3

COMPLEXITY OF SYSTEMS FOR DEMENTIA CARE, SERVICES, AND SUPPORTS

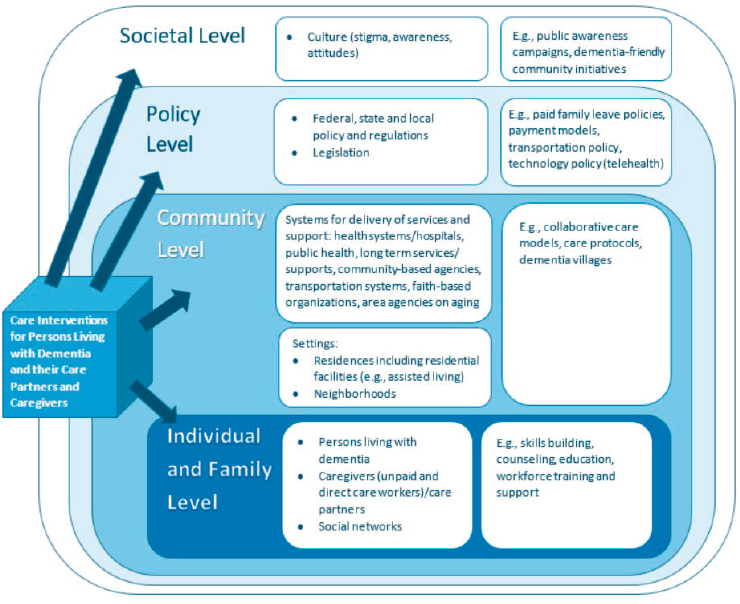

This chapter describes the complex systems in which dementia care interventions are implemented and how these complexities factor into an assessment of the evidence derived from these interventions. It begins by describing a multilevel framework the committee used to organize the conceptualization of different kinds of care interventions for persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers and to aid in identifying gaps in the existing knowledge base (those gaps are discussed further in Chapter 5). The chapter then goes on to describe the challenges inherent in assessing evidence from dementia care interventions. That section ends by identifying some of the principal actors and programs that make up the complex system of dementia care in the United States.

A MULTILEVEL FRAMEWORK FOR CARE INTERVENTIONS FOR PERSONS LIVING WITH DEMENTIA AND THEIR CARE PARTNERS AND CAREGIVERS

The broad range and heterogeneity of the dementia care interventions evaluated in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) systematic review necessitated a framework with which the committee could structure its assessment of the interventions and their readiness for broad dissemination and implementation. To this end, the committee adapted a multilevel framework previously developed to organize the literature for caregiving interventions (NASEM, 2016). The resulting framework (see Figure 3-1) depicts the multifaceted context in which dementia care is provided and received. This context encompasses a wide range of care settings

SOURCE: Adapted from NASEM, 2016.

(e.g., private homes, residential care facilities) and significant heterogeneity in the social and community networks of persons living with dementia (e.g., family members, friends, workplaces, health care organizations, community- and faith-based organizations), as well as in the societal and policy (federal, state, and local) environments. Applying this framework allows dementia care interventions to be categorized as targeting various levels—individual and family, community, policy, and societal—either alone or in combination. As depicted in the figure, the levels are nested, and there is a dynamic interplay among them (i.e., individuals and families reside and receive care, services, and supports in communities, which in turn exist within policy environments, which are influenced by societal perceptions and cultural norms).

Individual and Family Level

Interventions at the individual and family level directly target persons living with dementia or care partners and caregivers, and are generally designed to alter some aspect of behavior or risk (e.g., depression, strain). As discussed in Chapter 2, care partners and caregivers may be family members and/or friends of the person living with dementia or paid providers. In considering interventions at this level, it is important to recognize that individual care arrangements often extend beyond a person living with dementia–caregiver dyad to a broader network of engaged family, friends, and paid caregivers. These helping networks are recognized as being dynamic in response to the evolving care needs of persons living with dementia and the circumstances of care partners and caregivers, who may be managing multiple employment and family responsibilities or may experience health or financial circumstances that affect their ability to provide care (NASEM, 2016). Many of the interventions examined in the AHRQ systematic review, such as psychosocial interventions, exercise, reminiscence therapy, and multicomponent interventions (which often include psychotherapeutic, education and skills building, and social support components), target persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers. Outcomes of individual- and family-level interventions examined in the existing evidence base often relate to the physical and emotional health of persons living with dementia or care partners/caregivers,1 their knowledge and skills, the duration of care, and the economic effects on the individual or family unit. An example of an individual-level intervention is the New York University Spouse-Caregiver Intervention Study, which evaluated the effect of individual and family counseling and support (via support groups) for spouse-caregivers of persons living with Alzheimer’s disease on the caregivers’ depressive symptoms (Mittelman et al., 1996, 2004).

Community Level

The organizing framework depicted in Figure 3-1 conceptualizes communities broadly as encompassing a range of care and support systems, as well as residential care settings, including private homes, where persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers live and have the opportunity for a meaningful life. Systems in this context encompass health care, public health, social services agencies, and organizations providing long-term services and supports (LTSS).

___________________

1 Interventions that target the health or well-being of direct care workers are categorized as individual-level interventions, but those that aim to alter process or system outcomes (e.g., training of direct care workers to improve care coordination) are addressed in the section on community-level interventions.

The committee considered systems and settings together under the broader umbrella of the community level in recognition of their matrixed nature. That is, systems that address the continuum of care, services, and supports required by persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers to meet functional needs and those that address public health prevention and wellness function in a multitude of care settings within communities (NQF, 2014). Some interventions at this level specifically target the interface between delivery systems and care settings. For example, dementia villages are residential settings designed and operated around the care and support needs of persons living with dementia, providing housing, food, security, opportunities for social interaction, and access to a range of medical care and LTSS (Haeusermann, 2018). Other interventions at the community level, such as collaborative care models, may be focused on altering the structure or operation of systems for delivery of services and supports. Such interventions often require adjustments to workflow or a reconfiguring of the connections between service delivery and community agencies. Relevant examples include the connections between health systems and community-based organizations (CBOs), such as an area agency on aging or a subsidized housing organization (NASEM, 2016). The framework also recognizes that communities have myriad other resources (e.g., religious and art institutions, libraries, senior centers) that can play vital roles in the support of persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers, although access to community institutions and the services they provide varies depending on where people live (NASEM, 2016).

Thus, interventions that target the community level are diverse and should not be considered in isolation. Note also that outcomes for community-targeted interventions may be measured at the payer (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid, private insurer), organizational (e.g., service delivery), or individual (e.g., quality of life, strain) level.

Policy Level

Interventions at the policy level include federal, state, and local legislation, regulations, and policies that affect available supports and services for persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers. Examples include insurance reimbursement policies, such as the structure and generosity of Medicaid coverage of LTSS; state and federal policies regarding paid and unpaid leave for caregivers (e.g., the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993); changes to Medicare reimbursement that support dementia care planning; state and federal regulations requiring the delivery of person-centered care; and state- and federal-level dementia training requirements for certified nursing assistants and home health and home care aides (NASEM, 2016). Policy-level interventions can offer myriad benefits to persons living

with dementia and their care partners and caregivers, such as reducing personal expenditures for medical care and other supports and services; increasing access to services; creating financial and quality incentives for health systems, LTSS providers, and CBOs to coordinate and integrate services; establishing expectations that the needs of caregivers of persons living with dementia will be assessed and supported; and providing employment protection for care partners and caregivers. Outcomes of such interventions may be measured at the individual, organizational, payer, or population level.

Societal Level

Societal-level interventions encompass strategies that affect how society views dementia by targeting the consciousness and perceptions of a population (e.g., awareness, stigma). Such strategies take into account the cultural variation in how dementia is defined, perceived, and addressed at the individual, community, and policy levels. For example, the stigma faced by persons living with dementia is often entangled with ageism that is pervasive in many societies (Evans, 2018). As discussed in Chapter 2, societal understanding of and views on dementia may affect policy making and decisions about investments in supports and services for persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers. Issues related to awareness and stigma may influence individuals’ actions to seek out needed care (Hickey, 2019). Examination of societal outcomes will generally focus on population-level effects, but may encompass any geographic locality that serves as the frame for the intervention of interest. Public awareness campaigns, for example, seek to promote understanding of dementia and foster a society that is inclusive and supportive of persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers. Some, like Ireland’s Understand Together campaign, may be focused broadly at raising awareness at the national level (Hickey, 2019), while others may aim to bring about change at the local community level (e.g., dementia-friendly communities) (Buckner et al., 2019). Persons living with dementia have played important roles in advancing societal-level interventions aimed at improving public awareness about the disease. These self-advocacy efforts, through such organizations as UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, are working to promote not only improved public understanding but also support among policy makers for dementia research and care-related policies (UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, 2020).

COMPLEXITY OF DEMENTIA CARE INTERVENTIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR ASSESSING THE EVIDENCE

The interactions and interdependencies among persons living with dementia, care partners and caregivers, the community, and the broader

policy and societal environments are complex. Heterogeneity in the populations, settings, care and support systems, and policy environments in which care interventions are implemented may lead to variation in the observed effects of those interventions. Such contextual effects can obscure signals of intervention effectiveness. As discussed below, this complexity poses challenges for the assessment of evidence supporting the readiness of interventions for broad dissemination and implementation.

Health service and public health interventions, such as nonpharmacological dementia care interventions, are often described as being complex interventions (Craig et al., 2008; Minary et al., 2018). They frequently involve multiple components that are constantly interacting with each other and with the context in which the intervention is taking place. While pharmacological interventions, such as medications to control type 2 diabetes, have their own complexities (Bolen et al., 2016), the interactions between health service and public health interventions and context are especially relevant in determining the complexity of an intervention. For example, a seemingly simple exercise intervention involves not only performing exercise but also interacting socially with a trainer and learning new skills, and it may occur in varied settings (e.g., home, gym, nursing home). These inherent interactions between intervention and context make it challenging to disentangle the effects caused by the intervention from those caused by the specific context in which the intervention is occurring (Minary et al., 2018). It is important to note that the goal of disentangling intervention effects from contextual effects is not achieved by separating the intervention from its context, but by understanding how various contexts affect the outcomes of the intervention. While context effects have posed challenges to systematic evidence review methods that focus on assessing the effectiveness of an intervention, realist review methods are designed to improve understanding of the intervention mechanisms that lead to outcomes of interest and the contexts in which those mechanisms function (Pawson et al., 2005).

Complexity Related to the Heterogeneity of the Disease and Populations Affected

As is true of the general population, persons living with dementia, care partners, and caregivers exhibit heterogeneity and represent a diverse range of genders, races, ethnicities, socioeconomic backgrounds, and marital statuses. It is also important to underscore that not all causes of dementias are the same. Persons with dementia may be diagnosed with one or more dementia-causing diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, or Lewy body dementia, and the onset of related symptoms may occur earlier or later in life.

Adding to the complexity of dementia is the degenerative, dynamic, and unpredictable nature of the disease. As the symptoms of dementia progress, the needs of persons living with dementia and of their care partners and caregivers evolve, and it can be difficult to anticipate how these needs will change (Whitlatch and Orsulic-Jeras, 2018). However, studies on dementia care interventions are inconsistent in reporting of the disease stage of the target population (Butler et al., 2020), complicating understanding of how specific interventions affect persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers in different stages of disease progression. The broad spectrum of needs along the progression of the disease for persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers needs to be considered in study designs, outcomes, and reporting of results.

Measuring the outcomes of dementia care interventions is critical for having a scientific approach to designing and delivering care, services, and supports for persons living with dementia, care partners, and caregivers. Medical outcomes for persons with cancer, osteoporosis, or heart disease can be captured through such measures as fewer deaths or fractures or less breathlessness and fatigue, or via biomarkers. Persons with these conditions also frequently have quality-of-life concerns, and these outcomes are more difficult to capture. Outcomes related to quality of life and meaning are even more difficult to capture for persons living with dementia. This is due in part to the cognitive impairments they experience, particularly during the later stages of disease, and in part to the inherent goal of dementia care, services, and supports—to help a person live well in the world, which, as described above, is a personal experience that varies for persons living with dementia, care partners, and caregivers. In measuring intervention outcomes, both the person with dementia and the care partner/caregiver could be asked about this outcome, but how should these perspectives be weighed, particularly during the severe stage of disease? And what measures should be used to capture what is most important to people? Summative measures of overall well-being are attractive because they are all encompassing, but they may miss the intended target of an intervention, such as mood. In contrast, such quantifiable measures as emergency room visits may miss the mark of what matters to a person. These issues are discussed further in Chapter 6.

Complexity of Dementia Care Interventions

As discussed earlier in this chapter, some interventions may have components that span multiple levels of the framework depicted in Figure 3-1. The need for tailoring of care interventions—whether cultural tailoring or tailoring to the unique circumstances of individuals and organizations—adds another layer of complexity. As discussed further in Chapter 6, such

tailoring is critical to ensuring that care interventions are accessible to and meet the needs of the full range of populations that are affected by dementia and, importantly, the individuals within those populations (Graham et al., 2006). At the same time, however, variability in implementation may also give rise to variation in outcomes.

Complexity Related to the Systems in Which Interventions Are Implemented

As noted, interventions are affected by the community, policy, and societal contexts in which they are implemented. For example, reimbursement policies can disincentivize care practitioners from spending time discussing the values, goals, and needs of persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers (NASEM, 2016), which may reduce the effectiveness of interventions targeting the individual level, and likely those dependent on tailoring in particular. Further complexity results from the myriad stakeholders involved in the implementation of interventions. An overview of the complex ecosystem of actors and programs that support dementia care interventions is presented in Box 3-1.

CONCLUSION

Interventions for persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers can be implemented at multiple levels, ranging from the individual to society. While this allows the needs of persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers to be addressed from various perspectives, the interactions among these levels can affect outcomes and introduce complexity into dementia care interventions. Also introducing complexity is the fact that persons living with dementia and care partners and caregivers are highly diverse, representing different ages, genders, races and ethnicities, sexual orientations and gender identities, and types and stages of dementia. Underpinning all of this complexity is that dementia care interventions are themselves often complex, involving myriad interconnected components that interact with each other and with the context and system in which they are implemented.

CONCLUSION: Dementia care interventions are complex as a result of the multiple levels at which they are implemented, interactions among those levels, the diversity of persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers, and the complexity of the interventions themselves. This complexity presents challenges to the evaluation of interventions, and limited the ability of the AHRQ systematic review to draw conclusions for many of the

interventions considered. To improve the ability to answer questions about which dementia care interventions work, for whom, and under what circumstances, future research and synthesis approaches need to account for these complexities in the design, implementation, and evaluation of interventions.

REFERENCES

AARP. 2020. AARP community challenge 2020 grantees. https://www.aarp.org/livablecommunities/community-challenge/info-2020/2020-grantees.html (accessed November 9, 2020).

ACL (Administration for Community Living). 2019. Support for people with dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. https://acl.gov/programs/support-people-alzheimers-disease/support-people-dementia-including-alzheimers-disease (accessed October 13, 2020).

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). n.d.-a. About the AHRQ health care innovations exchange. https://innovations.ahrq.gov/about-us (accessed November 9, 2020).

AHRQ. n.d.-b. Practice-based research networks: Research in everyday practice. https://pbrn.ahrq.gov (accessed November 9, 2020).

Alzheimer’s Association and CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2018. Healthy brain initiative, state and local public health partnerships to address dementia: The 2018–2023 road map. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association.

Alzheimer’s Association and CDC. 2019. Healthy brain initiative: Road map for Indian country. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association.

Bolen, S., E. Tseng, S. Hutfless, J. Segal, C. Suarez-Cuervo, Z. Berger, L. Wilson, Y. Chu, E. Iyoha, and N. Maruthur. 2016. Diabetes medications for adults with type 2 diabetes: An update. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Buckner, S., N. Darlington, M. Woodward, M. Buswell, E. Mathie, A. Arthur, L. Lafortune, A. Killett, A. Mayrhofer, J. Thurman, and C. Goodman. 2019. Dementia friendly communities in England: A scoping study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 34(8):1235–1243.

Butler, M., J. E. Gaugler, K. M. C. Talley, H. I. Abdi, P. J. Desai, S. Duval, M. L. Forte, V. A. Nelson, W. Ng, J. M. Ouellette, E. Ratner, J. Saha, T. Shippee, B. L. Wagner, T. J. Wilt, and L. Yeshi. 2020. Care interventions for people living with dementia and their caregivers. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 231. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. doi: 10.23970/AHRQEPCCER231.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2020. BOLD public health centers of excellence recipients. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/funding/phc/index.html (accessed October 13, 2020).

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). n.d.-a. Home & community-based services 1915(c). https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/home-community-based-services/home-community-based-services-authorities/home-community-based-services-1915c/index.html (accessed October 22, 2020).

CMS. n.d.-b. Improving care for Medicaid beneficiaries with complex care needs and high costs. https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-states/innovation-accelerator-program/program-areas/improving-care-for-medicaid-beneficiaries-complex-care-needs-and-high-costs/index.html (accessed October 13, 2020).

CMS. n.d.-c. Innovation models. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models#views=models (accessed October 13, 2020).

CMS. n.d.-d. Institutional long term care. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/long-term-services-supports/institutional-long-term-care/index.html (accessed October 22, 2020).

CMS. n.d.-e. Quality of care external quality review. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/medicaid-managed-care/quality-of-care-external-quality-review/index.html (accessed October 13, 2020).

CMS. n.d.-f. Special needs plans (SNP). https://www.medicare.gov/sign-up-change-plans/types-of-medicare-health-plans/special-needs-plans-snp (accessed October 13, 2020).

Craig, P., P. Dieppe, S. Macintyre, S. Michie, I. Nazareth, and M. Petticrew. 2008. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new medical research council guidance. BMJ 337:a1655.

Dementia Friendly America. 2018. About dementia friendly America. https://www.dfamerica.org/what-is-dfa (accessed October 21, 2020).

Evans, S. C. 2018. Ageism and dementia. In Contemporary perspectives on ageism, edited by L. Ayalon and C. Tesch-Römer. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. Pp. 263–275.

Graham, I. D., J. Logan, M. B. Harrison, S. E. Straus, J. Tetroe, W. Caswell, and N. Robinson. 2006. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 26(1):13–24.

Haeusermann, T. 2018. The dementia village: Between community and society. In Care in healthcare: Reflections on theory and practice, edited by F. Krause and J. Boldt. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. Pp. 135–167.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2019. National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease: 2019 update. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/262601/NatlPlan2019.pdf (accessed October 1, 2020).

HHS. 2020. Advisory council on Alzheimer’s research, care, and services. https://aspe.hhs.gov/advisory-council-alzheimers-research-care-and-services#:~:text=The%20Advisory%20Council%20consists%20of,dementias%20(AD%2FADRD) (accessed October 13, 2020).

Hickey, D. 2019. The impact of a national public awareness campaign on dementia knowledge and help-seeking intention in Ireland. European Journal of Public Health 29(4):234.

Minary, L., F. Alla, L. Cambon, J. Kivits, and L. Potvin. 2018. Addressing complexity in population health intervention research: The context/intervention interface. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 72(4):319.

Mittelman, M. S., S. H. Ferris, E. Shulman, G. Steinberg, and B. Levin. 1996. A family intervention to delay nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 276(21):1725–1731.

Mittelman, M. S., D. L. Roth, D. W. Coon, and W. E. Haley. 2004. Sustained benefit of supportive intervention for depressive symptoms in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Psychiatry 161(5):850–856.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Families caring for an aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NIA (National Institute on Aging). 2020. Summit virtual meeting series: 2020 National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers. https://www.nia.nih.gov/2020-dementia-care-summit#Registration (accessed September 1, 2020).

NIA. n.d. Alzheimer’s disease research centers. https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/adc (accessed October 13, 2020).

NIA IMPACT Collaboratory. n.d. Overview. https://impactcollaboratory.org/overview (accessed September 1, 2020).

NORC at the University of Chicago. 2016. Third annual report: HCIA disease-specific evaluation. Bethesda, MD: NORC at the University of Chicago.

NQF (National Quality Forum). 2014. Priority setting for healthcare performance measurement: Addressing performance measure gaps for dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. http://www.qualityforum.org/priority_setting_for_healthcare_performance_measurement_alzheimers_disease.aspx (accessed September 4, 2020).

Pawson, R., T. Greenhalgh, G. Harvey, and K. Walshe. 2005. Realist review—A new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10(Suppl 1):21–34.

The John A. Hartford Foundation. 2020. Recent grants. https://www.johnahartford.org/grants-strategy (accessed November 9, 2020).

UsAgainstAlzheimer’s. 2020. Activists against Alzheimer’s. https://www.usagainstalzheimers.org/networks/activists (accessed November 11, 2020).

VA (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs). 2020. Program of general caregiver support services (PGCSS). https://www.caregiver.va.gov/Care_Caregivers.asp (accessed September 29, 2020).

Whitlatch, C. J., and S. Orsulic-Jeras. 2018. Meeting the informational, educational, and psychosocial support needs of persons living with dementia and their family caregivers. Gerontologist 58(Suppl 1):S58–S73.

__________________