3

One Health in Praxis

The second session of the workshop examined three case studies of the implementation of One Health practices, integration into public health systems, and strategies for mitigating relevant barriers. Dana Wiltz-Beckham, director of the Office of Science, Surveillance, and Technology at Harris County Public Health (HCPH), Texas, United States, described the One Health initiative at her organization. She provided an overview of its structure, growth, and responses to various outbreaks and natural disasters in recent years. Supaporn Wacharapluesadee, researcher at Thai Red Cross Emerging Infectious Diseases Health Science Centre (TRC-EID), King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand, outlined the roles of discovery, diagnosis, and research and development in early detection and control of an outbreak. She discussed the expansion of testing capacity in Thailand and reviewed research findings on coronaviruses in bats and pangolins. Thierry Nyatanyi, senior advisor of the Africa Task Force for Novel Coronavirus at the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), outlined Rwanda’s coordinated response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). He discussed numerous measures, such as a rapid scale-up of epidemiological surveillance—including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) testing—and outlined strategies for future improvements in health system resilience. The panel was moderated by Kent Kester, vice president and head of translational science and biomarkers at Sanofi Pasteur.

OPERATIONALIZING ONE HEALTH AT A LOCAL LEVEL

Presented by Dana Wiltz-Beckham, HCPH (Texas, United States)

Wiltz-Beckham described the population, infrastructure, and weather patterns of Harris County, Texas. She outlined the organizational structure of HCPH and detailed the offices and divisions that participate in its One Health initiative. Providing examples of HCPH responses to zoonotic outbreaks and natural disasters, she described the implementation of the One Health model and contrasted this collaborative approach with the siloed approach it had previously used.

Features of Harris County, Texas

Located in southeast Texas near the Gulf of Mexico, Harris County spans more than 1,700 square miles and contains 4.7 million people. Wiltz-Beckham described Harris County as one of the most diverse communities in the United States, with more than 145 languages spoken among its residents. Houston, the fourth-largest city in the United States, is located in Harris County and has two large public health agencies: Houston Health Department and HCPH.1 Houston is also home to Texas Medical Center, the largest medical center in the world, in addition to one of the world’s largest seaports, two international airports, and the nation’s largest concentration of petrochemical facilities. HCPH houses the largest refugee health screening program in Texas. Wiltz-Beckham noted that these details paint a picture of the diverse and complex nature of Harris County. Due to its proximity to the Gulf of Mexico, Harris County is the “gateway of hurricanes,” said Wiltz-Beckham. In addition to hurricane impacts, the county has been affected by incidents related to its petrochemical facilities. Over the past 4 years, the area has experienced several crises, with impacts currently ongoing: Hurricane Harvey in 2017, a petrochemical fire in 2019, COVID-19, and Winter Storm Uri in 2021.

HCPH Organizational Structure

HCPH comprises five divisions specific to subject matter. The Disease Control and Clinical Prevention (DCCP) Division includes the tuberculosis and refugee health programs. The Environmental Public Health (EPH) Division conducts sanitation and inspection services. The other divisions are Nutrition and Chronic Disease Prevention, Veterinary Public Health (VPH),

___________________

1 More information about Harris County Public Health can be found at https://publichealth.harriscountytx.gov (accessed March 29, 2021).

and the Mosquito and Vector Control Division (MVCD). Additionally, HCPH has five offices that transect across divisions: Communications, Education and Engagement; Finance Services and Support; Policy and Planning; Public Health Preparedness and Response; and the Office of Science Surveillance and Technology. Wiltz-Beckham noted that HCPH is a comprehensive local health department, offering a full range of services, including veterinary public services, animal control, preparedness, outreach, dental, HIV prevention, mosquito vector control, inspection of pools and nuisance complaints, sanitarian services, and immunizations.

Wiltz-Beckham outlined the offices and divisions that contribute to the One Health initiative at HCPH. The Office of Science Surveillance and Technology addresses epidemiology, tracking and monitoring, and data housing, and also serves as a repository for science-related items. Disease Control and Clinical Prevention provides physician services, and Nutrition and Chronic Disease Prevention offers mental health expertise. VPH provides animal control services and responds to safety codes related to rabies. MVCD works to decrease disease spread at the source. EPH ensures food safety, offers lead poisoning prevention efforts, and works to increase the safety and health equity of the built environment.

One Health Responses at HCPH

Discussions around One Health began at HCPH in 2013, and operationalization was initiated in 2014, said Wiltz-Beckham. With more than 60 percent of infectious diseases in the United States resulting from animals, HCPH routinely addresses zoonotic diseases (Taylor et al., 2001).

West Nile Virus Response

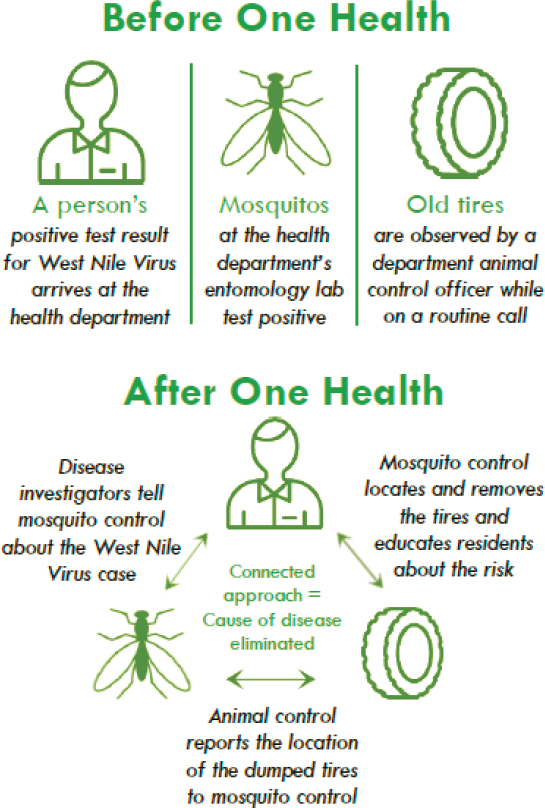

Wiltz-Beckham noted that before adopting the One Health approach, HCPH staff worked in silos (see Figure 3-1). For example, if the epidemiology department’s surveillance program or epidemiology (EPI) team received a positive lab result for West Nile virus, the program would confirm the case and proceed to investigate it, educate the infected individual, contact the hospital, run EPI processes, and report the case to the state health department; in turn, the state health department would report it to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Independent of those processes, Wiltz-Beckham explained, MVCD tested mosquitoes for West Nile virus and sprayed accordingly, while sanitarians (officials responsible for public health) and animal control officers out on routine calls may have observed old tires—known breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Each office or division would conduct these activities independently, without communicating. She described the implementation of the One Health initiative as

SOURCE: Wiltz-Beckham presentation, February 23, 2021.

breaking down these silos through collaboration. Now, when surveillance and the EPI team identify a positive case of West Nile virus, they notify MVCD. Wiltz-Beckham noted that a lack of data sharing by zip code, which designates location in the United States, has historically been a barrier to effective response efforts at HCPH and also at the local, state, and federal levels. Upon notification, MVCD can investigate the location of the positive case and determine whether spraying is required. Animal control

officers and sanitarians now report sightings of old tires to MVCD, who remove the tires or treat the area with mosquito dunks to prevent breeding.

Zika Virus Response

The response to the 2016 outbreak of Zika virus is another example of the collaboration One Health has brought to HCPH, said Wiltz-Beckham. The department formed a multidisciplinary team that included law enforcement, policy staff, VPH, the EPI team, EPH, and medical professionals. The team trained and worked together to develop a Zika response. Partnering with home associations and places of worship, the communication and education outreach team went into neighborhoods to hold health fairs and teach residents how mosquitoes breed. Responding to this public health issue with focus on equity, she explained, areas were analyzed with an index of social vulnerability, and locations with high scores were targeted for testing mosquitoes. When positive cases were identified, the team studied the relevant areas. The response shifted from low-tech (such as outreach and education) to high-tech strategies. These included partnering with Microsoft to develop a system that captures mosquitoes, determines sex, and measures wing movement to identify species—as various species carry different viruses.

Rabies Response

Wiltz-Beckham noted that the United States has effectively decreased rabies cases over time, but rabies still persists. In Harris County, the majority of cases occur in bats, she said, with 7–10 percent of bats submitted each year for rabies testing carrying the virus. Once an animal tests positive, a multidisciplinary team is alerted, and animal control officers go to the area to conduct outreach services. For example, HCPH physicians communicate with veterinarians in an effort to ensure that anyone who came into contact with the rabid bat is evaluated. In cases where rabies post-exposure treatment is needed, the physicians assist those individuals in accessing required treatment. Wildlife experts, community outreach, and the media also have roles in the response.

Hurricane Harvey Response

More than 3 years after the 2017 disaster, Wiltz-Beckham said Harris County continues its recovery efforts in response to Hurricane Harvey. Involving multi-agency coordination, HCPH has collaborated with organizations throughout the country and the nation. Community-engagement efforts include an HCPH mobile health village that provides a “one-stop

shop” of public health outreach services, including rabies vaccinations and microchipping for dogs; dental evaluations for children; flu shots; registration for social benefits, such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; and information on preparedness. After Hurricane Harvey, the mobile health village was set up throughout Harris County. Additionally, HCPH conducted surveillance in shelters for people and pets displaced by the hurricane. Mosquito control, environmental health, and animal management services have also been part of HCPH’s Hurricane Harvey response.

COVID-19 Response

Wiltz-Beckham stated that HCPH’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic began on January 9, 2020, and has been continually updated since. The surveillance and EPI team grew from 25 staff members to nearly 500. The social services department works with individuals who need to be quarantined or isolated but do not have spaces in which to do so. Pet owners are educated regarding the risks of COVID-19 to animals. They also offer testing and vaccination services and, with a specific focus on ensuring equity, addressing underserved areas lacking these services, she added. The Office of Policy and Planning develops policy guidance and works with Communication and Engagement to release timely information to the public via news media and social media. The Health Alert Network provides dental, veterinary, and health care education information. A seroprevalence project is currently studying humans with COVID-19 antibodies, while another pilot project is under way to investigate prevalence and seroprevalence in animals. Lastly, HCPH is learning from best practices shared by China and South Korea.

Winter Storm Uri Response

Texas was recovering from Winter Storm Uri, which severely affected the state in February 2021. The surveillance and EPI team monitored warming centers (short-term emergency shelters that operate during inclement weather events) for viruses. Wiltz-Beckham noted that HCPH provided services to the homeless population and to animals during the storm, as well as offering mental health services. Carbon monoxide poisoning was also addressed.

One Health Growth at HCPH

For the past 14 years, HCPH has hosted an annual conference. What began as a small workshop at the local zoo grew into a large veterinary

conference; in 2017, it evolved to its current iteration as a One Health conference, bringing together professionals from veterinary, medical, environmental, and public health disciplines.2 The most recent conference was held in October 2020 (virtually, due to the pandemic). Wiltz-Beckham noted overwhelmingly positive feedback from participants regarding sessions on emerging pathogens and microbial threats.

Wiltz-Beckham stated that HCPH is implementing various One Health initiatives at the local level. The organization began without any designated One Health staff positions, added part-time coordination assistance, and now has full-time One Health and global health coordinators. As future pathogens emerge, additional work will be needed to address these and increases in cases and risk, she said. For example, in the United States, disease cases from infected mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas tripled from 2004 to 2016 (Rosenberg et al., 2018). Meeting such challenges will require increased funding, vector control, research, and education. Advocating for the continued growth of One Health, HCPH is working toward establishing proactive policies and funding support that is flexible and appropriate to build necessary capacity at the local level. This involves educating the governing body about One Health’s role and importance. Wiltz-Beckham added that HCPH continues to hold multidisciplinary conversations and improve response evaluation to identify gaps and potential solutions.

MULTI-SECTORAL ENGAGEMENT IN THE COVID-19 OUTBREAK RESPONSE IN THAILAND

Presented by Supaporn Wacharapluesadee, King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital (Bangkok, Thailand)

Wacharapluesadee discussed components of outbreak detection and control. She outlined efforts to expand surveillance and testing in Thailand, highlighting additional capacity-building measures that have taken place since the pandemic began. Reviewing research of coronaviruses in bats and pangolins, she also detailed findings linking the virus to bats.

The “Three Ds” of Outbreak Detection and Control

Wacharapluesadee outlined the “three Ds” of early detection and control of an outbreak—discovery, diagnosis, and research and development—and described how Thailand effectively performed these in its COVID-19

___________________

2 More information about HCPH’s One Health Conference can be found at https://publichealth.harriscountytx.gov/Services-Programs/All-Programs/One-Health-Conference (accessed March 29, 2021).

response. Discovery involves Thailand’s early detection efforts, which are provided by a partnership of the Department of Disease Control (DDC), the Department of Medical Science (DMSc), and TRC-EID, which is located at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital and Chulalongkorn University. Diagnosis pertains to outbreak control. Wacharapluesadee explained that reference laboratories in the diagnostic laboratory network, including DMSc, TRC-EID, and universities, expanded rapidly to include provincial public health laboratories and private laboratories to deliver 24-hour turnaround time. She said that this enabled DDC to respond promptly by investigating contact cases, resulting in better control and containment. Research and development provide knowledge to strengthen early detection efforts that eventually lead to diagnosis and also inform response efforts. During the pandemic, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency contributed funding to expand Thailand’s capacity to cope with the emerging infectious diseases, Wacharapluesadee noted. Additionally, a national, multi-sectoral collaboration among the Ministry of Public Health, private hospitals, and the academic research center expanded surveillance of variants of SARS-CoV-2 that cause COVID-19.

The PREDICT Diagnostic Approach

Spanning from 2010 to 2019, USAID’s PREDICT research project was implemented in 35 countries at high risk for zoonotic disease emergence, including Thailand, said Wacharapluesadee.3 In April 2020, it was extended to provide emergency support to Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aiming to improve surveillance by strengthening capacity for sampling and laboratory detection of known viruses, PREDICT-Thailand efforts resulted in 59 staff members trained in One Health skills, 678 humans and 3,288 animals sampled, 42,610 tests administered, and 448 viruses detected (mostly coronaviruses, both novel and previously identified). To detect viruses, Wacharapluesadee explained, the PREDICT diagnostic approach used a family-wide polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a consensus primer, which provided broad amplification of multiple genetically related pathogens, including previously unidentified ones—enabling both known and novel viruses to be detected within the same PCR reaction.

Wacharapluesadee presented a table of surveillance results in wildlife she and her team tested over 5 years for several virus families, including coronaviruses, filoviruses, flaviviruses, influenza viruses, and paramyxoviruses

___________________

3 More information about PREDICT can be found at https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1864/predict-global-flyer-508.pdf and https://ohi.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/programsprojects/predict-project (both accessed March 30, 2021).

(PREDICT Consortium, 2020, p. 540). A heat map of the findings indicated that the majority of positive samples for coronaviruses were found in bats, she said. This process taught her and her team how to detect novel coronaviruses in bats, which would inform procedures for humans. The coronavirus family-wide PCR was used to discover the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus in 2012, she added (Zaki et al., 2012).

Discovery of the COVID-19 Virus

Learnings from the MERS discovery, coupled with her findings about coronaviruses in bats, Wacharapluesadee said she was able to perform family-wide PCR detection on an unknown virus that the Thai government asked her laboratory to identify in January 2020. The workflow involved the collaboration of three national laboratories. DDC’s Bamrasnaradura Infectious Diseases Institute was responsible for detecting all known respiratory pathogens from the same sample. Two other samples were sent to Wacharapluesadee’s laboratory at TRC-EID, where she performed family-wide PCR for coronavirus and influenza virus and next-generation sequencing.4 The DMSc also tested for unknown pneumonia. She explained that when a pathogen is unknown, different detection protocols are used. The discovery of the first COVID-19 case in Thailand began on January 8, 2020, she said, when specimens tested with viral family PCR assays were positive for a coronavirus. The following day, Wacharapluesadee stated, sequence matching with the gene bank indicated that the virus shared 83–90 percent identity with coronaviruses found in bats. It did not match any human viruses, she explained, and at that point, the coronavirus sequence from Wuhan, China, was not yet available. On January 11, 2020, China shared the data of the virus that caused the unknown pneumonia in Wuhan; her laboratory then reanalyzed the sample and found it was a 100 percent match with that disease. The next day, TRC-EID and DMSc performed next-generation whole genome sequence analysis, with both laboratories confirming that the virus was the same as that found in Wuhan.

Thailand’s COVID-19 Detection Capacity

Wacharapluesadee stated that with Thailand’s diagnostic network expanding to include more than 200 laboratories in 76 provinces,

___________________

4 “Next-generation sequencing,” or “high-throughput sequencing,” is an umbrella term used to refer to modern nucleic acid sequencing techniques (distinct from the traditional Sanger sequencing method). For more information, see https://www.ebi.ac.uk/training/online/courses/functionalgenomics-ii-common-technologies-and-data-analysis-methods/next-generation-sequencing (accessed July 7, 2021).

COVID-19 PCR results can be delivered within 24 hours. She noted that an enhanced biosafety level 2 molecular laboratory has been created in the past year to perform COVID-19 testing. Thailand’s laboratory network is able to target multiple genes and perform high-throughput real-time PCR. The nation’s capability to perform rapid, quality-controlled testing enables effective outbreak control efforts. Led by Thailand’s national laboratory, a multi-sectoral collaboration is conducting surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 variants. Wacharapluesadee presented a table of surveillance findings generated by a partnership between TRC-EID, DDC, and private hospitals working to identify variants entering the country via the airport. Targeting people who are quarantined by the state after traveling abroad, the collaboration is able to report detected variations within 5 days of arrival at the airport, she said.

Bat and Pangolin Coronavirus Research

The horseshoe bat, Rhinolophus affinis, was thought to be a probable origin of SARS-CoV-2 (Zhou et al., 2020). Found in south China, Thailand, Cambodia, and Indonesia, this bat can become infected with RaTG13—a betacoronavirus that shows 96 percent nucleotide identity to SARS-CoV-2 found in humans (Ge et al., 2016). To fight viruses related to SARS-CoV-2 in Thailand, Wacharapluesadee and her team have been working to identify the origin of virus variants. The Department of National Parks, Wildlife, and Plant Conservation, Chulalongkorn University, and Kasetsart University began an international collaboration with Duke-National University of Singapore’s Emerging Infectious Diseases Program in June 2020 to study bats in connection with SARS-CoV-2 (Wacharapluesadee et al., 2021). Wacharapluesadee and a team of researchers went to east Thailand, where they collected 100 Rhinolophus acuminatus, or acuminate horseshoe bats, from a cave. The team took blood samples for serology surveillance and rectal swabs for PCR and genetic study; 13 of the 100 bats tested positive for coronaviruses. She continued by stating that researchers sequenced the 290-base pair RdRp gene and identified a close relationship to both the human SARS-CoV-2 and the RaTG13 found in bats—with homologies of 95.9 percent and 96.2 percent, respectively. When whole-genome sequencing was performed, the percent homology with the human SARS-CoV-2 dropped to 91.5 percent—less than the 93.7 percent shared with the RmYN02 virus detected in bats in China, she said. Wacharapluesadee presented a phylogenetic tree of the complete genome that indicates that RacCS203, a virus found in Thai horseshoe bats, is a new member of the SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus lineage.

According to a receptor-binding function study on the Thai virus RacCS203 using the phylogenetic tree of the receptor binding domain

(RBD) gene, Wacharapluesadee said it was found to belong to the non-angiotensin converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) usage clade. Whereas the bat RaTG13 and the human CoV-2 types of coronaviruses can bind ACE-2, these findings indicate that, currently, RacCS203 is not harmful to humans. Rc-0319 from bats in Japan and CoV in pangolins in China were also found to interact with ACE-2.

Sero-surveillance of COVID-19 was conducted in bats and pangolins, said Wacharapluesadee. Samples collected from the animals were tested with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay that measures the levels of neutralizing antibody using a surrogate virus neutralization test. The results for the bat sera, she explained, indicated that four of the 98 samples were positive for interaction with SARS-CoV-2—the human RBD. Two of these, she stated, had an inhibition titer greater than 80 percent. As mentioned, the PCR result was positive for 13 percent of the 100 bats tested. For the pangolin serums, Wacharapluesadee said one in 10 was positive against the SARS-CoV-2 RBD antigen using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, with a very high percent similarity, as seen in the bat serum. All pangolin samples were PCR negative.

Wacharapluesadee highlighted key findings from this research:

- Serology will be a key tool in performing frontline surveillance.

- Other SC2r-CoV viruses are circulating in bats, and the neutralizing antibodies reflect past infection(s) by other CoV(s) that may be more closely genetically related to SARS-CoV-2.

- More surveillance in animals is needed.

She concluded by noting the impact of multi-sectoral engagement on sentinel surveillance, referral laboratory networking, data sharing, research networking, technology transfer, and policy advice. Moreover, the contributions and collaborations of a wide variety of organizations strengthen the capabilities of the laboratory, enabling it to address novel viruses.

COVID-19 RESPONSE: LESSONS LEARNED TO REINFORCE THE RELEVANCE OF ONE HEALTH PRINCIPLES

Presented by Thierry Nyatanyi, Africa CDC

Nyatanyi outlined existing frameworks for responding to disease outbreaks. He described trade measures the East African region took in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, then detailed Rwanda’s government-led, coordinated pandemic response, which included mitigation measures, free medical services, increased production of needed supplies, and vaccine deployment. He also highlighted Rwanda’s rapid scale-up of SARS-CoV-2

testing and epidemiology surveillance and listed strategies to improve health system resilience.

Existing Frameworks to Support National Response to Infectious Disease Threats

Nyatanyi explained that numerous regulations are in place to support countries responding to disease outbreaks, such as the World Health Organization’s International Health Regulations (WHO’s IHR), the World Organisation for Animal Health’s (OIE’s) Aquatic Animal Health Code and Terrestrial Animal Health Code, and the Tripartite Guide.5,6,7 Such regulations have informed frameworks that include the IHR monitoring and evaluation framework, national action plans for health security formed through WHO’s Joint External Evaluation,8 OIE’s Performance of Veterinary Services Pathway (PVS),9 IHR-PVS national bridging workshops,10 and Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA).11 Nyatanyi noted that all of these allude to preventing the spread of infectious diseases without interfering with international trade. For instance, the purpose and scope of the IHR are “to prevent, protect against, control, and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease in ways that are commensurate with and restricted to public health risks, and which avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade” (WHO, 2008b). Both the Aquatic and Terrestrial Animal Health Codes state that these standards should be used “to develop measures for early detection, internal reporting, notification, control, or eradication of pathogenic agents in animals and preventing their spread via international trade in animals and animal products, while avoiding unjustified sanitary barriers to trade” (OIE, 2019a,b).

___________________

5 For the Aquatic Animal Health Code from OIE, see https://www.oie.int/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/aquatic-code-online-access (accessed July 7, 2021).

6 For the Terrestrial Animal Health Code from OIE, see https://www.oie.int/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/terrestrial-code-online-access (accessed July 7, 2021).

7 The Tripartite refers to WHO, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and OIE. For more information on the Tripartite Guide, see http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/CA2942EN (accessed July 7, 2021).

8 For more information on the joint external evaluation process, see https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/international-health-regulations/monitoring-and-evaluation/joint-external-evaluation-jee#:~:text=The%20JEE%20is%20a%20voluntary,of%20the%20International%20Health%20Regulations (accessed July 7, 2021).

9 For more information on the PVS capacity-building platform, see https://www.oie.int/en/what-we-offer/improving-veterinary-services/pvs-pathway (accessed July 7, 2021).

10 For a fact sheet on the IHR-PVS national bridging workshop, see https://extranet.who.int/sph/sites/default/files/document-library/document/Fact%20sheet%20_final_Lite.pdf (accessed July 7, 2021).

11 For more information on GHSA, see https://ghsagenda.org (accessed July 7, 2021).

East African Regional Response to COVID-19 Outbreak

Despite the existing guidance, it was challenging to find guidance for the specific issues related to COVID-19 in the early days of the pandemic, Nyatanyi noted. The first case in Rwanda was an imported case confirmed on March 14, 2020, and 6 days later, the government responded by closing the land borders and airport (Karim et al., 2021). Because Rwanda is a landlocked nation, the government allowed travel and trade from neighboring countries to continue, Nyatanyi said, and it was discovered that many truck drivers that were tested as they crossed into Rwanda were positive for the virus. The heads of state within the East African community region met and determined that all COVID-19 test results would be accessible to countries within the region, he said. This practice supported the continuation of travel and trade within the regional economic bloc amid the pandemic. Airports reopened in August 2020, with reverse transcription to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing (RT-PCR) required for travelers. The land border partially opened in November 2020. Nyatanyi pointed out that in the absence of international guidance framing the reopening process, Rwanda worked to develop solutions as the pandemic evolved. He added that cases imported into the country continued, highlighting the need to review frameworks moving forward.

Rwanda’s Emergency Response Framework

Rwanda has long managed public health threats, including the 2009 influenza A H1N1 pandemic and the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, said Nyatanyi (Nyamusore et al., 2019; Wane et al., 2012). These outbreaks culminated in implementing One Health as an integrated approach (Nyatanyi et al., 2017). Rwandan senior leadership invested substantial time and resources in establishing a One Health framework for responding to outbreaks, he said, noting that much travel and trade takes place between Rwanda and neighboring Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo—two countries that experience outbreaks of viral hemorrhagic fever every 2–3 years. While a One Health coordination mechanism was in place at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Nyatanyi explained that the global impact led the Rwandan Prime Minister’s office to establish a framework specific to COVID-19 days before the first case was diagnosed in the country. It uses an expert advisory team composed of academic institutions and development partners who provide guidance on response measures; its components include epidemiology and surveillance, logistics and administration, risk communication, and planning.

Nyatanyi explained that Rwanda’s COVID-19 emergency management plan is chaired by high-level decision makers, allowing for fast-tracking

response efforts (see Box 3-1). He noted that adherence to mitigation measures was evidenced by use of public hand-washing stations and social distancing at typically crowded public places, such as bus stops. Local government assisted with enforcement of these mitigation efforts. The COVID-19 services Rwanda provided free of charge—including testing, quarantining, and treatment—proved to be very effective in curbing the spread of infection. Nyatanyi emphasized that government lockdowns can become complicated without public buy-in, but the Rwandan government made efforts to build public trust as lockdowns and closures were instituted. Import delays occurred as truck drivers entering Rwanda tested positive for COVID-19 and had to be quarantined and isolated. These import gaps were addressed by efforts to boost local manufacturing. The production of protective equipment and vaccine deployment fast-tracking are other important components of the emergency response efforts that Nyatanyi noted, explaining that the pandemic has exposed challenge areas that were not addressed by the original One Health coordination mechanism. For example, economic issues related to trade and tourism were not considered until the pandemic.

Nyatanyi presented a graph of COVID-19 incidence rates in Rwanda and Kigali, the nation’s capital, from June 2020 to February 2021. A surge of cases in Kigali led to a lockdown in January 2021. He emphasized that

an effective lockdown requires coordination, management, and communication, using messaging to convince the public of its necessity. Nyatanyi pointed out that 14 days after the lockdown, the city’s COVID-19 cases decreased significantly, from a peak 7-day incidence rate of more than 120 per 100,000 population to less than 100 per 100,000.

Expansion of Rwanda’s Testing Capacity and Surveillance

Highlighting the national scale-up of testing capacity, Nyatanyi noted that prior to the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, Rwanda had only two Rotor-Gene PCR cycler machines able to test for the virus. Within 9 months, procurement of testing machines was fast-tracked, resulting in 88 more being made available in locations across the country, he said. Large-scale training was conducted to create a workforce able to use the new machines, and capacity was expanded to include both rapid and PCR testing. Nyatanyi discussed the role of research in optimizing testing capability. Given the considerable expense of RT-PCR testing, he and his colleagues researched a method in which 20 individual samples are pooled and tested with the resources required for one test (Mutesa et al., 2021). At a low prevalence, they were able to accurately identify infected individuals; in higher-prevalence areas, pooling by 10 samples was found to be effective. Nyatanyi emphasized that this method is cost effective in using far fewer resources to test large groups of people. This exemplifies the need for institutions to work with people on the forefront of service provision to develop innovative ideas, he stated, and pooling is enabling Rwanda to test greater numbers of people at a capacity of 4,000–5,000 tests per day with limited resources.

In addition to testing, Rwanda is using a number of capacity indicators to track virus incidence, including the proportion of hospital beds and intensive care unit beds occupied by COVID-19 patients and the number of home-based care patients with the virus. He noted that Rwanda also tracks the proportion of new cases who have completed contact lists and the proportion of those new contacts that have been notified. While some of these epidemiologic surveillance and capacity indicators are similar to those used by WHO, others are unique to Rwanda, developed while generating solutions for tracking at the country level using geolocation. Rwanda, he explained, has established a four-level alert system with thresholds associated with each indicator—for example, if a given number of people in a village test positive for COVID-19 within a 7-day time frame, that number will determine whether the village is at the “new normal” level or at the low-, moderate-, or high-alert level.

Rwanda’s concept architecture for epidemiologic surveillance uses the ArcGIS Enterprise platform for tracking indicators within administrative boundaries, Nyatanyi said, noting that it is an innovative solution created

by young engineers.12 It provides information such as numbers of confirmed cases and deaths by district, age, and gender distributions, as well as whether cases are imported or local. All people have access to this information, including epidemiologists, decision makers, and the general public. The Rwandan government has relied on these data to determine needed efforts in various districts. Furthermore, a number of innovative, homegrown technologies and solutions (e.g., mobile apps for contact tracing) have been developed locally in Rwanda. Nyatanyi stated that innovation is a key area of the pandemic response that can be applied to strengthening One Health implementation.

Improving Health System Resilience

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, response reviews typically took place after the end of an outbreak, said Nyatanyi. In an effort to assist countries in reviewing best practices while in the midst of responding to an outbreak, WHO has issued guidance for conducting intra-action reviews (IARs) (WHO, 2020). In Rwanda, Nyatanyi said, IAR has proved to be a valuable tool—particularly during the country’s surge of new cases in November 2020—because it was used to update and validate the COVID-19 Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan. IAR also provided Rwanda with insights about gaps, which were identified in all aspects of the response and related to the decentralization of efforts. These included case management, risk communication, coordination, and overwhelmed health facilities. Rwanda also adopted WHO’s guidance for home-based care, which required the support of the entire health care system. Community health workers assisted in implementing the approach, which decongested health facilities and assured continuity of health services. Nyatanyi suggested the development of specific One Health metrics for IAR processes while responding to an outbreak.

Nyatanyi stated that lessons learned from Rwanda’s government-led approach to COVID-19 can be applied to institutionalizing One Health (see Box 3-2). Emphasizing the value of applying lessons learned from the pandemic to future outbreaks, Nyatanyi closed with the long-standing axiom: “never let a good crisis go to waste.”

___________________

12 ArcGIS is a software that combines location, map, and analytics data, among others. For more information, see https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/about-arcgis/overview (accessed July 7, 2021).

DISCUSSION

Funding and Capacity-Building Advocacy

Kester noted that Wiltz-Beckham discussed a comprehensive health department with inter-digitations in multiple areas. While a government’s primary role is to ensure the population’s safety—and health and public health are indeed aspects of safety—competition for resources from areas such as infrastructure can push public health concerns to the background outside of crises, he said. Given that local and state governments can serve as laboratories of innovation and best practices and that leadership drives resource allocation and capacity building, Kester asked how a public health agency can keep health issues at the forefront of leaders’ concerns in the midst of competing needs. Wiltz-Beckham emphasized that all public health efforts require buy-in. Social networking can be used by developing relationships with leaders and even capitalizing on mutual acquaintances who may have their ear. In advocating for public health initiatives, public health practitioners must believe in the work and effectively explain what they do and how and why they do it. Issues of funding and capacity need to be communicated to policy makers, she asserted, as agencies may not meet

criteria for grant funding. This is an area of improvement for public health practitioners, and it involves an ongoing process that takes time, Wiltz-Beckham remarked. She gave the example that HCPH had an innovative and forward-thinking leader who traveled to other agencies to learn and share ideas, then brought ideas back to HCPH and led brainstorming sessions around potential benefits and methods of instituting the ideas at their health department. This approach enabled HCPH to fully digest new ideas; in turn, this demonstrated and promoted the importance of One Health to their governing body. Wiltz-Beckham noted that this process can become political, given the role of local, state, and federal government in funding, but that should not discourage public health practitioners from continuing the positive momentum the COVID-19 pandemic has initiated.

Disseminating Best Practices and Innovations

Noting a worldwide need for access to best practices and innovations in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, Kester asked Nyatanyi whether Rwanda has been able to effectively disseminate information to neighboring countries, given the differences in governments, culture, and language. Nyatanyi replied that academic institutions are channels for conveying information to the scientific community via evidence-based publications and that Rwanda has thusly shared best practices. Sharing innovations regarding information and communications technology has been more challenging, which could be addressed by developing methods of doing so through scientific forums and research institutions, he suggested.

Research Initiative Funding

Kester noted that Wacharapluesadee and her colleagues were able to respond to the evolving COVID-19 pandemic rapidly and comprehensively. He asked whether the initiatives she has been involved in are funded by the government, academia, government–academic partnerships, or external entities; he also queried how she was able to quickly access funding. Wacharapluesadee responded that substantial support for research at the onset of the pandemic in early 2020 came from private-sector donations. These included machines that expanded testing capacity, as the original capacity was only 200–300 cases per day. International support provided the donation of a sequencer. She added that the government also reimburses academic institutions for other research-related costs.

Highlighting the size of Harris County’s population and the scope of HCPH’s programming, Kester asked Wiltz-Beckham if all efforts rely on government funding or other funding sources are used. She replied that the majority of HCPH’s efforts are via general funds and grants from the

government. In addition, she explained HCPH has partnered with Latinx faith-based and non-profit organizations to address issues such as lack of access to nutritious food or COVID-19 tests in Houston’s large Latinx communities.13

Addressing Cultural Attitudes

Noting that Wiltz-Beckham commented on partnering with specific groups who are aware of societal norms, perspectives, and helpful approaches particular to a certain population, Kester asked whether cultural attitudes or traditional health practices played a role in Rwanda’s response to the pandemic. Nyatanyi remarked that misperceptions regarding COVID-19 have been common during the pandemic, but Rwanda has worked to identify mechanisms and channels to address misconceptions. The country’s Ministry of Health (MOH) recognizes traditional medicine and has an association of registered traditional healers. Thus, traditional healers are part of the health care system and have regular and frequent encounters with ministry personnel. This relationship has established trust and enabled effective communication among MOH, traditional healers, and people treated with traditional medicine, he said, allowing the MOH to dispel misconceptions.

Hypotheses on the Origin of COVID-19

Given the extensive assessments Wacharapluesadee has done thus far, Kester asked for her opinion as to the origin of COVID-19, noting that the risk for other viruses to jump from animals to humans will not disappear with the pandemic. Wacharapluesadee replied that based on her 6 months of study in Thailand during the past year, in which a virus related to SARS-CoV-2 was found in both bats and pangolins, one of these animals was believed to be the progenitor of the virus that evolved and was transmitted to a human and then from human to human. She added that more surveillance is needed to clearly understand all of the SARS-CoV-2-related viruses in animals and arrive at a definitive answer to this question.

One Health Education and Awareness Efforts

Many of the initiatives highlighted during the workshop involve transdisciplinary efforts that developed with the support of external funding

___________________

13 The term “Latinx” is a gender-neutral, pan-ethnic label that has been used by some as an alternative to Latino/Latina. For more information, see https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2020/08/11/about-one-in-four-u-s-hispanics-have-heard-of-latinx-but-just-3-use-it (accessed July 7, 2021).

from responsive leadership or coalitions of organizations, said Kester. He posited that One Health’s continued growth can be strengthened by developing the concept in medical and veterinary students, thus equipping them with a One Health perspective before they graduate. Noting the impact that providing curricula about recycling in U.S. high schools in years past had on raising teenagers’ awareness of recycling, Kester asked the panelists how One Health concepts can be inculcated through the education system. Wiltz-Beckham suggested that efforts begin earlier than postsecondary school, in primary grades. She noted that education efforts about smoking have led children to encourage their family members to give up cigarettes. She added that public health institutions can learn from animal rights organizations, such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, that have used effective marketing strategies to raise awareness. Educating young children means that messages will already be instilled in them when they become future leaders, said Wiltz-Beckham. Kester remarked that educating children about the importance of public health expands on the concept of local jurisdictions serving as laboratories of innovation.

Nyatanyi commented that education efforts need to begin with shifting the mindset of the educators themselves. He noted that while he was leading a One Health steering committee in Rwanda, prominent scholars were unable to agree with one another. When educators disagree, it becomes difficult to translate messaging into academia, he posited. Nyatanyi added that the “brain-drain” phenomenon is an additional challenge Rwanda faces, as youth who are receiving training in school may not remain in the country to apply those learnings as future leaders.

Wacharapluesadee stated that Thailand has a One Health coordinating unit, which is a collaborative effort among seven ministries and the Thai Red Cross. This unit brings the concept of One Health to the community level through health volunteers. She said that in order for communities to be prepared for any emerging infectious disease, training and education are needed. In Thailand, this service is performed by more than 10,000 volunteers and is one mechanism for instilling the One Health concept in the community, said Wacharapluesadee.

Implementing One Health in Underresourced Areas

Kester discussed global disparities in public health and stated that areas lacking in economic growth, infrastructure, and education face challenges in pushing new initiatives forward. He asked Wiltz-Beckham how the best practices developed and continually refined by HCPH can be adopted in places with fewer resources. She replied that public health entities can perform internal scans of their resources and their understanding of the One Health concept. Not all local public health departments look

the same, but they all provide some essential public health services. For instance, a local health organization in a rural area may immunize children and perform health inspections at restaurants, she said. Even within this limited scope, opportunities exist to empower people with knowledge. Additionally, opportunities to advocate for One Health can arise while offering current services. For example, she explained, a sanitarian performing inspections may see tires in which mosquitoes are breeding and locate a community partner to provide funding for mosquito dumps. Wiltz-Beckham added that some organizations may be performing One Health work and not even realize it.

Now that HCPH has positions dedicated to carrying forth One Health initiatives, the responsibility to share knowledge and experience with others is incorporated into their roles, Wiltz-Beckham noted. Through mentoring and “training the trainer,” HCPH One Health professionals are able to conduct virtual sessions with public health workers in other states and countries. Similar to the counseling South Korea and China have offered other nations regarding COVID-19, best practices can be shared in these sessions, said Wiltz-Beckham. Kester stated that there is good knowledge available, but the challenge lies in disseminating it in the proper context.

Interdepartmental Collaboration

Kester asked Wacharapluesadee for her thoughts on an intergovernmental One Health panel assembled to weave best practices and scientific considerations into policy that can be customized for regional and national considerations. She responded that in Thailand, One Health practice in the government is quite strong. The MOH, DDC, the Department of Livestock Development, and the Department of National Parks, Wildlife, and Plant Conservation work closely together. Research work connects them. For example, in Wacharapluesadee’s 10 years of work with the PREDICT project testing novel viruses, a mechanism was in place to report findings to all government sectors. Academic research serves as a tool that draws sectors together in collaborative learning. She remarked that government officers have routine work that prevents them from having time to dedicate to developing the One Health concept, and researchers can connect while working together in offices.

REFLECTIONS FROM DAY 1

Eva Harris, professor of infectious diseases and director of the Center for Global Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley, summarized the day’s sessions. She highlighted Goosby’s emphasis on establishing transparent, safe spaces in which experts and officials can alert

the international community when a threat is detected. Harris also summarized the case studies presented on current One Health initiatives, noting that Rwanda has embraced a One Health approach at the national level for many years; this was evidenced in its multi-sectoral response to the COVID-19 pandemic, in which various ministries have collaborated. Rwanda’s multilevel approach has emphasized solutions and innovations from the local to national levels.

Kester discussed several themes that emerged during the first day of the workshop. He noted the key aspects of pandemic prevention highlighted by Goosby: detection, response, and prevention. Whether those areas are placed within the context of a One Health rubric or public health in general, they fit together to form imperatives for public health practitioners and decision makers responsible for keeping the population safe. He also pointed out several themes that arose during the second session’s presentations. The first theme is that One Health requires multidisciplinary coordination, which may develop organically but more often must be established with effort and intention. This coordination is needed regardless of whether the setting is a large urban county health department in Texas, a national surveillance and detection effort in Thailand, or a broad public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Rwanda. Developing and maintaining coordination can be a challenging endeavor and necessitates constant sustainment, said Kester.

The second theme is the transdisciplinary nature of One Health, involving vectors, vector control, zoonosis, environmental impact, public health, health care systems, education, and more. Kester noted that One Health is not owned by professionals; rather, it is a partnership between professionals, paraprofessionals, and the community. He added that education efforts extended to primary school students could highlight the value of the multidisciplinary aspects of One Health. The third theme is the need for capacity, which underlies the ability to execute ideas, surveil, and prevent and respond to outbreaks. The fourth theme is innovation. Many of the innovations discussed were developed by necessity in response to COVID-19 or as methods of reaching specific populations, said Kester. Innovation applies to laboratory science and also extends to approaches to populations or policy that have never been tried before. He added that many of the innovative practices presented are suitable for greater dissemination regionally and beyond.

The final theme highlighted—perhaps the most important, from Kester’s perspective—was touched on by Goosby and in all the presentations: leadership. A well-functioning public health organization cannot be well positioned to anticipate or respond to a crisis if leadership is unaware of that organization’s role. Enlightened, educated leadership is needed to prepare for crises, especially given the multiple, competing demands on attention.

Kester remarked that the COVID-19 pandemic remained the global focus, with the reemergence of Ebola in Africa in early 2021 receiving little attention. Public leaders and policy makers can easily divert their attention to other issues, he noted, so strong leadership is needed to make better decisions regarding One Health or public health, which are intertwined.

This page intentionally left blank.