10

Supporting the Health and Professional Well-Being of Nurses

I believe that everything affecting our society affects nurses and that eventually will hemorrhage over to the nursing profession.

—Denetra Hampton, RN, documentary filmmaker of Racism: The African American Nursing Experience Short Film

Nurses are committed to meeting the diverse and often complex needs of people with competence and compassion. While nursing is viewed as a “calling” by many nurses, it is a demanding profession. During the course of their work, nurses encounter physical, mental, emotional, and ethical challenges. Depending on the role and setting of the nurse’s work, these may include incurring

the risk of infection and physical or verbal assault, meeting physical demands, managing and supporting the needs of multiple patients with complex needs, having emotional conversations with patients and families, and confronting challenging social and ethical issues. Nurses, particularly those who work in communities and public health settings, may also face the stress of encountering health inequities laid bare, such as hazardous housing and food insecurity. Nurses’ health and well-being are affected by these stresses and demands of their work, and in turn, their well-being affects their work, including increasing the risk of medical errors and compromising patient safety and care (Melnyk et al., 2018). As shown in the framework introduced in Chapter 1 (see Figure 1-1), well-being is one of five key areas with the potential to enhance nurses’ ability to address social determinants of health (SDOH) and advance health and health care equity.

With the emergence of COVID-19, the day-to-day demands of nursing have been illuminated and exacerbated. Nurses are coping with unrealistic workloads; insufficient resources and protective equipment; risk of infection; stigma directed at health care workers; and the mental, emotional, and moral burdens of caring for patients with a new and unpredictable disease (Shechter et al., 2020; Squires et al., 2020). Nurses are accustomed to setting aside their own needs and fears to care for people and take on the burdens and stresses of families and communities (Epstein and Delgado, 2010). However, if nurses are not supported in maintaining their physical, emotional, and mental well-being and integrity, their ability to serve and support patients, families, and communities will be compromised (e.g., McClelland et al., 2018).

In this chapter, the committee briefly describes the impact of nurse wellbeing, then presents a framework for well-being in the context of the health care professions. The chapter examines aspects of nurses’ physical, mental, social, and moral1 well-being and health, and concludes with a review of approaches for addressing nurses’ health and well-being in various areas.

THE FAR-REACHING IMPACT OF NURSE WELL-BEING

Nurse well-being—or the lack thereof—has impacts on nurses, patients, health care organizations, and society (NASEM, 2019a). Well-being affects individual nurses in terms of physical and mental health, joy and meaning in their work, professional satisfaction, and engagement with their job. Nurses’ well-being affects patients and their perceptions of the quality of care they receive

___________________

1 Moral well-being is defined by Thompson (2018) as “the highest attainable development of innate capacities that enable humans to flourish as embodied, individuated but necessarily interdependent social organisms by managing the adaptive challenges of vulnerability, constraint, connection, and cooperation in an uncertain, risky environment.”

(e.g., McClelland et al., 2018; Melnyk et al., 2018; Ross et al., 2017; Salyers et al., 2017), and it also affects the health care system, impacting turnover rates and the costs of hiring and training new nurses (Jones and Gates, 2007; Lewin Group, 2009; Li and Jones, 2013). With more than 1 million nurses projected to retire between 2020 and 2030 (Buerhaus et al., 2017), retaining established nurses and supporting new nurses is vital to the growth and sustainability of the workforce. The costs associated with nurse turnover are high. According to the most recent annual National Health Care Retention and RN Staffing Report, the average cost of turnover for a hospital-based registered nurse (RN) is $44,400. Consequently, nurse turnover costs the average hospital $3.6–$6.1 million per year (NSI Nursing Solutions, 2020). Ensuring nurse well-being is not just good for nurses, then; it is essential for the health and safety of patients, the functioning of health systems, and the financial health of health care organizations.

A FRAMEWORK FOR WELL-BEING

Well-being is an inherently complex concept, encompassing an individual’s appraisal of physical, social, and psychological resources needed to meet a psychological, physical, or social challenge (Dodge at al., 2012). The 2019 National Academies report Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout (NASEM, 2019a) adopts an existing definition of well-being:

an integrative concept that characterizes quality of life with respect to an individual’s health and work-related environmental, organizational, and psychosocial factors. Well-being is the experience of positive perceptions and the presence of constructive conditions at work and beyond that enables workers to thrive and achieve their full potential. (Chari et al., 2018, p. 590)

Professional well-being is associated with individuals’ job satisfaction, including being able to find meaning and fulfillment in work, feeling engaged, and having a high-quality work experience (Danna and Griffin, 1999; Doble and Santha, 2008; NASEM, 2019a). Well-being is often classified into objective well-being, or the satisfaction of physical needs, such as food, clothing, and shelter, and subjective well-being, or the emotional and psychological support needed to flourish (NASEM, 2019b; Prilleltensky, 2012). For the purposes of this report, the committee has chosen to examine well-being using a broad lens, encompassing many aspects of a nurse’s physical, mental, social, and moral well-being.

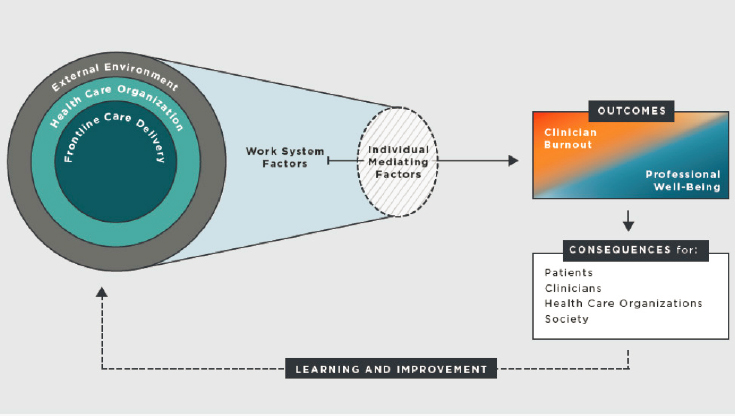

Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout (NASEM, 2019a) uses a visual framework to describe clinician burnout and professional well-being (see Figure 10-1). While focused primarily on addressing burnout, this framework demonstrates how the physical, social, and legal environments at different

SOURCE: NASEM, 2019a.

levels work together to impact clinician well-being. The first level, “external environment,” represents the health care industry, laws, regulations, standards, and societal values. The second level, “health care organization,” encompasses the leadership and management, governance, and policies and structures of the organization. The third level, “frontline care delivery,” represents the actions of and interactions among team members, local organizational conditions, technologies in the workplace, the physical environment, and work activities. Together, these three levels shape and constrain the day-to-day work environment of clinicians, called “work system factors.” These work system factors include both job demands, such as workload and administrative burden, and job resources, such as organizational culture, teamwork, and professional relationships. These factors are mediated by individual factors, such as personality, coping strategies, resilience, and social support, and ultimately impact the health and well-being of clinicians.

While this framework was designed with the clinical environment in mind, it can be applied to nurses working in other environments, including communities, schools, and non–health care organizations. The specific work factors will vary from setting to setting—for example, some nurses will contend with electronic health records (see Box 10-1), while others will not—but the general schema holds true for most nurses in most settings.

THE STATE OF NURSES’ HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

This section provides a brief overview of nurses’ health and well-being in the following areas: physical, occupational, mental and behavioral, moral, and social. It should be noted that both within and across these categories, some issues are interrelated and may exacerbate or reinforce others. For example, it has been demonstrated that chronic stress can create biological conditions that lead to obesity (Yau and Potenza, 2013). In addition, obesity has been associated with high-demand, low-control work environments and with working long hours (Schulte et al., 2007). These conditions—stress, high-demand and low-control work environments, and long hours—are common in nursing work environments, which may place nurses at risk of obesity. Obesity, in turn, has been associated with higher risk of occupational injury (Jordan et al., 2015; Nowrouzi et al., 2016; Schulte et al., 2007), for which nurses are already at high risk. It should be noted as well that most of the evidence cited in this chapter relates to nurses in clinical settings. While there is some limited research on other settings, including home visiting (Mathiews and Salmond, 2013), rural communities (Terry et al.,

2015), prisons (Walsh and Freshwater, 2009), and schools (Jameson and Bowen, 2018), the vast majority of research on nurses’ well-being focuses on their work in clinical care, pointing to a need for more research on nurse well-being in all settings, including public and community health.

Physical Health

The physical health of American nurses is often worse than that of the general population, especially with regard to nutrition, sleep, and physical activity (Gould et al., 2019). Box 10-2 shows a snapshot of the physical health of nurses.

Occupational Safety and Health

There is a high prevalence of occupational injuries to health care workers, especially among nurses (OSHA, n.d.). Nurses may be exposed to a number of hazards in the workplace, including infectious agents; needle sticks; slips and falls; and injuries due to standing, bending, and lifting patients (Dressner and Kissinger, 2018). While nursing involves inherent risks due to proximity to infectious agents and other hazards and the physical demands of the work, these risks may be exacerbated by workplaces that are understaffed and underresourced. Nurse staffing levels have been associated with occupational injuries (Hughes, 2008), including musculoskeletal injuries and disorders. In addition, as described in Chapter 8, the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the extent to which nurses’ jobs put them at risk of physical harm due to lack of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and severe staffing shortages. Nurses of color may be particularly at risk of COVID-19-related harms. As of September 2020, nurses of color made up half of the estimated 213 total RN deaths from COVID-19; nurses of Filipino descent accounted for 31.5 percent of those total deaths (Akhtar, 2020). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reviewed data from March to May 2020 in 13 states (n = 438) and found that greater than 50 percent of the health care workers hospitalized because of COVID-19 were Black; 36.3 percent of the hospitalized health care workers were working in nurse functions that included nurse and certified nursing assistant (CNA) (Kambhampati et al., 2020).

Patient safety is a frequent topic in discussion of improving care and is also a measure of nurses’ quality of care (AHRQ, 2019; Vaismoradi et al., 2020). Patient safety, staff safety, and equity have become a highlighted area of need, declining as health care workers face the challenge of the short- and long-term effects of structural racism, inequities, and bias. These challenges include caring for patients who are often the most underrepresented in the community, who lack adequate access to health care, and who tend to work in low-wage jobs and to have increased exposure to illness among the general public. Chin (2020) discusses the necessity of aligning health care organizations’ approaches and intentionality toward patient safety and equity. One of the ways health care organizations and leadership can be more intentional is by stratifying data with patient and clinician

input, and nurses are a critical component of this process. As mentioned in Chapter 8, leaders and organizations will have to support an actual culture of equity throughout, and will require intentional change.

Mental and Behavioral Health

Mental health is defined as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” (WHO, 2004). Mental health issues, including stress, burnout, and depression, are common among nurses (Adriaenssens et al., 2015; Da Silva et al., 2016; Gómez-Urquiza et al., 2016, 2017; Mark and Smith, 2012; McVicar, 2003). Whereas the exact prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)2 among nurses is unclear (see Schuster and Dwyer, 2020), intensive care unit nurses are particularly exposed to repeated trauma and stress and often experience PTSD, anxiety, depression, and burnout (Mealer et al., 2017).

These mental health issues have effects on multiple levels. They adversely impact individual nurses’ quality of life and enjoyment of work (Tarcan et al., 2017); they increase absenteeism and staff turnover (Burlison et al., 2016; Davey et al., 2009; Lavoie-Tremblay et al., 2008; Oyama et al., 2015); and they impact nurses’ ability to provide quality and safe care, resulting in such consequences as general and medication administration errors, poor relationships with patients and coworkers, and lower patient satisfaction (Gärtner et al., 2010). In addition, nurses with mental health concerns may be stigmatized and discriminated against by RN licensing boards. A recent study by Halter and colleagues (2019) found that of 30 boards that asked questions about mental illness, 22 asked questions not compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Studies have found that caring for patients on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic can increase stress, depression, anxiety, and PTSD for nurses (Kang et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020). Early research results suggest that the pandemic has placed nurses at high risk of mental health sequelae, particularly anxiety, depression, and peritraumatic dissociation (Azoulay et al., 2020). Box 10-3 describes how addressing the COVID-19 crisis has impacted nurses’ health and well-being.

Burnout

Burnout is an increasingly prevalent problem among clinicians, including nurses, and it has significant consequences for patients, organizations, teams,

___________________

2 The American Psychiatric Association defines PTSD as “a psychiatric disorder that may occur in people who have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event such as a natural disaster, a serious accident, a terrorist act, war/combat, or rape or who have been threatened with death, sexual violence or serious injury” (see https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd [accessed April 13, 2021]).

and nurses themselves. Burnout syndrome is characterized by three components: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (e.g., cynicism, apathy), and a low sense of personal accomplishment at work (Maslach and Jackson, 1981). Estimated rates of burnout among U.S. nurses have ranged between 35 and 45 percent (Aiken et al., 2002; Moss et al., 2016), although many studies focus only on the emotional exhaustion component of burnout, painting an incomplete picture (NASEM, 2019a). The consequences of burnout can include poor patient outcomes, high turnover rates, increased costs, and clinician illness and suicide (NASEM, 2019a). Factors including high workloads, staff shortages, extended shifts (Stimpfel et al., 2012), and the burden of documentation (see Box 10-1) can all contribute to nurse burnout. Another known contributor to burnout is a

mismatch between the skills and preparation of workers and the jobs that they are expected to perform (Maslach, 2017).

Nurses in all roles and settings can experience burnout. Nursing students may experience academic and emotional burnout before they even enter the workforce (Ríos-Risquez et al., 2018). A shift toward preventive care and care management based in primary care or patient-centered medical homes means there is a growing demand on nurses to take on more complex patients and associated tasks, increasing burnout among nurses in primary care (Duhoux et al., 2017). Nurses in other settings that entail prolonged contact with patients such as critical care, oncology, and psychiatric nursing experience burnout as well (Cañadas-De la Fuente et al., 2017; Jackson et al., 2018). While data are lacking on burnout among nurse practitioners, some evidence shows they can experience burnout comparable to that experienced by nurses and physicians (Hoff et al., 2019). Nurses who work in long-term care settings face particular occupational stressors, such as physical or verbal abuse from residents with dementia, frequent physical transfers of residents, exposure to death and declining health among residents, and caring for individuals with very different care needs (Woodward et al., 2016).

Compassion Fatigue

Compassion fatigue, considered distinct from burnout, is defined as “a health care practitioner’s diminished capacity to care as a consequence of repeated exposure to the suffering of patients, and from the knowledge of their patients’ traumatic experiences” (Cavanagh et al., 2020, p. 640). Compassion fatigue occurs when a nurse’s ability to empathize with people is reduced as a result of repeated exposure to others’ suffering (Peters, 2018). Research suggests a number of factors that can lead to compassion fatigue, some of which are organizational and some of which are individual. Organizational factors include chronic and intense patient contact, prolonged stress, a lack of support, high workload, hours per shift, and time constraints that hinder quality care (Peters, 2018). Individual factors include a personal history of trauma, a lack of awareness about compassion fatigue, an inability to maintain professional boundaries (e.g., taking on extra shifts), and a lack of self-care (Peters, 2018).

Suicide

Nurses, like physicians, are at higher risk than the general population for suicide (Davidson et al., 2020a; NASEM, 2019a). Longitudinal data from 2005 through 2016 showed that nurses committed suicide at a higher rate relative to the general population. Both female and male nurses were at greater risk of suicide (female incident rate ratio [IRR] = 1.395, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.323–1.470, p <.001; male IRR = 1.205, 95% CI 1.083, 1.338, p <.001) (Davidson et

al., 2020a). Despite this increased risk, relatively little attention has been paid to understanding and preventing nurse suicide (Davidson et al., 2018a).

Behavioral Health

Estimates indicate that nurses have the same rate of substance use disorders (SUDs) as the general population (Strobbe and Crowley, 2017; Worley, 2017), with approximately 10 percent of the nursing population having an SUD (Worley, 2017). In addition to the general risk factors that are associated with SUD, including genetic predisposition, history of trauma or abuse, early age at first use of a substance, and comorbid mental health disorders, nurses may also have unique risk factors that include access to controlled substances, workplace stress, and lack of education about SUDs (Worley, 2017). Nursing students are also at risk of SUDs (ANA, 2015; Strobbe and Crowley, 2017).

Moral Well-Being

Nurses in all roles and settings are confronted with ethical challenges that have the potential to cause moral suffering (ANA, 2015), including moral distress or moral injury (Rushton, 2018). When nurses are unable to convert their moral choices into action because of internal or external constraints, moral distress ensues and threatens their integrity (Ulrich and Grady, 2018). Moral distress also arises to varying degrees in response to moral uncertainty, moral conflicts or dilemmas involving competing ethical values or commitments, or tensions resulting from not being able to share moral concerns with others (Morley et al., 2019). Moral distress, the most well-researched form of moral suffering, occurs in response to moral adversity that threatens or violates an individual’s professional values and integrity, and is associated with myriad negative consequences (Burston and Tuckett, 2013; Epstein and Delgado, 2010; Morley et al., 2019; Rushton et al., 2016). Nurses can experience moral distress when they feel inadequately supported, when health care resources are inappropriately used, and when there is disagreement between the patient’s care plan and the patient’s family’s wishes (Burston and Tuckett, 2013; Epstein et al., 2019). For example, nurses may experience moral distress when asked to provide life support care that is not in the best interest of the patient (Kasman, 2004). Moral injury, a more extreme form of moral suffering, occurs when there is “a betrayal of what’s right, by someone who holds legitimate authority … in a high stakes situation” (Shay, 2014, p. 182). It involves a violation of one’s moral code by witnessing, participating in, or precipitating a variety of moral harms. While the roots of the concept began in the military, nurses and other clinicians increasingly are exploring its application in health care.

Nurses can suffer from moral distress when they lack the resources or capacity to help their patients (Kelly and Porr, 2018) or are unable to take the ethically

appropriate action because of constraints or moral adversities (Ulrich et al., 2020). Nurses working in communities or with people with complex health needs and social risks, such as SUDs and psychological and behavioral disorders, and those working in high-intensity settings or palliative care can experience moral distress due to the complex moral and ethical issues they confront (Englander et al., 2018; SAMHSA, 2000; Welker-Hood, 2014; Wolf et al., 2019). Nurses who work in clinical care often lose contact with patients when they leave the clinical setting (Wolf et al., 2016), which makes it difficult to help these patients with their nonclinical needs, such as food, safe housing, and a support network. This can leave nurses feeling that their efforts are futile without societal commitment to systemic reforms.

Addressing issues of health equity can involve confronting sexism, racism, ableism, xenophobia, and trauma, which can be uncomfortable and challenging for all involved (Munnangi et al., 2018). In addition, the historical roots of trauma are often “invisible” (Comas-Díaz et al., 2019; Helms et al., 2012), with individuals of color suffering from race-based stress (Comas-Díaz et al., 2019). Moreover, nurses may not feel empowered to raise their concerns about these inequities because of fear of retaliation or compromised relationships (Ulrich et al., 2019). When the claims or voices of nurses and other clinicians are discounted, their stress is heightened (Hurst, 2008).

In the context of COVID-19 (see Box 10-3), evidence is emerging that nurses have experienced moral distress as they have addressed the stark ethical tensions (Morley et al., 2019; Ulrich et al., 2020) created by the pandemic, facing a gap between “what they can do and what they believe they should do” (Pearce, 2020; Rosa et al., 2020). This situation led the American Nurses Association (ANA) to develop guidance to help nurses understand their ethical obligations during a pandemic, particularly with respect to preserving their integrity and well-being (ANA, 2020a,b). Upholding the ethical mandate of nurses to provide respectful, equitable care for all persons and the responsibility to address issues of social justice can be especially challenging during a pandemic (ANA, 2015; ANA and AAN, 2020). Moral injury has become a focus of inquiry both prior to and during the pandemic (Dean et al., 2020; Kopacz et al., 2019; Maguen and Price, 2020; Rushton et al., 2021), and early data suggest that it is emerging as a factor associated with the difficult ethical trade-offs experienced by clinicians in the context of the pandemic (Hines et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2020) and in response to the deaths of Black individuals at the hands of police (Barbot, 2020). The practice setting and ethical climate of the health care organization are postulated as factors that influence the prevalence of moral distress (Rathert et al., 2016; Sauerland et al., 2014). More research is needed to understand the relevance of moral injury among health care professionals and to study its relationship to various measures of well-being and moral resilience (Rushton, 2018).

Social Health and Well-Being

The nature of nursing work means that nurses are constantly interacting with other people, including individuals, families, communities, physicians and other providers, administrators, staff, and other nurses. While these social interactions are essential to the work of caring for individuals and communities, they can also be a source of stress and adversely impact nurse well-being. This section explores three types of negative social interactions: bullying and incivility, workplace violence, and racism and discrimination.

Bullying and Incivility

Bullying and incivility among nurses is a major problem in nursing practice and can result in mental health issues, burnout, and nurses leaving positions or the profession entirely (Spence Laschinger et al., 2012; Weaver, 2013). There is an expected culture within nursing in which young or new nurses will encounter bullying, gossip and belittling, intimidation, hostility, exclusion, and hazing from other staff nurses, supervisors, and managers (Caristo and Clements, 2019; Echevarria, 2013; Meissner; 1986). A survey of more than 10,000 RNs and nursing students found that half of respondents had experienced bullying in the workplace (ANA, n.d.). While the terms “bullying” and “incivility” are often used interchangeably,3 bullying is distinguished by its repetitive nature and is perpetrated by a person in a position of power (Rutherford et al., 2018). ANA defines bullying as “repeated, unwanted, harmful actions intended to humiliate, offend, and cause distress in the recipient,” and incivility as “one or more rude, discourteous, or disrespectful actions that may or may not have a negative intent behind them” (ANA, n.d.).

Psychological safety, the perception that it is safe to take risks within the team, is one important factor in creating healthy, civil, integrity-preserving workplaces (Edmonson, 1999, 2018; Edmondson and Lei, 2014). Low levels of psychological safety in the culture of some health care organizations can undermine nurses’ ability to contribute fully and to thrive in the workplace (Edmonson, 2002; Moore and McAuliffe, 2010, 2012; Newman et al., 2017; Ünal and Seren, 2016). Nurses—particularly those who work in clinical settings—work in teams where hierarchy, power imbalances, and interpersonal aggression can occur (Nembhard and Edmonson, 2006). Maslach and Leitner (2017) suggest that improving civility among the interprofessional team may be a leverage point for reducing burnout. However, there is limited research on the relationship between workplace hierarchies and bullying behaviors among nurses and between nurses and other health care providers (Wech et al., 2020).

___________________

3 The term “lateral violence” is also used interchangeably with “bullying” and “incivility” (Pfeifer and Vessey, 2017).

Workplace Violence

In the United States, health care workers experience the highest level of assault of all occupations, and among health care workers, nurses and patient care assistants experience the highest rates of violence (Groenewold et al., 2018; OSHA, 2015). Aggression and assault can result in long-term effects on nurses that include posttraumatic stress and lower levels of productivity (Gates et al., 2011). Nurses endure both emotional and physical abuse from patients (Gabrovec, 2017; Gates et al., 2011). An ANA health risk assessment of nurses during 2013–2016 indicated that 25 percent of nurses had experienced violence at the hands of patients or their family members (ANA, 2017). However, incidents of assault are substantially underreported by as much as 50 percent because of a lack of workplace reporting policies, a lack of confidence in the reporting system, and fear of retaliation (OSHA, 2015).

A 2018 survey of more than 8,000 critical care nurses found that 80 percent of respondents had experienced verbal abuse at least once during the past year, nearly half physical abuse and discrimination, and 40 percent reported sexual harassment (Ulrich et al., 2019). Patients and family members were reported as the most frequent source of abuse (73 percent and 64 percent, respectively), followed by physicians (41 percent) and other nurses (34 percent). Fewer than half of nurses reported that their organization had zero tolerance policies for verbal abuse, while 62 percent reported such policies for physical abuse. These data paint a picture of work environments that are hostile to the psychological safety and well-being of nurses (Ulrich et al., 2019).

While much of the research on workplace violence focuses on hospital settings, nurses working in other settings are also at risk of violence and aggression. Home visiting nurses, who often work alone in dynamic environments characterized by potentially high-risk situations, are at risk of verbal and physical assault while in the community or people’s homes (Mathiews and Salmond, 2013). The incidence of workplace violence in home nursing is likely underreported because of factors including the perception that violence is part of the job and the moral conflict nurses face between duty to their patients and duty to report an incident of violence (Mathiews and Salmond, 2013). While many organizations are attempting to respond to these challenges, education and training alone are likely insufficient to address the root factors that contribute to them (Geoffrion et al., 2020).

Racism and Discrimination

As discussed in Chapter 2, racism can significantly impact the physical and mental health of individuals. Health can be affected by structural racism (policies and systems), cultural racism (stereotypes, beliefs, and implicit biases), and discrimination (being treated differently based on race) (Williams et al., 2019). Microaggressions, which are brief and commonplace daily indignities, are also

correlated with poor health (Cruz et al., 2019; Nadal et al., 2016; Ong and Burrow, 2017; Sue et al., 2007). Nurses may encounter racism, discrimination, and microaggressions from a number of sources, including employers, educators, managers, colleagues, and patients. Nurses and other clinicians of color can experience hardship, burnout, and the increased emotional labor and burden of an already emotionally demanding job while dealing with the personal negative consequences of racism from patients (Cottingham et al., 2018; Paul-Emile et al., 2016). Accommodating patients’ preferences regarding the race, gender, or religion of their providers has been common practice in the United States, often in a context of little guidance on how to approach these situations (Paul-Emile, 2012). This practice can have adverse effects on clinicians, especially when they are rejected by patients or subject to abuse because of their race. However, nurses’ experiences of racism are not limited to these types of discrete events but are part of the larger system of structural racism in the United States (Waite and Nardi, 2019).

Black nurses in particular have long reported encountering racism in the workplace (Bennett et al., 2019; Wojciechowski, 2020). Internationally educated nurses (IENs)—those who completed a nursing education program in a country outside that of their employer and who have migrated to the United States (see also Chapter 3)—also contend with racism and discrimination (Ghazal et al., 2020). As described in Chapter 8, in the wake of COVID-19, which was first discovered in China, Asian nurses have reported verbal and physical attacks, and some patients have refused their care (AHA, 2020a). Discrimination against Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) nurses is not a new phenomenon, having existed since at least the mid-19th century. However, Stop AAPI Hate, a national coalition focused on tracking and addressing anti-Asian discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic, reported 3,795 hate incidents between March 2020 and February 2021.4 These experiences may lead to increased anxiety, fear for personal safety, and poor physical health (AHA, 2020a).

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) nurses have also reported discrimination and harassment based on sexual orientation or gender identity and expression (Eliason et al., 2011, 2017). In a recent qualitative study of 277 LGBTQ+5 health care professionals, Eliason and colleagues (2017) found that these health care workers faced both work-related stress and hostility from coworkers and patients. Reported consequences included lack of promotions, tenure denials, and negative comments and gossip (Eliason et al., 2017). Avery-Desmarais and colleagues (2020) examined problematic substance use (PSU) and its relationship with stress among a convenience sample of 394

___________________

4 See https://secureservercdn.net/104.238.69.231/a1w.90d.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/210312-Stop-AAPI-Hate-National-Report-.pdf?fbclid=IwAR3jLV0DTBnIy_NK3322T4fWDjZhJaY9A6w05elGLG83bJZ47SVckBrPwKQ (accessed April 13, 2021).

5 Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other sexual/gender minorities.

lesbian, gay, and bisexual nurses. They found that the incidence of PSU was higher among this group than among either the general population of nurses or the general lesbian, gay, and bisexual population.

Nurses with disabilities6 can experience discrimination in the workplace (Neal-Boylan et al., 2015), in nursing school (Neal-Boylan and Smith, 2016), and by nursing boards, as mentioned previously (Halter et al., 2019), and encounter negative stereotypes about their ability to do their job or provide effective care (Neal-Boylan et al., 2012). Nursing students with learning disabilities can encounter difficulties in nursing programs (Northway et al., 2015), including negative perceptions that conflate the need for accommodations for disabilities with a student’s capability as a nurse and professional (Marks and McCulloh, 2016). Nurses in the workforce may be reluctant to disclose a disability or mental illness (Hernandez et al., 2016; Peterson, 2017; Rauch, 2019) or to request a need for accommodations, which could increase the risk of injury to the health care team and potentially patients (Davidson et al., 2016). There has been a call for both health care organizations and nursing schools to see beyond disability as a disqualifier for nursing practice, and instead value professionals with disabilities who can offer unique and different perspectives (Marks and Ailey, 2014; Marks and McCulloh, 2016). New research on disabilities in the general population can increase awareness and depth of understanding, and more research on the health and experience of nurses themselves will build effective strategies for nurses with disabilities to achieve success (Davidson et al., 2016).

APPROACHES TO IMPROVING WELL-BEING

As shown in Figure 10-1, nurse well-being is impacted by the external environment, organizational structure and policies, and the conditions of day-to-day work. These three factors are mediated by individual factors, including personality, resilience, and social support. Together, these structural and individual factors can either strengthen or diminish nurse well-being. The responsibility for addressing nurse well-being lies with both nurses themselves and the systems, organizations, and structures that support them. Some barriers to well-being can be addressed only at the organizational and external environmental levels. For example, the burden of technology on nurses must be lifted by federal regulators, insurance companies, technology companies, and the like. However, individual nurses also have an important role to play in promoting their own well-being.

___________________

6 The definition of disabilities is based on the 1990 ADA and the 2008 ADA Amendments Act, in which a disability is defined as a physical or mental impairment or limitation that significantly affects a person in major life activities that include but are not limited to “caring for oneself, performing manual tasks, seeing, hearing, eating, sleeping, walking, standing, lifting, bending, speaking, breathing, learning, reading, concentrating, thinking, communicating, and working” (American Disabilities Act, Title 42, Chapter 126, § 12111; https://www.ada.gov/pubs/adastatute08.htm#12102 [accessed April 13, 2021]).

There is emerging evidence that despite the constraints imposed by the system, some nurses are able to remain healthy and whole and grow in response to adversity (Cui et al., 2021; Itzhaki et al., 2015; Okoli et al., 2021; Traudt et al., 2016). Nurses need the skills and tools that enable them to exercise their autonomy, agency, and competence within these systems. Further investigation is needed to understand the individual and system characteristics that create the conditions for nurses to thrive in the midst of complexity, uncertainty, and unpredictability.

This section first examines individual-level approaches to well-being and then turns to a review of approaches at the systems level. The committee notes that although there exists no menu of ready-to-implement, evidence-based interventions for improving nurse well-being (NASEM, 2019a), a great number of efforts currently being pursued can offer inspiration and opportunities for evaluation, replication, and scalability. However, as noted by Melnyk and colleagues (2020) in a recent systematic review of interventions focused on improving physicians’ and nurses’ physical and mental well-being, more randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to examine the efficacy of such interventions as many of the available studies have weaknesses in their methodologies.

Individual-Level Interventions

While health care organizations must create the workplace conditions for well-being and integrity to thrive, nurses are also responsible for identifying their own needs and investing in their well-being (Ross et al., 2017). This responsibility arises from their inherent human dignity and their professional ethical mandate to invest in their own integrity and well-being so they can execute the responsibilities of their nursing role (ANA, 2015). Provision 5 of the ANA Code of Ethics states that nurses should “eat a healthy diet, exercise, get sufficient rest, maintain family and personal relationships, engage in adequate leisure and recreational activities, and attend to spiritual or religious needs” (ANA, 2015, p. 35).

Although nurses are often knowledgeable about the importance of these issues, that knowledge does not always translate into action (Ross et al., 2017). Ross and colleagues (2017) identify a number of intrinsic and extrinsic factors that affect nurses’ participation in health-promoting behaviors. Intrinsic factors include personal characteristics and beliefs, perceived benefits and barriers, self-efficacy, gender and age, fatigue, depression, and anxiety. Extrinsic factors include norms, social support, role modeling, financial and time constraints, and institutional support. Shift work and work schedules, as well as competing demands outside of work, such as caring for adult or child dependents, are additional barriers to participation (Ross et al., 2017).

Below, the committee examines interventions and initiatives directed at improving individual nurses’ health and well-being in a number of areas. Many such initiatives address multiple areas of well-being and use multiple approaches. For example, the Healthy Nurse, Healthy Nation (HNHN) Grand Challenge, an effort

of ANA and its partners, seeks to transform the health of 4 million RNs through a focus on physical activity, nutrition, rest, quality of life, and safety (ANA Enterprise, 2018). Organizations that participate in HNHN have developed a number of individual-focused initiatives, such as offering onsite fitness opportunities, walking programs, increased access to healthy food, mindfulness resources, and dedicated rooms for nurses to reset and relax (ANA Enterprise, 2018, 2019; Jarrín et al., 2017). Other well-being initiatives are focused on a specific behavior or health characteristic, but one that may have consequences for multiple areas of well-being. For example, poor sleep patterns are associated with poor physical and mental health, an increased risk of obesity, and an increased risk of accidents both in and outside of the workplace (IOM, 2006).

The initiatives and ideas described below are designed to improve the health of nurses by addressing a wide variety of targets:

- physical activity, diet, and sleep;

- substance use;

- resilience;

- mental health;

- ethical competence;

- incivility, bullying, and workplace violence; and

- racism, prejudice, and discrimination.

Physical Activity, Diet, and Sleep

A recent systematic review of workplace interventions to address obesity in nurses found limited evidence of successful interventions. The authors recommend that interventions be tailored to the unique aspects of nurses’ working lives (Kelly and Wills, 2018) and that interventions not be universal but targeted toward those who are obese. In their systematic review, Melnyk and colleagues (2020) found that visual triggers, pedometers, and health coaching can increase participation in physical activity. The Nurses Living Fit program was effective in reducing nurses’ body mass index (BMI) over a 12-week intervention period; however, the effects of the program on BMI were not sustained (Speroni et al., 2014).

A recent scoping review of studies looked at interventions targeted at nurses who work shifts and aimed at improving sleep patterns or managing fatigue (Querstret et al., 2020). In these studies, most of which were conducted in Italy, Taiwan, and the United States interventions fell into three primary categories: napping, working different shift patterns, and exposure to light or light attenuation. With regard to napping interventions, the authors found mixed results. For studies that measured performance at work as an outcome, there was improvement on some measures (e.g., information processing improving after a 30-minute nap). Studies that examined shift patterns (e.g., rotating shift patterns,

fixed night versus day shifts, 8-hour versus 12-hour rotating shifts) found that shift patterns including night shifts were associated with poorer sleep quality and increased fatigue. Results of light exposure studies were similarly mixed. Four studies found that self-reported energy levels increased with exposure to bright light. Another study, however, found no effect of an intervention involving light visors on fatigue or sleep. The scoping review found no studies conducted on samples involving nurse midwives. Querstret and colleagues (2020) conclude that the literature is inconsistent regarding how to intervene to improve sleep and reduce fatigue for nurses who work shifts, and that the interventions and measures used in these studies were disparate in nature.

Substance Use

A recent position statement from the Emergency Nurses Association and the International Nurses Society on Addictions called for four primary actions to address nurses with SUDs (Strobbe and Crowley, 2017): providing education to nurses and other employees, adopting alternative-to-discipline (ATD) approaches, considering drug diversion in the context of personal use as a symptom and not a criminal offense, and ensuring that nurses and nursing students are aware of the risks associated with SUDs and have a way to report concerns safely. The two primary approaches to treating nurses with SUDs have been either a disciplinary approach or an ATD program (Monroe et al., 2013; NCSBN, 2011; Russell, 2020). Monroe and colleagues (2013) conclude that ATD programs have a greater impact than disciplinary programs on protecting the health and safety of the public, as they identify and enroll more nurses and in turn remove more nurses with SUDs from direct patient care. These programs have been adopted by many state boards of nursing (Russell, 2020). In an analysis of 27 state board of nursing programs, Russell (2020) found a lack of consistency among them and suggests that more research is needed to identify the essential components of such programs. Common components identified in at least half of the programs included an alcohol/drug abstinence requirement, use of mood-altering medications for psychiatric/medical conditions, an Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous program, and restricted hours or shifts (Russell, 2020).

In a retrospective study of 7,737 nurses participating in SUD programs between 2007 and 2015, Smiley and Reneau (2020) found that bimonthly random drug tests, a minimum of 3 years in a program, and daily check-ins were associated with successful program completion. They also found that structured group meetings were helpful. The best results were for those nurses who stayed in a program at least 5 years and were tested twice per month. The authors recommend that an expert panel review these results and develop formal guidelines for such programs, and that boards of nursing test these guidelines in their ATD programs. In addition, health care organizations and employers have a responsibility

to detect early patterns of drug diversion7 proactively before they become severe. To this end, organizations are using such technologies as automated dispensing cabinets, advanced analytics, and machine learning.8

Resilience

Training focused on building individual resilience is often offered to prepare nurses for the fatigue, stress, workload, and burnout they may face (Taylor, 2019). Resilience refers to “the capacity of dynamic systems to withstand or recover from significant disturbances” (Masten, 2007, p. 923). Humans are thought to have an innate resilience potential that evolves over time and fluctuates depending on the context; the interplay of individual factors; social, community, environmental, and societal conditions; and moral/ethical values and commitments (Rushton, 2018; Szanton et al., 2010). Resilience includes “the ability to face adverse situations, remain focused, and continue to be optimistic for the future,” and it is described as a “vital characteristic” for nurses in the complex health care system. Resilience is associated with reduced symptoms of burnout, improved mental health, and reduced turnover (Rushton et al., 2015).

Taylor (2019) suggests offering resilience interventions at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. At the primary level, such interventions would focus on building self-awareness, coping skills, and communications skills. At the secondary level, they might include screening for burnout and providing the associated resources and supports nurses will need. Finally, at the tertiary level, interventions would target nurses whose resilience threshold had been breached and support their healing and return to work. Understanding and addressing resilience among nurses holds promise for attenuating the effects of workplace demands that exceed personal resources (Yu et al., 2019). A nurse suicide task force led by ANA9 has been refocused on resilience and is making resources available that can address mental health, particularly during the response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Davidson et al., 2020a).

However, focusing only on individual resilience is insufficient to create workplaces designed to preserve integrity and well-being (Taylor, 2019). Every system, including the human system, has limits beyond which it cannot recover and can become permanently degraded. The challenge is to better understand how to recognize the symptoms of those thresholds and to develop strategies that

___________________

7 Drug diversion is “the deflection of prescription drugs from medical sources into the illegal market” (see https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Fraud-Prevention/MedicaidIntegrity-Education/Downloads/infograph-Do-You-Know-About-Drug-Diversion-%5BApril-2016%5D.pdf [accessed April 13, 2021]).

8 See https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/hospitals/industry-voices-as-covid-19-flare-ups-continue-healthcare-organizations-must-double-down (accessed April 13, 2021).

9 See https://www.nursingworld.org/get-involved/share-your-expertise/pro-issues-panel/moral-resilience-panel (accessed April 16, 2021).

support human systems, teams, and organizations in adapting healthfully to the adversities they inevitably encounter by modifying those characteristics that are amenable to intervention (Moss et al., 2016). In addition to improving the resilience of individuals, organizations can seek to identify and ameliorate the negative conditions that systematically undermine health and well-being (Gregory et al., 2018). Barratt (2018) suggests that efforts to improve individual resilience focus on building the resilience of teams and organizations to give individuals the support and resources they need. Resilience is discussed further in the section on system-level approaches later in this chapter.

Mental Health

Promising approaches for fostering nurses’ mental health and well-being include the development of skills in mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral therapy/skills-building interventions. Mindfulness skills are aimed at building awareness of one’s reactions and being able to choose how to respond in the moment. The development of new neuropathways to calm a reactive nervous system is not aimed at tolerating intolerable situations, but at restoring stability so individuals can choose the responses that best reflect their values and commitments. Mindfulness interventions, including mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, are increasingly being used to treat anxiety and depression (Hofmann and Gomez, 2017), and may be particularly effective in fostering self-compassion (Wasson et al., 2020). Recent reviews of RCTs have found that mindfulness-based interventions are effective in treating a range of clinical symptoms and disorders, including anxiety, depression, psychological and emotional distress, and general “quality of life” concerns (Hofmann and Gomez, 2017).

One evidence-based skills-building intervention based on cognitive-behavioral therapy that integrates mindfulness—MINDBODYSTRONG—(adapted from the COPE cognitive-behavioral skills-building intervention) is delivered by a nurse to new nurse residents. MINDBODYSTRONG comprises eight weekly sessions focused on caring for the mind, caring for the body, and building skills (Sampson et al., 2020). Evidence from an RCT supports MINDBODYSTRONG’s efficacy in improving mental health, healthy lifestyle beliefs, healthy lifestyle behaviors, and job satisfaction (Sampson et al., 2019), sustaining its positive impacts over time (Sampson et al., 2020).

In a recent systematic review, Melnyk and colleagues (2020) found that interventions involving mindfulness and those using cognitive-behavioral therapy were effective in addressing stress, anxiety, and depression in clinicians (Melnyk et al., 2020). Deep breathing and gratitude interventions also showed promise. These findings are consistent with those of other reviews (e.g., Lomas et al., 2018). The programs reviewed by Melnyk and colleagues (2020) typically included eight weekly 1- to 2.5-hour sessions plus about 9 hours of mindfulness

practice at home; however, the authors conclude that these programs were potentially too time-intensive for clinicians to accommodate within their schedules. They also note that many hospitals do not have mindfulness trainers available to implement these programs.

Given the challenges of implementing time-intensive interventions highlighted by Melnyk and colleagues (2020), there is also promising evidence that brief mindfulness interventions may have positive impacts on compassion, although Hofmann and Gomez (2017) observe that it is unclear whether brief interventions can have the same kind of impact on anxiety and depression as that of the longer interventions. Box 10-4 describes promising interventions that use mobile technologies to support mindfulness and other well-being skills.

Another promising approach to early screening and treatment is the Healer Evaluation Assessment and Referral (HEAR) program, first piloted with nurses in 2016 (Davidson et al., 2018b, 2020b). This program, a collaboration between the University of California, San Diego, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, includes a set of educational presentations focused on burnout, depression, and suicide, as well as an encrypted and confidential web-based assessment tool designed to identify and refer individuals at risk for depression and suicide. The pilot assessment showed it to be an effective screening tool (Davidson et al., 2018b). Three years after the pilot, 527 nurses have been screened, with 9 percent of those screened expressing thoughts of taking their own life; 176 nurses have received treatment, and 98 have accepted referrals for treatment.

Ethical Competence

Organizations are investing in programs aimed at building mindfulness, ethical competence, and resilience through experiential and discovery learning, simulation, and communities of practice (Brown and Ryan, 2003; Grossman et al., 2004; Rushton et al., 2021; Shapiro et al., 2005; Singleton et al., 2014). These programs, coupled with programs aimed at cultivating nurses’ competencies to address ethical concerns through systematic processes that engage the voice of the front line and provide nurses with skills for constructively and confidently raising their concerns, are important leverage points for creating workplaces where moral resilience is fostered and ethical practice is routine (Grace et al., 2014; Hamric and Epstein, 2017; Robinson et al., 2014; Rushton et al., 2021; Trotochaud et al., 2018; Wocial et al., 2010). These resources also need to be aligned with system changes that remove the impediments to nurses’ well-being and integrity and build moral community (Hamric and Wocial, 2016; Liaschenko and Peter, 2016; Traudt et al., 2016). Adopting systematic methods for building a culture that fosters ethical practice and integrity by investing in structural elements and processes in health care organizations will be essential to amplify interventions aimed at building individual capacities (Nelson et al., 2014; Pavlish

et al., 2020). These efforts are synergistic with those aimed at building psychological safety (Nelson et al., 2014) and models of just culture for safe, quality care.

Incivility, Bullying, and Workplace Violence

In its 2015 position statement (ANA, 2015), ANA articulated the responsibilities of both individual nurses and employers in ending workplace bullying, incivility, and workplace violence. With regard to bullying, Rutherford and colleagues (2019) conducted an integrative review of studies of interventions addressing the bullying of prelicensure nursing students and nursing professionals, finding that those interventions fell into three main categories: education, nurses as leaders, and policy changes. The authors conclude that educational interventions are important to reducing or eliminating bullying behavior and may be of the most benefit to students. These types of interventions range from journaling to teaching nurses how to address being a target of bullying or incivility.

One intervention, described by Aebersold and Schoville (2020), used role play simulations with debriefing sessions and an educational component with senior-level undergraduate nursing students. Preliminary qualitative evidence from this intervention indicated that simulation can be an effective strategy for addressing incivility and bullying in the workplace, although this was a small pilot study with a convenience sample of nursing students. Pfeiffer and Vessey (2017) conducted an integrative review of bullying and lateral violence (BLV) among nurses in Magnet® accredited health care organizations.10 The authors found that a variety of terms were used to describe BLV, making it difficult to synthesize and compare findings across studies. Although Magnet accreditation standards promote a model of collegiality and teamwork, BLV remains prevalent and exists in both Magnet and non-Magnet organizations. Pfeiffer and Vessey (2017) call for more studies examining the prevalence of BLV in these accredited organizations and also more research aimed at better understanding factors within organizations and interventions that can effectively reduce the occurrence of BLV. In sum, the level of evidence for the effectiveness of bullying interventions among nurses is limited and there is a need for rigorous, well-designed RCTs to build this evidence base; multiple, stratified interventions may be needed (Rutherford et al., 2019).

As mentioned previously, workplace violence is also a concern for nurses, particularly those who work in emergency department settings (Gillespie et al., 2014a,b). Interventions that have been developed to address workplace violence include a hybrid educational intervention with online and classroom components (Gillespie et al., 2014a) and a multicomponent intervention that includes environmental changes, education, training, and changes in policies and procedures

___________________

10 These are health care organizations that are accredited through the American Nurses Credentialing Center. This model is considered to be the gold standard for nursing (Pfeiffer and Vessey, 2017).

(Gillespie et al., 2014b), although these are not strictly focused on nurses. The hybrid educational intervention showed promise with a small sample of employees from a pediatric emergency department, with the research team concluding that to achieve significant learning and retention, the hybrid model is preferred. The multicomponent intervention was promising, but only two of six sites reported significant decreases in violent events. The authors also note that emergency department workers did not report most of the violent events that occurred because of such factors as time constraints and fear of being blamed (Gillespie et al., 2014b). There is a need for more research to examine how to ameliorate workplace violence among health care workers, and for replication and rigorous RCTs of promising interventions.

Racism, Prejudice, and Discrimination

As discussed in Chapter 4, there has been a shift in patient care settings away from cultural competency toward cultural humility, and toward a focus on a lifelong approach to learning about diversity and the role of individual bias and systemic power in health care interactions. Specific approaches to weaving cultural humility concepts into nursing and interprofessional education are discussed in Chapter 7. In addition, as noted in Chapter 7, research on the efficacy of interventions designed to reduce implicit bias has found that many of these interventions are ineffective, and some may even increase implicit biases (FitzGerald et al., 2019). Chapter 7 describes an evidence-based intervention, the prejudice habit-breaking intervention (Cox and Devine, 2019; Devine et al., 2012), that has been tested in RCTs and is aimed at overcoming bias through conscious self-regulation or breaking the bias “habit.” Reducing prejudice and discrimination may also be possible through simple and brief interventions, such as 10-minute nonconfrontational conversations, although more research is needed to test such interventions with racial outgroups (Williams and Cooper, 2019).

Another concept that can be considered in relationship to well-being is that of “wellness as fairness” (Prilleltensky, 2012). As described in earlier chapters of this report, nurses are being called on to dismantle racism and to advance the social mission of making health better and fairer. Similarly, in the public health field, it is acknowledged that a focus on both individual personal transformation and structural change is needed to detect, confront, and prevent racism (Margaret and Came, 2019). Margaret and Came (2019, p. 317) note that White public health practitioners can become allies in antiracism work by addressing the following three interdependent and overlapping areas: “(1) understanding and addressing power; (2) skills for working across difference; and (3) building and sustaining relationships.” Rigorous, well-designed studies are needed to test these and other promising approaches with nurse educators, nursing students, and practicing nurses.

Systems-Level Approaches

The responsibility for nurse well-being is shared between individual nurses and those who shape the environment in which they practice. Individual nurses’ dedication to their own well-being is enhanced by the support of the system, its leaders, and a culture in which well-being is prioritized. The 2019 National Academies report on clinician burnout makes clear that while interventions focused on individuals have their place, these strategies alone are insufficient to address the systemic contributions to the factors that erode clinician well-being (NASEM, 2019a). The evidence demonstrates that integrated, systematic, organization-focused interventions are more effective at reducing burnout and improving well-being. A systems approach focuses on the structure, organization, and culture of workplaces (Dzau et al., 2018; Shanafelt and Noseworthy, 2017; Shanafelt et al., 2017), and considers the complex interplay of factors that impact well-being and other outcomes (NASEM, 2019a; Plsek and Greenhalgh, 2001; Rouse, 2008).

An integrated and systematic approach requires the involvement of a broad range of stakeholders, including nurse leaders, educational institutions, health care organizations and other employers of nurses, policy makers, and professional associations. Some stakeholders will have the capacity to make sweeping changes to policies and work environments, while others will focus more on facilitating individual and team well-being. Because the factors that contribute to burnout and poor well-being are multiple, varied, complex, and context-dependent, efforts on all levels and in all areas are welcome and necessary. The National Academy of Medicine’s (NAM’s) Clinician Well-Being Knowledge Hub has detailed, illustrative case studies from the Virginia Mason Kirkland Medical Center, and The Ohio State University’s Colleges of Medicine and Nursing, Emergency Medicine Residency Program, and Wexner Medical Center.11

Stakeholder actions could include restructuring systems and implementing initiatives to prevent burnout, reduce administrative burden, enable technological solutions to support the provision of care, reduce the stigma and barriers that prevent health professionals from seeking support, and increase investment in research on clinician well-being (NASEM, 2019a). All stakeholders can consider the role technology can play in improving well-being (see Box 10-4). Well-being initiatives will vary considerably based on the setting and role of nurses; for example, nurses who are working directly with patients during a pandemic disease outbreak will have different needs and wants from those of nurses who are leading community efforts to change housing policies. This section describes how different stakeholders—nurse leaders, educational institutions, employers, policy makers, and nursing associations and organizations—can continue working toward improving nurse well-being, and provides several examples of action in these areas.

___________________

11 See https://nam.edu/clinicianwellbeing/case-studies (accessed April 13, 2021).

Nurse Leaders

Nurse leaders have the potential to dramatically impact nurse well-being by shaping the day-to-day work life of nurses, setting the culture and tone of the workplace, developing and enforcing policies, and serving as exemplars of well-being (Ross et al., 2017). The leadership style and effectiveness of nurse leaders have been associated with outcomes including the health of the work environment, patient outcomes and mortality, job satisfaction, work engagement, burnout, and retention (Bamford et al., 2013; Boamah et al., 2018; Cummings et al., 2010a,b; Rushton and Pappas, 2020; Spence Laschinger and Fida, 2014; Spence Laschinger et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2018). Nurse leaders have a responsibility to create a safe work environment with a culture of inclusivity and respect, and to implement and enforce strong policies to protect nurses. In particular, nurse leaders must be skilled in recognizing signals of toxicity and strategically responding to them (Rutherford et al., 2019). This responsibility is not limited to acute care or hospital settings; nurses on all fronts and at every point in the workforce pipeline deserve support from their leaders.

The specific ways in which leaders can impact nurse well-being depend on their role and scope of authority and responsibility. Nurse executives with influence over organizational policies can advocate for adequate pay and benefits, and address staffing and scheduling issues to prevent nurses from being overworked. Nurse leaders who manage teams can support well-being by addressing workplace safety and incivility and bullying, and by creating a culture in which all nurses feel supported and respected (Spence Laschinger et al., 2009). For example, leaders could implement a “see something, say something” program in which nurses are encouraged to report any unsafe workplace conditions, including violence and bullying.

Nurse leaders can also use their position to serve as educators and role models for their staff (NASEM, 2019a; Ross et al., 2017). They might do so by, for example, investing in programs aimed at developing resilience skills, teaching skills based on cognitive-behavioral therapy, creating norms of self-care within the work day, and setting firm work–life boundaries for self and staff. The effects of stress and trauma related to the COVID-19 pandemic will impact the workforce at both the individual and staffing levels for years to come, and leaders will need vigilance and a long-term strategy to build the health of the teams providing care.

For example, Menschner and Maul (2016) report that some community-based health care organizations and health care networks are fostering a healthy life–work balance by encouraging employees to leave work mobile phones in the office after their shifts and ensuring that they do not work beyond their designated 40 hours. Nurse leaders can also serve as role models by examining their own health promotion behaviors and maintaining their own health and well-being (Ross et al., 2017). And they can be advocates for making environmental changes

in the workplace, such as by holding standing or walking meetings, advocating for healthy work schedules, or implementing programs to help nurses cope with the stresses of work.

Leadership can be particularly important during times of transition and challenge. For example, during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic,12 health centers with level-headed, disciplined, and unified leadership were able to quickly implement plans, limit confusion, and prepare staff for the changes ahead (Canton and Company, 2020). Rosa and colleagues (2020) outline steps for nurse leaders to take to promote health system resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. These include specific local and organizational recommendations aimed at mitigating burnout and moral suffering and building a culture of well-being. The transition associated with integrating SDOH and health equity further into nursing practice will not be as swift or as bleak as the transition to COVID-19 care, but it will similarly require strong leadership and steady hands to guide the way and advocate for nurse well-being amid the changes (Rosa et al., 2020). Nurse leaders will be essential in helping to shift the priorities and workflow of nurses and to supporting nurses through this transition (AHA, 2020b).

Educational Institutions

The foundation for nurse well-being starts long before nurses enter the workplace. While more data are available on the poor well-being of medical students, research suggests that nursing students are similarly stressed out, exhausted, and disengaged (Michalec et al., 2013; Rudman and Gustavsson, 2012). While evidence on burnout and poor well-being among nursing students is quite limited (NASEM, 2019a), there is an emerging body of evidence on the important role of resilience (see also the earlier discussion of resilience in the section on individual-level interventions). Resilience of prelicensure nursing students has a significant inverse relationship with academic intention to leave (Van Hoek et al., 2019) and moral distress (Krautscheid et al., 2020). Strategies to support resilience include positive reframing (Amsrud et al., 2019; Mathad et al., 2017; Stacey et al., 2020; Thomas and Revell, 2016), reflection (He et al., 2018), and mindfulness (Stacey et al., 2020). Integration points for resilience within the clinical and didactic components of curricula are needed for sustainable impact on nursing student behavior (Cleary et al., 2018). In a recent systematic review of resilience among health care professions, Huey and Palaganas (2020) outline individual, organizational, and environmental factors that impact student resilience and promising interventions. Further work is needed to understand the relationship among factors that support well-being

___________________

12 The American Hospital Association developed a workforce checklist for use by leaders to consider how they can support their workforce during the pandemic. See https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/07/aha-covid19-pathways-workforce.pdf (accessed April 13, 2021).

and resilience among nursing students in all programs of study (Stephens, 2013; Thomas and Revell, 2016).

Nursing educational institutions have a responsibility to ensure students’ well-being, and to impart to them the skills and resources necessary for well-being throughout their nursing career. Consistent with the recommendations of the National Academies report focused on addressing burnout (NASEM, 2019a), educational institutions, like health care organizations, can invest in interventions that build individual resilience and well-being while dismantling the impediments within the system itself. This process begins with executive leadership and faculty commitment to a learning culture in which systems, processes, incentives, rewards, and resources are aligned to amplify rather than degrade well-being. One way to accelerate change is through investment in a leadership position assigned the role of championing individual and system alignment of well-being activities. Routine assessment of well-being and factors known to undermine it is then conducted annually, with leadership accountable for remediating modifiable factors and expanding efforts to deepen culture change. These strategies, recommended in the National Academies report (NASEM, 2019a), require attention to supporting faculty, staff, and students in contributing to a culture of well-being as a strategic priority.

As part of the effort to make well-being an institutional priority, conscious attention is needed to creating a culture in which well-being and integrity are not an afterthought but are integrated throughout the curriculum in visible and meaningful ways. Specific inclusion of content that links nursing students’ well-being to the profession’s Code of Ethics reinforces that self-stewardship is an ethical imperative rather than an optional activity (ANA, 2015). Including program outcomes focused on well-being and ethical competence is a tangible way to elevate the importance of developing and sustaining well-being as a foundational skill for the nursing profession, as explicitly reflected in the American Association of Colleges of Nursing’s Essentials13 for nursing education. Faculty, like students, require expanded resources that enable them to embody their commitment to well-being and serve as role models and coaches for students (Feeg et al., 2021; Robichaux, 2012). Statewide, regional, and national initiatives to build capacity among faculty and students in these foundational areas are vital.

There are a variety of concrete ways in which nursing schools can facilitate student well-being (see Box 10-5)—for example, by ensuring that the workload is reasonable, providing easy-to-access support and mentoring for students, setting a culture and an example of well-being, and teaching self-care and mindfulness skills, such as reflective practice, journaling, or various forms of artistic expression (Song and Lindquist, 2015). These skills can be integrated throughout the curriculum with reinforcement at regular intervals. For these interventions to be

___________________

13 See https://www.aacnnursing.org/Education-Resources/AACN-Essentials (accessed April 13, 2021).

effective, it will be necessary for nursing education organizations to carefully assess the impact of recruitment narratives and organizational norms that conflate perfectionism with excellence, establish patterns of unhealthy competition, or reinforce systemic racism or social injustice. Such an assessment requires scrutinizing grading and pedagogical practices, encouraging a diversity of learning styles, and eliminating norms of chronic overwork as the standard to be achieved. Attention is needed to how faculty norms and behaviors impact the adoption of those norms by students. For example, students who witness exhausted and overworked faculty who do not demonstrate investment in their own health and well-being experience dissonance when those same faculty urge them to adopt healthy habits and well-being practices.

Nursing students’ well-being can also be enhanced by advancing opportunities for interdisciplinary education and interventions aimed at fostering professionalism and interprofessional practice to support well-being (IOM, 2014). Currently, core competencies for both interprofessional14 and single-discipline15 education lack robust requirements for developing capacities that enable well-be-

___________________

14 See https://www.aacom.org/docs/default-source/insideome/ccrpt05-10-11.pdf?sfvrsn=77937f97_2 (accessed April 13, 2021).

15 See https://www.aacnnursing.org/Education-Resources/AACN-Essentials (accessed April 13, 2021).

ing and integrity. Often when included, such content is elective or optional. However, there are signs of progress, animated by concerns about the detrimental effects of the learning environment and recommendations to redress them (Larsen et al., 2018). Interprofessional initiatives, such as the NAM’s Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience,16 represent a coordinated method for learning with and from colleagues (IOM, 2014).

Employers

Organizations that employ nurses—including hospitals, nursing homes, schools, prisons, community organizations, and others—play a major role in shaping the conditions that promote nurse well-being or the lack thereof. In the framework for burnout and well-being shown earlier in Figure 10-1, there are a number of areas in which employers can make an impact.

First, an organization’s leadership, governance, and management can make monitoring and improving nurse well-being a priority and be accountable for making the organizational changes necessary to dismantle the impediments to achieving that priority. This includes alignment of budgeting with desired outcomes of improved well-being in the nursing workforce. Nurses are also well equipped to take on roles as chief wellness officers in health care systems (Kishore et al., 2018).

Second, an organization can shape the environment, culture, and policies that affect nurses. An organization can redesign the work system so that nurses have adequate resources (e.g., staffing, scheduling, workload, job control, physical environment), and design systems that encourage and facilitate interprofessional collaboration, communication, and professionalism (NASEM, 2019c). For example, a health care organization can ensure that nurses not only have sufficient PPE, but also “psychological PPE” (see Box 10-6).

Third, employers can help support individual nurses in bolstering personal capabilities that may modify the effects of work systems on well-being; for example, employers can offer education, resources, and training in mindfulness, resilience, and healthy habits.

As discussed previously, for individual approaches to be effective, they must be coupled with redesign of organizational processes, structures, and policies to animate sustainable culture shifts that make interventions feasible and normative (Rushton and Sharma, 2018; Stanulewicz et al., 2020). For example, if an organization encourages nurses to use meditation to decompress during shifts but organizational culture frowns on nurses taking breaks, the initiative is likely to have limited impact. End users of these initiatives (front-line nurses) can be engaged proactively in designing a diversity of resources that they perceive to be valuable in fostering their well-being rather than having such resources

___________________

16 See https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being (accessed April 13, 2021).

imposed on them (Richards, 2020). The Wikiwisdom™ Forum: Wisdom from Nurses (Richards, 2020) is one such effort, sponsored by New Voice Strategies, the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, and the American Journal of Nursing to facilitate online conversations with front-line nurses who are battling the COVID-19 pandemic.

For organizations employing nurses who are dispersed in a community (e.g., public health nurses, school nurses) rather than concentrated in a clinical setting, monitoring and communicating with them about well-being may be even more critical. Nurses in community settings and in clinical settings face different risks; nurses working in the community may deal with, for example, isolation or violence in a patient’s home or neighborhood, and have less opportunity for breaks (Mathiews and Salmond, 2013; Terry et al., 2015). The dispersed nature