Enhancing Community Resilience

Disasters caused by natural hazards and other large-scale emergencies are devastating communities in the United States. In 2020, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a record 22 events associated with weather or climate caused losses exceeding $1 billion.1 These events, and many others of lesser magnitude, harm individuals, families, communities, and the entire country, including its economy and the federal budget. Cumulatively, the $285 billion-plus weather and climate events that have occurred in the United States since 1980 have cost the nation more than $1.875 trillion. Geophysical, technological, and man-made disaster events extend these losses and impacts on individuals, communities, and the nation.

In addition to hazard events, communities across the world experienced a major emergency event throughout 2020 and 2021 that was unmatched by scale in more than a century. As of mid-March 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused more than 500,000 deaths in the United States and more than 2.7 deaths million globally.2 Health impacts and measures to contain the spread of the virus have affected work, business, travel, and everyday engagement between people. The result has been significant economic impacts and exacerbated societal tensions—along political, racial, geographic, and socio-economic lines—as well as heroic efforts in the medical and public health communities and widespread community-based mutual aid efforts.

As part of its efforts to reduce the immense human and financial toll of disasters, in 2020 the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) asked the Resilient America Program of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene the Committee on Applied Research Topics for Hazard Mitigation and Resilience (see Box 1 for further information on the program). FEMA charged the committee with identifying “applied research topics, information, and expertise that can inform action and collaborative priorities within the natural hazard mitigation and resilience fields.” The committee’s charge directed us to convene two public workshops as the primary source of information for our work, supplemented by discussions with members of the Resilient America Roundtable. Biographical sketches of the committee members appear in Appendix A of this report. The full Statement of Task is as follows:

A committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will identify applied research topics, information, and expertise that can inform action and collaborative opportunities within the natural hazard mitigation and resilience fields. The committee will convene two public workshops as the primary

___________________

1 Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Overview, NOAA Centers for Environmental Information. [https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions], accessed March 23, 2021.

2 Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. [https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/], accessed March 20, 2021.

source of information for its work, supplemented by background materials collected for the workshops and discussions at public sessions of the Resilient America Roundtable.

Each workshop will focus on distinct hazard mitigation and resilience issues and research questions, such as compound and cascading hazard incidents; risk communication and decision making in a changing risk landscape; nature-based solutions, buyouts, and managed retreat options for coastal risks; and equity and social vulnerability considerations in risk and decision metrics. Following each workshop, the committee will prepare a brief consensus study report that identifies and summarizes key research topics for the applied research community in the specific areas discussed at the workshop. Each report will contain findings but no recommendations and will be limited to the topics covered at that workshop.

In our initial meeting, the committee examined a list of possible themes for the workshops generated by the Resilient America Program, its staff, and members of the committee. These themes included: Buyouts, Managed Retreats, and Relocation; Incorporating Future Climate Conditions into Local Actions; Nature-Based Infrastructure; Compounding and Cascading Events; Social Capital and Connectedness for Resilience; Making the Business Case for Resilience Investment; and Effective Risk Communications. We evaluated this list of potential themes based on our understanding of each theme’s importance to advancing hazard mitigation and resilience, the state of current science and practice available for applied research to each theme, and the potential for new insights and approaches offered by the theme. Based on these criteria, Social Capital and Social Connectedness for Resilience was selected as the theme of the first workshop and of this report. The second workshop and report will examine the theme of Motivating Local Action to Address Climate Impacts and Build Resilience (originally titled Incorporating Future Climate Conditions into Local Action).

GOALS OF THE COMMITTEE

Consistent with its charge, public workshops organized and delivered by the committee served as the primary input for our deliberations and conclusions. This report is not a proceedings or summary of the information gathering workshop on social capital and social connectedness for resilience. Rather, it represents our distillation of what we heard at the workshop and what we judges to be the most important topics for action by the applied research community.

This report contains the committee’s findings and conclusions but no recommendations, and is limited to the topics covered at the public data gathering events. To provide guidance for ongoing efforts to move science and data into action and to focus the attention and efforts of the applied research community, we were asked to prepare this report on an accelerated timescale. As a result, the committee did not conduct an in-depth literature survey to supplement its judgments. Instead, we designed the public workshop to survey existing knowledge and practice, and then combined the information presented at the workshop with our own knowledge and experience to arrive at a list of priority applied research topics. We recognize that significant and growing bodies of literature and experience exist for each of the chosen applied research topics, and recognize the need for a comprehensive inventory of information and expertise related to these topics. An initial list of references to the fields of social capital and social connectedness is provided at the end of the report.

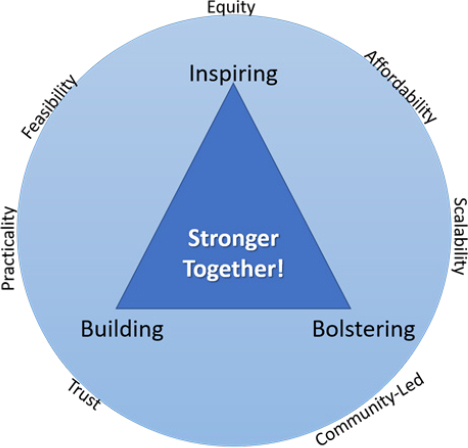

In considering our charge, the committee identified several requirements for applied research, including equity as a first priority to ensure that all communities, and all groups within communities, are included in and benefit from the applied research and enhanced resilience. To enable research results to be applied and adopted, we chose to focus on solutions that are practical, achievable, affordable, sustainable, and scalable. In addition, we highlighted the importance of incorporating mutual knowledge transfer to support community dissemination and implementation.

This report’s primary audience is the applied research community in the fields of hazard and vulnerability risk reduction, and resilience. The community includes hazard-specific and general resilience research centers as well as cooperative institutions engaged with states and local communities on hazard-related challenges. Broader audiences include public, private, nongovernmental, philanthropic, and academic organizations at the local, regional, state, and federal levels seeking to reduce the impacts, losses, and suffering across the United States from disasters due to natural or technological hazards, public health emergencies, and other significant threats to communities and the nation. The ultimate aim of the committee’s activities is to enable and empower applied research programs to engage in research that will strengthen capacities for hazard mitigation and resilience across the nation and around the world.

SOCIAL CAPITAL AND SOCIAL CONNECTEDNESS

For this workshop and report, we adopted generally accepted definitions in current use by federal agencies (see Box 2).

Social capital and social connectedness both point the pursuit of resilience in the same direction, but they proceed through different processes and mechanisms. Our charge was not to disentangle the nuances between social capital and social connectedness, and what follows will consider these two parameters in unison. However, we recognize that they have distinct properties and that, for instance, a community may accumulate the trappings of social capital (e.g., a series of amenities or built opportunities to gather in groups) but lack social connectedness or have a high level of social connectedness without having done so via common aspects of social capital.

Two complementary definitions apply to term “community” as used in this report. The first is Talcott Parsons’ definition of community from his essay Citizenship and Modern Society, in which community is defined as a “collectivity, the members of which share a common territorial area as their base of operation for daily activities.” This definition informs discussions and actions regarding the built environment, climate-driven hazards, and public spaces. Ferdinand Tonnies’ definition of community as “an organic natural kind of social group whose members are bound together by the sense of belonging, created out of everyday contacts covering the whole range of human activities” extends this discussion. This definition includes community organizations and local governments as well as groups like grassroots organizations, digital communities, and those centered around specific issues, such as those that galvanize social justice movements. In this work, the challenge at times is to be specific, but also inclusive. Approaching community as an important, defined part of human understanding is crucial, but room must be left for new concepts and convergence where necessary.

PUBLIC WORKSHOP

On February 25, 2021, the committee held a 1 day-long virtual webinar on the theme of Social Capital and Social Connectedness for Resilience. We chose presenters for the workshops based on their experience, expertise, and insights into social capital, social connectedness, and resilience. Workshop panelists included individuals from the public and private sectors, from organizations involved in various resilience activities across the United States, and from the research, communications, international development, and policy communities. Virtual participants attending the workshop represented similar communities, along with government and a range of applied research institutions.

Our aim for the workshop was to identify opportunities for strengthening linkages between social capital and connectedness and hazard mitigation and resilience. To assist us in determining unmet applied research needs within the workshop theme, we asked workshop panelists to consider and address the following questions as part of their remarks:

- What is the most pressing unmet applied research need or gap in knowledge within your field of expertise that can strengthen social capital and connectedness in equitably producing community resilience?

- What are the most effective examples of social capital and connectedness in communities that you would like to see replicated to equitably enhance hazard mitigation and community resilience?

- How can communities sustain the processes, practices, and tools needed for effective and equitable social capital and connectedness in the long-term?

Workshop presentations and discussions provided rich information, offered varied perspectives, and identified significant research opportunities for the theme of Social Capital and Connectedness for Resilience. Full videos of the presentations and discussions are available on the webpage for the event.3 Biographical sketches for presenters are in Appendix C and the workshop agenda in Appendix B. In addition to the workshop, the committee joined an open session of the Resilient America Roundtable on February 19, 2021, for a discussion of this theme with roundtable members.

APPLIED RESEARCH PRIORITIES

Based on input from the workshop and committee members’ knowledge and experiences with natural hazard mitigation and resilience, we chose three applied research priorities that can inform action and collaborative priorities within the natural hazard mitigation and resilience fields:

- Inspiring Communities to Create and Sustain Social Capital and Connectedness

- Bolstering Community-Created Digital and Public Spaces

- Building Social Capital through Financial Investment Strategies

Each of these applied research priorities are discussed in detail in the following sections. At the end of each section we include specific applied research topics that we consider important for advancing these priorities.

1. Inspiring Communities to Create and Sustain Social Capital and Connectedness

Social capital and connectedness are among the most important factors in determining the resilience of a community to disasters, but more applied research is needed on how these attributes are created and sustained within communities, and on how social capital and connectedness enhance resilience. This research will naturally focus to some extent on post-disaster response, but if it is to be most effective in strengthening resilience, the balance of such research should focus on the periods well before any disasters occur. Which processes, products, and programs most effectively enhance social capital and connectedness? What incentivizes or motivates communities to act? What moves

___________________

3 Applied Research Topics for Hazard Mitigation and Resilience—Social Capital and Connectedness for Resilience—Data Gathering Workshop 1. [https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/02-25-2021/applied-research-topics-for-hazard-mitigation-and-resilience-social-capital-and-connectedness-for-resilience-data-gatheringworkshop-1], accessed March 23, 2021.

individuals to take particular steps? How can social capital and connectedness be sustained over the years and decades needed to ensure resilience against disasters? Because the creation of social capital and connectedness as network phenomena can function in discriminatory ways, how can they be best approached to maximize equity and social justice?

Recognizing the role of social capital and social connectedness for active and functioning communities highlights the role of strong, pre-existing local networks in community resilience. One such example of a current, community-led network (the Wellington Region Emergency Management Office) discussed at the workshop is provided in Box 3. At the same time, social capital needs to be better understood at multiple levels, from micro-communities to the national and international levels. For this report, the committee included insights from multiple levels in its workshop, but focused its attention on applied research opportunities at the local level. For hazard mitigation and disaster response and recovery in particular, a clearer understanding is needed of the value and possibilities for strong social capital and connectedness to reduce hazard risks and disaster loss and suffering. Enhancing links between closely related people and groups and building bridges between groups at different levels, including with their local institutions, can be critical for implementing policies, programs, and practices that engage and build social capital and connectedness. Part of the goal here is to recognize and bolster existing networks in terms of capacity strengthening (and not necessarily de novo capacity building). At the same time, we must realize that there are long-marginalized groups and people who are not part of existing networks that require careful support in order to connect into existing networks or form their own social capital and connectedness networks.

A prominent feature of community efforts to build social capital and connectedness is the frequent occurrence of a variety of co-benefits. These co-benefits may not be directly related to resilience and disaster response, but they can enhance social capital and connectedness in ways that promote resilience. A new library, park, or playground, for example, can serve multiple purposes, including that of building social cohesion or reducing violence in an area.4,5 Bridging programs that connect people and institutions, which can be inexpensive and therefore produce a high return on investment, often provide particularly large co-benefits. The creation of place-based institutional amenities, such as parks, recreation centers, and libraries, creates a great deal of benefit. However, even greater benefit comes with including person-based programs that create awareness of and bring community members into the new amenities. Study of these co-benefits can particularly support calculating the financial benefits of social capital and connectedness, as discussed below.

The forces that inspire communities to create and sustain social capital and connectedness—and the forms those activities take—vary depending on the size of a community, its geographic location, its resources, and other factors. Disadvantaged or historically under-served communities, in particular, can be subject to forces that weaken social capital and connectedness. At the same time, the pre-existing resilience, knowledge, experience, and strengths of such communities are often overlooked in community plans and programs. Such inequities have direct effects on these communities and reduce resilience capacities across all

___________________

4 Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the people: How social infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civic life. Crown, New York, NY.

5 Branas, C. C., E. South, M. C. Kondo, B. C. Hohl, P. Bourgois, D. J. Wiebe, and J. M. MacDonald (2018). Citywide cluster randomized trial to restore blighted vacant land and its effects on violence, crime, and fear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(12), 2946-2951.

communities. To capture this variety, the study of social capital and connectedness needs to occur in communities of different sizes and geographically dispersed locations, not just along the coasts or in major cities. There should be recognition that social capital and social connectedness are related constructs but not the same. Sometimes communities may experience increased social connectedness because there is less social capital or have high social capital but low social connectedness.

Creating, understanding, and sustaining social capital and connectedness works best when activities are co-initiated, led, and sustained by the community. Outside partners, such as researchers, can add value to this process, both for the community of origin and for other communities and stakeholders that may later adopt a best practice, but this implies more than simple community involvement or engagement in research. An example is how communities look at their specific needs and decide how best to meet those needs, which often involves estimations of co-benefits that only they can initially identify. While researchers should partner or serve as co-leaders in these activities, communities must have an initiating and leadership role to take ownership of both the process and its results. A useful framework to follow is community-based participatory research that has established principles of engagement between researchers and communities, including equitable partnerships in all phases of research, power-sharing, co-learning, balance between knowledge generation and intervention, mutual benefit, local relevance, iterative processes, local dissemination of any results, commitment to sustainability, and cultural humility.6 In addition, recognizing community as the unit of identity is the lead principle of community-based participatory research and taking care that a full representation of community voices is sampled, from outspoken and obvious community leaders to hyper-marginalized individuals who often tend not to speak up, is critical to success.

Should they choose to engage with outside researchers, communities need the capacity, skills, tools, and resources to bring in and work with research teams. This often involves the overt and early connection of scientists to community leaders and members and the provision of information, training, and appropriate compensation. Location can be a major factor in determining the opportunities and resources available to a community. For example, many rural areas do not have nearby universities or other research organizations with which they can partner.

An important applied research opportunity for strengthening social capital and connectedness may be the evolving field of implementation science.7 Implementation science is the study of processes and strategies that promote understanding and scalability of evidence-based research by practitioners and policymakers. In implementation science, processes are effectively treated as study outcomes in discovering how knowledge and experiences are transferred, adapted, and sustained in new locations. It determines a baseline understanding of which practices have a large enough scientific body of evidence demonstrating that they work, then examines the processes and detailed strategies that facilitate practitioners and policymakers in expanding these evidence-based programs. It also studies why programs may have initial success at one time or in one place but then fail logistically, for instance, during a roll-out period,

___________________

6 Israel, B. A., A. J. Schulz, E. A. Parker, and A. B. Becker (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173-202.

7 Lobb, R., and G. A. Colditz (2013). Implementation science and Its application to population health. Annual Review of Public Health, 34, 235-251.

in an effort to avoid future mistakes and refine future implementation processes. A prominent example is the biologic creation of an efficacious vaccine that then has slow and limited uptake in the broader population, making its mere creation insufficient for achieving broad population protection. Though implementation science is more common in fields other than disaster planning and response, it has much to offer in terms of applied research on the links between social infrastructure and resilience.

Applied research topics for Inspiring Communities to Create and Sustain Social Capital and Connectedness include

- Identify and highlight key connections, co-benefits, and value of social capital and connectedness for equitable hazard mitigation and resilience. What are the mechanisms by which strong social capital and connectedness reduce disaster suffering? What are key interventions to strengthen social capital and connectedness as well as investments to improve and best implement these interventions? Which of these interventions can be shown to provide the greatest co-benefits via their implementation?

- Document and disseminate examples of community-led approaches to building social capital and connectedness before, during, and after disaster events, while being inclusive of underrepresented and historically marginalized groups. What are well-documented examples of successes and failures for community building activities across a variety of community types (e.g., urban, rural, under-resourced)?

- Identify resources that make community building activities equitable and sustainable within a community and scalable to other settings. How should these resources be made accessible to local communities for action to strengthen capacities for resilience?

- Investigate differences in approaches to enhancing capacities for resilience in urban versus rural settings. What features of the built environment or programs are best suited for each of these environments?

2. Bolstering Community-Created Digital and Public Spaces

An increasingly prominent consideration in creating and sustaining social capital and connectedness is the use of community-created digital and public spaces. How does the use of digital and public spaces create and build community networks and social infrastructure? How can these spaces enable people to connect and self-organize before, during, and after disasters? How does information flow into digital spaces, and how is it being used or abused? Can these spaces be created in a complementary way to promote continuous access in the event that one type of space is rendered inaccessible during a disaster? Physical and digital spaces depend on other investments in physical infrastructure. Applied research on such questions is essential given that investments in the development of digital and public spaces can leverage other infrastructure investments and produce substantially greater returns relative to the costs of big ticket, non-social physical infrastructures that benefit a select few community members or are designed for very infrequent use or primarily as luxury amenities for visitors from outside communities of need.

Bolstering community-created digital and public spaces can be as simple as erecting a sign showing a former high-water mark in a public park or as complex as mounting a major social media campaign to build community knowledge, networks, and action. As with creating and sustaining social capital and connectedness, leadership by a community is critical in such efforts. When a community both articulates and acts on its goals, it creates an incentive to develop and value such spaces. Communities can then act as true partners with researchers, policymakers, and potential funders. The nature and outcomes of this co-leadership are themselves valuable subjects of research.

Digital and public spaces are used differently by people of different ages, abilities, and backgrounds, so these spaces can engage parts of the community but miss other parts. Young people, including young researchers, are more likely to act like “digital natives” and take these spaces for granted, while older people may be unfamiliar with such spaces or find them intimidating. The experiences and narratives of young people are different from those of older people, and what happens in digital spaces differs from what happens in physical spaces, although age does not necessarily determine comfort or use of digital platforms or spaces.

Understanding how groups use different spaces and platforms for connecting and communicating can inform communication and messaging before, during, and after disasters to create more effective messages and ensure that those messages are more likely to be seen at the

right time. How do older and younger people use social media to communicate and get information during disasters? What platforms predominate in different cultural communities in a region?

Digital and public spaces can have negative aspects, which also deserve study. Digital spaces can disseminate misinformation and drive activities that erode social capital and connectedness. Social hierarchies can predominate in public and private spaces, both physical and digital, thus determining who can access and use spaces and resources. Redlining, zoning, and unjust design, as well as approaches to access and control of spaces, have instituted and extended inequities in access to and use of public space. Equity and access must be considered in investments to enhance community assets and infrastructure, including ones intended for hazard mitigation and resilience, to ensure benefits for all community residents.

The connection to place, such as what people like and dislike about the physical places they occupy, has become especially important as the nature of work has changed and people, in some professions, have more freedom to choose where to live, enabled by digital technology. At the same time, the role of digital spaces and digital communities in the lives of individuals has expanded, with some people getting much of their news and information online. Many people rely on digital spaces and communities not just to learn but also to be activated and motivated. Additionally, digital spaces can foster and maintain social capital and connectedness for people displaced from common physical spaces due to hazard events. Research into the consequences of these changes is underway in many fields, including in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lessons from these investigations for how digital information and platforms drive or hinder action should inform digital communication for hazard mitigation and resilience. The committee recognizes that physical spaces are also critical to social capital and connectedness; however, the examples and topics presented, specifically in Box 4, are drawn from the workshop which focused primarily on digital spaces.

Language and storytelling are critical to spur collective action. Inspiration to take action often comes from embodying something that has happened or could happen in a convincing and compelling narrative. Storytelling has often been the glue that holds a culture together. It is related to place and groups of people, and provides a shared narrative. This has the potential to occur in digital formats (as seen on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) but often disparate stories create conflict rather than vision and connectedness. For example, the video of George Floyd’s death provided a different narrative than some public narratives of what happened. Further understanding is needed regarding how storytelling can be effectively used in a variety of arenas to build a shared culture.

Storytelling is done by those who do the remembering and those who do the telling. Consequently, individuals and communities need equitable opportunities to tell their stories and hear the stories of others for resilience that reflects and supports the history and lived experience of all community members. Engagement with local storytellers in diverse communities fosters broader opportunities for listening and seeing storytellers. It is important to know who “owns” a space and ensure that there is openness to broad audiences to access spaces, through art and performance. Box 5 provides an example of how community planning and participation in public art can be welcoming and build resilience. Much of this work will be about changing narratives that have long been in place that are based on fear and otherness. A measure of success is when storytelling becomes a part of the culture, broadly and inclusively. This might include

communities providing their own platforms for performance through cultural institutions, civic groups, and community organizations.

Building community-created digital and public spaces involves but extends well beyond communications. It is also about reimaging such spaces as places for gathering and creating social capital and connectedness. These spaces provide innovative means of stakeholder engagement, with consequences for trust, connection, relationships, resilience, and action. Digital and public spaces have become increasingly powerful tools that can serve the processes of creating and sustaining social capital and connectedness.

Applied research topics for Bolstering Community-Created Digital and Public Spaces include:

- Enhance community-led place-making to bolster social capital and connectedness. How can new digital and public spaces best be created and distributed throughout communities in ways that can be shown to enhance social capital and connectedness, and ultimately community resilience? How can community-initiated science identify the greatest community values-based returns on investment for place-making programs that avoid over-investment in luxury or large infrastructures that benefit few community members or are designed for infrequent use? How can teams be assembled that start with communities and bring together social scientists and engineers toward these ends?

- Make lessons from the “science of inspiration and narrative” accessible and useful for strengthening social capital and social connectedness. How can one make effective storytelling and construct narratives with data accessible to groups and communities in service of equitable and effective place-making in the physical and digital realms? How can one incorporate storytelling into the built environment to bolster social capital? What are lessons from Indigenous cultures where storytelling remains a key part of daily life? What lessons does science provide to inform beneficial uses of storytelling, narratives, and place-making for building social capital and connectedness? New digital mediums such as Clubhouse and others are prospering organically—how do local communities tap into these spaces and also develop cadres of social influencers that can assist with story dissemination?

- Identify approaches to enhancing co-development and ownership of shared spaces. What lessons can be shared across physical and digital place-making for building positive engagement and welcoming individuals in equitable communities that enhance social capital and connectedness for resilience?

3. Building Social Capital and Connectedness through Financial Investment Strategies

The case for the study of financial investment strategies as ways of building and sustaining social capital and connectedness rests on four observations.

- Social capital and connectedness are important assets that are subject to investment, growth, damage, and loss, and they deserve attention and investment as core aspects of resilience.

- Community-driven metrics, both qualitative and quantitative, are needed to characterize social capital and connectedness.

- Once metrics are available, social capital and connectedness can be integrated into financial risk assessment and resilience processes.

- The financial communities, including insurance companies, can be motivated to integrate social capital and connectedness into their decision-making processes when considering investments in resilience.

Today, public, private, and non-profit organizations evaluate mitigation and resilience strategies and invest in strategies that they deem to be justified to strengthen business continuity and protections for short- and long-term threats for their own businesses or their investment portfolios. In making these evaluations, organizations apply a range of methodologies to estimate risks and possible returns on investment. For example, risks can be quantified by the affected group’s size and the timescales on which effects occur. The loss of electricity to a state differs from the loss of power to a community, and loss of power for 1 day differs from loss for 1 week. The risks and consequences of low-probability, high-consequence events also need to be quantified, or in some way systematically assessed, including via qualitative approaches, despite the difficulties in doing so.

Risks can be divided into three interrelated categories for the purpose of making investment decisions. The first is the risk of direct physical impacts. The second is the risk of indirect impacts, such as loss of drinking water due to failure of other infrastructure. The third is the risk of intangible impacts, such as damage to social institutions. This third category is where social capital and connectedness primarily falls, and often constitutes the cause of the most damage and loss from natural hazards and other disasters. The second and third categories of impact are due to community connections—both between people and to critical infrastructure—and failures in any of these can affect the level of trust between the community and its institutions. The COVID-19 pandemic is an example of a disaster that did not cause direct physical damages in the same way that an earthquake can, yet the pandemic was the source of immense social and economic disruptions, and of course great damage to human health and safety, especially in the United States.

Despite the importance of social capital and connectedness in evaluating risks and resilience, these factors are rarely central to current decisions made by the investment community. Yet, communities that have been through disasters know the many ways in which social capital and connectedness affected outcomes, for better or worse. Metrics that are compatible with the tools currently used for decision-making and that can account for both the value that the community and community institutions receive from strong social capital and connectedness, and the impacts to social capital and connectedness from disasters, are needed. Increasing emphasis by individual and institutional investors on environmental, social, and

governance issues provides a framework for considering and incorporating the value of social capital and social connectedness considerations.

As with the other research topics identified by the committee, integration of additional social and community factors into financial analysis and investment decisions must be a community-led and community-driven process. If the community is not leading the conversation, investment decisions will more likely be economically uninformed, irrational, inequitable, and disconnected from community needs and values. For example, information on unbanked parts of a community or others outside of the primary economy has to come from within communities since it is typically not available from outside institutions. This evaluation of social capital and connectedness assets and gaps within communities can result in information and tools that communities can use with research institutions, policymakers, and potential funders. Researchers can also help develop models, tools, and processes that can facilitate such evaluations.

To participate as full partners with financial institutions in evaluating and implementing investments in social capital, social connectedness, and resilience, communities need access to information that is trustworthy, understandable, and relevant to be able to make effective use of this information to evaluate risks and then take action. Box 6 further expands on challenges that come with relaying this information to communities. Vulnerable communities may particularly need assistance in accessing and applying such information for action on those risks. At the same time, vulnerable and under-represented groups often carry knowledge and experience that may be critical to community resilience, but the broader community does not recognize that. The international development community has experience in combining infrastructure investments with consideration of underlying social processes, even though the process is difficult in this context as well.

Moody’s Investors Service’s move to include resilience in government bond ratings marks an important shift in this area. This was a value-driven decision that helps hold local, state, and federal governments accountable for their policies. Social impact bonds are another way to reflect the connection between resilience and investment strategies, though to date they have been more successful in large cities than in smaller communities.

By adopting a more inclusive view of risks, financial and investment organizations can motivate more comprehensive attention to and investments in resilience across the community. Research will be instrumental in creating and refining the tools that enable appropriate and sustainable investment in communities.

Applied research topics for Building Social Capital and Connectedness through Financial Investment Strategies include:

- Identify existing approaches and examples for integrating social capital considerations in to financial mechanisms. What lessons are available from instruments such as social impact bonds for valuing and strengthening social institutions and community resilience?

- Identify existing and potential metrics for social capital and social connectedness. How may impacts to social capital and connectedness from disaster events be valued and captured in risk, damage, and loss assessment? How may we measure the contributions of social capital and connectedness to community resilience in the face of hazard shocks and stresses?

- Investigate the role of strong and equitable social capital and connectedness in the success of hazard mitigation and resilience investments. How do both communities and investors value and enhance social capital and connectedness?

COMMON PRINCIPLES FOR APPLIED RESEARCH

During the process of consensus, the committee identified four common principles that extended across all of the selected applied research topics: equity, trust, community co-development and ownership, and community-level feasibility.

Equity

As one of the framing principles identified by the committee in organizing its activities, equity opportunities and concerns were considered throughout the workshop and are factors in each of the selected applied research topics. Equity is an inherently transdisciplinary issue that requires integrated research approaches. It encompasses many different indicators of health and well-being and many different population groups, including under-served, under-resourced, and historically or systemically marginalized communities. Research on inequity covers both how damaging disparities arise and how they can be reduced. It covers not just the origins of disadvantage but also the conditions that make possible positive health and life-affirming programs and practices.

Social capital and social connectedness describe the values and benefits that exist in the relationships between people, and between people and institutions, that are central to our lives and to a well-functioning and resilient society. Equity recognizes the importance of the connections and interdependencies across all of society. It also implies that the freedom and flourishing of one group cannot come at the expense of others.

Researchers must examine community resilience through an equity lens. For example, what are the opportunities and barriers for engagement of all affected groups and communities in planning processes, investment decisions, and activities designed to reduce hazard risks and strengthen capacities for resilience? How can full participation of and partnership with groups that have traditionally been excluded from these processes be ensured? Better understanding of equity issues, and how existing and new policies and structures address or exacerbate inequities, would allow governments to direct spending to the communities that need the most assistance while uniting community members around shared goals. Lessons for analyzing and addressing equity issues can also be derived from other fields, such as the environmental justice and design justice movements.

Trust

Trust is a prominent consideration throughout the applied research areas considered by the committee. Declining trust in government and civic landscapes threatens community engagement and resilience to disasters from natural hazards and other significant threats. The absence of trust between governments, businesses, nonprofit organizations, and citizens drives isolation, resentment, and a reticence to act. In contrast, though digital media and online communities exert both positive and negative influences, their capacity to build trust and cohesion must be recognized in efforts to improve disaster risk reduction and response.

Trust can be between individuals, between individuals and organizations, or between organizations. Trust differs between individuals trusting governments and individuals trusting the actions of private entities such as utilities. The private sector has to trust the public sector for public–private partnerships to succeed and vice-versa. All of these variations of trust complicate study of the issue, but such research will be essential in building understanding of social capital and connectedness with respect to disaster resilience.

As an example of the role of trust in one of the identified research topics, financial investment strategies have typically been disconnected from the infrastructure of community resilience. Accepting communities as co-leaders in developing these strategies suggests a different model of engagement in which financial actors are engaging alongside the community and making decisions while taking into consideration the input they receive from the community. Without bidirectional trust between communities and financial actors, the resulting investments may be constrained or misguided.

To earn a community’s trust, researchers must recognize their own strengths and weaknesses as well as those of the community. Conducting research with a primary sense of cultural humility allows trust and rapport to be built, enables challenges to be more readily identified within a community, and helps leaders and researchers to understand and better apply research to ultimately alleviate the individual struggles that arise during difficult situations, especially disasters. As outsiders, researchers cannot foster connectivity among community members without understanding the unique characteristics of the community within which they find themselves, which is often not their home community. By recruiting a diverse range of community members as co-leaders of research, the expertise of the community can be used to develop the best tactics with which to study and encourage greater trust and engagement. Researchers reinforce trust with communities and groups who participate in research activities by

engaging communities throughout the process, from scoping the activity to the final delivery, including by sharing the processes and results of their research with the participating communities.

Trust can be built on a small scale through pilot programs, which can also work with different vulnerable communities or with smaller geographic areas. Translating lessons from such pilots to larger scales remains a challenge in both physical and digital spaces. Trust can be enhanced through training of community, governmental, and private-sector leaders.

Trust can be both an object of study in itself and an element of other research projects. What role does trust play in social capital and connectedness? Who is able to earn trust and appropriately use and maintain it, who is not able to do this, and how is trust enhanced or degraded as a result? Who is trusted as a communicator in digital and other more local media? How can communities trust that investments made, for example, through higher utility bills actually create long-term benefits for the community and its members?

Community Co-Development and Ownership

The idea of community leadership and initiation of research, which also arises in all of the selected applied research priorities, is closely related to the “ownership” of the process, products, policies, and practices that ultimately emerge. By engaging community members as partners, working shoulder-to-shoulder with researchers, projects can best determine which types of questions community members find most compelling rather than imposing their own ideas on a population. In this way, researchers can collect better information and produce more worthwhile products, while also cultivating community ownership of a worthwhile cause. If people and communities are being asked to spend their time, and often their money, increasing resilience to shocks and stresses from natural disasters or other threats, they have to believe that what they are doing will have personal value and that they will have a continued stake in this value.

Ownership is also required for activities and investments to be sustained over time. Issues related to sustainability extend throughout the lifecycle of natural hazard mitigation and resilience. For example, a community may be inspired to take action through stories in the press about successful programs and policies in other communities, but that community needs to see the value and transferability of such actions for them to be sustained.

Ownership of communal spaces extends beyond who holds title. Feelings of ownership of a park, for instance, by a neighborhood or group can enhance communal care for that greenspace and strengthen connections through interaction and shared activities. Such ownership may also result in exclusion of other groups from otherwise public spaces, something that can be avoided via community co-development and early recognition of public ownership.

To sustain social capital and connectedness over time, researchers need to listen to community members, and research outputs must align with a community’s desires and shared purpose. Similarly, to sustain an effort over years and decades, ownership needs to extend across generations, which requires understanding how feelings about ownership vary demographically and within communities that may experience frequent out-migration, perhaps due to recurrent disasters. Community-based organizations need support and must have ownership of the tools

they co-create with researchers and policymakers if they are to sustain programs and practices, and the relationships between such resources and sustainability are important targets of research.

Community-Level Feasibility

Local governments and communities of all sizes have limited resources to address community challenges and opportunities. Reducing community vulnerability to immediate and long-term threats requires investment of time, attention, expertise, money, and political capital, which may not be available, even if the long-term value of such investments is clear. Successful design of tools, programs, and interventions to reduce risks and strengthen capacities for resilience must carefully consider the cost and complexity of implementation in various community types and settings.

The feasibility of efforts to build and sustain social capital and connectedness involves many related concepts, including applicability, affordability, practicality, portability, and justifiability. For applied research to make contributions to hazard mitigation and resilience, then guidance, tools, and examples must be accessible, workable, and economically viable at the community level.

The object of research is to produce generalizable knowledge that can be applied in more than one place. Assurance that knowledge is generalizable requires study specifically of the conditions under which it can and cannot be applied elsewhere.

CONCLUSION

Social capital refers to relationships and networks between people in a community or society and factors that facilitate community functioning, such as social norms and trust. Social connectedness encompasses the number, quality, and diversity of relationships between individuals and groups and related senses of belonging, care, value, and support. Social capital and connectedness play an important role in community functioning in day-to-day life. However, they are also often critical factors in preparing for and responding to disasters, including natural or technological hazard events, pandemics, and other threats.

Recognizing the importance of social capital and connectedness in communities, the Committee on Applied Research Topics for Hazard Mitigation and Resilience focused on applied research needs and opportunities to better understand the role of these factors. We sought to identify ways to extend and strengthen their contribution to community resilience. To inform this work, we organized a 1-day workshop to gather information and applied research topic insights from researchers. People engaged in community work and governance, experts in community building in the physical and digital spaces, and members of the private and philanthropic sectors all participated in this event.

Based on the presentations, examples, and research opportunities discussed in this workshop, we identified three applied research priorities with several underlying topics for each for Social Capital and Social Connectedness for Resilience:

-

Inspiring Communities to Create and Sustain Social Capital and Connectedness

- Identify and highlight key connections, co-benefits, and value of social capital and connectedness for equitable hazard mitigation and resilience.

-

- Document and disseminate examples of community-led approaches to building social capital and connectedness before, during, and after disaster events, while being inclusive of under-represented and historically marginalized groups.

- Identify resources that make community building activities equitable and sustainable within a community and scalable to other settings.

- Investigate differences in approaches to enhancing capacities for resilience in urban versus rural settings.

-

Bolstering Community-Created Digital and Public Spaces

- Enhance community-led place-making to bolster social capital and connectedness.

- Make lessons from the “science of inspiration and narrative” accessible and useful for strengthening social capital and social connectedness.

- Identify approaches to enhancing co-development and ownership of shared spaces.

-

Building Social Capital through Financial Investment Strategies

- Identify existing approaches and examples for integrating social capital considerations into financial mechanisms.

- Identify existing and potential metrics for social capital and social connectedness.

- Investigate the role of strong and equitable social capital and connectedness in the success of hazard mitigation and resilience investments.

This report provides examples of successful activities of each of these. It also identifies specific questions for attention by the applied research community, both within each of these topics and where they intersect. These topics can provide critical support for communities at their many intersections. For example, vibrant digital and public spaces can contribute to strong social connections. Integrating the value of social capital into financial mechanisms can incentivize community-level investments in social capital and connectedness. Social capital and connectedness are community assets and investments that need to be supported and replenished regularly over time. Finally, we identified specific applied research questions and topics that have real potential to advance these priorities.

We also identified a set of common principles for consideration and implementation of these applied research topics. These include a commitment to equity in both participation and aims of this research and outcomes; the significance of trust in research and community connections and resilience; the importance of co-development and ownership by communities; and attention to the feasibility of community-led implementation for the success of activities and interventions.

The workshop presentations and discussions demonstrated an existing basis in academic literature and experience for social capital and social connectedness’ importance for resilience. Academic and applied research is needed to collect and expand this research to inform hazard mitigation and resilience practice.

We hope to inspire researchers’ and communities’ work with this report. Research findings from these topics should bolster and extend attention and activities that build capacities

for individual and community resilience through social capital and connectedness, ultimately creating vibrant communal spaces, activities, institutions, and futures.

SELECTED REFERENCES

The following materials provide a further introduction to social capital and connectedness, as well as for some of the programs and interventions referenced in this report.

Aldrich, D. P. (2017). The importance of social capital in building community resilience. In Rethinking resilience, adaptation and transformation in a time of change (pp. 357-364). Springer, Cham, Switzerland.

Aldrich, D. P., and M. A. Meyer (2015). Social capital and community resilience. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(2), 254-269.

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design Justice. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

MacDonald J., C. Branas, and R. Stokes. (2019). Changing places: The science and art of new urban planning. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Mohatt, N. V., B. A. Hunter, S. M. Matlin, J. Golden, A. C. Evans, and J. K. Tebes (2015). From recovery-oriented care to public health: Case studies of participatory public art as a pathway to wellness for persons with behavioral health challenges. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health.

Mohatt, N. V., J. B. Singer, A. C. Evans, S. L. Matlin, J. Golden, C. Harris, C. Siciliano, G. Kiernan, M. Pelleritti, and J. K. Tebes (2013). A community’s response to suicide through public art: Stakeholder perspectives from the Finding the Light Within project. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52, 197-209.

Trebs, J. K., and S. L. Matlin (2015). [https://medicine.yale.edu/psychiatry/consultationcenter/Porch_Light_Program_Final_Evaluation_Report_Yale_June_2015_Optimized_218966_284_5_v3.pdf], accessed March 20, 2021.