1

Introduction

In 1976, Congress passed the Fishery Conservation and Management Act, now known as the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (the MSA).1 The MSA establishes a system for regulating fisheries that operate between 3 and 200 nautical miles from U.S. shores. Although it nominally delegated management authority to the Secretary of Commerce and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the MSA gives the bulk of the responsibility for crafting and recommending fishing rules to eight Regional Fishery Management Councils (the Councils). Bluefin tuna and other highly migratory species are managed through the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) of NOAA (also known as NOAA Fisheries) and, ultimately, through the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), to which the United States is a signatory.

Pursuant to the MSA, the Councils are to be primarily composed of officials from state, federal, and tribal governments and citizens knowledgeable about fisheries management (16 U.S.C. § 1852(b)(2)(A)). The Councils’ primary duties include the preparation, monitoring, and revision of Fishery Management Plans (FMPs) for fisheries within their respective geographic jurisdictions.2 The law gives the Councils flexibility to tailor rules that fit individual fisheries, but also mandates that FMPs and other management measures be consistent with ten “national standards.” While these standards generally require that rules are fair to fishers,3 promote safety and efficiency, and ensure the long-term sustainability of fish populations, the first National Standard is particularly specific

___________________

116 U.S.C. § 1801, et seq.

2Defined by the MSA as “one or more stocks of fish which can be treated as a unit for purposes of conservation and management and which are identified on the basis of geographical, scientific, technical, recreational, and economic characteristics.” The MSA, Pub. L. No. 94-265 § 3(7)(A).

3There is considerable debate on whether to use “fishermen” or “fishers” to indicate people who catch fish—for a living, for pleasure, or for subsistence. The term “fisher” is not universally accepted, particularly by women and men in North American fishing industries. However, in academic journals and many government documents, usage of “fishers” has increased in recent decades as a more gender-neutral term, even though in most usages, “fishermen” refers unambiguously to people of any gender who fish (Branch and Kleiber, 2017). Aware of this controversy, the committee opted to use “fishers” in this report.

and quantitative, commanding that policy makers “shall prevent overfishing while achieving … the optimum yield” (The MSA, Pub. L. No. 94-265 § 3(7)(A)).

The first two decades of management under the MSA produced successes in ending overfishing and rebuilding some stocks. They also resulted in some failures. For example, by the early 1990s, a significant percentage of fish populations (or “stocks”) could be characterized as “overfished,” that is, reduced to levels incapable of producing as high a yield as possible over a sustained period of time. In addition, management under the MSA had produced a number of inefficient, “severely overcapitalized” fisheries in which the amount of capital invested by fishers far exceeded the amount needed to catch the fish and maximize profits. From a societal perspective, overcapitalization represents wasted resources; it also makes fishing less profitable for fishers than it otherwise could be.

In response to these and other issues, Congress has twice made major revisions to the MSA (1996 and 2006). In 1996, the reauthorized MSA required overfishing to be ended and stocks rebuilt within a decade, if possible. In 2006, Congress added Section 1853a, entitled Limited Access Privilege Programs. The addition of this section represented the first time that Congress had directly authorized the use of what are more generally known as individual fishing quotas, or IFQs. As discussed more fully throughout this report, Limited Access Privilege Programs (LAPPs) can dramatically alter the economic structure of a fishery, changing incentives in pursuit of better conservation and greater efficiency if appropriately designed and accompanied by effective monitoring and accountability measures.

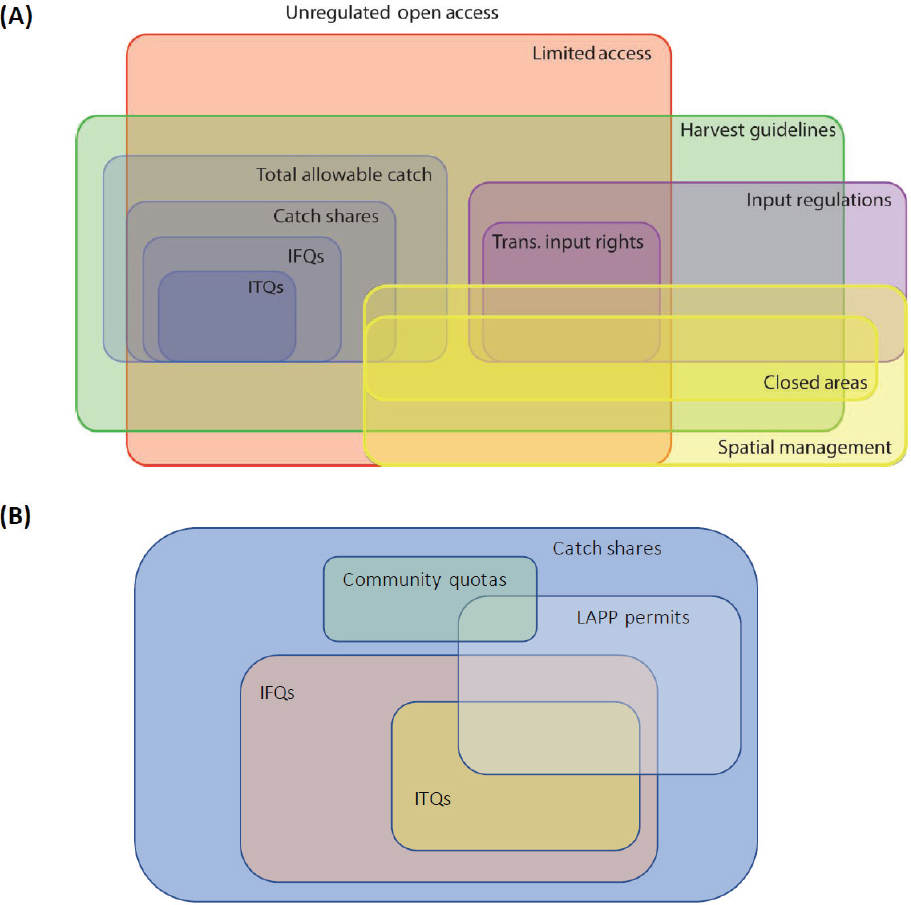

LAPPs are systems of managing fisheries in federal waters whereby participation is limited to only those satisfying certain criteria (often referred to as eligibility criteria; 16 U.S.C. § 1802(27)). They are roughly synonymous with “catch shares” (see Figure 1.1), which represent a major contrast to traditional ways of managing fisheries.4 Permits are issued to harvest a quantity of fish as represented by a portion of the total allowable catch (TAC) that is held for exclusive use by a person in each fishing season or year. While the proportional quota shares held by any one individual do not change over time, any change in seasonal or annual TAC results in differing quantities of quota (often referred to as annual allocation as distinguished from share) that the holders can harvest.

These privileges are often referred to as IFQs when they are held by individual people, businesses, or other distinct entities, and more specifically individual transferable quotas (ITQs) when they are transferable through sale or lease (see Figure 1.1). The cases in this study are all ITQs, but in the United States they are most often called IFQs. The committee uses the terms IFQ and catch shares throughout the report, reserving the term individual bluefin quota (IBQ) for the bluefin tuna bycatch LAPP.

LAPPs represent major structural change, replacing fisheries management systems that are either open access or limited access, where individual fishers work within TAC quotas and other rules that apply to the entire group. LAPPs create a restricted kind of exclusive claim to ownership—not in fish per se, which remain public property, but in the right to take a proportion of a TAC, the size of which is determined by the NMFS and the Councils. Quota shares are fixed but annual allocations vary as the TAC changes. Under the MSA, LAPPs are “privileges” rather than property. They were specifically titled as such to emphasize the conditional nature of the program in general and, by extension, any “rights” granted as a component of the program (16 U.S.C. § 1853(b)). As such, a LAPP can be limited, modified, or revoked at any time. However, if a program has met or is meeting its stated objectives then it will likely remain (16 U.S.C. § 1853a(f)(1)). While the MSA classifies LAPP permits as “not property” for purposes of the Fifth Amendment to the

___________________

4Excluded from LAPPs in the United States are Alaska’s Community Development Quota programs and New England’s Multispecies Groundfish Sector programs.

SOURCE: Anderson et al., 2019. (B) Venn diagram representing the relationship among LAPP permits and other commonly used allocation strategies. The LAPP forms of “community quotas” are LAPPs assigned to fishing communities or to regional fishery associations, as defined and under conditions outlined in the legislation 16 U.S.C. § 1853a(c)(3), (4).

U.S. Constitution, states can and do treat them as property for other purposes, such as divorce or probate proceedings.

The question of how restructuring actually impacts the fishery, including fishing sectors that are not part of a LAPP, but pursue the same species, is the subject of this report. More specifically, the report focuses on impacts in what are known as mixed-use fisheries. As defined in the MSA, mixed-use fisheries are those federal fisheries that consist of two or more of the following sectors: recreational fishing; charter fishing; and commercial fishing (e.g., Figures 1.2 and 1.3).5 In the fisheries of this study, LAPPs are only in the commercial sector although they have been explored for a for-hire sector. There can be other sectors in a mixed-use fishery. The bluefin tuna fishery has several commercial sectors, only some of which are LAPPs. Some mixed-use fisheries have important tribal and subsistence sectors that must be considered. To the committee’s knowledge, there are no tribal or subsistence sectors in the federal fisheries of this study.

Photo credit: Steven Murawski.

___________________

5Congress added this definition in 2018, as part of the Modernizing Recreational Fisheries Management Act (MFA). In addition to legally recognizing the differences between commercial and recreational fishing, the Act added management tools for decision makers to use in federal recreational fisheries and mandated the analysis of tools currently in place. Specifically, the MFA called for a study of Limited Access Privilege Programs (LAPPs) in mixed-use fisheries (Section 103(A) including the red snapper fishery of the Gulf of Mexico).

Photo credit: Steven Murawski.

The Statement of Task is as follows:

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) will convene an ad hoc committee to consider the use of LAPPs in the following mixed-use fisheries: red snapper, and grouper and tilefish, managed by the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council; wreckfish, managed by the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council; golden tilefish, managed by the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council; and bluefin tuna, a highly migratory species managed by the Secretary of Commerce. For each of the LAPPs, the committee will

- Assess the progress in meeting the goals of each relevant LAPP and the goals of the MSA.

- Assess the social, economic, and ecological effects of each relevant LAPP, considering each sector of the relevant fishery and related businesses, coastal fishing communities, and the environment.

- Assess any impacts (positive and negative) to stakeholders in the relevant mixed-use fishery caused by the LAPP.

- Recommend policies to address any negative impacts identified in task 3, considering cost and/or feasibility.

- Identify and recommend the different factors and information that the National Marine Fisheries Service and the Councils should consider when designing, establishing, or maintaining a LAPP in a mixed-use fishery to mitigate impacts to stakeholders to the extent practicable.

- Review best practices and challenges faced in the design and implementation of LAPPs in all Council regions, including those not listed above.

The question is not whether to use LAPPs as a management tool. The questions are instead: What happens to fishers, fishing communities, and ecosystems when the Councils choose to employ LAPPs? And, if LAPPs do produce negative impacts, how might the Councils address those impacts by adjusting LAPP rules?

STUDY METHODOLOGY

This study examines U.S. mixed-use fisheries in which LAPPs have been implemented. LAPPs appear only in the commercial sector of the mixed-use fisheries. For each of these case studies, the committee examined available data on the fisheries and collected testimony from fishery participants, relevant Councils, and NMFS regional experts through a series of public meetings. To provide a context for the data and testimony collected, the committee conducted literature reviews, looking for peer-reviewed studies and reports that have attempted to document or to predict IFQ or LAPP impacts in mixed-use fisheries.

THE FIVE CASE STUDIES OF THE MIXED-USE FISHERIES

The five fisheries in these case studies vary greatly in scope and scale and in the extent to which recreational and for-hire sectors are also involved in the fisheries (see Table 1.1).

The NMFS defines marine recreational fishing as “fishing primarily with hook and line for pleasure, amusement, relaxation, or home consumption. If part or all of the catch was sold, the monetary returns constituted an insignificant part of the person’s income.”6 There are three modes of recreational fishing: from shore, by headboat or charter boat, or by a privately owned or rental boat. For all of the species and fisheries covered in this study, only the latter two modes are applicable. Within the headboat and charter boat sectors, which differ by rental of space for one or rental of the whole boat, issues are similar such that these terms are used interchangeably in this study, or replaced by the more generic term “for hire.” Although private anglers and customers of for-hire boats come from just about anywhere, the recreational fishing sector also supports coastal communities through related business such as marinas and bait and tackle shops in addition to fuel, travel, and lodging for anglers to get to and from their residence to the fishing access site.

The commercial fishing sector for species that are federally managed includes individuals and businesses that harvest marine species for sale, primarily for human consumption. As a business, commercial fishers and their operations are subject to relatively large financial risks compared to businesses that are not similarly reliant on wild and variable natural resources. In addition, due to the historical use of output control measures (such as per trip and aggregate total allowable catches and bag limits) to protect stocks, many also faced heightened physical risks from safety issues at sea during poor weather. In many fisheries, commercial fishing also supports coastal communities through working waterfronts and provision of jobs (on boats or in shoreside processing facili-

___________________

6See https://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/st1/recreational/overview/glossary.html (accessed July 16, 2021). The committee notes that for some fisheries, subsistence and indigenous fishing are also important mixed-uses to consider; however, it has no information on the existence of those sectors for the fisheries of this study.

TABLE 1.1 Characteristics of Limited Access Privilege Programs (LAPPs) in Five Mixed-Use Fisheries

| Distribution of TAC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Year | Management Agency | Species | Type | LAPPs | Recreation | Other | Number of Initial Shareholders | Number of Active Fishing Vessels |

| 1991 | South Atlantic | Wreckfish | ITQ | 95% | 5%a | 6 | 8 permits (2018) | |

| 2007 | Gulf of Mexico | Red snapper | ITQ | 51% | 49%b | 554 | 362 (2011)c | |

| 2009 | Mid-Atlantic | Golden tilefish | ITQ | 95% | 0% | 5%d | 13 | 14 (2009-2013) |

| 2010 | Gulf of Mexico | Grouper-tilefish (G-T) | see belowe | 766 | 731 (2011-2015)f | |||

| G-T Shallow-water Grouper (SWG) | ITQ | 77% | 23% | |||||

| SWG: Red grouper | 76% | 24% | ||||||

| SWG: Gag | 39% | 61% | ||||||

| G-T Deepwater grouper | ITQ | 96.5% | 3.5% | |||||

| G-T Tilefish | ITQ | 99.7% | 0.3% | |||||

| 2015 | NOAA/HMS | Bluefin tuna | IBQ | 8.1%g | 19.7%h | 72.9%i | 136 | 76 (2018) |

NOTES: IBQ = individual bluefin quota (to manage bycatch); ITQ = individual transferable quota; TAC = total allowable catch. Allocations are percentages of the total allowable catch allocated to each sector: LAPP (commercial), recreational (usually includes for hire), and other. Shareholder refers to number of either individual entities or accounts, in most instances at time of initial allocation (exception is wreckfish, 2017). Estimates of active fishing vessels come from various sources and dates and are used as an indicator of relative differences in scale of the fisheries.

a Although wreckfish has a recreational fishing allocation there are few reported recreational catches. SOURCE: Wreckfish LAPP review.

b Red snapper recreational allocation is divided: 57.2% private angler, 42.3% for hire (charter). SOURCE: Jessica Stephen, NMFS, personal communication, 2021.

c Red snapper and grouper-tilefish fishing vessels have significant overlap. SOURCE: Red snapper LAPP review.

d Golden tilefish allocation for incidental catches from permitted commercial vessels. There is no allocation for recreational fishing, which is managed through bag limits at present. SOURCE: Golden tilefish LAPP review.

e In some cases, there is no explicit recreational allocation; it comes from what remains after a commercial allocation is set. Fishing vessels in the grouper-tilefish ITQ program combined with those in the red snapper program (grouper-tilefish review). SOURCE: Mike Travis and Jessica Stephen, NMFS, personal communication, 2021.

f Fishing vessels in the grouper-tilefish ITQ program combined with those in the red snapper program. SOURCE: Grouper-tilefish LAPP review.

g The IBQ program is only for pelagic longliners. Their allocation is often increased by transfer from the Purse Seine sector or a Reserve category. There are limited entry permits for other categories.

h Angling (recreational handgear); private anglers and for-hire vessels may also use the commercial General category in some conditions.

i 57% General (commercial handgear); 18.6% Purse Seine (not active in recent years); 4% Harpoon & Trap; 2.5% Reserve. SOURCE: Bluefin tuna LAPP review.

ties). However, increasing coastal land values have reduced the number of fish houses located in waterfront locations and consolidated some land-based operations over the long term. Within the commercial sector, the financial and physical risks also vary by the assets owned, the portfolio of target species, the extent that the owner is dependent on a given fishery, and whether an operation is individual or corporate owned.

Typically, the recreational, charter, and commercial sectors in a particular fishery each function differently and have unique attributes. For example, recreational anglers may use a variety of both private and public access and landing sites, whereas commercial trips typically begin and end at designated locations. The main economic value inherent in commercial fisheries is the market price for the harvested fish or shellfish. For charter fisheries, the value for the vessel owner is the willingness of customers to pay to fish for enjoyment and/or food; for private recreational anglers, the value lies in the experience and perhaps the food. As another example, commercial fisheries, and increasingly for-hire fisheries, may be subject to heightened reporting requirements as opposed to private recreational anglers.

Perhaps the most fundamental distinction between commercial and recreational sectors is that, for the most part, there are no limits in practice on the number of participants in recreational fisheries, other than purchasing a license to fish. Recreational fisheries are effectively open access. In contrast, many commercial fisheries have limited access, where participation depends on holding a permit, the number of which is limited and which can be very costly. Although for-hire recreational operations may be subject to limited licensing, both their customers and those pursuing marine species on private vessels operate under open access institutions. While legal participation may at times require a license or permit, these are unlimited in quantity and usually sold at a nominal price. In order to constrain recreational harvest, regulators typically rely on the use of seasonal and areal restrictions for targeted fishing as well as retention (bag) and size limits. However, commercial fisheries are increasingly subject to limitations on access that control the number of vessels or other units that may legally participate. These and other distinctions can have implications for management, such that the management strategies for recreational, charter, and commercial sectors vary. As stated in Modernizing Recreational Fisheries Management Act (MFA),

While both provide significant cultural and economic benefits to the Nation, recreational fishing and commercial fishing are different activities. Therefore, science-based conservation and management approaches should be adapted to the characteristics of each sector.7

In considering how to best conserve and manage the fisheries within their geographic regions, the Councils may consider a variety of mechanisms or techniques, including instituting size limits, fishing seasons, bag limits, gear restrictions, area closures, permitting requirements, access limitations, and others. In a mixed-use fishery, these management strategies can be applied to the individual sectors or to all sectors within the fishery to constrain annual removals to no greater than the TAC as allowed to each individual sector.

Table 1.1 shows each of the LAPPs in the mixed-use fisheries of this study, indicating the type of LAPP; when it was established; how the total allowable catch is allocated among the commercial, recreational, and other sectors; and, showing the large difference in the scale of these fisheries, the initial numbers of shareholders and estimates of the numbers of active fishing vessels.

___________________

7MFA, Pub. L. No. 115-405 § 2.

Gulf of Mexico Red Snapper

The red snapper fishery in the Gulf of Mexico has very large commercial, recreational, and for-hire sectors. It is part of a complex set of fisheries for a number of reef fishes (e.g., snappers, groupers, porgy, triggerfishes, etc.). Its LAPP, like most others in this study, is only for the commercial sector. Also like most others, it is an IFQ program with transferability of both quota shares and annual allocations. It is thus technically an ITQ program, but is commonly described as an IFQ, and is so similarly described in this report.8 The program was implemented in 2007 under Amendment 26 of the Reef Fish FMP of the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council. Participants live and work from a large number of ports around the Gulf of Mexico and are often also involved in the grouper-tilefish LAPP.

Gulf of Mexico Grouper-Tilefish

The fishery for a complex of groupers and tilefishes in the Gulf of Mexico also has very large commercial, recreational, and for-hire sectors that overlap extensively with those for the red snapper fishery. Its IFQ program in the commercial fishery began in 2010, under Amendment 29 of the Reef Fish FMP of the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council. Participants live and work from a large number of ports around the Gulf of Mexico.

South Atlantic Wreckfish

The wreckfish commercial fishery IFQ program was one of the first to be created in U.S. federal waters. The program began in 1992, under Amendment 5 of the FMP for the snapper-grouper fishery of the South Atlantic region. It takes place offshore and is highly specialized, with very few participants, working out of a small number of ports. The recreational and for-hire sectors appear to be negligible, although there is a 5% recreational allocation.

Mid-Atlantic Golden Tilefish

The IFQ program for the golden tilefish of the northeast region was created through the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council in 2009, as Amendment 1 of the Tilefish Fishery Management Plan. The fishery is offshore and quite specialized, mainly using longlines. The IFQ program has few participants, 13-14 vessels in recent years, although very large numbers of commercial vessels may be permitted to take a small incidental catch of golden tilefish, for which 5% of the TAC is allocated. While the LAPP vessels primarily work from only two ports in New York and New Jersey, the large incidental catch fishery is more widely spread along the coast. Recreational and for-hire sectors are occasionally involved, most often as part of offshore large pelagic fishing (e.g., for tuna). There is no recreational allocation.

Highly Migratory Species: Bluefin Tuna

The LAPP for bluefin tuna differs in being a bycatch program, the IBQ program. The Atlantic bluefin tuna are managed by the Highly Migratory Species Division of the NMFS, within the U.S. commitment to the ICCAT. The IBQ program was created in 2015 as Amendment 7 to the 2006 Consolidated Highly Migratory Species Fishery Management Plan (79 Fed. Reg. 71510; December

___________________

8In theory, an ITQ is an IFQ with transferability. However, in the United States the federal fishery management system has adopted the practice of using IFQs as synonymous with ITQs. In this report, the committee follows that practice except when a distinction is important. All cases in this study employ some degree of transferability.

2, 2014) to create greater incentives and tools for longline fishers to minimize regulatory discards of bluefin tuna within fisheries for other large pelagics, such as swordfish. The pelagic longline fishery is not allowed to directly harvest bluefin tuna. Direct harvesting is instead done by a very large recreational fishery, both private and for hire, and by other commercial fisheries (the “general category” for hook and line, purse seine, harpoon, and trap). The pelagic longline sector gets a small percentage (8.1% plus annual adjustments) to account for its bycatch, which is allowed to be sold. The purse seine sector is allocated a much larger percentage (18.6%). The purse seine fleet has become inactive since 2005; consequently, about 75% is put into a reserve which can be reallocated to other sectors, and that which is held by individual permit holders can be leased to pelagic longliners.9

DATA AND INFORMATION CHALLENGES

To assess the social, economic, and ecological impacts of LAPPs in mixed-use fisheries the committee must address a number of data and evaluative challenges. Many of these challenges stem from significant gaps or biases in data collection. For example, data on social or economic indicators are often only available after the implementation of a LAPP, whereas impact analysis inherently requires longitudinal comparisons before and after policy implementation. In other cases, significant biases or blind spots may exist in otherwise robust data collection efforts. For example, for reasons of cost and feasibility, many economic and social science data series focus on vessels or vessel owners but fail to capture the outcomes and perceptions of other participants with less consistent or well-documented participation (e.g., crew members) or individuals who once participated but have now exited the fishery.

Another fundamental evaluative challenge relates to the complex and dynamic nature of mixed-used fisheries. They are complex social-ecological systems, and therefore the committee expects the ecological, social, and economic state variables affecting commercial and recreational fishery stakeholders to change over time in ways that may be quite difficult to predict—even in the absence of the implementation of a LAPP. For example, external drivers such as coastal population growth, regional economic transformation and gentrification, globally integrated seafood markets and associated competition with farmed seafood, disasters (e.g., harmful algal blooms, hurricanes, and oil spills), and the effects of climate change on ecosystems all influence the trajectory of fishing livelihoods and the welfare of fishery-dependent communities.

Failing to account for these underlying dynamics may lead to a biased assessment of a particular LAPP’s impacts. The attribution of a particular trend to the effect of LAPP implementation is often confounded by the other simultaneous effects. Furthermore, large policy measures such as LAPPs often are naturally combined with other policy changes in ways that may make it difficult to separate the effects of the LAPP from other aspects of the policy “bundle.” For example, LAPPs may be implemented as part of a stock rebuilding program—so the total quota of commercial harvest may decline at the same time LAPPs are implemented, thus making it difficult to separate the effect of LAPPs from the quota reduction.

These examples illustrate a general principle of impact evaluation: To assess the impacts of a LAPP on a particular fishery, it is not sufficient simply to point to changes in these variables before and after the LAPP went into effect as recommended in the guidelines for periodic reviews (Morrison, 2017b). Instead, one must establish how these changes differ from one or more plausible

___________________

9The purse seine fishery, which was very small and concentrated in New England, was assigned an allocation in a way that could be seen as a LAPP. The annual allocation to shareholders is transferable, in a limited sense, to the pelagic longline fleet. It has limited duration (1 year), and the size of a share is dependent on the previous year’s activity. When the current system that includes IBQs was created, IFQs to the purse seine fleet were intended to last only for the tenure of the grandfathered permit holders, expiring upon the sale of the vessels (Walter Golet, personal communication, 2021).

scenarios for what would have likely happened in the absence of the LAPP (Ferraro et al., 2019). In other words, any judgment about the impact of the LAPP is predicated on an implicit or explicit assumption about the “no-LAPP” counterfactual scenario (i.e., relating to or expressing what has not happened or is not the case). This scenario can be developed using a wide array of quantitative or qualitative approaches—from comparison of trends of paired “control” fisheries or communities not affected by the policy change, expert elicitation, qualitative scenario construction, or bioeconomic modeling. The most credible and practicable approach in a given scenario will depend on the nature of the impacts being considered, the complexity and extent of knowledge about the relevant causal feedbacks, and the availability of data.

The committee’s evaluation of the impacts of LAPPs in mixed-use fisheries is ultimately dependent on its consensus assessment of the published literature, Council and NMFS analyses, as well as insights provided by stakeholders participating in committee meetings and/or providing written input. These sources are distinct in their data types (e.g., qualitative versus quantitative), hypotheses being investigated, breadth and depth of data coverage (e.g., cross sectional versus longitudinal), and analytical approach. They also diverge in their approach to the challenge posed by the counterfactual no-LAPP scenario. In many cases this counterfactual is left unstated, or implicitly imagined as a static “no-change” scenario relative to a measured, recalled, or reconstructed pre-LAPP data point. This static reasoning, as argued above, is often lacking justification. The objective throughout this report is to place these distinct lines of evidence in conversation with one another, forming an assessment of each LAPP’s impacts relative to the most likely baseline scenarios, while being clear about the relative strength of evidence for distinct effects and gradations of uncertainty.

In many cases—due to sparse data, an absence of evaluative studies, or poor consideration of counterfactual scenarios in existing studies—it is difficult to provide straightforward evidence of certain impacts in the particular LAPPs being evaluated. In such cases the committee proceeds by drawing on a combination of theory from natural sciences, economics, and other social sciences. In synthesis with the broader empirical literature on LAPPs, the committee uses these theories to hypothesize plausible causal pathways for LAPPs to affect commercial and recreational stakeholders or broader communities as well as the qualitative nature of these impacts (e.g., positive versus negative impacts). The committee then draws on the peer-reviewed literature, Council and NMFS analyses, as well as insights provided to the committee by stakeholders to assess the evidence for or against these hypothesized impacts. The committee concludes by summarizing the overall weight of the evidence and providing suggestions for data collection and research to more rigorously evaluate these questions in the future.

Successful interdisciplinarity, a much-sought goal for integrated fisheries and marine research and policy, sometimes requires shared knowledge of and respect for divergent epistemologies (Moon et al., 2021) and consideration of different standards of evidence (Charnley et al., 2017). It also benefits from cooperation in data analysis and interpretation where possible, and transparency in reporting the results. The committee’s approach is consistent with the charge of the MSA (Section 301(a)(2)) to employ the “best available science” in its assessment. Beyond addressing the challenges of sparse data and causality noted above, the committee must also address the often distinct assumptions about methods and ways of knowing among the natural sciences, economics, and other social sciences (Charnley et al., 2017). The hypotheses investigated as well as data sources may differ by field, influencing what aspects of the system and outcomes are investigated. In addition, ethnographic data gathered by cultural anthropologists or human geographers may be less concerned with recovering an objective accounting of a single reality than in describing the heterogeneous lived experiences and perceptions of fishers and other stakeholders. Given this distinct goal, these data may be challenging to compare with data gathered by economists or other social scientists. Nevertheless, the committee views the lived experiences of those in fishery systems managed by LAPPs as vital to the assessment of these programs, and endeavors to integrate ethnographic data

into this assessment along with other qualitative and quantitative data without unduly privileging one over the other. In cases where ethnographic data appear to conflict or contradict other evidence, the committee critically examines the overall preponderance of evidence. In some cases, apparent divergences may be indicative of important differences in sample (e.g., active fishers versus those that have exited a fishery) or in the variables that are measured, such that seemingly divergent results are instead complementary when viewed in totality. In other cases, there may be significant “daylight” between the perceptions and lived experiences of individuals versus the best available objective metrics of the same phenomena (e.g., subjective perceptions of safety at sea versus objective risk exposure). In the case where the conflicting metrics are of comparable credibility (i.e., in terms of following best practices of research design and analysis), the committee’s presumption is that ethnographic data represent the best available assessment of the perceptions and lived experiences of the sampled individuals in the time period in question, whereas measured outcomes with quantifiable counterfactuals represent the best available assessment of causal impacts. Exploring the reasons for the divergence can be important for better understanding a policy’s differential impacts and the political economy of LAPPs in a particular system.

REPORT OUTLINE

Chapter 2 of this report provides background on the history of and rationale for IFQs in general. While the economic theory of IFQs predicts multiple benefits from their use, there is evidence that they might also have negative impacts on some participants in the fishery. After summarizing these concerns, the committee examines the specific language of Section 1853a, focusing on the ways Congress gave or did not give the Councils power to mitigate the predicted and observed negative impacts of LAPPs. Chapter 3 reviews the progress that has been made in meeting the individual goals for each LAPP as well as the broader goals set forth in the MSA. The committee analyzes the ecological effects of LAPPs on the study of mixed-use fisheries (Chapter 4). The committee then considers the social and economic effects of LAPPs on participants in the commercial sector (Chapter 5), recreational sector (Chapter 6), and broader community (Chapter 7). Finally, in the concluding chapter the committee assesses the effects of LAPPs in mixed-use fisheries. It recommends potential changes that could be implemented to mitigate negative impacts, while promoting the positive functioning of the LAPPs considered in this study as well as any future LAPPs that may be considered in mixed-use fisheries.