2

Assessing U.S. Nuclear Forensics: Findings, Recommendations, and Conclusion

2.a THE NATIONAL TECHNICAL NUCLEAR FORENSICS MISSION

The United States uses its early warning system and a robust and reliable retaliatory nuclear and conventional counterstrike capability to deter overt attack from states with nuclear weapons. Deterrence of a covert, undeclared, or disguised nuclear attack, or the smuggling of material or devices needed to carry out the attack, requires the ability to identify who is responsible and the knowledge that the perpetrator will be identified in a timely fashion. By analyzing interdicted nuclear material, an interdicted nuclear device, or the signals and debris produced by the device after it is used, nuclear forensics supports attributing who provided the materials and expertise used to make the device and helps to determine the history of those materials and nature of the expertise. National technical nuclear forensics (NTNF) goals include enhancing deterrence and enabling prevention with credible, publicized NTNF capabilities. Those capabilities are implied publicly in part by, for example, U.S. national laboratory experts’ relevant and significant scientific academic publications. National Security Presidential Memorandum 35 (NSPM-35) includes as a primary objective to “convey the message to potential adversaries that a nuclear or radiological attack will be investigated and attributed to the state, terrorist group, or non-state sponsor responsible” (NSPM-35, 2021, p. 4).

The deterrence value of nuclear forensics has increased in importance since the end of the Cold War. This is due to the multiplicity of states with nuclear weapons, an increase in states with emerging or latent nuclear capabilities, interdictions of fissile materials outside of regulatory control that indicate the existence of a black market for such materials, the proliferation of terrorist organizations that might use nuclear weapons if they could, and the increased interest that some nations have shown in harboring terrorist organizations to execute attacks on their behalf.

FINDING A.1: A robust NTNF capability is an important element of deterring, preventing, and responding to an unclaimed nuclear attack or smuggling incident, much as the nuclear weapons enterprise deters overt nuclear attacks and offers response options if that deterrence fails.

FINDING A.2: U.S. nuclear forensics and attribution efforts are currently focused on preventing attacks in the United States. However, the United States would have an intense interest in the attribution of nuclear attacks or attempted attacks that occur anywhere in the world. The United States may be obliged to respond to attacks on allies as if the attack were on the United States itself. (One priority would be to assess the likelihood of subsequent attacks against the United States, and to attempt to prevent those attacks.) U.S. nuclear forensics and attribution capabilities may be required to prevent retaliation against the wrong country or to

limit escalation. International collaboration (observation, collection, and cooperative activities) is key to better global forensics, attribution, and deterrence.

RECOMMENDATION A.1: The United States should further develop global sensor and material collection networks and global forensics capabilities, preferably in partnership with allies.

There are several multilateral sensor networks, such as the International Monitoring System of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization, which can provide valuable information in the event of a nuclear attack. Implementation of Recommendation A.1 could also take the form of support for materials collaborations with the United Kingdom and France through bilateral exchanges that already exist.1

2.b THE STATE OF NTNF

The 2010 National Academies report described the U.S. government’s nuclear forensics operations and analysis capabilities as substantial but not yet operational.2 The current committee assesses that U.S. nuclear forensics capabilities have further advanced since that time, but that the program is undergoing significant reorganization, and remains under-resourced in most areas.

FINDING A.3: U.S. NTNF capabilities have advanced since 2010 and received increased funding until 2016. Without sufficient and consistent leadership, support, and priority by the White House, NTNF agencies, and Congress, U.S. NTNF capabilities will atrophy.

There have been advances in both the technical and operational aspects of the U.S. NTNF program since 2010. Scientists at the national laboratories and at universities have developed new and improved techniques for characterizing nuclear material and devices. Scientists and federal program staff are continuing to populate databases and archives. Federal program staff and laboratory managers have established new emergency operations centers with the ability to handle and communicate different levels and types of classified information. The attribution support timeline has improved, although there have been recent organizational setbacks. Many of the improvements for post-detonation analysis have been achieved after the Air Force Technical Applications Center (AFTAC) and the laboratories that support it examined the detection-collection-analysis task list and found potential efficiencies, including work that can be done simultaneously. The committee applauds this effort and endorses this and future systems-level approaches to identify additional opportunities to improve results through increased efficiency. In addition, improvements in techniques, driven by additional investment in research and development (R&D) and infrastructure, will also be needed to further improve timelines and accuracy. Clear requirements developed by the consumers of NTNF information will be useful to identify the improvements that, if achievable, would make a significant difference. These advances are important and many of them are highlighted in this report summary.

___________________

1 2010 Report Recommendation 8: “As the U.S. government organizes and enhances its databases and nuclear forensics methods, the Executive Office of the President and the Department of State, working with the community of nuclear forensics experts, should develop policies on classes of data and methods to be shared internationally and explore mechanisms to accomplish that sharing” (NAS, 2010, p. 53).

2 2010 Report Finding 1: “The United States currently has substantial nuclear forensics capabilities. However, the U.S. nuclear forensics capability [in 2010] is not yet an operational program” (NAS, 2010).

As the committee was gathering data and writing this report, Presidential policy guidance designed to replace a previous Obama administration Presidential Policy Directive was being developed. Signed on January 19, 2021, NSPM-35 and the Implementation Plan transitions several of the DHS’s NTNF roles to the NNSA and codifies existing interagency and National Security Council (NSC) entities to provide the primary oversight, guidance, and coordination for the NTNF program. Congress was also considering language for legislation to transition the legal authority for interagency coordination of the NTNF Center from DHS to NNSA.3 Under this new structure, NNSA leadership and those overseeing the NTNF program at the NSC level will need to ensure that intra- and inter-agency communication, coordination, and cooperation function smoothly. NNSA communicated to the committee in September 2020 that it plans to consolidate some of the NTNF functions currently housed in different offices in NNSA into one office, which may help; colocation sometimes improves collaboration.

RECOMMENDATION A.2: To support nuclear deterrence through a robust attribution capability, the NTNF program must be sustainable. The Executive Office of the President should issue a policy memorandum or policy directive elevating the importance of NTNF within the national security enterprise, stating that the mission of the program is both national and global, driving the need to detect, analyze, and support the attribution of nuclear events domestically and worldwide. Following the issuance, the NSC should direct, coordinate, and oversee actions to demonstrate commitment commensurate to that importance.

The policy memorandum or directive should (1) state that preventing, deterring, and responding to an unclaimed or unattributed nuclear attack is a national priority similar in type if not in scale to deterring and responding to an overt nuclear attack; (2) state that a robust and improving nuclear forensics capability is essential for attribution and deterrence of such an attack; (3) provide coordination authority for multi-agency activities contributing to nuclear forensics to an agency with the requisite expertise and commitment as a core element of its mission; and (4) commit to seeking stable funding adequate to support the development and deployment of the necessary technology and facilities and to sustain a cadre of experts that are devoted to the mission. The newly issued NSPM-35 is a good start and does most of these things.

If U.S. leaders agree that a robust NTNF program is an important element of deterring, preventing, and responding to nuclear incidents, then more must be done to support, sustain, and advance the program. The committee does not have a specific estimate for the appropriate size of the program—that should come from the process described in the recommendations below—but it is certainly larger than it is now. The NTNF mission is too important to depend solely on inconsistent R&D funding and laboratory overhead budgets generated as residuals from the nuclear weapons program as it has in the past.

To support item four above, the NTNF federal agencies, the Office of Management and Budget, and Congress will need to know what is needed—personnel, facilities, equipment, R&D—for a vital, operational program that is effective and sustainable for the long term. A description of needs

___________________

3 H.R. 6596 proposed to realign the federal nuclear forensics and attribution activities from DHS to the Department of Energy (DOE) (NNSA), renaming and outlining the mission of the coordination entity the “National Nuclear Forensics Center” to replace the National Technical Nuclear Forensics Center (NTNFC). The bill also proposed to expand NNSA’s university program to include nuclear forensics expertise. It did not receive a vote and signature in 2020 and so would have to be reintroduced in a new Congress.

can then form the basis for a plan to meet those needs and a corresponding budget. Effectiveness has to be evaluated against requirements (addressed in Section 2.e, Vision and Goals) and the needs of the consumer of the results. Sustainability is difficult to evaluate, but it is reflected in whether the capabilities are seen to degrade, maintain, or improve over some timeframe (perhaps five years) at level funding.

RECOMMENDATION A.3: In its annual report to Congress, the NTNF program should provide a description of the steps needed to make the program more effective and sustainable.

2.c WAYS TO IMPROVE NTNF AND A VISION FOR ITS FUTURE

A program benefits when its mission, objectives, and requirements are clear and flow through the program, guiding decisions about what work to undertake and what levels of effort are needed, with regular assessments of the program to identify where improvements are necessary to achieve the mission. If the NTNF program is given a high priority and equipped with a clear mission that establishes goals and strategies, NTNF entities will be better enabled to fulfill that mission. A mission-driven approach is especially important in a multi-agency, multi-actor program such as NTNF to help with coordination and cooperation and also with focus and commitment. Commitment to the NTNF program mission has been inconsistent.

The Executive Office of the President, federal agencies, namely NNSA, the Departments of Homeland Security, Defense, Justice, and State, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the intelligence community, and Congress should take the steps listed in the following recommendations concerning interagency functionality, vision and goals (and timeline), assessment, implementation, and operational capability.

2.d INTERAGENCY FUNCTIONALITY

An old adage states that “hard times clarify priorities.” One way of understanding agency priorities, and where support might best be placed in the future of a government program, is to review where support for the program has persisted the longest, even through hard times. That is often the location of the most dedicated program supporters and program personnel. For the nuclear forensics program, the stalwarts have clearly been NNSA (and the DOE national laboratories), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and AFTAC. As legislated changes to the nuclear forensics program are considered, moving national accountabilities, programmatic authorities, and sufficient funding to NNSA, FBI, and AFTAC can be looked upon as an opportunity to simplify and improve the federal leadership of the nuclear forensics program.

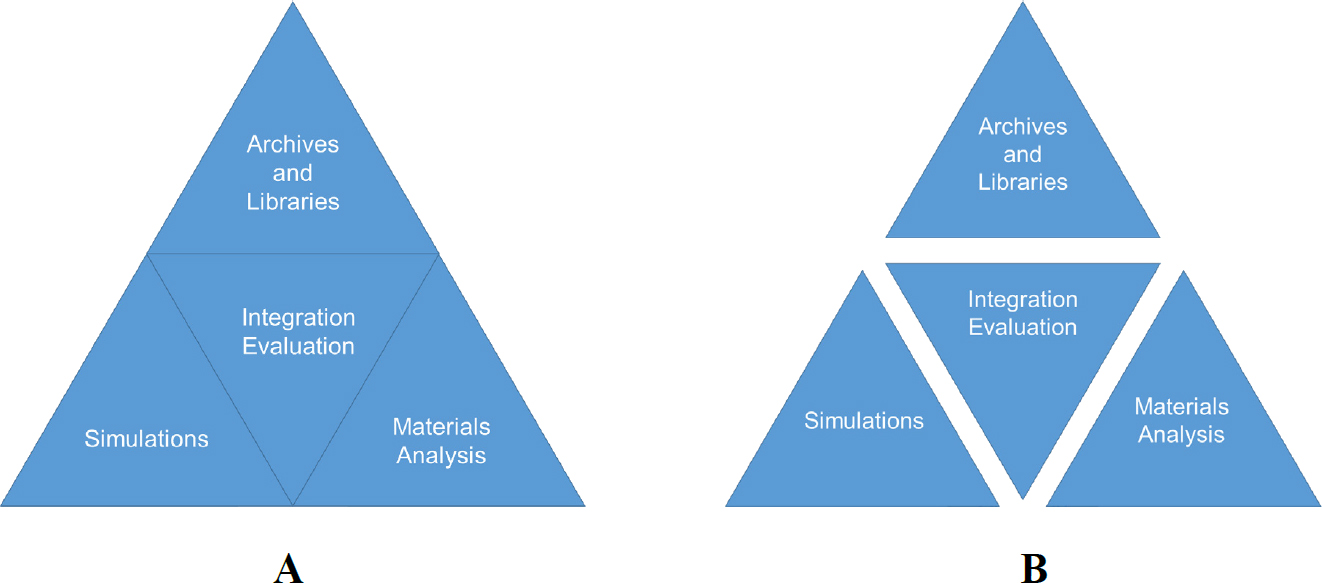

The committee emphasizes the need for coordination, clarity, and consistency of goals, requirements, strategy, and implementation because NTNF responsibilities are shared among several agencies. When one agency owns the whole mission, it is simpler for the agency to take an integrated view and ensure that the functions interface well. When different agencies or funding streams are responsible for the different pieces or parts of the different pieces, the functions do not change, but it is more difficult to take that integrated view. Each function is treated separately, and it is unclear who is responsible for the gaps and making sure that the functions connect across the interfaces (see Figure 2-1). Divided responsibility also creates a kind of tragedy of the commons,

where a program would like to pay for the laboratory services that support the program’s piece of the mission, but not for the physical infrastructure or routine work that supports the staff between the requests for services. A senior NNSA official who then led the NNSA nuclear forensics program described the latter problem to the 2010 National Academies nuclear forensics study committee in this way: “Everyone wants to buy wine by the glass, but the first glass is pretty expensive if you have to build the winery to get it.”

SOURCE: Adapted by the committee from a presentation at Los Alamos National Laboratory (Scott, 2019).

As noted earlier in this report, in September 2020, federal program managers described plans for the transfer of NTNF program leadership and reestablishment of NTNF capabilities. They outlined many of the steps that the committee independently and concurrently developed in this study. The findings and recommendations below provide a map for strategic planning, assessments, gap analyses, priority setting, and increased funding. Most of these elements and processes were in place and functional prior to January 2017. The findings and recommendations listed here, if followed, would make real the commitment to the NTNF mission and maintain and improve the program.

An effective NTNF interagency function could be fulfilled by an NSC sub-interagency policy committee as it has in the past, or perhaps by a national coordination office. There currently exists a Nuclear Forensics Executive Council (NFEC) at the assistant secretary level, and the NSPM-35 Implementation Plan details an effort to revive the Nuclear Forensics Steering Committee, a committee of federal stakeholders at less senior levels who would implement NFEC decisions. A functional coordination committee—the NFEC or something more senior—is necessary to properly place NTNF among competing interests and elevate attention above the authorities within the programs themselves, as well as to place the program needs in a larger context.

FINDING B.1: NTNF is a multi-agency mission with no overarching entity to provide prioritized funding guidance. The NTNF mission needs strong interagency coordination to provide clear and consistent goals, requirements, strategy, and implementation plans.

RECOMMENDATION B.1: The NFEC should coordinate development of the goals, assessments, implementation, and capabilities, and should promote interagency cooperation and functionality at all levels within the relevant organizations. An effective interagency function will have clear lines of responsibility and authority that indicate who will do what, and will hold organizations accountable for those responsibilities. Furthermore, those involved should persistently seek improvements and synergies with other programs.

To better enable the interagency process to fulfill its NTNF mission, the agencies may also need to make internal changes to better align responsibility with authority. Currently, if operational organizations like AFTAC identify operational deficiencies, they do not have direct reporting paths to seek solutions, whether they pertain to policy, personnel, infrastructure, or technology. A potential solution to this issue could be to have the AFTAC Commander report both up the chain of command in the Air Force and also to the Office of Nuclear Matters in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs, which has responsibilities and authorities relevant to nuclear forensics that the Air Force does not.

2.e VISION AND GOALS

There has been some progress since 2010 in connecting and integrating operational capabilities, due to better communication and policy guidance, but more progress is needed. Both operational and R&D programs generally are driven by documented program requirements; the requirements are essential to both assessment and program direction. However, there is no single, high-level requirements document for the entire NTNF program or even across use cases. Instead, NTNF program success is measured against a variety of metrics and goals linked to independently developed requirements from each department or agency involved in NTNF and attribution.

Program managers in the agencies and in the laboratories need coordinated, clear, and consistent guidance from the policy leadership as well as the requirements that would support their efforts to get the necessary resources for sustainment and improvement.

Establishing a program requirement is a balancing act between what is needed and desired on the one hand and what is feasible given time, resource, and other constraints on the other hand. In addition to the obvious challenges associated with finding that balance, there are implicit challenges in developing and revising requirements. In the DoD, the requirements structure is formalized and there is pressure for programs to not have any unmet requirements. This results in a deep reluctance to issue more demanding requirements, even when improvement is needed and feasible.4 Because requirements drive funding priorities, if the requirements do not push for improvement, then no funds are allocated for improvement. To implement the commitment to continuously improve nuclear forensics operational capabilities, the Executive Office of the President and agency leadership can direct the responsible agencies to revise requirements and better align them with the importance of the program and a realistic view of the demands it will face in a post-detonation scenario.

___________________

4 NTNF efforts also suffer from inherent organizational challenges. For example, the low hierarchy and less senior rank of the AFTAC commander in comparison to other Air Force and DoD entities and other agencies engaged in NTNF may create a mismatch between AFTAC’s mission requirements and its ability to address deficiencies.

FINDING C.1 A robust, reliable, clear, and consistent system is needed so that gaps and opportunities can be identified and capabilities are required to improve to better address the needs of the policymakers.

DHS (via the NTNFC) issued five-year NTNF strategic plans in 2010 and 2015, but a plan for fiscal year (FY) 2020 to FY 2024, which should have been issued by October 2019, has not been released as of April 2021. Past cross-cut budgets show funding allocation information from each of the NTNF-participating agencies listed by the strategic plan’s main objectives, but there is no indication that objectives in the strategic plan led to a coordinated plan for those budgets (CWMD, 2020). Furthermore, the National Science and Technology Council’s 2019 Nuclear Defense R&D (NDRD) report, which assesses capability and gaps and outlines R&D needs aligned with strategic plan objectives, is significantly less detailed than previous iterations (e.g., 2008 and 2011) and seems to describe the program as it should be rather than as it is (NDRD, 2008, 2011, 2019). These observations suggest that the strategic plan is not driving budgets and capabilities coordination among the agencies. Additionally, the interagency does not currently have concepts of operations (CONOPS) for pre-detonation materials and devices. The fact that practitioners and managers of nuclear forensics do not have clear and consistent mechanisms to give input to affect program direction in the future is a major barrier to improvement. The resolution of these issues requires an improved interagency function.

RECOMMENDATION C.1: An NSC Interagency Policy Committee should coordinate issuance of a high-level requirements document for the NTNF program, covering the elements of a capable, reliable, sustainable, and improving program, taking into account its interfaces with the attribution process and the other programs that feed into it. The requirements should derive from both minimum needs and goals for the capabilities of the program, agreed to at the highest level of the interagency.

The 2010 National Academies report states that the most important improvements to NTNF are increases in analytic and operational capabilities that reduce timelines and uncertainties in findings.5 This point has been noted in many other reports and current program documents recognize that this is still the case in 2020.6 The committee agrees that the goal is to increase overall confidence in findings, focusing on reducing uncertainties in ways that meaningfully inform decisions, while still striving to provide timely results (see Box 2-1). There is evidence that performance has improved, but improvements are at risk if not prioritized and funded.

___________________

5 2010 Report Finding 8: “There are numerous opportunities for the United States to improve its technical nuclear forensics capabilities and performance. The top priorities for improving the U.S. nuclear forensics program are to increase analytic and operational capabilities in ways that reduce timelines and uncertainties in findings” (NAS, 2010, p. 90).

6 For example, an NNSA report notes, “Interagency Coordination through Nuclear Forensics Executive Council (NFEC) and White House National Security Council (NSC)...Senior executive leadership communicate need to improve current timelines for TNF and attribution to match anticipated decision-making urgency in national response” (NNSA, 2020, p. 13).

2.e.i Biennial Assessment

The nuclear forensics component of the deterrent would benefit from an assessment modeled on the congressionally mandated letters on the status of the nuclear stockpile, which are written by the relevant laboratory directors and provided to the President and Congress, delivered in unaltered form by the Secretaries of Energy and Defense (GAO, 2007). These letters ensure that the current state of the stockpile, as assessed by the relevant experts at the national laboratories, rather than the federal program managers, is communicated and documented and that any deficiencies and risks are communicated and either accepted or addressed. NNSA and DoD (via the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense/Nuclear Matters) have experience conducting and communicating these assessments.

Under current statutory requirements, a Joint Interagency Annual Report for Improving the Nuclear Forensics and Attribution Capabilities (the Joint Interagency Annual Report) is produced by the six agencies and departments involved in NTNF and delivered to the President, and committees within the House and Senate.7 While valuable, these joint interagency annual reports have not adequately described the state of the program or provided sufficient input from the people that do the work, which is to say run NTNF operations, conduct NTNF analyses, maintain the workforce and the infrastructure, and perform the R&D. For nuclear forensics assessments, it would be important to have input from the leaders of the organizations that play critical roles in the NTNF mission, as well as the customer for NTNF analysis.

___________________

7 Required by Public Law. 111-140.

Under the new NTNF structure, with NNSA eventually leading interagency coordination efforts,8 directors of the DOE laboratories involved most directly with NTNF activities, along with AFTAC leadership, are best suited to regularly assess NTNF capabilities from the performer side. The Joint Atomic Energy Intelligence Committee (JAEIC), as the standing customer of technical nuclear forensic results, is best suited to describe known deficiencies and efforts under way to resolve them. These organizations are where the technical capabilities, infrastructure, and expertise reside to conduct the assessment. This assessment could be communicated in the form of a letter or letters sent to high-level government officials who are responsible and accountable for ensuring the NTNF capability and have the authority to make the necessary changes to address deficiencies in the program(s) (see Box 2-2). Such assessments and reporting would help monitor nuclear forensics program effectiveness and signal a robust capability, thus improving the deterrent aspect of technical nuclear forensics. Biennial or more frequent assessment would also increase the visibility of the NTNF program to the President and Congress through successive administrations.

The letters would be important for conveying the state of the program to senior leadership. This assessment process would guide the improvement of the program, with the goal of making NTNF more robust and reliable, leading to faster and more accurate results.

RECOMMENDATION D.1: The NTNF program should require key implementers (laboratories and operational military units) and consumers of NTNF results to conduct realistic evaluations of the capabilities, gaps, and opportunities for improvement of the program no less frequently than every two years, resulting in an assessment letter or letters from the heads of the implementing organizations to leadership in the agencies responsible and accountable for the mission, to the Executive Office of the President, and to Congress to drive an iterative process of revision for improvement. In years when full assessments are not provided, a brief update on changes in the program should be included in the annual report to Congress.

The committee envisions that these assessments would inform the plans in Recommendation A.3.

___________________

8 Assuming that future statutory changes will replace DHS with NNSA to lead interagency coordination efforts.

2.f IMPLEMENTATION

While the 2010 National Academies report recommended the creation of an implementation plan by DHS, this committee did not see evidence of such a plan.9 During the data-gathering process, the committee obtained and assessed several other program plans from individual agencies and laboratories. As noted above, DHS (via the NTNFC) issued five-year strategic plans in 2010 and 2015, and cross-cut nuclear forensics budgets from agencies with nuclear forensics responsibilities are reported each year to Congress. However, no coordinated, integrated, long-term program plan to improve NTNF capabilities was completed by the NTNFC. The committee encourages NNSA, the presumed leader of NTNF coordination and future chair of the NFEC, to complete such a long-term program plan in the future. The production of an implementation plan to support NSPM-35 is an encouraging sign, but implementation plans are needed at both the inter- and intra-agency levels.

RECOMMENDATION E.1: Based on the requirements and the biennial assessments, the NFEC should coordinate issuance of an interagency implementation plan. The agencies should also issue plans for their own organizations that are consistent with and support the interagency implementation plan. These plans should all derive from the same goals, requirements, and assessments; be consistent with each other; and be updated as necessary based on the results of the biennial assessments.

2.g OPERATIONAL CAPABILITY

The committee found only a few people in the NTNF program who could articulate what an operational NTNF capability should look like and how the elements should fit together and interact.

RECOMMENDATION F.1: The agencies involved in NTNF should work to strengthen an operational NTNF capability based on clear requirements, including the requirement to improve. This requires improving data sharing, mission-driven routine work, exercises and evaluation, sampling, R&D, quality assurance and quality control and uncertainty characterization, as well as more sustainable human resources and infrastructure. Improvements in these areas, along with an elevated national commitment to NTNF guided by the organization, assessment,

___________________

9 2010 Report Recommendation 2: “DHS and the cooperating agencies should issue an implementation plan for fulfilling the requirements and sustaining and improving the nuclear forensics program’s capabilities. This plan would represent a coordinated, integrated program view, including prioritized needs for operations, infrastructure, research and development. The plan should specify what entity is responsible for each action or program element. The plan would form the basis for the multi-year budget requests essential to support the program and its plan” (NAS, 2010, p. 86).

and implementation processes detailed above will reduce timelines, improve accuracy, and ensure that the U.S. NTNF program can respond when needed.

Details and related findings and recommendation are below.

2.g.i Data Sharing

Virtually all phases of operations of the NTNF program rely upon a broad variety of databases and analyses at different levels and types of classification.10

Consistent with the 2010 National Academies report,11 it is imperative that long before an event occurs the nuclear forensics community establish the policies and infrastructure for sharing information that enables a timely and effective response. It is a mistake to assume that barriers to information sharing would simply be lowered in the case of an event (the committee heard the phrase “the walls would come down” multiple times) without establishing and demonstrating effective procedures and infrastructure for sharing of the different types of classified information outside of standard protocols under challenging circumstances. Furthermore, post-detonation scenarios are not the only scenarios that would require data sharing and relaxation of classification compartmentalization, although Restricted Data has proven to pose special challenges. For example, for consequence management, program managers have talked about having tear lines, portions of documents that can be shared when separated from more sensitive information. Privacy-protecting query technologies are the equivalent for digital systems and might be useful for these applications. For training and exercises, they could enable exercise participants to access real classified data systems without accessing the real content.

FINDING F.1: Some efforts to improve classified information sharing have been made. The committee assesses that more work on this problem is needed.

RECOMMENDATION F.2: NNSA and the other agencies involved in NTNF should establish and periodically exercise a plan to break down classification barriers, including operating the procedures and the infrastructure, in all cases of high-consequence NTNF events. This could be done with “dummy data,” but on real systems with people who do not initially have access. This may require a review of procedural, regulatory, and architectural barriers and cybersecurity issues that may arise. Problems and barriers should be identified and removed.

2.g.ii Mission-Driven Routine Work

It is important to sustain routine work that will improve the information and tools available for dealing with incidents by better understanding past incidents. Examples include analyzing the

___________________

10 2010 Report Finding 10: “Databases are important tools in determining the possible origins and history of a material or an object. Databases populated with information relevant to nuclear forensics are maintained by a number of U.S. agencies. However, some of these databases are not shared among the agencies and are not readily accessible, which can be detrimental to performance of the program” (NAS, 2010, p. 92).

11 2010 Report Recommendation 7: “DHS and the cooperating agencies should devise and implement a plan that will permit, under appropriate conditions, access to the relevant information in all databases including classified and proprietary databases for nuclear forensics missions. This means that, when queried, the responses to the queries will be timely, reliable, and validated, and will provide sufficient relevant data and metadata to enable analysts to use them” (NAS, 2010, p. 93).

backlog of samples from legacy testing and updating the contents and formats of databases, in addition to analyzing and managing the small flow of material from real-world incidents.

FINDING F.2: The NTNF program would benefit from a more coordinated program working closely with the Nuclear Materials Information Program to consolidate knowledge of foreign nuclear materials.

Concerns over the proliferation of weapon designs and materials continue to exist, so it is important to have consolidation and cooperation between scientists and intelligence analysts working on materials related to foreign weapons programs and fuel cycles.

With a larger international diversity of nuclear materials being generated (and potentially illicitly transferred and smuggled), the need to identify additional proliferation signatures and have a detailed knowledge of foreign-source nuclear materials is apparent. The committee recommends that the NTNF program consider strengthening this work through a Foreign Nuclear Materials Intelligence Initiative (FNMII). Such an initiative could provide great benefit to the nation in terms of preparing for a potential crisis-driven need for knowledge of all nuclear materials, both domestic and foreign. It would aim to

- Broaden training of intelligence community (IC) analysts in nuclear weapon design and relevant materials—including older weapon variants and their materials as well as the current generation of U.S. weapons;

- Ensure that a subset of weapons designers and analysts in the U.S. weapons laboratories remained apprised of foreign weapon development programs, including their designs and materials;

- Initiate a series of regular meetings and workshops between NNSA’s offices of Defense Programs, Counterterrorism and Counterproliferation, and Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation, and DOE’s Office of Intelligence and Counterintelligence (DOE-IN) and other parts of the IC to share information and concerns; and

- Develop and further train technical staff on materials including staff from relevant laboratories via a “practicum” approach.

Personnel working under the proposed FNMII would perform regular analysis of nuclear materials to populate databases and to encourage interactions and information exchanges between the technical-analysis experts and analysts in the intelligence community. The initiative would seek foreign materials that span the various production methods in use.12 A FNMII would have a triple benefit: (1) Its analyses would populate the databases so that the data are available when needed; (2) it would help to ensure a robust and ready technical analytical capability by providing on going practical experience analyzing actual samples, an analytical capability that is needed to make proper use of the data in the databases; and (3) it would establish and exercise interactions between the IC and technical-analysis experts, improving coordination in a real-life incident.

___________________

12 Gathering a comprehensive worldwide set of radioactive and nuclear materials is impossible and unnecessary. An important benefit of FNMII could be an improved understanding of provenance and process signatures leading to better analytical predictions of materials characteristics. This could also identify knowledge gaps to guide experiments.

The committee does not make a recommendation on where organizationally FNMII should reside. This is an important question, but there are considerations outside of the committee’s scope and data gathering. Wherever in NNSA or DOE it resides, FNMII will need strong connectivity to offices for defense programs, intelligence, nuclear forensics, and nonproliferation. The committee hopes that the NTNF policy community will establish the program first by funding the work and then finding a sensible home within DOE/NNSA so that the work is not delayed by bureaucratic negotiations that are important but might not reach resolution quickly.

RECOMMENDATION F.3: NNSA and the IC should create a program focused on nuclear weapon-related materials. A dedicated Foreign Nuclear Materials Intelligence Initiative (FNMII) program would leverage and contribute to the archived materials to improve pre- and post-detonation forensics capabilities.

It is likely that there are additional categories of routine work that provide value to the NTNF mission. Operational and R&D program managers in the implementing organizations are probably best equipped to identify these kinds of work, and the value of this work would need to be validated by federal program managers.

2.g.iii Exercises and Evaluation

Since the 2010 National Academies report, DHS, NNSA, and DoD have undertaken pre- and post-detonation device technology demonstrations and training exercises.13 These exercises have gradually involved more parts of the U.S. government, including the IC and law enforcement, and have tested increasingly complex scenarios.

To enable more realistic exercises that test NTNF functions as intended, the NTNF program must be funded appropriately and seen by national leadership as a higher priority. The August 2019 Pathfinder exercise, originally envisioned as part of a technology demonstration and “end-to-end” exercise to test communication and information-sharing mechanisms, processes, and content in a post-detonation technical nuclear forensics CONOPS, was a positive step. Limitations made the organizers reduce the scope and the physical operations during Pathfinder, but the committee agrees with the ambitions of the activity and its implementation, even in its reduced form.

More full-scope exercises should be organized that involve the NTNF technical community with real decision makers from the policy community. Pathfinder was a step in the right direction, but future exercises should continue to be designed to be more realistic by testing the entire NTNF structure and by not providing advanced notice.14 For example, the post-detonation Pathfinder exercise could be replicated for pre-detonation materials and pre-detonation devices once CONOPS are developed for these two use cases. Nuclear forensics capabilities could also be tested during a national-level exercise. Appropriately publicizing these national-level exercises would enhance the deterrent value of the NTNF capability.15

___________________

13 2010 Report Finding 6: “Post-detonation nuclear forensics capabilities have been demonstrated in test and training exercises” (NAS, 2010, p. 88).

14 The committee understands that it is difficult to engage leaders across multiple agencies, especially at the senior policy maker level. This is not unique to NTNF exercises; there is always competition for key participants’ time in all exercises and indeed during real events. That is another reason why having a sufficiently sized and trained workforce to handle multiple demands is a key component of operational capability.

15 2010 Report Recommendation 4: “DHS and the cooperating agencies should adapt nuclear forensics to the challenges of real emergency situations, including for example conducting more realistic exercises that are

FINDING F.3: NTNF exercises serve many different purposes—training, testing, demonstration—and all are needed to assess readiness and gaps in capabilities.

RECOMMENDATION F.4: NNSA and the other agencies involved in NTNF should design exercises that are realistic and engage higher-level officials, including some that test the entire NTNF structure and some undertaken with no notice.

2.g.iv Sample Collection

Analyzing nuclear materials samples, whether pre-detonation interdicted materials or post-detonation debris, is one of the central functions of nuclear forensics. The following two subsections emphasize the importance of samples and expert guidance to NTNF analysis and the tools to ensure that high-quality samples are collected and that in-the-field observations and data are communicated at the earliest possible time.

FINDING F.4: Collection of appropriate materials samples (the right sizes, radioactivities, compositions, locations) is essential to the NTNF analysis function. Deficiencies and uncertainties resulting from the collection of low-quality samples hinder every step of nuclear forensics analysis and evaluation that follows. Collection of appropriate, high-quality samples requires planning, training for personnel, equipment, and skilled operational execution, including adapting to circumstances.

FINDING F.5: AFTAC, via NNSA, conducts in-the-field evaluation of ground samples to determine whether they are of sufficient quality for analysis at centralized laboratories. Analysts could gain some useful information from these early measurements, particularly data on short-lived radionuclides in the sample and the evolution of the sample over time. These early measurements could provide preliminary estimates of isotope ratios, which, together with the prompt data available in the first hours after a detonation, could provide an earlier starting point for device reconstruction efforts. Some scientists have suggested that additional, more powerful techniques could be used in the field, such as simple chemical separations coupled with automated gamma spectroscopy to provide some perishable data earlier in the event evolution. The committee sees additional in-the-field measurements as potentially valuable as complements to, but not substitutes for, centralized laboratory analyses, which have much higher sensitivity.

RECOMMENDATION F.5: The R&D program manager for post-detonation nuclear forensics should continue to examine opportunities for sample measurements that could be performed in the field to reduce the analysis and evaluation timelines or improve accuracy of nuclear forensics results. They should seek to develop deployable procedures and technologies.

Sample Collection: Ground

Ground-collection plans for sample collection are based on plume modeling, which is inexact and uncertain (especially soon after the event, when key inputs to the models are likely to be unknown),

___________________

unannounced and that challenge regulations and procedures followed in the normal work environment, and should implement corrective actions from lessons learned” (NAS, 2010).

so there is a reasonable likelihood that a collection team would need to revise the plan based on observations and measurements in the field. DOE scientists on the collection team are trained to understand the characteristics of the environments and types of samples that are required for high-quality laboratory analysis, which will ultimately lead to more accurate results. Samples collected without benefit of expert knowledge run the risk of introducing uncertainties to downstream calculations (e.g., by not sampling a sufficient range of elements) or even violating key assumptions made by device-reconstruction teams (e.g., by not collecting a representative range of particle sizes or missing samples that would uncover unexpected heterogeneities across the debris field). The DOE technical staff will most likely be the team member with the most expertise and experience in identifying proper locations, types, and amounts of debris materials to collect after an event. Therefore, the DOE technical expert should be a required member of the ground collection team, as opposed to an optional one.

In addition, better coordination and integration between plume models and in situ systems would be beneficial to post-detonation debris collection. NNSA’s consequence management program will be on the scene in a post-detonation environment and will be collecting data using the Aerial Measurement System, which uses gamma and neutron detectors to measure the radiation field on the ground. This additional data source could be useful to guide NTNF collections. Coordination among these elements and integration of their data would likely improve the nuclear forensics results.

FINDING F.6: Post-detonation material ground collection is currently the responsibility of military personnel from the Army’s 20th CBRNE command. DOE technical experts are available to guide the collection.

RECOMMENDATION F.6: A DOE technical expert should always be included as a key member of the DoD ground-collection team as it collects samples in a post-detonation debris field and should be responsible for choosing sample locations and amounts and for interpreting the in-field measurements of each sample to assess its adequacy. Through leadership and training, the entire ground-collection team should be given an understanding of the importance of the samples that they collect for all of the analyses and decisions that follow.

Sample Collection: Remotely Operated Platforms

There are strong reasons to try to improve post-detonation sample collections. Remotely operated platforms for both ground and air sampling offer advantages over in-person sampling: Remotely operated platforms reduce the radiation doses incurred by personnel, which allows mission planners to take the time needed to select the location to collect the best samples, and the collections might be more timely. The obstacles include cost, the lack of a remotely operated platform for gas sampling, the complications of trying to compare results from new sampling methods to data from past collections, and operational problems encountered in past attempts to use unmanned aerial vehicles or drones for this purpose.

Given the importance of the samples, the potential advantages of remotely operated sample collection systems, and the practical difficulties that have been encountered, additional R&D could lead to significant improvements, but only if developers work with the operators to ensure that the solutions are suited to the end use.

RECOMMENDATION F.7: The Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) should provide additional R&D funding to overcome the obstacles to using remotely operated ground and airborne particulate sampling platforms, and to translating data from newer, better collection platforms for comparison with legacy data. To better ensure that the products work in practical application, the R&D should be conducted in close cooperation with the intended users of the platforms developed.

2.g.v Mission-Driven R&D

Research and development are essential components of an effective NTNF program and are not separable from operational capabilities. Nuclear forensics operational analysis is inherently at the very low end of the work duty cycle for laboratory scientists and engineers: Very little of nuclear forensics personnel’s typical workday will be spent doing operational analysis of nuclear forensics incidents. Ongoing R&D, in addition to improving tools and techniques, is the key to both maintaining an able (trained and sharp) workforce and a workforce that is available when it is needed. An excellent workforce is essential to an excellent program. R&D attracts a talented technical workforce, enables personnel to maintain and improve the skills needed to conduct nuclear forensics analysis, and builds intellectual capabilities that are better able to analyze unfamiliar or anomalous results.

A successful nuclear forensics program needs to improve continuously in order to retain scientific staff and develop and integrate new capabilities to keep it current with other systems (e.g., wireless communications). The NTNF program should continuously be striving to improve its capabilities.

Based on the 2019 Joint Interagency Annual Report and many earlier reports, the goals for the NTNF R&D program are to

- Decrease the time required to produce reliable results (as fast as possible);

- Increase the accuracy of results (no mistaken attribution);

- Provide national and global coverage (fast and accurate for events anywhere); and

- Train and support a cadre of experts that can provide surge capacity in case of an event.

There are many examples of R&D that could improve NTNF capabilities toward these goals. Some examples include new tracers for materials analysis, use of longer-lived nuclides and decay products for paleo-forensics, fast chemical separation methods, analytical approaches for smaller samples, faster and more uniform collection methodologies (e.g., using drones or robots) and faster in-field analysis of samples (e.g., by using gamma spectroscopy, perhaps after simple chemical separation, to provide preliminary analysis data to drive earlier device reconstruction efforts), analytic techniques that require less or almost no sample preparation, and more extensive analysis of foreign devices to produce outputs beyond yield (such as isotope ratios in debris), which would make foreign device intelligence work more useful for forensics.

An integrated evaluation of current and desired future capabilities, along with a cost-benefit prioritization, will help program managers decide how to invest in R&D to enhance the programs’ utility for attribution and for meeting the needs of national leadership. Further R&D is necessary to simply stay current with technology maturation and improve transfer to operations.

It is not clear who can and should be responsible for later-stage technology development, but that organization needs technical capability, connections to the end users, experience overcoming the

challenges in readying technologies for production and deployment, and sufficient funding to support this technology transition process.

The new U.S. NTNF organizational structure, presumably with NNSA as the lead agency, will have fewer agencies participating in R&D efforts, which is an opportunity for NNSA to clarify the flow of requirements and focus on filling capability gaps.

FINDING F.7: NTNF R&D is the foundation for nuclear forensics capability and underpins human resource development.

RECOMMENDATION F.8: The administration should size the NTNF R&D budget so that R&D improves operational nuclear forensics capabilities. R&D is also needed to help attract and retain nuclear forensics personnel by providing work that keeps their skills sharp and keeps them available for the mission. R&D budgets should therefore be aligned with human resource needs to sustain an operational NTNF program. The overlap in technical expertise with the weapons programs can be used to advantage here.

RECOMMENDATION F.9: The NSC Interagency Policy Coordinating Committee for Nuclear Forensics (or its successor) should agree on and formally task one or more departments or agencies with the responsibilities and resources (human and financial) for the ongoing mission of moving technology improvements through the often rocky transition between R&D and operational capability. This should be done as soon as is practical.

Mission-Driven R&D: Reaction Time History

Measurement of reaction-time history for nuclear detonations worldwide can be improved, especially in high-value locations. Experts in weapon design emphasized the importance of reaction-time history measurements for device reconstruction.

FINDING F.8: Broader application of reaction-time history measurements may shorten the time required to accurately determine the design of a weapon that was detonated.

The United States sustains a set of sensors on GPS satellites and ground-based support equipment for the nuclear detonation detection system, USNDS, which can be useful for some nuclear forensics scenarios, but they cannot measure reaction-time history. One possible solution might be to place advanced sensors on GPS satellites or less sophisticated sensors on small satellites in low earth orbit or on airships or balloons. Some signals are difficult to measure by satellite—clouds or the ionosphere block or filter them—but some observations are possible, so current nuclear detonation sensor systems and those in R&D focus on what can still be observed through these barriers, either separately or in combination. Another possibility might be electromagnetic pulse sensors that could be placed on commercial aircraft. The feasibility of these potential solutions remains unclear; the U.S. government should sponsor a systematic study to examine the feasibility of measuring reaction-time history using the phenomena associated with a detonation and of the different platforms that could be used for the measurements.

RECOMMENDATION F.10: DTRA or NNSA should provide research funding to conduct a systematic study to identify, assess, and develop approaches to measure reaction-time history on a national or global basis.

2.g.vi Quality Assurance/Quality Control and Uncertainty

Quality management is a critical element of laboratory analysis and indeed the whole lifecycle of nuclear forensics, from planning sample collection to communicating results. The validity and quality of nuclear forensics operations and nuclear forensics technical analyses contribute to scientific rigor which can increase confidence in the analyses that are provided to policy makers.

Although guidance on quality assurance/quality control standards and methods of communicating uncertainty already exists, it was not clear to the committee that the laboratories always assess and communicate uncertainty in a uniform manner.

The 2010 National Academies report noted tension between collection efforts for technical nuclear forensics and the steps required for proper forensics science evidence collection and preservation to support criminal prosecution in court (see Box 2-1). Since 2010, great effort has been made to improve the ability to do technical work quickly and safely while maintaining chain of custody and evidentiary standards. For example, the Radiological Evidence Examination Facility at the Savannah River National Laboratory provides an extraordinary capability for the FBI to examine radioactive evidence while maintaining evidentiary chain of custody.

FINDING F.9: Uncertainties are inherent in analyses and measurements, because of both experimental imperfections and limits to our understanding of the phenomena involved. However, the means by which these uncertainties are calculated and expressed vary across the NTNF program.

RECOMMENDATION F.11: NTNF practitioners should continue to adhere to standards and procedures of modern forensic science and recommended means of measuring uncertainty. The practitioners should continue to define/identify methods for communicating uncertainty and incorporate them uniformly across the laboratories and agencies involved in NTNF, with a focus on providing accurate information to decision makers who have little or no background in the scientific disciplines relevant to nuclear forensics.

2.g.vii Improved Human Resources and Infrastructure

As noted elsewhere in this report, DHS and DTRA repurposed funds away from nuclear forensics due to the Trump administration’s national security policies and guidance. One shift apparently precedes 2017. After the 2010 National Academies report was released, efforts were made to increase the number of technical nuclear forensics experts. The DHS-funded Nuclear Forensics Graduate Fellowship Program (NFGFP) functioned for several years and produced many new technical nuclear forensics specialists for the national laboratories. In 2015, DHS concluded that it had met its goal for bringing new radiochemists into the NTNF program and so terminated recruitment of new students for the program, shifting focus to later in the workforce development pipeline. This was a surprising decision and the justifications given by DHS were that (a) they had met a milestone erroneously attributed to the National Academies, and (b) that one of the graduates was unable to find a position within the NTNF program. However, the replenishment of human resources is not a one-time need, as experienced staff retire or move to other projects. Also, there are many reasons why a graduate might not be hired, so the inability of a single graduate to find employment within the program is not an indication that needs have been met.

Adequate staffing levels and pipelines must be maintained to ensure current and future NTNF functionality. Furthermore, sizable staffing is required to maintain a strong technology adoption

rate, including disruptive technologies adopted for NTNF. Finally, inconsistent funding of the student pipeline sends the chilling message to academic faculty and potential students that this mission is transient, unimportant, and a risky career choice.

FINDING F.10: There is and will be an ongoing need for new staff as long as the nuclear forensics mission continues. How many new staff are needed depends on program needs and how long current staff plan to remain in the program, but it is appropriate to have a modest oversupply of new talent.

RECOMMENDATION F.12: To attract and retain an excellent workforce with the diverse skills needed for this mission, the agencies involved in NTNF must establish rewarding career paths with reliable, satisfying, and valuable work, and reestablish the educational and R&D investments that were supporting NTNF.

NNSA should reconstitute the graduate student pipeline (i.e., NFGFP) and should use funding models and provisions best suited to building the nuclear forensics expert community. This means using not only the current consortium model, which concentrates efforts to gain the benefits of affiliated groups, but also student and postdoctoral fellowships and individual grants to principal investigators to support new ideas and talent outside of the consortia.

NNSA should not retain the requirement from the previous DHS program that students emerging from these programs must work in a NTNF field post-graduation. The technical expertise acquired by these students, in particular radiochemists, naturally encourages employment in the nuclear field, and NNSA should not be obligated to find federal employment for all graduates. This restriction discourages further production of students to support the nuclear forensics workforce. Instead, workforce needs should be assessed and adjusted annually by NNSA. Adjustments may be needed based on specificity of study. For example, if a student pipeline program is producing computational nuclear engineers, perhaps requiring that they work in the nuclear field after graduation is appropriate, as computational nuclear engineers frequently have high-quality opportunities working for tech firms (e.g., Google, Microsoft).

Nuclear forensics funding patterns are having an impact on infrastructure as well as personnel. An increase in funding led to investment in infrastructure, while a drop stopped the investment.

FINDING F.11: Because much of the infrastructure and equipment for nuclear forensics is shared with other missions, special focus and resources are required to ensure adequate support for and prioritization of nuclear forensics capabilities.

CONCLUSION

The conclusion of the 2010 National Academies report notes that a terrorist nuclear attack is “the most catastrophic threat the nation faces.” Recent events indicate that the need to deter nuclear threats and attribute an attack in the event that deterrence fails has not abated and may be growing (Tilden and Boyd, 2021). As noted in this report, a credible nuclear forensics enterprise is essential for deterring nuclear trafficking and attacks and supporting attribution after an attack. Nuclear forensics capabilities, along with engaging international partners and a robust and credible monitoring, detection, and verification enterprise, can help empower leaders to make informed decisions about nuclear threats on short timelines.

Ensuring that the United States has credible and robust nuclear forensics capabilities—a strong nuclear forensics community integrated into an attribution mechanism that embraces all components (i.e., technical nuclear forensics, the intelligence community, and law enforcement) in collaborative engagement that is routinely exercised and that evolves with threats—requires strong sustained leadership along with thoughtful and strategic investment of adequate resources. Nuclear forensics capabilities are an essential element of U.S. national security. A more unified vision, more consistent, reliable support, and a more effective and coordinated program is necessary to serve that critical mission.