1

Workshop One, Part One

The first workshop set forth two objectives: (1) discuss how the U.S. Air Force (USAF) adjusted its capabilities—in terms of systems, doctrine, training, etc.—to selected past shifts caused by changes in operational timing; and (2) catalogue what was changed through a discussion of timing, sequence, effectiveness, limitations, lessons learned, and other attributes of value.

OPENING REMARKS

As the first day of the workshop series opened, Lt. Gen. Ted Bowlds (USAF, ret.), chief technology officer, IAI North America, explained that a team’s size dictates the speed at which a new capability is introduced and implanted into a warfighting unit. Small teams can do acquisitions faster than large teams because their decision process becomes streamlined; thus, it is difficult for an organization as large as the USAF to adapt to rapid change.

Gen. Gregory “Speedy” Martin (USAF, ret.), GS Martin Consulting, Inc., observed that 80 percent of major transformation fails in the execution stage, often because the workforce is not aligned with a company’s vision for the future. Many organizations think that if they design a strategy and implement it, everyone will follow and the mission will be a success. While this may be feasible with an organization of 10 people, he continued, several obstacles arise when using that approach with an organization of 10,000 people. Lt. Gen. Bowlds added that the support of senior leaders enables small, focused efforts to move rapidly to development. When there are too many people trying to adopt a technology, he continued, it takes a substantial amount of time to navigate bureaucratic processes and increase buy-in. Workshop Series chair Ms. Deborah Westphal, chairman of the board, Toffler Associates, referenced a 2016 article in Fortune,1 in which then-CEO of the Corporate Executive Board described a survey of 25,000 people from various organizations. The survey revealed that the integration of information and communication technology across enterprises was decreasing the speed of decision making, owing to the burdensome layers of connections that had to be made and the number of people involved in decision making (e.g., 60 percent of those surveyed had to interface with at least 10 people to make a decision, and half of those people had to interface with 20 others to make a decision).

___________________

1 T. Monahan, 2016, “The Hard Evidence: Business is Slowing Down,” Fortune, January 28, https://fortune.com/2016/01/28/businessdecision-making-project-management/.

Dr. Rama Chellappa, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor, Departments of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, emphasized the need to consider the complexity of the USAF’s technology when discussing the speed of its integration and noted that the complications and sophistications of work are different even within each of the services (e.g., getting a plane in the air versus building a ship). Hon. F. Whitten Peters, senior counsel, Williams and Connolly, LLP, introduced another challenge related to rapid change: Everyone in the USAF has a “day job” that has to be completed, and the technology often moves faster than the people and training available to shepherd it (e.g., in the case of the Predator, training fell well behind the need). He observed that other tasks have to be postponed in order for people to focus on the development of revolutionary technology.

Ms. Westphal wondered whether the USAF concentrates more on its products and services than its people. Her impression was that the USAF relies on a “plug and play” approach: It sets a structure, bureaucracy, and tools and merely “plugs in” the people to accomplish tasks. She suggested that the USAF consider utilizing the uniqueness of individuals instead, by making people the primary focus and wrapping the technological advances around them. Gen. Martin explained that the U.S. Army has a clear set of requirements for each person performing a duty from a mission-essential task list. This illuminates the value of individual people: If one person is removed, a mission can fail. He underscored the value of listening to people as soon as critical problems arise, instead of prioritizing systems.

TIME IN PLANNING AND EXECUTING COMBAT OPERATIONS

Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula (USAF, ret.), former Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR); former Pacific Air Forces Vice Commander; former Commander, Kenney Warfighting Headquarters and Combined/Joint Task Force (JTF) Operation Northern Watch; dean, Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies; and senior military scholar, Center for Character and Leadership Development, USAF Academy, described several examples of rapid adaptation during his experiences in major theater war and disaster response.

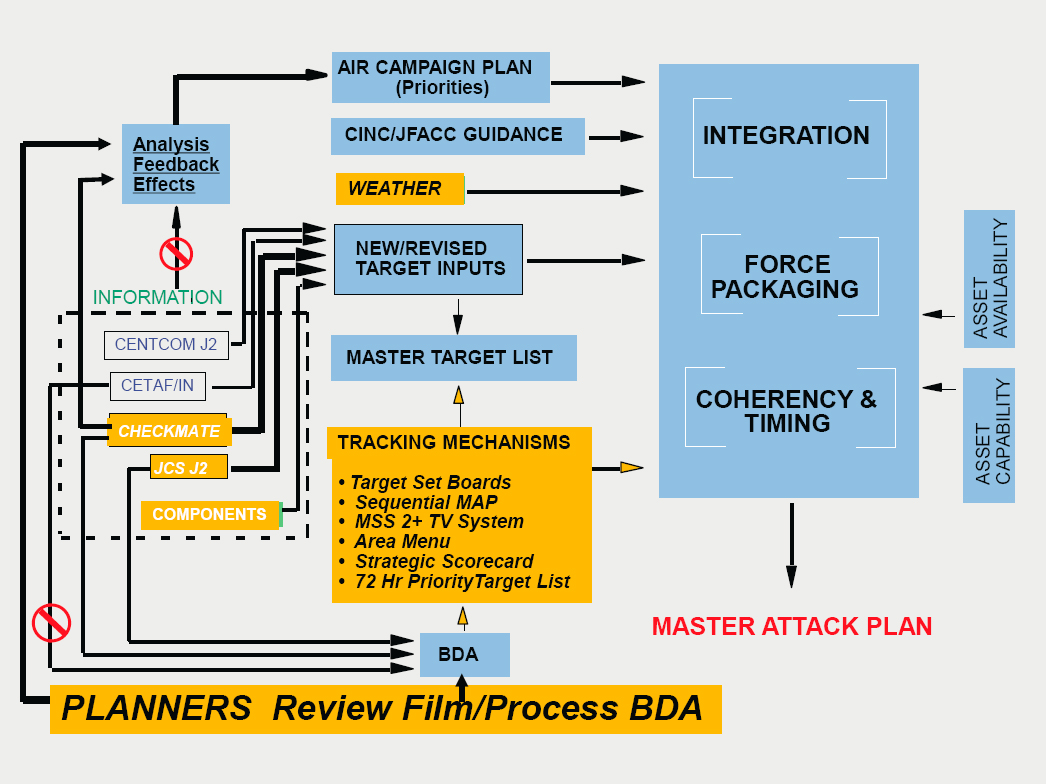

Lt. Gen. Deptula explained that it took 6 months to plan the first day’s strikes for Operation Desert Storm (1991), which included 150 targets within a 24-hour period (more than in 1942 and 1943 combined over central Europe). A “Master Attack Plan” was derived from an understanding of a series of weapons systems and desired effects as well as concepts of operations (CONOPS) objectives, the enemy system, target sets, and an attack scheme. To create a daily attack plan, each element was integrated with respect to a particular target effect. He emphasized the intense rate of change that was occurring nearly every hour, with new assets streaming into theater, new target requests, new intelligence, and new enemies. As the guidance and the target inputs continually changed, they needed to be integrated into the Master Attack Plan. The Master Attack Plan included force packaging the asset availability and capability as well as addressing issues of coherency and timing. All of this was expected to be informed by the processed (i.e., prioritized, with the level of effort remaining for a specific target to be identified, deconflicted from what is planned, and with an updated master target list) battle damage assessment (BDA) in order to generate new target inputs and an analysis of progress. However, he asserted that the scenario was changing so fast that the established processes were no longer responsive. Because neither processed BDA input nor feedback were provided within the first 48 hours, a new system had to be developed.

Lt. Gen. Deptula explained that several adjustments were made to the dynamic planning process (see Figure 1.1). Assigned officers (“planners”) reviewed film and conducted analysis internally, and a direct line was established to Checkmate and Rear Admiral Mike McConnell to access national information, conduct analysis, and collect feedback. Target inputs were revised, and weather became a crucial planning element. Next, a series of tracking mechanisms were built (e.g., target set boards, sequential Master Attack Plan, Mobile Servicing System 2+TV, Area Menu, Strategic Scorecard, 72-hour Priority Target List). He noted that F-117s dominated the air campaign plan against high-value targets owing to their precision and ability to penetrate; however, BDA/feedback continued to be delayed by several days, and targeting decisions could not be made based on previous attack outcomes.

An alternative way to derive feedback and optimize attack planning was needed, Lt. Gen. Deptula remarked. He set up a BDA officer in the planning unit who acquired F-117 release results at the end of every target cycle. Releases were assumed to be hits, and targets were only revisited if the BDA indicated a need. Failed releases

meant that the target would be re-planned. Thus, a time-sensitive targeting scheme was initiated. He reiterated that this experience is an example of how the change in capabilities in warfare accelerated the time cycle so drastically that it became impossible to rely on existing paradigms.

Lt. Gen. Deptula next discussed Operation Northern Watch (1998–1999), during which U.S. aircraft were increasingly threatened by Iraqi surface-to-air missile systems (SAMs). To protect the SAMs, Iraqi military commanders moved them close to structures such as mosques, which were off-limits to U.S. attacks. In response, Lt. Gen. Deptula directed F-15Es to use inert (cement) practice bombs with guided bomb unit-12 precision-guided munition kits against SAMs that were located near “off-limit” facilities, with the hope of achieving a kinetic kill from the precision guidance of a 500 lb projectile (instead of an explosive). He described this as an example of successful adaptation to an enemy counter; although it was not necessarily time-sensitive, it used an effects-based approach to conduct operations and eliminate the threat from SAMs.

Lt. Gen. Deptula explained that the urgency and the nature of the threat in Operation Enduring Freedom (2001) demanded new paradigms for command and control (C2), ISR, and information writ large. Despite the passage of a decade, problems remained with timely BDA/feedback. In addition to the lack of real-time ISR, an excessive vetting cycle negated the technological advantage (a problem that still exists today), and centralized control–centralized execution created problems. He detailed the following solutions that were implemented to

alleviate these challenges: (1) JTF commanders had tasking authority over ISR assets; (2) real-time connectivity and C2 between sensors and shooters emerged; (3) time-sensitive targeting timelines were measured in minutes, not limited by longer decision-cycle timelines (even today, it can take as long as 58 days to digest information before hitting a target); (4) the concern regarding collateral damage and the need to accomplish a mission was balanced; and (5) centralized control–decentralized execution did not devolve into centralized control–centralized execution (i.e., the Soviet model), which would have stifled initiative, induced delay, moved decision authority away from the expertise, and generated excessive caution. He advocated for leaders to be empowered, especially during the information age, to make decisions more quickly without waiting for permission.

Lt. Gen. Deptula described Operation Unified Assistance (OUA) (2005) for tsunami relief as an example of the mismatch between anachronistic command arrangements and rapid response. Pacific Command had predesignated the Third Marine Expeditionary Force as a JTF response headquarters for all humanitarian assistance and disaster relief events that required a U.S. military response, but it would take them 10 days to deploy to Thailand. As the Combined/Joint Force Air Component Commander, Lt. Gen. Deptula made a request to the JTF commander to move airlift as soon as possible instead. The standing Pacific Air Forces C2 Operations Center was the key to rapid stand-up of these OUA airlift relief operations. This positive action on the part of the USAF allowed for immediate response to the needs of an area, without concern for who was originally “tasked” with the response. The final example that Lt. Gen. Deptula provided related to the Taepodong-2 missile launch (2006, 2009). In this case, the time compression imposed by an intermediate range ballistic missile launched against an ally or U.S. base did not allow for the traditional centralized C2 associated with intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) response. The solution was to establish delegated and distributed C2 with predetermined response options so that the local commander was empowered to execute.

Lt. Gen. Deptula highlighted technological-driven trends for the future of major theater warfare. For example, he expected that platform-centric operations would transition to network-centric operations, high explosives would be replaced with photonic and electronic capabilities, individual precision weapons would be replaced with volumetric weapons, destruction-focused engagement would become effects-focused engagement, and dogfighting would be replaced with datafighting. He explained that new technologies introduce new capabilities, which demand adaptation and new types of responses. In closing, he shared several observations:

- The U.S. military generally does not learn its lessons; it reinvents the problem each time a similar challenge arises.

- Better professional military education may help.

- Once an operation starts, there is no time to study the lessons of the past.

- Future major conflict will most likely be more rapid than past conflict.

- New technologies, CONOPS, and organizations will drive new capabilities, but studying the lessons of the past will assist in optimizing their application for the future.

- Although difficult, it is crucial to change the status quo, especially in the USAF.

During the question-and-answer session, Gen. Martin asked for guidance on using artificial intelligence (AI) to aid decision makers. Lt. Gen. Deptula said that there is enormous application for and utility to adopting AI to inform decision makers. AI can absorb, analyze, and present a vast amount of information in a logical way and can be used to enable more timely, accurate, and effective decisions. He added that AI can increase information sharing among allies and partners, and AI can assist programmers, planners, pilots, and operators to optimize information for use.

Dr. Chellappa asked how to attract a workforce for future defense operations when talented individuals often pursue employment with high-paying social network companies. Lt. Gen. Deptula suggested contracting out for those positions. Dr. Michael Yarymovych, president, Sarasota Space Associates, inquired about the effects of disinformation. Lt. Gen. Deptula described this as an issue for the intelligence community to address. He cautioned the USAF against being paralyzed by the desire for fully valid information, especially in terms of the military’s excessive concern about collateral damage in warfare. In response to a question from Dr. Chellappa about fighting adversaries with strong air defense systems, Lt. Gen. Deptula said that in order to have rapid, decisive results,

the USAF has to buy the appropriate equipment and implement the appropriate architectures to allow information sharing in a secure, robust, and reliable way. Ms. Westphal asked how the USAF should confront social media and other forms of real-time information that could influence operations. Lt. Gen. Deptula advocated for change at the national level: Although the U.S. security apparatus has cabinet-level agencies for diplomacy, military, and economics, it does not have agencies dedicated to planning, administering, and using information (i.e., truth) as a weapon for security operations. He expressed concern that the United States has ceded the information battlefield to its adversaries, and he suggested that an information-operation center be established to monitor the communications and media emerging from other countries.

TIME AND THE AIR FORCE: THOUGHTS AND REFLECTIONS FROM THE PAST FIVE DECADES

Ms. Natalie Crawford, senior fellow and RAND Distinguished Chair in Air and Space Policy; and professor, Pardee RAND Graduate School, conveyed several experiences related to the curiosity, critical thinking, determination, and innovation involved to achieve new capabilities. She began her presentation by recounting the history of the Thanh Hóa Bridge in Vietnam. The United States continued to send airplanes—losing both human lives and the airplanes—despite not once being able to hit the bridge. This inspired weapons designers to adapt lasers as target designators and to make bomb guidance units and fin kits that could turn conventional unguided bombs into the first “smart” bombs. This began a revolution in weapons development, but the innovators who did this risked their careers as they struggled to overcome traditional bureaucratic hurdles. Ms. Crawford described this as an example of the importance of eliminating boundaries and providing opportunities for people with worthy ideas to present them.

Ms. Crawford’s next account related to Operation Desert Storm and the “great Scud hunt.” While in Checkmate, she suggested that officers of field-grade rank (typically at the Major level) contact their opposite numbers in Strategic Air Command, which had experience tracking mobile ballistic missiles and had developed a target-hunting strategy. Simply by connecting working-level Majors with Strategic Air Command, she helped short-cut what otherwise could have been a lengthy top-down-driven inquiry and response process, enabling rapid implementation of a counter-Scud search strategy. Ms. Crawford emphasized that many problems of the past resurface; it is important to recall lessons learned and apply them in new ways.

In the late 1980s, Ms. Crawford was part of a USAF Scientific Advisory Board panel that did a study on conventional weapons, one of the categories of which was hard target weapons. The panel cautioned the USAF against reinventing every piece of the weapon; instead, it suggested (1) canceling the hard structure weapon program, because it could not achieve the desired penetration; and (2) using the U.S. Navy’s model for armor-piercing weapons. However, the USAF only implemented the first recommendation. Ralph McGuire, a member of the armament group at Eglin Air Force Base, then developed a prototype of a weapon that was tested and produced; ultimately, it became the weapon that would be carried on the F-117. Ms. Crawford championed his courage and persistence as well as the open minds of those who listened to him. She added that in a time of budget crisis, technology can be leveraged at a reasonable cost to conduct and excel in missions (e.g., stealth precision-guided weapons emerged in an era of budgetary crisis). In 1981, Ms. Crawford continued, the USAF was thinking about the next fighter that it needed to build, and RAND was asked to provide recommendations. With consideration for air survivability and superiority, RAND recommended the development of two airplanes: a ground attack airplane for survivability with both sensors to find and attack the target and a small set of “mission systems,” and an air superiority aircraft that was high altitude and high speed. RAND suggested a suite of weapons characteristics and sensors for the air superiority aircraft: Range and speed of weapons are incredibly important, she explained, as is the ability to identify the enemy and achieve “first shot, first kill.”

Lastly, Ms. Crawford described the low-altitude missions of the Vietnam War, during which pilots would see targets too late and would have to risk their lives during re-engagement amidst antiaircraft guns. She presented an innovative solution to that problem, although it was not technologically feasible at that time: a helmet-mounted sight with a laser ranger on the airplane. Another time in which Ms. Crawford shared an innovative solution occurred when the USAF retired the F-111, owing to its high cost. As a result, the USAF was left with a void in the long range, high payload, and speed provided by the F-111, and she suggested building an F-15E as a replace-

ment. Ms. Crawford explained that she is an example of an “outsider” who observed and learned from those in uniform who risked their lives. She worked tirelessly to earn the trust and credibility that would prompt the USAF to pursue her observations and assessments.

During the question-and-answer session, Workshop One chair Dr. Richard Hallion, senior adviser, Science and Technology Policy Institute, commented on the role of the “gifted outsider” who can sidestep established research, development, test, evaluation, and acquisition processes. He wondered how the USAF could take better advantage of opportunities to work with those individuals and improve its efficiencies. Ms. Crawford replied that the key to success is building trusted relationships over time. Gen. Martin asked why many of the institutional mechanisms created to develop innovative ideas have been unsuccessful. Ms. Crawford said that development planning (and the inquisitive nature of development planners) was a successful approach to fill capability gaps. The development planning organization at Wright Patterson Air Force Base was strong both technically and operationally; however, no similar infrastructure exists today. She championed the USAF’s “Pitch Days” and suggested corralling talented individuals from Silicon Valley, whose techniques and capabilities can be applied to defense systems and programs. Gen. Martin advocated for a “push/pull” approach in which (1) trusted experts share valuable suggestions with people with authority and resources, and (2) the USAF consults experts for direction on preconceived ideas. He emphasized the important role of a dedicated leader in pursuing this approach. Dr. Yarymovych asked how to bring ideas from non-military/non-government areas of the civilian world to the USAF. Ms. Crawford noted that the right type of mechanism already exists in the space arena, with SpaceX serving as a catalyst. She commended Gen. John Raymond for his commitment to moving forward without the creation of unnecessary bureaucracy to complete missions, remaining open to new ideas, and hiring recent graduates with fresh energy.

OPEN DISCUSSION

Recalling Ms. Crawford’s discussion of the connection between innovation and interpersonal relationships, Ms. Westphal said that in the 1990s, when phone books were still printed, it was easy to identify the right people to contact. However, given today’s bureaucratic processes and the inaccessibility of organization charts online, people with novel ideas have nowhere to take them. She noted that an adversarial relationship has emerged over the past decade between the “outside” and the “inside,” which has eliminated trust and blocked innovative conversations. Lt. Gen. Bowlds added that the only way an “outsider” can communicate ideas is if he or she happens to have an e-mail address for someone on the “inside” who can make connections to the right people. Lt. Gen. Wendy Masiello (USAF, ret.), president, Wendy Mas Consulting, LLC, asked if there are tools to help traverse the “iron walls” to locate visionary people. Ms. Westphal emphasized that focusing too much on the structure of the organization eliminates good behaviors, and focusing too much on products detracts from the facilitation of discussion and understanding. Gen. Martin mentioned that organizations such as AFWERX have been created to address some of these impediments to sharing ideas. Dr. Chellappa asserted that if people continue to protect their information in siloes, AI will not be of any use.

Dr. Joseph “Jae” Engelbrecht, president and chief executive officer, Engelbrecht Associates, LLC, observed that Ms. Crawford was contacted when people encountered problems that needed to be solved; now, the focus has shifted to organizational structure and process, and problems remain unresolved. Lt. Gen. Masiello pointed out that Ms. Crawford worked for a federally funded research and development center (FFRDC). Unlike a manufacturer, an FFRDC is not conflicted; its employees have objective perspectives and can build trust. She wondered if the USAF has lost the agnostic view to advise on internal processes. Dr. Yarymovych elaborated on the original concept for the FFRDCs, which was to bring in outside talent for a limited time to fix a specific problem. Lt. Gen. Masiello noted that this is the model that the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency uses—fresh ideas from engineering technology experts who contribute on a temporary basis. However, she mentioned that instead of hiring civilians some FFRDCs are now hiring retired military, which changes the original intent of the FFRDC. Gen. Martin inquired about the ability of FFRDCs to offer new thinking, and Lt. Gen. Masiello suggested that a deeper conversation may be necessary to determine potential future roles for FFRDCs.

In response to a question from Gen. Martin about developmental planning, Ms. Westphal described the time during which the USAF emphasized technical planning among civilians, military, and contractors: The contractors

would bring the expertise to the civilian engineers, and then the requirements would help to prioritize the ideas before the creation of a budget request. All of this was done without a directive; People worked independently to make connections, build a community, and find solutions to problems. She emphasized that this approach focused on decision making for the present and the future. Lt. Gen. Bowlds added that, during that era, the product centers owned the laboratory, which meant that the acquisition community was closely connected. Ms. Westphal observed that trying to allocate money to formalize development planning created problems, causing the focus to shift from innovation to bureaucracy. Gen. Martin commented that, in 1995, the money was taken from developmental planning, owing to the notion that current technologies should be maintained instead of creating new technologies. Dr. Brendan Godfrey, visiting senior research scientist, University of Maryland, asserted that, despite budgetary constraints, it is time to consider how to win today’s fight while preparing for the future.

INSTILLING COMBAT TIME CONSCIOUSNESS INTO A RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT, TEST, AND EVALUATION-INTENSIVE AIR FORCE ENTERPRISE: AIR FORCE SPACE COMMAND AS A POST-DESERT STORM CASE STUDY

Gen. Charles A. Horner (USAF, ret.), former Commander of the 9th Air Force, Central Command Air Forces, U.S. Central Command Joint Force Air Component, and Air Force Space Command, discussed speed as a function of war, and time and speed as a function of systems development requirements. He pointed out that definitions of speed vary depending on the audience and the function—for example, it could take 3 days to order munitions, build them up, and deliver them to the flight line; it could take 3 seconds for a flight leader to retarget if supported by the right communications and navigation system. Accelerating speed can also be defined in terms of the need to reduce delay, and Gen. Horner expressed dismay at the sometimes year-long delays to launch in space. Speed may be defined in relation to physics, bullet velocity, tanks, aircraft, and communications, and it comes from the acquisition program, he continued. For example, to hasten the delivery of capability from requirements to operations, Secretary Rumsfeld waived prohibitive regulations during Operation Desert Storm. However, contractors and system acquisition staff preferred to keep those regulations in place. Gen. Horner also noted times in which the USAF has performed too much testing, thus delaying the delivery of capabilities from weeks to months or years. He described speed as a state of mind—awareness is becoming increasingly important as the speed of weapons is increasing, as is the ability to make timely decisions. Speed of movement onto and on the battlefield and speed of sustainment are critical, he continued, and speed is key to create an element of surprise.

Gen. Horner explained that distance impacts speed, but the duration of a conflict matters above all. He observed that speed has always been of great importance in warfare. In the Civil War, the fastest won the most. In the Vietnam War, slow speed equated to a loss of life. Too much interference in tactical decisions and an inability to define an adequate strategy led to an unnecessarily long war. Speed enables a country to deter an enemy and contain a conflict. In Operation Desert Storm, speed was needed to counter Scud missiles, and speed was vital to defense—when the coalition saw how quickly Americans arrived, confidence increased. He explained that the first attack in Operation Desert Storm, the purpose of which was to get control of the air, required quick arrival. Preparation—including practiced process, joint exercises, and good coordination with the Airborne Early Warning and Control System, Rivet Joint Intelligence Aircraft, and flight leaders—enabled this level of speed and led to success, as did the air tasking order. However, he commented that BDA was so slow in Operation Desert Storm because many of the intelligence systems were from the Cold War (which limited the ability to share information), and intelligence staff were trained to report instead of to analyze. He emphasized the value of measuring output, instead of only measuring input.

Air and sea lift are also vital to speed, he continued. The United States excels in air, but its sea lift capabilities would benefit from improvement. Prepositioning can increase speed; for example, prepositioning munitions eliminated the Iraqis’ early edge in Operation Desert Storm. In terms of battle preparation (including timely intelligence), the United States is gaining an edge with space, and electronic countermeasures will impact how the USAF does business in the future. Because it is difficult to prepare for electronic countermeasures, speed in reaction to the enemy’s efforts (e.g., Global Positioning System jamming) is crucial. He explained that systems need to have good sortie rates and be reliable. In order to increase the speed at which the enemy is attacked, the

mass also has to be increased. In Operation Desert Storm, this was achieved through basing and hot turns, he continued.

In terms of future conflict, Gen. Horner commented that China is building its naval capacity quickly. The best way to prepare to fight against China at sea is for the U.S. Navy to coordinate with its allies, such as the Philippines, Japan, and Australia. He noted that the stealth bomber and cyber are the most valuable programs to fight and win against China, and anticipation and accurate planning will be key. This entails the efforts of many different people, and relationships between people, who deal with communication, systems, and data. He asserted that people often choose not to share information in a coalition because they are afraid to lose power, but information is only powerful if it is shared. “Info-ops” will remain a challenge in the future, and he suggested that a clearinghouse be established to enable information sharing. The ability to sort through data quickly and use them for decision making is crucial. Depending upon how many people are involved in this part of the process, either a better decision could be made or a delay could ensue.

Gen. Horner underscored that because organizational layers impede progress, it is important to push responsibility and authority as far down the chain as possible. Speedy decision making is enabled by a decentralized and flat organization (i.e., a two-level decision process that empowers flight leads to make decisions in the air). It is important to have committed political leadership to handle future conflicts, he continued. The enemy never shares what it will do or how, so the USAF has to be prepared to make timely decisions in the absence of full knowledge. He noted that one of the best ways to find truth is through argument, yet subordinates are taught not to argue with leaders. An honest perspective is crucial to understand and exploit the opponents’ and allies’ strengths and weaknesses. Another area for improvement is understanding ourselves and the enemy. Egos can interfere and create problems; he emphasized the value of having the courage to respect, argue, trust, and agree with coalition partners.

Gen. Horner said that speed is critical to support the warfighter, and speed affects the environment and execution of warfighting. Because “rules of engagement” impede decision making (as was the case in the Vietnam War), he advocated for people to be trusted to know the laws of armed conflict and to use common sense. While unique doctrines can be useful for the individual services, he continued, they can impair joint operations. When operating as a coalition, it is better to use common sense than a doctrine. He also encouraged the tolerance of mistakes, so as to preserve the integrity of the military, and for the humility to admit errors, which is the only way to improve.

During the question-and-answer session, Dr. Julie Ryan, chief executive officer, Wyndrose Technical Group, asked Gen. Horner about the importance of doctrine to set the basis for how to operate, with the ability to move beyond it to non-doctrinal operations. Gen. Horner replied that doctrine means different things to different people. Standardization of doctrine is crucial for decentralization, he continued, as is the ability to revise doctrine when it is not working. Ms. Westphal wondered how the USAF could transition from measuring inputs to measuring outputs and fight more effectively in a multi-domain C2 situation. Gen. Horner stated that people need to be trained to think about what they do, why, and what it means. This approach has to start at the top and flow down, with an emphasis on the mindset of winning a war over earning a promotion.

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN TIME CYCLE REDUCTION ACROSS THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY AND OPERATIONAL ENTERPRISE

Dr. Mark J. Lewis, Acting Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (USD(R&E)) and director of Defense Research and Engineering for Modernization, explained that his organization was created in 2018, when Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics was divided into Acquisition and Sustainment and R&E, and it oversees the laboratories, FFRDCs, university-affiliated research centers, the test resource management center, the prototyping efforts across departments, and several international activities. He described USD(R&E) as the technology lead in the Department of Defense (DoD), with the responsibility to coordinate across services and a “mandate” to do things as quickly as possible. USD(R&E) focuses on advancing the 2018 National Defense Strategy’s modernization priorities within the 2028 timeframe. Each principal director for the 10 technology priority areas has been tasked with the development of a modernization roadmap for the services and the agencies for 2018–2028, progress against which is continually evaluated. All are focused on doing things faster—for example, the Space Development Agency, which was created primarily to increase speed in space, has been challenged to

quickly develop a proliferated low-earth orbit infrastructure for communications. The mission would leverage both commercial industry and the state of the art for DoD applications.

Based on a recent evaluation of the services’ progress on the roadmaps, 20 percent of total expenditures across the Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation portfolio are being spent on modernization priorities, according to Dr. Lewis. There is particularly fast movement and coordinated efforts in hypersonics—on track to deliver capabilities in the hundreds of weapons by the late 2020s across all of the services. The area with the least coordination among the services is directed energy. While there is much investment in the 6.1, 6.2, and 6.3 areas, investment is lacking in 6.4, 6.5, and 6.6, which is key to deliver rapid capability. He described a greater reliance on more flexible funding mechanisms (e.g., Other Transaction Authorities) and on decreased acquisition time; however, the Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation continues to optimize on dollars instead of on technology, which is problematic. If one optimizes on the cost of the system, he explained, the legacy system will almost always appear to be less expensive than the new capability. However, this inexpensive legacy system may not have the greatest effect, which is most important to win a war.

During the question-and-answer session, Ms. Westphal asked about strategies to improve the adoption of technology from an operational perspective. Dr. Lewis highlighted two issues to consider: (1) failing to adopt and (2) adopting too quickly. For example, it does not make sense to move directly from 6.3 to operations. He championed prototyping as an important step between the laboratory and the delivery of a capability because prototyping allows for experimentation and the convergence of engineering teams that will transition to the programs of record. He said that although the USAF invests in its workforce and in building a talent pool, it often takes too long to make decisions, resulting in the need for the talent pool to be recreated (e.g., a hypersonic system developed in 2010 by the Air Force Research Laboratory and moved to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency several years later still has not been flown). He expressed disappointment that no institutional solution currently exists to address this problem.

Dr. Daniel Hastings, department head, Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, and professor of aeronautics and astronautics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, asked how the Space Development Agency increased the speed of acquisition. Dr. Lewis responded that the Space Development Agency is new, relies on a “can-do” attitude, and has a lean organization. He emphasized the value of selecting the right people to lead these endeavors. Dr. Yarymovych asked if DoD could operate more like the commercial enterprise. Dr. Lewis replied that DoD is two generations behind in microelectronics because it chose to build its own system instead of buying the state of the art. However, DoD plans to move away from that model, relying more on the commercial sector than on its own unique capabilities and developing an infrastructure and methodologies to confirm that the purchased technologies meet specifications, he continued. DoD is identifying locations where commercial technology can be tested and helping industry to develop standards. DoD is also working to pinpoint and mitigate any weak links in its supply chain.

Gen. Martin wondered what information the workshop planning committee could relay to Lt. Gen. S. Clinton Hinote about technology pushes and their inherent use in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force. Dr. Lewis suggested that directed energy only be used for problems that kinetic energy cannot solve. He added that the U.S. Navy currently leads in directed energy innovations. Significant barriers to acceleration and modernization occur when organizations such as Air Combat Command are asked to accept new solutions. They say, “That is great, but we have all of these legacy systems that we need to keep funding. How do we invest in this new, unproven thing?” Dr. Lewis emphasized that without modernizing, DoD will be unable to compete—speed of effect continues to be critical. He commented that the most expensive weapon is the one that leads to failure and urged that time be an important factor in analysis. Hon. Peters observed that when a new technology surfaces, there is often nothing in place to move it forward. Dr. Lewis agreed that it is important to think about how a weapon is employed as well as how it fits into other systems and the logistics chain.

In response to a question from Ms. Westphal, Dr. Lewis noted that the level of collaboration between technologists and the operators has improved since the 1990s. He added that the Air Force Warfighting Integration Capability (AFWIC) is a step in the right direction; a detailee from AFWIC will work 2 days each week in USD(R&E) to ensure that the organizations’ efforts are synchronized. USD(R&E) also has a strong relationship with the U.S. Strategic Command (on modernization priorities) and with the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. Dr. Chellappa mentioned that the National Science Foundation is aggressive in its development of AI institutes; he

suggested that more AI-based multidisciplinary university research initiatives (MURIs) that are directly relevant to DoD be established. Dr. Lewis responded that all of the services will align in some fashion with the modernization priorities (which would include AI) for the current round of MURIs.

TIME CYCLE REDUCTION AND TIMELY OPERATIONAL EXECUTION: INSIGHTS AND LESSONS FROM THE SPACE RACE

Dr. William Barry, former National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) historian, described two common perspectives of early space exploration: (1) The Soviets were in the lead, but (2) the United States eventually showed its dominance by beating the Soviets to landing on the moon. The standard line of propaganda (through the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s) was that the Soviets were not really racing to the moon; the United States was racing itself. In reality, a close race to the moon was under way. He explained that the space race provides data about the pace of a mission, how it can be pushed, and the limits of what can be done.

One of the lessons that the United States learned from the attack on Pearl Harbor during World War II related to the ability to prevent a surprise attack, especially in the age of nuclear weapons. However, Dr. Barry continued, the Soviets continued to accomplish technical surprises during the Cold War (e.g., the atomic bomb, H-bomb, and jet bomb). Their successes with nuclear weapons and aircraft could be attributed to active espionage activities to gather Western military secrets and to reverse engineer them in the Soviet Union. Given that the Soviet Union was devastated by World War II, the launch of Sputnik in 1957 could have been a surprise that was difficult to explain; however, the Eisenhower Administration was paying attention. Three years earlier, both the United States and the Soviet Union announced their intentions to launch a scientific satellite as part of the International Geophysical Year Program. To some, the launch of Sputnik was a relief because it settled the question of the legality of satellites overflying foreign territory, which was necessary to allow for U.S. reconnaissance. Dr. Barry explained that people began to wonder just how far ahead the Soviets were in the “race,” however, because the Soviet launch came first and was followed 1 month later by the launch of a dog into space. The Soviets did lead in one important area: the useful payload of the R-7 missile/launch vehicle. This, along with engineering talent—led by Sergei Korolev—and political leadership attention, led to a series of Soviet space firsts.

Dr. Barry noted that Nikita Khrushchev assumed the United States would be disturbed by the Soviets’ ability to strike the United States with an ICBM. However, nearly no one in the West was aware of the R-7 ICBM test, in part because the R-7 was not a powerful missile: It would only be able to reach the United States from the edges of the Soviet Union, and no bases had been built for that purpose. The R-7 also required day-long fueling and preparation time, which made it vulnerable to interception by Western aircraft before launch. However, the R-7 was a reliable space launch vehicle, derivatives of which are still in use today. Dr. Barry explained that the R-7 is the only launch vehicle that the Soviets and Russians have ever used to put humans in space.

Korolev and his team essentially hijacked the Soviet missile program to build a space program, Dr. Barry remarked. Khrushchev was not interested in Korolev’s space ambitions, but he faced the strategic problem of being surrounded by nuclear weapons from the Western powers without having enough resources to build the needed military or to deliver on promises of making the Soviet Union a “worker’s paradise.” When the world took notice of Sputnik, Krushchev asked for more, and Korolev delivered Sputnik II and Laika—the “space race” had begun. Krushchev used the engineers’ capabilities to distract and embarrass the United States repeatedly. Dr. Barry commented that Krushchev’s focus on public “one-upmanship” gave the impression that the Soviets were the “pioneers of the universe.” However, in the early days of the space race, the Soviets did not even have a space program; they had several individual space projects that were pursued to give the impression that the Soviet Union had a technological advantage over the West. Despite this reputation, Dr. Barry continued, looking at the actual number of successful space launches between 1957 and 1969 reveals that the United States was far ahead of the Soviet Union. The U.S. program was much broader—developing space science programs, reconnaissance satellites, communication satellites, navigation satellite systems, and weather satellites—whereas the Soviet “space program” was largely devoted to one-off public relations missions to suggest that the Soviets were out-innovating the United States. Furthermore, the Soviets never exceeded the number of different kinds of launch vehicles that the United States had during this time.

Dr. Barry asserted that the Soviets were able to “win” the space race because they had a small, nimble, highly dedicated team that carefully followed what the United States was doing, which included a massive collection and translation effort, and pinpointed mission ideas that they could achieve with the space launch vehicle that they already had. This allowed them to provide propaganda points quickly to the Soviet leadership. Although Korolev and his space projects had top priority access to the resources of the Soviet state, the close association of the Soviet leadership with the space program became a liability when the United States won the race to the moon. Dr. Barry explained that failure to stay in the lead in the space race undermined public trust in the Soviet government’s ability to deliver on its promises and contributed to the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s.

Dr. Barry concluded his presentation by describing three key lessons learned:

- Even with the full power of the state, innovation efforts based on appearances are not sustainable, and innovation efforts that depend on top-level leadership direction will work only within the limits of the attention of the leadership.

- The United States winning the race to the moon in the long-run demonstrates that innovation thrives best in an environment with a robust organizational ecosystem. The depth and breadth of the U.S. aerospace industry was critical to winning the race to the moon.

- Knowledge about how an innovation opponent is organized (i.e., how decisions are made, what the capabilities are) is critical to understand what that opponent is doing or what game it is playing. The United States did not have that with the Soviets during the space race, as it was (and sometimes still is) unclear that the Soviets were bluffing about their capabilities to buy time to build up defenses. This is an important lesson as the United States considers interactions with China in space, which would be enhanced by the use of analysts with cultural and linguistic expertise as well as reliable data.

During the question-and-answer session, Dr. Chellappa asked about lessons that could be applied to interactions with future rivals such as Iran. Dr. Barry replied that it is most important to understand the opponent, what game it is playing, whether it is trying to out-innovate, and whether it is trying to accomplish some other objective, as was the case with the Soviets. The space race played out politically because the United States did not know what was occurring in the Soviet Union, how they made decisions, and that their “space program” was actually a public relations campaign.

Ms. Westphal inquired about the information gap, and Dr. Barry responded that the United States did not have reliable human intelligence during that era; when it progressed in the mid-1960s, the United States began to better understand the Soviets’ actions. Dr. Barry reiterated the importance of having personnel dedicated to uncovering information as well as technical staff who understand that information. Ms. Westphal wondered if that kind of collaboration exists now between NASA and the military, as the United States is engaged in an information and space war with Russia. Dr. Barry said that it is possible, although he was not aware of such an arrangement.