Proceedings of a Workshop

| IN BRIEF | |

|

December 2020 |

Resilience of the Research Enterprise During the COVID-19 Crisis

Proceedings of a Workshop Series—in Brief

The COVID-19 pandemic is having profound impacts worldwide. Immediate responses by actors across the research enterprise have instigated new and meaningful collaborations between government, universities, and companies, but have also significantly strained the resources and workforces of institutions struggling to adapt in a period of change and uncertainty. Challenges will likely persist in the long term, as shockwaves reverberate throughout the economy. Many changes could have a permanent impact on the research enterprise.

From May through August 2020, the Government-University-Industry Research Roundtable (GUIRR) hosted a virtual workshop series on the health and resilience of the research enterprise in response to COVID-19. The workshops convened senior leaders and experts to understand the challenges created by the pandemic for research and to stimulate further dialogue on opportunities for cross-sector collaboration in the United States and globally. To accommodate the rapidly changing information environment of the pandemic, the series was conducted in 6 virtual sessions: New models for open research, data, and collaboration (May 28); science communication during crisis (June 10); transitioning to hybrid virtual research, learning, and work environments (June 22); cybersecurity vulnerabilities (July 14); supply chain security (July 29); and economic impacts of the pandemic and projections for recovery (August 12). Brief summaries are grouped below under three thematic areas: coping with economic uncertainty; considering security challenges; and mobilizing resources and transforming work environments.1

COPING WITH ECONOMIC UNCERTAINTY

Economic Impacts of COVID-19

COVID-19 has affected millions of Americans’ employment, while re-exposing significant economic inequality and issues related to health disparities and the digital divide, noted Al Grasso (former CEO of MITRE Corporation and GUIRR industry co-chair). In an overview of the immediate economic impacts, Kathryn Dominguez (University of Michigan) presented on the monetary and fiscal policies to address the crisis, its potential long-term consequences, and global spillovers.

Industrial production and employment showed a precipitous decline when the U.S. economy shut down in April 2020; a mild recovery in production, although not employment, followed. Dominguez shared projections for world merchandise trade volume under optimistic, medium, and pessimistic scenarios compared to pre-pandemic trends. After a significant plunge in late March 2020, the stock market recovered its losses by the first week of June (to fall and recover again later in the summer), but most other economic indicators, including consumer confidence in the economy, have not shown the same rebound.2 As one bright spot, U.S. personal savings have risen 33 percent, the

___________________

1 For the full agendas and presentation slides from presenters from each session, see: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/resilience-of-the-research-enterprise-during-the-covid-19-crisis-a-virtual-workshop-series.

2 For more on the decoupling of stock market performance from other economic indicators, see: “The Economy Is a Mess. So Why Isn’t The

![]()

highest figure since the 1990s. But while higher savings represents future investment, it also suggests households are consuming less now. Furthermore, many households cannot save at all.

“Most economists agree the key negative shock to the economy stems from the uncertainty associated with the virus,” Dominguez said. Monetary and fiscal policies are being used to offset the shock. The Federal Reserve’s monetary policies include quantitative easing, low interest rates, increased direct lending, and international swap lines to countries facing dollar shortages. Fiscal policies include the Paycheck Protection Program and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, passed by Congress in March 2020. Negotiations for new programs have focused on stabilizing the economy rather than stimulating growth. A study of the impact of the CARES Act in Illinois found the additional funding increased consumer spending and, without it, local spending will decline.3 Yet, increased outlays and decreased receipts have impacted the federal deficit, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2020 will end with a significantly greater debt and deficit position than in 2019.

Dominguez noted that before the pandemic, the White House requested less federal funds for research and development (R&D) than in FY2018. According to CBO figures, real potential GDP growth, even without the pandemic, has flat-lined since 2000. Since the first quarter of 2020, state and local R&D investment experienced the largest drop since this data began to be reported in 1950.4 Investments in R&D contribute to higher GDP, and she expressed concern that if R&D investments at the state, local, and federal levels continue to decline, real potential GDP growth might also decline.

Dominguez also reviewed two projections for the global economic scenario from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)—neither projection positive. In one, a double dip recession is caused by a COVID-19 second wave. The second, slightly less dire scenario assumes a single shutdown but still projects the loss of five years’ worth of global income growth across the economy by 2021.5

In response to a question about the risks to the United States if China’s economy accelerates faster than the United States’, Dominguez expressed hope that if China or another country finds a vaccine first, the world would benefit, as economic recovery in other countries could benefit the United States’ economy. Another participant asked about using non-typical measures beyond GDP to measure the health of the economy. Dominguez said other measures, such as those measuring well-being, would also show negative movement. “Nothing will change until the health issues are resolved,” she stressed. “The pandemic laid bare disparities, and policy makers will need to focus on public health to improve conditions overall.”

According to William Spriggs (Howard University), most economic downturns caused by financial miscalculations are resolved through monetary policy. However, the uncertainty from COVID-19 is a different downturn that affects households and requires fiscal policies and leadership. He offered comments on the state of the labor market during the pandemic.

Spriggs said that April 2020 showed the worst job losses in U.S. history. The leisure and hospitality industry was the most significantly affected—more than 7 million jobs were lost. Retail, manufacturing, education, and health care also showed large losses.6 In April alone, more than $725 billion in payroll wages at an annualized rate were lost.

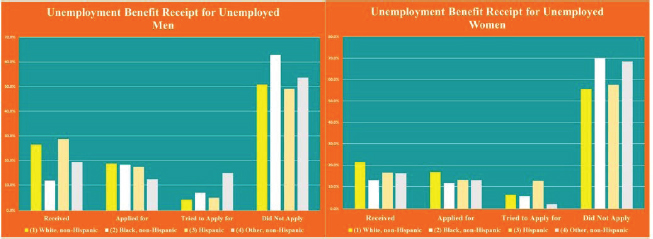

The CARES Act supplemental unemployment benefit helped mitigate the impacts of the shock, but still left large gaps. Unemployment benefits are not equally accessible to workers—many low-wage and part-time jobs are ineligible, and a disproportionate number of minorities work in the jobs that do not qualify, which deepens racial economic disparities (see Figure 1). The bottom 40 percent of workers have no net savings or liquidity, so for these workers a $1 loss in wages actually means more than a $1 loss in consumption. Spriggs said many job losses are becoming permanent. In reference to the debate around whether the additional $600 benefit provided by the CARES Act diverts people from seeking work, he refuted the assertion and noted data from Census Bureau surveys showed households—particularly of Black, Hispanic, and Asian workers—remain nervous about future job loss and seek permanent wages.

___________________

Stock Market?” FiveThirtyEight, June 19, 2020. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-economy-is-a-mess-so-why-isnt-the-stock-market.

3 Garza Casado, M. et al. 2020. The Effect of Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from COVID-19. NBER Working Paper No. 27576.

4 See: FRED Economic Data: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=tR4j.

5 OECD Economic Outlook No. 107 – June 2020 Double Hit Scenario. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EO.

6 For more information on the estimated employment impacts of COVID on students, post-doc researchers, and early-career faculty, see “Effects of COVID-19 on the Federal Research and Development Enterprise,” Congressional Research Service, April 10, 2020. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R46309.pdf.

Source: William Spriggs, Howard University. Presentation at the workshop of the Government-University-Industry Research Roundtable on “Resilience of the Research Enterprise During the COVID-19 Crisis: Economic Impacts of the Pandemic and Projections for Recovery,” held August 12, 2020.

Spriggs also commented on the impacts of COVID-19 on students and the STEM pipeline. Students of color are the majority of U.S. high schoolers, and the fact that the downturn has affected their parents’ economic situations disproportionately will be a major concern when considering whether these students will be prepared for and able to pay for college. In the virtual learning environments necessitated by COVID-19, computer and internet access is also a driver of disparities—only about 50 percent of Hispanic families have a home computer—and will affect students’ preparation for college. Within STEM fields, Spriggs noted, Black people are most likely to major in biological, social, and computer sciences. Hurting the supply of Black college students hurts that supply of future workers.

In response to a question about targeting stimulus funds, Spriggs commented the assistance seems expensive because the country has tolerated inequality for so long. He suggested that the minimum wage be increased, and noted during most of the post-war period, more equal income distribution helped make households more resilient. In the immediate term, he stressed revamping the unemployment insurance system to meet the extreme dynamics of the pandemic labor market.

Pierre Azoulay (Massachusetts Institute of Technology [MIT]) proposed innovation policy principles to beat COVID-19, stating that although there is no silver bullet to resolving the either the public health or economic crises of the pandemic, innovation is a lever.7 He described 3 core principles, which he said are not being met: (1) support many independent avenues of research; (2) draw widely on scientific and other innovation talent; and (3) demand transparency, openness, and coordination across the public and private sectors.

Related to the first principle, innovation projects are risky, and most fail. Thus, a robust portfolio is needed for some chance of success. Azoulay referenced a “back-of-the-envelope” calculation: if the government supports 10,000 projects, each with just a 0.1 percent chance of success, there is a 97 percent chance that at least five yield positive results. He called for diversity within exploration (across domains, e.g., infection control and epidemiological modeling in addition to vaccines and therapies), underlying disciplines (e.g., epidemiology, operations research, social sciences), and time horizons. The worrisome declines in R&D investment described earlier in the session by Kathryn Dominguez exhibits a trend contrary to this principle.

Regarding the second principle, the pandemic is severely disrupting access to scientific talent. Azoulay indicated that the MIT campus is empty except for construction workers, and labs are shuttered. International travel and immigration are also restricted, which Azoulay opined is the opposite of what is needed to support the science and innovation community now. He argued that lab staff be considered “essential workers” to keep the pace of science and innovation moving.

Related to the third principle, the market cannot deliver research transparency and coordination on its own. The public sector must assess which areas are under-invested. Policy makers need a dashboard to judge whether “bets” are spread widely enough. Openness also prevents duplication of effort. “There is a cost to not making failures public,” he added.

He gave a number of recommendations for meeting the three principles: improve emergency footing by public funding agencies; loosen visa policies for researchers at all career stages; and create a COVID-19 Defense Research

___________________

7 For a fuller description of the principles, see: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/368/6491/553.summary.

Committee to track, coordinate, and streamline R&D. When asked where the private and public sectors should focus R&D, Azoulay noted the abundance of private sector funding in areas that provide returns. Other domains with a pure public good, such as infection models, need government investment. Emergencies will happen again, and it is incumbent for agencies to have a mechanism for emergency funding to draw more widely on talent.

When a participant asked about digital transformation to further innovation, Azoulay noted many labs quickly transitioned to virtual operations early on in the pandemic. “Some research is amenable to this, but we are not just in a world of bits, we are also in a world of atoms,” he said. Digital tools can complement travel, equipment, and infrastructure but there may be uneven impact on the productivity of research, depending on the field. “Just as COVID-19 does not affect all people the same, it also does not affect all scientific domains uniformly.”

CONSIDERING SECURITY CHALLENGES

Science Communication and Information Disorder

Effective communication about recommendations and evidence-based policy are critical during crises, yet the pandemic has revealed gaps in communicating science in a partisan environment, noted Laurie Leshin (Worchester Polytechnic Institute and GUIRR university co-chair). Ali Nouri (Federation of American Scientists) moderated the June 10 session on this topic. He noted communication becomes more challenging during crises, when the “fog of war” sets in, which can destabilize information security.

James Druckman (Northwestern University) said a collective response should be formulated during a crisis, defined as “a collaborative effort that takes place in groups and diverges from the social norms of the situation.”8 Sources of collective responses come from (1) government, which sets and enforces laws and regulations; (2) organizations, which provide goods, collaborate, and set examples; and (3) individuals, who adhere to new norms.

Initially, many hoped COVID-19 would create a common identity that, according to a paper he co-authored, “could also foster a sense of shared fate.”9 Instead, polarization has grown, as seen through State of the Nation surveys, a collaboration between Harvard, Northeastern, Rutgers, and Northwestern.10 Concerns about family members contracting COVID-19 are higher among non-white Americans than whites. Similar differences are seen around such issues as health care, job loss, and financial hardships. Support for policies such as asking people to stay home, requiring business and schools to close, and restricting travel was generally strong across all races and ethnicities, but with slightly less support among whites in a survey conducted in early May. There were also differences by state and income.

Turning to political partisanship, Druckman said gaps between Democrats, Republicans, and independents increased across the three surveys to date (April, early May, late May) about perception of risks and adherence to guidelines. Druckman explored whether “affective polarization”—the tendency to dislike and distrust those from the other party—drove these gaps. The more people dislike the opposite party, the more they will do the opposite of what that other party suggests, he said, no matter the evidence. Bridging the divide requires changing perceptions.

Partisanship affects misinformation, he continued. Survey respondents were asked to assess the accuracy of a series of coronavirus myths spreading on the internet. The most pronounced partisan difference was in response to the statement “coronavirus was created as a weapon in a Chinese lab.” Thirty-one percent of Republications agreed with this (false) statement, compared with 13 percent of Democrats and 17 percent of independents.

Misperceptions about the effectiveness of a number of unproven coronavirus prevention measures—including the use of antibiotics and hot air hand dryers—were higher among non-white Americans than white Americans and higher among younger people (ages 18–24) than any other age group, indicating that these groups are at a disadvantage when it comes to having accurate information on preventing COVID-19.11 Druckman noted that certain groups, including the highly religious, people with exposure to Fox News, and people who frequently view President Trump’s news conferences, were more likely to accept misinformation about the virus. People reporting high social media exposure and a higher educational level were less likely to agree with misinformation statements about the virus. To resolve the impacts of partisan differences on COVID information sharing, Druckman suggested encouraging more

___________________

8 See: https://www.slideshare.net/r.T.Brannon/collective-action-and-social-change.

9 Van Bavel, J. et al. 2020. Using social and behavioral science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behavior 4, 460–471. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-020-0884-z.

10 To view the 50-State COVID-19 Survey, see: https://covidstates.org.

11 For more information see: The State of the Nation: A 50-State COVID-19 Survey, Report #4, June 2020. https://www.kateto.net/covid19/COVID19%20CONSORTIUM%20REPORT%20JUNE%202020.pdf.

crowdsourced corrections on social media; anticipating and debunking misinformation campaigns before they circulate; targeted messages to minority communities, and widespread access to mental health support.

Claire Wardle (First Draft) leads a nonprofit that helps journalists navigate the challenges of misinformation. In her experience, the recent conversation around misinformation in the United States has mostly been about political disinformation on Facebook and other social media, while in other countries, misinformation centers on science and health within closed messaging apps, like WhatsApp, Telegram, and Discord.12 Some closed-group misinformation has emerged in the United States during the pandemic, especially in diaspora communities.

According to Wardle, “Media are being manipulated by bad actors and information is being weaponized. She suggested five strategies to combat misinformation: (1) understand the full complexity of information disorder; (2) understand the power of visuals and emotion; (3) learn which communication strategies slow down misinformation; (4) train scientists, public health professionals, and communications officers; (5) react to current misinformation crises but be ready for the next one.

She noted two types of information disorder: falseness (is the information accurate?) and intent to harm (is the information created to cause harm?). In the vacuum of not knowing how the virus began and the best treatment for it, misinformation proliferated and conspiracy theories moved faster than ever from the fringes to the mainstream. Visuals and memes elicit an emotional response and cannot be dismissed, she stressed. It is an asymmetrical playing field, and science and health has to be communicated in a more visual way.

She called for longitudinal research on the impact of manipulated content and other misinformation over time, and for more research on the most effective ways to fact-check to counter misinformation. She and her colleagues published findings on labeling manipulated media with suggestions for designers.13 Wardle said training is needed for scientists, public health professionals, and communications officers to combat myths without perpetuating them. “Scientists need to become messengers in different formats, such as YouTube,” she added.

The current crisis has seen a failure to explain what is and is not yet known. First Draft published a case study in February about dengvaxia and vaccine information in the Philippines.14 It analyzes the vaccine’s badly handled roll-out, and she is concerned that mistakes will be repeated with an eventual COVID vaccine. A participant noted the public does not understand why guidance changes based on new evidence. Wardle said she wished the World Health Organization (WHO) had prefaced statements about COVID research with “this is based on what we know now.” She added this misstep has meant playing catch-up on the communications side ever since. The moderator, Ali Nouri, noted the culture of science embraces a slow, deliberate, consensus-drive pace, but scientists are less willing to publicly defend this process. Wardle said scientists need the skills to engage with the public and to explain, for example, why the process is slow—similar to the way journalists need to explain their processes.

Nouri commented that disinformation seems to move quickly through social media based on algorithms. Druckman said social media companies should flag problematic information, but crowdsourcing can also assess content. Wardle noted the platforms are designed to keep people on them, and emotional content does that. “Quality information can do well on social media, but it must be engaging,” she said. She urged institutions to invest in design and in engagement, and Nouri noted billions of federal dollars are spent on research but little goes into communicating that research to the public. Presenters’ concluding remarks emphasized the impact of the pandemic on the proliferation of polarization and misinformation, and warned of further destabilizing effects if not addressed in a collaborative way.

Cybersecurity

To open the July 14 workshop on cybersecurity vulnerabilities related to the pandemic, moderator Diana Burley (American University) noted the pandemic has enhanced risks related to cybersecurity including public concern and confusion; a dependency on the digital infrastructure; insider threats triggered by job insecurity, anger, or lack of knowledge; and different levels of awareness about threats and behavioral drivers. These risks provide bad actors with opportunities to take advantage of the COVID-19 environment. Attack vectors include phishing campaigns, ransomware attacks, malicious domains, malware and spyware, and disinformation and misinformation campaigns. New targets include COVID-19 research, the U.S. pandemic response, and supply chains. Cybercriminals adapted quickly to

___________________

12 See: “The 5 closed messaging apps every journalist should know about—and how to use them,” First Draft, November 20, 2019. https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/the-5-closed-messaging-apps-every-journalist-should-know-about-and-how-to-use-them.

13 See: https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/it-matters-how-platforms-label-manipulated-media-here-are-12-principles-designers-should-follow.

14 Mason, J., and R. Smith. First Draft case study: Exploring the controversy around Dengvaxiz and vaccine misinformation in the Philippines. https://firstdraftnews.org/long-form-article/exploring-the-controversy-around-dengvaxia-and-vaccine-misinformation-in-the-philippines-draft.

capitalize on the crisis. The Federal Bureau of Investigations reported U.S. cybercrime quadrupled during the pandemic, and Europol reported that cybercrime became the most visible criminal activity.15 Burley suggested that this changing threat landscape requires institutions across the research enterprise to consider and evolve security practices.

Brandon Wales (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency [CISA]) discussed how his agency is building resilience during COVID-19. CISA has organized its approach along three main lines. The first focus is to understand the threat landscape, which substantially differs in size, scale, and degree of dynamism than pre-pandemic. CISA has been working with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the healthcare sector to understand the changing threats at a greater degree of granularity than before the pandemic. In the past, critical cybersecurity events have targeted specific companies – including breaches of Office of Personnel Management or Equifax data – or locations, such as after a hurricane or other disaster. In the case of the pandemic, there is a wide and prolonged threat that has changed CISA’s posture.

The second focus is to provide protection within the government and private sector by scanning for vulnerabilities, providing remote-penetration testing, and offering advice. HHS experienced a denial-of-service attack in the early days of the pandemic, and CISA is committed to preventing another attack. The agency is also working with the healthcare industry—and particularly pharmaceutical R&D companies, vaccine makers, and hospitals, state health agencies—to provide support.

The third focus is to secure the ongoing digital transformation as work and education transition from in-person operation to telework. CISA considers itself a “one-stop shop,” in that they have resources in such areas as teleworking best practices, configuration of networks for collaboration, and remote learning. The agency focuses on areas of cybersecurity with many questions from stakeholders but not much existing information.

Wales said that most attacks are against known vulnerabilities for which patches exist, and that individuals and institutions often have the ability to protect themselves; basic protections complicate an adversary’s actions. In response to a question about how to make distance education more secure, he noted that CISA has a best practices guide for K–12 education which can inform conversations with administrators about how to think through security risks and create plans for responding to identified vulnerabilities. He noted people look to their peers for advice and best practices, and these communities are very important for developing resilient solutions, especially for smaller, underfunded institutions and districts. Burley also noted that adversaries often play on the non-technical ways that people interact or access with systems, so protection protocols across the research enterprise must consider and counteract non-technical, behavioral risks.

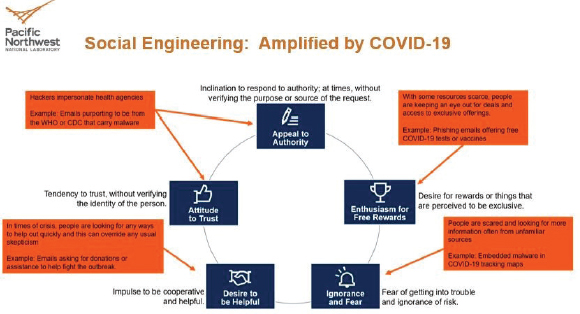

“The threat landscape was changing pre-pandemic and will continue to do so afterwards,” said Brian Abrahamson (Pacific Northwest Regional Laboratory). Previously, infrastructure and operating systems were primary targets, but information technology organizations hardened against those threats. Increasingly, people have become targets, such as through phishing and social engineering.16 Looking ahead, the Internet of Things may be the next target. Organized crime and nation states, often in partnership, have targeted the research enterprise, and these actors are becoming more sophisticated. According to Abrahamson, there has been a 67 percent increase in cyber-breaches in the last 5 years, 95 percent of them due to human error.17

Abrahamson expanded on the point that social engineering is being amplified by COVID-19 (see Figure 2). Social engineering tactics employ human interaction to obtain or compromise personal or organizational information; attackers often lie about their identity to establish credibility with victims to gather and use information to gain further access and trust. Examples include phishing emails offering COVID tests and vaccines, embedded malware in COVID-19 tracking maps, or deceptive appeals for donations. In April and May, 29,000 websites were registered related to COVID-19. Even legitimate sites can be compromised.

___________________

15 See: https://www.fbi.gov/coronavirus.

16 In the context of information security, social engineering is defined as “the use of deception to manipulate individuals into divulging confidential or personal information that may be used for fraudulent purposes.”

17 “Ninth Annual Cost of Cybercrime Study: Unlocking the Value of Improved Cybersecurity Protection,” Accenture, 2019. https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/pdf-96/accenture-2019-cost-of-cybercrime-study-final.pdf.

SOURCE: Brian Abrahamson, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Presentation at the workshop of the Government-University-Industry Research Roundtable on “Resilience of the Research Enterprise During the COVID-19 Crisis: COVID-19 and Cybersecurity,” held July 14, 2020.

Another issue is gaps in the cybersecurity workforce. Fifty percent of positions remain unfilled, and more vacancies are projected over the next few years.18 To protect their organization’s mission, he suggested research managers and leaders ask their IT teams: (1) What is the biggest risk to our remote access and do we have multiple layers of protection? (2) What is our strategy to recover if our data are locked by ransomware? (3) How are we increasing training for phishing? (4) What are we doing to help staff protect their home networks?

GUIRR co-chair Al Grasso noted the range in effectiveness of sharing threat information, pointing specifically to the Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center (ISAC)—one of 25 such centers—as a success. ISACs collect, analyze and disseminate actionable threat information to their members and provide members with tools to mitigate risks and enhance resiliency.19 The Financial Services ISAC was established as a non-profit corporation in 1999 to assure the resilience and continuity of the global financial services infrastructure through sharing threat and vulnerability information, conducting coordinated contingency planning exercises, managing rapid response communications, conducting education and training programs, and fostering collaborations with and among other key sectors and government agencies.20 Abrahamson responded shared information about vulnerabilities within a community like the financial services sector must be leveraged and used for good, and not retribution. Wales said the Financial ISAC works because organizations can put the information to actionable use, but most sectors do not have similar levels of homogeneity and security investment. Wales also noted that most companies without security resources are deep in the supply chain of larger companies, which makes the large companies vulnerable. Abrahamson added small companies can be overwhelmed with a long list of requirements; he suggested prioritizing items that will afford the most protection.

A participant noted the Center for Internet Safety has reported an increase in remote desktop attacks and asked what could be done against them, especially in sectors with more limited financial resources. Another participant noted that the agility in moving to remote working has been done on the basis of risk exceptions to accommodate the new configurations, which has piled up a lot of “technical debt.” Wales said organizations need to re-establish their baselines about what is and is not legitimate work in the new environment of remote work. Abrahamson responded that while organizations prioritized creating workarounds to enable the switch to telework, CIOs and security professionals now need to take the time to reassess the adaptations for vulnerabilities, with the help of the cybersecurity community, service management companies. Grasso concluded that COVID-19 has taught lessons about the cost of securing public health and detecting cybersecurity vulnerabilities. In both cases, convenience can trump security or safety. He urged the need for security that is convenient so people take the necessary precautions.

___________________

18 See: https://www.csis.org/analysis/cybersecurity-workforce-gap.

19 For more information on Information Sharing and Analysis Centers, see the National Council of ISACS: https://www.nationalisacs.org.

20 For a list of all the current ISACs, see: https://www.nationalisacs.org/member-isacs. For more information on the Financial Services ISAC, see: https://www.fsisac.com.

Supply Chain

Grasso moderated the July 29 session on the security and resilience of the supply chain in the face of COVID-19. Since the outset of the pandemic, the supply of pharmaceuticals, personal protective equipment (PPE), and other supplies outside the medical sector has been challenged. In the modern globalized market supply chains are complex, and patterns of collaboration have changed because of the pandemic.

Susan Helper (Case Western Reserve) focused on supply chain management challenges. The pandemic has shown the fragility of modern supply chains, and proved that national security can be affected by public health and not just military power. In the early days of the pandemic nations could not meet demand for masks, ventilators, and other needs because production is concentrated in China, and firms lacked alternatives. Even national supply chains proved inflexible, as fifty percent of manufacturing value consumed in the United States is produced abroad. Lead firms design processes with many small players with narrow capabilities and less resilience. Pressure to distribute profits to shareholders means fewer resources to weather a crisis or for R&D, she said.

“The current structure originates in global and market incentives that began in the 1990s,” Helper continued. “The collapse of U.S. manufacturing is recent, with one-third lost between 2000 and 2010.” However, she clarified that on-shoring will not totally solve vulnerabilities, nor should the United States produce everything it needs, but building resilience into the U.S. supply chain is necessary because the imbalance has become so extreme.

Current supply networks are not optimal, even for firms themselves. Most purchasing models do not consider the risks of overreliance on far-flung sources, many still make decisions based on the lowest unit price, but there are other hidden costs. Almost two-thirds (62 percent) of a manufacturer’s costs are typically in supply chain. Workers’ pay is not as monumental a cost as assumed—about 13 percent of input costs based on 2012 data. Helper suggested designing supply chains to maximize total value contribution by facilitating collaboration between managers and workers within and across firms.

Dr. Helper called for three policy principles: (1) rebuild the U.S. supply chain; (2) assure long-term stable demand for key products; and (3) promote productive investments and good jobs. Achieving these goals requires a broader conception of national security and corporate responsibility. “High-road” policies can improve performance of supply networks for consumers, firms, and workers, while helping the environment. Research to support these changes could answer questions about how firms balance the interests of multiple stakeholders, how government policies can align with incentives to assume risk, and the implications of globalization.

Anne Pritchett, (Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America [PhRMA]), discussed the pharmaceutical industry’s role in combatting COVID-19 and ensuring continuity in the supply chain. More than half of PhRMA’s members are screening compounds to identify possible treatment and vaccine candidates. Unique to COVID-19, they are ramping up manufacturing capabilities during R&D, and there is unprecedented collaboration and information-sharing across the industry.

As of July 24, almost 1,500 clinical trials were underway for vaccinations and treatments to address the virus. Vaccines are being tested at the preclinical, Phase 1 and 2, and Phase 3 stages, Pritchett suggested a minimum of 18–24 months for potential approval of a COVID-19 vaccine. Despite the unprecedented level of public-private collaborations, as a level set, only 5–10 percent of candidates are likely to succeed.

Pharmaceutical companies report substantial data, including on active pharmaceutical ingredients (API), to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other agencies, and manufacturers monitor their supply and production lines. Robust inventory management systems ensure sufficient supply, anticipate risk, and avert disruptions. FDA has been working with individual companies to anticipate surges in demand and expedite approvals for changes in the drug supply chain. The agency has also provided flexibility in the conduct of clinical trials.

Challenges have included localized surges of demand, cybersecurity threats, the impact of nationalist policies, and changes in immigration policy. The drug supply chain has been the subject of debate, but not necessarily a fact-based on—Pritchett cited concern that China could “potentially weaponize our medicines.” Fears of disruption in the drug supply chain have not come to fruition. The location of API facilities is globally diverse; out of 20,000 medicines approved for U.S. marketing, only 20 have their sole source in China, and none is deemed critical. Pritchett argued that calls for significant shifts in manufacturing to move overnight to the United States are not realistic. Construction, approvals, workforce, and other factors would take several years and billions of dollars to achieve. For these and other reasons, she expressed concern with “Buy American” proposals.

In closing, she suggested developing policies that foster increased manufacturing in the United States without disrupting the drug supply chain; supporting resiliency; and preventing other countries from perpetuating harmful

practices. The adequacy and role of the Strategic National Stockpile should be reviewed, she added, and, overall, policies must be based on fact, not rhetoric.

The question was raised about the U.S. response if China or Europe come up with the only workable vaccine. Pritchett replied that multilateral organizations including WHO and the Gates Foundation are facilitating vaccine discussions. She expressed hope that a concerted effort will build capacity to meet global needs.

Charles Avery (3M) focused on 3M’s supply chain as a leading manufacturer of N95 products. The company’s supply chains are regional, which increased speed and mitigated risk during the pandemic. COVID-19 has also created distribution changes. For example, most respiratory products are going towards health care (more than 90 percent, versus 10 percent pre-pandemic). Operations began running at maximum capacity in January. 3M has not raised prices and is fighting counterfeits through advanced authenticating systems.

3M defines an X-Factor event as a “significant circumstance, unpredictable by nature, resulting in a strong and rapid increase in demand resulting in production constraints.” According to Avery, COVID-19 is orders of magnitude greater than any other X-Factor event, and there could never have been enough installed capacity to keep up. To develop a post-crisis resiliency plan, Avery agreed with the other presenters that stockpiling is only part of the solution. 3M is working on global supply chain architecture to improve capacity within regions and countries. Other efforts include digitization to improve end-to-end visibility and disruptive technologies.

William LaPlante (MITRE Corporation) based his presentation on his work in the Department of Defense (DoD) and Congress on the Section 809 Commission, in addition to his role at MITRE.21 In national security policy circles, he said, “great power competition” encompasses economic, geopolitical, ideological, and, currently to a lesser extent, military concerns, and much of it takes place in the private sector. Supply chain concerns are tied to great power competition for a number of reasons.

DoD typically develops weapons systems, then procures and sustains them. About 70 percent of the costs are in sustainment, with potential supply chain vulnerability related to potential disruption and sole source. Referring to the earlier discussion, he noted defense prime contractors often do not have visibility several tiers down in their supply chain. However, a cottage industry has grown that uses illumination tools to provide the government with this information.22

LaPlante illustrated potential supply chain vulnerability with an example. In the 1990s, the United States began buying the first stages of Atlas 5 engines from Russia. In 2014, it became clear the country was relying on a potential adversary, yet a fix is still not in place. Although the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) was strengthened in 2018 with a widened definition of national security, it acts in a reactive manner. LaPlante noted a new rule bans the U.S. government from procuring video surveillance equipment from five Chinese companies.23 He predicts more such actions, but noted it is hard to resolve reliance on other countries—especially China—give the pressures of a global economy. COVID-19 has revealed supply chain issues more clearly, but it will not be the last such event. “The bottom line is DoD and national security have been dealing with supply chain vulnerability for a while, but COVID-19 has accelerated the exposure of new vulnerable areas such as pharmaceuticals and software. U.S. government actions must be coordinated,” he concluded.

A participant asked about the feasibility of incentivizing production of 5G–related technologies. LaPlante said if the United States mandated that design and equipment were on-shored, as happened with GPS technology, higher-value products may result. Grasso asked whether international organizations can help attain an acceptable stasis in the global environment. LaPlante noted China is active in international standards bodies, and in his view, the solution to competing with China is more U.S. engagement with international organizations. “Standards and other international bodies are more important than ever to U.S. security,” he stressed.

___________________

21 For more information on the Section 809 Panel, see: https://section809panel.org/about.

22 “Supply Chain ‘Illumination, ’ Threat Intel Top DLA List to Boost Security,” MeriTalk, October 22, 2020. https://www.meritalk.com/articles/supply-chain-illumination-threat-intel-top-dla-list-to-boost-security.

23 See: https://www.acquisition.gov/FAR-Case-2019-009/889_Part_B.

MOBILIZING RESOURCES AND TRANSFORMING WORK ENVIRONMENTS

Resources for Digital Teaching, Learning, and Work

At the June 22 workshop, Melissa Valentine (Stanford University) provided a frame to understand the myriad impacts of a shift to remote work across the research enterprise. She identified three purposes for organizations: as holding environment, collaboration space, and operating system.

“Holding” refers to the way authority figures contain and interpret uncertainty. Organizations can act as holding environments, particularly during times of confusion or difficulty, by offering a sense of reassurance, security, and mutual support.24 She suggested participants consider how their organizations and leaders can provide institutional and interpersonal holding.

Organizations are also collaboration spaces.25 The research enterprise is often a space where interpersonal interactions, problem solving, and mutual adjustments are needed. For ideas on supporting remote innovation and interaction, Valentine pointed to research by Jen Rhymer on “location-independent collaboration” within organizations that never had physical offices. The companies have different norms and expectations around communications, generally either synchronous or asynchronous. Valentine suggested participants consider if their organization would fit better with a synchronous or asynchronous knowledge-management model.

Finally, organizations function as operating systems.26 The change to remote work means more business is conducted online and thus more data are captured on platforms.27 She recommended participants develop a data science strategy to make use of newly accessible virtual work-related data.

Following Valentine’s presentation, four GUIRR members described transformations to their work environments during COVID-19:

James Green (National Aeronautics and Space Administration [NASA]) discussed how his organization transitioned to operating virtually with the help of Microsoft Teams and Google tools. NASA is looking at the situation to chart a new course by accelerating a digital transformation of paper-only records. Other changes include more virtual panels to review proposals. He also predicted more scientific conferences will continue virtually; more papers and proposals developed with the help of digital tools; less travel; and more funding of open-access publications.

Laurie Locascio (University of Maryland) noted most traditional universities will survive but changes will occur. At Maryland, negative aspects of the transition included students losing out on personal interactions, research shutting down, and lost revenue streams. On a positive note, meetings run more efficiently; “big names” can participate in conferences; proposal production increased; and creativity rules the day. Informal conversations moved to Slack to lessen e-mail traffic. Attendance at training and education activities is higher, and an intentional focus on building community has emerged.

The university funded 270 Teaching Innovation Grants, and faculty used the summer to reimagine their courses. They have procured new digital tools for teaching and research, and offer course-design support services and a Breakthrough Incubator for experimentation. They are also growing and supporting pandemic-related research; developing partnerships with the state and industry; and looking at new ways to work.

Marianne Walck (Idaho National Laboratory [INL]) noted that the Department of Energy (DOE) maintains 17 national labs across the country, with 60,000 employees in total. All labs are ramping up, depending on state and regional guidelines. National security work and flagship computing continued throughout the crisis.

INL employees are using virtual tools to meet and work, although Internet access is an issue for people in more remote areas. Experimental work restarted in July, but nonexperimental employees continue to telecommute. Walck commented on summer intern programs—INL alone hosts 400–500 students—which operated virtually, requiring significant restructuring of onboarding, computer access, and mentoring. Walck also mentioned DOE developed a collaborative research model called the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, which has been a good lesson on how to use online tools and collaborate across labs.

Looking at productivity, intellectual property (IP) production increased as measured by the number of patent applications and IP disclosures, although data are preliminary. There is indication of more publications, and it has been

___________________

24 G. Petriglieri, The psychology behind effective crisis leadership. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/04/the-psychology-behind-effective-crisis-leadership.

25 A. Edmundson, Teamwork on the fly. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2012/04/teamwork-on-the-fly-2; Teaming: How Organizations Learn, Innovate, and Compete in the Knowledge Economy.

26 J. Davis, What Will Replace the Modern Corporation?

27 Are Flash Teams the Future of Work? https://ecorner.stanford.edu/flash-teams; E. Colson, Curiosity-driven data science, Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/11/curiosity-driven-data-science.

easier to schedule meetings. But stress from child care and schooling issues has increased, and evidence indicates more burden falls on women than men. The national labs launched a Community of Practice to look at this issue. Isolation is also a factor for some.

Jeff Welser described IBM Research’s experiences. About two-thirds of IBM research is software-related. At first, many people were anxious to return to their work site, but soon welcomed the flexibility of remote work. Another one-third of IBM research requires some physical presence in the lab. After an initial hit in productivity, the company’s productivity has returned to 80 to 90 percent of previous levels. Employees have become creative about maximizing their limited lab time; for example, analysis and publishing occur off-site. Automation has increased, especially for data collection. Teams will ramp up on staggered shifts. All meetings will take place virtually, even when employees are on site.

Welser noted another impact of virtual work—interactions are and will be more intentional, and IBM is trying to figure out how to facilitate serendipitous interactions and innovation. In this regard, teams on established projects are faring better than teams in new discovery areas. Virtual conferences have been well attended. IBM’s Think Conference normally draws 25,000–35,000 people; this year, attendance tripled. But following up with fellow attendees and networking was challenging. Going forward, new projects and partnerships may emerge, such as the High Performance Computing Consortium, which was created in tandem through a partnership with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and the U.S. Department of Energy.

A participant who has run research at companies and now a small start-up commented the situation has helped with recruitment. Prospective talent seems more willing to come on board if they can work remotely. Jobs can be easier broken into pieces, he added. Walck agreed with the benefit to attract those who do not want to relocate for work, and Green said NASA is recognizing the workforce of the future will be distributed. Another participant commented technology will play a central role in collaboration of the future and represents a transformational change. As tools develop, it is important to make sure technology is accessible, especially in disadvantaged communities. All presenters noted bright spots in the transition to virtual work environments across the research enterprise, despite the accompanying multi-faceted challenges.

NEW MODELS OF OPEN RESEARCH, DATA, AND COLLABORATION

Starting in mid-March, government science advisors from countries around the world urged scientific publishers to make COVID-related articles free and widely available. Other initiatives that use artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) to analyze coronavirus data and research have been established in new cross-sectoral collaborations in the U.S. and globally, which enabled a significant increase in the mobilization and sharing of COVID-related research efforts. Ann Gabriel (Elsevier) served as moderator for the May 28 session discussing new models for open research, data, and collaboration during the pandemic. In opening, she commented breakthroughs during COVID-19 may indicate a shift in traditional forms of scholarly communication. Collaboration resulted in publishing the full genome of COVID-19 barely a month after the first patient was admitted to a Wuhan hospital, and it appeared as a Lancet open-access article. Elsevier has made content, data analytics, and tools available through the Elsevier Coronavirus Research Hub.28 When Elsevier hosted a webinar on the analytics on the research of infectious disease, more than 21,000 people registered. A huge avalanche in publications about COVID-19 is in process, with the potential to create new paradigms. Publishers are investing in preprints, although preprints are not an uncontested positive good since they are “works in progress.” Publishers are expanding their workflows to accommodate preprints without compromising peer review. The value and workflow of peer review will be under review itself, and AI and crowd-sourced methods are also being piloted. With these principles in mind, she said artificial intelligence (AI) in service to scholarly communication is an idea whose time has come.

Whether many of these rapid collaborations will last beyond the pandemic is yet to be seen. Gabriel noted that a culture of successful collaboration requires building and maintaining trust between parties sharing research data. This effort might require a number of priorities on the part of governments, universities, and industry across the enterprise, including the re-examination of incentives and reciprocity of research data sharing; inter-sectoral collaboration based on pre-defined roles and responsibilities; the creation of a preparedness and response system that fits all emerging infectious diseases with appropriate supportive technical infrastructure and pre-defined access rights and responsibilities of stakeholders; recognition of trusted international collaborating partners as external advisors and reference

___________________

28 See: https://www.elsevier.com/clinical-solutions/coronavirus-research-hub.

centers; and efforts to address barriers to sharing research data.29

Oren Etzioni (Allen Institute for AI [AI2]) described the COVID-19 Open Research Dataset (CORD-19) as an example of AI in scientific discovery. AI2 already focused on information overload created by publication of more than 3 million papers annually. Its AI-based search engine, called Semantic Scholar,30 began with 3 million papers in 2015. In 2018, they started to add datasets, research software, slides and videos, and other resources. By 2019–2020, Semantic Scholar had more than 186 million papers, 550 partnerships, and 8 million active monthly users.

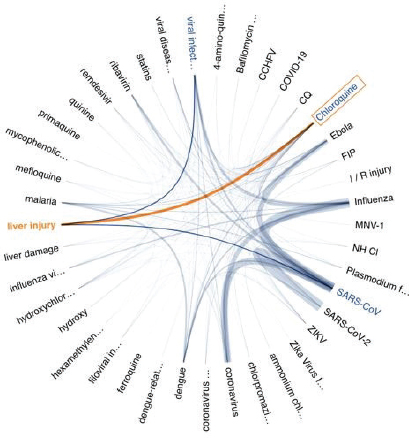

On March 6, the White House chief technology officer requested creation of a corpus of papers to create a machine-readable COVID-19 dataset.31 Just 10 days later, AI2 and many partners released CORD-19 with 24,000 papers. As of late May, CORD-19 contained 128,000 paper citations. AI software also parses and makes machine readable text and tables, and the metadata includes citation links (see Figure 3)

Source: Oren Etzioni, Allen Institute for AI. Presentation at the workshop of the Government-University-Industry Research Roundtable on “Resilience of the Research Enterprise During the COVID-19 Crisis: New Models for Open Research, Data, and Collaboration,” held May 28, 2020.

Hundreds of different AI tools are using CORD-19. Korea University has built a Question-Answering System. A more speculative project under development by AI2 and the University of Washington is a fact-checking tool. Semantic Scholar has developed an adaptive research feed, while a tool called SciSight can develop visualizations of connections between papers.

AI-based discovery engines such as Semantic Scholar have the potential to help scientists delve into more data and papers, connecting papers with datasets and software. To counter fears of AI, Etzioni quoted Microsoft Chief Scientific Officer Eric Horvitz, who said, “It’s the absence of AI technology that is already killing people.” The challenge is can we go further? Can we scale AI tools to support all scientific inquiries?

When asked about metrics of success, he replied they have shifted. First, “success” was how quickly the corpus could be assembled. Second was use; two million people have viewed it to date, a healthy sign. Third was how quickly

___________________

29 “Why open science is critical to combatting COVID-19,” OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), May 12, 2020. http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/why-open-science-is-critical-to-combatting-covid-19-cd6ab2f9.

30 See: www.semanticscholar.org.

the corpus could grow. The bottom-line metric is whether CORD-19 can generate medical discovery.

Another participant noted AI tools can help with volume and velocity, but veracity is challenging. Etzioni acknowledged speed has sometimes meant blurring preprints and peer-reviewed papers, and peer review is essential. Technology can help in two ways: fact-checking, and gathering of metrics from social media, news reports, or citations to see what other papers have said about it.

Barend Mons (Leiden University) described the Virus Outbreak Data Network (VODAN) as an implementation network of GO FAIR, a stakeholder-driven and self-governed initiative that aims to implement the FAIR data principles32 to encourage making data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR). Through community-led initiatives, GO FAIR coordinates and contributes to the development of the Internet of FAIR Data & Services and the European Open Science Cloud. According to Mons, COVID-19 provides a pressure-cooker use case for VODAN.

To take advantage of computing capacity, data have to be AI-ready. Mons explained he diverges from the work done through Semantic Scholar. In his view, data should be published in machine-readable format first and then reformatted for papers, which he called his “lifelong fight.” The basic principle of VODAN is that all data should be ready for machine-to-human (M2H), human-to-machine (H2M), and machine-to-machine (M2M) use. Data should comply with FAIR principles, be machine-actionable, as open as possible, and as distributed as possible.

He asserted he has not come across a scientific question that cannot be solved by distributed deep learning and AI. COVID-19 shows the value of distributed learning, in which data, including real-world patient observations, do not leave their sites. Patients’ CT scans, for example, stay where they are, and algorithms reach out to them.

The Disease Modeling Workflow, set up at the Dutch Tech Center for Health Sciences, could be copied anywhere, he said. Inputs include papers with CT scans from China, Iran, and Italy; WHO case reports; self-reporting; and measurements made at their institute of every patient. A disease model was developed based on understanding of the disease progressing through five phases. Called the Greatest Common Denominator Connectome, it can be used to start drug rationalization in silico. The focus, to be pragmatic, is on repurposing existing drugs. In the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe, researchers are carefully phasing a patient with biomarkers to determine which specific treatment to use at which phase. The machine has illuminated hundreds of thousands of gene connections that the virus is stimulating. This complexity could not be learned by humans reading papers (although Mons stressed the need for confirmational reading of the literature, especially if a machine finding does not seem believable).

Mons concluded by arguing that the COVID crisis shows the bankruptcy of the scientific paper as the unit of communication. He urged researchers to GO FAIR, by publishing for machines with supplementary papers for people. Mons stated 80 percent of the problems related to greater adoption of the European Open Science Cloud are social, not technical. The journal impact factor is the most inhibiting factor for open science, he opined, because people sit on data until they can publish in as prestigious a journal as possible. The second factor is the difficulty in accessing supplementary data, he added.

Etzioni agreed the current scholarly communication system is arcane, but said social changes, such as related to tenure, are a prerequisite. He said Semantic Scholar works with current reality, but applauded Mons’s vision. Ann Gabriel noted Elsevier and others invest in machine-readable formats, but user surveys show continued preference for PDFs. Mons commented it may take a new generation of scientists and less judgments based on journal impact factor. Gabriel commented that surgeons or others not concerned with impact factors also often prefer traditional PDF formats.

Another participant asked whether better algorithms could be developed to work on PDF files. Mons said that text mining and triple mining are improving but will never reach 100%--and he questioned the need to keep trying. Etzioni said deep learning and new models have been “the tide that has lifted a lot of boats.” All systems require a combination of machines and humans, and the question, now and in the future, is the appropriate division of labor.

WHAT COMES NEXT

At the conclusion of the series, GUIRR co-chair Al Grasso noted the COVID-19 crisis is not over. The emergence of the crisis sparked a new drive for innovation, collaboration, and transformation across the research enterprise, but it has also highlighted slow progress on many evergreen policy issues and exacerbated security threats in several areas. GUIRR’s October 2020 meeting, also conducted virtually, explored lessons learned by institutions in their research and administrative responses to the pandemic, and in the continued experiences and perspectives of participants from across the research enterprise in the response and adaptation to the COVID crisis.

___________________

DISCLAIMER: This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was prepared by Paula Whitacre as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the author or individual meeting participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all meeting participants; the planning committee; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

PLANNING COMMITTEE: Jeff Welser, IBM Research; Mehmood Khan, Life Biosciences; Laurie Locascio, University of Maryland; and Michele Masucci, Temple University

STAFF: Susan Sauer Sloan, Director, GUIRR; Megan Nicholson, Program Officer; Lillian Andrews, Senior Program Assistant; Clara Savage, Senior Finance Business Partner; Cyril Lee, Financial Assistant.

REVIEWERS: To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop Series—in Brief was reviewed by Michelle Birkett, Northwestern University; Rashmi Gopal-Srivastava, National Institutes of Health; and Arturo Pizano, Siemens. Marilyn Baker, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as the review coordinator.

SPONSORS: This workshop was supported by the Government-University-Industry Research Roundtable membership, National Institutes of Health, Office of Naval Research, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, and the United States Department of Agriculture.

For more information, visit http://www.nas.edu/guirr.

Suggested citation: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Resilience of the Research Enterprise During the COVID-19 Crisis: Proceedings of a Workshop–in Brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26014.

Policy and Global Affairs

Copyright 2020 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.