1

A New Vision for Primary Care

High-quality primary care is the foundation of a robust health care system, and perhaps more importantly, it is the essential element for improving the health of the U.S. population. High-quality primary care is a critical component to achieve the quadruple aim of health care—enhancing patient experience, improving population health, reducing costs, and improving the health care team experience—and it can both make health care more personal and address the inequities that currently plague the U.S. health care system (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014; Christian et al., 2018; Kringos et al., 2013; Macinko et al., 2003; Park et al., 2018; Phillips and Bazemore, 2010; Starfield et al., 2005). Absent access to high-quality primary care, minor health problems can spiral into life-altering chronic disease, chronic disease management becomes difficult and uncoordinated, visits to emergency departments increase, and preventive care lags.

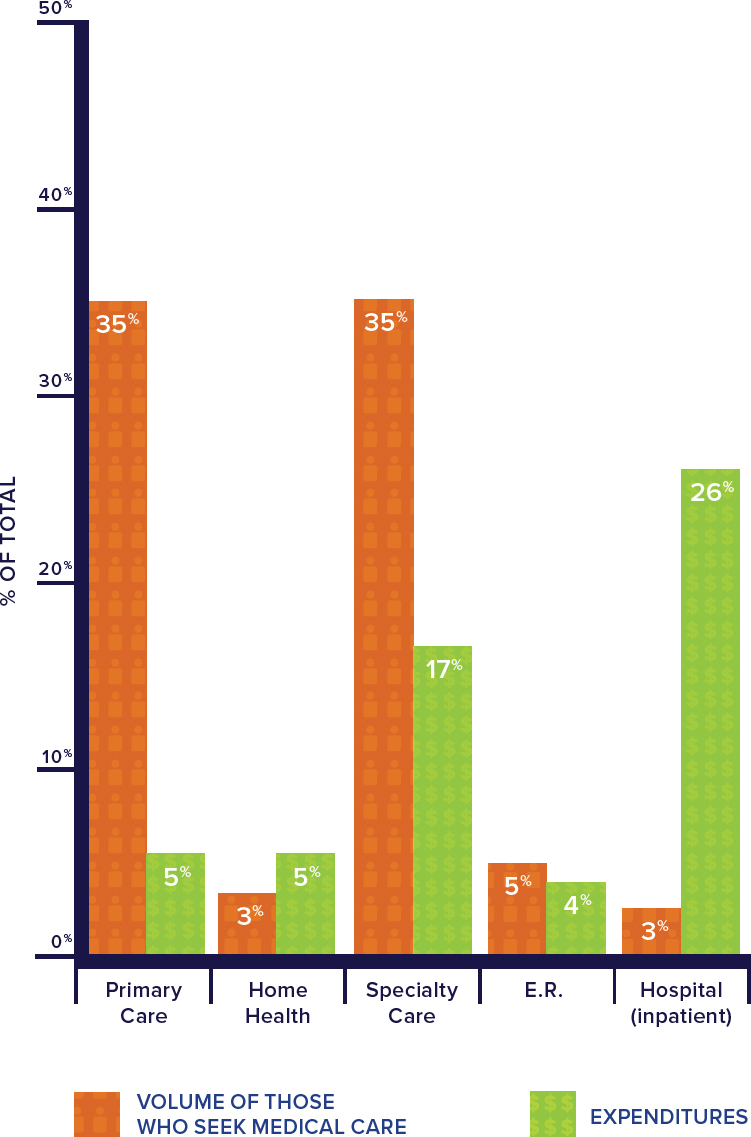

Yet, in large part because of chronic underinvestment, primary care in the United States is slowly dying. Indeed, U.S. investment has fallen short of that needed to make high-quality primary care accessible throughout the nation (Martin et al., 2020; Reiff et al., 2019). Today, more than 35 percent of all health care visits are to primary care physicians (Johansen et al., 2016), yet primary care receives about 5 percent of all health care spending (Martin et al., 2020) (see Figure 1-1) and less than 5 percent of Medicare spending (Reid et al., 2019). Evidence also shows that primary care’s share of total health care spending has decreased in a majority of states (and overall) in recent years (Kempski and Greiner, 2020). In contrast, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries devote an average of 7.8 percent of all health care spending to

NOTES: Visit volume data comes from the 2012 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), while the financing comes from 2016 MEPS data. Expenditures include direct payments for care (insurance payments or out-of-pocket payments). Primary care and specialty care include office-based and outpatient clinics. Primary care data include physicians in family medicine, general practice, geriatrics, general internal medicine, and general pediatrics only. Nurse practitioner, physician assistant, and midwife data were not broken down by setting and are not represented in this figure. Home health includes both formal (i.e., paid) and informal (i.e., unpaid) care. Informal care includes only individuals who live outside the house. All categories are not included in the figure and thus do not add up to 100 percent.

SOURCES: Johansen et al., 2016; Martin et al., 2020.

primary care (OECD, 2019). The upshot of this underinvestment in the United States is a disjointed health care enterprise that creates inequities in care, misallocates resources between primary and specialty care, burns out clinicians, generates financial pressure on primary care practices, limits the relationships that clinicians and patients can develop, produces suboptimal care for too many U.S. residents, has the United States slowly falling behind the rest of the developed world in population health outcomes, and is even beginning to lead to regression in mortality gains of the past 100 years (NRC and IOM, 2013).

On top of these well-documented negative effects of underinvestment, the COVID-19 pandemic amplified pervasive economic, mental health, and social health disparities (Dorn et al., 2020; Smith, 2020) that might have been alleviated if high-quality primary care were ubiquitous nationwide (Baillieu et al., 2019; Basu et al., 2016, 2017; Koller and Khullar, 2017; MedPAC, 2008). The pandemic has also pushed many primary care practices to the brink of insolvency. A May 2020 survey of nearly 3,000 primary care clinicians in all 50 states found that 42 percent of the respondents had laid off or furloughed staff and 51 percent were uncertain about their financial viability over the following month (The Larry A. Green Center and PCC, 2020).

Nevertheless, in the United States, primary care remains the largest platform for continuous, person-centered, relationship-based care that considers the needs and preferences of individuals, families, and communities and whose value is demonstrated with markedly stable usage patterns for more than 50 years (Green et al., 2001; Johansen et al., 2016; White et al., 1961). Regardless of a rapid growth of specialty care, a large percentage of health care visits have consistently taken place in primary care settings. Despite no universally accepted definition of which professions are considered “primary care,” it is generally agreed that they include those practicing in family medicine, general internal medicine, general pediatrics, geriatrics, and other professions that fulfill general health needs. As seen in Figure 1-1, of those who seek medical care in a given month, 35 percent will visit a primary care physician but only 3 percent will be admitted to a hospital (Johansen et al., 2016). Other data sources show that of the 900 million U.S. office visits 2016, more than half were to primary care clinicians (Rui and Okeyode, 2016). In 2018, 76 percent of U.S. adults had a usual source of care; 70 percent of those found it outside of a hospital, usually in an office setting (CDC, 2019).

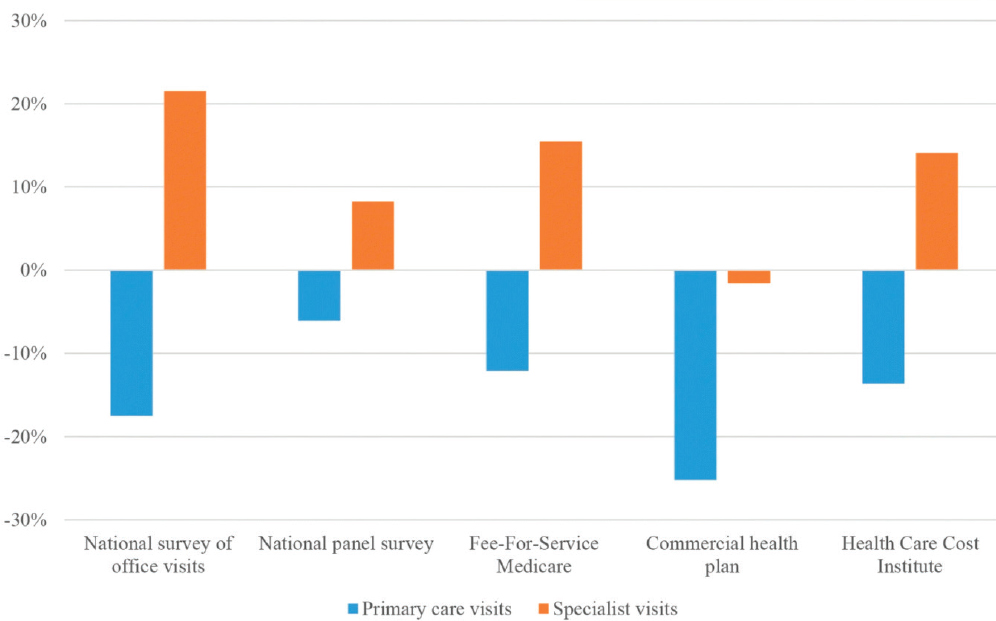

However, some evidence indicates that fewer people are going to a primary care office than a decade ago (see Chapter 3 for a more detailed discussion). Between 2008 and 2016, visits per person to primary care clinicians fell 6–25 percent, depending on the data source (Ganguli et al., 2019, 2020) (see Figure 1-2), with the sharpest declines in metropolitan areas and

SOURCE: Ganguli et al., 2019.

among individuals earning 200 percent or less of the federal poverty level (Ganguli et al., 2020). Primary care visits by commercially insured children and adolescents have also fallen by approximately 13 percent over the same period, with problem-based visits dropping 24 percent and preventive care visits increasing 10 percent (Ray et al., 2020), contrasting with increases in specialty visits.

While the value of primary care has remained steady, the U.S. system is in crisis and being eroded by many forces, including inadequate investment in and chronic under-resourcing of services; incompatible payment models; diminished trainee interest; increased opportunity for subspecialty training; the challenges of rural access; the decreasing scope or comprehensiveness of primary care in many settings; and the lack of integration with health systems, community-based services, and public health (Basu et al., 2019; Casalino et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2013; Christakis et al., 2001; Coker et al., 2013; Cooley et al., 2009; Coutinho et al., 2019; IOM, 2012a; Liaw et al., 2016; Long et al., 2012; MedPAC, 2014; Mostashari, 2016; Phillips et al., 2009).

This is not to say that high-quality primary care does not exist in the United States or that it is beyond the reach of all Americans. In fact, numerous practices and health care systems deliver high-quality primary care, but

these are far from the rule. Health centers,1 for example, deliver high-quality primary care based on an integrated, interprofessional team-based model (HRSA, 2020a,b). This is by design, supported by federal policy, payment, and practice transformation support (Rittenhouse et al., 2020). Overall, however, the country can—and must—do better, for without shoring up its primary care system, the fragile foundation that primary care represents today may continue to crumble and the nation’s health will suffer.

PROJECT ORIGIN AND STATEMENT OF TASK

In July 2018, the Health and Medicine Division2 of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) convened a planning meeting to discuss the current and future role of primary care in the United States and how the National Academies could address some of the current challenges in the field. The Board on Health Care Services hosted the meeting, with financial support from the American Board of Family Medicine Foundation.

The planning meeting sought to answer the following questions:

- What is the current and future role of primary care in the United States?

- What can the United States learn from primary care successes and failures from around the world?

- How can the National Academies advance progress and address the challenges facing primary care in the United States and internationally, and what questions should a National Academies consensus study or workshop address?

Meeting participants included a diverse set of stakeholders and primary care experts, including representatives from government agencies, international health organizations, private foundations, academic institutions, primary care researchers, interest groups, and a member of the committee that authored Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era (IOM, 1996).

Participants generally agreed that primary care in the United States needed transformative action and that a National Academies consensus study would allow for a committee to carefully develop an action plan that

___________________

1 Health centers, as defined by section 330 of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. § 254b), include outpatient clinics in federally designated underserved areas that qualify for specific reimbursement systems under Medicare and Medicaid.

2 As of March 2016, the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine continues the consensus studies and convening activities previously carried out by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM is used to refer to publications issued prior to July 2015.

could affect the future of primary care. This study was also deemed to be timely given that the World Health Organization and others were preparing to revisit the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration3 and a global recommitment to primary health care. The planning committee was clear that there was no need to re-litigate the evidence for the value of robust primary care, and the potential Statement of Task for a consensus study was instead focused on an action plan to strengthen primary care.

With the support of a broad coalition of sponsors (see Box 1-1), the study officially launched in October 2019. The National Academies formed the Committee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care with the charge to revisit previous National Academies’ reports on primary care, examine the current state of primary care in the United States, and develop an implementation plan to build on the recommendations of the 1996 IOM report (see Box 1-2).

___________________

3 The Declaration of Alma-Ata was adopted at the International Conference on Primary Health Care in what was then known as Alma-Ata in the Soviet Socialist Republic (today, it is known as Almaty, Kazakhstan). The conference and declaration called for national and international action to strengthen primary health care throughout the world (International Conference on Primary Health Care, 1978). The Declaration is available at https://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf (accessed October 5, 2020).

STUDY APPROACH

The Committee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care consisted of 20 members with a broad range of expertise, including clinical care, health care systems and administration, the health care workforce, health care policy, implementation science, health information technology, health care quality, health professional education, patient-centered outcomes research, community-oriented primary care, and health care payment. Appendix A presents brief biographies of the committee members, fellows, and staff.

The committee deliberated during five 2-day meetings and many conference calls between January 2020 and November 2020. At two of the meetings and one public webinar, outside speakers were invited to inform the committee’s deliberations, and members of the public were given the opportunity to provide questions, comments, and suggestions. The speakers provided valuable input on a broad range of topics, including primary care payment and policy, delivery innovations, implementation, and patient experiences and perspectives. During the webinar, invited patients and representatives from patient advocacy organizations presented their thoughts and experiences on what primary care meant to them and how it could be improved. In addition, a number of experts provided written input on a range of topics, and the committee commissioned three papers on the following topics: payment models in primary care, the COVID-19 pandemic and what it has revealed about primary care, and the historical transformation of primary care since 1981. The committee also completed an extensive search of the peer-reviewed literature, ultimately considering more than 6,000 articles and targeting English-language articles published since 2010 concerning primary care delivery, innovations, and implementation. The committee also reviewed gray literature, including publications by private organizations, government, and international organizations, with a focus on implementation strategies and successes.

While this report fully embraces the unique roles of all members of the interprofessional primary care team, the majority of published literature and data regarding primary care in the United States is physician-centric and often does not consider the many professions that are part of an interprofessional primary care team. The literature included in this report reflects the state of primary care research (PCR) today. Additionally, while the following chapters discuss the roles and responsibilities of many of the professions that can be part of an interprofessional primary care team, it was beyond the scope of this report to define these roles for every profession in the context of primary care delivery. Similarly, challenges and arguments around scope of practice issues for the various professions in primary care have been the focus of other National Academies reports (IOM, 2011a,b;

NASEM, 2016) and the committee purposefully chose to avoid discussion of most of them in this report for several reasons. First and foremost, it remains a struggle within primary care to attract health professionals of all types who have ample opportunities for more lucrative specialty roles in the health care system. Most of the recommended actions in the committee’s implementation plan focus on solving the problems common to all of the professions engaged in primary care with the goal of building more effective teams and addressing patients’ needs. Second, in most cases, patients need teams of health professionals able to address the widest spectrum of conditions and issues presented anywhere in the health care system and to do so in a comprehensive, sustained way. In these teams, each health professional brings important capacities and competencies that should not be constrained by laws or policy if they are able to contribute to good care. Third, given the diversity of communities and the general struggle to equitably serve them all, primary care cannot be delivered through a single model, and laws or policies should be enabling of serving every community and meeting their particular needs. While the committee freely acknowledges that disagreements around scope of practice are real and related to structural, professional inequities, they are not unique to primary care and the committee felt that it was outside the scope of its Statement of Task to say how they should be resolved.

STUDY CONTEXT

Two earlier reports—Defining Primary Care: An Interim Report (IOM, 1994) and Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era (IOM, 1996)—were foundational and influential works that represented an ambitious plan to strengthen primary care in the United States. These reports defined primary care as “the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community” (IOM, 1994, p. 15, 1996, p. 1).

The authoring committees emphasized in their reports that the term “primary” indicated that such care is first and fundamentally care, and primary care is not a specialty or a discipline but an essential, generalist function to which everyone in the population should have access. The inclusion of the words “integrated,” “sustained partnership,” and “context of family and community” reflected a responsibility to connect with other actors in the health system and a prominent population health perspective. It is the current committee’s position that primary care’s essential contribution to population health makes it a common good requiring investment and both

societal and political support. While the 1996 definition4 of primary care is still highly relevant, this study committee felt that it did not fully capture what high-quality primary care means today, and the committee offers an updated definition in Chapter 2.

Of the comprehensive recommendations in the 1996 report, most were never implemented but remain relevant today. That inaction can be attributed to a number of contextual factors and barriers, several of which are described below. The committee developed this report and its recommendations and implementation strategy with these barriers in mind.

A 2012 report, Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health (IOM, 2012b), offered ways to expand the potency of primary care in partnership with public health. Broad recommendations included the need for interagency collaboration regarding maternal and child health, cardiovascular disease prevention, and colorectal cancer screening to address the broader social determinants of health (SDOH) and the comprehensive and interrelated aspects of physical, mental, and social health and well-being (Bielaszka-DuVernay, 2011; Bodenheimer et al., 2014; Landon et al., 2012; Love et al., 2019; Phillips and Bazemore, 2010; Starfield et al., 2005). The 2012 report’s recommendations also remain largely unapplied, suggesting major barriers to implementing more robust primary care systems in partnership with public health.

This report revisits many of the outstanding issues these reports raised but through an updated, more expansive view of primary care. This committee also asserts that primary care is a common good—that every person in the United States should have access to high-quality primary care at all times in their lives; it should not be an optional service only available to certain age groups or classes of people. This report is not, however, an exhaustive review of the evidence supporting the importance of primary care writ large—that evidence is well documented (Basu et al., 2019; Levine et al., 2019; Macinko et al., 2003; Shi, 2012) and is an underlying assumption in the chapters that follow. Rather, this report focuses on implementing innovative solutions to improve the nation’s ability to realize the full potential for primary care and addresses the systemic barriers that prevent attaining robust high-quality primary care for all U.S. populations.

Why the 1996 Recommendations Failed to Gain Traction

The committee began by evaluating the status and relevance of the 31 recommendations in Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era (IOM,

___________________

4 Note that the IOM definition of primary care provided in Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era (IOM, 1996) first appeared in Defining Primary Care: An Interim Report (IOM, 1994). This report refers to this as “the 1996 IOM definition.”

1996) (see Box 1-3 for a summary of the recommendations; see Appendix B for the complete text of the recommendations). As noted, many of the recommendations have not been implemented, which may be partly attributable to the presentation of many of the recommendations as aspirational goals, without identifying specific actors that would be accountable for following through. Systemic barriers to their implementation also existed, many of which persist today.

Lack of Centralized Accountability

Recommendation 9.1 from the 1996 report called for establishing a public–private consortium to oversee implementing the remaining recommendations. That study committee recognized the lack of an umbrella organizing body for the field of primary care and acknowledged that, without one, there was little chance for meaningful change. Today, there remains no singular, centralized body, professional society, or government agency, meaning that systemic change must occur by way of a number of independent stakeholders and actors, many of which may not be aligned, coordinated, or given shared accountability. In 2020, however, seven of the physician professional societies and boards did come together to propose sweeping changes in primary care policy, many of which align with the themes of this report (AAFP et al., 2020), suggesting that the field recognizes a need to be better aligned in purpose and mission.

Given that this committee’s charge was to develop an implementation plan to improve primary care, the committee acknowledged the difficulty of developing specific strategies that would depend on a wide array of independent or poorly coordinated stakeholders and organizations and strongly agrees with the 1996 committee’s idea that such an organization would help facilitate needed changes. Building on the 1996 recommendation, this committee proposes a more targeted, specific approach to ensuring that improvement efforts are coordinated and that stakeholders in the field are held accountable (see Chapter 12).

Demise of Health Care Reform

The demise of the federal effort to reform health care in 1994 also contributed to the limited impact of the 1996 recommendations. In 1993, at the beginning of the 1996 study process, the Clinton administration’s proposal to comprehensively reform health care and guarantee universal health insurance coverage had widespread political and popular support and seemed likely to succeed (Skocpol, 1995). The plan contained a number of provisions that would have strengthened primary care and provided access to those previously uninsured, but political forces led to the ultimate

failure of the proposed Health Security Act.5 Had health care reform passed in 1995, the health care community and the actors within it might have been more empowered to take up and implement many of the recommendations put forth by the 1996 report, including for universal access and coverage. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act6 passed in 2010 enabled many previously uninsured Americans to obtain health insurance and did strengthen primary care in many ways (Davis et al., 2011), but it still fell short of the original 1996 recommendation for universal coverage. While reform that provides universal coverage and access would further strengthen primary care and the health of the nation considerably, the current committee considered the historical context of health care reform and

___________________

5 Health Security Act, § 1757, 103rd Congress (1993–1994).

6 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 111-148 (March 23, 2010).

strategies to facilitate universal access to high-quality primary care within the realities of the current health insurance landscape in the United States.

Limited Implementation of Newer Models of Care Delivery

New models of care have been developed since 1996, and one in particular, the patient-centered medical home (PCMH), was advanced as a solution to implementing many of the goals of the 1996 report. The PCMH model combines the essence of primary care with innovations to better align care processes with patient needs. The core principles include improved access, continuity of care, comprehensive team-based care, care coordination, quality and safety, and a reimbursement structure that supports the functions of primary care. A key component of the model is that everyone, both adults and children, maintains an ongoing relationship

with a team at the practice level, led by a personal primary care clinician that collectively takes responsibility for ongoing care. While the model has been endorsed by many medical specialty groups and health care organizations, challenges inhibiting its widespread adoption include incompatible payment systems, significant upfront investment, and pervasive incentives to maintain current practice models, among other barriers (Arend et al., 2012; Basu et al., 2016, 2017; Fleming et al., 2017; Kizer, 2016; Reynolds et al., 2015) (see Chapter 9 on payment models). The PCMH model also falls short of community-oriented and people-centered primary care (WHO, 2016) and the integration with public health called for in prior IOM reports (1983, 2012a).

Lack of Collaboration to Improve Education and Training

The 1996 report made nine recommendations concerning education and training for primary care, but mental health, public health, primary care, and other clinical disciplines involved in primary care have not yet formed a collaboration to advance essential competencies. Despite calls to reform the basic organization and financing of clinician training (IOM, 2014), little progress has been made. In fact, despite repeated recommendations to realign graduate medical education (GME) funding and accountability to focus on primary care and population health (COGME, 2010; IOM, 1989, 2014), there have been no major reforms to GME that might shift the balance toward the future workforce that is needed.

The policy of hospitals being central to financing clinical medical education limits the extent to which training can take place in the settings where primary care actually occurs (COGME, 2007; IOM, 1989). Between 2006 and 2008, only about 25 percent of those from the medical education pipeline entered primary care and around 5 percent practiced in rural settings (Chen et al., 2013), an output insufficient to maintain the current proportion of primary care physicians in the overall physician workforce. While training models and environments do demonstrate higher primary care and rural outputs, these are not priorities for most major teaching hospitals (Phillips et al., 2009, 2013; Raffoul et al., 2019; Rosenthal, 2000). Remarkably little funding also goes to support postgraduate training of other health professionals to prepare for clinical practice in primary care. Chapter 6 discusses options to improve the education and training of the primary care workforce.

A series of IOM reports in the early 2000s showed that interprofessional teams and collaborative practices improve health outcomes (IOM, 2001, 2007), yet despite the evidence and the many calls to better integrate training across professions, its clinicians remain largely professionally siloed, and so the availability of joint learning experiences remains

a challenge (Cuff et al., 2014; Lipstein et al., 2016; Ritchie et al., 2016; The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, 2010). Progress is needed on educational tools to enhance the communication and teamwork of clinicians in primary care and also for education on how specialists and primary care clinicians can improve care coordination and understanding of each other’s roles. See Chapter 5 for more on the evidence behind team-based care, effective models, and resource needs.

Erosion of the Primary Care Workforce

The 1996 report made several recommendations to help strengthen the primary care workforce, but a shortage remains, particularly in rural areas. Increasing the density of primary care physicians7 by adding 10 more per 100,000 people is associated with an increase in life expectancy of more than 51 days (Basu et al., 2019). That study also found that the U.S. primary care physician workforce had declined by 5.2 physicians per 100,000 population overall and 7.0 physicians per 100,000 population in rural counties between 2005 and 2015, the exact opposite of what is needed. This erosion of workforce capacity is associated with a loss of 85 lives per day overall and about 16 per day in rural counties, which is the equivalent of a 200-person airplane crashing every 2–3 days (see Appendix C for the committee’s calculations). The failure of current primary care physician production and policies to make primary care a more viable career, especially in rural areas, has important implications for health outcomes and inequities.

Lack of a Primary Care Research Agenda

PCR is a distinct and unique area of scientific inquiry. It includes novel approaches to acute, chronic, and preventive care in the context of whole-person care; developing and improving systems of care; disseminating and implementing evidence-based care; addressing behavioral health and SDOH as part of care; using technology for care; and uniquely blending individual care and population health. While the past 25 years have shown rapid advances in technology and science that could improve the delivery and outcomes of primary care, no federal agency has embraced and funded PCR, and no dedicated research funding is available (Mendel et al., 2020). Specifically, no single entity is responsible for developing and advancing a robust program of research on primary care despite it being the largest

___________________

7 Throughout the report, the committee’s use of the word “physician” refers to both allopathic and osteopathic physicians.

platform for health care delivery and often the only source of health care for nearly half of people seeking care each year (Petterson et al., 2018).

The 1996 report recommended that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services “identify a lead agency for primary care research and … the Congress of the United States [should] appropriate funds for this agency in an amount adequate to build both the infrastructure required to conduct primary care research and fund high-priority research projects” (IOM, 1996, p. 11). Today, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is the only federal agency with a mandate for PCR, but its National Center for Excellence in Primary Care has no dedicated research funding, limiting its ability to meaningfully contribute to the field (CAFM, 2019). AHRQ’s entire funding is $500 million per year compared to the $50 billion annual budget of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and just 0.2 percent of NIH funding supports family medicine research (Cameron et al., 2016). See Chapter 10 for more on PCR needs.

Misaligned Payment Models

Since the 1996 report, the disconnection between fee-for-service (FFS) payment and high-quality primary care has become even more clear. Payment tied to individual services without the ability to either focus on whole-person care or support interprofessional teams that deliver flexible services tailored to patient and community needs has stalled progress and held the entire enterprise back. The growing misalignment between revenue and the expense of supporting the delivery of high-quality primary care has also challenged the advancement of primary care. For example, many practices discovered that the financial investments involved with practice transformation or meeting specific PCMH requirements far exceeded the added compensation for PCMH certification (Basu et al., 2017; Fleming et al., 2017; Halladay et al., 2016; Martsolf et al., 2016; Nutting et al., 2012; Patel et al., 2013). Similarly, the costs for adopting and implementing electronic health records were more than the Meaningful Use payments (see Chapter 8). While other segments of the health care system were able to rapidly increase charges and reimbursement rates to compensate for the high cost of labor (Papanicolas et al., 2018), primary care encountered similar hikes in administrative and personnel costs without comparable increases in payment rates. This left little or no choice for many small, independent primary care practices other than purchase by larger, for-profit health systems, which enabled them to increase rates for delivering essentially the same services (Mostashari, 2016; Scheffler et al., 2018). Yet, people cared for by smaller, independent practices are significantly more likely to have lower costs and comparable outcomes (Casalino et al., 2014; Mostashari, 2016).

The increasing popularity of high-deductible health insurance plans (KFF, 2019; Wilde Mathews, 2018) and shifting of costs to consumers to maintain insurance companies’ profit margins (Altman and Mechanic, 2018) has disproportionately impacted primary care. It is a relatively low-cost service in comparison to others within the health care system, so many people must pay the entire bill for non-preventive services because the amount is below their deductible. Paradoxically, this phenomenon deters people from seeking primary care, arguably the most cost-effective type of care that could prevent much higher health care costs (Ganguli et al., 2020).

Fragmentation of the U.S. Health Care System

Isolated examples provide evidence of progress toward the 1996 report’s nine recommendations regarding interdisciplinary education and training for primary care, and several good examples of integrated health systems exist today. However, care organization remains largely fragmented in most settings, perpetuating a less efficient, less effective, less equitable, and more expensive system of care (Stange, 2009). Attempts to correct this have been plentiful and valiant, if isolated; some exemplars are presented throughout this report. Ultimately, a degree of tribalism between professions and subspecialties and an emphasis on disease-specific care within the health care system exist at the expense of the long-term vision of integration that would benefit whole-person health. See Chapter 5 for more on integrated delivery.

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Calls for Social Justice

The COVID-19 pandemic began in the early stages of this committee’s work; it revealed many vulnerabilities in how primary care is delivered today and further highlighted deep fissures in health equity resulting from racism and social injustice for individuals and families with undocumented immigration status or living in poverty (Dorn et al., 2020; Smith, 2020). If COVID-19 was a stress test of how well our country has supported its primary care infrastructure, the results have not been encouraging. Perhaps most notably, it has clearly demonstrated that large segments of our population do not have reliable access to primary care.

The pandemic also demonstrated that building a primary care system largely dependent on FFS payments is highly precarious. Such arrangements, which are the predominant payment method, have jeopardized the very existence of many primary care practices because the volume of visits declined rapidly as the pandemic took hold (Basu et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2020). It is disappointing that the U.S. government hardly considered

the role of primary care—our nation’s largest and most distributed platform for health care—in its national epidemic planning (HHS, 2017; Holloway et al., 2014). This neglect is more marked considering that primary care is the frontline of COVID-19 triaging, testing, managing, and ultimately immunizing (Goodnough, 2021; Lewis et al., 2020). Congress also did not specifically consider primary care in its first four relief packages (Slavitt and Mostashari, 2020). By the time this report is published, the impacts of the pandemic may reveal more, particularly as care, testing, and vaccine administration for COVID-19 shift to primary care and patients reemerge, as cities and states begin to reopen, and make their way back to their primary care clinicians. A fundamental question will be whether primary care practices survive the economic crisis. Throughout this report, COVID-19 provides a useful lens on primary care problems, responses, and recommendations while also highlighting the gross inequalities and social injustices within society that are reflected in primary care practice.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States also experienced a massive call for social justice, led by the Black Lives Matter movement, unlike anything experienced since the civil rights era of the 1960s. The nationwide discontent with the structural and institutional discrimination was further fueled by the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on the most disadvantaged and underserved populations, especially Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic groups (Tai et al., 2020). This is only the latest and perhaps most graphic illustration of racial and ethnic disparities in care and health outcomes that have been well documented and, along with growing economic inequities, are likely contributing to the decline in U.S. life expectancy in recent years (IOM, 2003; Woolf and Schoomaker, 2019).

The combination of events directly speaks to the committee’s Statement of Task, particularly in terms of achieving health equity and population health goals and improving access, especially for underserved populations. While it is true that many of the same issues tackled in the 1996 report remain relevant, the United States of 2021 has radically changed due to the growth of the Internet, globalization, COVID-19, and the collective awakening to the impact of racism, all of which influence how people, families, and communities view and experience primary care. The implementation plan called for in the committee’s Statement of Task attempts to address the barriers that thwarted the 1996 report’s success, particularly in naming specific actors and actions that could secure this important foundation of health care and health. However, the committee considers other ideas and solutions that aim to achieve similar ends. COVID-19 and issues of equity are discussed throughout this report.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

The committee divided the report into 12 chapters. The remainder of this report lays out the committee’s analysis of the current U.S. primary care system, which served as the basis for its recommendations and implementation plan. Chapter 2 provides a new definition of primary care, one that reflects the committee’s vision for what it should be in the 21st century, and Chapter 3 presents the current state of U.S. primary care. Chapter 4 discusses the reasons primary care should be person centered, family centered, and community oriented, and Chapter 5 discusses how integrated primary care delivery is a foundational strategy for how health care organizations can support a culture of high-quality, person-centered, family-centered, and community-oriented primary care. Chapter 6 covers how the nation can build the workforce needed to enable primary care and interprofessional teams capable of supporting the whole person. Chapter 7 details why high-functioning digital technologies are an essential component of creating a high-quality primary care system that helps coordinate care and reduce clinician burnout, and Chapter 8 explains the importance of accountability and how the ability to monitor quality with metrics designed specifically for primary care will support implementing high-quality primary care. Chapter 9 discusses the critical role that revamping the current payment system can play in creating a system that can support independent primary care practices and the emerging array of new primary care delivery models. Chapter 10 makes the case for why the nation needs to invest specifically in PCR rather than relying on research in subspecialty care, hospitals, or single-disease cohorts. Chapter 11 describes the implementation, accountability, and public policy-making frameworks the committee used to develop its recommended implantation plan, presented in Chapter 12. Because many of the committee’s recommended actions that comprise its implementation plan draw from information presented in more than one chapter, the specific actions of the implementation plan are included only in Chapter 12 and the Summary.

In addition to the core content, there are five appendixes. Appendix A presents the biographies of the committee members, fellows, and staff. Appendix B lists the full slate of the recommendations from the 1996 IOM report Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Appendix C includes the committee’s calculations to determine the loss of life associated with decreased density of the primary care physician workforce presented earlier in this chapter. Appendix D maps the committee’s recommended actions to different actors. Appendix E puts forth a scorecard for measuring the health of the U.S. primary care system.

REFERENCES

AAFP, AAP, ABFM, ABIM, ABP, ACP, and SGIM (American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Board of Family Medicine, American Board of Internal Medicine, American Board of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, and Society of General Internal Medicine). 2020. A new primary care paradigm. https://www.newprimarycareparadigm.org (accessed December 23, 2020).

Altman, S., and R. Mechanic. 2018. Health care cost control: Where do we go from here? Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180705.24704/ full (accessed July 13, 2020).

Arend, J., J. Tsang-Quinn, C. Levine, and D. Thomas. 2012. The patient-centered medical home: History, components, and review of the evidence. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine 79(4):433–450.

Baillieu, R., M. Kidd, R. Phillips, M. Roland, M. Mueller, D. Morgan, B. Landon, J. DeVoe, V. Martinez-Bianchi, H. Wang, R. Etz, C. Koller, N. Sachdev, H. Jackson, Y. Jabbarpour, and A. Bazemore. 2019. The primary care spend model: A systems approach to measuring investment in primary care. BMJ Global Health 4(4):e001601.

Basu, S., R. S. Phillips, Z. Song, B. E. Landon, and A. Bitton. 2016. Effects of new funding models for patient-centered medical homes on primary care practice finances and services: Results of a microsimulation model. Annals of Family Medicine 14(5):404–414.

Basu, S., R. Phillips, Z. Song, A. Bitton, and B. Landon. 2017. High levels of capitation payments needed to shift primary care toward proactive team and nonvisit care. Health Affairs 36:1599–1605.

Basu, S., S. A. Berkowitz, R. L. Phillips, A. Bitton, B. E. Landon, and R. S. Phillips. 2019. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005–2015. JAMA Internal Medicine 179(4):506–514.

Basu, S., R. S. Phillips, R. Phillips, L. E. Peterson, and B. E. Landon. 2020. Primary care practice finances in the United States amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Affairs 39(9):1605–1614.

Bielaszka-DuVernay, C. 2011. Vermont’s blueprint for medical homes, community health teams, and better health at lower cost. Health Affairs 30(3):383–386.

Bodenheimer, T., and C. Sinsky. 2014. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine 12(6):573–576.

Bodenheimer, T., A. Ghorob, R. Willard-Grace, and K. Grumbach. 2014. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Annals of Family Medicine 12(2):166–171.

CAFM (Council of Academic Family Medicine). 2019. Fund AHRQ’s primary care research center. Washington, DC: Council of Academic Family Medicine.

Cameron, B. J., A. W. Bazemore, and C. P. Morley. 2016. Lost in translation: NIH funding for family medicine research remains limited. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice 29(5):528–530.

Casalino, L. P., M. F. Pesko, A. M. Ryan, J. L. Mendelsohn, K. R. Copeland, P. P. Ramsay, X. Sun, D. R. Rittenhouse, and S. M. Shortell. 2014. Small primary care physician practices have low rates of preventable hospital admissions. Health Affairs 33(9):1680–1688.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2019. Summary Health Statistics Tables: National Health Interview Survey, 2018 (Table A-16). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Chen, C., S. Petterson, R. L. Phillips, F. Mullan, A. Bazemore, and S. D. O’Donnell. 2013. Towards graduate medical education (GME) accountability: Measuring the outcomes of GME institutions. Academic Medicine 88(9):1267–1280.

Christakis, D. A., L. Mell, T. D. Koepsell, F. J. Zimmerman, and F. A. Connell. 2001. Association of lower continuity of care with greater risk of emergency department use and hospitalization in children. Pediatrics 107(3):524–529.

Christian, E., V. Krall, S. Hulkower, and S. Stigleman. 2018. Primary care behavioral health integration: Promoting the quadruple aim. North Carolina Medical Journal 79(4):250–255.

COGME (Council on Graduate Medical Education). 2007. New paradigms for physician training for improving access to health care. Washington, DC: Council on Graduate Medical Education.

COGME. 2010. Advancing primary care. Rockville, MD: Council on Graduate Medical Education.

Coker, T. R., T. Thomas, and P. J. Chung. 2013. Does well-child care have a future in pediatrics? Pediatrics 131(Suppl 2):S149–S159.

Cooley, W. C., J. W. McAllister, K. Sherrieb, and K. Kuhlthau. 2009. Improved outcomes associated with medical home implementation in pediatric primary care. Pediatrics 124(1):358–364.

Coutinho, A. J., Z. Levin, S. Petterson, R. L. Phillips, Jr., and L. E. Peterson. 2019. Residency program characteristics and individual physician practice characteristics associated with family physician scope of practice. Academic Medicine 94(10):1561–1566.

Cuff, P., M. Schmitt, B. Zierler, M. Cox, J. De Maeseneer, L. L. Maine, S. Reeves, H. C. Spencer, and G. E. Thibault. 2014. Interprofessional education for collaborative practice: Views from a global forum workshop. Journal of Interprofessional Care 28(1):2–4.

Davis, K., M. Abrams, and K. Stremikis. 2011. How the Affordable Care Act will strengthen the nation’s primary care foundation. Journal of General Internal Medicine 26(10): 1201–1203.

Dorn, A. V., R. E. Cooney, and M. L. Sabin. 2020. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. The Lancet 395(10232):1243–1244.

Fleming, N. S., B. da Graca, G. O. Ogola, S. D. Culler, J. Austin, P. McConnell, R. McCorkle, P. Aponte, M. Massey, and C. Fullerton. 2017. Costs of transforming established primary care practices to patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 30(4):460–471.

Ganguli, I., T. H. Lee, and A. Mehrotra. 2019. Evidence and implications behind a national decline in primary care visits. Journal of General Internal Medicine 34(10):2260–2263.

Ganguli, I., Z. Shi, E. J. Orav, A. Rao, K. N. Ray, and A. Mehrotra. 2020. Declining use of primary care among commercially insured adults in the United States, 2008–2016. Annals of Internal Medicine 172(4):240–247.

Goodnough, A. 2021. In quest for herd immunity, giant vaccination sites proliferate. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/28/health/covid-vaccine-sites.html (accessed March 1, 2021).

Green, L. A., G. E. Fryer, Jr., B. P. Yawn, D. Lanier, and S. M. Dovey. 2001. The ecology of medical care revisited. New England Journal of Medicine 344(26):2021–2025.

Halladay, J. R., K. Mottus, K. Reiter, C. M. Mitchell, K. E. Donahue, W. M. Gabbard, and K. Gush. 2016. The cost to successfully apply for level 3 medical home recognition. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice 29(1):69–77.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2017. Pandemic influenza plan: 2017 update. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Holloway, R., S. A. Rasmussen, S. Zaza, N. J. Cox, and D. B. Jernigan. 2014. Updated preparedness and response framework for influenza pandemics. Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). 2020a. Behavioral health and primary care integration. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/qualityimprovement/clinicalquality/behavioralhealth/index.html (accessed March 2, 2021).

HRSA. 2020b. Oral health and primary care integration. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/qualityimprovement/clinicalquality/oralhealth/index.html (accessed March 2, 2021).

International Conference on Primary Health Care. 1978. Declaration of Alma-Ata. Alma-Ata, USSR: World Health Organization.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1983. Community oriented primary care: New directions for health services delivery. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1989. Primary care physicians: Financing their graduate medical education in ambulatory settings. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1994. Defining primary care: An interim report. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1996. Primary care: America’s health in a new era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2003. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2007. Preventing medication errors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011a. Advancing oral health in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011b. The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2012a. For the public’s health: Investing in a healthier future. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2012b. Primary care and public health: Exploring integration to improve population health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2014. Graduate medical education that meets the nation’s health needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Johansen, M. E., S. M. Kircher, and T. R. Huerta. 2016. Reexamining the ecology of medical care. New England Journal of Medicine 374(5):495–496.

Kempski, A., and A. Greiner. 2020. Primary care spending: High stakes, low investment. Washington, DC: Primary Care Collaborative.

KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). 2019. Employer health benefits: 2019 annual survey. San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Kizer, K. W. 2016. Understanding the costs of patient-centered medical homes. Journal of General Internal Medicine 31(7):705–706.

Koller, C. F., and D. Khullar. 2017. Primary care spending rate—a lever for encouraging investment in primary care. New England Journal of Medicine 377(18):1709–1711.

Kringos, D. S., W. Boerma, J. van der Zee, and P. Groenewegen. 2013. Europe’s strong primary care systems are linked to better population health but also to higher health spending. Health Affairs 32(4):686–694.

Landon, B. E., K. Grumbach, and P. J. Wallace. 2012. Integrating public health and primary care systems: Potential strategies from an IOM report. JAMA 308(5):461–462.

Levine, D. M., B. E. Landon, and J. A. Linder. 2019. Quality and experience of outpatient care in the United States for adults with or without primary care. JAMA Internal Medicine 179(3):363–372.

Lewis, C., S. Seervai, T. Shah, M. K. Abrams, and L. Zephyrin. 2020. Primary care and the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/primary-care-and-covid-19-pandemic (accessed July 1, 2020).

Liaw, W. R., A. Jetty, S. M. Petterson, L. E. Peterson, and A. W. Bazemore. 2016. Solo and small practices: A vital, diverse part of primary care. Annals of Family Medicine 14(1):8–15.

Lipstein, S. H., A. L. Kellermann, B. Berkowitz, R. Phillips, D. Sklar, G. D. Steele, and G. E. Thibault. 2016. Workforce for 21st century health and health care: A vital direction for health and health care. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine.

Long, W. E., H. Bauchner, R. D. Sege, H. J. Cabral, and A. Garg. 2012. The value of the medical home for children without special health care needs. Pediatrics 129(1):87–98.

Love, H. E., J. Schlitt, S. Soleimanpour, N. Panchal, and C. Behr. 2019. Twenty years of school-based health care growth and expansion. Health Affairs 38(5):755–764.

Macinko, J., B. Starfield, and L. Shi. 2003. The contribution of primary care systems to health outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, 1970–1998. Health Services Research 38(3):831–865.

Martin, S., R. L. Phillips, Jr., S. Petterson, Z. Levin, and A. W. Bazemore. 2020. Primary care spending in the United States, 2002–2016. JAMA Internal Medicine 180(7):1019–1020.

Martsolf, G. R., R. Kandrack, R. A. Gabbay, and M. W. Friedberg. 2016. Cost of transformation among primary care practices participating in a medical home pilot. Journal of General Internal Medicine 31(7):723–731.

MedPAC (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission). 2008. Report to the Congress: Reforming the delivery system. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.

MedPAC. 2014. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.

Mendel, P., C. A. Gidengil, A. Tomoaia-Cotisel, S. Mann, A. J. Rose, K. J. Leuschner, N. S. Qureshi, V. Kareddy, J. L. Sousa, and D. Kim. 2020. Health services and primary care research study: Comprehensive report. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Mostashari, F. 2016. The paradox of size: How small, independent practices can thrive in value-based care. Annals of Family Medicine 14(1):5–7.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Assessing progress on the Institute of Medicine report The Future of Nursing. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC (National Research Council) and IOM. 2013. U.S. health in international perspective: Shorter lives, poorer health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nutting, P. A., B. F. Crabtree, and R. R. McDaniel. 2012. Small primary care practices face four hurdles—including a physician-centric mind-set—in becoming medical homes. Health Affairs 31(11):2417–2422.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2019. Deriving preliminary estimates of primary care spending under the SHA 2011 framework. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Papanicolas, I., L. R. Woskie, and A. K. Jha. 2018. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA 319(10):1024–1039.

Park, B., S. B. Gold, A. Bazemore, and W. Liaw. 2018. How evolving United States payment models influence primary care and its impact on the quadruple aim. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 31(4):588–604.

Patel, M. S., M. J. Arron, T. A. Sinsky, E. H. Green, D. W. Baker, J. L. Bowen, and S. Day. 2013. Estimating the staffing infrastructure for a patient-centered medical home. American Journal of Managed Care 19(6):509–516.

Petterson, S., R. McNellis, K. Klink, D. Meyers, and A. Bazemore. 2018. The state of primary care in the United States: A chartbook of facts and statistics. Washington, DC: Robert Graham Center.

Phillips, R. L., Jr., and A. W. Bazemore. 2010. Primary care and why it matters for U.S. health system reform. Health Affairs 29(5):806–810.

Phillips, R. L., Jr., M. Dodoo, S. Petterson, I. Xierali, A. Bazemore, B. Teevan, K. Bennett, C. Legagneur, J. Rudd, and J. Phillips. 2009. Specialty and geographic distribution of the physician workforce: What influences medical student and resident choices? Washington, DC: Robert Graham Center.

Phillips, R. L., Jr., S. Petterson, and A. Bazemore. 2013. Do residents who train in safety net settings return for practice? Academic Medicine 88(12):1934–1940.

Phillips, R. L., Jr., A. Bazemore, and A. Baum. 2020. The COVID-19 tsunami: The tide goes out before it comes in. Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200415.293535/full (accessed December 18, 2020).

Raffoul, M., G. Bartlett-Esquilant, and R. L. Phillips, Jr. 2019. Recruiting and training a health professions workforce to meet the needs of tomorrow’s health care system. Academic Medicine 94(5):651–655.

Ray, K. N., Z. Shi, I. Ganguli, A. Rao, E. J. Orav, and A. Mehrotra. 2020. Trends in pediatric primary care visits among commercially insured U.S. children, 2008–2016. JAMA Pediatrics 174(4):350–357.

Reid, R., C. Damberg, and M. W. Friedberg. 2019. Primary care spending in the fee-for-service medicare population. JAMA Internal Medicine 179(7):977–980.

Reiff, J., N. Brennan, and J. Fuglesten Biniek. 2019. Primary care spending in the commercially insured population. JAMA 322(22):2244–2245.

Reynolds, P. P., K. Klink, S. Gilman, L. A. Green, R. S. Phillips, S. Shipman, D. Keahey, K. Rugen, and M. Davis. 2015. The patient-centered medical home: Preparation of the workforce, more questions than answers. Journal of General Internal Medicine 30(7):1013–1017.

Ritchie, C., R. Andersen, J. Eng, S. K. Garrigues, G. Intinarelli, H. Kao, S. Kawahara, K. Patel, L. Sapiro, A. Thibault, E. Tunick, and D. E. Barnes. 2016. Implementation of an interdisciplinary, team-based complex care support health care model at an academic medical center: Impact on health care utilization and quality of life. PLOS ONE 11(2):e0148096.

Rittenhouse, D. R., J. A. Wiley, L. E. Peterson, L. P. Casalino, and R. L. Phillips. 2020. Meaningful use and medical home functionality in primary care practice. Health Affairs 39(11):1977–1983.

Rosenthal, T. C. 2000. Outcomes of rural training tracks: A review. Journal of Rural Health 16(3):213–216.

Rui, P., and T. Okeyode. 2016. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2016 national summary tables. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Scheffler, R. M., D. R. Arnold, and C. M. Whaley. 2018. Consolidation trends in California’s health care system: Impacts on ACA premiums and outpatient visit prices. Health Affairs 37(9):1409–1416.

Shi, L. 2012. The impact of primary care: A focused review. Scientifica 2012:432892.

Skocpol, T. 1995. The rise and resounding demise of the Clinton plan. Health Affairs 14(1): 66–85.

Slavitt, A., and F. Mostashari. 2020. Covid-19 is battering independent physician practices. They need help now. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2020/05/28/covid-19-battering-independent-physician-practices (accessed December 1, 2020).

Smith, D. B. 2020. The pandemic challenge: End separate and unequal healthcare. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 360(2):109–111.

Stange, K. C. 2009. The problem of fragmentation and the need for integrative solutions. Annals of Family Medicine 7(2):100–103.

Starfield, B., L. Shi, and J. Macinko. 2005. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Quarterly 83(3):457–502.

Tai, D. B. G., A. Shah, C. A. Doubeni, I. G. Sia, and M. L. Wieland. 2020. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the united states. Clinical Infectious Diseases ciaa815.

The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation. 2010. Educating nurses and physicians: Toward new horizons conference summary. Palo Alto, CA: The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

The Larry A. Green Center, and PCC (Primary Care Collaborative). 2020. Quick COVID-19 primary care survey: Clinician series 9 fielded May 8–11, 2020. https://www.green-center.org/covid-survey (accessed January 21, 2021).

White, K. L., T. F. Williams, and B. G. Greenberg. 1961. The ecology of medical care. New England Journal of Medicine 265:885–892.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2016. Framework on integrated, people-centered health services. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Wilde Mathews, A. 2018. Behind your rising health-care bills: Secret hospital deals that squelch competition. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/behind-your-rising-health-care-bills-secret-hospital-deals-that-squelch-competition-1537281963 (accessed January 8, 2020).

Woolf, S. H., and H. Schoomaker. 2019. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959–2017. JAMA 322(20):1996–2016.

This page intentionally left blank.