4

Increasing Recruitment, Retention, and Advancement of Women of Color in the Tech Industry

Recent research findings provide evidence that increasing diversity in the workforce broadens the talent pool, drives innovation and creativity, and increases market growth (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021; Hewlett et al., 2013; Morgan Stanley, 2018; Pivotal Ventures and McKinsey & Company, 2018). This chapter describes findings from existing research related to women of color in tech, what is known about their unique challenges in industry settings, and social and environmental factors both inside and outside of tech with the potential to increase their recruitment, retention, and advancement. Lack of comprehensive research data specifically related to women of color in tech was a significant challenge for the committee. As a result, this chapter also draws upon related data on women in STEM professions as well as evidence obtained during the committee’s four public information-gathering workshops.

As the number of tech jobs in the U.S. continues to grow, women of color remain a largely untapped pool of intellectual capital and cultural wealth for the tech workforce despite increasing awareness that increased diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) can benefit companies (Hodari et al., 2016; Varma, 2018). Women of color make up 39 percent of the female population in the United States and are projected to be the majority of the U.S. female population by 2060. However, women of color are underrepresented in the tech industry relative to their presence in the overall U.S. workforce. Between 2003 and 2019, women made up more than half of the professional workforce (57 percent) but only about one-quarter (26 percent) of the workforce in computing and mathematical occupations, with little improvement since 2007 (DuBow and Gonzalez, 2020; NCWIT, 2020). In the tech workforce, Black women hold 3 percent of jobs, Latinx women

hold 1 percent, and Native American/Alaskan Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander women hold 0.3 percent, and all women of color are underrepresented in leadership positions in the tech workforce (AnitaB.Org, 2019a; Ashcraft et al., 2016). In Silicon Valley, women represent only 16 percent of the Silicon Valley workforce, and women of color from underrepresented groups represent less than 3 percent (Kapor Center, 2018; Pace, 2018).

Although many companies have been increasing their efforts to improve diversity and inclusion for decades, most have not had success in moving the needle. Some companies have been able to show modest improvements in the number of women of color they recruit, retain, and advance, while others have failed to make progress or have even reversed direction (McKinsey & Company, 2020). Women of color in particular remain grossly underrepresented at all levels of the technology workforce, in technology entrepreneurship, and in venture capital investment (Scott et al., 2018).

CHALLENGES

In the sections that follow, the committee discusses barriers to identifying and understanding challenges faced by women of color in the tech industry.

Data Collection and Disaggregation

In the committee’s examination of published diversity reports from individual companies and existing research literature on women of color in tech, it found very little comprehensive research literature with data across racial/ethnic groups and gender groups and encountered a lack of intersectional research evidence that included the populations discussed in this report. This lack of robust data poses a significant challenge to clearly identifying the specific challenges that women of color may be experiencing within the tech ecosystem and practices that may be effective; however, existing data do provide some insight into policies and interventions that may help to improve the recruitment, retention, and advancement of women of color. Although U.S. companies are already required to disclose numbers of employees categorized by job category, race, and gender to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) in their federal EEO-1 reports, they are not required to release this information to the public. Data from voluntary EEOC disclosures shows large racial disparities in the tech workforce relative to the workforce of the private sector overall (Connor, 2017). Over the past few years, more tech companies have begun to publicly disclose their EEO-1 data—driven largely by pledges to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion as well as pressure from investors. However, some hesitation remains due to fears of legal liability, negative publicity, and the potential for data to be used by competitors to attract talented employees to companies with more diversity (Kerber and Jessop, 2020; McGregor, 2020).

Existing available data, prevalent statistical methods, and considerations for protecting the privacy of women of color often obscure the contexts that shape the experiences of women of color. As discussed in previous chapters, in published data, women are often grouped together without disaggregating by race/ethnicity; however, treating women as a homogeneous group hides important insights on outcomes related to racial and ethnic differences and fosters the notion of a universal gender experience despite evidence that the experiences of women of color within the tech industry are not uniform (Shah, 2020). While the lack of disaggregated data related to women of color is a significant challenge in general, some racial/ethnic groups are less likely to be represented in data; Native Americans, Alaskan natives, native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders—and the populations within those populations—are often absent from datasets. Like other communities of color, these populations are diverse and could benefit from data-driven, culturally contextualized strategies that take their unique contexts into account.

Existing research on intersectionality has shown that challenges for women of color can be greater than that of racism and sexism combined (Crenshaw, 1991; Kvasney et al., 2009; Malcom et al., 1976; Ong et al., 2011). Intersectional data provide a means by which tech companies could understand systemic patterns and how identity characteristics affect the experiences of women of color (Kvasny et al., 2009). Disaggregation of data is a critical step in understanding the cumulative barriers faced by women of color; the potential strategies for successfully increasing the recruitment, retention, and advancement of women of color as a whole; and targeted strategies that may address the specific inequities faced by smaller subgroups (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021). The small number of women of color in the tech sector is often cited as a rationale for grouping all women together; however, disaggregation would provide opportunities to address challenges and improve outcomes across the tech ecosystem. Datasets that are collapsed across race and gender categories in order to use methods of analysis that require more statistical power result in a persistent failure to analyze data related to women of color.

Increasing transparency in data reporting is a critical first step toward creating systems of accountability, understanding the landscape of the tech workforce, and creating opportunities for the tech industry to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion. During its June 2020 workshop, the committee heard from Alice Pawley, associate professor in the School of Engineering Education at Purdue University, on addressing the “small-N” (i.e., small sample size) problem. As a result of the numerical underrepresentation of women of color in tech, their experiences are often understudied and obscured by the practice of combining data for women of color and white women. However, these so-called “small data” can be informative enough to guide industry to actionable solutions and dismantle systems that do not facilitate equity (Metcalf et al., 2018; Pawley, 2020). Alternative methods of analysis that allow for the use of small data, such as the use of qualitative data, can be used to gain insights into how existing systems reinforce

inequity and potential strategies for improving diversity, equity, and inclusion. Without this increased transparency in data reporting, accountability will be impossible. Sharing raw, disaggregated employment data publicly will allow companies to measure, standardize, and meaningfully compare data in ways that have the potential not only to highlight trends across the tech sector, but also to drive competition to improve diversity.

Barriers to Entry

Lack of diversity in employment in the tech sector exacerbates the underutilization of available talent as well as the underrecruitment of new talent (EEOC, 2015). For example, EEOC data show that the workforce composition of the top 75 Silicon Valley tech firms is characterized by lack of gender and racial/ethnic diversity (EEOC, 2015, Table 6). Many companies have pointed to a lack of so-called “qualified” candidates in the tech talent pipeline as an explanation for disproportionately low numbers of women of color in tech; however, criteria for what qualifications are necessary and how qualifications are examined are not always well defined. Data show that the rate of people from underrepresented groups graduating with tech degrees is higher than the rate at which they are being hired by tech companies and do not indicate a supply shortage (EEOC, 2015). This section highlights key barriers to entry into the tech sector faced by women of color.

Bias in Recruiting

There is a common belief that disparities are the result of workers leaving the talent pipeline; however, research suggests that the tech pipeline is only one factor impacting the number of women of color in tech. Other factors such as stereotypes and implicit and unconscious bias can drive underutilization of available talent in the tech workforce (EEOC, 2015) as well as result in fewer opportunities to advance, an unwelcoming organizational structure/culture, and underinvestment in diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021; Hodari et al., 2016). Lack of diversity in recruitment can often be attributed to a lack of diversity in the places where companies recruit new talent—as they often seek out candidates from elite universities where enrollment for underrepresented groups is much lower (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021; Kang and Frankel, 2015; Tiku, 2021). When recruitment departments use college rankings to set priorities for where to recruit and determine resource allocation for recruitment budgets, this gives preference to “elite” universities over universities that produce more graduates from underrepresented groups with tech degrees and works against potential candidates coming to the workforce through alternative pathways. This situation leads to an underinvestment in recruiting candidates of color (Tiku, 2021).

The financial burden required to access some programs created to foster relationships between potential candidates and tech companies may also disproportionately impact women of color who are seeking to enter the tech industry (Nordli, 2019; Tiku, 2021). For example, since 2017, Howard University has partnered with Google to increase access for junior and senior students to industry experience, networking sessions, and opportunities by having them shadow current employees through a three-month program at Google’s campus in Mountain View, California. During the pilot phase of this program Howard University and private donors covered the cost of tuition. Pilot funding also paid for housing and a stipend. However, after the pilot phase in 2017, future cohorts became responsible for the cost of tuition, incidentals, and in some cases housing (Tiku, 2021). In 2018, the program expanded to include Hispanic-serving institutions through the Computing Alliance of Hispanic-Serving Institutions. Upon the arrival of the COVID pandemic, Google offered the program virtually; this was able to expand the program’s reach. In addition to building technical skills, Google has placed more emphasis on building social capital—building the relationships and networks that can provide people with a sense of identity and belonging (Griffin et al., 2021). This type of program can increase opportunities for internships for students and graduates from historically Black colleges and universities, Hispanic-serving institutions, and other minority-serving institutions that many companies are trying to connect with by equipping students with resources and training that can help them persist in tech. It is critical, however, to consider mechanisms needed to address the economic burden for some that limits accessibility (Kang and Frankel, 2015).

Bias in Hiring

The committee found disparities in the number of women of color earning computing degrees and the number entering the tech workforce. Nationally, Asian women are 32 percent of the female tech workforce, Black women are 7 percent, and Latinx women are 5 percent. In Silicon Valley, these numbers are lower, with Black, Latinx, and Native American/Alaskan Native women in particular representing 2 percent or less of the professional workforce there (McAlear et al., 2018).

In data showing the percentage change in the San Francisco area professional workforce from 2007 to 2015, there was growth in the professional workforce for all groups except Black women. Despite positive growth in the professional workforce for Hispanic women, they still represented less than 2 percent of the professional workforce in 2015. Asian women were shown to be the most likely group of women to be hired into the San Francisco area tech sector (Table 4-1), but the least likely to be promoted (Table 4-2). While Asian women have higher representation in hiring than other women of color, they experience disparities in representation related to advancement in the workforce.

TABLE 4-1 Change in San Francisco Bay Area Tech Workforce, 2007 to 2015

| Cohort | Percentage Change in Professional Workforce from 2007 to 2015 | Percentage of Professionals in 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| White men | 31% | 32.3% |

| White women | 10% | 11.5% |

| Black men | 15% | 1.2% |

| Black women | -13% | 0.7% |

| Hispanic men | 32% | 3.091% |

| Hispanic women | 11% | 1.7% |

| Asian men | 46% | 32.3% |

| Asian women | 34% | 15.0% |

Note: The EEOC defines professional as a job that typically (but not always) requires a professional degree or certification. This category does not include first/mid-level managers or executive/senior level managers.

SOURCE: Adapted from Denise Peck Presentation to the Committee on Addressing the Underrepresentation of Women of Color in Tech (May 14, 2020); Gee and Peck (2017).

These data highlight distinct challenges faced by various groups of women of color. Companies can use these data to better target programs and practices for identifying, interviewing, recruiting, retaining, and advancing women of color.

Barriers to Retention and Advancement

Lack of Training, Support, and Promotion

Across science, tech, and engineering fields, women appear to leave tech at a higher rate—in many cases due to lack of advancement. Among Asian and Hispanic/Latinx women, about one-third report feeling that they are not advancing. For Black women this number jumps to nearly half (Hewlett et al., 2014). Lack of advancement was also cited in a report by the National Center for Women and Information Technology (2020), which found that about one-third of Asian and Hispanic/Latinx women and nearly half of Black women felt stalled in their work. Looking at this from the other side, a 2017 report from AnitaB.Org found that one-third of both male and female senior leaders in science, engineering, and tech companies did not believe that women would reach top positions within their companies (AnitaB.org, 2017). As previously discussed in this chapter, small data sets that are specific to women of color can inform industry’s implementation of actionable solutions to address these disparities and can be leveraged to develop best practices.

In 2019, NPower conducted a series of surveys and interviews with alumnae regarding their tech training programs to explore experiences in the workplace, employer inclusion, and other factors that support women of color in tech. Women of color were three times more likely than men to report bias in the form of stereotyping and discrimination, and 24 percent were concerned about gender bias and believed that they were perceived as being less committed or less talented (compared with 1 percent of men). In addition to factors that may cause women of color to leave the tech industry (e.g., lack of advancement and job dissatisfaction), women of color coming from tech training programs may also face challenges that make it harder and unsustainable for them to remain in the work force (e.g., being hired as a contract or part-time worker without benefits) (Shah, 2020; van Nierop, 2020). While training programs may help women of color get in the door and cultivate strategies for success, investing in supports to recruit and retain women of color and providing opportunities for continued professional development and advancement can improve the culture of inclusion (Shah, 2020).

There are many efforts to cultivate high tech skills in women and girls of color both through traditional pathways and alternative pathways (see Chapter 6 for a discussion of alternative pathways). However, evidence suggests that some companies may not be cultivating talent through training of new and existing hires to meet rapidly changing company priorities and needs. This lack of investment in talent development could be a contributing factor to lack of diversity in tech (EEOC, 2015; Hodari et al., 2016; Williams, 2015). Research evidence suggests that systemic barriers within organizations (e.g., lack of mentorship, bias, exclusion from networks of influence, and stereotype bias) can also impede women’s advancement to senior-level positions within their organizations (Skervin, 2015).

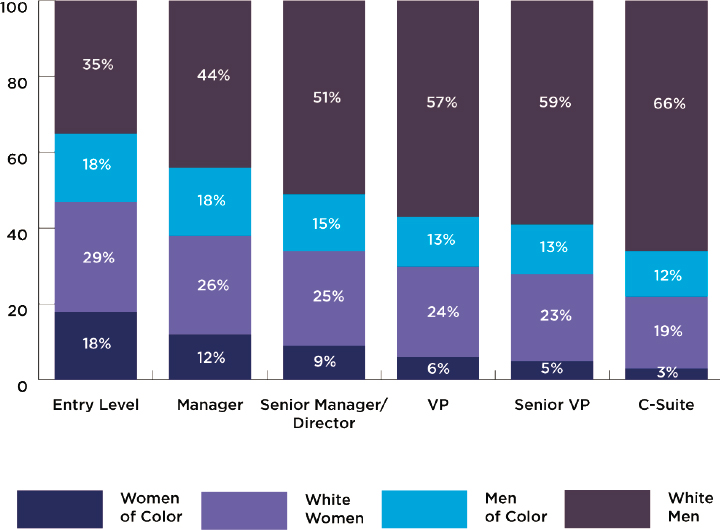

EEOC data—which are collected for all companies with more than 100 employees and disaggregate by job category/level, race, gender, industry, and geography—are useful when examining trends in recruitment, retention, and advancement among women of color. Figure 4-1 shows promotion trends in the U.S. corporate workforce. Although these data are not specific to the tech industry, they reflect promotion trends that also appear in the tech sector and highlight the importance of reporting employment data with women of color disaggregated from white women to have a clearer picture of the employment landscape.

Denise Peck, executive advisor at Ascend Leadership, presented data to the committee at one of its four information-gathering workshops and provided an example of how these data can be used to create a metric for representation she called the executive parity index (EPI). This metric—the ratio of the percentage representation of a company’s executive workforce relative to percentage representation of its entry-level workforce—can be used to examine trends in the number of women of color in the tech workforce over time as well as differences in parity in promotion. Using this calculation, an EPI of greater than 1.0 is above parity (overrepresentation), an EPI of 1.0 is at parity (equal representation), and an EPI of less than 1.0 is below parity (underrepresentation). Looking at data

SOURCE: Adapted from Lean In and McKinsey, 2020.

representing about 260,000 workers in the San Francisco area tech sector (including Silicon Valley), women were shown to have an EPI of 0.68 while men had an EPI of 1.15 based on 2015 data. However, when the same data for women were disaggregated to compare women by race, the EPI for white women was shown to be 1.17 while the EPIs for Black, Hispanic, and Asian women were 0.61, 0.42, and 0.34, respectively (Table 4-2). Black women were seen to have larger gains in EPI than other women of color during this time frame; however, further analysis attributed this larger gain to a loss of Black women at the entry level rather than a significant increase in the number of Black women at the executive level (Gee and Peck, 2017).

Some have hypothesized that as younger generations—who are assumed to be more adapted to diverse and inclusive workplaces—advance in the tech industry to positions of leadership, there will be a positive effect on diversity and inclusion. While it may still be too early to see effects at the executive level, an examination of advancement of women of color at the managerial level can provide insights as to whether this hypothesis is borne out in current data. Gee and Peck (2017) used the management parity index (MPI)—similar to the EPI—to

Table 4-2 San Francisco Area Executive Parity Index, 2015

| Cohort | Executive Parity Index in 2015 |

|---|---|

| White men | 72% above parity |

| White women | 17% above parity |

| Black men | 41% below parity |

| Black women | 39% below parity |

| Hispanic men | 11% below parity |

| Hispanic women | 58% below parity |

| Asian men | 38% below parity |

| Asian women | 66% below parity |

SOURCE: Adapted from Peck (2020); Gee and Peck (2017).

examine trends in advancement from entry-level professional to middle-level manager (Table 4-3). From 2007 to 2015, the MPI for Hispanic, Black, and Asian tech workers remained relatively constant and was lowest for Asian individuals. This finding does not support the prediction that younger generations of the tech workforce are reducing disparities in advancement. In addition, it indicates that efforts over the past decade to increase diversity at the middle-management level have not had a significant impact on reducing disparity. In this same time frame, women have made gains in MPI, suggesting that efforts to improve gender diversity have had some success. White women had the highest MPI (1.45), and while the MPI for Black women (1.28) and Hispanic women (1.13) was above parity, it increased at a lower rate than MPI for white women; the MPI for Asian women remained below parity (0.69). These data show that reductions in gender gaps were greater than for racial gaps, suggesting that race may play a greater role than gender in preventing advancement (Gee and Peck, 2017).

Table 4-3 San Francisco Area Management Parity Index, 2015

| Cohort | Management Parity Index in 2015 |

|---|---|

| White men | 25% above parity |

| White women | 45% above parity |

| Black men | 7% above parity |

| Black women | 28% above parity |

| Hispanic men | 32% above parity |

| Hispanic women | 13% above parity |

| Asian men | 31% below parity |

| Asian women | 31% below parity |

SOURCE: Data from Gee and Peck (2017).

Attrition

As discussed in Chapter 3, research indicates that structural barriers often lead women to leave the technical workplace: inhospitable work culture/unconscious bias, conflict with preferred work style, isolation, supervisory relationships, promotion processes/lack of advancement, and competing life responsibilities (Ashcraft et al., 2016). A survey by Capital One found that only 2 percent of women in tech left as a result of being unhappy with the nature of their work itself (AnitaB.Org, 2019b). In addition, the National Center for Women and Information Technology estimated that the cost of turnover as a result of bias costs U.S. companies $64 billion dollars a year and that 56 percent of mid-career women in technology are leaving their careers as a result of negative experiences (e.g., institutional barriers and gender bias) in the workplace (Ashcraft et al., 2016).

Williams (2015) suggested that patterns of bias that align with these structural barriers may be a key factor driving women from STEM jobs based on the results of a survey of 557 female scientists and interviews with 60 female scientists:

- Two-thirds of the women surveyed and interviewed reported feeling they had to repeatedly prove themselves and having their expertise called into question. For Black women, this number jumped to three-quarters of respondents.

- Women also felt pressure to balance being seen as too feminine with being seen as too masculine. More than half of respondents reporting feeling backlash from behaving in a way that was perceived as too “masculine,” and more than one-third felt pressured to behave in a more feminine way. Being viewed as too feminine often resulted in their competence being questioned, while being viewed as too masculine resulted in them being perceived as aggressive and unlikeable. Black and Latinx women were more likely to be viewed as angry when they deviated from these gender norms.

- Women with children across all racial/ethnic groups felt that their opportunities diminished and their competence was called into question once they had children. They also felt that they had to compete with men who did not have the same level of family/household obligations.

- Seventy-five percent of women felt supported by other women at work, while about 20 percent felt that they had to compete with other women in companies and organizations that were male dominated.

- Isolation was a pattern of bias that seemed to impact Black women and Latinx women in particular. In some cases, this isolation was self-imposed as means of avoiding bias from colleagues—48 percent of Black women and 38 percent of Latinx women reported feeling that engaging with colleagues socially could have a negative impact on perceptions of their

- competence and undermine their authority. In other cases, the isolation was perceived as a result of exclusion by colleagues.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion can be critical for companies seeking to retain talent across age groups, and inclusive workplaces may be especially important for early- and mid-career employees. Many organizations struggle to recruit and retain top talent and experience significant turnover. But despite evidence that employees and executives appear to view inclusion as a business imperative and a key factor in determining corporate culture, the inability to implement and operationalize effective diversity, equity, and inclusion strategies may be driving some of this turnover. In a 2017 survey of 1,300 employees across multiple organizations and industries in the United States, Deloitte found that, across all industries, there was a 32 percent increase from 2014 to 2017 in the number of executives who cited inclusion as a top priority—69 percent considered diversity, equity, and inclusion to be an important issue. Eighty percent of employee respondents indicated that inclusion was a key factor in choosing where to work, and 39 percent said they would leave their current employer for a more inclusive one. Among millennials this number was even higher—over 50 percent of millennials would leave their current employer for a more inclusive organization, and nearly one-third of millennials indicated they had already left a less inclusive workplace for a more inclusive one. Millennials were also more focused on inclusion (rather than only increasing demographic diversity) as a part of overall business strategy. Increased inclusion resulted in higher feelings of engagement and empowerment. Evidence suggests that there is a disparity between the level of inclusion that employees prefer in the workplace and the reality of what they experience—possibly indicating that there is a disconnect between company objectives and how those objectives are translated into policies and practices. With higher turnover in younger age groups, tech companies are likely to see younger employees moving to workplaces where there is more inclusion or leaving industry altogether if disparities continue to be pervasive (Deloitte LLP, 2017).

Inhospitable Organizational Culture

The intersection of social identities, such as gender and race, with professional identities, such as job title or level, plays a role in shaping the culture of a work team. The biases associated with these identities, and the impact that has on influence, can also affect how individuals experience the workplace: who is viewed as having earned their position, who has access to resources, how/whether employees are mentored or sponsored, and who is given opportunities to advance (Ibarra et al., 2010; McClain et al., 2021; Skervin, 2015). Organizational culture—more than individual factors—can be a critical driver of women’s success as well as their ability to advance (AnitaB.org, 2017). Shared norms, values, and practices define the power dynamics within an organization—both who has

influence as well as which types of influence are viewed as effective. Evidence suggests that companies may have more success attracting and retaining women of color in tech by creating organizational cultures in which they are challenged and rewarded for their work, compensated fairly, have adequate peer and mentor support, and are provided with clear pathways for advancement within the organization (AnitaB.Org, 2019a). Inhospitable workplace culture has implications for the success of efforts to recruit, retain, and advance women of color in the tech sector and prevents companies from adequately leveraging the cultures and values of all employees to innovate and develop products and services that mirror the customers they serve (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021).

Research suggests that there are four critical aspects of organizational culture across sectors that foster a culture of inclusivity: inclusive leadership, being able to be ones authentic self, access to networking opportunities, and potential for career advancement (Sherbin and Rashid, 2017). Shah (2020) found that among companies with a reputation for gender inclusion there is often support from senior leadership who advocate for inclusive policies and practices and who make clear that pathways to advancement are available. As previously discussed in this chapter, women of color from all backgrounds are less likely to be promoted into positions of leadership in the tech industry where they would be more empowered to implement policies that foster inclusion in leadership.

Evidence also shows that members of groups that are not equitably represented often feel the need to alter their behavior in order to conform to organizational/professional norms in response to prejudiced work environments (Murphy et al., 2018; NASEM, 2021). As previously noted, the talent pipeline for entry into tech careers is sometimes limited by where employers choose to recruit as well as determinations about what type of employee is believed to be the right fit for an organization’s culture. This has implications for people coming to tech from backgrounds or pathways that are underrepresented (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021). These individuals may feel more pressure to hide parts of their identity to conform or may struggle to find an identity within an environment where they are in the minority, creating an environment that is not designed to help all employees thrive. They may also have fewer opportunities to access broad networks of mentors and sponsors who can help them navigate the workplace (Murphy et al., 2018). Changes in organizational culture can be hindered by biases in recruiting if employees are hired based on how they fit into an existing organizational culture as opposed to what they can add to enhance it (Gee and Peck, 2017).

Although a number of the committee’s findings were not specific to women of color, research evidence suggests that improvements to organizational culture that could benefit women of color have the potential to improve satisfaction for all employees (AnitaB.org, 2017; Shook and Sweet, 2019). A 2019 Deloitte report that surveyed employees across 10 industries found that 67 percent of women

of color felt they needed to downplay parts of their identity at work in order to fit in. All survey participants worked for companies with diversity and inclusion efforts (Deloitte LLP, 2019a). A 2017 report from Deloitte found a disconnect between employees’ desires in terms of organizational culture/structure and that which is being provided by companies. The top three most important cultural aspects named by respondents were an atmosphere where they felt they could be themselves, an atmosphere where they felt they had a purpose and made an impact, and a place where work flexibility (remote work, parental leave, flexible scheduling) was a top priority. Most respondents indicated that they were not looking for organizations where they were surrounded only by people similar to them with similar identities. The most frequently cited reason for leaving (33 percent) was not feeling comfortable being themselves at their organization (Deloitte LLP, 2017; Shah, 2020). Improvements and adjustments to organizational culture (e.g., providing women of color with recognition for leadership, contributions of innovative practices, and sharing of best practices) have the potential to improve group cohesion within organizations, break down barriers among employees, and foster cohesion across diverse groups within companies so that employees from different backgrounds are able to bring their authentic identities to work (Deloitte LLP, 2019a).

PROMISING STRATEGIES AND PRACTICES

Reducing the disparities in recruitment, retention, and advancement experienced by women of color is possible when diversity, equity, and inclusion are elevated as mainstream business imperatives and embedded in organizational culture (McNeely and Fealing, 2018). As a strategic undertaking, diversity, equity, and inclusion need to be resourced, measured, managed, innovated, and rewarded (Box 4-1). This section discusses promising strategies and practices for effecting change within the tech industry.

Prioritization of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion by Organizational Leadership

Data show that gender and racial/ethnic diversity at the executive level is not enough to achieve improved business outcomes on its own; however, organization leadership is a key factor in determining the success of efforts to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion and can improve business outcomes overall (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021; McKinsey & Company, 2018). Companies with more diversity in leadership were also 35 percent more likely to have higher financial returns than the national median in their industry. Companies with diverse leadership teams have been shown to increase profitability relative to peers without diversity in leadership (Morgan Stanley, 2018). A 2015 report by McKinsey &

Company found that for every 10 percent increase in racial/ethnic diversity at the senior-executive level, company earnings increased by 0.8 percent.1

All leaders within an organization play a crucial role in creating an inclusive culture (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021; Hodari et al., 2016). Deloitte (2017) found that, across all generations, survey respondents preferred leadership that demonstrated inclusive behaviors and said this was a factor in how inclusive they felt their workplace was. Commitment from leadership to embrace diversity, equity, and inclusion as a business imperative can lead to improvements in recruitment and retention of top talent, growth of the company’s customer base, and increases in financial returns (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021; Kang and Frankel, 2015; McKinsey & Company, 2015). Although not exclusive to the tech sector, a survey by Hewlett and colleagues (2013) with a nationally representative sample of 1,800 professionals, 40 case studies, and numerous focus groups and interviews found that without diverse leadership, women were 20 percent

___________________

1 This study was not limited to companies in the U.S. tech sector.

less likely to have their ideas supported and people of color were 24 percent less likely. In addition, Shah (2020) found that 28 percent of women had concerns about the lack of women role models within their organization.

A crucial strategy for beginning to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion is the development of metrics to measure progress and embedding strategies throughout organizational culture and the daily experiences of employees (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021; Deloitte LLP, 2017). This includes defining goals for diversity and inclusion, understanding the resources that are necessary to achieve those goals, and creating structures for long-term accountability for meeting goals. As previously mentioned, metrics that are developed to better understand the engagement and experiences of employees can provide valuable insights into whether strategies to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion are effective (e.g., how employees are doing, whether there is high attrition, and why they are staying or leaving).

In recent years, demand for diversity, equity, and inclusion professionals—and chief diversity officers (CDOs) in particular—has increased substantially

across all industries as companies recognize diversity, equity, and inclusion as a priority requiring adequate staffing, funding, and commitment at the highest levels of leadership. Research suggests that there are specific powers and skills that a CDO must have in order to help implement changes that will improve diversity, equity, and inclusion. These include the ability to influence leadership and other contributors at all levels of the business, create metrics to improve accountability, develop business strategies, and achieve concrete business goals (Mallick, 2020). Evidence suggests that the role of CDO is best positioned in senior leadership where they are able to report to (and have the support of) the chief executive officer and are connected to other departments such as human resources, legal, and communications (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021; Mallick, 2020; Tiku, 2020). Adequate resourcing of the CDO position includes having a sufficient budget as well as a team to support the work necessary to drive change and allow employees to connect—including training, strategic planning, assessment of the organizational landscape, improving recruitment practices, and building partnerships across industry (DBP, 2009). The implementation of successful strategies may not occur quickly and may need to be iterative, but with clear metrics, companies can better understand their progress.

Improving Data Collection

As previously noted in this chapter, the committee found that most data related to employment in the tech industry were not disaggregated using an intersectional approach to separate out data for women of color. In order to develop metrics and strategies to improve the representation of women of color in tech, disaggregated data are needed that can highlight potential systemic biases; challenges related to recruitment, retention, and advancement; and opportunities to target promising approaches to increase recruitment, retention, and advancement of women of color.

As more tech companies have begun to increase transparency by making their diversity reports and EEOC data public, a clearer picture of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the tech ecosystem is emerging (Box 4-2). During its May 2020 public workshop, the committee heard from Stephanie Lampkin, chief executive officer of Blendoor, a company using data science, demographic statistics, and modeling to analyze existing documentation such as diversity reports, Securities and Exchange Commission filings, company websites, and aggregated employer reviews and ratings to provide diversity, equity, and inclusion insights. These analyses can help companies better understand the race and gender composition of executive teams; overall workplace diversity; diversity of new hires; and the benefits, programs, initiatives, and investments that individual companies are making focused on diversity, equity, and inclusion. Over time, these data allow companies not only to track their progress, but also to compare progress across industries and establish benchmarks. This kind of data also provides industry

leaders with information necessary to understand the scope of the challenge, develop targeted solutions, and improve their outcomes (AnitaB.org, 2017; Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021; Lampkin, 2020).

Recruiting, Supporting, and Developing Talent

Attracting women to the tech industry requires implementation of practices that foster success and provide opportunities for their professional development. As previously discussed in this chapter, women of color face a number of challenges and systemic barriers as they enter the workforce; however, many of these challenges that negatively impact their experiences (e.g., discrimination, salary disparities, isolation, imposter syndrome, inhospitable organizational culture) persist even as women of color continue to advance in their careers. The committee discusses promising practices for recruiting, supporting, and developing talent at all levels in the sections that follow.

Recruiting and Hiring

Companies can adopt strategies that leverage existing mechanisms for recruiting women of color in order to build organizations that are inclusive from end to end and attract more diverse candidate pools that reflect the customers that businesses serve (Mallick, 2020). Some examples include training diverse recruiting teams in using best practices for interviewing and reducing bias in hiring, having recruiters to partner with professional organizations for women of color (see Chapter 6 for a discussion of alternative pathways and the role professional organizations), recruiting at conferences for women of color, reducing the emphasis on culture fit in the hiring process, using language in job advertisements that avoids more masculine-gendered words (e.g., competitive and assertive), utilizing recruitment tools and software to proactively seek out women of color as potential employees, and giving hiring managers blind resumes.

Women of color who are new to technology or corporate America may not have access to the same types of resources from peers, parents, or friends who help them navigate their roles in industry; there is therefore a need for resources to support them (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021; Shah, 2020). For example, in internship programs, there is often not recognition of the differing needs that interns may have, which is needed to support them during the internship and potentially bring them into the company in the future. For interns who are women of color this could be support for dealing with bias in the workplace, and mentors who can provide guidance and coaching to help them navigate the interview process and other challenges they may face in the workplace.

Partnering with higher education institutions that are successful at retaining women of color in technology and computing majors can also benefit companies by creating opportunities to share best practices for supporting women of color.

At its April 2020 workshop, the committee heard from Gloria Washington, assistant professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at Howard University, who highlighted the importance of symbiotic relationships when building partnerships between industry and higher education institutions. For example, while minority-serving institutions may benefit from having an industry presence on campus (e.g., as guest lecturers or during recruitment efforts), it is important that tech companies understand the unique environment and culture of these institutions and how they allow students to flourish. Institutions of higher education can be a valuable partner to industry by helping to show tech companies how to improve mentorship experiences for students and interns, and increase the opportunities to provide students with exposure to the entrepreneurial spirit of the tech industry (Washington, 2020).

Retention and Advancement

Evidence suggests that increasing the transparency of steps needed to advance in a company can reduce bias in the promotion process. In particular, promotion processes that are well defined with incremental goals can help clarify steps for employees who are seeking to advance as well as give managers a clear understanding of which metrics should be used for promotion and allow them to link advancement to measured performance (AnitaB.org, 2017). Linking advancement to performance provides more opportunities for recognition and can improve employee engagement. In addition, having metrics that track business processes improves data collection by providing companies with additional information that can be measured over time to understand whether strategies and approaches for reducing bias and improving retention and advancement are successful.

One promising model for changing business systems to eliminate bias is an approach developed by Joan Williams: metrics-driven bias interrupters (Williams et al., 2016). These strategies focus on basic business practices and are intended to reduce bias through objective, iterative, and scalable redesign, such as modifying job descriptions in small but significant ways, ensuring that there is equity in high-profile work assignments, defining clear criteria for promotion, and seeking signs of bias in performance evaluations. The bias interrupter model has the following four basic steps:

- Assess: investigate whether and how biases are operating within business processes and identify objective metrics that can measure whether bias exists.

- Implement a bias interrupter: employ an intervention to interrupt biases that have been identified.

- Experiment and measure: determine whether the intervention interrupted bias sufficiently and whether metrics improved.

- Increase interrupter if necessary: increase or modify the interrupter if metrics have not shown sufficient improvement.

Increasing opportunities to equip women of color with coaching and training to help them navigate the tech ecosystem may also increase the likelihood that they persist in tech. Rati Thanawala, founder of the Leadership Academy for Women of Color in Tech—a program under development—presented at the committee’s February 2020 workshop. As part of the development of the academy, Thanawala was exploring the experiences of successful women of color in tech to help identify effective strategies and levers of success. Using these strategies, women of color enrolled in the leadership academy, which would begin in graduate school and continue for three to five years as the women transition to jobs in industry, would receive long-term coaching on strategies for success (e.g., increasing leadership training, developing negotiating skills, understanding career pacing, and raising their professional profile). Thanawala also discussed how partnerships between colleges and universities and the tech industry as well as technology leadership councils help make this type of coaching more widely available by investing in it for women of color. Box 4-3 highlights an example of efforts to increase the number of women in senior and executive roles at IBM.

Employee Resource Groups

Evidence suggests that women of color benefit from peer networks and “counterspaces” (i.e., safe spaces) at educational institutions, in the workplace, within professional societies, and in relationships with mentors, sponsors, and colleagues. Counterspaces are particularly important because they serve as outlets where women of color can vent frustrations, share and validate their experiences, and build positive racial identities (Ong et al., 2018; Solórzano and Tara, 2003). Employee resource groups—sometimes called employee affinity groups—are one example of a counterspace that can play an important role in helping companies to foster a more diverse and inclusive workplace, encourage professional development, and increase a sense of belonging for employees across an organization. Participation in an employee resource group can also provide women of color and other employees with more access and visibility to senior management (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021; Tiku, 2020).

In order for employee resource groups to effect change within organizations, evidence suggests that they should be empowered to push for changes without fear of retribution and should be a complement to rather than a replacement for diversity, equity, and inclusion professionals in leadership positions. Evidence suggests that in some cases, members of employee resource groups are called upon to take on additional responsibilities related to diversity efforts (e.g., serving as brand ambassadors, helping to recruit new employees, and serving on focus groups for policies) (Tiku, 2020); however, these additional responsibilities

are not generally part of an employee’s official job and can create unintended, additional burdens for employees of color. There are strategies for utilizing the strength and experiences of these groups in a way that increases their benefit to members, such as tying leadership of a group to performance review metrics or providing time to employees to participate in one.

Organizational culture also plays a role in the success of employee resource groups (ERGs). They are most successful when there is buy-in from leadership and engagement from other employees. In recent years, some companies have begun to provide additional compensation to leaders of ERGs for their service as a way of recognizing the value they bring to the organization—both in terms of helping foster a culture of belonging as well as helping companies develop deeper insights about the customers they serve (Montañez, 2021; Morris, 2021). When

they are treated as an asset to the business—like other business priorities—these groups can play an important role in helping companies reach organizational goals such as improved recruitment and retention, brand enhancement, training, and professional development (DBP, 2018).

During its May public workshop, the committee heard from Melonie Parker, chief diversity officer at Google, and Bo Young Lee, chief diversity and inclusion officer at Uber. Both presentations provided useful examples of how employee resource groups can help drive organizational change and be an asset to companies. Parker described Google’s 16 employee resource groups, which have 35,000 employees who actively participate in the groups. As part of the onboarding process, these groups include a buddy program to help orient new hires to Google. The groups also assist with product design and help provide insights into community sentiment (Parker, 2020). Lee described Uber’s 12 employee resource groups as being fundamental to its diversity and inclusion efforts. In 2015, two of the groups—one for people of color and one for women—played a key role in raising the need for diversity and inclusion practices at Uber. As Uber has implemented systemic changes aimed at improving diversity and inclusion over the past five years, Lee noted that employee resource groups have continued to be central to the process. Uber’s executive leadership team meets quarterly not only with the chief diversity and inclusion officer, but also with a council of employee resource groups that provide direct feedback to the leadership team (Lee, 2020).

Lockheed Martin also provides a useful case study. The company has employee resource groups and networks, which are voluntary, employee-led groups formed based on various dimensions of diversity including race, ability/disability, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, military/veteran status, age, and sexual orientation. In 2016 the company had 70 employee resource groups encompassing approximately 8,000 members across all business areas. The company considers that these groups provide benefits to both the employees and its business through leadership development, learning and cultural awareness, and increased employee engagement (Lockheed Martin, 2016).

Allyship

Women of color who have strong allies are more likely to feel that they can be their authentic selves at work, have higher job satisfaction, and believe that they have opportunities to advance. Allyship, as defined by Nicole Asong Nfonoyim-Hara, director of diversity programs at the Mayo Clinic, is “when a person of privilege works in solidarity and partnership with a marginalized group of people to help take down the systems that challenge that group’s basic rights, equal access, and ability to thrive in our society” (Dickenson, 2021). While most people who are not from underrepresented groups may believe they are an ally of women or people of color, in reality allyship requires intention and a distinct set of behaviors that have to be learned. In 2019, Deloitte surveyed 3,000 nationally

representative U.S. adults employed full time at companies of 1,000 or more on workplace inclusion and the impact of bias. Results found that most surveyed individuals (92 percent) believed themselves to be allies, yet few addressed bias when they witnessed or experienced it (29 percent) and nearly one-third ignored it (Deloitte LLP, 2019b).

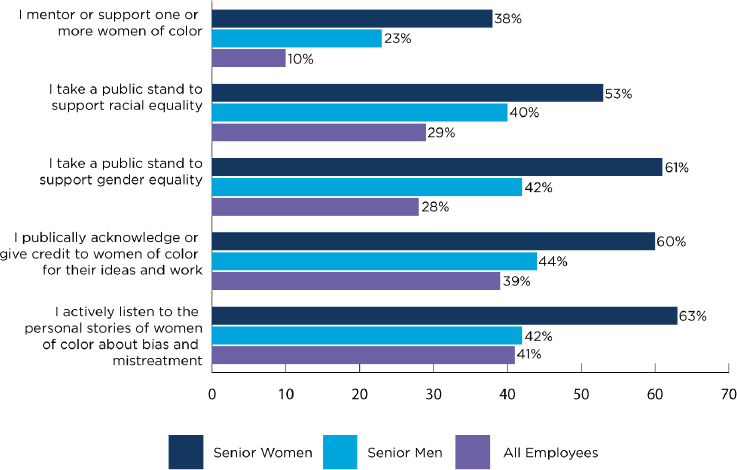

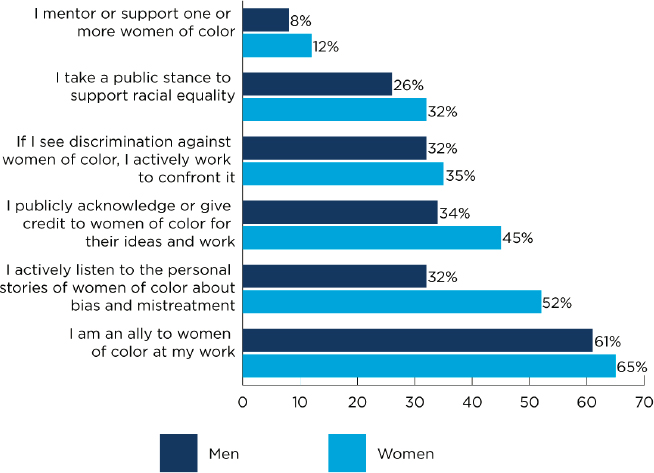

Deloitte’s survey (2019a) also found that 60 percent of respondents felt that bias was present in their workplace, and 83 percent of workers who experienced bias characterized the bias as indirect microaggressions. The top three forms of bias reported were age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Respondents indicated that their performance was negatively impacted by bias even when they were not the one who personally experienced it. Ninety-two percent of respondents in the Deloitte survey felt that they were allies in the workplace, and 73 percent felt comfortable talking about bias in the workplace, yet one-third reported that they ignored bias that they witnessed or experienced. Although not specific to the tech sector, findings from Lean In and McKinsey & Company show similar survey results and also highlight differences in levels of allyship among senior-level men and senior-level women (Figures 4-2 and 4-3).

Bias presents a challenge for organizations that have not developed strategies for addressing bias and increasing allyship, but understanding the intersection of identities increases opportunities for teams to connect with each other and find common ground. Fostering and resourcing practices that create an inclusive

SOURCE: Adapted from Lean In and McKinsey, 2020.

SOURCE: Adapted from Lean In and McKinsey, 2020.

organizational culture is a strategy for reducing bias and allows all employees to demonstrate their value. Evidence suggests that the majority of workers want to be supportive of colleagues and already view themselves as supportive, so the “buy-in” is more a question of using effective strategies than it is about literal buy-in. Efforts to decrease bias improve productivity, morale, well-being, and confidence and can decrease turnover. Organizations should take advantage of this tendency toward allyship to further advance inclusion.

Mentorship

Although women of color can benefit from having effective mentors from many different backgrounds, culturally responsive mentorship prior to and during employment can help women of color establish their identity within tech and navigate pathways both into the tech sector and through levels of advancement within companies (Skervin, 2015). A 2019 National Academies report defined mentorship as “a professional, working alliance in which individuals work together over time to support the personal and professional growth, development, and success of the relational partners through the provision of career and psychosocial support” (NASEM, 2019). Although efforts to mentor women of color

are generally well intentioned, Marisela Martinez-Cola, assistant professor of sociology at Utah State University and a presenter at the committee’s June 2020 workshop, provided the committee with examples of how the attempts at allyship by mentors can often be problematic. Underrepresentation of women of color in the tech industry results in the availability of fewer women with shared, first-hand experiences to serve in this role.

Martinez-Cola described three types of mentors: collectors, nightlights, and allies. “Collectors” may mentor many mentees of color but often limit their interactions to activities and events related to diversity initiatives. They may be well intentioned and may still play a valuable role (e.g., by helping connect mentees with resources), but they may also be inadvertently condescending, negatively affecting the interpersonal dynamic between the mentor and mentee. “Nightlights” have a better understanding of the challenges of people of color, acknowledge systemic racism, and are able to help people of color navigate predominantly white spaces. They also use their privilege and cultural and social capital to make mentees more visible. For example, they may intervene if a woman of color is tokenized or treated as a representative for all women of color. They might also nominate women of color for tasks or roles that are not related to race or difference. Lastly, “allies” are aware of the experiences of their mentees of color and can make meaningful connections in addition to those based on shared lived experiences. They help mentees make connections with important individuals in their field, help them gain standing, and can take criticism and feedback constructively and without damaging the relationship. Mentors who are allies build trust with consistency and humility that affirms their mentee’s belonging (Martinez-Cola, 2020).

The NASEM (2016) report found that the success of mentees who did not have access to culturally responsive mentoring experiences could be impeded as they worked to balance and navigate multiple intersecting identities (e.g., race, culture, gender, technical expertise). This conflict can result in depression, reduced psychological well-being, and lower professional performance. Research suggests that recognition of these intersecting individual identities can influence career development and were a key component of effective mentorship. NASEM (2019) also recommended using inclusive approaches that intentionally consider how culture-based dynamics such as imposter syndrome have the potential to negatively influence mentoring relationships, and understanding how biases and prejudices may affect the relationship between mentors and mentees, specifically for mentorship of individuals from underrepresented groups.

In general, women are less likely than men to have access to informal networks in the workplace that can connect them with opportunities to advance and take on high-profile assignments. Mentorship can position women of color for success in the tech industry, but companies can help improve these outcomes by creating accountability structures to ensure that employees have the support needed to succeed such as formalized mentorship programs that set clear expecta-

tions and define measurable goals (e.g., expected time commitment, identification of outcomes that will be evaluated) for both mentors and mentees and documentation of growth and performance. Research also suggests that it may be beneficial to have access to more than one mentor so that support can be targeted to different types of challenges (Shah, 2020; Skervin, 2015).

Sponsorship

Research suggests that many companies are not cultivating pathways and opportunities for women of color to advance early in their careers and that 56 percent of women in technical professions leave their positions by mid-career. (AnitaB.org, 2017; Hewlett et al., 2008). Formal leadership development with the support of an executive sponsor is a means by which companies improve advancement and growth by improving retention, reducing isolation, and increasing social capital for women of color (AnitaB.org, 2017). The role of a sponsor differs from that of a mentor. Sponsors are advocates who can help fellow employees increase the visibility of their work—both within and outside of their company—by helping them navigate networks and build relationships. A sponsor should be someone who is senior with the ability not only to support a woman of color, but also advocate for access to opportunities to grow and advance. As with mentorship, accountability plays an important role in determining the effectiveness of sponsorship. Evaluation of whether the employee who is being sponsored advances and has opportunities to serve in visible leadership roles is one way in which a sponsor’s success could be evaluated. Intentional strategies for increasing the visibility of women of color is beneficial to companies and increases opportunities for women of color to thrive and advance (AnitaB.org, 2017; Martinez-Cola, 2020; Shah, 2020).

Many women are overmentored and undersponsored. Sponsorship is an especially important part of improving an overall culture of inclusion for women of color. Companies can increase the number of sponsors by training managers on effective strategies for sponsorship. Although not all sponsors of women of color need to be women of color themselves, sponsors should share the core values and goals. For smaller companies, which may have fewer resources or opportunities for advancement, it can be beneficial to connect women with resources in the company as well as opportunities outside the organization (Shah, 2020).

Organizational Culture and Work-Life Balance

In previous discussions of recruitment, retention, and advancement in this chapter, issues related to organizational culture and work-life balance have been highlighted as factors affecting whether women of color persist in tech careers. Intersectionality theory as well as diversity and inclusion concepts are relevant to research on organizational culture and work-life issues. Many organizations are

challenged by the long-term commitment to data collection and sharing required for diversity and inclusion work to be successful and to create sustainable changes in organizational culture.

The committee heard examples from industry at its May 2020 workshop about how data and transparency can help to build a more inclusive workplace. Google’s Chief Diversity Officer, Melonie Parker, described how Google has been working to increase transparency in its data to understand the root of organizational challenges related to diversity and increase accountability of leadership. Parker’s presentation provided a number of examples of steps Google is taking such as

- Looking at data for populations that have historically been denied access or opportunities in the workplace,

- Using an intersectional approach with a focus on equity to understand data and ensure the data are informed by the lived experiences of those groups to avoid creating monolithic practices, and

- Holding summits for Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and Asian women to build community and better understand the needs of each group.

By understanding the experiences of employees, Parker noted that Google aims to tap into a broader potential talent pool, which will help them meet industry demand in coming years (Parker, 2020).

Uber’s Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer, Bo Young Lee, discussed one of Uber’s key organizational changes over the past five years—a commitment to making systemic change within the company to improve strategies for hiring, developing, and promoting talent and to create a more inclusive organizational culture. Diversity and inclusion strategies are guided by key principles. Lee described how cultivating empathy, for example, through storytelling and by shifting language (e.g., using the term people of color vs. minority) is one strategy that Uber has used. A second strategy is to increase transparency and accountability. Uber has invested heavily in data collection and making more data public. Beginning in 2019, the company began enhancing collection of employee demographic data to include eight dimensions of diversity (race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, veteran status, gender status, and caregiver status), plus a proxy question related to economic status during childhood. These dimensions of diversity help the company ensure that the diversity that is found across its enterprise also exists within its corporate ecosystem. In addition, Uber publishes intersectional data in its annual diversity report, which is publicly available. Access to these demographic data is helping to drive accountability on individual teams as well as for the company as a whole.

The third principle is to invest in long-term change. Lee discussed with the committee how sustained change requires a long-term commitment to implementing effective strategies consistently over time. In Uber’s case, she expected

sustained change to take at least four to five years; however, implementing these changes creates an environment that is designed for all employees to thrive and where more employees will be retained (Lee, 2020).

It is important to note that while the examples of data collection and data sharing provided in the presentations heard by the committee are commendable, increased data availability and transparency are only one part of increasing diversity, equity, and inclusion within an organization. Organizational culture and leadership are key drivers of how data are utilized to effect meaningful organizational change. There have been several recent examples of alleged discrimination within a number tech companies—including those who presented to the committee—that highlight challenges that women of color continue to face in corporate tech culture. Allegations of gender and race discrimination in performance evaluation and promotion (Bort, 2020; Duffy, 2020; Reuters, 2018), discrimination in recruitment and hiring (Duffy, 2020; Dwoskin, 2020), racist and misogynistic harassment (Bort, 2020), retaliation (Duffy, 2020), and termination of employment (Allyn, 2020; Duffy, 2020; Gupta and Tulshyan, 2021; Simonite, 2021) have been reported in the news and have prompted congressional inquiries and investigation by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (Bond, 2021; Dwoskin, 2020). The persistence of these types of issues discourages women of color from pursuing or remaining in careers in tech and highlights the progress yet to be made in creating inclusive workplaces. In addition to increasing transparency around the number and demographic makeup of women of color in tech, there is an opportunity to better understand how organizational culture shapes their experiences in the workplace. The experiences of women of color can provide critical insights and inform the development of effective programs and practices as companies work to foster a diverse, inclusive, and equitable culture and long-term organizational transformation.

Research focused on work-life issues in an academic context suggests that work-life issues related to gender have often been prioritized over issues related to race, especially as those issues intersect with gender (NASEM, 2021); however, understanding the work-life preferences of women of color is an important part of understanding how to ensure that both their personal and professional needs are met. Evidence shows that individuals who work in environments where both the organizational culture and leadership support work-life balance are less likely to experience conflict between their work and home life and to view their employer as supportive of work-life balance (NASEM, 2021). The expectation to be available to work at all hours, a lack of flexibility work around family care obligations, and expectations for extensive work travel, for example, are factors that can negatively affect the ability of women of color to advance, feel a sense of job security, or remain with their current employer (Metcalf et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2018; Skervin, 2015). In a 2016 evaluation of top companies for women technologists focused on hiring, retention, and advancement of women in technical roles, flex-time policies were a key differentiator for companies with

above average representation of women in these roles. Eighty-eight percent had opportunities for remote work, 83 percent offered flexible hours (i.e., which hours in the day to work), and 79 percent offered flexible schedules (i.e., number of days per week) (AnitaB.org, 2017). The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the triple burden that many women share—childcare, eldercare, and work (Box 4-4).

Increasing Industry Collaboration

The scope of disparities in the tech workforce became more apparent in 2014 following the disclosure of EEOC data by a number of top tech companies. Examination of disclosures since 2014 shows trends across the tech sector that are consistent with findings at individual companies (Gee and Peck, 2017). The seemingly universal nature of these trends highlights an opportunity for intra- and cross-sector collaboration to address the disparities. Some companies have already begun to work as part of collectives where they can share best practices, aggregate and analyze intersectional data, leverage the insights of industry leaders and employees, and develop metrics to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion in the tech industry (Gee and Peck, 2017).

Investing in Women of Color

There is substantial underrepresentation of women of color in entrepreneurship as well as in venture-invested firms despite the fact that women of color make up 80 percent of women creating small businesses (Kapor Center, 2018). In addition, only 1 percent of venture capitalists are Black women and less than 1 percent are Hispanic women (Huaranca Mendoza, 2020; Kapor Center, 2018). Although limited intersectional data exist on entrepreneurship by women of color, evidence suggests that the number of start-ups founded by women of color is low (McAlear et al., 2018). Similar to the dynamic observed in recruitment in the tech sector, venture capital firms—primarily led by white men—often fund start-ups that they connect to through existing business contacts, the majority of whom are also white men. Carolina Huaranca Mendoza, founder of 1504 Ventures, presented to the committee at its May 2020 workshop and highlighted how difficult it is for people of color to create their own venture funds because of the need to already have sufficient personal wealth to invest, which people of color are less likely to have (Huaranca Mendoza, 2020). Factors such as these result in a repeating pattern of disproportionate exclusion for entrepreneurs of color (Kang and Frankel, 2015; Morgan Stanley, 2018; Women Who Tech, 2020).

Morgan Stanley conducted a survey of 101 investors and 168 bank loan officers to examine the funding gap for female and multicultural entrepreneurs and found a disparity between investors’ perceptions of how much they were investing in women- and minority-owned businesses and how much they were actually investing. Most investors believed their investments to be more equally

distributed than they were in reality (Morgan Stanley, 2018). A survey by Women Who Tech found that 70 percent of investors believed that the size of the pipeline of potential companies to invest in was the cause of disparities, and 56 percent did not believe that access to funding was inequitable (Women Who Tech, 2020). However, in 2020, the median seed round funding for Black women was $125,000 and $200,000 for Latinx women, compared with a national median of $2.5 million dollars (Kapin, 2020). This disconnect between perception and reality plays a role in perpetuating imbalances in investments in women of color, leading to underinvestment in their businesses.

Bias can also play a role in influencing investor decision making related to women- and minority-owned businesses. Responses to the Morgan Stanley (2018) survey indicated that investors were more likely to have a preconception that these businesses perform below market average and are riskier investments. Investors were also less likely to understand ideas for businesses whose products and services targeted customer bases they did not relate to—groups that women and multicultural entrepreneurs are more likely to serve. Investors who were women or from underrepresented groups were more likely than white male investors to review opportunities from women- and minority-owned businesses. The

use of intersectional data would elucidate how these biases compound to impact the success of women of color in acquiring investment.

However, a promising finding from the report shows that the key to achieving greater parity in successfully obtaining investment may be increasing opportunities for women- and minority-owned businesses to meet with potential investors (Morgan Stanley, 2018). Support for women of color as they prepare to take their ideas to investors can include coaching, creating communities of entrepreneurs, and fostering mentor networks. Venture capital companies can also increase racial and gender equity by making themselves more accessible to these communities of entrepreneurs and providing investments in later rounds of funding. In addition, foundations that invest in venture capital funds can help increase the numbers of entrepreneurs who are women of color by creating mandates to identify general partners who are women of color, cultivating emerging managers who are women of color, investing in mission-driven for-profit companies, and investing in programming that targets women of color (Huaranca Mendoza, 2020). Parity in venture investment will allow businesses and start-ups owned by women of color to increase innovation and maximize potential returns in ways that are mutually beneficial to entrepreneurs and investors alike (Catalyze Tech Working Group, 2021; Pivotal Ventures and McKinsey & Company, 2018; Shah, 2020). Disparities in investments in women- and minority-owned businesses are also present in the distribution of public-sector grants such as the U.S. government’s Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer programs, which are intended to fund research, development, and commercialization of technological innovation by small businesses. These programs award approximately $3.5 billion dollars per year in funding to small businesses and are mandated to support participation of women, individuals who are socially or economically disadvantaged,2 and businesses from underrepresented areas. Data reporting the distribution of awards between 2005 and 2017 showed disparities in support for women- and minority-owned businesses. Awards for women rose from 8 percent to 11 percent while awards to socially or economically disadvantaged business owners remained at 8 percent over that time span (Liu and Parilla, 2019). Data disaggregation by race/ethnicity and gender would be beneficial to further understand the scope of disparities in investments in women of color.

Corporate philanthropy can play a role in improving the representation of women of color in tech. However, companies often struggle to know how to make this kind of high-impact philanthropic investment and often rely on self-guided internet searches of research to guide their giving (McKinsey & Company, 2020). But some efforts to coordinate these philanthropic efforts across the tech sector are under way (Box 4-5).

___________________

2 This is defined as a small business that is 51 percent or more owned by one or more persons from any of the following groups: Black Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native American, Asian-Pacific Americans, Asian Americans, and other groups as determined by the Small Business Administration.

Data from the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics suggest that the U.S. economy potentially missed out on $4.4 trillion dollars across all sectors as a result of lack of investment in women and minority businesses (Morgan Stanley, 2018). While this figure does not disaggregate data for the tech sector or for women of color, it suggests that there is a substantial financial loss to the sector related to underinvestment (McAlear et al., 2018). Potential strategies for reducing barriers to entry in the tech sector include increasing the number of women investors and investors of color, setting targets with measurable outcomes for investments in women of color, working to eliminate potential biases in screening of potential investment opportunities, and increasing targeted philanthropic investment in women of color.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite efforts to diversify the tech sector, women of color are disproportionately excluded at all levels of the tech workforce. Increasing the number of women of color in tech will require recruiting more individuals from more diverse sources as well as a culture shift within tech companies that welcomes the perspectives of women of color and recognizes the value they bring to the workforce. Improving the workplace experiences of women of color is equally important as increasing their number. For many women of color—even those who persist and advance in their careers—equity and inclusion issues in the workplace such as discrimination, isolation, and salary disparities continue to present a major ongoing challenge. More robust data collection, including intersectional data and data informed by the experiences of women of color in the workplace, is necessary to develop evidence-based strategies needed to increase diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging.

Women of color are not a monolithic group. Intersectional strategies that explicitly and concretely address the challenges faced by women of color and other groups who encounter multiple, cumulative forms of bias and discrimination are a key component to improving recruitment, retention, and advancement. Many corporate diversity efforts focus on either race or gender rather than taking an intersectional approach, which often leads to the specific needs of women of color remaining unmet. In contrast, when companies set goals and track outcomes by both gender and race, they gain data-driven insights into the barriers women of color face, which allows them to target specific interventions to improve recruitment, retention, and advancement; reduce workplace bias; improve organizational culture; and make targeted investments in women of color. Moreover, these approaches appear to be beneficial to all employees and to the tech sector as a whole.

At the organizational level, leadership buy-in is key to the success of efforts to increase diversity, equity, and inclusion. Leaders with expertise in diversity, equity, and inclusion are particularly valuable assets to organizations trying to