Proceedings of a Workshop

INTRODUCTION1

Advance care planning (ACP) has long been a staple of caring for people with serious illness. Over its long history, it has been defined in different ways. A recent Delphi2 panel offered a consensus definition of ACP as “[a] process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care” (Sudore et al., 2017). Even this definition, however, was written with the expectation that it would evolve over time to fully capture the complexity of ACP.

ACP is designed to prepare people for unexpected events, be it a medical emergency or an acute, chronic, or terminal illness. The hope is that ACP can contribute to improved quality of life by relieving unnecessary suffering, and by clarifying the complex and often complicated decisions that need to be made by the individual and their caregivers. ACP also aims to ease

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants, and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

2 The Delphi method is a process used to arrive at a group opinion or decision by surveying a panel of experts.

the burden of decision making on the part of family members should the individual become unable to make decisions for themself (Sudore and Fried, 2010), as well as lessen moral distress among health care providers (Elpern et al., 2005; Ulrich and Grady, 2019).

Clinicians, researchers, patients, and the public have developed a variety of perspectives about the many aspects of ACP, ranging from the definition to the timing, goals, outcomes, and value of ACP. Moreover, despite significant efforts over the past three decades to raise visibility and promote completing an advance directive,3 one component of ACP, less than 40 percent of Americans—including adults with chronic illnesses—have done so (Rao et al., 2014; Yadav et al., 2017).

To better understand the challenges and opportunities for ACP, acknowledge and highlight divergent viewpoints, and examine what is empirically known and not known about ACP and its outcomes, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Roundtable on Quality Care for People with Serious Illness hosted a virtual public workshop, Advance Care Planning: Challenges and Opportunities, on October 26 and November 2, 2020. The workshop explored the paradox of ACP, its evidence base, ways to think differently about ACP, and various approaches to making it more effective.

This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the presentations and discussions from that workshop. The speakers, panelists, and workshop participants presented a broad range of views and ideas, and Box 1 provides a summary of individual participants’ suggestions for potential actions. Appendixes A and B contain the workshop’s Statement of Task and agenda, respectively. The speakers’ presentations have been archived online (as PDF and video files).4

OPENING REMARKS

James Tulsky from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School opened the workshop, explaining that roundtable members had wondered whether there was

___________________

3 An advance directive is a written statement of a person’s wishes regarding medical treatment, often including a living will, which is made to ensure those wishes are carried out should the person be unable to communicate them.

4 For more information, see https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/advance-care-planning-challenges-and-opportunities-a-workshop (accessed December 9, 2020).

anything new to say about ACP given that it is one of the most thoroughly researched areas in serious illness care. “As we were discussing this,” said Tulsky, “what became very clear was that this was in fact an area of intense controversy, where there were many different opinions about the value of ACP, in what situations ACP would be most effective, what the definition should be, and the key questions that needed to get answered.”

Tulsky also noted that the controversy related to ACP has been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic. “So many of us have unfortunately seen patients who have had to make decisions about life-sustaining treatments, oftentimes with little advance notice, and this has heightened concern about the need for advance care planning,” he said.

In his opening comments, Robert Arnold from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center predicted that vigorous differences of opinion would come to light during the course of the two webinars. While the

notion of patient-centered care is something that all of the webinar participants care about and spend their time working toward, Arnold said, the question is whether and how ACP helps us or distracts us from achieving that goal. Throughout this workshop, “you will get a sense of where the disagreement lies and be able to come to your own conclusions about what the next steps should be,” concluded Arnold.

THE PARADOX OF ADVANCE CARE PLANNING

Lived Experiences with Advance Care Planning

The first session of the workshop opened with Maureen Stuart and Wyvonia Woods Harris, both volunteers with the National Patient Advocate Foundation (NPAF), sharing their lived experiences of caring for

someone with serious illness. They spoke of the complexity of communicating with and about a family member’s preferences and values, and ensuring that a loved one’s wishes are followed at the end of life. Speaking first, Stuart recounted her father’s last days fighting advanced prostate cancer. When diagnosed, her father was adamant that he did not want to die in a hospital. However, her father did not want to discuss his other preferences or wishes for end-of-life care with any of his children, nor did he want to complete an advance directive. Stuart explained that her father’s oncologist tried to communicate with his primary care doctor about preferences for end-of-life care, but it became clear that the choices were to go to a hospital or rely on the family to provide care, because palliative care and hospice services were not accessible where he lived in rural northern California. As her father’s cancer steadily advanced, his oncologist informed him of the Death with Dignity Act5 and encouraged him to decide if he wanted to start the process before he became cognitively impaired. Stuart’s father told her, but not his other daughter or his son, that he wanted to take advantage of that option, which was available to him because his oncology care took place in Oregon. Stuart pointed out that it was only then that her father acknowledged that his cancer was terminal.

Stuart explained that her father asked her to keep his decision a secret because he believed that the rest of the family would not support his decision. Stuart said her father did not express or document any other desires, except to die in his own bed at home and to have his family present, which left decisions about infection control, hydration, and other clinical choices to her. His death was quick and painful, and it did not allow for a lot of time for conversations about his goals of care. “I thought I knew what he probably wanted,” said Stuart, but she added that the gap he left regarding his specific wishes left her second-guessing her choices even 4 years after his death.

When asked what might have helped her during that time, Stuart said that while his oncology team provided wonderful care, there was no follow-up by a case manager or clergy member after the family was told that there was “probably nothing else” that the clinical care team could do for their father. As a result, the family was left to its own devices. “I think if we had been bolstered or had access to some mental health providers or a case manager, that probably would have helped tremendously,” said Stuart.

___________________

5 For more information, see https://www.deathwithdignity.org (accessed December 9, 2020).

Harris then spoke about her husband’s journey with chronic illness, which began when he was diagnosed with hypertension at age 34. At age 40, he developed Crohn’s disease, for which he had several surgeries. He then had kidney problems, developed polymyositis (an inflammatory disease that causes muscle weakness affecting both sides of the body), and needed his gallbladder removed. In 2017, while hospitalized as a result of complications from kidney disease, he developed pulmonary edema6 and suffered a heart attack. Over the next 2 years, he was on dialysis and had both legs amputated.

When Harris and her family had started preparing advance directives, her husband had indicated that he did not want any “heroic measures.” However, those plans were interrupted when her husband needed surgery to repair an intestinal blockage and he expressed a desire to live despite his precarious medical condition. Harris described how although her husband’s primary care physician was aware of his wishes as expressed in his advance directive, that knowledge was lost when a hospitalist took over his care. The lack of a written plan at the hospital proved to be a significant issue at a subsequent time when her husband needed emergency surgery late at night and the surgeon, from another hospital, knew nothing about him and his treatment preferences. She further described how her husband’s preferences had changed again, and she had to tell the new clinicians not to intubate him when he coded following the emergency surgery. Harris emphasized that emergency departments (EDs) and intensive care units (ICUs) are not good places to start the ACP process. Reflecting back on that experience, Harris suggested that everyone not only have an advance care plan, but also scan it into their phones so as to have it readily available whenever needed.

An Ethical Framework: From Advance Directives to Advance Care Planning

Bernard Lo, president emeritus of The Greenwall Foundation, began by describing how on a winter day in 1983, Nancy Cruzan skidded off a Missouri highway, and suffered a serious brain injury when her car crashed. Though resuscitated, Cruzan never regained consciousness and was in a persistent vegetative state. After 3 years, her parents realized there was no hope that she would regain consciousness, and they asked to have her feed-

___________________

6 Pulmonary edema is a condition caused by excess fluid in the lungs.

ing tube removed. Lo explained that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Missouri could only do so if she had executed a signed, legal document or made an oral statement rejecting that specific intervention in that situation. The Court ruled, for example, that the oral statements Cruzan had made to her parents indicating that she “did not want to live as a vegetable” were not sufficient (U.S. Supreme Court, 1990).

Lo explained that the ruling led to a national focus on advance directives, and many states passed laws authorizing an individual to appoint a health care proxy. In 1990, Congress passed the Patient Self-Determination Act,7 which required hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, home health agencies, hospice programs, and health maintenance organizations to (1) inform patients of their rights under state law to make decisions concerning their medical care; (2) periodically inquire as to whether a patient has executed an advance directive and document the patient’s wishes regarding their medical care; (3) not discriminate against persons who have executed an advance directive; (4) ensure that legally valid advance directives and documented medical care wishes are implemented to the extent permitted by state law; and (5) provide educational programs for staff, patients, and the community on ethical issues concerning patient self-determination and advance directives. At the time, this case triggered the idea that everyone, even young, healthy individuals, should complete an advance directive, though Lo noted that this thinking may have changed in the subsequent years.

Written advance directives or specific oral statements have their limitations, said Lo, particularly because no one can anticipate the actual clinical situations and decisions that will arise. For example, he had a patient who said she never wanted to go to the hospital, but when she broke her hip and was in terrible pain, she had to reconsider that wish if she wanted her pain adequately relieved. In addition, an individual may realize that these decisions are complicated and want to give the family leeway to consider not what the individual would have wanted, but rather what the best decision is in the current situation, said Lo.

Lo noted that the focus on specific directives and written documents overlooks what may be more important: deliberation and discussion between the individual and their surrogates, whether that is the family, the physician, or both. In fact, he said, ACP is less about the document or one specific directive and more about the process of discussions. That process, he

___________________

7 Additional information is available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/house-bill/4449 (accessed December 9, 2020).

added, starts not with specific medical interventions but rather with understanding an individual’s core values. In Lo’s view, ACP should be about not only withholding interventions but also preferences regarding a good death. Lo added, as Stuart noted earlier, that one of the hopes of ACP is that it relieves the burdens on surrogates who are making decisions in situations that are typically complicated and unanticipated.

Lo explained that the question that often arises and is hard to articulate in ACP is how much pain and suffering the individual is willing to endure, for how long, and for what benefit. One decision a person can make concerns the transition to palliative care. Many of Lo’s patients have said they want some reasonable attempts made to treat reversible problems, but only up to a point. However, defining that point in advance is difficult, Lo pointed out. He also noted that the Cruzan case is one example of the shift toward experts saying that it is appropriate in some cases to base decisions on the patient’s values, goals of care, and current best interests as interpreted by the appropriate surrogate. Over time, “this country legally, ethically, and religiously has made a huge shift to where we are now trusting the discretion and judgment of surrogates, who are often close family members,” said Lo.

In closing, Lo underscored that ACP does not and could not resolve all problems with end-of-life care. Even when ACP goes well, said Lo, decisions are difficult, and unanticipated decisions will still need to be made.

The Complexities of Advance Care Planning: What Are We Even Talking About?

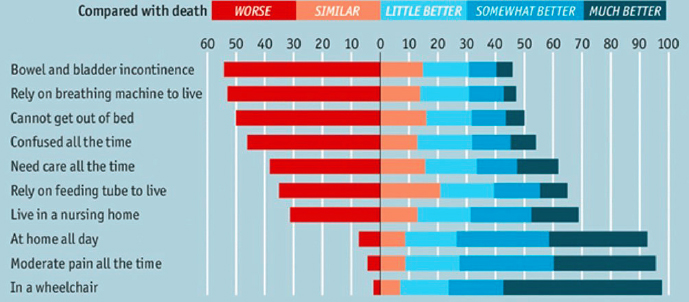

Rebecca Sudore, professor at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine, began her remarks by explaining that the original definition of ACP focused on making treatment decisions in advance, such as deciding about resuscitation or mechanical ventilation. This definition, however, did not account for issues related to the difficulty of predicting future contexts, the ability of humans to adapt to new circumstances and change their minds, and extrapolating treatment decisions about resuscitation to other decisions. As Sudore explained, the most important reason to reconsider this original definition is research showing that what matters most to individuals is not the treatment but rather its outcome and what life will be like afterward (Fried et al., 2002, 2006; Gillick, 2004; Halpern and Arnold, 2008; Lockhart et al., 2001; Loewenstein, 2005; McMahan et al., 2013; Pearlman et al., 2005; Perkins, 2007; Quill, 2000; Ubel, 2005; Ubel et al., 2005; Winter et al., 2003).

Sudore and her colleagues convened a large, international Delphi panel to develop a new definition of ACP, which states that it is a “process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care” (Sudore et al., 2017). Sudore explained that even as she and her colleagues were writing the paper proposing this revised definition, they stated that it was a starting point that would need to be revisited as the field matured. “I think we are learning that ACP is much more complex than this,” she explained. She noted that ACP has had many meanings and definitions and that when studies are being done or recommendations are being made, it is important to first describe the definition that is being used in that context.

Sudore referenced an organizational framework from Respecting Choices,8 an evidence-based model of ACP, which outlines “first steps,” “next steps,” and “advanced steps.” Sudore said these steps can apply to the trajectory of someone’s life course and their readiness to engage in the ACP process. For example, people in advanced stages of their life course may still be at the first steps of readiness to engage in ACP.

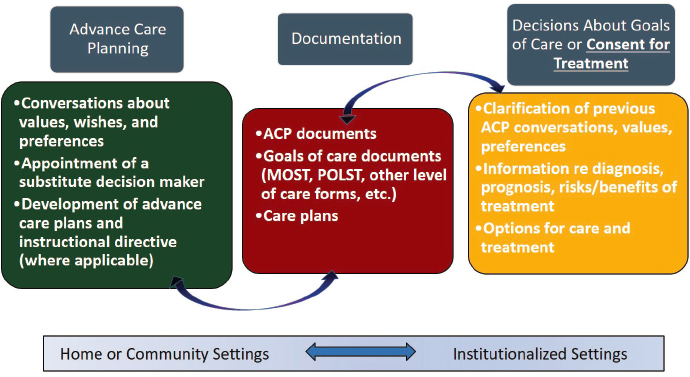

Sudore explained that ACP that focuses on values, wishes, and preferences involves a different kind of conversation than one that focuses on goals of care, in-the-moment decision making, or consent for a specific treatment (Sinuff et al., 2015) (see Figure 1). These conversations may differ based on the setting, such as the home versus the hospital, but each category (ACP, documentation, decisions about goals of care, or consent for treatment) has distinct components that guide conversations with patients. Sudore noted that the majority of the conversations she has with individuals, both as a geriatrics primary care physician and as an inpatient palliative care physician, involve values, wishes, and preferences, as listed under the Advance Care Planning section of Figure 1, rather than conversations about consent for a specific treatment.

Sudore further explained that ACP is influenced by the complex interplay of many stakeholders, including patients, surrogates, the community where social norms are established, clinicians, the health system and its ability to electronically retrieve ACP information, and the laws and policy that support ACP (McMahan et al., 2020). Sudore noted that in addition to this complexity, one of the major challenges for ACP is that that no single professional group or service line “owns” or is responsible for ACP.

___________________

8 Additional information is available at https://respectingchoices.org (accessed December 9, 2020).

NOTE: ACP = advance care planning; MOLST = medical orders for life-sustaining treatment; POLST = physician orders for life-sustaining treatment.

SOURCES: Rebecca Sudore presentation, October 26, 2020; adapted from Sinuff et al., 2015.

Additional complex factors are involved as well, including the existing injustices and health disparities that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated. “Millions of Americans do not have access to clinicians, health systems, or [insurance] policies that would support access to trained clinicians who could walk people step-by-step through the ACP process,” said Sudore, “and given the large amount of justified mistrust, some communities will only do ACP outside the clinical setting with their families and friends.”

Given this complexity, Sudore further explained, it may not be reasonable to expect an ACP intervention targeted to one or a few of these stakeholders to be able to positively affect all outcomes and solve all of the problems of the nation’s broken health care system. ACP definitions and reasonable outcomes may need to be defined for each stakeholder and setting.

Sudore pointed out that the interplay between these many complex factors has raised the question of why anyone should even attempt ACP, and she answered that the most important reason not to abandon ACP is that patients, surrogates, and clinicians express the need and desire for it,

particularly if they have had experiences making serious medical decisions for themselves or others (McMahan et al., 2020). Clinicians cannot make recommendations or guide care decisions without knowing a patient’s values and needs, which, in Sudore’s view, requires that patients and surrogates be prepared to communicate that information (Perkins, 2007; Torke et al., 2009). “Without some form of preparation, patients and surrogates will not be able to communicate their values effectively, and this is especially true when people are under stress and when they have no prior relationship with the clinicians they may find themselves interacting with in a crisis situation,” explained Sudore. In an effort to help prepare individuals and their surrogate decision makers, Sudore and her colleagues developed the person-centered Prepare for Your Care program9 (Sudore and Fried, 2010; Sudore et al., 2018b). Similar programs include Advance Care Planning Decisions,10 the Plan Well Guide,11 and community-based tools, such as those offered by the Conversation Project.12

Sudore explained that research shows that patients want to talk to their clinicians about ACP, they expect health care providers to initiate ACP conversations, and they view it as a way to prepare surrogates and decrease their decisional burden. In her view, clinicians value ACP as an important part of their jobs to help prepare patients and families for making decisions. However, she noted, research has produced mixed results related to measuring outcomes (Bischoff et al., 2013; Bond et al., 2018; Detering et al., 2010; Houben et al., 2014; Jimenez et al., 2018; Silveira et al., 2010; Sudore et al., 2018a). In some studies, ACP is associated with increased advance directive completion, increased patient satisfaction with care, improved quality-of-life and goal-concordant care, increased surrogate–clinician communication, and decreased stress for the surrogate decision maker. However, a 2018 review of 80 systematic reviews revealed that many ACP studies, as well as the systematic reviews themselves, were deemed to be of low quality. Sudore noted that the low-quality research makes it difficult to develop definitive recommendations (Jimenez et al., 2018).

___________________

9 Additional information is available at https://prepareforyourcare.org/welcome (accessed December 9, 2020).

10 Additional information is available at https://acpdecisions.org (accessed December 9, 2020).

11 Additional information is available at https://planwellguide.com (accessed December 10, 2020).

12 Additional information is available at https://theconversationproject.org/nhdd/advance-care-planning (accessed December 9, 2020).

Sudore pointed out that questions remain concerning what the outcomes for ACP should be. “Is the outcome of completing an advance directive enough?” she asked. “Is goal-concordant care reasonable given the very well-known measurement challenges of this outcome?” A Delphi panel that focused on defining outcomes for successful ACP concluded that although the panelists considered goal-concordant care to be the “Holy Grail,” they also acknowledged the difficulty in measuring that outcome as well as how focusing on that outcome could set the field up for failure (Sudore et al., 2018a).

In light of the mixed prior findings from many low-quality studies and systematic reviews, Sudore and her colleagues completed a scoping review of 69 high-quality ACP randomized trials from 2010 to 2020, none of which had been included in any prior reviews (McMahan et al., 2020). The review found that results of the primary outcomes from all ACP intervention types, including written materials, videos, and websites, were consistently positive. Specifically, the review revealed increased patient and surrogate satisfaction with communication and medical care and decreased surrogate and clinician distress, outcomes known to be important to patients. Despite these findings, the review found little or no evidence to support improved health status outcomes (such as quality of life) and quality-of-care outcomes (such as goal-concordant care) (McMahan et al., 2020).

Sudore noted the complexity of issues related to ACP, such as how the process can mean different things to different people depending on the context, creates uncertainty as to what precisely is needed to improve ACP. She suggested that new definitions might be needed to address context, life course, timing, and stakeholders. “I think we very much need patient and caregiver input on these definitions,” said Sudore. She also encouraged consideration of the outcomes that one could reasonably expect from ACP, given that the process is but one small part of a broader, complex, and fragmented health care system. Sudore reiterated that because ACP is not owned by one specialty, program, or service line, no one group may be committed to moving it forward or studying successful clinical workflows.

In closing, Sudore pointed out that the differing perspectives on ACP present an opportunity to normalize the process across disciplines and the community. Sudore ended her remarks with a question to the audience: “Should ACP programs be taking a broader, more holistic approach where we use rigorous implementation science research principles in considering multiple stakeholders, context, culture, and workflows?”

Discussion

To open the discussion session, moderator JoAnne Reifsnyder, executive vice president of clinical operations and chief nursing officer of Genesis HealthCare, returned to the two presenters who shared their lived experiences and asked Stuart and Harris how patient advocacy can help people understand and embrace the importance of talking about what matters to them with the people who matter. Harris replied that patient advocates have to regularly repeat that message over and over again to get people to realize that ACP is an important process in which to engage. Stuart added that the personal stories that patient advocates bring to the table can be a powerful spark to start the dialogue that people need to have with their loved ones.

When asked if she or her family members understood the terminology when first introduced to it, Stuart said her family did not have a good grasp of what ACP meant and who was supposed to implement the plan. While she knew what had to be done, it was difficult having the conversation with her father, so she tried to pay attention as best she could to the things he would mention as important. Harris said her husband did not understand the context for ACP, but he did understand the importance of the two of them making decisions before it was too late. Drawing from her 15-year experience as a health care professional and case manager working with ACP, Harris commented on the importance of explaining concepts and contexts in small pieces; she recounted how one patient thought a living will was designed to allow her son to take her money.

Reifsnyder asked Lo to comment on a February 2020 New Hampshire Supreme Court ruling13 that “appears to prioritize best interests over substituted judgment.” Lo replied that on one hand, it does not make sense to talk about substituted judgments—where the proxy will make a decision that they know or think their loved one would make if they could decide for themselves—if a patient who is unable to communicate their wishes has not previously addressed a particular issue or given an indication of core values from which a non-family member or designated caregiver can extrapolate. On the other hand, in some situations involving the patients who understand what is about to happen to them, doing what the patient said makes sense.

___________________

13 Additional information is available at https://law.justia.com/cases/new-hampshire/supreme-court/2020/2018-0701.html (accessed December 9, 2020).

Responding to a question about intermediate goals that could measure success in achieving goal-concordant care, Sudore said that is what everyone wants, but it is hard to measure because the situation at the bedside can change at the last minute. “From the scoping review and what we are hearing from patients and surrogates, some of the most important outcomes are about surrogate burden,” she explained, “and some studies are showing decreased moral distress [for clinicians].” In her opinion, those are good proxies for whether things went as well as they could have. “Some of that could have been from great advance care planning, some could have been the result of having wonderful clinicians at the bedside, or a combination of both,” she added.

Lo commented that one challenge that dementia and cognitive impairment creates is that the patient is no longer the individual that people remember. Sudore added that just because someone is cognitively impaired does not necessarily mean that they do not have the capacity to make certain decisions. In fact, she and her colleagues have found that people with mild to moderate cognitive impairment can engage in the Prepare for Your Care program and consistently have the necessary conversations about their values.

Given Sudore’s research, which has shown that a key motivating factor driving patients to complete an advance care plan is to alleviate the burden on surrogate decision makers and that ACP appears to reduce that burden, Reifsnyder asked Sudore if those factors have changed the way she thinks about the Prepare for Your Care program. Sudore replied that the program was meant to be a step-by-step process that can be completed with an individual’s surrogate, so recent research has only emphasized the importance of having these conversations with surrogates. In fact, The Greenwall Foundation is funding Sudore’s efforts to create surrogate preparation modules for the program. She added that she and her colleagues are now attempting to include surrogate outcomes in their research studies.

INTERPRETING THE EVIDENCE BASE FOR ADVANCE CARE PLANNING

What Is the Evidence and Why Does It Matter?

Opening the workshop’s second session, Sean Morrison, professor of geriatrics and palliative medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, gave a brief overview of the history of ACP and discussed the evidence

and why it matters in the context of achieving the quest for goal-concordant care. He reiterated the Delphi definition shared earlier by Sudore: ACP is “a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care” (Sudore et al., 2017). Morrison added that “the goal is to make sure that people receive care that is consistent with their values, goals, and preferences during serious and chronic illness. And for many people, this is going to include choosing and preparing a trusted person to make decisions for them in the event that they lose decisional capacity.” This is different, he said, from having real-time discussions about real-time decisions or in-the-moment discussions around goals of care either with patients or with proxies. “I think all of us would agree that it is critically important that we do this every single day, but that it is not advance care planning. There is no ‘advance’ in that care planning,” he added.

Morrison noted, as Lo stated in the first session, that ACP has a long, complicated history beginning in the 1960s when patients were receiving unwanted treatments at the end of life, which led to the first living will in 1967. The realization that it is impossible to predict all treatment decisions that might arise led to the idea that if a person could not state specifically what treatments they would want in the future, perhaps they could designate a trusted individual to make those decisions. The result was the advent of the health care proxy or durable power of attorney, which California first signed into law in 1983 (Sabatino, 2010). According to Morrison, the challenge then became one of engaging reluctant physicians to have the necessary conversations with their patients, which led to the proliferation of ACP programs that did not require a physician office visit or physician–patient interaction.

Unfortunately, Morrison remarked, research indicated that even when patients documented their preferences and named their proxies, providers were not acting on those preferences. This realization, said Morrison, led to Oregon creating the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST) form in 1991, which translated patient and family preferences into actionable physician orders. However, physicians were still not engaging in ACP discussions and not completing POLST forms, which put pressure on Medicare to provide reimbursement for ACP conversations.

Morrison noted, though, that some patients who have completed a POLST form are not aware they have done so or even what the form contains. He added that many patients who came to the hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic and had POLST forms in their electronic health

records (EHRs) disagreed with what was on them and instead opted for treatments that saved their lives. “We also saw that the simple presence of a POLST form during the COVID-19 pandemic discouraged many of our providers from having complex discussions because they simply did not have time and it was easier just to look at the form,” he said.

Turning to the evidence base for ACP, Morrison noted that although many of the studies have been of low quality, $30 million in federal funding has been spent on ACP research in the past 30 years (Morrison, 2020). This research includes randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of more than 16,000 individuals and the scoping review of 69 studies (McMahan et al., 2020) discussed earlier. That evidence, said Morrison, suggests that advance directives are a reasonable surrogate for a completed ACP discussion, be it for a treatment directive or designation of a health care proxy. He added that the prevalence of advance directives increased from 26 percent in 1993 to 37 percent in 2016, but in 2020—30 years after the Patient Self-Determination Act—less than half of U.S. residents have one (Knight et al., 2020; Waller et al., 2019).

Morrison explained that researchers have studied adults of all ages: healthy, hospitalized, in critical care, living in the community, living in nursing homes, and with multiple different diseases. “We have looked at attitudes, beliefs, and preference, and what we hear consistently from the public is that this is something that they would want and they would want their physician to discuss with them,” said Morrison. Investigators have also examined numerous interventions, including patient education and decision support; physician, nurse, and social worker education and reminders; nurse, social worker, and physician-led group and individual counseling; and individual or group counseling provided by a trained advance care facilitator.

Morrison noted the many positive findings from the preponderance of evidence, such as that these interventions improve people’s knowledge about ACP and increase the completion of advance directives (Jimenez et al., 2018). Data suggest that these interventions can also increase documentation and even the rate of ACP discussions with physicians if it is measured immediately after the intervention (Jimenez et al., 2018). Morrison noted, however, that little is known about the long-term effects of these interventions. Moreover, Morrison said, high-quality studies offer minimal to no consistent evidence that ACP can (1) influence medical care at the end of life for patients lacking decisional capacity, (2) enhance the quality of death and dying, (3) increase the likelihood that end-of-life care is consistent

with patient preferences, (4) improve patient or surrogate satisfaction, or (5) improve surrogate quality of life or bereavement outcomes.

In Morrison’s view, researchers have been unable to find conclusive evidence that ACP works to achieve its main outcomes, due in part to the reality that the health care system must be organized to respond in ways that are consistent with the values and goals that were identified through the ACP process, wherein patients are able to articulate their values and goals and identify which treatments would align with those goals in hypothetical future scenarios. Morrison said,

Clinicians need to honor those preferences and decisions, and our health system and the society at large that we work in [needs to] be able to support that goal-concordant care—so that if somebody calls 911 in the middle of the night and says “my husband is in terrible pain but does not want to go to the hospital,” somebody will come and be able to manage that pain rather than having to call 911 for assistance, and if we [can] do all this, patients will receive goal-concordant care.

However, one complication is that treatment choices near the end of life are not simple, logical, linear, autonomous, or predictable. Rather, said Morrison, they are complex, uncertain, socially determined, emotional, and malleable depending on the clinical situation. Moreover, Morrison remarked that substituted judgment presumes that surrogates can do three things:

- Extrapolate specific treatment decisions from distant general ACP discussions;

- Piece together what their loved one would have wanted; and

- Disentangle their own preferences, emotions, and feelings of guilt from the decision.

Morrison further noted that treatment decisions do not occur in a vacuum; they are driven by financial incentives and the marketplace. “We know that supply and demand influence the care that people receive in the setting of serious illness,” he said, “and that [treatment decisions] are influenced by our societal capacity to support patient needs and are strongly influenced by regional cultures and practice patterns.”

Morrison remarked that continuing to invest in ACP is not benign and does have consequences. For example, the poor communication skills that often characterize ACP practices can lead to goal-discordant and suboptimal care (Heyland et al., 2006; IOM, 2015; You et al., 2015). Morrison said that merely varying the language used in ACP can change treatment decisions.

He added that treatment or surrogate decisions are strongly influenced by how choices are framed, and the lack of quality control around most discussions can lead to withholding beneficial treatments (Heyland, 2020).

Morrison concluded his remarks with a question: “Why is there such strong faith in the premise of ACP despite 30 years of evidence to the contrary? I could argue that if we had this evidence base in any other area of medicine, we would not be continuing.” He listed several possible reasons:

- Respect for the individual and a belief that ACP matters,

- The uniquely Western belief in individualism,

- Commitment bias (the field is so committed to making this work that there is no vision for a different way forward),

- Confirmation bias (finding positive results and ignoring the negative results),

- Financial incentives that reimburse clinicians for having ACP discussions, and

- An industry that has developed to support and promote ACP as a result of the lack of available alternate approaches.

In closing, Morrison wondered if a more productive approach would be to narrow the focus of these efforts to simply having everyone appoint a health care proxy. “I would argue that the preponderance of evidence suggests that the long and winding road of ACP should end,” said Morrison.

Perhaps, as Dr. Sudore pointed out, we should be focusing on how to better prepare [patients and families] to have these conversations. Perhaps we should be thinking about how to better guide surrogates through in-the-moment decision making and how to have real-time communication about real-time decisions rather than focusing our effort on something that, for the most part, just has not shown great benefit.

How Clinical and Health Care Leaders Use Advance Care Planning Research

Carole Montgomery, executive medical director of Respecting Choices, explained that she would not be speaking from the perspective of a researcher, but rather of a clinical care leader who is a consumer of the research on ACP. She added that she would address how that research can inform and guide the work that she and other executives do in real-life settings with organizations and communities that aim to improve the stan-

dard of care for everyone. Referring to the earlier discussions, Montgomery noted that the maturing definition of ACP has occurred in the context of other changes in health care, including the growth and development of palliative care as a recognized medical specialty and the movement toward person-centered care as a pillar of quality. The person-centered care movement, added Montgomery, was influenced by consumerism and calls for transparency, which has driven a shift in the perspective that patients can and should play a role in the decision-making process about their care and treatment. Moreover, clinicians have had to accept that knowing a patient’s goals and values can and should change their role in the decision-making process. This attitudinal evolution has occurred within the greater context of a health care system that is increasingly complex and fragmented, said Montgomery. “With all of this shifting in the surrounding milieu of health care, it is no wonder that it is a significant challenge to interpret the mixed history of evidence around ACP,” she said.

In that context, said Montgomery, the scoping review that Sudore discussed (McMahan et al., 2020) is an important body of work that adds to the evidence base for ACP and addresses the deficiencies of prior systematic reviews by including only RCTs from the past decade. Sudore’s review also accurately reflected the variety of research occurring in the ACP realm, including research that tested different interventions enacted across a variety of populations, in different settings, and at various times in the trajectory of life and illness, said Montgomery. All told, the 69 reviewed studies encompassed 170 different outcomes and teased out which outcomes were most often affected across all the studies that examined those outcomes.

Before reviewing these outcomes, Montgomery stressed that the ultimate stakeholders in this work—patients, their surrogates, and family members—have already weighed in on the ACP outcomes that matter most to them; based on patients’ lived experiences, they want to be involved in their care and decisions (Guyatt et al., 2004). “They want to talk with their medical team about ACP to help prepare them for decision making, and they see ACP as a way for preparing their families and surrogate decision makers, decreasing their loved ones’ decision-making burden, and ultimately ensuring that their own wishes are honored,” said Montgomery (Curtis et al., 2001; Sessanna and Jezewski, 2008; Sharp et al., 2013; Singer et al., 1999; Steinhauser et al., 2000; Sudore et al., 2020; Wenrich et al., 2001).

Montgomery noted that the majority of the recent high-quality RCTs evaluated in the scoping review showed significant effects of those very same patient-desired outcomes. For example, 72 percent of the studies evaluat-

ing process outcomes of ACP revealed improvements in patient readiness, confidence, and self-efficacy. Similarly, 86 percent of the studies evaluating action outcomes found increased completion of ACP conversations, discussions with family, or creation of ACP documentations; 88 percent found congruence between a patient’s goals, values, and beliefs and their surrogate’s or clinician’s understanding; and 100 percent found that patients, surrogates, and clinicians were satisfied with those communications. All of the studies that examined the health impact on surrogates saw reduced depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and complex grief (McMahan et al., 2020).

In terms of goal-concordant care, Montgomery said she believes that if this work is done correctly, goal-concordant care should be hard to measure. As she explained,

Patients want help to prepare for making decisions in the future, not to make decisions prematurely for a future hypothetical event, so they and their surrogates will be ready to participate as equal partners in that decision making when that future unpredictable, complex situation arises, because that is the moment when treatment preferences are put into context, and goal-concordant care either does or does not occur. It is not something where a static goal can be recorded in advance against which future care is then graded.

In Montgomery’s view, surrogates’ satisfaction with the communication involved in decision making and whether they experience less of a burden in making decisions are all appropriate proxy measures for goal-concordant care. In that respect, Montgomery believes that the scoping review (McMahan et al., 2020) helped show that ACP has a significant, positive effect on the outcomes that matter most to patients and their surrogates.

Montgomery said she is encouraged that recent studies are incorporating more diverse populations, but she cautioned that it does not mean that all populations are sharing the achieved outcomes equally. She argued that in general, health care must aim to become more trustworthy, and preparing individuals and their loved ones to engage in health care decision making could be a first step toward that goal. In fact, she said, recent research indicates that ACP is accomplishing that goal among diverse populations. For example, one study used the Respecting Choices intervention with HIV-positive urban adult populations and found that ACP improved treatment preference congruence between patients and their surrogates, an understanding that persisted even as the patients’ treatment preferences changed (Lyon et al., 2020). Two other studies found that the Prepare for Your Care intervention achieved a higher level of engagement in ACP among diverse

English- and Spanish-speaking older adults (Sudore et al., 2020) and among those with limited health literacy or who spoke only Spanish (Freytag et al., 2020). Montgomery pointed out, however, that if preparing individuals to engage as equal partners in health care is a first step toward becoming trustworthy, completing that journey requires embracing the shift in power at the point of decision making and having clinicians accept that they cannot know the right care to deliver without knowing what matters most to the person for whom they are caring.

In closing, Montgomery acknowledged the value of practice-based evidence that emerges from shared experiences, clinical examples, and expertise developed during clinical practice. She emphasized the important role that implementation science plays in examining what works, for whom, and under what circumstances, as well as in determining how to adapt and scale effective interventions in ways that are accessible, equitable, and able to confirm the strategies that work. In that regard, she argued that pragmatic trials should have a significant role in future ACP research because they are better able to measure and evaluate the challenges of an evolving complex process across various stakeholders and in real-life situations. “This should be our path forward to achieve what we know patients and surrogates want and to continue on the journey to becoming trustworthy partners in their care,” concluded Montgomery.

Making Sense of the Evidence

Daren Heyland, professor of internal medicine and critical care at the Queen’s University School of Medicine in Kingston, Canada, began by noting that as a critical care clinician, he has witnessed a significant amount of suffering when people come into an intensive care environment ill prepared for decision making and ultimately do not always receive the care that is right for them. “If the goal of ACP is to try and increase person-centered care, increase goal-concordant care, or increase the process of communication in decision making around the use or non-use of life-sustaining treatments, I think we have a long way to go,” said Heyland.

To support that statement, Heyland referred to several studies showing that patient and family wishes are not always followed—even with an advance care plan. For example, one study of elderly patients in the ICU on life support found that 25 percent of the families had stated a preference for only “comfort measures” (Heyland et al., 2016), while another study found that of the patients who preferred to forgo cardiopulmonary resuscitation

(CPR), 35 percent had orders in their medical records to receive it (Heyland et al., 2015). Moreover, a study of clinician–family communication found that 26 percent of family conferences did not address patient values and preferences, and only 8 percent of decisions were based on these (Scheunemann et al., 2019).

Heyland noted that in the evidence base supporting ACP, there is tremendous heterogeneity in terms of the intervention and how the investigators conceptualized it, the populations studied, the case mix, and the patients’ life journeys (McMahan et al., 2020). “Our valuation of this corpus of data might be a bit dependent upon which piece or pieces of that heterogeneous body of data we examine carefully,” said Heyland. The key point, he continued, is that that body of data is too heterogeneous to make meaningful conclusions. “I do not think it is fair to say that ACP works or does not work,” noted Heyland. To make such a determination, “we need to move to a higher degree of granularity or homogeneity that includes standardization about what works and what does not work.”

Heyland also expressed concern about the current definition and conceptual framework for ACP, given that planning for death under conditions of certainty is not the same as planning for serious illness under conditions of uncertainty. Additionally, he cautioned that decontextualized planning conversations can be equated with medical decisions. “The current approach, where we rely heavily on conversation and open-ended questions that elicit values and preferences, is also problematic and may explain why there is still quite a bit of medical error in this space,” said Heyland. Heyland cautioned that people are not always informed consumers; it is often not as simple as asking them what they want.

One problem with ACP as it is currently practiced, explained Heyland, is that most care plans are framed around the end of life. What happens, he asked, when someone is short of breath and the critical care clinicians are trying to decide to use or withhold life-sustaining treatments? “I do not know if you are dying, so what validity do plans have when made under the context of ‘if I am dying, this is what I want or do not want’ when applied to a different context when there is no certainty that this is your final episode?” He noted that research on the use of POLST has shown that more than one-third of the time, patients receive care in the ICU that is not concordant with their wishes (Heyland, 2020). “Is this a problem with us, or it is a problem with the tool that focuses on end-of-life care?” he asked.

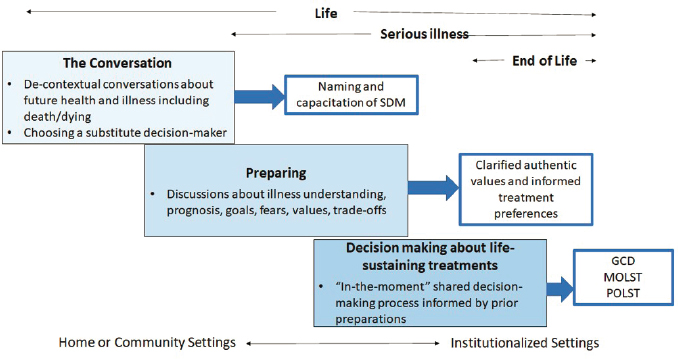

Heyland pointed out that another way of conceptualizing ACP is by the tasks that ultimately lead to ordering life-sustaining treatments (see

NOTE: GCD = goal-concordant decision making; MOLST = medical orders for life-sustaining treatment; POLST = physician orders for life-sustaining treatment; SDM = substitute decision maker.

SOURCE: Daren Heyland presentation, October 26, 2020.

Figure 2). This approach does not skip the step of preparing the patient with discussions about their illness; their prognosis; their fears, goals, and values; and the trade-offs that come with any decision. He also believed that the current ACP process violates legal provisions intended to protect the informed consent process, which is designed to explain risks, benefits, and possible outcomes as part of the thorough discussion that leads to shared decision making. Instead, he argued for focusing on better preparing patients and surrogate decision makers to make decisions in the moment, rather than using a document that has limited validity and clinical utility to make such decisions in advance (Heyland, 2020; Sudore and Fried, 2010).

Heyland explained that he and his colleagues have researched whether people are able to express their authentic values and informed treatment preferences, and the results indicate they are not (Heyland et al., 2017). “Those value statements [people] make are sometimes in conflict with other things that come out of their mouth as another expression of value and bear no relationship to what might be the treatment preference,” he explained. For example, the statement “live as long as possible” correlated positively with a seemingly contradictory statement of “be comfortable and suffer as little as possible.” As a result, clinicians are left trying to interpret

what a value statement means and how it connects to a medical order to use or forgo life-sustaining treatments (You et al., 2015). That process, in Heyland’s view, is irreproducible, nontransparent, and an explanation for why so much medical error exists. It also argues for the need for more decision-making support if the goal is to ground people’s care in their individual values and preferences, he added.

For this reason, Heyland noted that he and his colleagues have shifted from planning for death to an approach that helps people think about serious illness, provides more sophisticated tools using constrained values, and uses a decision aid that highlights the difference among ICU care, medical care, and comfort care. Compared to other ACP tools, their program, called the Plan Well Guide:

- discriminates between planning for terminal care versus planning for serious illness,

- explains how clinicians make medical decisions under conditions of uncertainty,

- uses a constrained values clarification tool where respondents must pick between competing values,

- uses grids to transparently connect stated values to respondent preferences for medical treatments during serious illness, and

- provides a first-in-class decision aid on the different levels of care (Heyland et al., 2020).

Heyland noted that an RCT (Heyland et al., 2020) revealed that the Plan Well Guide increased the likelihood of patients receiving the care that is right for them (as determined by the constrained value clarification tools and elicited through the guide) and reduced decision conflict. In addition, clinicians in the study reported spending less time finalizing the goals of care with patients who received the intervention compared to usual care. Moreover, the study demonstrated that the majority of patients and surrogates were quite satisfied with the experience and would recommend it to others.

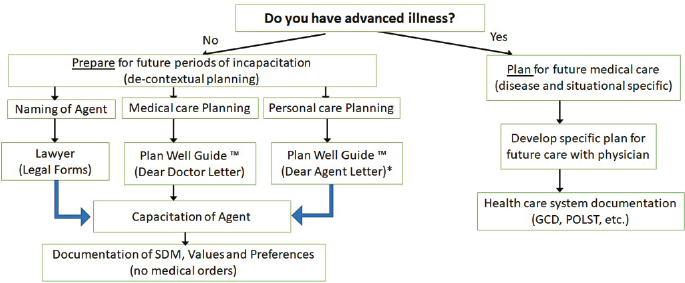

Based on these results, Heyland suggested a new paradigm, which he called Advance Serious Illness Preparation and Planning (see Figure 3). In this paradigm, most activities focus on preparing people to be able to express their authentic values and informed treatment preferences in the moment using more sophisticated tools and decision aids.

Heyland concluded his presentation by reiterating his belief that the way forward is to shift from the current approach framed around making

NOTES: *The Dear Agent Letter has yet to be developed. GCD = goal-concordant decision making; POLST = physician orders for life-sustaining treatment; SDM = substitute decision maker.

SOURCE: Daren Heyland presentation, October 26, 2020.

treatment decisions in advance for end-of-life care to an approach that aims to provide optimal, person-centered medical care for people with serious illness in situations of uncertainty about whether they are experiencing the end of life.

Advance Care Planning Is a Right: A Medical–Legal Perspective

The session’s final speaker, Patricia Bomba, vice president and medical director of geriatrics at Excellus BlueCross BlueShield, began by thanking Stuart and Harris for providing important real-world context for the workshop speakers’ presentations by sharing their lived experiences. Referring to Lo’s earlier description of the Patient Self-Determination Act, Bomba concluded that everyone has a right to make medical decisions throughout their lifetime—including at the end of life.

Bomba explained that over the 40 years that she has been a practicing geriatrician, she has seen medical care shift from a paternalistic model, where physicians made all of the decisions, to an autonomous model that expects patients to make decisions. The desired state, in Bomba’s view, is one of shared decision making but also acknowledges that in-the-moment decisions in the ICU or ED are often complicated by the fact that many individuals lack the capacity to decide for themselves. Bomba briefly recounted a few stories that illustrate the value of ACP. One couple prepared

in advance for the end of life, reducing the burden on the surrogate and family, while another individual thought he had all the time in the world, did not prepare, and left his wife and niece to suffer through more than 3 months of seeing their loved one on life support. Bomba shared that in the latter case, the family members struggled for years with the decisions they had made. Rather than abandoning ACP, in Bomba’s view, it is important to continue working toward a culture change that integrates ACP and health care planning in the same way that legal planning and financial planning have already been well integrated into everyday life.

Bomba noted that in the United States, all 50 states have their own forms and public health laws regarding end-of-life decisions. In New York, for example, Bomba explained that ACP has evolved in a way that aligns with the Delphi definition presented at the start of the workshop. New York has taken a population health approach in which advance directives focus specifically on choosing the appropriate health care agent identified in the health care proxy, with living wills being less of a focus, as these are difficult to interpret due to the coexistence of potentially reversible disease and end-stage irreversible illness. Bomba pointed out that medical orders for life-sustaining treatment (MOLST) is a set of medical orders created after a thoughtful discussion that focuses on life-sustaining treatment preferences for individuals who have advanced illness or frailty, such as resuscitation preference, respiratory support, and hospitalization transfers. Underscoring that this is a continuous process, Bomba noted that what someone values at age 18 is different from what they value at 81 and is certainly different in the last year of their life. In Bomba’s view, Community Conversations on Compassionate Care (CCCC)14 is an example of an ACP program for the general population 18 years and older that aligns with the Delphi definition. Bomba explained that the program emphasizes learning about decision making, sharing values and beliefs, and choosing the appropriate trusted person to serve as a health care agent.

Bomba noted that New York’s CCCC program, which the state has been using since 2001, doubled the percentage of people preparing health care proxies from 20 to 42 percent in upstate New York by 2008 (Bomba and Orem, 2015). Bomba pointed out that virtually every state is now working on developing this type of program for those who might die in the next year, are living in a nursing home or receiving long-term services at

___________________

14 Additional information is available at https://compassionandsupport.org/advance-careplanning/cccc (accessed December 10, 2020).

home, or are near the end of life. Noting the many studies about POLST form completion and goal-concordant care, she highlighted one study of nursing home residents that found that completed POLST comfort care orders are strongly associated with fewer treatments compared to situations without a completed POLST form or a form calling for full treatment (Hickman et al., 2010). A study conducted in a hospital setting found similar results (Lee et al., 2020).

Bomba noted that completing the MOLST form requires a thoughtful discussion in order to achieve goal concordance. New York uses seven checklists to ensure compliance with the ethical and legal requirements for end-of-life decisions and a standard MOLST protocol consisting of the following eight steps (Bomba, 2005, revised 2011):

- Prepare for discussion

- Understand the patient’s health status, prognosis, and ability to consent

- Retrieve completed advance directives

- Determine decision maker and public health law legal requirements

- Determine what the patient/family know

- Explore goals, hopes, and expectations

- Suggest realistic goals

- Respond empathetically

- Use MOLST to guide choices and finalize patient wishes

- Engage in shared, informed medical decision making

- Undertake conflict resolution

- Complete and sign MOLST

- Follow public health law and document conversation

- Review and revise periodically

This multi-step process, said Bomba, ensures that MOLST is completed properly and that patients, families, and clinicians are prepared for the end-of-life discussion. She added that New York has three public health laws and a process laid out by the Surrogate’s Court Procedure Act 1705B15 that governs decisions for those who have intellectual or developmental disabilities and lack decision-making capacity.

___________________

15 For more information, see https://codes.findlaw.com/ny/surrogates-court-procedureact/scp-sect-1705.html (accessed December 10, 2020).

According to Bomba, a key lesson learned has been the importance of screening for appropriate populations; assessing capacity, given that people may still have the ability to make decisions; and making sure that people understand their health status and prognosis before they think about their goals for care. Bomba noted that developing a palliative care plan to ensure that pain and symptom management is available at all times and that the caregivers receive support is also important.

New York has developed a secure website16 to serve as an online MOLST completion system and a registry, which is person centered and meets all of the legal requirements spelled out by state law. She further explained that the website can integrate with the major EHRs and health information exchanges, including HealthX.17 In Bomba’s view, the website has improved the quality of care, as well as patient safety, and it provides access to completed MOLST forms during an emergency. Bomba added that it also promotes coordinated, person-centered care by improving work-flow within and across facilities. She shared that, as of September 30, 2020, approximately 50,000 live patients, with a mean age of 82 and a median age of 85, have completed forms in the registry. Eighty-two percent expressed their preference for not wanting to be resuscitated, 72 percent did not want to be intubated, and 21 percent stated they did not want to be hospitalized. During the COVID-19 pandemic, 20 percent of the individuals reviewed and renewed their MOLST orders (Excellus BlueCross BlueShield, 2020).

In closing, Bomba explained that working with community partners on culture change and moving upstream with the appropriate populations in the state’s clinical practices has helped New York avoid some of the pitfalls that other speakers discussed. “We know we need to choose a trusted person, foster culture change, build patient-centered systems, and establish metrics that are different for the general population regarding advance directives versus medical orders,” said Bomba. “The bottom line is it is complex but it is right, and we ought to be measuring what matters most to patients and families.”

Discussion

Discussion session moderator Susan E. Hickman, director of the Indiana University Center for Aging Research at the Regenstrief Institute,

___________________

16 See https://www.nysemolstregistry.com (accessed December 10, 2020).

17 For more information, see https://www.healthx.com (accessed December 10, 2020).

opened the discussion by asking Montgomery if she believes that early ACP is appropriate, and if so, under what circumstances. Montgomery replied that she fully supports the process definition of ACP because it talks about supporting all adults at any stage so they understand and share what matters to them. For Montgomery, talking about what some might call “upstream” ACP (as opposed to “just-in-time” planning) helps prepare individuals for making informed, thoughtful decisions and is useful precisely because serious illness is not always predictable. However, she added, the conversations in early ACP need to cover different content and probably have a different ending than those for an individual preparing for the end of life, when those decisions are more proximal. Montgomery added that she believes it is problematic to wait to introduce ACP only for those with serious illness. Doing so, in her view, puts clinicians in control of when to engage a patient more fully, which she said is disrespectful to individuals and their families.

Hickman asked Heyland to contemplate what is needed from the field to build on recent conceptual and methodological research. Heyland responded by citing a gap in the research in terms of how much clinicians help people develop their authentic value statements. “If you think about how much the research enterprise invests in measurement of patient-reported outcomes or quality-of-care metrics or quality-of-life metrics, we still ground important clinical decisions on patient values,” he said, “but where is the research and methodological development that helps us make sure that we are actually measuring something that is reproducible, something that is valid, something that is predictable or translatable into a clinical action?”

Another research gap that Heyland identified is in the area of decision aids, noted Hickman. Heyland remarked that a growing body of work shows that these aids support people with serious illness, helping them make better decisions. He emphasized that despite the existence of decision aids, implementation has lagged behind, resulting in people making decisions without having access to tools known to work.

When asked about his view of the different findings from the older review of lower-quality studies and the more recent review of RCTs, Morrison noted that, in his view, it was disrespectful to those who conducted the earlier studies to simply ignore them. That said, “when you look at the randomized controlled high-quality studies and you look at what they were designed to do … overwhelmingly, when you look at those results, the main outcomes were negative,” explained Morrison, even though what people cite

are the positive results. He added that in most cases, researchers were focusing on secondary outcomes that the studies were not designed to address; he attributed this disconnect to confirmation bias. Overall, in Morrison’s view, it is time to think about how to better guide people in their decision making at the time when they need to make decisions, not when thinking about hypothetical events.

Hickman asked Morrison if he was suggesting that clinicians not talk to patients about their goals and values ahead of time, even when using a model such as the one Heyland presented. Morrison clarified that he was arguing for not focusing time, effort, and money on conversations with people who may not experience serious illness for many years. “That is different from having a real-time, goals-of-care discussion about something that matters right now,” said Morrison.

Montgomery explained that she was not intending to convey the idea of disregarding studies simply because they were conducted decades ago. Rather, she said, it is important to understand the massive change that has gone on in health care in the 30 years since that research was conducted. Montgomery compared differing perspectives on ACP with the process of discharge planning, which was once thought to be a simple, singular event at a point in time with a clear owner and individual accountability. “Now we understand that as one piece of a complex process we now refer to as ‘transition of care’ and consider in a more holistic way,” she said.

Heyland clarified that what he and Morrison were arguing is that effort, energy, and further research should be devoted to better preparing people for in-the-moment clinical decisions and that having laypeople, even seriously ill people, make decisions in advance that are expected to be followed in the future risks leading to medical error.

Bomba emphasized the importance of the ACP process and said those with serious illness and advanced frailty need to have the opportunity, before they lose capacity, to weigh in on the decisions regarding their end-of-life care. To be able to do that requires ensuring that, over time, they have honest conversations about what matters most to them and are able to share that information with their health care agent or surrogate, as well as their family, as living and dying are both family events. In addition, she said, it is important that when someone gets to the place where their physicians would not be surprised if they died in the next year, that they are not making decisions without understanding their health status and prognosis. “If they think they have 10 years of life and they really are hospice eligible, their decision-making process would be different,” said Bomba.

Bomba shared that she uses four questions to guide her discussions with seriously ill patients. Will the treatment make a difference? What are the benefits and burdens; in other words, will the treatment help or hurt? Is there hope of getting better and, if so, what will life be like afterward? What do you value and what is important to you? “I think is incumbent on us to make sure we are answering those questions in thoughtful ways that help people make decisions,” she said.

Hickman, noting that Heyland had observed that terminally ill patients can make medical decisions in advance for future life-limiting complications in consultation with their clinicians, asked him if he sees a role for advance directives and POLST for people with life-limiting serious illness who are at risk of life-threatening clinical events. Noting that he did see a role, Heyland cautioned that the challenge is that those decisions are often made without the clinician who is involved in the actual in-the-moment decision making. “Imagine the scenario of a patient I saw with advanced cancer with a prescribed living will that said if ‘I’m dying, no heroics,’ but they present with heart failure. Do they know that with 24 hours of positive-pressure ventilation and a squirt of Lasix, I could get them back to how they were, still with a several-months’ trajectory of life?” stated Heyland. “I cannot cope with the uncertainty of what they knew, what they did not know, and how informed and comprehensive their conversation was.” He noted that the default in critical care is to intubate and sort it out later, which to him is a failure in the planning process. His preference is to shift away from making these treatment decisions in advance and instead codify values and preferences while recognizing that health care providers have to go through an informed consent process with the patient, if they are able when the appropriate time arrives, or with a substitute.

Bomba noted that medical orders, such as a completed POLST form, are not one-and-done decisions; they need to be reviewed and potentially modified in light of a change in health status, and serve as the basis for medical orders to be followed in an emergency. Heyland countered that real-time audits of real-time practice show that the POLST form is often used as an excuse to not have a conversation with a surrogate. “If there was a mistake in what was codified under one context and there is no conversation with the substitute, then medical errors are being committed,” he explained. Bomba replied that this is where a system like New York’s eMOLST can prove useful, as it documents the conversation and the accompanying medical orders.

On a final note, Hickman asked Bomba to comment on how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the thinking about ACP and elevated its

importance. Bomba reiterated that the online system she spoke about saw 20 percent of the completed MOLST forms reviewed and renewed due to the pandemic. Bomba noted that New York’s eMOLST users also reported that patients wanted to have additional conversations with their clinicians and perhaps change their eMOLST orders in light of COVID-19 and their current health status.

A BRIEF SUMMARY OF THE FIRST WEBINAR

To open the second session, Hickman provided a brief summary of the discussions from the first session. She first thanked the two volunteers from NPAF, Stuart and Harris, who generously shared personal stories of their experiences caring for loved ones through the course of serious illness and the end of life. Hickman noted that although both women discussed ways in which the health care system had failed them, they concluded that proactive conversations about goals, values, and preferences, while difficult, are incredibly important.

Hickman noted that Lo and Sudore provided a grounding framework for understanding the historical context of ACP and its evolution out of landmark case law, as well as significant advancements in developing consensus about how to define ACP and measure outcomes. The two presented the consensus definition for ACP as agreed upon by an international Delphi panel: “[a] process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals and preferences regarding future medical care” (Sudore et al., 2017). This definition, said Hickman, helps move ACP away from focusing only on documents and treatment decisions toward actually preparing people for communication and in-the-moment decision making.

The second session of the first part of the webinar focused on different interpretations of the evidence for ACP, followed by what Hickman characterized as a “spirited” discussion. Summarizing the key takeaways from that session, Hickman noted that the evidence base for ACP is equivocal because of significant quality issues in past research (Jimenez et al., 2018). In addition, though prior high-quality studies exist, these were often based on old conceptualizations of ACP, and as the field has matured, it has developed a broad recognition that the earlier conceptualizations do not capture the full complexity of ACP. Hickman explained that this complexity includes factors such as how the conversations may change based on patients’ readiness and where they are in their life trajectory. Moreover, despite the many

stakeholders involved in the ACP process—including patients, surrogate decision makers, the community, clinicians, health care systems, and policy makers—no single discipline or profession “owns” ACP. Another factor in the complexity of ACP, noted Hickman, involves understanding which outcomes are reasonable to expect, given that the “Holy Grail” of goal-concordant care may be hard to measure and that other outcomes, such as improved quality of life, may not be appropriate, particularly in a population nearing the end of life.

Increasingly, said Hickman, the field is developing consensus around measurement using meaningful, realistic outcomes. One recent review of 69 RCTs conducted over the past 10 years (McMahan et al., 2020) suggests positive outcomes in important areas, notably for decreased surrogate distress, an outcome that patients say is critically important to them. She noted that several of the panelists in this session argued that more research is direly needed in several areas:

- supporting patients and developing authentic value statements;

- using decision aids to support decision making in the course of serious illness;

- implementation science that accounts for local context and tailors interventions to the resources available in a given setting;

- informatics and online platforms, such as eMOLST, that can improve quality through standardized conversation elements, increased accessibility, and real-time updating; and

- pragmatic trials that aim to conduct science in the real world to overcome barriers that frequently prevent successful clinical trial outcomes from being widely implemented.

Hickman recounted differing opinions among the panelists about what constitutes ACP. One perspective argued that discussing goals of care in the context of making treatment decisions, which many consider to be part of informed consent, is distinct from ACP. A more broadly held view was that these activities often fall along the continuum of ACP interventions, ranging from identifying a surrogate to preparing patients for serious illness decision making. There was also disagreement about when patients with serious illness should be asked to engage in the ACP process. Some panelists argued that preparation for in-the-moment decision making should start well before a medical crisis occurs, while other panelists were in favor of a just-in-time communications model with clinicians instead. This panel also

raised concerns about how these ACP models might not meet the needs of underserved and disadvantaged patients who lack access to health care, minority communities that have experienced systemic racism and therefore mistrust the system and clinicians, or people with dementia or cognitive impairments who are unable to express their preferences and are poorly served by just-in-time decisions.

The panelists did agree that evidence suggests advance directives alone are inadequate, Hickman summarized. They argued that early ACP should focus on identifying and preparing surrogates and identifying broad goals but in general should avoid treatment decisions, as it is difficult to anticipate the context in which these decisions will apply. The panelists also agreed that preparation is a key component of ACP and that clinicians need to know patients’ values and goals to help support the best high-quality decision making.

Hickman concluded her summary by noting that