domains, Indicators, and Structural Change Objectives

There are several important components of community mobilization to lead to structural change. Lippman et al. (2013) searched Western theory to identify six elements that are needed to improve health outcomes or behaviors (community consciousness, leadership, social cohesion, shared concern, collective actions, and organizational networks/structures) and concluded that to be successful, HIV intervention designs should focus on addressing these elements, in addition to their designated content-specific outcomes. This work contributes to community mobilization approaches, particularly those for structural change, by establishing domains that can guide and bolster intentional planning, strategy, and evaluation.

Chutuape et al. (2014) identified community mobilization indicators, including (1) action steps, (2) key actors, (3) number of new key actors, (4) sectors represented by key actors, and (5) time taken for objective

completion, that facilitated assessing how successful the C2P coalitions were in achieving structural change objectives (e.g., amending a law allowing health professionals or representatives to offer HIV preventive counseling or perform HIV/STD testing in the clinic and community to youth under 21 without parental consent). These objectives can be used to classify the coalitions as more or less successful. It took coalitions a median of 3 action steps, 12 key actors, 6 new key actors, and 7 months to complete objectives. The research indicates that structural change objectives do not necessarily take more time to complete than individual change objectives and that it is beneficial for coalitions to bundle related objectives or have multiple objectives that target the same goal for their processes (Chutuape et al., 2014; Willard et al., 2015).

C2P achieved multiple structural change objectives, including the following:

- organizational policies to improve understanding of LGBTQ+ culture and youth (Chutuape et al., 2014);

- policies on HIV resource allocation and data collection (Chutuape et al., 2014);

- linkages between organizations to expand youth access to HIV services (CDC, 2012), such as referrals, mental health services, voluntary counseling and testing, increased HIV/STIs diagnoses (Ziff et al., 2006), and extended health facility hours (Ellen et al., 2015);

- novel or improved youth development programs and youth-friendly primary care (Ziff et al., 2006);

- adaptation and implementation of the CDC community-level program from the Compendium of HIV Prevention Interventions (Ziff et al., 2006);

- adoption of the Ryan White Program income eligibility policy change (Boyer et al., 2016);

- alteration of physical structures to discourage risky behavior (Ellen et al., 2015) and better social venues to promote more healthful lifestyles (Ziff et al., 2006); and

- removal of mandatory parental/guardian consent (Ellen et al., 2015).

Assessing the Impact of Community Mobilization Efforts

The C2P studies all stem from a single longitudinal intervention. There are, however, varying analyses or subquestions related to their development, implementation, and evaluation. For example, Reed et al. (2014) discussed the usefulness of community coalition action theory

(CCAT), which is one of the primary frameworks demonstrating the factors and processes contributing to the formation, maintenance, and institutionalization of coalitions, as well as their outcomes. The researchers used CCAT in the analysis to assess how community context impacted the development of objectives. Knowing the relationship between context and coalitions’ achievements can be useful when trying to make structural change in order to get a sense of feasibility and the difficulty of enacting it and determine which types of change will be successful (Reed et al., 2014). Building on this, any structural-level interventions, especially at a large scale, need to be grounded in strong theory in community mobilization, have a central administrative infrastructure, and support and encourage the expertise of and collaboration between sites and communities (Ziff et al., 2006).

Ellen et al. (2015) surveyed the coalitions’ target populations, including 2,392 participants in their analysis, and found some suggested associations between an individual’s exposure to structural change interventions in their community and the individual’s self-reported HIV risk–related behaviors, but these were not statistically significant. This reflects the difficulty in evaluating structural change interventions that span community sectors and target different social ecological levels (Ellen et al., 2015). Miller et al. (2018a) surveyed 2,284 adolescents to assess the impact of the C2P community mobilization efforts and the plausibility of the C2P logic model by identifying the effects and links of expected HIV stigma, risk and protective behaviors, and community support. They found that adolescents reported few HIV-risky sexual encounters during their lifetime if they felt they lived in caring communities and that community satisfaction improved over time, which aligns with how structural change increases a community’s capability. The coalitions were not successful, however, in lowering anticipated HIV stigma or upsetting the relationship between risk behavior and HIV stigma, indicating a need to intervene on stigma over long periods (Miller et al., 2018a).

Reed et al. (2014) suggested that C2P coalitions that were categorized as “above average” increased community resources, built on current efforts for quick wins, and prevented effort duplication. They also partnered with other organizations working on upstream issues, such as homelessness, adolescent parenthood, and impoverishment. The findings suggest benefits in aligning coalition objectives with community priorities that might seem more pressing than HIV prevention and aligning with political priorities as a part of relationship building. Researchers also observed that coalition groups that described their political environments as conservative and mistrustful of collaboration or had communities with strong faith-based traditions achieved fewer objectives and were not ranked as “above average” (Reed et al., 2014). Paradoxically, many of the

best-practice approaches in the literature for achieving structural change are apt to receive community pushback (e.g., comprehensive sex education) and political resistance (e.g., syringe services programs) and may require many resources, which reduces feasibility and requires coalition members to spend a disproportionate amount of time on them compared to other objectives.

Gaps in Community Mobilization Research Around STIs

The committee did not identify research that specifically focuses on community mobilization for structural change around non-HIV STIs specifically. In the global context, Cornish et al. (2014) performed a systematic review and noted that a 2014 substudy of the Avahan program by Ramesh et al. (2010) showed decreased prevalence of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia among female sex workers, although not significantly. The Frontiers Prevention Projects in Ecuador and Andhra Pradesh, India, showed lower likelihoods of herpes simplex virus 2 and syphilis among MSM and female sex workers (Gutiérrez et al., 2010, 2013). In addition, Lippman et al. (2012) on the Encontros project in Brazil found nonsignificantly reduced odds of gonorrhea or chlamydia for sex workers exposed to the intervention compared with those who were not. Overall, existing data suggest that community mobilization efforts are associated with reduced STI rates among sex workers. Cornish et al. (2014) indicate that among youth and the general community, evidence is limited that community mobilization successfully reduces STIs, with success only among Project Accept in Thailand and the Stepping Stones Program in South Africa.

Accordingly, inferences will have to be made when considering how to enable structural change for STIs. Studies that mention both HIV and STIs offer little to no discussion about how community mobilization for structural change might impact HIV risk and STI risk differently. While STIs can increase a person’s risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV, studies on the impact of community mobilization for structural change around STIs alone are critical given the varying levels of stigma, discrimination, care access, etc. and that some STIs are more easily treatable with medication (e.g., syphilis, chlamydia, and some strains of gonorrhea), whereas others are lifelong conditions to be managed (e.g., herpes simplex virus).

Community Mobilization Research Limitations

No current standardized definition of community mobilization exists, with a wide range of interventions considered to fall under that umbrella, from structural interventions led by the community to community

sensitization and education (Kuhlmann et al., 2014). Additionally, in many efforts and studies, community mobilization itself is also thought of as a structural intervention, when it is actually a way to empower communities and change power dynamics (Cornish et al., 2014). This makes it challenging to compare findings across studies that use different definitions and indicators, which can impact how efforts plan their processes based on existing research.

Most U.S.-based research on community mobilization for structural change centers on the C2P coalitions, which focused on adolescents and young adults. The global research explored by Cornish et al. (2014) indicates that for youth populations, the research is mostly inconclusive, due to many nonsignificant findings, on how community mobilization impacts HIV and STI risk. This indicates the need for more community mobilization efforts and evaluation of those efforts around structural change for HIV and other STIs. It follows that evidence-based examples of structural interventions around HIV prevention are limited and, by extension, so are those for STIs (Willard et al., 2015).

Beyond this, few existing studies show coalitions’ ability to bring about structural change around HIV (Chutuape et al., 2010). If structural changes are created, studies remain lacking that assess how this affects individual-level behavioral changes (Ellen et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2018a). For studies that have been able to measure structural- and individual-level variables, researchers have noted that these measurements may not be precise enough to detect change and that they do not assess change in risk behavior over time. Many structural interventions target root causes that take a long time to modify given their more distal locations on the causal pathway (Ellen et al., 2015). Additionally, little attention has been paid to structural barriers and the social determinants that constitute the underlying root causes of barriers to the HIV continuum of care, such as transportation access, unemployment, health insurance policies, impoverishment and food insecurity, and homelessness (Boyer et al., 2016).

Many of the prior reviews of HIV prevention programs focus on heterosexual youth (Harper et al., 2012), leaving out LGTBQ+ youth and queer communities of all ages. Structural prevention interventions as a whole are underused in the United States, particularly for reducing HIV in adolescents (Ziff et al., 2006), and are rarely evaluated for interventions focused on adolescents and young adults (Boyer et al., 2016). Overall, youth are understudied in research exploring how structural community features promote HIV risk and exposure, even though they are quite dependent on their community surroundings (Miller et al., 2018b). Existing community mobilization efforts for adolescent health have been limited because of the focus on access to substances, implementation of standardized programs, and low number of rigorous evaluations. They have

not been widely used to help reduce the rates of HIV infection among youth given that sexual activity is regulated differently from alcohol and other substances (Ziff et al., 2006).

Implications of HIV Literature for STIs

Future considerations for future community mobilization from this review around HIV and STIs include the following:

- HIV risk–related factors that serve as analysis outcomes include areas that overlap with STI considerations, such as the number of sexual partners in the previous 3 months, partner characteristics, frequency of condom use and use at last encounter, current and past-year STI status and health care and treatment, and past-year HIV testing (Ellen et al., 2015).

- Evaluation of interventions may be difficult given the need to enable structural change by targeting various levels of the Social Ecological model, and it requires multi-sectoral partnerships and approaches.

- There are age, gender, sexuality, race, and ethnicity differences and an STI prevalence that is different from HIV.

- The tool referenced in Willard et al. (2015) could be adapted to assist communities in identifying the necessary structural changes for combating STIs at the local level.

- Stigma is still a major driving factor when it comes to accessing HIV services, but stigma factors for STIs may differ.

- CCAT can be effective for grounding community mobilization for structural change related to STIs.

- Ecological assessments can be used to create objectives that take into account the demographic trends, features, and shifts of their local context (Reed et al., 2014).

- The six community mobilization domains defined by Lippman et al. (2013) for HIV prevention could be applied to structural interventions for HIV and STIs, in the United States and globally. However, the time it takes for structural change objectives to be put in place and impact upstream structural-level changes needs to be a consideration when choosing which structural change objectives to focus on.

- Communities are dynamic and ever changing and adapting, so any mobilization needs frequent checks on what is the community and how is it evolving.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATION

Although empirical research in the area of STI-specific structural interventions is limited, studies indicate that macro-level structural interventions (e.g., federal and state health and social policies) and the factors they target (e.g., access to health insurance and health care, anti-LGBTQ+ structural stigma, structural racism, other structural inequities), meso-level structural interventions in health care and social systems and institutions, and community mobilization efforts seeking structural change influence STI rates in both the U.S. population in general and marginalized U.S. groups in particular. First, to continue building this small but growing body of work, additional research is needed that examines how various structural factors and their downstream social determinants influence STI rates and prevention in the U.S. population overall and in marginalized groups. In particular, given that most existing studies have focused on the role of structural discrimination related to sexual orientation identity in shaping STI outcomes, additional research is urgently needed that examines how structural racism, transphobia, and xenophobia singly and jointly shape STI rates and prevention in the U.S. population overall and among marginalized groups using rigorous study designs that address both broad population patterns (e.g., difference-indifference analysis) and the lived experiences of underserved populations (e.g., mixed-methods study designs). Additionally, efforts are needed to develop, test, implement, disseminate, and scale up policies, programs, and other interventions that target upstream structural factors and their social determinants at multiple levels of influence to prevent STIs overall and STI inequities.

Based on its review of the evidence on structural interventions, the committee provides the following conclusions and recommendation to address structural racism and other structural inequities that hinder STI prevention and control:

Conclusion 9-1: Observational, policy evaluation, and intervention research on the structural (e.g., equitable/discriminatory federal and state health and social policies) and social (e.g., housing, income, health care) determinants of STI inequities related to race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender/gender identity are lacking, and need to be a focus moving forward for public health researchers and funders.

Conclusion 9-2: Examining and addressing the structural determinants of STIs and STI inequities will require bold vision, long-term commitment, multidisciplinary, intersectoral, and interagency collaboration, dedicated funding from NIH, CDC, HRSA, and private foundations and funders,

steadfast political will at all levels of government, and sustained community engagement and mobilization. Due to their focus on addressing root causes and their downstream social determinants, these efforts stand to have the greatest impact on preventing STIs and STI inequities in the United States. Although achieving this goal will take time, it is imperative to start now in order to prevent STIs and STI inequities for future generations.

Conclusion 9-3: Structural inequities related to sexual orientation, gender identity, race and ethnicity, and national origin, among others, are pervasive, increasing STI risk, perpetuating stigma, and undermining access to STI prevention and treatment among marginalized populations. These inequities need to be addressed in order for efficacious biomedical and social behavioral interventions to more effectively mitigate risk and disease for these populations.

Recommendation 9-1: The Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) should acknowledge structural racism and other forms of structural inequities as root causes of sexually transmitted infection (STI) outcomes and inequities and as threats to sexual health.

HHS should lead a whole-of-government response that engages all relevant federal departments and agencies to develop a coordinated approach to reduce negative STI outcomes and address inequities in the U.S. population by promoting sexual health and eliminating structural inequities that are barriers to STI prevention, testing, and treatment among marginalized groups.

In mounting this response, the Secretary should:

- consult broadly with affected communities and critical stakeholders to conduct a national landscape analysis that assesses social and structural barriers that prevent access to STI services. The focus should be on identifying communities with high morbidity and limited access to affordable and desirable STI prevention and care services and resources in order to develop a national holistic plan for ongoing monitoring of the national STI infrastructure and STI burden, including interrelated structural and social determinants of health inequities;

- establish a priority research agenda, including a data-collection strategy that organizes data on STI outcomes and their structural and social determinants among marginalized populations;

- strengthen partnerships with, funding for, and technical assistance to state and local health departments and community-based organizations;

- foster greater collaboration across health and human services agencies; and

- report regularly to the public on progress for addressing STI outcomes and inequities.

This effort needs to be inclusive of community and clinical services and educational efforts and should seek to bolster integration with relevant other initiatives and programs, such as Title X, Health Centers, and HIV prevention and care programs. Realizing this recommendation will require political will and dedicated funding for delivering affordable, accessible, and acceptable STI services to affected communities and addressing the structural and social determinants of STIs and STI inequities. This recommendation should be responsive to and implemented in collaboration with local communities based on their needs, perspectives, and priorities.

REFERENCES

Adimora, A. A., and J. D. Auerbach. 2010. Structural interventions for HIV prevention in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 55:S132-S135.

Adimora, A. A., and V. J. Schoenbach. 2005. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. Journal of Infectious Diseases 191(Suppl 1):S115-S122.

Agénor, M., G. Murchison, J. Chen, D. Bowen, M. Rosenthal, S. Haneuse, and S. Austin. 2019. Impact of the Affordable Care Act on human papillomavirus vaccination initiation among lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual U.S. women. Health Services Research 55.

AMA (American Medical Association). 2020. AMA: Racism is a threat to public health. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/health-equity/ama-racism-threat-public-health (accessed November 19, 2020).

APHA (American Public Health Association). 2020. Racism is an ongoing public health crisis that needs our attention now. https://www.apha.org/news-and-media/news-releases/apha-news-releases/2020/racism-is-a-public-health-crisis (accessed November 1, 2020).

APHA. n.d. Declarations of racism as a public health issue. https://www.apha.org/topics-and-issues/health-equity/racism-and-health/racism-declarations (accessed October 30, 2020).

ASTHO (Association of State and Territorial Health Officials). 2020. State legislation to declare racism a public health crisis and address institutional racism. https://www.astho.org/StatePublicHealth/State-Legislation-to-Declare-Racism-a-Public-Health-Crisis-and-Address-Institutional-Racism/08-12-20 (accessed November 1, 2020).

Bailey, Z. D., N. Krieger, M. Agenor, J. Graves, N. Linos, and M. T. Bassett. 2017. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 389(10077):1453-1463.

Beal, S. J., K. Nause, I. Crosby, and M. V. Greiner. 2018. Understanding health risks for adolescents in protective custody. Journal of Applied Research on Children 9(1).

Belenko, S., R. Dembo, M. Rollie, K. Childs, and C. Salvatore. 2009. Detecting, preventing, and treating sexually transmitted diseases among adolescent arrestees: An unmet public health need. American Journal of Public Health 99(6):1032-1041.

Blankenship, K. M., S. J. Bray, and M. H. Merson. 2000. Structural interventions in public health. AIDS 14:S11-S21.

Blankenship, K. M., S. R. Friedman, S. Dworkin, and J. E. Mantell. 2006. Structural interventions: Concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. Journal of Urban Health 83(1):59-72.

Bonell, C., J. Hargreaves, V. Strange, P. Pronyk, and J. Porter. 2006. Should structural interventions be evaluated using RCTs? The case of HIV prevention. Social Science & Medicine 63(5):1135-1142.

Boyer, C. B., B. C. Walker, K. S. Chutuape, J. Roy, J. D. Fortenberry, and the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. 2016. Creating systems of change to support goals for HIV continuum of care: The role of community coalitions to reduce structural barriers for adolescents and young adults. Journal of HIV/AIDS and Social Services 15(2):158-179.

Brown, A. F., G. X. Ma, J. Miranda, E. Eng, D. Castille, T. Brockie, P. Jones, C. O. Airhihenbuwa, T. Farhat, L. Zhu, and C. Trinh-Shevrin. 2019. Structural interventions to reduce and eliminate health disparities. American Journal of Public Health 109(Suppl 1):S72-S78.

Cameron, L., J. Seager, and M. Shah. 2020. Crimes against morality: Unintended consequences of criminalizing sex work (working paper). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Castrucci, B., and J. Auerbach. 2019. Meeting individual social needs falls short of addressing social determinants of health. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190115.234942/full (accessed November 7, 2019).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2012. HIV planning guidance. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/p/cdc-hiv-planning-guidance.pdf (accessed February 18, 2021).

Chait, N., and S. Glied. 2018. Promoting prevention under the Affordable Care Act. Annual Review of Public Health 39:507-524.

Charlton, B. M., M. L. Hatzenbuehler, H. J. Jun, V. Sarda, A. R. Gordon, J. R. G. Raifman, and S. B. Austin. 2019. Structural stigma and sexual orientation-related reproductive health disparities in a longitudinal cohort study of female adolescents. Journal of Adolescence 74:183-187.

Chutuape, K. S., N. Willard, K. Sanchez, D. M. Straub, T. N. Ochoa, K. Howell, C. Rivera, I. Ramos, and J. M. Ellen. 2010. Mobilizing communities around HIV prevention for youth: How three coalitions applied key strategies to bring about structural changes. AIDS Education Prevention 22(1):15-27.

Chutuape, K. S., A. Z. Muyeed, N. Willard, L. Greenberg, and J. M. Ellen. 2014. Adding to the HIV prevention portfolio—the achievement of structural changes by 13 Connect to Protect coalitions. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice 5(2):1-8.

Cornish, F., J. Priego-Hernandez, C. Campbell, G. Mburu, and S. McLean. 2014. The impact of community mobilisation on HIV prevention in middle and low income countries: A systematic review and critique. AIDS and Behavior 18(11):2110-2134.

Corriero, R., J. L. Gay, S. W. Robb, and E. W. Stowe. 2018. Human papillomavirus vaccination uptake before and after the Affordable Care Act: Variation according to insurance status, race, and education (NHANES 2006-2014). Journal of Pediatric Adolescent Gynecology 31(1):23-27.

CSDH (Commission on Social Determinants of Health). 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Final report of the commission on social determinants of health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Cuff, R. D., T. Buchanan, E. Pelkofski, J. Korte, S. P. Modesitt, and J. Y. Pierce. 2016. Rates of human papillomavirus vaccine uptake amongst girls five years after introduction of statewide mandate in Virginia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 214(6):752. e751-752.e756.

Cunningham, S., and M. Shah. 2014. Decriminalizing indoor prostitution: Implications for sexual violence and public health. NBER working paper no. 20281. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Dirr, A. 2019. Milwaukee county executive signs resolution declaring racism a public health crisis. https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/local/milwaukee/2019/05/20/abele-signsresolution-declaring-racism-public-health-crisis/3741809002 (accessed November 1, 2020).

Donaldson, A. A., J. Burns, C. P. Bradshaw, J. M. Ellen, and J. Maehr. 2013. Screening juvenile justice-involved females for sexually transmitted infection: A pilot intervention for urban females in community supervision. Journal of Correctional Health Care 19(4):258-268.

Ellen, J. M., L. Greenberg, N. Willard, J. Korelitz, B. G. Kapogiannis, D. Monte, C. B. Boyer, G. W. Harper, L. M. Henry-Reid, L. B. Friedman, and R. Gonin. 2015. Evaluation of the effect of human immunodeficiency virus–related structural interventions: The Connect to Protect project. JAMA Pediatrics 169(3):256-263.

Friedman, S. R., H. L. Cooper, and A. H. Osborne. 2009. Structural and social contexts of HIV risk among African Americans. American Journal of Public Health 99(6):1002-1008.

Fullilove, R. E. I. 2020. Race and sexually transmitted diseases… again? Sexually Transmitted Diseases 47(11):724-725.

Green, K., and M. Zook. 2019. When talking about social determinants, precision matters. Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20191025.776011/full (accessed November 7, 2019).

Gutiérrez, J. P., S. McPherson, A. Fakoya, A. Matheou, and S. M. Bertozzi. 2010. Community-based prevention leads to an increase in condom use and a reduction in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among men who have sex with men (MSM) and female sex workers (FSW): The Frontiers Prevention Project (FPP) evaluation results. BMC Public Health 10:497.

Gutiérrez, J. P., E. E. Atienzo, S. M. Bertozzi, and S. McPherson. 2013. Effects of the Frontiers Prevention Project in Ecuador on sexual behaviours and sexually transmitted infections amongst men who have sex with men and female sex workers: Challenges on evaluating complex interventions. Journal of Development Effectiveness 5(2):158-177.

Harper, G. W., N. Willard, J. M. Ellen, and the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. 2012. Connect to Protect®: Utilizing community mobilization and structural change to prevent HIV infection among youth. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 40(2):81-86.

Harsono, D., C. L. Galletly, E. O’Keefe, and Z. Lazzarini. 2017. Criminalization of HIV exposure: A review of empirical studies in the United States. AIDS and Behavior 21(1):27-50.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L. 2011. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics 127(5):896-903.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., and B. G. Link. 2014. Introduction to the special issue on structural stigma and health. Social Science & Medicine 103:1-6.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., K. A. McLaughlin, K. M. Keyes, and D. S. Hasin. 2010. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health 100(3):452-459.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., H. J. Jun, H. L. Corliss, and S. Bryn Austin. 2015. Structural stigma and sexual orientation disparities in adolescent drug use. Addictive Behaviors 46:14-18.

Hill, B. J., D. N. Motley, K. Rosentel, A. VandeVusse, R. Garofalo, L. M. Kuhns, M. D. Kipke, S. Reisner, B. Rupp, R. West Goolsby, M. McCumber, L. Renshaw, and J. A. Schneider. 2020. Work2prevent, an employment intervention program as HIV prevention for young men who have sex with men and transgender youth of color (Phase 3): Protocol for a single-arm community-based trial to assess feasibility and acceptability in a real-world setting. JMIR Research Protocols 9(9):e18051.

Hogben, M., H. Chesson, and S. O. Aral. 2010. Sexuality education policies and sexually transmitted disease rates in the United States of America. International Journal of STD & AIDS 21(4):293-297.

Ibragimov, U., S. Beane, A. A. Adimora, S. R. Friedman, L. Williams, B. Tempalski, R. Stall, G. Wingood, H. I. Hall, A. S. Johnson, and H. L. F. Cooper. 2019a. Relationship of racial residential segregation to newly diagnosed cases of HIV among Black heterosexuals in U.S. metropolitan areas, 2008-2015. Journal of Urban Health 96(6):856-867.

Ibragimov, U., S. Beane, S. R. Friedman, K. Komro, A. A. Adimora, J. K. Edwards, L. D. Williams, B. Tempalski, M. D. Livingston, R. D. Stall, G. M. Wingood, and H. L. F. Cooper. 2019b. States with higher minimum wages have lower STI rates among women: Results of an ecological study of 66 U.S. metropolitan areas, 2003-2015. PLoS One 14(10):e0223579.

Ibragimov, U., S. Beane, S. R. Friedman, J. C. Smith, B. Tempalski, L. Williams, A. A. Adimora, G. M. Wingood, S. McKetta, R. D. Stall, and H. L. Cooper. 2019c. Police killings of Black people and rates of sexually transmitted infections: A cross-sectional analysis of 75 large U.S. metropolitan areas, 2016. Sexually Transmitted Infections 96(6):429-431.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2003. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jenkins, R. A., A. R. Averbach, A. Robbins, K. Cranston, H. Amaro, A. C. Morrill, S. M. Blake, J. A. Logan, K. Batchelor, A. C. Freeman, and J. W. Carey. 2005. Improving the use of data for HIV prevention decision making: Lessons learned. AIDS and Behavior 9(Suppl 2):S87-S99.

Johnson-Masotti, A. P., S. D. Pinkerton, D. R. Holtgrave, R. O. Valdiserri, and M. Willingham. 2000. Decision-making in HIV prevention community planning: An integrative review. Journal of Community Health 25(2):95-112.

Jones, C. P. 2018. Toward the science and practice of anti-racism: Launching a national campaign against racism. Ethnicity & Disease 28(Suppl 1):231-234.

Karlamangla, S. 2018. STDs in L.A. County are skyrocketing. Officials think racism and stigma may be to blame. https://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-ln-std-stigma20180507-htmlstory.html (accessed November 2, 2020).

Krieger, N. 2003. Does racism harm health? Did child abuse exist before 1962? On explicit questions, critical science, and current controversies: An ecosocial perspective. American Journal of Public Health 93(2):194-199.

Kuhlmann, A. S., C. Galavotti, P. Hastings, P. Narayanan, and N. Saggurti. 2014. Investing in communities: Evaluating the added value of community mobilization on HIV prevention outcomes among FSWS in India. AIDS and Behavior 18(4):752-766.

Levanon Seligson, A., F. M. Parvez, S. Lim, T. Singh, M. Mavinkurve, T. G. Harris, and B. D. Kerker. 2017. Public health and vulnerable populations: Morbidity and mortality among people ever incarcerated in New York City jails, 2001 to 2005. Journal of Correctional Health Care 23(4):421-436.

Lim, S., T. P. Singh, and R. C. Gwynn. 2017. Impact of a supportive housing program on housing stability and sexually transmitted infections among young adults in New York City who were aging out of foster care. American Journal of Epidemiology 186(3):297-304.

Lippman, S. A., M. Chinaglia, A. A. Donini, J. Diaz, A. Reingold, and D. L. Kerrigan. 2012. Findings from Encontros: A multilevel STI/HIV intervention to increase condom use, reduce STI, and change the social environment among sex workers in Brazil. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 39(3):209-216.