5

Alternative Management Strategies for Recreational Fisheries

It is widely agreed that, thanks to implementation of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA) and its multiple reauthorizations, America’s fisheries are among the best-managed in the world, and overfishing has been all but eliminated in U.S. waters. Federally managed fish stocks have established annual catch limits (ACLs) that cannot be exceeded, and fishery managers must employ accountability measures (AMs)—management controls that prevent ACLs from being exceeded or mitigate overages (NRC, 2014).

Historically, commercial and recreational fishers have largely supported implementation of the MSA because of the law’s contributions to the long-term stability of fish stocks, a profitable fishing industry, and a vibrant coastal economy. However, in the midst of the nation’s success in rebuilding marine fisheries and the growth in saltwater recreational fishing, some recreational fisheries advocates began expressing their perception that the U.S. federal fisheries management system has not adapted to meet the unique goals and needs of anglers. In spring 2014, the Commission on Saltwater Recreational Fisheries Management—better known as the Morris-Deal Commission (after its two initial chairs—Johnny Morris, CEO of Bass Pro Shops, and Scott Deal, president of Maverick Boats)—published A Vision for Managing America’s Saltwater Recreational Fisheries (CSRFM, 2014), a landmark report providing a number of recommendations on potential strategies for improving saltwater recreational fisheries management. More recently, other recreational fisheries support organizations, such as the American Sportfishing Association (ASA) and the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership (TRCP), have conducted workshops, convened expert panels, and released a subsequent report providing additional recommendations for addressing recreational fisheries management issues (ASA and TRCP, 2018). The common thread in these recommendations is that recreational and commercial fishing are fundamentally different activities, and therefore require different management approaches.

ALTERNATIVE MANAGEMENT APPROACHES THAT COULD BE APPLIED TO RECREATIONAL FISHERIES

In light of the concerns raised by recreational fisheries industry organizations and in response to the recommendations provided by the expert panel and workshop reports referenced above, Section 102 of the MFA specifies that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) National Marine Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries) and the Regional Fishery Management Councils (Councils) can implement alternative management approaches more suitable to the nature of recreational fishing as long as they still adhere to the conservation principles and requirements established by the MSA. An overview of the most common alternative management approaches that have been proposed by recreational fishing groups and that, in some cases, are under consideration by Councils is presented in Table 5.1. The approaches being proposed vary widely in nature and attempt to address different management challenges raised by the recreational fisheries sector. Although they are discussed here on an individual basis, it is also possible to combine them in a variety of ways to form hybrid management options (CSRFM, 2014).

Harvest Rate Management

The harvest rate management (HRM) approach centers around the use of target fishing mortality rates (F) to reach a desired level of removals and maintain sustainable spawning-stock biomass (SSB). The idea is that recreational fishing is not always based on harvest, and therefore not as suitable for the poundage-based hard quotas (i.e., ACLs) required by the current federal management system.

Although conceptually, managing fisheries based on harvest rates makes sense, the use of this approach faces multiple challenges. First, data and analytical requirements are extremely high (see Table 5.1). Because under HRM fishery management is based on F values instead of landings, monitoring of stock status requires frequent (ideally annual) assessment updates so an estimate of current F can be obtained for comparison with target F. For example, to manage the Atlantic Striped Bass fishery using HRM, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) uses a strategy that sets a threshold and target F that provides a desired level of SSB. Each year, landings and biological information, such as juvenile indices of abundance, are reviewed relative to trends and targets. Depending on this comparison, the ASMFC may direct states to adjust management measures. Approximately every 2 years, the stock assessment is updated, and the catch levels associated with the target harvest rate are adjusted. Management changes resulting from updated assessments are typically expressed as a percent change in harvest levels from the prior period, rather than as an ACL-style hard catch limit. There are fishing seasons but no in-season closures, and anglers in different states may be subject to more restrictive measures the following season if a reduction in landings in their state is required to meet the coastwide F-target. For example, a state may set a season length with associated size and bag limits that is predicted to constrain catch to a specific level, consistent with the coastwide target fishing mortality rate. However, if post-season evaluation determines that realized catch has exceeded expected catch, that state’s fishery may be subject to a shorter season, lower bag limit, or higher size limit the following year. Monitoring of harvest for the purpose of closing the fishery early (should harvest exceed expectations) does not occur.

But perhaps the most severe challenge facing the use of HRM as an alternative management approach is that it may not comply with MSA mandates and National Standard (NS) 1 guidelines requiring that federally managed stocks (i.e., stocks in Councils’ Fishery Management Plans [FMPs]) be managed with an ACL (NRC, 2014). Specifically, the MSA as amended in 2006 states that a Council will “develop annual catch limits for each of its managed fisheries that may not exceed the fishing level recommendations of its scientific and statistical Committee or the peer

TABLE 5.1 Overview of the Most Common Alternative Management Approaches Being Discussed by Recreational Fisheries Support Organizations and Regional Fishery Management Councils

| Management Strategy | Description | Data Needs or Gaps | Potential Benefits | Potential Challenges | Example Fisheries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvest rate management | Use of fishing mortality rate (F) as the main reference point for managing the fisheries Does not involve the use of an annual catch limit (ACL) or other landings- or quota-based hard catch limit |

Annual measure of F; annual juvenile indices of abundance (to track annual recruitment, year-class strength) | Does not require the use of a hard catch limit; management adjusted in response to changes in F Perceived by anglers as better suited to recreational fisheries management (i.e., not a pounds-based quota) |

Data-intensive. Requires annual assessment updates so estimate of current F can be obtained May not comply with the National Standards (NS) 1 requirement that fisheries under a Council Fishery Management Plan (FMP) be managed using ACLs Requires formal annual plan review |

Atlantic Striped Bass (managed by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission [ASMFC]) |

| Harvest tags | Tags are used to track harvest of individual fish. Similar to the process used to control harvest in wildlife game management (bear, elk, deer, etc.). |

Recreational fisheries licensing and data collection systems capable of handling the harvest tags | Improves data collection or control effort Well suited for highly controlled, limited-harvest fisheries that are difficult to manage with traditional fisheries regulations (e.g., rare-event species or species under Endangered Species Act recovery plans) Can provide greater flexibility for anglers to harvest when convenient |

Fair distribution (open lottery versus open access versus allocation) Difficult to implement, administer, and enforce across federal–state jurisdictions Burdensome and prescriptive reporting requirements Requires compliance tracking effort Perceived by the recreational community as restricting access (i.e., the fisheries are no longer open-access) |

Highly migratory species fisheries in North Carolina and Maryland Salmon and Halibut in Oregon and Washington Tarpon in Florida and Alabama |

| Management Strategy | Description | Data Needs or Gaps | Potential Benefits | Potential Challenges | Example Fisheries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depth-distance-based management | Recreational fishing for single or multiple species is closed beyond a certain depth or distance from shore to allow higher production outside the fishing zone, potentially replenishing the fishing zone and reducing release mortality | Knowledge of the proportion of the stock’s spawning-stock biomass (SSB) that occupies the deep/distant-from-shore area Connectivity between the two stock components (i.e., the deep/distant and the inshore/near-shore components) |

Longer seasons, increased access in shallow/near-shore areas Decreased fishing pressure and reduced release mortality by focusing fisheries in shallower areas |

Viable only if portion of SSB in the deep/distant area is sufficient to replenish the near-shore area Reduced access to other, non-overfished stocks in the deep/distant-from-shore area (can be perceived as turning the deep/distant-from-shore area into a large closed area) Federal–state coordination on managing the nearshore area Compliance and enforcement |

Pacific Rockfish conservation areas Considered by the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council for South Atlantic Red Snapper |

| Conservation equivalency | States can implement alternative management measures that are estimated to achieve the same conservation goals as those of the Councils | Recreational fisheries data appropriate to support necessary analyses (i.e., to assess whether state conservation equivalency measures achieve the conservation level required by the Council) States in the Council region need calibrated and compatible recreational fisheries data |

Added flexibility to address differential management needs over broad Council region (e.g., state-by-state differences in fishing effort or species distribution) Improved angler trust, compliance, and cooperation |

Requires sufficient recreational fisheries data at the state level to support development of conservation equivalency measures Inconsistent regulations across the region could be a challenge for the regional stock assessment Perceived inequities in management due to differing state-by-state regulations Conservation equivalency proposal approved annually |

Atlantic Summer Flounder and Black Sea Bass (managed by ASMFC) State management of the private recreational component of Gulf of Mexico Red Snapper (Amendment 50 to the reef fish FMP) |

| Management Strategy | Description | Data Needs or Gaps | Potential Benefits | Potential Challenges | Example Fisheries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permits, endorsements, and stamps | Special permits, license endorsements, or stamps are required for possession or harvest of a species or group of species | Supplemental recreational fisheries data collection program Recreational fisheries licensing system capable of handling the additional permits, endorsement, and stamps |

Better-defined universe of anglers, improved sampling frame for surveys Reduced scientific and management uncertainty (if better-defined universe of anglers leads to better surveys and improved quota monitoring) Increased access (if lower uncertainty leads to smaller buffers and thus higher ACLs) |

Difficult to implement and administer from a federal–state licensing perspective Compliance and enforcement Cost (programs of this nature entail additional implementation, administrative, and enforcement costs) |

Gulf of Mexico Red Snapper state programs (Florida State Reef Fish Survey, Alabama Snapper Check, Mississippi Tails ‘n Scales, Louisiana LA Creel) Alaska King Salmon stamp Mid-Atlantic recreational Tilefish permit (Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council) |

review process.”1 The act also requires FMPs to “establish a mechanism for specifying annual catch limits in the plan (including a multi-year plan), implementing regulations, or annual specifications, at a level such that overfishing does not occur in the fishery, including measures to ensure accountability.”

Fundamentally, the current ACL-based catch specification system is already based on F values, as ACLs are obtained by multiplying the FABC/ACL by the estimated annual stock biomass (B) over the projection period. It appears that the recreational fisheries sector’s dissatisfaction with this approach (besides the use of pounds-based hard quotas) may be related to the inherent uncertainty of fishery projections. Annual estimates of stock biomass (B) are strongly dependent on estimated annual recruitment, a highly uncertain metric. Actual annual recruitment in a given year may end up being higher or lower than estimates used in projections and projected annual biomass, and therefore may not closely reflect what anglers are seeing out on the water. Compounding the issue is that previous years and MRIP waves are often not good predictors of current-year recreational landings because of significant interannual variability in such factors as fish availability, targeted fishing effort, and weather. This disconnect between stock assessment projections and more realtime perceptions of stock abundance experienced by fishers out on the water represents one of the main challenges with which the current fisheries assessment–management system must contend when dealing with recreational fisheries.

It is also important to note that HRM is a tool that may not be appropriate for all stocks. The ASMFC has 27 FMPs, including those covering, for example, coastal Sharks and Shad and River Herring that include multiple species or stocks. Not all of these stocks are managed the same as

___________________

1 Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, Pub. L. No. 109-479 § 103(c)(3), 121 Stat. 3575, 3581 (2006).

Striped Bass. Therefore, HRM should be considered another tool that the Councils could use in appropriate situations rather than a change in the management approach for all stocks.

Harvest Tags

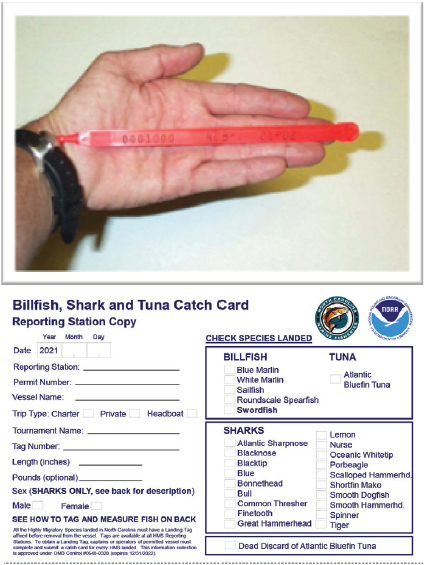

This approach relies on the use of a physical tag to track the harvest of individual fish (see Figure 5.1). Harvest tags are relatively common in wildlife management (e.g., bear, elk, deer), used to limit or account for animals harvested during hunting seasons. In marine fisheries, harvest tags have been used in some highly controlled, limited harvest fisheries, such as Tarpon in Florida and Alabama and Salmon and Halibut in Oregon and Washington, as well as highly migratory species (HMS) (Billfishes, Sharks, and Tunas) in Maryland and North Carolina. In many cases, harvest tag programs also include a companion harvest or landing card used for reporting data associated with the harvest (see Figure 5.1).

In the context of fisheries managed with ACLs by Councils, harvest tags could provide a number of potential benefits. They are well suited to improving data collection or controlling harvest of species with low ACLs or rare-event species that are difficult to sample with traditional recreational fisheries surveys such as MRIP (e.g., deepwater species managed by the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council [SAFMC], such as Snowy Grouper, Wreckfish, Golden Tilefish, and Yellowfin Grouper that regularly have percentage standard errors [PSEs] in excess of 50 percent). A stakeholder engagement process conducted by the American Sportfishing Association (ASA),

SOURCE: North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries, 2014.

Yamaha Marine Group, and the Coastal Conservation Association (CCA) in 2018–2019 to explore new ideas for management of the private recreational sector of the South Atlantic Snapper-Grouper fishery found that meeting participants were supportive of harvest tags for certain deepwater species (ASA, 2019). However, they noted that the number of anglers targeting these species is low compared with other Snapper-Grouper species, and most anglers would not be interested in obtaining a tag for species they do not usually target. This would make the allocation pool likely to be self-limiting, which could help address concerns raised during previous Council discussions about how to distribute tags fairly.

The use of harvest tags in recreational fisheries also presents a number of potential challenges (Johnston et al., 2007). Main concerns raised consistently by stakeholders have been (1) fair and equitable distribution among a diversity of angler interests and (2) the potential to limit angler access, especially if the tag program is applied to higher-demand fisheries and causes the fisheries to no longer be open access. For example, the ASA-CCA stakeholder engagement process in the South Atlantic (ASA, 2019) found that anglers felt tags should be available to all anglers, but some kind of extra effort should be required (e.g., calling to request the tag the day before a trip) to limit tag recipients to interested anglers. Similar angler engagement workshops (ASA and TRCP, 2018; GAFGI, 2017) focused on both the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico concluded that while harvest tags could be made available through an open lottery, depending on the popularity of the fisheries in question, an open lottery could create high demand whereby many anglers who entered the lottery would not win a tag and would not be allowed to harvest their preferred fish.

Some Councils have discussed potential use of harvest tags for certain recreational fisheries (e.g., SAFMC deepwater species). Unfortunately, it appears that a variety of concerns regarding how to handle implementation, administration, and enforcement of a program of this nature across federal–state jurisdictions inevitably bring these discussions to a halt. For example, the SAFMC explored the use of harvest tags for recreational harvest of Red Snapper, Snowy Grouper, Golden Tilefish, and Wreckfish in Snapper Grouper Amendment 22, but did not proceed with developing the amendment. NOAA General Counsel advised that a harvest tag program may need to meet the regulatory requirements for a limited access privilege program under the MSA, an issue also raised during the Gulf angler focus group discussions on tags for Gulf Red Snapper. Other concerns were also raised regarding how tags would be distributed and the effects of private and for-hire recreational participants not having access to a species if tags were made available to nonparticipants as well. The Council suspended development of Amendment 22 in March 2015. More recently, the joint working group formed by the SAFMC and Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council (GMFMC) in 2020 to discuss alternative management approaches under the MFA decided that, at least for now, they would not consider the use of harvest tags for improving data collection or controlling fishing effort or harvest. Collectively, these concerns highlight the many potential challenges associated with the development and implementation of harvest tags and suggest that realizing the advantages of harvest tag programs requires a well-conceptualized plan tailored to the specific fisheries involved and the preferences and attributes of different types of anglers.

Depth-Distance-Based Management

This approach involves closing recreational fishing harvest for single or multiple species beyond a certain depth or distance from shore. The basis for depth-distance-based management is that the portion of the stock in deeper waters would be protected from fishing pressure and experience reduced release mortality, leading to increased stock abundance and biomass and potentially helping replenish the shallower areas that remain open to harvest. Councils would need to coordinate with the states for a depth/distance approach to be successful because zones open to fishing are supposed to occur in areas that are shallower/closer to shore and are likely to be under state

jurisdiction. Also, this approach appears to be difficult to apply in multispecies fisheries—if fishing for other, non-overfished species in the deep/distant-from-shore area were permitted, there could be incidental catch of the species being managed, and the benefits of a closed, replenishment area would no longer be achieved.

Data needs for implementing this approach are not insignificant. For example, detailed data on fishing grounds are necessary to identify the boundaries of the spatial closure, along with information on the extent and composition of the portion of the stock that occupies the deep/distant-from-shore area. If these areas contain only a small portion of the stock or if they are occupied primarily by sexually immature fish that do not contribute to the stock’s spawning biomass, the benefits of protection from fishing mortality and the probability that this portion of the stock could help replenish shallower/closer-to-shore areas would likely not be realized.

Another main challenge with this approach is that the expected reduction in fishing pressure may not occur if a large proportion of the harvest for the species in question already occurs nearer to shore, along with potential issues with compliance and enforcement of the fishing zone boundary. For example, a number of studies have documented that area closures (usually marine protected areas [MPAs]) focused on protecting fish-spawning aggregations can sometimes generate an “edge effect” whereby intense fishing activity becomes concentrated immediately outside of the MPA boundary where transient fish become vulnerable to harvest, thus compromising the conservation benefits of the closed area (Eklund et al., 2000; Ellis and Powers, 2012).

A version of the depth/distance-from-shore management approach has been implemented on the West Coast with some level of success, but in general its application has been limited. An example of its successful use is the implementation of Rockfish conservation areas (RCAs), depth-based closed areas along the U.S. Pacific Coast set to minimize the bycatch of overfished Groundfish species or to protect Groundfish habitat.2 RCAs extending along all or part of the U.S. Pacific Coast have been in place since September 2002. The RCA boundaries are lines that connect a series of latitude and longitude coordinates and are intended to approximate particular depth contours. RCA boundaries are set primarily to minimize incidental catch of overfished Rockfish (Sebastes spp.) by eliminating fishing at locations and times when those overfished species are likely to co-occur with healthy target stocks of Groundfish. Boundaries can be different depending on what types of fishing gear are being used and are likely to differ between the northern and southern areas of the coast (Marks et al., 2015).

Conservation Equivalency

Conservation equivalency is a management approach that gives states the flexibility to develop alternative fishery regulations that address specific state or regional differences while achieving the same conservation goals as those described in FMPs. This allows states to tailor fisheries management to the preferences of their recreational fishing community and account for regional disparities in fish stock abundance or availability while still achieving equivalent conservation benefits to the resource (ASMFC, 2017). From an angler’s perspective, having the same management measures across the broader geographic area managed by the Councils can be problematic. For example, anglers in some states may prefer to fish weekends, while anglers in other states may want a season that is open 7 days per week. Because of weather or school or work schedules, anglers in some states may prefer shortened seasons with larger creel limits over longer seasons with smaller creel

___________________

2 Magnuson-Stevens Act Provisions; Fisheries Off West Coast States; Pacific Coast Groundfish Fishery; Pacific Fishery Management Plan; Amendment 28. See https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/11/19/2019-24684/magnuson-stevens-act-provisions-fisheries-off-west-coast-states-pacific-coast-Groundfish-fishery.

limits. Or perhaps fishing seasons may be set for a migratory species in such a way that anglers in certain regions rarely get the chance to participate in the fishery (ASA and TRCP, 2018).

The ASMFC employs the concept of conservation equivalency in a number of interstate fishery management programs under its jurisdiction. However, in practice ASMFC frequently uses the term “conservation equivalency” in different ways depending on the language included in the plan in question. Also, approval of conservation equivalency as a valid management approach is contingent on a multistep approval process. During development of the management document, the Plan Development Team provides a determination as to whether conservation equivalency is an approved option for that specific fishery management plan because its use may not be appropriate or necessary for all management programs. This determination is based on predefined criteria that include stock status, stock structure, data availability, range of the species, socioeconomic information, and the potential for more conservative management when stocks are overfished or overfishing is occurring. Furthermore, states have the responsibility of developing conservation equivalency proposals for submission and review by a Plan Review Team (PRT), and the state submitting the proposal has the obligation to ensure that proposed measures are enforceable. If the PRT has a concern regarding the enforceability of a proposed measure, it can task the Law Enforcement Committee with reviewing the proposal. Upon approval of a conservation equivalency proposal, implementation of the program becomes a compliance requirement for the state. Each of the approved programs should be described and evaluated in the annual compliance review and included in annual FMP reviews. The ASMFC’s interstate management program has a number of joint or complementary management programs with NOAA Fisheries, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and the Councils. ASMFC policies recognize that implementation of conservation equivalency measures places an additional burden on the Commission to coordinate with federal fishery management partners and recommends that to facilitate this coordination, a number of factors (e.g., stock status, stock structure, data availability, range of the species, and socioeconomic information) should be observed before a joint conservation equivalency plan can be approved.

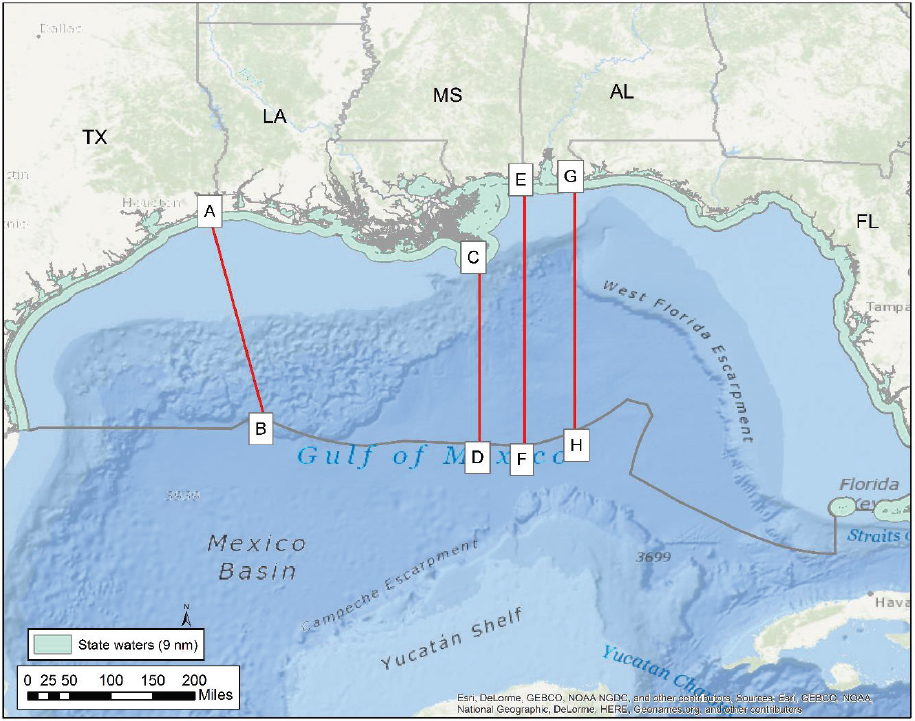

In the context of fisheries managed by Councils, the use of this approach has been extremely rare. An exception is the GMFMC’s implementation of a State Management Program for Recreational Red Snapper (Amendment 50 to the reef fish FMP). This amendment establishes the structure through which a Gulf state may establish a state management program that provides flexibility in the recreational management of Red Snapper for the state’s private anglers. In recent years, the recreational fishing season for Red Snapper in Gulf of Mexico federal waters became progressively shorter despite regular increases in the recreational ACL. In response, recreational anglers asked for greater flexibility in the management of the recreational harvest of Red Snapper, including setting the fishing season. Amendment 50 to the GMFMC’s reef fish FMP establishes the structure through which a Gulf state may establish a state management program that provides flexibility in the recreational management of Red Snapper for the state’s private anglers (see Figure 5.2).

Giving states the flexibility to establish customized measures for managing their portion of the Red Snapper private recreational fishery has resulted in social and economic benefits, as it is assumed that each state provides fishing opportunities preferred by anglers landing Red Snapper in that state. Management measures under a state’s approved state management program must achieve the same conservation goals as those of the current federal management measures (e.g., constrain harvest to the state’s allocated portion of the recreational-sector ACL, and rebuild the Red Snapper stock). Nevertheless, under state management, Red Snapper remains a federally managed species. The GMFMC and NOAA Fisheries continue to oversee management of the stock in federal waters. This includes continuing to comply with the MSA’s mandate to ensure that the recreational sector’s Red Snapper stock ACL is not exceeded and that conservation objectives are achieved. The Council’s Scientific and Statistical Committee continues to determine the acceptable biological

SOURCE: Final Amendment 50A to the Fishery Management Plan for the Reef Fish Resources of the Gulf of Mexico Including Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement, Fishery Impact Statement, Regulatory Impact Review, and Regulatory Flexibility Act Analysis (May 2019).

catch (ABC) for Red Snapper, while the Council determines the total recreational-sector ACL that is allocated among the states and the different recreational fisheries sector components.

Conceptually, adoption of a flexible management system like that provided by an approach such as conservation equivalency makes sense. When considering geographically distributed fisheries like those managed by most Councils, at least some stocks will show a fair degree of state-to-state variability in fish size, abundance, or availability. Consequently, groups of anglers in different parts of the range are likely to have different fishing experiences. However, the disadvantage is that if broadly implemented by Councils, conservation equivalency could generate a patchwork of fisheries regulations for each Council-managed stock, greatly increasing the complexity and inconsistency of regulations. For example, the GMFMC’s Amendment 50 actually consists of six amendments: Amendment 50A consists of actions affecting all Gulf states and the overall federal management of Red Snapper, regardless of whether all states have a state management program, but in addition to Amendment 50A, each Gulf state has its own amendment (Amendments 50B–50F), consisting of

management actions applicable to that state. A central assumption is that social benefits have been gained by allowing greater regional flexibility in the recreational harvest of Red Snapper because management measures are established in a way that better matches the preferences of local constituents. However, constraining landings to a greater number of smaller ACLs is more complex and could increase the likelihood of triggering a post-season overage adjustment.

Implementation of conservation equivalency can be problematic for other reasons. For example, by its very nature (i.e., the application of fisheries management at smaller spatial and temporal scales), this approach ends up having to rely on low-precision recreational fisheries estimates and inaccurate catch forecasting. Likewise, the difference between the current population structure (i.e., observed in real time) and the realized size or age composition induced by long-term adherence to the proposed regulations can be problematic. The perceived benefits (or “credits”) are typically based on the long-term patterns rather than the transitional effects or influences of variable year classes. Finally, problems can arise when conservation equivalency measures are derived independently for different species commonly caught together. Adjustments for individual species may ignore the consequences of a misalignment of measures for species caught by the same group of anglers. For example, fishing rigs set up to catch Black Sea Bass are likely to also catch Summer Flounder. However, if these species have different seasonal patterns of occurrence in the same area, overall discards could increase and diminish perceived conservation measures.

Permits, Endorsements, and Stamps

This approach is based on adopting recreational fishing license registration measures (add-on permits, license endorsements, or stamps) to better define the universe of private anglers targeting Council-managed species, thereby providing improved sampling frames for recreational fisheries surveys. Although strictly speaking, development of a registry of offshore anglers targeting Council-managed species does not constitute a management approach per se, the use of this method is focused on addressing two main management issues: (1) the high uncertainty in MRIP data observed for federally managed stocks and (2) development of a framework for implementation of specialized MRIP-supplemental surveys for Council-managed recreational fisheries.

There is general agreement that fishery scientists and managers face significant statistical limitations to their understanding of recreational impacts on federally managed species. One reason for these challenges is that saltwater recreational fishing licenses have not traditionally distinguished between anglers that fish inshore and/or offshore in federal waters. This limitation can make it more difficult to sample anglers accurately about their fishing activities, including the number of trips taken, fish discarded, and fish kept in federal waters. This higher level of uncertainty could cause catch limits to be set at unnecessarily low levels, thereby denying anglers sustainable access to the resource, or at unnecessarily high levels, thereby diminishing the long-term sustainability of the resource. Therefore, the need for spatial differentiation of recreational fisheries data (i.e., identifying the subset of recreational anglers targeting offshore, Council-managed species) has become an increasingly relevant topic in discussions of how to address uncertainties in determining sustainable fishing limits, as well as when dealing with multisector allocations in fisheries under multijurisdictional management (MAFAC, 2020).

The need for such an effort has been discussed by a variety of organizations interested in improving management of federally managed fisheries. One of the early calls to action in this regard came from the first of five GSMFC–NOAA Fisheries workshops on Red Snapper held in 2013. The report from that workshop (Opsomer et al., 2013) recognizes the need to better identify the universe of Red Snapper anglers as a required first step regardless of the survey method adopted by Gulf states:

If participation in the Red Snapper fishery could be made permit-based, it would then be possible to design a targeted survey similar to the Large Pelagics Survey (LPS) along the Atlantic Coast. A sample of site-days would be selected for Red Snapper angler intercepts to estimate the Red Snapper catch/trip and obtain fish measurements, based on a sampling frame of fishing sites and time periods that encompass the Red Snapper fishing activity. The effort would then be estimated based on a survey of permit holders, both charter boat owners and individual anglers, using telephone or other modes as appropriate.

More recently, concerns raised by a number of recreational angler organizations, scientists, and managers regarding this issue prompted the Marine Fisheries Advisory Committee (MAFAC)3 to examine whether there is an effective way to identify more precisely the universe of recreational anglers fishing in federal waters. The Gulf of Mexico recreational Red Snapper fishery was chosen as a case study for best practices (Chapter 3 describes Red Snapper surveys implemented by each Gulf state). However, the MAFAC study report (MAFAC, 2020) anticipates that results and recommendations are applicable to other coasts as well as other recreational fisheries. Key findings in the report include the following:

- There is broad consensus among fishery managers and scientists that there is value in better defining the universe of anglers that harvest and discard fish in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), and that may be a significant subset of the total population of saltwater license holders.

- Using the Gulf states as a case study, it appears that understanding the number of offshore anglers can be achieved through multiple approaches with varying levels of success:

- using a direct, mandatory permit (free or fee-based) similar to those implemented by ° Alabama, Florida, and Louisiana; or

- through a per–fishing trip system, such as that being used by Mississippi in requiring ° its offshore anglers to hail out before fishing for Red Snapper.

- Each of the programs using a formal or de facto permit was found to (1) provide more efficient targeting of surveys, or the development of future specialized surveys, as in Alabama’s case; (2) reduce the uncertainty of data; and (3) facilitate improved transparency and communication with anglers that appears to have helped build confidence within that community. Under the fee-based version, benefits also included new funding streams to administer improvements to state data collection programs.

- To account for oversubscription rates in their systems, Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi all require an additional, separate step, such as an opt-in requirement. Concerns with the public burden of a separate step were minimized with communication and soft rollout in the first few years. Florida uses a statistical adjustment correction factor to address oversubscription.

- A single survey instrument4 combined with a uniform sampling frame of the anglers fishing offshore can provide more consistent data across jurisdictions that are co-managing fisheries (such as a regional grouping of states or between a state and the federal

___________________

3 The MAFAC is a federal advisory committee that advises the secretary of commerce on living marine resource matters under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of Commerce, primarily NOAA Fisheries. Comprising members from a diverse set of perspectives—including commercial, recreational, aquaculture, environmental, academic, state, tribal, seafood, and consumer fisheries interest groups—the committee has the unique role of working together across all of these sectors to make consensus-based recommendations to NOAA Fisheries.

4 The term “survey instrument” is used to refer to the survey questionnaires that serve as the primary source of information on a given survey respondent. Traditionally, the primary variables found within the main dataset are derived directly from one or more survey instruments.

- Significant differences in the estimates of catch for Red Snapper exist between the state and federal surveys; thus a more consistent survey method utilizing a transparent list of potential participants could be beneficial (MAFAC, 2020).

government), thereby minimizing potential conflicts and improving trust levels among stakeholders.

Finally, the MAFAC report provides the following recommendation:

NOAA Fisheries should invite key state and regional Council fishery managers to evaluate the need for and potential benefits, if any, of layering in an offshore recreational permit to narrow the universe of anglers on a region-by-region basis. This novel approach will require additional scoping by NOAA Fisheries, in consultation with the states and Councils, to identify a comprehensive list of best practices that could help standardize data collection across multiple state jurisdictions to improve management and conservation. Some regions may prefer a standardized permit administered by NOAA. Other regions may prefer to implement a state-based system as in the Gulf. Some regions may prefer a permutation of the two, and some may not want to change their existing data collection. Taking regional needs and preferences into account will likely yield the highest opportunity for aggregate improvement. At the conclusion of this evaluation process, should NOAA find a need to proceed with a federal recreational offshore permit, the Secretary of Commerce should request Congressional authority for the agency to implement such a permit. NOAA’s current authority to compel a federal recreational fishing registration is limited to anglers fishing in the EEZ and for anadromous or HMS species. Implementation on the ground could take many forms, ranging from a centralized approach (similar to the implementation of the current federal migratory bird stamp or “duck stamp”) to a decentralized approach that sets minimum standards as part of a Memorandum of Agreement such as the MOU currently in use under the National Saltwater Angler Registry. (MAFAC, 2020)

The committee recommends further evaluation of this type of approach as a way to survey more effectively the subset of recreational anglers targeting offshore, Council-managed species. As a matter of fact, some Councils have already shown interest in adopting recreational fishing permits or endorsements that follow this basic model. For example, in response to input from stakeholders during development of its 2016–2020 Vision Blueprint for the Snapper Grouper Fishery in the South Atlantic (SAFMC, 2015), the SAFMC has been formally considering implementation of reef fish permits, stamps, or endorsements, initially under Amendment 43 to the Snapper-Grouper FMP and subsequently under Amendment 46. Although the Council has paused development of this FMP amendment because of ongoing discussions by the GMFMC and SAFMC Joint Workgroup on Section 102 of the MFA, the workgroup is in the process of discussing the development of state-administered data collection and permitting programs for private recreational Snapper-Grouper fisheries. Another example of the interest in using this approach for Council-managed species is the MAFMC’s adoption of a private recreational permit for Golden and Blueline Tilefish via Amendment 6 to the Tilefish FMP. Despite increasing popularity as targets for a subset of anglers, both Golden and Blueline Tilefish are species not commonly intercepted by MRIP because of the specialized nature (e.g., deepwater, far offshore) of the trips. The permit requires private recreational vessels that intend to target Golden or Blueline Tilefish north of the Virginia/North Carolina border to obtain a federal private recreational Tilefish vessel permit through an online application on the Greater Atlantic Regional Office website. Furthermore, it requires private recreational Tilefish vessels to fill out and submit an electronic vessel trip report within 24 hours of returning to port for trips on which Tilefish were targeted and/or retained.

It is important, however, to emphasize that to a large degree, successful implementation of this approach (i.e., use of specialized MRIP-supplemental surveys to improve the quality and timeli-

ness of recreational fisheries data for Council-managed species) relies on proper planning and good coordination with the MRIP Regional Implementation Team and all of its component partners in the region: the Interstate Fisheries Commission, the Fishery Management Council, and states in the region, as well as NOAA Fisheries (representatives from MRIP, the Regional Science Center, and the Regional Office). As indicated in Chapter 2, fisheries stock assessments are conducted at the unit stock level, and management benchmarks are estimated at that geographic scale. Consequently, for Council-managed species, the geographic scope for assessment and management occurs at the broad, regional scale, not on a state-by-state basis. Even in such cases as Gulf Red Snapper in which, through Amendment 50 to the reef fish FMP, individual states received delegated authority to manage their portion of the private recreational fisheries, management measures under a state’s approved state management program must achieve the same conservation goals as those of the current federal management measures (i.e., constrain harvest to the state’s allocated portion of the recreational-sector ACL and continue contributing to rebuilding the regionwide Red Snapper stock). In other words, even under the state management program provided by Amendment 50, Red Snapper remains a federally managed species. If this same principle is applied to other Council-managed species, it is clear that implementation of supplemental recreational fisheries surveys solely at the state level and not closely coordinated with the full suite of regional partners (i.e., state-specific surveys that are not fully compatible across the region) is likely to create difficulties for regional, Council-based assessment and management.

This is not a new conclusion. Two previous National Academies studies focused on the Marine Recreational Fishery Statistical Survey (MRFSS)/MRIP (NASEM, 2017; NRC, 2006) identified the need for a higher level of multiagency, interjurisdictional coordination in the development and implementation of recreational fisheries surveys. The 2006 study explicitly makes the following recommendation:

A much greater degree of standardization among state surveys, and between state surveys and the central MRFSS, should be achieved. This will require a much greater degree of cooperation and coordination among the managers of the various surveys.

The committee emphasizes this point here once again and stresses that, when focused on regional or Council-managed species, development and implementation of MRIP-supplemental surveys needs to be accomplished in close coordination with the Interstate Fisheries Commissions, NOAA Fisheries, and other members of the MRIP Regional Implementation Teams.

HOW CURRENT MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES COULD BE MODIFIED TO ALIGN BETTER WITH EXISTING SURVEYS OR SUGGESTED IMPROVEMENTS

Generalized Carryover of Recreational Catches

The need for timeliness of recreational catch information is driven in large part by the fact that ACLs are set and monitored on a strictly annual basis. If the ACL is not met, part of the allowable catch is forgone, at least in the short term (until a new stock assessment accounts for the fish left in the sea and their reproductive contributions). If the ACL is exceeded, AMs may force payback to occur more immediately, in the following year. These asymmetric, short-term consequences result in a high value being placed on meeting the ACL exactly every year. A simple and inexpensive solution to this problem may be the introduction of carry-over provisions, allowing ACL underages to be carried over and added to or subtracted from the following year’s ACL. Such carry-over provisions have been allowed since the revision of NS 1 guidelines in 2016 (81 Federal Register

71858, October 18, 2016). The guidelines specify that carryover is allowed as long as overfishing is prevented every year (i.e., the ACL, including carryover, remains below the overfishing limit [OFL]). Such carry-over provisions must be integrated into the Council’s ABC control rule. In applying carryover, Councils should consider the likely reason for underages. Underages likely caused by management uncertainty (e.g., closing the season too early) are appropriate to carry over, whereas underages likely caused by poor stock condition are less so. Simulation studies show that in the long term, carryover within the rules set by the revised NS 1 guidelines tends to increase the yield of the fishery, but also increases the risk of overfishing and low stock size and the interannual variability of catches (Wiedenmann and Holland, 2020). Risks of adverse outcomes increase with the amount of carryover allowed. Capping the allowable carryover, for example at 15 percent of the OFL could be considered to keep these risks low. Risks can also be reduced by carrying over both underages and overages (generalized carryover). Without this generalization, AMs require payback of overages only when a fishery has been determined to be overfished.

Carry-over provisions have been implemented or considered for multiple fisheries (Holland et al., 2020). However, the potential for such provisions to address the specific management issues resulting from data limitations for in-season management of recreational fisheries has not been systematically explored. In their simplest form, carry-over provisions do not require modifications to catch monitoring or stock assessment procedures and can therefore be implemented with minimal effort and cost. It is likely that more sophisticated carry-over procedures can be developed in conjunction with a new interim assessment, thereby updating stock abundance and catch information simultaneously and reducing subjectivity in the assessment of underlying reasons for underages.

Both the SAFMC and the GMFMC have explored carry-over provisions in fisheries with significant recreational components. Prior to the October 2016 publication of the revisions to the NS 1 guidelines that provided for carryover of unused quota, the SAFMC considered options for implementing carryover of unused ACL by a sector from the current year to the subsequent year in both the Dolphin and Yellowtail Snapper fisheries.5 While the Council initially structured the carryover or “unused ACL credit” actions to be applicable to either sector, early closures of the commercial sector of both fisheries in 2015 (due to the sector ACL’s being met) prompted their development. At the time, the recreational sector of each fishery had substantially underharvested its respective ACL for at least the previous 10 years. The carry-over actions were originally developed with multiple conditions for use (e.g., a cap on the proportion of unused sector ACL to be carried over in a single year, a threshold proportion of the total ACL remaining unharvested, a maximum cap on the ACL “credit” that could accrue to a sector). Subsequently, they were simplified to allow carryover of a specific proportion of the sector ACL to the next fishing year only, and moved into a Comprehensive ABC Control Rule Amendment to address the use of carry-over and phase-in provisions across all of the Council’s fisheries.6 Development of the amendment was paused pending publication of NOAA Fisheries’ guidance on the use of carry-over and phase-in provisions. In December 2020, the SAFMC resumed consideration of the amendment, and it plans to address carry-over provisions and other ABC control rule modifications during 2021.7

___________________

5 SAFMC Meeting September 2016 Briefing Materials, Tab 8, Attachment 4, Dolphin Wahoo Amendment 10 Snapper Grouper Amendment 44 Scoping Document: https://safmc.net/download/Briefing%20Book%20September%202016/TAB%20008_Jt%20Dolphin%20Wahoo%20Snapper%20Grouper%20Mackerel%20Cobia/JtDW-SG-MC_A3_DW10-%20SG44ScopingDocument071516.pdf.

6 SAFMC Meeting June 2017 Briefing Materials. Tab 10, Attachment 11: https://safmc.net/download/Briefing%20Book%20Jun%202017/10%20Snapper%20Grouper/A11_SG_ABCBackgroundDoc_062017.pdf.

7 SAFMC Meeting March 2019 Briefing Materials. Final Committee Reports, Council Session II: https://safmc.net/download/BB%20Council%20Meeting%20Dec%202020/Committee%20Reports%20FINAL/CouncilSessionII_FINALReport_12_2020.pdf.

Similarly, the GMFMC developed a comprehensive amendment in 2018 to address carry-over provisions across FMPs,8 but paused development in 2019 to consider other approaches, such as interim assessment analyses, that might offer a more efficient alternative.9 Both the SAFMC and the GMFMC amendments include comparable actions to establish criteria for the use of carryover, as well as limits on the amount of unused ACL or ABC that could be carried forward. The committee believes that further evaluation of such approaches is warranted, which could allow the recreational sector to achieve a high level of ACL utilization while reducing risks of extreme overages and subsequent payback in a way that would be both practical and cost-effective. It is noteworthy that, while there are many examples of carryover in U.S. commercial fisheries, there are no existing examples of carry-over provisions in U.S. recreational fisheries.

Carry-over provisions are often viewed primarily as a means of achieving a high level of ACL utilization. As such, carry-over provisions could exacerbate year-to-year variation in recreational season lengths or bag limits. However, it is also conceivable that carryover could be used to smooth out interannual variation while allowing a higher level of utilization than could be achieved with constant seasons and no carryover (in which case season lengths would have to be set conservatively to avoid overages). Stability of regulations is frequently mentioned as a goal by stakeholders, and should be considered in the design of carry-over provisions for the recreational sector.

Other options that have been considered by Councils to address optimal use of ACLs have included a “common pool” quota accessible to either sector, as well as conditional, temporary transfers of unused ACL between sectors. The SAFMC contemplated both approaches for the Dolphin fishery, while the GMFMC examined conditional transfers of unused ACL for the Gulf migratory stock of King Mackerel.10 The MAFAC has had a long-standing conditional ACL transfer provision in its Bluefish FMP since 2000. This allows for a transfer of quota to the commercial sector (above its 17 percent sector allocation) should harvest projections indicate that the recreational sector will not achieve its harvest limit. A transfer cap is imposed, such that the commercial sector’s total allowable landings may not exceed 10.5 million pounds, which is the average of commercial landings during the period 1990–1997. Evaluation of whether a transfer is warranted occurs during the annual specifications process. This provision is currently being reviewed in the Council’s Bluefish Allocation and Rebuilding Amendment and includes an option to allow bidirectional transfers (i.e., from the commercial sector to the recreational sector and vice versa).11 Many recreational stakeholders do not support the current unidirectional transfer provision and have expressed concerns regarding its impact on the abundance of fish available to the recreational sector. While cross-sector transfer provisions have the potential to assist either sector in achieving fishery objectives, and could possibly offset management uncertainty associated with the implementation of recreational management measures (i.e., whether or not such measures have the intended impact on harvest), the committee favors the development and/or consideration of criteria for when transfers are advisable.

___________________

8 GMFMC Amendments on Hold, Comprehensive Generic Amendment on Carryover Provisions and Framework Modifications: https://gulfcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/E-6a-Draft-Generic-Amendment-for-Quota-Carryover-and-Framework-Modification.pdf.

9 GMFMC June 2019 Meeting Motions Report: https://gulfCouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/Full-Council-Motions-Report_June-2019_Final.pdf.

10 The SAFMC developed actions in Dolphin Wahoo Amendment 10 to allow transfer of unused ACL between either sector (see March 2017 Briefing Materials, Tab 6, Attachment 2), while the GMFMC considered a unidirectional transfer from the recreational King Mackerel sector to the commercial sector (see August 2016 Briefing Materials, Tab C, Attachment 4a: Allocation Sharing and Accountability Measures for the Gulf Migratory Group of King Mackerel: https://gulfCouncil.org/Council_meetings/BriefingMaterials/BB-08-2016/C%20-%204(a)%20%20Options%20Paper%20-%20CMP%20Amendment%2029%20072516%20-%20Stock%20Version.pdf).

11 MAFMC Meeting February 2021 Briefing Materials. Tab 4, Bluefish Allocation and Rebuilding Amendment Public Hearing Draft: https://www.mafmc.org/s/Tab04_Bluefish-Amendment_2021-02.pdf.

Modifications to Recreational Accountability Measures

Depending on the fishery, the uncertainty and time lag associated with MRIP estimates can make implementation of AMs, particularly in-season AMs (e.g., closure when the recreational ACL is met or projected to be met, adjustments to bag limits, area closures), challenging. High PSEs may lead to early in-season closures or unnecessary triggering of post-season measures (e.g., application of restrictive management measures the following season or overage paybacks). Conversely, high PSEs may also result in failure to apply AMs (whether in season or postseason) when needed to ensure that recreational harvest remains at sustainable levels. Additionally, the release of MRIP harvest estimates 45 days after the end of a 2-month wave may lead to in-season closures that occur well after an ACL has been met or exceeded. In either case, recreational fishing opportunities may be negatively impacted, with anglers feeling as though they are being unnecessarily punished for the perceived shortcomings of both data collection and management. In some instances, geographic differences in species seasonality may result in greater adverse impacts to fishing opportunities in one part of a region compared with another. While the NS 1 guidelines recommend the use of in-season AMs “whenever possible,” they provide a range of examples beyond an in-season fishery closure, and recommend the use of an annual catch target (ACT) (a level of catch set below the ACL) for fisheries without in-season AMs. However, the guidelines contain no specific provisions with respect to the appropriateness of certain approaches for either recreational or commercial fisheries.

Recreational fisheries managed by the New England Fishery Management Council (NEFMC) and the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council (MAFMC) do not have in-season AMs (i.e., fishery closures or other adjustments) for the reasons noted above, in addition to the seasonal nature of their fisheries. Instead, both Councils use proactive AMs in which recreational measures are evaluated prior to the upcoming fishing season to determine whether adjustments are necessary to ensure that recreational ACLs are not exceeded. Additionally, both Councils apply reactive (post-season) AMs in which recreational catch is compared with the recreational ACL; if the ACL has been exceeded, adjustments are made to prevent an overage from occurring in the subsequent season. For recreational Groundfish fisheries in New England, a 3-year moving average of recreational harvest is compared with the 3-year average of the recreational sub-ACL to determine whether reactive AMs need to be applied.12 These may include modifications to the season length, size limit, and/or bag limit, but there are no paybacks of recreational ACL overages. This approach relies on past fishery performance being representative of future harvest, which can be impacted by such external factors as fish availability.

Since 2013, a bioeconomic model developed by the Northeast Fisheries Science Center has been used annually to set recreational measures. The model takes into account how changes in management measures may impact recreational fishing effort, angler welfare, fishing mortality, and stock levels (Gulf of Maine Cod and Haddock only), although it is constrained by uncertainties associated with data inputs (e.g., preliminary MRIP data and terminal year stock assessment information). Broadly, the economic subcomponent is a recreational demand model that was parameterized using a choice experiment survey administered via MRIP (Lee et al., 2017). It accounts for changes in recreational effort based on trip cost and duration, as well as participation choices that vary according to angler expectations of landings and discards. This is linked to a biological submodel that incorporates stock dynamics (based on the peer-reviewed population assessment), but has been modified to run on a bi-monthly time step that matches the 2-month periodicity of an MRIP wave. The biological submodel also converts fish ages from the stock assessment model to fish lengths. This allows for modeling of the impacts of length-based regulations, as well as angler selectivity and targeting. While model projections have been mixed with respect to under- or over-

___________________

12 NEFMC Amendment 16 to the Multispecies FMP: https://www.nefmc.org/library/amendment-16.

predicting harvests, the model is a tool that incorporates empirically derived relationships among angler effort, stock size, and management measures.

For recreational fisheries managed by the MAFMC, a post-season process similar to that in New England is used to determine whether reactive AMs are necessary. A 3-year moving average of recreational catch is compared with the 3-year average of the recreational ACL to determine whether an overage has occurred and whether adjustments to recreational management measures are needed. However, the reactive or post-season AMs in the Mid-Atlantic do include provisions for payback of recreational overages only in certain circumstances that are tied to stock status (e.g., whether a stock is overfished) and biomass level. In such instances, the payback is not a strict pound-for-pound payback, but it is scaled to the condition of the stock. These post-season, reactive AMs were implemented in 2013 through the MAFMC’s Omnibus Recreational Accountability Amendment, which also removed in-season closure authority for recreational fisheries.13 While a bioeconomic model has not been developed and/or applied to the MAFMC’s recreational fisheries, the Council has supported the development of several management strategy evaluations (MSEs) for the recreational Summer Flounder fishery to address trade-offs and impacts of different suites of recreational management measures (see the section on MSE development later in this chapter).

The SAFMC began development of an amendment in 2018 to review and revise the recreational AMs in its Snapper-Grouper and Dolphin-Wahoo FMPs. The purpose was to address uncertainties in MRIP data, improve stability, and allow more flexibility in the management of recreational fisheries. The amendment was revised to address only the recreational Snapper-Grouper fishery and was paused in December 2019 because of concerns regarding the impact of revised MRIP estimates on allocations and existing ACLs.14 Most of the 55 species in the Snapper-Grouper FMP have never been assessed, and ACLs for those species have been set using landings-based and other data-limited approaches. This limits the ability to establish consistent AMs that are tied to stock status across all species. While the majority of species in the FMP have in-season closures, several have extremely low recreational ACLs and/or short seasons that make implementation of in-season AMs challenging. For many others, MRIP estimates are very imprecise, even at the annual level, and low intercepts of trips harvesting Snapper-Grouper (typically offshore) tend to turn these into rare-event species. Since 2016, only eight in-season AMs (i.e., closures) have been applied to Snapper-Grouper species. However, several of these closures have not been implemented until December because of the timing of MRIP estimates, while the ACLs were met in July–August (and subsequently exceeded).15 The SAFMC amendment examines the possible removal of recreational in-season closures for species with consistently high PSEs across a range of thresholds.

Similar to the NEFMC and the MAFMC, the SAFMC is also considering post-season AM triggers that would attempt to address the uncertainty in estimates of recreational harvest. These include, among others, a 3-year moving geometric mean of recreational harvest exceeding the recreational ACL, a 3-year sum of recreational harvest exceeding the 3-year sum of recreational ACLs, recreational harvest exceeding the recreational ACL in 2 out of 3 years, and total (commercial plus recreational) harvest exceeding the total ACL, among others. Should a trigger be reached, post-season AMs that could be implemented include adjustments to season length and payback of overages. The SAFMC reviewed the amendment in November 2020 and declined to take further action at that time because of ongoing discussion of recreational AMs by the GMFMC and the

___________________

13 MAFMC Omnibus Recreational Accountability Amendment: https://www.mafmc.org/actions/omnibus-recreational.

14 SAFMC Snapper Grouper Regulatory Amendment 31 (Recreational Accountability Measure Modifications): https://safmc.net/download/BB%20RecTopics%20Council%20Meeting%20Nov2020/A2a_Rec%20Topics_SG%20Reg%2031%20DD_Dec%202019.pdf.

15 John Carmichael, SAFMC Executive Director. Committee presentation, September 8–9, 2020.

SAFMC Joint Workgroup on Section 102 of the Modernizing Recreational Fisheries Management Act of 2018, or Modern Fish Act (MFA), which may inform future options.16

In contrast to the U.S. East Coast Councils, the primary AM for recreational fisheries under Pacific Fishery Management Council (PFMC) management is the extensive in-season monitoring conducted by the states.17 This is used to adjust management measures to maintain harvest within established limits. If necessary, AMs may also include in-season closures. It should be noted that the states expend significant resources to monitor these fisheries, and that recreational effort (angler trips) in the Pacific region is two orders of magnitude less than that in the Atlantic region (New England, Mid-Atlantic, South Atlantic). Similarly, the State of Alaska also conducts in-season monitoring and management of most recreational fisheries (with the exception of Pacific Halibut, which is shared with NOAA Fisheries and the International Pacific Halibut Commission).

In conclusion, the committee acknowledges the challenges associated with the development and application of AMs in large recreational fisheries given the precision and timing of MRIP estimates. Exploration of such tools as bioeconomic models and consideration of multiyear approaches as highlighted above could minimize the need for in-season AMs or enable refined application of post-season AMs, and could mitigate uncertainty. NOAA Fisheries also would be well advised to review the National Standard 1 guidelines to ensure that agency guidance with respect to recreational AMs, particularly the use of in-season AMs, aligns with the timeliness and precision of harvest estimates produced by MRIP.

Voluntary Catch Reporting by Anglers

In most marine fisheries, recreational anglers do not report their catches or related information unless they are approached as part of a survey. However, there has been substantial interest in recent years in encouraging voluntary angler data programs or in some cases, mandatory reporting schemes. Voluntary reporting in particular has been widely suggested as a way of supplementing or even replacing survey-based data collection programs. The aims of such programs may include (1) obtaining more data, better data, or data that are impractical to obtain in other ways; (2) engaging stakeholders in decision making, education, and trust building; and (3) potentially reducing the effort and cost of data collection.

There is a great diversity of such voluntary programs, described by such terms as “angler apps,” “citizen science,” and “voluntary angler data.” To assess the potential of a particular program, it is important to understand its characteristics in multiple dimensions, including objectives, types of data collected, reporting technology, sampling design, data analysis, and dissemination and use of the information generated. As mentioned above, most voluntary programs have multiple objectives involving collecting various types of data as well as engaging and possibly educating stakeholders. The latter is addressed below in the section on managing for angler satisfaction. Voluntary data programs involving anglers may aim to gather information on, for example, species occurrence; catches; fishing effort; catch per unit of effort (CPUE); discards; size composition of catches and discards; fishing gear use; fish handling, including use of barotrauma mitigation; or observations or perceptions of stock abundance trends. In terms of reporting technology, options include traditional paper-based forms and logbooks, web portals, and smartphone apps.

Apps have received particular attention because of their potential to facilitate two-way information flow; near-real-time data entry; and integration of information about anglers, trips, effort, and catch on a single platform (Venturelli et al., 2017). However, other reporting options, such as

___________________

16 SAFMC November 2020 Meeting Transcript: https://safmc.net/download/FullCouncilMin_Nov20RecTopics.pdf.

17 See PFMC Groundfish Amendment 23. See https://www.pcouncil.org/documents/2010/09/Groundfish-fmp-amendment-23-environmental-assessment.pdf.

web portals, remain important and may in fact be preferred by participants because use of apps on the water can distract from the fishing activity (Crandall et al., 2018). Possible sampling designs include entirely voluntary reporting, universal mandatory reporting to create a census, or survey sampling approaches whereby representative samples of participants are surveyed. In some cases, such as the Mississippi Tails n’ Scales or the Alabama Snapper Check programs, voluntary reporting has been expanded and eventually made mandatory for an increasing number of species. Analysis of data collected from angler reporting often uses approaches similar to those used for survey data. However, additional considerations and novel analyses may be necessary to address biases that may arise from the selective nature of voluntary reporting, particularly if participation is low (implying high potential for bias). Collecting data to describe such characteristics of volunteers as motivation, skill, and behavior is important to understand and quantify biases. Voluntary reporting and citizen science programs often place great emphasis on disseminating data publicly as a way of maintaining participation and serving broader education and engagement objectives.

Fisheries data provided by voluntary reporting have proven highly informative in some cases; for example, data on the occurrence of “unusual” species have been used to track climate-related changes in species ranges (Pecl et al., 2019), while data on the size composition of discards have proven important to some stock assessments, such as the Snook stock assessment conducted by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC). Catch and effort data collected using voluntary angler data programs have been shown to yield CPUE estimates consistent with those obtained from such surveys as MRIP (Jiorle et al., 2016). However, as a result of low participation in voluntary catch-effort reporting, such data have not meaningfully augmented or replaced large-scale surveys to date. A variety of approaches have been established for addressing data quality issues in citizen science programs, including voluntary angler data programs (Bird et al., 2014; McKinley et al., 2017). Skills requirements for basic catch reporting are relatively moderate, but participants still need to be able to identify common species, conduct any size measurements that may be requested, and understand the importance of reporting trips on which no fish were caught. Often, participants have a wide range of skill levels (sustained participants may be skilled amateurs), and citizen science programs have found that accounting for assessed or self-assessed skill levels in analyses can improve data quality.

The greatest, fundamental challenge with voluntary angler data programs is their almost universally low participation (and even lower sustained participation). The long-running Florida FWC Snook Logbooks program had 122 participants overall, of whom about 30 participated in any one year between 2002 and 2014. The Angler Action program had 600 participating anglers between 2012 and 2016, but fewer than 10 major contributors (Crandall et al., 2018). The Texas iSnapper program had 95 anglers reporting a total of 163 trips in the 2015 Red Snapper season. Despite low participation, the Snook Logbook and Angler Action programs produced important information on the size composition of snook discards that was used in the snook stock assessments, illustrating that even limited voluntary reporting can be useful if it provides crucial information that is difficult to obtain in other ways. On the other hand, as mentioned above, low participation in voluntary catch-effort reporting means that such data are unlikely to substantially augment, let alone replace large-scale catch-effort surveys. In addition to limiting the precision of estimates, very low levels of reporting imply a very high potential for bias. Low participation has been a near-universal challenge for voluntary angler data programs despite substantial efforts to recruit and retain participants. Reasons for low participation include that most anglers are likely to be driven by motivations other than observing and recording data, and many are positively reluctant to share information on their fishing spots or catch rates. Of course, some anglers do like to record and share data for the sake of science. Crandall et al. (2018) found that sustained participants in a voluntary angler data program had motivations similar to those associated with participants in other citizen science programs.

Even though voluntary data programs use unpaid volunteers, they require substantial efforts and financial investments to recruit, retain, and train volunteers, analyze and report data, etc. They should not therefore be considered low-cost alternatives to more formal surveys or research programs (McKinley et al., 2017). Moreover, many volunteer data programs lack a sampling frame and therefore do not support probability-based estimates of catch and effort. This issue can be addressed in well-designed logbook and other citizen science programs, such as by establishing an angler panel.

Volunteer data and citizen science programs offer multiple opportunities to better engage the public in fisheries management decision making. Such programs can facilitate the bidirectional flow of information. Volunteers, through training and experience, can better understand the ability of science to provide answers. They may also appear at public meetings and provide constructive input and spread information through social networks, helping scientists and managers better understand the perspectives of stakeholders. Volunteer data and citizen science programs therefore can provide benefits far beyond the data collected, and in many cases those broader benefits may in fact be the most important.

Mandatory Catch Reporting by Anglers

Mandatory reporting and integration with other approaches (e.g., dockside intercepts) may alleviate many of the problems associated with voluntary reporting. Such approaches may achieve near-census levels of coverage akin to those achieved in many commercial catch reporting programs. An example of such a program is the Mississippi Tails n’ Scales Red Snapper catch monitoring program. Not only is reporting mandatory, but the survey designs for both charter and private boat fishing consist of two complementary components: an electronic reporting system and a dockside access point intercept survey. Through a capture-recapture survey design, catch and effort information reported electronically by anglers is validated and corrected using information from the dockside intercept survey. While the program benefits from Mississippi’s geography and relatively small recreational fishing sector, similar programs can potentially be effective with lower levels of dockside sampling and enforcement. Further development and testing of such approaches is necessary (e.g., with respect to the coverage of private docks that are unavailable to access point intercepts and can account for a substantial share of fishing activity). With widespread availability of electronic reporting tools, objections to mandatory reporting are often more philosophical than practical. Concerns that some anglers may not have access to such tools, thereby introducing coverage bias, have been voiced but are unlikely to be borne out in federal fisheries that often require substantial investment in boats and equipment from private recreational anglers to participate. However, the committee believes that mandatory catch reporting programs have the potential to improve the accuracy and timeliness of recreational data collection and encourages further exploration of such approaches.

Recreational Reform Initiative

The Recreational Reform Initiative is a joint effort of the MAFMC and the ASMFC to improve management of the recreational fisheries for Summer Flounder, Scup, Black Sea Bass and Bluefish. All four species are jointly managed by the MAFMC and the ASMFC, which requires that both entities jointly approve ACLs and most management strategies, although there may be differences between recreational management measures for state and federal waters. The initiative was launched in 2019 with the following goals: provide stability in management measures (e.g., size limit, bag limit, and season), increase flexibility in the management process, and ensure accessibility to fish-

ery resources that is aligned with availability and stock status. The intent is to develop alternative approaches to working with existing MRIP data while meeting the mandates of the MSA.18

A suite of topics have been identified to address the goals of the initiative, several of which fall within the objective of better incorporating MRIP uncertainty into management. One of these is development of a process for identifying and smoothing outlier MRIP estimates. The ASMFC Summer Flounder, Scup, and Black Sea Bass Technical Committee previously identified two outlier MRIP estimates of Black Sea Bass (2016 New York Wave 6 for all modes and 2017 New Jersey Wave 3 private/rental mode) using a modified Thompson’s tau approach and replaced them with smoothed estimates for use in the development of state waters recreational measures. Generally, nonstatistical methods, such as multiyear averaging, have been used by both the ASMFC’s Technical Committee and the MAFMC’s Monitoring Committee to address uncertainty in MRIP data when trying to project future harvest under various management measures. Development of a standardized approach for identifying and adjusting outliers (both high and low) would be beneficial for setting harvest specifications or evaluating the application of AMs, as noted above.