Session 1–Online Learning and STEM Progression

(September 22, 2020)

The rapid transition to online learning that occurred in higher education in the spring of 2020 presented many challenges. The first workshop session explored the effect on undergraduate and graduate students of institutional pivots to and continued reliance on online learning. Using panel discussions and with input from the audience, the session explored how institutions, faculty, and staff have assisted students in continuing their science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) studies; the extent to which administrators have considered student voices in decision making; and the differential effects of the transition to online learning on students from various races, ethnicities, backgrounds, and current situations. This session also explored ways to provide quality online learning experiences and considered their effects on academic progression, including the ability to complete gateway courses, to transfer from 2-year to 4-year institutions, to apply to graduate and professional schools, and to advance in graduate degree programs and careers in STEM.

EFFECTS OF HIGHER EDUCATION’S RESPONSE TO COVID-19 ON UNDERGRADUATE AND GRADUATE STUDENTS

Craig Ogilvie from Montana State University provided context for the day’s discussions by showing the results of a survey that queried graduate students at 11 universities during June and July 2020 about the stresses and support they were experiencing. His NSF RAPID award-funded team received more than 4,000 responses from students at predominantly White institutions, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Hispanic-serving institutions, major research universities, and regional comprehensive universities. “Graduate students are not doing well,” said Ogilvie in summarizing the results. A full one-third of the respondents reported being anxious or depressed, and 31 percent reported symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).1 Moreover, only one-third of the students thought institutional policy changes supported their well-being. Some 25 percent expected a delay of 6 months or longer in degree completion, and an equal number of STEM graduate students were pessimistic about pursuing their current career goals.

With funds from an NSF Rapid Response Research (RAPID) grant, Felicia Jefferson of Fort Valley State University has been investigating the adaptability and educational outcomes of rural HBCU students who had to switch to online learning as a result of the COVID-19

___________________

1 More information on PTSD and its symptoms is available at https://www.psychiatry.org/patientsfamilies/ptsd/what-is-ptsd and https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd.

pandemic.2 The long-term goal of this project, she explained, is to study the best mechanism of suddenly introducing rural, underserved, and underrepresented populations to online instruction that leads to successful academic outcomes. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Jefferson and her colleagues had found significant differences between those who choose to take classes online and those who do not.3 Most students forced by the COVID-19 pandemic to switch to online learning did not prefer that mode of instruction. Jefferson attributed this to students highly valuing regular one-on-one interactions with faculty that generally come with attending a smaller, rural HBCU.

From ongoing studies funded by an NSF RAPID award to examine the COVID-19 pandemic’s disproportionately disruptive effects on undergraduate STEM majors, Sherry Pagoto from the University of Connecticut identified three lessons:

- Success in online learning, particularly for students from low socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds and Black and Hispanic students, is affected by individual factors such as stress, the ability to focus, and social isolation; home climate and family factors (including physical space, technological limitations, and a lack of family support for and understanding of the demands of undergraduate education); and inflexibility, unresponsiveness, and lack of empathy among teaching staff.

- Course modality preferences appear to differ based on SES. Lower-SES students preferred asynchronous options and mid- to high-SES students preferred synchronous learning.

- Students from different racial and ethnic groups often prefer to engage with professors in different ways, particularly regarding the discussion of personal challenges and the student’s need for empathy from the professor. Faculty who were well prepared, responsive to feedback, and ready to conduct their classes online conveyed to students that they cared about their students’ success.

Pagoto’s possibilities for future research included the following:

- the identification of approaches that universities can use to assess the home educational climate;

- the characterization of the kinds of instructional modes that work best for different students;

- an examination of whether student preferences track with performance;

- the development and testing of instructor strategies to enhance engagement in synchronous and asynchronous online learning; and

- the development and testing of reentry programs for underrepresented students who take a gap year.

___________________

2 More information about this study was presented by Rachel A. Smith at the fourth session on October 6, 2020.

3 Paul, J., and Jefferson, F. (2019). A comparative analysis of student performance in an online vs. face-to-face environmental science course from 2009 to 2016. Frontiers in Computer Science 1:7. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomp.2019.00007/full.

Community colleges may provide some best practices for online learning, given that their students take more online courses compared to students in 4-year institutions or graduate schools.4 Cassandra Hart from the University of California, Davis, studies California’s community colleges and the community college system’s struggles to meet student technology needs. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, some community college students are accessing online courses through cell phones, Hart said. Others deal with limited connectivity at home or have to compete for bandwidth with siblings who are also taking classes online. In one effort to compensate, many community colleges have made Wi-Fi available in their parking lots so student can access the Internet from their cars. She noted that synchronous courses may present difficulties for community college students who often have other obligations such as work or childcare. Some community colleges are consequently working to provide faculty with tools to shift their courses to asynchronous online formats.

Viji Sathy from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill asked the panel about long-term effects of the pandemic. Ogilvie said that he worries about the effects on students of the cumulative, ongoing stress they are experiencing today, while Hart is concerned that the COVID-19 pandemic will negatively affect retention of students of color and those from low socioeconomic status in the STEM pipeline. At the same time, the expansion of online courses could provide an opportunity in the next 5 years to increase access to higher education for students from groups currently underrepresented in STEM. Sathy called out the importance of being open to having discussions with students and being transparent in our pedagogical choices. She believes that communicating care is very important, as is fostering a sense of belonging and community in our students.

STUDENT-CENTERED ONLINE LEARNING

Cynthia Brame from Vanderbilt University discussed highlights from an online course design institute she and her colleagues ran in the summer of 2020 for some 500 faculty members (about 40% of Vanderbilt’s faculty). This 40-hour course was structured on a cohort model, each led by a Center for Teaching staff member, that allowed the groups to develop learning communities and help them adapt what they were learning to their particular setting. Brame’s team used the “community of inquiry” model to organize the course.5 This approach helped faculty ask themselves the right questions about their design choices and facilitation decisions such as how they could help their students engage individually and as a group. A key course feature is that it stressed universal design as a learning model, which helped faculty process ideas through an equity-focused lens when making course design decisions.

In making the transition to online learning, Viveka Brown from Spelman College focused her efforts on building a positive online classroom culture, one that humanizes the experience and in which students took ownership of the virtual class. Brown said she works to build a positive culture and bring a “growth mindset” to her classes. She reported discussing with her

___________________

4 Gierdowski, D.C. (2019). ECAR Study of Community College Students and Information Technology, 2019. Louisville, CO: Education Center for Analysis and Research https://library.educause.edu//media/files/library/2019/5/2018commcollss.pdf?la=en&hash=3D6C0CC022FD4B69E7F4B10FEBD4AD0FB52347A0.

5 Garrison, D., Anderson, T., and Archer, W. (2010). The first decade of the Community of Inquiry Framework: A retrospective. The Internet and Higher Education 13(1–2):5–9. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1096751609000608.

students the value of making mistakes in a positive, supportive environment. To ensure that she is accessible to students and sensitive to nonverbal cues from the students, she holds a weekly icebreaker outside of class that helps create this collaborative, supportive environment. Brown also develops weekly checklists so that students can set short-term learning goals and measure their accomplishments, allowing her to provide regular feedback.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic students were struggling with mental health issues, said Mays Imad from Pima Community College, and the COVID-19 pandemic amplified those struggles. This, she said, makes a good case for taking a trauma-informed approach to education6 for the purpose of creating equitable learning opportunities. Caring about student learning in this context requires being aware of and sensitive to trauma in order to support the entire university community. Imad noted the importance of telling students that trauma-related difficulties have a biological basis, which helps students to be more empathetic about their own experiences.7

Maxwell Bigman studied how faculty and teaching assistants in the computer science department at Stanford University were transitioning to online instruction and found that, although many had experience with online teaching, they still found themselves needing to experiment with ways of delivering course content effectively. He also found that the most effective instructors were those who showed empathy toward their students, used short surveys to discern how their students were doing and also to gather feedback, and combined synchronous and asynchronous instruction.8 Effective instructors were flexible in their work demands. One challenge he identified was not only determining appropriate content for online learning, but also generating alternatives to compensate for the loss of in-person course experiences and student-to-student interactions. Another challenge was helping instructors address concerns about equity and access, inequalities that become exacerbated when students leave campus. He also noted the importance of taking an iterative, human-centered approach to online course design9 that explicitly collects and uses feedback from students.

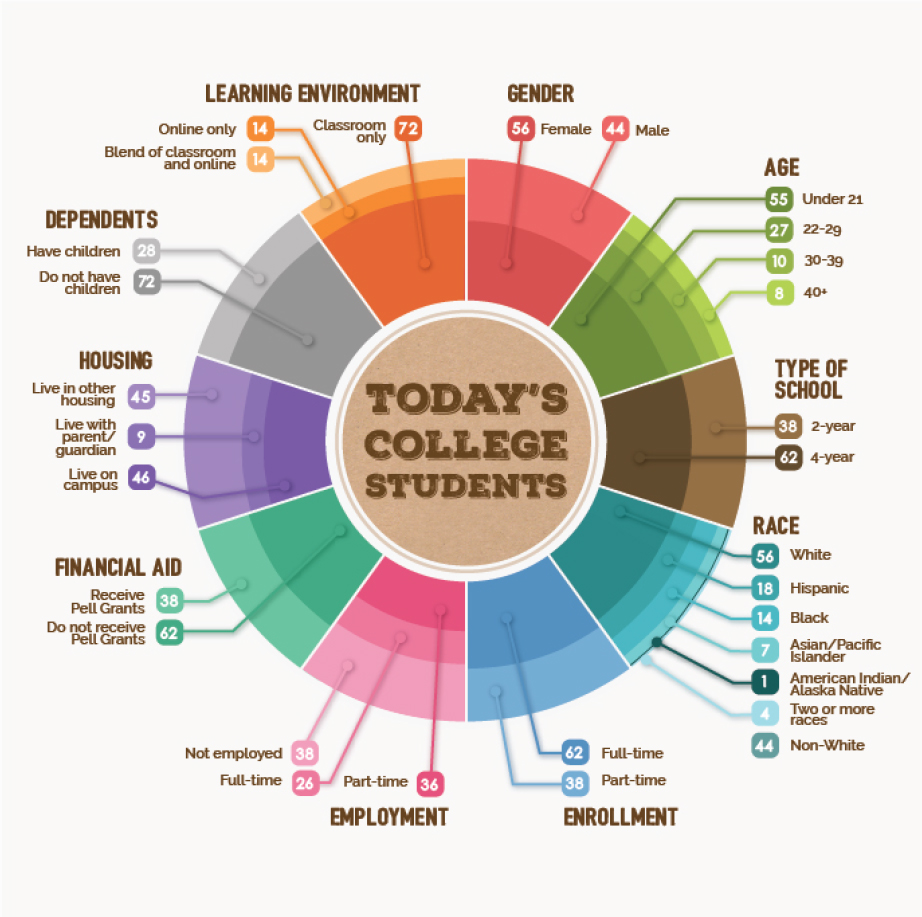

Tam’ra-Kay Francis from the University of Washington noted that students enter the higher education world from a wide range of backgrounds (see Figure 1-1), which raises questions about how to provide supportive environments for all students during the COVID-19 pandemic; how the STEM community has been enacting and advancing equity-minded policies, practices, and mindsets; and what an equity-minded indicator of success would look like. To answer those questions, her institution established the Pedagogy and Research on Race, Identity, Social Justice, and Meaning (PR2ISM) initiative to convene faculty, staff, postdoctoral researchers, and students to work together in teams. The goal is to identify and undertake actions that improve equity, emphasize mental health, and empower people to implement actionable strategies to reduce and eliminate exclusionary practices in teaching and research.10 PR2ISM

___________________

6 Lindloff, M. (2019). Utilizing a trauma informed approach to build resiliency in underrepresented college students. Counselor Education Capstones 124. https://openriver.winona.edu/counseloreducationcapstones/124.

7 Imad, M. (2020). Leverage the neuroscience of now. Inside Higher Education. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2020/06/03/seven-recommendations-helping-students-thrive-times-trauma.

8 Bigman, M., and Mitchell J.C. (2020). Teaching online in 2020: Experiments, empathy, discovery. In 2020 IEEE Learning With MOOCS (LWMOOCS) (pp. 156-161) Antigua Guatemala. https://doi.org/10.1109/LWMOOCS50143.2020.923431.

9 Karakaya, K. (2020). Design considerations in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: A human-centered approach. Educational Technology Research and Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09884-0.

10 Additional information is available at http://www.pr2ism.org.

convened all of the University of Washington’s STEM units, colleges, and institutes, as well as multiple student organizations, including those representing Black, Indigenous, and People of Color and the Postdoc Diversity Alliance, in interactive workshops to create team-based learning and action, explained Francis. These interactive workshops also identified current areas on campus where this work was already happening.

SOURCE; Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, 2021 (2015 version included on a slide presented by speaker Tam’ra-Kay Francis).

SUPPORTING STUDENT PROGRESS IN STEM LEARNING

While the previous panels discussed efforts to support student success in online courses, this session’s third panel turned its attention to initiatives aimed at ensuring that students can progress through the transitions necessary for their journeys toward STEM degrees despite the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, the national reckoning with structural racism, and natural disasters such as hurricanes and wildfires. Erin Shortlidge from Portland State University reiterated that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the psychological and financial strains

and home-related barriers that students face, she explained that this creates challenges for faculty who need to figure out how to integrate that observation into the STEM educational environment. Her ongoing NSF-funded research—Reducing Transfer Shock: Developing Community, and Collaboration to Support Urban STEM Transfer Students11—has shown that intervention programs that help STEM students transition from community college to a 4-year program also help them develop a higher sense of belonging, which can contribute to increased STEM progression. The problem is that such programs only support about 10 percent of her institution’s STEM students.

Nayda Santiago from the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez, said that her research found that 74 percent of STEM students affected by Hurricane Maria in September 2017 and the earthquake swarms that struck the island starting in late December 2019 needed emotional support, with 25 percent exhibiting anxiety and depressive disorders. Another study found that 86 percent of engineering students were unable to contact their professors at some point during the semester, her institution has since increased the amount of mentoring the students receive from faculty and peers. A third project surveyed some 900 students at 60 institutions and found high levels of stress, anxiety, loneliness, and financial worries among the students, with 8 percent reporting they had lost their jobs. Students also reported losing internships and other experiences and were considering abandoning their studies, and 12 percent even reported that they would not be able to graduate as planned. Santiago said that for this group of students, providing summer experiences proved to be an important way of keeping them engaged.

Eboni Zamani-Gallaher from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign works to address the challenge of math remediation at the community college level by attempting to make math a gateway rather than a gatekeeper for underrepresented minority students. One study she directs, the Hispanic-Serving Community Colleges (HSCCs) STEM Pipelines, is exploring the transitions to and through Hispanic-serving 2-year institutions by underrepresented minoritized STEM students in eight U.S. states and Puerto Rico. Of the STEM degrees earned by Latinx students, the vast majority were conferred by HSCCs. She noted that she has seen in her work that more intentional strategies and practices are needed to facilitate the collaboration of academic and student affairs offices with student services offices in order to support the academic mission of these institutions and move students forward in their pursuit of STEM degrees.

Keivan Stassun from Vanderbilt University discussed his institution’s actions to help neurodiverse students cope with the COVID-19 pandemic’s challenges. Actions included having a job coach conduct regular one-on-one virtual check-ins with neurodiverse interns and supporting them with executive function tasks such as offering advice on how to handle workloads and how to ask for help. The interns, who normally work alone with little social interaction, mentioned that they missed being with their cohort, so Stassun opened a standing, all-day Zoom session that allowed the interns to feel they were still working side-by-side with their cohort. Both Stassun and Shortlidge noted the need for research to determine whether these programs are effective at supporting STEM student progress toward degree completion in general, particularly for students from underrepresented and neurodiverse populations.

Summarizing the day’s discussions, Inniss said that the resounding sentiment of almost all the panelists was that it is important to acknowledge the emotional and mental toll the COVID-19 pandemic has been exacting on students. For this reason, faculty and staff should pay

___________________

11 Additional information about this project is available at https://nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1742542&HistoricalAwards=false.

attention to the importance of demonstrating compassion and acknowledging student experiences and needs. Jim Julius commented that “if you are responsible for this work and you feel like it is all on your shoulders to do the work, you are missing an opportunity, I think, because you do have colleagues that are out there that would love to connect. Find ways to engage those folks, find ways to reward them, and recognize their time.”