3

Primary Care in the United States: A Brief History and Current Trends

For the first two-thirds of the 20th century, the lone general practitioner served as the face of primary care in the United States. However, primary care was a shrinking presence with the rise of subspecialty care and urbanization following World War II (Stevens, 2001). Three commissioned reports on the challenges facing primary care—Millis (Citizens Commission on Graduate Medical Education, 1966), Folsom (National Commission on Community Health Services, 1967), and Willard (AMA et al., 1966)—were soon followed in 1969 by establishing family practice, the 20th medical specialty, as part of an effort to reverse the decline in primary care. General internal medicine, geriatric medicine, and general pediatrics also found their ways into academic medical centers in response to the needs of their patients and communities. The first neighborhood health centers focused on primary care, which became today’s health centers,1 were also established in the mid-1960s as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty (CHroniCles, 2020), and the nurse practitioner (NP) certification project was started at the University of Colorado Medical School to “bridge the gap between health care needs of children and families’ ability to access and afford primary health care” (Ford, 1979, p. 517). In the 1970s, the recognition of the number of aging veterans (and their impact on the

___________________

1 Health centers, as defined by section 330 of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. § 254b), include outpatient clinics in federally designated underserved areas that qualify for specific reimbursement systems under Medicare and Medicaid. They include (but are not limited to) federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), FQHC look-alikes, rural health clinics, school-based health centers, and tribal and urban Indian health centers.

veteran’s health care system) led the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to establish the first Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) (Morley, 2004). The GRECCs supported education and training in geriatrics, and developed interdisciplinary team training programs to provide care for the aging population.

In the early 1980s, most primary care practices were independent, small, and organized around relationships, patient loyalty, reputation, place, a “pay what you can” fee-for-service (FFS) model, professional duty, and personal and family care, with an emphasis on comprehensiveness, continuity, and access. Often, this period is seen through the lens of fond nostalgia, but general practice in those days was paternalistic, driven almost exclusively by physicians (who were nearly all male and white), and lacked transparency about the quality of care. These practices were also disconnected from each other and only connected to the larger health care system and local community through personal relationships and the more close-knit neighborhoods of the time. Information sharing with other parts of the larger health care system, such as specialty care, was limited or even nonexistent (Kim et al., 2015).

By the start of the 21st century, most primary care practices would be almost unrecognizable to past generations of primary care clinicians. Relative to decades ago, practices today are larger (Liebhaber and Grossman, 2007), often part of health care systems (Kane, 2019), and generally not organized around values, professionalism, and relationships. Instead, they exist within a new administrative and technological context, including National Committee for Quality Assurance recognition, accountable care organization requirements, the ubiquitous use of electronic health records, compensation based on relative value unit productivity, and pay-for-performance metrics. New models of care, such as patient-centered medical homes, developed originally as a pediatric care model, and Advanced Primary Care, addressed many of the concerns of the traditional care model because they aimed to be more collaborative and transparent, associated with various measures of quality, and more formally connected with each other and the health system. However, this new organization of primary care has come with rising moral distress and disturbingly high levels of burnout in clinicians, community and personal disconnections, and inordinate and surprising dissatisfaction all around (Kim et al., 2018; Shanafelt et al., 2012; Sinaiko et al., 2017).

Today, NPs, physicians, and physician assistants (PAs) provide most of the in-office, primary care services in the United States (IOM, 2011). Increasingly, though, they also work with an interprofessional team that may include community health workers (CHWs) or aides, promotores de salud,

health coaches, informal caregivers, certified nurse-midwives (CNMs),2 and behavioral health specialists, who can help primary care practices address the socioeconomic conditions and behaviors that research has shown are major determinants of health (Kangovi et al., 2020). Also, because informal caregivers, CHWs, and promotores de salud reflect the communities they serve, these team members can help shift the primary care workforce from its clinician-centric traditions to an approach that includes the people, families, and communities that it addresses (Chernoff and Cueva, 2017; Manchanda, 2015). In 2017, approximately 223,125 (31.9 percent) of all office-based, direct patient care physicians were primary care physicians (Petterson et al., 2018). Data from 2019 show that 25 percent of PAs work in primary care settings (NCCPA, 2020). The National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses estimates that 15 percent of registered nurses and 29 percent of advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs)3 reported that they spend most of their patient-care time in primary care settings (HHS et al., 2020). While it is unclear precisely how many work in primary care settings (Sabo et al., 2017), the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated nearly 59,000 CHWs in the United States, with approximately 5,100 in outpatient care centers, 4,720 in general medical and surgical hospitals, and 3,700 in physician offices (BLS, 2019).

It is surprisingly difficult, however, to describe the broader primary care workforce in detail, because national data neglect many professions, such as behavioral health specialists, pharmacists, health coaches, and others who make up interprofessional primary care teams (see Chapter 6 for more on the workforce). Better data on the professionals in such teams will be useful as primary care practice continues to become more team based and inclusive of non-clinician care team members.

While oral health is an essential component of the health of the whole person, dental care remains largely siloed in both payment and delivery from the rest of health care, including from primary care. While there are examples of oral health integration into models of primary care delivery (notably in health centers), oral health professionals are generally not included in most interprofessional primary care teams today and it is unclear how many are working in integrated settings.

While the numbers of NPs and PAs are steadily increasing, the proportion working in primary care settings has decreased (AANP, 2020; NASEM, 2016; NCCPA, 2020), as has the proportion of medical students and residents entering primary care in recent years (Naylor and Kurtzman, 2010;

___________________

2 CNMs are licensed, independent health care clinicians with prescriptive authority in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. CNMs are defined as primary care clinicians under federal law (ACNM, 2019).

3 APRNs include NPs, CNMs, nurse anesthetists, and clinical nurse specialists. This report focuses on NPs, who work most consistently in primary care, except where data reports at the APRN level only.

NRMP, 2020). The number of CHWs is increasing, though it is difficult to quantify exactly how many are working in primary care because they have more than 100 different job titles (Sabo et al., 2017).

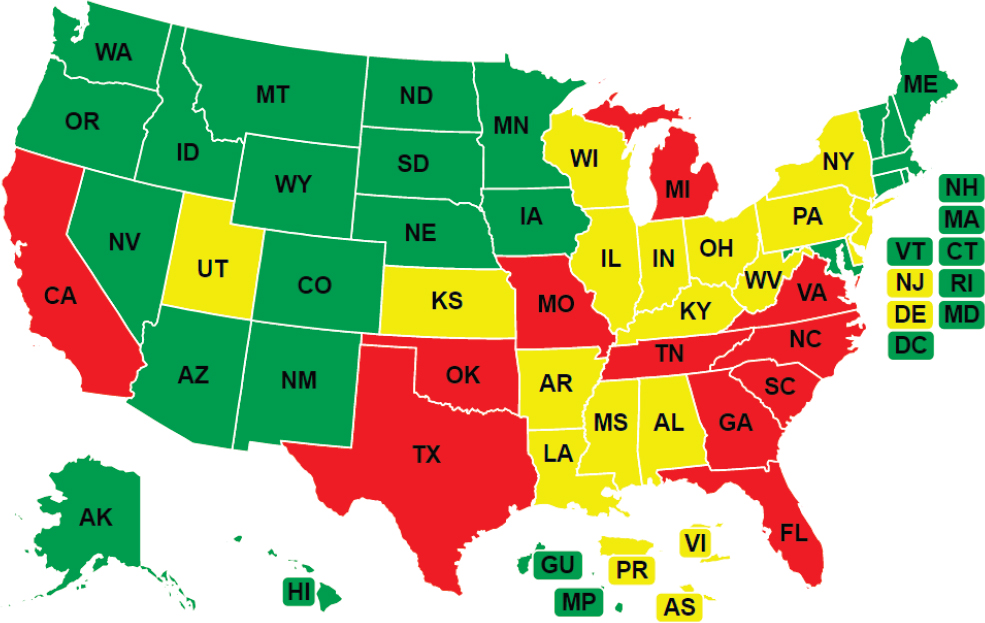

The rapid growth of health care professionals other than physicians has increased their contributions to the primary care workforce, particularly in rural areas, but the nationwide distribution of all health care workers is uneven (AHRQ, 2012). One contributor to this result for NPs, PAs, and CHWs, for example, is variation in state scope of practice regulations, some of which still prohibit them from working independently from a supervising physician. As of 2021, only 23 states and the District of Columbia allow NPs to independently evaluate patients; diagnose, order, and interpret diagnostic tests; and initiate and manage treatments, including prescribing medications and controlled substances. Laws in another 16 states restrict at least one element of practice and require a career-long, regulated collaborative agreement with another health provider in order for the NP to provide patient care (AANP, 2021) (see Figure 3-1). For PAs, 37 states allow for the determination of scope of practice to be jointly established through a written agreement between the supervising physician and PA at the practice level (AAFP, 2019). As of 2016, 16 states had laws addressing scope of practice for CHWs (CDC, 2017), and each state had its own particular take on what it should be.

This regulatory variation can make it difficult to organize primary care teams effectively. Nearly a decade ago, more than 50 percent of family physicians worked with NPs, PAs, and CNMs, and the percentage was even higher in rural areas (Peterson et al., 2013). Responding to this finding, Jean Johnson, former dean of the School of Nursing at The George Washington University, said,

Rather than NPs and FPs [family physicians] continuing to focus on issues of who is the captain of the team or who can have an independent practice, the overriding principle for continued dialogue should keep the patient at the center of our efforts. There is too much work to be done to meet the health care needs of the United States for nursing and medicine to be at odds. (Johnson, 2013, p. 242)

Relatedly, NPs and PAs do not have dedicated, public databases about the two workforces, making it difficult to discern how many from each profession are working in primary care settings versus those who were trained in that setting. As cited earlier in this chapter, the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses offers estimates of those practicing in primary care (HHS et al., 2020) but does not provide a broader workforce enumeration and monitoring function the way that the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile4 or the Health Resources and Services Administration

___________________

4 See https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/masterfile/ama-physician-masterfile (accessed February 14, 2021).

NOTE: States in green allow full practice, states in yellow reduced practice, and states in red restricted practice.

SOURCE: AANP, 2021.

(HRSA) Area Health Resources File5 does for physicians. Membership files for several PA organizations offer better insights and monitoring capacity (Orcutt, 2015), but a combined, cleaned file would give a clearer picture.

Primary Care Specialties

Another notable change from earlier generations of primary care is the growth of primary care specialties, including family medicine, general internal medicine, general pediatrics, adolescent medicine, and geriatric medicine, each with its own professional organizations and advocacy groups (Dalen et al., 2017). A growing number of primary care physicians are also moving into niche areas, such as sleep medicine, hospital-based care, and sports medicine, often seeking greater income and improved lifestyle (Cassel and Reuben, 2011). The primary care advanced practice professions also have their own professional organizations and accreditation bodies, adding to the complexity of the field. This continued fragmentation of practice has diminished the generalist role of primary care and the ability to focus on

___________________

5 See https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf (accessed February 14, 2021).

the health of a community or population (see Box 3-1 for more information on the value of the generalist). Other care disciplines that contribute to primary care in some models include dental health, physical therapy, social work, occupational therapy, pharmacy, and behavioral health, each with its own professional organizations and description of the roles it plays in primary care.

CURRENT PRIMARY CARE PRACTICE TYPES

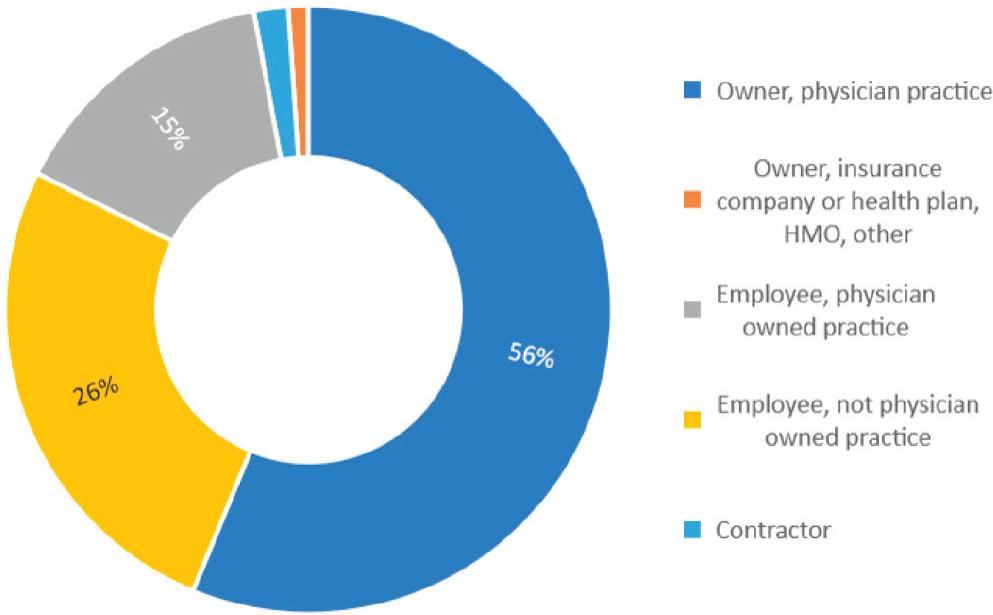

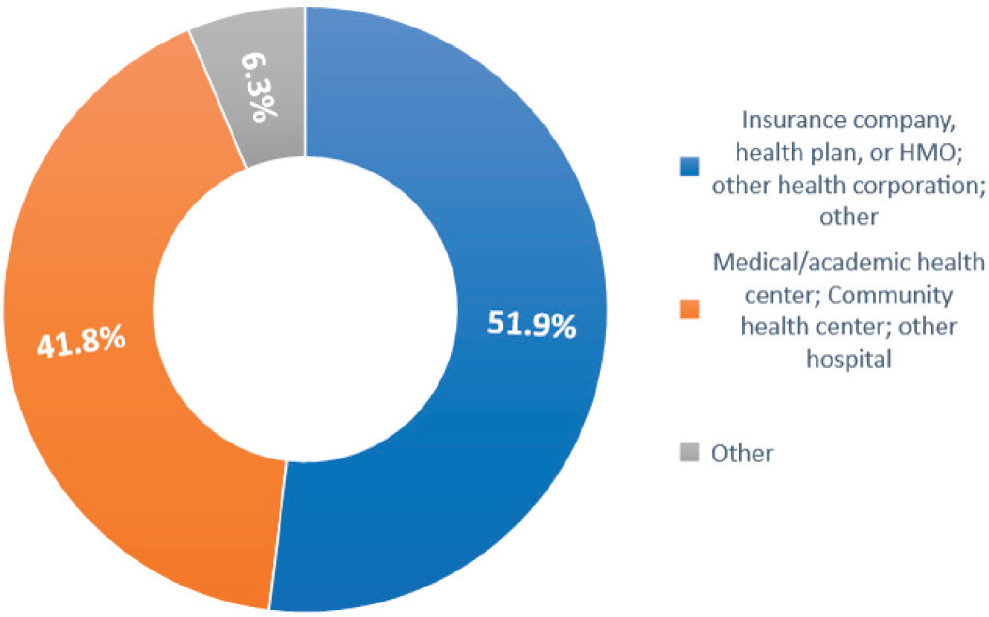

As of 2014, some 56 percent of primary care physicians worked in practices in which they were full or partial owners, while 41 percent were employees, of either a physician-owned or non-physician-owned practice (see Figure 3-2). Of the 26 percent in non-physician-owned practices, 51.9 percent were in practices owned by insurers, health plans, health maintenance organizations, or other corporate entities, while 41.8 percent were

NOTES: HMO = health maintenance organization. Contractor = 2%; Owner, insurance company or health plan, HMO, other = 1%.

SOURCE: Petterson et al., 2018.

NOTE: HMO = health maintenance organization.

SOURCE: Petterson et al., 2018.

in a medical or academic health center, community health center, or other hospital (Petterson et al., 2018) (see Figure 3-3).

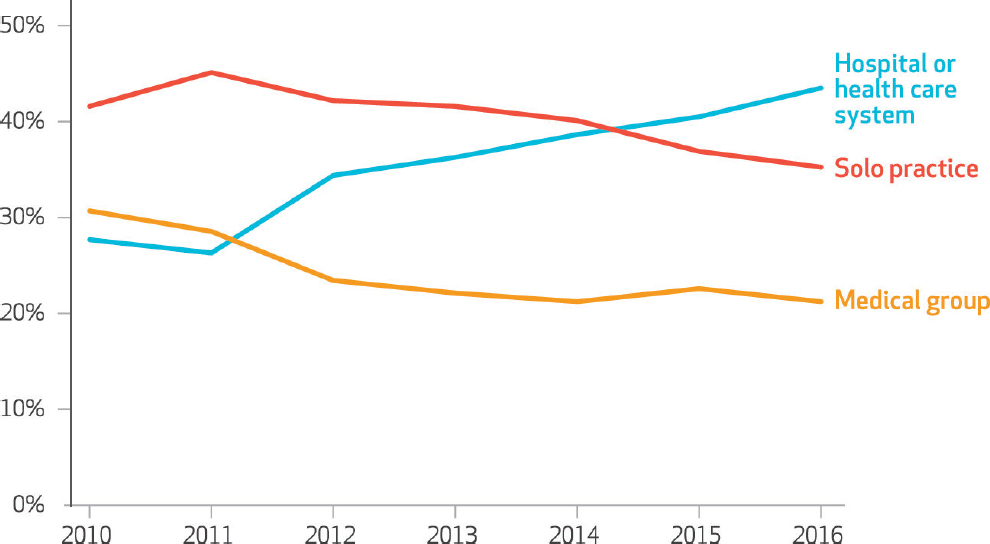

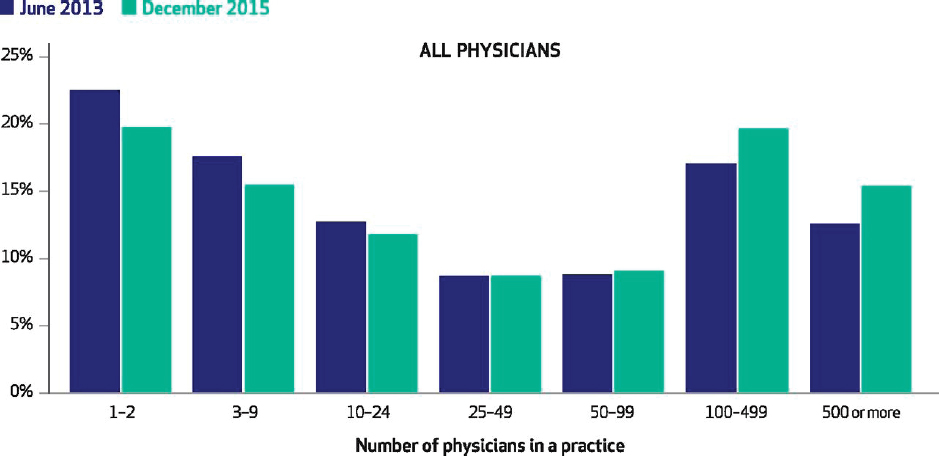

Solo and small practices of fewer than five physicians have long been an important component of the U.S. primary care system. However, a combination of factors are changing the landscape of primary care practices and leading to consolidation and loss of independent practices. A 2017 study found that between 2010 and 2016, the percentage of primary care physicians working in a practice owned by a hospital or health system increased from 28 to 44, and the percentage of those working in an independently owned practice decreased by a similar amount (Fulton, 2017) (see Figure 3-4). More recently, a study by the Physicians Advocacy Institute and Avalere Health found that between 2016 and 2018, hospitals acquired some 8,000 medical practices and approximately 14,000 physicians left private practice to work in hospitals (PAI and Avalere Health, 2019). Another study found that while physicians of all specialties are moving from smaller to larger group practices, primary care practices are consolidating much faster than specialty practices (Muhlestein and Smith, 2016) (see Figure 3-5). The financial pressures that the COVID-19 pandemic wrought on independent primary care practices that rely largely on FFS payments (Basu et al., 2020) may accelerate this shift.

Research on the effects of consolidation on access to care and quality of care is scant, with most focusing on how it has contributed to the rising cost of care (Baker et al., 2014; Dunn and Shapiro, 2014). One study did

SOURCE: Fulton, 2017.

SOURCE: Muhlestein and Smith, 2016.

find that clinician concentration was associated with relative improvements in Medicaid beneficiaries’ access to care (Bond et al., 2017). Another study found that Medicare patients had worse health outcomes and higher health care expenditures when receiving treatment in areas where clinician concentration was highest (Koch et al., 2018).

Retail and Direct-to-Consumer Urgent Care Clinics

A relatively recent trend is the growth of retail or direct-to-consumer clinics, typically staffed by NPs and PAs. A 2014 market assessment estimated the size of the U.S. retail clinic market at $1.4 billion and projected an annual growth rate of 20 percent through 2025 (Grand View Research, 2017). While retail clinics have been promoted as a means of reducing emergency department visits and decreasing health care spending, research findings have been mixed as to whether those two claims are correct (Alexander et al., 2019a,b; RAND, 2016). In addition, policy makers are concerned that increased use of retail clinics will create missed opportunities for preventive care, make coordination and continuity of care more challenging, and pose a threat to the financial viability of primary care practices by treating the latter’s most profitable cases (Weinick et al., 2011). Nevertheless, the number of retail clinics is expected to reach 3,000 in 2020 (up from close to 1,200 in 2000) (CCA, 2017). At the same time, health

systems are opening a growing number of urgent care clinics that can compete with retail clinics. The Urgent Care Association notes that there were 9,279 urgent care centers as of June 2019 and that their number has been growing by 400 to 500 centers annually since 2014 (UCA, 2019).

Both retail and urgent care clinics typically serve younger adults who otherwise do not have a primary care clinician (RAND, 2016). Still, a 2015 survey asking individuals where they would go for treatment of a non-emergency or non-life-threatening situation found that a plurality of those in the 18–34 age group still preferred traditional primary care, delivered in an office setting, over all other options, and that a majority of consumers age 35 years and older preferred traditional primary care over other options (FAIR Health, 2015) (see Table 3-1).

While the growth of both retail and urgent care clinics are evidence that both settings will continue to deliver a substantial amount of problem-based care, it is important to note that the committee’s definition of high-quality primary care (see Chapter 2) is largely incompatible with the retail clinic and urgent care delivery models. Of particular note, the episodic nature of the care delivered in these settings is not conducive to either whole-person health or individuals and their families building and maintaining relationships with their primary care team (it may instead be a PA or an NP who is different at every visit) (Reid et al., 2012). The increase in health systems starting urgent care clinics is a mechanism to link the person who visits an urgent care clinic when their primary care service is closed back to the larger primary care network.

TABLE 3-1 Settings Where Consumers Would Most Likely Go for Treatment for a Non-Emergency or Non-Life-Threatening Situation

| Age | Primary Care in a Traditional Office Setting | Emergency Room | Urgent Care | Walk-in Clinic at a Pharmacy or Retail Center |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–34 | 43% | 25% | 21% | 7% |

| 35–44 | 54% | 21% | 19% | 3% |

| 45–54 | 64% | 19% | 8% | 5% |

| 55–64 | 62% | 16% | 13% | 7% |

| 65+ | 59% | 22% | 9% | 4% |

| Total Population | 55% | 21% | 15% | 5% |

SOURCE: FAIR Health, 2015.

ACCESS TO PRIMARY CARE

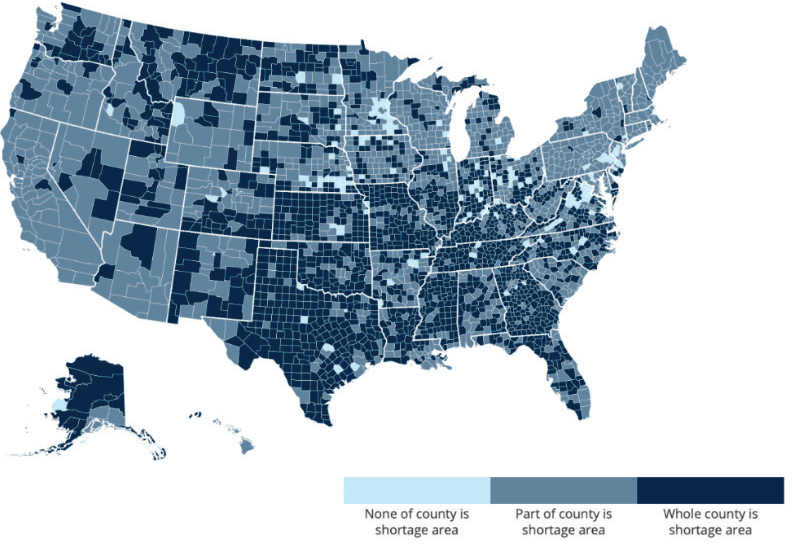

More than 80 million individuals live in a primary care Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) (HRSA, 2020) (see Figure 3-6).6 These designations are often used by the HRSA to prioritize funding for health centers and by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for reimbursement and payment incentives for primary care clinicians (CMS, 2019).

Since 2000, health centers’ capacity to provide primary care has nearly tripled, and they now provide care to nearly 30 million people in the United States (Sharac et al., 2018). Despite this considerable investment in health centers and the National Health Service Corps,7 rural and underserved areas continue to experience an inadequate primary care workforce, which is generally a source of health inequity (Basu et al., 2019; Gong et al., 2019). Nearly 20 percent of the U.S. population resides in a primary care HPSA, with HRSA designating nearly 40 percent of rural areas (counties) as such (HRSA, 2020). Although the supply of primary care clinicians is greater in urban than rural areas (Xue et al., 2019), predominantly Black, brown, and

SOURCE: HRSA, 2020.

___________________

6 A HPSA is an area HRSA designates if the supply of primary care physicians does not meet the needs of the local population based on the population-to-clinician threshold of 3,500:1.

7 The National Health Service Corps is an HRSA scholarship and loan repayment program designed to incentivize primary care medical, dental, and mental and behavioral health professionals to work in HPSAs. See https://nhsc.hrsa.gov (accessed February 14, 2021) for more information.

Indigenous neighborhoods in urban areas are significantly more likely to have a shortage of primary care clinicians when compared to other neighborhoods (Brown et al., 2016; Huang and Finegold, 2013). Given the large population of urban counties, differences in the availability of primary care clinicians are only observed at the neighborhood level.

The number of U.S. primary care physicians per capita has declined in recent years (Basu et al., 2019). In 2016, HRSA estimated that by 2025, an additional 23,640 will be needed to meet the projected demand, with the southern region being hardest hit (HRSA and NCHWA, 2016). HRSA also estimated that the supply of primary care NPs and PAs will exceed demand by 2025 and that “with delivery system changes and full utilization of NP and PA services, the projected shortage of [primary care physicians] can be effectively mitigated” (HRSA and NCHWA, 2016, p. 4). (See Chapter 6 for a more detailed discussion of primary care workforce issues.) This assessment demonstrates a general lack of understanding regarding complementary or team-based care. The problem of scope convergence is not just an expansion for NPs and PAs but also a narrowing for physicians. Advanced, interprofessional primary care models do not presume that these clinicians have identical roles but rather that they offer a combined, broader scope of services that their unique training and experience support.

Factors other than clinician supply limit access to primary care, including lack of health insurance (Ayanian et al., 2000; Freeman et al., 2008; Hadley, 2003; Tolbert and Oregera, 2020), type of insurance (Alcalá et al., 2018; Hsiang et al., 2019), language-related barriers (Cheng et al., 2007; Ponce et al., 2006), disabilities (Krahn et al., 2006), inability to take time off work to attend appointments (Gleason and Kneipp, 2004; O’Malley et al., 2012), and geographic and transportation-related barriers (Douthit et al., 2015). Lack of insurance decreases the use of preventive and primary care services, which translates into poor health outcomes (Ayanian et al., 2000), an issue that is particularly acute for racial and ethnic minority populations (Brown et al., 2000). While the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)8 led to historic gains in health insurance coverage—fewer than 26.7 million non-elderly Americans were uninsured in 2016, down from 46.5 million in 2010, before the ACA went into effect—the number of uninsured increased to 28.9 million in 2019 and the uninsured rate has increased steadily since 2017 as a result of changes made to the ACA (Tolbert and Orgera, 2020). Most of those without insurance are in low-income families with at least one worker in the family, with adults and people of color more likely to be uninsured than children or non-Hispanic white people.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also had notable implications for access

___________________

8 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 111-148 (March 23, 2010).

to primary care. In response, many practices eliminated nonessential in-person visits. In some cases, practices were able to provide access to care via telehealth. However, while the change in CMS and many private insurers’ rules ensured that more types of visits could be delivered virtually, many practices did not have the infrastructure in place to make the shift quickly or at all. Furthermore, many people did not have access to the technology required (Nouri et al., 2020; Velasquez and Mehrotra, 2020). Many services that require in-person appointments, such as immunizations and other types of preventive care most commonly delivered in primary care settings, have been delayed during the pandemic (Czeisler et al., 2020).

PRIMARY CARE USAGE TRENDS

Despite the new research, reforms, and policy changes of the last two decades emphasizing the importance of primary care, the rate of in-office primary care visits has decreased (Chou et al., 2019; Ganguli et al., 2020). Total visits by commercially insured adults to primary care offices decreased by 24.2 percent between 2008 and 2016 (Ganguli et al., 2020). This reduction is driven by a decline in problem-based visits, down by 30.5 percent, whereas preventive care visits actually increased by 40.6 percent during this time (Ganguli et al., 2020). These changes in visit type and the avoidance of care may be related to rapid adoption of high deductible health insurance; it demonstrably reduces problem-based primary care services, which often require copays (wellness or preventive care visits often do not) (Rabin et al., 2017; Reddy et al., 2014). The changes in visit type may also be a reflection of people choosing convenient visits to urgent care and retail clinics for problem-based care, while maintaining yearly scheduled wellness or preventive care with primary care clinicians. A study of commercially insured children found similar patterns during this same period, although the overall decline in office visits was not as great (14.4 percent) (Ray et al., 2020). Despite this overall decline, primary care services from NPs and PAs continues to grow (Frost and Hargraves, 2018; Ganguli et al., 2020). Reflecting these trends, a 6 percent decline in spending on primary care office visits also occurred between 2012 and 2016, but spending on specialist visits increased by 31 percent (Frost et al., 2018).

Several possible explanations exist for the decrease in primary care visits. One theory is that primary care’s efforts to emphasize the clinician–patient relationship, incorporate technology, and provide comprehensive care are working. While the number of visits overall is in decline, the appointments that do take place are typically longer, are more likely to be via Internet or telephone, and result in fewer follow-up appointments and fewer unneeded appointments (Ganguli et al., 2020; Rao et al., 2019). With greater attention to continuity and coordination of care, visits that

do occur may be more efficient and productive and result in fewer face-to-face follow-up appointments (Ganguli et al., 2019). Lack of insurance or insurance with high deductibles may also explain the decline. Average out-of-pocket cost per problem-based primary care visits has increased steadily as well, rising more than $10 (from $29.7 to $39.1) between 2008 and 2016 (Ganguli et al., 2020).

Despite these potential explanations, systemic access problems persist and are a contributing factor to declining office visits. The insufficient supply of primary care clinicians and their uneven geographic dispersal leads to an inadequate supply of appointments, particularly for the often last-minute needs of problem-based visits (Ganguli et al., 2019). With emergency department usage rates increasing 12 percent between 2002 and 2015 (Chou et al., 2019), and people opting for other “convenient care” options, such as urgent care and retail clinics, many people likely prioritize access and immediacy for their acute care, especially outside of typical office hours (Chang et al., 2015; Kangovi et al., 2013; Rocovich and Patel, 2012). The decline in problem-based primary care visits is tellingly largest among low-income communities, which are more affected by increases to out-of-pocket expenses (Ganguli et al., 2020; Rabin et al., 2017).

Confronted by these barriers to care, people may simultaneously perceive diminished need for in-person primary care. The abundance of websites such as WebMD, symptom checkers, and online patient communities may replace formal care, particularly for low-acuity problems (Ganguli et al., 2019). Indeed, primary care offices saw fewer visits regarding easily researched conditions, such as conjunctivitis (Ganguli et al., 2020).

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Primary care in the United States has changed dramatically in recent decades. The changes have eroded its generalist role and led to the consolidation and reduction in its scope and an erosion of its physician workforce, particularly in rural and underserved areas, coupled with the growth of NPs, PAs, CHWs, and other health care workers in primary care. Limited access to primary care in federally designated shortage areas covering much of the country and changes in primary care use all threaten the capacity of primary care to serve the needs of the U.S. population.

REFERENCES

AAFP (American Academy of Family Physicians). 2019. Scope of practice—physicians assistants. Leawood, KS: American Academy of Family Physicians.

AANP (American Association of Nurse Practitioners). 2020. Historical timeline. https://www.aanp.org/about/about-the-american-association-of-nurse-practitioners-aanp/historicaltimeline (accessed October 29, 2020).

AANP. 2021. 2021 nurse practitioner state practice environment. Arlington, VA: American Association of Nurse Practitioners.

ACNM (American College of Nurse-Midwives). 2019. Essential facts about midwives. Silver Spring, MD: American College of Nurse-Midwives.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2012. The distribution of the U.S. primary care workforce. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/primary/pcwork3/index.html (accessed October 28, 2020).

Alcalá, H. E., D. H. Roby, D. T. Grande, R. M. McKenna, and A. N. Ortega. 2018. Insurance type and access to health care providers and appointments under the Affordable Care Act. Medical Care 56(2):186–192.

Alexander, D., J. Currie, and M. Schnell. 2019a. Check up before you check out: Retail clinics and emergency room use. Journal of Public Economics 178:104050.

Alexander, D., J. Currie, M. Schnell, and L. C. McKay. 2019b. Check up before you check out. Chicago, IL: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

AMA (American Medical Association), Ad Hoc Committee on Education for Family Practice, and Council on Medical Education. 1966. Meeting the challenge of family practice (also known as the “Willard Report”). Chicago, IL: American Medical Association.

Ayanian, J. Z., J. S. Weissman, E. C. Schneider, J. A. Ginsburg, and A. M. Zaslavsky. 2000. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA 284(16):2061–2069.

Baker, L. C., M. K. Bundorf, and D. P. Kessler. 2014. Vertical integration: Hospital ownership of physician practices is associated with higher prices and spending. Health Affairs 33(5):756–763.

Basu, S., S. A. Berkowitz, R. L. Phillips, A. Bitton, B. E. Landon, and R. S. Phillips. 2019. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005–2015. JAMA Internal Medicine 179(4):506–514.

Basu, S., R. S. Phillips, R. Phillips, L. E. Peterson, and B. E. Landon. 2020. Primary care practice finances in the United States amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Affairs 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00794.

BLS (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). 2019. Occupational employment and wages, May 2019: 21-1094 community health workers. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes211094.htm (accessed November 24, 2020).

Bond, A., W. Pajerowski, D. Polsky, and M. R. Richards. 2017. Market environment and Medicaid acceptance: What influences the access gap? Health Economics 26(12):1759–1766.

Brown, E. J., D. Polsky, C. M. Barbu, J. W. Seymour, and D. Grande. 2016. Racial disparities in geographic access to primary care in Philadelphia. Health Affairs 35(8):1374–1381.

Brown, E. R., V. D. Ojeda, R. Wyn, and R. Levan. 2000. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to health insurance and health care. Los Angeles, CA: University of California, Los Angeles, Center for Health Policy Research, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Cassel, C. K., and D. B. Reuben. 2011. Specialization, subspecialization, and subsubspecialization in internal medicine. New England Journal of Medicine 364(12):1169–1173.

CCA (Convenient Care Association). 2017. Convenient care clinics: Increasing access. Philadelphia, PA: Convenient Care Association.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2017. What evidence supports state laws to establish community health worker scope of practice and certification? Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Chang, J. E., S. C. Brundage, and D. A. Chokshi. 2015. Convenient ambulatory care—promise, pitfalls, and policy. New England Journal of Medicine 373(4):382–388.

Cheng, E. M., A. Chen, and W. Cunningham. 2007. Primary language and receipt of recommended health care among Hispanics in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22(Suppl 2):283–288.

Chernoff, M., and K. Cueva. 2017. The role of Alaska’s tribal health workers in supporting families. Journal of Community Health 42(5):1020–1026.

Chou, S.-C., A. K. Venkatesh, N. S. Trueger, and S. R. Pitts. 2019. Primary care office visits for acute care dropped sharply in 2002–15, while ED visits increased modestly. Health Affairs 38(2):268–275.

CHroniCles. 2020. Health centers then & now. https://www.chcchronicles.org/histories (accessed October 8, 2020).

Citizens Commission on Graduate Medical Education. 1966. The graduate education of physicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2019. Chapter 13—rural health clinic (RHC) and federally qualified health center (FQHC) services. In Medicare benefit policy manual. Washington, DC: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Czeisler, M., K. Marynak, K. E. N. Clarke, Z. Salah, I. Shakya, J. M. Thierry, N. Ali, H. McMillan, J. F. Wiley, M. D. Weaver, C. A. Czeisler, S. M. W. Rajaratnam, and M. E. Howard. 2020. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19related concerns—United States, June 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69(36):1250–1257.

Dalen, J. E., K. J. Ryan, and J. S. Alpert. 2017. Where have the generalists gone? They became specialists, then subspecialists. The American Journal of Medicine 130(7):766–768.

DeVoe, J. E. 2020. Primary care is an essential ingredient to a successful population health improvement strategy. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 33(3):468–472.

Douthit, N., S. Kiv, T. Dwolatzky, and S. Biswas. 2015. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health 129(6):611–620.

Dunn, A., and A. H. Shapiro. 2014. Do physicians possess market power? The Journal of Law & Economics 57(1):159–193.

Epstein, D. 2019. Range: Why generalists triumph in a specialized world. New York: Macmillan Publishers.

FAIR Health. 2015. FAIR health survey: Viewpoints about ER use for non-emergency care vary significantly by race, age, education and income. New York: PRNewswire.

Ferrer, R. L., S. J. Hambidge, and R. C. Maly. 2005. The essential role of generalists in health care systems. Annals of Internal Medicine 142(8):691–699.

Ford, L. C. 1979. A nurse for all settings: The nurse practitioner. Nursing Outlook 27(8): 516–521.

Freeman, J. D., S. Kadiyala, J. F. Bell, and D. P. Martin. 2008. The causal effect of health insurance on utilization and outcomes in adults: A systematic review of U.S. studies. Medical Care 46(10):1023–1032.

Frost, A., and J. Hargraves. 2018. HCCI brief: Trends in primary care visits. Washington, DC: Health Care Cost Institute.

Frost, A., J. Hargraves, and S. Rodriguez. 2018. 2016 health care cost and utilization report. Washington, DC: Health Care Cost Institute.

Fulton, B. D. 2017. Health care market concentration trends in the United States: Evidence and policy responses. Health Affairs 36(9):1530–1538.

Ganguli, I., T. H. Lee, and A. Mehrotra. 2019. Evidence and implications behind a national decline in primary care visits. Journal of General Internal Medicine 34(10):2260–2263.

Ganguli, I., Z. Shi, E. J. Orav, A. Rao, K. N. Ray, and A. Mehrotra. 2020. Declining use of primary care among commercially insured adults in the United States, 2008–2016. Annals of Internal Medicine 172(4):240–247.

Gleason, R. P., and S. M. Kneipp. 2004. Employment-related constraints: Determinants of primary health care access? Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice 5(2):73–83.

Gong, G., S. G. Phillips, C. Hudson, D. Curti, and B. U. Philips. 2019. Higher U.S. rural mortality rates linked to socioeconomic status, physician shortages, and lack of health insurance. Health Affairs 38(12):2003–2010.

Grand View Research. 2017. U.S. Retail clinics market size, share & trends analysis report by ownership type (retail-owned, hospital-owned), competitive landscape, and segment forecasts, 2018–2025. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/us-retail-clinics-market (accessed October 29, 2020).

Gunn, J. M., V. J. Palmer, L. Naccarella, R. Kokanovic, C. J. Pope, J. Lathlean, and K. C. Stange. 2008. The promise and pitfalls of generalism in achieving the Alma-Ata vision of health for all. The Medical Journal of Australia 189(2):110–112.

Hadley, J. 2003. Sicker and poorer—the consequences of being uninsured: A review of the research on the relationship between health insurance, medical care use, health, work, and income. Medical Care Research and Review 60(Suppl 2):3S–75S; discussion 76S–112S.

HHS, HRSA, and NCHWA (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, and National Center for Health Workforce Analysis). 2020. Characteristics of the U.S. nursing workforce with patient care responsibilities: Resources for epidemic and pandemic response. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration.

HRSA. 2020. Shortage areas. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas (accessed August 20, 2020).

HRSA and NCHWA. 2016. National and regional projections of supply and demand for primary care practitioners: 2013–2025. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration.

Hsiang, W. R., A. Lukasiewicz, M. Gentry, C. Y. Kim, M. P. Leslie, R. Pelker, H. P. Forman, and D. H. Wiznia. 2019. Medicaid patients have greater difficulty scheduling health care appointments compared with private insurance patients: A meta-analysis. Inquiry: A Journal of Medical Care Organization, Provision and Financing 56:46958019838118.

Huang, E. S., and K. Finegold. 2013. Seven million Americans live in areas where demand for primary care may exceed supply by more than 10 percent. Health Affairs 32(3):614–621.

International Conference on Primary Health Care. 1978. Declaration of Alma-Ata. Alma-Ata, USSR: World Health Organization.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1996. Primary care: America’s health in a new era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2011. The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Johnson, J. E. 2013. Working together in the best interest of patients. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice 26(3):241–243.

Kane, C. K. 2019. Updated data on physician practice arrangements: For the first time, fewer physicians are owners than employees. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association.

Kangovi, S., F. K. Barg, T. Carter, J. A. Long, R. Shannon, and D. Grande. 2013. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Affairs 32(7):1196–1203.

Kangovi, S., N. Mitra, D. Grande, J. A. Long, and D. A. Asch. 2020. Evidence-based community health worker program addresses unmet social needs and generates positive return on investment. Health Affairs 39(2):207–213.

Kim, B., M. A. Lucatorto, K. Hawthorne, J. Hersh, R. Myers, A. R. Elwy, and G. D. Graham. 2015. Care coordination between specialty care and primary care: A focus group study of provider perspectives on strong practices and improvement opportunities. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 8:47–58.

Kim, L. Y., D. E. Rose, L. M. Soban, S. E. Stockdale, L. S. Meredith, S. T. Edwards, C. D. Helfrich, and L. V. Rubenstein. 2018. Primary care tasks associated with provider burnout: Findings from a Veterans Health Administration survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine 33(1):50–56.

Koch, T., B. Wendling, and N. E. Wilson. 2018. Physician market structure, patient outcomes, and spending: An examination of Medicare beneficiaries. Health Services Research 53(5):3549–3568.

Krahn, G. L., L. Hammond, and A. Turner. 2006. A cascade of disparities: Health and health care access for people with intellectual disabilities. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 12(1):70–82.

Liebhaber, A., and J. M. Grossman. 2007. Physicians moving to mid-sized, single-specialty practices. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change.

Loxterkamp, D. 1991. Being there: On the place of the family physician. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice 4(5):354–360.

Loxterkamp, D. 2009. Doctors’ work: Eulogy for my vocation. Annals of Family Medicine 7(3):267–268.

Manchanda, R. 2015. Practice and power: Community health workers and the promise of moving health care upstream. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management 38(3):219–224.

McWhinney, I. R. 1989. “An acquaintance with particulars...” Family Medicine 21(4):296–298.

Mercer, S. W., and J. G. Howie. 2006. CQI-2—a new measure of holistic interpersonal care in primary care consultations. British Journal of General Practice 56(525):262–268.

Miller, W. L., B. F. Crabtree, M. B. Duffy, R. M. Epstein, and K. C. Stange. 2003. Research guidelines for assessing the impact of healing relationships in clinical medicine. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 9(3):A80–A95.

Montgomery, L., S. Loue, and K. C. Stange. 2017. Linking the heart and the head: Humanism and professionalism in medical education and practice. Family Medicine 49(5):378–383.

Morley, J. E. 2004. A brief history of geriatrics. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 59(11):1132–1152.

Muhlestein, D. B., and N. J. Smith. 2016. Physician consolidation: Rapid movement from small to large group practices, 2013–15. Health Affairs 35(9):1638–1642.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Assessing progress on the Institute of Medicine report The Future of Nursing. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Commission on Community Health Services. 1967. Health is a community affair: Report of the National Commission on Community Health Services. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Naylor, M. D., and E. T. Kurtzman. 2010. The role of nurse practitioners in reinventing primary care. Health Affairs 29(5):893–899.

NCCPA (National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants). 2020. 2019 statistical profile of certified physician assistants. Johns Creek, GA: National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants.

Nouri, S., E. C. Khoong, C. R. Lyles, and L. Karliner. 2020. Addressing equity in telemedicine for chronic disease management during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0123 (accessed January 8, 2021).

NRMP (National Resident Matching Program). 2020. Results and data: 2020 main residency match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program.

O’Connor, P. J., J. M. Sperl-Hillen, K. L. Margolis, and T. E. Kottke. 2017. Strategies to prioritize clinical options in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine 15(1):10–13.

Olaisen, R. H., M. D. Schluchter, S. A. Flocke, K. A. Smyth, S. M. Koroukian, and K. C. Stange. 2020. Assessing the longitudinal impact of physician-patient relationship on functional health. Annals of Family Medicine 18(5):422–429.

O’Malley, A. S., D. Samuel, A. M. Bond, and E. Carrier. 2012. After-hours care and its coordination with primary care in the U.S. Journal of General Internal Medicine 27(11): 1406–1415.

Orcutt, V. L. 2015. Exploring physician assistant data sources. Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants 28(8):49–50, 52–56.

PAI (Physicians Advocacy Institute) and Avalere Health. 2019. Updated physician practice acquisition study: National and regional changes in physician employment 2012–2018. Austin, TX: Physicians Advocacy Institute.

Palmer, V. J., L. Naccarella, and J. M. Gunn. 2007. Are you my generalist or the specialist of my care? The New Zealand Family Physician 34(6).

Peterson, L. E., R. L. Phillips, J. C. Puffer, A. Bazemore, and S. Petterson. 2013. Most family physicians work routinely with nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or certified nurse midwives. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 26(3):244–245.

Petterson, S., R. McNellis, K. Klink, D. Meyers, and A. Bazemore. 2018. The state of primary care in the United States: A chartbook of facts and statistics. Washington, DC: Robert Graham Center.

Ponce, N. A., R. D. Hays, and W. E. Cunningham. 2006. Linguistic disparities in health care access and health status among older adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(7):786–791.

Rabin, D. L., A. Jetty, S. Petterson, Z. Saqr, and A. Froehlich. 2017. Among low-income respondents with diabetes, high-deductible versus no-deductible insurance sharply reduces medical service use. Diabetes Care 40(2):239–245.

RAND. 2016. The evolving role of retail clinics. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Rao, A., Z. Shi, K. N. Ray, A. Mehrotra, and I. Ganguli. 2019. National trends in primary care visit use and practice capabilities, 2008–2015. Annals of Family Medicine 17(6):538–544.

Ray, K. N., Z. Shi, I. Ganguli, A. Rao, E. J. Orav, and A. Mehrotra. 2020. Trends in pediatric primary care visits among commercially insured U.S. children, 2008–2016. JAMA Pediatrics 174(4):350–357.

Reddy, S. R., D. Ross-Degnan, A. M. Zaslavsky, S. B. Soumerai, and J. F. Wharam. 2014. Impact of a high-deductible health plan on outpatient visits and associated diagnostic tests. Medical Care 52(1):86–92.

Reid, R. O., J. S. Ashwood, M. W. Friedberg, E. S. Weber, C. M. Setodji, and A. Mehrotra. 2012. Retail clinic visits and receipt of primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 28(4):504–512.

Rocovich, C., and T. Patel. 2012. Emergency department visits: Why adults choose the emergency room over a primary care physician visit during regular office hours? World Journal of Emergency Medicine 3(2):91–97.

Sabo, S., C. G. Allen, K. Sutkowi, and A. Wennerstrom. 2017. Community health workers in the United States: Challenges in identifying, surveying, and supporting the workforce. American Journal of Public Health 107(12):1964–1969.

Scott, J. G., D. Cohen, B. Dicicco-Bloom, W. L. Miller, K. C. Stange, and B. F. Crabtree. 2008. Understanding healing relationships in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine 6(4):315–322.

Shanafelt, T. D., S. Boone, L. Tan, L. N. Dyrbye, W. Sotile, D. Satele, C. P. West, J. Sloan, and M. R. Oreskovich. 2012. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among U.S. physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Archives of Internal Medicine 172(18):1377–1385.

Sharac, J., P. Shin, R. Gunsalus, and S. Rosenbaum. 2018. Community health centers continued to expand patient and service capacity in 2017. Washington, DC: Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health Policy, RCHN Community Health Foundation.

Sinaiko, A. D., M. B. Landrum, D. J. Meyers, S. Alidina, D. D. Maeng, M. W. Friedberg, L. M. Kern, A. M. Edwards, S. P. Flieger, P. R. Houck, P. Peele, R. J. Reid, K. McGraves-Lloyd, K. Finison, and M. B. Rosenthal. 2017. Synthesis of research on patient-centered medical homes brings systematic differences into relief. Health Affairs 36(3):500–508.

Souch, J. M., and J. S. Cossman. 2020. A commentary on rural-urban disparities in COVID-19 testing rates per 100,000 and risk factors. Journal of Rural Health 37(1):188–190.

Stange, K. C. 2002. The paradox of the parts and the whole in understanding and improving general practice. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 14(4):267–268.

Stange, K. C. 2009a. The generalist approach. Annals of Family Medicine 7(3):198–203.

Stange, K. C. 2009b. A science of connectedness. Annals of Family Medicine 7(5):387–395.

Stange, K. C. 2010. Ways of knowing, learning, and developing. Annals of Family Medicine 8(1):4–10.

Stange, K. C. 2018. In this issue: Continuity, relationships, and the illusion of a steady state. Annals of Family Medicine 16(6):486–487.

Stange, K. C., W. L. Miller, and I. McWhinney. 2001. Developing the knowledge base of family practice. Family Medicine 33(4):286–297.

Stevens, R. A. 2001. The Americanization of family medicine: Contradictions, challenges, and change, 1969–2000. Family Medicine 33(4):232–243.

Tolbert, J., and K. Orgera. 2020. Key fact about the uninsured population. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population (accessed January 19, 2021).

UCA (Urgent Care Association). 2019. Urgent care industry white paper: The essential role of the urgent care center in population health. Warrenville, IL: Urgent Care Association.

Velasquez, D., and A. Mehrotra. 2020. Ensuring the growth of telehealth during COVID-19 does not exacerbate disparities in care. Health Affairs Blog (May 8). https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200505.591306/full (accessed January 8, 2021).

Wang, Z., and K. Tang. 2020. Combating COVID-19: Health equity matters. Nature Medicine 26(4):458.

Weinick, R. M., C. E. Pollack, M. P. Fisher, E. M. Gillen, and A. Mehrotra. 2011. Policy implications of the use of retail clinics. RAND Health Quarterly 1(3):9.

WHO and UNICEF (World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund). 2018. Declaration of Astana. Astana, Kazakhstan: World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund.

Xue, Y., J. A. Smith, and J. Spetz. 2019. Primary care nurse practitioners and physicians in low-income and rural areas, 2010–2016. JAMA 321(1):102–105.

This page intentionally left blank.