2

October 2020 Women in STEMM Faculty Survey on Work-Life Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic1

COVID-19 has prevented me from working face to face with students and colleagues, traveling for work, and working in the lab, all of which are critical to my work as an experimental astrophysicist.

– STEMM woman faculty member (rank unknown)

Because I work from home, I have to hole up in my bedroom for work meetings, and because my husband and I both work full time, jobs that require meetings with other people, we constantly have to switch back and forth between roles. I get an hour or two for some Zoom meetings, then it’s my turn to play kindergarten teacher for two hours, then I might get another hour or two to work. The constant task switching is mentally challenging and makes it hard to dive deep into any work task or accomplish anything that requires sustained attention for a longer period of time.... There are no boundaries between personal and professional life anymore. I really miss going to my office for many reasons, but being able to compartmentalize work and home ….is one of them.

– STEMM woman associate professor

___________________

1 This chapter is based on the commissioned paper “Boundaryless Work: The Impact of COVID-19 on Work-Life Boundary Management, Integration, and Gendered Divisions of Labor for Academic Women in STEMM,” by Ellen Ernst Kossek, Tammy D. Allen, Tracy L. Dumas.

INTRODUCTION

The biggest challenge the committee faced in trying to identify positive and negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on women in academic science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) for this report was the lack of data, which was not surprising given that the committee was engaged in its work as the COVID-19 pandemic was still raging. This chapter includes findings from a national faculty survey conducted in October 2020 to examine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on women STEMM academics and that was conducted to gather original and timely data on post-COVID-19 pandemic work-life boundary and domestic labor issues specific to women in STEMM.2 This survey asked women faculty in STEMM fields to compare how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected them between March 2020 and October 2020.

PREFERENCES AND CHANGES IN NUMBER OF DAYS WORKING AT HOME

The survey asked respondents to indicate their preferred and actual number of days working at home or on campus, both pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless of family or personal demographics, tenure status, rank, or caregiving responsibilities, women faculty reported working at home an average of 3.9 days compared with 0.66 days before the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, the preferred number of days working at home was significantly lower than the current number of days working at home, across all respondents.

Women faculty with children reported spending more time working at home than faculty without children at home.3 Although women faculty with childcare responsibilities worked at home significantly less than their counterparts before the COVID-19 pandemic, they worked at home significantly more than their counterparts without children once the COVID-19 pandemic began. For many working parents, this was more often than they preferred.

Changes in Boundary Control

Boundary control, defined as the ability to control the permeability and flexibility in time, location, and workload between work and nonwork roles to align with identities (Kossek et al., 2012), is linked to important outcomes, such as work-family conflict and job turnover (work-life boundaries are covered more

___________________

2 Details about the survey methodology are available in Appendix A.

3 While the vast majority of institutions closed in-person operations due to state or local mandates at some point during 2020, the designation of faculty as “essential workers,” requirements for remote work, and both online teaching and in-person teaching expectations varied, as did the duration of the closures.

fully in Chapter 4). Across the sample of women STEMM faculty, all reported significantly lower levels of boundary control after the COVID-19 pandemic began than before, and women faculty with childcare responsibilities reported significantly lower levels of boundary control during the COVID-19 pandemic than their women counterparts without children, including those with eldercare responsibilities.4

Survey respondents echoed these quantitative changes in their comments collected as part of the qualitative portion of the survey. Some 25 percent of the respondents wrote about experiencing a lack of boundary control when it came to preventing interruptions, particularly when scheduling teaching or managing virtual videoconference meetings. One example of this related to the inability to control family boundaries interrupting work demands during synchronous teaching. As a full professor, married with children, bemoaned, “… my son had a meltdown 5 minutes before my Zoom class was supposed to start.” Another example of difficulties in managing boundary control involved trying to work and multitask while caring for children, which women ended up doing more often than their men spouses. One associate faculty member stated the following:

I teach synchronously via Zoom. My husband is home and does the same thing. He and I have some classes that overlap, which means that I must frequently teach with my daughter in the room with me. She’s too young to understand how much I need her to play independently during class time, and I have lost a lot of a sense of professionalism with my students, because they see me getting constantly interrupted with comments like “Mommy, I went poop!!”

Changes in Blurring of Work-Life Boundaries

Slightly more than half of the respondents mentioned having problems managing boundaries between work and personal life since the COVID-19 pandemic began. More than one-third of total respondents reported they were experiencing high boundary permeability as mentally and cognitively stressful to regulate.5 Examples included the following:

- Blurred boundaries between work and family roles. For example, an assistant professor who is married and managing childcare comments, “They are happening simultaneously. I am working, and I am caring for my

___________________

4 Details about the analysis used for the survey results are available in Appendix A.

5 For an example mirroring this issue in academic medicine, see: Strong et al. (2013).

- 1-year-old. I am answering emails while making dinner. I am recording lectures while he naps. There are no boundaries, as everything happens at the same time and in the same space.”

- A lack of time buffers between role transitions. For example, a married assistant professor without children stated, “Working from home, I log in and start looking at emails and responding to questions soon after waking up. The personal time that was earlier needed to get ready and commute to work provided the much-needed buffer between work and daily activities.”

- Difficulties detaching from work when working at home. For example, an assistant married professor without care demands noted, “I’m always at home. Everything occurs at home. It’s harder to turn off at the end of the day because there is no longer an end of the day.”

- Limited space to create physical boundaries, including space for a separate office. For example, an assistant married professor with no children stated, “I don’t have a closed office at home, since we can’t afford a place that large. My husband has to work from home even without the pandemic, so he gets the one spare room. This means I have more distractions, kitchen noise, road noise, and a spouse who keeps walking into my ‘office’ at all hours. It is manageable, but psychologically is harder for me to keep the lines blurred, especially since I am just in my living room.”

EFFECTS OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC ON WORK PRODUCTIVITY, WELL-BEING, CHILDCARE AND HOUSEHOLD LABOR, AND ELDERCARE

Effects on Work Productivity

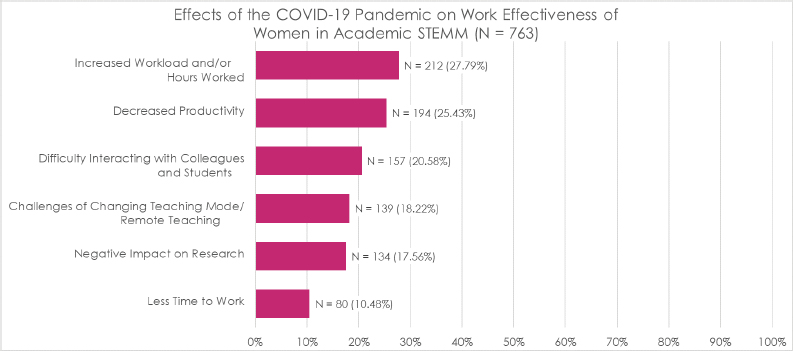

The survey asked respondents how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected their personal and professional work outcomes, with the results summarized in Figure 2-1. Almost three-quarters of the participants mentioned the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their work. The most commonly mentioned top negative effects were the following:

- Increased workload resulting from more meetings, longer hours, more emails, and need for extended availability (27 percent). As one partnered faculty member without children commented, “I feel like my workload has increased by 50 percent. I’m not able to keep up. I am worn out and tired of having to constantly apologize for being late.”

- Decreased work effectiveness (25 percent), with examples including decreased productivity, decreased efficiency, always being behind schedule, having tasks take much longer, and finding it hard to focus.

- Poorer social interactions with peers and students (20 percent).

- Adverse effects on teaching and research (20 percent).

Other concerns were not having enough time to work and decreasing resources and support, such as pay cuts, furloughs, worries about research funding, and tenure outcomes and delays. (These topics are covered more fully in Chapter 3.)

Effects on Personal Well-being

Two-thirds of the respondents reported a negative impact on personal wellbeing, and 25 percent reported a decline in psychological well-being, regardless of rank and personal demographics. A married full professor with no children commented, “[I have] enormous stress—from work, family, trying to figure out how to work remotely… coping with an ever-changing array of rules, protocols, scenarios, problems.” Similarly an assistant professor who is living with a partner stated, “There’s a major increase in stress and anxiety as I feel like I’m working more/harder and accomplish[ing] less. This stress has taken a serious toll on my personal well-being.” More than 6 percent of the respondents said the COVID-19 pandemic was causing a lack of sleep. One assistant professor with children described being “constantly stressed that the lack of lab productivity will cause me to not get tenure. I lose sleep over it.” (See Chapter 7 for more information on these topics.)

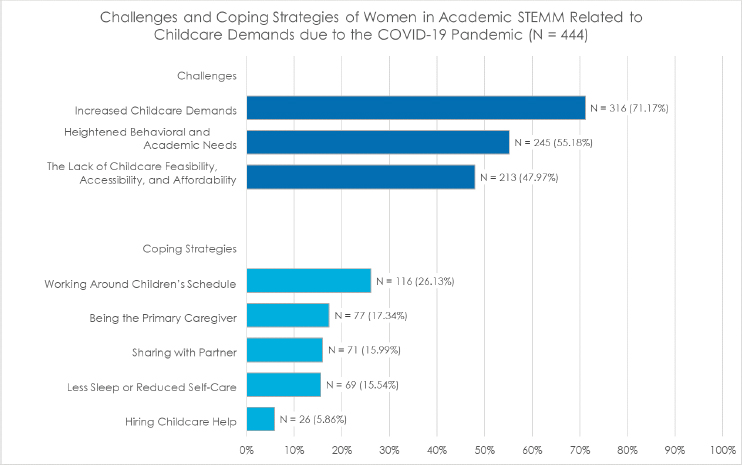

Effects on Childcare

Figure 2-2 summarizes the challenges and coping strategies related to childcare demands reported in the survey. Nearly three-fourths of responding faculty with children reported a negative effect from increased childcare demands. A key reason for this is that 90 percent of women faculty were handling a majority of school and childcare demands. Only 9 percent of women reported that they shared childcare demands equally with their spouse, and only 3 percent said they had help from a babysitter, nanny, or tutor during the COVID-19 pandemic. Approximately 10 percent of the sample reported being the primary caregiver for children in their homes even if they were married to another professional. The effects of the pandemic were not all negative, as approximately 13 percent of the women respondents mentioned positive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on family life, such as enjoying more family time together, ease in managing work-family demands, not having to dress for work, and a shorter commute.

Childcare Feasibility, Accessibility, and Affordability

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, many respondents reported avoiding outside childcare because they were concerned about viral spread in childcare facilities. Some faculty reported an increased financial burden resulting from childcare needs, and some women reported they continued to pay for spots in childcare centers to prevent from losing their spaces while shouldering home schooling and childcare responsibilities themselves. A married assistant professor with young children shared the following:

We are trying to stay in our bubble, so we don’t have any childcare for our two kids. We don’t want to bring in babysitters or have day care unless absolutely necessary. But this means the kids are with us all the time except about 10 hours of in-person school a week.

Those who desired to use outside childcare reported difficulty finding it. Examples from the survey include the following:

This is bonkers. I cannot find childcare for my youngest (three years old) and my older two children are remote learning for kindergarten and second grade. Babysitters/nannies in this area have raised their prices and now the starting rate is $20/hour and for three kids with remote learning duties have been offering $30-40/hour and still have not found someone to help. So since March, my husband and I have been simultaneously performing parenting full time and working full time. It is fundamentally exhausting.

– Associate professor, married with children

My husband and I are both pre-tenure faculty and we have two young children at home. We are both trying to maintain jobs that want to demand 150 percent of our time when we are having to split shifts (two hours in the home office then swap and two hours with the kids).

– Assistant professor

My husband and I both work full time jobs, remotely. We live in an 800-square-foot apartment in XXX. My 5-year-old is doing blended learning. We have to maintain our jobs and step in as kindergarten teachers (for a kid who absolutely does not want to do remote school work). There is so much more work to do to care for our kids (we lost our hired caregiver when the pandemic started) and only one adult can do work for their paid job at a time because the other has to watch our kids. In the spring, when this started, I had to stay up working very late into the night every single night to just barely keep my head above water and stay on top of my work.

– Associate professor

Home Schooling and Increased Household Labor Stress

More than 41 percent of the respondents reported that home schooling increased their workload and stress. More than one-third of the entire sample, regardless of caregiving demands or relationship status, reported strain from increased cooking, cleaning, and other domestic demands. One associate professor described the following:

I am on the verge of a breakdown. I have three children doing virtual schooling full-time who need my attention throughout the day; they all have different break schedules and seemingly interrupt me every 10 minutes. I want them to learn and thrive and I try to make these difficult circumstances for them as positive as possible, which means giving more of myself and my time to them. I try to wake up before them and work after they sleep, but this is hard given they wake up at 7 AM for school and don’t go to bed early (they are 13, 11, and 8). There are sports/activities, dinner, homework/reading, etc. All the things that keep my evenings busy when they were in school, but now it is all day.

Children’s Heightened Behavioral and Academic Needs and Relational Strain

Some respondents indicated that their children across all ages, even into high school, were not adjusting well to remote learning and the disruption to their regular schedules. Therefore, some children needed more academic assistance from their parents and others acted out, further disrupting the faculty members’ ability to work. These challenges also put a strain on relations between children and parents, and children and spouses in the household.

As a professional engineer working in academia, and single mother of three girls, the pandemic has radically changed everything. Although I spend more time with my girls, their mental health has deteriorated significantly with online school and very minimal contact with friends. Our social bubble with one other family (kids same age and gender) has been the only outlet. Even if there were enough hours in the day, I simply do not have the mental bandwidth to be a full time homeschooling mom, housekeeper, instructor, researcher, and family member (maintaining my family relationships from a distance—parents, sister, etc.).

– Associate professor, single with children

Being able to focus, and constantly shifting schedules to deal with kids and my husband’s job. My 7-year-old is struggling with being home all the time and having a baby at home. So on top of the scheduling challenges, she is having way more behavioral problems than normal, which makes it even harder to work.

– Assistant professor, married with young children

On the negative side, I have children in school attempting to do virtual learning; this has been very difficult to manage while still trying to work myself. I have had to spend anywhere between one and three hours per day managing their virtual school activities. My husband does not feel as obligated and does not perform these tasks related to checking their schoolwork. I have lost sleep trying to make up for these lost working hours after the kids are in bed.

– Assistant professor, married with children

My son, although fairly independent as a high school student, is not adjusting well to virtual learning. His grades do not at all indicate his understanding of the content of his classes. He is finding it difficult to understand what the teachers are looking for through his virtual interactions with them. This has produced the need for frequent difficult family conversations that did not exist pre-COVID.

– Full professor, married with children

I also feel like I’m being put in the role of a mean mommy telling them they have to work extra at the end of the school day because they didn’t get their work done during the day. I know that if they were physically in the classroom, the teachers would see them not being focused and the teachers could be the one encouraging them to work more efficiently. I guess I’m concerned about how online schooling is impacting my relationship with my kids.

– Associate professor, married with children

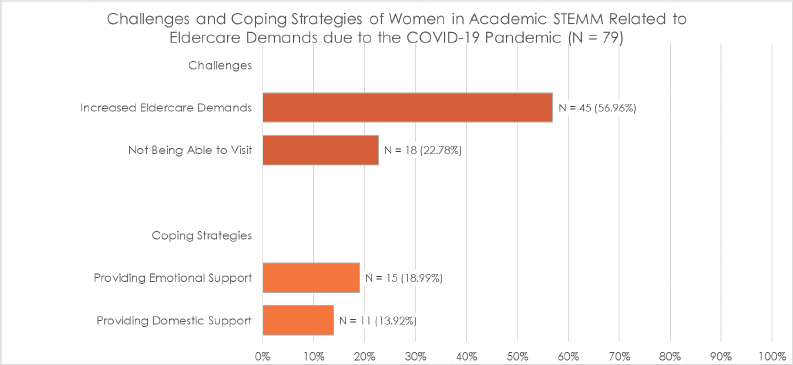

Eldercare and Sandwiched Care

Some 56 percent of the respondents reported increased eldercare demands, and nearly a quarter of those with elderly relatives reported increased stress from not being able to visit them. Figure 2-3 provides a summary of the challenges and coping strategies related to eldercare demands reported in the survey. Responses generally reflected three issues: demands associated with moving the family member from their initial care facility either to another facility or to have their parents move in with them to avoid exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic; the need to provide increased domestic support, such as household cleaning or ordering groceries, to minimize their elder’s risks to the COVID-19 pandemic or the loss of paid support to provide eldercare; and concern over distance from the family member for the family member’s well-being. As one married assistant professor with both childcare and eldercare (“sandwiched care”) responsibilities noted, “I need to shop, cook, and provide all support for healthcare visits for both parents, one who died unexpectedly in July and has left us grieving on top of all this. Now mom is at home alone and needs more support and love in the middle of all this.”

Another associate professor faculty member noted she was constantly

stressed by the “inability to be able to fly back home to take care of [her parent] (or if bad things happened later). The anxiety of being stuck far away and not even knowing if I can attend the funeral on time is too high.” A full professor who is unmarried reported that her parents are also exhibiting increased stress, resulting from “cancelled doctor appointments, more difficulty getting them care, multiple hospitalizations, move to facility, no visitation at facility, more mood disorder, isolation, unable to get services to home due to fear of COVID.”

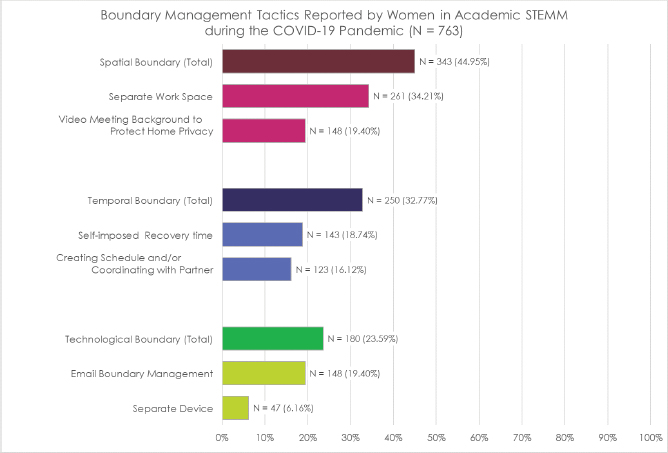

COPING STRATEGIES FOR BLURRED BOUNDARIES AND DOMESTIC LABOR

Many faculty actively used separation tactics to manage the boundary between work and home. Figure 2-4 summarizes boundary management tactics and other coping strategies that survey respondents have adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic. The most popular separation tactic involved the use of technology to hide the home space during videoconferencing, whereby faculty set up video meeting backgrounds to protect home privacy. The second most common separation strategy was having a separate office at home if space permits, such as turning a dining room into a designated office or setting up a computer in a guest room. However, some faculty respondents did not have a space that was conducive for work and sometimes needed to manage boundaries with family in ways children may not fully understand. A married assistant professor with young children shared the following:

I have a workspace set up in my walk-in closet, and I purchased a folding screen to put behind me so others can’t see my dirty laundry or items all over the floor. I’ll shut the door to the closet so the cats and kids stay out when I’m “at work.” But if I need an extra level, the closet door leads into the bathroom so I’ll close the bathroom door, which has a lock on it for extra assurance. However, my 5-year-old has figured out how to stick a bobby pin into the knob to pop the lock open when she’s desperate.

Respondents also used email boundary management as a means of limiting availability for work communications during nonwork times, with some faculty members physically removing or turning off work emails from their smartphones. Other respondents used one device for work and another for personal use. Some of these physical technology boundaries were combined with spatial boundaries.

Individual Temporal Strategies to Manage Working Time

Since most academic institutions did not have any policies or approaches in place to create a culture that helps faculty avoid overworking, many faculty had to self-regulate and triage new ways of coping with managing work and nonwork

boundaries on their own, given their workload increased exponentially. Those with children in particular had to self-manage and engage in significant time restructuring to manage their heavier workload with childcare. The most common coping strategy, particularly for those with children, was working outside of standard hours and around children’s schedules, which resulted in extended availability to work and long hours. Some respondents reported getting up early in the morning and working late at night when children were sleeping, and to a lesser degree, just sleeping less. As one associate professor with children commented, she and her spouse now “go ‘back to work’ after the children are in bed and it is still not enough time to keep on top of everything.” Another assistant professor with children commented on the demands of juggling childcare/e-learning: “I can’t get work done productively during the day, so work bleeds over until late evening. Regularly work from 9-midnight and start at 3 AM now.”

Another temporal strategy for those with children involved setting up a coordinated work schedule with a partner, with periods of integration and separation to cover shared caregiving. Others organized their household with shared calendars with a spouse, if married, or blocked out time from work to take care of their children’s schooling needs. An assistant professor with children commented:

My children have one remote learning day a week in their K–12 public school. I blocked off this time on my work calendar as a private appointment. I wanted to keep this time free to be available to help my children. As they settle into their remote learning routine, I find that I can work next to them. I am so glad I thought ahead to block off this time so that I am not torn between sitting with my children or being in another room occupied with a video meeting.

Some faculty set aside weekends to take off from work and allow for recovery, though enforcing this break was not always easy to accomplish.

Reducing Time Allocated for Self-Care

Given limited time, many faculty are putting their family’s well-being ahead of their own. Many mentioned they have no time for themselves, as well as a lack of social support. While some respondents did mention self-care strategies such as taking walks, exercising, and meditating, many reported unhealthy strategies. As one married assistant professor with children explained, “I have had to reduce my sleep to a bare minimum (2–3 hours), forgo exercise or time to myself, and endure significant stress and anxiety.”

ACTUAL VERSUS DESIRED UNIVERSITY ACCOMMODATIONS POST-COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Faculty respondents reported three main ways that academic institutions helped manage challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic:

- Giving faculty the option to work remotely.

- Extending the tenure clock.

- Allowing faculty to choose their preferred mode of teaching, whether online, remote, hybrid, or face-to-face.6

Given the sudden, unprecedented onset of COVID-19 pandemic challenges, some faculty reported that their academic institutions focused on testing and health issues (McAuliff et al., 2020) but did not have a plan or clear policies in place to help faculty working remotely. For example, at some institutions there was no infrastructure for childcare, school for children, or ways to continue research or reduce teaching demands. Switching to online instruction dramatically increased faculty members’ workload. For example, faculty members needed to learn new technologies and redesign entire classes for remote learning almost overnight, something that is likely to change higher education for decades (Alexander, 2020). Furthermore, because of variance in student internet access and schedule control from home, faculty needed to deliver content both synchronously and asynchronously, resulting in the need for additional measures, such as recording lectures and remaining available for student interaction outside of normal class time or office hours (Alexander, 2020).

Lack of Caregiving and School Support

When asked how their academic institutions could improve in their handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, some faculty stated their academic institutions could have done a much better job of providing childcare, help with their children’s schooling, and financial support. Though these were the supports faculty wanted, few academic institutions provided them. Instead, most academic institutions took a hands-off approach. An assistant professor with children stated the following:

Many faculty were expected to manage childcare demands by themselves. We were told to have backup childcare this semester in case schools closed (they are virtual part time), but they haven’t offered any options or financial support for this in a town where daycares already had a >12 month waiting list pre-COVID, and they stopped allowing kids on campus.

___________________

6 Although some academic institutions did not give faculty members any choice in teaching mode, many provided options for faculty who are in higher-risk brackets for COVID-19 to teach remotely or in person as well as resources for faculty who need to teach from home.

Moreover, the underinvestment of some academic institutions in childcare support became more apparent when the COVID-19 pandemic began. As one faculty member with children commented,

Our on-campus childcare situation is terrible, too little capacity and historically not high-quality care. With the onset of the pandemic, it was closed and some schools at the university stepped up and provided additional childcare subsidies to families who needed them, but it was not centralized or universal across the university. HR is now being entirely restructured so perhaps it will end up being more comprehensive, inclusive, and proactive. There is in general an utter lack of proactive care of people’s needs.

Finally, a handful of faculty commented that their academic institutions were not culturally supportive of family life. As one faculty member stated, “My university does not care about families. They don’t even mention issues with childcare in messaging and blamed the lack of affordable childcare on ‘community partners.’ It has always been a problem here, which is probably why we have so few women as professors.” Such comments suggest that maybe the COVID-19 pandemic could be a catalyst for institutions to reinvest in new solutions to foster gender equality (Malisch et al., 2020).

Workload Reduction

One suggestion raised by a few respondents was to reduce teaching and service demands for those with childcare and eldercare responsibilities, and to modify research expectations for tenure, given the COVID-19 pandemic. A number of respondents stated that they did not feel that a tenure clock extension was an effective means of reducing workload during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather, those respondents noted that what they needed was an acknowledgment that these years will result in much lower productivity.

HIGHLIGHTS FROM NON-TENURE-TRACK FACULTY RESPONSES

Although the intent of the survey was to focus on tenure-track faculty members whose research was largely stopped by the COVID-19 pandemic, there were some insights gained from the responses of non-tenure-track faculty who are also facing difficult career challenges. Most of these faculty members were lecturers and clinical professors who bore the burden of heavy course revision to a virtual format.

Negative Work Effects on Non-Tenure-Track Women Faculty in STEMM

Similar to the women faculty who are tenured or on the tenure track, about three-fourths of non-tenure-track faculty mentioned the negative effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on their work productivity. The top two most mentioned negative impacts on work productivity were increased workload and decreased work effectiveness, which were similar to the same top concerns of tenure-track and tenured faculty. While the academic tenured and tenure-track faculty’s third most common concern was on the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on social interactions with peers and students, for non-tenure-track faculty the third most common concern mentioned was a negative effect on teaching. Key concerns included a large increase in workload and stress resulting from technology problems, having to offer multiple formats to students, developing new content, and a lack of clear directions from administrators on decisions that could help planning. The following are three sample illustrative comments highlighting these issues:

I feel like I am not as effective at instructing students as I was pre-pandemic or even during the quarantine period of the pandemic. Currently, with offering flexible solutions for students, I am pulled in too many directions and spend 2–3 times the amount of prep time on lectures and materials. Trying to deliver content to students in class AND online has been a tremendous challenge and I feel like I waste about 20 minutes out of every 75-minute lecture just trying to get the technology to work properly. I’m working at least 12 hours a day either developing materials for both types of instruction or trying to get caught up on grading assignments and providing adequate feedback to students. Even my weekends are now rarely my own, since this is the only time I can record content for some of my courses.

– Senior instructor, married with children

Added much more STRESS to life. Working more hours at home than I would ordinarily put into my day when I went to campus. Had to learn technology quickly and by myself for the most part (adult children were helpful, too). Spring I tried asynchronous instruction which was a LOT of work and students were not pleased at all. Changed to synchronous instruction in summer and currently and overall a much more pleasant and satisfying solution to the problem. Had to figure out on-line labs in spring which was a total disaster and most unsatisfactory for both me and the students. As a program, we did not offer labs in summer until we were able to meet face to face beginning in July. Labs are face to face this fall so only issues are that some students are quarantined and miss at least two labs minimum, and yet must be counted as “excused.”

– Senior lecturer, married without caregiving responsibilities

Early in the pandemic (March and April), there was so much communication (much of it contradictory) from department, college, and university level admin that we were jerked every which way almost every day. Admin seemed to think you could totally redesign your course on a dime in the middle of the semester, and sent us ads from third-party vendors, as well as constantly changing policy edicts and requests for information. This pushed me to work 10–12 hours per day, seven days per week, and resulted also in very unhappy students. The stress was unbearable, and by June I was in ICU with a stroke. Thankfully I have recovered sufficiently to keep working. But I fault the university for the amount of stress they caused.

– Anonymous, married with eldercare

Less than 5 percent of women faculty who are not on the tenure track mentioned worrying about job security because their job is dependent on contract renewal or funding. Examples of the concerns that were expressed included the following:

Our institution is facing mandatory 10 percent budget reductions. I am in a vulnerable position as a nontenured academic lecturer (despite 25+ years’ experience at this institution, women faculty member in STEM field). So, who knows? I try to be grateful I have a job, a job I enjoy, and I am healthy.

– Senior lecturer, married without caregiving responsibilities

There is no guarantee whether I can have a postdoc in the next six months because it all depends on my supervisor and the funding agency. There is no fallback in these times of pandemic.

– Postdoc, married with children

Non-Tenure-Track Faculty Desired University COVID-19 Pandemic Organizational Supports

In general, the views of tenure-track and non-tenure-track faculty were similar regarding how academic institutions were helping women faculty manage challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and how their academic institutions could improve. However, non-tenure-track women faculty noted that some of the accommodations their academic institutions are offering, such as extending the tenure clock, simply did not apply to them because of their employment status.

I’m not feeling my institution is encouraging work-life integration as a whole. My immediate supervisor is very supportive of my decision to work exclusively from home. A few “atta-boys” are tossed by the Provost to thank faculty for their flexibility with coping with challenging times, but no real differences implemented EXCEPT allowance to take 2 personal days this

semester. That’s nice BUT the semester is already one week longer than in the past. And, if you teach every day, which day am I to take off??

– Senior lecturer, married without caregiving responsibilities

In reality, the flexible work schedules, reduced schedules, job-sharing and alternate work duties options they offer simply do not apply to teaching faculty, especially those that rely on their income to support their family.

– Assistant professor of practice, married without caregiving responsibilities

While there was no consensus on the further practices academic institutions could adopt to help non-tenure-track faculty beyond the same workload reduction and childcare recommendations that some tenure-track faculty wanted, it appears that extra teaching support for grading and technology support for converting courses to virtual formats might allow non-tenure-track faculty to have respite from their higher teaching loads.

CONCLUSIONS

Between March and November 2020, there was little guidance regarding institutional policies—both structural and cultural—that indicated what will be most helpful (see Chapter 6 for more on this topic). Tenure clock extensions were widely implemented as policies to address the COVID-19 pandemic productivity challenges (see Chapter 3 for more on this topic). However, these policies were implemented without addressing the disparities in increased caregiving and job-related workload that women faculty across all ranks and job status are facing. Previous research reported that gender-neutral tenure clock stop policies reduce women’s tenure rates while increasing men’s tenure rates (Antecol et al., 2018). For tenure-track faculty, this means that tenure clock extensions may not have a positive effect on women’s careers, and may have an adverse effect on women’s tenure achievement and the retention of women faculty. Based on the findings of the survey, it is clear that some faculty believe that tenure clock extensions alone will not be sufficient to help pre-tenure faculty manage the negative career effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This survey aligns with others that have been conducted during 2020. For example, in a survey of 608 scientists, approximately one-third of nontenured assistant professors were dissatisfied with their work-life balance during COVID-19, while 26.5 percent of associate professors and 10.8 percent of full-time professors expressed dissatisfaction (Aubry et al., 2020; Wallheimer, 2020). Two-thirds of respondents believed that temporarily stopping the tenure and promotion clock would be helpful (Aubry et al., 2020; Wallheimer, 2020).

The survey results presented here also highlighted how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting multiple aspects of employees’ lives, including outcomes related to personal well-being and those of their children and partners. Showing

organizations and teams how to respect others’ management of work-life boundaries (see Chapter 4) and to preserve others’ needs for boundary control may help prevent burnout. While the mental health of most employees has been taxed during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is affecting women disproportionately compared to men (see Chapter 7). Work support interventions, such as greater administrative help in managing the added demands associated with learning new technology platforms for online teaching, are critical in reducing stress. These types of interventions may dovetail well with family support interventions that help faculty with managing schooling and childcare demands.