11

The Committee’s Approach to an Implementation Strategy

The committee focused its work explicitly on the implementation of high-quality primary care. This charge was a response to the lack of implementation of many of the recommendations from the report Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era (IOM, 1996). The committee interpreted its task of developing an implementation plan as one that requires its recommendations to be explicit—recommendations must not only have an actor and action but include specific guidance as to how the actors should carry out the actions to effect change (see Chapter 12 for the committee’s recommendations and implementation plan).

The specific actions the committee recommends to strengthen primary care are organized around a fundamental premise of high-quality care as a common good, an environmental assessment, a comprehensive analysis of the evidence for what constitutes high-quality primary care and its facilitators, lessons from implementation science and public policy studies, and a resulting three-part implementation strategy. As articulated in Chapter 2, the committee believes that high-quality primary care deserves status as a common good that merits public stewardship because of its unique capacity among health care services to improve population health and reduce health care inequities. Ongoing stressors in the U.S. health care system have continually weakened primary care and make attention to high-quality primary care delivery interventions a high public policy priority.

An implementation strategy must account for the environmental context in which it calls for implementing core objectives. The U.S. health care system is diverse and complex. Representing almost one-fifth of the U.S. economy (CMS, 2019), the health care system comprises multiple

sources of payments from public and private payers, numerous mechanisms and means for delivering health care, and often conflicting governmental oversight at the federal, state, and local levels (NASEM, 2019). The committee does not aspire to eliminate this complexity but rather to adopt a complexity-informed implementation strategy that considers the multiple influences and forces that must be factored into any primary care change process (Braithwaite et al., 2018). While universal health insurance or a single payer system would go a long way to reduce much of this complexity and give primary care the common good status the committee believes it deserves, the committee developed its implementation plan to work within the realities of the current U.S. insurance marketplace. Thus, rather than calling for radical transformations throughout the health care system, the committee’s implementation plan is made up of incremental changes that in combination would lead to a dramatic change to primary care in the United States.

In addition to defining high-quality primary care, the committee’s scope requires it to articulate the key proven facilitators necessary for implementing its plan. As first set forth in Chapter 2, the analysis of research and evidence regarding integrated care, digital health care, clinical accountability, payment models, interprofessional care teams, and research constitutes the heart of the committee’s report and resulting recommendations that target ways to effectively scale and implement successful innovations.

The committee’s implementation strategy informs its recommendations and must account for the work described above. The aim of implementation science is to accelerate the systematic uptake of evidence into real-world practice (Fisher et al., 2016). The committee drew three fundamental lessons from science and practice to inform its recommendations:

- The need for a conceptual understanding that recognizes the adaptive and dynamic developmental processes through which recommendations are translated and implementation occurs (Braithwaite et al., 2018; Nilsen, 2015).

- The need for a feedback structure for accountability for the use, alignment, and effectiveness of recommended actions (Greenhalgh and Papoutsi, 2019; Holtrop et al., 2018).

- The need for policies that reinforce and promote actions that support recommended actions and are congruent with system goals (Stetler et al., 2008).

Public policy analysis also makes it clear that strong, evidence-based policy recommendations are necessary but not sufficient for successful implementation. A strategy that accounts for public perceptions and political opportunities is necessary as well.

Based on these considerations, the committee’s implementation strategy includes three interrelated components: an implementation framework, an accountability framework, and a public policy–making framework.

AN IMPLEMENTATION FRAMEWORK

The committee draws from work by previous National Academies committees. In Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (IOM, 2001), the recommendations targeted four levels of change in the health care system (see Table 11-1): individual, group or team, organization, and larger system or environment (Ferlie and Shortell, 2001).

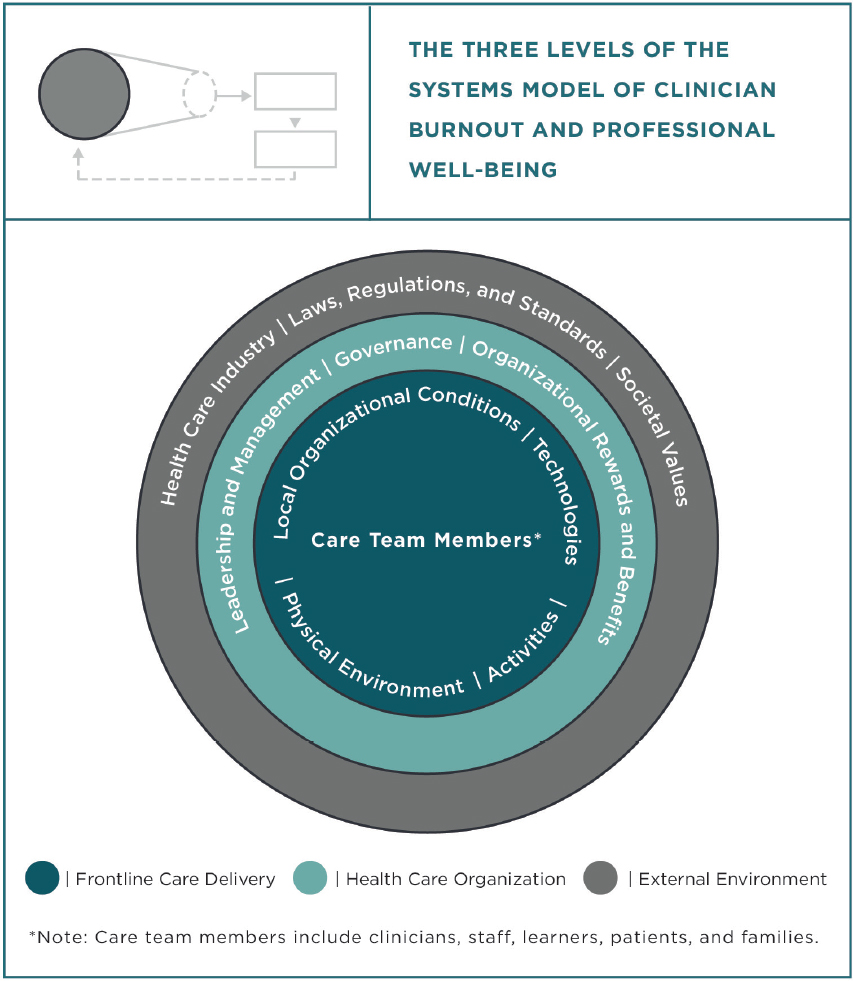

The 2019 National Academies report Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being combined the individual and team levels but maintained its emphasis on system levels that

TABLE 11-1 Four Levels of Change for Improving Quality

| Levels | Examples |

|---|---|

| Individual | Education |

| Academic detailing | |

| Data feedback | |

| Benchmarking | |

| Guideline, protocol, pathway implementation | |

| Leadership development | |

| Group/team | Team development |

| Task redesign | |

| Clinical audits | |

| Breakthrough collaboratives | |

| Guideline, protocol, pathway implementation | |

| Organization | Quality assurance |

| Continuous quality improvement/total quality management | |

| Organization development | |

| Organization culture | |

| Organization learning | |

| Knowledge management/transfer | |

| Larger system/environment | National bodies (NICE, CHI, AHRQ) |

| Evidence-based practice centers | |

| Accrediting/licensing agencies (NCQA, Joint Commission) | |

| Public disclosure (“report cards,” etc.) | |

| Payment policies | |

| Legal system |

NOTE: AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CHI = Commission for Health Improvement; NCQA = National Committee for Quality Assurance; NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

SOURCE: Ferlie and Shortell, 2001.

SOURCE: NASEM, 2019.

varied in their scope of focus (Ferlie and Shortell, 2001; NASEM, 2019) (see Figure 11-1). At the level of frontline care delivery, patients, families, and care teams interact at the point of care or virtually via technology. At the health care organization level, leadership and governance creates and maintains the processes and structures in which the frontline care delivery level operates. The external environment includes societal values, the greater health care industry, government, and the policies and standards that establish the parameters that the health care organizations and frontline care delivery levels must operate within.

This committee adopts a modified version of these three levels of an interrelated, complex system in which the committee distinguishes between

TABLE 11-2 The Committee’s Implementation Framework

| System Level | Public | Private | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example Actor | Example Actions | Example Actor | Example Actions | |

| Macro | Federal/state legislative branch | Policies; laws; funding | Coalitions; associations | Policy advocacy; public accountability; professional standards |

| Meso | Federal, state, local executive branch; federal payers; public delivery systems; educators | Regulations; contracting; payment; administrative practices; training | Private delivery organizations; private payers; corporations; institutions; educators | Management policies and practices; training |

| Micro | Individuals and interprofessional teams delivering care in public and government health systems; individuals and families seeking care | Self-education; quality assessment and improvement; behavior practice | Individuals and interprofessional teams delivering care; individuals and families seeking care | Self-education; quality assessment and improvement; behavior practice |

the public and private sectors within each of its three levels (see Table 11-2). Doing so accounts for the different actors and actions in the public and private sectors, each with different roles in the committee’s implementation plan. In the committee’s framework, the macro level includes federal and state governments and legislators, regulators, and coalitions and professional associations. The meso level includes the executive branches of federal, state, and local government; public and private payers; health care organizations; and community-based social services, health care corporations, and other health-affiliated institutions. The micro level includes interprofessional primary care teams that may operate in public- or private-sector organizations, patients, and their families. The implementation science lens focuses on the interconnections, interactions, and necessary bidirectional dialogue between and among actors at all three levels to effectively adopt core recommendations (Côté-Boileau et al., 2019; Fisher et al., 2016).

The implementation framework exists in the context of prevailing cultural and social values. With this context and framework in mind,

the task of the committee became reviewing the evidence for actions that promote scalable high-quality primary care—as presented in the bulk of the preceding chapters—and then proposing a portfolio of evidence-based recommendations for the public and private sectors at all three system levels. Implementation is a process that occurs dynamically over time, so the framework should include not just the need for recommendations to engage actors across different system levels in the public and private sectors but also consideration for how recommendations will be adopted, monitored, and improved over time.

The committee has identified three distinct but interrelated and continuous phases for the implementation of any recommendation:

- During a planning period, recommendations are formally considered and elaborated upon with purposeful design. Designated actors identify and develop the steps and resource capacity required to implement the recommendation, and leadership sets the vision, mission, and “social message” these recommendations explicitly propagate.

- During an adoption period, recommendations are implemented in a carefully managed and circumscribed accountable environment. Based on predicted and actual experience and evaluation, the steps are adjusted and resources identified in the planning period.

- During a scaling period, recommendations and key, effective, facilitating elements replicated during the adoption period are implemented in more and progressively broader settings to reach the population as a whole.

Detailing the specifics of each implementation phase for each recommendation is beyond the committee’s scope. However, implicit in each recommendation in Chapter 12 is the responsibility for the named actor to plan for building implementation capacity for all three phases.

AN ACCOUNTABILITY FRAMEWORK

For successful implementation, it is not enough have named actors and specific actions. A framework of accountability and feedback is required for those actors to communicate and cooperate (Berwick and Shine, 2020) regarding effective local adaption of recommended actions, assess implementation progress over time (Holtrop et al., 2018), and adapt practices as conditions change. Leaders are accountable for creating a learning, participatory culture that facilitates adoption through transparent evaluation methods. They promulgate open dialogue between delivery and policy through evaluating the intended impact and effectiveness of their

implementation plan by assembling objective measures of performance; a process for collecting, using, and accelerating timely learnings from those measures; and an enforcement and reward system based on performance and social impact. Scaling effective primary care innovations, such as those described in this report, beyond a local context to ensure a common good for the U.S. population depends on leaders building implementation capacity to support, sustain, and improve the core recommendations.

Within a single organization, such an accountability framework is relatively easy to develop: it is implemented through an organizational structure and using tools of change management accountability, such as measurement, communications, and performance reviews and incentives for quality. Outcomes are monitored constantly and fed back to frontline clinicians to promote continuous learning and improvement (Forrest et al., 2014; Greene et al., 2012). Across a health care system spanning almost one-fifth of the U.S. economy, an accountability framework is somewhat more difficult, requiring assessment and feedback at multiple system levels. While the 1996 report recommended establishing an accountability structure (in the form of a public–private consortium), the recommendation did not specify which entities should participate or lead the proposed endeavor, and it was never created. As discussed in Chapter 1, this lack of accountability structure was a critical reason many of that report’s recommendations went unimplemented.

However, systemic accountability can be facilitated by organizing constituents—those most affected by the success or failure of an implementation plan—for collective action related to implementation actions. Harnessing the local sensemaking capacities and actors’ voices at all three levels promotes the systematic spread and accountable scale of successful innovations. This is often most readily accomplished by joint private and public assessment of iterative progress on the impact of implementation actions and communication of findings. The committee’s implementation plan in Chapter 12 recommends ways to accomplish this.

A PUBLIC POLICY–MAKING FRAMEWORK

With primary care’s status as a common good, a significant portion of implementation actions will be the responsibility of the public sector. But primary care is not the only common good—there are many claims upon limited resources and conflicting notions of what constitutes the public welfare. Actors in the public sector act through the public policy–making process that adjudicates these competing values and priorities.

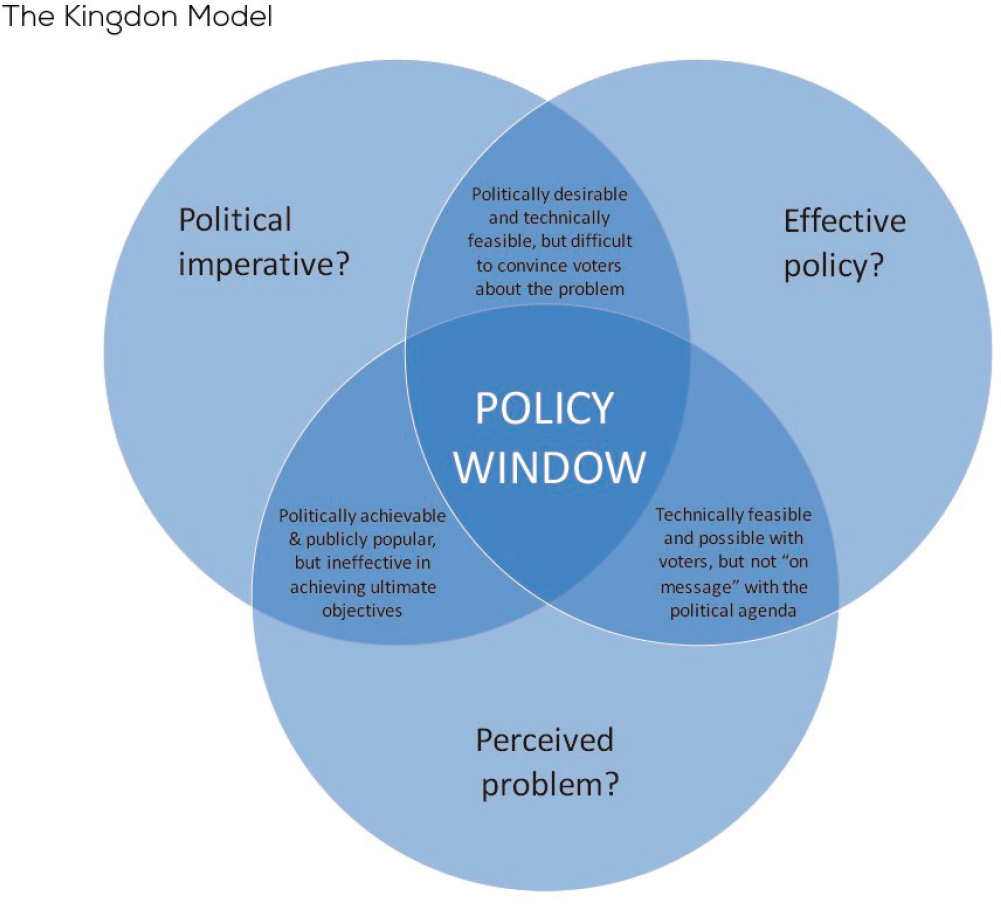

The committee’s implementation strategy draws from the frequently cited policy-making concept of the “policy window” (Kingdon, 1995), which proposes that regardless of the merits of a public policy proposal—in

this case, a series of actions that advance high-quality primary care—three separate public policy streams (political imperative, effective policy, and a perceived problem) must align to create a window of opportunity for implementation (see Figure 11-2). Achieving this to produce the window of opportunity is only partially serendipitous, for actors that promote policy actions, known as “policy entrepreneurs,” can create it (Guldbrandsson and Fossum, 2009; Kingdon, 1995). The committee’s implementation plan does indeed rest in part on the success of policy entrepreneurs committed to high-quality primary care, but it does recommend strategies for such actors.

Effective policy identification is typically the domain of reports from the National Academies, and the committee has endeavored to develop the basis for those regarding high-quality primary care in previous chapters. But the charge to the committee of “implementation” requires it to consider the domains of public perception and political imperative. These domains

SOURCES: NZIER, 2018, based on Kingdon, 1995.

are, by their nature, often specific to a moment in time. While research adds to policy evidence, commonly perceived problems and political opportunities at the time of this report may fundamentally change in the future.

Given the need to consider all aspects of the policy window, the committee considered the commonly perceived problems its recommendations could address. There are lessons to be drawn from states that have been leading on primary care policy, such as Vermont, with its Blueprint for Health (Bielaszka-DuVernay, 2011; Jones et al., 2016), Rhode Island (Koller et al., 2010), and Oregon (Howard et al., 2015; OHA, 2019), with their mandated primary care spend levels. In each case, policy leaders pointed to an unbalanced health care delivery system with a specialty and institutional orientation in comparison to the best-performing national and international systems, successfully making the case for public policy prioritization of primary care for long-term benefits in terms of lower health care costs and better population health, similar to what is seen in other countries.

These lessons may be applicable for federal policies. National polling shows that while Americans are generally satisfied with the quality of their personal care, a significant portion have concerns about affordability and access (Newport, 2019). Few believe the U.S. health care system to be in crisis, but a majority believes it has “major problems” and worries about the affordability and availability of health care in the future.

Implementing high-quality primary care can be a way to address public concerns about the ongoing stability of the U.S. health care system. It is an evidence-based investment in strengthening primary care now, for later benefit. It avoids protracted conflicts over comprehensive health reform and threats of perceived loss of access or choice. Leaders can point to declining U.S. life expectancy despite outsized health care expenditures to crystallize those concerns and the evidence regarding primary care’s significant positive benefits as a way to address them. For those policies that require expenditures, the relatively small proportion of health care expenses devoted to primary care then becomes an opportunity. A small absolute increase in primary care spending for the policies identified in this report, redistributed from the large expenses across the rest of the system, can have a high proportional effect on primary care. This redistribution argument will encounter resistance from the remainder of the system but is essential for leaders to address public concerns that health care is already too expensive.

The committee recognizes that the implementation of its plan may require new authorizations or changes to current federal or state law. While the committee’s plan addresses the policy changes it believes are needed to achieve its vision of high-quality primary care in the United States, it was beyond the scope of its task to identify the specific legal changes that may be required for implementation.

The COVID-19 Pandemic as a Catalyst for Change

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed much about what is broken in primary care and population health management. The imperative of addressing the lapses will be a useful and important mandate, in which private- and public-sector primary care champions could advance elements of the committee’s implementation plan. Leaders can use the collective experience of the pandemic to demonstrate how it weakened primary care in the United States at precisely the point when it was most needed: to partner with public health; decompress crowded emergency rooms; monitor populations most vulnerable to infection; conduct testing; treat less acute cases and contact trace; administer vaccines; treat long-term sequelae; and prepare for the social and emotional fallout of a distressed and isolated population.

Instead, according to a weekly national survey, within 3 weeks of the March 13, 2020, declaration of a national emergency, half of primary care practices reported a severe effect. Some 90 percent were limiting chronic and acute care visits, and the large majority were switching to predominantly telehealth visits, despite a mostly deficient technology infrastructure beyond basic telephone services (The Larry A. Green Center and PCC, 2020a). Saddled with a fee-for-service reimbursement system at a time when in-person visits were actively discouraged, just 1 month into the pandemic, nearly half of primary care practices were unsure if they had enough cash to remain open, 47 percent had laid off or furloughed staff, and 85 percent reported dramatic decreases in visit volume and corresponding income. Three-fifths of practices noted that the majority of their work was not reimbursable, even as they responded to COVID-19’s effects on patients’ physical, psychological, and financial well-being (The Larry A. Green Center and PCC, 2020b).

Soon, one can anticipate sweeping federal policies in the aftermath of the pandemic, much as Congress acted in the wake of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the flooding of New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina, and the economic collapse of 2008. The realms of action might include public health investments and pandemic preparation, health care system strengthening and pandemic resiliency, and economic recovery. This recovery and rebuilding effort can constitute the political imperative required to advance the committee’s policy recommendations, given skillful and committed champions in positions of influence who can communicate the missed potential of primary care to assist in the pandemic and capitalize on public concerns about the future sustainability of our health care system.

A strategy is a well-considered plan, not an assurance of results. While the evidence of the value of primary care for population health and its weakened state in the United States is incontrovertible, evidence-based recommendations alone are insufficient to effect change and promote

high-quality primary care. An implementation framework, a model for accountability, and a public policy–making framework provide a guide to select recommendations and increase the likelihood of their adoption, the rate of their implementation, and the speed with which the resulting benefits will accrue to the nation over time.

REFERENCES

Berwick, D. M., and K. Shine. 2020. Enhancing private sector health system preparedness for 21st-century health threats: Foundational principles from a National Academies initiative. JAMA 323(12):1133–1134.

Bielaszka-DuVernay, C. 2011. Vermont’s blueprint for medical homes, community health teams, and better health at lower cost. Health Affairs 30(3):383–386.

Braithwaite, J., K. Churruca, J. C. Long, L. A. Ellis, and J. Herkes. 2018. When complexity science meets implementation science: A theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Medicine 16(1):63.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2019. National health expenditure data. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-andReports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical (accessed July 22, 2020).

Côté-Boileau, E., J.-L. Denis, B. Callery, and M. Sabean. 2019. The unpredictable journeys of spreading, sustaining and scaling healthcare innovations: A scoping review. Health Research Policy and Systems 17(1):84.

Ferlie, E. B., and S. M. Shortell. 2001. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: A framework for change. Milbank Quarterly 79(2):281–315.

Fisher, E. S., S. M. Shortell, and L. A. Savitz. 2016. Implementation science: A potential catalyst for delivery system reform. JAMA 315(4):339–340.

Forrest, C. B., P. Margolis, M. Seid, and R. B. Colletti. 2014. PEDSnet: How a prototype pediatric learning health system is being expanded into a national network. Health Affairs 33(7):1171–1177.

Greene, S. M., R. J. Reid, and E. B. Larson. 2012. Implementing the learning health system: From concept to action. Annals of Internal Medicine 157(3):207–210.

Greenhalgh, T., and C. Papoutsi. 2019. Spreading and scaling up innovation and improvement. BMJ 365:l2068.

Guldbrandsson, K., and B. Fossum. 2009. An exploration of the theoretical concepts policy windows and policy entrepreneurs at the Swedish public health arena. Health Promotion International 24(4):434–444.

Holtrop, J. S., B. A. Rabin, and R. E. Glasgow. 2018. Dissemination and implementation science in primary care research and practice: Contributions and opportunities. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice 31(3):466–478.

Howard, S. W., S. L. Bernell, J. Yoon, J. Luck, and C. M. Ranit. 2015. Oregon’s experiment in health care delivery and payment reform: Coordinated care organizations replacing managed care. Journal of Health Politics, Policy & Law 40(1):245–255.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1996. Primary care: America’s health in a new era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Jones, C., K. Finison, K. McGraves-Lloyd, T. Tremblay, M. K. Mohlman, B. Tanzman, M. Hazard, S. Maier, and J. Samuelson. 2016. Vermont’s community-oriented all-payer medical home model reduces expenditures and utilization while delivering high-quality care. Population Health Management 19(3):196–205.

Kingdon, J. 1995. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. New York: Longman.

Koller, C. F., T. A. Brennan, and M. H. Bailit. 2010. Rhode Island’s novel experiment to rebuild primary care from the insurance side. Health Affairs 29(5):941–947.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2019. Taking action against clinician burnout: A systems approach to professional well-being. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Newport, F. 2019. Americans’ mixed views of healthcare and healthcare reform. https://news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/257711/americans-mixed-views-healthcare-healthcare-reform.aspx (accessed November 20, 2020).

Nilsen, P. 2015. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science 10(1):53.

NZIER (New Zealant Institute of Economic Research). 2018. Population ageing: Do we understand and accept the challenge? Wellington, NZ: Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand.

OHA (Oregon Health Authority). 2019. Primary care spending in Oregon: A report to the Oregon legislature. Salem, OR: Oregon Health Authority.

Stetler, C. B., L. McQueen, J. Demakis, and B. S. Mittman. 2008. An organizational framework and strategic implementation for system-level change to enhance research-based practice: QUERI series. Implementation Science 3(1):30.

The Larry A. Green Center and PCC (Primary Care Collaborative). 2020a. Quick COVID-19 primary care survey: Clinician series 3 fielded March 27–30, 2020. https://www.greencenter.org/covid-survey (accessed September 15, 2020).

The Larry A. Green Center and PCC. 2020b. Quick COVID-19 primary care survey: Clinician series 7 fielded April 24–27, 2020. https://www.green-center.org/covid-survey (accessed September 15, 2020).