INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a major global public health challenge that can lead to serious reproductive, physical, and mental health issues with devastating sequelae. These can be especially deleterious for people who were assigned female at birth (AFAB) and children. STIs also can amplify the risk for transmitting and acquiring HIV (see Chapter 5 for more information). STI rates continue to increase globally, with more than 1 million STIs acquired daily (Rowley et al., 2019). The U.S. rates are among the highest in high-income economies (NCSD, 2018; OECD/EU, 2016) and have continued to grow over several decades, seemingly unabated by public health interventions, especially for the most common and reportable STIs: chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis. Preventing future infections is critical to the nation’s health.

To protect the public from the harmful impacts of STIs, it is important to understand the epidemiology of STIs, the strengths and limitations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) case reporting surveillance system, and these infections’ root causes (including the individual-, interpersonal-, institutional-, community-, and structural-level factors). This chapter therefore includes three major sections: (1) interpretation of surveillance data, (2) STI patterns in the United States, and (3) drivers of those STI outcomes, patterns, and inequities, including the multiple levels of risk and protective factors. The section on STI drivers is particularly important because surveillance data in isolation can lead to placing blame on the individual without taking into account the multilevel societal factors that influence individual behaviors, circumstances, and, ultimately, outcomes. As highlighted in the report’s modified social-ecological model (see Chapter 1), a complex interplay among individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and structural factors shapes STI prevention, control, and treatment. This chapter’s section on drivers of STIs and STI inequities in the United States is expanded on further in Chapter 3. Box 2-1 highlights key findings from the chapter.

INTERPRETATION OF SURVEILLANCE DATA

STI surveillance is key to understanding the magnitude of STIs in the United States and in subpopulations that are most affected. The ability of federal authorities to monitor STI trends and provide the public with actionable national data depends on local health authorities providing case reports and other information to states, pursuant to state law. States aggregate these data, analyze them, and use them to guide state policy. Furthermore, states voluntarily share such aggregated data, without individual identifiers, with CDC. After quality assurance, nationwide surveillance information is then disseminated via the CDC STD surveillance

reports, which are published annually and describe the epidemiology of four nationally notifiable infections (chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid). A weakness of the current reporting system is the substantial variation in STI monitoring capacity across states and local jurisdictions (NAPA, 2018), which hinders the ability to make direct comparisons from place to place in order to identify emerging issues in a timely manner and respond. While states have primary responsibility for public health, including data collection and reporting, this report recommends actions to leverage federal financial support to states to achieve greater timeliness, uniformity, and quality of data reported by all states to CDC. CDC STD surveillance reports also compile information from published literature on human papillomavirus (HPV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), and Trichomonas vaginalis. CDC’s number of reported cases is derived from several sources: (1) notifiable disease reporting from state and local STI programs; (2) projects that monitor STI positivity and prevalence in various settings, such as the National Job Training Program, the STD Surveillance Network, and the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project;

and (3) national surveys and other data-collection systems operated by federal and private organizations (CDC, 2019d). Census data, rather than overall numbers of people tested, determine the total size of the relevant population. Case rates are derived by taking the number of cases reported from these different sources and dividing by the population from the most recent Census information.

CDC STI surveillance data give only a partial picture of unfolding trends and need to be interpreted with caution for several reasons: (1) they are ecological and highly influenced by screening rates, which are not universal and are highly variable, so the case rates might not reflect the true population-based prevalence rate; (2) only a few STIs are surveilled, so less is known about those that are not nationally reportable; and (3) the data are limited to a few sociodemographic variables, such as age, race, sex, and geography, which often limit subgroup analyses. While the case rates do provide a crude understanding of the epidemiology and trends of these STIs, they are susceptible to variations and fluctuations in testing rates, the absence of universal screening recommendations, lag time in case reporting, underreporting, and repeat testing (see the section later in this chapter on coinfection and reinfection). Furthermore, the Census is performed only every 10 years and may underestimate certain populations. Finally, delays in publishing the CDC STD surveillance report (generally 9 months after the end of the calendar year) render it ineffective for responding to outbreaks in real time. Currently, local jurisdictions need to request CDC assistance during outbreaks, with no standardized early warning system for outbreaks. Population-based surveys, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), and subpopulation-based surveys, such as the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, also provide essential data for tracking STI rates and behaviors. See Appendix A of the CDC Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2018 report for more information on nationally notifiable STI surveillance and other sources of surveillance data (CDC, 2019d). See also Chapter 4 for information about funding of STI surveillance.

Increases in testing rates over time may increase STI case rates and lead to spurious conclusions. Since 2001, chlamydia screening rates for women who are privately insured have approximately doubled, while the rate for those receiving Medicaid has increased 17 percent (NCQA, n.d.). However, data from the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set show that, in 2018, only about half of women recommended to be screened for chlamydia were actually screened (NCQA, n.d.). While overall chlamydia case reporting demonstrates an increase in case rates over the past 20 years, prevalence estimates from NHANES actually show a reduction. Data reported between 1999 and 2002 showed a chlamydia

prevalence of 2.2 percent (range 1.8–2.8 percent) (Datta et al., 2007); data from 2007 to 2012 show it decreased to 1.7 percent (range 1.4–2.0 percent) (Torrone et al., 2014). NHANES data also demonstrate that racial and ethnic disparities have persisted over the years (Datta et al., 2012). These data are susceptible to error, however, as the sample sizes are small (Miller and Siripong, 2013). The conflict between these estimates creates confusion; more accurate, nuanced, and timely surveillance data are needed.

Women are not screened as recommended for myriad reasons, including lack of access to health care and, for women who do have access, low uptake by providers. For men, the lack of general screening recommendations leads to fewer cases detected. For all people, the asymptomatic nature of many of the STIs contributes to fewer people being screened and tested. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, many municipalities reported decreased numbers of STIs, presumably due to decreased access to testing services and less health care–seeking behavior (de Miguel Buckley et al., 2020; Hoffman, 2020; Latini et al., 2021; Nagendra et al., 2020). Therefore, case rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis, for example, illustrate only diagnosed and reported infections and may distort or fail to reflect true infection rates. Other STIs of public health significance, such as HPV and HSV, are not nationally notifiable, so their data are not routinely reported. Understanding the significance of other highly prevalent STIs, such as Trichomonas vaginalis and Mycoplasma genitalium, is increasing, but has not resulted in screening recommendations or reporting requirements; yet, data are mounting regarding the importance of these infections for reproductive health (Lis et al., 2015), perinatal morbidity (Silver et al., 2014), and amplified HIV transmission (Kissinger and Adamski, 2013).

Traditionally, surveillance systems have captured some demographic information about cases to understand the population at risk for the four most common reportable STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HIV), but this information has been limited to sex, race and ethnicity, and age; quality surveillance data are missing for many sexual minority groups and transgender and other gender diverse populations. For these reasons and those explained above, case-based surveillance is not sufficient for an effective response. To address some of these shortcomings, CDC also uses prevalence data from NHANES and the STD Surveillance Network (a sentinel surveillance project in 11 jurisdictions). More detailed information is collected in other national initiatives, too, such as the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Other potential sources of relevant data include the National Survey of Family Growth and the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. As with the CDC surveillance data, each

source has value and limitations. For example, the STD Surveillance Network only examines factors related to gonorrhea and underrepresents the South, where a large portion of STIs occur. NHANES no longer tests for syphilis or gonorrhea,1 and NHANES data are more accurate when combined for multi-year periods because prevalence estimates and sample sizes for any given cycle are relatively small, especially for demographic subgroup analysis (Torrone et al., 2013). NHANES data are not available at the regional or state levels, which could obscure regional differences of geographically clustered STIs (Torrone et al., 2013). Finally, the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System does not include out-of-school youth (e.g., homeless, incarcerated, dropped out); these subgroups could have high STI rates. (For more detailed information about these data sources’ strengths and limitations, see Datta et al., 2012; Miller and Siripong, 2013; NASEM, 2019a,b; Pierannunzi et al., 2013; Rietmeijer et al., 2009; Torrone et al., 2013; Underwood et al., 2020.) Additionally, large databases, such as hospital discharge databases, claims data, and Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project databases, can help to provide insight into sequelae for STIs, such as neonatal herpes and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Other databases could also potentially be used for STI surveillance as more electronic health record information becomes available. The fragmented efforts described in this section highlight the need to modernize STI surveillance (NAPA, 2018, 2019). See Chapter 12 for conclusions and recommendations on improving STI surveillance.

Detailed surveillance data are important for STI program staff, but are often inaccessible to laypersons. Developing other information formats is critically important for the public to understand important trends and emerging issues, track progress toward achieving STI reduction goals, and hold policy makers accountable for results. The federal Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative has generated important resources that enable the public to understand key indicators and track progress toward achieving HIV milestones.2 This type of effort offers a model for increasing public commitment to improving STI outcomes by clearly communicating crucial goals in a way that easily enables individuals to monitor progress. Simple dashboards (a short, easy-to-understand visual tool for monitoring progress) can establish standard measures that can be applied to federal, state, local, or clinical outcomes.

___________________

1 Personal communication with Hillard Weinstock, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available by request from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Public Access Records Office (PARO@nas.edu).

2 See https://ahead.hiv.gov (accessed November 15, 2020).

PATTERNS OF STIs IN THE UNITED STATES

U.S.-reported case rates of the three most common reportable STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis) have been increasing over the past decades. Since 2000, the overall case rate of chlamydia has doubled, gonorrhea has increased nearly 1.4-fold, and primary and secondary syphilis is up 5-fold (CDC, 2019d). In 2021, CDC estimated the incidence and prevalence of eight STIs to understand more fully the U.S. STI burden (Kreisel et al., 2021). This model showed an estimated 26.2 million incident and 67.6 million prevalent STI infections in 2018. Chlamydia, trichomoniasis, genital herpes, and HPV accounted for approximately 93 and 98 percent of all incident and prevalent infections, respectively. This analysis indicates that more than 20 percent of the U.S. population had an STI at some point in 2018. Young people aged 15–24 are disproportionately affected, as more than 45 percent of estimated incident infections were in that age group (Kreisel et al., 2021).

Furthermore, STIs cost U.S. taxpayers billions of dollars. According to recent estimates, the total lifetime direct medical cost of incident STIs is $15.9 billion (2019 dollars), with the majority due to HIV ($13.7 billion) (Chesson et al., 2021). Of the remainder, $1 billion is attributed to gonorrhea and chlamydia combined; three-quarters of the remaining cost burden is due to STIs in women. Among young people aged 15–24, the total cost of incident STIs (including HIV) is $4.2 billion (Chesson et al., 2021). The human costs of STIs (e.g., anxiety, infertility, relationship strife or disruption, childhood disabilities) are far more difficult to quantify (see Chapter 4).

The sections below describe the epidemiology of the three common, reportable STIs and of other STIs, including HIV, HPV, HSV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), T. vaginalis, M. genitalium, chancroid, Lymphogranuloma venereum, and a related dysbiosis, bacterial vaginosis (BV). Although STI rates have increased across all populations in the United States, marginalized groups—youth; women; members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) community; and Black, Latino/a, American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN), and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander people—continue to experience a disproportionate share of STI cases in the United States.

Chlamydia

Increasing chlamydial infections are in large part fueling the U.S. STI crisis. Chlamydia is the most common notifiable condition (CDC, 2019d). This is not a new trend, as chlamydia has made up the largest proportion of STIs reported to CDC at least since 1994. Complications of undetected chlamydia infections, such as PID, can lead to devastating health

consequences later in life. PID is a major preventable cause of chronic pelvic pain and tubal scarring, leading to infertility and ectopic pregnancy. Untreated chlamydia in pregnancy can result in infant pneumonia and ophthalmia neonatorum, leading to blindness. Undetected infections in people assigned male at birth (AMAB) generally have less severe sequelae, but can lead to epididymitis and contribute to such people’s role as a reservoir. In both sexes, chlamydia infections can amplify HIV acquisition and transmission. See Appendix A for more information.

In 2018, there were 1.7 million chlamydia infections reported to CDC, corresponding to 539.9 cases per 100,000; this is a 20 percent increase from 2014 (CDC, 2019d). From 2000 to 2018, reported rates increased in men and women, in all racial and ethnic groups, and in all geographic regions (CDC, 2019d). Reported cases are likely only a fraction of the actual number of infections. A CDC modeling study estimated 4.0 million incident chlamydia infections in those aged 15–39 in 2018 (Kreisel et al., 2021), suggesting that the true infection rate may be more than double.

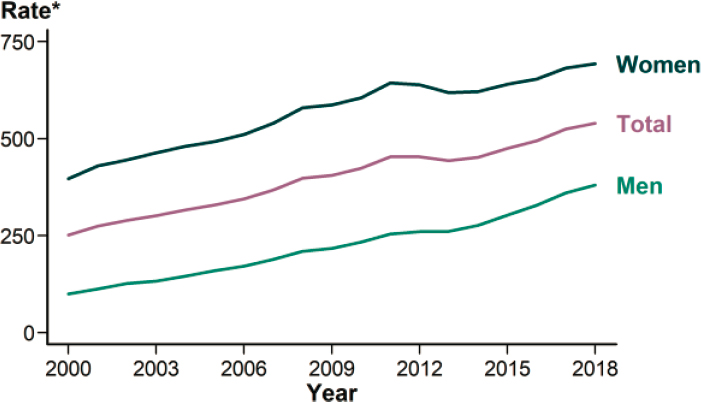

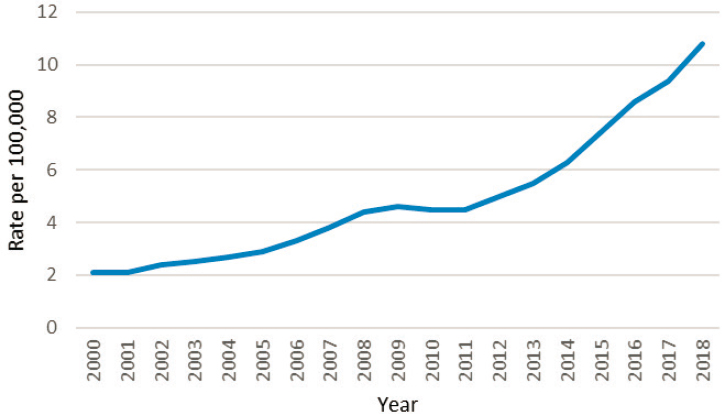

Rates of reported chlamydia cases among men and women increased from 2000 to 2018, with a slight unexplained dip from 2011 to 2013 (CDC, 2019d) (see Figure 2-1). Case rates in CDC surveillance reports are always higher among women than men, due to both screening differences and biological reasons. CDC recommends screening sexually active women under the age of 25 but screening only older women at increased risk of infection (e.g., new sex partner, more than one sex partner) or men in

* Per 100,000.

SOURCE: CDC, 2019d.

high-prevalence settings (CDC, 2015). The narrow age range was determined to maximize efficiency in detection but may result in undiagnosed infections, which serve as a reservoir of infection and sustain the epidemic. Population-based 2007–2012 NHANES data show a significantly higher prevalence in women compared to men in the 14–39 age group (2.0 percent versus 1.4 percent, respectively) (Torrone et al., 2014). CDC prevalence assessments support these NHANES data, estimating 1.3 million prevalent infections in women and 1.1 million in men in 2018 (Kreisel et al., 2021).

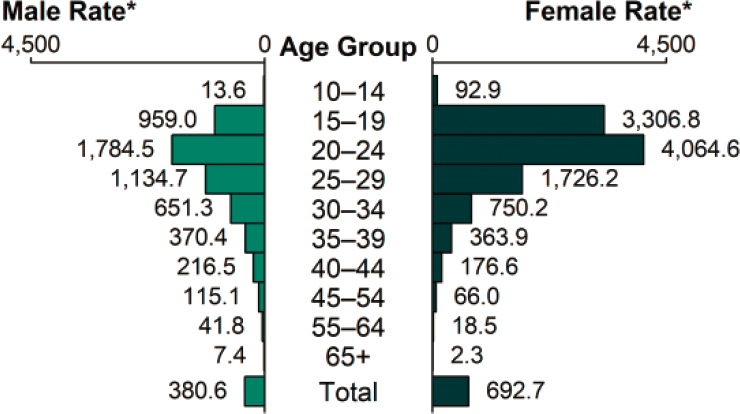

Chlamydia disproportionately affects youth (see Figure 2-2); two-thirds of all reported cases and estimated incident and prevalent infections were among persons aged 15–24 (CDC, 2019d; Kreisel et al., 2021). The precipitous drop in infection after age 24 may be the result of behavioral and biological factors, including a tendency for older persons to be more likely to be in longer-term relationships and cumulative partial immunity to reinfection (Batteiger et al., 2010; Lantagne and Furman, 2017; Meier and Allen, 2009).

All racial and ethnic groups experienced increases in reported chlamydia cases from 2014 to 2018 (CDC, 2019d). Racial and ethnic minorities, however, are disproportionately burdened; the highest rates in 2018 were among Black, AI/AN, and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander individuals. Compared with white people, rates of reported cases were 5.6, 3.7, and 3.3 times higher in these groups, respectively. Similarly, the

* Per 100,000.

SOURCE: CDC, 2019d.

rate of reported cases among Hispanic or Latino/a people was 1.9 times that of white people. In contrast, the rate among persons of Asian descent was 0.6 times that among white people (CDC, 2019d).

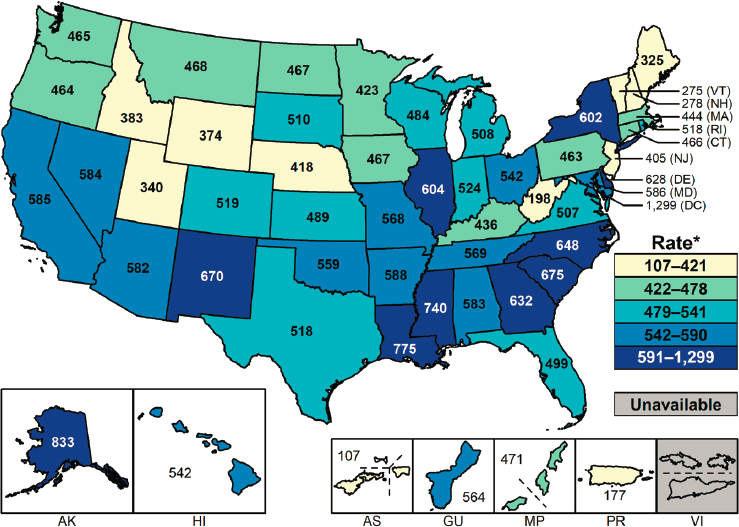

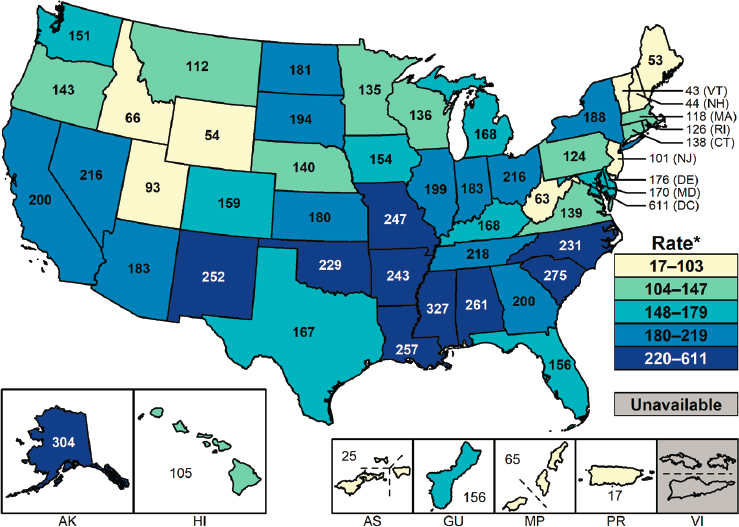

While rates have been increasing in all areas, in 2018, they were highest in the South and West, with a remarkably high rate in Alaska (see Figure 2-3). There are geographic clusters of chlamydia, as there are with gonorrhea and syphilis. For example, 44 percent of the reported cases came from just 70 of more than 3,000 counties; about two-thirds of those counties and independent cities were in the South and West (CDC, 2019d).

Gonorrhea

Second only to chlamydia, gonorrhea is a common notifiable STI (CDC, 2019d). Much like chlamydia, its sequelae are problematic: PID, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility for people AFAB, blindness in children delivered by people who are infected, epididymitis in people AMAB, and increased risk of HIV infection in all people (see Appendix A for more information).

* Per 100,000.

SOURCE: CDC, 2019d.

There were 583,405 cases reported to CDC in 2018, corresponding to a rate of 179.1 cases per 100,000 (CDC, 2019d). The rate in 2018 was a 63 percent increase from that in 2014, and an almost 83 percent increase from 2009, when reported cases were at a historic low (CDC, 2019d). Figure 2-4 shows 2000–2018 rates per 100,000. As with chlamydia, reported gonorrhea rates increased in men and women, in all racial and ethnic groups, and in all geographic regions from 2017 to 2018. Furthermore, a troublesome trend has emerged, as drug-resistant strains of gonorrhea are spreading worldwide. More than half of all infections in the United States in 2018 were estimated to be resistant to at least one antibiotic (CDC, 2019a,d). CDC estimated that there were 1.6 million incident and 209,000 prevalent gonorrhea infections in 2018 (Kreisel et al., 2021).

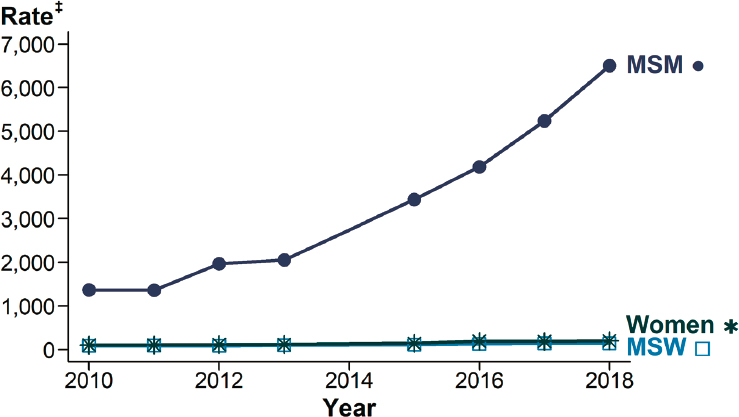

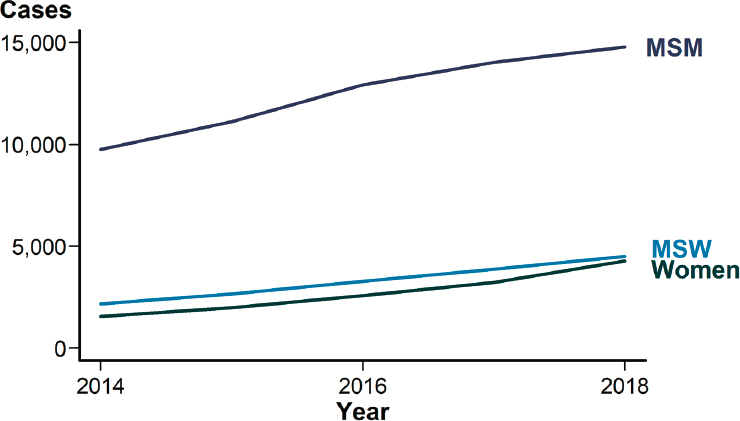

The age and sex distribution is somewhat different from that of chlamydia, because gonorrhea tends to be more symptomatic in people AMAB than chlamydia is. CDC also recommends screening all sexually active women under the age of 25 but not general screening of asymptomatic men (CDC, 2015). Surveillance data demonstrate that the age range at highest risk is 20–24 and that men have higher rates (CDC, 2019d). From 2014 to 2018, the male rate increased by almost 80 percent compared to approximately 45 percent for women (CDC, 2019d). Surveillance data demonstrate that the rapid increase since 2014 is likely due to increased infection among gay and bisexual men compared to men who have sex with women (MSW) and women (see Figure 2-5). Additional contributors may be improved case identification among gay, bisexual, and other

SOURCE: Data from CDC, n.d.-a.

NOTES: MSM = gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men; MSW = men who have sex with women only. Sites include Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York City, San Francisco, Washington State, and California (excluding San Francisco).

‡ Per 100,000.

* Estimates based on interviews among a random sample of reported cases of gonorrhea (n = 21,417); cases weighted for analysis. Data not available for 2014; 2013–2015 trend interpolated; trend lines overlap for MSW and women in this figure.

SOURCE: CDC, 2019d.

men who have sex with men (MSM) through more extragenital screening (CDC, 2019d).

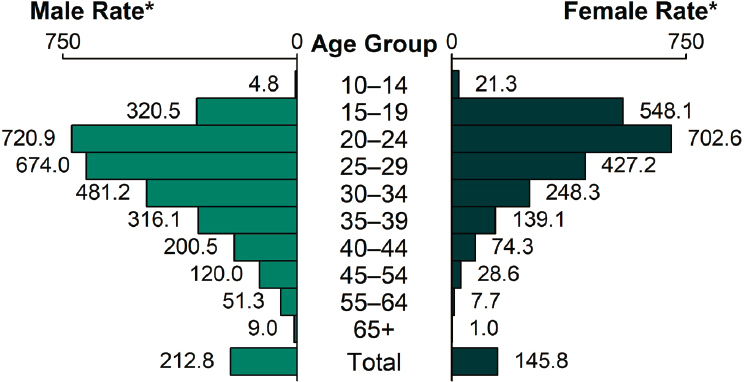

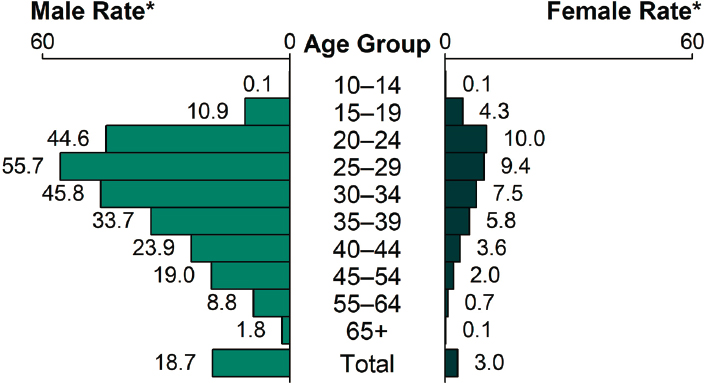

As with chlamydia, adolescents and young adults were the age groups most burdened in 2018. As Figure 2-6 shows, women aged 20–24 had the highest rates of reported cases, followed by those aged 15–19. The trend in men shifted slightly older, with the highest rates of reported cases in those aged 20–24 and the next highest in those 25–29 (CDC, 2019d). Likewise, people aged 15–24 made up more than half of the estimated incident and prevalent infections in 2018 (Kreisel et al., 2021).

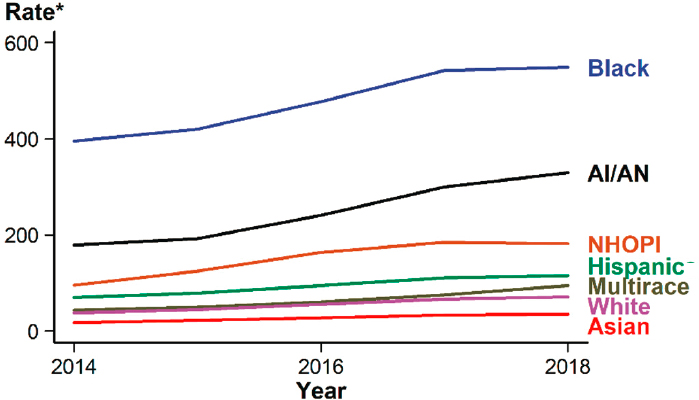

Black, AI/AN, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and Hispanic or Latino/a populations have experienced higher rates of gonorrhea than white or Asian populations. Despite increases for all racial and ethnic groups from 2014 to 2018, rates were highest among Black and AI/AN people (CDC, 2019d) (see Figure 2-7). In 2018, rates among Black people

* Per 100,000.

SOURCE: CDC, 2019d.

* Per 100,000.

NOTE: AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; NHOPI = Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander.

SOURCE: CDC, 2019d.

* Per 100,000.

SOURCE: CDC, 2019d.

were 7.7 times higher than in white people. AI/AN, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and Hispanic or Latino/a people also had rates 4.6, 2.6, and 1.6 times, respectively, that of white people. The rate in Asian individuals was half that in white individuals (CDC, 2019d).

All regions experienced increased rates from 2017 to 2018, but rates were highest in the South and Midwest in 2018 (CDC, 2019d) (see Figure 2-8). As with chlamydia, 40 states reported higher rates in 2018 than in 2017 (CDC, 2019d). While more than 93 percent of counties reported at least one case in 2018, just under half of these were from 70 counties and independent cities3 (CDC, 2019d), suggesting that, like chlamydia, gonorrhea occurs in clusters.

Syphilis

Syphilis is a genital ulcerative disease. Left untreated, it can cause significant complications in multiple stages of infection across decades. Primary and secondary syphilis (the early stages) are often symptomatic

___________________

3 A city that is not in the territory of any county.

and indicate incident infection. Untreated syphilis at any stage can also be transmitted from the pregnant person to the fetus (see Appendix A).

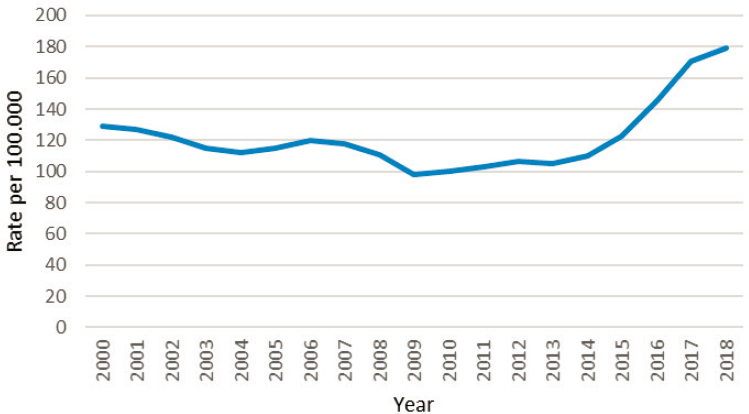

While syphilis is far less common than chlamydia and gonorrhea, the rates of reported primary and secondary syphilis have increased 5-fold over the past two decades (CDC, 2019d). CDC estimates 146,000 incident and 156,000 prevalent infections (all stages) in 2018 (Kreisel et al., 2021). There were 115,045 reported cases of all stages in 2018; this is the highest case count since 1991 and a 13.3 percent increase from 2017 (CDC, 2019d). Despite historic lows in 2000 and 2001, the rate of primary and secondary syphilis has increased almost every year since (see Figure 2-9). There were 35,063 such cases in 2018: a rate of 10.8 cases per 100,000, a 14.9 percent increase from 2017 and a 71.4 percent increase from 2014 (CDC, 2019d). As observed with chlamydia and gonorrhea rates, rates of reported primary and secondary syphilis increased in men and women, in all racial and ethnic groups, and in all U.S. geographic regions from 2017 to 2018.

As with chlamydia and gonorrhea, young individuals (20–29) are disproportionately affected by primary and secondary syphilis. As Figure 2-10 shows, rates of reported cases were highest among men aged 25–29 and women aged 20–24 in 2018. All age groups over 15 experienced increased rates from 2017 to 2018 (CDC, 2019d).

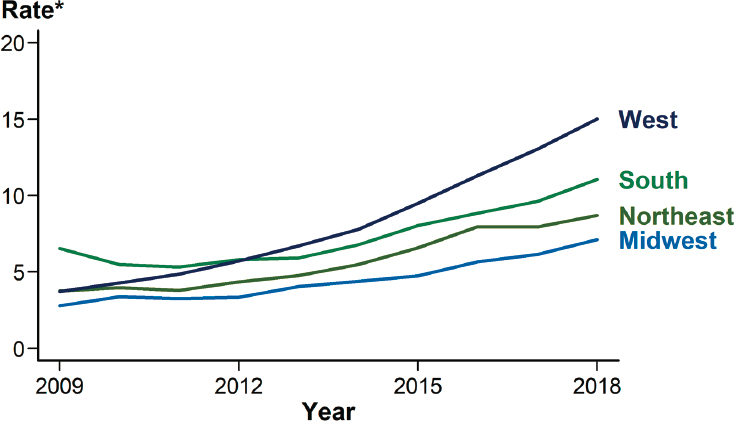

Although rates have been increasing since 2009 for all regions, the West and South had the highest rates of reported primary and secondary syphilis in 2018 (see Figure 2-11). Approximately 61 percent of these cases

SOURCE: Data from CDC, n.d.-b.

* Per 100,000.

SOURCE: CDC, 2019d.

* Per 100,000.

SOURCE: CDC, 2019d.

* Per 100,000.

NOTE: AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; NHOPI = Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander.

SOURCE: CDC, 2019d.

in 2018 came from 70 counties and independent cities, underscoring the need for contact tracing for syphilis (CDC, 2019d).

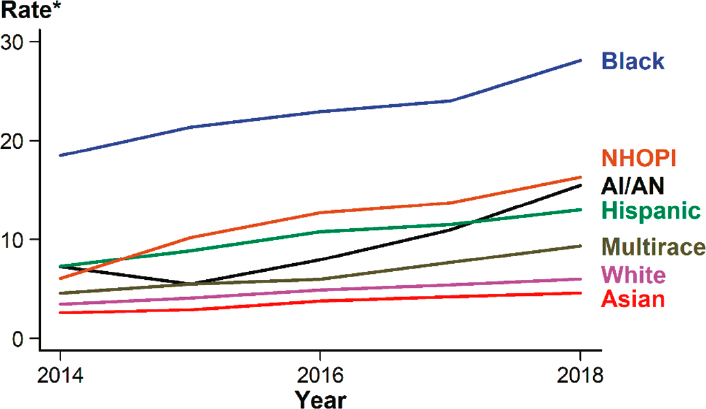

Primary and secondary syphilis rates increased in all racial and ethnic groups from 2014 to 2018 (see Figure 2-12). As observed with chlamydia and gonorrhea, Black, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, AI/AN, and Hispanic or Latino/a people had higher rates than white people in 2018 (CDC, 2019d). The rate of primary and secondary syphilis in these groups was 4.7, 2.7, 2.6, and 2.2 times, respectively, that of white individuals. Asian people had a lower rate than white individuals (0.8 times). Although the rate was highest among Black individuals in 2018, the largest rate increase from 2017 to 2018 was among AI/AN people (40.9 percent increase) (CDC, 2019d).

The rate of reported primary and secondary syphilis among men has increased annually since 2000. Men comprised 85.7 percent of cases in 2018, yielding a rate of 18.7 cases per 100,000. Moreover, more than half (53.5 percent) of the 35,063 cases in 2018 were among MSM (CDC, 2019d). CDC estimates of incident and prevalent syphilis infection (all stages) support this surveillance data, finding that men accounted for more than 71 and 82 percent of all prevalent and incident infections, respectively, in 2018 (Kreisel et al., 2021).

NOTES: 36 states were able to classify ≥70 percent of reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis as either MSM, MSW, or women for each year during 2014–2018. MSM = gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men; MSW = men who have sex with women only.

SOURCE: CDC, 2019d.

Cases among MSW and women also have increased in the past 5 years (see Figure 2-13). For example, the rate of primary and secondary syphilis among women increased 30 percent from 2017 to 2018 and more than 170 percent from 2014 to 2018 (CDC, 2019d). Increased cases in these populations are associated with increased drug use; for instance, their reported use of heroin, methamphetamine, and injection drugs more than doubled from 2013 to 2017 (Kidd et al., 2019). A large proportion of heterosexual syphilis transmission, then, is among men and women using these drugs. Similar trends were not found for MSM (Kidd et al., 2019).

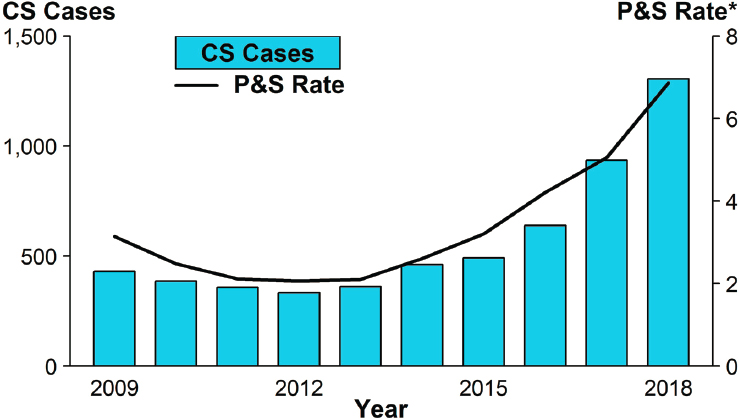

Congenital Syphilis

The rise in cases among women is reflected in rates of congenital syphilis, which can cause miscarriage and stillbirth and myriad lifelong and developmental health problems. Up to 80 percent of children delivered by people infected with syphilis are also infected, and stillbirth and infant death occur among 40 percent of them (see the section on pregnancy in Chapter 3 for more information) (CDC, 2019d). There were 1,306 cases of congenital syphilis in 2018 (CDC, 2019d). This rate, 33.1 cases per

* Per 100,000.

NOTE: CS = congenital syphilis; P&S = primary and secondary syphilis.

SOURCE: CDC, 2019d.

100,000 live births, is almost 40 percent higher than that in 2017 and more than 185 percent higher than that in 2014 (see Figure 2-14). These increases were observed primarily in the West and South, where rates more than doubled from 2014 to 2018 (278.9 percent and 190.3 percent increases, respectively) (CDC, 2019d). These regions had the highest reported rates in 2018; there were 48.5 and 44.7 cases per 100,000 live births in the West and South, respectively (CDC, 2019d). Case rates per 100,000 live births were highest among Black (86.6), AI/AN (79.2), and Hispanic or Latino/a (44.7) individuals. Comparatively, there were 13.5 cases per 100,000 live births among white people and 9.2 cases among Asian and Pacific Islander individuals (CDC, 2019d).

A combination of factors contributes to the high congenital syphilis rate, and screening based on behavioral risk factors alone misses many pregnant people with syphilis (Trivedi et al., 2019). An analysis of national syphilis case reports from 2012 to 2016 demonstrated that half of pregnant women with syphilis had no known risk behaviors for the infection (Trivedi et al., 2019). The most commonly reported risk factors were a history of an STI (43 percent) and more than one sex partner in the past year (30 percent) (Trivedi et al., 2019). Furthermore, cases of syphilis during pregnancy are more common among people who are impoverished,

young (under 29 years of age), Black, and without health insurance and prenatal care. Other risk factors include incarceration, illicit drugs, high community syphilis prevalence, and sex work (Rac et al., 2017). Universal testing during the first prenatal visit and the third trimester could identify asymptomatic infected individuals at high risk for transmitting to the infant. However, congenital syphilis is also a failure of the health care system; half of new cases in 2018 were due to gaps in prenatal testing and treatment (Kimball et al., 2020). A CDC report identified the lack of adequate maternal treatment, despite timely diagnosis, as the most common prevention opportunity missed (30.7 percent) nationally; lack of timely prenatal care (28.2 percent) was another important prevention opportunity missed (Kimball et al., 2020). These missed opportunities varied across the United States and are important in understanding increasing congenital syphilis rates and implementing effective, tailored interventions.

Other Notable STIs

Other STIs include HIV, HPV, HSV types 1 and 2, HBV, Trichomonas vaginalis, Mycoplasma genitalium, chancroid, and Lymphogranuloma venereum. BV is a related dysbiosis, and more research is needed on whether it is sexually transmitted. This section briefly describes these STIs; however, detailed data are not available for all of them because they are not all nationally reportable.

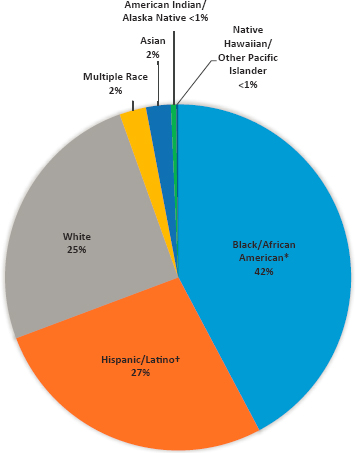

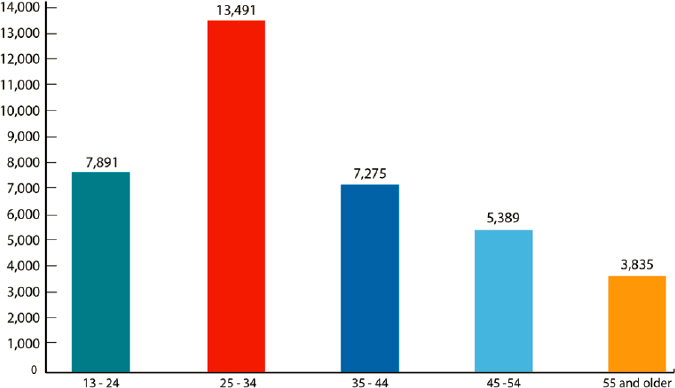

HIV

While surveillance for HIV is rigorous and active, it also has limitations, as less than 40 percent of U.S. individuals have ever been tested (Pitasi et al., 2019). Approximately 1.2 million U.S. individuals were living with HIV in 2018, and an estimated one in seven did not know they had HIV (CDC, 2020e). New HIV diagnoses decreased 7 percent from 2014 to 2018; 37,968 people of all ages were diagnosed in 2018 (CDC, 2020d), 69 percent of which were among MSM, 24 percent were among heterosexuals, and 7 percent were among people who inject drugs (CDC, 2020d). As Figure 2-15 shows, 42 percent of new HIV diagnoses were among Black individuals (though they constitute about 13 percent of the population), and 27 percent were among Hispanic or Latino/a individuals; Black MSM were the most affected subgroup in 2018 (CDC, 2020d). Additionally, new HIV diagnoses were highest among those aged 13–34 (see Figure 2-16). HIV rates were highest in the South (15.6 cases per 100,000) in 2018 (CDC, 2020d). See Chapter 5 for a discussion of the interface of STIs and HIV.

* Black refers to people having origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa. African American is a term often used for Americans of African descent with ancestry in North America.

† Hispanics/Latinos can be of any race.

SOURCE: CDC, 2020d.

SOURCE: CDC, 2020d.

Human Papillomavirus

There are more than 40 types of HPV that can infect the genital tract, and while many infections are asymptomatic and most resolve on their own within a few years, 13 types are associated with an increased risk for anogenital and head and neck cancers (CDC, 2020b). An estimated 42.5 million people aged 15–59 had at least one disease-associated HPV type in 2018, and 13.0 million people in the same age group acquired a new infection in 2018 (Kreisel et al., 2021); 79 million people in the United States have HPV (CDC, 2019b). See Appendix B for information on HPV screening recommendations.

Persistent infections can cause genital warts and precancerous and cancerous lesions of the cervix, vulva, vagina, penis, anus, and oropharynx. HPV types 6 and 11 account for about 90 percent of U.S. cases of genital warts. HPV types 16 and 18 cause approximately two-thirds of cervical cancer cases and one-quarter of low-grade and half of high-grade cervical dysplasia. Three HPV vaccines are licensed for use in the United States and target various oncogenic types: bivalent (types 16 and 18), quadrivalent (types 6, 11, 16, and 18), and 9-valent (types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58). Since 2016, however, the 9-valent vaccine is the only one distributed in the United States. Vaccination is recommended for routine use in everyone ages 11–12, with catch-up vaccination through age 26; the 9-valent vaccine is approved for people up to age 45 (Meites et al., 2019).

The vaccines have had a considerable, positive effect on sequelae of HPV infection, including reduced genital HPV infections among adolescent girls and young women, high-grade cervical lesions and invasive cervical cancer among young women (Lei et al., 2020), and anogenital warts among male and female adolescents and young people (CDC, 2019d). Additionally, NHANES data show a substantial decline in the prevalence of HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 among women aged 14–24 after vaccine introduction (Oliver et al., 2017). NHANES data from 2013 to 2014 also indicate a low prevalence of those four types in young men (Gargano et al., 2017). Furthermore, health care claims data show a positive effect of the vaccine on the prevalence of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 2 and 3 among women aged 15–24 (Flagg et al., 2016).

Despite these effective vaccines, current vaccine uptake does not meet the Healthy People 2030 goal of 80 percent coverage. In fact, approximately 70 percent of girls aged 13–17 had received at least one dose in 2018, but only 54 percent had received all doses. Fewer boys received the vaccine in 2018; about two-thirds had received at least one dose, and less than half had all doses (Walker et al., 2019).

Herpes Simplex Virus

HSV is another prevalent viral STI. The majority of infections are unrecognized; apparent infections manifest as painful and recurring genital and/or anal lesions. In the United States, HSV-2 is responsible for most genital infections; HSV-1 usually causes orolabial infections that are typically acquired in childhood. However, genital infections with HSV-1 are increasing in young adults (CDC, 2019d).

Genital HSV infections are not nationally notifiable like some other STIs, and many patients remain undiagnosed. For instance, more than 87 percent of the HSV-2 seropositive NHANES population (2007–2010) reported never being diagnosed by a health care professional (Fanfair et al., 2013). NHANES data also reveal that age-adjusted HSV-2 seroprevalence decreased from 18 percent in 1999–2000 to about 12 percent in 2015–2016 (McQuillan et al., 2018). All racial and ethnic groups experienced this decline, but seroprevalence remained highest among Black individuals (McQuillan et al., 2018). A CDC modeling paper estimated 18.6 million prevalent HSV-2 infections in those aged 15–49 in 2018 (Kreisel et al., 2021). Furthermore, there were an estimated 572,000 incident infections, 42.3 percent of which were among youth aged 15–24 (Kreisel et al., 2021).

NHANES data show decreasing HSV-1 prevalence and orolabial infection among those aged 14–19; HSV-1 seroprevalence declined significantly: 39 percent from 1999 to 2004 to about 30 percent from 2005 to 2010 (Bradley et al., 2014). Meanwhile, genital HSV-1 infections are climbing among young adults, ascribed partly to the decrease in orolabial HSV-1 infections (Bernstein et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2003). People without HSV-1 antibodies at sexual debut are more prone to genital HSV-1 infection and symptomatic genital HSV-2 infection (Bradley et al., 2014). This susceptibility has implications for people of childbearing age, as primary genital HSV infection during pregnancy raises the risk of neonatal transmission.

Hepatitis B

HBV has no cure and can be transmitted through sexual activity, contaminated blood, and childbirth. Acute infection can resolve, or the condition can become chronic. The risk of infection becoming chronic depends on age at infection: infants and young children have the greatest risk (Fattovich et al., 2008). Long-term, untreated infection damages the liver, potentially resulting in liver fibrosis, liver cancer, and ultimately, liver failure or death (CDC, 2020g). Like HPV, there is an effective vaccine, and it is part of the routine childhood vaccination schedule; universal newborn vaccination in the United States began in 1991 (Kruszon-Moran et al., 2020).

In 2018, there were 3,322 reported incident cases of acute HBV in the United States; after adjusting the data for under-reporting and under-ascertainment, there were an estimated 21,600 acute infections (CDC, 2020g). Including the vaccine in the childhood schedule has lowered rates among children and young adults to age 29. More than half of the reported acute cases, however, were among people aged 30–49 (CDC, 2020g). From 2003 to 2018, acute rates have been consistently higher among men than women. In 2018, rates of acute infection were highest among white and Black people (1.0 reported cases per 100,000), followed by American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic or Latino/a, and Asian/Pacific Islander (0.9, 0.4, and 0.3 reported cases per 100,000, respectively) people (CDC, 2020g).

A CDC modeling paper estimated 103,000 prevalent sexually transmitted HBV infections in those 15 and older in 2018 (Kreisel et al., 2021). NHANES data from 2018 indicate prevalence of past or present HBV infection is 4.3 percent (5.3 percent among men and 3.4 percent among women); this decreased from 5.7 percent in 1999. Asian adults had the highest prevalence of past or present infection (21.1 percent); Black (10.8 percent) and Hispanic or Latino/a (3.8 percent) adults also had higher prevalence than white adults (2.1 percent). Past or present infection was also greater among those born outside of the United States (Kruszon-Moran et al., 2020).

Trichomonas vaginalis

Trichomoniasis is estimated to be the most common nonviral STI in the world (Rowley et al., 2019). Among women, the global prevalence is more common than chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis combined (Rowley et al., 2019). Trichomoniasis has been associated with poor birth outcomes, such as premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, and low birth weight, and with PID and increased risk of HIV infection (Kissinger and Adamski, 2013; Silver et al., 2014; Van Gerwen et al., 2021).

General screening for trichomoniasis is not currently recommended, and it is not a CDC-reportable disease. Modeling has estimated, however, that there were approximately 156 million new cases worldwide in 2016 (Rowley et al., 2019). In the United States in 2018, there were an estimated 2.6 million prevalent infections and an astounding 6.9 million incident infections among people aged 15–59 (Kreisel et al., 2021). Women are 6 times more likely than men to have a prevalent infection. Non-Hispanic Black people are 8 times more likely to be infected than non-Hispanic white people, constituting a dramatic health disparity (Patel et al., 2018). Other risk factors include older age, two or more sex partners in the past year, less than a high school education, life below the poverty level,

smoking, and history of incarceration (Patel et al., 2018; Satterwhite et al., 2013). The prevalence in MSM is very low (Francis et al., 2008). It is currently unclear if extragenital (oral, rectal) infection occurs; a few studies have detected it in these areas by nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) testing, but it is much less common (Carter-Wicker et al., 2016; Francis et al., 2008). Oral and rectal testing or screening is not currently recommended for women or men (CDC, 2015).

Mycoplasma genitalium

Mycoplasma genitalium (MG) is an emerging, recently identified bacterial STI that causes persistent urethritis in people AMAB and is associated with cervicitis, endometritis, PID, and tubal factor infertility in people AFAB (Manhart et al., 2007). Its epidemiology, however, is not currently well understood. In some studies, it is among the most prevalent STIs, usually second only to chlamydia (CDC, 2015; Jensen, 2017; Manhart et al., 2007; Sonnenberg et al., 2013, 2015). A study using data from Britain’s third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles found MG prevalence was 1.2 percent in men and 1.3 percent in women (Sonnenberg et al., 2015). The highest prevalence among men was in those aged 25–34 (2.1 percent); the highest prevalence among women was in those aged 16–19 (2.4 percent). In the study sample overall, more than 90 percent of in men and more than 66 percent of in women were in the 25–44-year-old age group. About half of women and the majority of men reported no symptoms, although MG was associated with postcoital bleeding in women (Sonnenberg et al., 2015). A 2007 study using data from the U.S. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health found prevalence was 1.0 percent among those aged 18–27; prevalence was significantly higher among Black adolescents and young adults (Manhart et al., 2007). Moreover, a 2020 study using data from a large, multi-center clinical validation study of a diagnostic test for MG found overall prevalence was 10.3 percent (Manhart et al., 2020). The prevalence among those aged 15–24 was significantly higher than those aged 35–39, and Black study participants were about twice as likely to have an infection as white participants (Manhart et al., 2020).

Furthermore, antibiotic resistance is increasing. In some countries, the proportion of MG cases with macrolide resistance is greater than 50 percent, with reports of dual or multi-drug resistance, especially in the Asia-Pacific region (Jensen, 2017). CDC included MG in its 2019 antibiotic threats report, indicating that while antibiotic-resistant MG has not yet spread widely in the United States, it could become common without vigilance (CDC, 2019a). Clearly, more research is needed into the natural history of MG infection and its prevalence in the United States.

Chancroid

Chancroid is a reportable bacterial STI caused by Haemophilus ducreyi, although, unlike chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis, it is not a major contributor to the U.S. epidemic of STIs. When infection occurs, it is usually associated with infrequent outbreaks. Chancroid cases peaked in the mid-1940s and decreased after the expansion of effective antibiotics. There have been fewer than 100 reported cases each year since 2000; 2018 had three (CDC, 2019d).

Lymphogranuloma Venereum

Lymphogranuloma venereum is an STI caused by three serovars of Chlamydia trachomatis (L1, L2, or L3). Although it is uncommon in the United States, there are increasing reports of incident cases among MSM (Ceovic and Gulin, 2015). Additionally, it may be more commonly reported among people AMAB because early symptoms are more apparent in them (Ceovic and Gulin, 2015). Clinical symptoms include a painless genital ulcer, lymphadenopathy, and proctitis. Untreated, the later stages of the infection can lead to systemic infection and anogenital fistulas (CDC, 2015; Ceovic and Gulin, 2015).

Bacterial Vaginosis

BV is a dysbiosis caused by a change in the vaginal microbiome, characterized by the loss of hydrogen-peroxide-producing lactobacilli and an increase in facultative and strict anaerobes (Bautista et al., 2016; Muzny et al., 2019). It is the most common cause of symptomatic vaginal discharge in women aged 15–44 (CDC, 2020a). Black and Hispanic or Latina women in North America were found to have significantly higher BV prevalence than white and Asian women (33.2, 30.7, 22.7, 11.1 percent, respectively) (Peebles et al., 2019). BV usually occurs in sexually active people AFAB and is more common among women who have sex with women (WSW) (Muzny et al., 2019). The syndrome is associated with increased susceptibility to other STIs, including HIV, and with other adverse health outcomes, such as PID (CDC, 2020a; Mirmonsef et al., 2012; Peebles et al., 2019). BV can be asymptomatic, so people may be unaware of it. BV may resolve without treatment but can be cured with antibiotics. Recommended therapy results in resolution in only 70–80 percent of women; despite treatment, more than half of people experience recurrent BV within 3–6 months of therapy (Joesoef et al., 1999; Muzny and Kardas, 2020; Workowski and Bolan, 2015).

Understanding of BV pathogenesis and transmission remain complex (CDC, 2020a; Muzny and Kardas, 2020). However, anything that affects the vagina’s pH and the balance of vaginal bacterial growth, such as

vaginal douching, vaginal deodorant, and new or multiple sexual partners, is associated with BV (Bautista et al., 2016; CDC, 2020a; Planned Parenthood, n.d.). Data suggest BV may be sexually transmitted (Fethers et al., 2008, 2012; Muzny and Kardas, 2020; Ratten et al., 2021). BV-associated bacteria may be sexually transmitted (Fethers et al., 2012; Muzny et al., 2019), but more research is needed on whether it is a single keystone pathogen or a combination of sexually transmitted bacteria that causes BV (Muzny and Kardas, 2020).

Coinfection and Reinfection

Given the common route of transmission, an STI may occur as one of several organisms transmitted. For example, gonorrhea and chlamydia, syphilis and HIV, or trichomoniasis and HSV-2 could be transmitted in the same sexual encounter between a coinfected person and a susceptible partner. Reproductive tract perturbations can facilitate the ease of transmission in several ways, including mucosal disruption and increasing inflammatory dynamics (see, too, the above section in this chapter on BV) (Galvin and Cohen, 2004; Nusbaum et al., 2004).

Long-term immunity is provided by prior infection for some STIs, but not for most. For example, many adults are able to recover completely from acute HBV infection; an antibody to the HBV surface antigen confers immunity to subsequent infection (CDC, 2020c; Fattovich et al., 2008). Type-specific HPV protection is thought to protect from subsequent infection for many years, but there are other, less closely related HPV types that circulate in humans, so it is possible to reacquire HPV even after resolution of an infection from a different HPV type (Wang and Roden, 2013). Sexually transmitted HSV results in chronic infections, as does HIV. Curable and/or self-limiting bacterial STIs (e.g., chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis) or parasites (e.g., Trichomonas vaginalis) generate limited (or no) lasting immunity, so reinfection can occur (Cameron and Lukehart, 2014; Hosenfeld et al., 2009; Malla et al., 2014; Menezes and Tasca, 2016). Lack of sustained acquired immunity underscores the risk of lifelong susceptibility to many STIs (see Chapter 7 for information on STI vaccines).

DRIVERS OF STI OUTCOMES AND INEQUITIES

Knowledge does not always lead to better choices…. Barriers to health care are universal, and some other barriers include fear, lack of education, stigma against getting tested, and lack of access to discreet care.

—Participant, lived experience panel4

___________________

4 The committee held virtual information-gathering meetings on September 9 and 14, 2020, to hear from individuals about their experiences with issues related to STIs. Quotes included throughout the report are from individuals who spoke to the committee during these meetings.

Although CDC surveillance data can help public health professionals understand which populations are affected by STIs, these data do not explain why some individuals acquire STIs while others do not and why some groups have higher STI rates. Since The Hidden Epidemic was published more than two decades ago, the rate of common STIs has grown, as has the understanding of factors that increase transmission. In the 1980s, May and Anderson (1987) described the basic reproductive rates of an STI epidemic as Ro = β * c * D, where β is the transmissibility of the organism, c is the number of new partners per unit time, and D is the duration of infection. It is now understood that each component of this model is influenced by complex and ever-changing individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and structural factors, as depicted in the conceptual framework in Chapter 1 (see Figure 1-3).

Transmissibility (β) is influenced by many factors, including the increase in drug-resistant STI infections and changing sexual behaviors, such as an increase in extragenital sex and relaxation of or misuse of barrier protection. Effective antibiotic treatment moderates transmissibility, but drug resistance is fueled by the overuse of antibiotics and the lack of new product development. Condoms also reduce transmissibility of all STIs. The increasing use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention may potentially lead to decreased condom use, leading to high rates of STIs among PrEP users, although recommended quarterly STI screening as part of the PrEP regimen also may potentially increase diagnosis and treatment rates and ultimately reduced population-level burden of STIs (Jenness et al., 2017). It remains difficult to observe secular trends, given the increases in STIs prior to PrEP use and uncertain impacts of treatment as prevention and life-saving antiretroviral medications for those living with HIV. Transmission probability also depends on the context within which sexual partnering occurs. Sexual exposure is a necessary but not sufficient factor for STI transmission. For example, a person could have multiple sexual exposures with multiple partners who are not infected and so never become infected. Another person could have sexual exposure to just one person who is infected and become infected. STI prevalence in a sexual network is dependent on numerous scenarios. Networks that are more densely connected or have concurrency can increase transmission across a network subgroup. Transmission is also influenced by community prevalence.

Number of new partners per unit time (c) is an important attribute because having additional partners increases the probability of coming into contact with an infected person, and individuals with higher numbers of partners tend to be in contact with one another. This can amplify transmission, particularly if the partners have higher rates of STIs (this is a more important variable than partner number). Number of partners

has been increasing because of reduced age of sexual debut, delayed marriage or long-term coupling, and access to more partners because of social media/hookup apps and changing mores that may dissociate emotional attachment and intimacy from sex (CDC, 2017; Heywood et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015). Duration of the infection (D) is elongated when asymptomatic people do not get screened or symptomatic people are either not treated or improperly treated. Screening policies, health care access, and vaccine and therapeutic development rely on financial resources, public awareness, and political will, none of which have been robust for STI treatment and prevention (NAPA, 2018).

In Chapter 1, a social-ecological approach is proposed to guide understanding of the multi-level societal factors that may drive the observed increase in STIs in the U.S. population in general and its unequal distribution across social groups. Understanding the epidemiology of STI inequities and identifying the structural and social factors associated with these inequities are key to developing effective interventions to prevent, diagnose, and treat STIs. This section describes the common individual-, interpersonal-, community-, institutional-, and structural-level social, economic, political, cultural, and environmental factors that affect STI outcomes and inequities in the U.S. population. The sections below highlight drivers of STIs that range from factors such as sexual behaviors, substance use, and sexual networks to health system policies, socioeconomic issues, and societal values, laws, and policies. Technology is an important multilevel driver associated with sexual health and STI acquisition, prevention, and care at all levels of these factors (see Chapter 6 for more information on the role of technology and media).

As this report’s conceptual model describes, intersectionality is an important conceptual and analytic framework in considering the interrelated societal influences on STI risk, acquisition, prevention, testing, and care across and within social groups. A growing body of public health research and practice uses this framework, which has its roots in Black feminist theory and praxis. Intersectionality focuses on how multiple social identities and positions at the micro level (e.g., gender identity, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status) and structural inequities (e.g., sexism, cisgenderism, racism, heterosexism, poverty) at the macro level simultaneously shape individuals’ and groups’ lived experiences in social, economic, political, and historical context (Calabrese et al., 2018; Collins and Bilge, 2020; Earnshaw et al., 2013; Gkiouleka et al., 2018; Howard et al., 2019; Li et al., 2017; Rice et al., 2018).

Intersectionality indicates that the structural inequities outlined in this chapter (e.g., sexism, racism, heterosexism, poverty) contribute to higher rates of STIs for multiply marginalized populations, including Black and Latino MSM; Black, Latina, and AI/AN women; and LGBTQ+ youth. Of

note, these structural inequities influence individual and group access to social, economic, and health care resources that mitigate the risk of STIs (e.g., income, health insurance, usual source of health care, education), as well as societal factors that increase STI exposure, including involvement in sex work, substance use, violence, and judicial involvement and/or incarceration. CDC only provides epidemiological data for some of the aforementioned marginalized groups (e.g., Black MSM, Latina women). However, research suggests that all the aforementioned social groups have disproportionately higher STI rates. These groups face significant discrimination and stigma that deter them from accessing testing and treatment services as a result of the compounding effect of multiple forms of structural inequities and social determinants of health, which need to be addressed to mitigate observed STI disparities (Bowleg et al., 2014; Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2016; Dyer et al., 2020; Glick et al., 2020; Kelly et al., 2018; Leichliter et al., 2020; London et al., 2017) (see Chapter 3 for more information). The STI National Strategic Plan (STI-NSP): 2021–2025 has embraced the importance of addressing the social determinants of health (HHS, 2020), which aligns with this report.

Individual-Level Factors

This section provides an overview of the biological and social individual-level factors that need to be taken into consideration for STI prevention and control. Chapter 3 further describes these factors and their impact on various priority populations.

Biological Factors

Research on biological modifiers to STI susceptibility is limited. While rates of infection among Black, Latino/a, and AI/AN individuals are higher for many STIs (CDC, 2019d), no data exist to indicate a biological reason for this. Some indicators suggests that women, particularly young women, are more susceptible to infection and that certain types of sex behavior lead to a higher likelihood of infection. For example, vaginal and anal exposure and lack of penile circumcision have well-demonstrated impact on STI susceptibility (Critchlow et al., 1995; Jacobson et al., 2000; Sharma et al., 2018), as do modifiable practices, such as contraceptive methods, and the coexistence of other conditions, such as BV (see Chapter 7 for more information on the effects of contraceptive measures). A number of these variables are also associated with social determinants of health that may also influence susceptibility, as described below.

Sex, gender, sexual orientation, and sexual behavior

Irrespective of gender identity, for persons with a cervix who engage in vaginal sex, the primary site of infection with common mucosal pathogens such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis are the columnar cells of the cervix and endocervix (Jacobson et al., 2000). In prepubertal sexually active persons with a cervix, vaginal squamous epithelium is susceptible to gonococcal or chlamydial vaginitis. During the hormonal shifts in puberty, mediating changes make the vaginal epithelium less susceptible to infection (Colvin and Abdullatif, 2013). A biological contributor to the increased STI risk in adolescents may be a manifestation of the residual columnar cervical epithelium (“ectopy”) present at the cervix as this transition occurs (CDC, 2019d; Critchlow et al., 1995). Interestingly, some hormonal contraceptives are also associated with increased ectopy (Bright et al., 2011) and have been hypothesized to increase susceptibility to gonorrhea and chlamydial infections (Mohllajee et al., 2006; Morrison et al., 2004), although data remain inconclusive (Berry and Hall, 2019).

Individuals with a vagina are relatively more susceptible to infection from penile-vaginal penetrative intercourse. This may be due to the retention of genital secretions within the vaginal vault, thereby prolonging exposure of the cervical epithelium to the infectious agent, whereas the penis would be removed from the vagina and cervical exposure. Susceptibility increases with increased trauma to the epithelium during sex. While data are lacking, people who engage in receptive rectal intercourse may be analogously susceptible to infection related to retaining genital secretions and sustaining possible trauma to the anal mucosa. The transmission efficiency of receptive or active oral sex is a topic of ongoing debate. Additionally, kissing may be associated with oropharyngeal gonorrhea transmission (Chow et al., 2019). For people AFAB with partners AFAB, the biological efficiency of STI transmission appears to be somewhat lower (however, this depends on whether they also have sex with partners AMAB and on other factors, such as sexual violence). The biological susceptibility to STIs among trans and non-binary people after medical gender affirmation procedures is unknown. Testosterone hormone therapy to affirm gender identity, however, has been found to reduce Lactobacillus dominance in the vaginal microbiome of trans men (Winston McPherson et al., 2019); this altered microbial environment may be correlated with BV, which could increase susceptibility to other STIs.

Circumcision

Penile circumcision is a common elective procedure rooted in cultural and religious practices. It is associated with reduced susceptibility to HIV and some other STIs (Sharma et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019b). The difference in susceptibility may reflect changes to the epithelial surface of the circumcised penis, with epithelial thickening

and increased keratinization, though some scientists postulate alternative mechanisms (Dinh et al., 2012; Kigozi et al., 2020). Inflammatory changes in diverse populations of uncircumcised men are implicated in higher HIV and STI risks (Anderson et al., 2011; Lemos et al., 2014; Morris and Wamai, 2012).

A meta-analysis of 49 studies from around the world found an estimated 42 percent reduction in circumcised men’s risk for HIV acquisition; heterosexual men had a greater risk ratio reduction (72 percent) than MSM (20 percent) (Sharma et al., 2018). A subsequent systematic review and meta-analysis found circumcision was associated with 23 percent reduced odds of HIV acquisition among MSM (Yuan et al., 2019). This protection, however, was stronger among circumcised MSM in low- and middle-income countries, with no significant benefit found in MSM from high-income nations (Yuan et al., 2019). A third systematic review and meta-analysis found a 7 percent protective benefit for circumcised compared to uncircumcised MSM; it was higher among men from Africa or Asia (38 percent) than among men from other regions (Zhang et al., 2019b). The potential impact on the MSM HIV pandemic suggests that circumcision could play a role in combination prevention efforts (Zhang et al., 2019a, 2020). Methodological differences across studies may help to explain the wide variations in protective efficacy (Qian et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019b). Penile circumcision is now firmly grounded as an important HIV prevention effort in sub-Saharan Africa, where incidence rates are high and circumcision rates are low (Vermund et al., 2013). Universal neonatal circumcision in high HIV incidence areas has been advocated but is far from being a global standard (Joseph Davey et al., 2016; Morris et al., 2016). Debate continues as to the utility of neonatal circumcision for high-income, lower HIV incidence venues (Earp, 2015).

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that circumcision is also associated with reduced risk for acquiring HPV and ulcerative STI pathogens, such as HSV-2 and, theoretically, chancroid, among men and among women who have sex with men (WSM) (Morris et al., 2019; Tobian et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2019). The effect on risk for syphilis and mucosal STIs, such as gonorrhea and chlamydia, is less certain (Jameson et al., 2010; Sharma et al., 2018; Tobian et al., 2009; Weiss et al., 2006). It may be concluded that STI rates could be reduced with male circumcision to greater or lesser extent, depending on context. In nations or populations with higher HIV and STI rates, the risk–benefit ratio will favor circumcision; in lower risk settings, it may not be cost effective.

Vaginal and rectal microbiome and douching

A healthy vaginal microbial environment is composed of hydrogen-peroxide-producing lactobacilli (Martino and Vermund, 2002), which likely protect against the overgrowth of both endogenous flora and exogenous organisms. Vaginal flora and lactobacilli can be diminished with douching, which will physically wash out protective lactobacilli, opening ecological niches for other organisms, including STIs (Newton et al., 2001; Tsai et al., 2009). On balance, evidence suggests that repeated douching can diminish lactobacilli dominance and increase the risk of reproductive tract infections (Martino and Vermund, 2002).

Some individuals douche vaginally, particularly after sex or the menstrual cycle. According to the 2015–2017 National Survey of Family Growth, about 16 percent of women did so in the previous year (CDC, 2019c). Douching is more prevalent among Black adolescents and women than among white adolescents and women, which could be due in part to opinions from mothers, peers, and media that associate douching with “hygiene and cleanliness,” particularly after menstrual cycles (Annang et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2016; DiClemente et al., 2012; Funkhouser et al., 2002a,b; Martino et al., 2004). For example, a study of Black young women aged 14–20 in Atlanta, Georgia, found 43 percent reported ever douching, and 29 percent reported douching in the past 90 days (DiClemente et al., 2012). Another study of a cohort of women in Los Angeles found 61 percent of Black women reported douching in the past year compared to 40 percent of white women (Brown et al., 2016). However, education can reduce douching prevalence (Cottrell, 2010; Grimley et al., 2005). Reducing or eliminating vaginal douching may reduce STI acquisition.

People who engage in receptive anal intercourse may douche rectally (Dangerfield et al., 2020; Hambrick et al., 2018). Recent rectal douching among MSM (at least once within the past 12 months) before receptive intercourse varied across studies in a 2018 literature review (43–64 percent) (Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2018). The reasons included hygiene maintenance, request from a sexual partner, preparation for intercourse, and advice from peers (Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2018). It is hypothesized that HIV and other STIs could cross through or infect rectal mucosa more easily after douching than in the more natural state, because some douching preparations may disrupt the protective epithelium or because of potential rectal trauma sustained during douching (Baggaley et al., 2010; Li et al., 2019). Some studies have found an association between rectal douching and increased odds of infection with HIV and other STIs (Hassan et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019); additional research into co-occurring behaviors that increase the risk of infection is needed.

Alcohol, Substance Use, and Compulsive Sexual Behavior

Both alcohol and substance use are associated with increased sexual risk behavior and STI risk (Boden et al., 2011; Cook et al., 2006; Feaster et al., 2016; Strathdee et al., 2020). Results from a 30-year longitudinal birth cohort study from New Zealand provide compelling evidence for increasing risk of STI diagnoses as alcohol use increases (Boden et al., 2011). Furthermore, binge drinking is associated with a 5 times higher risk for gonorrhea among women (Hutton et al., 2008). Similarly, case–control and longitudinal studies and surveys show elevated STI risk among individuals who use illicit substances (Cook et al., 2006; Feaster et al., 2016; Strathdee et al., 2020). Alcohol, and particularly substance use, can increase the risk of STI acquisition through multiple mechanisms. First, both are associated with increased sexual risk behavior, including condomless intercourse and increased number and concurrency of sex partners (Adimora et al., 2007, 2011; Berry and Johnson, 2018; Celentano et al., 2008; Khan et al., 2013; Strathdee et al., 2020). Second, alcohol and substance use, addiction, and dependence are associated with increased participation in transactional sex (Gerassi et al., 2016; Patton et al., 2014; Strathdee et al., 2020)—a primary risk factor for STIs. Third, direct blood contact represents a possible STI transmission mechanism among people who use injection drugs and other individuals who share needles (Celentano et al., 2008; Khan et al., 2013).

Of note, the association of substance use pattern and STI risk has been shown to differ across risk groups defined by gender and partner gender (i.e., for MSW versus MSM versus WSM versus WSW) (Feaster et al., 2016). For women (both WSM and WSW), severity of street drug use (e.g., heroin, crack cocaine) was most strongly associated with STI risk, while for MSM, severity of club drug use (e.g., powder cocaine, methamphetamine, ecstasy, hallucinogens) most predicted STI risk. Associations between substance use patterns and STI risk were weakest for MSW (Feaster et al., 2016). These findings linking club drug use to STI risk for MSM are in line with evidence suggesting a high prevalence of sexualized recreational drug use (chemsex) among MSM (although both systematic reviews found wide variations in prevalence estimates) (Maxwell et al., 2019; Tomkins et al., 2019). Sexualized drug use involves taking recreational drugs to enhance sexual experiences (Tomkins et al., 2019). Of concern, chemsex among MSM has been linked to increased sexual risk behavior, including condomless sex, group sex, and transactional sex, as well as increased risk of STI acquisition (González-Baeza et al., 2018; Tomkins et al., 2019).

Research also indicates that compulsive sexual behavior (i.e., hypersexuality, sex addiction) is often comorbid with alcohol or substance use

disorders (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2020; Garner et al., 2020; Moisson et al., 2019). While compulsive sexual behavior continues to be inadequately defined and controversy regarding its classification as a mental health condition remains unresolved, a growing body of literature supports an association with increased risk behavior (Derbyshire and Grant, 2015; Yoon et al., 2016). Taken together, the well-established relationship of alcohol and substance use with STI risk and the elevated prevalence of compulsive sexual behavior among alcohol and substance users suggests the utility of a greater integration of alcohol/substance use services and STI services. For example, routine screening for sexual risk behavior and STIs in alcohol and substance use treatment represents a promising strategy to promote STI prevention and management among key populations at increased risk. This integration of services is a major component of the STI-NSP: 2021–2025, and the committee concurs with and supports including coordinated efforts to address the syndemic of STIs (including HIV and viral hepatitis) and substance use disorder as one of the plan’s high-level goals (HHS, 2020). See Chapter 12 for more information on the STI-NSP: 2021–2025. Box 2-2 lists additional important individual-level factors associated with acquiring and preventing STIs.

Interpersonal-Level Factors

Interpersonal factors that drive STIs represent any unit that transcends the individual. Dyadic (two individuals), triadic, and other network levels are all interpersonal levels that require consideration. Over the past century, U.S. STI epidemiology analyses have focused on individuals. Clearly, such approaches are limited, as they do not account for the other important actor(s) that can confer a context of risk for transmission or acquisition. Foundational work by Ed Laumann and others clearly identified that individuals could have “lower-risk behavior” (i.e., more condom use) but be at higher risk of STIs due to the nature and composition of their sexual networks (Laumann and Youm, 1999). Three important interpersonal factors that drive STIs are dyadic (interpersonal violence and discrimination) and network (sexual network composition; see additional discussion on this topic in Chapters 3 and 8).

Interpersonal Violence

Interpersonal violence most commonly includes a dyad where the tie between the two individuals is characterized by emotional, sexual, and/or physical violence (Mercy et al., 2017). Violent victimization, such as intimate partner or dating violence (Kaplan et al., 2013; Lowry et al., 2017; Mercy et al., 2017), is an example of such ties. One type of intimate partner

violence, reproductive coercion, involves partner pressure to become pregnant and active attempts to prevent the use of contraceptive methods (Rome and Miller, 2020). Reproductive coercion and intimate partner violence have been associated with STI acquisition, unintended pregnancy, and low consistent and correct condom use (Rome and Miller, 2020). Even within intimate partner violence at the population level, it varies significantly by population and community. For example, trans women experience violence at much higher rates and are likely even more vulnerable to these experiences than cisgender women. A significant burden

of the violent deaths among trans women originates from violence perpetrated by sexual partners. Substance use, incarceration, posttraumatic stress disorder, and police brutality all enhance, propagate, and intensify interpersonal violence (Cohen et al., 2013; Krüsi et al., 2014; Mimiaga et al., 2019; Poteat et al., 2014; Reback et al., 2018), which is associated with increased STI transmission.

Interpersonal Discrimination

Interpersonal discrimination has been defined as the negative “nonverbal, paraverbal, and even some of the verbal behaviors that occur in social interactions” (Hebl et al., 2002, p. 816). Focused and repeated actions, such as sexist, homophobic, transphobic, or racist behaviors, are based on perceived membership in stigmatized groups. Interpersonal discrimination can affect physical and mental health and health-seeking behaviors (Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009; Sellers et al., 2013). Providers’ bias, stigma, and discrimination can affect the delivery and quality of STI care (Wiehe et al., 2011) and therefore further exacerbate disparities in STI rates (see Chapter 11 for more information on the effects of bias in STI health care systems).

Social Networks

Social network composition and structure can explain social context, social norms, social capital, and interpersonal connections, and all can drive STI transmission. Only in the past century have network analytic approaches, software, and data-collection tools become rigorous enough to be at a level commensurate with traditional individual-level epidemiology—a movement toward network epidemiology, which looks beyond the individual actor (Valente, 2012). Sexual network analysis is one of the foremost methodological tools used to investigate “risk-potential networks” (Friedman and Aral, 2001) through which STIs are spread (Friedman et al., 2009; Klovdahl, 1985; Valente and Fujimoto, 2010; Valente et al., 2004). Various network characteristics have been identified as contributing to individuals’ behaviors, risk perceptions, or infectious outcomes related to STIs: occupying central, peripheral, or bridging5 positions within social networks, being a member of a network core group,6 varying personal network density, having multiple sex ties concurrently,

___________________

5 This is the structure where an individual may connect two groups that are otherwise not connected. This structure has implications for STI transmission across groups.

6 Typically, this is the group at the center of the sexual network and where the majority of STI transmission occurs.

and network distance between infected and susceptible persons (Auerbach et al., 1984; Bettinger et al., 2004; Fichtenberg et al., 2009; Friedman et al., 1997; Klovdahl et al., 1994; Latkin et al., 1995). Sex network analysis also has been used to model STI epidemics, and the contributions of social scientists to understanding cultural and behavioral variations that channel infectious disease within dynamic systems have grown enormously (Goodreau, 2010).

Most network-level forces that relate to STI transmission are focused at the dyadic/partner level, such as main and casual partnerships and measuring the most recent sex partner (Fichtenberg et al., 2009; Friedman and Aral, 2001; Schneider and Laumann, 2011). There are several network-level factors that drive STI transmission and that have been better illuminated with local and whole network analyses, including (1) core-periphery network structures7 and sex network mixing and (2) concurrency. Early conceptualizations of the core group identified the high rates of partner exchange that concentrate STIs within groups (Brunham, 1997; Thomas and Tucker, 1996; Wasserheit and Aral, 1996). Key connections to noncore members, such as those adjacent to cores and the periphery, however, are critical to ongoing STI epidemics. Understanding of this work was extended to include core-group behaviors but with a focus on the behavior of network members connected to the individual (Aral, 1999; Wasserheit and Aral, 1996). Laumann and Youm (1999) expanded this work, with a focus on network mixing and particularly how different core, periphery, and adjacent groups mix to drive onward STI transmission; intragroup mixing within racial and ethnic groups was more common for Black community members as a mechanism for describing disparities in STI rates in the United States. Other network forces, such as norms and personal influence, are important. These network forces operate through community norms, which are described below and are closely related to network interventions described in Chapter 8.

Social and Societal Contextual Factors

Very often, folks who came in with an STI had many additional issues that needed to be addressed, whether it be gender identity issues, high-risk sexual behavior, depression, bipolar disorder, substance abuse, homelessness, and the list goes on. So, despite a patient perhaps presenting with what might seem like a pretty straightforward STI—I know the medication, I know how to treat this—there were usually many other issues that needed to be addressed.

___________________

7 Sex network ties are partitioned into two general groups: the core and the periphery, where the core typically has high density and the periphery (fewer sex network connections and less transmission) has connections to the core.

And it’s hard to do that when you have a small amount of time. So when we discuss with providers methodologies for treating and addressing STIs, we must realize that these do not occur in a vacuum, and that the STI is only one aspect of the person who is presenting that day—in fact, the STI may be the least important thing that they need addressed.

—Participant (health care provider), lived experience panel

There is considerable overlap among the institutional-, community-, and structural-level factors that shape STI outcomes and inequities; therefore, this section collectively considers these interrelated contextual factors.