2

Social Determinants of Health and Health Equity

As a nurse, we have the opportunity to heal the heart, mind, soul and body of our patients, their families and ourselves. They may forget your name, but they will never forget how you made them feel.

—Maya Angelou, author, poet, and civil rights activist

Compared with any other country in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the United States spends more money on health care and still has the highest poverty rate measured by the OECD, the greatest income inequality, and some of the poorest health outcomes among developed countries (Escarce, 2019). For a variety of reasons, low-income individuals, peo-

ple of color (POC), and residents of rural areas in the United States experience a significantly greater burden of disease and lower life expectancy relative to their higher income, White, and urban counterparts, and this gap has been growing over time (Escarce, 2019). The roots of these inequities are deep and complex, and understanding them can help elucidate how nurses who currently serve a highly diverse population play a pivotal role in addressing social determinants of health (SDOH)—the conditions in the environments in which people live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks—to improve health outcomes and reduce health inequities. To further that understanding, this chapter provides background on SDOH and highlights social factors that disproportionately affect some communities more than others; Chapters 4 and 5, respectively, describe the role of nurses in addressing these inequities in health and health care. This chapter also describes the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in exacerbating the negative effects of SDOH and health inequities among low-income communities and POC (Garcia et al., 2020; Kantamneni, 2020).

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

The growing evidence for inequities in both health and access to health care has brought added scrutiny to SDOH. The term typically refers to “nonmedical factors influencing health, including health-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors” (such as smoking) (Bharmal et al., 2015, p. 2). Examples of SDOH also include education, employment, health systems and services, housing, income and wealth, the physical environment, public safety, the social environment (including structures, institutions, and policies), and transportation (NASEM, 2019b).

SDOH have consequences for the economy, national security, business, and future generations (NASEM, 2017). Box 2-1 lists SDOH in five areas defined by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—economic stability, education, social and community context, health and health care, and neighborhood and built environment.

SDOH affect everyone. They include both the positive and negative aspects of the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. At their best, SDOH can be protective of good health. Many people, however, exhibit a pattern of social risk factors (the negative aspects of SDOH) that contribute to increased morbidity and mortality (NASEM, 2019a).

A concept related to SDOH is social needs—individual-level nonmedical acute resource needs related to SDOH, such as housing, reliable transportation, and a strong support system at home, that must be met for individuals to achieve good health outcomes and for communities to achieve health equity (NASEM, 2019a; Nau et al., 2019). Social needs are a person-centered concept that incor-

porates each person’s perception of his or her own health-related needs, which therefore vary among individuals (NASEM, 2019a). The nursing community has long focused on the social needs of people and communities, and has worked closely with social workers and community health workers to address individuals’ more complex social needs (Foster et al., 2019; Gordon et al., 2020). Nurse-designed models of care, discussed throughout this report, often successfully integrate the social needs of individuals and families, as documented in a recent RAND report (Martsolf et al., 2017).

Improving population health (e.g., through measures that improve life expectancy) means improving health for everyone. However, historically disadvantaged groups trail dramatically behind others by many measures of health. Health equity is achieved by addressing the underlying issues that prevent people from being healthy. At the population level, health equity can be achieved by addressing SDOH, while at the individual level, it can be achieved by addressing social needs. Health equity benefits everyone through, for example, economic growth, a healthier environment, and national security. At both the population and individual levels, work to improve health and health equity will require cross-sector collaborations and, where necessary, enabling policies, regulations, and community interventions.

Conceptual Frameworks for the Social Determinants of Health

Several frameworks have been developed to explain the interactive nature of how social factors can contribute to health. These frameworks help health professionals and others understand and address SDOH to reduce health disparities and improve health equity. Two important frameworks—the conceptual SDOH framework developed by the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Commission on the Social Determinants of Health and the Social Determinants of Health and Social Needs Model of Castrucci and Auerbach (2019)—are described below to show the relationship between health and social factors and strategies for improving health and well-being, providing context for the report’s focus on the nurse’s role in addressing health and health care equity.

Conceptual Social Determinants of Health Framework of the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health

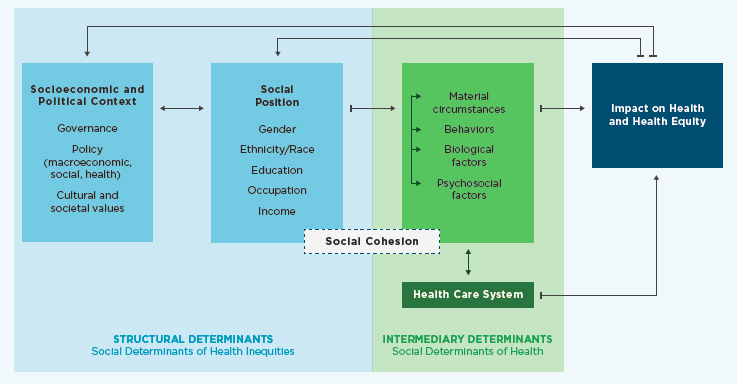

In 2010, WHO’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health developed a widely used conceptual framework designed to explain the complex relationships between social determinants and health (see Figure 2-1). This framework divides SDOH into two categories: structural determinants, defined as SDOH inequities, such as socioeconomic and political context, social class, gender, and ethnicity; and intermediary determinants, defined as such SDOH as material circumstances, psychosocial circumstances, and behavioral and biological factors.

The WHO model shows how inequities created by policies and structures (structural determinants) underlie community resources and circumstances (intermediary determinants). In this model, social, economic, and political mechanisms contribute to socioeconomic position, characterized by income, education, occupation, gender, race/ethnicity, and other factors that reflect social hierarchy and status. Social standing is related to an individual’s exposures and vulnera-

SOURCE: Adapted from Solar and Irwin, 2010.

bility to health conditions. Those structural determinants shape the intermediary determinants—material conditions (e.g., living and working conditions, food security), behaviors and biological factors (e.g., alcohol and tobacco consumption, physical activity), and psychosocial factors (e.g., social support, psychosocial stress) that underlie health. All of these factors impact health, and health can also create a feedback loop back to the structural determinants. For example, poor health or lack of education can impact an individual’s employment opportunities, which in turn constrains income. Low income reduces access to health care and nutritious food and increases hardship (NEJM Catalyst, 2017; Solar and Irwin, 2010).

The health care system falls in the framework as an intermediary determinant. The impact of the health care system creates another layer of determinants based on differences in access to and quality of care. By improving equitable access to health care and creating multisector solutions to improve health status—such as access to healthy food, transportation, and linkage to other social services as needed—the health care system can address disparities in health (Solar and Irwin, 2010). Furthermore, the health care system provides an opportunity to mediate the indirect consequences of poor health related to deteriorating social status (Solar and Irwin, 2010). Understanding the complex relationship between SDOH and health is essential in order for nurses to address health equity. Accordingly, Chapter 9 highlights the importance of transforming nursing curriculum and continuing education by integrating SDOH to improve health equity.

Social Determinants of Health and Social Needs Model

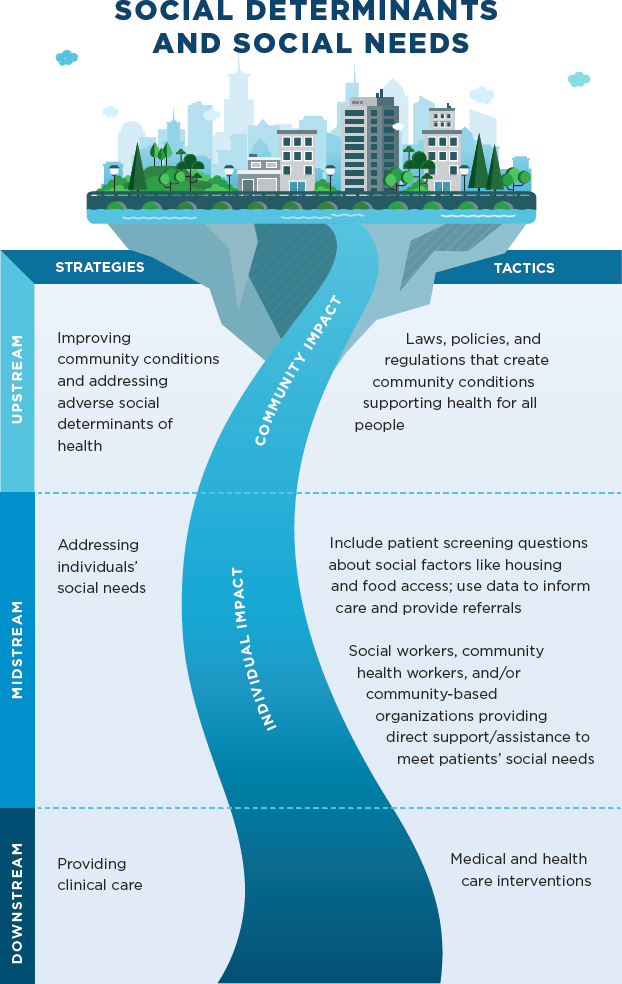

Throughout this report, the committee uses the Social Determinants of Health and Social Needs Model of Castrucci and Auerbach (2019) to describe the upstream, midstream, and downstream strategies used by nurses to improve individual and population health (see Figure 2-2). Upstream factors represent SDOH and affect communities in a broad and inequitable way. Low educational status and opportunity, income disparity, discrimination, and social marginalization are upstream factors that prevent good health outcomes. For example, nurses engage in upstream factors by informing government policies at the local and federal levels. Midstream factors represent social needs, or the individual factors that might affect a person’s health. These are specific nonmedical acute resource needs that lie on the causal path between SDOH and health inequities (Nau et al., 2019). Midstream factors that might prevent a person from achieving optimal health include homelessness, food insecurity, poor access to education, and trauma. Through midstream efforts, nurses focus on preventing disease and meeting social needs—for example, in federally qualified health centers or through public health departments—by screening for such social risk factors as lack of housing and food access and using these data to inform referrals to government and community resources related to the identified social needs. Activities addressing downstream factors include disease treatment and chronic disease management, in which nurses typically engage in settings where health care is delivered, from homes to urgent care clinics to hospitals. Nursing research typically focuses on downstream and midstream factors.

The majority of nurses work in hospitals and clinics; therefore, most work midstream and downstream providing individual-level interventions to patients. Nonetheless, an understanding of the interrelationships among upstream, midstream, and downstream factors and interventions is necessary to fully comprehend and influence the health of individuals and communities. Moreover, all nurses have the opportunity to work upstream through advocacy for policy changes that promote population health. To engage robustly at all three levels, however, nurses need education, training, and support. The following sections review SDOH and social needs at all three levels of this model, along with their health implications.

HEALTH IMPLICATIONS OF SOCIAL FACTORS

This section describes social factors into which people are born, that may change as they age, and that have implications for health outcomes. Additionally, it describes factors in the places where people live, including housing and homelessness, food insecurity, environmental factors, and geography/rurality, that also affect health outcomes. Before proceeding, it is important to note that social determinants intersect, with further implications for health (see Box 2-2).

SOURCE: Adapted from Castrucci and Auerbach, 2019.

Race and Racism

Racism, a structural inequity that negatively impacts health and health equity, is “an organized social system in which the dominant racial group, based on an ideology of inferiority, categorizes and ranks people into social groups called ‘races’ and uses its power to devalue, disempower, and differentially allocate val-

ued societal resources and opportunities to groups defined as inferior” (Williams et al., 2019, p. 106). Williams and colleagues describe three interrelated forms of racism: structural racism, cultural racism, and discrimination.

Structural racism is racism that is embedded in laws, policies, and institutions and provides advantages to the dominant racial group while oppressing, disadvantaging, or neglecting other racial groups (Williams et al., 2019). Structural racism can be seen in residential segregation, the criminal justice system, the public education system, and immigration policy. Williams and colleagues identify structural racism as the most important way in which racism impacts health. A robust body of evidence on the link between residential segregation and poor health, for example, shows that segregation is associated with outcomes that include low birthweight and preterm birth (Mehra et al., 2017) and lower cancer survival rates (Landrine et al., 2017). However, methodological limitations can make structural racism a challenging topic to study. Researchers have developed some novel measures of the phenomenon, including one that combines indicators of political participation, employment and job status, educational attainment, and judicial treatment (Lukachko et al., 2014). In this study, structural racism is defined by state-level racial disparities across those four domains. Using this measure, the researchers found that Blacks living in states with high levels of structural racism were more likely to experience myocardial infarction relative to Blacks living in states with low levels of structural racism (Lukachko et al., 2014). Another group of researchers developed a measure of state-level structural racism that combines indicators of residential segregation, incarceration rates, educational attainment, economic indicators, and employment status. This study found that higher levels of structural racism were associated with a larger disparity between Black and White victims of fatal police shootings (Mesic et al., 2018).

Structural racism has also contributed to the high incarceration rate in the United States, which exceeds the rates of other countries in which POC make up the majority of the population (Acker et al., 2019). Mass incarceration is a public health crisis that disproportionately impacts Black and Hispanic individuals and their families and communities (Brinkley-Rubinstein and Cloud, 2020; Carson, 2020). Individuals who are incarcerated have greater chances of developing chronic health conditions and are exposed to factors, including overcrowding, poor ventilation and sanitation, stress, and solitary confinement, that exacerbate chronic conditions and impact long-term physical and mental health (Acker et al., 2019; Kinner and Young, 2018). Evidence shows that following incarceration, mortality rates increase significantly, and individuals also face limited opportunities in employment, housing, and education (Massoglia and Remster, 2019).

The second form of racism, cultural racism, is the “instillation of the ideology of inferiority in the values, language, imagery, symbols, and unstated assumptions of the larger society” (Williams et al., 2019, p. 110). Through cultural racism, people absorb and internalize negative stereotypes and beliefs about race,

which can both create and support structural and individual racism and create implicit biases (Williams et al., 2019). Implicit bias can in turn lead to unintentional and unconscious discrimination against others. Important in the context of this study is that implicit bias has been shown to be prevalent in health care (FitzGerald and Hurst, 2017; Hall et al., 2015) and to result in disparate outcomes among individuals of different races. For example, some research suggests that women of color are less likely than their White counterparts to receive an epidural during childbirth because of providers’ beliefs about the relationship between race and pain tolerance, as well as poor communication in racially discordant provider–patient relationships (NASEM, 2020). Research has also shown that providers perceive Black individuals as less likely than White individuals to adhere to medical advice, a perception that contributes to poor communication and care (Laws et al., 2014; Van Ryn and Burke, 2000). These experiences of implicit bias, together with a long history of unethical treatment of POC in the health care system, can lead to mistrust and avoidance of the system, thus exacerbating health disparities (Chaturvedi and Gabriel, 2020).

Discrimination is the third—and most researched—form of racism. It occurs when people or institutions treat racial groups differently, with or without intent, and this difference results in inequitable access to opportunities and resources (Williams et al., 2019). Self-reported discrimination, in which the discrimination is perceived by the individual being discriminated against, is often used as an indicator of racism in studies on health care and health outcomes. Self-reported discrimination is believed to impact health by triggering emotional and physiological reactions and by changing an individual’s health behaviors (Williams et al., 2019). It has been associated with poor health in multiple areas, including mental health (Paradies et al., 2015), sleep (Slopen et al., 2016), obesity (Bernardo et al., 2017), hypertension (Dolezsar et al., 2014), and cardiovascular disease (Lewis et al., 2014). In addition to the actual experience of discrimination, just the threat of discrimination—and the associated hypervigilance—can negatively impact health. Discrimination can also be experienced through microaggressions, defined as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color” (Sue et al., 2007, p. 273). Microaggressions have been correlated with outcomes that include poor mental health (Cruz et al., 2019), poor physical health (Nadal et al., 2017), and sleep disturbance (Ong et al., 2017). Moreover, microaggressions that are experienced within the health care setting may undermine the provider–patient relationship and thus the quality of care (Cruz et al., 2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the issue of racism as a social determinant into sharp focus, illuminating the mechanisms by which it affects health outcomes. COVID-19 has disproportionately affected Black Americans, Hispanic

Americans/Latinos, and American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) (Cuellar et al., 2020). Blacks have been more likely to be diagnosed with COVID-19 and more likely to die relative to people of other races. The death rates for COVID-19 among Blacks reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are higher than the rates for non-Hispanic Whites, AI/ANs, Asians, and Hispanics/Latinos (CDC, 2020a). Van Dorn and colleagues (2020) also report disproportionately high rates of COVID-19 deaths among African Americans. As of April 2020, when their article was published, three-quarters of all COVID-19 deaths in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, had occurred among African Americans, who also accounted for all but three COVID-related deaths in St. Louis, Missouri. Still, according to CDC, COVID-19 cases were 3.5 times higher among AI/ANs and 2.8 times higher among Hispanics/Latinos than among non-Hispanic Whites (CDC, 2020b). Van Dorn and colleagues (2020) point out that AI/AN populations have disproportionately high levels of such underlying conditions as heart disease and diabetes that make them more susceptible to the virus, and the Indian Health Service (IHS), which provides health care for the 2.6 million AI/ANs living on tribal reservations, has only 1,257 hospital beds and 36 intensive care units across the United States, so that many people covered by the IHS are hours away from its nearest facility (van Dorn et al., 2020).

Research on the specific mechanisms behind these disparities is ongoing, but there are many potential explanations for the link between race and COVID-19 outcomes. Camara Phyllis Jones, past president of the American Public Health Association, posits that POC are more at risk for four reasons (Wallis, 2020). First, they are more exposed to the risk of infection because they are more likely to live in dense neighborhoods, work in front-line or essential jobs, and be incarcerated or held in immigration facilities (see also van Dorn et al., 2020). This set of risk factors is tied to structural racism, including historical and current residential and educational segregation in the United States. Second, POC are less protected from infection because of cultural norms that devalue their lives and their health. Third, POC are more likely to suffer from underlying conditions that put them at risk of poor outcomes once infected. For example, Black Americans are 60 percent more likely to have diabetes and 40 percent more likely to have hypertension relative to their White counterparts (HHS, 2019, 2020). These conditions, says Jones, are due to the context of their lives—the lack of healthy food choices, more polluted air, and few places to exercise safely. Finally, POC are less likely to have access to quality health care (and thus are more likely to experience unnecessary treatments, inaccurate diagnoses, and medication errors), and more commonly face structural and individual discrimination within the health care system. Yancy (2020) echoes this analysis, noting that social distancing—one of the most effective strategies for reducing transmission of COVID-19—is a privilege that is unavailable to many POC because of where they live and work.

The confluence in 2020 of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter1 protests has brought new opportunities for nurses to be involved in dismantling racism. For example, while the American Nurses Association (ANA) issued a position statement in 2018 opposing individual and organizational discrimination (ANA Ethics Advisory Board, 2019), its 2020 resolution took an even stronger stand, calling for an end to systemic racism and health inequities and condemning brutality by law enforcement (ANA, 2020). The executive director of National Nurses United, Bonnie Castillo, stated in June 2020 that “it is racism that is the deadly disease,” as reflected in disparities in health, police killings, housing, employment, criminal justice, and other areas (NNU, 2020). Nurses are attending protests to offer aid to injured protestors, despite the threat of tear gas and rubber bullets (Jividen, 2020).

Income and Wealth

Higher income (earnings and other money acquired annually) is associated with a lower likelihood of disease and premature death (Woolf et al., 2015). The relationship of wealth (net worth and assets) to health outcomes shows a similar relationship with disease and premature death. Studies have found longitudinal associations between higher levels of wealth and better health outcomes that include lower mortality, higher life expectancy, slower declines in physical functioning, and decreased risk of smoking and hypertension (Hajat et al., 2010; Kim and Richardson, 2012; Zagorsky and Smith, 2016). Significant health-related differences exist between the income levels of individuals below 100 percent and above 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

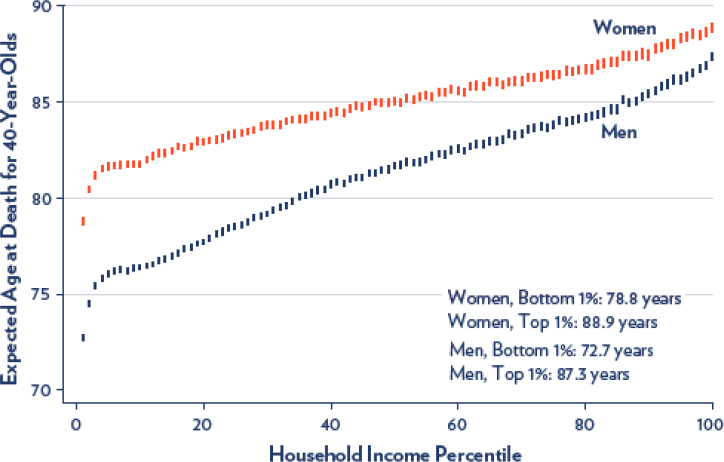

With respect to life expectancy, the expected age at death among 40-year-olds is lowest for individuals with the lowest household income and increases as household income rises (Escarce, 2019). Notably, this is a continuous gradient (see Figure 2-3). Between women in the top 1 percent and the bottom 1 percent of income, there is a 10-year difference in life expectancy. This disparity is greater among men, for whom this gap rises to 15 years. These trends have been worsening over time. Since 2000, individuals in all income groups have gained in life expectancy, but the highest earners have had the highest gains, and the gap in life expectancy between the highest and lowest earners is increasing (Escarce, 2019).

Income correlates highly as well with risk factors for chronic disease and mental health conditions. Relative to people with higher family income, for example, people with lower family income have higher rates of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and hypertension and are more likely to have four or more common chronic conditions (NCHS, 2017). People in families whose income

___________________

1 Black Lives Matter is a global organization whose mission is “to eradicate white supremacy and build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes” (BLM, n.d.).

SOURCES: Escarce, 2019; reproduced from Chetty et al., 2016.

is below 200 percent of the federal poverty level are more likely than people in families with higher income to be obese and to smoke cigarettes. Adults who live in poverty are also more likely to have self-reported serious psychological distress—6.4 percent of those making less than $35,000 feel sadness and 3.8 percent feel worthlessness, compared with 1.3 percent and 0.6 percent, respectively, of those making $75,000–$99,999 (Weissman et al., 2015; Woolf et al., 2015).

In addition to impacting the safety and quality of neighborhoods and schools, parental income and wealth can affect the resources and support available within families (Chetty and Hendren, 2018). Children in low-income families typically face barriers to educational and social opportunities, which in turn limits their social mobility and good health as adults (Braveman et al., 2018; Killewald et al., 2017; Odgers and Adler, 2018; Owen and Candipan, 2019). As health and socioeconomic disadvantages accumulate over a person’s lifetime, this pattern of inequity, exacerbated by structural barriers, can persist across generations, preventing intergenerational social mobility (Braveman et al., 2018; Chetty et al., 2014).

Access to Health Care

Equitable access to health care is needed for “promoting and maintaining health, preventing and managing disease, reducing unnecessary disability and

premature death, and achieving health equity” (ODPHP, 2020b). Evidence shows that access to primary care prevents illness and death and is associated with positive health outcomes (Levine et al., 2019; Macinko et al., 2007; Shi, 2012). Access to health care services is therefore an important SDOH, and inequities in multiple factors, such as a lack of health insurance coverage and limited availability of health care providers, limit that access.

Studies have shown that individuals without health insurance are much less likely to receive preventive care and care for major health conditions and chronic diseases (Cole et al., 2018; Seo et al., 2019). In a study of nonelderly adult patients, insured versus uninsured individuals were more likely to obtain necessary medical care, see a recommended specialist, see a mental health professional if advised, receive recommended follow-up care after an abnormal pap test, and get necessary prescription medications (Cole et al., 2018). Lack of insurance is also associated with a lower likelihood of receiving treatments recommended by health care providers and longer appointment wait times (Chou et al., 2018; Fernandez-Lazaro et al., 2019). In one study, two groups posing as new patients discharged from the emergency department requested follow-up appointments. Those who claimed commercial insurance were more likely than the Medicaid-insured group to receive care within 7 days (Chou et al., 2018).

Wide income and racial/ethnic inequities in insurance coverage therefore have a significant effect on access to health care services, thus influencing health equity. In the United States, African American and Hispanic individuals have a higher risk of being uninsured relative to non-Hispanic Whites (Artiga et al., 2020). Census Bureau data indicate that Hispanics face the greatest barriers to health insurance: between 2017 and 2018, the uninsurance rate increased from 16.2 to 17.8 percent for Hispanics, from 9.3 to 9.7 percent for Blacks, from 6.4 to 6.8 percent for Asians, and from 5.2 to 5.4 percent for non-Hispanic Whites (Barnett et al., 2019). American Indians have high uninsured rates; CDC reports that 28.6 percent of these individuals under age 65 are uninsured (HHS, 2018). It is important to note that uninsured people often delay or forgo care because of its cost and are less likely than those with insurance to have a usual source of care or receive preventive care (Amin et al., 2019), which can lead them to experience serious illness or other health problems. Chapter 4 provides information on nursing’s role in expanding access to health care.

Access to Education

Lower-income families often live in school districts that are resource-poor, and they lack the resources available to upper-income families for making investments in early childhood enrichment activities. Over time, the gap between the rich and poor with respect to receiving higher education has widened. Children born in 1979–1982 were 18 percent more likely to complete college if their par-

ents were in the highest relative to the lowest income quartile. More recently, this percentage has grown to 69.2 percent (Woolf et al., 2015).

Hahn and Truman (2015) report a strong association between educational attainment and both morbidity and mortality. In the United States, adults with lower educational attainment have higher rates of major circulatory diseases; diabetes; liver diseases; and such psychological symptoms as feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and worthlessness (although those with higher levels of educational attainment experience higher rates of prostate cancer and sinusitis). As for life expectancy, in 2017 a White man in the United States with less than a high school education could expect to live 73.5 years, while his counterpart with a graduate degree could expect to live more than 10 years longer. Likewise, a White woman could expect to live 8 years longer if she had a graduate degree than if she had less than a high school degree (Sasson and Howard, 2019).

Housing Instability and Homelessness

Research shows that people need stable housing to be healthy; people with limited resources and unstable housing are exposed to a number of health risks but often cannot move to better neighborhoods (Woolf et al., 2015). Homelessness also is closely linked to poor physical and mental health. Homeless people experience higher rates of such health problems as HIV, alcohol and drug abuse, mental illness, tuberculosis, and other conditions (Aldridge et al., 2018; Mosites et al., 2020). Providing stable housing coupled with such services as case management has been shown to improve mental health and health status in both children and parents (Bovell-Ammon et al., 2020).

Researchers have identified four pathways by which housing and health are connected (Taylor, 2018):

- The stability pathway: As noted above, not having stable housing has negative effects on health. Health problems among youth associated with residential instability include increased risk of teen pregnancy, early drug use, and depression (Taylor, 2018).

- The quality and safety pathway: A number of negative environmental factors within homes are correlated with poor health. In-home exposure to lead irreversibly damages the brains and nervous systems of children. Substandard housing conditions, such as water leaks, poor ventilation, poor air quality, dirty carpets, mold, and pest infestation, have been associated with poor health outcomes, most notably asthma (Taylor, 2018).

- The affordability pathway: A lack of affordable housing options can affect families’ ability to meet other essential expenses and create serious financial strain. Low-income families with difficulty paying rent or utilities are less likely to have a usual source of medical care and more likely to postpone needed treatment (Taylor, 2018).

- The neighborhood pathway: Researchers have found that the availability of resources, such as public transportation to one’s job, grocery stores with nutritious foods, and safe spaces to exercise, is correlated with better health outcomes (Taylor, 2018).

Food Insecurity

Food-insecure households are those that lack the resources to purchase adequate food to maintain their health. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that in 2018, 11.1 percent of U.S. households were food-insecure at some time during the year (USDA, 2020). Residents of low-resource neighborhoods often have limited access to sources of healthy food, such as supermarkets that sell fresh produce and other healthful food options. They are more likely to live in food deserts, characterized by an overconcentration of fast food outlets, corner stores, and liquor stores and a shortage of options for fresh fruits and vegetables and restaurants that offer healthy choices and menu labeling (Woolf et al., 2015).

Gundersen and Ziliak (2015) reviewed the literature on the effect of food insecurity on health in the United States. They found that the majority of research in this area has focused on children, revealing that food insecurity is associated with birth defects, anemia, lower nutrient intakes, cognitive problems, and aggression and anxiety, as well as higher hospitalization rates, poorer general health, asthma, behavioral problems, depression, suicidal ideation, and poor oral health. The authors also found that food insecurity is more common in households headed by an African American or Hispanic person and households with children (Gundersen and Ziliak, 2015). COVID-19 has exacerbated food insecurity; Feeding America estimates that almost 17 million individuals may have experienced food insecurity during the pandemic (Balch, 2020).

Environment and Climate Change

Environmental conditions affect the health of all individuals and communities. Environmental hazards, such as air pollution, harmful agricultural chemicals, and poor water quality, are more likely to exist in low-income communities and those populated by POC, and those communities tend to be more vulnerable to such hazards. Additionally, while natural disasters, such as floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, fires, winter storms, drought, and earthquakes, pose great threats to life and property and strain emergency and health care services wherever they strike, they affect underresourced populations more severely. These populations are more likely to live in geographic areas that are at high risk of natural disasters, such as flood plains, and to live in housing that is less resilient, such as mobile homes. Moreover, low-income residents have less capacity to move when such risks become evident (Boustan et al., 2017). In addition, the impacts of natural disasters depend not only on the magnitude of the event but also on the expo-

sure and vulnerability of the population, which vary with levels of wealth and education; disability and health status; and gender, age, class, and other social and cultural characteristics (IPCC, 2012). These inequities become even more pronounced if populations are displaced or forced to evacuate (Supekar, 2019). Natural disasters have long-term economic impacts on communities as well. Research shows that as damages from natural disasters increase, so, too, does wealth inequity in the long term, especially in relation to race, education, and homeownership (Howell and Elliott, 2018).

Researchers have increasingly found evidence that global climate change is increasing the magnitude and frequency of such severe events, including droughts, wildfires, and damaging storms (McNutt, 2019). Extreme weather (heat, drought), flooding, air and water pollution, allergens, vector- and waterborne diseases (Demain, 2018; IFRC, 2019), fire and its effects on air quality (Fann et al., 2018), and effects on the food supply related to nutrition and migration (NASEM, 2018)—all developments exacerbated by climate change—are already affecting human health around the globe. The changing climate will mean new challenges to health and disproportionate stress on some communities.

Rurality

Geography is associated with barriers to high-quality health care that can impact health outcomes. Rural Americans face numerous health inequities compared with their urban counterparts. More than 46 million Americans, or 15 percent of the U.S. population, live in rural areas (CDC, 2017). Compared with metropolitan areas, rural areas have higher death rates across the five leading causes of death nationally (heart disease, stroke, cancer, unintentional injury, and chronic lower respiratory disease). Among those aged <80 years in 2014, the numbers of potential excess deaths in rural areas for those five leading causes were 25,278 from heart disease, 19,055 from cancer, 12,165 from unintentional injury, 10,676 from chronic lower respiratory disease, and 4,108 from stroke. Death rates for unintentional injuries are 50 percent higher in rural than in metropolitan areas, attributable mainly to motor vehicle crashes and opioid overdoses (Garcia et al., 2017; Moy et al., 2017). Rural relative to urban residents have a higher percentage of several risk factors associated with poorer health. For example, obesity prevalence is significantly higher among rural than urban residents (34.2 percent versus 28.7 percent) (Lundeen et al., 2018).

Inequities within rural areas also exist, particularly at the intersection of geography and race and ethnicity. Based on County Health Rankings data for 2015, rural counties in which the majority of the population was non-Hispanic White had higher median household incomes, lower unemployment rates, fewer households with people younger than 18, and better access to healthy food compared with counties where other racial and ethnic groups made up the majority of the population. Not only did counties with majority Black and majority AI/AN residents have

significantly greater potential years of life lost before age 75 relative to counties with predominantly White residents, but also those differences were mediated by sociodemographic characteristics, including household income, unemployment rates, and the number of primary care physicians in the county (Henning-Smith et al., 2019).

Shortages of Health Care Providers

Shortages of health care providers significantly affect access to care in rural areas; as of December 2019, approximately 62.9 percent of primary care health professional shortage areas (HPSAs) were located in rural areas (RHI, 2020). According to the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, less than 11 percent of U.S. physicians practice in rural areas, while 20 percent of the U.S. population lives in these areas (Georgetown University, n.d.). Adding to this challenge is the closure of more than 160 rural hospitals since 2005 as the result of a number of factors, including decreasing profits, consolidation of the health care system, high rates of uninsured, and waning rural populations to support hospitals (Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, 2014a,b). The decline in rural acute care services highlights the increased need for primary care and individual and community-wide education in these areas to help prevent and manage chronic conditions and avoid related health crises that can lead to hospitalization and death (RHI, 2020).

Health Insurance Status

Uninsured rural residents face greater difficulty accessing care compared with their urban counterparts because of the limited supply of rural health care personnel who can provide low-cost or charity health care (Newkirk and Damico, 2014). According to a June 2016 issue brief from HHS, 43.4 percent of uninsured rural residents reported not having a usual source of care (Avery et al., 2016). The brief also states that 26.5 percent of uninsured rural residents had delayed receiving health care in the past year because of cost constraints. The affordability of health insurance is also a barrier for rural residents (Barker et al., 2018).

Transportation and Internet Access

Transportation poses a barrier to accessing appropriate care for all underresourced populations because of the travel time, cost, and time away from work involved. In rural areas, individuals are more likely to have to travel long distances for care, which can be burdensome given the higher rates of rural versus urban poverty. Longer distances can also result in longer wait times for emergency medical services and endanger individuals seeking prompt care for a potentially life-threatening emergency. Moreover, rural areas lack reliable transportation, whereas urban areas often have public transit available as an option for traveling to appointments.

Telehealth can help mitigate the challenges associated with transportation in rural areas; however, adequate broadband access is often limited in these areas. Almost 33 percent of rural individuals lack access to high-speed broadband Internet, defined by the Federal Communications Commission as download speeds of 25 Mbps or higher (FCC, 2015). Without access to broadband Internet, individuals seeking care cannot access video-based telehealth visits. In Michigan, for example, approximately 40 percent of rural residents lack access to high-speed broadband Internet versus just 3 percent of urban residents (FCC, n.d.). Thus, the shift to telehealth during COVID-19 may have exacerbated health disparities for millions of individuals living in rural areas.

THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC AND HEALTH INEQUITIES

The economic impacts of COVID-19 have been wide-reaching in the face of record high unemployment rates (BLS, 2020). The effects of the pandemic on both health and income have been especially severe for low-income individuals and POC. Internationally, rates of job loss have been high among low-income versus high-income people, further impacting their ability to access such essentials as healthy food (Daly et al., 2020; Lopez et al., 2020).

The disproportionate effects of COVID-19 on POC were discussed earlier in the chapter. Undocumented immigrants are another population in the United States that has been particularly vulnerable to the effects of the virus. An estimated 7.1 million undocumented immigrants lack health insurance, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act excludes undocumented immigrants from eligibility for coverage. As a result, many undocumented immigrants lack access to primary care and have relied on emergency departments for years (Page et al., 2020). Although immigrant communities tend to be relatively young and healthy, the prevalence of diabetes, a risk factor for COVID-19, is high (22 percent) among Hispanics (Page et al., 2020). The prevalence of diabetes is also high among AI/ANs—14.7 percent for adults (CDC, 2018). Additionally, as in the African American community, a high proportion of undocumented workers are employed in service industries, such as restaurants and hotels, or in the informal economy, which places them at increased risk of infection.

Another important consideration is the inequity inherent in school closures during the pandemic, which has affected children from underresourced families disproportionately. As with telehealth, access to distance learning is unequal for those who lack access to the Internet or the requisite technologies. Moreover, many underresourced communities rely on subsidized meal programs for adequate nutrition and on school nurses for vaccines and other health care services (Armitage and Nellums, 2020). Schools also may provide safeguarding and supervision, and school closures mean that parents considered essential workers may leave children unsupervised at home or forgo employment to stay at home with them (Armitage and Nellums, 2020). Low-income families have fewer

resources to expend on their children’s at-home education, meaning that during the pandemic, their children have fallen further behind relative to higher-income classmates who may have easier access to computers and the Internet while they are distance learning.

People in prisons, nursing homes, homeless shelters, and refugee camps constitute other vulnerable populations at higher risk during the pandemic. Many people in certain congregate settings have inadequate access to even basic health care, and many are older and have preexisting conditions, in addition to their close proximity to other people, that have placed them at high risk of infection (Berger et al., 2020). CDC assessed the prevalence of COVID-19 infections in homeless shelters in four U.S. cities during March 27–April 15, 2020, working with local partners to test residents and staff proactively, and found high levels of COVID-19 in both groups. Specifically, they found that 17 percent of residents and 17 percent of staff in Seattle, Washington; 36 percent of residents and 30 percent of staff in Boston, Massachusetts; and 66 percent of residents and 16 percent of staff in San Francisco, California, tested positive for the virus. Clearly, in many congregate care environments both residents and staff have been at high risk for contracting this disease; the latter, many of whom are low-income, are often deemed essential workers.

Emerging morbidity and mortality data further demonstrate that the effects of the pandemic have fallen disproportionately on vulnerable U.S. populations and exacerbate the deeply rooted social, racial, and economic disparities to which these populations are subject. Berger and colleagues (2020) note that underserved communities are distrustful of public health institutions, which have historically mistreated them, and suggest that it is unfair to ask them to act in the public interest by staying home at the expense of supporting themselves and their families. Governments, institutions, and health care facilities all have a role in enacting policies that are respectful and inclusive of vulnerable populations when the nation is faced with a public health emergency such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the present context, the global COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing health disparities and health care challenges and long-standing ethical issues that threaten the core values of the nursing profession (Laurencin and McClinton, 2020; see Chapter 3). The roles nurses are playing to address these challenges are described throughout the report. On a positive note, however, the crisis of COVID-19 has brought much-needed attention to these challenges and has accelerated the adoption of tools and approaches for responding to them. For example, while telehealth has long been touted as a way to address issues of access to care, it took COVID-19 for clinicians, payers, and individuals to fully embrace it as a viable—and sometimes even preferred—alternative to in-person care (Shah et al., 2020).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States was combatting the opioid overdose epidemic, which has led to devastating consequences that include opioid misuse, overdoses, and a rising number of newborns experiencing with-

drawal syndrome due to parental opioid use and misuse during pregnancy (NIH, 2021). Data for 2019 show that 70,630 people had died from drug overdose, 1.6 million had experienced an opioid use disorder, and 10.1 million had misused prescription opioids in the past year (HHS, 2021). The opioid epidemic is a public health crisis that impacts both social and economic welfare, and its convergence with the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated health disparities and created new health care challenges that need to be addressed.

CONCLUSION

People of lower socioeconomic status, rural populations, and communities of color experience a higher burden of poor health relative to those of higher socioeconomic status, urban populations, and Whites, and the health inequity gap has been growing over time. Such inequities are unnecessary, unjust, and avoidable. The roots of these inequities are shaped by structural determinants, and understanding and acting on those determinants will help nurses play a pivotal role in improving health equity. Improving social conditions upstream and midstream has been found to have positive impacts on health status, and improving those conditions will likely reduce health inequities and improve the health of the U.S. population as a whole. Changes upstream through changes in national policy and midstream at the individual level through integrated social care are needed to connect individuals to social services that include healthy food, affordable housing, and transportation. As an example, although many other developed nations spend less per capita than the United States on medical services, they spend more on social services related to medical care, and their residents lead healthier lives (NASEM, 2019a). Addressing SDOH requires a community-oriented approach that involves aligning health care resources and investments to facilitate collaborations with community and government sectors, and bringing health care assets into broader advocacy activities that augment and strengthen social care resources (NASEM, 2019a).

This report focuses on how the next generation of nurses can contribute to efforts to address SDOH and achieve health equity if provided with appropriate resources, including education, training, and financial support. Later chapters will describe the relatively new efforts of nurses to address SDOH that have been enabled, for example, by new technologies, changes in payment models, and integration of social care.

Conclusion 2-1: Structural racism, cultural racism, and discrimination exist across all sectors, such as housing, education, criminal justice, employment, and health care, impacting the daily lives and health of individuals and communities of color. Nurses have a responsibility to address all of those forms of racism and to advocate for policies and laws that promote equity and the delivery of high-quality care to all individuals.

REFERENCES

Acker, J., P. Braveman, E. Arkin, L. Leviton, J. Parsons, and G. Hobor. 2019. Mass incarceration threatens health equity in America. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Aldridge, R. W., A. Story, S. W. Hwang, M. Nordentoft, S. A. Luchenski, G. Hartwell, E. J. Tweed, D. Lewer, S. Vittal Katikireddi, and A. C. Hayward. 2018. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 391(10117):241–250.

Amin, K., G. Claxton, B. Sawyer, and C. Cox. 2019. How does cost affect access to care? Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/cost-affect-access-care/#item-start (accessed November 5, 2020).

ANA (American Nurses Association). 2020. ANA’s membership assembly adopts resolution on racial justice for communities of color. https://www.nursingworld.org/news/news-releases/2020/ana-calls-for-racial-justice-for-communities-of-color (accessed August 23, 2020).

ANA Ethics Advisory Board. 2019. The nurse’s role in addressing discrimination: Protecting and promoting inclusive strategies in practice settings, policy, and advocacy. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 24(3). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol24No03PoSCol01.

Armitage, R., and L. B. Nellums. 2020. Considering inequalities in the school closure response to COVID-19. Lancet Global Health 8(5):e644.

Artiga, S., K. Orgera, and A. Damico. 2020. Changes in health coverage by race and ethnicity since the ACA, 2010-2018. San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Assari, S. 2017. Social determinants of depression: The intersections of race, gender, and socioeconomic status. Brain Sciences 7(12).

Avery, K., K. Finegold, and X. Xiao. 2016. Impact of the Affordable Care Act coverage expansion on rural and urban populations. ASPE Issue Brief. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Balch, B. 2020. 54 million people in America face food insecurity during the pandemic. It could have dire consequences for their health. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/54-million-people-america-face-food-insecurity-during-pandemic-it-could-have-dire-consequences-their (accessed January 4, 2021).

Barker, A. R., L. Nienstedt, L. M. Kemper, T. D. McBride, and K. J. Mueller. 2018. Health insurance marketplaces: Issuer participation and premium trends in rural places, 2018. Rural Policy Brief 2018(3):1–4.

Barnett, M. L., D. Lee, and R. G. Frank. 2019. In rural areas, buprenorphine waiver adoption since 2017 driven by nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Health Affairs 38(12):2048–2056.

Berger, Z. D., N. G. Evans, A. L. Phelan, and R. D. Silverman. 2020. COVID-19: Control measures must be equitable and inclusive. BMJ 368:m1141.

Bernardo, C. de O., J. L. Bastos, D. A. González-Chica, M. A. Peres, and Y. C. Paradies. 2017. Interpersonal discrimination and markers of adiposity in longitudinal studies: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews 18(9):1040–1049. doi: 10.1111/obr.12564.

Bharmal, N., K. P. Derose, M. Felician, and M. M. Weden. 2015. Understanding the upstream social determinants of health. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

BLM (Black Lives Matter). n.d. Black Lives Matter: About. https://blacklivesmatter.com/about (accessed March 4, 2021).

BLS (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). 2020. Employment situation news release. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_01082021.htm (accessed December 14, 2020).

Boustan, L. P., M. E. Kahn, P. W. Rhode, and M. L. Yanguas. 2017. The effect of natural disasters on economic activity in U.S. counties: A century of data. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bovell-Ammon, A., C. Mansilla, A. Poblacion, L. Rateau, T. Heeren, J. T. Cook, T. Zhang, S. de Cuba, and M. T. Sandel. 2020. Housing intervention for medically complex families associated with improved family health: Pilot randomized trial. Health Affairs (Millwood) 39(4):613–621.

Bowleg, L. 2012. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health 102(7):1267–1273.

Braveman, P., J. Acker, E. Arkin, D. Proctor, A. Gillman, K. A. McGeary, and G. Mallya. 2018. Wealth matters for health equity. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Brinkley-Rubinstein, L., and D. H. Cloud. 2020. Mass incarceration as a social-structural driver of health inequities: A supplement to AJPH. American Journal of Public Health 110(51):S14–S16.

Caiola, C., J. Barroso, and S. L. Docherty. 2018. Black mothers living with HIV picture the social determinants of health. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 29(2):204–219.

Carson, E. A. 2020. Prisoners in 2018. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Castrucci, B., and J. Auerbach. 2019. Meeting individual social needs falls short of addressing social determinants of health. Health Affairs Blog. doi: 10.1377/hblog20190115.234942.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2017. Rural health: Death (leading causes). https://www.cdc.gov/ruralhealth/cause-of-death.html (accessed November 7, 2020).

CDC. 2018. Prevalence of diagnosed diabetes. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/diagnosed-diabetes.html (accessed March 15, 2021).

CDC. 2020a. COVID-19 hospitalization and death by race/ethnicity. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html (accessed August 27, 2020).

CDC. 2020b. CDC data show disproportionate COVID-19 impact in American Indian/Alaska Native populations. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0819-covid-19-impact-american-indian-alaska-native.html (accessed August 27, 2020).

Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. 2014a. Rural hospital closures: More information. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures-archive/rural-hospital-closures (accessed October 14, 2020).

Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. 2014b. 176 rural hospital closures: January 2005—present (134 since 2010). Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures (accessed October 23, 2020).

Chaturvedi, R., and R. A. Gabriel. 2020. Coronavirus disease health care delivery impact on African Americans. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 1–3. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.179

Chetty, R., and N. Hendren. 2018. The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility I: Childhood exposure effects. Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(3):1107–1162.

Chetty, R., N. Hendren, P. Kline, and E. Saez. 2014. Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(4):1553–1623.

Chetty, R., M. Stepner, S. Abraham, S. Lin, B. Scuderi, N. Turner, A. Bergeron, and D. Cutler. 2016. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. Journal of the American Medical Association 315(16):1750–1766.

Chou, S. C., Y. Deng, J. Smart, V. Parwani, S. L. Bernstein, and A. K. Venkatesh. 2018. Insurance status and access to urgent primary care follow-up after an emergency department visit in 2016. Annals of Emergency Medicine 71(4):487–496.

Cole, M. B., A. N. Trivedi, B. Wright, and K. Carey. 2018. Health insurance coverage and access to care for community health center patients: Evidence following the Affordable Care Act. Journal of General Internal Medicine 33(9):1444–1446.

Cruz, D., Y. Rodriguez, and C. Mastropaolo. 2019. Perceived microaggressions in health care: A measurement study. PLoS One 14(2):e0211620.

Cuellar, N. G., E. Aquino, M. A. Dawson, M. J. Garcia-Dia, E. O. Im, L. M. Jurado, Y. S. Lee, S. Littlejohn, L. Tom-Orme, and D. A. Toney. 2020. Culturally congruent health care of COVID-19 in minorities in the United States: A clinical practice paper from the National Coalition of Ethnic Minority Nurse Associations. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 31(5):434–443.

Daly, M. C., S. R. Buckman, and L. M. Seitelman. 2020. The unequal impact of COVID-19: Why education matters. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter 2020-17.

Demain, J. G. 2018. Climate change and the impact on respiratory and allergic disease: 2018. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports 18(4):22.

Dolezsar, C. M., J. J. McGrath, A. J. M. Herzig, and S. B. Miller. 2014. Perceived racial discrimination and hypertension: A comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychology 33(1):20–34.

Escarce, J. 2019. Health inequity in the United States: A primer. Philadelphia, PA: Penn Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics.

Fann, N., B. Alman, R. A. Broome, G. G. Morgan, F. H. Johnston, G. Pouliot, and A. G. Rappold. 2018. The health impacts and economic value of wildland fire episodes in the U.S.: 2008–2012. Science of the Total Environment 610–611:802–809.

FCC (Federal Communications Commission). 2015. Data: Broadband. https://www.fcc.gov/reports-research/maps/connect2health/data.html (accessed September 2, 2020).

FCC. n.d. Mapping broadband health in America. https://www.fcc.gov/health/maps (accessed September 2, 2020).

Fernandez-Lazaro, C. I., D. P. Adams, D. Fernandez-Lazaro, J. M. Garcia-González, A. Caballero-Garcia, and J. A. Miron-Canelo. 2019. Medication adherence and barriers among low-income, uninsured patients with multiple chronic conditions. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 15(6):744–753.

FitzGerald, C., and S. Hurst. 2017. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics 18(1):19.

Foster, K., M. Roche, C. Delgado, C. Cuzzillo, J. A. Giandinoto, and T. Furness. 2019. Resilience and mental health nursing: An integrative review of international literature. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 28(1):71–85.

Garcia, M. C., M. Faul, G. Massetti, C. C. Thomas, Y. Hong, U. E. Bauer, and M. F. Iademarco. 2017. Reducing potentially excess deaths from the five leading causes of death in the rural United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 66(2):1–7.

Garcia, M. A., P. A. Homan, C. García, and T. H. Brown. 2020. The color of COVID-19: Structural racism and the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on older racial and ethnic minorities. Journals of Gerontology, Series B 76(3):e75–e80.

Georgetown University Health Policy Institute. n.d. Rural and urban health. https://hpi.georgetown.edu/rural (accessed September 2, 2020).

Gordon, K., C. Steele Gray, K. N. Dainty, J. DeLacy, P. Ware, and E. Seto. 2020. Exploring an innovative care model and telemonitoring for the management of patients with complex chronic needs: Qualitative description study. Journal of Medical Internet Research Nursing 3(1):e15691.

Gundersen, C., and J. P. Ziliak. 2015. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Affairs 34(11):1830–1839.

Hahn, R. A., and B. I. Truman. 2015. Education improves public health and promotes health equity. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation 45(4):657–678.

Hajat, A., J. S. Kaufman, K. M. Rose, A. Siddiqi, and J. C. Thomas. 2010. Do the wealthy have a health advantage? Cardiovascular disease risk factors and wealth. Social Science & Medicine 71(11):1935–1942.

Hall, W. J., M. V. Chapman, K. M. Lee, Y. M. Merino, T. W. Thomas, B. K. Payne, E. Eng, S. H. Day, and T. Coyne-Beasley. 2015. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health 105(12):e60–e76.

Henning-Smith, C., S. Prasad, M. Casey, K. Kozhimannil, and I. Moscovice. 2019. Rural-urban differences in Medicare quality scores persist after adjusting for sociodemographic and environmental characteristics. Journal of Rural Health 35(1):58–67.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2018. Crude percent distributions (with standard errors) of type of health insurance coverage for persons under age 65 and for persons aged

65 and over, by selected characteristics: United States, 2018. Table P-11c. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/NHIS/SHS/2018_SHS_Table_P-11.pdf (accessed March 15, 2021).

HHS. 2019. Diabetes and African Americans. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=18 (accessed October 20, 2020).

HHS. 2020. Heart disease and African Americans. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=19 (accessed October 20, 2020).

HHS. 2021. What is the U.S. opioid epidemic? https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/index.html (accessed March 6, 2021).

Howell, J., and J. R. Elliott. 2018. Damages done: The longitudinal impacts of natural hazards on wealth inequality in the United States. Social Problems 66(3):448–467.

Hudson, D. L., K. M. Bullard, H. W. Neighbors, A. T. Geronimus, J. Yang, and J. S. Jackson. 2012. Are benefits conferred with greater socioeconomic position undermined by racial discrimination among African American men? Journal of Men’s Health 9(2):127–136.

IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2019. Heatwaves: Urgent action needed to tackle climate change’s “silent killer.” https://media.ifrc.org/ifrc/pressrelease/heatwaves-urgent-action-needed-tackle-climate-changes-silent-killer (accessed March 15, 2021).

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2012. Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: A special report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Jividen, S. 2020. Nurses are going to protests, after work, to help injured people. Nurse.org. https://nurse.org/articles/nurses-at-protests (accessed November 6, 2020).

Kantamneni, N. 2020. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on marginalized populations in the United States: A research agenda. Journal of Vocational Behavior 119:103439. doi: 10.1016/j. jvb.2020.103439.

Killewald, A., F. T. Pfeffer, and J. N. Schachner. 2017. Wealth inequality and accumulation. Annual Review of Sociology 43:379–404.

Kim, J., and V. Richardson. 2012. The impact of socioeconomic inequalities and lack of health insurance on physical functioning among middle-aged and older adults in the United States. Health & Social Care in the Community 20(1):42–51.

Kinner, S. A., and J. T. Young. 2018. Understanding and improving the health of people who experience incarceration: An overview and synthesis. Epidemiologic Reviews 40(1):4–11.

Landrine, H., I. Corral, J. G. Lee, J. T. Efird, M. B. Hall, and J. J. Bess. 2017. Residential segregation and racial cancer disparities: A systematic review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 4(6):1195–1205.

Laurencin, C. T., and A. McClinton. 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic: A call to action to identify and address racial and ethnic disparities. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 7(3):398–402.

Laws, M. B., Y. Lee, W. H. Rogers, M. C. Beach, S. Saha, P. T. Korthuis, V. Sharp, J. Cohn, R. Moore, and I. B. Wilson. 2014. Provider-patient communication about adherence to anti-retroviral regimens differs by patient race and ethnicity. AIDS and Behavior 18(7):1279–1287.

Levine, D. M., B. E. Landon, and J. A. Linder. 2019. Quality and experience of outpatient care in the United States for adults with or without primary care. JAMA Internal Medicine 179(3):363–372.

Lewis, T. T., D. R. Williams, M. Tamene, and C. R. Clark. 2014. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and cardiovascular disease. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports 8(1):1–15.

Lopez, M. H., L. Rainie, and A. Budiman. 2020 (May 5). Financial and health impacts of COVID-19 vary widely by race and ethnicity. Pew Research Center Factank. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/05/financial-and-health-impacts-of-covid-19-vary-widely-by-race-andethnicity (accessed September 2, 2020).

Lukachko, A., M. L. Hatzenbuehler, and K. M. Keyes. 2014. Structural racism and myocardial infarction in the United States. Social Science and Medicine 103:42–50.

Lundeen, E. A., S. Park, L. Pan, T. O’Toole, K. Matthews, and H. M. Blanck. 2018. Obesity prevalence among adults living in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties—United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67(23):653.

Macinko, J., B. Starfield, and L. Shi. 2007. Quantifying the health benefits of primary care physician supply in the United States. International Journal of Health Services 37(1):111–126.

Martsolf, G. R., D. J. Mason, J. Soan, and V. Sullivan. 2017. Nurse-designed care models: What can they tell us about advancing a culture of health? Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Massoglia, M., and Remster, B. (2019). Linkages between incarceration and health. Public Health Reports 134(1 Suppl):8S–14S.

McNutt, M. 2019. Time’s up, CO2. Science 365(6452):411.

Mehra, R., L. M. Boyd, and J. R. Ickovics. 2017. Racial residential segregation and adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine 191:237–250.

Mesic, A., L. Franklin, A. Cansever, F. Potter, A. Sharma, A. Knopov, and M. Siegel. 2018. The relationship between structural racism and Black-White disparities in fatal police shootings at the state level. Journal of the National Medical Association 110(2):106–116.

Mosites, E., E. M. Parker, K. E. N. Clarke, J. M. Gaeta, T. P. Baggett, E. Imbert, M. Sankaran, A. Scarborough, K. Huster, M. Hanson, E. Gonzales, J. Rauch, L. Page, T. M. McMichael, R. Keating, G. E. Marx, T. Andrews, K. Schmit, S. B. Morris, N. F. Dowling, G. Peacock, and COVID Homelessness Team. 2020. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 infection prevalence in homeless shelters—Four U.S. Cities, March 27–April 15, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69(17):521–522.

Moy, E., M. C. Garcia, B. Bastian, L. M. Rossen, D. D. Ingram, M. Faul, G. M. Massetti, C. C. Thomas, Y. Hong, P. W. Yoon, and M. F. Iademarco. 2017. Leading causes of death in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan areas—United States, 1999–2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 66(1):1–8.

Nadal, K. L., K. E. Griffin, Y. Wong, K. C. Davidoff, and L. S. Davis. 2017. The injurious relationship between racial microaggressions and physical health: Implications for social work. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work 26(1–2):6–17.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. Communities in action: Pathways to health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2018. Health-care utilization as a proxy in disability determination. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2019a. Integrating social care into the delivery of health care: Moving upstream to improve the nation’s health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2019b. Vibrant and healthy kids: Aligning science, practice, and policy to advance health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2020. Birth settings in America: Outcomes, quality, access, and choice. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Nau, C., J. L. Adams, D. Roblin, J. Schmittdiel, E. Schroeder, and J. F. Steiner. 2019. Considerations for identifying social needs in health care systems: A commentary on the role of predictive models in supporting a comprehensive social needs strategy. Medical Care 57(9):661–666.

NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics). 2017. Health, United States. In Health, United States, 2016: With chartbook on long-term trends in health. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

NEJM (New England Journal of Medicine) Catalyst. 2017. Social determinants of health. https://catalyst.nejm.org/social-determinants-of-health (accessed November 5, 2019).

Newkirk, V., and A. Damico. 2014. The Affordable Care Act and insurance coverage in rural areas. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/the-affordable-care-act-and-insurance-coverage-in-rural-areas (accessed September 2, 2020).

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2021. Opioid overdose crisis. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugtopics/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis (accessed March 6, 2021).

NNU (National Nurses United). 2020. National Nurses United’s statement on protests and systemic racism: “Stop blaming underlying health conditions and comorbidities.” https://www.nationalnursesunited.org/press/national-nurses-uniteds-statement-protests-and-systemic-racism (accessed November 6, 2020).

Odgers, C. L., and N. E. Adler. 2018. Challenges for low-income children in an era of increasing income inequality. Child Development Perspectives 12(2):128–133.

ODPHP (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion). 2020a. Social Determinants of Health. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health (accessed November 9, 2020).

ODPHP. 2020b. Access to health services. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/Access-to-Health-Services (accessed November 9, 2020).

Ong, A. D., C. Cerrada, D. R. Williams, and R. A. Lee. 2017. Stigma consciousness, racial microaggressions, and sleep disturbance among Asian Americans. Asian American Journal of Psychology 8(1):72–81.

Owens, A., and J. Candipan. 2019. Social and spatial inequalities of educational opportunity: A portrait of schools serving high- and low-income neighbourhoods in U.S. metropolitan areas. Urban Studies 56(15):3178–3197.

Page, K. R., M. Venkataramani, C. Beyrer, and S. Polk. 2020. Undocumented U.S. immigrants and COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine 382(21):e62.

Paradies, Y., J. Ben, N. Denson, A. Elias, N. Priest, A. Pieterse, A. Gupta, M. Kelaher, and G. Gee. 2015. Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 10(9):e0138511.

RHI (Rural Health Information Hub). 2020. Healthcare access in rural communities. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/healthcare-access#faqs (accessed April 22, 2021).

Sasson, I., and M. D. Hayward. 2019. Association between educational attainment and causes of death among White and Black U.S. adults, 2010-2017. Journal of the American Medical Association 322(8):756–763.

Seo, V., T. P. Baggett, A. N. Thorndike, P. Hull, J. Hsu, J. P. Newhouse, and V. Fung. 2019. Access to care among Medicaid and uninsured patients in community health centers after the Affordable Care Act. BMC Health Services Research 19(1):291.

Shah, E. D., S. T. Amann, and J. J. Karlitz. 2020. The time is now: A guide to sustainable telemedi-cine during COVID-19 and beyond. American Journal of Gastroenterology 115(9):1371–1375.

Shi, L. 2012. The impact of primary care: A focused review. Scientifica 2012:432892.

Slopen, N., T. T. Lewis, and D. R. Williams. 2016. Discrimination and sleep: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine 18:88–95.

Solar, O., and A. Irwin. 2010. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health: Social determinants of health discussion paper 2. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Sue, D. W., C. M. Capodilupo, G. C. Torino, J. M. Bucceri, A. M. Holder, K. L. Nadal, and M. Esquilin. 2007. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist 62(4):271–286.

Supekar, S. 2019. Equitable resettlement for climate change-displaced communities in the United States. UCLA Law Review 66:1290.

Taylor, L. A. 2018. Housing and health: An overview of the literature. Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. doi: 10.1377/HPB20180313.396577.

USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture). 2020. Food security and nutrition assistance. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/food-security-and-nutrition-assistance (accessed September 2, 2020).

van Dorn, A., R. E. Cooney, and M. L. Sabin. 2020. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the U.S. Lancet 395(10232):1243–1244.

van Ryn, M., and J. Burke. 2000. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Social Science & Medicine 50(6):813–828.

Wallis, C. 2020 (June 12). Why racism, not race, is a risk factor for dying of COVID-19. Scientific American: Public Health. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-racism-not-race-is-a-risk-factor-for-dying-of-COVID-191 (accessed November 6, 2020).

Weissman, J., L. A. Pratt, E. A. Miller, and J. D. Parker. 2015. Serious psychological distress among adults: United States, 2009–2013. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Williams, D. R., J. A. Lawrence, and B. A. Davis. 2019. Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annual Review of Public Health 40:105–125.

Woolf, S. H., L. Aron, L. Dubay, S. M. Simon, E. Zimmerman, and K. X. Luk. 2015. How are income and wealth linked to health and longevity? Urban Institute and Virginia Commonwealth University Center on Society and Health.

Yancy, C. W. 2020. COVID-19 and African Americans. Journal of the American Medical Association 323(19):1891–1892.

Zagorsky, J. L., and P. K. Smith. 2016. Does asthma impair wealth accumulation or does wealth protect against asthma? Social Science Quarterly 97(5):1070–1081.