6

Designing Interprofessional Teams and Preparing the Future Primary Care Workforce

The ability to deliver high-quality primary care depends on the availability, accessibility, and competence of a primary care workforce assembled in interprofessional teams to effectively meet the health care needs of diverse care-seekers, families, and communities. People with access to high-quality primary care have better health outcomes, including improvements in chronic disease control, receipt of more preventive services, fewer preventable emergency room visits and hospitalizations, improved health equity, improved quality of life, and longer lives (Basu et al., 2019; Shi, 2012; Starfield et al., 2005). These better outcomes are pronounced among the poor and underserved (Beck et al., 2016; Phillips and Bazemore, 2010; Regalado and Halfon, 2001; Seid and Stevens, 2005).

This chapter focuses on the evidence supporting challenges and innovative solutions to creating interprofessional primary care teams that can offset the eroding capacity of primary care clinicians to deliver a broad scope of person- and family-centered care. The chapter will also discuss key design elements of interprofessional teams and highlight the roles that extended care team members and care team members from the community can play in delivering high-quality primary care. The chapter will then address the diversity of the primary care workforce and the education and training needed to prepare a workforce equipped to meet the growing primary care needs of care-seekers, families, and communities.

DESIGNING THE INTERPROFESSIONAL PRIMARY CARE TEAM

A commonly used definition of team-based care is

the provision of health services to individuals, families, and/or their communities by at least two health providers who work collaboratively with patients and their caregivers—to the extent preferred by each patient—to accomplish shared goals within and across settings to achieve coordinated, high-quality care. (IOM, 2011a; Mitchell et al., 2012, p. 5; Okun et al., 2014, p. 46; Schottenfeld et al., 2016)

High-quality primary care is best provided by a team of clinicians and others who are organized, supported, and accountable to meet the needs of the people and the communities they serve. Team-based care improves health care quality, use, and costs among chronically ill patients (Pany et al., 2021; Reiss-Brennan et al., 2016), and it also leads to lower burnout in primary care (Willard-Grace et al., 2014). Well-designed teams can support nurturing, longitudinal, person-centered care (Mitchell et al., 2012; Sullivan and Ellner, 2015).

Integrated, interprofessional team-based care requires leadership at all levels of the organization, decision-making tools, effective communication, and real-time information that supports whole-person care. In combination, these requirements ensure that a competent, trusted group of health care professionals working together adequately addresses physical health, behavioral health, social needs, and oral health (Ellner and Phillips, 2017). See Chapter 5 for more insight into the delivery of integrated care and how to approach integration.

Meeting the Needs of Patients and the Community

Team-based care will look different depending on the health needs and demographics of the population; the setting in which it receives care; the distinct regional, economic, and sociocultural contexts of the community in which that population lives; and the assets of that community. Ideally, the team should reflect the diversity of the patients and community it serves (Katkin et al., 2017), and because the needs of patients and their families will change over time, primary care teams should be able to evolve in response to those changing needs (Bodenheimer, 2019b; Bodenheimer and Smith, 2013; Brownstein et al., 2011; Coker et al., 2013; Fierman et al., 2016; Grumbach et al., 2012; Katkin et al., 2017; Margolius et al., 2012).

Community-oriented primary care, as discussed in Chapter 4, is an approach to care delivery by which services—both health care and community-based resources—are designed and organized to meet the specific

needs of a given population and community. This approach involves health facilities or systems completing an epidemiologic assessment of the population to identify its specific health needs, which may include social services in addition to traditional health services (IOM, 1983). Health centers, for example, must complete these assessments every 3 years and often do so in collaboration with hospitals and public health departments (HRSA, 2018). Every 3 years, as a condition of their tax-exempt status, nonprofit hospitals are also required to complete a community health assessment and, based on the results, develop an implementation plan to meet the needs of their populations.1 Assessments can include a review of the geographic boundaries of the population served; any barriers to care, including transportation and child care; unmet health needs of the medically underserved in that population, including the ratio of primary care physicians (PCPs) relative to the population; health indexes for the population; the population’s poverty level; and other demographic factors that affect the demand for services, such as the percentage of the population over age 65. Needs assessments similar to those produced by health centers can guide the efforts of primary care teams in conducting community health assessments of their own and inform the composition of the primary care team to match the specific needs of the community it serves.

The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated the need for primary care practices to adapt quickly to changing needs in their communities. In particular, the pandemic highlighted that expanded access to care is necessary, and many states relaxed or waived scope of practice requirements for advanced practice nurses and pharmacists (Cadogan and Hughes, 2020; Hess et al., 2020; Zolot, 2020). This change has led to reports of improved patient access and opened the door to discussions to permanently rethink team members’ scope of practice to better meet community needs and reduce barriers to care (AANP, 2020a; Aruru et al., 2021; Feyereisen and Puro, 2020).

Designing Teams for Success: Structure and Culture

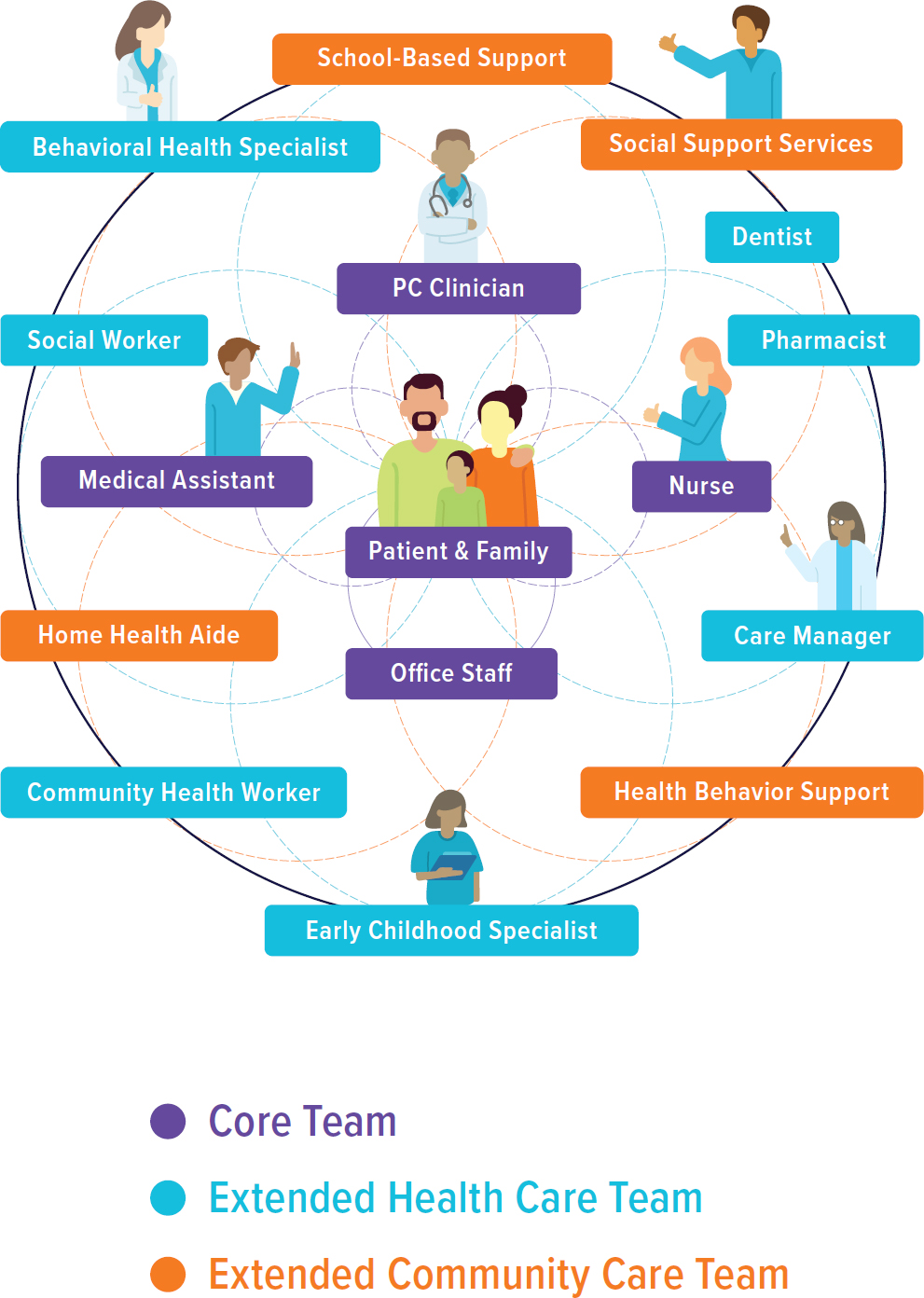

Interprofessional primary care teams should have a structure and a culture (Bodenheimer, 2019a), which are concepts critical to effective team design (Schottenfeld et al., 2016). The typical structure of an interprofessional primary care team includes a core team, an extended health care team, and what the committee refers to as the “extended community care team” (see Figure 6-1 for an overview of the interprofessional team). Each

___________________

1 26 Internal Revenue Code § 501(r). For more information, see https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/charitable-organizations/requirements-for-501c3-hospitals-under-the-affordablecare-act-section-501r (accessed February 27, 2021).

NOTE: PC = primary care.

segment of the interprofessional primary care team is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

A defining feature of a care team is its stability. Stability ensures that members of the team work together consistently to support one another and that the team includes consistent individuals who care for patients and their families and can form stable relationships with them. The core, extended health care, and the extended community care teams require seamless, coordinated, and integrated care delivery processes to ensure that whole-person care is provided to each person. That only comes when the team composition remains stable over time, which allows team members to learn how to best work with one another in a seamless, coordinated, and integrated manner (see Chapter 4) and the care-seeker to know and trust the multiple members of the team.

Planning strategically and distributing the functions of care across various team members, including health professionals working at the top of their scope of practice and non-clinical personnel assuming responsibility for other functions, helps distribute work tasks and functions to those best prepared to implement them. Primary care clinicians are too busy to assume responsibility for all the functions required to meet every need, and no single clinician can be expected to have the expertise and skills needed to do so and do it well (Bodenheimer, 2019a). Aligning each respective team member’s competencies and capabilities with the actual work that must be done not only shifts excess work away from the primary care clinician but places it in the hands of those who are educated and trained to execute those tasks. Doing so creates opportunities for each team member to contribute meaningfully to the work that needs to be done, further strengthening team culture (Bohmer, 2011; Sinsky et al., 2013). While team-based delivery distributes many functions across the team, doing so does not diffuse individual accountability, including that of the primary care clinician who is ultimately accountable for a patient’s care.

One successful interprofessional primary care model is the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA’s) Patient-Aligned Care Team (PACT). This care team model incorporates clinical and support staff who deliver all primary care functions and coordinate the remaining needs, including specialty care. To optimize workflow and enhance continuity of care, staff are organized into “teamlets” that provide care to an assigned panel of about 1,200 patients. A teamlet consists of a PCP, physician assistant (PA) or nurse practitioner (NP), registered nurse (RN) care manager, licensed practical nurse or medical assistant, and administrative clerk (Gardner et al., 2018). PACTs have been associated with a decrease in hospitalizations, specialty care visits, emergency department (ED) use, and increased overall mental health visits but decreased visits with mental health specialists outside of a primary care setting (thanks to the VA’s separate Primary

Care-Mental Health Integration program), along with lower levels of staff burnout, higher patient satisfaction and access to care, increases in use of preventive services, and improvements in clinical outcomes for patients with diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension (Bidassie, 2017; Hebert et al., 2014; Leung et al., 2019; Nelson et al., 2014; Randall et al., 2017; Rodriguez et al., 2014).

A study of 23 high-performing primary care practices examined how they distribute functions among the team members, use technology to their advantage, use data to improve outcomes, and bring joy to their work (Sinsky et al., 2013). The study elucidated several important characteristics of high-performing teams:

- They are proactive and provide well-thought-out care, including pre-visit planning and laboratory testing.

- They distribute and share the delivery of care among the team members.

- They share clerical tasks, such as documentation, non-physician order entry, and prescription management, among a variety of team members.

- They enhance communication through a variety of strategies.

- They optimize the function of the team through colocation, team meetings, huddles, and mapping workflow.

The study also found that shifting work from a physician-centric model of care to a shared, team-based model of care results in improved professional satisfaction and a greater joy in practice. Consistent with these findings, evidence is mounting that interprofessional primary care teams can improve care quality, reduce health care costs, decrease clinician burnout, and improve the patient experience, but this requires that teams are truly distributing the work and sharing the care responsibilities (Meyers et al., 2019). Producing and sustaining this effective level of high-functioning teamwork requires leadership that recognizes and rewards team-based care.

In addition to its structure, the team’s culture is foundational, relational, and reflective of the mission and vision of the organization or practice. Team culture is reflected in how members function together and value each other’s role and how they distribute the tasks among each other to reach quality outcomes. It is well known that the roles and functions of individual team members are often poorly defined, and teams are often under-resourced for the work they need to do, leading to chronic misdistribution of effort, exhaustion of human capital, and often less than optimal care (Hysong et al., 2019; Sinsky and Bodenheimer, 2019). Research also suggests that PCPs, who are most often trained individually in hospital settings, are often unskilled at or uncomfortable in a true team-based environment,

reflecting a need to train clinicians in the environment in which they will eventually work (O’Malley et al., 2015).

At the core of primary care team culture is care delivery in the context of personal relationships organized with a purpose to meet the needs of individuals and their families and provide comprehensive, coordinated, and continuous connection toward improving health. Good relationships provide the foundation for high-functioning teams and are critical to providing high-quality care (Gittell, 2008). Establishing effective primary care teams requires explicit emphasis on team design that has a structure, a relational and functional culture, and a design optimized with the care-seeker and community to deliver high-quality primary care.

MEMBERS OF THE PRIMARY CARE TEAM

The care-seeker and family are active and engaged members of the primary care team with a central and invaluable role to play in the assessment, treatment, and implementation stages of the process. Likewise, clinicians are expected to provide care that is person centered and includes listening to, informing, and involving people (IOM, 2001). Person-centered care is the practice of caring for people and their families in ways that are meaningful and valuable to the individual.

The following sections provide an overview of the core, extended health care, and extended community care teams. Each section highlights select team members and describes their roles and contributions on the interprofessional team. The list is by no means exhaustive; it highlights the value that others can bring to an interprofessional primary care team. The level designations the committee makes are not the same in all situations. For example, a community health worker (CHW) or pharmacist may be considered part of the core in many settings.

The Core Team

The core team comprises the patient, their family, and various informal caregivers; primary care clinicians, who may be physicians, PAs, NPs, or RNs; and clinical support staff, such as medical assistants and office staff.

Patients, Family Members, and Caregivers

As noted above, person-centered care requires that patients, their family members, and informal caregivers be considered core members of the primary care team. Honoring the care-seeker’s voice is essential to ensure that the care meets the needs and goals for that person and their family. Listening to and incorporating that voice in the delivery and governance of

primary care has become a national priority (Bombard et al., 2018; IOM, 2013a). Yet, in practice, decisions about the design, delivery, and governance of primary care are still often made without the input of those who are intended to benefit. This gap is even greater for disadvantaged patients, whose opinions, needs, and preferences may not be valued because of institutional discrimination, limited health literacy, or mistrust.

If fortunate, the patient is surrounded by friends and family members who may, depending on the circumstances, function as informal caregivers and should be included on the primary care team. For children and adolescents, the family is a central element of the care team. Likewise, adults may involve their children or other family members in their care.

The United States has no standard definition for informal caregivers, though typically these are friends and family members who provide support with activities of daily living, medication management, and care coordination. These individuals, while not formally trained or certified, have an intimate knowledge of the patient’s background, history, usual state of function, and life circumstances. They are invaluable members of the team because they are crucial to shared decision making with the patient and interprofessional primary care team and can work together to identify and reach shared goals (Park and Cho, 2018; Wyatt et al., 2015). This is particularly important for fulfilling shared goals and care plans for children, adolescents, and adults with complex medical needs (Kuo and Houtrow, 2016). In general, family and other informal caregivers have far more daily contact with the patient than any other member of the health care team and are often an underused authority for supporting self-management and recovery (Andrades et al., 2013; Cené et al., 2015; IOM, 2008; Rosland et al., 2011; Whitehead et al., 2018). Experts recommend that formal health care teams help them to understand the tasks of informal care, assess their capacity, and train and monitor caregivers’ performance (Friedman and Tong, 2020; Reinhard et al., 2008).

Estimates suggest that some 53 million Americans care for an ailing or aging loved one, typically without pay (AARP and NAC, 2020). Historically, most informal caregiving was unpaid, but in recent years, several states have created payment programs (Polivka, 2001). The VA also has an assistance program in which eligible caregivers are provided a monthly stipend (VA, 2020).

Primary Care Clinicians

The core team of primary care clinicians generally includes physicians, NPs, and PAs. Today, four major trends are strongly influencing the practice and expansion of interprofessional primary care teams: (1) a widening

income gap between primary care and medical subspecialties, (2) pressure to increase efficiencies rather than effectiveness of primary care, (3) general under-resourcing of primary care teams, and (4) scope of practice. Physician practice in primary care in the United States is not the province of one group or specialty but rather includes family medicine, general internal medicine, general pediatrics, geriatrics, and others depending on the definition, each having its own certifying board and professional organization (AAMC, 2019; Jabbarpour et al., 2019). This complexity requires high levels of coordination for each to advocate effectively for primary care—something missing from primary care today. The income gap between primary care and specialties is associated with a declining choice of primary care by physicians in training (COGME, 2010; Phillips et al., 2009; Weida et al., 2010) (see Chapter 9 for more details) and with a growing number of these professionals who do enter primary care leaving it or choosing more lucrative opportunities, such as becoming hospitalists or creating niche practices, such as pain clinics or sleep medicine (Cassel and Reuben, 2011; Miller et al., 2017). The dominant fee-for-service model makes patient throughput volume and minimizing overhead the main drivers of primary care efficiency, typically at the expense of its effectiveness (Phillips et al., 2014), leading to reduction in primary care comprehensiveness, one of its highest value functions. It is also associated with one of the highest rates of burnout among physician specialties (Berg, 2020). The result is an eroding and maldistributed primary care workforce (Basu et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2013a; Petterson et al., 2012).

As noted in Chapter 3, NPs and PAs play an important and growing role in the overall primary care workforce, and graduates from NP primary care programs have shown steady growth in the past decade (AANP, 2020b). Within the primary care team, the role of NPs and PAs may vary state to state as a result of differences in state licensure laws. In 23 states and the District of Columbia NPs can practice without physician supervision; other states require such supervision and have other restrictions limiting NPs’ scope of practice (AANP, 2021). In 2016 the VA amended its medical regulations to permit full practice authority for NPs2 when they are acting within the scope of their VA employment regardless of the location of the VA facility (VA, 2016). There has been less of a push for independent practice among PAs, and 37 states allow the supervising physician and PA at the practice level to determine the scope of practice and establish it through a written agreement between the two (AAFP, 2019). State-to-state variation in scope of practice prevents a unified approach to team-based primary care and creates confusion for patients and families. During the

___________________

2 This ruling also applied to nurse specialists and nurse-midwives.

COVID-19 crisis multiple states quickly passed legislation to broaden the scope of NP and PA practice, including broadening their authority or changing supervisory requirements to build clinician capacity to address the surge of care-seekers (AAPA, 2020; Lai et al., 2020).

The resistance to increasing the scope of practice of any members of the core primary care team seems antithetical to the need to increase the number of primary care clinicians to expand access to care, particularly in underserved regions (Bruner, 2016; Buerhaus, 2018; Cawley and Hooker, 2013; Neff et al., 2018; Ortiz et al., 2018; Xue et al., 2018b). Assessing Progress on the Institute of Medicine Report The Future of Nursing captured this well, saying, “in new collaborative models of practice, it is imperative that all health professionals practice to the full extent of their education and training to optimize the efficiency and quality of services for patients” (NASEM, 2016, p. 48).

While all types of clinicians in the core team often have overlapping roles in care delivery, they each offer unique skills that address different needs. Interprofessional team–based care delivery, supported by compatible payment models, would allow practices to fully use the unique contributions these professionals can make to high-quality patient care. Similarly, allowing NPs and PAs to practice at the top of their licensure would also help facilitate team-based care, alleviate some of the burden on physicians, and improve access to services (IOM, 2011b; NASEM, 2016, 2019b). The solutions recommended by this report would help all three see it as a viable, meaningful career and should be a source of common cause.

Registered Nurses

Nurses have a range of competencies that, if used appropriately, could distribute responsibilities more efficiently in primary care. Nurses in primary care, which has emerged as a distinct professional nursing specialty (Borgès Da Silva et al., 2018; Mastal, 2010; Swan and Haas, 2011), are engaged in clinical responsibilities, such as assessing someone’s problems or concerns, planning their care with their families, coordinating care, and evaluating outcomes of the care. Nurses can advocate for patients and their families and offer referrals to optimal health services. Studies have shown that involving nurses in coordinating primary care results in improved patient satisfaction (Borgès Da Silva et al., 2018). Many nurses in primary care deliver health education services to patients and their families, perform procedures that require a professional license (such as administering vaccines), and consult with professional colleagues. Nurses often have key insights into workflow and integration of the care team, often acting in roles focused on staffing workload regulatory issues and quality improvement.

Medical Assistants and Office Managers

Medical assistants are essential staff in primary care and one of the fastest-growing sectors in that workforce (BLS, 2020). Typically, medical assistants are assigned to a partnering clinician and can develop long-term relationships with care-seekers and families. They are often an early point of contact and have familiarized themselves with the patients’ personal and medical histories. Their role focuses on preparing patients for visits, helping them flow through the clinic, and ensuring that their primary care clinician has the information and resources needed for a whole-person visit. Experience and evidence have shown that medical assistants are often capable of doing much more. Most medical assistants are adept at using the electronic health record (EHR), and research has shown that with training, they can effectively engage in preventive care tasks, coach care-seekers, and manage population health strategies (Naughton et al., 2013). One caveat to the expanded use of medical assistants is that they have high rates of turnover; it can exceed 50 percent per year as a result of burnout and low satisfaction with compensation and opportunities for growth (Friedman and Neutze, 2020; Skillman et al., 2020).

The office manager is also a valuable member of the primary care team, often serving as the first point of contact for care-seekers and their families. Office managers are responsible for a diverse range of functions, including handling routine financial transactions and reimbursements, ordering supplies, scheduling, coordinating office functions, providing general administrative support, and maintaining records and supporting documents (Sachs Hills, 2004).

The Extended Health Care Team

The extended health care team has emerged in primary care delivery to augment the core team’s ability to meet the growing needs and complexity of individuals and the local community (Bodenheimer, 2019a). Depending on need, members of this team can include CHWs, pharmacists, dentists, social workers, behavioral health specialists, lactation consultants, nutritionists, and physical and occupational therapists, who may support several core teams (Bodenheimer and Laing, 2007; Mitchell et al., 2019).

Depending on many factors, including the needs of the individual and family and the availability and accessibility of team members, extended care team members may be integrated fully into the core team. The extended care team will look quite different depending on whether the person seeking care is a child, adolescent, adult, older adult, or someone with complex medical needs. In fact, the composition of that team will likely change over

the developmental and aging trajectory. For example, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has published standards for pediatric team-based care that calls for pediatric-specific models (Katkin et al., 2017).

Following are examples of members of the extended health care team and their value-added role on the interprofessional team. These examples highlight the need for greater engagement of interprofessional team members, but the list is not comprehensive.

Community Health Workers

CHWs, also called “promotores de salud” and “peer mentors,” are an important and emerging workforce within primary care. They are unique within the health care workforce because they are defined not by their training or functions but rather by their identity. CHWs are individuals who share a common sociocultural background and life experiences with the people they serve, and as their name implies, they come from the community in which they serve (Chernoff and Cueva, 2017; Farrar et al., 2011; IOM, 1983; Palazuelos et al., 2018). As a result, they understand the environment and the community and family contexts that affect the person seeking care.

CHWs often come from and serve disadvantaged populations, and they earn their expertise by virtue of challenging life experiences, such as facing discrimination, living with financial hardship, surviving trauma, having a child with complex medical conditions, or even simply being a parent. The combination of lived expertise and altruism, coupled with appropriate training and work practices, enables CHWs to establish trust, provide nonjudgmental support, and offer practical guidance for a range of social, behavioral, economic, and preventive health needs. Their role can include finding social supports; providing health system navigation, health coaching, and advocacy; and connecting individuals to essential resources, such as food, housing, or medications. A growing body of evidence (CDC, 2014) supports their effectiveness to address underlying socioeconomic determinants of health (Wang et al., 2012); improve chronic disease control (Carrasquillo et al., 2017); promote healthy behavior (Minkovitz et al., 2007); improve access to care (O’Brien et al., 2010); increase use of preventive care services; foster healthy development (Mendelsohn et al., 2005); reduce costly hospitalizations (Campbell et al., 2015), readmission (Kangovi et al., 2014), and ED use (Coker et al., 2016); and save Medicaid as much as $4,200 per beneficiary (Kangovi et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated the role that CHWs play in responding to the needs of the community in which they reside, particularly in addressing the social determinants of health (SDOH) that have been shown to increase the risk of COVID-19 infection (Peretz et al., 2020). In

New York City, for example, health care organizations incorporated CHWs into their interprofessional response to COVID-19. In collaboration with community-based organizations, CHW teams proactively contacted socially isolated patients, connecting them with sources of critically important care and support during the pandemic.

The core challenges for integrating CHWs into primary care relate to quality and financing (Kangovi et al., 2015; WHO, 2018). CHW programs vary in their structure and effectiveness. However, effective programs often share specific program elements that include hiring guidelines, compensation, structured supervision, manageable caseloads, community and clinical integration, and a holistic approach to support (Kangovi et al., 2015). CHWs are paid through a complex patchwork of funding options, such as Medicaid demonstration waivers, health homes, Medicaid managed care plans, and grants (Lloyd et al., 2020).

Behavioral Health Specialists

The U.S. primary care system faces a growing challenge in delivering mental health services to populations it serves (NASEM, 2020). Rates of mental health conditions are rising, fueled in part by increasing rates in children and adolescents, the opioid epidemic, and the COVID-19 pandemic (Beck et al., 2018; Holingue et al., 2020; The Larry A. Green Center and PCC, 2020). The behavioral health workforce includes all providers of prevention and treatment services for mental health or substance abuse disorders, including licensed and certified professionals, case coordinators, and peer advisors.

Behavioral health and mental health specialists working in primary care provide a range of education, consultation, and evidence-based interventions when the team determines that this is needed to improve patient function and achieve identified health goals (Skillman et al., 2016). More specifically, both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy can be added to the care plan with clear evidence-based protocols for both mental health conditions and chronic medical conditions. An integral part of the role of these team members is ongoing education, training, and consultation with medical team members to increase their comfort and confidence in identifying, treating, and managing comorbid mental and physical conditions and addressing a complexity approach to follow-up and team management to ensure continuity and engagement.

A significant barrier for incorporating behavioral health into primary care is the growing shortage of behavioral health workers; the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) projects 250,000 fewer than will be needed by 2025 (HRSA, 2015). Funding is also an ongoing barrier to using and optimizing behavioral and mental health services in primary

care, as lack of insurance coverage and out-of-pocket costs for mental health services are often barriers to care-seekers and their families (Cheney et al., 2018; Cook et al., 2017; Rowan et al., 2013).

A further barrier to integrating behavioral health into primary care is a lack of strategies to develop effective and sustainable models for integration (McDaniel et al., 2014). The VA has evaluated the extent of its success in integrating behavioral health into its primary care model and reported that primary care practices serving smaller populations experienced challenges in providing these services (Cornwell et al., 2018). The challenges of creating effective care models in which behavioral health services are part of the extended primary care team have been described, emphasizing the need to integrate them into interprofessional training and educational curricula (NASEM, 2020; Ramanuj et al., 2019).

Pharmacists

Pharmacists working in primary care assume responsibility as members of the interprofessional care team to optimize medication therapy to ensure that it is safe, effective, affordable, and convenient (PCPCC, 2012; Ramalho de Oliveira et al., 2010). With the increasing prevalence of chronic disease and the resultant use of more medications, helping individuals and the health care team manage medication complexities is essential (Buttorff and Bauman, 2017; Qato et al., 2008). Fragmented care may increase the risk of medication mismanagement, as prescribing happens across many care settings and the lack of interoperability of EHRs further limits the accuracy of medication lists. Illness and death resulting from non-optimized medication therapy led to an estimated 275,000 avoidable deaths in 2016, with a cost of nearly $528.4 billion (Watanabe et al., 2018).

Pharmacist expertise is critical in guiding the team, person, and family in effectively assessing, planning, and managing medication use. The pharmacist works with them to develop an individualized plan that achieves the intended goals of therapy with appropriate follow-up to ensure optimal medication use and outcomes (CMM in Primary Care Research Team, 2018). Pharmacists can also collaborate as members of interprofessional primary care teams to deliver preventive care and chronic disease management in a variety of models, including as embedded practitioners in a primary care practice, through collaborative relationships between medical and community pharmacy practices, or via telehealth.

Research has shown that pharmacists contribute positively to the health of people and communities by delivering services aimed at improving medication use, with impact noticed across all areas of the quadruple aim (McFarland and Buck, 2020; PCPCC, 2012). Pharmacists have also been shown

to aid in meeting the public health needs of individuals and communities by providing access to needed point-of-care testing, vaccinations, and essential medications (Berenbrok et al., 2020; Newman et al., 2020).

The greatest challenge to integrating the role of the pharmacist in primary care relates to financing barriers, with payment for clinical pharmacy services not systematically covered by Medicare and Medicaid and payment strategies varying widely state to state. Increasingly, health plans and clinical organizations engaged in risk-based contracting are recognizing pharmacists’ important contributions to chronic care management through direct payment strategies or inclusion in value-based payment arrangements (Cothran et al., 2019; Cowart and Olson, 2019; Patwardhan et al., 2012). Expanding awareness of the beneficial effects of integrating pharmacists into primary care teams on clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes is needed to support the scale and sustainability of the positive collaborations emerging nationwide.

Dental Professionals

Oral health is an essential component of overall health and well-being. Unfortunately, preventable oral diseases, including caries and periodontal disease, remain widespread, affecting overall physical and mental health as well as quality of life for many Americans and disproportionately impacting disadvantaged populations including homeless or incarcerated individuals, persons with disabilities, and Indigenous communities (Peres et al., 2019). When chronic dental conditions are effectively managed with early intervention, health outcomes improve and overall health care costs fall (Cigna, 2016; Jeffcoat et al., 2014; Nasseh et al., 2017; Watt et al., 2019), yet access to affordable dental services continues to be a major concern for many.

Opportunities to improve access to oral health services within primary care settings can benefit people of all ages. Primary care services see children multiple times through the first 5 years of life and thus have an opportunity to provide health promotion messages, screen for early childhood caries, and apply preventive fluoride varnish for high-risk children, in accordance with the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommendations (Moyer, 2014) and AAP best practices (Clark et al., 2020). Likewise, primary care teams can conduct oral cancer screening and refer patients with chronic oral conditions to dental offices.

Integrated models of primary care and dentistry can increase access and improve care coordination (Atchison et al., 2018; NASEM, 2019a). In recent years, HRSA has helped health centers tackle limitations in providing dental services, such as outdated equipment and insufficient space, to improve access to integrated, oral health services in primary care settings (HHS, 2019). In 2018, HRSA-funded health centers served more than 6.4

million patients seeking dental care—an increase of 13 percent since 2016—and provided more than 16.5 million with dental visits. In other settings, however, dental care remains almost entirely siloed from the rest of medical care, in both training and practice (see Chapter 5 for more detail). Payment for dental care is also treated separately, and Medicaid and Medicare spend very little on dental services for adults. Children are entitled to dental coverage through Medicaid, though only a small portion of eligible children are enrolled (Hummel et al., 2015; Simon, 2016). Most dental care in the United States is paid for out of pocket, compared to total health spending, with low-income adults facing the most barriers to obtaining it (Vujicic et al., 2016). As with other extended team members, the lack of coverage for dental service limits full integration of dental services in primary care teams. Payment models that support interprofessional, team-based, preventive care could eliminate this as a barrier (Atchison and Weintraub, 2017; Atchison et al., 2018; Hummel et al., 2015; Nasseh et al., 2014; Watt et al., 2019).

Social Workers

In the primary care setting, social workers may be responsible for assessing and screening patients, engaging and understanding them in their social context, providing behavioral health interventions, helping them and their families navigate the health care system, coordinating care across settings, and connecting clients with resources to address food insecurity, transportation, and other factors that affect SDOH (Cornell et al., 2020). They enable individuals with complex needs to live safely in their communities with effective yet realistic care plans, communication, and support. Although social workers’ role in primary care is increasing, many primary care practices do not take advantage of their special training, particularly when working with populations of Black, Indigenous, and people of color and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Given that including social workers in primary care settings improves health outcomes (Cornell et al., 2020; Rehner et al., 2017), the percentage of primary care practices who report working with social workers may increase as public and private payers shift toward value-based payment models that emphasize addressing SDOH.

Other Extended Health Care Team Members

In addition to those described above, many other health care professionals may be part of the extended team and contribute value-added care and services to meet the needs of the person seeking care. Others include care coordinators, care managers, home health care nurses, lactation consultants, nutritionists, and therapists (e.g., physical, occupational).

In addition, the primary care team often collaborates with other critically important medical colleagues and specialists, including psychiatrists, cardiologists, endocrinologists, hospitalists, and integrative medicine specialists. For patients with complex needs, coordinating within this wider team is a significant task for the core team.

The Extended Community Care Team

An essential component of the interprofessional primary care team is the extended community care team, which includes organizations and groups, such as early childhood educators, social support services, healthy aging services, caregiving services, home health aides, places of worship and other ministries, and disability support services. This brings together the community organizations, services, and personnel who are dedicated to ensuring that health care teams, care-seekers, and communities have access to the support services and resources needed to ensure the health and wellness of people and communities. Like the extended care team, the extended community care team will vary with the size and the type of the primary care practice and the needs of the population and the local community, and it should be constantly monitored for clinical fit (Katkin et al., 2017).

Team Size

The size and composition of a primary care team depends on the alignment of several key factors: the complexity and severity of the health and social concerns of the population and community to be served; the availability and accessibility of health professionals and community support networks; and the robust institutional data structures used to efficiently and effectively match, allocate, and monitor resource supply with individual, family, and community needs. Randomly allocated small teams and unwieldy large teams that lack clear, matched, and organized workflows monitored by operational leaders risk failure to optimize and deliver the whole-person benefit of primary care despite the level of population complexity. When primary care teams are poorly defined and resourced, they risk depersonalization, lack of relationship continuity, ongoing communication gaps, and failure to engage meaningfully with people and their families, with their unique individual goals, values, and desired outcomes.

A 2018 study modeled team configurations (and the cost per person) required to deliver high-quality primary care to different adult populations (Meyers et al., 2018). Using a combination of practice-level data from 73 practices and 8 site visits, the authors determined that to deliver high-quality primary care to 10,000 adults, a primary care practice needed about 37 full-time team members, including 6 physicians and 2 NPs or PAs, supported

by a mix of nurses, medical assistants, and RNs and licensed clinical social workers to help manage those with more complex chronic needs. Other team members, such as a pharmacist, care coordinator, and office staff, were also included. For a 10,000-person panel with a larger proportion of geriatric individuals, the authors modeled a larger team with about 52 members, more devoted to complex care management. For a 10,000-person panel with high social needs, the team included about 50 members but relatively fewer physicians compared to the other models and with additional members, such as CHWs, behavioral health, and other social supports. The authors’ model for a smaller, rural panel of 5,000 included about 22 full-time team members, including a CHW (Meyers et al., 2018).

One method of determining team size is empanelment. As described in Chapter 4, this involves identifying the people in the target population, assigning all individuals in a given population to a primary care team or team member, and reviewing and updating the panel continuously (Bearden et al., 2019; McGough et al., 2018). This allows the clinicians and staff of that team to determine the optimal team size given the panel size and its needs.

Systems of care empanel populations in a variety of ways. In Alaska, for example, the Southcentral Foundation (SCF) Nuka System of Care’s panels include around 1,500 patients per care team who empanel voluntarily. SCF approaches the task of empanelment with an entire department devoted to checking empanelment status, guiding the transition and information flow for those who switch, and providing other support to the process (Gottlieb, 2013; PHCPI, 2019). Costa Rica takes a different approach, geographically empaneling all citizens to integrated health care teams that each care for around 4,500 patients (Pesec et al., 2017). In a more hybrid approach, Turkish primary care clinicians empanel geographically to ensure universal access but allow empaneled people to switch clinicians after enrollment (PHCPI, 2019).

The literature describes several methods to determine optimal panel size, including a formulaic approach to balancing appointment supply and demand, a time-based method that accounts for the work required to deliver comprehensive care, and using existing panel sizes to construct normative benchmarks (Kivlahan et al., 2017). Panel sizes vary considerably, with many practices unable to provide accurate estimates, but the consensus is that the old, arbitrary standard of 2,500 patients per physician is too large for a single physician to manage effectively in most situations (Raffoul et al., 2016). Even for an interprofessional team, optimal panel size is often below 2,000 and depends on the degree of task-sharing, organized workflow, and matched skill sets of the team members (Altschuler et al., 2012; Brownlee and Van Borkulo, 2013). For example, the VA established panel

sizes in 2009 of 1,200 veterans to a full-time physician’s panel3 and adjusts based on location (VHA, 2017). In general, panel sizes for pediatricians are smaller than for primary care practices serving mostly adults because children under 4 years old visit primary care more frequently in a typical year than adults do (Murray et al., 2007).

Multiple methods exist to determine panel populations if they are not based on strict geography. These usually include variations in classifying active care-seekers, as the priority is to keep people with their normal clinician or team, if they have one. That variation includes how far back a health system looks in appointment history to find active accounts and how many and which types of appointments to qualify as active (AIR, 2013). An additional layer, risk adjustment (see Chapter 9), is another important element of empaneling. Practices may account for characteristics including sex, age, comorbidities, acuity, or other traits based on EHRs, claims, or population health data to attempt to evenly distribute a population’s health needs across different panels (Brownlee and Van Borkulo, 2013; Kivlahan and Sinsky, 2018).

In addition to strategies to evenly distribute people, health systems or practices will often stratify populations into subgroups, based on specific criteria, to better align and match needs with team resources (Bohmer, 2011). For example, this process may stratify those who would benefit most from interaction with an integrated, behavioral specialist who may only be onsite twice per week or people with multiple medical and medication complexities who require longer visits with key team members (Bohmer, 2011).

EDUCATING AND TRAINING THE INTERPROFESSIONAL PRIMARY CARE TEAM

Chapter 3 touched briefly on the pipeline problems for primary care workforce production. This section expands on the major factors influencing the education of that workforce and how it needs to change to prepare the workforce for integrated, interprofessional care. Core to the delivery of primary care are competencies underlying team-based care; how to function in an integrated, interprofessional manner; and how to integrate and coordinate care with community-based care team members. To ensure equitable access to primary care, it is necessary to determine the size of the workforce needed along with the types of team members needed in different communities.

___________________

3 Literature typically measures panel size per physician, even in interprofessional team-based care settings. For example, the VA staffs one physician and three supporting team members to a panel. It assigns discipline-specific team members, such as dietitians and social workers, across multiple panels.

Over the past decade, the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the World Health Organization, the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, and others have issued repeated recommendations for interprofessional education (Cox and Naylor, 2013; Frenk et al., 2010; IOM, 2013b; NASEM, 2016; WHO, 2010). In 2009, major nursing, medicine, pharmacy, dental, and public health organizations founded the Interprofessional Education Collaborative, and over the next 5 years, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) partnered with the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, the American Board of Medical Specialties, and the American Psychiatric Association to create resources for early interprofessional training and lifelong learning (IPEC, 2020; Swanberg, 2016). Progress has been made, in that most health care disciplines now have interprofessional competencies as an expectation for all their graduates (HPAC, 2019), and some leading institutions integrate these competencies into their initiatives. For example, the VA Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education focus on developing and implementing models for interprofessional team-based learning and practice in training settings (Harada et al., 2018), while the American College of Physicians created a standing committee to advise on “plans and strategies to promote high-quality education incorporating interprofessional, interdisciplinary, and patient perspectives and promoting partnership with all members of the health care team” (ACP, 2020).

Interprofessional practice has four major established core competencies—values and ethics for interprofessional practice, roles and responsibilities, interprofessional communication, and teams and teamwork (Schmitt et al., 2011)—and the challenge of achieving those competencies lies in incorporating interprofessional didactic and experiential learning into the already crowded medical and health professional education. Challenges also exist in educating and training students alongside the current workforce, especially in settings where the workforce itself is not functioning as an interprofessional team. Interprofessional education competencies are location agnostic, so there is no guarantee that aspiring primary care–bound health professionals, as well as the existing primary care workforce, have any interprofessional education or training specific to the delivery of primary care.

Integrating interprofessional education and training in primary care is also a challenge because crowded clinics often find that accommodating single students from one discipline is disruptive to the normal workflow. This situation makes it almost impossible to accommodate students from different disciplines rotating together for an interprofessional education practicum. It is much easier to train across professions in the contained environment of academic health centers and on large inpatient units, where teams frequently work side by side, than in multiple primary care clinics that are unlikely to be set up for robust team-based care models. For interprofessional education to take root in primary care, the training and

care models need to evolve together, and this will take considerably more investment than is currently available (Sanchez and Hermis, 2019; Shrader et al., 2018). Indeed, changes in the funding model for training clinicians in primary care are necessary before primary care practices can engage in interprofessional educational experiences without believing that educating trainees in team-based care will reduce the productivity of the individual clinician.

Too often, students engage in didactic work that introduces them to interprofessional teams, roles, and mutual respect, followed by clinical training in settings that are not interprofessional and lack teamwork, collaboration, and community engagement. Research over the past 40 years on how people learn shows that what learners do is critical to learning and more important than what they are told (NRC, 2005; Sawyer, 2005). The implication is that while primary care–bound students, and perhaps all health profession students, are acquiring their disciplinary knowledge and skills, their curriculum should simultaneously be embedded in environments in which they can experience and progressively engage in high-quality team care (Billett, 2004; Lave and Wenger, 1991; Peterson, 2019; Swanwick, 2005).

DIVERSITY AND EQUITY IN THE PRIMARY CARE WORKFORCE

Research shows that increasing the diversity of the workforce to more closely match the increasing diversity of the United States is essential for “(1) advancing cultural competency, (2) increasing access to high-quality health care services, (3) strengthening the medical research agenda, and (4) ensuring optimal management of the health care system” (Cohen et al., 2002, p. 91). Having a diverse health care workforce that reflects the population has been shown to improve health equity and reduce health care disparities, increase access to care, improve health care outcomes, strengthen patient communication, and heighten patient satisfaction in underserved and minority populations (COGME, 2016; Cohen et al., 2002; Cooper and Powe, 2004; HRSA, 2006; Poma, 2017; Wakefield, 2014).

The Diversity of the Primary Care Workforce

Health profession education is a common good, so programs should be expected to supply graduates prepared to care for their immediate and regional communities. To the extent that they fail to do this, they are failing their public mission. Health disparities are a long-standing, well-recognized problem in the United States, perpetuated in part by a health care workforce that does not come from, represent, or commit to the populations it purports to serve.

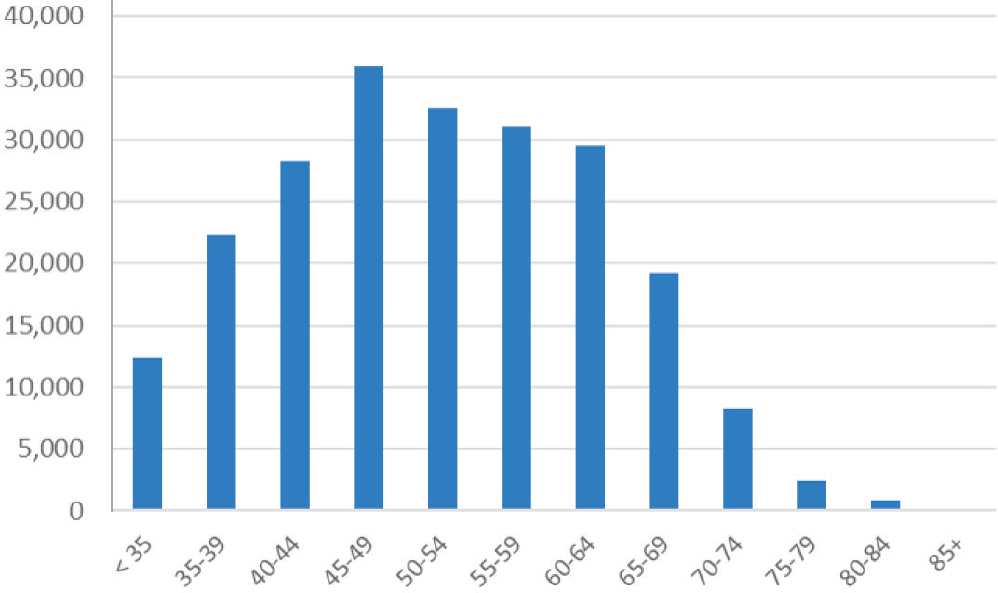

In 2017, men accounted for 55 percent of the total PCP workforce, though that percentage varied widely by discipline. Women were 52 percent of the geriatricians and 64 percent of the pediatricians, while men were 59 percent of the family practitioners, 62 percent of internists, and 75 percent of general practitioners (Petterson et al., 2018). In 2017, more than 25 percent of PCPs were 60 years and older (see Figure 6-2).

A 2017 HRSA report revealed that white workers represent the majority of all 30 health occupations studied and are overrepresented in 23 of the 30 occupations based on their total representation in the U.S. workforce (HRSA, 2017). In comparison, Hispanic, Native Hawaiians, and Other Pacific Islander professionals are significantly under-represented in all the occupations classified as “health diagnosing and treating practitioners,” while non-Hispanic Black individuals are under-represented in all of these occupations, except among dieticians and nutritionists (15.0 percent) and respiratory therapists (12.8 percent). American Indians and Alaska Natives are under-represented in all occupations except for PAs and have the lowest representation among physicians and dentists (0.1 percent in each occupation). Asian professionals are well represented as “health diagnosing and treating practitioners” but under-represented among speech–language pathologists (2.2 percent) and advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) (4.1 percent). Data for allopathic training programs for primary care specialties show a similar story. Among internal medicine residents in 2020, 4.7 percent were Black and 6.7 percent were Hispanic. Among family medicine

SOURCE: Petterson et al., 2018.

residents, 9.3 percent were Black and 10.0 percent were Hispanic. American Indians and Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders are also under-represented and are at or below 1 percent of the total resident population (AAMC, 2020). Black, Indigenous, and people of color are well represented among health care support and personal care and services occupations, whereas whites are under-represented in these. This is a reflection of the systemic discrimination and biases evident in education, housing, finance, and job opportunities that funnel minorities to health care support and personal care service roles as opposed to health diagnosing and treating roles. Approaches such as holistic admissions practices benefit racial, socioeconomic, and perspective diversity of health professions schools, but the work to improve representation in health care extends far beyond admissions processes (Urban Universities for Health, 2014).

AAMC has released two major reports focusing on diversity and equity in the shrinking PCP workforce—Altering the Course: Black Males in Medicine (2015) and Reshaping the Journey: American Indians and Alaska Natives in Medicine (2018)—to explore and try to answer why diversity efforts have not been more successful in recruiting individuals from under-represented populations. A theme expressed throughout Altering the Course was the persistent, structural racism and stereotyping facing Black men and boys that leads to widespread implicit and explicit bias, which can then create exclusionary environments resulting in de facto segregation (AAMC, 2015). For those Black medical students who do make it into the training pipeline, many have cited racial discrimination and prejudice, feelings of isolation, and different cultural expectations as negatively affecting their medical school experience (Dyrbye et al., 2007; Silver et al., 2019). Furthermore, research has documented that minority physicians often confront racism and bias from not only their peers and superiors but also the people and communities they have committed to serve (Acosta and Ackerman-Barger, 2017). What is not clear and needs more study is the number of PCPs from under-represented populations, including Black, Indigenous, and people of color, who leave the field each year, the reasons they may choose to leave (i.e., burnout, discrimination, specialty practice, age), and what impact that may have on the ability of the workforce to achieve health equity and reduce health care disparities.

Although educating and training a more diverse workforce is critical, the education pipeline is complex and lengthy, and the need for more robust community engagement is urgent and cannot wait for a new, diverse generation of clinicians to make their way through that pipeline. One way many communities are bridging this gap is to expand and diversify opportunities for CHWs, care coordinators, health coaches, and health educators (Brownstein et al., 2011; Jackson and Gracia, 2014). For example, CHWs are a diverse reflection of disadvantaged Americans: 65 percent are Black or

Hispanic, 23 percent are white, 10 percent are American Indian or Alaska Native, and 2 percent are Asian or Pacific Islander (Arizona Prevention Research Center, 2015). While CHWs can improve the diversity of the extended primary care team, that should not deter the necessary efforts to diversify the core primary care workforce across professions to create a local workforce that reflects the diversity of the community in which it is practicing, which can lead to a more equitable system for all (Cohen et al., 2002).

Preparing the Diverse Workforce of the Future

Preparing the workforce of the future starts with the characteristics of the students planning to enter primary care. Evidence exists that health profession students who come from underserved communities, whether rural, urban, minority, or other, are far more likely than middle-class white students to work in underserved areas (Cregler et al., 1997; Goodfellow et al., 2016). While recognizing that health profession education programs have diverse missions, such as community health care, training academic leaders, and providing research skills and opportunities, all health profession programs must invest in the common good. If program admission goals and outcomes were public, it would add transparency and accountability that could enable the country to make progress toward eliminating health disparities.

Once programs select appropriate, demographically diverse, primary care–bound health profession students, these programs will have to support their students’ values and career goals, which often does not happen. In fact, bright students may be told they are too smart to become primary care clinicians (Marchand and Peckham, 2017; Warm and Goetz, 2013), much like NP students are often asked why, if they are so smart, they do not become doctors. Health professional training programs must ensure that learners do not receive this kind of undermining message and, if they do, they have resources for support and to assist them and their allies in responding. A significant challenge is that many programs, especially research-intensive programs, are not committed to primary care and have different goals for their learners (Bailey, 2016; Frieden, 2009). Holding educational programs to regionally appropriate outcome goals may be a critical element in advancing these programs’ mission to address health care disparities through workforce interventions.

Bringing the right students on board is only the first step. Institutions must also ensure that the educational experience provides the opportunity to develop the skills that will enable students to form relationships with their future care-seekers. While disciplinary knowledge and technical skills

are critical, the meta-skills of communication, collaboration, leadership, and advocacy are equally essential. In general, health profession students are educated in formal didactic contexts, in a fairly theoretical vein, and in isolation from each other. While theoretical knowledge is important across the health professions, this focus underinvests in the contextual, team-oriented skills that are essential for effective team-based primary care practice. To the extent possible, primary care–bound learners from different disciplines would benefit from learning with each other in classrooms and especially from joint early and sustained experiential learning. In most medical schools, students begin seeing patients in the first or second week of their first year, and they would benefit greatly if these experiences included explicit attention to and work with the full range of members of the primary care interprofessional team.

The ability of a primary care team to address the broad range of population needs, including identifying community expectations, engaging individuals in preventive health care and counseling, and managing simple and moderately complex medical problems, is essential to creating a system in which the requirements of the populations and individuals are addressed efficiently and cost-effectively. Primary care team members should see themselves as the linchpin between communities and link people and families to specialists, acute care hospitals, and chronic care facilities. They need to have a deep grasp of physiology, therapeutics, and technical medicine and also an appreciation of the assets and challenges of the communities they serve, a broad understanding of how the health system is constructed and works, exceptional skills in team-building, communication and collaboration, and oftentimes strong leadership and advocacy skills. The U.S. system of identifying candidates for these roles and preparing learners is often not well designed to accomplish this task.

FUNDING TO SUPPORT THE TRAINING OF THE PRIMARY CARE WORKFORCE

The ability to obtain high-quality primary care depends on the availability of clinicians who are essential members of the primary care core team, including PCPs, NPs, and PAs (Phillips and Bazemore, 2010). Dynamic changes are occurring in the type of primary care clinicians being educated, and access to a robust workforce varies across geographic regions. While the need for the primary care workforce has been well described in this report, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) offers no consistent source of funding that is based on population needs. Additionally, the committee is not aware of federal support for the funding of training non-clinician team members, such as CHWs or medical assistants.

Primary Care Physicians

A substantial body of evidence shows that increasing the proportion of PCPs in the total physician workforce has significant benefits regarding quality of care, access to care, and medical expenditures (Baicker and Chandra, 2004; Basu et al., 2019; Levine et al., 2019; Starfield, 2001; Steinwald, 2008). However, the United States has not seen rapid growth in PCPs over the past three decades (see Chapter 3 for more on the PCP workforce). Current graduate medical education (GME) and Children’s Hospitals Graduate Medical Education (CHGME) funding for physician workforce training results in only 24 percent of trainees pursuing primary care, and fewer than 8 percent go to rural practice (Chen et al., 2013a).4 The IOM has twice recommended that GME policy produce a workforce that is more aligned with population need by increasing the proportion of its funding directed to primary care workforce training (IOM, 1989, 2014). Other federal workforce advisory committees, including the Council on Graduate Medical Education and the Advisory Committee on Training in Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry, have also recommended repeatedly that federal GME funds be directed to increase primary care and rural workforce outputs (COGME, 2010). To date, these evidence-based reports have not resulted in sustained funding directed specifically to primary care.

The root problem may be that the majority of the $15 billion spent on GME by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the VA is paid to hospitals and does not support primary care practices or pediatric services that are the training centers for primary care (Chen et al., 2013b; Weida et al., 2010). Training pediatricians in children’s hospitals is funded under a separate (and precarious) funding stream through the CHGME program (IOM, 2014), administered by the Bureau of Health Workforce, HRSA, and HHS, because GME funding is calculated based largely on the volume of services a hospital provides to Medicare beneficiaries, who are primarily over age 65 and therefore not treated at children’s hospitals (HRSA, 2020a). Despite multiple entities petitioning for more GME and CHGME funding to adequately address the nation’s shortage of physicians, federal support has remained effectively frozen since 1997.

Given the findings that the location of medical students’ schools and training sites affect where they choose to practice (Fagan et al., 2015; Washko et al., 2015), and the shortage of PCPs in rural and other areas, several proposals and policy decisions have aimed to decentralize training (Bennett et al., 2009; Fagan et al., 2015; Whittaker et al., 2019). For example, the University of Toronto established a family medicine residency

___________________

4 Training pediatricians in children’s hospitals has a separate federal funding stream, through the CHGME payment program.

program in Barrie, Ontario, located approximately 60 miles north of Toronto, to address a shortage of physicians in the region. Nearly two-thirds of the graduates from the first six classes of this program stayed to work in the region and were happy with that decision (Whittaker et al., 2019).

Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants

Between 2010 and 2017, the number of full-time NPs in the United States more than doubled, from approximately 91,000 to 190,000, and growth occurred in every region (Auerbach et al., 2020). Similarly, there were about 98,000 PAs in 2007, compared to almost 140,000 in 2019 (He et al., 2009; NCCPA, 2020). NPs and PAs work in multiple settings, including hospitals, physician offices, and clinics, but their rapid growth has transformed many primary care practices. The National Center for Health Workforce Analysis projects that the number of primary care NPs and PAs will outpace demand at the national level if they continue to be used as they are today (HRSA and NCHWA, 2016). In fact, it has been suggested that the growth in non-physician clinicians in primary care could eliminate predicted shortages of physicians (Morgan, 2019; Van Vleet and Paradise, 2015). Current estimates, however, suggest that less than one-third of APRNs spend most of their time in primary care settings (HHS et al., 2020), although separate estimates of NPs only are higher (AANP, 2020b). Among PAs, 25 percent currently practice in primary care, although this number has been decreasing in recent years (NCCPA, 2020). No consistent federal support exists to educate NPs, PAs, and certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), nor do overburdened clinics receive a financial incentive to offer training slots to NP and PA students. The Graduate Nurse Education (GNE) demonstration project, mandated under Section 5509 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA),5 was designed to test whether payments for clinical education increased the number of NP graduates, with the aim of increasing the supply of primary care clinicians to meet growing U.S. demand (IMPAQ International, 2019). From 2012 to 2018, CMS paid five eligible hospital awardees for the reasonable costs attributable to providing qualified clinical education to NP students enrolled as a result of the project. Key findings suggest that the GNE project had a positive impact on NP graduate growth and allowed schools of nursing to enhance and formalize clinical placement processes, strengthen relationships with clinical education sites, and increase awareness of the role and value of NPs (IMPAQ International, 2019). This project was notable in that it was the first large

___________________

5Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 111-148, § 5509 (March 23, 2010).

attempt to broaden the scope of CMS funding beyond physician residency training, though it was discontinued despite positive outcomes.

Practice Settings to Support the Preparation of Primary Care Teams

HRSA has played an important role in investing in the education of the primary care workforce through funding the medical education training programs for physicians, PAs, and behavioral health specialists, and dentistry residency programs in rural and underserved areas. Evidence has shown that these investments through Title VII are producing demonstrably better patient outcomes and that such training increases the primary care workforce, but Title VII funding is only a small fraction of the total GME funding—it has been reduced to less than 10 percent of what it was in the late 1960s (Palmer et al., 2008; Phillips and Turner, 2012)—and the repeated calls to action and modest investments by HRSA have not resulted in significant increases in PCP workforce training.

Federal policies to increase the supply of PCPs in shortage areas, including increasing the funding for health centers, rely largely on HRSA shortage designations that assume the availability of primary care is equivalent to its accessibility (Naylor et al., 2019). In the last decade, the number of health centers has increased almost 80 percent, primarily in urban areas (Chang et al., 2019). Rural health clinics (RHCs), which are not subject to the same requirements of HRSA-funded health centers but are federally certified clinics in rural Medically Underserved Areas or Health Professional Shortage Areas, also provide primary care services. There are currently more than 4,500 RHCs across the country (CMS, 2019). Any growth of health centers or RHCs contributes to increasing health care providers serving in the designated medically underserved areas. From 2003 to 2018, employment in health centers increased from 25,780 to 149,755, including physicians, NPs, PAs, CNMs, and other clinicians (NACHC, 2020; Xue et al., 2018a). RHCs, as a condition of their certification, are required to employ at least one physician and one PA, NP, or CNM (CMS, 2019). An analysis of the impact of health centers on the primary care clinician gap indicated that having a greater number of health center sites was associated with a bigger reduction in the gap in under-resourced areas. However, the increase in primary care clinicians over time has largely been attributed to the use of NPs and PAs and not increasing numbers of PCPs (Xue et al., 2018a). These findings are similar to those reported by the National Association of Community Health Centers that health centers are twice as likely as other primary care practices to employ NPs, PAs, and CNMs. It is not known whether this hiring practice is based on the availability of clinicians in an area or a perceived cost savings, given the difference in the salaries of NPs and PAs compared to physicians.

HRSA has also been instrumental in supporting the training of PCP and dental residents through the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education (THCGME) program. The ACA created the THCGME program in 2010 and it is designed to train health professionals at health centers in underserved communities (Chen et al., 2012). It is the only federally funded GME program to have accountability metrics and reporting requirements and the majority of its trainees stay in primary care and in medically underserved communities (AAFP, 2020). It currently produces more than 280 PCPs and dentists annually (HRSA, 2020b). THCGME is a model of training the primary care workforce where the underserved receive care which has been shown to be an effective way to increase this workforce (Phillips et al., 2013).

HRSA Title VIII programs are also a major source of federal funding for primary care services in underserved areas and have a strong focus on training interprofessional care teams in primary care. Primary care medical and oral health training grants are used to develop and test innovative curricula and training methods to transform health care practice and delivery, in areas such as team-based management of chronic disease in primary care and person-centered models of care. HRSA Title VIII programs are community based, provide interprofessional training programs for all health professionals, and are designed to encourage them to return to community settings after graduation. Title VIII also funds special initiatives that help increase the diversity of the workforce and strategies to improve health care access in underserved areas.

The National Health Service Corps (NHSC), part of Title VIII, has played a significant role in supporting the pipeline of primary care in federally designated shortage areas through scholarships to students in training and paying educational loans for current primary care workers (Politzer et al., 2000). Since its inception, NHSC reports that it has funded more than 63,000 primary care medical, nursing, dental, and mental and behavioral health professionals and that it has more than 16,000 scholarship recipients providing care to more than 17 million people. More than 1,500 NHSC scholars are currently in residency or school preparing to work in underserved primary care settings upon graduation. Evaluations of the program have revealed that NHSC clinicians complement rather than compete with non-NHSC clinicians in primary care and mental health care (Han et al., 2019). NHSC clinicians help enhance care delivery in community health centers, particularly for dental and mental health services, which are the two major areas of service gaps. During the period of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the NHSC workforce increased by 156 percent, with the largest increase seen in the number of mental health clinicians (210 percent) (Pathman and Konrad, 2012).

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

To achieve the goal of high-quality primary care, it is essential that interprofessional teams be designed to meet the needs of individuals, their families, and communities. Teams would benefit from integrating the skills and expertise of the person and their family, primary care clinicians, members of the extended health care team, and community-based personnel and services. When interprofessional teams are used, they are often not optimized, and individual members are often underused and not functioning at the top of their scope of practice. Although evidence exists that integrated, interprofessional, team-based care offers great promise in achieving high-quality primary care outcomes, no standardized or “one-size-fits-all” approach is available to guide the design and composition of interprofessional teams.

Funding for the preparation of the primary care workforce is inconsistent and insufficient. The shrinking physician workforce simply cannot meet the growing needs of high-quality primary care delivery, and the structure of GME funding does not support the training needs of the PCP workforce. Alternative financing sources are needed for community-based training of physicians, NPs, and PAs in primary care. Primary care practices, with high patient volumes and limited time and resources, need financial incentives to support the intensive training of interprofessional primary care teams.

Relatedly, the diversity of the primary care workforce does not match the needs of local communities and society. For primary care teams to address well-documented disparities in treatment based on race and ethnicity, its team members must reflect the lived experiences of the communities they serve. This can be accomplished by increasing the diversity of both the PCP and interprofessional team workforces and matching the needed resources to the populations’ economic, health, and social risks.

Finally, payment has to align with and value interprofessional teams that will vary in design, based on the needs of local communities and patient populations. The current payment system for interprofessional primary care is broken and not aligned to enable the delivery of team-based care. Although significant challenges remain to implementing an integrated, interprofessional workforce that delivers high-quality primary care, the opportunity lies with aligning a payment and financial system that incentivizes and rewards effective, integrated interprofessional primary care that produces positive outcomes.

REFERENCES

AAFP (American Academy of Family Physicians). 2019. Scope of practice—physicians assistants. Leawood, KS: American Academy of Family Physicians.