3

Stories of Intentional Inclusion1

The next session began with an introduction by moderator Lynn Ross, the founder and the principal of Spirit for Change Consulting in Miami Beach, Florida. She stated, “Equity does not happen by accident.” She explained that to achieve equity at various levels, it must be approached with intention. This session explored three specific cases and how inclusive placemaking and placekeeping was put into practice in these communities. The first presenters were Representative Armando Walle from the Texas House of Representatives and Jo Carcedo from the Episcopal Health Foundation. The second set of presenters were Ceara O’Leary from the University of Detroit Mercy and the Detroit Collaborative Design Center and Alexa Bush from the City of Detroit. The last set of presenters were Joe Griffin from Pogo Park and Gabino Arredondo from Richmond, California. Highlights from the panel are provided in Box 3-1.

STORY #1: HOUSTON2

Representative Armando Walle from the Texas House of Representatives (participating via video conference) described Houston and Harris

___________________

1 This section summarizes information presented by panel session speakers. The statements made are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

2 This section summarizes information presented by Representative Armando Walle from the Texas House of Representatives and Jo Carcedo from the Episcopal Health Foundation. The statements made are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

County, along with the surrounding areas, as vast and being comprised of about 6 million people with a high immigrant and Hispanic population. His district is located between downtown Houston and the George Bush Intercontinental Airport, and he noted that it is neither “inner city” nor suburban. Additionally, he noted that the 4–5 million people in his district live in unincorporated parts of the city and county. These areas also are a food desert, lacking a national grocery store chain.

Walle continued by discussing his years-long partnership with BakerRipley,3 an organization that serves the community where he attended high school, characterized by low socioeconomic status, high unemployment, and low educational attainment. East Aldine Management District is the region’s quasi-governmental entity that assesses a 1 cent sales tax with resources dedicated to infrastructure improvements, including wastewater services, law enforcement, and purchasing of land parcels. The agency purchased a 60-acre parcel of land with the goal of developing Aldine Town Center, and Walle brokered a partnership with BakerRipley. Following a capital campaign that raised $20 million to build three community center buildings, the BakerRipley expansion to Aldine yielded senior center programming, a maker space and youth fabrication laboratory, and a federally qualified health center. Walle said this partnership, and more specifically the community center, has been a catalyst for additional community investment. He noted that Lone Star College built a satellite campus on the land, along with the Harris County 911 Center and

___________________

3 BakerRipley Community Developers provides a wide range of community-based programs benefiting youth, families, and seniors in Houston (BakerRipley Community Developers, 2019).

the Rose Avalos P-Tech4 High School. Walle said that they are working on grocery store investment in light of the other community developments.

Walle concluded by mentioning that the U.S. Department of Commerce donated approximately $1 million to the BakerRipley community center, to which Walle plans on adding various aspects such as a city park and a hiking and biking trail system.

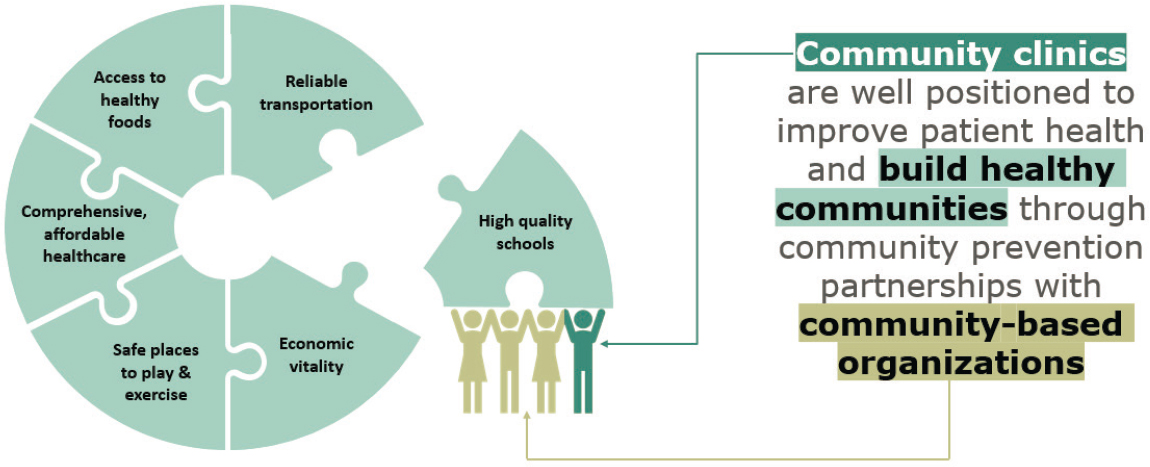

Jo Carcedo from the Episcopal Health Foundation followed Walle’s presentation. Carcedo was previously in the leadership of Neighborhood Centers, which is now BakerRipley. She said that Neighborhood Centers had its foundation in the resettlement and child care movements, which helped shape its vision. Carcedo then described the Episcopal Health Foundation as “a public charity and supporting organization of the Episcopal Diocese that owned a hospital system at the time and sold it” (the foundation has no relationship with the hospital). Carcedo described the foundation as being a “health conversion philanthropy,” valued at about $1.2 billion, of which $40 million goes to grantmaking to healthy places. She said they aim to be a catalyst for innovation and sustainability for healthy communities and one of the ways they do so is by supporting the Community-Centered Health Home (CCHH) organization.5 Carcedo explained that the Episcopal Health Foundation funded 12 clinics in east Texas, an area with some of the poorest health outcomes in the nation. Community clinics are uniquely positioned to “build healthy communities” (see Figure 3-1), and the goal is to look beyond the clinical setting to determine why patients are not healthy—causes linked to politics, policies, and systemic racism.

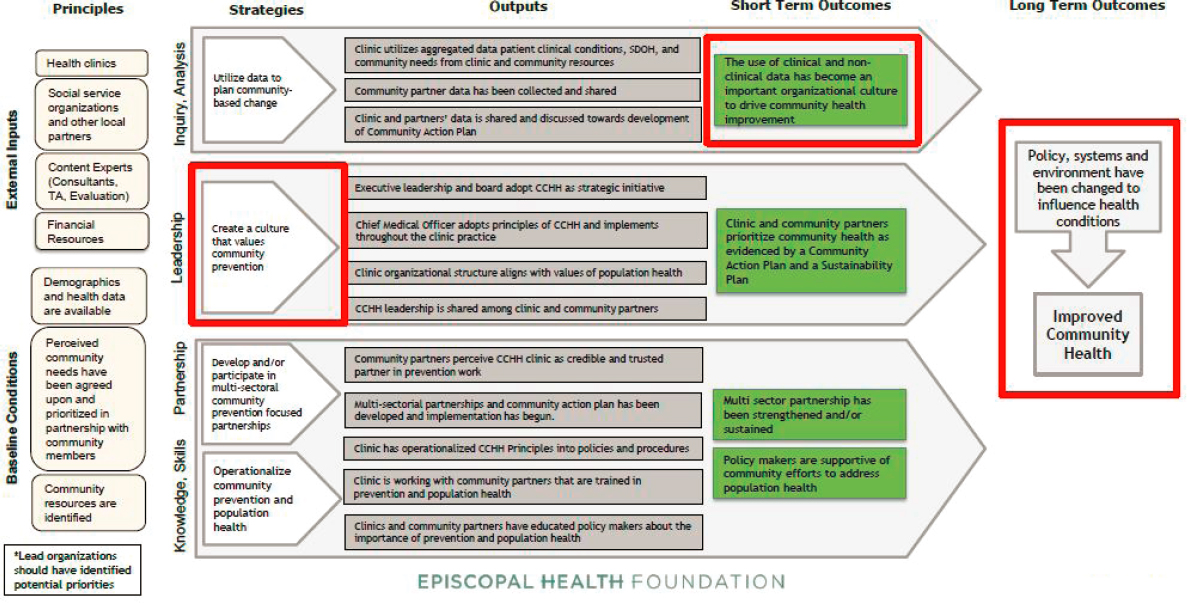

Carcedo continued by describing parts of the CCHH logic model (see Figure 3-2). In inquiry and analysis, she explained, this refers to the use and sharing of data. Part of the data collection includes determining what the community assets are outside of the clinical setting. To solve health problems and further equity, she said, they must be approached using all information available in a community, along with involving community members (see Figure 3-2).

Carcedo explained that policies and environmental changes should be made early in the planning process and done with intent and through an equity lens. She also said that success depends on the strength of the partnerships, and that requires infrastructure and financial support, capacity building, and “a health institution as an anchor.” For example, the BakerRipley community center, she noted, includes a clinic to work in collaboration with aspects of health outside of clinical care.

___________________

4 P-Tech is the Pathways in Technology Early College.

5 CCHH is a health care organization that actively engages and supports community prevention to promote health in addition to providing clinical services (Prevention Institute, n.d.).

SOURCE: Carcedo presentation, February 6, 2020.

NOTE: CCHH = community-centered health home; SDOH = social determinants of health; TA = teaching assistant.

SOURCE: Carcedo presentation, February 6, 2020.

Carcedo said that the built environment is a social determinant of health, and communities can leverage money and resources that are legally designated to be invested in communities for improvements. She shared that communities can hold government entities accountable to provide them with services already guaranteed to them, and such a systems approach leads to more sustainable change. A community can use its built environment to tackle health problems, such as diabetes, by ensuring the availability of spaces to exercise and walk. She said her organization was able to reclaim areas and make them more welcoming to the community to encourage participation in various activities. With increased community participation, she added, trust was built between health care providers, law enforcement, and community members to support a sustainable and healthy place.

Ross asked Walle and Carcedo to elaborate on the notion of building trust with intention. Walle responded by saying that in his experience with BakerRipley, the organization already had leaders in place in the community. For example, the Aldine Management District has a board of directors, many of whom live in the community and the local school district, and it also employs staff who had previous relationships with the community. During multiple planning meetings and gatherings with various community leaders, the district also listened to what people wanted to see in their community.

Ross asked how responding to a crisis, such as flooding (commonplace in Houston), informs the panelists’ “thinking about the necessity for inclusive placemaking.” Walle recalled Tropical Storm Allison,6 along with numerous storms since then. He explained that the city held a community meeting with various agencies, and community members demanded responsive action to address flooding issues and concerns. He said it was important for the agencies and community members to have a platform to work through their needs and hold accountable those responsible. He concluded by saying that while they have the largest medical center in the world, only a couple of miles away, there is stark poverty and no access to health care. He said he is proud of the work being conducting with the BakerRipley partnership.

Carcedo added that the numerous severe weather storms created an environment that required “communities, people, stakeholders, [and] institutions [to start to work] tougher in ways that cut across race and structural considerations around governance.” The Episcopal Health Foundation does not implement programs but rather, Carcedo stated,

___________________

6 Tropical Storm Allison was a tropical storm that was part of the 2001 Atlantic hurricane season (NOAA, 2019).

it looks at what it can do to support and build infrastructure for solving community health problems.

STORY #2: DETROIT7

Ross introduced Alexa Bush from the City of Detroit and Ceara O’Leary from the University of Detroit Mercy, the Detroit Collaborative Design Center, and Reimagining the Civic Commons (RCC).8 RCC, Ross explained, is a national demonstration that seeks to reimagine and reconnect public spaces with “people of all backgrounds, cultivate trust, and counter the trends of social and economic fragmentation” (RCC, 2017). RCC has programs in Akron, Chicago, Detroit, Memphis, and Philadelphia. Each is resident-led and authentic to the place where it is unfolding. Ross said that “public spaces” was defined “broadly” and included green spaces, sidewalks, streets, and libraries and other “third” places. Bush said reimagining efforts share the following outcome areas: “civic engagement, socioeconomic mixing, value creation, and environmental sustainability.” Ross turned to Bush to discuss the Fitzgerald Revitalization Project.9

Bush defined the Fitzgerald Project Area as a predominantly African American neighborhood occupying a 6-square-mile district in northwest Detroit, a city with household incomes as low as $13,000 and as high as $100,000. She said that this project requires a framework that works across sectors, departments, and outside organizations along with community members and leaders. She highlighted three aspects that she found to be most important. The first aspect is to determine how to best use public space to get “at the heart” of the reinvestment—having noted earlier that there are more than 400 parcels publicly owned by the City of Detroit land bank—and to be intentional with creating well-maintained public spaces and rehabilitating salvageable structures. The second aspect is to develop a robust and engaged infrastructure to address inclusivity. The third important factor is to provide creative transportation options throughout the city, to meet the community need to move freely in the area, particularly for children and seniors. Designing walking and biking

___________________

7 This section summarizes information presented by Alexa Bush from the City of Detroit and Ceara O’Leary from the University of Detroit Mercy and the Detroit Collaborative Design Center. The statements made are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

8 See https://civiccommons.us (accessed January 25, 2021).

9 The Fitzgerald Revitalization Project has the goal of revitalizing a quarter-square-mile area and its three parts are to create a neighborhood park and greenway, develop economically self-sustaining landscapes, and rehabilitate salvageable publicly-owned structures (Fitzgerald Revitalization Project, n.d.).

paths was intentional in order to change the grid of the neighborhood to make it “be more walkable and promote health.”

Bush said the project acquired 26 vacant lots and used them to create a park at the center of the neighborhood in July 2018. She shared that an artist was hired to make a large ceramic tile mural depicting the community story, which was built together with the residents. Using public dollars in creative and intentional ways helps build an inclusive space that works for both people and businesses, Bush added.

O’Leary continued by adding that additional work is set to begin on several vacant properties at the northern boundary of the Fitzgerald Project Area, along with streetscaping work. The redevelopment area has made a physical space for cross-sector collaboration, which is known as the Neighborhood Home Base, including office and meeting space and a community shared space for “block club meetings, for community association gatherings, [and] for other nonprofit workshop events.” The Neighborhood Home Base is staffed by residents within the Fitzgerald Area Project and provides a welcoming environment.

O’Leary reiterated Bush’s point about the need for community engagement and involvement. She said the City of Detroit held cookouts in vacant lots to talk to residents who happened to be passing by in order to open dialogue about the neighborhood and the various initiatives. She described that residents themselves created test programs similar to “pop-ups” to see what activities would be supported by the neighborhood. As a result, resident leaders have emerged, even as young as 12 years old. She said this has shown community ownership and has been a sustainable part of engagement, and the various collaborative efforts across sectors and across the neighborhood have contributed to success.

Ross asked O’Leary and Bush how they were able to prioritize art design and beauty—which, she noted, is a basic right that should not be reserved only for some—in development and how they were able to use it as a way to promote engagement. O’Leary responded by saying that there was some hesitation to invest in making public spaces more aesthetically pleasing because it could lead to displacement of current residents. Her organization made plans to prevent gentrification or displacement through policy, community participation and ownership, and land acquisition. They ensured that residents were part of the engagement process, including decision making and responding to resident input. Bush added, echoing Ross’s remarks, that there is too little beauty, and having beautiful and well-designed public spaces should not be only for the elite. The Detroit Planning Department has been trying to improve the design of public spaces and buildings. Bush also said that the park’s name, Ella Fitzgerald Park, was selected by residents and references a former community school at the site, to preserve the identity of the neigh-

borhood. The park’s ceramic tile mosaic was created by Hubert Massey, a Detroit-based artist, and the residents,10 and Bush said the “tile by number” installation allowed the community to take part in its creation. She said it was important to have residents say, “I literally built this piece of the park” because it “[changed] the relationship between the people and park.”

Ross asked about partnerships and coalition building, noting that when the work on the Fitzgerald Revitalization Project began, Detroit was rebuilding after filing for bankruptcy. Bush said they began work on the project in 2015, as the city planning department itself was just being rebuilt. While this upheaval has been a challenge, it has also provided an opportunity to build the department using the Fitzgerald neighborhood as a model to promote collaboration, channel investment, and design aspects of the neighborhood. Bush said that she had to find partners that were able to establish structures that promoted residential involvement, such as hiring local residents. O’Leary continued by saying that the collaboration between city departments and the Community Development Financial Institutions Funds11 has given a “holistic approach to neighborhood investment.” Relationship building should also be cultivated even if there are not any active projects, she said. Part of this is creating working groups that are representative of the all stakeholders, which provides the foundation for future projects. She said having two educational institutions, including the University of Detroit Mercy and the new Cradle to Career campus, has been important for that holistic approach.

Ross then asked about money and how funding is managed with so many partners. Bush said that most of their funds come from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to promote affordable housing. She said they had a sales tax revenue bond for streetscape improvements. Additional funding has come from philanthropic organizations, such as an additional $1.6 million for affordable housing. This funding is more flexible compared to governmental funds. Since they had a goal of engaging the community, they gave small grants for residents to become neighborhood leaders and ambassadors. She said that there were investment discussions at the meetings to align ideas and projects. O’Leary added that hiring residents to take on various projects has given them more flexibility and allowed them to invest both in the community

___________________

10 For a news article about the park, see https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit-city/2018/07/28/grand-opening-ella-fitzgerald-park/855589002 (accessed January 25, 2021).

11 Community Development Financial Institutions aims to expand economic opportunities in low-income communities and provide financial products to residents and businesses (USDT, 2020).

and its members. She explained that the success of the project is measured using metrics that showed engagement and trust building as outcomes.

Ross asked about the pop-up projects and their links to long-term investment, and what advice O’Leary and Bush would give to other communities about a long-term investment approach. O’Leary responded by describing the types of pop-up events, including testing out new initiatives, to “activate vacant spaces that then became the park.” She explained that those operating the pop-ups build relationships with others in the neighborhood and identify assets. She said it was important to hold pop-up events on a regular basis as they have been doing for about 5 years. This reliability, she explained, built more infrastructure and partnerships compared to if they had only held one pop-up total. Another pop-up event that they conducted, O’Leary shared, was with Better Block, a Texas-based nonprofit organization aimed at educating, equipping, and empowering communities for healthy neighborhoods (Better Block, 2019). She explained that this included three temporary installations of streetscape improvements, along with events that drew residents and visitors to the area to discuss their projects. She believed that they would not have been able to have these conversations in a traditional meeting setting and that this alternative setting allowed people to “dive into the issue and see what it could be like.”

Colby Dailey from the Build Health Places Network asked the presenters what would be the most critical advice to organizations looking to do similar work in smaller or mid-sized cities. O’Leary said the most critical thing was to ensure that residents have a role in the planning and decision-making process. She suggested that this role be designed so that the engagement can reflect the neighborhood and its people. Bush added that having a clear mission with outcomes is the most critical thing because it will ensure that funding is being allocated in innovative and appropriate ways. Ross added that, in her experience in Akron, Ohio, project success is based on how quickly trust is built between residents and partners. Carcedo commented that it is easier to build on existing partnerships and relationships than start anew.

To conclude this session, an unnamed audience member commented that she was able to visit the Fitzgerald neighborhood and felt it “[personified] inclusive healthy places.” She referred to the earlier visualization exercise lead by Torchio. The audience member said parks are typically what comes to mind as examples of healthy places, but added that inclusive healthy places connect parks to streets and places throughout a neighborhood. She noted that this transforms places into healthy and inclusive spaces.

STORY #3: RICHMOND, CALIFORNIA12

Joseph Griffin, executive director of Pogo Park, the organization responsible for the two Pogo Parks—the physical places—including the original park, Elm Playlot. Griffin said he was originally a community volunteer conducting a community PhotoVoice project13 with Pogo Park. For parks that have the designation of being a Pogo Park, community members must be “involved in the design, build, and evaluation of the park,” and the work must be responsive to needs and changes in the community. The social environment for this work includes the existing social connections and expertise in Richmond.

Gabino Arredondo from Richmond, California, provided context to the local circumstances in the early days of Pogo Park. Arredondo said that Richmond was not an attraction to those living outside of the community due to concerns about violence and because it is home to a Chevron refinery, one of the largest greenhouse gas emitters in California. However, Richmond has a positive history of environmental justice movements, resistance, and organizing. At the time the work of Pogo Park began, the city’s General Plan, a document for local land-use decisions, was being updated. Arredondo said that the Richmond General Plan was one of the first in the state to include an element on community health and wellness, and had a 30-year time horizon. For this plan, he said, the city and its community partners piloted programs in the Iron Triangle and Belding Woods neighborhoods. Cities face fiscal constraints, and Richmond has had to reducing staffing, even though there is additional work. They had funding from The California Endowment’s Building Healthy Communities program and other philanthropic sources, which helped fill the gaps.

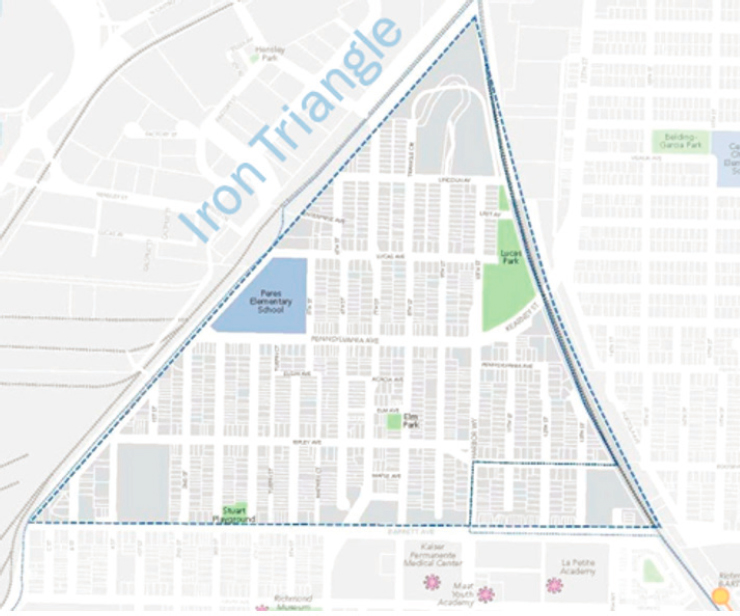

The city of Richmond, Arredondo stated, has a population of 100,000 and 32 miles of coastline. It is led by a city manager and city council, which he noted is important to know for navigating change. In Richmond’s case, he said they needed the support from the full community and four votes on the city council for anything to be successful. He then described the Iron Triangle (see Figure 3-3) as having physical borders created by the Pacific Rail Lines.

Arredondo said that as part of the city’s general plan implementation, these rail lines are part of the Richmond Greenway, “a 3-mile community bicycle and pedestrian rail–trail bordered by 32 acres of community--

___________________

12 This section summarizes information presented by Joseph Griffin from Pogo Park and Elm Playlot and Gabino Arredondo from Richmond, California. The statements made are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

13 Pogo Park PhotoVoice was a 2008 project that asked community members to take photos and record videos about things they liked and disliked about their neighborhoods and parks. As a result, Elm Playlot was restored by the neighborhood residents (Pogo Park, 2013).

SOURCE: Arredondo presentation, February 6, 2020

designed artwork, urban agriculture, and recreational space” supported by more than $2 million for planning and construction from Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, a nonprofit organization that works to create trails from former rail lines (Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, n.d.). The Elm Playlot is located in the Iron Triangle, along with Perry Elementary School, Lucas Park, and the Nevin Community Center.

Arredondo said that as the city began implementing the General Plan’s community health and wellness element, his team was assigned to collaborate with the school district, which he noted, was significant because the city of Richmond had been operating in silos. He shared that this brought the various sectors to meet together at the same time. Some of the foundation money, he said, was used for capacity building and system organization, reinforcing their collaboration. He said another benefit to meeting at a school was that it brought city employees into the community to see and experience the neighborhood that they were trying to change. Furthermore, Arredondo said it was important to use

language that would encourage support during meetings. For example, he said they would not say the term “institutionalized racism.” Instead, they used “health” because it would be difficult for others to be opposed to it. Lastly, Arredondo said that it was important for people who were investing time and money into revitalization to have tangible and short-term measures of success. Many aspects of health, he said, take years to see significant change, which can be discouraging. Instead, for example, he questioned how many bike lanes can easily be quantified. Arredondo closed by saying that they have been documenting nontraditional successes with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to capture the “feeling” that has changed around the community.

Ross continued the discussion by bringing up the importance of play and that it is an equity issue because “not all kids have access to play regularly, to play freely, to play safely.” She asked Griffin and Arredondo if they could elaborate on how they engaged youth in the development of the Elm Playlot and Pogo Park model. Griffin responded by saying the process to develop Elm Playlot was completed in 2014; however, they continue to change it to respond to community wants and needs. He stressed the importance of “designing with the community, not for the community.” To convey messages and ideas, he said they approached it in many ways such as 3-D modeling, pop-up parks, temporary structures, and prefabricated models. When designing the playground, he said they did so with the intention for inclusivity and accessibility to children of differing abilities. He gave the example of a disc swing that can accommodate up to four children, thus encouraging group play, and a design that makes it accessible for children with disabilities. Another example he gave of designing with intention was omitting a traditional slide structure and instead having a structure that can be removed and replaced in pieces. This allowed the park to be flexible to suit the community’s needs. Lastly, Griffin discussed the importance of the park being staffed by residents. He told the story about one of his colleagues who had some children go to her home to ask her for help in the park on her day off. He reflected that she felt happy to know that she was someone they could go to for help. Arredondo added that having residents staff the park helped to maintain the park itself. If there were issues such as dumping or graffiti, he said they would be able to identify who was creating the problem and would work across sectors, including law enforcement, to support the park and its staff. Arredondo also said that by having community members be actively involved and engaged in the process alongside governmental and nongovernmental agencies, they were able to accomplish unlikely initiatives, such as adding a zip line to the park.

Ross observed that there are things that a city is able to accomplish and things they are not, which is a reason to have partnerships; however,

partners may not see that cities would like to be more involved in the process. She asked if they had advice for partners on how to effectively work with cities that wish to be actively involved in building capacity and advancing development. Arredondo responded, saying that the city of Richmond brought an outside person to complete training alongside city staff, and city leadership promoted the idea that all staff, from maintenance workers to city managers, were health providers and clinicians. This helped to change the working environment and perceptions. Additionally, he said having clear priorities, supported by leadership paired with funding, “goes a long way.”

Ross asked about the role of securing buy-in from policy makers. Griffin, a native of Richmond, highlighted the benefit of it being a smaller city. He remarked on its city pride and its ability to make connections quickly. He felt a sense of stewardship and ownership for the health of the residents in Richmond. As such, he relayed that relationships are cultivated and there has been an effort to understand others’ assets and challenges. Additionally, he said that promoting healthy spaces is not controversial, so they have not experienced much political opposition to their initiatives. Arredondo continued by explaining that the health in all-policies approach became institutionalized when the General Plan—including the health and wellness element—was approved by the city council. This achievement opened funding opportunities to them, such as through California’s Proposition 84, which gives grants for parks, job training, and housing. Paired with an engaged community, he felt they were positioned well for additional funding and support. He explained that cities can apply for certain funding for which community-based organizations would not be eligible. Arredondo said he believes this is a valuable role for cities to play.

In response to a question from Ross about the Yellow Brick Road, Arredondo explained that “the Yellow Brick Road is a Safe Passages project” with the intent of linking two Pogo Parks together. It was developed by community youth who were concerned about having a safe way to get across the community due to traffic. The street is “a literal yellow street” and along it there are houses, churches, and the only hospital in Richmond. Arredondo added that the Yellow Brick Road intentionally connects to the Marina Way, where there is more development occurring.

DISCUSSION

A brief discussion and question-and-answer session with the audience followed the panel’s presentations. Dora Hughes from The George Washington University asked about how to balance being direct and confronting race, racism, and discrimination when talking about health and

health equity. Arredondo said he will sometimes be “explicit, sometimes implicit.” At the beginning of the work, he felt that it was more subtle, but as relationships have been built and outreach has occurred, it has become more explicit. He gave the example of a community exercise they conducted, which asked residents to explore their greatest sources of stress in Richmond, and the predominant responses were racial profiling, issues with police, and issues with violence. So, he noted, residents were more explicit, which gave permission for the city to also be explicit. He said, “tension brings up change,” which can be positive. In response to that exercise, he noted that they implemented implicit bias training with the local police and had community members complete the training as well. An underlying issue related to racial profiling was the lack of identification among residents, so they created a system that linked the municipal identification with the banking system to prevent the use of check-cashing businesses where customers would be charged high fees. He reiterated the importance of the city staff being part of the community and reflective of its people. Griffin added that when they talked about solutions to such stressors, it was important to use similar terminology and encourage open communication. After a follow-up question from Hughes about potential considerations of private funding sources, Arredondo then pointed out that Pogo Park is a nonprofit organization and that securing funding has been and will continue to be a concern. Pogo Park has 15 full-time staff members who all have equal say in what funding or resources will be accepted.

Russo and Arredondo discussed the various parks in Richmond. Arredondo estimated that there are approximately 30 parks, with about 10 that are community led and community driven. However, there are many that have varying levels of community engagement. He described Groundwork Richmond.14 They have trained youth, called Air Rangers, who conduct regional air monitoring throughout Richmond. He stated that the data collected are and will be used to reduce air contaminants and improve the health of residents.

Russo asked whether they have found a network of organizations of similar interest and activities around parks. Griffin answered in the affirmative and said they often host other organizations. He referenced the Global Learning Exchange through the Institute of Urban and Regional Development at the University of California, Berkeley, through which he, Arredondo, and others from Richmond traveled to Nairobi to learn strategies to engage with community members and how to promote investment in areas without existing strong financial support. Another example he

___________________

14 Groundwork Richmond is an organization that aims to restore urban forests in Richmond, California, by using youth to replant trees (Groundwork Richmond, 2020).

gave was a representative from the U.S. Forest Service, who gave talks about urban green spaces. Ross added that she has seen a rethinking of public spaces globally. She referred to a workshop with the Salzburg Global Seminar that focused on urban parks, children, and health, which included participants from around the world.

Doug Jutte from the Build Healthy Places Network in San Francisco noted that Pogo Park is a community development corporation (CDC), which is what he is involved in at the Build Healthy Places Network. He asked Griffin and Arredondo whether they have used CDC networks. Griffin had not but mentioned that his executive director, Toody Maher, likely had since she understood the importance of discovering assets and expertise within communities.

Naughton asked for opinions on what makes good public and private partnerships and aspects of problem-solving processes. Arredondo said the aspect that was paramount was “to get to know the community.” As someone from outside of Richmond, he noted that there was distrust because of broken promises made by various agencies. While he acknowledged connections and relationships, he said that “it is very fragile.” A way to combat this is to continue the relationship even when there is no longer funding or a project. He states that this shows the community that you are committed to them. Griffin continued saying that “you show up when you don’t want something [to show] that you actually care about people.” Additionally, paying people for their time and services has been valuable, he mentioned.

Meadows commented that there can be momentum loss during projects due to things such as governmental changes and loss of community leaders. He asked how the panelists would suggest keeping the momentum going, beyond paying people for their time and services. The second part of the question asked how to measure whether a community is becoming healthier in a nonclinical sense. Griffin first responded about measures. In 2007, he noted, that they started a mixed-methods study on “the health impacts of the redevelopment of Elm Playlot,” which looks at publicly available data on health indicators and a community survey on social cohesion and perceptions. In addition, they are using the PhotoVoice project to capture qualitative data. He said that partnering with academia has helped to capture such measures. Griffin then spoke to the question about momentum. He advocated for identifying community leaders that may not be part of an organization to promote networks within the community. Arredondo reiterated that continuity had been reassured due to the institutionalization of their work. Regarding measures to capture health improvement, he noted that his team suggested a self-rated health question be included in a national survey of cities.