7

Educating Nurses for the Future

You cannot transmit wisdom and insight to another person. The seed is already there. A good teacher touches the seed, allowing it to wake up, to sprout, and to grow.

—Thich Nhat Hanh, global spiritual leader and peace activist

Throughout the coming decade, it will be essential for nursing education to evolve rapidly in order to prepare nurses who can meet the challenges articulated in this report with respect to addressing social determinants of health (SDOH), improving population health, and promoting health equity. Nurses will need to be educated to care for a population that is both aging, with declining mental and physical health, and becoming increasingly diverse; to engage in new professional roles; to adapt to new technologies; to function in a changing policy environment;

and to lead and collaborate with professionals from other sectors and professions. As part of their education, aspiring nurses will need new competencies and different types of learning experiences to be prepared for these new and expanded roles. Also essential will be recruiting and supporting diverse students and faculty to create a workforce that more closely resembles the population it serves. Given the growing focus on SDOH, population health, and health equity within the public health and health care systems, the need to make these changes to nursing education is clear. Nurses’ close connection with patients and communities, their role as advocates for well-being, and their placement across multiple types of settings make them well positioned to address SDOH and health equity. For future nurses to capitalize on this potential, however, SDOH and equity must be integrated throughout their educational experience to build the competencies and skills they will need.

The committee’s charge included examining whether nursing education provides the competencies and skills nurses will need—the capacity to acquire new competencies, to work outside of acute care settings, and to lead efforts to build a culture of health and health equity—as they enter the workforce and throughout their careers. A thorough review of the current status and future needs of nursing education in the United States was beyond the scope of this study, but in this chapter, the committee identifies priorities for the content and nature of the education nurses will need to meet the challenge of addressing SDOH, advancing health equity, and improving population health. Nursing education is a lifelong pursuit; nurses gain knowledge and skills in the classroom, at work, through continuing professional development, and through other formal and informal mechanisms (IOM, 2016b). While the scope of this study precluded a thorough discussion of learning outside of nursing education programs, readers can find further discussion of lifelong learning in A Framework for Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants of Health (IOM, 2016b), Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions (IOM, 2010), and Exploring a Business Case for High-Value Continuing Professional Development: Proceedings of a Workshop (NASEM, 2018a).

To change nursing education meaningfully so as to produce nurses who are prepared to meet the above challenges in the decade ahead will require changes in four areas: what is taught, how it is taught, who the students are, and who teaches them. This chapter opens with a description of the nursing education system and the need for integrating equity into education, and then examines each of these four areas in turn:

- domains and competencies for equity,

- expanded learning opportunities,

- recruitment of and support for diverse prospective nurses, and

- strengthening and diversification of the nursing faculty.

In addition to changes in these specific areas, there is a need for a fundamental shift in the idea of what constitutes a “quality” nursing education. Currently, National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX) pass rates are used as the primary indicator of quality, along with graduation and employment rates (NCSBN, 2020a; O’Lynn, 2017). This narrow focus on pass rates has been criticized for diverting time and attention away from other goals, such as developing student competencies, investing in faculty, and implementing innovative curricula (Giddens, 2009; O’Lynn, 2017; Taylor et al., 2014). In addition, the NCLEX is heavily focused on acute care rather than on such areas of nursing as primary care, disease prevention, SDOH, and health equity (NCSBN, 2019). In response to such concerns about the NCLEX, the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) conducted a study to identify additional quality indicators for nursing education programs; indicators were identified in the areas of administration, program director, faculty, students, curriculum and clinical experiences, and teaching and learning resources (Spector et al., 2020). To realize the committee’s vision for nursing education, it will be necessary for nursing schools, accreditors, employers, and students to look beyond NCLEX pass rates and include these types of indicators in the assessment of a quality nursing education.

OVERVIEW OF NURSING EDUCATION

Nurses are educated at universities, colleges, hospitals, and community colleges and can follow a number of educational pathways. Table 7-1 identifies the various degrees that nurses can hold, and describes the programs that lead to each degree and the usual amount of time required to complete them. In 2019, there were more than 200,000 graduates from baccalaureate, master’s, and doctoral nursing programs in the United States and its territories, including 144,659 who received a baccalaureate degree (AACN, 2020a) (see Table 7-2).

Nursing programs are nationally accredited by the Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing (ACEN); the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE); the Commission for Nursing Education and Accreditation (CNEA); and other bodies focused on specialty areas of nursing, such as midwifery. Graduating registered nurses (RNs) seek licensure as nurses through state boards, and take examinations administered by the NCSBN as graduates with their first professional degree and then as specialists with certification exams offered through specialty organizations. These bodies set minimum standards for nursing programs and establish criteria for certification and licensing, faculty qualifications, course offerings, and other features of nursing programs (Gaines, n.d.).

TABLE 7-1 Pathways in Nursing Education

| Type of Degree | Description of Program |

|---|---|

| Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing (PhD) and Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) | PhD programs are research focused, and graduates typically teach and conduct research, although these roles are expanding. DNP programs are practice focused, and graduates typically serve in advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) roles and other advanced clinical positions, including faculty positions. Time to completion: 3−5 years. Bachelor of science in nursing (BSN)- or master of science in nursing (MSN)-to-nursing doctorate options available. |

| Master’s Degree in Nursing (MSN/MS) | Prepares APRNs: nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, nurse midwives, and nurse anesthetists, as well as clinical nurse leaders, educators, administrators, and other areas or roles. Time to completion: 18−24 months. Three years for associate’s degree in nursing (ADN)-to-MSN option. |

| Accelerated BSN or Master’s Degree in Nursing | Designed for students with a baccalaureate degree in another field. Time to completion: 12−18 months for BSN and 3 years for MSN, depending on prerequisite requirements. |

| Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) Registered Nurse (RN) | Educates nurses to practice the full scope of nursing responsibilities across all health care settings. Curriculum provides additional content in physical and social sciences, leadership, research, and public health. Time to completion: 4 years or up to 2 years for ADN/diploma RNs and 3 years for licensed practical nurses (LPNs), depending on prerequisite requirements. |

| Associate’s Degree in Nursing (ADN) (RN) and Diploma in Nursing (RN) | Prepares nurses to provide direct patient care and practice within the legal scope of nursing responsibilities in a variety of health care settings. Offered through community colleges and hospitals. Time to completion: 2 to 3 years for ADN (less in the case of LPN entry) and 3 years for diploma (all hospital-based training programs), depending on prerequisite requirements. |

| Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN)/Licensed Vocational Nurse (LVN) | Trains nurses to provide basic care (e.g., take vital signs, administer medications, monitor catheters, and apply dressings). LPN/LVNs work under the supervision of physicians and RNs. Offered by technical/vocational schools and community colleges. Time to completion: 12−18 months. |

SOURCES: Adapted from IOM, 2011 (AARP, 2010. Courtesy of AARP. All rights reserved).

The Need for Nursing Education on Social Determinants of Health and Health Equity

A report of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) from nearly two decades ago asserts that all health professionals, including nurses, need to “understand determinants of health, the link between medical care and healthy populations, and professional responsibilities” (IOM, 2003, p. 209). The literature is replete with calls for all nurses to understand concepts associated with health equity, such as disparities, culturally competent care, equity, and social justice. For example, Morton and colleagues (2019) identify essential content to prepare nurses for

TABLE 7-2 Number of Graduates from Nursing Programs in the United States and Territories, 2019

| Type of Degree or Certificate | Number of Graduates |

|---|---|

| Licensed practical nurse (LPN)/licensed vocational nurse (LVN)a | 48,234 |

| Associate’s degree in nursing (ADN)a | 84,794 |

| Generic entry-level baccalaureate (includes accelerated BSN and LPN-to-BSN) | 78,394 |

| RN-to-baccalaureate programs | 66,265 |

| Master’s | 49,895 |

| Doctor of nursing practice (DNP) | 7,944 |

| PhD | 804 |

| Postdoctoral | 57 |

a Number of first-time NCLEX test takers, which is proxy for new graduates (NCSBN, 2020a).

SOURCE: AACN, 2020a.

community-based practice, including SDOH, health disparities/health equity, cultural competency, epidemiology, community leadership, and the development of enhanced skills in community-based settings. O’Connor and colleagues (2019) call for an inclusive educational environment that prepares nurses to care for diverse patient populations, including the study of racism’s impacts on health from the genetic to the societal level, systems of marginalization and oppression, critical self-reflection, and preparation for lifelong learning in these areas. And Thornton and Persaud (2018) state that the content of nursing education should include instruction in cultural sensitivity and culturally competent care, trauma-informed care and motivational interviewing, screening for social needs, and referring for services. These calls align with the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA’s) most recent strategic plan, which prioritizes the development of a health care workforce that is able to address current and emerging needs for improving equity and access (HRSA, 2019). Additionally, recommendations of the National Advisory Council on Nurse Education and Practice (NACNEP) (2016) include that population health concepts be incorporated into nursing curriculum and that undergraduate programs create partnerships with HRSA, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the Indian Health Service (IHS), agencies that serve rural and frontier areas, to increase students’ exposure to different competencies, experiences, and environments.

In concert with these perspectives and recommendations, nursing organizations have developed guidelines for how nursing education should prepare nurses to work on health equity issues and address SDOH. In 2019, the National League for Nursing (NLN) issued a Vision for Integration of the Social Determinants of Health into Nursing Education Curricula, which describes the importance of SDOH to the mission of nursing and makes recommendations for how SDOH should be integrated into nursing education (see Box 7-1).

As described in Chapter 9, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing’s (AACN’s) Essentials1 provides an outline for the necessary curriculum content and expected competencies for graduates of baccalaureate, master’s, and doctor of nursing practice (DNP) programs. Essentials identifies “Clinical Prevention and Population Health” as one of the nine essential areas of baccalaureate nursing education. Among other areas of focus, Essentials calls for baccalaureate programs to prepare nurses to

- collaborate with other health care professionals and patients to provide spiritually and culturally appropriate health promotion and disease and injury prevention interventions;

- assess the health, health care, and emergency preparedness needs of a defined population;

- collaborate with others to develop an intervention plan that takes into account determinants of health, available resources, and the range of activities that contribute to health and the prevention of illness, injury, disability, and premature death;

- participate in clinical prevention and population-focused interventions with attention to effectiveness, efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and equity; and

- advocate for social justice, including a commitment to the health of vulnerable populations and the elimination of health disparities.

Curriculum content and expected competencies laid out in Essentials for master’s- and DNP-level nursing education also address SDOH, disparities, equity, and social justice (AACN, 2006, 2011). While Essentials only guides baccalaureate, master’s, and DNP programs, the document’s emphasis on health equity and SDOH demonstrates the importance of these topics to the nursing profession as a whole.

As of 2020, AACN has been shifting toward a competency-based curriculum. As part of this effort, AACN published a draft update to Essentials that identifies 10 domains for nursing education: knowledge for nursing practice; person-centered care; population health; scholarship for nursing discipline; quality and safety; interprofessional partnerships; systems-based practice; informatics and health care technologies; professionalism; and personal, professional, and leadership development. Within these 10 domains are specific competencies that AACN believes are essential for nursing practice (AACN, 2020b), including

- engage in effective partnerships,

- advance equitable population health policy,

- demonstrate advocacy strategies,

___________________

1 See https://www.aacnnursing.org/Education-Resources/AACN-Essentials (accessed April 13, 2021).

- use information and communication technologies and informatics processes to deliver safe nursing care to diverse populations in a variety of settings, and

- use knowledge of nursing and other professions to address the health care needs of patients and populations.

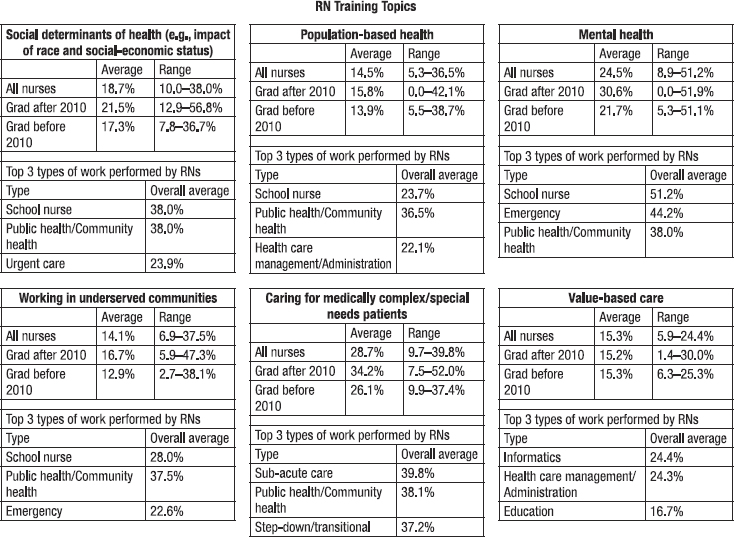

Nurses themselves have also indicated the need for more education and training on these topics. The 2018 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (NSSRN) asked the question, “As of December 31, 2017, what training topics would have helped you do your job better?” Figure 7-1 shows the percentage of six different training topics that RNs said would help them do their job better. Overall, RNs working in schools, public health, community health, and emergency and urgent care were more likely than RNs working in all other employment settings listed in Figure 7-1 to indicate that they could have done their job better if they had received training in SDOH, population health, working in underserved communities, caring for individuals with complex health and social needs, and especially mental health. These results could reflect RNs encountering increasingly complex individuals and populations, rising numbers of visits and caseloads, the fact that the RNs working in these settings frequently provide

SOURCE: Calculations based on the 2018 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (HRSA, 2020).

care for people facing multiple social risk factors that harm their health and well-being, or inadequacy of the training in these areas that RNs had received. RNs—particularly those working in informatics, health care management and administration, and education—also indicated that training in value-based care would have been helpful. Additionally, RNs who had graduated after 2010 were more likely than those who had graduated before then to indicate that they could have done their job better with training across all of these topics.

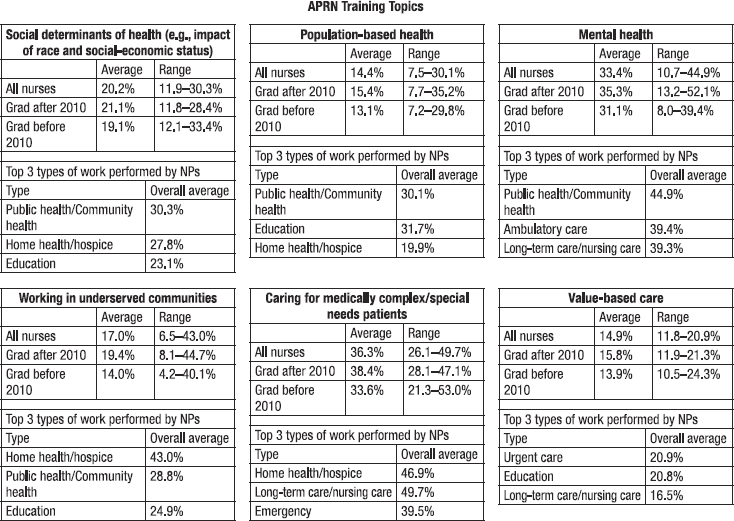

Nurse practitioners (NPs) have also indicated the need for more training in SDOH. In response to the 2018 NSSRN question described above, NPs working in public health and community health, emergency and urgent care, education, and long-term care reported that they could have done their job better if they had received training in SDOH, mental health, working in underserved communities, and providing care for medically complex/special needs. Across all types of practice settings, one-third felt that training in mental health issues would have helped them do their job better, while very few NPs indicated that training in value-based care would have been helpful. Additionally, NPs who had graduated since 2010 were more likely than those who had graduated before then to indicate that they would have benefited from training in these topics. Figure 7-2 shows the percentage of six different training topics that NPs mentioned would have helped them do their job better.

SOURCE: Calculations based on the 2018 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (HRSA, 2020).

The Need for Integration of Social Determinants of Health and Health Equity into Nursing Education

Despite guidelines from both the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) and the National League for Nursing (NLN) and numerous calls for including equity, population health, and SDOH in nursing education, SDOH and related concepts are not currently well integrated into undergraduate and graduate nursing education. Nor has the degree to which nurses are prepared and educated in these areas been studied systematically (NACNEP, 2019; Tilden et al., 2018). The committee was unable to locate a central repository of information about the coursework and other educational experiences available to nursing students across types of programs and institutions, or any other source of systematic analysis of nursing curricula. This lack of information about nursing preparation programs limits the conclusions that can be drawn about them. Thus, the discussion in this chapter is based on the assumption that some nursing programs are likely already pursuing many of the goals identified herein, but that this critically important content is not yet standard practice throughout nursing education.

One way to explore whether and how health equity and related concepts are currently integrated into nursing education is to look at accreditation standards. While the standards do not detail every specific topic to be covered in nursing curricula, they do set expectations, convey priorities, and identify important areas of study. For example, the accreditation standards of the CCNE state that advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) programs must include study of advanced physiology, advanced health assessment, and advanced pharmacology (CCNE, 2018). Accreditation standards could be used to prioritize the inclusion of health equity and SDOH in nursing curriculum; however, this is not currently the case. The CCNE standards state that accredited programs must incorporate the AACN Essentials into their curricula, and while these standards do not specifically mention equity, SDOH, or other relevant concepts (CCNE, 2018), that is expected to change to correspond with the updates to the Essentials described previously (see Box 7-1). CNEA’s accreditation standards likewise include no mention of population health, SDOH, or health equity (NLN, 2016), although a more recent document from NLN makes a strong case for the integration of SDOH into nursing education curricula (NLN, 2019). ACEN’s associate’s and baccalaureate standards call for inclusion of “cultural, ethnic, and socially diverse concepts” in the curriculum; the master’s and doctoral standards require that curriculum be “designed so that graduates of the program are able to practice in a culturally and ethnically diverse global society,” but do not address health equity, population health, or SDOH.

Another approach for examining the inclusion of these concepts in nursing education is to look at exemplar programs. As part of the Future of Nursing: Campaign for Action, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation commissioned a study of best practices in nursing education to support population health (Campaign for

Action, 2019b). That report notes that although many nursing programs reported including population health content in their curriculum, few incorporated the topic substantially. However, the report also identifies exemplars of programs with promising population health models. These exemplars include Oregon Health & Science University, which incorporates population health throughout the curriculum as a key competency; Rush University, which incorporates cultural competence throughout the curriculum; and Thomas Jefferson University, which offers courses in health promotion, population health, health disparities, and SDOH. NACNEP has also examined exemplars of nursing programs that incorporate health equity and SDOH into their curricula (NACNEP, 2019). The programs highlighted include the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, which has a course called Case Study—Addressing the Social Determinants of Health: Community Engagement Immersion (Schroeder et al., 2019). This course offers experiential learning opportunities that focus on SDOH in vulnerable and underserved populations and helps students design health promotion programs for these communities. The school also offers faculty education in SDOH.

As far as the committee was able to determine, most programs include content on SDOH in community or public health nursing courses. However, this material does not appear to be integrated thoroughly into the curriculum in the majority of programs, nor could the committee identify well-established designs for curricula that address this content outside of community health rotations (Campaign for Action, 2019b; Storfjell et al., 2017; Thornton and Persaud, 2018). In the committee’s view, a single course in community and/or public health nursing is insufficient preparation for creating a foundational understanding of health equity and for preparing nurses to work in the wide variety of settings and roles envisioned in this report. Ideally, education in these concepts would be integrated throughout the curriculum to give nurses a comprehensive understanding of the social determinants that contribute to health inequities (NACNEP, 2019; NLN, 2019; Siegel et al., 2018). Moreover, academic content alone is insufficient to provide students with the knowledge, skills, and abilities they need to advance health equity; rather, expanded opportunities for experiential and community learning are critical for building the necessary competencies (Buhler-Wilkerson, 1993; Fee and Bu, 2010; NACNEP, 2016; Sharma et al., 2018). All those involved in nursing education—administrators, faculty, accreditors, and students—need to understand that health equity is a core component of nursing, no less important than alleviating pain or caring for individuals with acute illness. Graduating students need to understand and apply knowledge of the impact of such issues as classism, racism, sexism, ageism, and discrimination and to be empowered to advocate on these issues for people who they care for and communities.

As currently constituted, then, nursing education programs fall short of conveying this information sufficiently in the curriculum or through experiential learning opportunities. Yet, the existing evidence on what nursing education programs offer is scant. Research is therefore needed to assess whether and how

many nursing programs are offering sufficient coursework and learning opportunities related to SDOH and health equity and to examine the extent to which graduating nurses have the competencies necessary to address these issues in practice.

The Need for BSN-Prepared Nurses

The 2011 The Future of Nursing report includes the recommendation that the percentage of nurses who hold a baccalaureate degree or higher be increased to 80 percent by 2020. The report gives several reasons for this goal, including that baccalaureate-prepared nurses are exposed to competencies including health policy, leadership, and systems thinking; they have skills in research, teamwork, and collaboration; and they are better equipped to meet the increasingly complex demands of care both inside and outside the hospital (IOM, 2011, p. 170). In 2011, 50 percent of employed nurses held a baccalaureate degree or higher; as of 2019, that proportion had increased to 59 percent (Campaign for Action, 2020). Both the number of baccalaureate programs and program enrollment have increased substantially since 20112 (AACN, 2019a), and the number of RNs who went on to receive BSNs in RN-to-BSN programs increased 236 percent between 2009 and 2019 (Campaign for Action, n.d.). However, the goal of 80 percent of nurses holding a BSN was still not achieved by 2020, for a number of reasons. Although the proportion of new graduates with a BSN is higher than the proportion of existing nurses with a BSN, the percentage of new graduates joining the nursing workforce each year is small. Given this ratio, it would have been “extraordinarily difficult” to achieve the goal of 80 percent by 2020 (IOM, 2016a; McMenamin, 2015). Nurses already in the workforce face barriers to pursuing a BSN, including time, money, work–life balance, and a perception that additional postlicense education is not worth the effort (Duffy et al., 2014; Spetz, 2018). Moreover, schools and programs have limited capacity for first-time nursing students and ADN, LPN nurses, or RNs without BSN degrees (Spetz, 2018).

Nonetheless, the goal of achieving a nursing workforce in which 80 percent of nurses hold a baccalaureate degree or higher remains relevant, and continuing efforts to increase the number of nurses with a BSN are needed. Across the globe, the proportion of BSN-educated nurses is correlated with better health outcomes (Aiken et al., 2017; Baker et al., 2020), and there are clear differences as well as similarities between associate’s degree in nursing (ADN) programs and BSN programs. In particular, BSN programs are more likely to cover topics relevant to liberal education, organizational and systems leadership, evidence-based practice, health care policy, finance and regulatory environments, interprofessional collaboration, and population health (Kumm et al., 2014). Accelerated, nontraditional, and other pathways to the BSN degree are discussed later in this chapter.

___________________

2 See Chapter 3 for demographic information on employed nurses in the United States.

The Need for PhD-Prepared Nurses

There are two types of doctoral degrees in nursing: the PhD and the DNP. The former is designed to prepare nurse scientists to conduct research, whereas the latter is a clinically focused doctoral degree designed to prepare graduates with advanced competencies in leadership and management, quality improvement, evidence-based practice, and a variety of specialties. PhD-prepared nurses are essential to the development of the research base required to support evidence-based practice and add to the body of nursing knowledge, and DNP-educated nurses play a key role in translating evidence into practice and in educating nursing students in practice fundamentals (Tyczkowski and Reilly, 2017) (see Chapter 3 for further discussion of the role of DNPs).

The number of nurses with doctoral degrees has grown rapidly since the 2011 The Future of Nursing report was published (IOM, 2011). As a proportion of doctorally educated nurses, however, the number of PhD graduates has remained nearly flat. In 2010, there were 1,282 graduates from DNP programs and 532 graduates receiving a PhD in nursing. By 2019, the number of DNP graduates had grown more than 500 percent to 7,944, while the number of PhD graduates had grown about 50 percent to 804 (AACN, 2011, 2020a).

The slow growth in PhD-prepared nurses is a major concern for the profession and for the nation, because it is these nurses who serve as faculty at many universities and who systematically study issues related to health and health care, including the impact of SDOH on health outcomes, health disparities, and health equity. PhD-prepared nurses conduct research on a wide variety of issues relating to SDOH, including the effect of class on children’s health; linguistic, cultural, and educational barriers to care; models of care for older adults aging in place; and gun violence (Richmond and Foman, 2018; RWJF, 2020; Szanton et al., 2014). Nurse-led research provided evidence-based solutions in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic for such challenges as the shift to telehealth care, expanding demand for health care workers, and increased moral distress (Lake, 2020). However, Castro-Sánchez and colleagues (2021) note a dearth of nurse-led research specifically related to COVID-19; they posit that this gap can be attributed to workforce shortages, a lack of investment in clinical academic leadership, and the redeployment of nurses into clinical roles. More PhD-prepared nurses are needed to conduct research aimed at improving clinical and community health, as well as to serve as faculty to educate the next generation of nurses (Broome and Fairman, 2018; Fairman et al., 2020; Greene et al., 2017).

Nursing practice is dependent on a robust pipeline of research to advance evidence-based care, inform policy, and address the health needs of people and communities (Bednash et al., 2014). The creation of the BSN-to-PhD direct entry option has helped produce more research-oriented nurse faculty (Greene et al., 2017), but time, adequate faculty mentorship, mental health issues, and financial hardships, including the cost of tuition, are barriers for nurses pursuing these

advanced degrees (Broome and Fairman, 2018; Fairman et al., 2020; Squires et al., 2013). One approach for increasing the number of PhD-prepared nurses is the Future of Nursing Scholars program, which successfully graduated approximately 200 PhD students through an innovative accelerated 3-year program (RWJF, 2021). Similar programs have been funded by such foundations as the Hillman Foundation and Jonas Philanthropies to help stimulate the pipeline, build capacity (especially in health policy) among graduates, and model innovative curricular approaches (Broome and Fairman, 2018; Fairman et al., 2020).

DOMAINS AND COMPETENCIES FOR EQUITY

As noted earlier, a number of existing recommendations specify what nurses need to know to address SDOH and health inequity in a meaningful way. In addition, the Future of Nursing: Campaign for Action surveyed and interviewed faculty and leaders in nursing and public health, asking about core content and competencies for all nurses (Campaign for Action, 2019b). Respondents specifically recommended that nursing education cover seven areas:

- policy and its impact on health outcomes;

- epidemiology and biostatistics;

- a basic understanding of SDOH and illness across populations and how to assess and intervene to improve health and well-being;

- health equity as an overall goal of health care;

- interprofessional team building as a key mechanism for improving population health;

- the economics of health care, including an understanding of basic payment models and their impact on services delivered and outcomes achieved; and

- systems thinking, including the ability to understand complex demands, develop solutions, and manage change at the micro and macro system levels.

Drawing on all of these recommendations, guidelines, and perspectives, as well as looking at the anticipated roles and responsibilities outlined in other chapters of this report, the committee identified the core concepts pertaining to SDOH, health equity, and population health that need to be covered in nursing school and the core knowledge and skills that nurses need to have upon graduation. For consistency with the language used by the AACN, these are referred to, respectively, as “domains” (see Box 7-2) and “competencies” (see Box 7-3). The domains in Box 7-2 are fundamental content that the committee believes can no longer be covered in public health courses alone, but need to be incorporated and applied by nursing students throughout nursing curricula. All nurses, regardless of setting or type of nursing, need to understand and be prepared to address the underlying barriers to better health in their practice.

The committee believes that incorporation of these domains and competencies can guide expeditious and meaningful changes in nursing education. The committee acknowledges that making room for these concepts will inevitably require eliminating some existing material in nursing education. The committee does not believe that it is the appropriate entity to identify what specific curriculum changes should be made; a nationwide evaluation will be needed to ensure that nursing curricula are preparing the future workforce with the skills and competencies they will need. The committee also acknowledges that nursing programs differ in length, and that an ADN program cannot cover SDOH equity to the same extent as a BSN program. The specific knowledge and skills a nurse will need will vary depending on her or his level of nursing education. For example, a nurse with a BSN may need to understand and be able to use the technologies that are relevant to his or her area of work (e.g., telehealth applications, electronic health records [EHRs], home monitors), while an APRN may need a deeper understanding of how to analyze health records in order to provide care and monitor health status for populations outside clinical settings.

Nonetheless, nursing education at all levels—from licensed practical nurse (LPN) to ADN to BSN and beyond—needs to incorporate and integrate the domains and competencies in Boxes 7-2 and 7-3 to the extent possible so as to develop knowledge and skills that will be relevant and useful to nurses and essential to achieving equity in health and health care. Given the relationship among SDOH, social needs, and health outcomes and the increasing focus of health care systems on addressing these community and individual needs, the domains and competencies identified here are essential to ensure that all nurses understand and can apply concepts related to these issues; work effectively with people, families, and communities across the spectrum of SDOH; promote physical, mental, and social health; and assume leadership and entrepreneurial roles to create solutions, such as by fostering partnerships in the health and social sectors, scaling successful interventions, and engaging in policy development. While none of the domains listed in Box 7-2 are new to nursing, the health inequities that have become increasingly visible—especially as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic—demand that these domains now be substantively integrated into the fabric of nursing education and practice.

Many sources highlight both the challenges faced by front-line graduates when confronted with these issues, and the reality that many nursing schools lack faculty members with the knowledge and competencies to educate nurses effectively on these issues (Befus et al., 2019; Effland et al., 2020; Hermer et al., 2020; Levine et al., 2020; Porter et al., 2020; Rosa et al., 2019; Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano, 2019). To remedy the latter gap, educators need to have a clear understanding of these issues and their links to both educational and patient outcomes (see the section below on strengthening and diversifying the nursing faculty). It is important to note as well that some of these topics, including the connections among implicit biases, structural racism, and health equity, may be difficult for educators and students to discuss (see Box 7-4).

Given the limited scope of this report, the committee has chosen to highlight three of the competencies from Box 7-3 in this section.3 The first is delivering person-centered care to diverse populations. As the United States becomes increasingly diverse, nurses will need to be aware of their own implicit biases and be able to interact with diverse patients, families, and communities with empathy and humility. The second is learning to collaborate across professions, disciplines, and sectors. As discussed previously in this report, addressing SDOH is necessarily a multisectoral endeavor given that these determinants go beyond health to include such issues as housing, education, justice, and the environment. The third is continually adapting to new technologies. Advances in technology are reshaping both health care and education, and making it possible for both to

___________________

3 For further discussion of domains and competencies, see AACN, 2020b; Campaign for Action, 2019b; IOM, 2016b; NACNEP, 2019; NLN, 2019; Thornton and Persaud, 2018.

be delivered in nontraditional settings and nontraditional ways. In the present context, technology can expand access to underserved populations of patients and students—for example, telehealth and online platforms can be used to connect with those living in rural areas—but it can also exacerbate existing disparities and inequities. Nurses need to understand both the promises and perils of technology, and be able to adapt their practice and learning accordingly.

Delivering Person-Centered Care and Education to Diverse Populations

As discussed in Chapter 2, people’s family and cultural background, community, and other experiences may have profound impacts on their health. Given the increasing diversity of the U.S. population, it is critical that nurses understand the impact of these factors on health, can communicate and connect with people of different backgrounds, and can be self-reflective about how their own beliefs and biases may affect the care they provide. To this end, the committee believes it is essential that nursing education include the concepts of cultural humility and implicit bias as a thread throughout the curriculum.

An integral part of learning about these concepts is an opportunity to reflect on what one is learning and to draw connections with past learning and experiences. Researchers have established that instruction that guides students in reflection helps reinforce skills and competencies (see, e.g., NASEM, 2018c). This idea has been explored in the context of education in health professions and has been identified as a valuable way to foster understanding of health equity and SDOH (IOM, 2016b; Mann et al., 2007). While the strategies, goals, and structure of such reflection may vary, the process in general helps learners in health care settings examine their own values, assumptions, and beliefs (El-Sayed and El-Sayed, 2014; Scheel et al., 2017). In the course of structured reflection, for example, students might consider how such issues as racism, implicit bias, trauma, and policy affect the care people receive and create conditions for poor health, or how their own experiences and identities influence the care they provide.

Cultural Humility

In recent years, the focus in discussions of patient care has shifted from cultural competency to cultural humility (Barton et al., 2020; Brennan et al., 2012; Kamau-Small et al., 2015; Periyakoil, 2019; Purnell et al., 2018; Walker et al., 2016). The concept of cultural competency has been interpreted by some as limited for a number of reasons. First, it implies that “culture” is a technical skill in which clinicians can develop expertise, and it can become a series of static dos and don’ts (Kleinman and Benson, 2006). Second, the concept of cultural competency tends to promote a colorblind mentality that ignores the role of power, privilege, and racism in health care (Waite and Nardi, 2017). Third,

cultural competency is not actively antiracist but instead leaves institutionalized structures of White privilege and racism intact (Schroeder and DiAngelo, 2010).

In contrast, cultural humility is defined by flexibility, a lifelong approach to learning about diversity, and a recognition of the role of individual bias and systemic power in health care interactions (Agner, 2020). Cultural humility is considered a self-evaluating process that recognizes the self within the context of culture (Campinha-Bacote, 2018). The concept of cultural humility can be woven into most aspects of nursing and interprofessional education. For example, case studies in which students learn about the experience of a particular disease or strategies for disease prevention can be designed to model culturally humble approaches in the provision of nursing care and the avoidance of stereotypical thinking (Foronda et al., 2016; Mosher et al., 2017). One effective approach to cultivating cultural humility is to accompany experiential learning opportunities or case studies with reflection that expands learning beyond skills and knowledge. This includes questioning current practices and proposing changes to improve the efficiency and quality of care, equality, and social justice (Barton et al., 2020; Foronda et al., 2013). Programs designed to develop nurses’ cultural sensitivity and humility, as well as cultural immersion programs, have been developed, and research suggests that such programs can effectively develop skills that strengthen nurses’ confidence in treating diverse populations, improve patient and provider relationships, and increase nurses’ compassion (Allen, 2010; Gallagher and Polanin, 2015; Sanner et al., 2010).

Implicit Bias

Implicit bias is an unconscious or automatic mental association made between members of a group and an attribute or evaluation (FitzGerald and Hurst, 2017). For example, a clinician may unconsciously view White patients as more medically compliant than Black patients (Sabin et al., 2008). These types of biases not only can have consequences for individual health outcomes (Aaberg, 2012; Linden and Redpath, 2011) but also may play a role in maintaining or exacerbating health disparities (Blair et al., 2011). There are many resources available for implicit bias awareness and training; for example, Harvard University offers a number of Implicit Association Tests (IATs), the Institute for Healthcare Improvement offers free online resources to address implicit bias, and the AACN offers implicit bias workshops for nurses (AACN, n.d.; Foronda et al., 2018).

Evidence on the use of implicit bias training is limited. One review of the use of an IAT in health professions education found that the test had contrasting uses, with some curricula using it as a measure of implicit bias and others using it to initiate discussions and reflection. The review found a dearth of research on the use of IATs; the authors note that the nature of implicit bias is highly complex and cannot necessarily be reduced to the “time-limited” use of an IAT (Sukhera et al., 2019). A systematic review of interventions designed to reduce implicit bias

found that many such interventions are ineffective, and some may even increase implicit biases. The authors note that while there is no clear path for reducing biases, the lack of evidence does not weaken the case for “implementing widespread structural and institutional changes that are likely to reduce implicit biases” (FitzGerald et al., 2019). One promising model is an intervention that helps participants break the “prejudice habit” (Devine et al., 2012). This multifaceted intervention, which includes situational awareness of bias, education about the consequences of bias, strategies for reducing bias, and self-reflection, has been shown to reduce implicit racial bias for at least 2 months (Devine et al., 2012). Clearly, more research is needed in this area.

Learning to Collaborate Across Professions, Disciplines, and Sectors

As discussed in Chapter 9, eliminating health disparities will require the active engagement and advocacy of a broad range of stakeholders working in partnership to address the drivers of structural inequities in health and health care (NASEM, 2017). In these efforts, nurses may lead or work with people from a variety of professions, disciplines, and sectors, including, for example, physicians, social workers, educators, policy makers, lawyers, faith leaders, government employees, community advocates, and community members. Working across sectors, especially as they relate to SDOH (food insecurity, transportation barriers, housing, etc.), is a critical competence. Collaboration among these types of stakeholders has multiple benefits, including broader expertise and perspective, the capacity to address wide-ranging social needs, the ability to reach underserved populations, and sustainability and alignment of efforts (see Chapter 9 for further discussion). A traditional nursing education, which focuses on what is taught rather than on building competencies, is unlikely to give students the understanding of broader social, political, and environmental contexts that is necessary for working in these types of strategic partnerships (IOM, 2016b). If nursing students are to be prepared to practice interprofessionally after graduation, they must be given opportunities to collaborate with others before graduation (IOM, 2013) and to build the competencies they will need for collaborative practice. The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) identified four core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice (IPEC, 2016). While these competencies were developed specifically to prepare students for interprofessional practice within health care, they are also applicable to broader collaborations among other professions, disciplines, and sectors both within and outside of health care:

- Work with individuals of other professions to maintain a climate of mutual respect and shared values.

- Use the knowledge of one’s own role and those of other professionals to appropriately assess and address the health care needs of patients and to promote and advance the health of populations.

- Communicate with patients, families, communities, and professionals in health and other fields in a responsive and responsible manner that supports a team approach to the promotion and maintenance of health and the prevention and treatment of disease.

- Apply relationship-building values and the principles of team dynamics to perform effectively in different team roles in planning, delivering, and evaluating patient/population-centered care and population health programs and policies that are safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable.

There are opportunities for nursing students to gain interprofessional and multisector collaborative competencies through both experiential learning in the community (discussed in detail below) and classroom work. Increasingly, nursing schools are working with other institutions to offer students classes in which they learn with or from students and professionals in other disciplines. For example, the University of Michigan Center for Interprofessional Education offers courses in such topics as health care delivery in low- and middle-income countries, social justice, trauma-informed practice, interprofessional communication, and teamwork. Courses are open to students from the schools of social work, pharmacy, medicine, nursing, dentistry, physical therapy, public health, and business.4

Despite the benefits of interprofessional education, however, there are barriers that affect the implementation of such programs in health professions education, including different schedules, lack of meeting space, incongruent curricula plans, faculty not trained to teach interprofessionally, faculty overload, and the challenge of providing adequate opportunities for all levels of students (NLN, 2015a). The use of simulation has been proposed as a vehicle for overcoming such barriers to impart interprofessional collaborative competencies (NLN, 2013); a systematic review of the evidence found that this approach can be effective (Marion-Martins and Pinho, 2020). Nurses can also gain interprofessional experience by pursuing dual degrees. For example, the University of Pennsylvania offers dual degrees that combine nursing with health care management, bioethics, public health, law, or business administration.

Continually Adapting to New Technologies

Nurses can use a wide variety of existing and emerging technologies and tools to address SDOH and provide high-quality care to all patients (see Box 7-5). Broadly speaking, these technologies and tools fall into three categories: patient-facing, clinician-facing, and data analytics. Patient- and clinician-facing tools collect data and help providers and patients connect and make decisions

___________________

4 Not all courses are open to students from all schools.

about care. Data analytics uses data, collected from patients or other sources, to analyze trends, identify disparities, and guide policy decisions. Beginning as students, all nurses need to be familiar with these technologies, be able to engage with patients or other professionals around their appropriate use, and understand how their use has the potential to exacerbate inequalities.

Patient-facing technologies include apps and software, such as mobile and wearable health devices, as well as telehealth and virtual visit technologies (FDA, 2020). These tools allow nurses and other health care providers to expand their reach to those who might otherwise not have access because of geography, transportation, social support, or other challenges. For example, telehealth and mobile apps allow providers to see people in their homes, mitigating such barriers to care as transportation while also helping providers understand people in the context of their everyday lives. Essential skills for nurses using these new tools will include

the ability to project a caring relationship through technology (Massachusetts Department of Higher Nursing Education Initiative, 2016) and to use technology to personalize care based on patient preferences, technology access, and individual needs (NLN, 2015b). The role of telehealth and the importance of training nurses in this technology have been recognized for several years (NONPF, 2018; Rutledge et al., 2017), but the urgent need for telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic has made it “imperative” to include telehealth training in nursing curricula (Love and Carrington, 2020). Moreover, it is anticipated that the shift to telehealth for some types of care will become a permanent feature of the health care system in the future (Bestsennyy et al., 2020).

Clinician-facing technologies include EHRs, clinical decision support tools, mobile apps, and screening and referral tools (Bresnick, 2017; CDC, 2018; Heath, 2019). A number of available digital technologies can facilitate the collection and integration of data on social needs and SDOH and help clinicians hold compassionate and empathetic conversations about those needs (AHA, 2019; Giovenco and Spillane, 2019). In 2019, for example, Kaiser Permanente launched its Thrive Local network (Kaiser Permanente, 2019), which can be used to screen for social needs and connect people with community resources that can meet these needs. The system is integrated with the EHR, and it is capable of tracking referrals and outcomes to measure whether needs are being met; these data can then be used to continuously improve the network.

Nurses will need to understand how and when to use these types of tools, and can leverage their unique understanding of patient and community needs to improve and expand them. As described in Chapter 10, such technologies as EHRs and clinical alarms can burden nurses and contribute to workplace stress. However, nurses have largely been left out of conversations about how to design and use these systems. For example, although nurses are one of the primary users of EHR systems, little research has been conducted to understand their experiences with and perceptions of these systems, which may be different from those of other health care professionals (Cho et al., 2016; Higgins et al., 2017). Out of 346 usability studies on health care technologies conducted between 2003 and 2009, only 2 examined use by nurses (Yen and Bakken, 2012). Educating nurses to understand and assess the benefits and drawbacks of health care technologies and have the capacity to help shape and revamp them can ultimately improve patient care and the well-being of health professionals.

Tools for data analytics are increasingly important for improving patient care and the health of populations (Ibrahim et al., 2020; NEJM Catalyst, 2018). Analysis of large amounts of data from such sources as EHRs, wearable monitors, and surveys can help in detecting and tracking disease trends, identifying disparities, and finding patterns of correlation (Breen et al., 2019; NASEM, 2016a; Shiffrin, 2016). The North Carolina Institute for Public Health, for example, collaborated with a local health system in analyzing data to inform a community health improvement plan (Wallace et al., 2019). Data on 12 SDOH indicators were sourced

from the American Community Survey and mapped by census tract. The mapping provided a visualization of the disparities in the community and allowed the health system to focus its efforts strategically to improve community health. The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services later replicated this strategy across the entire state (NCDHHS, 2020).

There are opportunities for nurses to specialize in this type of work. For example, nursing informatics is a specialized area of practice in which nurses with expertise in such disciplines as information science, management, and analytical sciences use their skills to assess patient care and organizational procedures and identify ways to improve the quality and efficiency of care. In the context of SDOH, nursing informaticists will be needed to leverage artificial intelligence and advanced visualization methods to summarize and contextualize SDOH data in a way that provides actionable insights while also eliminating bias and not overwhelming nurses with extraneous information. Big data are increasingly prevalent in health care, and nurses need the skills and competencies to capitalize on its potential (Topaz and Pruinelli, 2017). Even nurses who do not specialize in informatics will need to understand how the analysis of massive datasets can impact health (Forman et al., 2020; NLN, 2015b). Investments in expanding program offerings, certifications, and student enrollment will be needed to meet the demand for nurses with such skills.

As noted, however, despite its promise for improving patient care and community health, technology can also exacerbate existing disparities (Ibrahim et al., 2020). For example, people who lack access to broadband Internet and/or devices are unable to take advantage of such technologies as remote monitoring and telehealth appointments (Wise, 2012). Older adults, people with limited formal education, those living in rural and remote areas, and the poor are less likely to have access to the Internet. As health care becomes more reliant on technology, these groups are likely to fall behind (Arcaya and Figueroa, 2017). In addition, such technologies as artificial intelligence and algorithmic decision-making tools may exacerbate inequities by reflecting existing biases (Ibrahim et al., 2020). Nursing education needs to prepare nurses to understand these potential downsides of technology in order to prevent and mitigate them. This has become a particularly critical issue during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the rapid shift to telehealth potentially having consequences for those with low digital literacy, limited English proficiency, and a lack of access to the Internet (Velasquez and Mehrotra, 2020).

Not all nurses will need to acquire all of the key technological competencies; curricula can be developed according to the likely needs of nurses working at different levels. For example, most nurses will need the knowledge and skills to use telehealth, digital health tools, and data-driven clinical decision-making skills in practice, whereas nurse informaticians and some doctoral-level nurses will need to be versed in device design, bias assessment in algorithms, and big data analysis.

EXPANDING LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES

As stated previously, the domains and competencies enumerated above cannot be conveyed to nursing students through traditional lectures alone. Building the competencies to address population health, SDOH, and health inequities will require substantive experiential learning, collaborative learning, an integrated curriculum, and continuing professional development throughout nurses’ careers (IOM, 2016b). The 2019 Campaign for Action survey of nursing educators and leaders found that a majority of respondents identified “innovative community clinical experiences” and “interprofessional education experiences” as the top methods for teaching population health (Campaign for Action, 2019b). A recurrent theme in interviews with respondents was the importance of active and experiential learning, with opportunities for partnering with nontraditional agencies (Campaign for Action, 2019b). These types of community-based educational opportunities, particularly when they involve partnerships with others, are critical for nursing education for multiple reasons.

First, experience in the community is essential to understanding SDOH and gaining the competencies necessary to advance health equity (IOM, 2016b). In fact, restricting education in SDOH to the classroom may even be harmful, given the finding of a 2016 study that medical students who learned about SDOH in the classroom rather than through experiential learning demonstrated an increase in negative attitudes toward medically underserved populations (Schmidt et al., 2016).

Second, community-based education offers opportunities for students to engage with community partners from other sectors, such as government offices of housing and transportation or community organizations, preparing them for the essential work of participating in and leading partnerships to address SDOH. An example is a pilot interdisciplinary partnership between a school of nursing and a city fire department in the Pacific Northwest that allows students to practice such skills as motivational interviewing to identify the range of problems (e.g., transportation issues, difficulty accessing insurance or providers, lack of caregiving support) faced by people calling emergency services (Yoder and Pesch, 2020).

Third, nursing is increasingly practiced in community settings, such as schools and workplaces, as well as through home health care (WHO, 2015). Nursing students are prepared to practice in hospitals, but do not necessarily receive the same training and preparation for these other environments (Bjørk et al., 2014). Education in the community allows nursing students to learn about the broad range of care environments and to work collaboratively with other professionals who work in these environments. For example, students may work in a team with community health workers, social workers, and those from other sectors (e.g., housing and transportation), work that both enriches the experience of student nurses and creates bridges between nursing and other fields (Zandee et

al., 2010). Nurses who have these experiences during school may then be more prepared to lead and participate in multisector efforts to address SDOH—the importance of which is emphasized throughout this report—once they enter practice. Evidence suggests that graduating students are more likely to seek work in areas that are familiar to them from their education, clinical experience, and theoretical training (Jamshidi et al., 2016); thus, these nontraditional educational experiences may increase the number of nurses interested in working in the community. Moreover, while training in acute care settings has often been regarded as more valuable than that provided in community settings, evidence indicates that the two offer comparable opportunities for learning clinical skills (Morton et al., 2019). In fact, clinical care in community-based settings can present greater complexity relative to that in the hospital, and some technical skills (e.g., epidemiologic disease tracking, tuberculosis assessment and management, immunizations) are more available in community than in acute care settings (Morton et al., 2019).

Some nursing programs have incorporated community-based experiential learning into their programs. At community colleges and universities, schools have implemented nurse-managed clinics that serve the local population and their own students while also giving students technical skills and experience in interacting with the community. Lewis and Clark Community College, for example, operates a mobile health unit that brings health and dental care to six counties in southern Illinois (Lewis and Clark, n.d.), while nursing students at Alleghany College of Maryland can gain experience in the Nurse Managed Wellness Clinic, which offers such services as immunizations, screenings, and physicals (Alleghany College, 2020). At the baccalaureate and master’s level, a number of schools offer longitudinal, integrated experiences in settings as varied as federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), public health departments, homeless shelters, public housing sites, public libraries, and residential addiction programs (AACN, 2020c). Students and faculty at the University of Washington School of Nursing, for example, support community-oriented projects in partnership with three underserved communities in the Seattle area. Graduate students work for 1 year on grassroots projects (e.g., food banks, school health) and then reinforce this experience with 1 year of work at the policy level (AACN, 2020c). At the doctoral level, Washburn University transformed its DNP curriculum to incorporate SDOH and reinforce that instruction through experiential learning in the community (see Box 7-6). In addition to clinical education, nursing students can participate in nontraditional clinical community engagement and service learning opportunities, such as volunteering at a homeless shelter or working in a service internship for a community organization. These opportunities get students into the community, help them build relationships with people from health care and other sectors, and promote understanding of and engagement with SDOH (Bandy, 2011).

Simulation-Based Education

Simulation-based education is another useful tool for teaching nursing concepts and developing competencies and skills (Kononowicz et al., 2019; Poore et al., 2014; Shin et al., 2015). It can range from very low-tech (e.g., using oranges to practice injections) to very high-tech (e.g., a virtual reality emergency room “game”), but all simulations share the ability to bridge the gap between education and practice by imparting skills in a low-risk environment (SSIH, n.d.).

Simulations give students an opportunity to make real-time decisions and interact with virtual patients without having to face many of the challenges of traditional clinical education (Hayden et al., 2014). They can be used to enhance many types of skills, including communication (NASEM, 2018b), cultural sensi-

tivity (Lau et al., 2016), and screening for SDOH (Thornton and Persaud, 2018). Several simulation-based tools are available for learning about the realities of poverty, such as the Community Action Poverty Simulation (see Box 7-7) and the Cost of Poverty Experience (ThinkTank, n.d.). Such tools can help nurses identify ways in which their practice could directly mitigate the effects of poverty on individuals, families, and communities. Evaluations of poverty simulations have found that they can positively impact attitudes toward poverty and empathy among nurses and nursing students (Phillips et al., 2020; Turk and Colbert, 2018), although one study noted that the simulations should be accompanied by the inclusion of social justice concepts throughout the curriculum to achieve lasting change (Menzel et al., 2014).

Individual schools may or may not have the resources or faculty to support some types of simulation activities. For those that do not, simulation centers shared by schools of multiple professions and hospitals can provide access (Marken et al., 2010). For example, the New York Simulation (NYSIM) Center was created through a public–private partnership to manage interprofessional, simulation-based education for students and hospital employees across multiple sites (NYSIM, 2017). The opportunity to take part in simulation experiences with students from other health professions can also improve collaboration and teamwork and prepare nurses for practicing interprofessionally in the workplace (von Wendt and Niemi-Murola, 2018).

Limitations on in-person clinical training during the COVID-19 pandemic conditions have demonstrated the promise of simulation-based education as

a way to supplement traditional nursing education, allowing students to complete their education and sustaining the nursing workforce pipeline (Horn, 2020; Jiménez-Rodríguez et al., 2020; Yale, 2020). Before the pandemic, the NCSBN conducted a longitudinal, randomized controlled trial of the use of simulation and concluded that substituting simulation-based education for up to half of a nursing student’s clinical hours produces comparable educational outcomes and students who are ready to practice (Hayden et al., 2014). The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated and accelerated the use of simulation to replace direct care experience in nursing schools, and state boards of nursing have loosened previous restrictions on its use (NCSBN, 2020b). Evaluation of this expanded use of simulation and other virtual experiences during the pandemic is needed, both in preparation for future emergencies and for use in nursing education generally.

RECRUITING AND SUPPORTING DIVERSE PROSPECTIVE NURSES

The composition of the population of prospective nurses and the ways they are supported throughout their education are important factors in how prepared the future nursing workforce will be to address SDOH and health equity. As discussed in prior chapters, developing a more diverse nursing workforce will be key to achieving the goals of reducing health disparities, providing culturally relevant care for all populations, and fostering health equity (Center for Health Affairs, 2018; IOM, 2011, 2016; Williams et al., 2014). A diverse workforce is one that reflects the variations in the nation’s population in such characteristics as socioeconomic status, religion, sexual orientation, gender, race, ethnicity, and geographic origin.

The nursing workforce has historically been overwhelmingly White and female, although it is steadily becoming more diverse (see Chapter 3). The 2016 IOM report assessing progress on the 2011 The Future of Nursing report notes that shifting the demographics of the overall workforce is inevitably a slow process since only a small percentage of the workforce leaves and enters each year (IOM, 2016a). The pipeline of students entering the field, on the other hand, can respond much more rapidly to efforts to increase diversity (IOM, 2016a). Since the 2011 report was published, significant gains have been realized in the diversity of nursing students. The number of graduates from historically underrepresented ethnic and racial groups more than doubled for BSN programs, more than tripled for entry-level master’s programs, and more than doubled for PhD programs (AACN, 2020a). The number of underrepresented students graduating from DNP programs grew by more than 1,000 percent, although this gain was due in large part to rapid growth in these programs generally. Yet, despite these gains, nursing students remain largely female and White: in 2019, 85–90 percent of students were female, and around 60 percent were White. The percentages of ADN, BSN, entry-level master’s, PhD, and DNP graduates in 2019 by race/ethnicity and gender are shown in Tables 7-3 and 7-4, respectively. For example, the

proportion of Hispanic or Latino nurses is highest among ADN graduates (12.8 percent) and lowest among PhD (5.5 percent) and DNP (6 percent) graduates, while the proportion of Asian nurses is highest among MSN graduates (11.2 percent) and lower among graduates with all other degrees. The proportion of PhD graduates who are male (9.9 percent) is significantly lower than the proportion of graduates with other degrees who are male.

Diversifying and strengthening the nursing student body—and eventually, the nursing workforce—requires cultivating an inclusive environment, recruiting and admitting a diverse group of students, and providing students with support and addressing barriers to their success throughout their academic career and into practice. In addition, it is essential to make available information that will enable prospective students to make informed decisions about their education and give them multiple pathways for completing their education (e.g., distance learning, accelerated programs). Accrediting bodies can play a role in advancing diversity and inclusion in nursing schools by requiring certain policies, practices, or systems. For example, the accreditation standards for medical schools of the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) include the following expectation (LCME, 2018):

TABLE 7-3 Nursing Program Graduates by Degree Typea and by Race/Ethnicity, 2019

| Race/Ethnicity | ADNb | BSN | MSNc | PhD | DNP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of degrees | 75,470 | 77,363 | 3,254 | 801 | 7,944 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 1.2% | 0.3% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.5% |

| Asian | 4.6% | 7.9% | 11.2% | 6.6% | 6.9% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 12.8% | 10.2% | 11.3% | 5.5% | 6.0% |

| Black or African American | 12.1% | 8.7% | 8.7% | 12.1% | 15.0% |

| White | 63.2% | 63.6% | 59.4% | 59.2% | 63.7% |

| Two or more races | 2.5% | 2.8% | 2.5% | 1.4% | 2.4% |

| Non-U.S. residents (International) | 0.6% | 1.0% | 0.5% | 9.1% | 0.6% |

| Unknown | n/a | 5.0% | 5.5% | 4.2% | 4.6% |

NOTE: ADN = associate degree in nursing; BSN = bachelor of science in nursing; DNP = doctor of nursing practice; LPN/LVN = licensed practical/vocational nurse; MSN = master of science in nursing.

a Data not available for LPN/LVN.

b ADN data are from 2018.

c Entry-level master’s degree.

SOURCE: American Association of Colleges of Nursing, Enrollment & Graduations in Baccalaureate and Graduate Programs in Nursing (series); Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), Completions Survey (series) for ADN data.

TABLE 7-4 Nursing Program Graduates by Degree Typea and Gender, 2019

| Gender | ADNb | BSN | MSNc | PhD | DNP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of degrees | 77,993 | 77,363 | 3,254 | 801 | 7,944 |

| Male | 14.4% | 13.6% | 15.2% | 9.9% | 13.1% |

| Female | 85.6% | 85.1% | 84.7% | 89.9% | 86.6% |

| Unknown | n/a | 1.4% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.3% |

NOTE: ADN = associate degree in nursing; BSN = bachelor of science in nursing; DNP = doctor of nursing practice; LPN/LVN = licensed practical/vocational nurse; MSN = master of science in nursing.

a Data not available for LPN/LVN.

b ADN data are from 2018.

c Entry-level master’s degree.

SOURCE: American Association of Colleges of Nursing, Enrollment & Graduations in Baccalaureate and Graduate Programs in Nursing (series); Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), Completions Survey (series) for ADN data.

A medical school has effective policies and practices in place, and engages in ongoing, systematic, and focused recruitment and retention activities, to achieve mission appropriate diversity outcomes among its students, faculty, senior administrative staff, and other relevant members of its academic community. These activities include the use of programs and/or partnerships aimed at achieving diversity among qualified applicants for medical school admission and the evaluation of program and partnership outcomes.

Currently, none of the major nursing accreditors (ACEN, CCNE, CNEA) includes similar language in its accreditation standards. As shown in Table 7-5, of six possible areas for standards on diversity and inclusion, ACEN and CCEN have standards only for student training, while CNEA has standards for student training and faculty diversity. No nursing accreditors have standards for student diversity; in comparison, accrediting bodies for pharmacy, physician assistant, medical, and dental schools all have such standards.

Cultivating an Inclusive Environment

Efforts to recruit and educate prospective nurses to serve a diverse population and advance health equity will be fruitless unless accompanied by efforts to acknowledge and dismantle racism within nursing education and nursing practice (Burnett et al., 2020; Schroeder and DiAngelo, 2010; Villaruel and Broome, 2020; Waite and Nardi, 2019). The structural, individual, and ideological racism that exists in nursing is rarely called out, and this silence further entrenches the idea of Whiteness as the norm within nursing while marginalizing and silencing other groups and their perspectives (Burnett et al., 2020; Iheduru-Anderson, 2020; Schroeder and DiAngelo, 2010). Non-White students report a wide variety of negative experiences in nursing school, including unsupportive faculty, discrim-

TABLE 7-5 Diversity and Inclusion in Accreditation Standards

| Accrediting Body | Student Diversity | Faculty Diversity | Academic Leadership Diversity | Pipeline Programs | Student Training | Faculty Training |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing (ACEN) | — | — | — | — | Yes | — |

| Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) | Yes | — | — | — | Yes | — |

| Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant, Inc. (ARC-PA) | Yes | Yes | — | — | Yes | — |

| Commission for Nursing Education Accreditation (CNEA) | — | Yes | — | — | Yes | — |

| Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE) | — | — | — | — | Yes | — |

| Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) | Yes | Yes | — | — | Yes | — |

| Commission on Osteopathic College Accreditation (COCA) | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes |

| Committee on Accreditation of Canadian Medical Schools (CACMS) | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | — |

| Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — |

SOURCE: Batra and Orban, 2020.

ination and microaggressions5 on the part of faculty and peers, bias in grading, loneliness and social isolation, feeling unwelcome and excluded, being viewed as a homogeneous population despite being from varying racial/ethnic groups, lack of support for career choices, and a lack of mentors (Ackerman-Barger et al., 2020; Graham et al., 2016; Johansson et al., 2011; Loftin et al., 2012; Metzger et al., 2020). These experiences are associated with adverse outcomes that include disengagement from education, loss of “self,” negative perceptions of inclusivity and diversity at the institution, and institutions’ inability to recruit and retain a diversity of students (Metzger et al., 2020). By contrast, when students characterize the learning environment as inclusive, they are more satisfied and confident in their learning and rate themselves higher on clinical self-efficacy and clinical belongingness (Metzger and Taggart, 2020).

Notably, however, underrepresented and majority students describe inclusive environments differently. In a study of fourth-year baccalaureate nursing students, both groups described an inclusive classroom as one where they felt comfortable and respected and had a sense of belonging, but underrepresented minority students also noted the importance of feeling safe, feeling free from hostility, and being seen as themselves and not a representative of their group (Metzger and Taggart, 2020). Both groups agreed that inclusivity requires a top-down approach, and that faculty are particularly influential in creating an inclusive environment, yet underrepresented students shared many experiences in which faculty either disrupted the sense of belonging or did not intervene when someone else did (Metzger and Taggart, 2020).

While increased attention has recently been focused on increasing diversity in nursing education, the pervasiveness of racism requires more open acknowledgment and discussion and a systematic and intentional approach that may, as discussed earlier, be uncomfortable for some (Ackerman-Barger et al., 2020; Villaruel and Broome, 2020). Cultivating an inclusive environment requires acknowledging and challenging racism in all aspects of the educational experience, including curricula, institutional policies and structures, pedagogical strategies, and the formal and informal distribution of resources and power (Iheduru-Anderson, 2020; Koschmann et al., 2020; Metzger and Taggart, 2020; Schroeder and DiAngelo, 2010; Villaruel and Broome, 2020; Waite and Nardi, 2019). Nursing school curricula have historically focused on the contributions of White and female nurses (Waite and Nardi, 2019). The weight given to this curricular content sends a message to students—both White students and students of color—about what faculty consider important (Villaruel and Broome, 2020). Moving forward, curricula need to include a critical examination of the history of racism within nursing and an acknowledgment and celebration of the contribution of nurses of color (Waite and Nardi, 2019). Such efforts need to be led by a broad group of individuals from all levels within an institution; racism in institutional practices

___________________