3

Rural Health Vital Signs

The second session of the workshop featured presentations on the drivers of the rural–urban gap in mortality rates, the health effects related to the extent of racial and ethnic disparities within rural communities, and public health challenges faced by Alaska Native tribal communities. Presenters also provided an overview of the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS’s) ongoing Healthy People and Rural Healthy People initiatives. The session was moderated by Alana Knudson from the Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis at NORC at the University of Chicago.

WHY IS MORTALITY HIGHER IN RURAL AMERICA?

Mark Holmes from the North Carolina Rural Health Research and Policy Analysis Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill discussed the rural–urban gap in mortality rates and explored the drivers of these geographic disparities. He also discussed the policy implications of these drivers and the initial trends of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in terms of rurality, morbidity, and mortality.

Rural–Urban Mortality Gap

Holmes described the rural–urban mortality gap, which is characterized by higher mortality rates in rural (nonmetro) areas than in urban (metro)

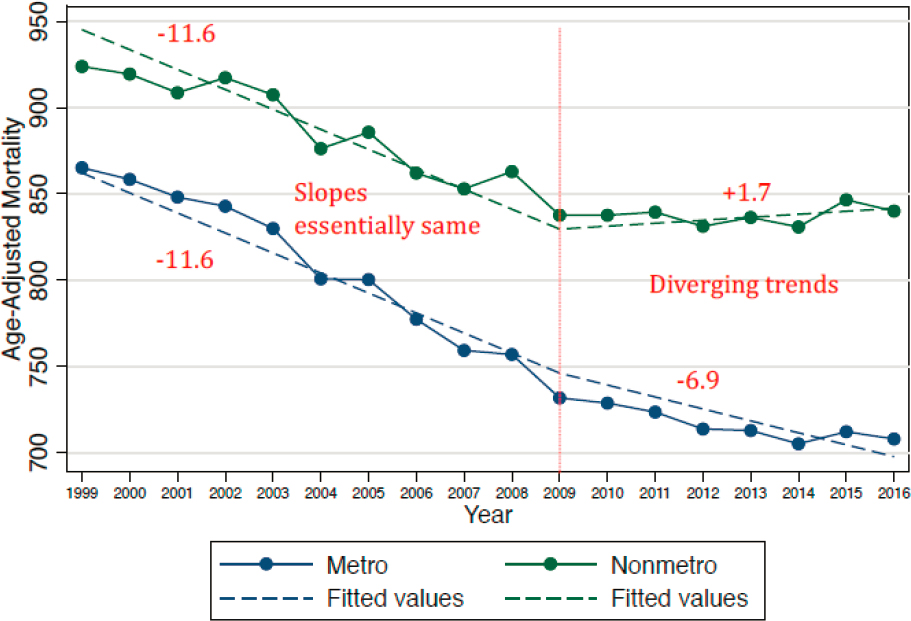

areas.1 Although this rural–urban mortality gap varies across regions, it has been increasing overall and is attributable to drivers that include access to health services, population behaviors, and the social determinants of health (SDOH). The gap in age-adjusted mortality between metro and nonmetro areas in the United States has widened over the past decade, even as overall mortality has been decreasing (see Figure 3-1). Between 1999 and 2008, the gap held steady at about 7 percent, with mortality in both metro and nonmetro populations decreasing at roughly the same rate. However, these two trends began to diverge in 2009, when mortality rates continued to decline steadily in metro areas but the rates began to increase in nonmetro areas. By 2016, the gap between metro and nonmetro areas had almost tripled to 19 percent.

Drivers of Higher Mortality in Nonmetro Areas

Holmes described how specific drivers of higher mortality may account for divergent mortality trends in metro versus nonmetro areas. An analysis of the trends in metro and nonmetro mortality data from 1980 to 2010 found that county demographics, economics, and geographic distribution in each decade explained the growing rural–urban health gap (Spencer et al., 2018). In 1980, mortality rates in metro and nonmetro areas were approximately the same. The rural–urban mortality gap began to emerge between 1980 and 1990, and the gap continued to expand between 2000 and 2010. By hypothetically adjusting rural counties to have the same population demographics as urban counties—but retaining much of the existing rural infrastructure—the researchers found that the age-adjusted mortality rate in the rural counties with urban demographics dropped to the same rate as urban counties. This demonstrates that demographics and economics are increasing predictors of the rural–urban mortality gap, he said (Spencer et al., 2018).

Behavior is another driver of the rural–urban mortality gap, said Holmes. Modifiable risk factors such as smoking, obesity, and excessive alcohol use lead to higher rates of death attributable to certain potentially preventable conditions (e.g., acute myocardial infarction, lung cancer, diabetes, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]). Holmes noted that both smoking and obesity rates tend to be higher in rural areas (19.1 and 31.5 percent, respectively) than in urban areas (15.8 and 26.7 percent, respectively), while rates of excessive alcohol use are higher in urban areas (Holmes and Thompson, 2019). This

___________________

1 Holmes explained that the designations of metro areas as urban and of nonmetro areas as rural is based on county population thresholds. Counties that are close to the upper bound of the population threshold are generally considered to be metro areas.

SOURCES: Holmes presentation, June 24, 2020; data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER (Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research) compressed mortality data (2013 Metro Status); see https://wonder.cdc.gov (accessed August 3, 2020).

disparity in modifiable risk factor rates suggests that rural areas have a greater percentage of potentially preventable deaths attributable to specific conditions than urban areas. Addressing those modifiable risk factors could potentially prevent more of those types of deaths in rural areas than in urban areas.

The lack of health care providers is another driver of higher mortality in rural areas, added Holmes. Rural areas tend to have fewer health care professionals per capita than urban areas. Specifically, a substantial disparity in the numbers of mental health care professionals exists between rural and urban areas (Larson et al., 2019; NCHWA, 2010; van Dis, 2002). Rural hospital closures are another contributing factor. Between 2010 and 2014, 171 rural hospitals closed in the United States; these closures were concentrated in the American South, a region widely affected by rural health issues.2

Variation in Causes of Death

Holmes explained that the increasing rural–urban mortality gap is being driven by certain conditions, including heart disease, unintentional injury, suicide, cirrhosis, COPD, lung cancer, and stroke (Singh and Siahpush, 2014). In his research, Holmes used U.S. Census regions and divisions to explore which causes of death are relatively more common in rural areas within each geographic region.3 For instance, comparing the mortality from diabetes in rural New England to that of urban New England can reveal the geographically standardized rural–urban mortality gap. This type of analysis demonstrates that certain causes of death are consistently overrepresented in rural areas across the United States, including motor vehicle accidents, suicide by gun (which is relatively more common in the Northeast region), other nontransport accidents (e.g., asphyxiation), and acute myocardial infarction. Holmes explained that these trends are related to factors such as the effect of mental health on suicide by firearm and the effect of lack of timely access to trauma care on accidents and acute myocardial infarction. Thus, the overrepresentation of these causes of death in rural areas can be linked to structural drivers of mortality, such as gaps in the supply of mental health professionals and increasing closures of rural hospitals.

___________________

2 More information about these rural hospital closures is available at https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures (accessed July 6, 2020).

3 The U.S. Census designates four geographic regions (West, Midwest, Northeast, and South) and nine regional divisions (Pacific, Mountain, West North Central, West South Central, East North Central, East South Central, New England, Middle Atlantic, and South Atlantic).

Regional variations in rural health suggest that a nationwide one-size-fits-all approach may not be the best approach to rural health policy, said Holmes. He recommended that policy makers consider which policies may improve rural health in regions with higher disparities. Additionally, policies should be shaped by an understanding of the underlying causes of variations, such as the quality of trauma health systems or the safety of highways. For instance, the Department of Transportation may be best suited to take action to address regional disparities in motor vehicle accidents.

COVID-19 Mortality in Rural Areas

Holmes noted that as of June 2020, COVID-19 mortality was lower in rural areas, with the exception of the American South. He presented data from The New York Times Github that compared COVID-19 cases per 100,000 across the U.S. North, Midwest, South, and West and in areas designated as metropolitan (i.e., population greater than 49,000), micropolitan (i.e., population between 10,000 and 49,000), or neither.4 Both data sets reveal similar COVID-19 trends. Metropolitan areas in the North had the highest number of cases and deaths among all areas and regions. In the West and Midwest regions, there was a gradient from highest to lowest case and death rates in areas designated as metropolitan, micropolitan, and neither, respectively. In these regions, more urbanized areas experienced higher COVID-19 rates than less urbanized areas. Particularly sharp gradients were observed in the Midwest region among metropolitan, micropolitan, and neither areas in terms of rates of both COVID-19 cases and deaths. The South is an exception to this trend, as the amount of urbanization in areas in the South was not strongly linked to rates of COVID-19 cases or deaths. Holmes added that COVID-19 trends in the South have been consistent with the expectation that cases and deaths would rise first in more urbanized areas and then spread across less urbanized and rural areas.

TRIBAL HEALTH PERSPECTIVE

Valerie Nurr’araaluk Davidson, president of Alaska Pacific University, offered a tribal health perspective framed with the tenet “nothing about us without us.” She described the Alaska Tribal Health System (ATHS) and the unique public health concerns faced by rural communities in

___________________

4 Data collected on June 22, 2020. More information about The New York Times Github is available at https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data (accessed July 7, 2020).

Alaska. She also discussed how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected rural communities in Alaska.

To provide context, Nurr’araaluk Davidson described the remote conditions in which many Indigenous people in Alaska live. The average village size in Alaska is between 300 and 350 people. Her mother’s family, for example, is from an Alaskan village called Kwigillingok, which is located within a region that is geographically similar in size to the state of Oregon and is home to 58 federally recognized tribes. All travel in this region occurs via river or airplane, as there are no roads connecting communities. In the summer, residents travel the river by boat and in the winter, they travel by driving on the frozen river. Nurr’araaluk Davidson remarked that although conversations about Alaska Natives and American Indian people sometimes focus on differences rather than commonalities, these groups share the same desires as all Americans: they wish for their children to be happy, healthy, and well educated and for their communities to be safe. However, because of the conditions in rural Alaska, Alaska Native people may need different approaches to realize those desires than people living in less remote conditions, such as leveraging the strong partnerships that have been developed by Alaska Pacific University (see Box 3-1).

Alaska Tribal Health System

Most health care in Alaska is provided through the authorization of the Indian Health Service (IHS), which serves 2.6 million American Indian and Alaska Native people across the United States through IHS direct service, urban Indian health clinics, and tribally compacted services. Nurr’araaluk Davidson provided an overview of ATHS, which is a voluntary affiliation of tribes and tribal organizers providing health services to Alaska Native and American Indian people. The ATHS is governed by the Alaska Tribal Health Compact, which is negotiated annually with the Secretary of HHS. With approximately 12,000 employees, ATHS has a presence in every Alaskan community and essentially serves as the public health system of Alaska. Each of those tribal health organizations is autonomous and serves a specific geographic area. Together, the ATHS affiliation serves a vast geographic area that extends across the state of Alaska and is comparable in size to the entire Midwest region of the continental United States. The ATHS referral system provides a four-tier health care delivery system that includes approximately 200 rural health clinics, multiple regional hospitals, and tertiary care at the two level II trauma centers in the state of Alaska, which are located in Anchorage and Providence. She added that many tribes in Alaska and across the country are moving toward tribal self-governance—rather than governance at the state or national level—in order to address the emerging needs of communities and make agile decisions to address those needs.

Tribal Public Health Challenges

Nurr’araaluk Davidson explained that the overall health status of American Indian and Alaska Native people is far worse than that of the overall U.S. population. At the national level, the life expectancy for Alaska Native and American Indian people is 5.5 years lower than that of the general population, at 73.0 years versus 78.5 years. The leading causes of death among American Indian and Alaska Native people in the United States are heart disease, malignant neoplasm, unintentional injury, and diabetes. In Alaska, the life expectancy is even lower for American Indian and Alaska Native people, at 70.7 years, and the leading causes of death for American Indian and Alaska Native people in the state are cancer, heart disease, and unintentional injury. One area of particular public health concern in Alaska is the lack of adequate sanitation facilities, she noted. Around one-quarter of rural homes in Alaska lack running water, and honey buckets are commonly used in lieu of toilets.5

___________________

5 Nurr’araaluk Davidson described the common use of honey buckets: “[A honey bucket] has nothing to do with honey. It is basically a toilet seat on top of a five-gallon bucket. That is how we use the restroom.”

A study by the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) looked at infants in Alaskan communities without access to adequate sanitation facilities (Hennessy et al., 2008). Infants in Alaskan communities without adequate sanitation facilities in the Bethel area, for example, were found to be 11 times more likely to be hospitalized for respiratory infections and 5 times more likely to be hospitalized for skin infections,6 which typically requires them to be transported by medical evacuation (medevac) transportation to the nearest hospital facility. Nurr’araaluk Davidson emphasized that hospitalization in rural Alaska is quite different from the typical process of hospitalization throughout much of the United States. Ambulances and 911 services are unavailable in rural communities, so families must call a health clinic to initiate the hospitalization process and wait for a plane to arrive. In rural Alaska, medevac and hospitalization services may cost between $50,000 and $250,000 depending on the services that are needed. She added that each year, one-third of the infants in a rural Alaskan community will require such medevac and hospitalization services—a number she deemed unacceptable.

Nurr’araaluk Davidson remarked that the public health challenges in rural Alaska have been best addressed when care has been provided close to individuals’ homes, in a culturally appropriate manner, and in languages that the rural communities understand. This has been achieved through a variety of community-based services. For instance, the Community Health Aide Program is an Alaska-specific provider type that is federally certified by IHS. Professionals in this program receive up to 2 years of training to provide a variety of services, including immunizations and prenatal exams. Without the Community Health Aide Program, Alaska would not be able to deliver timely immunizations for young children, Nurr’araaluk Davidson noted. The Community Health Aide Program was expanded into the Behavioral Health Aide Program, which focuses on mental health and substance abuse disorder treatment. The Dental Health Aide Therapist program is a mid-level dental program that provides dental services that were previously not offered and has helped children in Alaskan communities to become cavity free for the first time since contact. The federal Special Diabetes Program for Indians is also under way. Finally, she noted that improving the economic status of a community can be one of the most effective methods to improve the health of a community.

Alaska’s tribal communities have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19, said Nurr’araaluk Davidson. These disparities can be

___________________

6 Committee on Appropriations, House of Representatives, U.S. Congress. 2015. Testimony of the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. 114th Cong., 1st Sess. March 25.

attributed to the effects of systemic and institutional racism on health status, health services funding, and access to care. COVID-19 in Alaska has largely been addressed through the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, which has deployed rapid testing throughout Alaska, and by regional tribal health organizations that have taken the lead in Alaska’s COVID-19 response.

RURAL DATA CHALLENGES IN THE HEALTHY PEOPLE 2020 INITIATIVE

Sirin Yaemsiri from the U.S. Government Accountability Office provided an overview of the Healthy People 2020 initiative with a focus on objectives that track data on rurality, and described some of the challenges encountered in tracking health data in rural areas.

Overview of the Healthy People Initiative

Yaemsiri explained that the Healthy People 2020 initiative is a national agenda that communicates a vision for improving health and achieving health equity,7 as well as providing a framework for tracking the public health priorities of HHS.8 The Healthy People 2020 initiative includes 1,150 specific, measurable objectives across 42 distinct topic areas with targets to be achieved over the 2010–2020 10-year period. She noted that a data tool has been developed to accompany this initiative.9 The Healthy People 2030 initiative was released on August 18, 2020. An overarching goal of Healthy People 2020 has been to achieve health equity and eliminate disparities, including rural health disparities. For instance, one of the initiative’s objectives is to increase the proportion of persons with medical insurance. Like all of the initiative’s objectives, it has a defined baseline (i.e., 83.2 percent of persons had medical insurance in 2008), target proportion (100 percent), target-setting method (total coverage), and data sources used to track progress (the National Health Interview Survey, CDC, and the National Center for Health Statistics). The data tool provides access to tracking data for this objective. For instance, the data for health insurance coverage can be arranged nationally or by metro versus nonmetro areas

___________________

7 Healthy People provides science-based national goals and objectives with 10-year targets designed to guide national health promotion and disease prevention efforts to improve the health of all people in the United States. More information about Healthy People is available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people (accessed August 6, 2020).

8 More information about the Healthy People initiative is available at https://www.healthypeople.gov (accessed July 7, 2020).

9 More information about the Healthy People 2020 data tool is available at https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search (accessed August 3, 2020).

as defined by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). She added that the initiative’s various objectives are supported by more than 200 individual data systems, although not all of them are able to provide this level of granularity of data specific to rural areas. Of the more than 1,100 objectives in the Healthy People 2020 initiative, about one-third have rural data at the national level, but far fewer of the objectives have data from rural areas by state. Data systems that have state-level rural data include the National Vital Statistics System, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Tracking Mortality in Urban and Rural Areas

Yaemsiri described how the National Vital Statistics System is used to track mortality in urban and rural areas related to cancer, COPD, coronary heart disease, diabetes, unintentional injury, stroke, and suicide (Talih and Huang, 2016; Yaemsiri et al., 2019). Age-adjusted rates for these seven causes of death are tracked by Healthy People 2020 objectives; rural and urban data for these objectives were disaggregated using OMB’s 2013 county-based classification scheme. The age-adjusted death rates per 100,000 population in the United States between 2007 and 2017 were higher in rural areas than in urban areas for each of those seven causes of death (Yaemsiri et al., 2019). Additionally, none of the national targets for these seven causes of death had been achieved in rural populations by 2017. Among the seven mortality targets, four are getting worse in rural areas—mortality related to diabetes, COPD (45 years and older), unintentional injury, and suicide—while mortality attributable to coronary heart disease, cancer, and stroke are improving in rural areas (Yaemsiri et al., 2019). She noted that rural death rates are typically further from reaching national targets from the outset because objective targets are set based on national death rates, so rural areas have to make more progress to reach the targets. Yaemsiri suggested that these trends and the disparities in progress toward Healthy People 2020 targets between rural and urban areas is related to the notion of structural urbanism discussed by Janice Probst.

Challenges and Opportunities in Tracking Rural Health Data

Yaemsiri outlined some of the challenges encountered in efforts by the Heathy People 2020 initiative to track mortality in rural areas. Not all Healthy People data systems support estimates for rural areas at the national level, and far fewer support estimates for rural areas at the state level. Rural measures need to have at least two reliable and comparable estimates in order to measure progress toward national targets. As

previously mentioned, targets are set based on national rates, often requiring rural areas to make greater progress than urban areas in order to meet those targets. The Healthy People data tool currently does not support estimates for rural areas by region, nor does it currently support aggregation of data years to improve the reliability of data in rural areas. Finally, the data tool lacks a feature that would allow researchers to easily filter and find objectives that have rural estimates at the national or state level.

She noted that an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) chart book on rural disparities has been released (AHRQ, 2017), along with a mid-course review of the Healthy People 2020 initiative (NCHS, 2016). For the Healthy People initiative to meet its overarching goal of reducing health disparities in rural areas, it will be necessary to track and measure progress for all rural areas, Yaemsiri said. Such tracking and measurement would allow for data users to flexibly aggregate data to produce reliable estimates for rural areas and for the creation of regional estimates for rural residents where it is not possible to make state estimates or to aggregate data years. Additionally, she suggested that data systems could do the following:

- Expand sample sizes to allow state estimates of Healthy People measures for rural residents.

- Oversample rural residents to allow for the creation of state estimates of Healthy People measures for rural residents.

- Allow implementers using custom data analyses to use Healthy People as a framework and benchmark for their data analyses.

RURAL HEALTHY PEOPLE INITIATIVE: PROCESSES AND RURAL HEALTH INDICATORS

Alva Ferdinand from the Southwest Rural Health Research Center at Texas A&M University discussed the development of the Rural Healthy People initiative, presented findings from Rural Healthy People surveys and publications, and described current and future plans to further advance the initiative’s aims. Ferdinand explained that the Rural Healthy People initiative was commissioned by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy in 2002 to complement HHS’s Healthy People 2010 initiative. The aims of the Rural Healthy People initiative are to identify rural health priorities from the perspectives of various stakeholders and to consolidate those priorities with current research, practices, and models for addressing rural health priorities. She described efforts made by the initiative to date as well as plans for the future.

Rural Health Priorities Identified by the Rural Healthy People Initiative (2010 and 2020)

A major initial output of the Rural Healthy People initiative was the publication of Rural Healthy People 2010, a three-volume companion document to Healthy People 2010 (Gamm et al., 2010) that identified and ranked the top 15 rural health priorities (see Table 3-1). After the successful dissemination of Rural Healthy People 2010, a Rural Healthy People 2020 advisory board was assembled in advance of Healthy People 2020, said Ferdinand. The advisory board included representatives from funding partners, rural health care providers, state rural health agencies, and national rural health agencies. The aims were to prioritize the objectives of the Healthy People initiative in terms of the needs of rural America and to engage with those working in the field to identify models and programs that were showing promise in rural settings. The advisory board developed a national survey to achieve these aims, with the findings from this survey to be disseminated to local, state, and federal policy makers. The board works with local, state, and federal agencies and other rural stakeholders to continue developing strategies for measurement and rural population health improvement.

The survey was first fielded in December 2010 with 755 respondents and again in Spring 2012 for a total of 1,214 respondents. Most states had 10 or more respondents, while 21 states had less than 10 respondents. Many of the survey respondents were health care administrators (31.7 percent), health care providers (26.8 percent), and health care educators (14.1 percent). The Rural Healthy People 2020 survey was used to identify the top 20 rural health priorities (see Figure 3-2). Ferdinand pointed out certain changes in rural health priorities between Rural Healthy People 2010 and Rural Healthy People 2020. Access to quality health care, diabetes, and mental health and mental disorders remained among the top five priorities. From 2010 to 2020, however, substance abuse and nutrition and weight status moved up in priority ranking among the top five priorities. Ferdinand noted that Rural Healthy People 2020 was published in two volumes in 2015 (Bolin et al., 2015). The volumes were intended to address each of the rural health priorities and to identify innovative approaches that rural communities are using to meet Healthy People targets. Texas A&M University disseminated the Rural Healthy People 2020 document from its website,10 and the volumes have since been downloaded for many different purposes by a wide range of entities, including universities and colleges, hospitals, nonprofits, other health care clinics and

___________________

10 The volumes are available at https://srhrc.tamhsc.edu/rhp2020/rhp2020-v1-download.html (accessed July 9, 2020) and https://srhrc.tamhsc.edu/rhp2020/rhp2020-v2-download.html (accessed July 9, 2020).

| Rural Health Priority Objective | ||

|---|---|---|

| Rank | Rural Healthy People 2010 | Rural Healthy People 2020 |

| 1 | Access to quality health care | Access to quality health care |

| 2 | Heart disease and stroke | Nutrition and weight status |

| 3 | Diabetes | Diabetes |

| 4 | Mental health and mental disorders | Mental health and mental disorders |

| 5 | Oral health | Substance abuse |

| 6 | Tobacco use | Heart disease and stroke |

| 7 | Substance abuse | Physical activity and health |

| 8 | Education and community-based | Older adults |

| programs | ||

| 9 | Maternal, infant, and child health | Tobacco use |

| 10 | Nutrition and overweight status | Cancer |

| 11 | Public health infrastructure | Education and community-based programs |

| 12 | Immunization | Oral health |

| 13 | Injury and violence prevention | Quality of life and well-being |

| 14 | Family planning | Immunizations and infectious disease |

| 15 | Environmental health | Public health infrastructure |

| 16 | N/A | Family planning and sexual health |

| 17 | N/A | Injury and violence prevention |

| 18 | N/A | Social determinants of health |

| 19 | N/A | Health communication and health IT |

| 20 | N/A | Environmental health |

NOTE: IT = information technology.

SOURCES: Adapted from Ferdinand presentation, June 24, 2020; Bolin et al., 2015; Gamm et al., 2010.

providers, state and municipal agencies, public health offices, and federal agencies, as well as volunteer and indigent clinics.

Rural Healthy People: Past, Present, and Future

Ferdinand highlighted some of the key features of the Rural Healthy People initiative thus far and described efforts under way for Rural Healthy People 2030. Rural Healthy People 2010 and Rural Healthy People 2020 shared certain key features. Both initiatives prioritized access to

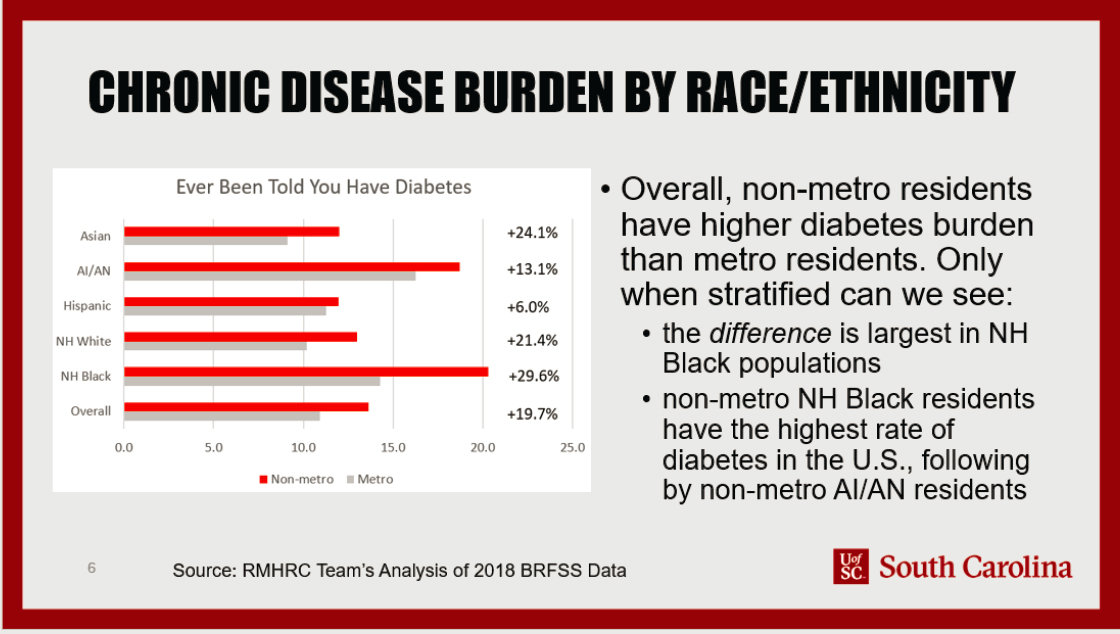

NOTE: AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; BRFSS = Behavioral and Risk Factor Surveillance System; NH = not Hispanic; RMHRC = (South Carolina) Rural and Minority Health Research Center.

SOURCE: Eberth presentation, June 24, 2020.

care as the highest-ranking rural health priority. She surmised that this is likely to remain the highest rural health priority going forward, especially as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds and continues to impact rural communities. Both iterations of Rural Healthy People reflected a great need for additional model programs and practices that have been shown to be effective in rural settings, along with the need for new targeted prevention and care models for rural areas.

Rural Healthy People 2030 will continue to seek the input and involvement of rural stakeholders, with the following aims:

- identifying objectives within priority areas for targeted attention between 2020 and 2030,

- identifying successful or promising programs developed in rural America that will help achieve those objectives,

- identifying and advocating for data sources that will help track the progress of rural America toward Healthy People targets, and

- keeping rural health disparities at the forefront of policy makers’ and advocates’ minds.

She added that the Rural Healthy People 2030 initiative has experienced delays because the Healthy People 2030 release was hindered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, the Rural Healthy People 2030 project is expected to once again help bring together researchers and practitioners to identify the rural health issues that demand the greatest attention in the coming years.

THE EFFECT OF RACIAL DISPARITIES IN RURAL AREAS

Jan Eberth from the Rural and Minority Health Research Center at the University of South Carolina considered how racial and ethnic disparities may be lost in the broader discussion of rural–urban disparities. She contextualized health equity in rural settings; discussed the intersection of race, ethnicity, and mortality in the COVID-19 pandemic; and concluded by considering the implications of racial and ethnic disparities in the rural context.

Health Inequity in the Rural Context

Noting that rural America is economically, socially, and demographically diverse, Eberth examined how the discrete differences in health across the rural–urban spectrum can mask substantial differences across racial and ethnic lines. She defined race as a socially defined classification that exposes some individuals to interpersonal and structural

disadvantages. In rural America, one in five persons is a person of color or an Indigenous person. Metro populations are more diverse, with about 42 percent racial or ethnic minorities, and most of the growth in nonmetro areas in the past two decades can be attributed to nonwhite persons. In particular, the Hispanic population is growing in rural areas by approximately 2 percent per year on average (Cromartie, 2018).

Mortality is one of the most basic measures of population health, but Eberth noted that mortality data aggregated across rural areas can mask key differences in the experiences of people living within those rural communities. Between 1999 and 2017, age-adjusted all-cause mortality rates per 100,000 remained relatively steady for nonmetro non-Hispanic white populations, declining at a rate of 0.34 percent per year on average (Probst et al., 2020).11 During the same period, American Indian, Alaska Native, and Black populations living in nonmetro areas had reductions in all-cause mortality averaging 0.52 percent per year for American Indian and Alaska Native populations, and 1.04 percent per year for nonmetro African American populations. However, although the all-cause mortality rates decreased, the absolute mortality rate remained higher than that of non-Hispanic white populations. The most prominent reductions in all-cause mortality during the period were observed among nonmetro Asian and Pacific Islander populations (2.46 percent average reduction per year) and among nonmetro Hispanic populations (1.85 percent average reduction per year). Eberth added that both groups have consistently maintained lower absolute all-cause mortality rates than their nonmetro white peers. She pointed out that since 2009, nonmetro mortality rates across all races and ethnicities have nearly leveled off and increased slightly among some groups, but most of the declines were observed in the early 2000s.

The leading causes of death in the United States are cancer, cardiovascular disease, and unintentional injury. According to CDC data, from 2013 to 2017, nonmetro residents experienced higher age-adjusted death rates than their urban peers for all three causes of death, with disparities of 13 percent in cancer mortality, 20 percent in cardiovascular disease mortality, and 37 percent in mortality caused by unintentional injury (Probst et al., 2020). Regardless of metro/nonmetro designation, Asian and Pacific Islander populations have the lowest mortality rates for all three of these causes of death, Black populations have the highest rates of mortality caused by cancer and cardiovascular disease, and American Indian and Alaska Native populations have the highest rates of mortality caused by unintentional injuries. Notably, the largest gap between

___________________

11 More information about CDC’s Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) online databases is available at https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/datarequest/D76 (accessed August 6, 2020).

metro and nonmetro populations within a single racial or ethnic group is found in American Indian and Alaska Native populations. Among this group, nonmetro residents had a rate of mortality attributable to cancer and cardiovascular disease that was 33 percent higher than that for urban residents and a rate of death attributable to unintentional injury that was 60 percent higher than that for urban residents.

Eberth presented data on infant mortality rates between 2015 and 2017 for metro and nonmetro populations stratified by race and ethnicity to demonstrate the high rates of infant mortality among both metro and nonmetro Black populations—about 11 per 1,000 persons in both metro and nonmetro populations—and to highlight the 82 percent disparity between metro and nonmetro American Indian and Alaska Native populations (5.5 and 10 per 1,000 in metro versus nonmetro populations, respectively) (Probst et al., 2019). She added that similar data showing racial and ethnic differences and childhood mortality can be found in the Health Affairs 2019 special issue on rural health.12

Eberth noted that in addition to mortality, morbidity is also a key indicator of population health that often differs by race and ethnicity in metro versus nonmetro populations. For instance, according to 2018 data on the proportions of metro and nonmetro populations who report having been diagnosed with diabetes, nonmetro populations had a greater diabetes burden than metro populations within each racial and ethnic designation.13 Stratifying these data by race shows that the metro versus nonmetro gap in diabetes diagnosis is greatest among non-Hispanic Black populations. Overall, nonmetro non-Hispanic Black populations have the highest rate of diabetes in the United States, followed by nonmetro American Indian and Alaska Native populations (see Figure 3-2).

Nonmetro populations were also more likely than metro populations to have ever been diagnosed with COPD or cancer.14 With the exception of nonmetro American Indian and Alaska Native populations, all other nonmetro racial and ethnic groups were more likely than their metro peers to have been diagnosed with COPD or cancer, she added.

___________________

12 More information about the Health Affairs 2019 special issue on rural health is available at https://www.healthaffairs.org/toc/hlthaff/38/12 (accessed July 10, 2020).

13 These data were collected from the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey and analyzed by the Rural and Minority Health Research Center at the University of South Carolina. More information about the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey is available at https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2018.html (accessed July 10, 2020).

14 More information is available at https://www.cdc.gov/copd/features/copd-urbanrural-differences.html (accessed August 6, 2020).

COVID-19, Race, and Ethnicity

Eberth discussed the intersection of mortality, race, and ethnicity in the COVID-19 pandemic. One study based on data from early 2020 through mid-April 2020 found that 52 percent of COVID-19 cases and nearly 60 percent of COVID-19 deaths occurred in counties with a disproportionately high proportion of Black residents (Millett et al., 2020). The researchers stratified COVID-19 rates by urbanicity and found that the relationship between COVID-19 diagnoses and having a high proportion of Black residents was similar across all levels of urbanicity. However, the risk of COVID-19 death that was associated with a higher proportion of Black residents was only significant in small metropolitan and noncore areas. She added that 91 percent of these disproportionately Black counties are located in the American South, which is the region where the majority of Black Americans live. The study also found that a COVID-19 diagnosis was independently associated with the percentage of uninsured residents. She noted that it will be necessary to follow up on these findings to determine whether these trends persist, worsen, or improve as the pandemic continues, particularly as the number of COVID-19 cases continues to rise throughout the American South.

Root Causes of Health Inequity in Rural Areas

Eberth explained that for traditionally underserved populations, living in a rural area can “heighten exposure to unequal social conditions that perpetuate disparities” (Caldwell et al., 2016). The root causes of health inequity in rural areas include higher rates of poverty, lower educational attainment, lower access to health care services, failing infrastructure and lower per capita investment, lack of public transportation, and segregation and racism. She noted that both compositional and contextual factors related to SDOH15 may also mediate or modify observed racial or ethnic differences in health outcomes (Lorch and Enlow, 2016). Compositional factors, such as median income in an area, reflect underlying characteristics of the people who live in those areas. Contextual factors represent area-level properties that are often modifiable and not directly linked to the characteristics of the people who live in an area. Common examples of contextual factors include zoning laws for affordable housing and state-level policies that dictate Medicaid qualification criteria.

The prevalence of certain SDOH varies by race and ethnicity among rural residents, she added (Probst et al., 2019). Rural residents who are Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native are more likely

___________________

15 The SDOH include neighborhoods and the built environment, health and health care, social and community context, education, and economic stability.

to be living in poverty, have attained less than a high school education, and are more likely to be without broadband than rural residents who are white or Asian. Rural Black and American Indian and Alaska Native populations have the greatest rates of poverty and the least access to broadband. Eberth noted that this is a critical concern in light of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has relied heavily on the implementation of online schooling and telehealth. A large proportion of rural Hispanic residents have less than a high school education. Hispanic populations were also least likely to report having any health care coverage in the 2008 CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey.16

Addressing the Compounding Effects of Rurality and Racial and Ethnic Minority Status

Eberth emphasized the compounding effects of rurality and racial and ethnic minority status on health. In rural areas, racial and ethnic minorities experience higher rates of mortality across the life span, have higher rates of chronic disease in adulthood, and are more likely to experience adverse social and economic conditions. Together, these factors can contribute to, create, and exacerbate health inequalities. Given the effects of rurality on ethnic and minority groups, Eberth asserted that interventions aimed at addressing inequality must be designed with a focus on rural populations. Most existing interventions that target inequity rely on mechanisms of behavior change and require buy-in at the individual level. However, population-level interventions that do not require high levels of individual agency—though less common than individual-level interventions—have been shown to be more effective (Frieden, 2010). She maintained that policies should be developed and enforced to ensure equitable education, housing, health care, transportation, and criminal justice that are “right sized” for rural settings. To successfully effect real improvement in rural health, she added, policies should focus on SDOH and macro-level factors across multiple sectors beyond an exclusive focus on the health care system.

DISCUSSION

Disseminating Rural Health Data to Rural Communities

Knudson started the discussion and asked how to best distribute data to rural communities so they can address their own local issues. Holmes

___________________

16 More information about the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey is available at https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2008.htm (accessed July 10, 2020).

acknowledged CDC’s progress in making its data rural friendly, especially through the development of the CDC Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research online databases and its implementation of a metro/nonmetro indicator.17 Other entities have also made efforts to disseminate and aid in the dissemination of rural health data, he added, so new approaches for increasing publications and building awareness of such efforts would be beneficial.

Nurr’araaluk Davidson commented on the need for buy-in from communities where data are being collected. She noted that in Alaska, researchers are struggling with a historical legacy of misappropriation of data collected from tribal communities. For instance, she mentioned that states or other implementers often use data from tribal communities, which frequently reveal poor health outcomes, to apply for grants that are not used to serve those communities. Good stewardship and a spirit of partnership are critical for using community data appropriately, she said. Alaska benefits from Alaskan Epicenter, a tribally operated epidemiology center at the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium that is 1 of 12 national epicenters that are either operated by tribes themselves or by IHS. She emphasized that in keeping with the adage “nothing about us without us,” tribal communities should be the primary beneficiaries of data collected from them.

Ferdinand added that researchers who collect data often make paternalistic assumptions about the people whose data they collect without engaging with them to find out how they would like their data to be used. For instance, people with chronic diseases might be more willing to allow their data to be used if the data can contribute to improvements in population health. Rather than starting with whatever data are already available, she suggested that researchers should ask populations for input about what types of data to collect and how they would be comfortable with those data being used (e.g., linking data across hospitals or other data enterprises).

Yaemsiri suggested that data systems should oversample from rural areas in order to provide better estimates of rural health. Existing data resources should also be used in more flexible ways in order to present rural health estimates at the regional level or aggregate data by year, which can be used to evaluate progress in rural areas over time. She noted that in addition to rural populations, these strategies can benefit small population groups—such as the Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, American Indian, and Alaska Native populations—for which obtaining reliable data may require aggregating over geographic areas or

___________________

17 More information about CDC WONDER online databases is available at https://wonder.cdc.gov (accessed July 9, 2020).

data years. She added that the forthcoming Healthy People 2030 initiative will include far fewer objectives than Healthy People 2020, allowing for a greater focus on smaller subpopulations within each objective. Eberth added that much of the data on SDOH come from the U.S. Census. Proposed changes for the U.S. Census include additional privacy rules and the introduction of “noise” in Census data for small areas, which could have the unintended consequence of inhibiting the quality of data collected from small populations.

The Effect of Barriers to Accessing Care in Rural Communities

A participant asked whether there are significantly higher death rates for diabetes and cancer in rural areas due to higher prevalence and complications caused by systemic lack of access to care, treatment, or follow-up. Eberth replied that people with cancer in rural areas face greater barriers to accessing specialists, like oncologists, gastroenterologists, and cancer surgeons, which may require traveling long distances from their homes. Holmes noted that along the care trajectory, small gaps of just 5 percent can have cumulative and compounding effects in terms of delays in timely diagnoses, follow-up, and treatment. Nurr’araaluk Davidson added that in tribal communities throughout the country, the shift away from their traditional diets has contributed greatly to population health challenges. They have also observed correlations between adverse childhood experiences and health status in tribal communities. She noted that the Special Diabetes Program for Indians has brought about substantial improvements because the program offers latitude for tribes and tribal health organizations to tailor diabetes programs to the needs of local populations with services such as nutrition classes, ensuring that fresh vegetables are available, and encouraging residents to harvest natural foods.

Social Determinants of Health Within the Healthy People Initiative

Given that the SDOH account for at least 40 percent of health outcomes, a participant asked why the SDOH are not a top priority within the Healthy People initiative. Yaemsiri explained that measures of the SDOH are accounted for in each objective in the Healthy People 2020 initiative in that under the national tracking data, the initiative also tracks data by race and ethnicity, education, income, geographic location by state, and other factors that help measure the SDOH. Additionally, the initiative includes an SDOH topic area with cross-cutting objectives. She suggested

that addressing the SODH more effectively will require a national shift in focus away from national rates and toward the underlying social determinants. Ferdinand commented that the Rural Healthy People initiative may have missed an opportunity to highlight the SDOH more prominently, but the effects of those determinants on health outcomes are being increasingly articulated and considered in rural health contexts. Subsequent iterations of Rural Healthy People will have the opportunity to unpack the SDOH and engage with stakeholders to determine where they fall in priority among rural health priorities, she added.

Acceleration of Telehealth in Response to COVID-19: Implications for Rural Health

Probst asked whether the transition to telehealth accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic has served as an effective mechanism for improving infrastructure for rural areas. Holmes commented that the promise of telehealth is still undermined by the lack of Internet bandwidth and broadband capacity. However, the pandemic circumstances have demonstrated that an aggressive and accelerated transition toward expanded telehealth services can be executed with relative success in terms of convenience and quality, depending on the service being delivered. Holmes suggested that in addition to expediting the process of embracing telehealth more broadly, this aggressive shift may also help to equalize the rural–urban gap in health care access, but this only applies to rural residents with high-speed Internet connectivity in the privacy of their own homes, which many do not have. In that respect, much work remains to be done to improve telehealth from both equity and operational standpoints, he added.

Nurr’araaluk Davidson remarked that the expansion of patient-centered telehealth opportunities in response to the COVID-19 pandemic was long overdue, and it has been helpful in refuting the conventional wisdom that telehealth is inefficient, ineffective, and precluded by bandwidth limitations. Telehealth through the Alaska Federal Health Care Access Network has been in use for years and has been transformative in offering rural residents access to higher-quality health care services as well as substantial savings in the high costs of travel to access health care services of any kind from many rural communities.18 To address bandwidth

___________________

18 Rural residents often must pay $1,000 to fly to the nearest health care provider, which is unsustainable for many families, given that the typical annual family income for a rural family may be as low as $20,000.

issues in rural Alaska, people can now visit many village health clinics to access telehealth services from providers that would otherwise be inaccessible. Eberth added that the COVID-19 pandemic has also brought about positive regulatory changes, with certain long-standing rules loosened to facilitate the rapid acceleration of telehealth. For instance, telephone visits, which have traditionally been disallowed, are being used to circumvent broadband issues in some communities that have better access to telephone services than Internet services. She suggested that it could be beneficial to make some of these regulatory changes more permanent going forward.

This page intentionally left blank.