2

Rural America in Context

The first session of the workshop focused on providing context, including the demographics and social determinants of health (SDOH) in rural America, as well as the effect of structural urbanism on health care access and delivery and other challenges related to the health care infrastructure in rural areas. The session was moderated by Lars Peterson from the Rural & Underserved Health Research Center at the University of Kentucky.

RURAL DEMOGRAPHICS AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Alana Knudson from the Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis at NORC at the University of Chicago highlighted relevant demographic features of rural communities in the United States. SDOH—including poverty, unemployment, lack of affordable housing, and food insecurity—are challenges facing rural America. She noted that SDOH intersect with race and age, putting some rural subgroups at greater risk for unmet needs, including children, African Americans, and Native Americans.

Demographics of Rural America

Knudson provided an overview of the demographics of rural America, which differ substantially from urban America in terms of age distribution,

race, ethnicity, and the effects of migration. Approximately 60 million people in the United States—representing about one-fifth of the national population—live in rural areas.1

Older Adults in Rural and Nonrural Areas

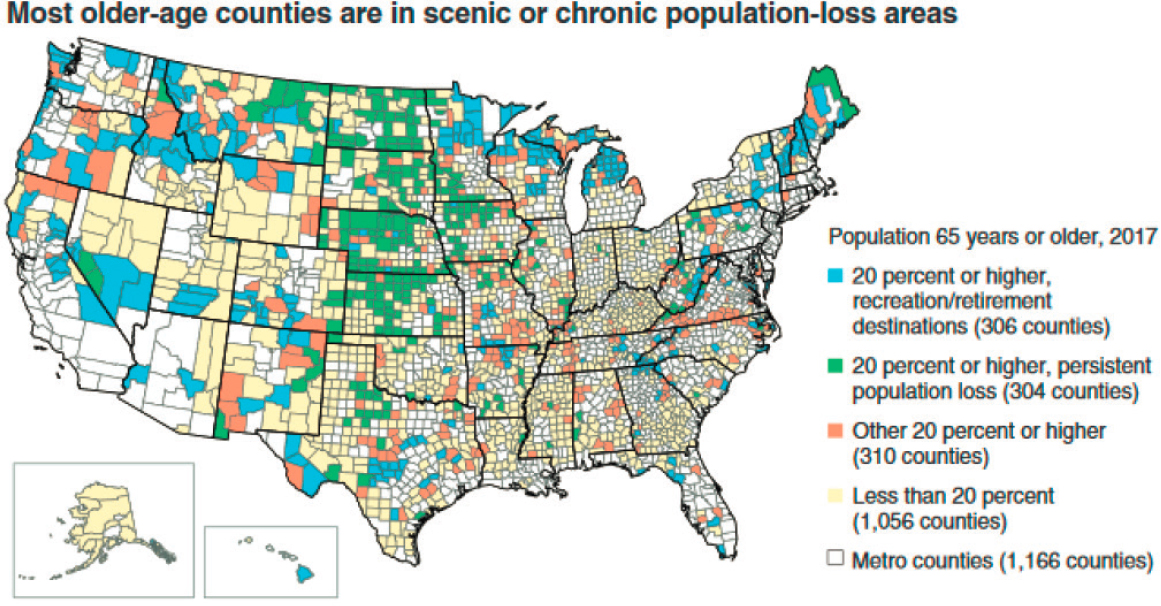

A striking difference between rural and urban populations is reflected in their age distributions, said Knudson. Forty years ago, the percentage of Americans aged 65 years and older was smaller in rural areas than in urban settings. However, the past four decades have seen a dramatic shift in those proportions, with older adults now representing approximately 18 percent of the rural population and 14 percent of the urban population.2 As of 2016, almost one out of every five rural residents was aged 65 years or older. This demographic shift toward older populations creates both opportunities and challenges for rural communities. In this respect, it is relevant to consider the areas where older adults in rural areas tend to reside in the United States. Knudson added that in 2017, most rural counties in which more than 20 percent of the population was aged 65 years or older were located in scenic areas or areas with chronic population loss (see Figure 2-1).3 Many older Americans retire in rural areas that are recreation or retirement destinations. Additionally, many rural counties have had persistent population loss over the past 40 years attributable to younger people migrating from rural communities to urban areas in search of jobs. In geographical terms, the distribution of rural elderly populations is somewhat different than in metropolitan (metro)4 communities. This is evident in the concentration of counties with a high proportion of older residents in the central Great Plains and in the West, she added.

___________________

1 More information about rural America is available at https://gis-portal.data.census.gov/arcgis/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=7a41374f6b03456e9d138cb014711e01 (accessed August 6, 2020).

2 Rural population data from U.S. Census. More information about U.S. Census data is available at https://data.census.gov/cedsci (accessed July 17, 2020).

3 Rural county data from the Economic Research Service at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. For more information about rural county data, see https://www.ers.usda.gov (accessed July 17, 2020).

4 Knudson noted that a challenge in rural health research is that rural is often referred to as nonmetro, as is the case with the data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. She added that some rural health researchers would like to shift that terminology by comparing rural and nonrural areas.

SOURCES: Knudson presentation, June 24, 2020; Economic Research Service at the U.S. Department of Agriculture using data from the U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates program.

Race and Ethnicity in Rural and Nonrural Areas

Stark differences between rural and nonrural populations also emerge when looking at race and ethnicity, said Knudson. For instance, metro areas tend to have higher concentrations of racial and ethnic minorities. According to 2017 data, nonwhite residents made up about 42 percent of the metro population compared to 22 percent of the rural population (Cromartie, 2018). Racial and ethnic differences in rural populations also emerge when analyzed by age distribution, she added.

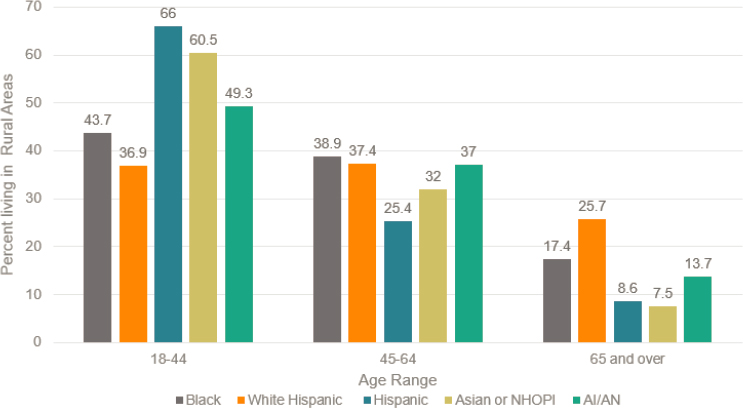

Knudson described sociodemographic information from 2012 to 2015 on the sociodemographic characteristics of adults aged 18 years or more in rural areas in the United States by race and ethnicity. She explained that more non-Hispanic whites (25.7 percent) aged 65 and older were living in rural areas than other racial and ethnic groups (non-Hispanic Blacks: 17.4 percent; American Indians and Alaska Natives: 13.7 percent; Hispanics: 8.6 percent; Asians and Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders: 7.5 percent) (James et al., 2017). In contrast, more Hispanic adults (66.0 percent) aged 18–44 were living in rural areas than other racial and ethnic groups (Asians and Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders: 60.5 percent; Native Americans/Alaska Natives: 49.3 percent; non-Hispanic Blacks: 43.7 percent; non-Hispanic whites: 36.9 percent) (see Figure 2-2). Knudson noted that over the past 20 years, the greatest growth in racial and ethnic representation in rural communities has occurred among the Hispanic, American Indian, and Alaska Native populations.

Effect of Migration

Knudson explained that changes in migration patterns have also occurred across the country in the past decade.5 Many of the rural areas that have seen an increase in net migration rates are destination areas with recreational opportunities, particularly in the West, which are areas that also tend to draw people moving or relocating for retirement. Changes in employment opportunities have also led to migration shifts. For example, population changes from 2012 to 2013 and from 2016 to 2017 correspond to shifts in energy extraction in areas such as the northern part of North Dakota and the eastern Montana border, where a change in oil prices led to the evaporation of jobs and subsequently to a large loss of population. Knudson noted that another shift is ongoing in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, with some urban residents leaving for second homes located in rural areas. She noted that as people

___________________

5 Rural net migration patterns from the Economic Research Service at the U.S. Department of Agriculture using data from the U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates program. More information is available at https://www.ers.usda.gov (accessed July 17, 2020).

NOTE: AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; NHOPI = Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.

SOURCE: Knudson Presentation, June 23, 2020.

demonstrate that it is possible to successfully work remotely, many may decide to reside primarily outside of the larger urban areas. Knudson suggested that in 4 years, the migration map may look different because of COVID-19.

Social Determinants of Health

Knudson explained that in the domain of public health, the SDOH are often conceptualized in terms of where people live, learn, work, play, and pray and how those factors contribute to people’s health and well-being. Specifically, the SDOH are the neighborhood and built environment, health and health care, the social and community context, education, and economic stability.6 To explore the effect of economic stability on the health and well-being of people in rural areas, she noted that “wealth equals health.” Earning a livable wage with compensation that enables access to affordable health care and health insurance is a foundational component of good health and well-being.

___________________

6 Categories of SDOH as defined by the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion are available at https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health (accessed July 21, 2020).

Trends in employment rates from 2007 to 2019 differ in rural and urban areas, said Knudson.7 During the economic recession from late 2007 to mid-2009, rural and urban employment rates were comparable. By 2014, urban employment rates had rebounded to prerecession levels. However, growth in rural employment rates has been slower to rebound; by 2019, the rates had not yet reached the 2007 levels. The COVID-19 pandemic is continuing to harm small businesses, which will likely pose additional challenges to achieving prerecession employment levels in rural areas. Similarly, rural areas have struggled to achieve reductions in poverty rates that have been attained in metro areas, said Knudson. The mid-20th century saw a sizeable decrease in the nonmetro poverty rate, which dropped from 33.2 percent to 17.9 percent between 1959 and 1969.8 However, rural communities have never attained the same level of affluence as urban communities.

In 2018, the poverty rate for nonmetro residents was 16.1 percent compared to 12.6 percent for metro residents. Poverty rates vary in different rural areas across the country, with greater percentages of rural communities living in poverty concentrated in Appalachia, along the Mississippi Delta, in some areas of border states, in areas in the West predominantly populated by American Indian tribal communities, and in Alaska Native communities.9 Rural communities are also disproportionately affected by persistent poverty, which has long-lasting implications for health and well-being, she added. Counties with persistent poverty are those in which at least 20 percent of county residents have been poor for the previous four decades.10 Concentrations of rural counties experiencing persistent poverty are found in Appalachia, in the South, along the Mississippi Delta, along the U.S.–Mexico border, and tribal lands inhabited by American Indians and Alaska Natives.

Knudson described how racial and ethnic disparities intersect with geographic disparities in wealth. In 2018, rural residents who were African American, American Indian, or Alaska Native experienced the highest

___________________

7 Rural and urban employment data from the Economic Research Service at the U.S. Department of Agriculture using data from the Local Area Unemployment Statistics at the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. More information is available at https://www.ers.usda.gov (accessed July 17, 2020).

8 More information on poverty and well-being is available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being/#historic (accessed July 17, 2020).

9 See https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/saipe/#/?map_geoSelector=aa_c (accessed November 28, 2020).

10 More information on populations in poverty by county is available at https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/saipe/#/?map_geoSelector=aa_c (accessed July 17, 2020).

rates of poverty among people in the United States.11 Across all racial and ethnic populations, a greater percentage of rural residents live in poverty compared to their urban counterparts. This trend also presents in poverty rates among children under the age of 5 years, with 25 percent of those children living in poverty in rural areas compared to 18.6 percent in urban areas.12 Across the entire continuum of age distributions, greater percentages of rural residents live in poverty than urban residents. Residents of rural communities also tend to face challenges with respect to food security and housing affordability, she noted. People living more than 30 miles from a grocery store are considered to have low access to grocery stores.13 The highest percentages of people with low grocery store access are concentrated in central and western parts of the country, which are areas that tend to be more sparsely populated. Similarly, central and western rural regions feature some of the least affordable housing options based on the ratio of housing prices to income.14 The Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis at NORC at the University of Chicago looked at the ability of Missouri residents to maintain housing and found that although housing prices were affordable, the cost of electricity was not. This is one example of the multiple factors that determine whether rural residents are able to maintain safe and affordable housing.

Knudson remarked that many challenges faced by rural America can be addressed through innovative local solutions that leverage the strong resilience of many rural communities. Among ongoing efforts is the Rural Health Information Hub, which provides comprehensive tool kits to address the SDOH in rural communities.15

___________________

11 Poverty rates by metro and nonmetro residence from the Economic Research Service at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. More information on poverty and well-being is available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-povertywell-being/#historic (accessed July 17, 2020).

12 Poverty rates by age and metro and nonmetro residence from the Economic Research Service at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. More information on poverty and well-being is available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-povertywell-being/#historic (accessed July 17, 2020).

13 Data on grocery store access from the Economic Research Service at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. More information is available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-environment-atlas/go-to-the-atlas (accessed July 17, 2020).

14 More information on rural housing affordability is available at https://oregoneconomicanalysis.com/2017/02/09/rural-housing-affordability (accessed July 17, 2020).

15 Additional information from the Rural Health Information Hub and the Social Determinants of Health in Rural Communities Toolkit can be found at https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/sdoh (accessed November 28, 2020).

STRUCTURAL URBANISM IN RURAL AMERICA

Janice Probst from the Rural & Minority Health Research Center at the Arnold School of Public Health at the University of South Carolina discussed mortality rates and race-based health disparities in rural America. She stated that data on rural communities should be examined with an awareness of “structural urbanism,” a framework for addressing health issues that unintentionally and systematically discriminates against rural populations. Probst explained how structural urbanism and current funding mechanisms systematically disadvantage rural populations and negatively affect their health outcomes.

Effect of Structural Urbanism on Direct Health Care Services

Probst said that structural urbanism underlies the health issues facing rural areas. She defined this concept as “a bias toward large population centers that emerges from a focus on individuals rather than infrastructure when designing health care and public health interventions.” For example, proposals for programs currently receiving public attention, such as Medicaid expansion and Medicare for All, tend to focus on individual needs rather than on infrastructure and population-level needs. One of the last major investments in health services infrastructure was the Hill-Burton program, which was in effect from 1946 to 1997 and funded the construction of hospitals and other health care facilities based on community need. The focus since then has almost exclusively centered on extending the ability of individuals to pay for care, she noted. The Medicare and Medicaid programs of 1965, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, and the 2014 Medicaid expansion were all designed to provide individuals with the ability to acquire health care. Whether the programs were aimed at covering fee-for-service or capitation, each focused on providing the ability to acquire health care one individual at a time, rather than building health care infrastructure.

Probst asserted that funding mechanisms reimbursing direct health care services provided to individuals will never serve small populations fairly—this includes funding mechanisms relating to Medicare for All, capitation, value-based care, and other health system “tweaks” that may be proposed to address rural health. For instance, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission has deemed home health care providers to be an inefficient service delivery model due to the long drive times between patients (MedPAC, 2017). The characteristics of rural populations make adequate service delivery within the current system’s structure unattainable, Probst added.

The focus on providing health care to individuals fails because of problems of scale and undermines the provision of health care and public health services in rural settings, said Probst. Most health care models, including fee-for-service and capitation models, require a minimum number of funded participants to be viable under current financing mechanisms. Sparsely populated rural areas are at a disadvantage in systems that operate on scale. Similarly, public health’s focus on national goals obscures local problems and small populations. Because of the requirements for a minimum number of funded participants and the focus on attaining national goals, rural communities are often excluded from public health programs, she explained.

Probst noted that some resources contend that a physician’s office in a private-pay health care system requires an estimated 1,900–2,500 patients to operate successfully.16 Small populations generally cannot provide this number of patients to a single office, which discourages practitioners from opening offices in rural areas. Metropolitan counties in the United States have an average of 53 primary care physicians per 100,000 people, but rural counties average just 39 physicians per 100,000 people.17 Probst suggested that this type of à la carte system through which individuals purchase health care one service at a time results in a lack of care for people who need it in some geographic areas. An example of this health care shortage in rural areas is the limited availability of intensive care units (ICUs) in many areas. In response to rising concerns about the lack of ICU beds amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and Kaiser Health news mapped the availability of ICU beds by county across the rural regions of America. The geographic analysis revealed that numerous counties either have only hospitals without ICU beds or no hospitals at all.18 It has been argued that small counties may not require their own hospitals or hospitals with ICU beds, she noted. However, the effect of structural urbanism also extends to smaller, billable services such as education activities for patients with chronic conditions.

___________________

16 The presenter provided the following resource as a reference: https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/6-keys-profitability (accessed October 28, 2020).

17 More information about rural health care workforce shortages, socioeconomic factors, and health inequity is available at https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/about-nrha/about-rural-health-care (accessed July 31, 2020).

18 More information is available at https://khn.org/news/as-coronavirus-spreads-widely-millions-of-older-americans-live-in-counties-with-no-icu-beds (accessed July 17, 2020).

Effect of Structural Urbanism on Diabetes Management—an Example

The effect of lack of access to hospital care extends to the management of chronic conditions, explained Probst. Diabetes is an example of a disease that is primarily managed by patients, but treatment for diabetes is not intuitive or as simple as taking a pill—it requires the monitoring of glucose and insulin levels. Patients require education to effectively manage this disease, which is a billable service under Medicare and Medicaid, but there is a shortage of patient education programs in rural areas because the health system is funded via individualized payments. Diabetes is highly prevalent among adults in the United States, affecting approximately 9 percent of urban and 9.9 percent of rural adults. Multiple compositional factors influence health outcomes for the rural population; this results in a higher risk of death for people with diabetes who live in rural areas. These causative factors include lower levels of education and lower health insurance rates in rural America. Contextual factors emerge because the infrastructure for patient education must be built “one paying person at a time,” she added. For instance, 62 percent of rural counties do not have a single diabetes management education program, even though certifying diabetes educators is fairly simple, and physicians could also be trained to provide these services (Rutledge et al., 2017).

This shortage persists despite the large burden of diabetes in many regions across the United States, with death rates higher for rural residents with diabetes across racial and ethnic groups. According to 2017–2018 data, for example, adults with diabetes living in rural areas had an age-adjusted death rate per 100,000 population that was 46 percent higher than their urban counterparts for people aged 25–64 years and about 24 percent higher for adults aged 65 years or older, according to Probst’s analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data.19 These disparities in death rates for people in urban versus rural areas also extend to racial and ethnic minorities. Probst contended that although the lack of diabetes education programs is not the sole cause for this increased risk of mortality, greater local availability of certified diabetes educators—which could be achieved by simply training existing physicians—could help address this issue.

___________________

19 Author’s analysis of data from CDC Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 2017–2018 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2020. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. See http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html (accessed June 9, 2020).

Effect of Structural Urbanism on Public Health

Rural Visibility in National Data

The shortcomings of approaches that focus on individuals apply to public health as well, said Probst. Health outcomes in rural areas often have poor visibility in national-level data. For instance, national goals set by large agencies, such as the Healthy People 2020 agenda, often feature national averages without the analysis of subgroup data that is needed to accurately assess the success of public health initiatives. To illustrate, Probst noted that the Healthy People 2020 national targets for child mortality had been met for four out of five age groups by 2017 (Khan et al., 2018). Without examining subgroup data, it appears that efforts to reduce child mortality rates have been successful. However, analysis of mortality rates for rural youth—which are higher than national averages—reveals that the Healthy People 2020 targets had not been achieved for youth in any of the five age brackets (Probst et al., 2019).

Plans for national success based on aggregate individual-level data neglect rural surveillance, said Probst. For example, CDC’s Health, United States, 2017 report contains 144 tables, but only 19 percent presented outcomes for rural populations (NCHS, 2018). In addition to the lack of rural surveillance, a focus on numbers instead of severity restricts rural opportunities for improvement. For instance, during the 2015 HIV outbreak in Scott County, Indiana, 150 people contracted HIV/AIDS. This translates to a population-based statistic of 630 per 100,000 people, which was well above the national average of 421 per 100,000 in 2016 (Gonsalves and Crawford, 2018). Looking only at case numbers masks the high rate of infection in such a small county. Funding restrictions further limit opportunities to improve rural health, said Probst. South Carolina faced challenges in competing for the 2011–2014 CDC community transformation grants because eligibility required a minimum population of 500,000. This grant structure excluded rural areas and required the development of a program proposal to serve the entire state in order to be eligible to bid.

Effect of COVID-19 on Structural Challenges in Rural Care

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified these structural problems, said Probst. Small health care facilities in rural areas are facing substantial economic hardships because of declining person-based payments. Community health centers have reported declines of income of 70–80 percent (Wright et al., 2021). Stay-at-home orders associated with the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in a nationwide decline in physician office visits (Rubin, 2020), and some rural hospitals have needed to furlough staff

because of the decline in elective procedures.20 She noted that smaller facilities have been disproportionately affected by declining person-based payments and declining physician office visits, and the person-based payment system in the United States provides no clear path to recovery for rural health facilities. When rural hospitals and physician offices close, there are no mechanisms to bring these jobs and services back to the communities they serve after the pandemic. Probst warned that without substantial changes to the ways that rural health care is delivered and funded, the COVID-19 pandemic could potentially decimate rural America’s entire health infrastructure.

Health Care as Infrastructure: Framework for Change

As a framework for change to address the barriers posed by structural urbanism, Probst suggested framing health care as essential infrastructure within a community. To illustrate, she contrasted the support provided to small, underresourced communities to develop transportation and power infrastructures with the lack of support those communities receive to develop health infrastructure. Loving County, Texas, has 169 residents and could not afford to pave its own roads or build electrical infrastructure without state and national funding support, which is provided because state and local governments recognize that these services are essential for all communities regardless of whether counties can afford them independently. Probst maintained that health care should be similarly framed as essential community infrastructure required for residents’ health and well-being, rather than as a discretionary purchase made by an individual. This paradigm shift would construe health care as (1) a characteristic of a community rather than a service accessed by an individual, (2) responsive to community needs, and (3) funded as a utility via taxation and/or regulated fees that maintain services for all populations in need. Changing the funding mechanisms would shift determinations about service provision. Under a framework where health was funded as a utility, a hospital that would previously have been considered “not viable under current, centrally determined rates” would not be closed. Instead, reimbursement rates would be sufficient to maintain the institution’s viability, and communities would continue to have access to the health care services it provides. This new framework would also help to protect industry in smaller communities, added Probst. Many companies are reluctant to operate in areas without hospitals because the lack of

___________________

20 More information about rural hospital staff furlough is available at https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/10-hospitals-furloughing-staff-in-response-to-covid-19.html (accessed July 17, 2020).

hospital access complicates emergency care access and thus may affect worker’s compensation requirements.

Probst acknowledged the difficulties involved in such a fundamental shift in the framework for health care delivery and funding. For instance, determining how to allocate funding and determine the levels of need can be challenging and contentious, even in countries with central health services, such as Great Britain. Additionally, defining the geographic coverage areas for supporting health care is complex—it can be done by state, region, or a combination. For instance, the Tennessee Valley Authority covers parts of seven states, while the Delta Valley Authority includes eight states within the Mississippi Delta.21 Despite the challenges involved in driving change, “the consequences of failure to strengthen the faltering rural health care infrastructure would be much worse,” said Probst. She then added that the United States will not be internationally competitive without a strong rural base for extractive and small manufacturing industries. Rural health care is in decline, and the communities that lose their health infrastructure are often the communities that are most in need. A focus on communities and building their health infrastructure offers one path forward, she said.

DISCUSSION

Funding Health Care as a Utility

The discussion section of the session was moderated by Lars Peterson, who shared impressions and posed questions from the public. Peterson remarked that one of the issues facing rural hospitals is a higher fixed cost for low patient volumes, which can lead to hospital closures. He asked Probst if the model she outlined would provide subsidies or enhanced payments to low-volume hospitals. While other mechanisms may be feasible, Probst said that the mechanism she envisions is that of enhanced payments, but these payments must be thought of in a new manner. She drew a comparison between health care and public education. Every state constitution requires education to be provided to all children, with a mixture of local and state funds allocated to schools. Without this mixed-funding stream, rural schools would not be viable. Rural hospitals encounter higher fixed costs because of the need for hospitals to be a certain size and the relatively smaller patient populations in rural areas. In education, similar challenges have been addressed by

___________________

21 See Tennessee Valley Authority, About TVA, available at https://www.tva.com/about-tva (accessed October 28, 2020), and Delta Regional Authority, DRA States, available at https://dra.gov/about-dra/dra-states (accessed October 28, 2020).

treating education as a utility. Probst emphasized that building electrical infrastructure in small counties is not cost-effective, but the need for such infrastructure is broadly accepted. Thus, she advocates for a new funding mechanism that would treat health care as a public utility.

She said that the current health infrastructure model provides no control over hospital location; hospitals are free to close or relocate at will. In contrast, electric companies are regulated utilities that cannot opt to cease serving rural areas. Peterson brought up the issue of state funding of roads, with states sometimes allocating funds to larger population centers instead of rural areas. He asked whether restructuring health care as infrastructure might lead to urban areas receiving better maintained facilities than rural areas. Probst acknowledged that to be a risk but noted that at least there is a political process for such issues to be addressed, unlike a system managed by private equity companies in which citizens have no voice.

Challenges and Opportunities of Age-Based Migration

Citing Knudson’s demographic data regarding the higher concentration of older adults in rural areas resulting from youth migration, Peterson asked her to expound on the associated opportunities and challenges. Knudson replied that the lack of an adequate health care workforce to support the population’s needs is a challenge faced by communities with a higher proportion of older adults. To illustrate, she described a rural hospital in North Dakota that closed its nursing home wing, in spite of having a waiting list of potential residents, because of a workforce shortage of certified nursing assistants and licensed practical nurses. However, she pointed out that communities with larger proportions of older adults also present valuable opportunities. The types of intergenerational settings emerging in some retirement destinations have communities in which people are integrated across the age spectrum. For example, some health care training programs are collocated with residential facilities for older adults, which provides opportunities for multigenerational learning and exchange. Knudson suggested shifting from a deficit-focused view of older Americans to an asset-focused view that acknowledges the contributions older populations make to the fabric of their communities.

Telehealth Services

Peterson asked about the potential interplay between the lack of diabetes patient education programs described by Probst and the increase in telecommuting work that Knudson mentioned. He queried whether the lack of broadband availability in rural areas could limit the implementation

of telehealth in those areas and perhaps feed into structural urbanism and worsen disparities. Probst replied that telehealth could be helpful for medical services that do not require a physical exam, such as follow-up appointments and psychiatric consultations, but she acknowledged that sufficient broadband capacity is still not in place. Knudson suggested that one way to categorize rural communities is by the availability of broadband services. She expects broadband to play a greater role in health care moving forward, so the assessment of broadband access could help define who has access to health care and who does not.

Rural Terminology and County Size

A virtual participant asked for clarification of the terms metro, nonmetro, rural, and urban and noted that data are often presented at the county level, but county size varies hugely across the nation. Knudson explained that there are many definitions of the term rural, with some currently used definitions going back to the 1800s when the landscape of infrastructure was very different (Mueller et al., 2020). She also noted that the broad variation in county sizes across the country—some counties in the western United States are as large as the states of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island combined—can limit apt comparisons of county-level data and assessment of infrastructure needs. Generally, counties with less than 50,000 people are categorized as rural, and counties with more than 50,000 people are categorized as urban, although some policy makers have pushed to raise the threshold for the urban designation to 500,000. Knudson suggested that population per square mile would be a better metric for assessing access to health care. Probst expressed similar concern about defining counties with less than 500,000 people as rural, because solving the problems of structural urbanism will require assessing the needs of rural communities with finer granularity. She noted that mechanisms such as the Health Professional Shortage Areas do consider multiple factors such as population, population health, and the availability of health providers,22 but even those definitions can be contentious.

Factors Affecting Access to Rural Health Care

Peterson asked whether there is a cultural or behavioral element to health care access in rural areas, noting the perception (accurate or not) that rural populations are more self-reliant and prefer to address health

___________________

22 For more information, see https://bhw.hrsa.gov/shortage-designation/hpsas (accessed August 13, 2020).

concerns on their own when possible. He asked whether such a culture might explain delayed care that leads to the development of more severe conditions. Peterson asked whether a relationship between a culture of self-reliance and a delay in accessing care has been observed anecdotally or in research, as well as whether rural culture may contribute to health disparities.

Probst explained that there is not a singular rural culture—there are multiple rural cultures across the country. Tangible factors such as “travel impedance” play a role in how promptly people can access care. Citing her own experiences growing up in a rural area, Probst drew a comparison to shopping. Her family did not go to the store frequently because of travel impedance, waiting until there was a real need for items rather than a mere desire. Similarly, as a health condition becomes more severe, the need to seek care tends to outweigh the burden of travel impedance. Cost of care is also a factor, said Probst. She contended that what some people may view as cultural individualism may actually be a response to the high cost of health care for individuals who have high deductible health insurance policies or no insurance at all. Knudson added that rural residents have historically had lower rates of health insurance coverage. She surmised that perhaps because of how closely knit some communities are, people may prefer not to owe money to anyone in their community, so the decision to forgo health care may be as much a financial preference as it is a cultural preference.