5

Integrated Primary Care Delivery

Integrated primary care delivery is a foundational strategy for health care organizations to support a culture of high-quality, person- and family-centered primary care built on trusted, accessible, and continuous relationships (see Chapter 2 for the committee’s definition of high-quality primary care). This chapter outlines the implementation facilitators needed to support the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of integrated delivery structures and processes of health care organizations that enable improved health outcomes and promote population health and health equity.

Integrated care has been defined as care that is coordinated across professionals, facilities, and support systems; continuous over time and between visits; and tailored to personal and family needs, values, and preferences (Singer et al., 2011). It encompasses a diverse set of methods and models that aim to facilitate improved patient experiences through enhanced coordination and continuity of care (Rocks et al., 2020). When applied to primary care, a functional definition of integrated care is care that results when a primary care team and another team or organization or service external to primary care work together with patients and families “using a systematic and cost-effective approach” to provide person- and family-centered care for a defined population (AHRQ, 2013, p. 2). Examples include integrating primary care with behavioral health, pharmacy, and oral health services and with public health and services to address social determinants of health (SDOH) (NASEM, 2019a). The professionals and staff for these joint services are integrated directly into primary care practices through an interprofessional team-based approach to care.

THE GOALS OF INTEGRATED CARE DELIVERY

The main reasons to integrate interprofessional team-based methods into primary care are to expand the impact of primary care, grow its capacity to comprehensively address a broader range of whole-person health needs, and establish effective, shared linkages with families, community organizations, and specialist resources over time (Bitton et al., 2018). The rationale for this integration is that primary care is where most people seek any health care and where they are most likely to develop sustained, healing relationships focused on well-being that can contribute to overall population health (Buckley et al., 2013; Colwill et al., 2016; Ellner and Phillips, 2017; Flieger, 2017; Frey, 2010; Gottlieb, 2013; Green and Puffer, 2016; Kravitz and Feldman, 2017). It is also the venue that delivers most mental health care, and visits to primary care often involve issues related to other family members or social needs (Gard et al., 2020; Pinto and Bloch, 2017; Pinto et al., 2016; Xierali et al., 2013). Implementing integrated, team-based care with high fidelity has been shown to improve health care quality and cost outcomes (IOM, 2011; Reiss-Brennan et al., 2016; Yogman et al., 2018) and may help achieve health equity by including social and health services that meet all communities’ needs (Browne et al., 2012; Satcher and Rachel, 2017). Integrated team-based primary care can also help alleviate clinician burnout (NASEM, 2019b).

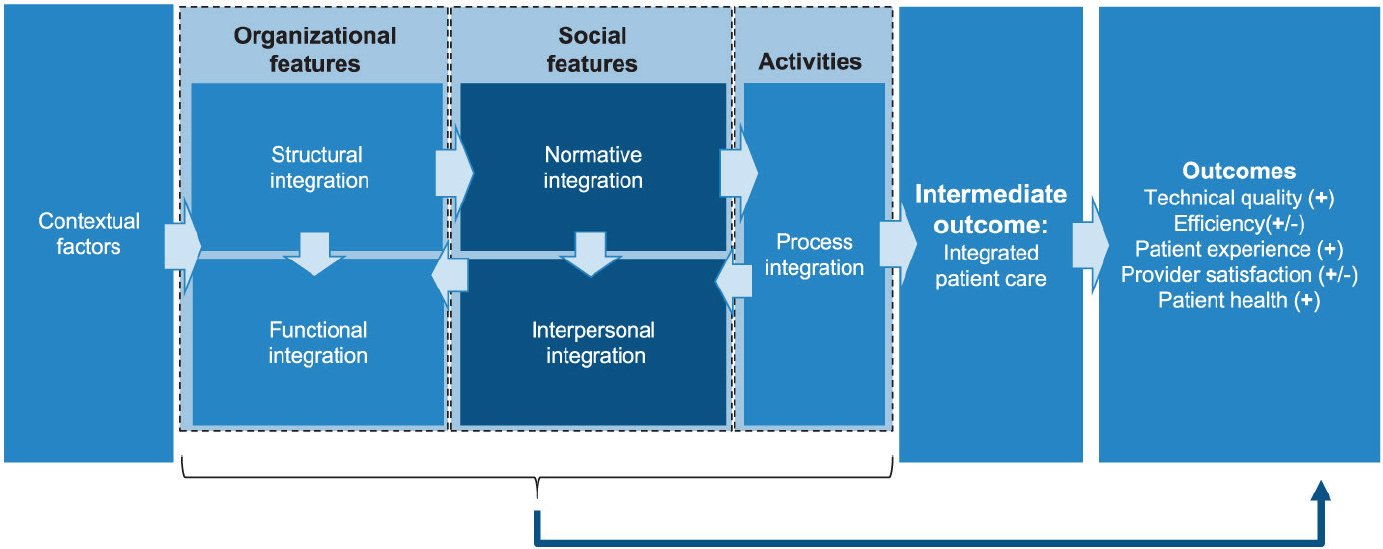

To guide its work reviewing innovative integration solutions and developing an implementation plan to achieve integration, the committee adopted the Comprehensive Theory of Integration (Singer et al., 2020) as a guiding principle. This theory defines and distinguishes several aspects of integration (see Figure 5-1):

- Structural integration: physical, operational, financial, or legal ties

- Functional integration: formal, written policies and protocols for activities that coordinate and support accountability and decision making

- Normative integration: a common culture and a specific culture of integration

- Interpersonal integration: collaboration or teamwork

- Process (or clinical) integration: organizational actions or activities intended to integrate care services into a single process across people, functions, activities, and operating units over time

The committee focuses its recommendations on implementing the structures and processes that support normative, interpersonal, process, and clinical integration to advance whole-person integrated care. Elements of structural and functional integration are the focus of policy makers and

SOURCE: Singer et al., 2020.

industry leaders (Singer et al., 2020; Valentijn et al., 2015) and covered in subsequent chapters.

Achieving normative, cultural, and process integration for primary care delivery requires health care organizations to design and implement a number of key components and capabilities (see Table 5-1). Several evidence-based structures and processes (“coordinating mechanisms”) facilitate integrated primary care delivery (Weaver et al., 2018) (see Table 5-2).

The structures and processes of integrated primary care systems must be nimble enough to allow people to seek care, either in person or virtually, while still providing high-quality, whole-person care for individuals and families. Furthermore, institutional leaders must design and plan for coordinating the needs of integrated primary care with the needs of its communities by thoughtful monitoring. For example, a pediatric-focused integrated primary care system might invest more heavily in community partnerships with Head Start Centers, other preschools, and the local public schools, while a system that serves a largely older, Black adult population may invest more heavily in developing community partnerships with churches and coordinating with long-term care facilities. Effective integrated primary care needs to be tailored not only at the level of the individual and family but also for the population that it serves (see Chapter 4 for more on community partnerships).

Southcentral Foundation

Despite few fully integrated, community-specific primary care systems in the United States, some examples do exist that show their potential for assuring integrated, person-centered primary care. One such example, the Southcentral Foundation (SCF), provides comprehensive, integrated health care for nearly 65,000 Alaska Native and American Indian people in and near Anchorage, Alaska. SCF’s Nuka System of Care was designed to align with its vision of “a Native Community that enjoys physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual wellness” (Gottlieb, 2013) (see Chapter 4 for more on SCF’s emphasis on relationship-based care). SCF uses a team-based approach to care that is inclusive of team members outside of the traditional clinician, including experts in complementary or integrative medical care and traditional healing practices who provide support throughout the care system and via dedicated clinics in Anchorage (SCF, 2020).

The Nuka integrated primary care team supports structural, normative, and process integration; its core includes a primary care clinician, certified medical assistant, registered nurse case manager, and case management support. An integrated team with clinical behavioral health consultants, pharmacists, registered dietitians, midwives, and advanced practice clinicians supports the core team, with additional expertise, such as integrative

TABLE 5-1 Components of Integrated Primary Care Delivery and Key Capabilities

| Key Components of Integrated Care | How the Integrated Care Component Works | Key Capabilities |

|---|---|---|

| Interprofessional team-based care (normative integration) | A practice team tailored to the whole-person primary care needs of each person/family (A key element of this practice team is the family navigator, health coach, care coordinator, community health worker, or other team member with the responsibility of providing culturally relevant support, coordination, and service to the person and family.) |

|

| Population-based care (process and functional integration) | With a shared population and mission, and a panel of patients in common for total health outcomes |

|

| Care management (structural, process, and interpersonal integratio | Using a systematic clinical approach and a system that ) enables the clinical approach to function |

|

Supported by seven facilitators of high-quality primary care

|

Practice operations, leadership alignment, community partnerships, and business model address all six facilitators |

|

| Key Components of Integrated Care | How the Integrated Care Component Works | Key Capabilities |

|---|---|---|

| Supported by implementation framework | Continuous quality improvement and measurement of effectiveness and adoption over time |

|

SOURCES: Adapted from AHRQ, 2013; Talen and Valeras, 2013; Yonek et al., 2020.

medicine, brought in when needed. All interprofessional team members and support staff, regardless of position, are on board with cultural and organizational training to instill the Nuka philosophy and the basics of quality improvement methods (Gottlieb et al., 2008). The end result is that the primary care team integrates over multiple levels with the wide range of expertise and resources needed to provide whole-person primary care that includes prevention, chronic disease management, acute care, behavioral health, oral care, vision care, and culturally relevant traditional healing.

Intermountain Healthcare

Intermountain Healthcare is a fully integrated delivery system that has consistently produced high-quality outcomes and lower cost through its normative culture of clinical and operational team integration (Reiss-Brennan et al., 2016). Based in Idaho, Nevada, and Utah, Intermountain delivers more than half of all health care in the region through an organized network of 180 primary care clinics, 24 hospitals, and a health insurance plan. Its medical group employs and supports diverse teams of clinicians, but the majority of care is provided by independent, community-based practices. These practices are connected through standard quality metrics and clinical work processes and paid through fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement. Intermountain has sustained a clinical evidence-based culture designed to help people live the healthiest lives possible and demonstrated improvements in clinical quality and lower costs (James and Savitz, 2011). This integration is built on a common shared culture of high-quality, collaborative teams organized around professional values that focus on individuals’ needs, using continuously improved workflows, and robust outcome and process data that drive a single care process model that integrates people, functions, and operations. Intermountain’s integration efforts, including the innovative transformation of traditional primary care to an integrated team-based care

TABLE 5-2 Coordinating Mechanisms That Can Support Integrated Primary Care Delivery Through Improved Normative, Interpersonal, and Process Integration

| Coordinating Mechanism | Example |

|---|---|

| Designated role to coordinate care across settings (can be inside or outside of clinic) Plans and rules |

|

| Routines |

|

| Proximity (virtual and real) |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Weaver et al., 2018.

process model for identifying and managing chronic physical and mental health conditions, have produced clinical and cost improvements. Its robust data integration and analytic processes captured the evidence needed for leadership to determine that the $22.19 maximum per-person per-year cost of implementing integrated team-based care in primary care was lower than the overall savings to the whole system ($115.09 per person, per year) and that scaling the innovation held promise for a long-term return on investment for both people seeking care and clinicians (Reiss-Brennan et al., 2016).

Both the SCF Nuka and Intermountain integrated delivery systems have strong structural and functional integration foundations that support their clinical and operational leadership, governance accountability, and investment in promoting cultures of whole-person integrated care while managing overall health care costs continuously over time.

The Blueprint for Health

Launched by the Department of Vermont Health Access in 2003, the Vermont Blueprint for Health (Blueprint) is another example of an integrated primary care system that aims to improve structural, normative, and process integration. The Blueprint is a statewide, whole-population

health initiative that supports delivery system reforms in majority rural and “micropolitan” locations (Jones et al., 2016). In addition to supporting primary care practice transformation for patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), the Blueprint includes important inter-organizational relationships to improve structural integration:

- Community collaboratives that provide leadership by identifying local priorities and allocating resources;

- Community health teams (CHTs) that provide care coordination across health and social services in conjunction with two partner programs: the Vermont Chronic Care Initiative and Support and Services at Home, which integrates subsidized housing for Medicare beneficiaries (RTI International et al., 2017);

- Hub and Spoke, a program for opioid use disorder treatment that partners more than 85 primary care and specialty practices with trainings and resources from the Vermont Department of Health’s Division of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Programs, including two CHT team members licensed in mental health or substance abuse; and

- The Women’s Health Initiative, designed to improve access to family planning and contraception and support healthy families in both PCMH and obstetrics/gynecology settings, launched in 2017 (AHS, 2019).

The Blueprint also supports process and normative integration by providing education and training programs in the form of a self-management program for community members. It created the Integrated Communities Care Management Learning Collaborative for improving cross-organization care coordination and care management (State of Vermont, 2020).

In 2011, Medicare joined as a payer, and until 2016, Blueprint participated in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Multi-Payer Advanced Primary Care Practice Demonstration (RTI International et al., 2017). In the first 2 years, the Blueprint used demonstration funds to hire additional staff for practices and CHTs, including behavioral health specialists, case managers, wellness nurses, social workers, dieticians, pharmacists, and health coaches. During the demonstration, the Blueprint realized $64 million in Medicare net savings relative to comparison PCMH practices, largely attributed to reductions in inpatient and outpatient expenditures; however, it also incurred $40 million in additional Medicaid spending (RTI International et al., 2017), likely the result of the initial increased access and thus increased health care use for a population that previously had high levels of unmet need. Nonetheless, overall medical expenditures decreased by around $5.8 million for every $1 million spent on the Blueprint (Jones et al., 2016). CHTs and Support and Services at Home teams contributed to

improved integration by facilitating care continuity and specialist visits and offering services related to population health and chronic disease management that practices were unable to provide on their own (RTI International et al., 2017). These teams improved normative and process integration and helped reduce hospital readmission rates.

Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes)

An important example of remote integration, Project ECHO connects governments, academic medical centers, nongovernmental organizations, and centers of excellence around the world to “telementor” clinicians for the purpose of training, enabling collaborative problem solving and co-management of cases, and ultimately improving quality of care in underserved communities (UNM, 2021b). Originally designed by the University of New Mexico for the treatment of hepatitis C, today it operates in 45 countries (UNM, 2021a) and has been used to disseminate clinical training on cancer screening, addiction management, perinatal care, COVID-19 treatment, and many other primary care domains (Archbald-Pannone et al., 2020; Coulson and Galvin, 2020; Francis et al., 2020; Komaromy et al., 2016; Nethan et al., 2020).

With its hub-and-spoke model, Project ECHO enables regular, bidirectional knowledge sharing and collaboration between geographically isolated care team members, fostering new local partnerships, or facilitating the development of new services where they were previously unavailable or insufficient. Project ECHO has been successful, with outcomes including increased knowledge and self-efficacy among clinicians, decreased feelings of professional isolation, increased safety and improved treatment outcomes for patients, and greater ability to enact practice transformation projects (Arora et al., 2008; McDonnell et al., 2020).

The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly

The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) is a voluntary, community-based medical and social services program available to individuals eligible for nursing home care and living within PACE service areas (CMS, 2021a). PACE is designed to provide whole-person and continuous care to older adults with chronic care needs with the goal of maintaining independent living in their homes for as long as possible. Seen as an effective model of integrated delivery, the program provides all Medicare and Medicaid covered services, including primary care services and health plan management, dentistry, prescription drugs and medication management, nursing care, rehabilitation services, personal and in-home care, specialty services, nutritional counseling, social work counseling, transportation services, and

recreation services (CMS, 2021b). Aside from the specialty services, which are provided by referral, the rest of these services operate under the same umbrella. All members of the team—from drivers to those providing recreational services—are trained to observe participants and report their observations to clinical staff. Most participants are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, and PACE financing comes from both programs in prospective capitated payments.

PACE has demonstrated success for participants in reduced hospital use, an increased number of days in the community, fewer unmet needs, and better health overall (Boult and Wieland, 2010; Gonzalez, 2017; Hirth et al., 2009; Meret-Hanke, 2011). However, a 2014 review noted that it is challenging to conduct a rigorous, comparative evaluation of the program and that much of the published research of PACE is weak (Ghosh et al., 2014). The review found PACE offered no cost savings for Medicare and was more costly for Medicaid than other forms of care. Cost studies overall, however, have been somewhat mixed (e.g., a 2014 study found that PACE Medicaid capitation payments demonstrated savings compared to projected FFS estimates for equivalent long-term care) (Wieland et al., 2013). There are currently 138 PACE programs across 31 states (NPA, 2021).

Although the demonstrated outcomes of the aforementioned whole-person, community-specific integrated care delivery models are limited to those systems, considerable evidence exists for more targeted innovations of integration that specifically address the broader national primary care burden of those with mental health and social needs. The sections that follow provide evidence-based practices for integrating behavioral health and social needs in primary care and promising trends for best practice integration for oral and public health. This integration of services allows primary care to shift to a focus on whole-person care, equitable across settings, and supports sustained team relationships that take into account a more complete view of health and well-being in the context of community experiences.

Behavioral Health Integration

The evidence for primary care integration is strongest for a behavioral health–primary care model (Asarnow et al., 2015b; Coventry et al., 2015; McGinty and Daumit, 2020; Miller et al., 2014). Mental health is a growing, costly global priority that has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Holingue et al., 2020). Primary care has historically been the de facto mental health system for many individuals in the United States (Mitchell et al., 2009). Behavioral health concerns are often identified and managed within primary care, and integrating mental and physical health through innovative screening, diagnosis, and team management in primary

care increases the likelihood that whole-person care—including behavioral health needs—can be addressed equitably, efficiently, and effectively (Anderson et al., 2015; Foy et al., 2019; Hodgkinson et al., 2017; Miller and Druss, 2013; Miller et al., 2014; Reiss-Brennan, 2014; Reiss-Brennan et al., 2016; Wissow et al., 2016; Xierali et al., 2013). Individuals and families prefer to address their emotional and physical concerns through trusted primary care relationships (NAMI, 2011; Parker et al., 2020) and to be treated as a whole person, not just a disease (Croghan and Brown, 2010; NAMI, 2011). The continuum of the degree of behavioral health–primary care integration between clinicians affects processes of care (Ramanuj et al., 2019). Structural integration ranges from simple coordination and colocation, where the clinicians may be physically nearby without integration within the care process, to collaborative care (Asarnow et al., 2015a). In collaborative care, primary care and behavioral health professionals work together, often with a care manager or coordinator, to care for a shared population such that patients experience a single organized system that treats the whole person (Gerrity, 2016).

Integrated models of primary care and behavioral health can improve normative and process integration; studies have shown that mental and behavioral health team integration produces better health outcomes and lower costs for adults (Archer et al., 2012; Gilbody et al., 2006; Huffman et al., 2014; Katon and Guico-Pabia, 2011; Katon et al., 2010; Reiss-Brennan et al., 2016; Unützer et al., 2013) and improved outcomes for children and adolescents (Asarnow et al., 2015b; Platt et al., 2018).

When served at primary care clinics at which mental health is a routine part of the medical visit, compared to traditional primary care, patients had improved quality of care, lower rates of emergency department (ED) visits, fewer hospital admissions, and lower overall costs for chronic medical conditions (Reiss-Brennan et al., 2016). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of integrated primary care–behavioral health models for children and adolescents demonstrated better outcomes for the integrated care model compared with usual care. The strongest effects were seen for collaborative care models in which primary care clinicians, care managers, and mental health specialists work in a team-based approach to care (Asarnow et al., 2015b). Research has also demonstrated that integrated team-based care is highly effective for patients from ethnic minority groups and reduces health disparities for those populations (Areán et al., 2005; Ell et al., 2009, 2010; Holden et al., 2014; Miranda et al., 2003).

Pediatric populations have fewer complex, high-cost cases with complex medical and behavioral health needs compared to adult populations, making the short-term return on investment (ROI) of integration more elusive. However, the ability to affect adult trajectories of health by transforming primary care to address the social, developmental, and behavioral

levers of health more comprehensively during childhood and adolescence can have a much larger effects on ROI over the long term, which would be true for not only health care but also other sectors, such as education, justice, and the workforce.

When compared with FFS Medicaid, a pediatric accountable care organization (ACO) with primary care and behavioral health integration, a population health focus, and an emphasis on care coordination demonstrated a lower rate of cost growth without reducing quality measures or outcomes of care (Kelleher et al., 2015). Integrated care for children and adolescents likely requires a set of supports unique from that for adult care, particularly during expansion. For example, child mental health concerns are inextricably linked to parental mental health and family psychosocial needs, making it imperative to include mechanisms to address and treat parents’ and family mental health needs, social needs, and parent–child interaction (Wissow et al., 2020). Furthermore, child mental health is more likely to require more-intensive behavioral treatments and greater investment in team members who can provide these more time-intensive, family-inclusive interventions (Shonkoff and Fisher, 2013), rather than isolated medication management, as may be more typical of adult behavioral health integrated care.

Integrating behavioral health and primary care has been shown to have value for the care of older adults as well. For example, the Improving Mood: Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment model of depression care for older adults in primary care settings has been associated with better health outcomes, better quality of life, and equal or lower health care costs (Fann et al., 2009; Grympa et al., 2006; Katon et al., 2006; Unützer et al., 2002, 2008). Older adults may be more willing to accept screenings or treatment within a primary care practice rather than being referred to a specialty clinic (Bartels et al., 2004; Samuels et al., 2015). Furthermore, a study of the Primary Care Research in Substance Abuse and Mental Health for the Elderly model showed that primary care clinicians thought that “older adults were more likely to experience greater convenience with less stigma if the mental health services were integrated within the primary care setting” (Gallo et al., 2004, p. 307).

Oral Health Integration

Opportunities to integrate oral health services within primary care settings can benefit high-quality whole-person care for people of all ages. Oral health is an essential component of whole health, given that oral disease negatively affects overall health (HHS, 2000). Young children typically do not make a first visit to a dental office until they are 4 or 5 years old, although recommendations are to do so by the first birthday and cost of care is lower for children with an earlier dental visit (Kolstad et al., 2015).

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends at least 12 preventive care visits in the first 5 years (AAP, 2017, 2020), offering multiple opportunities to provide oral health promotion messages, screen for early childhood caries, and apply preventive fluoride varnish in accordance with recommendations of the United States Preventive Services Task Force and AAP (Clark et al., 2020; Moyer, 2014; Segura et al., 2014). That adults are more likely to visit a physician than a dentist in a given year is another opportunity for preventive interventions and oral health condition management (Lutfiyya et al., 2019). Oral health services offered in the primary care setting improve access, decrease the likelihood of needing general anesthesia for pediatric dental concerns (Meyer et al., 2020) and for seeking dental care services at EDs.

In 2020, 59 million Americans lived in 6,296 federally designated dental shortage areas (HRSA, 2020), with many of these areas in rural regions where primary care medical services are available. These primary care sites may offer the best opportunity for screening and primary oral health prevention services for many people. Integration is feasible in rural practices using public health nurses and dental hygienists as part of a primary care team (Dahlberg et al., 2019; Gnaedinger, 2018). Offering preventive oral health services in the medical home has been shown to increase availability for rural individuals and those of underserved racial/ethnic groups with historically less access (Elani et al., 2020; Kranz et al., 2014).

Primary care–oral health integration is in an early stage of development. Advancing structural integration of dentistry into primary care requires implementation strategies that address systemic barriers in both fields. The most prominent such barrier is that dentistry remains the most siloed of the health professions, with services overwhelmingly delivered by small private offices that are dentist centered and operating independently, meaning less of a professional drive to integrate. In the primary care setting, to accomplish even a basic expansion of oral health services requires additional physician and allied staff education and competencies related to oral health. Other barriers to integration include a low priority because of a lack of understanding of the impact of oral health on health in general, Medicare coverage for dental services, and adult Medicaid coverage in many states (Atchison et al., 2018a).

The best integration of primary care and oral health appears to occur when health systems clearly define and view dental care as central to a broad definition of health care and oral health as an essential part of overall health. A series of case studies of medical and dental integration (Maxey et al., 2017) found it was successful when physicians embraced the importance of oral health and championed integration within their clinics. One model gaining acceptance embeds dental hygienists into pediatric practice (Braun and Cusick, 2016), obstetric practices, and diabetes clinics

(Atchison et al., 2018b). Increasingly, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) are making room for dental health integration, but it remains fairly uncommon elsewhere (Highmark Foundation, 2009; Langelier et al., 2015; Maxey, 2014).

Social Needs Integration

In 2014, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation highlighted that medical care has only a fraction of impact on health as compared to other determinants, such as environment and social circumstances (McGovern, 2014). The evidence is clear that social and economic supports, as well as the larger societal structures that support differential access to them, have strong and lasting impact on the health and well-being of individuals, families, and communities (Fichtenberg et al., 2020). However, the evidence of how these SDOH can be most effectively integrated into health care, and into primary care specifically, is still nascent (Gottlieb et al., 2017). Despite the need for more evidence to understand the intricacies of designing, implementing, and sustaining the integration of social needs into primary care, several evidence-based models can guide this integration. Many models of integrated care systems have focused on addressing SDOH, care coordination, and behavioral health needs with a goal of reducing high-cost care for adults with chronic disease (Herrera et al., 2019; NASEM, 2019a). Others, particularly among pediatric populations, have focused on addressing SDOH as a part of more comprehensive preventive care and primary care services (Fierman et al., 2016).

Identifying families with social needs is a first step in primary care–social needs integration. Studies have demonstrated the ability of screening to identify these individuals and families and provide needed referrals (Andermann, 2018; Garg et al., 2016; Herrera et al., 2019). However, both successful connection to these referral sources and a positive impact on health outcomes have been more difficult to achieve (Fiori et al., 2020; Kangovi et al., 2020). Trials of stand-alone screening and referral programs have often failed to demonstrate robust effects on health outcomes, with some studies showing improved health outcomes only for high-risk populations and others demonstrating no or modest effects (Gottlieb et al., 2017; Lindau et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2019). Overall, screening rates for SDOH are low—only 16 percent of physician practices (including primary care practices) surveyed in 2019 screened patients for food insecurity, housing instability, utility needs, transportation needs, and interpersonal violence. Practices providing care for more economically disadvantaged populations reported screening at higher rates (Fraze et al., 2019).

Results have been more promising when addressing social needs is integrated into primary care settings and part of more comprehensive programs

that are relationship based (e.g., use a navigator, community health worker [CHW], or home visitor) and considers additional health and health care needs (Dworkin and Garg, 2019; Gottlieb et al., 2016; Kangovi et al., 2020). For example, an intervention in which CHWs provide tailored social support, navigation, and advocacy to help low-income adults with chronic disease achieve health goals demonstrated positive effects on chronic disease control, such as blood sugar levels and body mass index, and health behaviors, such as tobacco use, patient-perceived quality of care, and hospitalization rates (Kangovi et al., 2018; Lohr et al., 2018). To test another model, researchers conducted a trial of a 2-year, longitudinal, home-based, care management intervention for low-income older adults in community-based health centers using a nurse practitioner and social worker as part of an interprofessional team with the primary care clinician. This approach improved quality of care and reduced acute care use (Counsell et al., 2007). These trials illustrate the importance of integrating social needs as a critical element of care, yet in the context of a longitudinal, relationship-based approach.

There are also several examples of integrating social needs by using CHWs in international settings (Palazuelos et al., 2018). In Brazil, as part of the Family Health Strategy initiative, CHWs are fully integrated into primary care teams and regularly consult physician and nurse team members. The initiative serves approximately two-thirds of the Brazilian population, with a focus on lower-income residents. CHWs make at least one monthly visit to each family, regardless of need, to monitor living conditions and health status, support chronic disease management, triage, and provide basic primary care services. The model enables CHWs to collect high-quality data on each individual and is credited with improving inequity in use and outcomes, improving breastfeeding and immunization rates, and decreasing chronic disease–related hospitalizations (Wadge et al., 2016). In Ghana, the Community-based Health Planning and Services program is built on the notion that community engagement is an essential component of a strong primary care system, deploying nurses (deemed “community health officers”) who provide door-to-door primary care services (Awoonor-Williams et al., 2020). The Equipo Básico de Atención Integral de Salud (basic integrated health care teams) are the foundation of Costa Rica’s primary care system, provide the majority of primary care in the country, and are fully integrated with public health. The teams include a physician, nurse, technical assistant (similar to a CHW), medical clerk, and pharmacist. The technical assistants are responsible for disease prevention and health promotion, sanitation, data collection, and referrals to physicians and hospitals. They engage in community outreach in churches and schools but also make home visits to a geographically empaneled population where they can assist in addressing SDOH overcoming barriers to care (Pesec et al., 2017).

Within child health, team-based approaches to care have been developed and studied to integrate social needs with developmental and behavioral health needs, care coordination, and preventive care needs, with the ultimate goal of positively impacting the child’s—and family’s—life course (Coker et al., 2013a; Fierman et al., 2016; Mooney et al., 2014). Multiple delivery models for child preventive health have used a team-based approach, incorporating non-clinicians to provide preventive developmental services, address SDOH, and generally improve parents’ confidence and efficacy in supporting their child to reach their full potential for health and well-being (Coker et al., 2013b; Freeman and Coker, 2018). These models have demonstrated improved parenting behaviors, parental mental health, and use of preventive care and decreased ED use (Coker et al., 2016; Mendelsohn et al., 2005; Mimila et al., 2017; Minkovitz et al., 2003, 2007). Integrated models for primary care pediatrics that incorporate social needs, particularly for preventive care visits, use strategies such as group care, and employ CHWs, navigators, and health coaches to ensure that the behavioral health and psychosocial needs of families are met (Freeman and Coker, 2018).

The focus on primary care integration is occurring in multiple settings and across a variety of populations. For example, AAP’s Addressing Social Health and Early Childhood Wellness Collaborative is a national initiative to help pediatric primary care practices more effectively implement, measure, and continuously improve integration of key social needs services for families with young children, focusing on screening, counseling, referral, and follow-up related to maternal depression, SDOH, and socioemotional development using quality improvement methodology. It includes a technical assistance and resources center to help practices implement effective screening, referral, and follow-up for these three factors. The collaborative has also established a national learning collaborative of pediatric practices (Flower et al., 2020; Georgia AAP, 2020).

The PACE model of care for older adults described earlier in this chapter also exemplifies the importance of integrating social care needs into the primary care of older adults. In another example, the Ambulatory Integration of the Medical and Social (AIMS) model uses social workers to assess social care needs among patients in primary and specialty care and then integrate needed medical and social care services (Newman et al., 2018). Early evidence suggests that use of the AIMS model may be associated with decreased utilization of health care services (Rowe et al., 2016).

Public Health Integration

Our country’s fragmented response to the COVID-19 pandemic is a clear manifestation of our failure to implement the 1996 report’s recommendations to improve public health–primary care integration so as to

better respond to and manage emergencies and natural disasters. It is apparent from the nation’s response to the pandemic that both primary care and public health had insufficient resources to meet the demand for testing, contact tracing, and treatment and that collaboration was generally insufficient to support combining forces. One systemic barrier to integrating public health and primary care is that for decades, national plans for a public health crisis have not included the role of primary care (HHS, 2017; Holloway et al., 2014). As the virus spread, communication and preparedness protocols between public health entities and those providing frontline primary care was insufficient. Primary care as a sector lacked the funding and policy support needed to provide maximum assistance during the pandemic (Ali et al., 2020); in fact, because of financial pressures arising from the pandemic (and the lack of support to offset them), many independent physician practices across the country have closed or are the verge of closing.

Primary care capabilities to respond to the immediate and long-term health consequences of the pandemic, including economic, mental and social health complications, requires a high level of integration between public health agencies and primary care practices. Now that several vaccines have been approved and are being distributed across the United States, public health and primary care integration will be critical for reaching vulnerable subpopulations lacking access to care, navigating potential vaccine shortages, and tracking vaccine receipt, while monitoring the epidemiology of the ongoing spread and mutation of the virus.

COVID-19 has impacted racial and ethnic minority populations disproportionately, both directly and indirectly, with staggering increases in morbidity and mortality in Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous populations (Azar et al., 2020; Price-Haywood et al., 2020; Vahidy et al., 2020). As a result of pre-existing and systemic inequities in family wealth, housing access, employment, education, and other key factors that affect families’ well-being, Black, Hispanic, Indigenous, and other people of color will disproportionately experience negative, long-term effects on their health and well-being. These communities, more acutely than others, will face an urgent and critical need for integrated, supportive public health and primary care services and interventions to buffer the disproportionate negative health impact of job loss, morbidity and mortality, gaps in education, and increased overall toxic stress during the pandemic and a recovery period.

Despite calls for greater integration of public health and primary care (AAFP Integration of Primary Care and Public Health Work Group, 2015; IOM, 1996, 2012; Welton et al., 1997), primary care practices, public health agencies, and community-based organizations continue to operate separately for the most part, other than large-scale health screening and immunization efforts and literacy promotion and lifestyle modification

initiatives (Levesque et al., 2013; Scutchfield et al., 2012). While some progress has been made, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s attempts to integrate population health into graduate medical education competencies and numerous demonstration programs that work toward integration (CDC, 2016), true integration remains limited.

Benefits of Public Health Integration

Public health–primary care integration has many benefits beyond crisis situations. A close partnership can improve the treatment of chronic conditions and increase the effectiveness and enhance dissemination of prevention and health promotion. Integration also increases the capacity of primary care to influence public health, by bringing a larger focus to the health of a community through connected healing and trusted relationships, thereby reaching individuals and their families who otherwise may not access primary care services. Public health nursing programs, such as Nurse–Family Partnerships, show cost-effectiveness for reaching high-risk families (Wu et al., 2017). Schools and day care centers are integration avenues, with opportunities to reach children, adolescents, and their families. Other “third places,”1 such as senior centers, places of worship, adult day care facilities, barber shops and beauty salons, and libraries, can increase access to services for older adults (Keeton et al., 2012; Northridge et al., 2016; Riley et al., 2016).

Comprehensive Data Integration

Achieving the most effective integration of primary care and public health requires integrating the data that these two sectors produce, which supports process integration protocols within and across settings to monitor and improve outcomes. Cross-sector data integration for enhanced community and population health interventions within primary care is a key area of opportunity, particularly to expand the reach of a traditional primary care setting. Primary care practice data can help public health professionals conduct surveillance and community assessments, while access to public health data for primary care team members can allow them to observe information on community needs beyond the “micro” practice level and conduct proactive risk identification (IOM, 2012). A prime example of this is Hennepin Health in Minnesota, an ACO with four partners: the Hennepin County Human Services and Public Health Department; the Hennepin County Medical Center; NorthPoint Health, an FQHC; and the

___________________

1 “Third places” are public places on neutral ground where people may gather, enjoy the company of others, and interact (Oldenburg, 1989).

Metropolitan Health Plan, a nonprofit, county-run Medicaid managed care plan. The technological centerpiece of the ACO includes three elements:

- a unified electronic health record system shared by all partners;

- electronic data dashboards that provide information tailored to team member needs; and

- an integrated data warehouse that incorporates data from health plan claims and enrollment, the electronic health record (EHR), and social service records (Sandberg et al., 2014).

During a 2016 analysis, Hennepin Health—the default option for newly eligible Medicaid beneficiaries in Hennepin County who do not select a plan—was working to incorporate nonmedical information from housing providers, the foster care system, the corrections department, and other local agencies (Hostetter et al., 2016). By sharing data, the ACO could stratify members into risk tiers and send CHWs and social workers to connect those at the highest risk to primary care and the other medical, behavioral, or social services. Often, these individuals likely would not have a relationship with primary care otherwise (Sandberg et al., 2014).

Comparing Hennepin’s second and third years of operation, it saw a 9.1 percent overall decrease of ED visits and a 3.3 percent increase of outpatient primary care visits. For members receiving housing assistance through Hennepin, who account for up to 50 percent of members, ED visits fell by 35 percent and outpatient clinic visits, including to primary care, increased by 21 percent (Hostetter et al., 2016). In redesigning the way public health entities interacted with primary care settings in Hennepin County, as opposed to creating new programs or relying on additional funding, Hennepin Health has been able to sustain its integrated partnerships.

Specialist and Hospitalist Integration

Key to high-functioning primary care teams is a readily available system for referral of patients from primary care to specialist care when needed. From 1999 to 2009, referrals in the United States from primary care to specialty care more than doubled from 41 million to 105 million (Barnett et al., 2012). Unfortunately, there is little evidence that effective coordination is the norm between the specialist, primary care team, and the patient. Currently, patients with multiple chronic conditions often receive care from multiple specialty groups, adding to duplication in services, inconvenience with making follow-up appointments across multiple providers, and potential medical error with one specialist being unaware of the treatment protocol being prescribed by another specialist (Vimalananda et al., 2018). Studies have shown that well-coordinated primary and specialty services lead to reductions in acute care and more efficient use of specialty care

(Newman et al., 2019). Three factors could improve this process including clear communication and buy-in between services, EHR interoperability, and engagement of the patient and family in care coordination.

While patients should be referred for specialist care in complex situations, the referral process should not mean that the primary care service is abdicating their role in the management of the patient’s condition. Shared responsibility is necessary to have a fully integrated care model. Furthermore, when a primary care team’s patient is hospitalized, the team should manage the care or coordinate care with hospitalists to ensure that knowledge of the patient and family is available, coordinate as the patient nears discharge, and manage care post-discharge. Studies have shown that poor care coordination affects patient clinical outcomes and satisfaction with their care. Coordination across settings affects patients’ clinical outcomes and satisfaction with their care (Weinberg et al., 2007). Systems should support shared responsibility between the primary care team and the hospital team for inpatient care and for informed transitions back to primary care.

IMPLEMENTATION FACILITATORS: HOW TO INTEGRATE PRIMARY CARE DELIVERY

Even when organizations are successful delivering consistently high quality or value through integrated processes, the approaches they use and lessons they learn are not easily scaled beyond their walls because of the unique structures and resources of the local environment. However, though individual characteristics of these high-performing organizations may differ, they do share four similar delivery habits—repeated behaviors and activities and the ways of thinking that they reflect and engender (Bohmer, 2011)—that are integrated systematically into the organizational culture, workflows, and clinical management focused on outcomes and building value. The leaders of these organizations routinely invest in the following:

- planning and developing specifications well in advance of implementation, enabling them to integrate operational and clinical decision making with explicit criteria and parse heterogeneous patient populations into clinically meaningful subtypes;

- infrastructure design of microsystems—staff, information technologies, clinical technologies, physical space, business processes, and policies and procedures supporting patient care—to match their subpopulation with workflows, training, and how they allocate resources to the different members of the clinical team;

- measurement and oversight designed for internal process controls and performance rather than being driven by the need to report to external regulators, payers, and rating agencies; and

- self-study to examine positive and negative deviances in care and outcomes, ensure their clinical practices are consistent with latest science, and create new knowledge and innovations (Bohmer, 2011).

When considering how integrated delivery provides the context to achieve high-quality primary care, these habits highlight the normative culture that organizations can promote to support implementing and adopting the following facilitators.

Digital Health Integration

Digital technology with data system integration is a key facilitator of integrated care delivery and foundational to achieving accessible high-quality primary care. As noted in Chapter 1, no other aspect of patient care delivery has changed as much since the 1996 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report as the ubiquitous use of digital technology, which is playing an important role in disrupting the paternalistic status quo of care and transforming primary care into more equitable partnerships between individuals and their primary care team (Meskó et al., 2017). At the same time, digital health technologies support collecting and organizing person-generated health care data that can generate new findings and new analytical tools to improve person-centered care (Sharma et al., 2018). These technologies allow individuals to access their own data, interact remotely with their care team, and even provide real-time monitoring and diagnostic information that can better inform treatment (Buis, 2019).

Digital health tools and innovations can be a critical element of true integrated care delivery. For example, text messaging, telehealth, and app-based tools can extend the services, and thus impact, of a single primary care visit (Coker et al., 2019; Levin et al., 2011; Stockwell et al., 2012; van Grieken et al., 2017). See Chapter 7 for more on digital health in primary care.

Accountability Integration

Accountability for developing, implementing, governing, and monitoring integrated team-based care is a critical facilitator for measuring high-quality primary care outcomes. Accountability requires that the normative integration culture values measured self-study and empirical evidence that facilitates improvements over time and demonstrates and quantifies that primary care adds value to the overall health care system. The successful integrated delivery systems noted earlier had explicit processes for accountability and evaluation.

Payment Model Integration

Investing in integrated care to deliver high-quality primary care while reducing cost and the strain on resources remains a promising global solution to disparities in access and reducing overall health care cost. However, the cost-effectiveness of integrated care remains unclear except when integrated delivery systems conducted follow-up assessments for a sufficient time to compensate for implementation costs and reflect long-term benefits (Rocks et al., 2020).

There are limited examples of whole-person, integrated care delivery models with a supportive payment system that researchers have studied rigorously and produced findings to demonstrate improved care and decreased overall costs of care. Partners for Kids, an Ohio ACO, receives a per-member, per-month payment—the average of the age- and gender-adjusted capitated fee for each child enrollee per month—through the five state Medicaid managed care plans. While Partners for Kids takes full financial and clinical risk for its Medicaid enrollees, it also retains any savings from the cost of care. The delivery model incorporated team-based care with non-clinicians, behavioral health integration, care coordination, and a focus on population health. When compared with FFS Medicaid, this program demonstrated a lower rate of cost growth without reducing quality measures or outcomes of care (Kelleher et al., 2015).

Hennepin Health offers a broad array of integrated services, including care coordination, behavioral health, and dental care. Its evaluation of newly onboarded, very low-income adults during Medicaid expansion found that 6 months of continuous enrollment was associated with less use of the ED and hospital and more use of primary and dental care (Vickery et al., 2020).

Integrated Care for Kids (InCK) is a child- and family-centered integrated delivery care model with a matched state payment model for children insured by Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program. The model aims to reduce expenditures and improve the quality of care for children and adolescents from birth to age 21 through prevention, early identification, and treatment of behavioral and physical health needs. Seven states received federal funding at the start of 2020 to launch this system, with a sustainable alternative payment model to support it.2 Initiatives such as InCK explicitly require a state-specific alternative payment model that aligns payment with care quality and health outcomes and has the goal of long-term sustainability.

While an aligned payment system is integral to short- and long-term sustainability of integrated primary care delivery, it is also critical to have

___________________

2 Additional information is available at https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/integrated-care-for-kids-model (accessed February 14, 2021).

the financial resources to support design and implementation activities and the initial start-up of an integrated primary care practice. In fact, barriers to implementing integrated primary care delivery include the high start-up costs for cultural and quality transformation; hiring and training the primary care team, including team members focused on chronic and preventive care (Peikes et al., 2014); and hiring team members who deliver behavioral health services (Beil et al., 2019).

Implementing Team-Based Integrated Primary Care at the Practice and Clinic Levels

Meeting the committee’s definition of high-quality primary care (see Chapter 2) requires coordinated integrated care delivery structures and processes. Integrated care delivery galvanizes the shift of primary care from a procedural service to the relational provision of whole-person care that produces person, family, and community health and well-being.

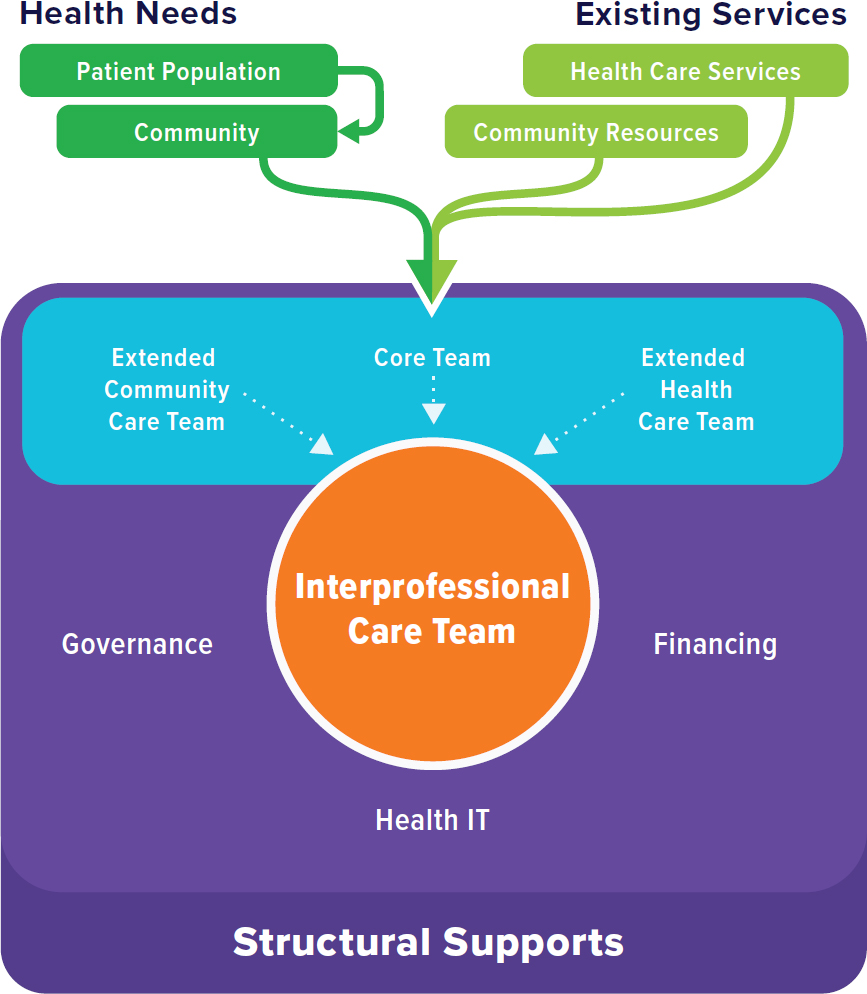

Integration on a structural level that includes interprofessional teams that provide whole-person care to individuals and families is required for success. Creating the structural elements of integration is generally the first step for primary care practices and clinics. Implementing these structural elements can begin with asking the basic question of what range of services to include in an integrated model of care (e.g., behavioral health, social services, oral health care, pharmacy services, complex care coordination) to meet the needs of the population and then developing an understanding of the interprofessional team needed to provide, coordinate, and engage individuals and families in this care (e.g., care coordinators, CHWs, therapists) (Starfield, 1998). The team members will likely need to develop external partnerships with community resources outside of the traditional health care team (e.g., schools, day care centers, pharmacies). Finally, once the range of services, team, composition, and community partnerships have been established for high-quality primary care, a practice must determine what supportive structural elements. These can include a governance structure to hold leadership accountable to ensuring that primary care addresses community needs, information systems and workflow to support team communication and coordination while keeping the individual and family central to care, and financing that can support the independent contributions of each team member to meet the specific needs of individuals and families (see Figure 5-2).

Many practices and clinics will face challenges paying for many of the structures needed for team-based integrated care. Without these structures, however, practices will not fully develop the processes needed for high-quality primary care. Prior to the widespread use of hybrid payment models that better support team-based integrated care, some practices will be able

to capitalize on the efficiencies gained in team-based care that shift preventive care, chronic care management, and social needs support to other team members, which can allow primary care clinicians to use their time more efficiently to address more complex medical needs.

Small practices, especially those in rural settings, may have additional challenges of finding personnel, independent of payment mechanisms, for integrated team-based care. These practices will likely rely more on external community partnerships for a more virtual integration of behavioral health, social needs, oral health, and public health. Small practices without the space, personnel, or resources to support the team necessary for integrated care can also band together to benefit from economies of scale (Mostashari, 2016) by sharing centralized personnel and other necessary resources that are otherwise not available at the practice level for team-based integrated care. The exponential expansion of telehealth and virtual visits also provides a feasible option for care delivery using shared resources across practices. For example, small- and medium-sized practices that participate in independent practice associations and physician–hospital organizations are more likely to have care management processes for adults with chronic conditions (Casalino et al., 2013). Practices may also consider incorporating CHWs (Kangovi et al., 2020) or pharmacists into their primary care to meet the needs of individuals and families.

Research Integration

As alluded to above, several areas for care delivery integration would benefit from more research, such as to establish the training requirements for effectively translating behavioral health interventions for primary care settings and community-based delivery that is more culturally relevant and logistically feasible for individuals and families (e.g., matching the number of therapeutic contacts and non-face-to-face formats for specified behavioral health interventions). Research should also be conducted to help primary care settings have a more adaptable framework for implementing integrated care that can meet their internal business and community-specific needs and determine how to best take advantage of the expanding role of digital and eHealth tools in integrated care. It is also critical that all research focused on continuous relationships and care integration be targeted to the populations that face the widest health inequities as a means of reducing these inequities (Lion and Raphael, 2015).

Leadership Integration

Strong, committed, and collective leadership is one of the most important facilitators of building and leading teams of practices through the

NOTE: IT = information technology.

inherently challenging processes of culture change and integrating whole-person care across settings. While Chapter 1 discussed how the lack of leadership at local, state, and national levels played a central role in the failure of the 1996 IOM recommendations to take hold in primary care, leadership at the practice level is also important for successful transformation to person- and family-centered and community-oriented practice. One study found, for example, that practices with higher leadership scores had higher odds of making changes (Donahue et al., 2013). A systematic review, however, found little research on the effectiveness of clinical leadership on integrated primary care practice and outcomes for individuals (Nieuwboer et al., 2019). What research has identified are two important leadership styles that appear to contribute to fostering integrated care: collective leadership that influences team members based on social interactions (Forsyth

and Mason, 2017) and transformational leadership that achieves change through charisma and motivational approaches that get staff to achieve more than what is expected of them and challenges staff to look beyond self-interest (Dionne et al., 2014).

Several research groups and organizations have created programs for developing leaders to support team-based primary care. One effort funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation developed the 12-month Emerging Leaders program to “demonstrate the relevance of an interdisciplinary cohort approach to leadership development; model a new way of working across silos in teams”; and enhance multiple aspects of leadership development, including confidence and skill development (Coleman et al., 2019, p. 2). One element was the policy of reimbursing practices for the expense of covering staff who participated. At the organizational level, the American Academy of Family Physicians has established the Primary Care Leadership Collaborative,3 which supports medical student teams committed to advancing primary care and improving the health of their communities.

Policy, Laws, and Regulations

Health centers are leaders in adoption of specific PCMH elements that can facilitate implementing integrated care. These elements include onsite behavioral health or social workers, an onsite care coordinator/patient navigator, routine comprehensive health assessments, including SDOH, referrals based on SDOH, and clinical tools and resources to address SDOH (Rittenhouse et al., 2020). To enable this level of integration, the Health Resources and Services Administration’s policies stipulate providing critical resources: technical assistance, a related national cooperative agreement with the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) to facilitate certification, funds to pay for certification, and financial incentives, including increased payments for quality for health centers that were NCQA recognized. The onsite availability of these services (behavioral health, social work) represents a structural facilitator for implementing integrated primary care delivery, but it is not sufficient to achieve sustained implementation of integrated care. From the Theory of Integration discussed earlier, these health centers would possess the organizational features of structural integration and then need ongoing measurement and monitoring to further implement the functional, normative, interpersonal, and process elements of integration to achieve integrated primary care.

___________________

3Additional information is available at https://www.aafp.org/students-residents/medicalstudents/fmig/pclc.html (accessed February 14, 2021).

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Evidence supports structures and processes that incorporate the elements necessary for optimal, whole-person health, including integrating behavioral health services, oral health care, social needs, and population and public health. While many structures of primary care integration are still underdeveloped, the evidence is convincing that behavioral health integration for both child and adult populations is effective at improving clinical outcomes and lowering costs and should be advanced, scaled, and accessible immediately. This evidence is evolving for social, public health, and oral health integration as well. Several examples of integrated high-quality primary care include functional integration across various areas and demonstrate evidence of improved clinical outcomes and higher quality of care without large spending increases and sometimes even reduced costs in the short run (Kelleher et al., 2015). The most successful models, and thus sustainable ones, are likely to have payment systems and a leadership structure that promote a strong culture of functional integration and the production of high-quality outcomes. Integration, however, is not one size fits all—practices and systems should strive to integrate services based on the needs of the community they serve. Practices in locations where resources are scant can partner with each other to pool resources, connect virtually to needed services, and consider including additional team members such as CHWs or pharmacists into their practices.

For primary care integration to advance, payment systems will need to move away from FFS and toward mandatory hybrid models or other alternative models, including ACO models, in which organizations can reap the financial benefits of improving health and well-being, and provide incentives to invest in start-up costs associated with planning, specifying, and designing the infrastructure of an effective integrated delivery system that thrives on interprofessional teams for high-quality care. These payment models must also consider the long-term savings in investments in prevention, health promotion, coordinated and whole-person and family-centered chronic care management, and early diagnostic and treatment services, which may impact sectors outside of health care, including education, social services, and the justice system. Thus, new payment models, including value-based payment, must account for and incentivize these additional outcomes.

In addition to policies and payment structures not explicitly supporting integrated primary care delivery, care transformation and value-based payment initiatives can have downsides. Clinicians may game performance to avoid penalties (Sjoding et al., 2015) and incur high administrative costs to report measures for external incentive programs (Casalino et al., 2016).

Hybrid payment with multi-payer alignment would reduce administrative burden (including data collection) and limit the need for condition-specific, value-based payments, while encouraging expanded use of CHWs, health coaches, and other staff who can support integrated care delivery.

Aligned structures, policies, and leadership are not sufficient for sustainable integrated care; each delivery system must create clear systematic implementation processes, including clinical and operational workflows that allow teams to work together to meet the individual and complex medical, social, and behavioral health needs of individuals and families. These processes will often include digital or eHealth innovations and a clear system for data collection, measurement, and “self-study” continuous improvement, which will produce innovations equitably matched to improve health at the community or population level.

Innovative integrated care delivery models will likely continue to expand in the private sector, particularly as the for-profit, direct-to-consumer industry of personalized and concierge health care grows. However, to stop the continued growth of health inequities for low-income, Black, brown, and Indigenous communities, it will be important to develop and implement policies, payment structures, and other facilitators that will advance health equity and allow everyone to receive high-quality, integrated primary care. If primary care remains the largest platform for continuous, relationship-based care in the United States, one that considers the needs and preferences of individuals, families, and communities, then this essential function of providing health care value requires significant investment in implementing already proven integrated delivery methods and structures for all.

REFERENCES

AAFP (American Academy of Family Physicians) Integration of Primary Care and Public Health Work Group. 2015. Integration of primary care and public health (position paper). https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/integration-primary-care.html (accessed November 20, 2020).

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). 2017. Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children and adolescents, 4th ed. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

AAP. 2020. Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2013. Lexicon for behavioral health and primary care integration. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

AHS (Vermont Agency of Human Services). 2019. Blueprint for health 101. Montpelier, VT: Vermont Agency of Human Services.

Ali, M. K., D. J. Shah, and C. Del Rio. 2020. Preparing primary care for COVID-20. Journal of General Internal Medicine. Epub ahead of print.

Andermann, A. 2018. Screening for social determinants of health in clinical care: Moving from the margins to the mainstream. Public Health Reviews 39:19.

Anderson, L. E., M. L. Chen, J. M. Perrin, and J. Van Cleave. 2015. Outpatient visits and medication prescribing for U.S. children with mental health conditions. Pediatrics 136(5):e1178–e1185.

Archbald-Pannone, L. R., D. A. Harris, K. Albero, R. L. Steele, A. F. Pannone, and J. B. Mutter. 2020. COVID-19 collaborative model for an academic hospital and long-term care facilities. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 21(7):939–942.

Archer, J., P. Bower, S. Gilbody, K. Lovell, D. Richards, L. Gask, C. Dickens, and P. Coventry. 2012. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 10:CD006525.

Areán, P. A., L. Ayalon, E. Hunkeler, E. H. Lin, L. Tang, L. Harpole, H. Hendrie, J. W. Williams, Jr., and J. Unützer. 2005. Improving depression care for older, minority patients in primary care. Medical Care 43(4):381–390.

Arora, S., C. Fassler, L. Marsh, T. Holmes, G. Murata, S. Kalishman, D. Dion, J. Scaletti, W. Pak, and T. Peterson. 2008. Project ECHO: Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Asarnow, J. R., K. E. Hoagwood, T. Stancin, J. E. Lochman, J. L. Hughes, J. M. Miranda, T. Wysocki, S. G. Portwood, J. Piacentini, D. Tynan, M. Atkins, and A. E. Kazak. 2015a. Psychological science and innovative strategies for informing health care redesign: A policy brief. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 44(6):923–932.

Asarnow, J. R., M. Rozenman, J. Wiblin, and L. Zeltzer. 2015b. Integrated medical-behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavioral health: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics 169(10):929–937.

Atchison, K. A., R. G. Rozier, and J. A. Weintraub. 2018a. Integration of oral health and primary care: Communication, coordination, and referral. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC.

Atchison, K. A., J. A. Weintraub, and R. G. Rozier. 2018b. Bridging the dental-medical divide: Case studies integrating oral health care and primary health care. Journal of the American Dental Association 149(10):850–858.

Awoonor-Williams, J. K., E. Tadiri, and H. Ratcliffe. 2020. Translating research into practice to ensure community engagement for successful primary health care service delivery: The case of CHPS in Ghana. PHCPI. https://improvingphc.org/translating-research-practice-ensure-community-engagement-successful-primary-health-care-service-delivery-case-chps-ghana (accessed November 18, 2020).

Azar, K. M. J., Z. Shen, R. J. Romanelli, S. H. Lockhart, K. Smits, S. Robinson, S. Brown, and A. R. Pressman. 2020. Disparities in outcomes among COVID-19 patients in a large health care system in California. Health Affairs 39(7):1253–1262.

Barnett, M. L., Z. Song, and B. E. Landon. 2012. Trends in physician referrals in the United States, 1999–2009. Archives of Internal Medicine 172(2):163–170.

Bartels, S. J., E. H. Coakley, C. Zubritsky, J. H. Ware, K. M. Miles, P. A. Areán, H. Chen, D. W. Oslin, M. D. Llorente, G. Costantino, L. Quijano, J. S. McIntyre, K. W. Linkins, T. E. Oxman, J. Maxwell, and S. E. Levkoff. 2004. Improving access to geriatric mental health services: A randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. American Journal of Psychiatry 161(8):1455–1462.

Beil, H., R. K. Feinberg, S. V. Patel, and M. A. Romaire. 2019. Behavioral health integration with primary care: Implementation experience and impacts from the State Innovation Model Round 1 states. Milbank Quarterly 97(2):543–582.

Bitton, A., J. H. Veillard, L. Basu, H. L. Ratcliffe, D. Schwarz, and L. R. Hirschhorn. 2018. The 5S-5M-5C schematic: Transforming primary care inputs to outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health 3(Suppl 3):e001020.

Bohmer, R. M. 2011. The four habits of high-value health care organizations. New England Journal of Medicine 365(22):2045–2047.

Boult, C., and G. D. Wieland. 2010. Comprehensive primary care for older patients with multiple chronic conditions: “Nobody rushes you through.” JAMA 304(17):1936–1943.

Braun, P. A., and A. Cusick. 2016. Collaboration between medical providers and dental hygienists in pediatric health care. Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice 16:59–67.

Browne, A. J., C. M. Varcoe, S. T. Wong, V. L. Smye, J. Lavoie, D. Littlejohn, D. Tu, O. Godwin, M. Krause, K. B. Khan, A. Fridkin, P. Rodney, J. O’Neil, and S. Lennox. 2012. Closing the health equity gap: Evidence-based strategies for primary health care organizations. International Journal for Equity in Health 11(1).

Buckley, D. I., P. McGinnis, L. J. Fagnan, R. Mardon, J. Johnson, Maurice, and C. Dymek. 2013. Clinical-community relationships evaluation roadmap. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Buis, L. 2019. Implementation: The next giant hurdle to clinical transformation with digital health. Journal of Medical Internet Research 21(11):e16259.

Casalino, L. P., F. M. Wu, A. M. Ryan, K. Copeland, D. R. Rittenhouse, P. P. Ramsay, and S. M. Shortell. 2013. Independent practice associations and physician-hospital organizations can improve care management for smaller practices. Health Affairs 32(8):1376–1382.

Casalino, L. P., D. Gans, R. Weber, M. Cea, A. Tuchovsky, T. F. Bishop, Y. Miranda, B. A. Frankel, K. B. Ziehler, M. M. Wong, and T. B. Evenson. 2016. U.S. physician practices spend more than $15.4 billion annually to report quality measures. Health Affairs 35(3):401–406.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2016. Advancing integration of population health into graduate medical education. https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/academicpartnerships/wip/milestone.html (accessed August 5, 2020).

Clark, M. B., M. A. Keels, and R. L. Slayton. 2020. Fluoride use in caries prevention in the primary care setting. Pediatrics 146(6):e2020034637.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2021a. Program of all-inclusive care for the elderly. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/long-term-services-supports/program-allinclusive-care-elderly/index.html (accessed February 11, 2021).

CMS. 2021b. Programs of all-inclusive care for the elderly benefits. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/long-term-services-supports/pace/programs-all-inclusive-care-elderly-benefits/index.html (accessed February 11, 2021).

Coker, T. R., T. Thomas, and P. J. Chung. 2013a. Does well-child care have a future in pediatrics? Pediatrics 131(Suppl 2):S149–S159.

Coker, T. R., A. Windon, C. Moreno, M. A. Schuster, and P. J. Chung. 2013b. Well-child care clinical practice redesign for young children: A systematic review of strategies and tools. Pediatrics 131(Suppl 1):S5–S25.

Coker, T. R., S. Chacon, M. N. Elliott, Y. Bruno, T. Chavis, C. Biely, C. D. Bethell, S. Contreras, N. A. Mimila, J. Mercado, and P. J. Chung. 2016. A parent coach model for well-child care among low-income children: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 137(3):e20153013.

Coker, T. R., L. Porras-Javier, L. Zhang, N. Soares, C. Park, A. Patel, L. Tang, P. J. Chung, and B. T. Zima. 2019. A telehealth-enhanced referral process in pediatric primary care: A cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics 143(3).

Coleman, K., E. H. Wagner, M. D. Ladden, M. Flinter, D. Cromp, C. Hsu, B. F. Crabtree, and S. McDonald. 2019. Developing emerging leaders to support team-based primary care. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management 42(4).

Colwill, J. M., J. J. Frey, M. A. Baird, J. W. Kirk, and W. W. Rosser. 2016. Patient relationships and the personal physician in tomorrow’s health system: A perspective from the Keystone IV conference. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 29(Suppl 1):S54–S59.

Coulson, C. C., and S. Galvin. 2020. Navigating perinatal care in western North Carolina: Access for patients and providers. North Carolina Medical Journal 81(1):41–44.

Counsell, S. R., C. M. Callahan, D. O. Clark, W. Tu, A. B. Buttar, T. E. Stump, and G. D. Ricketts. 2007. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 298(22):2623–2633.

Coventry, P., K. Lovell, C. Dickens, P. Bower, C. Chew-Graham, D. McElvenny, M. Hann, A. Cherrington, C. Garrett, C. J. Gibbons, C. Baguley, K. Roughley, I. Adeyemi, D. Reeves, W. Waheed, and L. Gask. 2015. Integrated primary care for patients with mental and physical multimorbidity: Cluster randomised controlled trial of collaborative care for patients with depression comorbid with diabetes or cardiovascular disease. BMJ 350:h638.