4

Caregivers: Diversity in Demographics, Capacities, and Needs

The first person to recognize subtle or significant changes in a person’s understanding and experience of the world is generally not a health care professional but a family member, coworker, or friend. Common early changes associated with dementia include trouble managing finances and/or medications, difficulty driving and/or way finding, mood changes, memory lapses, and repetitious speech, all of which are more likely to be apparent outside of the medical setting. While some may recognize their loved one’s difficulties as possible signs of early-stage dementia, others may perceive these changes as ordinary aspects of aging. For those many persons who are developing cognitive impairment while living alone and who have limited contact with family, such changes may go undetected for longer.

This chapter discusses the work of the family members and others who support people living with dementia. These caregivers, who are generally unpaid, may be family members, friends, neighbors, or coworkers. The term “family caregivers” is used here to include the potentially large network of those who provide support and to distinguish them from those who are connected to the person with dementia through the formal health and direct care systems. The chapter provides an overview of the crucial work that family caregivers provide and their diverse demographics, experiences, and needs for support and training. It summarizes the current state of research on interventions to support caregivers, focusing on care transitions, the potential and actual use of technology, and symptom control.

Many people with dementia never receive a diagnosis, but family members and others provide support and care regardless. Even for those whose

dementia has been identified, family caregivers are often uncertain how they should help. It may be difficult for them to find resources and educate themselves about the disease. Family members must navigate complex health systems and put care plans in place. They search the Internet and/or call friends who have provided care for a loved one with dementia, hoping to learn how to support their own loved one and themselves. Cultural norms, access to resources, education, and an understanding of dementia can influence the family caregiver’s perception of the challenges of dealing with dementia, but there is no doubt the challenges are considerable.

To better understand the challenges facing family caregivers, the committee explored what is known about the care they and others provide. We also sought insight into caregivers’ perspectives on their experiences and the supports that would benefit them most. We are indebted to the advisory panel that supported this study (see Chapter 1) for their contributions to our understanding. In addition, we examined the available research on and reviews of interventions and programs to support family caregivers and existing policies that can bolster such supports. Finally, we relied on a paper by Gitlin and colleagues (2020) commissioned for this study.

RELIANCE ON FAMILY CAREGIVERS

The early and middle phases of dementia typically last much longer than the final stage (see Chapter 3); most family caregiving occurs during those earlier phases, but caregiving can become more intense as the dementia progresses. During the earlier phases, people living with dementia typically remain in their homes, and if they receive care, it is in the home or in other community settings. All people turning 65—not just those with dementia—have a 70 percent chance of needing long-term care for some period of time, and half of this care is unpaid (Johnson, 2019). For those with dementia, 85 percent of care in the United States is provided by unpaid family members (O’Shaughnessy, 2014). Many family members embrace caregiving and view it as part of their identity, as well as a source of satisfaction, but because the United States lacks an adequate and dependable system for identifying and financing long-term services and supports, some family members find that they have no real choice.

In the United States, and indeed globally, there is a societal expectation that family members will provide care to their loved ones with dementia if they can, although cultural expectations and resources affect these decisions. In short, family caregivers fill a very substantial gap in care. This has been true historically, is the case currently, and will be the case into the future (Gitlin et al., 2020; Gitlin and Wolff, 2012). It is also true around the world—in low-, middle-, and high-income countries; in families of all

socioeconomic levels; and among all racial/ethnic groups (World Health Organization, 2017).

The need for family caregivers is increasing as the population ages, and even as the pool of those who could provide such care is shrinking (NASEM, 2016). People over 80 make up one of the fastest-growing segments of the population (Ortman et al., 2014) and the group most likely to require help (Ortman et al., 2014). At the same time, the population of those who can provide care will shrink as a result of changes in family structure and social norms, including lower fertility rates and smaller families, as well as higher rates of childlessness, never-married status, female participation in the formal workforce, and divorce (Redfoot et al., 2013). These overlapping shifts affect women in particular, who make up two-thirds of family caregivers (Kasper et al., 2014), creating a perfect storm in which more people will live longer with dementia and need support while fewer family members will be there to help. Indeed, many of those living with dementia will be living alone.

In 2011, 92 percent of people over 65 in the United Sates were living in the community, not in a facility, according to the National Health and Aging Trends Study (Toth et al., 2020). Of those receiving assistance with basic and instrumental activities of daily living,1 nearly all relied on some help from family or friends, and almost two-thirds relied exclusively on these unpaid caregivers (Friedman et al., 2015). Results of the companion National Study on Caregiving indicate that in 2011, an estimated 17.7 million individuals were caregivers for an older adult who resided at home, in the community, or in a residential care setting (other than a nursing home) (Freedman and Spillman, 2014). Nearly one-half of these caregivers (8.6 million) provided care to a high-need older adult, defined as an older adult who had dementia and/or who needed assistance with three or more activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, eating, getting in and out of bed) (NASEM, 2016; Spillman et al., 2014).

The economic value of this caregiving is extraordinary. In 2018, caregivers of people living with dementia provided an estimated 18.5 billion hours of unpaid assistance, valued at $290 billion (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019). It has been estimated that families cover (through a combination of unpaid care and spending on care) 70 percent of the average cost ($225,140) incurred in the course of an individual’s illness (Jutkowitz et al., 2017); the remainder is paid for by Medicare and Medicaid. (See Chapters 6 and 7 for more on these issues.)

___________________

1 Clinicians use the terms “activities of daily living” (such basic tasks as personal hygiene, dressing, feeding, and moving independently) and “instrumental activities of daily living” (activities that support independent living, such as cooking, cleaning, transportation, and managing finances) to characterize the functioning of people living with dementia.

Family caregivers may provide care for relatively short periods or for many years. They may devote a few or many hours each day or week to providing care. According to 2011 data from the National Study of Caregiving, the median number of years a family caregiver provided care was 5 years, and nearly 70 percent provided care for 2 to 10 years (NASEM, 2016). “Caregiving trajectories” is a term researchers use to characterize the way the caring role evolves over time, depending on the care needed and the setting in which it occurs (Gitlin and Wolff, 2012; Peacock et al., 2014; Penrod et al., 2011). One important role for caregivers is coordinating transitions across all settings, providing communication that links different providers, as their family members may move back and forth from home to hospital to rehabilitation or skilled nursing facilities.

Family caregivers are most often spouses, adult children, or siblings, although other relatives, neighbors, friends, members of a shared faith community, and others also provide care without pay. As noted above, even though many fewer families now include women who are not employed outside the home than in the past, females remain the main source of caregiving (Sharma et al., 2017):

- One-third of family caregivers are 65 or older.

- Two-thirds are women, and two-thirds live with the person who has dementia.

- One-fourth provide care both to an aging relative with dementia and to children under the age of 18.

Most caregivers still need income and must juggle their caregiving with work schedules and other responsibilities, including child care (NASEM, 2016; DePasquale et al., 2016).

Family caregivers reflect the country’s diversity. As the U.S. population becomes both more diverse and older, the percentages and numbers of older people and people with dementia in minority communities are increasing. As discussed in Chapter 1, available data show that members of minority populations are more likely to develop dementia relative to their non-Hispanic White counterparts. Rates of family caregiving vary modestly across racial/ethnic groups, according to survey data, with caregiving being most common among Hispanic populations (Family Caregiver Alliance, 2019). Gender and family roles, cultural expectations, and proximity are among the factors that lead to one family member rather than another taking on the caregiver role (Cavaye, 2008). For instance, caregivers in African American families are less likely to be a spouse than are those in non-Hispanic White families (National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP, 2020; Pinquart and Sörensen, 2005). Caregivers for LGBTQ people living with dementia are less likely to be formal family members (Frederiksen-Goldsen and Hooyman, 2008).

The specific help provided by family caregivers varies significantly, depending on the age of both caregiver and care receiver, the nature of their relationship, the stage of dementia, other comorbidities, and cultural context. Table 4-1 lists the range of supports caregivers provide for older adults (not just those living with dementia). For a person living with early-stage dementia, assistance may include organizing medical referrals to clarify diagnosis and prognosis, financial planning, help in identifying work and disability options for those still working, and emotional support with such challenges as declines in function or the stigma of dementia. For those living with midphase dementia, care may include all of the above plus more assistance handling bills and finances; transportation and advocacy for medical appointments; assistance with groceries, food preparation, and medications; and housing upkeep, modification, and repairs. As dementia progresses, a person will also require care that is more intimate and physical, including toileting, bathing, dressing, and feeding. Caregiving at this later stage requires longer hours and engagement with more difficult tasks.

TABLE 4-1 What Family Caregivers Do for Older Adults

| Domain | Caregiver’s Activities and Tasks |

|---|---|

| Household Tasks |

|

| Self-care, Supervision, and Mobility |

|

| Emotional and Social Support |

|

| Domain | Caregiver’s Activities and Tasks |

|---|---|

| Health and Medical Care |

|

| Advocacy and Care Coordination |

|

| Surrogacy |

|

SOURCE: Excerpted from NASEM (2016, p. 81). Copyright 2016 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Spouses, daughters, and those residing with the person living with dementia are more likely to provide this level of care (Kasper et al., 2015).

FAMILY CAREGIVERS’ PERSPECTIVES

The advisory panel appointed to support the committee provided valuable insights from family caregivers about the challenges they face (Huling Hummel et al., 2020; see Chapter 3 for discussion of the advisory panel’s insights about the experiences of people living with dementia). The paper prepared by the panel summarizes the members’ own perspectives and those of others who participated in a call for commentaries that yielded further insights into the challenges caregivers face (see Chapters 1 and 3). Like the people living with dementia who responded to this call, caregivers reported frustration with delays in obtaining a diagnosis for their loved ones, and

many observed a lack of competence and empathy in the health care professionals involved throughout the diagnostic process. One contributor commented, “No doctor would take the time to explain what is possibly expected and how the disease works.”

Caregivers reported considerable difficulties in identifying and obtaining services. Many reported frustration with government offices on aging (see Chapter 5), such as when the local office was unable to link families with paid providers. The challenge of finding paid care providers in rural areas was noted in particular. One respondent stated that the community in which she had lived for 44 years “does little” to support her husband or her. Other respondents reported their own successful efforts to create needed resources previously unavailable in their community, such as helping a local adult day service incorporate materials and programming in different languages. Some caregivers had words of praise for compassionate employers, who offered flexibility to take time off for caregiving. Nonetheless, many reported experiencing stress related to managing conflicts with their work schedules and demands.

Like persons with dementia (see Chapter 3), many caregivers faulted clinicians for the poor quality of communication about what to expect as dementia progressed and limited efforts to connect those with dementia to services and resources. Caregivers observed that many clinicians even lacked basic education about dementia. Another said, in reference to communication with doctors, “non-existent—they are not helpful or frankly knowledgeable.” One caregiver’s father had dementia without memory loss, which delayed diagnosis. During a frustrating period of going from clinician to clinician, they went to a neurologist, who “did all kinds of tests that showed there was nothing wrong with his brain. She basically shrugged and sent us on our way.”

Caregiver respondents to the call for commentaries noted multiple significant stressors associated with their role. Isolation, lack of relief, economic concerns, and sorrow were common themes. Comments included, “I seem to always be on call 24/7,” and “I don’t socialize anymore. I don’t take vacation without her.” One respondent wrote, “I had to essentially give up any interests and hobbies and focus on working and just getting through each day. I’ve lost weight, am now anxious, don’t sleep well, and am fearful about our financial situation.” Other respondents also voiced concern about finances, including the high risk of scams aimed at those with cognitive impairment, the high cost of care, and the lack of useful insurance for dementia care.

Caregivers who contributed their perspectives to the advisory panel’s work also reported positive experiences. Examples included finding a sense of meaning and importance in their caregiving work, as well as happy experiences shared with their loved ones, including working on puzzles

and games; playing with a grand- or great-grandchild; and happily sharing birthday cake, whether or not the person living with dementia recognized the birthday.

RESEARCH ON FAMILY CAREGIVING

The perspectives reported above provided a valuable backdrop for the committee’s exploration of the available research on the caregiving experience, the positive and negative effects on caregivers themselves, and the interventions that might support caregivers. There is an extensive literature on how the physical and mental status of caregivers is affected by caregiving, and how the nature of these effects varies according to the functional status of the care recipient, the hours worked, and the intensity of the work (Carpentier et al., 2010; Peacock et al., 2014; Penrod et al., 2011). Most recently, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released the report Meeting the Challenge of Caring for Persons Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners: A Way Forward, which, as discussed later in this chapter, identifies two categories of interventions for which there is evidence of benefit (NASEM, 2021). A number of prior National Academies reports—including Families Caring for an Aging America (NASEM, 2016) and Care Interventions for Individuals with Dementia and Their Caregivers (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2018)—provide relevant information. The focus here is on evidence about the caregiving experience and support and interventions for caregivers.

The Caregiving Experience

A substantial body of evidence documents both positive and detrimental effects of providing care for a person living with dementia (Gitlin et al., 2020; NASEM, 2016).2 This section briefly examines the caregiving experience and how it varies across groups and activities, and how the COVID-19 pandemic has brought new challenges for caregivers.

The caregiving experience is highly varied, as would be expected given the broad range of people, activities, and hours involved. The experience also evolves along with the stage of dementia, creating a trajectory of needs and impacts. Researchers have shown that family caregivers may experience significant stress that is apparent throughout the course of the disease: worry and anxiety that begin in the earlier stages, depression and distress

___________________

2 The discussion here relies on a paper commissioned for this study (Gitlin et al., 2020) and an in-depth study of caregiving in the United States, referenced above, carried out by an earlier National Academies committee (NASEM, 2016).

in later stages, and complicated grief when their loved one dies (NASEM, 2016; Ornstein et al., 2019). Physical strain associated with caregiving, sleep disturbance, financial hardship, and the challenge of caring for an individual who requires near-constant supervision are particularly associated with caregiver stress (Gitlin et al., 2020).

Caregivers also experience higher rates of physical illness and hospitalization, as well as reduced attention to their own health, compared with their noncaregiving counterparts. They experience financial losses from missing work, cutting back work hours, or leaving their employment, losses that affect their earnings, social security payments, benefits, and future work opportunities (NASEM, 2016). Social isolation and cognitive decline have also been reported among caregivers (Jutkowitz et al., 2017; Pinquart and Sörensen, 2003; Sörensen et al., 2006).

On the other hand, positive outcomes of family caregiving may include increased self-confidence, lessons in dealing with difficult situations, strengthened bonds with the family member receiving care, and confidence that that person is receiving good care (NASEM, 2016).

Focused research on caregiver stress offers insights into how the caregiving experience is different for different groups. For instance, spouses providing care report greater stress levels relative to adult child caregivers (Gaugler et al., 2015), while caregivers who believe the care recipient is suffering physically or psychologically are more likely to experience depression (Schulz et al., 2008). A study of African American caregivers found that, compared with other caregivers, they devoted more of their hours of care to relatives with high degrees of disability. African American caregivers also faced greater financial strain, yet they reported experiencing more gains from caregiving and were less likely to report emotional difficulties (Fabius et al., 2020). African American caregivers in this study received more help from others and from government and community resources. They also reported significantly smaller decreases in desired activities, such as visiting with family and friends.

Recent work among older American Indians echoes these findings and draws attention to the importance of accounting for race in addressing caregiver needs and proposed supports (Schure et al., 2015; Conte et al., 2015; Spencer et al., 2013; Goins et al., 2011). The research regarding American Indian and African American communities offers important insight, yet studies of the experience of minority caregivers are unacceptably few in number, a gap noted at the Dementia Summit and in a range of other reviews (National Institute on Aging, 2020; NASEM, 2021).

Caregiver stress affects the recipient of care as well. For example, one study showed that an individual cared for by a highly stressed caregiver is 12 percent more likely than a counterpart to enter a nursing home within a year, and 17 percent more likely to do so in 2 years

(Spillman and Long, 2007). There is also evidence that individuals being cared for by caregivers who are experiencing stress related to their own unmet needs are in turn more likely to have unmet care needs (Beach and Schulz, 2017), with high levels of caregiver stress having been linked to substandard care and the risk of neglect (Beach and Schulz, 2017). Another study found that such factors as anxiety, stress, and unmet care needs were associated with earlier mortality in care recipients, although the authors note that more fine-grained studies of this issue are needed (Schulz et al., 2021).

COVID-19 has brought new challenges. It will take time to adequately assess the full impact of the pandemic on those living with dementia and their caregivers. However, accounts from the United States and other nations indicate that the experience of being a family caregiver became significantly more challenging as a result of the pandemic (see, e.g., D’Cruz and Banerjee, 2020; Greenberg et al., 2020; Alzheimer’s Association, 2020). Chapter 1 notes the devastating impact of the pandemic on the elderly and on residents of nursing homes and other care facilities. Caregivers have been called upon to devise new ways of acquiring food and medicine and monitoring the health of family members with dementia without putting them at risk through normal human contact. Crucial services caregivers have provided for nursing home residents, including advocating for services, helping with feeding, organizing medical care, monitoring quality of care, and providing crucial human contact and affection, have all been compromised by COVID-based restrictions on visitation that have radically increased the isolation of people living in nursing homes (see Chapter 6).

At the same time, anecdotal evidence indicates that both formal and informal sources of support and respite (e.g., other family members, paid caregivers, day care programs) have become less accessible to caregivers during the pandemic. Data collection and research to document and analyze this evolving situation will be critical for protecting vulnerable populations and identifying lessons that can be useful in future public health emergencies. COVID has highlighted the terrible impact of health inequities on American communities in several ways. Those who were least likely to be able to work from home and maintain social distancing either at work or at home were more likely to contract COVID and were also disproportionately members of minority groups. COVID hit communities with large non-White populations brutally, with significantly higher rates of infection, hospitalization, and mortality that also hit the family caregivers in those communities especially hard (see Chapters 2 and 5 for more discussion of systemic factors and social determinants of health).

Researchers who study family caregivers often rely on qualitative studies using surveys and similar tools (NASEM, 2016; Whitlatch and Orsulic-Jeras, 2018). However, researchers find the study of family caregivers challenging for reasons that include limitations of the available data, wide variation in the nature of family caregiving and the kinds of supports needed, and the multiple ways of defining people who provide care outside of institutional settings. There are as yet no firmly established assumptions and methods to guide researchers so their results can be easily synthesized, as discussed further in Chapter 8 (NASEM, 2016).

Caregiver Capacity and Screening

The care provided by family members is so vital that it is difficult to raise the issue of assessing its quality. Nevertheless, the challenges of caregiving can be enormous, and most family caregivers likely take on this role gradually, with limited opportunities to understand in advance the full scope of what it may entail. Providing care for a person with dementia draws on a wide range of skills and competencies, including patience, empathy, and communication skills. Also required is the capacity to provide support for complex emotional and behavioral issues and to carry out nursing and related medical tasks. Furthermore, caregivers may be called upon to understand and navigate complex health care and long-term care options and to take on legal responsibilities.

Unfortunately, the limited available evidence suggests that few caregivers receive formal preparation for this role, and more than half report carrying out medical or nursing tasks without preparation, although many express a desire to receive training (NASEM, 2016; Burgdorf et al., 2020). One survey showed that family caregivers—often without training—carried out the functions of geriatric case managers, medical record keepers, paramedics, and patient advocates, filling gaps in a system that does not systematically meet those needs (Bookman and Harrington, 2006).

At present, few tools are available for assessing the nature and quality of care provided by family caregivers. Quality measures used in health care are intended to evaluate paid workers and institutions and hold them accountable. Institutions must report data related to quality measures, accept inspection, and provide remedies for any problems identified, and they face such negative consequences as reduced payments or loss of licensure. This model is inappropriate for family caregivers, who are neither paid nor licensed, and no entity has responsibility for inspecting private homes where care is provided unless abuse has been reported.

Not all family caregivers have had the opportunity to acquire the skills, tools, and education that might enhance the care they provide. Caregivers who lack understanding of the symptoms and trajectory of the disease their loved one is experiencing or strategies for addressing common problems may both experience and cause unnecessary stress, or even put their loved one at risk. For instance, a 2019 study found that family caregivers’ well-intentioned efforts may complicate interactions with health care professionals, such as when symptoms or care needs are less evident to a provider because of a caregiver’s efforts to mitigate them (Häikiö et al., 2019). More disturbing, an Internet search for “dementia restraints” provides an anecdotal indication of potential problems. Although it has been well established that the use of physical restraints for dementia patients is harmful—both dangerous and degrading—many such products are sold, and advertisements encourage their use by stressed caregivers.

While educational resources are available for family caregivers, there is limited systematic information about access to or use of these resources across groups and geographic regions. A few studies have examined available training and resources, focusing primarily on outcomes for caregivers rather than care recipients (e.g., Sousa et al., 2016; Parker et al., 2008; Hepburn et al., 2001). Because dementia symptoms may emerge gradually over a period of years, it is likely to take time for the disease to be recognized and for a family member to identify as a caregiver and begin to seek support (Peterson et al., 2016). While caregivers may be open to new

information, they may not know that such information is available at all, or where and how to seek it. Those with limited Internet access and expertise cannot easily take advantage of the abundance of web-based information. Box 4-1 provides examples of the sorts of resources that are publicly available to caregivers of individuals living with dementia.

SUPPORTS FOR FAMILY CAREGIVERS

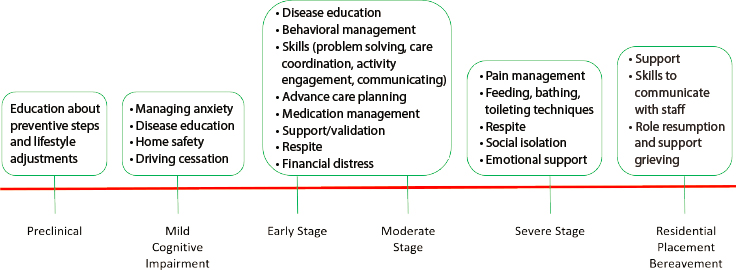

Comprehensive approaches to dementia care (discussed in Chapter 6) have focused on the key role of family caregivers and the need to provide support for them explicitly (Gitlin et al., 2020). As suggested above, caregivers need many different kinds of support, and their needs vary with the stage of the care recipient’s disease, as shown in Figure 4-1. It is also important to note that most supports for caregivers are available only once their loved one has received a diagnosis of dementia. As discussed in Chapters 2 and 3, there are significant barriers to obtaining a timely and accurate diagnosis, a problem that significantly affects the ability of caregivers to access even those supports that are available. Nevertheless, various types of supports have been developed. This section reviews the status of research on interventions to support caregivers and considers promising directions for future development addressing three key issues: care transitions, the use of technology to support caregiving, and approaches for addressing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.

SOURCE: Gitlin et al. (2020), adapted from Gitlin and Hodgson (2018).

Intervention Research

Interventions to support caregivers have been studied for decades, and work conducted in the past decade or so has included robust and methodologically sound trials. Examples include the National Institute on Aging / National Institute of Nursing Research REACH (Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health) initiatives (Phases I and II), which examined six caregiver interventions: psychoeducational group counseling, individual counseling, skills training, problem solving, technology-based education, and supportive programs (Gitlin et al., 2020).

The authors of the review of intervention research commissioned for this study (Gitlin et al., 2020) assessed research reviews published between 2000 and 2019 and identified 4,112 articles that met their inclusion criteria.3 The authors found that there is evidence for the efficacy of many different types of interventions designed to support family caregivers, including psychoeducation, counseling, problem solving, skill building, social support, and respite. These interventions demonstrate benefits for caregivers’ own health behaviors, depressive symptoms, self-confidence, well-being, and perception of burden.

Gitlin and colleagues found that the programs for which there is evidence of effectiveness share several characteristics: they are based on needs assessments and are tailored to meet specific unmet needs; and they include multiple components, such as counseling, education, stress, mood management, and skill building. The studies reviewed also reveal that caregivers have preferences about how they wish to receive support.

However, Gitlin and colleagues identify important limitations of this

___________________

3 See Gitlin et al. (2020) for detailed discussion of the literature review.

body of work. In general, effect sizes in the studies are small, so further research is needed to confirm and expand on the findings. Few of the studies shed light on the mechanisms by which the interventions may yield benefits or on factors that may moderate their results, particularly how effects may vary across groups and circumstances. Gitlin and colleagues also found a paucity of caregiver intervention studies assessing caregivers’ experiences with dementia stages other than the moderate, middle stage of clinical dementia symptoms or addressing longer-term effects on caregivers’ health or well-being. They note a lack of diversity among study participants, which further limits the applicability of the findings. Moreover, none of the studies address financial distress, physical burden, or social isolation—three key documented sources of stress for family caregivers.

Gitlin and colleagues also looked at studies examining the implementation and scaling of interventions in order to assess their effectiveness when delivered in a community or health care system. Such implementation studies are crucial to determine which interventions will actually show benefit once moved from research settings to real-world environments. Of 1,130 implementation studies the authors located, only 28 met their inclusion criteria.

From their review of the available literature, Gitlin and colleagues conclude that evidence points to “an impressive array of interventions” (p. 33) that may improve family caregivers’ psychosocial well-being. Most promising are strategies targeting caregivers of persons in the moderate stages of disease that offer education; strategies for coping, managing behavioral symptoms, and problem solving; and counseling. Benefits to caregivers are most pronounced with respect to health and health care behaviors. A number of the translational studies also show that implementation can be effective. Strategies that appear to contribute to effectiveness include engaging stakeholders, providing staff coaching, adapting a program to fit local circumstances, and integrating the intervention into daily workflows.

Overall, however, Gitlin and colleagues present a somber view of the existing research on caregiver interventions and call for significant changes to improve the quality and scale of this work. Their conclusions are similar to those presented in the paper on interventions for individuals living with dementia commissioned by the committee (Gaugler et al., 2020; discussed in Chapter 3). The existing research related to caregivers, Gitlin and colleagues found, has “many methodological (but fixable) flaws, small effect sizes, a failure to address unmet needs of families across the disease trajectory, and a failure to examine outcomes of importance to different stakeholders” (p. 3). They note a lack of attention to fidelity—the extent to which the delivered intervention matches

the original protocol or model—in the studies they examined, as well as inadequate characterization of samples and inconsistent labeling of the interventions. These flaws limit researchers’ ability to make useful comparisons across studies.

As the committee was completing its work, the National Academies released the above-referenced report assessing evidence on care-related interventions for people with dementia and their caregivers, which provides additional insights (NASEM, 2021). The authoring committee for that report relied on an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) systematic review of randomized controlled trial evidence on care interventions for persons living with dementia and their caregivers, as well as other evidence. The report notes positive developments in intervention research for dementia caregivers, and specifically the start of a crucial shift from focusing on the mere prevention of harm to the promotion of well-being and inclusion. However, the report’s authors express “disappointment that the AHRQ systematic review did not uncover a stronger, more convincing evidence base” (NASEM, 2021). The AHRQ review identified two categories of interventions for which there is low-strength evidence of benefit: (1) collaborative care models, and (2) the REACH II multicomponent intervention and associated adaptations. The committee that produced that report concluded that the evidence is sufficient to justify implementation of these two types of interventions in community settings.

Focus on Three Key Issues: Care Transitions, Use of Assistive Technology, and Approaches for Addressing Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms

To illustrate the complexity of the issues faced by family caregivers and the potential for progress, this section focuses on the three issues of care transitions, the use of technology to support caregiving, and approaches for addressing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Care Transitions

Transitioning an individual with dementia from one care setting to another—for instance, from home to hospital, nursing home, or emergency room—is often stressful for the person living with dementia and the family (Boltz et al., 2015; Shankar et al., 2014). Care transitions are associated with increased risk for significant adverse events, such as falls, delirium, treatment errors, and mortality (Callahan et al., 2012). Moreover, such

transitions often reflect poor communication and may be unnecessary (see Box 4-2).

A systematic review examined interventions to help caregivers delay transitions in care, finding that despite the importance of the issue, it has not been well studied. These researchers identified only seven papers that met their inclusion criteria. The available studies that did meet those criteria pointed to possible ways of delaying or avoiding transitions, such as

a program involving a combination of individual and family counseling and telephone assistance in problem solving that was able to delay nursing home placement among participants by more than 1.5 years (Mittelman et al., 2006). However, very little evidence has been accumulated to answer questions about when transition is appropriate, how caregivers and family members can determine what setting is best based on the individual’s and family’s preferences and needs, or what support and education caregivers need. There is virtually no research on how well the options available in communities align with the values, needs, and wishes of people with dementia and their caregivers.

Use of Technology to Support Caregiving

Technological assistance in a wide variety of forms is increasingly available to support caregiving. These include multiple smartphone apps, including those designed to provide assistance in tracking medications, appointments, and documents, as well as supports for community building and encouragement for stressed individuals (American Seniors Housing Association, 2021). Yet while such technology offers intriguing options for improving care, it also may exacerbate the digital divide given the severely limited access to online technology in many communities, including sparsely populated rural and low-income urban areas. Until it is available to all, then, technology based on Internet access will increase options for those with better resources and leave those without such resources further behind. Moreover, some of these apps cost money, while others are free to use yet may sell the user’s data to support targeted advertising. Accordingly, AARP has produced a review article assessing several apps that offer users an array of choices (Saltzman, 2019).

A related issue is the widespread use of electronic medical records, which in the past decade has changed virtually every aspect of health care, including caregiving. Caregivers may now access the health information of persons living with dementia as their surrogate decision makers, but the ease and degree of this access vary by institution and system (Wolff et al., 2018), and appropriate protections for access to and use of this information may remain unclear to both providers and families, so this is an area that merits further study.

Technology may offer other valuable ways to ease the family caregiver’s stress. For example, a caregiver whose loved one does not require constant supervision can use cameras to monitor for falls, departure from home at unsafe hours, difficulty preparing or consuming food, or other risks. Nonetheless, these devices must be placed strategically to gather appropriate information while minimizing unwarranted intrusions on privacy. For instance, bathroom falls are extremely common among people living with

dementia, but monitoring safety in this context without unduly intruding on privacy is challenging. Accordingly, many prefer to place a bathroom camera so that it monitors only the floor, thus balancing privacy and safety concerns. More research also is needed on such new technologies as voice-activated devices (e.g., Amazon Echo and its artificial intelligence program Alexa) to identify and validate how they can be used to support individuals with dementia and their caregivers. Box 4-3 describes one family’s experience using technology to provide additional oversight of a family member at risk.

New technology is also being applied to old devices. Toileting is a significant challenge for family caregivers, in part because of taboos about this intimate physical activity, and in part because a smaller caregiver may be physically unable, even if willing, to safely help a larger person with such activities as toileting and bathing. Difficulties related to toileting

increase the likelihood of a transition out of the home and into a skilled nursing facility. For these reasons, some now consider the use of bidets and toilet-bidets that can handle both elimination and hygiene. Although somewhat expensive, these devices, commonly used in Asia, can be cost-effective if they delay nursing home placement for a reasonable period. Research on their use for people with dementia has been quite limited, however (Cohen-Mansfield and Biddison, 2005).

Yet while some activities are more easily accomplished with such technological assistance, others remain better suited to a person-to-person approach. Even as the use of technology to support people living with dementia is increasing, some worry that its use may create other risks, such as by reducing human touch—an important component of providing care for which technology cannot substitute (Prescott and Robillard, 2020). Human connection is crucial for both the care recipient and the caregiver, uniquely eliciting emotion and connection between them (see, e.g., Vernon et al., 2019; Fauth et al., 2012). There is also concern that technology will replace family and professional care, perhaps eventually displacing those with the skills required to support people living with dementia. Given the anticipated decrease in the numbers of both family and paid caregivers, however, the loss of jobs is less likely than a shortage of those who can fill them.

Approaches for Addressing Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are common: 97 percent of people with dementia have at least one such symptom (Scales et al., 2018; see also Chapter 3). These symptoms are challenging for individuals living with dementia and their caregivers, and are a frequent reason for transferring a loved one with dementia from home to an institutional setting or from one institution to another. Individuals with persistent symptoms may experience multiple disruptive transitions because of the challenges they can present to caregivers and the limited availability of effective and safe treatments. Such symptoms are sometimes treated with antipsychotic medications that increase patients’ risks of negative outcomes, including falls, cardiovascular events, and death (Kristensen et al., 2018). These and other pharmacological treatments are intended for use only after safer measures have failed, but are still used frequently. It is critical to train family caregivers in how to use safer measures, including gently redirecting their loved ones and limiting or delaying bathing and other stressful activities. Other nonpharmacologic approaches include changes to the environment; sensory treatments, such as massage and aromatherapy; psychosocial treatments, such as reminiscence and music therapy; and

protocols for intimate care, such as bathing. However, the evidence base for such approaches is currently limited, ranging from modest (validation therapy) to moderate (music therapy, exercise) (Scales et al., 2018). (See also Chapter 3.)

RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

There is evidence that many interventions to support family caregivers can provide benefit, but there are also important gaps in the existing research. Overall, the consensus from recent scholarly reviews is that interventions to support caregivers show promise, but much work is needed to advance the necessary implementation science so that effective, large-scale interventions can be available more widely. A significant portion of the available studies lack the methodological rigor that would support wide dissemination. There are also important aspects of the caregiving experience and its effects on both caregivers and people living with dementia that have not yet been documented and studied. Caregivers are exceptionally diverse—by race and ethnicity, income, education, gender, sexual orientation, and geography—yet the current research does not reflect this diversity. There is growing recognition that, to know whether they are asking the right questions and developing the right interventions, researchers will need to intensify their efforts to recruit diverse study participants (Dilworth-Anderson et al., 2020). There is a need for improved ways of collecting data about family caregiving and for conducting well-designed research studies of high-priority questions. The committee identified high-priority research needs in four areas related to family caregiving, summarized in Conclusion 4-1; Table 4-2 lists detailed research needs in each of these areas.

CONCLUSION 4-1: Research in the following four areas has the potential to substantially improve the experience of family caregivers:

- Identification of the highest-priority needs for resources and support for family caregivers, particularly assessment of how caregivers’ needs vary across race and ethnicity, and community.

- Means of identifying the assets that family caregivers bring to their work, as well as their needs for supplemental skills and training and other resources to enhance their capacity to provide care while maintaining the safety and well-being of both the recipients of their care and themselves.

- Continued development and evaluation of innovations to support and enhance family caregiving and address the practical and logistical challenges involved.

- Continued progress in data collection and research methods.

TABLE 4-2 Detailed Research Needs

| 1: Meeting Highest-Priority Needs |

|

| 2: Caregiver Screening and Assessment |

|

| 3: Intervention Development and Evaluation |

|

| 4: Data Collection and Research Methods |

|

REFERENCES

Alzheimer’s Association. (2019). 2019 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures-2019-r.pdf

———. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Dementia: Tips for Public Health Community. https://www.alz.org/professionals/public-health/coronavirus-(covid-19)-and-dementia-tips-for-publ

American Seniors Housing Association. (2021, February 9). 16 Caregiver Apps You Should Use in 2020. https://www.whereyoulivematters.org/best-caregiver-apps

Beach, S.R., and Schulz, R. (2017). Family caregiver factors associated with unmet needs for care of older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(3), 560–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14547

Boltz, M., Chippendale, T., Resnick, B., and Galvin, J.E. (2015). Anxiety in family caregivers of hospitalized persons with dementia: Contributing factors and responses. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 29, 236–241. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0000000000000072

Bookman, A., and Harrington, M. (2006). Family caregivers: A shadow workforce in the geriatric health care system? Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 32(6), 1005–1041.

Burgdorf, J.G., Arbaje, A.I., and Wolff, J.L. (2020). Training needs among family caregivers assisting during home health, as identified by home health clinicians. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(12), 1914–1919.

Callahan, C.M., Arling, G., Tu, W., Rosenman, M.B., Counsell, S.R., Stump, T.E., and Hendrie, H.C. (2012). Transitions in care for older adults with and without dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(5), 813–820. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03905.x

Carpentier, N., Bernard, P., Gernier, A., and Guberman, N. (2010). Using the life course perspective to study the entry into the illness trajectory: The perspective of caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Social Science and Medicine, 70(10), 1501–1508.

Cavaye, J.E. (2008). From Dawn to Dusk: A Temporal Model of Caregiving: Adult Carers of Frail Parents. Paper presented at CRFR Conference, Understanding Families and Relationships over Time, October 28, 2008, University of Edinburg. https://oro.open.ac.uk/27974/1/CRFR%20Conf%20Paper%20October%2008%20Final.pdf

Cohen-Mansfield, J., and Biddison, J. (2005). The potential of wash-and-dry toilets to improve the toileting experience of nursing home residents. Gerontologist, 45(5), 694–699.

Conte, K.P., Schure, M.B., and Goins, R.T. (2015). Correlates of social support in older American Indians: The Native Elder Care Study. Aging & Mental Health, 19(9), 835–843. https://doi.org10.1080/13607863.2014.967171

D’Cruz, M., and Banerjee, D. (2020). Caring for persons living with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic: Advocacy perspectives from India. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 603231. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.603231

DePasquale, N., Davis, K.D., Zarit, S.H., Moen, P., Hammer, L.B., and Almeida, D.M. (2016). Combining formal and informal caregiving roles: The psychosocial implications of double- and triple-duty care. Journals of Gerontology, Series B, 71(2), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu139

Dilworth-Anderson, P., Moon, H., and Aranda, M.P. (2020). Dementia caregiving research: Expanding and reframing the lens of diversity, inclusivity, and intersectionality. Gerontologist, 60(5), 797–805. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa050

Fabius, C., Wolff, J., and Kasper, J. (2020). Race differences in characteristics and experiences of black and white caregivers of older Americans. Gerontologist, 60(7), 1244–1253.

Family Caregiver Alliance. (2019). Caregiver Statistics: Demographics. https://www.caregiver.org/resource/caregiver-statistics-demographics

Fauth, E., Hess, K., Piercy, K., Norton, M., Corcoran, C., Rabins, P., Lyketsos, C., and Tschanz, J. (2012). Caregivers’ relationship closeness with the person with dementia predicts both positive and negative outcomes for caregivers’ physical health and psychological well-being. Aging & Mental Health, 16(6), 699–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2012.678482

Frederiksen-Goldsen, K., and Hooyman, N.R. (2008). Caregiving research, services, and policies in historically marginalized communities: Where do we go from here? Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 18(3–4), 129–145.

Freedman, V.A., and Spillman, B.C. (2014). Disability and care needs among older Americans. Milbank Quarterly, 92(3), 509–541.

Friedman, E.M., Shih, R.A., Langa, K.M., and Hurd, M.D. (2015). U.S. prevalence and predictors of informal caregiving for dementia. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 34(10), 1637–1641. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0510

Gaugler, J.E., Reese, M., and Mittelman, M. (2015). Effects of the Minnesota adaptation of the NYU Caregiver Intervention on depressive symptoms and quality of life for adult child caregivers of persons with dementia. American Journal Geriatric Psychiatry, 23, 1179–1192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2015.06.007

Gaugler, J., Jutkowitz, E., and Gitlin, L.N. (2020). Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Persons Living with Alzheimer’s Disease: Decadal Review and Recommendations. Paper prepared for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Decadal Survey of Behavioral and Social Science Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/07-08-2020/meeting-3-decadal-survey-of-behavioral-and-social-science-research-on-alzheimers-disease-and-alzheimers-disease-related-dementias-and-workshop-4

Gitlin, L., and Hodgson, N. (2018). Better Living with Dementia (1st Edition). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2016-0-01912-5

Gitlin, L., and Wolff, J. (2012). Family involvement in care transitions of older adults: What do we know and where do we go from here? Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 31(1), 31–64.

Gitlin, L., Jutkowitz, E., and Gaugler, J.E. (2020). Dementia Caregiver Intervention Research Now and into the Future: Review and Recommendations. Paper prepared for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Decadal Survey of Behavioral and Social Science Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/10-17-2019/meeting-2-decadal-survey-of-behavioral-and-social-science-research-on-alzheimers-disease-and-alzheimers-disease-related-dementias

Goins, R.T., Spencer, S.M., McGuire, L.C., Goldberg, J., Wen, Y., and Henderson, J.A. (2011). Adult caregiving among American Indians: The role of cultural factors. Gerontologist, 51(3), 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnq101

Greenberg, N.E., Wallick, A., and Brown, L.M. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions on community-dwelling caregivers and persons with dementia. Psychological Trauma, 12(S1), S220–S221.

Häikiö, K., Sagbakken, M., and Rugkåsa, J. (2019). Dementia and patient safety in the community: A qualitative study of family carers’ protective practices and implications for services. BMC Health Services Research, 19, 635. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6728989

Hepburn, K.W., Tornatore, J., Center, B., and Ostwald, S.W. (2001). Dementia family caregiver training: Affecting beliefs about caregiving and caregiver outcomes. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 49(4), 450–457.

Huling Hummel, C., Pagan, J.R., Israelite, M., Patterson, E., Van Buren, B., and Woolfolk G. (2020). A Summary of Commentaries Submitted by Those Living with Dementia and Care Partners. Paper prepared for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Committee on Decadal Survey of Behavioral and Social Science Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias. https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/decadal-survey-of-behavioral-and-socialscience-research-on-alzheimers-disease-and-alzheimers-disease-related-dementias#sl-threecolumns-b93dcbe8-e082-4170-9bfc-a8cae8ef0445

Johnson, R. (2019). What is the Lifetime Risk of Needing and Receiving Long-Term Services and Supports? Washington, DC: Urban Institute and Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/what-lifetime-risk-needing-and-receiving-long-term-services-and-supports

Jutkowitz, E., Kane, R.L., Gaugler, J.E., MacLehose, R.F., Dowd, B., and Kuntz, K.M. (2017). Societal and family lifetime cost of dementia: Implications for policy. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(10), 2169–2175. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15043

Kasper, J., Freedman, V., and Spillman, B. (2014). Disability and Care Needs of Older Americans by Dementia Status: An Analysis of the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://aspe.hhs.gov/report/disability-and-care-needs-olderamericans-dementia-status-analysis-2011-national-healthand-aging-trends-study

Kasper, J., Freedman, V., Spillman, B., and Wolff, J. (2015). The disproportionate impact of dementia on family and unpaid caregiving to older adults. Health Affairs, 34(10), 1642–1649.

Kristensen, R., Norgaard, A., Jensen-Dahm, C., Gasse, C., Wimberley, T., and Waldemar, G. (2018). Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication in people with dementia. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 63(1), 383–394.

Mittelman, M.S., Haley, W.E., Clay, O.J., and Roth, D.L. (2006). Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology, 67(9), 1592–1599. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000242727.81172.91

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). (2016). Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/23606

———. (2018). Considerations for the Design of a Systematic Review of Care Interventions for Individuals with Dementia and Their Caregivers: Letter Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25326

———. (2021). Meeting the Challenge of Caring for Persons Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners and Caregivers: A Way Forward. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26026

National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2020). Caregiving in the United States, 2020: The “Typical” African American Caregiver. Washington, DC. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/AARP1316_CGProfile_AfricanAmerican_May7v8.pdf

National Institute on Aging. (2020). Dementia Care Summit Gaps and Opportunities. https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/summit-gaps-opportunities

Ornstein, K., Wolff, J., Bollen-Lund, E., Rahman, O-K., and Kelley, A. (2019). Spousal caregivers are caregiving alone in the last years of life. Health Affairs, 36(6). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00087

Ortman, J.M., Velkoff, V.A., and Hogan, H. (2014). An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf

O’Shaughnessy, C. (2014). National Spending for Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS), 2012. National Health Policy Forum, Paper 284. https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/sphhs_centers_nhpf/284

Parker, D., Mills, S., and Abbey, J. (2008). Effectiveness of interventions that assist caregivers to support people with dementia living in the community: A systematic review. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 6(2), 137–172.

Peacock, S., Hammond-Collins, K., and Forbes, D.A. (2014). The journey with dementia from the perspective of bereaved caregivers: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Nursing, 13(1), 42–52.

Penrod, J., Hupcey, J.E., Baney, B.L., and Loeb, S.J. (2011). End-of-life caregiving trajectories. Clinical Nursing Research, 20(1), 7–24.

Peterson, K., Hahn, H., Lee, A.J., Madison, C., and Atri, A. (2016). In the Information Age, do dementia caregivers get the information they need? Semi-structured interviews to determine informal caregivers’ education needs, barriers, and preferences. BMC Geriatrics, 16, 164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0338-7

Pinquart, M., and Sörensen, S. (2003). Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: A meta-analysis. Journals of Gerontology Series B, 58(2), 112–128.

———. (2005). Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: A meta-analysis. Gerontologist, 45(1), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/45.1.90

Prescott, T., and Robillard, J. (2020). Are friends electric? The benefits and risks of human-robot relationships. iScience, 24(1), 101993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101993

Redfoot, D., Feinberg, L., and Houser, A. (2013). The aging of the baby boom and the growing care gap: A look at future declines in the availability of family caregivers. http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/ltc/2013/baby-boom-and-the-growing-care-gap-insight-AARP-ppi-ltc.pdf

Saltzman, M. (2019). These Apps for Caregivers Can Help You Get Organized, Find Support. AARP. https://www.aarp.org/home-family/personal-technology/info-2019/top-caregiving-apps.html

Scales, K., Zimmerman, S., and Miller, S. (2018). Evidence-based nonpharmacological practices to address behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Gerontologist, 58(S1), S88–S102.

Schulz, R., McGinnis, K., Zhang, S., Martire, L., Hebert, R., Beach, S., Zdaniuk, B., Czaja, S., and Belle, S. (2008). Dementia patient suffering and caregiver depression. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 22(2), 170–176. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0b013e31816653cc

Schulz, R., Beach, S.R., and Friedman, E.M. (2021). Caregiving factors as predictors of care recipient mortality. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(3), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.06.025

Schure, M.B., Conte, K.P., and Goins, R.T. (2015). Unmet assistance need among older American Indians: The Native Elder Care Study. Gerontologist, 55(6), 920–928. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt211

Shankar, K.N., Hirschman, K.B., Hanlon, A.L., and Naylor, M.D. (2014). Burden in caregivers of cognitively impaired elderly adults at time of hospitalization: A cross-sectional analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62, 276–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12657

Sharma, N., Chakrabati, S., and Grover, S. (2017). Gender differences in caregiving among family-caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World Journal of Psychiatry, 6(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.7

Sörensen, S., Duberstein, P., Gill, D., and Pinquart, M. (2006). Dementia care: Mental health effects, intervention strategies, and clinical implications. Lancet Neurology, 5(11), 961–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70599-3

Sousa, L., Sequeira, C., Ferré-Grau, C., Neves, P., and Lleixà-Fortuño, M. (2016). Training programmes for family caregivers of people with dementia living at home: Integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(19–20), 2757–2767.

Spencer, S.M., Goins, R.T., Henderson, J.A., Wen, Y., and Goldberg, J. (2013). Influence of caregiving on health-related quality of life among American Indians. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(9), 1615–1620. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12409

Spillman, B.C., and Long, S.K. (2007). Does High Caregiver Stress Lead to Nursing Home Entry? Washington, DC: Urban Institute and Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/does-high-caregiver-stress-lead-nursing-home-entry

Spillman, B., Wolff, J., Freedman, V.A., and Kasper, J.D. (2014). Informal Caregiving for Older Americans: An Analysis of the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/informal-caregiving-older-americans-analysis-2011-national-study-caregiving

Toth, M., Martin Palmer, L., Bercaw, L., Johnson, R., Jones, J., Love, R., Voltmer, H., and Karon, S. (2020). Understanding the Characteristics of Older Adults in Different Residential Settings: Data Sources and Trends. Washington, DC: RTI International and Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/understanding-characteristics-older-adults-different-residential-settingsdata-sources-and-trends

Vernon, E.K., Cooley, B., Rozum, W., Rattinger, G.B., Behrens, S., Matyi, J., Fauth, E., Lyketsos, C.G., and Tschanz, J.T. (2019). Caregiver-care recipient relationship closeness is associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(4), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2018.11.010

Whitlatch, C.J., and Orsulic-Jeras, S. (2018). Meeting the informational, educational, and psychosocial support needs of persons living with dementia and their family caregivers. Gerontologist, 58(1), S58–S73. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx162

Wolff, J.L., Kim, V.S., Mintz, S., Stametz, R., and Griffin, J.M. (2018). An environmental scan of shared access to patient portals. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 25(4), 408–412. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocx088

World Health Organization. (2017). Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259615/9789241513487-eng.pdf;jsessionid=1FCE8E87E676952FDE11910F8851B120?sequence=1