3

Workshop Two, Part One

The second workshop set forth two objectives: (1) examine the same past shifts discussed in the first workshop and describe when there is advantage to synchronizing or desynchronizing rates of change with adversaries, and (2) discuss how this may change doctrine and concepts of operations (CONOPS) for future U.S. Air Force (USAF) operations as well as what general lessons may be extracted.

OPENING REMARKS

Workshop Series chair Ms. Deborah Westphal, chairman of the board, Toffler Associates, reiterated the importance of the human components of time. Workshop Two chair Gen. Gregory “Speedy” Martin (USAF, ret.), GS Martin Consulting, Inc., observed that the Department of Defense (DoD) is a platform-oriented culture—without developing the mindset for a new way to do business, it could be difficult to improve systems and fight the competition.1 He explained that the acquisition of new technologies could create near-term opportunities for people to make real change.

CONCEPTS OF OPERATIONS BEFORE PLATFORMS AND THE CHALLENGES OF CHANGE MANAGEMENT IN A DYNAMIC ENVIRONMENT

Gen. John Jumper (USAF, ret.), former Chief of Staff of the USAF, Commander of Air Combat Command, Commander of United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE), and Commander of Central Command Air Forces and the 9th USAF, commended Lt. Gen. S. Clinton Hinote for his courage in requesting this workshop series. Gen. Jumper explained that many of the ideas that proved successful during his own tenure were propelled by the real-time imperatives of war, which made it possible to cut through the red tape and bureaucratic stalling to accelerate efforts. As peer competitors reemerge and counterinsurgency becomes more complex, he asserted that now is the time to rethink how the USAF functions. Gen. Jumper noted that the USAF tends to be overly aspirational in its view of the future: It often fails to accommodate the demands of the present (i.e., next 10 years) with the promises of the future.

___________________

1 Gen. Martin suggested that workshop participants read Christian Brose’s The Kill Chain: Defending America in the Future of High-Tech Warfare (2020, Hachette Books).

Gen. Jumper commented that the USAF is at its best when it is warrior-centric—when airmen are mission-focused, and actions resonate with the “fly, fight, and win” philosophy. Morale is highest when the USAF is well prepared to respond quickly to the nation’s crises (through rapid deployments, ready and secure basing, high sortie generations, reliable precision effects, and sustained deployable operations). He emphasized that the American people do not care if platforms are manned/unmanned; where bases are located, built, and secured; or from where the precision emerges—the USAF is expected to evoke core technology competencies and deliver effects to fight and win the nation’s wars.

He acknowledged the substantial progress that the USAF has made via transition to speed, stealth, standoff, precision, and persistence. With the understanding of the critical functions that enabled this success, the USAF developed the “kill chain”: find, fix, track, target, engage, and assess. Efforts have been made to integrate the kill chain with the organizing principle “Cursor on Target,” which suggests that the kill chain could be conducted at the speed of light instead of at the speed of ownership negotiations. With modern big data technology and artificial intelligence (AI), he continued, it is possible to do predictive battlespace awareness and domain integration, use platforms as IP addresses to take advantage of battlespace position, and create self-forming and self-healing networks as functional domains—Cursor on Target could soon be a reality. Gen. Jumper explained that all of this relates to the complementary notions of concepts of employment and CONOPS. With a CONOPS, the USAF would figure out how it is going to fight before buying the things with which it plans to fight. This is simply a different way to do things that the USAF is already trained to do. Developing a CONOPS is straightforward: Start with the end result that the USAF is trying to achieve, find the most efficient way to produce that result, list the capabilities to produce the effect (without naming a program or a platform, which is how the USAF creates problems for itself), determine what capabilities are currently available or could be combined, and develop requirements to fill the gaps.

Gen. Jumper suggested that the Joint Requirements Committee reinvent itself as a Joint CONOPS team, which would facilitate the development of accurate requirements and speed up the cycle of acquisitions. He shared an anecdote from his time as the Joint Task Force Commander during Operation Vigilant Warrior (1994). He watched his troops completely reorient themselves to the war fight, which could have been avoided if daily training was run through an air tasking order (ATO) and focused on rules of engagement, and if real-time intelligence was infused into operational squadrons to be used in combat (i.e., breaking down credentials and stovepipes before the fight begins). He described this as the “warrior orientation,” in which units are always thinking about better ways to apply core competencies. The systems could be organized to reward finding better ways to use technology instead of focusing on the next replacement platform to increase capability. This is best achieved when operational staff work alongside technology staff. He referred to the Battle Labs as an example of the real and the virtual uniting to experiment with ideas and technologies. Battle Labs had a principle called Exchange Prisoners, in which the acquisition staff worked directly with the operators so that technology could be advanced within the context of the operational fighter. He explained that this approach makes it possible to improve core competencies in an evolutionary way. Battle Labs relied on an overarching plan to integrate the vertical dimension to seamlessly enable the effects of each of the functions toward a goal of simple organizing principles, such as Cursor on Target.

Gen. Jumper described several historical examples of the need to facilitate core competencies:

- During Operation Allied Force (Kosovo), the USAF was under pressure to open as many bases as possible within a limited amount of time. It eventually opened 19; however, the USAF survey teams arrived with a peacetime mentality and a lack of focus, needing 1 week to set up each base. The Contingency Response group emerged as a result, with a focus on warfighting, and was able to assess within hours what the field needed to become operational, based on the USAFE mission.

- Battlefield Airmen began as a security forces-centered way to protect airbases but expanded to include other competencies. It is critical that the USAF embraces ground activity, just as the U.S. Army does.

- During Operation Allied Force, the USAF was measuring merit for air power by how many tanks it killed. However, tanks were not the issue when Slobodan Milosevic’s troops were shooting civilians with pistols. The perspective on measuring the success of air power needed to be changed.

- Close Air Support was a capability put on the B-1 bomber, as a result of effects-based thinking. It could sit in uncontested airspace for hours with several dozen bombs and had the precision (in laser or Global

- Positioning System [GPS]) to deliver weapons reliably to within 10 feet of a target. People needed to be conditioned to understand how the effects were produced: The key is how close the bomb comes to the target, not how close the airplane comes to the ground.

- Putting the Hellfire missile on the Predator was, despite its obvious use as an effects-based capability, difficult to achieve amidst the bureaucracy. Much of the resistance was a result of ownership issues (e.g., one community having to give control to another community and not trusting that it would have the benefit of the intelligence).

All of these are CONOPS-based examples of domain integration to produce extraordinary battlefield leverage. This is achieved by thinking about how to best employ platforms in different ways and then to integrate in real time the vertical dimension, which takes into account space, cyber, air, and battlefield airmen. These lessons have been learned from real experiences in war, but when the war is over, programs of record could be established instead of letting the capabilities disappear, Gen. Jumper asserted. He concluded his presentation by emphasizing that there is much that can be done to leverage the capability that the USAF already has simply by integrating capabilities.

During the question-and-answer session, Gen. Martin reflected on a period of long-range planning and innovation in the USAF during Gen. Ronald Fogleman’s era (e.g., Battle Labs; the Joint Expeditionary Force Experiment [JEFX]; the Air and Space Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Center) that disappeared over the course of the following decade. He wondered how the USAF could instill an enduring, “pushing-the-edge-of-the-envelope” mindset. Gen. Jumper commented that the USAF has become bifurcated in war time, with leadership in Washington, DC, engaging in their own battles while airmen abroad are fighting in a war. Resources are taken from the development of core competencies and CONOPS to deal with the immediacy of war. He said that the USAF could learn a lesson from the U.S. Army by joining together and insisting on organic capability, which includes an emphasis on CONOPS and core competencies. He added that bringing Centers of Excellence together to develop ideas is inexpensive and involves only a small number of people but enables substantial leverage that would otherwise remain untapped.

Ms. Westphal wondered why there is a lack of trust within the organization (in terms of systems and capabilities) when there is a common mission with a common purpose. Gen. Jumper pointed out that issues of trust relate to issues of ownership. Because going to war is not necessarily a common mission with a common purpose, one has to be created. Ms. Westphal observed that issues of ownership and trust have to be addressed if the USAF wants to operate at the speed of light. Gen. Jumper suggested writing a CONOPS (to which everyone would agree) before a war begins that integrates the capabilities.

Ms. Westphal mentioned that the USAF has lost the insight put forth in Strategies to Tasks.2 Gen. Jumper said that the strategies at that time were budget-based (and depended on platform battles), not battlefield-oriented. The strategies needed today are one level above what was needed then, which could entail a substantial collaborative effort. He advocated for a Joint Chief of Staff, who is not distracted by the political environment, to pull an effort together for the good of the warfighter. It is also important to size the civil engineering and security forces based on an immediate need to deploy in wartime instead of based on peacetime needs, he continued.

Dr. Julie Ryan, chief executive officer, Wyndrose Technical Group, inquired about the tension between multi-domain operations and a highly political budget situation, in which everything that is funded is hard fought through Congress. Gen. Jumper replied that presenting Congress with a rational construct and a coherent story provides leverage to discuss new capabilities, especially now, as Congress seeks to project its support of the military. Gen. Martin asked how best to present that coherent story, with an emphasis on the 11 technology areas of the 2018 National Defense Strategy. Gen. Jumper observed that pieces of those technologies will fit easily into a CONOPS to engage a peer competitor or against a counterinsurgency. He added that some of these goals can be accomplished within a 10-year time frame by combining capabilities. He pointed to Joint Attack Strike Technology (JAST) as an exemplar, which was a roadmap to continuously evolve fighter technology, that allocated money for incremental advancements. Gen. Martin explained that JAST was created to understand the contributions of

___________________

2 D.E. Thaler, 1993, Strategies to Tasks: A Framework for Linking Means and Ends, RAND Corporation, https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR300.html#:~:text=Strategies%20to%20tasks%20is%20a,blind%20to%20Service%20and%20system.

different pieces of technologies to the strike technology world. If that construct still existed today, it could be a useful incubator for all of the components being added to different airplanes.

Referencing how long it took for people to determine a use for the Predator, Hon. F. Whitten Peters, senior counsel, Williams and Connolly, LLP, wondered how to convince people of the value of new technology. Gen. Jumper noted that when the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency turned the Predator over to the USAF, it came with “an artificially imposed rule” that no changes could be made for 2 years. Thus, because the Predator went into combat flawed, the pilots disliked it. Dr. Rama Chellappa, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor, Departments of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, highlighted the value of the Predator videos, which revealed a new area of research in computer vision. Gen. Jumper agreed that the Predator’s ability to precisely identify the target was game-changing, as it led to new technology for the kill chain.

Gen. Ellen Pawlikowski (USAF, ret.), independent consultant, explained that the USAF continues to struggle with a cultural issue: empowering airmen to be decision makers (e.g., to control unmanned aerial vehicles [UAVs]). Gen. Jumper commented that because technology can provide some assurance ahead of time, it is important that any “credentialed warrior” (i.e., one who has been through training) is empowered to make such decisions, with accountability remaining in the hands of leadership. Dr. Michael Yarymovych, president, Sarasota Space Associates, asked who is responsible for the effects of an effort when machines are fighting against machines. Gen. Jumper replied that legal authorities have to allow engagement in this cyber world and have to be streamlined. He said that progress in operational law and in technology may be essential before the USAF can function effectively in the future.

OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO RAPID INNOVATION AND INTEGRATION

Mr. James “Snake” Clark, Senior Executive Service (ret.); Director, Q Group, Air Force Warfighting Integration Capability (AFWIC); Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategy, Integration and Requirements; Director, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Innovations, Interoperability, Modernization and Infrastructure, explained that his job was enabled by trust and empowerment from senior leaders. All innovation is enabled by senior leadership; however, he said that the term “innovation” is often used as a soundbite by those who are risk averse and are blocking the budgetary process.

Describing the United States as a nation at war, Mr. Clark remarked that the priority has to remain on those in combat who are in harm’s way. Reflecting on the events of 9/11, Mr. Clark noted that within 26 hours of the attack on the Pentagon, a C-17 took off and picked up three Predators and three Hellfire missiles. He secured another 10 Hellfire missiles when the C-17 was 2 hours out from Redstone. Two days later, Predator 3034 was the first allied aircraft over Afghanistan after 9/11. He emphasized that Dr. James Roche and Gen. Jumper and their leadership teams enabled the initial USAF response to 9/11. Mr. Clark underscored that the C-17 flew without paperwork, and the U.S. Army provided the Hellfire missiles to the USAF without paperwork—these wartime decisions were based on trust and a willingness to take a risk.

In the 1990s, Mr. Clark was asked by Gen. Fogleman to study Predator operations in Kosovo. He explained that the Predator videos were in high demand, but few people understood how to use them. He suggested streamlining the management of Predator by assigning it to an organization that would allow it to survive and flourish. Predator was transitioned to Big Safari, a program comfortable with innovation, development, support, and risk-taking. He emphasized that this is the mindset that would most benefit the USAF; the USAF and the federal government are so risk-averse and afraid of failure that they miss opportunities to implement new capabilities. Predator is an exemplar of the positive outcomes enabled by taking a risk. Mr. Clark asserted that a key essence of innovation and success is to associate with innovative people who have a reputation for being dynamic. He added that there are people in the military and government who are by nature innovative and are willing to bet their careers on decisions, such as Col. Richard “Moody” Suter, but senior leadership has to provide top cover for those pushing the limits of the system.

Mr. Clark described his next encounter with the Predator in 1999, which had been deployed for operations in the Balkans. Concerns included collateral damage and close air support: There was no way for the Predator

to communicate to an A-10 forward air controller the exact coordinates of what it was looking at in a way that the A-10 could recognize it as a military target without civilians. However, within only 39 days of an initial call from the Chief of Staff demanding a solution, a laser designator from a U.S. Navy helicopter had been tested and deployed in combat. The war in Kosovo essentially ended 2 days after this laser was deployed. Despite this success, upon return to the United States, the staff said that the laser designators needed to be removed from the 12 aircraft because they were not part of the program of record. However, after a phone call from Gen. Jumper, it was decided that the lasers would be reinstalled on the Predators immediately. Thus, he continued, two critical elements enabled this innovation to be successful: senior officer support and money.

Mr. Clark suggested that the federal government and the warfighter embrace existing technology. Warfighters understand the technology and could be given the tools with which they are comfortable. The secrets to innovation are reputation, trust, and leadership: When the senior leaders offer support for innovative ideas, the bureaucracy tends to follow. Because innovation is a mindset, the USAF needs dynamic people who think outside of the box. He advocated for the establishment of a trust fund for innovation in the USAF and DoD so that good ideas can be explored immediately and, if successful, deployed rapidly.

During the question-and-answer session, Hon. Peters observed that a critical aspect of Mr. Clark’s experiences was the ability of the budget and programming staff to reprogram money. The money that is allocated today is often based on ideas that are 2 years old, and finding money for new ideas is extremely difficult. If the USAF does not determine how to fund current innovations, it will not be able to move forward, he continued.

Gen. Martin asked how to ensure that there are no apparent violations of authorities or legalities when advancing innovative ideas. Mr. Clark replied that with trust and top cover, it is possible to push the envelope, as long as the U.S. statute code is not violated and a person does not financially benefit from the transaction. He explained that, during his tenure, there was also back channel support on Capitol Hill for ideas that benefited the common good. Gen. Martin highlighted an important point that Big Safari fields innovative ideas and systems in a way that protects the institution.

Gen. Jumper conveyed another obstacle that had to be overcome for the Predator to be successful: Policy makers wanted to classify the Predator as a cruise missile, which would mean its use would have to be negotiated. Gen. Martin observed similar policy obstacles with the use of directed energy systems. Ms. Westphal posed a question about scaling across the organization and expressed a concern about establishing lines of funding. Mr. Clark pointed out that in addition to available money, program offices (e.g., Big Safari) with dynamic contract vehicles can obligate millions within the final hours of a fiscal year. He described the competition with programs of record that are reluctant to release any of their funds and reiterated his call for an innovation trust fund that would move money quickly. He also encouraged input from warfighters on technologies on the ground that could be improved with small changes. Gen. Pawlikowski said that the more money one spends, the more attention one will attract. Congress is disturbed when money is moved around without its knowledge, resulting in more bureaucratic processes. The world that Mr. Clark portrayed can be effective at being responsive, she continued. However, if the program grows, the ability to make changes quickly dissolves because of the amount of oversight that would be added. She described the struggle of trying to maintain trust across the full spectrum and to retain both flexibility and funding. Ms. Westphal agreed and added that even when a commercial entity has an innovation fund, within a few years it is rife with process. Mr. Clark explained that his innovations were below the amount required for reprogramming but noted that a small delta could result in a combat multiplier. He was successful at keeping Congress informed, and strong political support existed for the funding of small programs. He agreed with Gen. Pawlikowski that one has to “fly below the radar” to be successful. Programmatic flexibility creates a space in which there is enough money to test an innovative idea. Gen. Martin imparted that the worst thing a professional serving in a department of the administration can do is disrespect Congress. If Congress is shown the imperative of war (versus the aspiration of the future) and shown how the technology will save lives, supportive constituents will emerge. Gen. Martin commended Mr. Clark for the substantial difference he made for U.S. warfighters.

A CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS FOR VISUALIZING AND MAPPING THE WAY FORWARD

Gen. Tom Hobbins (USAF, ret.), Commander, USAFE; Air Force Warfighting Integrator; Commander, 12th Air Force; USAFE A-3, described three significant change cycle events in his career. First, as the USAF Commander Rear for Operation Allied Force in 1998, Gen. Hobbins had a large span of control, including the mobile air operation center, the air intelligence squadron, and the air operation squadron. His team worked on the air warfare plan for Kosovo for 1 year. The driving factor in change management for Operation Allied Force was that it was the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO’s) first combat operation. The goal was to accelerate the timeline to beddown 19 bases while meeting each nation’s air capability and desires. Although the process was not truly accelerated, it did have applicable change cycle features. During the 3-month buildup to the force deployment, the key indicators for change included a hands-on supreme allied commander Europe (SACEUR) overwatch, a reluctance for NATO involvement, some senior military and national leaders’ beliefs that it would be difficult politically, and the belief that air could not operate alone. Failure was not an option, but low confidence increased skepticism, he continued. A convincing air warfare plan that ensured low collateral damage was needed. Top intelligence professionals and top weapons school targeteers, as well as teams from base infrastructure developers, provided the confidence that the NATO staff needed: rigor and analytics with visualizations in detailed timelines for the logistical support, weapons, vocations, training, fighter beddown, communication, and command and control (C2) channels. Establishing trust and confidence in a crisis action team (CAT) and sharing Gen. Jumper’s video conferences daily with SACEUR and his staff were key to designing, planning, and implementing as well as for communications, Gen. Hobbins explained. He emphasized the value of critical thinking, asking questions, and establishing an open environment on the CAT floor: No one feared sharing new information with leadership. USAFE leadership and trusted relationships as well as the use of the daily visualizations of complex aircraft and weapons flow convinced SACEUR and his staff that NATO and the U.S. weapons match would be realized, that expectations for performance would succeed, and that a NATO-U.S. team would succeed. Obstacles included a nonexistent C2 network at deploying bases, credible Serbian surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), and a lack of precision-guided-munition certified or SAM-evading gear on the NATO aircraft. However, political will helped to solidify millions of tons of logistics weapons and aircraft positioning equipment for many bases that had incomplete infrastructure. It took a unified team with a unified and unfailing leadership to overcome these obstacles with innovation and dedication to a single objective. He asserted that the change in NATO support was managed with the full-time connectivity of the Air Force Office of Scientific Research staff and the initially co-located Air Operations Center.

Second, Gen. Hobbins experienced a change cycle when he became the first warfighting integrator. As an F-15 pilot who was put in a position held almost universally by career communicators, he knew very little about the communications business other than C2. This was another role in which Gen. Hobbins relied on critical thinking skills to drive change. With several “equivocators” on his staff, he would ask penetrating questions to drive the organization’s knowledge beyond that of the equivocators, who intimidated younger officers. Now these officers, who had always been put down for their ideas, had to find answers to Gen. Hobbins’s questions. They were expanding their knowledge, and their intellectual prowess soon surpassed that of the equivocators. With knowledge of the functional areas, Gen. Hobbins was able to determine what changes needed to be made. Policy, logistics, and operations were separate and dysfunctional; once those were less disjointed, it became possible to operate more effectively. He asserted that leaders facing change cycles have to make a commitment to understand things at a working level. He again used visualizations to manage change and make the complex “what” and “why” understandable for large industry and government audiences. As the warfighting integrator, he was asked to solve the top shortfall from a 2004 integrated Capabilities Review and Risk Assessment (CRRA), which was the need for a self-forming, self-healing global information grid (i.e., the ability to communicate data/voice anywhere in the world; and establish, connect, and maintain that communication for air, space, land, and sea) by 2005. The network needed to be ubiquitous enough to self-correct and self-heal when disruptions and departure of various nodes occurred. The most important aspect of this change cycle (how to determine what to change for the future) was understanding the current state, which was achieved by creating an understandable visualization of this complex problem. However, before creating the visualization, the disruptive technology had to be conceived. Key elements

had to be identified and defined for the architecture to become self-forming and self-healing: Global network connectivity was first, network-enabled platforms and weapons were second, fused intelligence was third, and real-time C2 situational awareness was fourth. He emphasized the time, commitment, and research needed to create a visual depiction of this complex problem. He first worked on the ideal state, which has no constraints, and then moved to the future state, which falls between the current and ideal states. The future state was not without challenges, but it contained something workable. He explained that the solution was initially represented in the Program Objective Memorandum, and it was incorrectly assumed that the technology would function. The visualization served as a way to understand an expectation of performance and how the change could be managed as a guide for what to defend in the panels and where to spend the extra end-of-the-year fallout dollars. Gen. Hobbins had to present the problem and the way forward to commercial audiences: The visualizations revealed the need for a single common data IP router in the sky to integrate all service message standards and exchange them. A joint capability technology demonstration (JCTD) for this Battlefield Air Communication Node was then executed. JCTDs could be in the “acquisition HOV lane” for capability because they originate from a combatant command integrated priority list, he explained. The JEFX was the setting for a performance expectation, and it demonstrated how change could be managed. At the time, a rapid acquisition program contained funds authorized by the Chief for new programs or initiatives. Five of the seven JEFX 02 experiments went to the second Gulf War directly from the exercise. He described exercise innovations as important; it is crucial to follow-through on change cycle work. He encouraged AFWIC to use this process of visualization for joint all-domain command and control (JADC2).

Third, Gen. Hobbins described the evolution of the USAF Smart Operations for the 21st Century (AFSO 21), which introduced an initiative to help fund a response to the USAF’s strategic need to modernize and recapitalize its aging aircraft and equipment. The main indicators for change were antiquated, stovepiped processes, which contributed to widespread inefficiencies throughout the USAF (from administration to production). There was also an impetus from industry in lean engineering, and the USAF had suffered from long work-week hours, wasted inventory, and non-enterprise buying. The vision for AFSO 21 was to establish a continuous process improvement environment whereby all airmen were actively eliminating waste and continuously improving processes centered around core missions. Gen. Hobbins defined five desired effects: (1) increased productivity of the airmen, (2) increased availability of critical assets, (3) improved response time and decision-making agility, (4) sustained safe and reliable operations, and (5) improved energy efficiency. The Eight-Step Problem-Solving Method was used to achieve continuous process improvement: (1) clarify, validate, and break down the problem; (2) identify performance gaps; (3) set improvement targets; (4) determine root causes; (5) develop countermeasures; (6) see countermeasures through; (7) confirm results and processes; and (8) standardize successful processes.3 Following these eight steps ensures that actions lead to desired results, he explained, with an absolute minimum of wasted effort. Gen. Hobbins noted that the change was managed with upper reporting on savings examples. He encouraged and rewarded base efforts to look for low-hanging fruit, advertised wins, performed value stream mapping, eliminated non-value-added processes, and gained manpower time. Personal dividends were gained, overtime was cut, and money was saved. Secretary Wynne had withheld 2.5 percent of the Major Commands’ (MAJCOMs’) discretionary funds; after AFSO 21, 1 percent was returned to the MAJCOMs. Gen. Hobbins described the effort as a success and noted that it has now been incorporated into the Professional Military Education program.

During the question-and-answer session, Gen. Martin observed that an infrastructure of people is producing the foundation that leads to improvements in the warfighting equipment. If the infrastructure is not modernized, then improvements for the warfighter cannot be made. He reiterated Gen. Hobbins’ point that the emphasis extends beyond hardware, production, and equipment; there are other places where change could lead to overall institutional success. Gen. Jumper perceived that creating these domains entailed the development of meshed networks. This enabled the automatic passing of target information, which is critical to the notion of a CONOPS that vertically integrates the information from ground, to air, to space, to cyber. Gen. Hobbins mentioned that today’s problems revolve around data—how to move data from one place to another and how to make data authoritative. The Joint Force Commander’s success could be enabled by expansive and instantaneous access to information. Gen. Martin

___________________

3 U.S. Air Force, 2014, “What are Air Force Smart Operations for the 21st Century (AFSO 21)?,” CMSgt. Donald K. Smith, USAF, January 27, https://www.127wg.ang.af.mil/Media/Commentaries/Display/Article/865961/what-are-air-force-smart-operations-for-the-21st-century-afso-21.

asked about the USAF’s ability to prototype, test, and implement on a continual and rapid basis. Gen. Hobbins responded that although experimentation is important, the USAF may not be conducting the right types of experiments to achieve JADC2.

Dr. Ryan emphasized the value of visualization to make things more accessible for varied audiences. She asked about efforts to teach people how to do visualization appropriately to increase communication effectiveness and the ability to recognize opportunities for innovation. Gen. Hobbins replied that visualization means using one picture for demonstration; there is no single methodology. For example, it involves trial and error as well as collaboration with graphics experts and cross-functional teams. He noted that these skills could be taught in universities. Gen. Jumper added that when visualization becomes too complicated for one image, it is useful to take people into a virtual world to demonstrate the power of the capabilities; the USAF does not use virtual reality as much as it could. Gen. Martin noted that visualization is critical not only for basic understanding but also for operational training.

INTERAGENCY COORDINATION FOR QUICK AND DECISIVE ACTION

Lt. Gen. John “Soup” Campbell (USAF, ret.), associate director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for Military Support; vice director of the Defense Information Systems Agency; and deputy director for Operations, Joint Staff, shared a case study on Space Based Radar (SBR), a program to put radar satellites in orbit that would provide products for the intelligence community (IC) and the DoD warfighter. In 2004, the Under Secretary of the USAF and the Director of the National Reconnaissance Office directed a review of the SBR program to attempt to resolve issues that had stalled activity. Concerns surfaced around who would “own” the system (i.e., IC or DoD) and who would decide on the tasking, priorities, and analysis and dissemination of products. There were also issues with design tradeoffs (e.g., mission optimization, constellation size, location, orbits), technology challenges (e.g., power, data infrastructure, antennas, processing), and cost and competition with other space programs. He explained that the review group came to several conclusions: (1) SBR was important to national security for both IC and DoD because it was the only all-weather, day/night persistent synthetic aperture radar and ground moving target indication capability to look into denied areas where aircraft could not go. (2) Only one national program to provide radar products from space was affordable, and DoD and IC leadership would have to determine how to prioritize and task it. (3) A constellation reference architecture was needed, which was a tradeoff between cost and capability (i.e., a 9-ball constellation in low Earth orbit, with an estimated life cycle cost of $25 billion). (4) Risk/cost reduction and technology demonstration efforts were needed. (5) A name change (from “Space Based Radar” to “Space Radar”) was needed to signal the status as the only space radar effort for the nation. However, the program was terminated in 2007, and Lt. Gen. Campbell conveyed the following lessons learned: The environment at the time was not favorable to another expensive space program; the technology was risky and the cost estimates were judged to be unrealistically low; and DoD and IC failed to agree how to support a single system that could serve both communities, even if sub-optimally. He described this as an example of ineffective interagency cooperation.

Lt. Gen. Campbell shared another case study, from 2001, on the Interagency Development of the Armed Predator. In summer 2000, a USAF Predator Remotely Piloted Aircraft located and took video of Osama bin Laden on Tarnak Farms. Because people were frustrated that they had located him but were unable to take action, this led to the creation of a program to arm the Predator. The hardware development began in February 2001, and the new Predator was in place in theater by 9/11. It became a key capability in Operation Enduring Freedom and became a model that was widely adopted, persisting as one of the best weapons for a variety of scenarios. He highlighted this as an example of effective interagency cooperation and conveyed the following lessons learned: The time was right for a unified interagency effort—with an operational need and an opportunity, USAF and CIA leadership support, and National Security Council support. The leadership provided the organizational top cover so that talented action officers could identify and solve problems. A few key players made a difference, he explained, and continuous improvement increased the effectiveness of the system, enhancing the warhead, ROVER, and video sharing. He added that although video feeds can be useful, they are liable to create a “3,000-mile screwdriver.” In some cases, overclassification of data caused confusion and detracted from success. The command relationships between DoD and the CIA were positive, owing to trust, confidence, and low visibility.

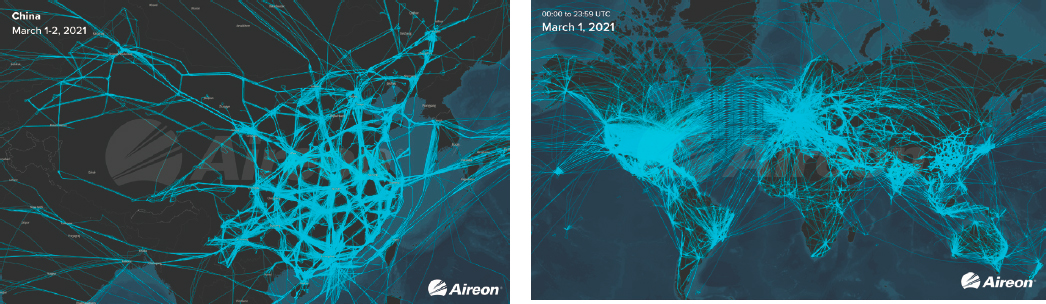

Lt. Gen. Campbell shared a final case study on Iridium Hosted Payloads from 2007 until 2012 as an example of a relationship between industry and the government and the power of innovation. He explained that Iridium Satellite was a Motorola initiative in the late 1990s to build a constellation of low Earth orbit satellites that would cover 100 percent of the globe. It provided low-latency voice and data service. “Iridium 1.0,” the original Motorola endeavor, was a technological success but a business failure, declaring bankruptcy in 2000. A consortium of investors rescued the effort, which was anchored by a DoD service contract to continue operations. “Iridium 2.0”/Iridium Communications was a commercial success, which went public in 2007 and committed to a $3 billion constellation recapitalization, Iridium Next (I-Next). To leverage the power of the constellation architecture, he continued, the I-Next design incorporated space for 50 kg of hosted payload space with appropriate power and data allowances. Iridium believed that this would be attractive to the U.S. government for a variety of missions requiring global coverage and low latency and saw hosting fees and data revenue as an important but not essential part of the business plan. However, after no U.S. government mission was signed, Iridium developed its own payload and business, Aireon—which is jointly owned by Iridium and the Canadian Airspace Control Agency Nav Canada—to provide automatic dependent surveillance–broadcast (ADS-B) collection from space, revolutionizing global Air Traffic Control (see Figure 3.1). ADS-B leverages the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA’s) NextGen plan to modernize air traffic control; enables active air traffic control over oceans, polar regions, and undeveloped areas; and provides other powerful global situational awareness capabilities. The constellation was completed in the first quarter of January 2019, and the estimated Aireon revenue for 2020 (pre-COVID-19) was $100 million. The ADS-B messages have extensive data elements that provide much more information than the location of the aircraft—for example, quality indicators such as for GPS performance. All data are archived, which can provide a historical perspective on air accident investigations, for instance. He indicated that many lessons have been learned from the Iridium Hosted Payloads: First, it is difficult to challenge conventional wisdom (e.g., Iridium went bankrupt once already). Second, key individuals can enable or prevent action. Third, it is difficult to convince the U.S. government to take the time and devote the talent to assess a business plan, particularly if it is counterintuitive. Fourth, the U.S. government is so risk-averse that it often misses opportunities to leverage commercial innovation; however, the commercial environment has more room for risk-taking because the only penalty for failure is bankruptcy. Fifth, commercial development cycles run so much faster than those of the U.S. government that it is very difficult to synchronize. The USAF is working to create an enterprise that works at commercial speed and can take advantage of opportunities to leverage innovation. He added that predictability and long-term stability encourage investment, and imagination and innovation could result in national assets.

During the question-and-answer session, Gen. Martin reiterated that the environment surrounding technology development matters. He said that the work on the Predator paved the way for additional collaborative efforts, and such relationships have an opportunity for incubation. Gen. Pawlikowski expressed her frustration about the then Space and Missile Systems Commander’s failure to convince anyone to buy-in to the hosted payload

approach. Lt. Gen. Campbell agreed that recruiting people to understand the business plan was a challenge. Dr. Chellappa wondered if other countries have similar problems to those of the United States. Lt. Gen. Campbell reiterated that Canada realized immediately the power to control traffic across the poles and increase efficiency. Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore have joined, but, to his knowledge, the FAA is still not a partner. Ms. Westphal wondered about lessons learned that would relate to the commercialization of information systems. Lt. Gen. Campbell responded that multi-thousand-satellite low Earth orbit constellations, such as Starlink, present enormous opportunity. Ms. Westphal questioned whether, as the USAF looks forward to quantum mechanics, AI, and machine learning, it will end up in the same situation as when it was commercializing space. Dr. Yarymovych described constellations with thousands of satellites as “the internet of the sky.” However, most of Eastern Russia does not have cellular networks installed, thus decreasing Russia’s information dominance.

Gen. Jumper mentioned that the personalities in the Office of the Secretary of Defense made a positive difference in the early 2000s. He added that if one can present the migration story about how to operationalize these capabilities (and how they will progress over time in a fiscally responsible way) so that leadership can anticipate what will happen next, it would be difficult for them to ignore a well thought out plan. Ms. Westphal emphasized that focusing on how a technology will be used and whether it will increase speed could sustain the momentum for technology development. Gen. Martin noted that all of the nation’s aspirations are aligned; a strategy that allocates resources would put the USAF on a path to success. Ms. Westphal advocated for the warfighter mentality to lead the technologist (instead of the technologist leading the warfighter), and Gen. Martin added that this confusion of mindset is accelerated by a fear of falling behind.

TEAMING AMONG THE OPERATOR, ENGINEERS, DEVELOPERS, AND TESTERS FOR RAPID INSERTION OF CRITICAL CAPABILITIES

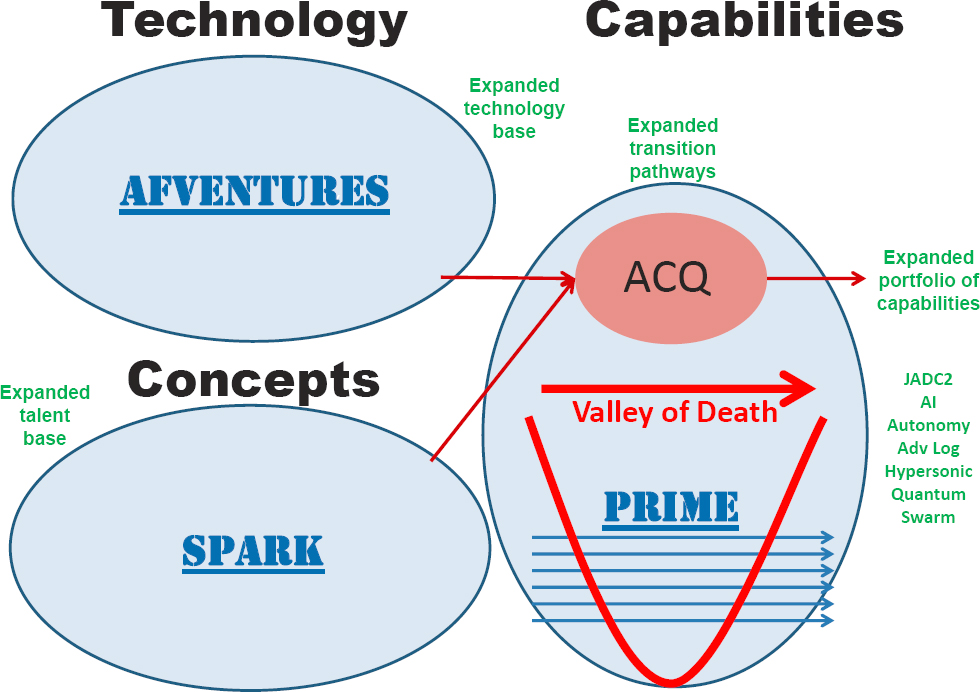

Col. Nathan “VI-DOF” Diller, AFWERX Director, Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL)/RG, explained that in May 2020, Gen. Stephen Wilson signed a memo outlining that AFWERX “1.0” would transition to Air Force Materiel Command to increase its capability development role—specifically by moving into AFRL, where the organized train and equip functions are maintained, but still preserving a direct report to the service acquisition executive for purposes of strategy approval execution direction (similar to a program executive officer [PEO]). He described the goal of AFWERX to be a preferred partner for commercial technology innovation by expanding the defense industrial base and broadening the network of airmen creating innovative concepts to field high-value capabilities rapidly. Expanding the portfolio of capabilities in a timely fashion (e.g., in AI, autonomy, advanced logistics, hypersonics, and quantum) and increasing the gross domestic product could create a new acquisition process. The objective is to achieve this expanded portfolio (both commercial and military capabilities) while allowing both growth in prosperity and in security of the nation (see Figure 3.2).

AFWERX is comprised of AFVentures, Spark, and Agility Prime, which develop vast technology, talent, and transition partnerships for accelerated, affordable, and agile commercial and military capabilities. Col. Diller defined these three lines of AFWERX effort as follows:

- AFVentures—Emphasizes the use of small business contracts to expand the industrial base and leverage commercial technology. Today, the research and development investment in DoD is less than 20 percent of what is available to the entire American innovation ecosystem. AFVentures explores ways to harness the remaining 80 percent in a way that is helpful to both industry and DoD and to broaden new technologies (e.g., 5G, three-dimensional printing, commercial space, and robotics).

- Spark—Allows for innovation on the edge. If the talent base is expanded, it becomes possible to understand how to absorb the technology so that it can be used instead of remaining on the shelf. A broad group of airmen across diverse backgrounds in different career fields is key.

- Agility Prime—Serves as the transition agent between the technology from AFVentures and the innovative ideas from the airmen in Spark to create alternative approaches to crossing the valley of death (e.g., electric vertical takeoff and landing [eVTOL] and the operationalization of that commercial capability for dual use),

- while preserving military lives and managing the budget. It also comprises certification of air readiness (e.g., ATOs for software) and new methods for budget cycles and contracting.

The objectives of Agility Prime (the first in a series of Prime programs) are strategic (preparing the industrial base to provide near-term savings), process-focused (thinking differently about acquisition and airpower as well as finding a different process for transitions), and product-intensive (fielding VTOL capability in FY23). Col. Diller noted that the National Defense Strategy describes a need for distributed logistics and the ability to preserve logistics under attack. There is an impetus to take emerging commercial opportunity and turn it into military capability, he continued. Col. Diller described the Organic Resupply Bus (ORB), which is a concept that drives value with a maintainable modular mobile electric/hybrid platform. Current legacy VTOL is expensive; commercial market involvement could make eVTOL less expensive across the board. The reduced cost makes it possible to take a hybrid or electric commercial investment coupled with an investment in the small UAV industry with sensors and achieve ORB in a way that could eliminate the USAF’s initial capability development delays or create a surge capacity (similar to the automobile industry’s efforts).

Twenty different use cases across five MAJCOMs are under way, he explained, including those based on personnel recovery, point-to-point logistics, and defense support to civil authorities. For example, the ORBs exploit an area between the fixed wing and the rotary wing, where it is possible to drive down the energy and operating costs required and still realize some of the benefits of the vertical craft. He said that the rotorcraft would

not immediately be supplanted but providing an additional capability across the portfolio would create an overall reduction in cost. There is hope that in using this approach the missteps that happen in the small unmanned aircraft systems industry can be avoided while taking advantage of the $1.5 trillion market with relatively low investment in risk reduction. AFWERX has identified a need to spend energy on the supply chain, workforce, culture, and infrastructure through this interwoven approach to academia, industry, and government.

He noted that speed is predicated on early partnerships among the PEO for mobility, AFRL, AFWERX, and AFWIC. Partnering with industry for an affordable learning campaign includes (1) a reduction of the technical risk, by providing access to military ranges and testing; (2) a decrease in the regulatory risk, by providing airworthiness to companies so they can generate data and revenue to decrease financial risk and by giving the USAF early insights into the nontraditional actors; and (3) eventually the fielding of a capability, while providing risk reduction across industry. Contracting outputs include leveraging small business innovation research (SBIR) grants to bridge the valley of death with the budgeting that is offered by the larger SBIR contracts and to create a 5-year opening using Other Transaction Authorities for companies of all sizes. He described the response from industry as positive, with the involvement of more than 17 companies (many of which are from Silicon Valley) across the innovation ecosystem in eVTOL. Col. Diller stated that the requirements development process could be thought about differently: using existing technology and finding a match to that technology with novel approaches to analytics through tradespace analysis, and developing the ability to look across multiple missions and multiple stakeholders to identify resilience across multiple futures. The use of these different contracting approaches in combination with testing infrastructure and air readiness could lead to the realization of initial operational capability by FY23.

During the question-and-answer session, Gen. Martin inquired about Agility Prime’s follow-on efforts. Col. Diller noted that several are being discussed, with one scheduled for release in December 2020. He explained that a follow-on program could emphasize commercial viability, military utility, a value proposition for DoD, a reduction of technical and regulatory risk, or a partnership with investors. Areas of focus could include autonomy and AI, quantum technologies, or space. Dr. William Powers, retired vice president of research, Ford Motor Company, asked about the value of commercial-off-the-shelf, and Col. Diller said that AFWERX has spent time working with industry to consider how to accelerate its standards to conform to military standards.

Hon. Peters wondered whether there are people who know how to assess the air worthiness of eVTOL-enabled vehicles or if that industry will have to be developed concurrently. Col. Diller replied that connective tissue across the bureaucracy helps to accelerate this process, and he described the intention to expand the network of partners (e.g., the National Aeronautics and Space Administration [NASA] and FAA) to leverage taxpayer investment. Dr. Yarymovych asked how the traffic created by all of these vertical, commercial, and military objects will be managed. Col. Diller commented that NASA has been working on unmanned traffic management for nearly a decade. Other companies are developing sensors, secure communications, AI, and high-speed computing for traffic management. He described this as a key area of interest for AFWERX as it thinks about C2 on the edge and in contested environments.

Dr. Brendan Godfrey, visiting senior research scientist, University of Maryland, observed that being situated within AFRL could decrease AFWERX’s opportunity for impact; he wondered what relationships are in place to sustain AFWERX. Col. Diller explained that he has briefed approximately 30 Capitol Hill staffers and is under the impression that AFWERX has congressional support. Gen. Arnold Bunch has expressed his commitment as well. Captains and majors are already thinking about how they will use the new technologies, and the USAF Academy is offering academic programs in these technologies. Most importantly, the National Defense Strategy commands the creation of such partnerships and consideration for distributed logistics.

Gen. Martin commented that a CONOPS that discusses mechanisms and a process for distribution, from a logistics perspective, would be beneficial. Col. Diller replied that although this would depend on the use case, there are 3 key platform form factors under consideration across the 20 use cases (i.e., 3–8 passenger, 1–2 passenger, and unmanned), each with a different weight and range. Scenarios are being developed, for example, to explore the ability to deploy quickly from sanctuary to contested areas. When thinking about creating sensors for communication on the edge, and the enabling capability they provide, the perspective transitions from a mundane local base defense, to an arranged support, to a significant level of guard interest in a discommission, to even some use cases that are relevant for some of the high-end fights.

Hon. Peters asked about battery technology, and Col. Diller responded that current ranges are approximately 200 watt-hours per kilogram. Looking to the future, lithium ion technology offers the potential for growth at 5–8 percent per year in battery energy density. The AFWERX Energy Challenge will consider other approaches to energy, he explained. Gen. Martin inquired about the original conception for AFWERX as compared to its current status. Col. Diller reiterated that a major shift occurred in May 2020, which rethinks American manufacturing in a new age of “software meeting hardware”—the USAF is helping to move this forward.

OPEN DISCUSSION

Dr. Richard Hallion, senior adviser, Science and Technology Policy Institute, shared his thoughts on the issue of stability (see Appendix D for further details). He explained that stability is perceived as a natural good and a desirable state or end-state (e.g., stable societies; domestic/foreign policies; international security environment; economic systems, structures, and growth; and family units). A commonly expressed goal is the restoration of stability, as if stability is somehow inherent. Furthermore, the notion of restoring stability is emphasized in academic training (e.g., political science, economics, law, sociology, and international affairs). However, he questioned whether stability even exists. He pondered whether stability should be maintained or managed. According to Dr. Hallion, at no point in human history has there been a stable international order. He defined history as the working of people over time; since people are dynamic, observant, reactive, thoughtful, and active, they reflect uncertainty in their own existence. Therefore, he continued, history is a record of human uncertainty. He explained that the uncertainty of the general human condition promotes instability. Societies and social constructs, whether they are military organizations or government organizations, are thus inherently unstable, he asserted. The only certainty is the continuation of uncertainty, and stability is invariably uncertain, transitory, and illusory. Studying the behavior of organizations in this environment, one can draw on flight control theory: Dr. Hallion stated that organizations exhibit phugoid behavior in the face of uncertainty including long- and short-range periodicity, reflecting political leadership inputs; poorly damped pilot-induced oscillation, or PIO behavior, which logically reflects human-in-the-loop/human friction issues; the potential of sudden catastrophic “departures” from unexpected external inputs; and the desire for active control instead of mere stability augmentation. He referred to the First World War, when people ignored conditions and thought they were living in a stable, unchanging system (as the European leadership did at that time), which led to catastrophic departures. He asserted that the world is still experiencing the cascading effects of World War I. However, significant achievements can still be made in such times. For example, in the 20th century, the world has experienced revolutions in aerospace, medicine, propulsion, knowledge, and computation. Because such things can induce their own uncertainties, time and time cycle mastery become critical, he continued. Societies have failed to do so because individuals always think they have more time than they really have, and those societies rapidly fall from preeminence. He emphasized the danger of falling victim to an illusory ephemeral stability approach that leads to such a temporal distortion. Dr. Hallion said that the natural norm of society is dynamic instability. Conflict is an unavoidable manifestation of this; it can be controlled or maintained but cannot be prevented or eliminated. He explained that accelerations in scientific and technological change and the investments made forced by military necessity produce further uncertainties by overturning normative assumptions of what stability is and what the world would be and continues to be. Those uncertainties drive further dynamic instability, which confirms that when trying to deal with stability in an organizational structure or in society it is neither a given nor a natural state; it has to be actively imposed. Gen. Martin pointed out the benefits of strong leadership and a new tool set to confront the USAF ‘s environment of instability.

Mr. David Markham, managing director, Waywest Advisors, described his involvement with service members and members of industry in several tabletop wargames related to China’s long-term strategy with the United States (see Appendix E for further details). He explained that China’s economy has grown, and it has taken a substantial position in U.S. assets in terms of property, real estate, and industrial goods—a sizeable position in the supply chain for the United States. These strategic initiatives have not gotten into the military per se, but they have permeated the domestic world. For example, the United States turned to China for personal protective equipment at the onset of COVID-19, and many pharmaceuticals used in the United States are manufactured in China, exposing vulnerabilities in the supply chain. Another issue, he continued, relates to prompt global strike (i.e., removing

the warhead on a strategic weapon and replacing it with something that delivers a fine effect without any high explosive at that speed). Mr. Markham said that repurposing a weapon system for long-range standoff effects has been a possibility for a long time. There are many innovations of note owing to a change in policy positions. He described an ongoing challenge with the range of aircraft versus the distance in which China could project force and effects. He added that space is now a warfare domain, and improved effects are available when combining satellites with other weapons for C2, precision navigation, indications, and warning. The United States is now trying to fight and win a war in space while trying to fight and win in other domains, which is a degree of complexity that is often misunderstood. Given that China is working on cyber systems destruction warfare, there are several avenues to the civil world (e.g., power grids, food chain, and supplies). He asserted that the United States has to be “whole-network aware” as it thinks about conflict with China.