Summary

The Department of Energy (DOE) and its predecessor agencies have conducted activities to develop atomic energy for civilian and defense purposes since the initiation of the World War II Manhattan Project in 1942. These activities took place both at large federal land reservations of hundreds of square miles involving industrial-scale operations and at many smaller federal and nonfederal sites, such as uranium mines and materials processing and manufacturing facilities. At its peak, this nuclear complex encompassed 134 distinct sites in 31 states and one territory, with a total area of more than 2 million acres. The nuclear weapons and energy production activities at these facilities produced large quantities of radioactive and hazardous wastes and resulted in widespread groundwater and soil contamination at these sites.

DOE initiated a concerted effort to clean up these sites beginning in the 1980s. Many of these sites have been remediated and are in long-term caretaker status, closed, or repurposed for other uses. There are currently 17 sites undergoing major cleanup and disposal activities. These activities are managed by the DOE Office of Environmental Management (EM), which, in fiscal year 2020, had budget authority of over $7 billion for cleanups and site services that are performed by contractors.

The present study is responsive to a request in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (P.L. 115-232) to conduct a review of the effectiveness and efficiency of the management of the various EM projects. Congress asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to consider the following: (1) project management practices, (2) project outcomes, and (3) the appropriateness of the level of engagement and oversight by the DOE-EM organization. The committee entered into an agreement with EM that

divided the study into two phases, with the first phase focusing on the execution of projects, the appropriateness and effectiveness of the controls and oversight applied to these projects, and the effectiveness with which these projects are realized through contracts.1

This summary provides background information on the sites currently assigned to EM undergoing cleanup; discusses current practices for management and oversight of the cleanups; offers findings and recommendations on such practices and how progress is measured against them; and considers the contracts under which the cleanups proceed and how these have been and can be structured to include incentives for improved cost and schedule performance.

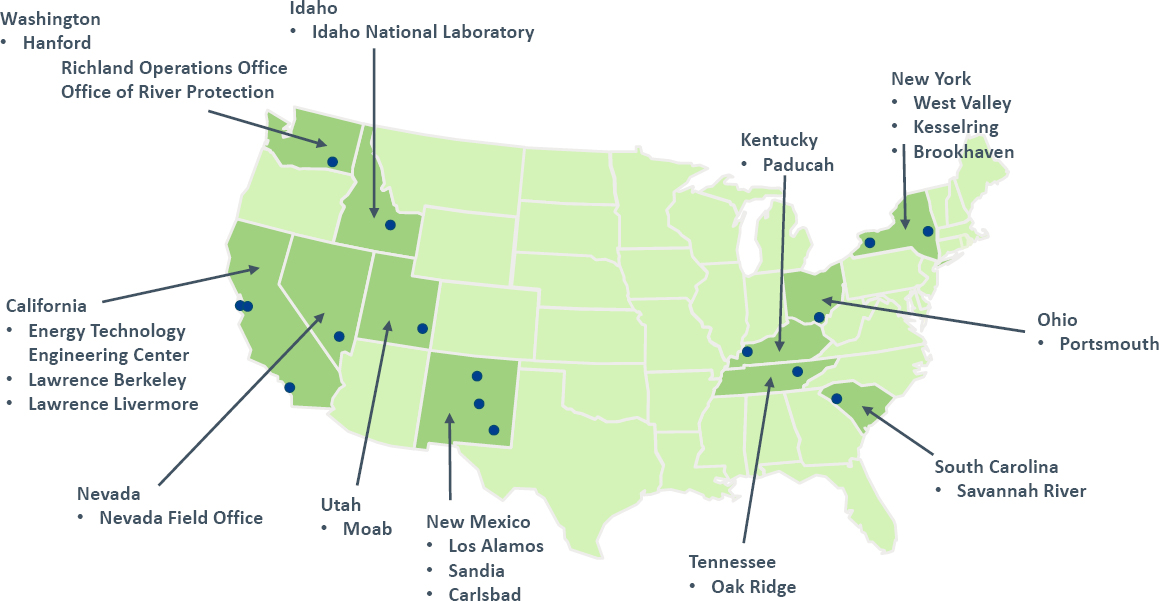

The 17 sites currently in the EM portfolio include 16 contaminated from civilian nuclear fuel cycle, naval propulsion, or nuclear weapons development activities: see Figure S.1. The 17th site, in Carlsbad, New Mexico, carries out disposal operations. Eleven of these sites are colocated with currently operating DOE facilities; the other six are inactive other than for cleanup activities.

The EM contracting model has evolved over time to meet changing requirements. Initially, management and operating (M&O) contracts prevailed, embodying a unique relationship between the government and contractor where the contractor was expected to apply its management expertise to implement the full suite of activities at a particular site within a general work scope established by the government. These were cost-type contracts with fees paid either on a fixed fee schedule or incentive basis. Later, EM used cost-type contracts that had more specific work scope and performance-based awards and fees.2 In 2000 DOE implemented two “closure contracts” at the Rocky Flats Plant in Colorado and the Fernald site in Ohio directed toward a defined end state with large monetary incentives for the contractor to achieve that end state in the most efficient and expeditious manner.

During the study, DOE explained that in the future large contracts will be implemented under a new end-state contracting model (ESCM). The end state is defined as the specified situation, including accomplishment of completion criteria, for an environmental cleanup activity at the end of the task order period of performance. This end-state concept will be implemented using single-award contracts of a certain type—indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (IDIQ)—with a 10-year draw period during which task orders with very specific work scope and 5 years’ duration may be issued as either firm fixed price or cost reimbursable. Three IDIQs have been awarded to date, two at the Hanford site and one at

___________________

1 The second phase will address how EM manages and measures progress on cleanups both at the site level and those of programs that cut across more than one site (e.g., for Portsmouth and Paducah), and how these pieces are rolled-up into an EM-wide portfolio. The second phase will also consider how the policies and directives described by EM headquarters during the work on this first report are realized in projects at the sites. It will further consider relevant issues when considering the larger suite of EM activities, such as the cleanup and disposal liabilities ascribed to EM’s (currently 17) sites.

2 Norbert Doyle, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Office of Acquisition & Project Management (EM-5.2), “Contract Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

SOURCE: Adapted from Todd Shrader, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary (EM-2), Office of Environmental Management, Department of Energy, “EM Program History and Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

the Nevada National Security Site; a fourth ESCM IDIQ procurement process is under way at the Savannah River site.

The EM project management and control systems also have evolved. Concerns regarding the effectiveness and efficiency of project management, not only within EM but also department-wide, prompted a series of studies and actions beginning in the 1990s. These include several prior studies by the National Academies; a series of investigations and reports by the Government Accountability Office (GAO); as well as internal DOE-initiated and -led reviews. These activities have led to the establishment and updating of department-wide program and project management guidelines, currently codified in DOE Order 413.3B, Program and Project Management for the Acquisition of Capital Assets: Change 5. The order sets out procedures for project development and management, with the attendant controls and oversight, including review by the Energy Systems Acquisition Advisory Board (ESAAB); a hierarchy of project approval authority based on size of project; and on-going tracking of project performance via management information systems owned by a separate Office of Project Management (PM) within DOE. EM applies Order 413.3B to certain line-item construction projects, which, as of February 2020, numbered 14 projects and with an estimated $21.6 billion total project cost (TPC) in obligations (taking into account funding across multiple years) and comprised roughly one-quarter of EM’s annual (1-year) budget authority.

The EM program has made substantial progress over the past several decades, primarily evidenced by the fact that it has reduced the footprint of contaminated sites from 134 to 17. EM also has been responsive to the various external and DOE internal management reviews by adopting a number of management improvements over time. EM, however, is currently at an inflection point, an appropriate time for further review and recalibration. Completion of cleanup activities at the remaining 17 sites will take many decades (and 11 of the EM sites are colocated with operating DOE facilities that will not be closing in the foreseeable future), and so project completions and site closures will no longer suffice as the principal program performance metric. Moreover, estimates of financial liability for cleanup of the remaining sites has outpaced the rate of expenditure for cleanup, with total cleanup liabilities currently estimated at over $400 billion, about 60 times the current annual EM budget. While EM has adopted many management reforms in recent years, challenges remain, with further opportunities to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of program performance. It is in this spirit that the committee has taken on this task.

The committee met several times to hear testimony from the principals involved in the above-described efforts, supplemented this information with written queries to EM, and deliberated on its own. During public meetings, the committee heard presentations chiefly from EM but also from other elements of the department that oversee or execute large projects. The committee made roughly 60 written queries of DOE to gather further information. The committee read and considered prior and ongoing reviews of project management at DOE including those conducted by the

department, the GAO—who also briefed the committee during the public meetings—and the National Academies.

The committee’s findings and recommendations are included below along with the context for each as given in the chapters. All the recommendations appear in this summary. The committee observes that these recommendations will have more impact if implemented in a coordinated fashion rather than piecemeal, and we urge EM to strive for that coordination.

PROJECT MANAGEMENT

The committee assessment of EM project management proceeded on two tracks: assessing the extent to which Order 413.3B represents best practice for project management and assessing how EM applied Order 413.3B to its portfolio of projects. The committee compared the requirements and procedures of Order 413.3B with other leading international protocols for project management, including the Project Management Institute best practices, the Construction Industry Institute best practices, and the UK Government Functional Standard GovS 002. The committee found that DOE Order 413.3B generally compared favorably with these other benchmarks but did identify several areas where the order could be further enhanced.

For example, DOE interprets Order 413.3B such that it “applies ONLY to construction projects, major items of equipment (MIEs) and (currently) environmental cleanup projects.”3 This interpretation appears relatively narrow compared to the Order’s stated purpose to implement “new requirements and leading practices for project and acquisition management” such as those derived from U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circulars. In particular, OMB Circular A-11 in Appendix 1 of the supplement, Capital Programming Guide states, “Capital assets include the environmental remediation of land to make it useful.” EM however, based on the narrow interpretation of Order 413.3B, does not apply the order to groundwater remediation projects that clearly have the intent of remediating land to make it useful.

In addition, Order 413.3B is only applicable to projects with estimated TPC of $50 million or higher, which excludes a number of EM activities. EM-funded projects below $50 million TPC are not currently subject to the controls and oversights noted for the larger projects. EM has addressed this issue through a memorandum4 requiring that projects below the $50 million threshold follow the principles of project management outlined in Appendix C of Order 413.3B.

___________________

3 Paul Bosco, Office of Project Management, DOE, “Project Management (PM) Governance, Systems and Training,” presentation to the committee, May 6, 2020, Washington, D.C.

4 DOE reiterates that “all projects equal to or less than $50 million shall follow the Project Management Principles as established in Appendix C of DOE Order 413.3B.” In U.S. Department of Energy. 2018. Office of Environmental Management Policy for Management of Capital Asset Projects with Total Project Cost Equal to or Less than $50 Million. EM Policy. April.

The committee, however, has not found evidence of the tracking accorded such projects. In the future, even more EM cleanup projects could be excluded under the proposed end-state contracting model where more of the work will be broken down into smaller task orders. Extending the applicability threshold down to $20 million would have the beneficial effect of: (1) applying a consistent set of principles across all such small projects; (2) invoking the controls and oversights of 413.3B such as ESAAB, (3) tracking by the Office of Project Management’s management information systems, and so forth. The small projects (between $20 million and $50 million TPC) could have a more streamlined application of Order 413.3B commensurate with their size and risk.

Order 413.3B Section 3b requires the contractor requirements document (CRD). The CRD is inserted into the Contract, and the list of requirements for the CRD are found in Attachment 1 of the Order.

Application of Order 413.3B to specific projects or project types is best carried out through effective use of the project execution plans (PEPs), as successfully demonstrated in the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), another division of DOE that makes substantially more outlays on contracting than the EM program. More generally, the committee found applying the requirements of Order 413.3B to be beneficial and that the order compared well against recognized benchmarks. The majority of activities however do not fall under the order, and such activities thus do not benefit from the full range of processes and requirements. The Demolition Protocol, for example, applies to projects in a certain category but does not include all such processes and requirements. The Demolition Protocol appears to exclude roles for the Project Management Risk Committee (PMRC) and the ESAAB, which would apply in Order 413.3B in certain instances. It also appears that certain independent reviews called for per Order 413.3B (e.g., independent project reviews [IPRs] and external independent reviews [EIRs]) have been replaced with independent field office and headquarters assessments.

In addition to the issue of the $50 million threshold, the committee also reviewed several other major instances where Order 413.3B was not applied within the EM project portfolio. As noted earlier, EM applies Order 413.3B only to large line-item construction projects, which, as of February 2020, numbered 14 projects and totaled $21.6 billion TPC in obligations (taking into account funding across multiple years) and comprised roughly one-quarter of EM’s annual (one-year) budget authority. The remaining three quarters of them include activities to which EM is not applying Order 413.3B: EM activities that are implemented outside the order include site services, demolition of buildings, and waste disposal operations, as well as environmental remediation under $50 million, noted above. The committee found that the narrow interpretation of the applicability of Order 413.3B, relative to the OMB Capital Programming Guide for capital asset projects, is a major factor contributing to this situation. EM does not appear to meet the criteria that would otherwise exempt it from Order 413.3B.

Finally, the committee reviewed the recent effort by EM to establish a new project management process for demolition projects. DOE has large numbers of buildings and facilities that are no longer in use and require demolition. Within DOE, both the NNSA and EM have “ownership” of buildings to be demolished. NNSA currently implements demolition projects under the same guidelines and procedures as apply to new construction. EM, on the other hand, believes that its demolition activities, driven as they often are by regulatory requirements, are not optimal for oversight under Order 413.3B guidelines and procedures. In July 2020, the Under Secretary (S3) approved and issued a demolition protocol “for operations-funded projects demolishing excess decontaminated facilities”;5 such activities are not subject to 413.3B. The committee review did not find a strong rationale for EM demolition projects to be managed under different procedures than NNSA demolition projects, which do follow 413.3B.

EM’s protocol for demolition projects states, “Disaggregation of site program work into smaller, discrete work activities is encouraged as it provides better project definition and clarity, is more manageable, reduces time horizons and risks, and is consistent with the project management best practices found in DOE Order 413.3B.” A multiplicity of projects transfers a greater burden for program and project management to EM; increases responsibilities with respect to interface management; creates a growing level of risk in the “white space” between individual projects (i.e., omissions); partitions risks which were demonstrated to be best aggregated on both the Rocky Flats Plant and the Fernald site; and limits the scope for innovations in project delivery and the opportunity for accruing meaningful incentives by the contractor.

___________________

5 Mark W. Menezes, Under Secretary of Energy, July 13, 2020, “Memorandum for Heads of Department Elements, SUBJECT: Demolition Projects.”

PROJECT MANAGEMENT METRICS

EM, with the help of DOE’s Office of Project Management, has developed detailed processes and methods for tracking project-level outcomes and success measures. The committee reviewed five primary performance measurement approaches used by EM, including an earned value management system (EVMS), project dashboards, project evaluation and measurement plans (PEMPs), contract performance metrics, and progress reports to Congress. After reviewing EM’s success measures and how they are used to guide decisions and report progress, the committee identified several issues for further action.

In general, an EVMS represents a principal system for an organization to monitor project management through an integrated set of work scopes, schedules, and budgets. An EVMS should provide a transparent and reliable process and approaches that explicitly, consistently, and clearly highlight the projects’ temporal status. Previous studies have advised EM to use such a system.6,7 A key element of an EVMS is a Schedule Performance Index (SPI), defined by the Project Management Body of Knowledge as a metric that is used to measure schedule efficiency. EM currently includes a measure of SPI in its EVMS system that is based on dollars expended, not time.

Because it is the key measure of schedule performance, it is important to calculate SPI based on time, not dollars, using the ratio of scheduled time of work performed (STWP) over actual time of work performed (ATWP). The difference between calculating SPI using dollars versus time can be dramatic. For example, SPI based on dollars will not flag a project as behind schedule at the completion as long as the project completes within budgeted cost of work scheduled. Hence, a calculation based on cost does not always reliably convey

___________________

6 Daniel B. Poneman, Deputy Secretary of Energy, September 9, 2011, “Secretarial Review of Environmental Management Programs and Projects.”

7 National Research Council, 2004, Progress in Improving Program Management in the Department of Energy: 2003 Assessment, Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

possible schedule delays at the project completion and can lead to wrong conclusions about how successful it was. In contrast, SPI based on time, SPI(t), will always reflect how delayed a project is regardless of the actual cost of the project.

EM’s portfolio of projects (work that is subject to following Order 413.3B) is approximately 25 percent of its annual budget. The percentage of actively tracked projects using certified EVM systems is even smaller (required for capital investment projects greater than $100 million). EM could similarly track a larger majority of activities, but does not now do so.

It should be recognized that EM project management issues are not unique; environmental cleanup for the Department of Defense (DoD) base realignment and closure (BRAC) and formerly used defense sites (FUDS) provide similar examples of the challenges faced by EM.8 Both programs use a variety of contract forms, and the procurement processes vary to fit the project need. DoD manages them as decentralized projects and are closer in size and term (5-10 years) to EM’s new ESCM). For BRAC, program management and program management oversight are typically performed internally, such as the Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command (NAVFAC) for the Department of the Navy BRAC.

___________________

8 Environmental Protection Agency, 2017, BRAC and EPA’s Federal Facility Cleanup Program: Three Decades of Excellence, Innovation and Reuse, 505-R-17-001, November, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-12/documents/brac_v9_11_2_2017_508.pdf.

The other key measure of project performance is cost management. The committee found two areas in which information on cost management was not being reported with sufficient transparency. The first issue involves the calculation of cost performance for the EM project portfolio. Performance is based on number of projects rather than aggregate cost performance of the portfolio of projects considered. In the IDIQ approach, comprised of task orders, EM would disproportionately weigh many small projects toward their overall performance. Estimates at completion based on the cost-performance index are a floor to actual final cost given that program cost performance rarely improves as the program proceeds to its completion.

A second area for improvement is the reporting of cost information in the project dashboards and project success reports. Currently, EM integrates all cost overruns into binary success metrics of Yes/No, which does not provide information on the magnitude of a cost overrun or underrun. Including the percentage of cost over- or underrun, compared to the baseline (i.e., Original Critical Decision (CD)-2 TPC) in the project success metrics would provide more clarity. Some projects have significant cost overruns (and some of which EM has still not completed have more than doubled their original estimated cost) and others have lower cost overruns (reference Project Success Spreadsheet, 2020). There are also some projects that finished exactly at the estimated cost.

CONTRACTING

The committee reviewed the rationale for the new ESCM, reviewed the advantages and disadvantages of different contract types, and then compared the previous clean-up contract models for Fernald and Rocky Flats with the ESCM in use today by EM.

EM has focused increased attention on the need to be on a trajectory toward end-states. Creating and motivating a culture of completion is important to EM’s mission success. In its own management analysis, EM has identified important ongoing efforts including “defining requirements in measurable outcomes” and “using objective performance measures focusing on outcomes to balance considerations of cost control, schedule achievement, and technical performance.” The committee concurs with the imperative of outcomes-based completion contracting and agrees with the need to build on past, successful initiatives such as Rocky Flats and Fernald completion contracts.

EM has advanced the ESCM as a new and improved vehicle for achieving outcomes-based completion contracting. The committee has carefully reviewed the ESCM model and compared it to the attributes of the completion contracts successfully deployed at the Fernald and Rocky Flats sites. The committee found that many of the features of the completion contracts that made Fernald and Rocky Flats successful are not present in the current ESCM.

In short, the committee found that the ESCM is neither outcomes based nor completion focused. Rather, the ESCM is focused on delivery of a set of discrete outputs that are not clearly mapped by contract to achievement of either a clearly defined intermediate or final end state. This significant deficiency deprives EM and the IDIQ contractor of the benefits of having a completion-oriented contract fully integrated throughout the supply chain and the fostering of innovation at the scale the program requires. Finally, the ESCM approach, as defined, focuses on narrowly defined performance criteria and increases risks associated with incomplete statements of work. These concerns and deficiencies were largely successfully addressed in Rocky Flats and Fernald.

Under the ESCM, EM awards a single IDIQ9 contract for a draw period of up to 10 years. Within the IDIQ contract umbrella, EM will establish a series of smaller, shorter-term task orders within the IDIQ umbrella, using a combination of firm fixed price and cost reimbursement task orders.10 DOE sees the benefits of this end-state concept to include: quicker evaluations of proposals; less risk of protest loss; freeing up of contractor key personnel; and less proposal cost to industry.

The committee notes that the IDIQ task order structure will create a significant number of task orders, triggering a pro rata increase in the project management burden to EM. The anticipated size of the task orders in the IDIQ cleanup contracts, averaging about $100 million, will result in EM having to manage potentially 100 task orders over the life of one cleanup contract. This process carries greater risk for EM, requiring the possible management of an unwieldy number of task orders and a significant amount of DOE oversight.

___________________

9 Norbert Doyle, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Office of Acquisition & Project Management (EM-5.2), “Contract Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

10 Ibid.

Discrete task orders also could limit benefits that might come from contractor innovation that contributed to the success at Fernald and Rocky Flats. Breaking up the scope of work into a large number of discrete tasks will diminish the focus on project outcomes and overall project optimization within an outcomes-based framework. The committee believes that the current contract procurement process can be adapted by awarding larger task orders that define one or more intermediate end states, thereby reducing residual risk to EM. Larger task orders could increase the opportunity for contractor innovation and provide for focused oversight at a higher level within EM.

DOE’s reliance on “discrete tangible progress” through individual task orders under an IDIQ contract, without identifying an overall strategy or program management plan is not, in the committee’s view, outcomes-based contracting. The ESCM concept does not define what “end states” (or reasonable subsets thereof) truly are. The committee supports true end-state or outcomes-type contracts but has not seen the requisite strong links between the management of portfolio, program, and projects that are a core element of moving toward end-state completion.

Finally, the committee notes that the ESCM single-award IDIQ contracts may not achieve the desired streamlining in the procurement process. The protest of the Hanford central plateau end-state contract, which ultimately was decided in DOE’s favor, necessitated significant and lengthy corrective actions. Contractor key personnel had to be maintained from date of award (December 2019) until notice to proceed in mid-September 2020.

CONTRACT EXECUTION: FEES AND INCENTIVES

EM seeks to obtain the maximum return from its contractors by offering a balanced mix of integrated, fair, and challenging incentives. This requires

that contractor fees be directly tied to contractor performance. In establishing appropriate incentives for contractors, fees should be reasonable, reflecting effort (noting the complexity of the work and the resources required for contract completion), cost risk (the cost responsibility and associated risk the contractor assumes under the contract type and the reliability of the cost estimates in relation to the complexity of the task), and other factors (e.g., support of federal socioeconomic programs, investment in capital, and independent development).

EM contracts typically provide a two-part fee structure consisting of a base fee and a performance fee. The performance fee generally includes both objective and subjective fee components and must relate to clearly defined performance objectives and measures. Where feasible, these objectives and measures should be expressed as desired results or outcomes.

As noted by GAO,11 there appear to be few guidelines to distinguish between “objective” and “subjective” award fee criteria. Using subjective fee components is less desirable than using objective fee components because the link between performance and reward is less clear for the former. Only when it is not feasible to use objective measures of performance should subjective fee components be used. For example, although it might be feasible, it is difficult to specify performance metrics for “environmental stewardship and compliance.” If there are well-specified subjective criteria, they should be tied to identifiable interim outcomes, discrete events, or milestones.

The committee examined subjective and objective performance assessment summaries and resulting fees as presented in “scorecards” posted on applicable DOE field office websites, particularly for contracts awarded at the Hanford site. After reviewing the evaluation of performance with Hanford cleanup contracts, DOE-EM’s rating of contractor performance does not appear to be consistent through years for a specific contract or across contracts in a specific year. Performance ratings sometimes do not appear to correspond to comments by the contract evaluator.

___________________

11 DOE “has a different process for determining incentive and award fees, depending on whether the fee is tied to objective or subjective performance criteria.” In Government Accountability Office, 2019, Department of Energy Performance Evaluations Could Better Assess Management and Operating Costs, GAO-19-5, Washington, D.C.