6

Health Care, Long-Term Care, and End-of-Life Care

People living with dementia are most often diagnosed and treated by a primary care physician, but many are also treated by numerous other medical specialists, for both dementia and other conditions, as their diseases progress. They also are likely to interact with many different institutions that provide health care and social support as their dementia symptoms become more severe and they lose their ability to function independently. And many of those who become totally dependent upon others will spend time living in long-term care facilities and ultimately receive such care as hospice at the end of life.

Thus, people living with dementia have relationships with numerous professionals and institutions—often a great many, over time—including primary care providers; neurologists, psychiatrists, geriatricians, and nurse practitioners who specialize in dementia care; social workers; and public and private entities that provide residential and end-of-life care. Each interaction may be comforting and beneficial, or may fall short of that ideal. These interactions are shaped by the characteristics of the institutions that provide care, which are often large and complex, and the systems of which they are a part. These systems, in turn, are shaped by the policy environment and other contextual factors discussed in Chapter 1. Earlier chapters have also explained how differences in the quality and availability of all types of care and the way these services are funded have significant impacts on individuals and families. This chapter examines the functioning of the systems that provide health care, long-term care, and end-of-life care for people living with dementia, including how well they support those people and their families, as well as how they are funded.

The committee’s aim for this chapter was to provide an overview of key issues for these fundamental supports for people living with dementia, but we were unable to address every issue of importance in detail. We note that the experiences individuals have with the institutions that provide these supports vary enormously depending on where they live, as well as their financial circumstances, level of educational attainment, access to care, assumptions about need, help-seeking behavior, and other factors: there is no “average” experience. Therefore, we focused on care delivery models that have been evaluated and described in the research literature, and looked for opportunities to improve care.

THE HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

People living with dementia need care for the disease that causes it, which is typically offered by a primary care provider. They also require routine health care, and individuals in this predominantly older population frequently have other serious medical conditions. Managing this care is a challenge for people living with dementia and their family caregivers. Questions about the quality of dementia care provided by nonspecialists and how patients fare when they have other significant medical conditions are key to reducing negative impacts. This section looks first at what is known about the quality of primary care and then at approaches to coordinating care.

Quality of Primary Care

Primary care providers, such as physicians and advanced practice providers (nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and clinical nurse specialists), provide first-line care for people with dementia. These practitioners often have long-term relationships with their patients, which can be an advantage for identifying and managing dementia. However, the training received by primary care physicians in internal and family medicine provides limited opportunities to learn about managing care for people living with dementia in an ambulatory care setting, although some may have had experience with patients in the later stages of dementia through working in nursing home settings. A lack of training and experience in caring for people with dementia can mean missed or delayed diagnosis and less-than-optimal management of care. A recent survey of primary care physicians showed that many feel they lack knowledge and confidence in their skills in this area, are uncertain about how to diagnose dementia, and find the condition challenging to manage (Lee et al., 2020). By one estimate, of the 730,026 physicians practicing in the United Sates in 2019, 228,936, or 31 percent, were primary care physicians (Willis et al., 2020), and in 2020, only 6,896 primary care physicians were geriatricians with specific training

in providing care for patients with dementia (American Board of Medical Specialties, 2020).

There are guidelines for the care that people living with dementia should receive, such as the quality indicators shown in Box 6-1. However, related research indicates that many patients do not receive optimal care and that few of these indicators of quality are routinely met. By one estimate based on a series of observational studies, adherence to current standards averaged 44 percent across all dementia quality indicators (Jennings et al., 2016).

Unfortunately, little research is available to guide further development of policies and best practices related to the provision of primary care to persons living with dementia. For example, one might expect that a

multispecialty practice would be better able to manage the complex needs of persons with dementia, either because some primary care physicians could specialize in managing such patients or because centralized care management resources could be available to the entire practice. However, there is as yet no evidence pointing to specific ways to improve the quality and consistency of the dementia care provided by primary care practitioners in settings that do not include specific dementia care programs.

Fragmentation of Care Delivery

From the perspective of patients and families, what is most important is that they are aware of, understand, and are able to easily access the care and services they need. The current care delivery system offers little guidance to older adults, including those with dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and their families, in navigating and managing health care and long-term care systems. In practice, needs for care include medical issues, such as management of other conditions and coordination of prescriptions, as well as help with daily living, such as preventing falls, ensuring that prescriptions are taken correctly, and managing incontinence. Individuals living with dementia experience more frequent hospitalizations and longer stays relative to their peers without dementia, and these hospitalizations are a prime contributor both to high medical costs for this population and to morbidity (Lin, 2020).

The challenges of managing multiple conditions are exacerbated by cognitive impairment. Each progressive, chronic condition an individual develops may involve an additional specialist or clinic for a patient who is likely to be challenged by the need to manage that added complexity. While care coordination is very important for all older patients with complex chronic conditions, it is especially important for those living with dementia and their caregivers, who must navigate the complex transitions between care settings and health care providers. Many such care providers have limited experience with the needs of people with impaired cognition. There is evidence, for example, that dementia patients with other medical issues receive less consistent treatment and monitoring for such conditions as visual impairment and diabetes relative to those with similar conditions who do not have dementia (Bunn et al., 2014).

Comprehensive Dementia Care

Increasingly, health care delivery systems are responding both to the needs of their patients and to a movement for incentive-based changes in health care financing by exploring comprehensive approaches to providing care. For example, a program developed at the University of California,

Los Angeles, the UCLA Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care Program, was designed to coordinate the care provided by diverse practitioners, with the goal of maximizing patients’ functioning, independence, and dignity and decreasing strain on caregivers (Reuben et al., 2013). Another example is the Integrated Memory Care Clinic, a medical home designed to coordinate the care provided by geriatric nurses, social workers, and various medical specialists (Clevenger et al., 2018). Other models include home visits and telephone management by nonlicensed or licensed providers supported by clinical professionals (Haggerty et al., 2020). Programs designed to provide comprehensive care include such elements as

- continuous monitoring and assessment,

- development of a care plan,

- psychosocial interventions,

- providing the patient with self-management tools,

- caregiver support,

- medication management,

- treatment of related conditions, and

- coordination of care (Boustani et al., 2019).

Studies of such programs suggest benefits that include improvements in behavioral and emotional symptoms and reductions or delay in the need for admission to a long-term care facility (Reuben et al., 2019b; Jennings et al., 2019, 2020; see also Haggerty et al., 2020). A study of Medicare fee-for-service claims suggests that people with dementia who had access to some plan for ensuring continuity of care had lower rates of hospital admission and fewer emergency room visits relative to those who had less continuity of care (Amjad et al., 2016).

Although the committee that produced a recent National Academies’ report recommended disseminating collaborative care models that use multidisciplinary teams, care of this kind is not yet readily available in most communities (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2021). Dissemination has stalled at least in part because these models are not financially viable under current reimbursement structures. Some comparative effectiveness research to test such comprehensive approaches is under way, but additional pragmatic trials and assessment of the impacts of reimbursement structure and other issues, will be important extensions of existing research.

A Model of Comprehensive Care at the Population Level

Researchers have explored ways to bring the benefits of evidence-based dementia care to larger populations. One proposed model is for health

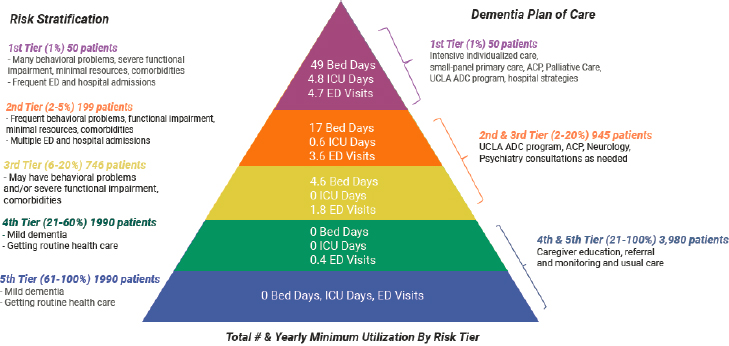

systems to design dementia care from a population perspective by planning for the types and intensity of medical and support services likely to be needed by different segments of the dementia population they serve (Reuben et al., 2019a). This model allows a health system to use estimates of the number of people it serves who currently have dementia, combined with assessments of the patient needs typical at different phases of the disease, to project the types of services likely to be needed. Figure 6-1 shows a model of the stages experienced by persons living with dementia (five stages identified in the tiers of the pyramid) and the severity of the symptoms associated with each (on the left side of the pyramid) (Reuben et al., 2019a). It identifies how many persons (among the 5,000 in the example) are likely to be at each stage at a given time and indicates the likely needs of individuals for health care system resources at each tier (on the right side of the pyramid). The information in the tiers indicates the intensity and resources associated with each stage of disease progression.

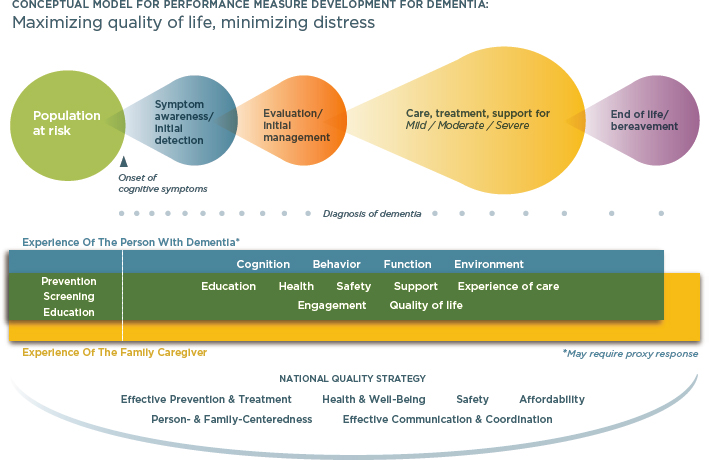

Figure 6-2 shows in more detail the issues at play in caring for individuals who progress through the stages of disease.

A comprehensive dementia care approach such as this may benefit patients and families, and also yield cost savings for both patients and the health care system. For example, this type of analysis could support improved planning to strengthen the resources in the home (allowing individuals to live at home longer), coordinate medical care, establish and maintain links to community resources, and provide support to caregivers—thus helping to delay the phase when patients need the highest levels of care (Jennings et al., 2019). For those with behavioral symptoms, behavioral health

SOURCE: Reuben et al. (2019a). Reprinted with permission from Project Hope/Health Affairs Journal.

SOURCE: National Quality Forum (2014). Reprinted with permission.

care providers may be helpful in reducing admissions to psychiatric units and long-term nursing home placement. We note that integrating mental health care with care for dementia symptoms and with the care provided in residential facilities is a challenge, as it is in other parts of the health care system, though a detailed exploration of these issues was beyond the scope of this report.

The potential benefits of a population-based approach can be considerable. For patients who enter the top tier shown in Figure 6-1, the costs of institutional care are extraordinarily high, and the benefits of such expenditures in terms of the duration or quality of life are uncertain. People at this stage frequently have patterns of recurrent or prolonged hospitalization, most often for infectious diseases or behavioral complications of dementia (e.g., agitation, aggression). Those admitted to a psychiatry unit because of behavioral problems often have prolonged stays (some more than 40 days) because it is usually very difficult to find nursing or assisted living facilities that will accept these patients (for reasons that include staff time needed and potential liability resulting from patient or staff injuries). Some patients require a legally authorized guardian (conservatorship) to make discharge decisions, and the legal system for establishing this arrangement is often slow. Palliative care or hospice (discussed below) is not a substitute for permanent nursing home placement, although among those with very advanced dementia, it can help prevent repeated hospital transfers that are distressing for the patient and result in little or no benefit.

Knowledge Gaps

The disease and health care needs model discussed above offers a valuable heuristic for assessing the progression of dementia and associated needs. However, population-based management of the disease trajectory of people living with dementia is realistic only in an integrated health system that cares for enough dementia patients to justify creating such programs. Many people living with dementia do not receive care in a health system but rely on a primary care physician who serves a wide array of patients, relatively few of whom have dementia. It is difficult for small or solo practices to provide the expertise and access to programs needed by dementia patients. In one study of dementia diagnoses and health care over the 5-year period following diagnosis, 85 percent of Medicare beneficiaries were diagnosed by a primary care or an internal medicine physician or other nondementia specialist physician. Five years later, only about one-third had received any care by a dementia specialist (Drabo et al., 2019). Among older fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with a dementia diagnosis, lower continuity of care is associated with higher rates of hospitalization, emergency department visits, testing, and health care spending (Amjad et al., 2016). It is not known what proportion of providers are embedded in an integrated delivery system, but it is reasonable to assume that access to such delivery systems varies by urban or rural location and by the patient’s race, ethnicity, income, and education.

Additional information is needed to support widespread adoption of comprehensive care models. One challenge is the considerable variation in the clinical progression of the disease and the associated variability in the range and timing of health care utilization. To date, few empirical, population-based studies have systematically documented individuals’ progression through the phases of dementia and the care needs and health care costs associated with a dementia diagnosis. One study that focused on Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries used indicators of patients’ use of services (e.g., diagnosis date, initial postacute care, nursing home placement) as a measure (Bentkover et al., 2012). However, this approach captured data only for individuals who use services that incur charges, excluding data for care provided by, for example, family members. Better empirical estimates of the rate of progression through the natural phases of the disease would be extremely helpful to the field in general but also to the many health care systems trying to plan for the needs of this population.

A second issue is that although a number of care models have been implemented and studied (e.g., Possin et al., 2019; Callahan et al., 2006), few of these studies have been replicated. Such studies have established that model programs can be efficacious under optimal conditions. However, more embedded pragmatic clinical trials are needed to identify how such models can be implemented in real-world circumstances. Some work

is under way to pursue this goal. The National Institute on Aging has recently made a considerable investment in testing pilot projects that, once completed, can be launched as pragmatic clinical trials embedded in fully functioning health care systems. The IMbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and AD-Related Dementias (AD/ADRD) Clinical Trials (IMPACT) Collaboratory was established to solicit pilot applications of promising interventions for which there is evidence of efficacy and then to fund, support, and monitor them as part of an effort to build the evidence base for embedded pragmatic trials focused on improving care for persons living with dementia and their caregivers (Mitchell et al., 2020).

LONG-TERM AND END-OF-LIFE CARE

There are several ways to meet the needs of patients and families in the later stages of dementia, when they require more comprehensive daily support. While it is common for people entering the terminal stage of dementia to be admitted to a nursing home or the memory care unit of an assisted living facility, the duration of such placements varies considerably, and many of these individuals are cared for at home.

State policies and regulations have a significant impact on residential care such as assisted living and memory care. Aside from an infrequently used accreditation program, there are no national definitions, standards, enforcement mechanisms, financing programs, or regulations for these residential settings, although they serve nearly 1 million people across the states; 41.9 percent of individuals in residential care and 47.8 percent of nursing home residents (2016 data) are diagnosed with dementia (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2019).1 Thus, it falls to states to regulate the safety of and care provided in these facilities. States also set Medicaid reimbursement rates for various services, including nursing home care, home care, and case management, and states have some flexibility with Medicaid eligibility. Reimbursement methods differ across states, and reimbursement rates vary substantially. State legislatures may also pursue unique policy goals. For instance, in 2019 Washington State became the first state to establish an entitlement to funding for long-term services and supports by enacting the Washington State Long-Term Care Trust Act, recognizing the impact of dementia and other functional impairments that lead to a need for paid help (Gleckman, 2019).

Options for providing the necessary care and support for patients in their own homes have been expanding, but payment for long-term care, which is extremely expensive, remains a challenge. This section considers issues associated with assisted living and memory units, nursing homes, alternatives to nursing homes, and palliative and hospice care.

___________________

1 These data include only facilities that are regulated by states or the federal government.

Assisted Living and Memory Units

Assisted living and memory care or dementia units serve a small but significant percentage of dementia patients. The number of specialty care memory units, including those housed within a larger care system (e.g., part of an assisted living setting), has increased recently, from approximately 63,000 in 2013 to 98,000 in 2018 (Adler, 2018). Unlike nursing homes, which rely heavily on Medicaid financing, assisted living facilities are usually paid for privately, generally out of pocket, but occasionally through long-term care insurance.2 These units often feature modified environments (e.g., exit controls, safety accommodations, and other designs that promote security and safety); offer dementia-related services, such as medication management; and have staff who have completed training in dementia. Such targeted dementia care has been associated with outcomes that include reduced rates of depression, improved medication adherence, and decreased emergency room use (Zimmerman et al., 2005). However, relatively little is known about the attributes of and regulatory requirements for this type of care that affect outcomes and quality of life for people with dementia, or the delivery, structure, quality, and financing of these facilities.

Nursing Homes

Dementia is the most common clinical diagnosis among persons residing in the approximately 15,600 nursing homes in the United States. Just under 70 percent of nursing homes are privately owned for-profit entities (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2019). Nursing homes serve two populations:

- long-stay patients, for whom costs are often paid by Medicaid, predominantly at or below the actual cost of providing care; and

- postacute residents, for whom fees are paid by Medicare or commercial insurers at a higher reimbursement rate generally exceeding care costs.

Postacute residents, who account for more than 90 percent of admissions to most nursing homes, come from hospitals to receive skilled, rehabilitative care following an acute care hospital episode, with the goal of being discharged to the community (Rahman et al., 2014; Tyler et al., 2013). Although the majority of nursing homes provide both long-stay and postacute care, many have sought to specialize in the latter, marketing their facilities to hospitals and Medicare Advantage plans to increase admissions

___________________

2 In 2014, 330,000 Medicaid beneficiaries received assisted living services (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2018a, 2018b).

of such patients and competing to build preferred relationships with local hospitals to maintain their referral base (Mor et al., 2016; Rahman et al., 2013). While most postacute nursing home patients return home, persons living with dementia are more likely to “get stuck” and become permanent nursing home residents. A recent study found that those admitted with a secondary diagnosis of dementia were substantially less likely to return home and also remained longer in the nursing home (Bardenheier et al., 2020).

Medicaid is the primary payer for long-stay nursing home care. Thus, it is important to note that the care financed by Medicaid has long been plagued by quality and safety problems, ranging from inadequate staffing to high rates of infection and hospitalization (Institute of Medicine, 1986, 2001; Mor et al., 2004).3 While major regulatory policies, including the Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987 and subsequent revisions, have attempted to address these deficiencies in the quality of care, concerns remain. One is that the current oversight system, implemented by individual states, produces inconsistent outcomes and emphasizes punishment rather than quality improvement (Angelelli et al., 2003). On the other hand, recent efforts to increase the transparency of nursing home quality and tie it directly to payment have also produced only modest quality improvements (Werner et al., 2009, 2012, 2013, 2016).

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the shortcomings of the current system of long-term care. Nursing home residents and staff in the United States were hit particularly hard by the virus, which caused extremely high rates of infection and death in nursing homes and other congregate care settings (35–40% of COVID-19 deaths as of fall 2020 [Soucheray, 2020]; see Chapter 1). Although the primary determinant of an outbreak of COVID-19 is the prevalence of the virus in the adjacent area, most nursing homes lacked the resources necessary to contain an outbreak, including tests and personal protective equipment (Altman, 2020; Gorges and Konetzka, 2020; Chatterjee et al., 2020; White et al., 2020; Abrams et al., 2020; Panagiotou et al., 2021; Ouslander and Grabowski, 2020). Moreover, regulatory requirements were difficult to follow and subject to rapid change. New York State, for instance, at one point imposed stiff fines on nursing homes that refused to admit patients diagnosed with COVID but later rescinded this requirement under public pressure (Sapien and Sexton, 2020). Furthermore, nursing home staff are routinely underpaid and undertrained, and many work multiple jobs, which increased the risk of transmitting the virus across facilities (Chen et al., 2020; Van Houtven et al., 2020). The spread of the virus also was exacerbated by the use of

___________________

3 A forthcoming National Academies’ report will address nursing home quality issues in detail; see https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/the-quality-of-care-in-nursing-homes.

shared living quarters and communal spaces in nursing homes, as well as the intimate nature of the needed care, which makes social distancing or isolation difficult if not impossible.

Alternatives to Nursing Homes

Many Americans would prefer to avoid living in a nursing home, and the continuing quality problems discussed above have given rise to the development of numerous alternative residential settings specifically for dementia care. These alternatives include assisted living communities, independent or retirement communities, and memory care communities, and can encompass both institutional and residential care. Access to and payment for such settings vary, and states have significant discretion over what Medicaid will cover. For example, while Medicaid will not pay for the room and board portion of senior living fees, some states do have waivers that allow Medicaid to cover the portion associated with enriched services (e.g., care coordination, nurse practitioner clinics, meals, and transportation). Most states provide reimbursement for assisted living through Medicaid programs. However, all but a few states have imposed limits on the number of places that are paid by Medicaid, and they have capped daily reimbursement rates at well under the prevailing private pay rates. Lack of long-term care insurance and the limits of Medicaid mean that most people finance their senior living using personal savings, housing equity, or family out-of-pocket contributions. Unfortunately, the ways in which families in different populations finance care and the impact on their financial security have not been well studied.

As researchers and policy makers contemplate the future of long-term care after COVID-19, one intriguing approach is to reimagine the physical layout of nursing homes for long-stay residents. Emerging evidence suggests that smaller facilities serving approximately a dozen individuals and emphasizing a home-like environment, such as those developed by the Green House Project (see Box 6-2), are associated with superior quality of life (Grabowski and Mor, 2020; Werner et al., 2020; Zimmerman et al., 2016). However, current evidence on home-like residential care models is limited (Ausserhofer et al., 2016). In addition, models that involve replacing an existing physical plant or undertaking a comprehensive redesign require substantial capital outlay, and ongoing operating costs could be higher as well. The cost to government in terms of the number of inspectors visiting a large number of small facilities would be an additional consideration in contemplating such a transformation of the residential care system. Evaluation of such projects would provide a foundation for further innovation and the real-world application of these kinds of approaches.

It would also be useful to know more about patterns of use of alternatives to nursing homes. States are increasingly using Medicaid waivers for home and

community-based services to shift care out of nursing homes and into home settings, partly in response to a Supreme Court decision requiring Medicaid to pay for care in the least restrictive settings possible (Olmsted v. L. C., 527 U.S. 581 [1999]4). This shift may be beneficial for individuals. Surveys suggest that people want to live at home for as long as possible (Guo et al., 2014; Brown et al., 2012), and there is some evidence that helping people stay home reduces health care spending (Newcomer et al., 2016). There is also evidence that both fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage members (see below) increased their use of home health care between 2007 and 2010, for example, but that usage subsequently declined primarily because of reimbursement and regulatory changes (Li et al., 2018). Home health care is among the fastest-growing Medicare expenditures: in 2019 it grew faster than all other types of care.5

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on nursing home and alternative care settings are not yet fully understood, but it appears that many families are substituting home care for facility-based rehabilitative and recuperative care (Flynn et al., 2020). Some prior work has demonstrated that patients receiving home health care in place of institutional postacute care in a nursing home have worse outcomes (Werner et al., 2019), but the trade-off for people living with dementia is not known. Sources of risk for patients receiving home care include the complexity of adhering to postacute care instructions from multiple physicians and higher rates

___________________

of rehospitalization (which can cause confusion and delirium in elderly patients, especially those with dementia).

Nursing homes were already one of the least desirable health care settings before the pandemic, but with the high COVID death rates and the accompanying forced isolation of residents, they are even more likely to become care settings of last resort. Research on the implications of greater reliance on home health, including the increased responsibilities assumed by families, as well as how health care systems can better coordinate the care provided by home health agencies with the medical treatment being managed by primary care physicians, is badly needed.

Palliative and Hospice Care

There is evidence that both palliative and hospice care improve the quality of life for people at the end of life, including dementia patients (Evans et al., 2019). Palliative care is designed to address the symptoms of a serious condition and preserve the patient’s comfort and dignity, as opposed to curing the underlying condition, and is an option for any dementia patient.6 It is a way of thinking about the nature of the care a patient chooses, and physicians may specialize in providing this type of care (Mor and Teno, 2016). Although palliative care can be offered along with curative care for patients who may recover or improve (e.g., some cancer patients), it is the term commonly used for cases in which patients have chosen, usually though an advance directive or their family caregiver proxy, to receive only care that alleviates discomfort. This option is particularly valuable to many people living with dementia who do not wish to receive aggressive medical treatments or be in a hospital setting at the end of life, although palliative care may be provided long before the end of life. Palliative care is relatively rarely available in nursing homes or on an outpatient basis. Medicare may cover palliative care costs as it would cover any physician or nurse practitioner visit, depending on the benefits the individual has and the specifics of the treatment plan (National Institute on Aging, 2016).

Hospice care, in the context of Medicare coverage, differs from palliative care primarily in that it is offered only close to the end of life and is for situations in which the attending physician believes the patient is not expected to live more than 6 additional months. Like palliative care, hospice care focuses on the patient’s comfort, and it can be provided in an inpatient hospice facility, in another institution, or in the patient’s home, but there are limits on the length of time patients can receive some hospice care benefits. Regardless of setting, patients receiving hospice care do not

___________________

6 For more information on palliative and hospice care, see https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-are-palliative-care-and-hospice-care.

receive curative treatments (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2021b).

Hospice care has become increasingly common since Medicare began including it as a benefit in 1983, and significant changes to the program were made in 1986, as discussed below. Medicare covers the costs of hospice care even if it is needed for longer than 6 months, as long as the hospice medical director or other hospice doctor recertifies that the patient is terminally ill (CMS, n.d.). While evidence indicates that hospice care improves quality of life, growing numbers of patients receiving the care for longer than 6 months have resulted in increased costs (Miller et al., 2002; Teno et al., 2014).

There are several questions to consider regarding palliative and hospice care for dementia patients. One is whether it would be beneficial to offer either of these services to people living with dementia earlier in their disease progression than is currently typical. Even though several randomized controlled trials suggest that earlier intervention can improve quality of life and perhaps even reduce health care costs, it is not yet clear whether these effects would be replicated in the real world of fee-for-service Medicare, particularly for persons living with dementia whose prognosis is much less well understood than is the care for those with cancer diagnoses (Temel et al., 2010; Mor et al., 2018).

Study of other issues could support improvements in the design of palliative and hospice care programs and policies regarding their use. For example, the length of stay under hospice care prior to dying has been relatively steady over several decades, with some 40 percent of patients experiencing less than 7 days of such care, even though advocates believe that allowing more time would increase the benefit of the care (Teno et al., 2013). Hospice length of stay tends to be longer among those with dementia relative to those with other diagnoses, but the reasons for this are not clear. It would also be useful to know more about how persons living with dementia use palliative and hospice care; the preferences of dementia patients, their caregivers, and providers; the care choices made on patients’ behalf in the last months and weeks of life; and how advance care directives affect the use of these kinds of care.

PAYING FOR CARE: MEDICARE AND MEDICAID

A key factor in the quality of dementia care, the timeliness of dementia detection, and the quality of life for persons living with dementia is how their care is paid for. The federal government has a direct impact on the way health and long-term care services are structured, delivered, and financed through Medicare (the federal health insurance program for people 65 or older and certain younger people with disabilities) and

Medicaid (the federal and state-funded provider of health care coverage to low-income individuals of any age, including those with disabilities).7 Medicare covers 95 percent of all persons with dementia, and approximately one-quarter of adults with dementia also receive Medicaid benefits (Garfield et al., 2015). Medicare is complex, however, and the coverage it offers for dementia care has limitations and gaps. Medicare has also undergone changes in the past few years that have differing implications for those who are enrolled in traditional Medicare (the original version of Medicare), which includes both hospital insurance (Part A) and outpatient medical insurance (Part B) on a fee-for-service basis, with optional Part D prescription insurance, and those enrolled in Medicare Advantage, in which Parts A and B, and usually also Part D prescription insurance, are bundled together; see Box 6-3.8 This section examines two key challenges associated with how aspects of dementia care are covered and the current state of thinking about managed care.

Coverage

Two issues related to dementia-related coverage under Medicare and Medicaid are important to note. The first concerns cognitive assessments. Since 2011, Medicare has covered an annual wellness visit that must include a cognitive assessment, which could promote earlier detection of dementia (see Chapter 3). Although the type of assessment has not been specified, typically it is a brief screening that, if positive, needs to be followed by a more extensive diagnostic evaluation. The annual wellness visit is covered in full by Medicare, but subsequent follow-up evaluations must be billed according to other codes. Implementation of the annual wellness visit in practice has been slow: it is estimated that 5 years after it was instituted,

___________________

7 The health insurance provisions of the Affordable Care Act had limited impact on older individuals because most of them already had coverage through Medicare. However, the law included a number of delivery system reforms that have consequences for those on Medicare and those who are dually eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. Dually eligible individuals account for a disproportionate share of spending in both Medicare and Medicaid. In 2013, 15 percent of Medicaid enrollees were dually eligible, but they accounted for 32 percent of Medicaid spending; 20 percent of Medicare enrollees had dual eligibility, and they accounted for 34 percent of all Medicare spending (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, 2020). Among dually eligible individuals over age 65, 23 percent had a diagnosis of dementia (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission and Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, 2018).

8 For more information about the components of Medicare and the differences among plans, see https://www.medicare.gov/what-medicare-covers/your-medicare-coverage-choices/whats-medicare. Additional information can be found at https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/an-overview-of-medicare/?gclid=CjwKCAjw0On8BRAgEiwAincsHE3No4tHUSNvqb--BjbFQzoZHX93wQURevpzFM4_jRuh3F-M7hihCRoCWH8QAvD_BwE.

only one-quarter of eligible beneficiaries had received this cognitive assessment (Ganguli et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2015). Data about annual wellness visits and cognitive assessments are limited, but another study, based on a nationally representative sample of older Americans, showed that in 2019, only 30 percent had undergone a cognitive assessment in the primary care setting; rates were higher among persons enrolled in Medicare Advantage compared with those enrolled in traditional Medicare (Jacobson et al., 2020). The research also revealed that detection of cognitive impairment was no more common among those who had had annual wellness visits than among those who had not had such visits (see also Fowler et al., 2018). Results of one study suggest that up to two-thirds of those identified through screening as having cognitive impairment do not undergo a subsequent diagnostic assessment (Fowler et al., 2015). In 2021, CMS increased payment levels for these follow-up diagnostic assessments and care plan services, but it is not yet clear whether this payment increase will result in improved follow-up care (CMS, 2021a).

The other issue is that Medicare does not cover two classes of services that are critical for dementia patients: institutional long-term nursing home care and certain home and community-based services. After spending down their savings and existing financial resources, about 30 percent of persons with dementia are also covered by Medicaid, which covers some long-term services and supports not included in Medicare’s benefit package (Mor et al., 2010). However, persons living with dementia who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid face fragmented financing, and the conflicting incentives for the two programs can lead to potentially unnecessary and intensive care. For instance, Medicaid typically pays nursing homes a daily

custodial rate that covers room, board, and nursing care. When a resident becomes acutely ill, the nursing home has an incentive to transfer the patient to a hospital, thereby shifting the costs to the Medicare program, even though such a transfer may not be in the patient’s interest (Unruh et al., 2013). The nursing home can also earn a higher per-day rate for providing Medicare-financed skilled nursing home care when the same patient returns to the nursing home after discharge. These incentives can lead to a “revolving door” between nursing homes and hospitals, with adverse consequences for cognitively impaired and frail elderly people (Mor et al., 2010; Goldfeld et al., 2013; Polniaszek et al., 2011).

The Federal Role in Innovation

CMS has taken significant steps to document, measure, and address fragmentation in the health and long-term care systems. Starting in the 1990s, CMS provided the first waivers for the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly, a program that provides comprehensive medical and social services to adults over age 55 who are dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid and are sufficiently frail to be categorized as “nursing home eligible” by their state’s Medicaid program. The CMS Innovation Center (created under the Affordable Care Act) allows the Medicare and Medicaid programs to test models that improve care, lower costs, and better align payment systems with models that support patient-centered practices. Furthermore, Congress provided CMS the authority to expand the scope and duration of models being tested through rulemaking. Evaluating innovative payment and service delivery models to determine whether they are appropriate for expansion and which characteristics are associated with success is a key focus of the Innovation Center (Howell et al., 2015).

The Obama Administration set ambitious goals for the Innovation Center’s study of the effects of payment and delivery reforms; however, the Trump Administration rolled back many of the initial efforts. According to a 2018 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office, of the 37 models for delivering and paying for health care implemented by 2018, very few succeeded in maintaining or reducing health care cost savings while maintaining or enhancing quality (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2018a). The Innovation Center has made investments in models that include postacute or long-term care, some of which addressed the needs of individuals with dementia. Still, the Center could be used to test new models for this population and to provide evidence to support congressional action on new models.

In addition, under the value-based insurance design (VBID) program, plans may apply to test innovative interventions and their benefit design, including cost-sharing reductions, additional supplemental benefits, and targeted benefits for enrollees with certain chronic conditions. The benefits

typically offered are quite limited but include caregiver supports, meal delivery, and transportation for groceries. The goals of the VBID program are to test innovations designed to reduce Medicare spending, enhance quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries, and improve the coordination and efficiency of health care service delivery. Dementia was added explicitly to the list of seven chronic condition categories in 2018.

These flexibilities are new, untested, and as yet not widely utilized by plans. More research on such innovations is needed. While they hold promise, it will be essential for researchers to track their implementation closely; measure their outcomes and return on investment; and ascertain whether and how they reach those with significant, complex conditions such as dementia.

Managed Care

A key focus of innovation has been managed care, an approach to health care in which the financing and delivery of care are integrated, with the goal of improving quality and lowering costs and with potential advantages for the care of people living with dementia. Medicare was originally designed to finance acute hospitalizations, postacute skilled nursing, surgeries, and curative care in the outpatient setting, although its coverage has expanded since it was established in 1965. It generally pays providers on a per-service basis, and each service has a unique code. This approach has meant that definitions of codes and providers’ interpretations of those definitions affect the services received by beneficiaries, as well as the diagnoses associated with each service rendered. In general, this coding system motivates providers to increase the volume and intensity of services rendered to a particular patient instead of striving to avert potentially unnecessary and costly care (Song et al., 2010). Managed care programs have different incentives, encouraging providers to use resources prudently while maximizing patient outcomes, which may permit them to provide better management of care for people living with dementia.9

One promising new opportunity is a set of developments allowing Medicare Advantage plans to deliver supplemental services as part of the Medicare benefit package. This opportunity holds promise for Medicare beneficiaries who need extensive care coordination and some long-term services and supports. The underlying theory is that providing some social supports and other nonmedical assistance can help the beneficiary while also minimizing overuse of costly hospital and nursing home services. One example of this approach is CMS’s modification of the definition of what the nearly 3,000 Medicare Advantage plans nationwide could classify as “primarily health

___________________

9 Medicare Advantage is Medicare’s managed care program.

related services.” The new interpretation includes such services as adult day care, home-based palliative care, in-home support, and memory fitness.

How Managed Care Works

Conceptually, the managed care approach to care delivery and outcomes is driven by three underlying factors: incentives, competition, and organizational capabilities.

In a managed care approach, a health insurance plan bears the risk of paying for covered services for a defined population; payments can be adjusted for patients’ risk and expected health care expenditures so the plan will have less reason to avoid higher-risk patients. With this approach, the plan has an incentive to coordinate care for persons with dementia to reduce unnecessary service use, thus keeping overall costs down. For decades, Medicare Advantage plans were able to attract Medicare beneficiaries who were healthier than the average fee-for-service patient, although the past several years have seen a substantial increase in the number of beneficiaries enrolling in Medicare Advantage plans who have disabilities or are otherwise eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid (Park et al., 2020). Such enrollments may increase as a result of the introduction of dementia into the calculation of codes that determine reimbursement, which took place in 2020.

Competition plays a role in managed care because the presence of managed care plans in a market generates competitive pressure for plans to attract more enrollees through lower premiums, more generous benefits, or better quality of care. Finally, managed care plans have specific organizational capabilities absent from the original Medicare program. Specifically, Medicare providers reimbursed solely through fee-for-service are not part of an organizational structure that is accountable for both care quality and financing. In contrast, organizations providing care through Medicare Advantage have the capacity to manage supply by restricting the providers their members can use and employing other cost-containment approaches, such as utilization review or prior authorization policies. Plans may also influence provider behavior by altering the payment method or profiling providers’ treatment patterns. Or they may contract selectively with more efficient providers and/or attempt to steer enrollees to receive care from such providers by forming restricted provider networks. Finally, plans can engage directly with enrollees to implement preventive health, case management, disease management, or other related interventions.

Medicare Advantage and Dementia Care

How might managed care improve outcomes for dementia patients? First, in contrast to traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage plans have

the flexibility to cover services or alter payment policies in ways that avert preventable spending on hospital care or improve quality of care. For instance, while traditional Medicare will pay for skilled nursing care only for patients who have first experienced a 3-day hospital stay, most Medicare Advantage plans waive this requirement to facilitate direct admission for subacute care in a nursing home (Zissimopoulos et al., 2014; White et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2012; Grebla et al., 2015). Unlike traditional Medicare, moreover, Medicare Advantage plans can elect to cover case management by social workers, adult day care services, respite for caregivers, in-home meal delivery, and other long-term services and supports should the plans decide that these interventions make it possible to avert other medical spending or improve outcomes (White et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2012; Thomas et al., 2019; Durfey et al., 2021).

A few examples illustrate this point. A care consultation service (using the managed care approach) for people living with dementia implemented by a Medicare Advantage plan in Ohio, together with the Cleveland Alzheimer’s Association, achieved lower service utilization, improved patient and family satisfaction, and decreased caregiver strain (Fishman et al., 2019). A case management and quality improvement program implemented by a Medicare Advantage plan in Los Angeles also produced significant improvements in caregiver satisfaction and greater adherence to guideline-based quality measures, including routine assessments of cognition, activities of daily living, decision-making capacity, and wandering risk (Kuo et al., 2008).

Managed care plans may also use health-risk assessments to identify enrollees with cognitive impairment and provide them with intensive case management, which is an important benefit because of the problem with underdiagnosis discussed in Chapter 3 (Lin et al., 2016; Hudomiet et al., 2019; Albert et al., 2002; Eaker et al., 2002; Gaugler et al., 2013; Geldmacher et al., 2013; Suehs et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2010; Bynum et al., 2004; Hill et al., 2002; Carter and Porell, 2005). Finally, managed care organizations can contract selectively with home health and nursing home providers that achieve better outcomes, such as lower read-missions and hospitalization rates for functionally impaired older adults (Albert et al., 2002). Thus, in principle, managed care may help patients live longer in the community and prevent unnecessary hospitalizations.

Risks

Despite its benefits, managed care may also compromise outcomes for people living with dementia. The capitated payment structure (in which physicians are paid a preset monthly amount for each patient) may give Medicare plans an incentive to attract and retain healthier enrollees and to promote the disenrollment of patients with complex health care needs.

There is evidence that Medicare Advantage patients who use short- or long-term nursing home care have high rates of switching to traditional Medicare in the following year (Meyers et al., 2021). This may indicate that Medicare Advantage plans are attempting to “cream-skim” healthy patients so that traditional Medicare will bear the cost when patients enter a period of increased health care needs. Indeed, recent research on disenrollment in Medicare Advantage plans shows that once Medicare beneficiaries receive a dementia diagnosis, they are much more likely to switch back to traditional Medicare or switch to another Medicare Advantage plan relative to Medicare Advantage members without a new dementia diagnosis. This finding is consistent with other research indicating that Medicare Advantage members who have chronic conditions and are users of nursing home or home health services are more likely to disenroll from their plan in the year in which they have these utilization experiences than in other years (Jung et al., 2018; Goldberg et al., 2017, 2018).

Plans may also restrict access to some high-cost services, particularly for frail patients. For example, in a sample of several hundred managed care patients in four California skilled nursing facilities, managed care patients had substantially shorter stays and received less therapy compared with fee-for-service patients, even after adjusting for an extensive set of demographic and clinical variables and site of care (Eaker et al., 2002). Similarly, a study comparing the experiences of Medicare Advantage and fee-for-service patients with hip fracture discharged from a hospital to a skilled nursing facility found, after propensity score matching, that Medicare Advantage patients spent 5 fewer days in the skilled nursing facility but were less likely to be rehospitalized and more likely to remain home (Kumar et al., 2018). In a population-based sample of frail Medicare beneficiaries in San Diego, managed care enrollees received 71 percent fewer home visits compared with fee-for-service participants, independent of health and sociodemographic characteristics (Gaugler et al., 2013). In this same sample, the odds of preventable rehospitalization were 3.51 times higher for Medicare Advantage enrollees than for Medicare fee-for-service participants. A recent national study demonstrated that Medicare Advantage members used less home health care and skilled nursing care and had fewer hospital days compared with Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, controlling for demographic, regional, and clinical factors (Li et al., 2018). These studies support the notion that the practices managed care plans may adopt to limit the use of services may have significant unintended consequences at later points along the continuum of care.

Knowledge gaps

Theoretically, Medicare Advantage plans may be able to manage the care needs of people living with dementia better than the fee-for-service system can precisely because they have an incentive to manage

and coordinate care so as to reduce unnecessary utilization while improving the quality of the care and care partners’ satisfaction with care. Under optimal conditions, Medicare Advantage plans focused on managing their patients’ care could achieve the same sorts of positive outcomes observed in studies of integrated health care delivery systems that provide the full range of inpatient, outpatient, and community-based services.

Unfortunately, there is limited empirical evidence to support this proposition. On the one hand, Medicare Advantage special needs plans are available to some persons living with dementia.10 These plans are tailored to meet needs associated with specific conditions, provide targeted care (e.g., dementia care specialists), and cover drugs typically prescribed for the covered conditions, and they often include a care coordinator. Special needs plans increase the use of primary care and improve the management of such chronic conditions as diabetes (Cohen et al., 2012). However, these plans are now growing rapidly, and further research on their effects would be valuable.

Another relatively new development in the realm of Medicare Advantage plans pertains to the growth of institutional as well as disability-based special needs plans. These plans have begun to draw an increasingly large population of persons who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Disability-based special needs plans that cover permanent residents of nursing homes combine the per diem payment for nursing home care from Medicaid with the highest level of Medicare monthly payment for those patients with the most complex mix of diagnoses.

Although there is ample evidence that enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans have lower rates of hospitalization and readmission relative to those enrolled in traditional Medicare, after risk adjustment, whether these broad differences are applicable to people living with dementia is unknown (Cohen et al., 2012). Furthermore, like other populations with high needs and costs, those with dementia appear to be particularly likely to disenroll from Medicare Advantage. It is not known, however, whether these disenrollment choices are made by the person with dementia or a caregiver, or whether they reflect subtle pushes from the Medicare Advantage plan itself. It will be important to determine whether disenrollment reflects patients’ dissatisfaction with access to care and care coordination or has some other cause.

Several recent policy changes have increased the flexibility of Medicare Advantage plans in meeting the needs of people living with dementia. In 2019, for example, the list of Medicare Advantage plan benefits was expanded to include adult day care, in-home personal care attendants,

___________________

10 For more information, see https://www.medicare.gov/sign-up-change-plans/types-ofmedicare-health-plans/special-needs-plans-snp.

home safety, and assistive devices. In 2020, plans were allowed to offer supplemental benefits, including home-delivered meals, help with daily activities, and nonmedical transportation, to chronically ill beneficiaries. While some of these services were available to some people living with dementia before these policy changes, access to them was constrained by income limits, as well as local availability. The recent changes make it possible for Medicare Advantage plans to offer services that directly address some of the social needs that are significant determinants of health outcomes for frail and chronically ill beneficiaries such as people living with dementia.

Because these changes are recent, however, there is little empirical evidence about how Medicare Advantage plans are organizing such services and making them available, or whether the services are effective in improving quality of life. It will be important to study how Medicare Advantage plans contract with and arrange for these services for their chronically ill members. Indeed, because Medicare Advantage plans are serving more individuals living with dementia and an increasingly impaired population, research on how different types of Medicare Advantage plans can affect the care and outcomes experienced by persons living with dementia is critical. The structure of emerging special needs plans varies, so it will be important to examine whether any of these structures are more effective than the others in improving the outcomes of persons with dementia living in nursing homes (Meyers et al., 2020). New alternative payment models (e.g., accountable care organizations, primary care first, direct contracting) also allow the flexibility to provide greater benefits for people living with dementia. Whether these models will also provide augmented payment to cover services for people living with dementia remains to be determined.

RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

The committee identified numerous gaps in the available research on the capacity of the health care system and long-term and end-of-life care to meet the needs of people living with dementia and their families. With respect to health care, we point to the need for observational research using existing data (e.g., electronic health records, administrative claims data) to develop more detailed understanding of patients’ needs as they move through the stages of dementia and related questions. Research on new models of care is also needed. In addition to intervention development research, further evaluation research is needed as well, including

- traditional clinical trials;

- pragmatic trials; and

- quasi-experimental designs (e.g., stepped wedge) (Hemming et al., 2015), as well as hybrid designs that include a summative

- evaluation of the impact of an intervention, treatment, or practice and formative evaluation of the implementation process itself (Curran et al., 2012).

To date, moreover, there has been minimal research on how to accelerate the implementation and dissemination of successful models, which will be necessary if the products of intervention research are to reach large numbers of persons with dementia.

The committee also identified gaps in research on residential and community-based long-term care. Cluster randomized and quasi-experimental studies are needed to define the critical elements of assisted living facilities, including those with dementia/memory care programs, and their effectiveness in real-world settings. The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the need for study of the current structure and processes of nursing homes, and studies examining the failures and successes of nursing homes during the pandemic may provide insights for nursing home reform. Study of alternatives to the current nursing home structure (e.g., smaller facilities serving fewer than 20 individuals that emphasize a home-like environment) is needed to determine what influences patients’ and families’ choices and how to disseminate and finance preferred options. Research also is needed on how and when to implement palliative and hospice care to provide the optimal benefit for persons living with dementia; these questions could be addressed through Medicare demonstration projects, such as those included under Medicare Advantage.

Study of the barriers to financing new, effective approaches to dementia care, particularly in fee-for-service settings, is also needed. Research evaluating new payment models, including managed care plans, and their outcomes and the potential to use their flexibility to provide additional services that improve dementia care would provide evidence as to whether the potential of these plans is being fulfilled. Research on the structures of different dementia services offered by health plans and, in turn, their effects on quality of care and outcomes among Medicare Advantage beneficiaries could provide insight into how policies and regulations pertaining to dementia care can best be revised. Such research conducted over the next decade could support the development of policy and the delivery of more effective, more efficient care.

The committee identified priority areas for additional research on how persons living with dementia and their caregivers interact with and are served by the health and social service systems in the domains of the quality and structure of health care, the quality and structure of long-term and end-of-life care, and financing of dementia care. These research needs are summarized in Conclusions 6-1, 6-2, and 6-3 and detailed in Tables 6-1, 6-2, and 6-3, respectively.

CONCLUSION 6-1: Research in the following areas has the potential to substantially strengthen the quality and structure of the health care provided to people living with dementia:

- Documentation of the diagnosis and care management received by persons living with dementia from their primary care providers.

- Clarification of disease trajectories to help health systems plan care for persons living with dementia.

- Identification of effective methods for providing dementia-related services (e.g., screening and detection, diagnosis, care management and planning, transition management) for individuals living with dementia throughout the disease trajectory.

- Development and evaluation of standardized systems of coordinated care for comprehensively managing multiple comorbidities for persons with dementia.

- Identification of effective approaches for integrating care services across health care delivery and community-based organizations.

TABLE 6-1 Detailed Research Needs

| 1: Documentation of Care Received from Primary Care Providers |

|

| 2: Clarification of Disease Trajectories |

|

| 3: Identification of Effective Methods for Providing Dementia Care Services |

|

| 4 and 5: Standardized Systems of Coordinated Care and Integrated Care Services |

|

CONCLUSION 6-2: Research in the following areas has the potential to substantially strengthen the quality and structure of long-term and end-of-life care provided to people living with dementia:

- Identification of future long-term and end-of-life needs and available care for persons living with dementia.

- Description and monitoring of factors that contribute to problems with nursing home quality, particularly in light of the acceleration

- of those problems caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, to provide evidence for ongoing changes to the long-term care system.

- Development and evaluation of alternatives to traditional nursing home facilities, including home care options and innovative facility designs.

- Improved understanding of how and when patients use palliative and hospice care options and variation in the end-of-life care available across regions and populations.

TABLE 6-2 Detailed Research Needs

| 1: Long-Term and End-of-Life Patient Needs and Available Care |

|

| 2: Improved Nursing Home Quality |

|

| 3: Development and Evaluation of Alternative Long-Term Care Options |

|

| 4: Use of and Variation in End-of-Life Care |

|

CONCLUSION 6-3: Research in the following areas has the potential to substantially strengthen the arrangements through which most dementia care is funded—traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage, alternative payment models, and Medicaid:

- Comparison of the effects of different financing structures on the quality of care and clinical outcomes for persons living with dementia, as well as effects on their caregivers.

- Examination of ways to modify incentives in reimbursement models to optimize care and reduce unnecessary hospitalizations and other negative outcomes for people living with dementia.

- Development and testing of approaches to integrated financing of medical and social services.

Finally, we note that persistent challenges affect the workforces in both health care and the direct care system. Issues that go well beyond the context of dementia care have been documented. These include, to name a few, shortages of qualified workers, limitations in the quality and availability of training and education for both prospective workers and those developing their careers, as well as multiple factors specific to domains within these sectors. The aging of the U.S. population is likely to exacerbate the stress on these workforces, as the ratio of working-age people to older people shifts. The issues are likely to be most acute for the direct care workforce because of financial disincentives such as low pay and poor benefits, as well as limited opportunities for career advancement.

TABLE 6-3 Detailed Research Needs

| 1: Comparative Effectiveness of Financing Structure |

|

| 2: Ways to Modify Incentives |

|

| 3: Evaluation of Approaches to Integrated Financing |

|

Many of the challenges that affect the supply of qualified individuals to care for people living with dementia are broad workforce issues for the entire health care system and the providers of direct care for the elderly and people with disabilities. These include, for example, national-level health care policies affecting payment and insurance as well as workforce trends and policies affecting lower-income workers. Little of the potentially pertinent research is structured by the diagnosis of persons being cared for. It was beyond the scope of this study to conduct a review of the state of the research in each of the relevant areas that was detailed enough to support specific conclusions about the research direction that should be given highest priority. Nevertheless, we regard emerging knowledge about workforce issues as a vital complement to the research directions described here.

REFERENCES

Abrams, H.R., Loomer, L., Gandhi, A., and Grabowski, D.C. (2020). Characteristics of U.S. Nursing Homes with COVID-19 Cases. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(8), 1653–1656. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16661

Adler, J. (2018, June 4). Investors Rethink Memory Care. Seniors Housing Business. https://seniorshousingbusiness.com/investors-rethink-memory-care

Albert, S.M., Glied, S., Andrews, H., Stern, Y., and Mayeux, R. (2002). Primary care expenditures before the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology, 59(4), 573–578. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.59.4.573

Altman, D. (2020, July 21). Hotspot states see more COVID cases in nursing homes. Axios. https://www.axios.com/coronavirus-cases-infections-nursing-homes-b5260d20-47f24a56-9574-e63e9dafd012.html

American Board of Medical Specialties. (2020). ABMS Board Certification Report 2019–2020. https://www.abms.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ABMS-Board-Certification-Report2019-2020.pdf

Amjad, H., Carmichael, D., Austin, A.M., Chang, C.-H., and Bynum, J.P.W. (2016). Continuity of care and healthcare utilization in older adults with dementia in fee-for-service Medicare. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(9), 1371–1378. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3553

Angelelli, J., Mor, V., Intrator, O., Feng, Z., and Zinn, J. (2003). Oversight of nursing homes: Pruning the tree or just spotting bad apples? Gerontologist, 43(suppl 2), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.67

Ausserhofer, D., Deschodt, M., De Geest, S., van Achterberg, T., Meyer, G., Verbeek, H., Sjetne, I.S., Malinowska-Lipien, ´ I., Griffiths, P., Schlüter, W., Ellen, M., and Engberg, S. (2016). “There’s no place like home”: A scoping review on the impact of homelike residential care models on resident-, family-, and staff-related outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17(8), 685–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.03.009

Bardenheier, B.H., Rahman, M., Kosar, C., Werner, R.M., and Mor, V. (2020). Successful discharge to community gap of FFS Medicare beneficiaries with and without ADRD narrowed. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(4), 972–978. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16965

Bentkover, J., Cai, S., Makineni, R., Mucha, L., Treglia, M., and Mor, V. (2012). Road to the nursing home: Costs and disease progression among Medicare beneficiaries with ADRD. America Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 27(2), 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317512440494

Boustani, M., Alder, C.A., Solid, C.A., and Reuben, D. (2019). An alternative payment model to support widespread use of collaborative dementia care models. Health Affairs, 38(1), 54–59. https://doi.org/doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05154

Brown, J.R., Goda, G.S., and McGarry, K. (2012). Long-term care insurance demand limited by beliefs about needs, concerns about insurers, and care available from family. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 31(6), 1294–1302. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1307

Bunn, F., Burn, A-M., Goodman, C., Rait, G., Norton, S., Robinson, L., Schoeman, J., and Brayne, C. (2014). Comorbidity and dementia: A scoping review of the literature. BMC Medicine, 12, 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0192-4

Bynum, J.P., Rabins, P.V., Weller, W., Niefeld, M., Anderson, G.F., and Wu, A.W. (2004). The relationship between a dementia diagnosis, chronic illness, Medicare expenditures, and hospital use. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52(2), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52054.x

Callahan, C.M., Boustani, M.A., Unverzagt, F.W., Austrom, M.G., Damush, T.M., Perkins, A.J., Fultz, B.A., Hui, S.L., Counsell, S.R., and Hendrie, H.C. (2006). Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 295(18), 2148–2157.

Carter, M.W., and Porell, F.W. (2005). Vulnerable populations at risk of potentially avoidable hospitalizations: The case of nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 20, 349–358.

Chatterjee, P., Kelly, S., Qi, M., and Werner, R.M. (2020). Characteristics and quality of U.S. nursing homes reporting cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Network Open, 3(7), e2016930. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16930

Chen, M.K, Chevalier, J.A., and Long, E.F. (2020). Nursing Home Staff Networks and COVID-19. NBER Working Paper 27608. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27608

Clevenger, C.K., Cellar, J., Kovaleva, M., Medders, L., and Hepburn, K. (2018). Integrated memory care clinic: Design, implementation, and initial results. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(12), 2401–2407. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15528

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). (n.d.). Medicare Hospice Benefits. https://www.medicare.gov/Pubs/pdf/02154-medicare-hospice-benefits.pdf

———. (2020a). Medicare Enrollment Dashboard. https://www.cms.gov/Research-StatisticsData-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/CMSProgramStatistics/Dashboard

———. (2020b). Total Medicare Enrollment: Total, Original Medicare, and Medicare Advantage and Other Health Plan Enrollment, Calendar Years 2014-2019. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2019cpsmdcrenrollab1.pdf

———. (2021a). Cognitive Assessment and Care Plan Services. https://www.cms.gov/cognitive

———. (2021b). Hospice. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/Hospice

Cohen, R., Lemieux, J., Schenborn, J., and Mulligan, T. (2012). Medicare Advantage chronic special needs plan boosted primary care, reduced hospital use among diabetes patients. Health Affairs, 31(1), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0998

Curran, G.M., Bauer, M., Mittman, B., Pyne, J.M., and Stetler, C. (2012). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care, 50(3), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812

Drabo, E., Barthold, D., Joyce, G., Ferido, P., Chui, H., and Zissimopoulos, J. (2019). Longitudinal analysis of dementia diagnosis and specialty care among racially diverse Medicare beneficiaries. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 15(11), 1402–1411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.07.005

Durfey, S., Gadbois, E.A., Meyers, D.J., Brazier, J.F., Wetle, T., and Thomas, K.S. (2021). Health care and community-based organization partnerships to address social needs: Medicare Advantage Plan representatives’ perspectives. Medical Care Research and Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775587211009723

Eaker, E.D., Mickel, S.F., Chyou, P.H., Mueller-Rizner, N.J., and Slusser, J.P. (2002). Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia and medical care utilization. Annals of Epidemiology, 12, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00244-7

Evans, C.J., Ison, L., Ellis-Smith, C., Nicholson, C., Costa, A., Oluyase, A.O., Namisango, E., Bone, A.E., Brighton, L.J., Yi, D., Combes, S., Bajwah, S., Gao, W., Harding, R., Ong, P., Higginson, I.J., and Maddocks, M. (2019). Service delivery models to maximize quality of life for older people at the end of life: A rapid review. Milbank Quarterly, 97(1), 113–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12373

Fishman, P., Coe, N.B., White, L., Crane, P.K., Park, S., Ingraham, B., and Larson, E.B. (2019). Cost of dementia in Medicare managed care: A systematic literature review. American Journal of Managed Care, 25(8), e247–e253.

Flynn, H., Morley, M., and Bentley, F. (2020, September 8). Hospital discharges to home health rebounding, but SNF volumes lag. Avalere. https://avalere.com/press-releases/hospital-discharges-to-home-health-rebound-while-snf-volumes-lag

Fowler, N.R., Frame, A., Perkins, A.J., Gao, S., Watson, D.P., Monahan, P., and Boustani, M.A. (2015). Traits of patients who screen positive for dementia and refuse diagnostic assessment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 1(2), 236–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2015.01.002

Fowler, N.R., Campbell, N.L., Pohl, G.M., Munsie, L.M., Kirson, N.Y., Desai, U., Trieschman, E.J., Meiselbach, M.K., Andrews, J.S., and Boustani, M.A. (2018). One-year effect of the Medicare annual wellness visit on detection of cognitive impairment: A cohort study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(5), 969–975. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15330

Ganguli, I., Souza, J., McWilliams, J.M., and Mehrotra, A. (2017). Trends in use of the U.S. Medicare annual wellness visit, 2011-2014. Journal of the American Medical Association, 317(21), 2233–2235. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.4342

Garfield, R., Musumeci, M.B., and Reaves, E.L. (2015). Medicaid’s role for people with dementia. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaids-role-for-people-with-dementia

Gaugler, J.E., Hovater, M., Roth, D.L., Johnston, J.A., Kane, R.L., and Sarsour, K. (2013). Analysis of cognitive, functional, health service use, and cost trajectories prior to and following memory loss. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 68(4), 562–567. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs078

Geldmacher, D.S., Kirson, N.Y., Birnbaum, H.G., Eapen, S., Kantor, E., Cummings, A.K., and Joish, V.N. (2013). Pre-diagnosis excess acute care costs in Alzheimer’s patients among a U.S. Medicaid population. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 11, 407–413.

Gleckman, H. (2019, May 15). What you need to know about Washington State’s public long-term care insurance program. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/howardgleckman/2019/05/15/what-you-need-to-know-about-washington-states-public-longterm-care-insurance-program/?sh=493dcc982cdc

Goldberg, E.M., Trivedi, A.N., Mor, V., Jung, H.Y., and Rahman, M. (2017). Favorable risk selection in Medicare Advantage: Trends in mortality and plan exits among nursing home beneficiaries. Medical Care Research and Review, 74(6), 736–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558716662565