4

Engaging Nonfederal and Private-Sector Partners and Stakeholders in PHEMCE’s Mission

The U.S. medical countermeasure (MCM) enterprise is interconnected, complex, and dynamic. It includes public and private entities that (1) develop and manufacture new and existing MCMs; (2) ensure procurement, storage, and distribution of MCMs; and (3) administer, monitor, and evaluate MCMs. The Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise (PHEMCE) has authority to convene federal entities. However, it must also collaborate closely with nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders, as they are the ultimate implementers of PHEMCE’s mission and develop, manufacture, distribute, and administer the MCMs over which PHEMCE has responsibility. These engagements must support the entire life cycle of MCM preparedness and response, where appropriate, including threat identification, development, manufacturing, deployment, distribution, administration, and evaluation. PHEMCE should provide opportunities for iterative feedback before, during, and after each of stage (Fuchs, 2021).

This report is not the first to call for these important efforts. After the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology called for “a new way of doing business” and stated that “[w]hatever the details of this new management structure, it is essential that any planning activities for this reengineering take place with the full cooperation and participation of the private sector” (PCAST, 2010, p. 57). The 2021 government report National Strategy for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain similarly directed PHEMCE to “coordinate with relevant stakeholder groups to build and strengthen communication, identify and close gaps, and build collaborative solutions that more efficiently leverage government resources and stabilize private-sector investment” (HHS,

2021a, p. 40). It can overcome the complex series of challenges of its critical mission by strengthening these relationships across the enterprise and specifically between federal partners and nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders.

This chapter describes challenges to creating and sustaining these vital partnerships with nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders, along with potential solutions involving transparent two-way communications that engage them in PHEMCE decision making; taking advantage of partnership levers that will enhance PHEMCE’s capacity to meets its mission; and collaborating with global governmental and nongovernmental entities to enhance effectiveness. These analyses and recommendations reflect documents and testimony presented to the committee, its members’ experience, and scientific research on individual and organizational decision-making processes.

INCORPORATING NONFEDERAL AND PRIVATE-SECTOR PARTNERS AND STAKEHOLDERS INTO PHEMCE DECISION MAKING

While the federal PHEMCE partners set policy, secure resources, orchestrate the component functions, and manage programs, this committee recognizes the near complete dependence on nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders. PHEMCE cannot achieve its mission objectives without the successful performance, expertise, knowledge, experience, engagement, and support of these partners and stakeholders, who also have a responsibility to actively understand PHEMCE’s mission and communicate their needs and preferences.

These partners and stakeholders include, but are not limited to, state and local governments, private developers, manufacturers, distributors, public health, community-based organizations, and public and private health care organizations that deliver services in PHEs. The committee recommends that PHEMCE leadership create a standing advisory committee incorporating representatives of these partners and stakeholders, experts with the technical knowledge that its mission demands (e.g., different stakeholders and business leaders with various expertise could weigh in on marketing, MCM research and development, production, distribution, etc.), and ex officio members.

Other advisory committees currently play vital roles on issues within PHEMCE’s remit. For example, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which advises the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC), which advises the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), provide a reliable, enduring conduit for two-way communication to ensure coordination

among the parties. Both are primarily composed of scientific leaders, with a liaison committee with representatives of partner and stakeholder organizations (CDC, 2021; HHS, 2021b). These committees hold public meetings and also serve to broadly communicate their entity’s roles, decisions, and priorities, which also demonstrates the value of the federal mission to important potential champions, such as the public and policy makers (e.g., members of Congress). ACIP and NVAC are effective because they have a clear scope of responsibility and engage in specific, focused tasks and missions (approval and recommendations for vaccines) with those recommendations directed to FDA and CDC. PHEMCE has a broader membership and much broader scope of practice, and PHEMCE decisions are by their nature typically inherently governmental or highly complex. Some decisions must be considered and made in highly classified environments, and it will be helpful to define what exactly such a committee would be able to provide input on for decision making without disclosure issues. Therefore, to be successful, this advisory committee will require appropriate resources, including staffing and leadership, and a clearly defined scope of responsibility.

Additional examples, both domestic and international, establish the relevant precedent. One is the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) National Advisory Committee, which focuses on decisions in the emergency preparedness and response space, similar to PHEMCE, and also can convene related subcommittees and include ex officio members (FEMA, 2021). The National Biodefense Science Board (NBSB) provides expert advice to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) secretary and the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) on public health emergency (PHE) issues. The proposed advisory committee would differ from NBSB in that it would serve PHEMCE, a coordinating body, and advise the numerous PHEMCE member agencies (ASPR, 2020a). Additional precedent also exists in the World Health Organization (WHO) International Health Regulations Emergency Committee, which advises the director-general on when to declare PHEs of international concern (WHO, 2021a). More broadly, WHO uses the Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee for its Health Emergencies Program, which also serves to guide and advise the director-general regarding more broad health issues (WHO, 2021b). The advisory committee should consider short-, mid-, and long-term issues on strategic and operational topics, including managing partnerships for private-sector MCM development, balancing MCM portfolio management, and leveraging existing and new technologies. In addition to regular review of core topics, the advisory committee would address emerging ones, both of its own choosing and raised by PHEMCE leadership. It would pay particular attention to historically problematic topics, such as pivoting to new technologies, ensuring last-mile MCM distribution and allocation realities, incorporating end-user concerns in product develop-

ment and testing, and creating realistic expectations regarding timelines and supplies. The committee must also be flexible enough to convene ad hoc meetings and subcommittees to expand the scope of intellectual capability and the reach of PHEMCE when necessary, as exhibited by the WHO International Health Regulations advisory committee. While an advisory committee cannot make decisions, a mechanism should be put in place to ensure consideration and, where possible, to encourage that PHEMCE’s federal agency members act on recommended decisions.

One major benefit of a properly constituted (diverse, inclusive, and representative) partner and stakeholder advisory committee is improved ability to address health equity issues, a primary PHEMCE goal (see Chapter 2). Two-way communication with state, local, and community partners, who can apprise PHEMCE of the issues, aid it in creating responsive solutions, and help with their execution. Partners and stakeholders in direct contact with vulnerable populations are in the best position to serve these representative roles.

The technical experts on the advisory committee should be scientists and engineers who are broadly informed about cutting-edge research that is either ready for application or could be with suitable investments. They should have expertise across the MCM life cycle, including innovation, testing, manufacturing, distribution, usage, finance, and regulation.

The advisory committee should be engaged in designing, observing, and reviewing the evaluations essential to PHEMCE’s transparency, accountability, performance, and continuous learning. That includes metrics, exercises, audits, annual reviews, and after-action analyses. As discussed in Chapter 3, these evaluations provide triangulating perspective on problematic issues such as appropriate turnover of products in the SNS and the readiness of partners and stakeholders who will play roles in PHEs.

Enhancing Two-Way Communication and Transparency with Nonfederal and Private-Sector Partners, Stakeholders, and the Public

An effective advisory committee affords two-way communication with those represented on it. PHEMCE also needs effective two-way communication with the diverse individuals, organizations, and communities whose trust is essential to its mission. An important issue that needs to be addressed is how to make sure the public will be willing to use MCM as recommended. PHEMCE could do a “perfect” job preparing, responding, and delivering MCM, but that does not mean that the public will comply. Such communication provides the accountability and transparency needed for PHEMCE to understand public needs and develop products that people will use (e.g., without the pushback seen with the COVID-19 vaccines). As discussed in Chapter 2, transparency is an ethical obligation and essential to effectiveness.

PHEMCE can reduce needless conflict by creating a shared understanding with effective, evidence-based communication that is both culturally and linguistically appropriate and tailored to the literacy and understanding of varied population groups. That demonstrates that PHEMCE hears, respects, and understands the concerns, needs, and challenges of its partners, stakeholders, and the public well enough to address its information needs regarding PHEs and plans for meeting them. PHEMCE should be a trusted source of information. PHEMCE must hear their concerns and address their needs, for both information and communication that reflects that strategies and plans have taken inequities into consideration. Engagement with the public needs to respect their right to know and be heard. Effective two-way communication is essential to PHEMCE’s mission but also to overall PHE response.

Two-Way Communication

PHEMCE’s communications require a strategic approach. It must engage groups that vary in their knowledge, experiences, needs, and resources and their trust in PHEMCE and its partners. It must manage media environments rife with misinformation and where complex interactions between where science and politics mix in complex ways. It must convey such challenging content as the following:

- Technical information (e.g., about diseases, weapons of mass destruction [WMDs], and countermeasures);

- Uncertain information that may change with evolving science and circumstance;

- Policies that must balance costs and benefits to different groups;

- Proper interpretations of unintuitive lay observations (e.g., random “clusters” of apparent side effects, exponential processes that grow unexpectedly fast);

- Priorities influenced by classified information that cannot be shared without compromising the public’s security;

- Priorities influenced by proprietary information that must be made transparent without compromising intellectual property; and

- Willful dissemination of misinformation, which valid information must preempt.

To these ends, PHEMCE must create trusted two-way communication channels allowing it listen and speak to these diverse groups. It needs trusted partners who know these groups’ needs and concerns and can tailor trusted messages explaining its responses to them (IOM, 1999; NASEM, 2020; NRC, 2008). Communication content and process must complement

one another, with timely, relevant, comprehensible messages demonstrating that PHEMCE recognizes these diverse groups’ needs (NRC, 1989). Sound communications preempt misinformation, whose effects can be hard to undo (Lewandowsky, 2021; NASEM, 2021a,b; Rathje et al., 2021). Trust must be established prior to a PHE, if the parties are to work collaboratively.

Various models (in person and not) exist for two-way communication in the federal government. For example, FDA created a Voice of the Patient Initiative to understand the realities facing its stakeholders. It included regional meetings on sensitive subjects (e.g., chronic fatigue syndrome, sickle cell disease) designed to hear from people whose voices are normally missing (e.g., patients, providers, caregivers, advocates). These listening sessions provided opportunities to hear life experiences, ask questions about unmet needs, and demonstrate good faith. PHEMCE leadership might consider similar consultations to reduce the risk and appearance of losing touch with the diverse external stakeholders depending on its success. The proposed advisory committee should include such processes. Without them, PHEMCE cannot ensure equity and fairness in its operations.

Transparency as an Obligation

PHEMCE has an obligation to be fair, transparent, and accountable to the public it serves, demonstrating that it treats nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders equitably and has done everything possible to support them during PHEs (see Chapter 2). Without transparency, others may lose trust in PHEMCE’s products, directives, and communications. Without accountability, PHEMCE cannot expect nonfederal partners and stakeholders to work with it. Thus, the federal agency members that comprise PHEMCE must honor promises and contracts, subject to independent evaluations (see Chapter 3).

The committee heard descriptions of major procurement decisions that appeared to violate good business practices, including major investments redirected or terminated without adequate communication or justification and decisions made outside established channels. Such practices undermine the quality of PHEMCE’s work by preventing critical review of products, vendors, and user readiness. They also undermine the legitimacy of PHEMCE’s work by suggesting COI. All of PHEMCE’s federal agency members’ business agreements should be transparent, providing vendors with clear, explicit and stable agreements as required by ethical business practices.

Limits to Transparency

The committee heard evidence suggesting both inappropriate sharing and inappropriate secrecy of sensitive information. The committee under-

stands there can be tension between the demands of transparency and the need to protect information that may compromise national biosecurity or intellectual property. Sharing classified information can aid adversaries. Sharing proprietary information can limit private partners’ willingness and ability to participate. Conversely, failing to share security-related information can deny partners and stakeholders knowledge that is essential to their duties and impair preparations, responses, and coordination.

PHEMCE must develop policies that balance legitimate needs for secrecy with the demands for communication and transparency, in consultation with its partners and stakeholders and informed by practices in other domains (NASEM, 2017). When PHEMCE decisions must rely on restricted data, it should use clear protocols for making and documenting those decisions. Its partners and stakeholders must be made aware of what information has been withheld.

Clarifying Roles and Expectations with Nonfederal and Private-Sector Partners and Stakeholders

A lack of clarity and consistency in priorities and goals can lead to fragile partnerships. PHEMCE must establish clear, consistent roles and expectations in dealings with all nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders engaged with a threat or product. It must clarify how risks are shared, how success is measured, where accountability (and for what) resides, and how the system is sustained. PHEMCE must be a reliable partner, and its business practices must be flexible and adequately prepared to give related industries a chance to pivot their business priorities as needs can quickly shift. It must have orderly processes for revisiting these roles as conditions change, as when manufacturing is relocated, transport systems are disrupted, staff are unavailable, or PHEs are imminent. Given its overall perspective and responsibility, and the diverse perspectives of its members, the advisory committee should be actively involved in developing these processes, specifying performance metrics (see Chapter 2), and evaluating their success (see Chapter 3).

It is critical to engage these entities meaningfully and substantively, particularly during preparedness as opposed to only in PHEs. By building up preparedness capabilities, PHEMCE can, and must, have a much more accountable system for developing and acquiring products amenable to effective use by nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders for PHEs.

As the nation’s MCM coordinating body, it is essential for PHEMCE to ensure sufficient engagement and partnering with these nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders is occurring, with appropriate metrics and evaluation in place to ensure that such partnerships are capable of the agile, adaptable response that is needed in a PHE.

Workforce Alignment and Recruitment

PHEMCE needs a strong industrial base with a trained workforce for producing and distributing MCM, before and during PHEs. All of the federal agencies involved need better ways and means to recruit, train, and retain technical talent. PHEMCE leadership, in consultation with its advisory committee, can ensure the long-term commitment, inside and outside government, to create these capabilities. The National Strategy for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain directs PHEMCE to “coordinate a comprehensive public health supply chain talent and capability study to identify U.S. Government gaps in skilled labor” (HHS, 2021a, p. 54).

PARTNERSHIP LEVERS

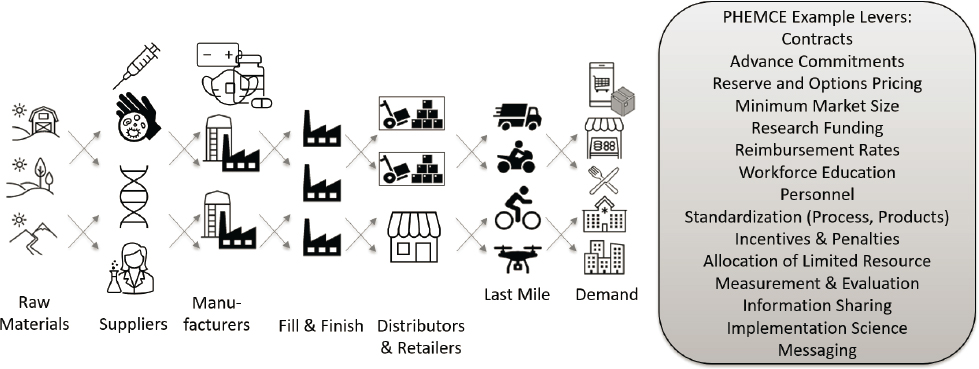

PHEMCE has numerous levers and incentives to create a shared, integrated approach toward the common goal of national preparedness and response, including establishing business practices that attract and sustain high-performing private-sector partners. A second lever is adopting a life cycle approach for strategic and budgetary planning and management (see Chapter 2), ensuring the existence and coordination of all needed elements in MCM readiness. Figure 4-1 depicts such an integrated process. The advisory committee should provide valuable overview and oversight.

The advisory committee that has been recommended is an important start toward understanding the needs, concerns, wishes, and other perspectives from nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders. That understanding can be used to design and choose the right levers to achieve particular actions in partnerships or collaborations.

NOTE: This figure illustrates examples of supply chain actors and partnership levers that can sustain partnerships to develop, produce, procure, transport, and/or administer MCMs.

Contracting

PHEMCE contracting should suit the situation, considering factors such as whether the MCM is new or existing, other markets exist, and the product supply chain is vulnerable to disruptions. PHEMCE has a range of such contract options, and Operation Warp Speed (OWS) demonstrated that contracting can move at/near the speed of science. Here, too, the advisory committee can inform policy and practice about how PHEMCE can establish a world-class acquisition capability commensurate with the demands of the mission.

The committee heard concerns about the need for contracts that would hold through the entire development process for drugs, diagnostics, and devices—contingent on suitable performance. Without such guarantees, potential partners are unlikely to invest their talent and resources. Those guarantees may include advance purchase commitments, sharing risks between the federal government and its external partners, and minimum commitment contracts to bring products to the scale needed for broader market adoptions.

PHEMCE has a history of partnering with federal and private entities for distributing and warehousing products during emergencies. Those arrangements would benefit from transparent, predetermined contract mechanisms enhancing the robustness of these critical supply chain components during PHEs (see Chapter 5).

Risk Sharing

Informed by its advisory committee, PHEMCE should create policies that balance risks wisely among its partners and stakeholders. Private-sector partners should bear some risks while being protected from undue ones. Health systems should be encouraged to take the financial risks of creating MCM surge capacity for PHEs, with the assurance of appropriate reimbursement practices. PHEMCE should engage the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in creating these policies and encourage educational institutions, accrediting bodies, state education agencies, workforce investment boards, and professional societies to invest in programs for expected workforce needs, by projecting the demand for their graduates.

PUBLIC HEALTH SUPPLY CHAINS AND STOCKPILING CONSIDERATIONS

Public health supply chains, including the U.S. Strategic National Stockpile (SNS), are critical to our nation’s preparedness and response. Responsibility for different parts of this—beyond the SNS—but interacting with PHEMCE will need to be determined (e.g., it could fall to PHEMCE to

establish a robust industrial base, a resilient public health supply chain, or a process for updating foundational platform technologies). The National Strategy for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain directs PHEMCE to establish “transformative” business practices to secure the supply chains needed for MCM preparedness (HHS, 2021a). To that end, PHEMCE must specify requirements for the security, staffing, and management of public health supply chains, partnering with the private sector and guided by its advisory committee. PHEMCE leadership should consider lessons learned by large organizations (e.g., Walmart, Amazon, World Food Programme), while recognizing its unique needs (e.g., accepting that some products will never be used). For some products, the described business partnerships will not work, such as MCMs that do not have regular demand or the regular demand is not sufficient to cover the needs of a stockpile. In the former, it may be necessary to continue stocking some products or consider paying for capacity that can be rapidly scaled up within manufacturers or research centers. The National Strategy for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain directs PHEMCE to

develop a transformative overarching business framework and strategy, with a focus on building long-term, end-to-end capabilities that ensure future readiness of the nation’s public health supply chain while prioritizing diverse manufacturing and logistics strategies. This work includes advising on building public health readiness; enhancing engagement with pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries to develop and ensure emergency access to novel MCMs; developing requirements and acquisition processes that ensure new MCMs will meet the needs of the American public (especially those on the front lines in public health and the medical community); and prioritizing a comprehensive approach that maximizes fiscal responsibility through cost-effective strategies by implementing a “planning, programming, budget, evaluation” life cycle framework that harmonizes PHEMCE partner missions focused on MCM preparedness. (HHS, 2021a, p. 38)

U.S. Strategic National Stockpile

The SNS is a critical resource that PHEMCE coordinates (within HHS and in cooperation with other federal partners), including activities such as deployment, distribution, dispensing, and administration. Innovations in how the SNS1 is maintained are a major lever of PHEMCE, and positive

___________________

1 The Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise (PHEMCE) Multi-Year Budget notes, “The primary challenge faced by PHEMCE is the sustainability of the MCM response capabilities and capacities of the SNS built through Project BioShield (PBS). Successful procurement of an MCM obligates SNS to expend additional funding for sustainment. First, SNS faces replenishment requirements upon expiration for products added to the SNS

changes in partnership with nonfederal and private-sector organizations could yield cascading benefits for national preparedness and response. Key stockpiling decisions include what, how much, where, and how to stock; how to allocate limited resources; and how to resupply. The appropriateness and size of a stockpile may also depend on the type of threat (e.g., chemical or radiological threat versus infectious threat with global scale). One possible strategy is having the federal government maintain physical stockpiles while relying on private-sector expertise to manage inventory, especially for products with a short shelf life. Other options include consigned inventory, virtual inventory, and reserved capacity (Coleman et al., 2012). If the business strategy has been tried, root-cause analysis should be performed and/or external experts consulted to identify if it can be used more effectively, to promote the availability of critical resources at times of need. As stated in other documents, the strategies need to be combined with additional resources for the SNS, both financial and human capital (Finkenstadt et al., 2020; Gerstein, 2020).

Whatever approach is used, SNS decisions must be defensible, transparent, and fair (see Chapter 2). The SNS must allow for responsiveness to anticipated threats, sensitivity to relative risks, and equitability, considering key measures, such as mortality, morbidity, equity, and other societal costs. Managers of the SNS should use appropriate methods in projecting demands and supply. The efficient and equitable distribution of scarce resources during the chaos of a PHE will always be challenging. New research from various scholars and groups may illuminate improved ways of enhancing fairness and efficiency of stockpiling and deployment (DeJong et al., 2020; Emanuel et al., 2020; Minnesota Department of Health, 2021).

PHEMCE must improve the SNS, whose limits hampered early response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As noted in Chapter 1, the mandated SNS annual reviews were not submitted after 2016. Months into the pandemic, shortages of PPE, intensive care unit (ICU) medications, ventilators, and test-kit supplies persisted. Other problems related to the SNS have been identified, including stockpiles items without fully considering distribution in the last mile, chronic underfunding, expansion of scope over the years to possibly unrealistic expectations, changes to SNS mission in April 2020, and insufficient planning exercises to uncover potential gaps. Problems have also been documented in investments, as described elsewhere.

___________________

by BARDA through PBS contracts. PBS funding used for initial MCM procurement rarely supports ongoing maintenance and replacement of the products after it is approved by FDA. In the past, the PHEMCE SNS Annual Review recommended tradeoffs when available SNS funds were insufficient to both maintain current capabilities and absorb additional products. These tradeoffs translated to increasing levels of risk across the threat portfolios potentially jeopardizing the nation’s ability to realize the full benefits of prior research and development investments” (emphasis added) (ASPR, 2020b).

A root-cause assessment of SNS failures and limitations should be a high priority, if PHEMCE is to avoid repeating history. The National Strategy for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain recommended that any SNS expansion be reviewed and validated through PHEMCE (HHS, 2021a).

GLOBAL CONSIDERATIONS AND SYNERGIES

While PHEMCE has long strived to engage international partners, particularly through the Global Health Security Initiative following the 2015–2016 Ebola outbreaks in West Africa (ASPR, 2017), new entities were catalyzed and others expanded their efforts. MCM preparedness is a global effort with partners that include the European Union and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, Gavi, UNICEF, and the American Red Cross. PHEMCE should do the following:

- formalize and expand coordination with these global entities;

- look for lessons in the practices and experiences of bodies with different goals, capabilities, and national and organizational cultures; different countries perceive threats differently, calling for improved surveillance, information sharing, and development of new tools, including point-of-care diagnostics and policies regarding emergency deployment of assets related to personnel and stockpile sharing;

- use the situational awareness from the collaboration to inform its understanding of the vulnerability and resilience of public health supply chains, as seen throughout the COVID-19 pandemic;

- seek and share best practices; and

- create the personal and organizational ties and trust needed in PHEs; its perspective and experience should also be included for international negotiations of critical trade deals, treaties, etc., as many of these are key to resilient supply chains for critical MCM.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

PHEMCE needs a comprehensive approach to integrating nonfederal and private-sector partners, stakeholders, and communities across its activities. That approach should include a strong overarching advisory committee, respectful two-way communications, clearly delineated roles, and collaboration with global entities with similar missions.

RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATION 6. ESTABLISH AN ADVISORY COMMITTEE OF NONFEDERAL AND PRIVATE-SECTOR PARTNERS AND STAKEHOLDERS.

PHEMCE should develop and maintain an advisory committee of representative medical countermeasure partners and stakeholders to both garner their expertise and ensure transparency in PHEMCE activities.

- The advisory committee’s input should be sought and considered seriously in all major decisions and actions by PHEMCE regarding the development and delivery of MCMs.

- The advisory committee should balance external partners and threat portfolios to ensure the right combination of threat-specific expertise and other relevant expertise on critical issues like supply chain and stockpiling.

- The advisory committee should help aid PHEMCE in its communication with nonfederal partners, stakeholders, and the public. The meetings should be conducted with appropriate transparency, considering both public discussions and assurances of confidentiality among members, in order to accomplish the intent of this objective.

RECOMMENDATION 7. IMPLEMENT TRANSPARENT COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES.

PHEMCE should establish mechanisms for transparent communications across the government and with nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders and the public.

Functions and responsibilities of these mechanisms would include the following:

- Coordinating internal and external communications within PHEMCE and between PHEMCE and nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders and the public to ensure trusted two-way communication channels with all partners and the provision of dependable, actionable information.

- Balancing the tension between transparency and national security or proprietary concerns.

- Involving the public to assist in driving messages that resonate with various communities; political messaging should be discouraged. These communications need to be culturally and linguistically appropriate and tailored to the literacy and understanding of multiple population groups.

- Providing advance information of MCM priorities for public and private sectors, as well as the public itself, prior to and during public health emergencies.

RECOMMENDATION 8. ESTABLISH CLEAR AUTHORITIES, ROLES, AND RESPONSIBILITIES FOR EXTERNAL PARTNERSHIPS.

PHEMCE should develop, document, and clearly define authority, roles, and responsibilities among federal and nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders, whose perspectives on the status and role of partnerships are vital to the medical countermeasure mission.

PHEMCE should regularly assess the perspectives of federal and nonfederal and private-sector partners and stakeholders on the state of the partnerships vital to the MCM mission.

RECOMMENDATION 9. CONDUCT A ROOT-CAUSE ASSESSMENT OF COVID-19 U.S. STRATEGIC NATIONAL STOCKPILE (SNS)SPECIFIC LESSONS LEARNED.

PHEMCE should commission an independent, evidence-based root-cause assessment of lessons learned from COVID-19 and other past public health emergencies specific to the SNS.

This should include assessing the intended purpose and value of the SNS annual reviews and whether they drove findings and recommendations that were tied to meaningful outcome measures, budget justifications, and accountability across PHEMCE. Any SNS expansion should be reviewed and validated through PHEMCE. This assessment should be conducted in the context of the end-to-end mission elements and the life cycle management of the SNS assets and explicitly coupled with a prospective risk assessment.

RECOMMENDATION 10. WORK SYNERGISTICALLY WITH RELEVANT GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS.

PHEMCE should work synergistically with global and other national-level organizations with relevant missions and goals to benefit from their experiences and leverage global expertise and resources as appropriate.

REFERENCES

ASPR (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response). 2017. International Partnerships Branch. https://www.phe.gov/about/OPP/dihs/Pages/partnerships.aspx#GHSI (accessed September 15, 2021).

ASPR. 2020a. About the National Biodefense Board. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/legal/boards/nbsb/Pages/about.aspx (accessed October 11, 2021).

ASPR. 2020b. Future challenges. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/mcm/phemce/phemcemyb/FY2018-2022/Pages/future-challenges.aspx (accessed October 15, 2021).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2021. ACIP committee members. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/members/index.html (accessed September 15, 2021).

Coleman, C. N., C. Hrdina, R. Casagrande, K. D. Cliffer, M. K. Mansoura, S. Nystrom, R. Hatchett, J. J. Caro, A. R. Knebel, K. S. Wallace, and S. A. Adams. 2012. User-managed inventory: An approach to forward-deployment of urgently needed medical countermeasures for mass-casualty and terrorism incidents. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 6(4):408–414.

DeJong, C., A. H. Chen, and B. Lo. 2020. An ethical framework for allocating scarce inpatient medications for COVID-19 in the U.S. JAMA 323(23):2367–2368.

Emanuel, E., G. Persad, R. Upshur, B. Thome, M. Parker, A. Glickman, C. Zhang, C. Boyle, M. Smith, and J. Phillips. 2020. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine 382(21):2049–2055.

FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). 2021. National Advisory Committee. https://www.fema.gov/about/offices/national-advisory-council (accessed October 6, 2021).

Finkenstadt, D. J., R. Handfield, and P. Guinto. 2020. Why the U.S. still has a severe shortage of medical supplies. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/09/why-the-u-s-still-has-a-severe-shortage-of-medical-supplies (accessed October 25, 2021).

Fuchs, E. R. H. 2021. What a national technology strategy is—and why the United States needs one. Issues in Science and Technology. https://issues.org/national-technology-strategy-agency-fuchs (accessed October 25, 2021).

Gerstein, D. 2020. The strategic national stockpile and COVID-19: Rethinking the stockpile. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/testimonies/CTA500/CTA530-1/RAND_CTA530-1.pdf (accessed October 11, 2021).

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2021a. National strategy for a resilient public health supply chain. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/legal/Documents/National-Strategy-for-Resilient-Public-Health-Supply-Chain.pdf (accessed September 3, 2021)

HHS. 2021b. NVAC members. https://www.hhs.gov/vaccines/nvac/members/index.html (accessed September 15, 2021).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1999. Toward environmental justice: Research, education, and health policy needs. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Lewandowsky, S. 2021. Climate change disinformation and how to combat it. Annual Review of Public Health 42:1–21.

Minnesota Department of Health. 2021. Ethical framework for allocation of monoclonal antibodies during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/coronavirus/hcp/mabethical.pdf (accessed October 14, 2021).

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. Dual use research of concern in the life sciences: Current issues and controversies. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2020. Framework for equitable allocation of COVID-19 vaccine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2021a. Strategies for building confidence in the COVID-19 vaccines. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2021b. Understanding and communicating about COVID-19 vaccine efficacy, effectiveness, and equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC (National Research Council). 1989. Improving risk communication. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NRC. 2008. Public participation in environmental assessment and decision making. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

PCAST (President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology). 2010. Report to the president on reengineering the influenza vaccine production enterprise to meet the challenges of pandemic influenza. Executive Office of the President of the United States. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/PCAST-Influenza-Vaccinology-Report.pdf (accessed October 5, 2021).

Rathje, S., J. J. Van Bavel, and S. van der Linden. 2021. Out-group animosity drives engagement on social media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118(26):9.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2021a. IHR Emergency Committee. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/international-health-regulations/eventreporting-and-review/ihr-emergency-committee (accessed October 6, 2021).

WHO. 2021b. Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee for the WHO Health Emergencies Programme [IOAC]. https://www.who.int/groups/independent-oversight-and-advisory-committee (accessed October 6, 2021).