9

Payment to Support High-Quality Primary Care

The committee supports a low-burden payment model that enables sustainable, team- and relationship-based, high-quality, integrated primary care; allows all people to have ready access to primary care teams across modalities; and assists people in addressing social determinants of health (SDOH). Payment should be adequate to support high-quality, independent primary care practices and flexible enough to support an emerging array of new delivery models. Payment reform should not, however, be a mechanism for reducing U.S. health care costs significantly in the short term but rather represent an investment for improving the health of the population.

WHY MONEY MATTERS

A fundamental assumption in the vision above is that money matters for achieving policy priorities. Payment models create the fiscal space in which care delivery can either flourish or be constrained. Vision statements, research evidence, leadership, and well-intentioned policy will not change the structure and performance of a system if they are not supported by adequate, goal-aligned resources. While a broad range of personal and social values motivate maintaining health and providing health care, an element of health care is transactional, with payment rendered for services provided. During the committee’s information-gathering activities, patients underscored the difficulty and burdensome nature of navigating the health system and payment for services, highlighting that the fragmented and fee-for-service (FFS) U.S. payment system has observable effects on patient care and outcomes. How much payment is rendered and how significantly affect

the volume and nature of primary care services available to a population (Quinn, 2015).

Primary care clinicians work in many organizational contexts, as discussed throughout this report. This chapter briefly touches upon income but does not focus on how clinicians are compensated within their organization or how funds flow from payers through organizations to clinicians; rather, it addresses how their organizations are paid by governments, insurers, and people seeking care. Although compensation plays an important role in individual behavior, the extent and methods of payment from third parties to the organization have more fundamental effects on the extent and nature of primary care in the United States, the focus of the committee’s work. However, how primary care payments flow through organizations to reach and influence primary care delivery, and whether they are aligned with overall intent, remains a critical issue.

For the purposes of this chapter and the committee’s report, the committee assumes that the current multi-payer, largely employment-based system will implement its recommendations. Changes to this assumption would affect the committee’s recommendations significantly but are outside of its scope of work. Please see other work from the Institute of Medicine and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine for discussions on financing insurance in the United States (IOM, 2004, 2009; NASEM, 2019b).

How Much Payment Is Rendered

How much payment is rendered for a service confers social value. In the United States, primary care physicians (PCPs), while well compensated relative to average overall wages, are poorly compensated relative to their peers in specialty services. The ratio of average annual income for a specialty physician compared to a PCP in the United States was 1.6 in 2003–2004 (Fujisawa and Lafortune, 2008). By 2017, the median compensation in radiology, procedural, and surgical specialties had an almost twofold difference compared with primary care (Doximity, 2019; MedPAC, 2019). While the difference is less, primary care nurses and physician assistants also make less than those in other specialties (AAPA, 2020; Nurse.org, 2020).

As this chapter will describe, this valuation is not derived from market-based negotiations governed by the laws of supply and demand. Rather, it starts with the idiosyncratic process by which Medicare values services, which attempts to account for training, operational costs, and professional risks. This approach, however, places little intrinsic value on promoting health or keeping people healthy. Rather, it is skewed toward procedures, tests, and specialists over relationships, holistic consideration of the individual and their diagnoses, and population health. Usually, the sicker the

patient and the more technical care they receive, the more clinicians are paid. In addition, the U.S. health care system is focused, and paid, on the notion of treating illness rather than on maintaining health. Technology-enabled services oriented primarily to diagnosing and treating advanced disease draw higher prices than reimbursement for clinician time spent with patients and their families.

Money is but one factor affecting clinicians’ decisions, yet payment methods clearly affect whether, how, and how much care they provide (Quinn, 2015). Because they are more likely to provide services with greater returns, relative prices affect use and the mix of services provided. Indeed, when prices change, this has measurable effects on the number and mix of services provided to patients (Clemens and Gottlieb, 2014; Cromwell and Mitchell, 1986; Gruber et al., 1998; Hadley, 2003; Rice, 1983). Examples include hospital length of stay, diagnostic imaging in physician offices, home health care visits, coordination between physicians and hospitals, the volume and mix of services delivered, and which drugs are used for treatment (Bodenheimer, 2008; Coulam and Gaumer, 1991; GAO, 2012; Jacobson et al., 2010; Schlenker et al., 2005; Schroeder and Frist, 2013).

The results of primary care’s devaluation are not surprising. The portion of total health care expenses devoted to primary care in the United States is at or lower than most other countries (Koller and Khullar, 2017; Phillips and Bazemore, 2010), and evidence suggests that it is declining (The Larry A. Green Center and PCC, 2020). One result is that retaining seasoned primary care clinicians has become challenging. Moreover, when faced with the prospect of medical education debt, more limited future financial remuneration, and lower perceived social and professional status, many medical students opt for specialty professions over primary care. The COVID-19 pandemic has further distressed the primary care profession by limiting in-person visits, driving a significant number of practices to close (Basu et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2020).

A health care system oriented more to primary care would result in a healthier population (Basu et al., 2019) with more consistent access to primary care and potentially a more equitable distribution of health care (Dwyer-Lindgren et al., 2017; Friedberg et al., 2010; Macinko et al., 2007). As recently reiterated by The Commonwealth Fund’s 2020 Task Force on Payment and Delivery System Reform (2020), the nation will only achieve these goals with changes in how and how much primary care is paid (Zabar et al., 2019).

How Payment Is Rendered

How payment is rendered influences the behavior of both clinicians and care-seekers in primary care. Payment methods matter because of the

incentives they create and the actions they reward. The historically dominant method of FFS payment encourages a focus on providing and receiving individual, billable services. Generally, the unit of service and analysis is the short office visit. While FFS is considered to promote access and accountability (Dowd and Laugesen, 2020; Kern et al., 2020), it discourages other team members who may not be able to bill for their services from providing care. It also disincentivizes the primary care team from focusing on non-billable services, outside of a brief office visit, that may have beneficial effects on the health of individuals or a population, such as identifying and educating people with chronic disease (Berenson and Goodson, 2016).

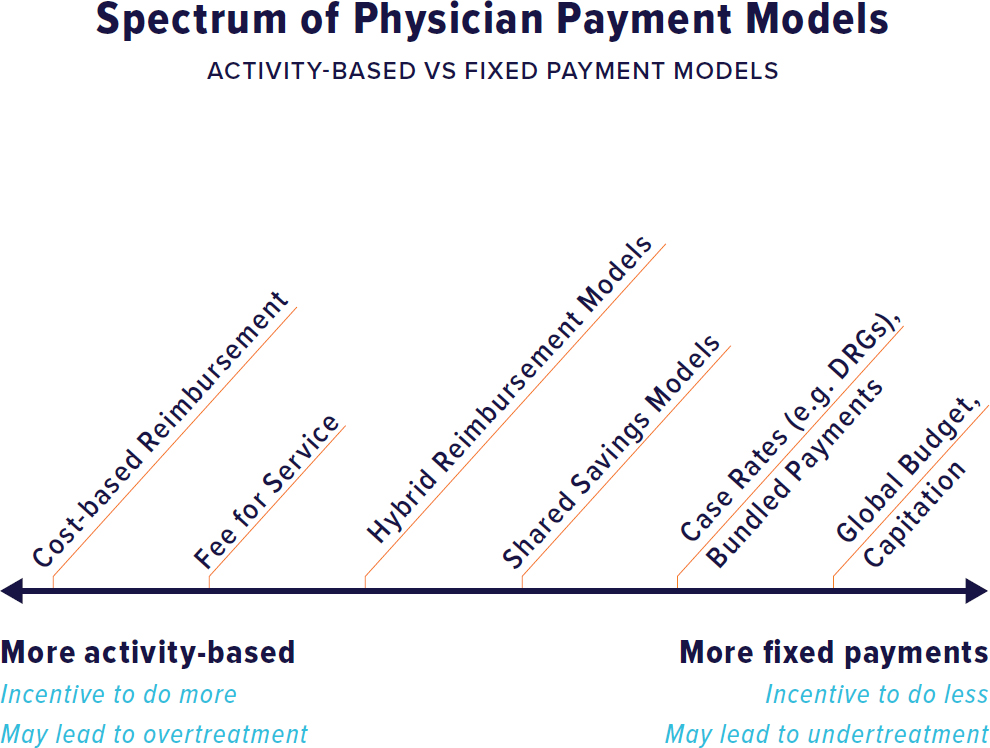

The Spectrum of Physician Payment Models

Theory and evidence show that payment methods have distinctive effects on clinician behavior. Generally, the models fall along a spectrum according to the unit of payment, such as FFS (which pays for each individual service provided) or a bundled payment (which pays for a group of services or a specific period) (see Figure 9-1). On the one hand, concerns about stinting in providing care dominate when clinicians bear financial risk in a bundled payment model, because health care use can be unpredictable. On the other hand, concerns about overtreatment dominate when the financial risk is on payers, such as in FFS, where the insurer pays a given fee for each service. Most research shows empirical results in parallel with theory: FFS encourages use, and capitation—a payment model that provides a fixed amount of money per patient per unit of time paid in advance to the physician for the delivery of health care services, whether or not that patient seeks care and how much it costs—discourages resource consumption; productivity-based pay encourages and capitated payments undermine productivity (Berenson et al., 2020; Hellinger, 1996; Kralewski et al., 2000).

All payment methods have inherent incentives, both good and bad, that cannot be eliminated even with optimal design (Robinson, 2001). Their perverse effects can be attenuated to some extent through design, but even the most sophisticated mechanisms merely diminish the incentives for overtreatment, undertreatment, and other undesirable behaviors. Blended methods, using the best attributes of each, outperform pure FFS and pure capitation in supporting primary care (Berenson et al., 2020; Ellis and McGuire, 1990; Robinson, 2001).

Simplicity is a virtue for several reasons when it comes to designing and implementing payment models. The administrative costs of designing, negotiating, implementing, disbursing, disputing, and adjudicating complex payment methods are high. Simplicity is especially important in the multi-payer U.S. context because adoption of payment models is undermined when physicians face different policies and incentives from multiple

NOTE: DRG = diagnosis-related group.

insurers. Simplicity also supports transparency for all stakeholders, including clinicians, patients, and policy makers.

HISTORY OF PRIMARY CARE PAYMENT

As part of an effort to manage the rising costs of health care and ensure the solvency of Medicare, Congress enacted the Medicare prospective payment system for hospitals in 1983 (Altman, 2012). Instead of paying hospitals for each service delivered, Medicare pays a set fee per stay based on the diagnosis and treatment path. This change incentivized hospitals to reduce length of stay and shift more care to outpatient settings. Although it was not intended to impact primary care, it had many downstream consequences.

In the late 1980s, rising and varied physician-set prices and the widening gap between generalist and specialist incomes led Congress to establish the resource-based relative value scale to set prices for physician services, which account for about 20 percent of Medicare spending (CMS, 2019b). The Physician Fee Schedule (PFS), implemented in 1992, was designed to

be built around a scientific measurement of work and practice expenses (Hsiao et al., 1993), with physician work accounting for around 50 percent of the total relative value unit. Changes to the original measures during the implementation process resulted in a fee redistribution to PCPs about half as large as that projected by the original estimates (Berenson, 1989).

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA),1 passed in 2010, included two provisions to adjust payments to PCPs upward: (a) a 10 percent incentive payment under the Medicare primary care incentive payment (PCIP) for 5 years and (b) raising the Medicaid primary care payment rates up to at least 100 percent of the Medicare rate for 2 years (Davis et al., 2011; Mulcahy et al., 2018). Federal funding for this Medicaid increase expired in 2014, but as of 2016, 19 states had continued this “fee bump” in whole or in part (Zuckerman et al., 2017) and some have called for payment equity between Medicaid and Medicare to be a permanent strategy to improve access and equity for children (Perrin et al., 2020). Not all PCPs were eligible for the PCIP because the criteria were based on meeting a 60 percent threshold of allowed charges for specific ambulatory evaluation and management codes. Some family physicians, particularly in rural areas, perform procedures and provide care in hospitals such that they did not meet the threshold (The Lewin Group, 2015).

The PCIP program had a modestly positive impact on the availability and use of primary care services in Medicare. An early analysis found the almost 75 percent Medicaid rate increase improved primary care appointment availability for enrollees with participating clinicians without generating longer wait times (Polsky et al., 2015; Zuckerman and Goin, 2012). However, a recent analysis concluded the payment increase had no association with PCP participation in Medicaid or on Medicaid service volume (Mulcahy et al., 2020).

Medicare has also added supplemental primary care services to the PFS to improve quality (Berenson et al., 2020).2 An additional focus in the 2019 and 2020 PFS updates was liberalizing payment for a variety of relatively new telehealth codes. Given these codes’ complexity and stringent requirements, uptake has been inconsistent, particularly by small practices (Carlo et al., 2020; Dewar et al., 2020; Reddy et al., 2020). Despite barriers to adoption, including billing and workflow adjustments, uptake is increasing,

___________________

1 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 111-148 (March 23, 2010).

2 These include covering certification of home health and hospice services, managing care transitions from hospital to the community, managing care for patients with chronic conditions, advance care planning, managing care for patients with cognitive impairment and behavioral health conditions in collaborative arrangements with behavioral health professionals, and providing add-on payments for visits that last at least 31 minutes or prolonged management services conducted before and/or after direct care.

improving value to beneficiaries and the program while increasing revenue to practices (Berenson et al., 2020).

In 2019, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, providing additional payments to organizations participating in alternative payment models and financially rewarding or penalizing clinicians based on quality measures, promoting interoperability, and improvement activities (PAI, 2020). In this zero-sum game, where bonuses for the highest performers come from penalties of lower-performing practices, research has shown that independent practices—those that are not part of a larger system—and safety net practices are more likely to have lower performance and suffer financially (Colla et al., 2020).

PRIMARY CARE PAYMENT TODAY

Financing health care in the United States is complex, with health care organizations receiving revenue from multiple sources: public payers (directly and also indirectly through contracted insurers), commercial insurers, self-insured employers (directly and also through their administrators), and directly from patients. In addition, separate systems exist for veterans and active-duty military families. Oversight authority is divided between private and public payers and between state and federal regulators. This complexity is a contributing factor to the fragmentation of care and why implementing changes to payment models is difficult. In 2017, family physicians reported that their patient panel was 41 percent private insurance, 28 percent Medicare, 18 percent Medicaid, and 7 percent uninsured. Since 2012, notable shifts have taken place in the payer mix for family physicians, with Medicare and Medicaid comprising a greater percentage (AAFP, 2017a). Among pediatricians, that payer mix looks different, at 49 percent Medicaid, 46 percent private insurance, and about 4 percent uninsured (AAP, 2019).

Primary care spending accounted for 6.5 percent of total U.S. health care expenditures in 2002 and 5.4 percent in 2016 (Martin et al., 2020). The proportion was even lower among Medicare FFS beneficiaries, with primary care representing 2.12–4.88 percent of total medical and prescription spending in 2015 (Reid et al., 2019). Medicare Advantage beneficiaries had higher rates of primary care visits and lower costs for these services, but the differences were not substantial (Park et al., 2020). Among commercially insured groups, children had the highest primary care spending as a share of their total health care spending, with 20.33 percent in 2013 and 19.54 percent in 2017, and individuals aged 55–64 years had the lowest, with 7.25 percent in 2013 and 6.33 percent in 2017 (Reiff et al., 2019).

Across payers in 2013, FFS was the dominant method: nearly 95 percent of all physician office visits, with the remaining 5 percent via

capitation. The exact numbers varied by geography and payer (Zuvekas and Cohen, 2016). In 2016, 83.6 percent of practice revenue was FFS, while bundled payments accounted for almost 9 percent, pay-for-performance and capitation made up close to 7 percent, and shared shavings made up only 2 percent (Rama, 2017).

The traditional Medicare program still mainly pays primary care through FFS, with modest adjustments for quality and efficiency (MedPAC, 2020a). A quarter of beneficiaries fall under an alternative payment model (such as an accountable care organization [ACO], described below). In 2019, 34 percent of beneficiaries were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan (MedPAC, 2020b), where payment for primary care services varies by plan but is generally FFS and anchored to the Medicare fee schedule (Trish et al., 2017). About 10 percent of beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage are in a plan that passes on global financial risk to clinician teams (Galewitz, 2018).

In Medicaid, states have broad flexibility to determine payments for physician services. While 81 percent of enrollees are in managed care plans, the majority of Medicaid spending occurs under direct state FFS arrangements (MACPAC, 2020). Medicaid physician fees are well below that of fees for Medicare and private payers: only roughly 54 percent of Medicare rates for primary care services (MACPAC, 2013). These lower rates are thought to negatively impact physician participation in Medicaid (Cunningham and May, 2006; Decker, 2012; Holgash and Heberlein, 2019).

State Medicaid programs use different types of managed care arrangements: comprehensive risk-based managed care (35 states), primary care case management (7 states), or a combination of the two (5 states). Some states carve out specific services from their managed care arrangements such as oral health, institutional care, or transportation (Hinton et al., 2019; MACPAC, 2011). Sixty-nine percent of Medicaid enrollees in 2018 received their benefits though a comprehensive risk-based arrangement (KFF, 2020). In primary care case management, enrollees have a designated primary care team paid a monthly case management fee to assume responsibility for care management and coordination. Individual clinicians are not at financial risk; they continue to be paid on an FFS basis for providing covered services. In some cases, financial incentives for both primary care teams and the care management entity are added.

In risk-based arrangements, Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) are paid a capitation rate that is calculated based on the state’s FFS rates. The MCO, in turn, contracts with health care organizations through a series of privately negotiated, proprietary arrangements. The MCO is responsible for assembling a network of clinicians that meets state access requirements based on minimum standards set by CMS, which also maintains separate network access standards for Medicaid FFS programs.

The access standards for Medicaid MCOs were promulgated by CMS under its Medicaid Managed Care Rule in 2016, but none are specific to primary care. Prior to the 2016 rule, inadequate enforcement of Medicaid access policies was the source of dozens of suits against states (Rosenbaum, 2009, 2020). In 2020, CMS eliminated an access standard for the time and distance traveled to access a clinician, only requiring states to set a quantitative minimum access standard, such as minimum clinician-to-enrollee ratios; a minimum percentage of contracted clinicians that are accepting new patients; maximum wait times for an appointment; or hours of operation requirements (BPC, 2020; CMS, 2020e).

More than half of managed care states (21 of 40) set a target percentage in their contracts for the percentage of payments, network clinicians, or plan members that must be paid via alternative payment models in fiscal year 2019 (Hinton et al., 2019). Most plans use FFS with incentives or bonus payments tied to performance measures. Fewer plans reported using bundled or episode-based payments or shared savings and risk arrangements.

Commercial health insurance consists of employer-sponsored coverage and individual insurance. Insurers and administrators assemble provider networks through proprietary confidential contracts. Analysis of multiple sources indicates that commercial insurers pay on average 143 percent of Medicare rates for physician services, with considerable variation by specialty type (Lopez et al., 2020). Codes most frequently billed by PCPs were paid at 107 percent of Medicare (Trish et al., 2017). This disparity in payments relative to Medicare likely reflects greater negotiating leverage for specialty physicians. More than half of commercial contract payments use FFS without any quality or performance bonuses (HCPLAN, 2019).

Findings for Primary Care Today

- Primary care makes up a small and declining proportion of medical spending.

- FFS is the dominant payment mechanism for primary care clinicians.

- Compared to Medicare, Medicaid pays substantially less for primary care services and commercial insurers slightly more.

- Medicaid determines payment sufficiency through the ability of states and managed care contractors to maintain adequate networks of clinicians. Federal oversight of these standards is not specific to primary care, and, while they were already inadequate, they have recently been further relaxed.

- Commercial insurers pay specialty physicians more relative to Medicare than they pay PCPs.

REFORMING PAYMENT TO PRIMARY CARE

In this section, the committee presents a spectrum of options for improving payment for primary care to better meet people’s needs. These options are not mutually exclusive, and it will likely be necessary to employ multiple levers to produce the changes necessary to support primary care.

- Option 1 builds incrementally on the existing PFS to value primary care services more accurately.

- Option 2 discusses overarching models to blend FFS and fixed payments.

- Option 3 discusses global payment models for practices prepared to take on further financial risk.

- Option 4 discusses creating a societal goal for the proportion of health care spending that goes to primary care.

Option 1: The Medicare Physician Fee Schedule and the Relative Value Scale Update Committee

While Medicare accounts for 20 percent of national health spending (KFF, 2019), the relative prices set by the PFS have a profound effect on professional prices beyond Medicare beneficiaries. Three-quarters of the services physicians billed to commercial insurers are pegged to Medicare’s relative prices (Clemens et al., 2015), and TRICARE, the health care program for uniformed service members, also uses the Medicare PFS. Many state Medicaid and state workers compensation programs use the Medicare rates as a benchmark. In addition, many alternative payment models are based on spending projections that use the PFS, and payers use shadow prices from the PFS to calculate capitation rates.

The Role of the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC)

Shortly after CMS implemented the Medicare PFS, the American Medical Association created the RUC and offered the committee’s expertise to the Health Care Financing Administration, CMS’s predecessor. The RUC selects physician procedures for review and determines the value of services relative to other physician services for three categories of activity: physician work, practice expense, and malpractice risk. The RUC passes the resulting numerical assessments on to CMS, which can accept or modify recommendations and then convert them into an entry on the PFS using a geographic adjustment and inflation multiplier. Historically, CMS has deferred to nearly all the RUC’s recommendations, accepting them unaltered 87.4 percent of

the time between 1994 and 2010. On average, RUC-recommended work values were higher than final CMS values (Laugesen et al., 2012).

Today, the RUC comprises 31 physicians and 300 advisors representing medical specialties. Primary care has one rotating seat and three seats appointed by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), the American College of Physicians (representing internal medicine), and the American Academy of Pediatrics. Two seats also rotate between internal medicine subspecialties. Of the 31 physician seats, only one each is dedicated to child health and geriatrics (AMA, 2016).

There are reasons to question the accuracy and independence of the RUC process, including documented voting alliances in the RUC among proceduralists that often distort the equitable allocation of valuing work (Laugesen, 2016). Researchers working with CMS and the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation have gathered evidence that the PFS’s time estimates for clinician work are inflated (MedPAC, 2018b; Merrell et al., 2014; Zuckerman et al., 2016), suggesting a bigger gap between estimated and actual times for surgical and procedural services than office visits, especially those occurring in primary care (McCall et al., 2006; MedPAC, 2018b). The available evidence suggests that surgical services are overvalued, while primary care visits and services are largely undervalued (CMS, 2019a; Reid et al., 2019).

Inaccuracies in relative pricing along with CMS acceptance of most RUC recommendations have contributed to the differences in compensation across specialties, the distribution of physicians across specialties, inefficient distortions in use, and inadequate beneficiary access to undervalued services, as described above (MedPAC, 2018b; Nicholson and Souleles, 2001). These deficiencies in the RUC process compound over time because changes to Medicare’s fee schedule must be budget neutral. As a result, primary care services generally, and evaluation and management codes specifically, have become passively devalued in the PFS as their relative prices fall as a result of other service prices (including new technologies) increasing. A variety of factors interplay to cause this devaluation:

- For procedure-based services, work time often falls as physicians become familiar with the service and technology improves. However, work relative value units (RVUs) for these services often are not re-evaluated (MedPAC, 2006). Evaluation and management services consist largely of activities that require specified clinician time.

- Requests for new codes or refinement are initiated by specialty societies, and refinement generally results in increases (Laugesen, 2016). New technologies and methods of diagnosis and treatment

- can create pathways to higher relative values, compared to visits, which have few new technologies (Zuckerman et al., 2015).

- Procedural, task-driven work may lend itself more easily to judgments of physician work units, which are composites of time, mental effort, judgment, technical skill, physical effort, and psychological stress. Measurement may be harder in evaluation and management services with a broad range of clinical issues, less defined temporal sequences, and a more nonlinear workflow, as found in the management of chronic conditions in primary care (Katz and Melmed, 2016; Laugesen, 2016). Furthermore, primary care has involved increasing complexity over time, at the level of different organ systems, individual factors, societal variables, and population dynamics. It is difficult to measure the continuity, comprehensiveness, coordination, trust, personal connection, and personal accessibility necessary to provide high-quality primary care (Shi, 2012).

- Under budget neutrality, an increase in units for the large number of evaluation and management visits would mean relative prices fall for everything else, making the RUC less likely to recommend these changes. Most evaluation and management codes are passed in the RUC below the 25th percentile of the range of clinician responses regarding work time, whereas procedures typically end up between the 25th and 50th percentile of survey responses (Laugesen, 2016).

- Documented voting alliances in the RUC among proceduralists often distort the equitable allocation of valuing work (Laugesen, 2016).

Thus, because the fee schedule is budget neutral and the phenomena described above are routine, primary care services have become passively devalued. For example, the total RVUs for a Level III office or outpatient visit for an established patient (HCPCS 99213), the most frequently billed office or outpatient visit, declined slightly from 2.14 in 2013 to 2.06 in 2018 (MedPAC, 2018b). This devaluation is reflected in a widening gap in pay between primary care and specialists. Data from the Medical Group Management Association indicate that from 1995 to 2004, the median income for PCPs increased by 21.4 percent, while that for specialists increased by 37.5 percent (Bodenheimer, 2006). In 2017, median compensation for nonsurgical, procedural specialists, surgical specialties, and primary care was $426,000, $420,000, and $242,000 (MedPAC, 2019), respectively. This compensation gap is associated with reduction in medical student choice of primary care careers and with shifting hospital graduate medical

education priorities away from primary care (COGME, 2010; Phillips et al., 2009; Weida et al., 2010).

Recent Reforms

Several effective steps have been taken in the last decade, including revising misvalued codes, temporarily increasing the primary care fee, and adding new primary care codes. Nonetheless, the definition and conceptualization of physician work inherent in the PFS do not support the committee’s conceptualization of high-quality primary care.

For the last decade, CMS and the RUC have identified and reviewed “potentially misvalued services,” including codes associated with fast use growth or services that have not been reviewed since the PFS was implemented. The Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 20143 and Medicare Access and CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) Reauthorization Act of 20154 provided CMS with new powers to change misvalued codes and collect data to evaluate the PFS. The law expanded the number of codes that would potentially be evaluated, creating a new target for relative value adjustments, with a savings target of 0.5 percent of expenditure every year between 2017 and 2020 (Laugesen, 2016). A recent survey of the RUC process resulted in a major upward revision in the 2021 Medicare PFS for fees for office visits (CMS, 2020d). CMS endorsed the RUC recommendation for the two most commonly billed office visit codes: a 34 percent increase for code 99213 and a 28 percent increase for 99214.

CMS remains limited, however, by the lack of current, accurate, and objective data on clinician work time and practice expenses (GAO, 2015; Mulcahy et al., 2020; Wynn et al., 2015; Zuckerman et al., 2016). As a result, CMS continues to depend on a RUC process that has drifted away from science-based estimates toward interest group input. This drift is facilitated because complexity and lack of transparency effectively mask payment policy. The complexity of the PFS and its determinants, paired with the lack of resources at CMS, has led to a situation where physician societies have informational advantages and leverage them to achieve higher valuations (Laugesen, 2016; McCarty, 2013; Shapiro, 2008).

CMS and other policy makers have little recourse to change the RUC structure or processes. As a private organization, the RUC has an important voice in the policy process and substantial autonomy to determine how it chooses its valuation practices. Many have noted that without more oversight or coordination of a fair arbitration process, the relative value scale

___________________

3 Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014, Public Law 113-93 (April 1, 2014).

4 Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, Public Law 114-10 (April 16, 2015).

was bound to be biased toward specialty care (Berenson and Goodson, 2016; Laugesen et al., 2012).

However, the committee sees no regulatory or institutional barrier to CMS establishing its own parallel capacity to independently value physician services that aligns better with its stated organizational goals to move toward value-based, accountable payment and away from the misvalued PFS. In fact, it is hard to imagine that it could do so in the absence of an independent valuing mechanism within or external to the agency, such as the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC).5 Establishing such a capacity will require allocating a relatively modest level of resources and staff and would not prevent the RUC from continuing to make its recommendations to CMS and other entities. However, by having an additional resource to evaluate and compare its own estimates with that of the RUC and others, CMS would be able to more adequately and fairly price primary care services in a way that accounts for their complexity and value to patients and society.

Altering the Fee Schedule to Accomplish Policy Objectives

Direct changes to relative prices could include a payment increase for ambulatory evaluation and management services, such as the change implemented in January 2021, or freezing rates for these services while reducing others. In 2015, MedPAC recommended establishing per-beneficiary payments for primary care clinicians to encourage care coordination, including the non-face-to-face activities that are a critical component of care coordination. MedPAC recommended setting the per-beneficiary payment at 10 percent of primary care spending, which at that time would have meant an annual payment of $28 per patient with no beneficiary cost sharing. To be budget neutral, this funding level would have required reducing fees for non–primary care services in the PFS by 1.4 percent (MedPAC, 2015). A hybrid reimbursement approach such as this is discussed more below.

In its June 2018 report, MedPAC modeled a 10 percent payment rate increase for evaluation and management services. In 2019, a 10 percent increase would have raised annual spending for ambulatory evaluation and management services by $2.4 billion. To maintain budget neutrality, payment rates for all other PFS services would be reduced by 3.8 percent (MedPAC, 2018b). Other options to offset a payment increase for ambulatory evaluation and management codes include automatic reductions to

___________________

5 MedPAC is a non-partisan legislative branch agency that provides the U.S. Congress with analysis and policy advice on the Medicare program. Additional information is available at www.medpac.gov (accessed February 27, 2021).

prices of new services after their introduction or automatic reductions in services with high growth rates (MedPAC, 2018b).

In summary, the Medicare PFS is not well designed to support primary care. It is oriented toward discrete, often procedural, technical services with defined beginnings and ends, the antithesis of high-quality continuous primary care. Some have gone so far as to say that the RUC and the PFS have led to more procedures, the recruitment of more physicians into the procedure-oriented specialties, the underrepresentation of primary care in the workforce, the under-provision of primary care, and the consolidation of primary care practices into larger delivery systems (Berenson and Goodson, 2016; Calsyn and Twomey, 2018; Laugesen, 2016).

Findings for Option 1

- The relative prices set by the Medicare PFS have profound effects on prices paid by Medicaid, commercial payers, and others. The RUC exerts significant influence on the relative prices assigned by CMS.

- The RUC, together with the structure of the PFS, have resulted in systematically devaluing primary care services relative to other services and its population health benefit, reflected in large and widening gaps between primary care and specialty compensation.

- The widening compensation gap between primary care and other physician specialties is associated with reductions in medical trainees’ likelihood of choosing primary care careers and with hospitals’ graduate medical education training priorities.

- With adequate resources and leadership, CMS has the authority to address these weaknesses and internalize the functions of the RUC (data collection and valuation tools) to generate payment levels aligned with high-quality primary care.

Option 2: Hybrid Reimbursement Models

A second option for increasing and reforming payment to primary care is to mix FFS payment mechanisms with lump-sum or per-person payments to encourage team-based, technology-enabled advanced primary care.

Patient-Centered Medical Home Model

Over the past 15 years, implementation of advanced primary care in the United States has focused largely on the hybrid patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model. Early PCMH models showed promising results in

terms of reducing spending and avoidable use, especially among the chronically ill (Maeng et al., 2016).

Commercial payers began to sponsor limited tests of these models within their care networks, usually with small care management fees on top of FFS. By 2010, these tests encompassed more than 14,000 physicians in 18 states caring for almost 5 million patients (Bitton et al., 2010), but they were hampered by the low levels of care management fees, often under $5 per patient per month, and a lack of multi-payer participation. The early results of studies on PCMH effects on total spending were mixed (Jackson et al., 2013; Sinaiko et al., 2017). These evaluations rarely factored the cost of practice transformation or the provision of care management fees into the analysis.

As the PCMH model spread, payers provided more substantial care management fees, multi-payer participation increased somewhat, and payer-initiated PCMH models began to include shared savings incentives (Edwards et al., 2014). The total amount of money, and transformation resources in the form of facilitation, generally increased. Nonetheless, FFS continued to be the mainstay of payment, and robust multi-payer involvement was the exception, not the norm. The cost effects of these PCMH initiatives continued to be mixed, though quality and patient experience were more often improved (Jackson et al., 2013; Kern et al., 2016; Lebrun-Harris et al., 2013; Sinaiko et al., 2017).

However, more recent research on PCMH outcomes from nearly 6,000 practices in 14 states found reductions in total expenditures of more than 8 percent after up to 9 years of implementation, as well as significant decreases in emergency department utilization and outpatient care (Saynisch et al., 2021). Emergency department reductions were highest among practices that offered electronic access, suggesting that the choice of adopted capabilities is important.

The PCMH model has also been implemented for pediatric populations. Integrated Care for Kids, a child- and family-centered integrated delivery care model, is one example with a matched state payment model for children insured by Medicaid or CHIP (see Chapter 5 for more detail).

Comprehensive Primary Care Model

To test a multi-payer approach to primary care transformation at scale, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) launched the Comprehensive Primary Care (CPC) model as a 4-year, multi-payer demonstration in 2012. CPC provided population-based care management fees and shared savings opportunities, on top of standard FFS, to nearly 500 participating primary care practices in seven regions as a means of supporting the provision of a core set of five “comprehensive” primary

care functions (CMS, 2020a). Regions were selected based on the ability of their payer partners to provide participating practices with at least 60 percent of combined revenue. CPC showed mixed results on the cost and quality outcomes assessed in its evaluation. The growth rate in overall FFS expenditures was reduced for attributed beneficiaries, though the decrease was not enough to offset the care management fees (Peikes et al., 2018). In addition, those fees were not sufficient to enable upfront and long-term investments in staff. Though practice quality improvements as measured through claims were modest, an analysis of electronic clinical quality measures (used by practices themselves to measure improvement) showed significant gains compared to benchmarks established during the initiative (LaBonte et al., 2019).

Comprehensive Primary Care Plus Program

CPC was a precursor to the CPC+ program launched in 2017. CPC+ is a national multi-payer advanced primary care model that aims to strengthen primary care through regionally based, multi-payer payment reform and care delivery transformation (Burton et al., 2017). It is active in 18 regions, with more than 50 payers and more than 3,000 participating practices serving more than 3 million Medicare beneficiaries and an estimated 15 million people overall (CMS, 2020b). CPC+ includes two practice tracks with incrementally advanced care delivery requirements and payment options and has three major payment elements: (1) a risk-adjusted care management fee per beneficiary that is paid quarterly and not visit based; (2) performance-based incentives paid prospectively with retrospective reconciliation, with performance measures that include patient experience, clinical quality, and use; and (3) payment under the PFS. In Track 1, PFS payment continues as usual along with the care management fees and performance-based payments, but in Track 2, PFS payments are reduced and shifted into a CPC payment.

CPC+’s first evaluation6 focused on Medicare FFS enrollees in 2,905 practices that started CPC+ in 2017. The median care management fees per practitioner in the first year equaled $32,000 in Track 1 and $53,000 in Track 2, with CMS providing the most fees relative to other participating payers. Other payers were slower to adopt the reduced PFS payments and partially capitated payments in Track 2. In the first year, 71 percent of Track 2 practices opted for the lowest FFS reduction of 10 percent in exchange for capitated payments; only 16 percent of CPC+ Track 2 practices,

___________________

6 This reflects available evaluations at the time of writing. The reader should refer to https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/comprehensive-primary-care-plus (accessed February 27, 2021) for updated evaluations.

or roughly 8 percent of all participants, opted for a 40 or 65 percent reduction in FFS in exchange for larger capitated payments. As expected, CPC+ in its first year had small effects on quality of care and health care spending, and the care management investments were larger than any cost savings.

Despite the investments in care management, data feedback, and learning support, participating practices also expressed challenges implementing care delivery requirements, though system-owned practices and those with a robust health information technology infrastructure found it easier to identify the resources for practice transformation and manage reporting requirements. Commercial insurer participation in the CPC+ model has persisted, indicating they perceive value in the model. There are also non-peer-reviewed analyses of multi-payer projects in Arkansas, Ohio, and Oregon that show more promising performance for commercially insured people and improvements over time (Bianco et al., 2020; Brown and Tilford, 2020; Dulsky Watkins, 2019).

Challenges to Implementing Hybrid Reimbursement Models

Most PCMH-like primary care transformation efforts implemented by individual payers have used hybrid payment methods largely based on FFS and struggled to provide the financial resources to cover transformation costs or the ongoing cost of maintaining integrated team-based care. Some commercial payers, such as the Capital District Physicians’ Health Plan (CDPHP) in New York and the Hawaii Medical Service Association, have moved further to structure payments for primary care practices around a risk-adjusted primary care capitation model. An evaluation of the CDPHP model showed some pharmacy cost savings and use declines in people with chronic conditions but no overall cost savings (Salzberg et al., 2017). An initial assessment of the Hawaii program found improvements in quality but did not assess cost or use changes (Navathe et al., 2019).

As with payer-specific hybrid payment models, it was likely difficult for practices to change their overall structure when one payer offered risk-adjusted capitation for 10 to 20 percent of patients but FFS contracts constituted the rest. With the advent of large multi-payer initiatives, such as CPC+, this dynamic is changing, as payers in some regions are starting to increase available capital to practices and change payment for a plurality, if not majority, of patients in a practice. Nonetheless, most U.S. primary care practices, even those involved in PCMH efforts, are not paid substantially extra for these efforts.

Poorly funded incremental PCMH efforts across practices have diluted the effects of the limited capital invested in them, and until recently, this capital has not been explicitly tied to reductions in total cost of care. The majority of payer-initiated PCMH and advanced primary

care demonstrations have shown mixed or no effects on total cost. The lack of spending reductions has limited further investment in augmented PCMH or advanced primary care models, whose high ongoing staff and transformation costs are well documented. Without a substantial source of new, predictable, and sustainable revenue from multiple payers to maintain and expand new services, practices find it difficult to maintain focus on overlapping practice transformation aims, including quality improvement, team formation, chronic care coordination, and patient engagement. Thus, minimal investments, initiative overlap, and an underlying focus on visit volume impede the ability to focus on reducing total spending, which is difficult when primary care practices drive small fractions of spending themselves and have incomplete control over where and when their patients utilize care.

Nonetheless, the literature on impact of payment reform on total spending remains mixed and may depend on organizational and patient characteristics (Veet et al., 2020). For example, some integrated delivery systems have improved outcomes, and low-income patients have improved clinical outcomes (van den Berk-Clark et al., 2018). Many payer-reported efforts have suggested savings (Jabbarpour et al., 2017), but most peer-reviewed published analyses have been more widely divergent or null in their findings (Jackson et al., 2013; Sinaiko et al., 2017). One study with a 6-year observation period and another that took place after up to 9 years of implementation both found significant savings (Maeng et al., 2016; Saynisch et al., 2021). A key area of overlapping conclusion is that potential savings are concentrated in patients with multiple comorbidities and chronic conditions, where regression to the mean is possible.

This imperative to demonstrate short-term health care cost savings serves as a key challenge to child health–focused primary care models, as high-cost pediatric patients make up a much smaller proportion of the population. For example, just 5 percent of children account for about 50 percent of Medicaid spending for children (Berry et al., 2014). Most often, health care savings realized by primary care transformation may result as children and adolescents age into healthier young adults, with healthier behaviors (e.g., lower smoking rates, higher immunization rates) and fewer chronic illnesses (less obesity, lower rates of depression). Savings may also be realized outside of health care, in education (greater graduation rates, less need for special education services) (Zimmerman and Woolf, 2014), the workforce, and the criminal justice system (Wen et al., 2014). These, of course, are not costs that are considered in time-limited evaluations of primary care transformation. Thus, a recent review of child-focused ACOs concluded that the area of child health requires specific payment models to account for these issues (Perrin et al., 2017).

Ten years of experience with CMMI hybrid reimbursement models has generated some key lessons for future primary care model development (Peikes et al., 2020):

- Though participating practices valued the care delivery innovations, they often struggled to find the time or resources necessary to fully implement desired changes, even with multi-payer models.

- Busy primary care clinicians need education about what they are required to implement and why. They also require simplified and harmonized reporting requirements across payers to reduce administrative burden on practices.

- Practices need some flexibility from payers to adapt payment models to their circumstances.

- Involving an extended care team other than those in primary care can enhance model impact.

- The redesign of care can take time to yield impact.

Layering care management fees and shared savings on a largely unchanged chassis of FFS does not drive robust and focused practice change to reduce expensive specialty and hospital-based use; practices largely continue to operate within the confines of FFS, visit-based mentality (Bitton et al., 2012). Alternative payment models need to have stronger incentives to counter FFS, and multi-payer participation with more substantial shifts away from FFS toward risk-based contracting can help achieve this (Burton et al., 2018; Martin et al., 2020). However, many practices may not be immediately able to take on complex risk. Payments need to be clearly defined, relatively simple, and transparent. Data and feedback on performance are necessary, but they must be salient and actionable, and training on using data effectively may be necessary for model participants.

Particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, attention has focused on another advantage to partially capitated models: they ensure a steady and predictable cash flow in times of severe service disruption (Phillips et al., 2020). To the extent that the declines of pandemic-induced visit volumes remain, greater implementation of hybrid payment arrangements would forestall the closure of primary care practices or their absorption into larger, more expensive health systems with no corresponding improvement in service value.

Findings for Option 2

- FFS models discourage successful engagement of primary care practices in structure and process improvements.

- Hybrid payment models in support of advanced primary care mitigate FFS incentives for increased use and provide resources for team-based care and non-PFS services, though this produces modest to no reductions in spending and use in the short term.

- With adequate time, hybrid reimbursement models show improvements in care and reductions in use, particularly for people with multiple complex chronic conditions.

- The likelihood of practice improvement increases in markets where one payer has a large market share or when multiple payers align.

Option 3: Broad Risk-Sharing Models

The types of organizations delivering primary care vary greatly, as discussed throughout this report. In 2018, health systems employed nearly half of primary care clinicians, and this number continues to grow (Abelson, 2019), with potential acceleration from the COVID-19 pandemic. In health care systems, primary care clinicians are often employees and operate under contracts established by the system at large. In those instances, where health care organizations have greater capability and often experience with financial risk, they can assume accountability for overall use and spending. Referred to collectively as “risk sharing”—where risk is the probability of the assigned population using medical services—practices can assume risk accountability in their own contracts, form new entities to participate in risk-sharing models, or participate as part of a larger medical group or integrated delivery system.

Accountable Care Organizations

ACOs are groups of clinicians participating in capitated or shared-risk contracts paired with incentives for quality performance. CMS manages several ACO programs7 that have implications for primary care payment, and many commercial payers have ACO programs as well (Peiris et al., 2016). In 2019, there were 1,588 existing public and private ACO contracts covering almost 44 million lives (Muhlestein et al., 2019). When an ACO succeeds in both delivering high-quality care and spending health care dollars more wisely, it will share the savings. Some ACO contracts also include shared risk if spending exceeds targets (Peck et al., 2019). Under an ACO

___________________

7 CMS and CMMI manage multiple types of ACOs, including the Medicare Shared Savings Program, the ACO Investment Model, and the Advance Payment Model for qualifying Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs; the Comprehensive ESRD Care Initiative for beneficiaries receiving dialysis services; the Next Generation ACO Model for ACOs experienced in managing care for populations of patients; the Pioneer ACO Model (no longer active); and the Vermont All-Payer ACO Model.

contract, payments to clinicians typically continue on an FFS basis, and the ACO assumes the performance risk and associated incentives. Primary care is a central component of ACOs, and organizations differ in the extent to which they emphasize, incorporate, pay for, and support it.

In general, research on the impact of ACOs shows modest savings in total spending alongside quality and patient satisfaction improvements. Research has demonstrated that ACOs with a higher share of PCMH practices (Jabbarpour et al., 2018) and a greater proportion of PCPs perform better on cost and quality outcomes (Albright et al., 2016; Ouayogodé et al., 2017). Similarly, physician-led ACOs, compared to hospital-integrated ACOs, produce greater savings (Bleser et al., 2018; McWilliams et al., 2018). Medicaid ACO arrangements now exist in 14 states, showing mixed results (CHCS, 2017; McConnell et al., 2017; NAACOS, 2020). The Alternative Quality Contract, BlueCross BlueShield’s Medicaid ACO program in Massachusetts, has shown consistent improvement in quality and savings (Song et al., 2019), while the same commercial ACO program showed little effect in care quality or spending in children (Chien et al., 2014). However, Partners for Kids, a pediatric ACO in Ohio taking full risk for Medicaid enrollees, demonstrated a lower rate of cost growth without reduced quality measures or outcomes (Kelleher et al., 2015). Minnesota’s Medicaid ACO also showed promising results in the pediatric population (Christensen and Payne, 2016). ACO programs also show some evidence of reducing disparities (McConnell et al., 2018; Song et al., 2017).

ACOs have different structures for distributing performance-based payments across participants that can affect compensation of PCPs (Siddiqui and Berkowitz, 2014). ACO-affiliated practices are more likely than unaffiliated practices to use performance improvement strategies, such as feedback of quality data to clinicians, yet performance measures contribute little to physician compensation (Peiris et al., 2016; Rosenthal et al., 2019).

Primary Care Contracting

In response to the piecemeal efforts and heterogeneous results of hybrid payment models, recent Medicare payment reform efforts focus less on streamlining primary care transformation and more on total cost-of-care reductions. In 2019, CMMI announced several new risk-sharing models that will begin in 2021. Primary Care First combines capitated and reduced FFS payments, with greater potential for shared savings and expansion to a larger number of geographic regions (CMS, 2020f). The payments include performance-based incentives that use regional and historical benchmarks for spending, quality, and hospital use (CMS, 2020g). The capitated payment was calibrated to constitute about 60 percent of primary care payments.

CMMI also announced it would enable direct contracting models, which are capitated or partially capitated models that are broad in scope and touch on primary care in several ways (CMS, 2020c). The program has two voluntary risk-based payment arrangements. The professional option offers organizations capitated, risk-adjusted monthly payment for a defined set of enhanced primary care services. The global option provides the highest risk-sharing arrangements in exchange for capitated, risk-adjusted monthly payments for all services provided by a direct contracting entity and its preferred providers.

Direct primary care models typically work by charging patients a monthly, quarterly, or annual fee to cover all or most services, including preventive care, basic illness treatment for acute and chronic conditions, clinical and laboratory services, consultative services, care coordination, and comprehensive care management (AAFP, 2020; Doherty et al., 2015). Many direct primary care practices also arrange access to other discounted services, such as prescription drugs, laboratory tests, and imaging (Busch et al., 2020).

Patients from all segments of the health insurance market—commercially insured, uninsured, and beneficiaries of Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid—can be direct primary care members. Additionally, employers can offer a direct primary care option through their self-insured group health benefit plans, where they cover the fees. As a result of the relative newness of direct primary care, the literature assessing outcomes is small. In addition, studies are plagued by the difficulty of adjusting for the selection of healthy patients into these practices. One recent study found that after adjusting for differences in health status, a matched employer-based direct primary care cohort experienced a statistically significant reduction in total claim costs relative to the traditional cohort during the same period, meaning that enrollment in direct primary care was associated with reduced overall demand for health services. Direct primary care has similarities to concierge care, but key differentiators are direct primary care practices have lower membership fees and do not bill third parties on an FFS basis (Busch et al., 2020).

Finally, other primary care payment models have been proposed but not broadly tested, such as the Comprehensive Primary Care Payment Calculator (George et al., 2019), AAFP’s Advanced Primary Care Model (AAFP, 2017b), an Innovative Model for Primary Care Office Payment (Antonucci, 2018), and the Comprehensive Care Physician Payment Model (Meltzer, 2018; Tingley, 2018).

Findings for Option 3

- With almost half of primary care clinicians employed in health systems, attention should be paid to primary care payment methods in those settings. Many ACOs continue to pay primary care internally based on FFS, even though the larger organization may participate in risk-sharing models.

- ACOs have demonstrated modest savings in total spending alongside quality and patient satisfaction improvements. ACOs that are predominately primary care, PCMH based, or physician led achieve better performance than other ACOs. Some evidence indicates that pediatric-focused ACO models are effective for pediatric populations.

- Medicare is developing models to engage primary care practices more directly in managing the cost and quality of their care. These broad risk-sharing models have yet to be implemented.

Option 4: Increase the Allocation of Spending to Primary Care

The poor performance of the United States in many areas of population health has in part been attributed to a lack of “primary care orientation” of the country’s health system (Friedberg et al., 2010). Clear evidence suggests that systems oriented toward primary care in both policy and relative resource allocation show improved population outcomes and better efficiency over time (Bitton et al., 2017; Shi, 2012). One way to measure primary care orientation is simple: the portion of total health care expenses spent on primary care services. Although comparisons are difficult, it appears the United States spends a smaller (Koller and Khullar, 2017; PCC, 2018) to similar proportion (Berenson et al., 2020) of total expenses compared to other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, depending on the definition (OECD, 2018). In 2016, the year for which the most recent comparable data are available, the United States spent approximately 5.4 percent of total health expenditure on primary care, compared with an average among 22 OECD countries of 7.8 percent (OECD, 2019). Within the United States, higher state-level proportions of health care spending devoted to primary care are associated with fewer emergency department visits, total hospitalizations, and hospitalizations for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions (Jabbarpour et al., 2019). Given this, a fourth option for influencing the flow of funds to primary care teams focuses on a desired policy priority of increasing the share of health care spending devoted to primary care. To achieve this priority, policy makers would direct third-party payers to increase the proportion devoted to primary care and hold them accountable to achieving it.

This strategy was first developed in Rhode Island for commercial insurers as part of a set of Affordability Standards promulgated by the Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner (Koller et al., 2010). The original iteration of the Affordability Standards called on commercial insurers to raise their “primary care spend figure” by 1 percentage point per year for 5 consecutive years without adding to overall premiums. It also required the increased spending not be accomplished through FFS increases and authorized specific uses as qualifying, notably a statewide health information exchange. Oregon has now followed Rhode Island’s lead, and at least six other states have passed laws for public measurement and sometimes set targets for insurers (Jabbarpour et al., 2019). For example, Delaware, at the end of 2020, released a report through its Department of Insurance developing affordability standards for health insurance premiums and setting targets for insurance carrier investment (Delaware DOI, 2020).

Achieving the goal of implementing high-quality primary care through a strategy of regulating the proportion of spend devoted to primary care offers several advantages. It increases available funds, a key constraint to implementing high-quality primary care, and though the portion to be reallocated is a relatively small amount of total health care expenses, it would have large marginal effects in the primary care sector. It also addresses the failure of private health plan negotiations or Medicare to recognize the collective social value of primary care. In addition, this approach is relatively simple to understand and focuses public prioritization of primary care and the social benefits it delivers (Bolnick et al., 2020).

However, operational and policy challenges to such a strategy remain:

- Defining the policy goal: Target additional resources toward all primary care or specifically the desired elements of it? Are all means of distribution of equal merit? For example, Rhode Island specifically directed that the increase not be in FFS rates.

- What constitutes an acceptable rate of spend? Current spend differs by payer type because of population characteristics—an older and sicker population, such as with Medicare, consumes a greater share of health care resources on acute care, while a younger, healthier child population consumes considerably smaller levels of resources, with a resulting much greater share to primary care (AHRQ, 2020; Rui and Okeyode, 2016).

- Administering the measure requires a standard, administrable definition of primary care, and oversight and enforcement mechanisms.

- Is the state willing and able to coordinate its policy levers? Rhode Island’s work was for commercially insured populations only and did not extend to Medicaid or its public employees.

- The strategy is inherently redistributive, and while the amounts may be small, this strategy will generate public discussion and conflict over the relative value of different health care services.

- The multi-payer nature of U.S. health care financing dictates that any spending increase by one payer type will have only an incremental effect on overall spending on primary care services.

Since Rhode Island enacted its spending mandate, the share of commercial insurance spending going to primary care has risen from 5.7 percent in 2008 to 12.3 percent in 2018, with more than 55 percent of these payments now in non-FFS methods (OHIC, 2020). Unlike Rhode Island, Oregon’s statute extends to health insurers in Medicare and Medicaid and requires health insurance carriers and the risk-bearing provider organizations in Medicaid to allocate at least 12 percent of their health care expenditures to primary care by 2023. As of 2018, insurers had met these requirements (OHA, 2019).

Researchers investigating the effects of Rhode Island’s Affordability Standards have also found that since their implementation, commercial health insurance costs rose at a slower rate than in a matched comparison group (Baum et al., 2019). They attributed most of this effect to hospital price inflation caps rather than the primary care spend requirement but noted declines in outpatient use that are not statistically significant and could have resulted from more comprehensive primary care services. Oregon’s primary care spend requirement has been coupled with the creation of a primary care transformation office in state government that establishes and implements statewide standards for patient-centered primary care homes (PCPCHs) and a statutorily established oversight commission. Evaluations of the PCPCH program have shown positive results on cost and quality (OHA, 2015).

Rhode Island’s and Oregon’s efforts show that it is possible to use government action to increase the portion of health care expenses going to primary care. Both initiatives have attempted to influence how this additional money is spent, without being overly prescriptive, and both have been underpinned by state law or regulation and public support, oversight, and accountability. Public oversight has enabled both states to build political support to continue with these policies despite the lack of objective evidence conclusively identifying their positive effects on spending and quality. This support is based on public recognition of the value of primary care, a compelling argument that an insufficient share of resources is dedicated to it, an acceptance that this imbalance will not be corrected without public action, and directionally favorable evidence (Koller and Khullar, 2017).

Implementing a primary care spend requirement remains vexing, however, primarily because the local leadership required to build political

support and the overlapping state and federal authorities attenuate a requirement’s effects. While oversight of commercial health insurance and Medicaid are the province of state officials, Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and self-insured arrangements remain the responsibility of federal authorities. Because health plans often administer self-insured arrangements and tend to operate with a common provider contract for both commercial and self-insured populations, there may be spillover effects to self-insured populations. Furthermore, with the notable exception of Rhode Island, commercial statutory standards for health insurers do not include system-wide affordability efforts, circumscribing regulators’ authority to impose spending requirements without additional statute.

Although these remain fundamental barriers to any systemic approach to health care delivery system reform in the United States, existing state reforms have generated significant additional dollars flowing into primary care. To the extent that these are coordinated across multiple payment types, as is the case in Oregon, any resulting benefits in improved primary care capacity and performance are shared across all populations.

Findings for Option 4

- At a national level, primary care–oriented health care systems are associated with better population health and lower spending.

- The portion of total health care expenses going to primary care is a way to measure primary care orientation. By this measure, the United States is at or below the proportion in other developed countries.

- State-level policies to increase primary care spending rates have been politically sustainable, resulted in significant additional resources for primary care through non-FFS mechanisms, and supported statewide efforts to build primary care capacity. When coupled in Rhode Island with hospital price inflation caps to pay for increasing funds to primary care, there were attributable spending reductions.

PAYMENT AS A FACILITATOR OF HIGH-QUALITY PRIMARY CARE

In developing recommendations for payment policies to implement high-quality primary care—in addition to the evidence and experience on the effects of payment on cost, population health, and consumer experience—design considerations must be assessed, including the models’ effect on the development and deployment of interprofessional teams, the delivery of integrated care across settings, the patient’s relationship with the primary care team, and equity.

Primary Care Team–Patient Relationships

Throughout this report (most notably in Chapter 4), the committee has underscored the importance of the relationship between the primary care team and the patient. Ideally, this relationship is built on a foundation of trust and, relevant to payment specifically, a lack of conflict of interest (Emanuel and Dubler, 1995). The managed care era featured a concern over the erosion of clinician–patient relationships and patient trust (Gray, 1997; Mechanic, 1996; Mechanic and Schlesinger, 1996; Sulmasy, 1992), though few studies have measured the effect of payment models on clinician–patient relationships. One found that FFS patients had slightly higher levels of trust than those in salary, capitated, or managed care plans (Kao et al., 1998b). Most patients, however, did not know how their physician was paid, potentially indicating that payment model is not a salient issue for patients (Kao et al., 1998a). Patient trust and good interpersonal relationships with clinicians are major predictors of patient satisfaction and loyalty in primary care (Platonova et al., 2008), and many pay-for-performance programs include patient satisfaction measures. ACO and PCMH models have shown mixed effects on patient satisfaction, with some studies showing improvements (McWilliams et al., 2014b; Sarinopoulos et al., 2017) and others no association (Hong et al., 2018; Martsolf et al., 2012). Considering patient trust and satisfaction in any payment model design is of paramount importance, yet we have little evidence to guide payment based on research to date.

Finding

- Little consistent evidence suggests that payment models affect patient experience or clinician trust, but these considerations should be central to payment design.

Interprofessional Teams and Integrated Delivery of Care

Considerable evidence shows that high-quality primary care is best delivered by interprofessional teams in multiple settings (see Chapter 6). Chronic care, for example, requires routine telephonic or video access to nurse care managers, and the acutely ill need access to sophisticated diagnostic skills. Pregnant women often benefit from in-home education by community health workers, and children and families benefit from care within a medical home with team members focused on preventive care services and care coordination for children with medical and social complexity. FFS payment is not compatible with the committee’s definition of high-quality primary care, in that it discourages person-centered,

team-based care by requiring the identification of specific services delivered by contracted clinicians in permitted settings. Part of the appeal of capitated or bundled payment is the flexibility they offer for care in multiple settings from an integrated, interprofessional care team. This notion echoes that of the “New Primary Care Paradigm” (AAFP et al., 2020), a joint statement from seven PCP societies and boards that called for a shift from FFS payment to models that are compatible with care that is more person centered, team based, and integrated.

A specific example of this flexibility is the ability to integrate behavioral health care into primary care. Behavioral health care, when fully integrated, is effective in improving population health by addressing the underlying behavioral conditions that often manifest as somatic complaints (Basu et al., 2017; Reiss-Brennan et al., 2010, 2016). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of integrated primary care–behavioral health models for children and adolescents demonstrated better outcomes for the integrated care model compared with usual care, with the strongest effects for collaborative care models in which PCPs, care managers, and mental health specialists took a team-based approach (Asarnow et al., 2015). FFS payment models, particularly when paired with subcontracts by insurers for the management of behavioral health benefits, can discourage this integration by imposing licensing and billing restrictions. In addition, research has shown that current payment models cannot sustain integrated behavioral health care (Reiss-Brennan et al., 2016).

Primary care practices organized in response to FFS payment maximize revenue-producing in-person visits but are not configured to provide the integrated team-based care necessary to address the comprehensive preventive and chronic care needs of people and families, which must include behavioral, social, and oral health. Most attempts to develop these capacities in practices have recognized that it is insufficient to merely begin to pay practices differently; it is also necessary to invest in sustainable transformation resources, such as technical assistance and reimbursing practices for revenues forfeited as a result of staff development time. Medicare’s CPC+ payment model provides these additional resources through a combination of consultant payments and care management fees. Oregon has an office of primary care transformation funded through its Medicaid waiver. Some commercial insurance PCMH programs have provided similar transformation resources that are financed individually or jointly. Evidence has emerged that facilitating practice transformation improves and sustains the change process (Baskerville et al., 2012; Bitton, 2018; Harder et al., 2016). The ACA authorized a Primary Care Extension Program designed to support practice transformation facilitation. Though it was not funded, it became the basis for EvidenceNOW, a multi-state practice transformation trial funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Findings

- FFS payment methods can discourage the integration of services in primary care.

- Payment support for external, supporting services, such as practice facilitation, is important for helping practices evolve but difficult to support with traditional FFS payments.

Equity

Equity is a critical element of high-quality primary care and financial barriers, along with structural and procedural characteristics, can enhance or limit equitable access to health care. However, the precise effects of payment models on access to care are elusive. Each payment method presents risks to equitable access that must be managed by the payer, often through contract terms and oversight.

Addressing SDOH, including housing, nutrition, and education, has been an important piece of improving equity in recent years. A recent National Academies report set forth specific recommendations for how health care organizations can integrate care that addresses SDOH (NASEM, 2019a). These activities, such as assisting in referrals to social services and aligning services with them, do have a cost, and practices must fund them through their revenues. Primary care–based models that have undertaken these activities, such as Vermont’s Blueprint for Health, Rhode Island’s Community Health Teams, and various Oregon coordinated care organizations, have relied on flexible payment arrangements, including capitation, that encourage team-based care.

A systematic review found reimbursement models have limited effects on socioeconomic and racial inequity in access, use, and quality of primary care. The review found capitation has a small beneficial impact on inequity in access to primary care and number of ambulatory care–sensitive admissions compared to FFS but performed worse on patient satisfaction (Tao et al., 2016). Another survey found only 16 percent of physician practices (including primary care practices) screened for SDOH. Among practices, federally qualified health centers, bundled payment participants, participants in primary care improvement models, and Medicaid ACOs had higher rates of screening for all needs (Fraze et al., 2019). By targeting health disparities as measures of performance, enabling fair comparisons among interprofessional teams based on their patient populations, and incorporating community input in payment design, payment models can promote equity (Crumley and McGinnis, 2019). See Chapter 5 for more on integrating social needs into primary care delivery.

Finding