1

Introduction

Large-scale disasters continue to strike the United States with escalating frequency, greater magnitude, and substantial costs to the health, social, and economic welfare of affected communities (Boustan et al., 2020). From Hurricane Katrina in 2005 to the Paradise wildfires of 2018, recent disasters have exposed gaps in the capacity of the nation’s critical child infrastructure (i.e., the existing systems and networks of social and human services that serve children and youth) to fully support children and youth throughout the disaster response and recovery process. Experiencing a disaster can affect the physical and emotional health of children and youth in myriad ways that extend beyond the immediate danger of physical hazards. They may face months or even years of challenging circumstances, such as displacement from their communities, interruption of their education, and disruption of regular health and social support services. Others experience the trauma of lengthy separation from their families or—particularly in the case of children and youth who are already vulnerable because of other factors—the potential for exploitation. Those who live in disaster-prone areas, such as the Gulf Coast, may experience multiple large-scale disasters before they are adults, but the effects of cumulative disaster exposure and prolonged displacement are only beginning to be understood. On the other hand, children and youth can contribute in valuable ways to bolster their families and communities throughout the recovery process. Despite their unique needs, vulnerabilities, and capabilities, children and youth have traditionally been overlooked or under-considered in disaster planning and preparedness efforts.

WORKSHOP OBJECTIVES

To explore issues related to the effects of disasters on children and youth and lessons learned from experiences during previous disasters, the virtual workshop From Hurricane Katrina to Paradise Wildfires, Exploring Themes in Disaster Human Services was convened on July 22 and 23, 2020, by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (see Appendix A for the workshop’s complete Statement of Task).1 This workshop is the first in a series of workshops exploring promising practices, ongoing challenges, and potential opportunities that have arisen since Hurricane Katrina in the coordinated delivery of social and human services programs following federally declared major natural disasters. The workshop was sponsored by the Office of Human Services Emergency Preparedness and Response (OHSEPR) at the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The objectives of the workshop were the following:

- Understand the critical child infrastructure (i.e., the existing systems and networks of social and human services that serve children and youth) and how it functions (i.e., how services are delivered) before, during, and after a major federally declared natural or environmental disaster.

- Understand the negative effects of disasters on children and youth that can be mitigated by the provision of social and human services.

- Understand the current gaps and future opportunities for supporting coordinated delivery during, and restoration of services following, a major federally declared natural disaster.

- Explore potential matrices for evaluating response and recovery efforts related to social and human services.

Roberta Lavin, member of the workshop planning committee and professor at the University of New Mexico College of Nursing, detailed the intended scope of the workshop and highlighted that the past disasters discussed would span from Hurricane Katrina in 2005 to the Paradise wildfires of 2018. Lavin explained that the effects of, and the response to, the COVID-19 pandemic would not be a main point of focus during the workshop. The populations of interest were children and youth aged 0–26 years,

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop Series was prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants, and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

and the workshop was designed to focus on individuals who receive public support prior to disasters (i.e., people with socioeconomic deficits prior to the disaster). Additional areas of focus were the coordination of disaster response efforts and the transition to reestablishing routine service delivery programs postdisaster by human services, social services, and public health agencies at the state, local, tribal, and territorial levels. The workshop was also intended to provide a platform for highlighting promising practices, ongoing challenges, and potential opportunities for coordinated delivery and restoration of social and human services programs.

WORKSHOP BACKGROUND: SETTING THE STAGE

Scott Lekan, principal deputy assistant secretary at ACF, described the rationale for the workshop and reviewed ACF’s goals during and after disasters. In his capacity as principal deputy assistant, he supports the management and daily operations of 64 programs and 16 program offices within ACF designed to support individuals, families, and communities in crisis. ACF is the largest grant maker within HHS, providing approximately $8 billion annually through direct funding to households and other grantees. These funds are intended to provide communities with the necessary services to support their economic resilience and develop individuals by centering their life experience in human service delivery models. ACF’s programs support a wide range of human and social services, including early childhood education, support for abused and neglected children, support for trafficked persons and survivors of domestic violence, temporary financial assistance, and job training and education. He noted that the workshop’s participants included an array of thought leaders in emergency management and disaster operations who have special expertise in issues affecting children and youth in postdisaster contexts.

Lekan emphasized that children are not merely small adults; they require tailored support because disasters or other traumas can affect children’s development. After a disaster, affected communities—particularly vulnerable groups and children—need appropriately targeted support. To identify a path forward in the face of increasingly complex and layered disasters, ACF is focused on childhood adoption, primary prevention, and promoting person-centered, whole family–integrated, streamlined services by moving from a compliance delivery model to one focused on measuring outcomes. ACF works across federal agencies such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Department of Education, and other HHS agencies such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the Administration for Community Living (ACL). He added that while ACF’s overarching aim is primary prevention, it also focuses on supporting communities through child care systems that

enable people to work while safely supporting their children’s development. Lekan explained that helping individuals return to work after disasters is necessary for communities to begin recovering economically. He encouraged workshop participants to incorporate the messages that emerge from the workshop into their ongoing disaster readiness efforts as well, as ACF plans to do.

DISASTER HUMAN SERVICES: CONNECTING THE HUMAN SERVICE NETWORKS

Natalie Grant, director of OHSEPR at ACF, described the genesis of federal disaster human services and how they are situated within the broader human services networks today. ACF promotes the economic and social well-being of families, children, individuals, and communities. Each ACF office has a director or a commissioner who ensures that the activities of the office support ACF’s mission. She likened social and human services delivery to a patchwork quilt, suggesting that the various social and human services that affect the lives of individuals must be pieced together, especially when responding to disasters. The recognition that these services must be connected led to the creation of OHSEPR in 2006.

Grant explained that in 2006, a report by the Executive Office of the President on the federal response to Hurricane Katrina found that a major challenge in the delivery of human services was the disconnected network of independent actors, programs, and services that were not adequately coordinated to meet the needs of the disaster survivors (DHS, 2006) (see Box 1-1). In 2006, the White House responded by issuing a directive that HHS coordinate with other departments of the executive branch, state governments, and nongovernmental organizations to develop a robust, comprehensive, and integrated system to deliver services during disasters. In addition to ACF being tasked by HHS to coordinate with other HHS operating divisions to develop this capacity, another outcome of the directive was the creation of OHSEPR to provide policy development, coordination, guidance, and support to the ACF assistant secretary and ACF regional offices. The focus of OHSEPR is to coordinate ACF programs in partnership with other social and human service providers (e.g., SAMHSA, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and ACL). She noted that all of those entities have programs and touch points with the lived experience and that those social and human services were designed to help facilitate this type of coordination after a disaster.

Grant described how ACF’s programs fit into the broader disaster response network through their focus on:

- Integrated and holistic service delivery through community hubs,

- Family-focused case management empowered by digital platforms,

- Flexible policies and programs that foster innovation such as disaster waivers and flexibilities,2 and

- A crisis management approach to changing human service delivery.

Grant added that OHSEPR has also established three national priorities to build a coordinated national disaster human services capability. The first priority is to develop “disaster human services” as an ACF-led HHS enterprise. The second is to develop effective partnerships to execute the department’s mission for health and human services as part of the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) Emergency Support Function (ESF) 6.3 The third is to maintain focus by developing outcome-oriented solutions, reducing the burden to jurisdictions through collaboration, and demonstrating the value proposition to engaged parties.

___________________

2 More information about ACF disaster waivers and flexibilities is available at https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ohsepr/training-technical-assistance/acf-emergency-and-disaster-waivers-and-flexibilities (accessed May 20, 2021).

3 More information about FEMA’s ESF 6 is available at https://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nrf/nrf-esf-06.pdf (accessed March 2, 2021).

Grant provided an overview of ACF–OHSEPR roles in leadership, coordination, and partnership, noting that ACF activities are nested within the ecosystem of HHS programs, federal interagency activities, and the activities of national and nongovernmental partners. OHSEPR coordinates disaster human services by leading disaster human service delivery and coordination, developing ESF 6 and ESF 8,4 and partnering with HHS operation divisions and staff divisions on operational planning aspects of ESF 6. Grant noted that the office learned from previous disaster experiences and is

- developing jurisdictional emergency management human service capability;

- connecting health care, public health, and human services to create partnerships;

- partnering with HHS operation divisions and other federal emergency management components on predisaster readiness; and

- developing the disaster human services science agenda.

Regarding the latter, she explained that the goal is to initiate the development of a body of evidence-based knowledge for disaster human services. The focus is on identifying substantive observations, significant changes, and ongoing deficits in disaster human services provision and coordination that have occurred since Hurricane Katrina. The desired outcome is the development of a roadmap for providing timely, coordinated, and appropriately targeted human services after disasters. She noted that the workshop on children and youth in disasters was convened to help move the field of disaster science forward, with future workshops planned to explore population displacement in disasters as well as data sharing and information management in disaster human services.

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE NATIONAL COMMISSION ON CHILDREN AND DISASTERS

To further help contextualize the workshop’s objectives, Lavin highlighted several recommendations made by the National Commission on Children and Disasters in its 2010 report to the president and Congress (NCCD and AHRQ, 2010). She assessed the current status and progress toward achieving those recommendations and highlighted areas where further work is needed.

Recommendation 2.3 called for federal agencies and nonfederal partners to enhance predisaster preparedness and just-in-time training in pediatric

___________________

4 More information about FEMA’s ESF 8 is available at https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/fema_ESF_8_Public-Health-Medical.pdf (accessed March 2, 2021).

disaster mental and behavioral health—including psychological first aid, bereavement support, and brief supportive interventions—for mental health professionals and individuals, such as teachers, who work with children. Lavin said that psychological first aid has been successfully implemented and is now being taught nationwide, with organizations like the Children’s Bereavement Center of South Texas working with organizations such as FEMA and the American Red Cross to provide support after disasters.

Recommendation 5.2 called for disaster case management programs to be appropriately resourced and to provide consistent holistic services that achieve tangible, positive outcomes for children and families affected by the disaster. ACF has operated a disaster case management program for more than 10 years, Lavin noted. Recommendation 6.1 called for Congress and federal agencies to improve disaster preparedness capabilities for child care. After Hurricane Sandy, it became a requirement that child care providers have disaster plans. Recommendation 6.2 called for Congress and federal agencies to improve capacity to provide child care services in the immediate aftermath of and recovery from disasters, including codifying child care as an essential service of a governmental nature. Lavin noted that some states have since designated child care as an essential service, including New York. Recommendation 6.3 called for HHS to require disaster preparedness capabilities for Head Start centers and basic disaster mental health training for staff. In 2009, Head Start published the Head Start Emergency Preparedness Manual, which has since been updated and includes many resources.5 Furthermore, FEMA has since published an emergency preparedness guide for Head Start.6

Lavin said that despite this progress, there is room for improvement. For instance, Recommendation 7.1 calls for ensuring that school systems recovering from disasters are provided with immediate resources to reopen and restore the learning environment in a timely manner and provide support for displaced students and their host schools, including funding. Additionally, Recommendation 8.2 calls for ensuring that state and local juvenile justice agencies and all residential treatment, correctional, and detention facilities that house children can adequately prepare for disasters. She pointed out that the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency does not list child care, schools, and human services as critical infrastructure sectors; she proposed that these three sectors be classified as critical infrastructure sectors.7

___________________

5 More information about the FEMA Preparedness Portal is available at https://community.fema.gov/AP_Login?startURL=%2Fstory%2Femergency-preparedness-for-head-start%3Flang%3Den_us (accessed October 26, 2020).

6 More information about the Head Start Emergency Preparedness Manual is available at https://rems.ed.gov/docs/Head_Start_Emergency_Preparedness_Manual.pdf (accessed October 26, 2020).

7 More information about critical infrastructure sectors is available at https://www.cisa.gov/critical-infrastructure-sectors (accessed October 26, 2020).

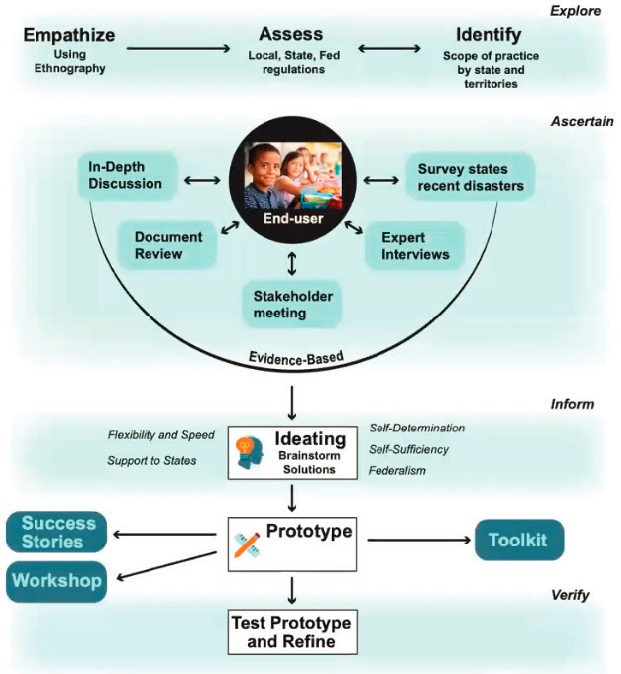

To establish a path forward, Lavin suggested applying a human-centered structured analytic approach (see Figure 1-1). This approach puts children as the end users and requires exploration through empathizing using ethnography; assessing local, state, and federal regulations; and identifying the scope of practice by states and territories. However, Lavin explained that the scope of human services will need to be better specified in order to identify the evidence base needed to optimize this approach; stakeholder meetings, such as the present workshop, can contribute to developing that evidence base and establishing actionable items. She added that new approaches should address the issues of flexibility, speed, and support to states, as well as self-determination, self-sufficiency, and federalism.

ORGANIZATION OF THE PROCEEDINGS

This Proceedings of a Workshop Series is organized into six chapters. The second half of Chapter 1 focuses on providing an overview of critical child infrastructure and the framework of disaster response services for children. Chapter 2 summarizes the workshop’s keynote address, which explores the effects of environmental extremes on children and disasters. Chapter 3 focuses on the effects of disasters on critical child infrastructure. Chapter 4 explores the gaps in evidence relating to children in disasters. Chapter 5 presents case studies from four breakout panels held during the workshop, which focused on the effect on children with issues brought on by, or exacerbated by, disasters; the effect of disasters on parents and guardians; the effect of disasters on children with complex or special needs; and the effect of disasters on unaccompanied minors. Chapter 6 presents the reflections of workshop participants and speakers and explores ways to pursue the outcomes and objectives set forth by the workshop.

CRITICAL CHILD INFRASTRUCTURE

The first panel of the workshop provided an overview of critical child infrastructure and the framework of disaster response services for children. The session’s aims were (1) to review existing systems and networks of social and human services that help children, review how these services are delivered in normal times, and review how these services prepare for major federally declared disasters; and (2) to identify flaws and gaps in the normal delivery of services that become more harmful when disasters strike. The session was moderated by Tarah Somers, regional director, Region 1 of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

SOURCE: Lavin presentation, July 23, 2020.

Administration for Children and Families and Steady-State Preparation for Natural Disasters8

Deborah Bergeron, director of the Office of Head Start (OHS) and director of the Office of Early Childhood Development at ACF, discussed

___________________

8 This section is based on the presentation of Deborah Bergeron, director of OHS and director of the Office of Early Childhood Development at ACF.

steady-state9 preparation for natural disasters. She outlined the efforts of ACF offices to provide emergency assistance, domestic violence prevention, homeless youth services, disaster preparation for Native American and tribal communities, human trafficking prevention, refugee resettlement, and child welfare services. She noted that one of the Office of Early Childhood Development’s goals is to bring early childhood issues to the table throughout ACF and find common areas where offices can collaborate to be more efficient and effective in serving children during disasters.

Office of Community Services/Office of Family Assistance

The Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) is run by the Office of Community Services (OCS)/Office of Family Assistance. The program provides funding to states, territories, and tribes to assist with home energy bills for low-income households. Bergeron noted that while the program’s focus is on heating and cooling—through bill payment assistance and weatherization services—LIHEAP funding can also be used to respond to disasters. This can include temporary housing, transportation to shelters, generators, energy-related home repairs, and other specified emergency needs. LIHEAP assistance is available for both temporary disasters and long-term events.

Family Youth Services Bureau

The Family Youth Service Bureau addresses needs related to family violence and homeless youth during a disaster. The Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA) provides funding for emergency shelter and other supportive services to domestic violence victims and their children. Bergeron noted that domestic violence tends to increase during disasters owing to heightened stress caused by these events, thus disaster preparedness and domestic violence prevention are related. To ensure collaboration, an FVPSA liaison works with the OHSEPR team in this effort. The Family Youth Services Bureau also addresses the needs of children via its Runaway and Homeless Youth unit. This program has an emergency preparedness plan that includes strategies for addressing evacuation, food insecurity, medical supplies, and notification of youths’ families, when appropriate. A challenge that this unit faces is that children who are not linked with a home can be difficult to locate, she added.

___________________

9 “Steady-state” refers to normal operations, when no incident or specific risk or hazard has been identified.

Administration for Native Americans

The Administration for Native Americans (ANA) focuses on disaster preparation for Native American and tribal communities. Training is the focus of ANA’s national disaster preparation, said Bergeron. ANA provides resources on natural disaster preparation on its website—which also provides disaster preparedness resources—and through webinar trainings and in-person training opportunities. In February 2020, ACF hosted a large Native American grantee meeting that included training from OHSEPR on disaster preparedness, such as planning in advance for service provision and developing continuity-of-operations plans. Bergeron noted that the meeting was held before the COVID-19 pandemic was recognized in the United States and was reflective of ANA’s steady state of affairs.

Office on Trafficking in Persons

Working closely with OHSEPR and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), the Office on Trafficking in Persons (OTIP) identified flexibilities and waivers for grantees and developed an infographic titled “Preventing Human Trafficking: What Disaster Responders Need to Do.”10 OTIP raises awareness that disasters increase the risk of human trafficking and provides guidance on disaster-related readiness, response, and recovery steps, said Bergeron. The office also conducted a literature review on human trafficking and natural disasters to inform public awareness efforts as well as program and policy development. The flexibilities identified by OTIP include administrative relief in the form of postponing deadlines for submission of program performance and financial reports, as well as the option to extend client enrollment in federal antitrafficking programs administered by OTIP during a natural disaster. Bergeron highlighted the importance of flexibilities in responding to disasters, noting that the state of emergency in the United States related to the COVID-19 pandemic further underscores the extent to which flexibility is important.

Office of Refugee Resettlement

Policy flexibilities during natural disasters are also a focus of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), said Bergeron. For example, in 2017, ORR issued policy letter 17-03, which provided funding and waiver opportuni-

___________________

10 More information about preventing human trafficking is available at https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/abc/Documents/disaster-resp-trafficking.pdf (accessed October 27, 2020).

ties after Hurricanes Harvey and Irma.11 She noted that these types of policy flexibilities are typically designed for events such as hurricanes and blizzards; thus, during a global pandemic, determinations have to be made as to whether these flexibilities apply. To support unaccompanied youth, ORR’s Unaccompanied Alien Children program partnered with ASPR, OHSEPR, and ACF’s Division of Planning and Logistics to monitor threats, report effects to care providers, and provide necessary follow-up actions. The Division of Planning and Logistics also provides training to Unaccompanied Alien Children program divisions on emergency preparedness and response throughout the year to ensure that staff are trained and prepared for potential natural disasters. She added that both OHS and ORR are concerned with the needs of children in the care of other organizations and how these children will respond to a disaster or emergency.

Children’s Bureau

The Children’s Bureau section of the Social Security Act, section 422(b)(16),12 requires state child welfare agencies to have disaster preparedness plans in place. These state plans must describe how a state would do the following:

- Identify, locate, and continue the availability of services for children under state care who are affected by a disaster.

- Respond appropriately to new child welfare cases in disaster areas.

- Remain in communication with child welfare personnel displaced by a disaster.

- Preserve essential program records.

- Coordinate services and share information with other states.

Bergeron remarked that both coordination of services and communication are critical when disasters displace people and cut them off from normal lines of communication.

Office of Head Start

To prepare for natural disasters, OHS coordinates with other child welfare offices on the ground and has developed its own emergency pre-

___________________

11 More information about ORR’s policies on populations displaced or affected by Hurricanes Harvey or Irma is available at https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/resource/orr-populations-displaced-or-affected-by-hurricanes-harvey-and-irma (accessed October 27, 2020).

12 More information about the Social Security Act, section 422(b)(16), is available at https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title04/0422.htm (accessed October 27, 2020).

paredness manual.13 Bergeron stated that OHS also provides strong support to its grantees and programs to create their own setting-specific plans tailored to the types of natural disasters more common in a given area; such plans include establishing family engagement systems and embedding mental health systems. She explained that OHS directs federal funding to local grantees running Head Start programs and is responsible for oversight of those programs. Flexible language is also in place to enable OHS to mobilize when disasters occur. For example, the response by OHS to the COVID-19 pandemic used policy language developed during Hurricane Maria. She noted that the most vulnerable children and families are affected when disasters displace entire communities. Disaster situations give rise to immediate needs (e.g., food) as well as to long-term needs such as mental health supports. Furthermore, once a program is rebuilt and reopens, the children return having experienced trauma. In Puerto Rico, for instance, when programs reopened after Hurricane Maria, teachers noticed that some children would panic when the weather shifted because of associations with the hurricane. Therefore, they try to “front load” support for such situations rather than being reactionary, she added.

Systems and Services to Support Children and Families During Disasters14

Josephine Bias-Robinson, board member at Life Pieces to Masterpieces, provided an overview of the disaster response programs in OCS and how they interrelate. She discussed federal, state, and local organizations with which OCS partners in disaster response, recovery, and revitalization efforts, as well as outlining OCS’s role in providing guidance and clarification on eligibility status and funding flexibilities during crisis assistance and recovery.

Office of Community Services

The mission of OCS is to increase the capacity of individuals and families to become more self-sufficient and to help build, revitalize, and strengthen their communities. Bias-Robinson noted that discussions of children and youth cannot be separated from discussions of families. Thus, OCS provides opportunities to directly affect hundreds of thousands of people through the office’s programs as well as connecting the federal level to local communities.

___________________

13 The OHS Emergency Preparedness Manual is available at https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/emergency-preparedness-manual-early-childhood-programs.pdf (accessed October 28, 2020).

14 This section is based on the presentation of Josephine Bias-Robinson, board member at Life Pieces to Masterpieces.

Bias-Robinson explained that block grants are OCS’s primary programs; they push funds, resources, and information into communities. For instance, the social services block grant (SSBG), community services block grant (CSBG), and LIHEAP provide funding directly to states. These programs also provide opportunities for states to coordinate on a localized level with community partners. By providing the bulk of human services federal funding that flows into states, these block grants direct funds to community action agencies via state social services, human resources, and labor departments. The block grants also provide flexibility in terms of the types of community services they fund. She noted that these block grants are the vehicles for supplemental funding to be distributed to states when disaster strikes. The nature of these programs and the legislative authorities they have within states lend themselves to use in times of disaster, she added. For example, in the response to Hurricane Katrina, the SSBG was one of the first vehicles that Congress used to authorize supplemental funding to states, including Texas and some of the outlying states that received evacuees.

Bias-Robinson outlined additional OCS programs that are secondary in disaster response, providing mechanisms to deliver disaster response services if funding is available and can be repurposed or amplified. These include Assets for Independence, Urban and Rural and Community Economic Development, and additional programs that were available after Hurricane Katrina but are no longer funded as part of OCS (e.g., the Community Food and Nutrition program, the Compassion Capital Fund, the Job Opportunities for Low-Income Individuals program, and the Rural Facilities Program). Although these latter programs were no longer funded at the time of the workshop, Bias-Robinson said that they were valuable in supporting affected communities during times of disaster.

Partnerships to Support Response, Recovery, and Revitalization

Bias-Robinson emphasized that “we are in this together.” OCS’s principal goal is to help during times of crisis by meeting emergency needs and assisting in recovery; this goal is shared with other ACF offices and across the federal government. She described this as an inherent component of OCS’s history and of the tradition of community action agencies. State and local agencies that received OCS funding, particularly community action agencies, provided critical frontline communication, coordination, services, and support to low-income children and families in communities devastated and dislocated by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. In her own experiences during those hurricanes, community action agencies were on the frontlines. Connected at the local level and working in partnership with nonprofit organizations, community action agencies are equipped

with knowledge of the specific needs in their communities. She said these agencies were an on-the-ground asset that enabled OCS to have direct communication at the local level, which can be a challenge for federal agencies. Bias-Robinson said that they relied on regional administrators and ACF’s Office of Regional Operations to channel communication from frontline community action agencies to OCS.

Bias-Robinson remarked that in addition to community action agencies, OCS partners with many other organizations in responding to disasters, during which coordination and communication with all available partners is vital. These include state departments of human services, health and welfare, and economic opportunity, as well as corresponding regional offices. Large nonprofit organizations, such as the American Red Cross and the United Way, are partners in disaster response. Bias-Robinson said faith-based and community-based organizations (e.g., shelters, food banks, civic organizations) often step in quickly to respond to disasters.15 Departments of education, local schools, and recreation centers also partner in disaster response. For example, during the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Bias-Robinson worked in the White House and coordinated with local District of Columbia schools to shelter children in bomb shelters located in many school buildings. She added that other federal entities, such as the Departments of Housing and Urban Development, Labor, Transportation, and Agriculture, coordinate with ACF regional administrators and HHS regional health administrators to provide disaster relief services.

Provision of Guidance, Clarification, and Flexibility for Recovery

In determining the “who, what, why, when, and how” of the overall government response to disaster, Bias-Robinson said that providing guidance and assisting in eligibility determinations are important OCS roles. In times of disaster, people experience multiple losses, such as losing their homes, access to important documentation and paperwork, and connections. OCS provides guidance to states for determining eligibility of affected individuals and for identifying allowable services and supports funded by SSBGs, CSBGs, and LIHEAP. Furthermore, OCS shares possible strategies for community action assistance to low-income individuals and families during the initial phases of relief and recovery. Identifying flexibilities and available sources of support for expanded community action service expedites access to support for individuals and families, Bergeron stated. For example, OCS helps states ascertain expenses allowable via LIHEAP and issues waivers for the purpose of making resources more readily accessible

___________________

15 Bias-Robinson noted that OCS once operated the Compassion Capital Fund to build the capacity of these small organizations.

to communities. This can apply to both the communities directly affected by disaster as well as to communities receiving displaced individuals. After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, some states that received a smaller number of evacuees, such as Nebraska, did not have the same resources as states like Texas with large numbers of evacuees. OCS worked with states like Nebraska to identify resources, clarify how to access these resources, provide strategies on how to assist families in the initial phases of disaster relief with needs such as temporary housing, and ultimately how to support families in relocation and rebuilding. She added that OCS encourages essential community action communication and coordination with key public and private emergency responders and service providers at all phases of crisis assistance and recovery.

Discussion

Collaboration with Local Organizations

A participant asked how ACF currently shares resources and education with local emergency planners and social services organizations. Bergeron said that from the standpoint of OHS, community action agencies are important partners on the ground. Many of these agencies are Head Start grantees that partner directly with others providing services at disaster sites. Therefore, ACF’s information resources often flow to other organizations via community action agencies. Bergeron said that the Head Start program is designed to partner local Head Start agencies with community organizations, which is included in OHS requirements and creates a network that provides support.

Social Services Block Grant Use During Disasters

Another participant noted that SSBGs were used in response to Hurricane Sandy and asked whether use of SSBGs in response to a disaster is an exception or considered best practice. Bias-Robinson responded that states outline their plans for how they intend to spend SSBG funds. Because there is a Child Care Bureau,16 large funding from the bureau is prioritized. In times of supplemental funding, she said there might be opportunities to use SSBGs in this way, but states determine what is needed at that point in time.

___________________

16 The Child Care Bureau was renamed the Office of Child Care in September 2010.

Features of Effective Steady-State Systems

Somers asked about features of systems that function successfully during normal times before a disaster strikes. Bergeron responded that best practices during normal times result from the learning that takes place during a disaster. As each disaster provides different challenges, each brings opportunities for learning that can be applied in addressing future disasters. She said that the objective is to be as prepared as possible to respond to disaster in a proactive, thoughtful way, rather than taking a reactive approach. Bergeron noted that the 2018 California Camp Fire disaster devastated communities and Head Start agencies, with both similarities and differences to the devastation in Puerto Rico from Hurricane Maria. She said that reflecting and growing from each type of disaster enables ACF to be even more prepared for the future.

Bias-Robinson emphasized the value of knowledge within an organization. She cited the strong OCS knowledge base during Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, built from the experiences of individuals who had served for a long period of time, seen a number of disasters, and had learned from those events. “While every disaster is unique, we do not have to recreate the wheel every single time,” she said. Clear coordination, guidance, access to information, and decision making are what are needed from government offices during disasters. She added that time is lost when people are not informed, so when an agency has information, it needs to take action.

Bergeron provided the recent example of OHS’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In March 2020, Head Start programs began shutting down nationwide for an undetermined duration. Bergeron said that her immediate concern was the 250,000 Head Start employees who needed to be paid. Even though the doors of centers were closed, Head Start continued providing services, and she wanted to ensure that employees continued to be compensated. As an example of how preparation from previous disasters allows for prompt support, she described how OHS used flexibilities that were implemented in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria that allowed for a nimble, quick response that prevented anyone from missing a paycheck, she said.

Effect of Disaster-Related Trauma on Children

Lavin stated that in her previous work at ACF and in emergency preparedness, she has learned that children are more significantly affected and at greater risk during a disaster than adults. She asked what ACF, private organizations, or faith-based organizations have done to ensure that children’s needs are met during a disaster and to tailor services to this population. Bergeron replied that addressing trauma and adverse childhood

experiences (ACEs)17 is built into the Head Start program. She said that while disasters can be an obvious source of adverse effects on children, most Head Start programs serve children experiencing less visible underlying issues on an ongoing basis. Therefore, the trauma-informed care that OHS incorporates into its regular programming better prepares it for this aspect of disasters. Bergeron noted the trend in K–12 education of providing professional development on trauma-informed care to entire teams of staff rather than solely to professionals with mental health training. She said this trend better prepares education professionals to identify and appropriately respond to signs of trauma in children.

Agreeing that the child response to disaster looks different than the adult response, Bergeron said that sometimes children express themselves in ways that may require paying close attention to understand. In an example of Puerto Rican students responding to thunderstorms, she noted that child care workers had to be aware that when children had a hard time during storms, it was because they were associating thunderstorms with the horrible experience of a hurricane and they could not yet separate it from more mild weather events. Bergeron said having resources on hand enables organizations to respond swiftly, which she sees as a focus of all ACF programs that deal directly with children. Furthermore, in the general community, there is typically a greater connection to mental health services for both children and adults. She noted that in the past few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been creative uses of technology and tele–mental health outreach, which is a way to stay connected with children and make sure that they are taken care of.

Multilevel Collaborations in Child Services

Somers asked for specific examples of youth and children services provided via successful collaborations at the federal, state, and local levels. Bias-Robinson cited her experience as chief of engagement for the District of Columbia Public Schools and the role of schools in responding to disaster. She said the school system worked directly with the mayor and in consultation with others in the region to determine a response, and they communicated the status of children to the mayor. School systems can play a critical role as a first point of dissemination by communicating to children through their parents and via other networks. She added that including schools is critically important to the disaster recovery process. Schools can be used as communication channels, and many children and families receive services through schools, including health and mental health services in

___________________

17 More information about ACEs is available at https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/index.html (accessed October 23, 2020).

some cases. In the response to COVID-19, Bias-Robinson said she has been consulting with schools in the District of Columbia and Maryland to help them remain connected to their families, as this is the basis and foundation of how families receive information and support. Often, families trust their schools and school leaders to deliver these services, she concluded.

Bergeron said the message of the importance of schools cannot be overemphasized. Going where affected people are is the “whole point” of disaster services, and schools are where people are. She said that OHS has made efforts to better align early education—predominantly via Head Start—with school systems to create one response stream rather than separate, siloed responses for children younger than 5 years and those older than 5 years. Bergeron stated that better alignment would improve the effectiveness of responses to children in disasters.

Incorporating Adverse Childhood Events into Disaster Response Systems

A participant asked how the ACE framework has affected ACF’s infrastructure and systems design for addressing the needs of children and youth before, during, and after natural disasters. Bergeron said that a recent example is the listing of trauma-informed care in OHS funding for quality improvements, indicating that resources need to be designated specifically for that purpose. She said trauma-informed care applies before, during, and after a disaster. Programs aligned with ACEs and that train their staff are programmatically prepared for dealing with the trauma of disaster. She said that she is not able to speak specifically about other offices’ particular approaches to ACEs, but in general, there is a better understanding of the effect of trauma on brain development and on the importance of funneling resources toward mitigating those effects. This includes specific approaches with proven outcomes that enable professionals to be more responsive. From her experience in education, Bergeron said teachers often do not have a repertoire of trauma training; thus, many people interacting with children need that support. She therefore concluded that preparation is not solely about the child, but rather about the entire operation.

This page intentionally left blank.