Summary

Cancer is the second leading cause of death among adults in the United States after heart disease. In 2020, an estimated 1.8 million new cases of cancer were diagnosed and more than an estimated 600,000 cancer deaths occurred. However, improvements in cancer treatment and earlier detection are leading to growing numbers of cancer survivors (defined as any living person with a history of cancer, from the time of diagnosis until death). The median age for a cancer diagnosis in the United States is 66 years; thus, approximately half of all newly diagnosed cancer patients are working-age adults.

In 2020, the 10 most common cancers diagnosed in the U.S. adult population were:

- Breast cancer

- Lung and bronchus cancer

- Prostate cancer

- Colorectal cancer

- Melanoma of the skin

- Bladder cancer

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Kidney and renal pelvis cancer

- Uterine cancer

- Leukemia

For many people with cancer, the cancer itself and its treatment can cause substantial adverse effects, referred to in this report as cancer-related

impairments, that can be physiologic (e.g., pain, fatigue) or psychologic (e.g., depression, anxiety). Some impairments are self-limiting and resolve once treatment or healing is complete (acute effects), such as postoperative pain; others begin during treatment, but persist afterward (long-term effects), such as chronic neuropathy following chemotherapy; and still others, such as radiation fibrosis, may not be evident during treatment, but may develop months, or even years, after the cancer treatment is complete (late-onset effects).

Cancer-related impairments can affect an individual’s ability to function, placing limitations on activities such as walking, standing, lifting, carrying, or thinking. These functional limitations can interfere with an individual’s ability to fully perform routine actions and responsibilities in life, including work.

While all cancers and their treatments have the potential to cause impairments and associated functional limitations, some cancers and cancer treatments are more likely to cause these consequences than others, depending on cancer site, cancer stage, type and duration of treatment, as well as other clinical factors, including comorbidities. Cancer-related impairments and the resulting functional limitations may or may not lead to disability as defined by the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA); however, adults surviving cancer who are unable to work because of cancer-related impairments and functional limitations may apply for disability benefits from SSA. SSA has a five-step disability determination process, which considers listings of medical impairments (“listings”) including malignant neoplastic disease (cancer). SSA considers the medical impairments in the listings to be severe enough to prevent an adult from performing any gainful employment if listed criteria are met. SSA’s current Listing of Impairments for adult cancers focuses predominantly on terminal and metastatic cancers with a high likelihood of death and do not include, for the most part, impairments and functional limitations that may result from cancer treatments.

COMMITTEE’S CHARGE

In order to keep the information on which it bases its disability listings for adult cancers up to date, in 2019, SSA asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) to convene a committee of experts to provide an overview of the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of selected adult cancers, particularly breast cancer and lung cancer (see Box S-1 for the committee’s complete Statement of Task). The study committee was asked to not examine access to care for diagnosing and treating cancer, and it was asked to not make recommendations based on its overview of the current status of cancer diagnosis, treatment, or prognosis.

COMMITTEE’S APPROACH

To complete the Statement of Task, the National Academies empaneled a committee of 15 members with expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer, lung cancer, hematopoietic cancers, colorectal cancer, radiation oncology, cancer survivorship and rehabilitation, long-term and late-onset effects of cancer and its treatment, cognitive impairment, primary care, cancer research, mental health, and epidemiology.

The committee held five meetings that included two public sessions and conducted extensive literature searches. At the committee’s request, SSA provided data for cancer disability claims and claims overall for 2015–2019. These data informed the committee’s considerations of other cancers—specifically colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, liver and bile duct cancers, leukemias, lymphomas, multiple myeloma, ovarian cancer, head and neck cancers, and melanoma—in addition to breast cancer and lung cancer, in its overview of the current status of the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of select common adult cancers.

CHANGING CANCER EPIDEMIOLOGY

Between 1992 and 2017, the number of new cancer cases diagnosed annually (incidence rate) in the U.S. adult population has declined by about 21% and the annual number of deaths declined by 43% during this period. The incidence rate of many cancers has changed in recent decades as a result of public health efforts (e.g., tobacco control and screening and removing precancerous colon lesions, have reduced the incidence of lung cancer and colorectal cancer, respectively), changes in standards of care (e.g., breast cancer incidence decreased slightly in the 2000s due to recommendations against the use of postmenopausal hormone replacement), and lifestyle behaviors (e.g., the growing obesity epidemic may result in increasing incidence of some cancers).

In 2020, about 55% of the estimated 276,480 new breast cancer cases were diagnosed in women aged 64 years or younger. Although the incidence rate of breast cancer in women older than 50 has remained about the same, over the past 10 years, the incidence in women under age 40 has been rising. While breast cancer occurs in men, it is rare.

The incidence rate of lung cancers is decreasing. One-third of the estimated 228,820 lung cancer diagnoses in 2020 were made in people younger than 65, primarily those aged 55–64 years. Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 85% of all new cases of lung cancer and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for the remaining 15%. Smoking, a main cause of both NSCLC and SCLC, contributes to 80–90% of lung cancer, with an estimated latency period of about 20 years; however, not

all lung cancer is associated with smoking and people who never smoke can develop lung cancer.

These data are reflected in the disability claims received by SSA. Between 2015 and 2019, the total disability claims awarded by SSA with cancer as the primary diagnosis also steadily decreased from 125,904 to 114,187. Breast cancer was the most common diagnosis in the cancer claims (16%), followed by lung cancer (14%) and colorectal cancer (12%); other cancers listed in the SSA claims (in order of frequency) are head and neck cancers, pancreatic cancer, nervous system cancers, leukemia, lymphoma, liver or bile duct cancers, and ovarian cancer.

Cancers with the greatest mortality are not necessarily those with the greatest incidence. Lung cancer is the leading cause of U.S. cancer deaths and breast cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths. Pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, liver cancer, and esophageal cancer have particularly high mortality rates relative to their incidence rates. Cancer mortality rates have fallen since 1991, primarily due to declines in mortality for breast, colorectal, prostate, and particularly lung cancer.

The decline in mortality has resulted in a growing number of cancer survivors. In 2019, there were an estimated 16.9 million U.S. cancer survivors; this number is expected to increase to more than 26 million by 2040. About one-third of cancer survivors are younger than 65 years. Cancer-specific survival rates have improved over the years, meaning more people are living longer after their diagnosis, although there are often substantial differences across cancer types. Survival rates tend to be better for cancers that are localized at diagnosis (i.e., confined to the tissue of origin) as is often the case for breast cancer, whereas cancers that are typically diagnosed at more advanced stages, such as lung cancer or ovarian cancer, tend to have poorer survival rates. Outcomes such as survival are based on much more than stage at presentation.

Conclusions

- The population of cancer survivors is growing and will continue to do so as a result of earlier diagnosis of some cancers and advances in treatments.

- Cancer survivors are living longer with impairments and functional limitations that are a result of their cancer and its treatment.

SCREENING FOR, DIAGNOSING, AND STAGING CANCERS

Effective screening tests are available for some cancers, including colorectal cancer, lung cancer, and breast cancer; however, not all people who are eligible are actually screened. Moreover, many people, particularly

younger people without known risk factors such as a family history of cancer, are below the age threshold for screening and may present with more advanced cancers when detected. While screening can be beneficial, it is not without risks such as false positives.

A cancer diagnosis may include pathological tissue examination, imaging studies (x-rays, computed tomography scans, ultrasound imaging, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography), and other diagnostic techniques for specific cancers. A cancer diagnosis involves a biopsy procedure—needle or surgical—to collect a tissue sample for microscopic examination by a pathologist to differentiate and stage the cancer and identify molecular biomarkers.

A localized or early-stage cancer is generally a single tumor, without evidence of spread (metastasis) beyond the initial site; advanced stage cancer shows evidence of metastasis to one or more distant sites. The most common cancer staging system is that of the American Joint Committee on Cancer, which differs for each cancer type and ranges from stage I (localized/early stage) to stage IV (metastatic/advanced stage). The stage is determined on the basis of the T stage (size or extent of the primary tumor), the N stage (the extent of regional lymph node spread), and the M stage (the presence or absence of distant metastasis). For breast cancer, staging also involves non-anatomical factors such as tumor biomarker status.

Treatment approaches often require molecular biomarker information in addition to anatomic information for staging. For example, breast cancers are classified based on the presence of specific receptor proteins on the surface of cancer cells, including hormone receptors (HRs)—estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PR)—and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2, also called HER2/neu). Cancer biomarker testing includes analysis of DNA from cancer cells and possibly other genomic and molecular tests.

Lung cancers are classified by the microscopic appearance of the cancer cells to distinguish SCLC from NSCLC as well to differentiate between the subtypes of NSCLC. In addition, using immunohistochemistry testing and molecular biomarker testing, lung cancers may be further classified by whether the cancer cells exhibit specific genetic abnormalities, such as mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene, and by their expression of the programmed cell death ligand-1–cell surface receptor protein. Biomarkers are used together with the cancer stage to determine a cancer treatment plan and prognosis.

Conclusions

- Screening can help to detect cancers early, when they are most likely to be cured; however, screening tests are not always used and are not available for many cancers.

- The increasingly common use of new molecular and genomic assays to refine the diagnosis of many cancers can help to identify patients who may benefit from targeted treatments.

TREATING CANCER

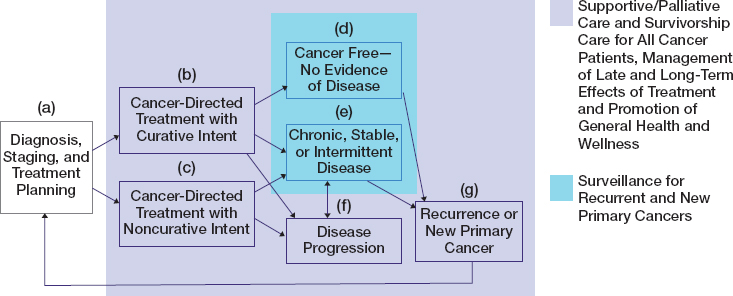

Each person’s experience of cancer is unique from the time of diagnosis, through treatment, to survivorship, and for some patients to end of life. A patient’s cancer care trajectory, shown in Figure S-1, rests on many factors including the type of cancer the patient has, how far the cancer has progressed in the body, what treatments are available and tolerated by the patient, and the outcomes they experience, including mental and physical health. After a patient receives a diagnosis of cancer and begins treatment planning with the cancer care team (a), supportive and palliative care along with survivorship care may be initiated regardless of whether the patient is to be treated with curative intent (b) or noncurative intent (c). Patients who are cancer free after treatment (d) or who have chronic, stable, or intermittent disease (e) may be monitored for prolonged periods to assess for any recurrent or new primary cancers (g). Patients who receive noncurative treatments (c) may also have chronic, stable, or intermittent disease (e) and undergo surveillance for the development of cancer recurrence or a new primary cancer (g). Whether treated with curative or noncurative intent, some patients experience a progression of their cancer (f). Regardless of the patient’s cancer care trajectory or where she or he is along it, palliative or supportive care and survivorship care are relevant to all patients. Palliative or supportive care (distinct from end-of-life care) encompass treatments and services designed to prevent and alleviate suffering and support the best possible quality of life for patients.

Standards of Care

Clinical practice guidelines developed by professional organizations such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network provide recommendations on standards of care for many kinds of cancer. Most cancers are treated with local therapies—surgery and radiation. Less common local therapies such as ablation and embolization may also be used for some cancers. Systemic therapies, such as chemotherapy, may also be administered before (neoadjuvant) or after (adjuvant) surgery. For certain cancers, active surveillance or watchful waiting determine if and when treatment is necessary.

Surgery to remove the tumor can be performed to treat localized cancer and for palliation of some symptoms. Surgery may also be used for biopsy to stage the cancer, to prevent the development of cancer (e.g., prophylactic mastectomy) in high-risk individuals, and for reconstruction after tumor resection or complications of cancer treatment. Although most postoperative adverse effects resolve with healing, long-term effects can include chronic pain, limitations in range of motion, infection, lymphedema, and deformities that may be cosmetic (e.g., from a mastectomy) or functional (e.g., amputation).

Radiation therapy seeks to damage the DNA in cancer cells and kill the cells. The most common form of radiation therapy is external beam radiation therapy although other types of radiation therapy may also be used. Radiation therapy is typically delivered as daily fractions of a dose over several weeks in order to allow the normal cells to repair themselves and repopulate damaged tissues. Long-term effects from radiation can include lymphedema, tissue scarring, heart disease, and the development of other cancers.

Systemic therapies include chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and stem cell therapy. The use of these therapies depends on the type of cancer, its staging, and other patient characteristics, including genetics (both germline and somatic mutations). Chemotherapy, which uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, affects rapidly growing cells regardless of whether they are cancer cells or normal cells. Some systemic therapies are associated with a number of acute and long-term adverse effects such as peripheral neuropathy, cardiac dysfunction, and chronic fatigue.

Endocrine therapies are used for both localized and metastatic cancers that are HR-positive. They may be taken for long periods of time. Targeted therapies are a form of personalized medicine; their use is based on whether a patient’s tumor expresses certain biomarkers, which indicates that the targeted therapy is likely to be effective. Targeted therapies have significantly improved survival of many patients with advanced cancers;

however, they also can result in a number of chronic toxicities. There are different immunotherapy approaches that include nonspecific immune system enhancers, such as interferon, cancer vaccines, adoptive T-cell therapy, and immune checkpoint inhibitor antibodies. These agents can also cause immune-related adverse effects that can affect every organ in the body and can even be fatal; however, the long-term and late-onset effects of these therapies are poorly understood.

Finally, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, also called bone marrow transplant, is frequently used for patients with hematologic cancers. Transplants may be autologous (using the patient’s own stem cells) or allogenic (receiving cells from a related or unrelated donor). The latter transplant carries the risk of graft-versus-host disease, among other adverse effects.

Breast Cancer

Breast cancer treatment is determined by clinical practice guidelines based on stage and other biologic aspects of the cancer, patient comorbidities, menopausal status, and patient preferences. A combination of local treatments along with systemic therapy is typically used. A key determinant of invasive breast cancer treatment is receptor status, chief among which is the presence or absence of HRs and HER2. About 68% of breast cancers are HR-positive/HER2-negative, 10% are HR-positive/HER2-positive, 10% are triple-negative (ER-, PR-, and HER2-negative), and 4% are HR-negative/HER2-positive.

For localized breast cancer, surgery typically takes the form of breast-conserving surgery (e.g., lumpectomy) or mastectomy. Surgery for invasive breast cancer requires a sentinel lymph node biopsy, and if the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes (regional breast cancer), an axillary node dissection may be performed. Lymph node dissection has potential adverse effects including lymphedema and neuropathy. Radiation therapy to the whole breast is standard of care, but partial breast irradiation techniques may also be used for some patients; postmastectomy radiation is generally used for patients with stage III breast cancer.

Systemic treatment for localized breast cancer may include endocrine therapy (e.g., tamoxifen or an aromatase inhibitor) for HR-positive breast cancer, which may be taken for many years. Other systemic therapies may target the HER2 protein. Triple-negative breast cancer is treated with chemotherapy, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, and immunotherapy.

Fewer than 10% of patients are initially diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer (i.e., breast cancer that has typically spread to the liver, brain, bones, or lungs). Treatment for metastatic breast cancer is determined by HR and HER2 status, next-generation sequencing and tumor genomics,

timing and types of prior therapies, the need to achieve a response to therapy quickly because of impending or actual organ damage, symptoms, and patient preference.

Lung Cancer

Standards of treatment for lung cancer are determined by tumor histology, tumor location/size, stage, molecular characteristics, as well as the patient’s health and comorbidities. As with breast cancer, there are clinical practice guidelines that provide treatment protocols for NSCLC and SCLC.

Standard of care for stage I and II NSCLC is multimodal and includes surgical resection. For patients in whom the risk of relapse is greater than 25%, neoadjuvant chemotherapy has survival benefits. Whether neoadjuvant immunotherapy confers long-term benefits is still being investigated in clinical trials. For patients who are not eligible for surgery, stereotactic body radiation therapy may improve survival.

NSCLC stage III is treated with chemotherapy, radiation, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy depending on tumor characteristics (e.g., the possibility of surgical resection) and patient factors (e.g., other medical conditions). Stage IV NSCLC requires systemic therapies, with local therapies generally used to improve symptoms; however, when metastases are limited in number and organ, local therapies may improve outcomes.

Treatment of limited-stage SCLC includes the use of chemotherapy, radiation, and prophylactic cranial radiation to prevent brain metastases. Most patients with SCLC develop resistance to chemotherapy, leading to recurrence, which is usually fatal. Extensive-stage SCLC is treated with chemotherapy and immunotherapy, although radiation may be used for some cases.

New and Emerging Treatments

New and emerging treatments for cancer are being developed for surgery, radiation, and systemic approaches. The committee defined new treatments as therapeutic approaches adopted recently in clinical practice or established treatments for one cancer that are being studied for other cancers, and emerging therapies as novel therapeutic approaches under scientific investigation that have demonstrated promising results in early stage research, but have not yet been accepted as a standard of care. In addition to considering new and emerging treatments for breast cancer and lung cancer, the committee also considered advances in treatment for colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, liver and bile duct cancers, leukemias, lymphomas, multiple myeloma, ovarian cancer, head and neck cancers, and melanoma.

New surgical approaches such as minimally invasive techniques with robotics and laparoscopic surgery have been developed to reduce adverse effects related to surgery, particularly to reduce lymphedema following lymph node dissection. Other surgical approaches to minimize adverse effects include breast-conserving surgery with oncoplastic construction.

The latest radiation techniques are focused on delivery strategies to reduce acute and long-term adverse effects. These new techniques include isotopes (e.g., charged particle therapy) and delivery strategies (e.g., FLASH radiotherapy) to reduce adverse effects in adjacent organs and soft tissues.

A growing number of new systemic treatments include targeted therapies, antibody drug conjugates, and immunotherapies. Many targeted therapies, such as PARP inhibitors, are standard of care for one cancer, but are emerging therapies for other cancers. Many targeted therapies lose their effectiveness over time and may be used for only a small set of cancers. However, treatments that focus on enhancing the immune system may be applicable to a greater variety of cancers. Immunotherapies may be preventative or therapeutic vaccines, adoptive cellular therapies such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, and immune checkpoint inhibitors such as programmed cell death ligand-1. Antibody drug conjugates, in which a highly toxic chemotherapeutic agent is linked to a monoclonal antibody, may improve the effectiveness of the agent and reduce its toxicity. The long-term and late-onset effects of these new therapies, particularly immunotherapies, for different cancers and populations are poorly understood.

Conclusions

- Many systemic therapies beyond chemotherapy, such as immunotherapy and targeted therapy, are now used to treat localized and advanced cancer.

- Immunotherapies represent the most important and transformative classes of new and emerging cancer treatments, as these treatments can lead to prolonged disease-free survival for some cancers that respond poorly to conventional treatments.

- Although many new and emerging cancer therapies are improving survival, their long-term and late-onset effects are poorly understood.

- Some newer treatment approaches are focused on reducing or correcting the toxicity and morbidity of standard treatments (e.g., reduction in the extent of axillary surgery, less invasive surgical procedures, or use of proton radiation therapy). In time, these may become the standard of care as their effectiveness and safety become more evident.

PROGNOSIS

Prognosis is commonly used to indicate what patients may expect with respect to the trajectory of their cancer and how long they might expect to live. The committee uses the term prognosis to encompass a variety of cancer outcomes including survival, recurrence, remission, the likelihood of and surveillance for the development of new primary cancers, and the occurrence and persistence of cancer-related impairments that may lead to functional limitations in activities of daily living and quality of life. Cancer survivors may live for years, but the debilitating effects of the cancer itself and its various treatments may make functioning difficult.

The prognosis for each type and even subtype of cancer is highly variable and depends on many factors, including the cancer diagnosis (e.g., tumor staging and biomarkers), the quality of care the patient receives, performance status, and the presence of comorbidities. An earlier stage at diagnosis is associated with improved outcomes for most cancers, and patient self-reported outcomes are strong indicators for overall survival across varying cancer diagnoses and among different populations.

Many survivors with no evidence of cancer may later experience a cancer recurrence. In the case of solid tumor cancers, recurrence can be either local or distant. Cancer patients who have been successfully treated are also at risk for the development of new or subsequent primary cancers that may occur anywhere from months to years after the original cancer has been treated. The cumulative incidence of new primary malignancies approaches 15% at 20 years after the diagnosis of initial primary cancer.

Current breast cancer survivors, including many with metastatic disease, have a longer life expectancy compared with prior cohorts as a result of improved treatments. Triple-negative breast cancer is more likely to recur than the other subtypes, with an 85% 5-year stage I cancer-specific survival compared with 94–99% for HR-positive and HER2-positive cancers. The most commonly diagnosed breast cancer is HR-positive/HER2-negative. Once breast cancer metastasizes, the 5-year survival is estimated to be 27%; however, metastatic breast cancer—generally thought to be incurable—is being increasingly treated as a chronic disease.

Lung cancer is one of the deadliest cancers with more than half of people dying within 1 year of diagnosis. The 5-year survival rate for all-stage NSCLC is 24% and 6% for SCLC. The high mortality rate is due to most people being diagnosed with advanced disease and to the high recurrence rate even for those diagnosed in early stages of the disease. If diagnosed early, the 5-year survival rates increase to 57% for NSCLC, but only 16% for SCLC.

Conclusions

- The cancer care trajectory for each patient and survivor is unique and depends on the characteristics of his or her cancer, its treatment, and factors such as age and comorbidities.

- The 5-year survival for people with early-stage breast cancer (specifically, stage I, hormone-positive, and HER2-negative), the most commonly diagnosed breast cancer, is excellent, at 94–99%.

- Changes in the treatment of NSCLC in recent years have produced improvements in survival. Some patients with metastatic NSCLC are now achieving 5-year survival; however, this longevity is still extremely rare for SCLC.

CANCER-RELATED IMPAIRMENTS

SSA’s Listing of Impairments is focused predominately on terminal and metastatic cancers with a high likelihood of death and does not include any cancer-related impairments that may lead to functional limitations, other than secondary lymphedema that is caused by anticancer therapy for breast cancer. Assessing cancer-related impairments and associated functional limitations is a complex task and includes evaluating patient-reported outcomes in addition to numerous functional assessment tools for physical and psychologic impairments at several points in the cancer trajectory, including at time of diagnosis, at completion of active treatment, and periodically during the rest of the survivor’s life. The time course and severity of impairments from cancer and its treatments can vary and can extend throughout the cancer trajectory, from presenting symptoms and diagnosis, through treatment, to long-term survivorship. Table S-1 lists the cancer-related impairments considered by the committee to be among the most common, disabling, and difficult to manage when the treatment goal is improved function.

Substantial impairments associated with breast cancer and its treatments include pain, lymphedema, fatigue, depression, cognitive impairment, and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Impairments associated with lung cancer and its treatments include respiratory problems, fatigue, pain, neuropathy, ototoxicity, and psychological distress. Impairments associated with other common cancers include cachexia (e.g., for gastrointestinal cancers) and graft-versus-host disease (e.g., for leukemias).

Data are lacking on the prevalence and impact of these impairments on survivors’ long-term functioning. Impairments contributing to functional limitations can be assessed with standardized, validated tools when appropriate; however, for many impairments including pain, depression, and fatigue, validated self-report instruments are the primary diagnostic tools.

TABLE S-1 Impairments Considered in This Report, Impairment Causes, and When the Impairment Might Occur

| Impairment | Impairment Causes | Occurrence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Process | Cancer Treatment | Acute | Long-Term | Late-Onset | |

|

Pain |

• | • | • | • | |

|

Cancer-related fatigue |

• | • | • | • | |

|

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy |

• | • | • | ||

|

Lymphedema |

• | • | • | ||

|

Cachexia |

• | • | |||

|

Cardiotoxicity |

• | • | • | • | |

|

Cognitive impairments |

• | • | • | • | • |

|

Depression and anxiety |

• | • | • | • | |

|

Gastrointestinal impairments |

• | • | • | • | • |

|

Graft-versus-host disease |

• | • | • | ||

|

Musculoskeletal impairments |

• | • | • | • | • |

|

Pulmonary toxicity |

• | • | • | • | |

|

Sleep disturbances |

• | • | • | • | |

Key factors that alter the potential incidence and severity of cancer-related impairments include comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) and symptom clusters. For example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can cause shortness of breath and limit a survivor’s participation in rehabilitation treatments. Symptom clusters—two or more concurrent symptoms that are related and may or may not have a common cause, such as fatigue and pain—can have significant and synergistic effects on cancer-related impairments and functional limitations.

Although there are pharmacologic treatments for some impairments, there are also a number of single and multimodal nonpharmacologic interventions that are effective. Exercise and physical activity, rehabilitation (physical and occupational therapy, physiatry, and speech and language therapy), and psychological and emotional interventions are being increasingly recommended by clinicians. These nonpharmacologic interventions, however, are currently underused and underprescribed for cancer-related impairments.

Conclusions

- In determining the ability of a person to engage in substantial gainful activity, it is necessary to consider cancer-related impairments arising from the disease itself, those arising from cancer treatments, and those associated with or exacerbated by pre-existing and treatment-related comorbidities.

- Regular assessment and re-assessment of functional status throughout the cancer care trajectory are warranted given the dynamic impacts of cancer-related acute, long-term, and late-onset impairments that may result in functional limitations.

- There are various evidence-based exercise and rehabilitation interventions that can mitigate these impairments but, in general, they are underprescribed and underused.

- The development of and prognosis for impairments associated with cancer and its treatment, even early-stage cancer, are highly variable and depend on many individual characteristics and the specific treatments the patient receives.

- Many cancer-related impairments may result from breast cancer and its treatment, especially pain, fatigue, cognitive complaints, neuropathy, psychological issues, and lymphedema, which are often untreated and may lead to persistent functional limitations.

- Survivors of lung cancer may have cancer-related impairments as a consequence of their cancer and its treatment. The high risk of lung cancer recurrence, metastases, or the development of new primary cancers, and the major comorbid conditions often associated with smoking and aging, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, can increase the number and severity of any impairments.

- SSA’s current cancer disability listings for adults focus on the most severe terminal and metastatic cancers with a high likelihood of death, and will not always capture more complex cancer cases that necessitate functional analysis. Such complex cases have become more common because of the growing number of cancer survivors who are benefiting from life-prolonging cancer treatments but who also may have impairments and functional limitations from those treatments.1

SURVIVORSHIP CARE

Survivorship care provides cancer-related and supportive interventions that address the individual needs of each survivor. It includes a cancer

___________________

1 This text has changed since the release of the prepublication version of this report to clarify SSA’s current disability listings and why the listings might need to change in the future due to the complex nature of cancers and cancer treatments.

care team that is patient and caregiver focused, and ranges from oncology specialists of various disciplines, primary care clinicians, and rehabilitation specialists to nurses, pharmacists, mental health professionals, nutritionists, social workers, and spiritual counselors. Communication among and coordination between care team members can be facilitated by electronic health records, but patient-reported outcomes, such as pain and mental distress, are not regularly included in electronic health records, making assessment of impairments difficult.

Challenges for survivorship care include the delivery of cancer treatments in the ambulatory or outpatient setting (rather than the inpatient setting) where fewer resources are available. For example, care team members may not be co-located, requiring the survivor to travel between facilities.

Efforts including certification programs are under way to expand training opportunities for health care providers to ensure that the long-term needs of cancer survivors are identified and met during and after treatment.

Conclusions

- Survivorship care is complex and requires coordination and communication among the patient, caregivers, and all members of the care team. Enabling and supporting patient self-management is a critical component of survivorship care.

- Challenges to providing optimal survivorship care include the availability and education of clinicians, and electronic health records that do not adequately collect survivorship information.

The cancer diagnosis and treatment landscape has changed dramatically in the past two decades, reflecting basic science discoveries in genetics and immunology that have translated into improvements in diagnosis and treatments for many types of cancer. These discoveries mean that pathologists now identify the unique expression of a tumor’s genetic and immune features on an initial biopsy, so that this information, along with the anatomic extent of the cancer, can chart a personalized treatment plan for the patient. While these advances have contributed to improvements in cancer treatment outcomes, much less is known about the long-term and late-onset effects of these treatments compared with the conventional surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation approaches that have been used for more than 50 years. Managing cancer-related impairments and functional limitations as part of a patient-centered, survivorship care program should be a lifelong process.