2

MOVING TOWARD BETTER DEMENTIA CARE, SERVICES, AND SUPPORTS

Much progress has been made relative to how dementia care used to be provided. However, persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers are still struggling and are not living as well as they might. There are places where persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers are receiving and delivering high-quality care, supports, and services. But many individuals do not have access to such care, and, especially in disadvantaged communities, disparities are manifest in the care available and received.

The charge to this committee was to examine the evidence available to support decisions about policy and the broad dissemination and implementation of specific interventions, and to inform the relative prioritization of interventions that could be helpful but require resources, which are limited. To set the stage for the committee’s response to that charge, this chapter explores fundamental concepts and principles that inform high-quality dementia care, services, and supports and takes stock of the journey toward providing better dementia care. The chapter ends with a set of guiding principles and core components that point to a better way to support persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers so they can thrive and live well.

LIVING WELL WITH DEMENTIA

The Experience of Persons Living with Dementia

Recent estimates place the number of people living with dementia in the United States somewhere between 3.7 and 5.8 million (Alzheimer’s Asso

ciation, 2020a; Nichols et al., 2019); globally, 37.8 to 51.0 million people are estimated to be living with dementia (Nichols et al., 2019). Dementia is a result of at least one disease—the most common being such neurodegenerative diseases as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular disease, or Lewy body disease—that cause neurons to degenerate. In the past three decades, the United States, along with other wealthy countries, has experienced a steady decline in the risk of developing dementia (Livingston et al., 2020). This risk reduction has not been uniformly experienced, however, but instead relies on lifetime access to health care, particularly for cardiovascular disease; socioeconomic stability; and education (Livingston et al., 2020; Satizabal et al., 2016).

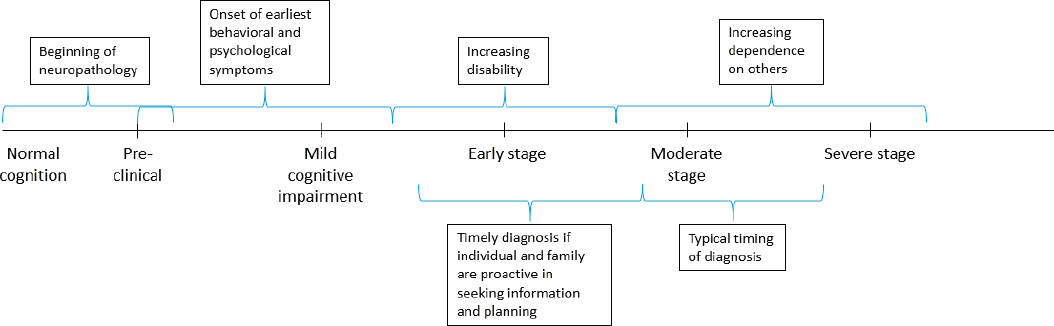

The symptoms of dementia can be categorized broadly as cognitive, functional, and behavioral, and may progressively worsen at different rates that are influenced by such factors as age of onset, sex, education, and history of hypertension (Haaksma et al., 2018; Tschanz et al., 2011). Improvement in the ability to detect and diagnose dementia earlier in its course led to the emergence of the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a condition characterized by cognitive decline predominantly though not only in memory, but with normal functioning (Petersen et al., 2009). Common early symptoms of dementia include changes in memory; difficulties with attention, problem solving, and organization; and the emergence of anxiety (Gitlin and Hodgson, 2018). As the disease progresses, the person living with dementia may experience such symptoms as restlessness, anxiety, agitation, irritability, and aggressiveness. Along with these symptoms, the abilities of the person living with dementia to live independently and carry out activities of daily living decline. As a result, he or she relies more heavily on care partners or caregivers (Gitlin and Hodgson, 2018; NRC, 2010). In the late stage of dementia, the individual loses much of their ability to communicate verbally and needs a caregiver to meet daily needs (Gitlin and Hodgson, 2018) (see Figure 2-1). The average life expectancy after diagnosis for a person living with dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease is around 4–6 years (Tom et al., 2015), though the average time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis is about 3 years (Thoits et al., 2018).

Reckoning with the early signs and symptoms of dementia can be a source of fear and distress for persons living with dementia, especially as they consider the implications for their independence (Gitlin and Hodgson, 2018). Moreover, the uncertainty of how the disease will affect them can lead to feelings of isolation, embarrassment, frustration, and confusion for persons living with dementia, as well as their family members and loved ones. Importantly, there is no singular experience of living with dementia. In fact, how individuals experience their own life with dementia is influenced by moderators of oppression and privilege, including race, ethnicity, gender expression, and class (Hulko, 2009). Individuals who face more

SOURCE: Adapted from Gitlin and Hodgson, 2018.

marginalization based on these characteristics tend to view the memory deficits of dementia as less problematic, instead prioritizing the ability to carry out activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living as the measure of living well. Individuals with more privilege tend to have more social and emotional concerns, such as maintaining social roles, relationships, and independence, and generally have a more negative appraisal of their experience of living with dementia. Sexual and gender identity also intersect with the moderators mentioned above, such that LGBTQ individuals living with dementia are at increased risk of experiencing social isolation and poverty, especially if they belong to other marginalized groups (Alzheimer’s Association and SAGE, 2018).

In the face of these challenges, however, action can be taken, such as adopting person-centered and strengths-based perspectives (both of which are discussed later in this chapter), to mitigate the fear and potential for loss of independence, identity, purpose, and relationships (Dementia Action Alliance and The Eden Alternative, 2020). Persons living with dementia are capable of leading meaningful and rewarding lives, finding enjoyment and pleasure from engaging in activities of interest, maintaining social relationships with others, and being connected to familiar environments and communities (Han et al., 2016). Social engagement, a quality relationship with a care partner or caregiver, and spirituality are factors that may further support a better quality of life for persons living with dementia (Martyr et al., 2018).

To live well, persons living with dementia need physical quality of life, social and emotional quality of life, and access to medical care and long-term services and supports (Black et al., 2013; Jennings et al., 2017). Medical care for persons living with dementia includes care specific to dementia, such as diagnosis, medications, and health education. It also includes care for other, comorbid conditions. Persons living with dementia frequently also live with one or more comorbid conditions, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, physical disabilities (e.g., limb loss, arthritis, sensory impairments), behavioral and psychiatric disorders (e.g., traumatic brain injuries, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], bipolar disorder), and intellectual and developmental disabilities (e.g., Down syndrome, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], autism spectrum disorder). These conditions may affect the type and amount of care, services, and supports needed, as well as complicate both dementia care and care for other conditions.

Notably, however, much of what persons living with dementia need is support for functioning independently for as long as possible, living well in the world, and being able to participate in valued activities. In fact, some persons living with dementia prefer to remain living independently, especially in the early stages, and 13 percent live alone (Gould et al., 2015).

Long-term services and supports (LTSS) are provided to help people function as independently as possible for as long as possible in their own homes or in residential care settings (Thach and Wiener, 2018). LTSS may be delivered by care partners and caregivers (often family members and friends) or through formal care systems in the home and in formal residential settings, such as assisted living facilities and nursing homes. Persons living with dementia also need other services and supports, such as transportation and service coordination. As noted above, however, many persons living with dementia do not have access to or receive the care, supports, and services that would enable them to thrive. For example, one study found that 99 percent of persons living with dementia had at least one unmet need, with the average number of unmet needs being 7.7 (Black et al., 2013). In another large sample, every person living with dementia reported at least one unmet need, and the average number of unmet needs was 10.6 (Black et al., 2019). Ninety-seven percent of persons living with dementia reported unmet needs related to safety, including emergency planning; fall risk management; potential for abuse, neglect, and exploitation; and help with medication use and adherence. Eighty-three percent reported general health care needs not being met, including dental care, medical specialist care, incontinence care, and nutrition. Seventy-three percent reported unmet needs related to daily activities, including lack of meaningful activities, physical inactivity, and social isolation. Individuals who were racial and ethnic minorities, had lower educational attainment, had lower incomes, lived alone, and had mild dementia symptoms were more likely to have more unmet needs.

Because persons living with dementia are unique individuals—with their own values, including concerns related to privacy; needs; and preferences for services, supports, and medical care—the specific goals for and forms of care, services, and supports will depend on the individual. The recognition that persons living with dementia are still individuals is important to supporting them in leading lives with meaning, pleasure, and joy. Good care for persons living with dementia is about living a daily life, which is a deeply personal experience that draws on personal values and goals. Individuals have wide latitude to define what matters to them, what is fun, and what is boring. As a consequence of such cognitive problems as aphasia and impaired thought processing (Gitlin and Hodgson, 2018), however, persons with dementia may struggle to express their preferences, values, and goals, and their needs evolve over time.

Persons living with dementia have cognitive impairment that results in a disability, which is partially socially constructed by the way society views the disease and designs the living environment. To deal with their disabilities, persons living with dementia need accommodations that change how they interact with their environment, just as do persons with physical disabilities. Society has a legally recognized obligation to provide accom-

modations for persons with physical and mental disabilities.1 For example, a person with paraplegia following spinal cord injury cannot enter a building via a flight of stairs. With the accommodation of a ramp or lift or the design of buildings without stairs, the impairment in leg mobility remains, but the ability to enter the building is supported. The recognition of persons living with dementia as experiencing a disability creates a parallel societal obligation to provide accommodations for that disability.

The disabilities experienced by persons living with dementia as a result of their cognitive impairments differ from the disabilities caused by physical impairments, and the accommodations they need differ accordingly. Their disabilities may be accommodated in part by such devices as a pill box, a list, a smartphone, and someday perhaps even a robot, especially as they transition from MCI to the mild stage of dementia and beyond. Because of the cognitive nature of their impairment, as well as the moral and creative dimensions of caregiving, these devices cannot fully substitute for a care partner or caregiver. A central premise of this report, then, is that the disabilities experienced by a person with dementia are generally accommodated by one or more people who help compensate for the person’s cognitive impairments. These people—whether care partners, caregivers, or networks of people that change over time—represent an essential care component for persons living with dementia, who often rely on and want their involvement. They provide an accommodation for the cognitive nature of the disability by supporting another person’s desires, needs, and preferences for living in the world and acting with intention to support and care for the person, particularly as he or she progresses to more advanced stages of the condition. People with other conditions, such as those who have had a stroke or persons with Parkinson’s disease, may face similar challenges and similarly rely on care partners and caregivers; however, some persons living with dementia may not have any physical impairments but live with significant cognitive impairment.

The Role and Experience of Care Partners and Caregivers

Care partners and caregivers may be individuals who have an existing relationship with the person with dementia, such as close friends, a spouse, and other family members, or they may be direct care workers. A person with dementia may also rely on a combination of care partners and caregivers within their network of caregiving supports, which may change over time as the person’s needs evolve. As of 2015, 21.6 million people in the United States were providing unpaid care for persons living with demen-

___________________

1 Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (amended 2008), Public Law 101-336, 101st Cong. (July 26, 1990).

tia (Chi et al., 2019). One study estimates that only about one-quarter of persons living with dementia receive any care from a paid caregiver, and just 10 percent receive at least 20 hours of such care per week (Reckrey et al., 2020). Another study estimates that 63 percent of persons living with dementia receive only unpaid care, 5 percent receive only paid care, and 26 percent receive some combination of the two (Chi et al., 2019). While data are lacking on the number of persons living with dementia who do not receive any care from a care partner or caregiver, it is estimated that this is the case for 5 percent of persons living with dementia (Chi et al., 2019).

Care partners and caregivers engage in numerous roles and activities. They provide supports, services, programs, accommodations, or practices related to personal care (e.g., assisting with personal hygiene or getting dressed), and they help with medication management, paying bills, transportation, meal preparation, and health maintenance tasks (NASEM, 2016). They assist with activities, such as using transportation, cooking, managing finances, shopping, and cleaning a home, that allow a person to live independently in the community. In later stages of dementia, they assist with such self-care activities as transferring from a bed to a chair, bathing, getting dressed, feeding, and using the bathroom. The assistance they provide may be direct, or it may entail cueing the person to perform the activity. As caregivers assist with daily activities, they often take on the role of helping to make decisions; the two roles are often blended. For example, a caregiver may assist in preparing or even entirely providing dinner for a person with dementia, using person-centered techniques that might include some combination of such activities as asking the person what he or she would like to eat for dinner, doing the food shopping, and cooking the meal. Another role they may take on is attending medical and social service visits to help organize and deliver care to the person with dementia. The person living with dementia is considered the primary informant; for example, someone living with advanced symptoms of dementia can inform about experiencing pain through facial expressions. In the later stages of dementia, however, care partners and caregivers take on a greater role and often can provide useful contextual information, such as how often the pain occurs, under what circumstances, and with what associated symptoms. All of these roles ideally ensure that the person living with dementia lives a typical day that is safe and social and is engaged in meaningful activities. Sadly, however, this is not the case for many individuals throughout society, including persons living with dementia (Black et al., 2013).

Those who provide care for persons with dementia often experience positive aspects of caregiving, including a deeper appreciation for life, satisfaction with additional meaning in one’s life, and strengthening of the relationship with the person living with dementia (NASEM, 2016; Roth et al., 2015). At the same time, however, care partners and caregivers also

report stress and depression, loss of income, decreased well-being, and other consequences related to physical and mental health, family conflict, and social isolation (NASEM, 2016; Pinquart and Sörensen, 2003). Fully 97 percent of care partners and caregivers reported at least one unmet need, with an average of 4.6 unmet needs per caregiver (Black et al., 2013). Of these unmet needs, 89 percent were related to resource referrals, 85 percent to dementia education, and 45 percent to mental health care needs. The risk factors associated with a higher number of unmet needs for care partners and caregivers included being a racial minority and having lower educational attainment. Neither unpaid nor paid caregivers, such as home health aides or certified nursing assistants, receive adequate training and support for this challenging work (Burgdorf et al., 2019; NASEM, 2016).

Conceptions, perceptions, and experiences of the caregiving role vary significantly, including by culture, socioeconomic status, and educational level (Fabius et al., 2020; NASEM, 2016; Pinquart and Sörensen, 2005). Some care partners and caregivers may not see themselves as being in this role, instead perceiving their actions as an extension of existing familial roles, such as being a good spouse. In certain cultures, such as specific Latino cultures, the term caregiver is not used (Karlawish et al., 2011). If people who serve as care partners or caregivers do not see themselves in that role, they are unlikely to seek out and access services and supports even if available. Similarly, distrust of medical institutions, conceptions of the caregiving role as one of family responsibility, and feelings of shame have been described as factors that make African American and Asian American care partners and caregivers less likely to seek medical care and supports outside of the family (Apesoa-Varano et al., 2015; Dilworth-Anderson and Gibson, 2002).

A Complex and Dynamic Situation

As discussed above, dementia effectively joins at least two people: one the person living with dementia and the other a person or persons who provide care and support. While the focus is sometimes on a single care partner or caregiver—often a spouse or a child—persons living with dementia may receive support and help from combinations and networks of unpaid and paid caregivers, who may themselves be employed directly or associated with an agency, community organization, or residential facility. Together, persons living with dementia and their networks of care partners and caregivers need guidance and support that are essential to enable living in a rewarding way. They need education, guidance, and support to assist with activities of daily living and with planning and making decisions together, and they need medical and social services that help in organizing and delivering care. This guidance and support can ensure that both parties

can enjoy a life that is safe, social, and engaged and that neither party experiences emotional, physical, or financial harms.

EVOLUTION OF THE UNDERSTANDING OF DEMENTIA AND DEMENTIA CARE

In the past 40 years, the United States has experienced two revolutions in thinking about persons living with dementia. What was once considered an extreme stage of normal aging of little medical importance became a consequence of diseases requiring medical attention—research, diagnosis, treatment, and care. What was once part of the duties of family members became more broadly recognized as a distinct role that has health and economic consequences.

Recognition of Dementia as a Medical Condition

Until the last two decades of the 20th century, late-life dementia was not widely recognized as the consequence of a disease. Older adults with dementia were described as having an extreme state of aging termed “senility,” while adults with early-onset dementia were considered mentally ill (Ballenger, 2017). In fact, it was not until the 1940s and 1950s that the health care system began to take interest in the diagnosis and treatment of “the senile,” abandoning earlier conceptions of dementia symptoms as an inevitable result of aging, which led to more widespread recognition of dementia as a public health issue beginning in the 1970s. Care for individuals with dementia was considered solely a private family matter, and the care of persons who lacked a family or whose family was unable to care for them became a matter of state welfare, typically provided in asylums and variations on facilities called “old age homes.”

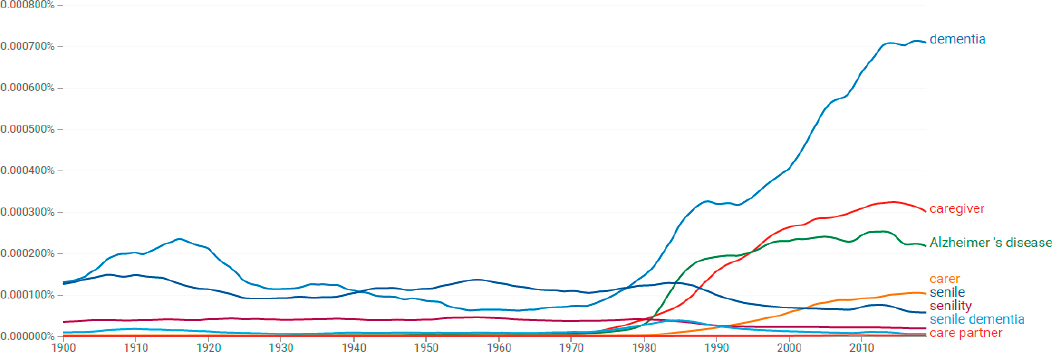

Figure 2-2 uses the results of a Google n-gram—a year-to-year summary of the frequency of a word’s use in the English language—to illustrate the rapid redefinition and reframing of dementia. The figure shows how by the close of the 20th century, the term “senility” rapidly faded. In contrast, use of the terms “dementia” and “Alzheimer’s disease” (the most common neurodegenerative disease thought to cause dementia) increased. Of late, the language has been further nuanced to truly distinguish the person from the disease and the illness experience, as exemplified by this report’s use of the term “a person living with dementia.” While most care continues to be delivered solely by family caregivers, there is now greater recognition of dementia care, services, and supports as a societal concern and responsibility, as described in greater detail below.

SOURCE: Google Books Ngram Viewer.

Increasing Recognition of the Role and Consequences of Caregiving

Prior to the 1970s, the term “caregiver” was rarely used in the health, social service, or medical care literature. Figure 2-2 illustrates the sudden appearance and rapid rise of this term beginning in the 1980s. As noted above, prior to that time, caregiving was not recognized as distinct from other family roles. People did not self-identify as caregivers, attend support groups, or receive other supports and services designed for caregivers. A paid caregiver was variously referred to as a nurse, aide, or maid.

Starting in the late 1970s this situation began to change. The term “caregiver” (as well as such variations as “carer” and “caretaker”) appeared abruptly (Brody, 1981; Shanas, 1979). Use of the term, which is not specific to dementia, grew rapidly. By the 1980s, the Alzheimer’s Association, a national self-help organization, was offering support groups and training for caregivers (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020b). Its first public service announcement, delivered in 1990 by the eminent journalist Walter Cronkite, stated: “Today, there are at least 4 million victims of Alzheimer’s disease. But for almost every one of those victims, there is another, a husband or wife … a son or daughter … whose entire life changes with the demands of caregiving” (Alzheimer’s Association, 1990). Such a statement would not have been heard in 1980.

Recognition of the role of the caregiver has been critical to improving dementia care. Caregiving is now recognized as part of the experience of dementia, such that the hours spent caregiving are used as facts and figures to describe the disease. In 2015, for example, a person living with dementia received an average of 127 hours of assistance per month from one or more unpaid caregivers (Chi et al., 2019), and it is estimated that this unpaid caregiving had an annual monetary value of $50–$106 billion as of 2010 (Hurd et al., 2013). This figure includes the cost of caregivers’ lost wages and the value of their labor in providing care; another estimate that considers lost wages and indirect costs to caregivers’ well-being places the cost of just the unpaid care provided by daughters to mothers at $277 billion (Coe et al., 2018).

These figures are critical to understanding the size and scope of the dementia experience. When the hours devoted to caregiving are seen as work, they can be assigned a wage, and the wages of caregiving add up to nearly half of the costs of dementia in the United States (Hurd et al., 2013). Put another way, a substantial portion of the multi-billion-dollar cost of dementia to the nation consists of lost wages and other opportunity costs due to providing care instead of working in the “traditional” labor force. The average lifetime cost of dementia from time of diagnosis is $321,780, with families assuming 70 percent ($225,140) of this cost (Jutkowitz et al., 2017).

Moving Toward Person-Centered and Strengths-Based Approaches

Person-centered care—care that responds to the needs and preferences of the individual—has been increasing as a priority in health care over the past few decades (IOM, 2001). Increased adoption of person-centered care is also a growing focus in nursing home care and LTSS, as exemplified by Congress’s call in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 for the secretary of health and human services to develop regulations to ensure the delivery of patient-centered care in home- and community-based LTSS.2 Person-centered care incorporates an understanding of an individual’s culture and the challenges faced by members of that culture as well as their strengths, but is not restricted to cultural competence, recognizing that individuals within a culture also differ from one another (Epner and Baile, 2012).

Strengths-based approaches are a component of person-centered care that involves assessing and building on individuals’ strengths, abilities, and available resources to promote their well-being and growth (McGovern, 2015; Moyle, 2014). In dementia care, adopting a strengths-based approach requires a focus on the present and on what abilities remain rather than what has been lost (Dementia Action Alliance and The Eden Alternative, 2020; McGovern, 2015). For example, tasks can be divided into smaller components that allow persons living with dementia to focus on their strengths, as well as create opportunities for growth and development of other capabilities (Dementia Action Alliance and The Eden Alternative, 2020). Importantly, an individual’s abilities, interests, and strengths will change over time, and care partners and caregivers need to be flexible to respond to those changes so the person living with dementia is empowered to grow to the fullest extent possible. For example, an individual interested in music and the arts might be provided opportunities to actively make art and music in the earlier stages of dementia, and transition to spending time at museums or concerts with loved ones as symptoms progress. Strengths-based assessments can help identify an individual’s emotional and behavioral skills, competencies, and characteristics in order to build on these strengths (Moyle, 2014). A strengths-based approach can empower persons living with dementia with the decision-making ability to determine the level of assistance needed while supporting the ability of care partners and caregivers to provide appropriate care (Dementia Action Alliance and The Eden Alternative, 2020). Indeed, the ways in which care partners and caregivers express their experiences, such as personal growth, the development of strengths, and a closer relationship with the person living with dementia, often accord with strengths-based perspectives (Peacock et al., 2010).

___________________

2 42 USC 1396n note. Regulations. Oversight and Assessment of the Administration of Home and Community-based Services.

Person-centered and strengths-based approaches may help shift the focus from the diagnosis of dementia to the person living with dementia and the accommodations and lifestyle changes that can be adopted to support the person in leading a rewarding life.

Policy Implications

The recognition of dementia as a consequence of disease and of someone who cares for a person with dementia as a care partner or caregiver has notable policy implications. It argues for the responsibility of the care system—including medical care; LTSS; and other social services and supports, such as respite care, adult day activity programs, and transportation—to provide care and support for persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers. One major challenge is that there is recognition of a workforce shortage for geriatric practitioners generally (IOM, 2008), as well as for direct care providers, such as nurse aides and home health aides, who tend to deliver care in long-term care facilities or in an individual’s home (Scales, 2020). As the number of Americans over age 65 diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias is expected to grow, so, too, is the demand for direct care workers (PHI, 2020). Yet, projections show that the shortages in the direct care workforce will increase from 2018 to 2028 (PHI, 2020), compounded by a high rate of turnover in the field (Scales, 2020). Thus, there is a need to improve recruitment and retention in this field (IOM, 2008).

This increased recognition of societal responsibility is reflected in the U.S. National Alzheimer’s Plan, initiated in 2012 through the National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA). The first goal of this plan is to prevent and effectively treat Alzheimer’s disease by 2025 (ASPE, 2020). However, recognizing that persons living with dementia, care partners, and caregivers need support now and for the foreseeable future, the second and third goals are to optimize the quality and efficiency of care, and to expand supports for people living with Alzheimer’s disease and their families. Curing and caring are appropriately viewed as in harmony for dementia, as they are for other conditions, such as cancer and cardiovascular disease.3

Supporting the goals of the National Alzheimer’s Plan, the National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers was convened in 2017 by the National

___________________

3 For example, the cancer centers funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) recognize the need to harmonize cures and care. The criteria for a Cancer Center Support Grant include the expectation that the NCI-designated cancer center director will align research and care missions, as described in the Request for Applications at https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/par-20-043.html (accessed January 28, 2021).

Advisory Panel on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services, and again in 2020 by the National Institute on Aging (NIA). These summits bring stakeholders together to discuss evidence-based programs, strategies, and approaches for improving dementia care, services, and supports, as well as to identify research gaps and opportunities in the field (NIA, 2020). Consistent with the movement toward person-centered approaches described above, the summits incorporate and highlight voices of persons living with dementia, care partners, and caregivers, as well as researchers, care organizations, and other stakeholders. In addition, advocacy organizations, such as the Alzheimer’s Association, are collaborating with various partners to carry out specific actions of the National Alzheimer’s Plan (HHS, 2019), and other organizations, such as the National Alliance for Caregiving and the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America, have provided guidance on how to implement the plan at the state and local levels (National Alliance for Caregiving and Alzheimer’s Foundation of America, 2014). Also involved in advocacy for policy change are such groups as The Alzheimer’s Impact Movement and Activists Against Alzheimer’s, the advocacy affiliates of the Alzheimer’s Association and UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, respectively, which bring together volunteers who promote federal and state policy regarding dementia research and care (Alzheimer’s Impact Movement, n.d.; UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, 2020).

GUIDING PRINCIPLES AND CORE COMPONENTS OF DEMENTIA CARE, SERVICES, AND SUPPORTS

The concepts outlined above provide the basis for a set of guiding principles for dementia care, services, and supports (see Box 2-1). In addition, various core components of dementia care services and supports have been identified (see Box 2-2). Together, these guiding principles and core components reflect shared community values that include principles of good/ethical care, standards of care, justice, and human dignity and thriving.

The lack of evidence available to answer the questions posed in the committee’s charge (see Box 1-1 in Chapter 1), as detailed in subsequent chapters, does not call these fundamental principles or core components into question. Rather, it points to the need for additional research and programmatic assessment to address the gaps in information about specific interventions. In the interim, these guiding principles and core components can be used immediately by organizations, agencies, communities, and individuals to guide their actions toward improving dementia care, supports, and services. Given the critical shortcomings that now exist, if persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers had access to care, services, and supports guided by these principles and including these components, this would represent a significant advance.

Furthermore, there are many activities, such as listening to music and dancing, that provide pleasure for many people living with or without dementia and likely have little potential harm apart from opportunity and financial costs. At the individual or family level, persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers may want to experiment with these types of activities, tailored to their own interests, to see what works for them, knowing this may change as the person’s condition progresses.

REFERENCES

Alzheimer’s Association. 1990. 4 million. In Walter Cronkite Papers, 1932–2014. Austin: Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas.

Alzheimer’s Association. 2020a. 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 16(3):391–460.

Alzheimer’s Association. 2020b. Our story. https://www.alz.org/about/our_story (accessed November 23, 2020).

Alzheimer’s Association and SAGE. 2018. Issues brief: LGBT and dementia. https://www.alz.org/media/documents/lgbt-dementia-issues-brief.pdf (accessed December 22, 2020).

Alzheimer’s Impact Movement. n.d. About the Alzheimer’s impact movement. https://alzimpact.org/about (accessed November 11, 2020).

Apesoa-Varano, E. C., Y. Tang-Feldman, S. C. Reinhard, R. Choula, and H. M. Young. 2015. Multi-cultural caregiving and caregiver interventions: A look back and a call for future action. Generations 39(4):39–48.

ASPE (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation). 2020. National plans to address Alzheimer’s disease. https://aspe.hhs.gov/national-plans-address-alzheimers-disease (accessed January 15, 2021).

Ballenger, J. F. 2017. Framing confusion: Dementia, society, and history. American Medical Association Journal of Ethics 19(7):713–719.

Benjamin Rose Institute on Aging and FCA (Family Caregiver Alliance). 2020. Best practice caregiving. https://bpc.caregiver.org/#searchPrograms (accessed August 12, 2020).

Black, B. S., D. Johnston, P. V. Rabins, A. Morrison, C. Lyketsos, and Q. M. Samus. 2013. Unmet needs of community-residing persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: Findings from the maximizing independence at home study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 61(12):2087–2095.

Black, B. S., D. Johnston, J. Leoutsakos, M. Reuland, J. Kelly, H. Amjad, K. Davis, A. Willink, D. Sloan, C. Lyketsos, and Q. M. Samus. 2019. Unmet needs in community-living persons with dementia are common, often non-medical and related to patient and caregiver characteristics. International Psychogeriatrics 31(11):1643–1654.

Boustani, M., C. A. Alder, C. A. Solid, and D. Reuben. 2019. An alternative payment model to support widespread use of collaborative dementia care models. Health Affairs 38(1):54–59.

Brody, E. M. 1981. “Women in the middle” and family help to older people. Gerontologist 21(5):471–480.

Burgdorf, J., D. L. Roth, C. Riffin, and J. L. Wolff. 2019. Factors associated with receipt of training among caregivers of older adults. JAMA Internal Medicine 179(6):833–835.

Chi, W., E. Graf, L. Hughes, J. Hastie, G. Khatutsky, S. B. Shuman, E. A. Jessup, S. Karon, and H. Lamont. 2019. Community-dwelling older adults with dementia and their caregivers: Key indicators from the national health and aging trends study. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Coe, N. B., M. M. Skira, and E. B. Larson. 2018. A comprehensive measure of the costs of caring for a parent: Differences according to functional status. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 66(10):2003–2008.

Dementia Action Alliance and The Eden Alternative. 2020. Practice guide for assisted living communities: Person- and relationship-centered dementia support. https://www.edenalt-evolve.org/courses/raising-the-bar-practice-guide-assisted-living (accessed January 20, 2021).

Dilworth-Anderson, P., and B. E. Gibson. 2002. The cultural influence of values, norms, meanings, and perceptions in understanding dementia in ethnic minorities. Alzheimer’s Disease & Associated Disorders 16:S56–S63.

Epner, D. E., and W. F. Baile. 2012. Patient-centered care: The key to cultural competence. Annals of Oncology 23(Suppl 3):33–42.

Fabius, C. D., J. L. Wolff, and J. D. Kasper. 2020. Race differences in characteristics and experiences of black and white caregivers of older americans. Gerontologist 60(7):1244–1253.

Fazio, S., D. Pace, K. Maslow, S. Zimmerman, and B. Kallmyer. 2018. Alzheimer’s Association dementia care practice recommendations. Gerontologist 58(Suppl 1):S1–S9.

Gitlin, L. N., and N. Hodgson. 2018. Better living with dementia: Implications for individuals, families, communities, and societies. London, UK: Academic Press.

Gould, E., K. Maslow, M. Lepore, L. Bercaw, J. Leopold, B. Lyda-McDonald, M. Ignaczak, P. Yuen, and J. M. Wiener. 2015. Identifying and meeting the needs of individuals with dementia who live alone. Washington, DC: RTI International.

Haaksma, M. L., A. Calderón-Larrañaga, M. G. M. Olde Rikkert, R. J. F. Melis, and J. S. Leoutsakos. 2018. Cognitive and functional progression in Alzheimer disease: A prediction model of latent classes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 33(8):1057–1064.

Han, A., J. Radel, J. M. McDowd, and D. Sabata. 2016. Perspectives of people with dementia about meaningful activities: A synthesis. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias 31(2):115–123.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2019. National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease: 2019 update. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/262601/NatlPlan2019.pdf (accessed October 1, 2020).

Hulko, W. 2009. From “not a big deal” to “hellish”: Experiences of older people with dementia. Journal of Aging Studies 23(3):131–144.

Hurd, M. D., P. Martorell, A. Delavande, K. J. Mullen, and K. M. Langa. 2013. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 368(14):1326–1334.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2008. Retooling for an aging America: Building the health care workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jennings, L. A., A. Palimaru, M. G. Corona, X. E. Cagigas, K. D. Ramirez, T. Zhao, R. D. Hays, N. S. Wenger, and D. B. Reuben. 2017. Patient and caregiver goals for dementia care. Quality of Life Research 26(3):685–693.

Jutkowitz, E., R. L. Kane, J. E. Gaugler, R. F. MacLehose, B. Dowd, and K. M. Kuntz. 2017. Societal and family lifetime cost of dementia: Implications for policy. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 65(10):2169–2175.

Karlawish, J., F. K. Barg, D. Augsburger, J. Beaver, A. Ferguson, and J. Nunez. 2011. What Latino Puerto Ricans and non-Latinos say when they talk about Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 7(2):161–170.

Livingston, G., J. Huntley, A. Sommerlad, D. Ames, C. Ballard, S. Banerjee, C. Brayne, A. Burns, J. Cohen-Mansfield, C. Cooper, S. G. Costafreda, A. Dias, N. Fox, L. N. Gitlin, R. Howard, H. C. Kales, M. Kivimäki, E. B. Larson, A. Ogunniyi, V. Orgeta, K. Ritchie, K. Rockwood, E. L. Sampson, Q. Samus, L. S. Schneider, G. Selbæk, L. Teri, and N. Mukadam. 2020. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet 396(10248):413–446.

Martyr, A., S. M. Nelis, C. Quinn, Y.-T. Wu, R. A. Lamont, C. Henderson, R. Clarke, J. V. Hindle, J. M. Thom, I. R. Jones, R. G. Morris, J. M. Rusted, C. R. Victor, and L. Clare. 2018. Living well with dementia: A systematic review and correlational meta-analysis of factors associated with quality of life, well-being and life satisfaction in people with dementia. Psychological Medicine 48(13):2130–2139.

McGovern, J. 2015. Living better with dementia: Strengths-based social work practice and dementia care. Social Work in Health Care 54(5):408–421.

Moyle, W. 2014. Principles of strengths-based care and other nursing models. In Care of older adults: A strengths-based approach, edited by W. Moyle, D. Parker, and M. Bramble. Port Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Families caring for an aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Alliance for Caregiving and Alzheimer’s Foundation of America. 2014. From plan to practice: Implementing the national Alzheimer’s plan in your state. https://www.caregiving.org/creating-an-alzheimers-plan-for-your-state (accessed January 20, 2021).

NIA (National Institute on Aging). 2020. Summit virtual meeting series: 2020 National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers. https://www.nia.nih.gov/2020-dementia-care-summit#Registration (accessed September 1, 2020).

Nichols, E., C. E. I. Szoeke, S. E. Vollset, N. Abbasi, F. Abd-Allah, J. Abdela, M. T. E. Aichour, R. O. Akinyemi, F. Alahdab, S. W. Asgedom, A. Awasthi, S. L. Barker-Collo, B. T. Baune, Y. Béjot, A. B. Belachew, D. A. Bennett, B. Biadgo, A. Bijani, M. S. Bin Sayeed, C. Brayne, D. O. Carpenter, F. Carvalho, F. Catalá-López, E. Cerin, J.-Y. J. Choi, A. K. Dang, M. G. Degefa, S. Djalalinia, M. Dubey, E. E. Duken, D. Edvardsson, M. Endres, S. Eskandarieh, A. Faro, F. Farzadfar, S.-M. Fereshtehnejad, E. Fernandes, I. Filip, F. Fischer, A. K. Gebre, D. Geremew, M. Ghasemi-Kasman, E. V. Gnedovskaya, R. Gupta, V. Hachinski, T. B. Hagos, S. Hamidi, G. J. Hankey, J. M. Haro, S. I. Hay, S. S. N. Irvani, R. P. Jha, J. B. Jonas, R. Kalani, A. Karch, A. Kasaeian, Y. S. Khader, I. A. Khalil, E. A. Khan, T. Khanna, T. A. M. Khoja, J. Khubchandani, A. Kisa, K. Kissimova-Skarbek, M. Kivimäki, A. Koyanagi, K. J. Krohn, G. Logroscino, S. Lorkowski, M. Majdan, R. Malekzadeh, W. März, J. Massano, G. Mengistu, A. Meretoja, M. Mohammadi, M. MohammadiKhanaposhtani, A. H. Mokdad, S. Mondello, G. Moradi, G. Nagel, M. Naghavi, G. Naik, L. H. Nguyen, T. H. Nguyen, Y. L. Nirayo, M. R. Nixon, R. Ofori-Asenso, F. A. Ogbo, A. T. Olagunju, M. O. Owolabi, S. Panda-Jonas, V. M. d. A. Passos, D. M. Pereira, G. D. Pinilla-Monsalve, M. A. Piradov, C. D. Pond, H. Poustchi, M. Qorbani, A. Radfar, R. C. Reiner, Jr., S. R. Robinson, G. Roshandel, A. Rostami, T. C. Russ, P. S. Sachdev, H. Safari, S. Safiri, R. Sahathevan, Y. Salimi, M. Satpathy, M. Sawhney, M. Saylan, S. G. Sepanlou, A. Shafieesabet, M. A. Shaikh, M. A. Sahraian, M. Shigematsu, R. Shiri, I. Shiue, J. P. Silva, M. Smith, S. Sobhani, D. J. Stein, R. Tabarés-Seisdedos, M. R. Tovani-Palone, B. X. Tran, T. T. Tran, A. T. Tsegay, I. Ullah, N. Venketasubramanian, V. Vlassov, Y.-P. Wang, J. Weiss, R. Westerman, T. Wijeratne, G. M. A. Wyper, Y. Yano, E. M. Yimer, N. Yonemoto, M. Yousefifard, Z. Zaidi, Z. Zare, T. Vos, V. L. Feigin, and C. J. L. Murray. 2019. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. The Lancet Neurology 18(1):88–106.

NQF (National Quality Forum). 2014. Priority setting for healthcare performance measurement: Addressing performance measure gaps for dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. http://www.qualityforum.org/priority_setting_for_healthcare_performance_measurement_alzheimers_disease.aspx (accessed September 4, 2020).

NRC (National Research Council). 2010. The role of human factors in home health care: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Peacock, S., D. Forbes, M. Markle-Reid, P. Hawranik, D. Morgan, L. Jansen, B. D. Leipert, and S. R. Henderson. 2010. The positive aspects of the caregiving journey with dementia: Using a strengths-based perspective to reveal opportunities. Journal of Applied Gerontology 29(5):640–659.

Petersen, R. C., R. O. Roberts, D. S. Knopman, B. F. Boeve, Y. E. Geda, R. J. Ivnik, G. E. Smith, and C. R. Jack, Jr. 2009. Mild cognitive impairment: Ten years later. Archives of Neurology 66(12):1447–1455.

PHI. 2020. Direct care workers in the United States: Key facts. New York: PHI.

Pinquart, M., and S. Sörensen. 2003. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging 18(2):250–267.

Pinquart, M., and S. Sörensen. 2005. Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: A meta-analysis. Gerontologist 45(1):90–106.

Reckrey, J. M., R. S. Morrison, K. Boerner, S. L. Szanton, E. Bollens-Lund, B. Leff, and K. A. Ornstein. 2020. Living in the community with dementia: Who receives paid care? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 68(1):186–191.

Roth, D. L., P. Dilworth-Anderson, J. Huang, A. L. Gross, and L. N. Gitlin. 2015. Positive aspects of family caregiving for dementia: Differential item functioning by race. Journals of Gerontology: Series B 70(6):813–819.

Satizabal, C. L., A. S. Beiser, V. Chouraki, G. Chêne, C. Dufouil, and S. Seshadri. 2016. Incidence of dementia over three decades in the Framingham Heart Study. New England Journal of Medicine 374(6):523–532.

Scales, K. 2020. It’s time to care: A detailed profile of America’s direct care workforce. New York: PHI.

Shanas, E. 1979. The family as a social support system in old age. Gerontologist 19(2):169–174.

Thach, N. T., and J. M. Wiener. 2018. An overview of long-term services and supports and Medicaid: Final report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Thoits, T., A. Dutkiewicz, S. Raguckas, M. Lawrence, J. Parker, J. Keeley, N. Andersen, M. VanDyken, and M. Hatfield-Eldred. 2018. Association between dementia severity and recommended lifestyle changes: A retrospective cohort study. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias 33(4):242–246.

Tom, S. E., R. A. Hubbard, P. K. Crane, S. J. Haneuse, J. Bowen, W. C. McCormick, S. McCurry, and E. B. Larson. 2015. Characterization of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in an older population: Updated incidence and life expectancy with and without dementia. American Journal of Public Health 105(2):408–413.

Tschanz, J. T., C. D. Corcoran, S. Schwartz, K. Treiber, R. C. Green, M. C. Norton, M. M. Mielke, K. Piercy, M. Steinberg, P. V. Rabins, J.-M. Leoutsakos, K. A. Welsh-Bohmer, J. C. S. Breitner, and C. G. Lyketsos. 2011. Progression of cognitive, functional, and neuropsychiatric symptom domains in a population cohort with Alzheimer dementia: The Cache County Dementia Progression study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 19(6):532–542.

UsAgainstAlzheimer’s. 2020. Activists against Alzheimer’s. https://www.usagainstalzheimers.org/networks/activists (accessed November 11, 2020).

Zimmerman, S., W. Anderson, S. Brode, D. Jonas, L. Lux, A. Beeber, L. Watson, M. Viswanathan, K. Lohr, J. Cook Middleton, L. Jackson, and P. Sloane. 2011. Comparison of characteristics of nursing homes and other residential long-term care settings for people with dementia. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 79. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

This page intentionally left blank.