6

Learning from the Past and Planning for the Future of One Health

The third session focused on innovative technologies, frameworks, and collaborations that could mitigate future pandemic threats. The session’s objectives were to discuss (1) lessons that can be learned and extrapolated from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, including priority actions for policy, public–private partnerships, and industry resilience to build a broad, threat-agnostic global health system and (2) strategies to facilitate international cooperation and data sharing to establish forecasting capabilities for emerging health threats. Jonathan Quick, managing director of pandemic response, preparedness, and prevention at The Rockefeller Foundation, discussed possible detection and response mechanisms of the future that would enable outbreaks to be swiftly controlled before becoming pandemics. Katherine Huebner, veterinary medical officer at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM), and Danielle Sholly, animal scientist at FDA CVM, discussed the threat of African swine fever (ASF) and its global impact. They outlined features of the One Health approach FDA uses in addressing this infectious disease. John Amuasi, co-chair of the Lancet One Health Commission and leader of the Global Health and Infectious Diseases Research Group, Kumasi Centre for Collaborative Research-Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana, highlighted the role of prevention policy, the paradoxical nature of resistance to prevention efforts, and the impacts of health inequalities and prevention inequities on individuals and nations simultaneously facing poverty and viral outbreaks. Rajeev Venkayya, president of the global vaccine business unit at Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd. and member

of the board for Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), reviewed advances in vaccine innovation during the COVID-19 pandemic. He outlined preclinical, clinical, and manufacturing measures that could accelerate the development of vaccines for novel viruses. The session was moderated by Peter Daszak, president at EcoHealth Alliance.

PRECISION EPIDEMIOLOGY, HUMAN BEHAVIOR, AND THE FUTURE OF ONE HEALTH

Jonathan Quick, The Rockefeller Foundation

Imagining future possibilities in outbreak detection and response, Quick described a scenario in 2035 in which an outbreak is swiftly controlled and ended within 100 days. He suggested possible advances in collaboration, methodology, and technology that would enable this vision to become reality. Quick discussed current efforts to improve the data pathway to increase the speed with which infectious diseases can be detected and controlled. Highlighting that goals deemed impossible may actually be feasible, he provided examples of progress made in outbreak response over the past 50 years.

The 2035 Pandemic That Wasn’t

Quick remarked that the next generation will inherit advances and challenges from the generations before it. Imagining the future they will inhabit, he painted a scenario illustrating the continuum of animal and human health and what might be expected in the year 2035. In this scenario, ongoing, routine zoonotic surveillance is performed. Big data are used, including human data, microbial or health service data, data related to climate change, and animal and vector data. Artificial intelligence fuels geo-risk assessments used to determine priority surveillance locations. Point-of-contact surveillance is performed in communities. Risk-based assessments inform onsite, viral genomic surveillance in animals, and routine surveillance takes place in humans and animals that are particularly at risk.

The scenario then forwards to 30 days before the imagined outbreak. At this point in the future, much has been learned about key genes and about how genes in animals may affect humans. Some patterns emerge in 2035 that are associated with virus transmission to humans, based on genomic sequencing. When a worrisome virus is spotted, more intensive animal sequencing is performed to look for patterns associated with deadly virus strains. More intensive surveillance of humans also commences, particularly on those in contact with at-risk animals.

Fast-forwarding to 15 days before the outbreak in the scenario, the alert level is increasing. Targeted testing and screening are increased to a

wider geographic area. The hypothetical Global Genomics Surveillance Center is alerted, and the center notifies national authorities and local human and animal services to increase vigilance.

A large portion of the population owns wearable electronic devices, as inexpensive models are widely available, and device privacy is fully protected. On day 0 of the outbreak—when the first case is reported—individuals receive health alerts on their devices. The “astute clinician”1 is aware of the alerts and suspects a novel virus. Genome sequencing confirms a new, previously unknown virus strain. On day 1, the frontline sequence is deposited in a global viral sequence repository, where it is made available to governments, universities, and industry worldwide. Diagnostic and therapeutic professionals assess what steps may be necessary for humans and animals, and vaccine development begins.

By day 7, airborne transmission is confirmed, making the virus highly transmissible among humans. The first virus-attributed deaths take place, and some cases require extended hospitalization. In the year 2035, 3-D printing of diagnostic tests is feasible, and tests become available now. Local actions are set into motion, including social distancing, masks, quarantining, and the at-home “lollipop” testing developed through technology advancements. Global travel alerts are sent to the general public, and targeted, big-data travel patterns are performed. High-risk arrival locations conduct point-of-entry screening for that genome.

At day 60, therapeutics have already been developed and vaccines are becoming available. A variety of methods provide accelerated safety and efficacy testing far faster than in 2021. Advancements in manufacturing enable rapidly deploying vaccines in accordance with hot spot vaccination plans. Vaccines are even produced in patch form, making needles and syringes unnecessary; these are manufactured on 3-D printers and delivered via drones, increasing scalability. All other expected public health measures are in place.

On day 100, the last case is reported. Shortly thereafter, the outbreak is declared over.

Strengthening the Data Pathway for Outbreak Detection and Response

Quick stated that “the die is cast” during the first 100 days of an outbreak. Even the first few days of response to the initial case substantially affect the speed of exponential growth of an infectious disease. Thus,

___________________

1 Quick noted the “astute clinician” term applies to practitioners such as Carlo Urbani, the first person to identify severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) as a new virus, and Zunyou Wu, who was among the first scientists to study severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes COVID-19.

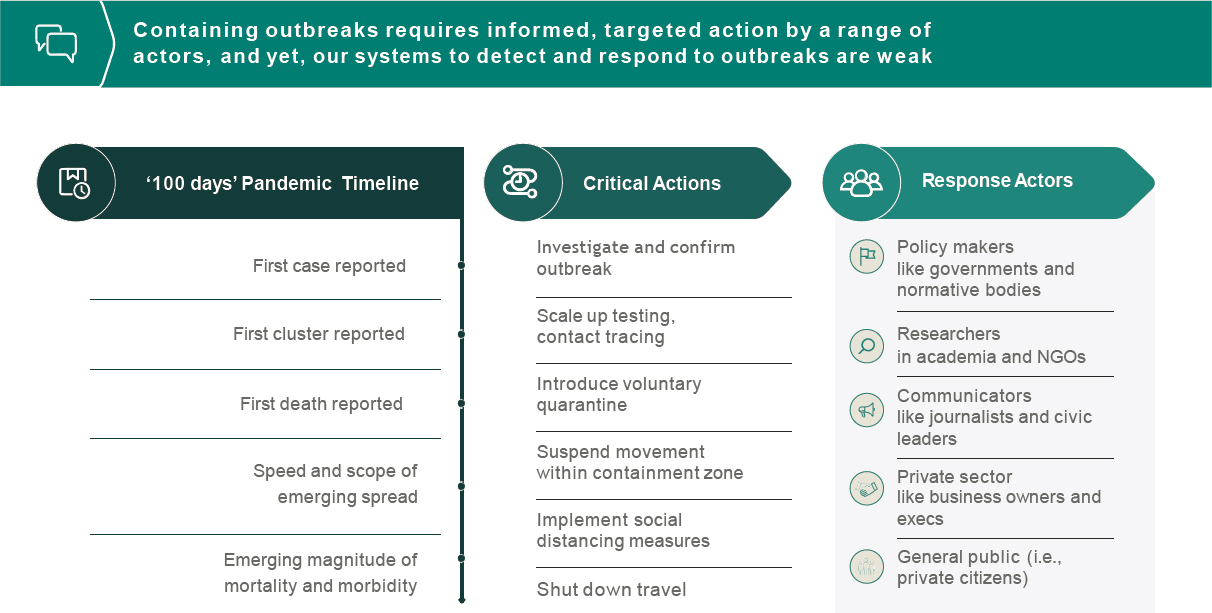

actions taken in the early days can result in many lives saved. However, containing outbreaks requires informed, targeted action by a range of actors, and current systems to detect and respond to outbreaks are weak (see Figure 6-1). To strengthen systems, Quick shared, the Rockefeller Foundation is researching how big data can inform the action platform and rapid response. This involves examining the timetable of an outbreak, identifying critical actions and responses, and determining how to build the data needed to initiate those actions. Steps of the data pathway from source to user could include (1) collecting diverse data inputs; (2) aggregating, coordinating, synthesizing, and sharing data; and (3) leveraging data to drive action. Strengthening this pathway involves generating robust data inputs, harvesting data, making data publicly available in real time, finding ways to navigate governmental efforts to limit data sharing, and incorporating novel sensors, Quick pointed out. Examples of novel sensors include frontline workers in health, veterinary medicine, or forestry services who are able to log test results with a smartphone. Advanced big data management and artificial intelligence are combined with scenario planning to generate action plans.

Quick described a vision for what this hypothetical world-class pandemic action and data sharing platform could yield:

We envision a global platform that will become a leading force for amplifying warning signals and containing the spread of pandemic-potential outbreaks within their first 100 days—delivering the best information to the actors positioned to take action that averts the most devastating human and economic impacts of pandemics.

The health, social, and economic effects of pandemics interrelate. Quick noted that pandemics lead to three categories of deaths: (1) caused directly by the virus, (2) related to a disruption of health services, and (3) connected to economic disruptions. Providing an example of the third category, Quick stated that in the 2008 Great Recession, cancer deaths in Europe and North America increased by 250,000 due to impacts caused by economic disruptions.

Imagining the Impossible

Quick remarked that much about the 2035 scenario he described may seem impossible at this moment. Urging the audience to “imagine the impossible and then make it happen,” he provided three examples of revolutionary global health efforts. The first was smallpox, which Europe and North America eradicated by 1950, Quick pointed out. In 1953, George Brock Chisholm, the first Director-General of the World Health Organization

NOTE: NGO = nongovernmental organization.

SOURCE: Quick presentation, February 25, 2021.

(WHO), proposed global smallpox eradication (Bhattacharya, 2008). However, the World Health Assembly did not vote to do so until 1966. Quick noted that some decision makers thought this was impossible, yet it was accomplished in 1980. Another example is the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which has shifted from being considered terminal to chronic in Europe and North America due to treatment advances, with people living almost as long as those without HIV (Marcus et al., 2020). Quick said that when the head of a major development agency was asked about the possibility of extending this progress to Africa, he responded that it was not possible and that the focus in Africa needed to remain on prevention. A decade later, 10 million people are receiving HIV treatment in Africa. A third example is the 2003 SARS outbreak. Quick stated that in March of that year, the leader of a national infectious disease agency was questioned about eliminating SARS by June, and he replied that he did not think it was feasible, but the outbreak was over by July and has not returned.2

In terms of the COVID-19 pandemic, 1 year ago, many experts thought that by this point, perhaps three or four vaccines with 50 percent efficacy rates might be available, said Quick. However, at the time of the workshop, eight vaccines are in late stages of approval, most of which are more than 70 percent effective, and more than 200 million doses have been administered in 99 countries.3 Quick noted that in each of these cases, people imagined the impossible and then made it happen. He concluded that it is possible to make the world much safer from devastating global pandemics if people commit to making their visions for the future a reality.

COLLABORATIVE EFFORT IN OUTBREAK PREPAREDNESS: FDA’S APPROACH TO ASF

Danielle Sholly and Katherine Huebner, FDA

Huebner reviewed features of ASF and its global impact. She discussed the roles of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and FDA in containing it, and she outlined the activities of FDA’s ASF work group. Sholly discussed key strategies of the FDA ASF Draft Response Plan. Highlighting the complexity of effectively addressing ASF, she provided an overview of the One Health Approach for Disease Preparedness collaborative response framework and the appropriateness of a One Health approach for meeting the threat of infectious diseases.

___________________

2 More information about the 2003 SARS outbreak is available at https://www.cdc.gov/sars/about/fs-sars.html (accessed May 27, 2021).

3 The numbers cited by Quick were accurate as of February 2021. For more updated status of vaccine development, approval, and distribution, see https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines (accessed July 7, 2021).

ASF

A highly contagious viral disease, African swine fever (ASF) results in hemorrhagic fever of both domestic and wild pigs.4 Huebner noted that while ASF spreads rapidly and has high morbidity and mortality rates, it does not affect the health of animals other than swine and is not transmissible to humans. It has never been detected in the United States; if it were introduced, it would have devastating economic impacts for the nation, said Huebner. Disease transmission is influenced by human, animal, and environmental factors. Given that the virus can persist stably in the U.S. environment, it can be transmitted through contaminated materials, such as livestock transport trucks. Feeding pigs uncooked food waste (“swill”) and contaminated meat or carcasses can also result in transmission. An active area of research is the viral transmission of ASF through contaminated manufacturing of animal feeds, spreading the virus via feed mill equipment and the feed itself. Viral vectors include flies, soft ticks, and wildlife reservoirs, such as warthogs and wild boars. No vaccine or treatment is available, although developing novel vaccines is an active area of research. Challenges to these efforts include insufficient knowledge of protection mechanisms and of the antigens involved in this large, complex ASF virus. The primary methods of virus control are preventative biosecurity measures and the depopulation of affected or exposed swine.

Huebner stated that ASF has caused significant pig losses globally. Endemic to sub-Saharan Africa, the disease emerged in Eastern Asia in August 2018, where it expanded uncontrollably and resulted in substantial losses. According to a 2020 World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) report, Asia suffered the greatest impact, with more than 6 million animals lost (OIE, 2020). This accounts for at least 80 percent of the total global losses reported to date. During this period, several countries in Eastern Europe reported the first cases of ASF, which were followed by uncontrolled spread and devastating impacts. While ASF is not a direct threat to human health or human food safety, it is a major threat to animal health and global food security, Huebner explained. For example, mass animal depopulation and subsequent animal disposal present major animal welfare and environmental safety challenges, in addition to the economic impact on farmers and communities who must depopulate their animals. Animal losses also affect the availability of safe sources of protein for human and animal consumption. Modeling predicts that the ASF-related decline in Chinese pork production will result in world pork prices increasing by 17–85 percent (Mason-D’Croz et al., 2020). In addition, unmet

___________________

4 More information about ASF is available at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/swine-disease-information/african-swine-fever/seminar (accessed February 4, 2022).

demands for pork products have translated into price increases for beef and poultry, she noted. Supply chain disruptions can occur for downstream materials derived from pig tissues, such as animal feed and pharmaceutical products, including replacement heart valves and insulin. Given the variety of interconnected impacts of ASF, the multidisciplinary, multisectoral, and multilateral One Health approach—and adequately allocating resources to implement it—are key in controlling further spread and preventing its introduction to the United States, said Huebner.

The U.S. Governmental Response to ASF

As ASF has not yet been detected in the United States, the U.S. government has emphasized prevention, detection, and response planning, Huebner stated. Typically, USDA serves as the lead agency in prevention and surveillance efforts for foreign animal disease prevention. FDA’s focus is the review and approval of potential viral mitigants that meet the definition of a food additive or animal drug. Charged with ensuring a safe animal feed supply, FDA is responsible for all domestic and imported animal food, with the exception of meat, poultry, and processed eggs, all of which primarily fall under the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service. FDA monitors and sets standards for livestock feed and pet food contaminants, approves safe food additives for animal use, and manages a medicated feed program. Under the Swine Health Protection Act,5 USDA is responsible for regulating food waste—such as garbage—that may contain meat products and is fed to swine to ensure it is properly treated to kill disease organisms. Under the Food Safety Modernization Act Preventive Controls for Animal Food Regulation,6 FDA is involved in preventing food safety hazards of food for all animal species and applies primarily to non-farm facilities.

The FDA ASF work group was formed in 2019 to coordinate a disease response plan promoting outbreak preparedness, said Huebner. The group collaborates with USDA, state regulators, and the animal food industry. Additionally, the work group coordinates with FDA’s China Office to establish joint USDA–FDA inspections in Chinese pet food facilities. Comprising representatives from USDA, FDA, the pork and animal food industries, and academia, the Feed Risk Task Force shares ideas and discusses the latest ongoing research. In addition, FDA produces a field bulletin, which alerts staff conducting foreign inspections of appropriate biosecurity measures to

___________________

5 Swine Health Protection Act, Public Law 96-468, § 2, (October 17, 1980), 94, 2229.

6 More information about the Food Safety Modernization Act Preventive Controls for Animal Food regulation can be found at https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernizationact-fsma/fsma-final-rule-preventive-controls-animal-food (accessed April 20, 2021).

take when performing inspections in ASF-positive regions. A major focus of the work group has been developing the FDA ASF Draft Response Plan, Huebner noted.

FDA’s ASF Draft Response

Sholly remarked that the draft response plan created by the FDA ASF work group has been reviewed by FDA and USDA, and final comments are currently being addressed. The group used incident command principles to manage an FDA ASF response. The plan has two main objectives: (1) identify critical activities to detect, respond to, and contain ASF and prevent further spread of the disease in animal food and (2) facilitate swift normalization and distribution of animal food in affected areas. The plan addresses FDA authorities, roles, and resources needed to respond to an ASF outbreak, which is an example of the chain of command and unity of command principles that are part of the incident command program. Sholly explained that this principle clarifies reporting relationships, eliminates confusion, and provides incident managers with a framework for controlling the actions of personnel under their supervision.

The draft response plan contains three key strategies, Sholly outlined. The first is maintaining the ability to provide clean animal food, thus protecting animal health. This involves economic trade in ensuring that products imported into the United States are ASF free. Second, given that ASF can spread from an infected location, such as a farm or feed mill, the plan outlines biosecurity measures for investigators to address during inspections. These measures extend beyond the facility itself to include assessing clothing, vehicles, and equipment, as these are all possible avenues for virus transmission. The plan’s third strategy is to conduct “trace forward” and “trace back” investigations on contaminated animal food or ingredients, which can involve collecting records on those distributed by a particular facility. Sholly noted that in an ASF outbreak, the ability to identify contaminated animal food or ingredients in a timely manner decreases the likelihood that distribution of non-contaminated animal food to animal production facilities and farms in surrounding areas will be disrupted.

In addition to the draft response plan, the FDA ASF work group is involved in public outreach efforts, said Sholly. These include an ASF webpage7 on FDA’s CVM website that provides a high-level overview of ASF with links to information resources and offers transparency on the center’s response to this foreign animal disease. She noted that the webpage states CVM’s commitment to working with sponsors to facilitate the

___________________

7 The FDA ASF webpage can be found at https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/safetyhealth/african-swine-fever (accessed April 20, 2021).

review and approval of products intended to prevent ASF infection and viral spread.

Collaborative Response Framework

Highlighting the importance of a One Health approach in disease outbreak preparation efforts, Sholly described the complexity of a highly contagious virus such as ASF. In the scenario of a group of feral pigs being infected with ASF, a “stamping-out strategy” from USDA’s drafted African Swine Fever Response Plan: The Red Book8 begins with depopulating the animals. The next step of the coordinated response is designating zones around the site where the infected pigs were located. The immediate area around the site is designated the “infected zone,” and a broader ring is a “buffer zone,” which is surrounded by a third, larger “surveillance zone.” These zones are used to inform quarantine and movement control efforts, which may involve multiple agencies from the federal, state, and local levels. Sholly emphasized that features of the location or feral swine population, such as population density and proximity to county or state lines, can increase the complexity of the response efforts exponentially.

In spite of the various resources informing prevention and containment efforts, ASF remains a deadly disease, said Sholly. Cross-sector collaboration to prepare for an outbreak includes tabletop exercises in which representatives from USDA, FDA, and the swine industry work together to develop and review response steps. These exercises familiarize representatives with the reasoning behind each of the plan’s action steps. Representatives identify the parties responsible for carrying out the activities, proactively preparing them with necessary tools to provide a rapid response to an incident. FDA and CVM are working with USDA and state regulators to expand upon existing collaborative efforts in managing an outbreak response. Sholly remarked that disease outbreak preparedness reveals the value of enhanced communication and coordination among different stakeholders.

The Role of One Health in Effective Response

The intersection of human, animal, and environmental health is evident in the efforts required for effective disease outbreak preparedness, Sholly stated. Therefore, FDA uses a One Health approach in addressing the threat of ASF. This includes collaborating with other stakeholders, identifying anticipated challenges specific to ASF, using risk mitigation, considering

___________________

8 The USDA African Swine Fever Response Plan: The Red Book is in draft form and can be found at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/emergency_management/downloads/asf-responseplan.pdf (accessed April 20, 2021).

all potential routes of viral transmission, safely transporting animals and food, and taking biosecurity measures. FDA highly values the ongoing enhancement of collaboration and coordination with other government agencies and industry entities, said Sholly. She continued that although collaborating to implement a One Health approach is not always easy, it increases the likelihood of achieving the best possible outcomes. Much has been learned from past and present human and animal disease outbreaks, such as COVID-19, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (commonly referred to as “mad cow disease”), and porcine epidemic diarrhea. FDA and CVM remain committed to protecting the safety of humans, animals, animal food, and the environment in the face of disease threats and outbreaks, Sholly remarked. The success of any response plan relies on following the science and working as a team to expeditiously resolve an outbreak. Sholly closed with a quote from President Dwight Eisenhower, “In preparing for battle I’ve always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.”

PARADOX OF GLOBAL POLICIES FOR PANDEMIC PREDICTION AND PREVENTION

John Amuasi, Global Health and Infectious Diseases Research Group Kumasi Centre for Collaborative Research—Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana

Amuasi described the increase of national and individual challenges at the intersection of viral pandemic and poverty. He outlined the theory of fundamental causes of health inequalities and the “prevention paradox,” discussed in detail later. Highlighting the role of prediction and prevention policy, Amuasi described the resistance that the prevention paradox can instill in the public and in decision makers. He emphasized the equity issues at play in prevention efforts and called for greater international cross-sector collaboration to create a healthier world.

Intersectionality of Poverty and Pandemic

Amuasi stated that One Health has become particularly topical during the COVID-19 pandemic.9 The burdens of epidemics and pandemics are evident on the global economy, medical health systems, social systems, and general development (WHO, 2018). He noted concerns that COVID-19 may necessitate backtracking in development plans for West

___________________

9 Amuasi referred the audience to the “Policies, Politics, and Pandemics” June 2020 issue of the International Monetary Fund bulletin, Finance and Development, found at https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/06/pdf/fd0620.pdf (accessed April 20, 2021).

African countries that were still recovering from the Ebola epidemic of 2014 to 2016, such as Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. As controlling Ebola required these countries to become familiar with various containment measures, they were able to implement COVID-19 mitigation strategies fairly quickly. However, the “double whammy” of COVID-19 and poverty-related diseases increases the burden for low-income countries, Amuasi described. Guinea is currently experiencing another Ebola outbreak and just recently began vaccination efforts, so it must navigate simultaneous COVID-19 and Ebola vaccination campaigns.

All health crises disproportionately affect the poor due to the impacts of limited availability, accessibility, and affordability of health services and the disruption of existing programs aimed at addressing that lack of services, said Amuasi. When zoonotic disease is layered with poverty, the “double whammy effect” can be both direct and indirect. The severity and mortality of COVID-19 are strongly associated with nutritional status and age. Various neglected tropical diseases and infectious diseases associated with poverty cause immunosuppression, which can increase vulnerability to COVID-19 and other epidemic- and pandemic-prone diseases. Therefore, an individual living in poverty with an underlying health condition and poor nutrition is more prone to a severe or mortal case of COVID-19, experiencing a “direct double whammy,” Amuasi remarked. He elaborated that indirect ramifications of this intersection of poverty and pandemic include disruptions of (1) routine services, such as mass drug administration for helminthiasis, a parasitic worm infection; (2) the manufacturing of drugs, diagnostics, and vaccines for diseases other than the pandemic; and (3) health service delivery activities, such as surgeries for buruli ulcer, lymphatic filariasis, and trachoma.

The Prevention Paradox

Geoffrey Rose described a “prevention paradox” that occurs when population-based prevention health measures—such as compulsory seat-belt laws, alcohol taxes, and mass immunization—bring large benefits to a community but may offer little benefit to nonparticipating individuals (Rose, 1985), Amuasi explained. Rose proposed placing a greater focus on shifting the entire population into a lower-risk category than on moving high-risk individuals into normal range. Given that a large proportion of the population is at moderate risk before intervention, efforts to move this group to low risk contributes to the greatest overall benefit. Amuasi pointed out that several actions made in the public interest during the COVID-19 pandemic have been met with resistance, even from some people who ordinarily make well-informed decisions. He suggested that to comprehend such paradoxes around policies aimed at predicting and preventing pandemics,

one must first understand the nature of health inequalities. Global forces, political priorities, and societal values create fundamental causes of unequal distributions of power, money, and resources (Link and Phelan, 1995). Distribution disparities affect wider environmental influences and, in turn, individual experiences in the areas of economics and employment, education, services, and social, cultural, and physical experiences (Beeston et al., 2014). Inequalities in these wider influences and individual experiences lead to inequalities in the distribution of health and well-being.

The absolute version of the prevention paradox occurs when consensus is achieved by individuals who do not want to participate in a policy measure addressing a population-level concern, said Amuasi. They prefer no population-wide preventive health strategy, viewing their individual benefit as very low and dismissing considerations about the benefit for the overall population (Thompson, 2018). He noted that the protests in the United States, Europe, Asia, and Africa against lockdowns intended to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 are examples of this paradox (Holligan, 2021; Wilson, 2020). Individuals who do not expect to experience personal gain from population-based preventive health measures may prefer not to be subjected to them.

Prediction and Prevention Policy

This prevention paradox can affect pandemic response mass vaccination efforts, said Amuasi. The challenge in working toward COVID-19 herd immunity when a percentage of the population resists being vaccinated underscores the utility of One Health approaches. He stated that pandemic prediction and prevention require integrated animal and human surveillance systems in wildlife, domesticated animals, livestock, animals in cities, and humans in urban and rural areas (Amuasi et al., 2020a). These areas interact in complex ways, and multiple conditions likely contributed to the cross-species transmission of COVID-19—including to humans. Therefore, global policies are needed at all levels of epidemic efforts, Amuasi emphasized. Effective management begins with prediction and detection early in an outbreak (WHO, 2018). Once transmission is detected, containment measures are instituted. As the outbreak amplifies, control and mitigation measures can reduce transmission until the virus is eliminated or eradicated. The policies needed to conduct these multi-level epidemic management efforts are inherently complex. Amuasi highlighted a report from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) that details the relationship between biodiversity and pandemics and proposes cogent solutions (Daszak et al., 2020).

In advocating for prediction and prevention policies, some claims are safe to make, as they have been proven to be accurate, while others require

more information (Aberdeenshire Community Planning Partnership and What Works Scotland, 2018). For example, it is clear that many prevention efforts are cost effective, said Amuasi. Using an “upstream” approach, prevention policies often address the fundamental causes of health inequalities before problems arise, increasing the quality of human life and proving to be cost effective. However, prevention will not necessarily result in cost savings. Amuasi noted a differentiation in the terms “cost-effectiveness” and “cost savings.” Additionally, while evidence supports a shift to prevention, precisely pinpointing efforts that are most cost effective is not possible, he stated.

Paradoxical Challenges to Prevention Efforts

Amuasi shared that his team is conducting seroprevalence field studies in Kumasi and Accra, two cities in Ghana. These studies involve both interviews and blood sample collection. Currently, these efforts are fairly well received due to the COVID-19 pandemic. He stated his expectation that outside a pandemic situation, routine surveillance requiring people to answer questions and provide samples would be met with considerable resistance; many people would likely not understand why they should comply. Complex questions arise, which require multidisciplinary training and involvement to address. Amuasi noted a conundrum that researchers face: the more successful prevention efforts become, the weaker the arguments for policies and investment in population-level interventions may seem. Decision makers and the general public may not intuitively understand the need to spend money on an issue that is not visible. The absence of outbreaks may suggest that the global health of the public no longer requires interventions, which can lead to the resurgence of epidemics. Another challenge in instituting global prediction and prevention policies is variance in value systems, said Amuasi, which can complicate consensus-building in terms of the subpopulations that constitute risk groups and the policies to protect them. For example, as the population in Africa is largely young, African decision makers may not view older people as a priority group, in contrast to countries such as Japan or Switzerland, he remarked. When consensus cannot be reached about the subpopulations that are at risk, it is challenging to agree on which policies to create and enact, Amuasi stated.

Prevention Equity

Amuasi emphasized that an additional challenge in effective prevention efforts is achieving equity. Issues of equity and solidarity are common, caused by access barriers to medical countermeasures, particularly

for low-income countries and nations facing humanitarian emergency, he described. Access inequity increases when vaccine or treatment production is limited. Thus, global prevention policies must be fair and equitable in order to be effective worldwide. On February 24, 2021, Ghana was the first country to receive COVID-19 vaccines through COVAX, a vaccination collaboration that includes Gavi, WHO, CEPI, and the UN Children’s Fund (Mawathe, 2021). Ghana received 600,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, yet its population is approximately 40 million people, said Amuasi. While Ghana will receive future shipments, the COVAX policy assures that participating countries will receive doses for only 20 percent of their populations. Thus, nations are still faced with the challenges of accessing vaccines for the majority of their residents. This demonstrates that even strong global policies may be insufficient for the comprehensive global prevention of outbreaks, Amuasi stated.

Given the prevention paradox, discrepancies in prevention efficacy emerge even within a country. Furthermore, global prevention policy can reinforce inequities; in strengthening it, policy makers must consider whether changes will benefit only select countries and continents, said Amuasi. He highlighted a recommendation in the IPBES Workshop on Biodiversity and Pandemics report:

Launching a high-level intergovernmental council on pandemic prevention that would provide for cooperation among governments and work at the crossroads of the three Rio conventions to: 1) provide policy-relevant scientific information on the emergence of diseases, predict high-risk areas, evaluate economic impact of potential pandemics, highlight research gaps; and 2) coordinate the design of a monitoring framework, and possibly lay the groundwork for an agreement on goals and targets to be met by all partners for implementing the One Health approach (i.e., one that links human health, animal health and environmental sectors). (Daszak et al., 2020, p. 5)

Creating a high-level Intergovernmental Council on Pandemic Prevention would be a complex endeavor, but this is the type of action that is needed, he stated. In a coauthored piece in The Lancet, Amuasi called for establishing a COVID-19 One Health research coalition that would build on the urgency generated by the pandemic to strengthen collaboration with climate change and planetary health communities (Amuasi et al., 2020b). He remarked that the pandemic is a turning point in the history of the world, one the general international community can meet by designing, undertaking, and coordinating supplies and research aimed at promoting a healthy and sustainable planet.

TAKING PANDEMIC THREATS OFF THE TABLE

Rajeev Venkayya, Global Vaccine Business Unit, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd.

Venkayya outlined progress made in outbreak threat awareness and vaccine innovation during the COVID-19 pandemic. He described the prototype pathogen strategy, which could substantially accelerate the time required to take a vaccine candidate to trial for an emerging threat. Outlining additional preclinical, clinical, and manufacturing efforts in preparing vaccine platforms in advance, Venkayya noted steps needed toward greater equity in vaccine access. He described an aspirational goal of shortening the development time for novel virus vaccines to 100 days.

Advances Made During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Venkayya stated that this is an extraordinary time in vaccinology. He commented that over decades of development and innovation, the activity over the past year has never been seen before. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought advances in threat awareness, vaccine platforms, and strategies. Worldwide, eyes have been opened to the magnitude of the threat of pandemics and the art of the possible. COVID-19 has made it clear that pandemics can be caused by viruses other than influenza, and coronaviruses have now matched influenza in terms of threat, said Venkayya. Threat awareness extends to the global community now understanding that animal populations can act as reservoirs in the future. The response to the pandemic has revealed the power of rapid sequence sharing, which continues to be called on as new variants emerge.

Advances during the COVID-19 pandemic include creating new vaccine platforms, Venkayya remarked. Messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is an exciting technological development garnering much attention in the scientific community. In addition to nucleotide-based vaccines, other platforms—including vectored vaccines, subunit approaches, and novel adjuvants—have been developed. He noted that risk is associated with platforms that involve growing viruses in cell culture and taking accurate measurements from assays to determine the quality of product consistency. Given this risk, the gap between the performance of mRNA and other platforms was shorter than may be the case in future pandemics, said Venkayya. Regardless of whether that proves to be the case, a range of platforms suitable for the pandemic threat exists. The discovery of a number of new strategies can speed the time to product availability for large populations. He commented that the most important innovations have involved risk-based approaches to development, performing some actions at risk that typically would be

carried out in sequence. Additionally, innovative approaches have embraced the concept of meeting the threat at its source. For example, Operation Warp Speed established clinical trial sites across the United States in an effort to rapidly demonstrate proof of efficacy in the communities being hardest hit by the pandemic.10

While the COVID-19 pandemic has been met with increased awareness and innovation, it has brought considerable response challenges. The risks involved in the biology of vaccine production, particularly for the non-mRNA vaccines, have emerged, said Venkayya. Inevitably, problems arise in virus growth, cell growth, consistency of the product in process testing, and quality control deviations that delay the arrival of supply. He stated it is not surprising that manufacturers of many COVID-19 vaccines have seen reductions in the expected volumes they are able to produce within a given time frame. Assays have proved challenging, in terms of both the tests used and the clinical assays evaluating immunogenicity in humans, the validation of which involves specific challenges. The complexity of the biology of traditional vaccine manufacturing and the uncertainty involved in growing viruses and cells pose challenges. Venkayya noted this as an area in which the mRNA platform has a distinct advantage.

Prototype Pathogen Strategy

The lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic provide an opportunity to rethink how pandemic preparedness should be approached in the future, Venkayya remarked. He stated an ultimate goal of removing pandemic threats altogether. To this end, CEPI is actively evaluating the concept of prototype pathogens, which represent the characteristics of families of viruses that could emerge as human pathogens. He noted approximately 23 current virus families. While influenza and coronavirus are likely top priorities, research can extend to other families in advance of the next pandemic. This strategy involves identifying a range of tools and even candidate vaccines for virus families, reducing the time between a specific virus emerging as a pandemic threat and candidates being developed and taken to human clinical trials.

Two years before COVID-19, Barney Graham and Nancy Sullivan outlined the exact approach that was later used to develop the first severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccine candidate (Graham and Sullivan, 2018). Venkayya explained that this approach centers on rational vaccine design, which begins with understanding which epitopes are most important on the surface of the virus and for cell entry.

___________________

10 More information about Operation Warp Speed is available at https://www.defense.gov/Explore/Spotlight/Coronavirus/Operation-Warp-Speed (accessed May 27, 2021).

That knowledge is converted to an understanding of the antigens or immunogens that would be most effective in generating a useful neutralizing antibody response to that pathogen. Various platforms that prove to work against the virus are then applied. Testing these in animal models in advance of an epidemic develops understanding of immune correlates of protection. Ideally, vaccine candidates can be evaluated in phase I clinical trials to assess both initial safety and immunogenicity (the generation of an antibody-mediated immune response cell that appears to correlate with a protective response in animals). The ability to carry out this strategy could enable a toolkit of vaccine candidates across multiple families and possibly including multiple candidate vaccines within a given virus family. Venkayya remarked that this could substantially accelerate the timeline to clinical trial material and the availability of vaccines against an emerging pandemic threat.

Preparing the Platforms

A range of vaccine development activities can be performed in parallel to accelerate vaccine timelines, said Venkayya. Preclinical efforts include animal models, which require time to develop and validate. Work on animal models can be performed now, he noted. Toxicity studies can be carried out on the platform itself. For example, in developing the mRNA platform, toxicity studies had been conducted on humans for multiple mRNA vaccine candidates over the past decade, which fostered understanding of toxicity before SARS-CoV-2 emerged. Reproductive and other assessments can be performed to provide further confidence in the safety of vaccine candidates before they are administered to humans in a phase I trial.

Venkayya noted that phase I trials for selected vaccine candidates could take place before a pandemic begins. Clinical trials for safety and immunogenicity need to be easy to mobilize and implement quickly, given the lack of ability to predict exact locations of outbreaks, he remarked. The ability of organizations such as WHO and CEPI to implement clinical trial protocols in an outbreak setting will increase the likelihood of collecting useful data on the vaccine candidate within a matter of weeks. Expansion is also possible in chemistry, manufacturing, and controls, a technical and complex area. The inherent challenge is bringing what works in a laboratory to a commercial scale, said Venkayya. For example, traditional, inactivated, vectored, recombinant vaccines must be manufactured in the range of hundreds or thousands of liters at a time. He remarked that mRNA vaccines have an advantage, as a chemistry-based approach like mRNA does not have the complexities that come with scaling up a viral vaccine or producing virus in a bioreactor. Regardless of whether the platform is mRNA, optimizing scale-up strategies before the threat can be valuable. Venkayya stated that it

may not reduce the time for a vaccine to reach the clinic, but having evidence demonstrating that a product works can shorten the time between data collection and producing a substantial vaccine supply for the world.

Product assays, which include potency assays and other quality control assays used throughout the production process, must be validated and maintained from a quality standpoint to enable confidence in the process. Venkayya added that with vaccines, “the process is the product” due to the lack of effective methods of characterizing the complex biologic that is a traditional vaccine. He pointed out that this is not the case for mRNA. However, the limitations in accurately characterizing traditional vaccines require that a robust and reproducible process that includes appropriate quality control testing throughout be used to ensure consistency. In regard to manufacturing at scale, Venkayya highlighted that bringing new manufacturing facilities online to make products that they have never produced before is extremely complicated. It involves both infrastructure needs and reusable component needs, which are typically varied from company to company and product to product. Changing one element of the manufacturing process necessitates a bridge showing that the attributes of the product are unchanged.

Equity and Manufacturing Expansion

Addressing equity issues before the next pandemic will require increased distributed manufacturing capability and capacity, said Venkayya. An inequitable distribution of the first doses of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine resulted in some regions of the world having early access to substantial quantities, while the vast majority of the world had little to no access. This inequity has fueled consideration of the requirements to expand self-sufficiency in vaccine manufacturing beyond Europe, the United States, and parts of Asia to countries in all regions of the world. Venkayya noted that mRNA vaccines present an opportunity in this area. The complexity of traditional vaccine manufacturing prohibits immediately establishing new manufacturing capability in a country. Developing the workforce skill, capacity, and regulatory experience required for traditional vaccine manufacturing is far more time intensive than building a factory. These surrounding ecosystem elements are important in maintaining high-quality manufacturing. In contrast, chemistry-based mRNA vaccines have greater predictability and less manufacturing complexity. He remarked that mRNA vaccines could be a gateway technology for countries that have never manufactured vaccines, enabling them to “leapfrog” more traditional methods. Venkayya emphasized that he does not suggest that mRNA vaccines will solve all problems. With current technology, mRNA vaccines are not effective for all viruses. Technology may improve to enable greater application,

and at minimum, an mRNA vaccine strategy needs to be developed in preparation for the next pandemic, he said.

A Vision for Future Outbreak Response

Venkayya highlighted an aspirational concept of decreasing the timeline between sequence identification and phase III data submission and availability of vaccine supply to only 100 days.11 With COVID-19, the time from WHO receiving genetic sequencing of the novel coronavirus to the submission of the first phase III data to regulatory authority was slightly over 300 days. Venkayya noted that this is an incredible achievement. He likened the aspiration to speed up vaccine development and shorten this time frame to only 100 days as similar to proclaiming the goal of landing on the moon; no exact plan exists to achieve this goal, but areas are being targeted for innovation that could lead to accomplishing it.

While this goal may be accomplished, it will not be possible to achieve for every pathogen, said Venkayya. For example, no effective HIV vaccine exists. Although developing vaccines for some pathogens is highly challenging, other viruses are more straightforward; for these viruses, the 100-day goal is within closer reach. The United Kingdom is pushing G7 to undertake this target, and CEPI is giving it serious consideration. Venkayya remarked that shortening the vaccine development time will serve as a North Star for CEPI post-COVID-19.

DISCUSSION

Data-Sharing Considerations

Given that improving outbreak response time relies on prediction capability—and that high-quality global data sharing is needed to advance that capability—Daszak asked how the security of data and data users can be protected while simultaneously enabling better access to data. Quick cited ongoing efforts to address the challenge of data security, which involve both technical (e.g., in terms of how data are filtered) and governance solutions. He noted that part of the solution is creating more transparency in how data sharing is overseen, which can enable protections to be built in. Quick remarked that in a pandemic, the right to privacy can interfere with the right to health and life, necessitating certain tradeoffs. Striking the appropriate balance is challenging, however. He remarked that some

___________________

11 An overview of the vaccine development and regulatory approval process can be found at https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/development-approval-process-cber/vaccine-development-101 (accessed July 7, 2021).

of the countries with the most effective COVID-19 responses, including Singapore and South Korea, have mostly managed to protect privacy while saving lives. Quick added that some apps were not protected and noted that ensuring data security can involve balancing conflicting rights, requiring ethical judgments to be made.

Impact of Trade Issues on Data Sharing

Daszak asked Huebner and Sholly about their approach to data sharing with China, as trade issues became a key global political issue.12 Given that addressing ASF requires openness and access to sensitive information on swine production in China that affects global health and trade issues, Daszak asked how they approached acquiring access to data. Furthermore, he queried whether the strategy they used could be scaled up to encourage a broader initiative, such as a global health data network. Huebner replied that she works primarily with the USDA, which has the lead U.S. government role on this issue. In 2020, the United States and China engaged in a phase one trade agreement13 that established purchasing targets for some U.S. commodities, including pork. She noted that FDA and USDA are engaged in implementing the agreement to open up exports of pet food, feed additives, premixed compound feed, and distillers grains to China. Such collaborations around trade can improve the global health network, said Huebner.

U.S. ASF Testing Capacity

A participant asked whether U.S. national and state animal laboratories have the resources needed to ramp up ASF testing. Sholly replied that this falls under USDA’s jurisdiction. USDA has worked with their network of laboratories on testing and testing capacity in case ASF is ever detected in the United States. USDA’s African Swine Fever Response Plan: The Red Book outlines sample collection and diagnostic testing and identifies the National Animal Health Laboratory Network in providing standardization and response testing for any foreign animal diseases. She added that as of April 2020, six U.S. laboratories are approved to test for ASF.

___________________

12 The United States entered a trade war with China in July 2018, when plans were announced to impose tariffs on $450 billion worth of Chinese goods (Swanson, 2018).

13 More information about the U.S.–China phase one trade agreement can be found at https://ustr.gov/phase-one (accessed April 22, 2021).

Equitable Representation in International Planning

Referencing the IPBES panel Amuasi served on, Daszak broached the idea of creating a similar One Health panel. He asked how, if created, the panel might approach ensuring that experts from low- and middle-income countries are given leadership roles. Daszak added that many successful, national-level One Health projects are carried out by low- and middle-income countries. Amuasi suggested looking beyond a panel to forming a high-level council focused on pandemic prevention. This council would reach consensus on priorities and lead countries in establishing mutually agreed-upon targets and goals within the framework of a core agreement. Amuasi reiterated that determining who is at risk, how best to address those risks, and variances in value systems are areas that can be challenging in achieving consensus. He described that to participate in the IPBES process, his request to participate had to be approved by Ghana governmental representatives. In a similar manner, experts serving on an intergovernmental council on epidemic preparedness could function as representatives of their respective countries. This would ensure representation from the Global South, which is particularly needed in addressing the issue of variance in a value system, said Amuasi. For example, while completing a questionnaire for the Lancet-Chatham House Commission, he was tasked with selecting priorities for reducing the impact of climate change. However, he felt the projected priorities were not adequately sensitive to different value systems. The challenge lies in ensuring that a variety of values are represented, he emphasized.

Balancing Vaccine Development Profitability and Access Equity

Daszak noted that Venkayya is a member of the board of CEPI, which takes a global approach to vaccine development, as well as being employed by a for-profit pharmaceutical company. The vision of a broad vaccine platform toolkit would involve companies sharing development strategies, which could put profitability at risk, Daszak pointed out, and asked how for-profit companies will be able to collaboratively share data, frameworks, and access to the ultimate product. How can profitability and access equity be balanced? Venkayya replied that CEPI is well positioned to address this challenge. Having gained experience in Lassa fever, Nipah, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), chikungunya, and Rift Valley fever, CEPI is prepared to move forward with an emphasis on new pandemics. Venkayya described a scenario in which CEPI supports multiple companies and platforms, allocating targets or possibly even vaccine constructs for different companies to put on their platforms. Notably, CEPI would fund this work. As for-profit companies must generate return and continue to fund

innovation, they are unlikely to invest research and development funds into developing a vaccine for a hypothetical threat. Thus, CEPI funding for this work is important, said Venkayya. The concept of governments supporting this type of research and development through an entity such as CEPI is a new innovation, he added. As research and development are highly complex, most governments are not comfortable making those investments. CEPI can play a valuable role in funneling government investments into allocations across companies, Venkayya noted. Furthermore, he posited that companies will feel confident receiving constructs from CEPI, knowing that these constructs have gone through some level of vetting. In this scenario, companies will not have to determine which vaccine construct to use; rather, they will be given the construct and then apply their platform to it.

Valuable Skill Sets in One Health

A student participant earning a master of public health degree asked which skill sets are most needed in the next generation of public health professionals and epidemiologists. Daszak asked the speakers to identify some skills that will enable operationalization of a forward-thinking strategy; the predictive, global, and collaborative vaccine platform; and One Health on-the-ground approaches. Quick replied that a wide variety of skill sets can have an impact, so a student’s particular talents will inform the areas that will be of most benefit to pursue. He added that during the pandemic, the tactical use of videoconferencing has proliferated, but the collaborative benefit of this technology has yet to be optimized. He likened this to a child who knows the mechanics of picking up a phone and talking on it but does not understand the social aspects of how to carry on a phone conversation. Quick said that effective use of videoconferencing will expand collaboration and open possibilities in every area.

Venkayya responded that the pandemic has highlighted the value of contributions from a broad range of backgrounds in developing an effective response. He noted that data science and real-world evidence are two priority areas moving forward. Tightly controlled clinical trials have long been considered the primary means of gathering data, and evolution is needed to further expand data collection efforts, said Venkayya. Data system development in advance of an outbreak will enable early data collection. He remarked that situational awareness with high-fidelity data would be incredibly valuable.

Amuasi studied in both Ghana and the United States, and he earned a minor in development studies and social change. He stated that this education was valuable in shifting his perspective on how the world works and how scientific research should be performed. His work has ranged from understanding snake bites in rural Africa to conducting clinical trials

and seroprevalence studies for COVID-19. Amuasi suggested that students pursue an understanding of the complexity of the world, which includes awareness of what one does not know. Understanding one’s knowledge gaps enables a person to seek out team members with the expertise to fill those gaps. Daszak added that expertise in unusual side issues that may not seem critical can become valuable within a multidisciplinary team. This adds diversity, and all forms of diversity bring value, said Daszak.

Advancing a Proactive Response in a Political Climate

Daszak noted that when a novel disease outbreak occurs, a global response requires governments’ willingness to implement drastic response measures. This took place in China early in the COVID-19 outbreak, but perhaps it might have been possible to put Wuhan on lockdown 1–2 weeks earlier, he surmised. Given the natural tendency to underreact in order to avoid political fallout for instituting severe restrictive measures, Daszak asked about strategies to implement a predictive framework more proactively. Sholly replied that this is a challenging issue requiring tough discussions. Establishing open communication and collaborations before an outbreak can enable prompt interagency discussions once an outbreak occurs. As each agency has individual expertise in a specific area, familiarity with the network of agencies makes it possible to contact the appropriate experts when a need related to a projected disease is identified. She added that this can include state and local entities as well. For example, if an ASF outbreak occurred, swine producers, packing facilities, rendering entities, and veterinarians would need to be made aware. Sholly noted that the tabletop exercises are beneficial in raising awareness of the complexity and severity of the issue for stakeholders. Huebner acknowledged the sensitive nature of this topic, given the trade-off in the benefit of alerting the industry and various stakeholders early on versus the harm that can result with fallout to the response. It can also be difficult to determine the level of threat. For example, a prominent issue surrounding ASF testing and laboratory results is whether a positive test indicates live virus or a fragment of dead virus; for the latter, it is unclear whether this signifies that ASF has been introduced to a new region, said Huebner.

Quick remarked that this is a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” scenario. He recalled that when an outbreak of swine flu occurred in 1976, the director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention called for mass immunization; however, when the virus did not go global, the director was fired.14 He stated that WHO overreacted to the H1N1 outbreak in

___________________

14 More information about the 1976 Swine Flu vaccination program is available from https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/12/1/05-1007_article (accessed April 30, 2021).

2009, declaring it a pandemic and later rescinding that declaration, and that this fueled the organization’s reluctance to declare COVID-19 a pandemic.15 Quick identified three areas for improvement in addressing this tension between underreaction and overreaction. First, better decision tools are needed. While much attention is given to modeling virus behavior, modeling efforts on human behavior are inadequate. Better decision tools could make responses more specific and appropriate to the threat. Second, awareness efforts can better prepare the public, stakeholders, and business community over time. Third, annual rehearsals allow practice during a calm state; rehearsals can increase the likelihood of appropriate decision making during an emergency. Quick noted that when cabinet responsibilities are transferred in the U.S. government, incoming cabinet secretaries are informed about pandemic response, but this can get lost in the delivery of copious information.

Shifting to a Preparation Mindset for Disease X

Daszak noted the difficulty in past years of mobilizing even a fraction of the billions of dollars spent on the COVID-19 response—a disease that has cost trillions of dollars in losses—toward Disease X preparedness.16 He added that “Disease X” is a misunderstood term, as some people erroneously believe that COVID-19 is Disease X, and therefore it is no longer necessary to prepare for it. Daszak asked how to shift the reactive psychology and instill the understanding in governments and taxpayers that funding Disease X preparedness can save billions of dollars and potentially millions of lives. Venkayya stated that pandemic preparedness is about imagination. He described that during his involvement in U.S. government work on pandemic preparedness, discussions of community mitigation strategies such as closing schools were met with resistance. However, the COVID-19 lockdowns extended far beyond what he and his colleagues envisioned. While lockdowns are not the solution to all pandemic-related issues, this example illustrates that in the face of a threat, people will do what is necessary to save lives, said Venkayya. The global trauma caused by the pandemic has stretched the collective imagination. Furthermore, as deadly as COVID-19 has been, it is possible that a Disease X could be even worse. Viruses have been detected with higher lethality or higher transmissibility, so a future novel virus could potentially lead to a worse pandemic than the current one.

___________________

15 More information about the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic is available from https://www.chathamhouse.org/2020/05/coronavirus-public-health-emergency-or-pandemic-does-timing-matter (accessed April 30, 2021).

16 “Disease X” was used in the WHO priority diseases list as a placeholder for “a serious international epidemic” that is currently yet unknown and may occur. For more information, see https://www.who.int/activities/prioritizing-diseases-for-research-and-development-in-emergency-contexts (accessed July 7, 2021).

Venkayya emphasized that while the threat of a future pandemic is present in public awareness, an opportunity exists to access resources needed to launch a preparedness initiative. His ultimate goal is to remove the threat of pandemics altogether. New tools have proven to be effective, and experts are able to map out the requirements to reduce the time to vaccine availability and substantial supply. CEPI is actively working toward implementing this road map. The U.S. Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) continues to work in the space as well. In addition, the European Union is developing the European Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority, which will serve in a similar capacity to BARDA. Furthermore, the African Union is involved in efforts to speed vaccine development. Venkayya stated that this is the first time in history that tools are in place to be able to mitigate a pandemic threat; sustaining momentum could drive substantial change.

Amuasi reflected on the role of the past Ebola outbreak in preparing Africa to contend with COVID-19. He noted that Ebola is more deadly than COVID-19 and that its presence in Africa required systems and capacities to be put in place. Without these response efforts to Ebola, the challenges COVID-19 posed in Africa would likely have been even greater, said Amuasi. The pandemic serves as “the great reset,” an opportunity to do things differently. Newly implemented systems enable advances in research on drugs, vaccines, diagnostics, and the clinical characterization of unknown diseases. Amuasi leads the operational readiness and response work package for the African coaLition for Epidemic Research, Response, and Training (ALERRT), a consortium of 19 partner organizations from 13 African and European countries. ALERRT has instituted measures that allow research to begin as quickly as possible when an epidemic or pandemic occurs anywhere in Africa. These efforts proved successful in addressing outbreaks of monkeypox and plague, and ALERRT is currently active for Ebola, indicating that prevention and response mechanisms can be effective. By instituting these mechanisms fairly early during the COVID-19 pandemic, Africa was able to mitigate the impact. However, funding is needed to capitalize on scientific advances. He remarked that funding allotted toward some of the negative externalities of the pandemic is more than twice that for the fundamental causes. Amuasi continued that left unaddressed, these fundamental causes will continue to put humans at risk of yet another Disease X, a threat that never disappears completely and is ever-present.