The second workshop in this series, held May 17, 2021, featured four presentations about dietary assessment in children 2 to 5 years of age and included a question and answer session between the speakers and workshop series planning committee members as well as a panel discussion with the audience. Presentation topics included methods to collect dietary intake information during early childhood, choosing an appropriate dietary assessment method for research conducted during early childhood, lessons from the Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study, and lessons from other disciplines with regard to analyzing data recorded from multiple informants.

Lisa Harnack, professor in the School of Public Health at the University of Minnesota and member of the workshop series planning committee, prefaced the presentations with comments about the early childhood life stage. As children 2 to 5 years of age experience rapid growth, continued cognitive development, and evolution in fine and gross motor skills, she explained that they are also establishing food preferences. Frequent meals and snacks of relatively small portion size are common, Harnack added, and “eating jags” may occur where children eat a limited set of foods for a few weeks and then switch to another limited set of foods. Dietary assessment for young children relies on reporting from the caregiver(s) most responsible for their feeding, she said, adding that the caregiver may not necessarily be a parent. More than one-half of U.S. children 2 to 4 years of age are in some sort of child care arrangement on a regular basis (e.g., receiving care from day care centers, preschools, in-home providers) (Laughlin, 2013), she said, which can present challenges to gathering information about young children’s dietary intakes.

METHODS FOR DIETARY ASSESSMENT IN YOUNG CHILDREN

Susan L. Johnson, professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, discussed methods to assess dietary intake in young children. One of several key considerations for dietary assessment during this life stage, she began, is that at least one proxy reporter must provide data because young children are unable to provide complete and accurate information. Many children eat only one meal at home with family members on a regular basis, especially on weekdays, Johnson pointed out, which is why more than one proxy reporter may be needed. Another consideration has to do with literacy; beyond general reading and writing abilities, Johnson explained that food literacy, health literacy, and technology literacy can influence reporting of young children’s dietary intake. Accessibility of the reporting methodology for reporters with special needs is another consideration, she continued, as is the language of the reporter (e.g., a translator, if involved, may not fully convey to the assessment administrator everything the reporter says). Johnson noted that all of these considerations influence the costs of dietary assessment in young children.

According to Johnson, an important first step in dietary assessment planning is to determine the question of interest. Such potential focus areas include

- total intakes and its variability by weekday or weekend;

- intakes in specific settings such as home versus child care;

- intakes of specific nutrients and the contributions from foods compared with supplements;

- eating behaviors such as neophobia or selective eating; or

- a comparison of social and environmental influences on intake, such as for foods eaten away from home versus foods prepared and eaten at home.

In addition, intakes among groups or by individuals may be of particular interest, or concordance in intakes between peers or between caregiver and child.

The ideal dietary assessment method is one with enough specificity to answer the question of interest, Johnson said, and is best aligned with the study’s population, time line, and budget. In her view, the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Dietary Assessment Primer is “an incredibly important” resource to review before embarking on a dietary assessment effort.1 It provides information about various types of assessment tools along with

___________________

1 See https://dietassessmentprimer.cancer.gov (accessed December 27, 2021).

their strengths and limitations as well as considerations for data capture, processing, and analysis.

Next, Johnson elaborated on several traditional dietary assessment methods and provided examples of parents’ perspectives on some of the methods. She first discussed 24-hour recalls, in which a reporter provides a child’s total dietary intake for a single day. A trained interviewer may ask questions of the reporter to gather these data, or the reporter may provide questions via an automated self-administered technology. Strengths of the 24-hour recall method include the option for translation into different languages; suitability for use with large cohorts; public availability of a least a basic version of a web-based, automated, self-administered recall system (NCI’s Automated Self-Administered 24-hour [ASA24] Dietary Assessment Tool); and the ability to combine it with other assessment methods. On the other hand, Johnson said in contrast, it may be challenging for a reporter to recall every item a child consumed during the recall period, particularly if multiple caregivers provided different meals during that time. Parents who used the ASA24 liked that the recall system collected information only once daily and appreciated its structure and repetition. Nonetheless, they also found it challenging because they were not always aware of everything a child had eaten away from home, and portion sizes for the known items relied on their best “guesstimate” (Bekelman et al., 2021).

Johnson moved on to discuss food diaries, which also attempt to capture a child’s total daily intake but rely less on memory because reporters are instructed to record the information when the food is consumed. Although food diaries can be completed with or without the assistance of technology, options such as texting and photos can improve the completeness of participants’ records. Johnson cautioned that food diaries may put a higher burden on participants compared with other tools and that it can be difficult to obtain a complete record when multiple caregivers are responsible for meals during the period of interest. The Study to Explore Early Development (SEED) chose food diaries instead of 24-hour dietary recalls, she recounted, because participating caregivers were interested in nutrition and highly motivated to capture their children’s dietary intakes (DiGuiseppi et al., 2016). The SEED protocol included quality control for both data collection and data entry, resulting in usable records for 1,120 participants (a 70 percent response rate), 9 percent of which were excluded for lack of more than 1 day of data or recording of implausible intakes.

The third method is food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) or checklists, which Johnson commended for their relatively low participant burden, suitability for large cohorts, adaptability to specific research questions or topics, and ability to be combined with other assessment methods. The drawbacks of FFQs are susceptibility to recall bias, demand on cognitive load, lower accuracy for individual intakes, and limited information about diet quality.

Johnson described a fourth type, which she characterized as being alternative or in development. One example of this alternative type of dietary assessment is food photography, which is well suited for populations literate in health, food, and technology and allows investigators to estimate how much of the serving portion was actually consumed based on before-and-after photos of items in a meal. This method is expensive, she admitted, because it requires data storage and substantial staff time to send participants reminders and follow-up communications and leaves data gaps if participants forget to take a photo during an eating occasion. She recalled her team’s experience using food photography for the Healthy Environments Study, which aimed to develop an interactive, technology-based family intervention to promote healthy lifestyles and weight outcomes for young children in both Head Start and family settings (Bellows et al., 2018). This approach allowed investigators to examine nutrient intake, diet quality, and concordance of parent and child meal timing and foods served.

Direct observation is another alternative approach, Johnson said in concluding her review of dietary assessment methods. Direct observation is tightly controlled and conducted in either real time or with recordings, which she said can yield information about dietary behavior while eliminating some of the “noise and messiness” of other data protocols. This method also calls for substantial staff training, she pointed out, which can become expensive. Johnson referenced an intervention using choice architecture to alter children’s menus in restaurants as an example of how this approach could be used (Ferrante et al., 2022).

CHOOSING AN APPROPRIATE DIETARY ASSESSMENT METHOD FOR RESEARCH CONDUCTED IN EARLY CHILDHOOD

Linda Van Horn, professor and chief of the Nutrition Division in the Department of Preventive Medicine at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, provided guidance for matching a research study’s design with an appropriate method for dietary assessment in young children. She echoed Johnson’s comments about feasibility considerations for assessing young children’s dietary intakes in a research study context and added life course implications to the list. Because many studies enroll participants early in life and follow them for an extended time, she encouraged consideration of types of data that are especially valuable for longitudinal purposes and evaluating a trajectory over time. In contrast, research in clinical settings require consideration of possible limitations in time with patients and constraints related to access of standardized electronic health records.

Van Horn pointed to the 2020 U.S. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) as exemplifying the paucity of available data using standard-

ized and validated dietary assessment methods in young children. Because this DGAC report informed development of the 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (Dietary Guidelines), which for the first time included guidance for infants and children from birth to 2 years of age, it shined a light on the relatively scarce data for that age group as well as for children 2 to 5 years of age. Insufficient evidence prevented the committee from drawing meaningful conclusions for most of the scientific questions it was charged to address about early childhood, she explained, which she called an “aha” moment for research stakeholders.

Despite the 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines call to action to “make every bite count” and its sentiment that it is never too early or too late to start eating healthy, Van Horn pointed out that most of the U.S. population does not consume a diet aligned with the Dietary Guidelines (FNS, 2021; data from the What We Eat in America database). Narrowing in on data for children 2 to 19 years of age, she highlighted low intakes of total vegetables, greens and beans, and seafood and plant protein, as well as increased intakes of added sugars (DGAC, 2020) and decreased intakes of total dairy (Bowman et al., 2018) over the past one to two decades. Van Horn emphasized the importance of these data and their health implications as further rationale to prioritize standardized assessment of children’s nutrient, food, and food group intakes over time.

Van Horn provided examples of recent research involving assessment of dietary and lifestyle factors in children and the need to consider parental influences on health outcomes during childhood and beyond. Based on the current literature review of childhood cardiovascular health (CVH) and adult cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), Van Horn reported that low birthweight, childhood body mass index (BMI), rate of weight gain in early childhood, and adult BMI were better predictors of future coronary heart disease than single time-point BMI measures (Krefman et al., 2021; Pool et al., 2021). Furthermore, she continued, one cohort found that parental CVH is the strongest predictor of a child’s CVH (Allen et al., 2020), and a recent systematic review illustrating three hypothetical life course models for CVD development underscored that CVD risk is likely cumulative and systematic over the life course (Pool et al., 2021). That review also examined literature on childhood risk factors and their associations with adult CVD, demonstrating, Van Horn added, that significant gaps remain in understanding how certain childhood health and behaviors, especially related to dietary quality over the life course, translate to risk of adult CVD.

Next, Van Horn highlighted research examining maternal influences on child CVH. She first pointed to a recent cohort study reporting that better maternal health at week 28 of gestation was significantly associated with better offspring CVH at ages 10 to 14 years (Perak et al., 2021). She added that a randomized clinical trial under way, called Keeping Ideal CVH

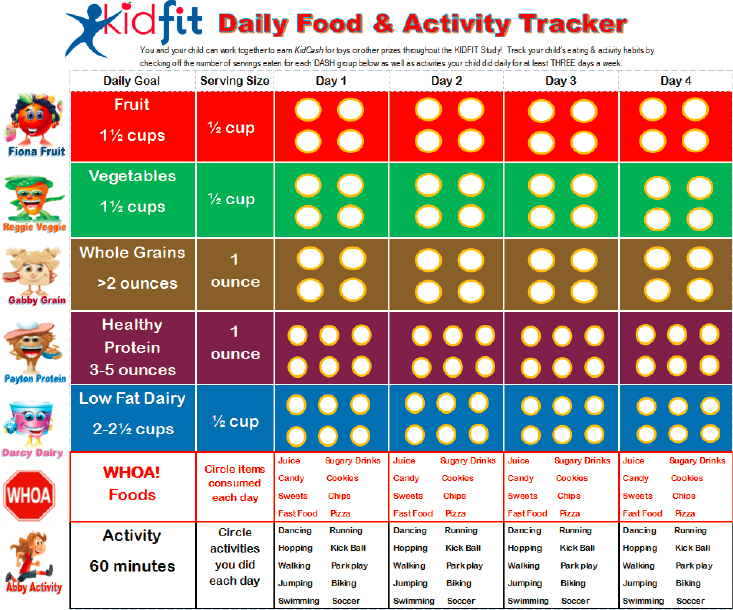

Family Intervention Trial (KIDFIT), involved a dietary intervention in 3- to 5-year-old children of mothers who were overweight and obese during pregnancy. KIDFIT is examining whether a DASH dietary intervention during pregnancy and perpetuated during childhood (along with other healthy habits such as adequate physical activity and sleep) improves trajectories of weight and chronic disease risk. The diet component uses a simple checkoff tracker that allows both the child and the mother to indicate adherence to the recommended DASH-type diet (see Figure 3-1).

Turning to the topic of precision nutrition, Van Horn reiterated the value of collecting longitudinal data on dietary intake—along with biomarkers—starting at birth in order to advance the field. Clinical assessments are one approach to capturing such data, she said, highlighting a recent statement that reviews rapid diet assessment screening tools for cardiovascular disease risk reduction in clinical settings (Vadiveloo et al., 2020). Although primarily focused on screening tools intended for use in adults, the statement rates these options from having the least to having the

SOURCE: Presented by Linda Van Horn, May 17, 2021.

most time-intensive questions. Van Horn suggested that this information could be used to tailor questionnaires so they can be used in a health care setting to capture young children’s dietary intakes in a quick, simplified way. The long-term goal, she said to conclude her remarks, is to reduce the trajectory toward obesity by encouraging adherence to the Dietary Guidelines starting at birth, and thereby improve cardiovascular health and overall health throughout the life course.

LESSONS FROM THE FEEDING INFANTS AND TODDLERS STUDY

Andrea Anater, senior public health nutrition researcher at Research Triangle Institute (RTI) International and adjunct professor of nutrition at the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, echoed previous comments about the critical value of accurately assessing dietary intake for understanding influences on eating patterns and assessing relationships between diet and health outcomes. Anater’s presentation described approaches to assessing the intake of food and dietary supplements in the Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study (FITS), a prominent source of data on food and nutrient intake and related lifestyle behaviors among infants, toddlers, and preschoolers in the United States.

FITS has surveyed nearly 10,000 caregivers across three time periods (2002, 2008, and 2016), Anater said, during which slight modifications in study objectives occurred. Although the study’s primary objective of assessing food and nutrient intake during early childhood has been consistent, she recounted expansions in the age range of children examined, the modifiable risk factors explored, and the special subpopulations included (e.g., participants in the Special Supplemental Nutrition program for Women, Infants, and Children [WIC]).

Anater reviewed the study design, methods, and key outcomes of interest in the most recent (2016) wave of FITS (Anater et al., 2018). As a large nationwide study, FITS was designed to account for low respondent burden, cost-effectiveness, and ease of use. Participants consisted of randomly sampled English- and/or Spanish-speaking caregivers of children 0 to 48 months of age in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. To facilitate comparisons with data from the two earlier waves of the study, investigators included 12 age group sample size targets to align with key developmental stages and WIC participation targets for each. Because respondents were more likely to be white, less likely to be Hispanic, and more highly educated than U.S. households with children younger than 4 years of age, she said that the sample was calibrated and weighted to help reduce this potential selection bias and better reflect the U.S. population. Key outcomes included

- usual intakes of nutrients and energy;

- food, beverage, and supplement sources of energy and nutrients;

- food consumption patterns;

- meal and snack patterns;

- major and minor food groups’ contributions to intake of calories and nutrients;

- comparison of energy intake to estimated energy requirements; and

- trends in intake patterns across the three study periods.

FITS investigators opted to use the 24-hour dietary recall method, which Anater explained was expected to meet the study’s need for a cost-effective, relatively low respondent burden method that could obtain sufficiently detailed data to examine outcomes of interest. Proxy reporters completed the recalls in a protocol that Anater said was similar to the protocol used in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) with proxy reporters for children younger than 5 years of age. Respondents were recruited by phone or online and completed an initial interview about their own and their child’s characteristics, feeding practices, screen use, physical activity, and sleep habits, after which they received a package of materials by mail to assist with the 24-hour recall.

Certified dietary interviewers phoned respondents to ask about the child’s eating behaviors and conducted the recall in the enhanced Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) with the Dietary Supplement Assessment Module (DSAM). Interviewers were equipped with a list of toddler food products that were in the marketplace during FITS 2016 but not included in the NDSR. This list was for the interviewers’ reference only, Anater clarified, to help them prompt respondents for brand information or other details about toddler-specific foods. Twenty-five percent of respondents completed a second 24-hour recall with DSAM 7 days later to reduce measurement error and eliminate within-person variation, which Anater said enabled estimation of usual nutrient intake.

FITS 2016 also included improvements to the 24-hour dietary recall in order to reflect changes in the food landscape between 2008 and 2016, improve the accuracy of dietary data reported, and evaluate specific questions of interest. Overestimation of amounts consumed is a common issue when parents serve as proxy reporters, Anater noted, adding that respondents were reminded throughout the recall to report only the food that the child consumed rather than all foods offered. Interviewers prompted respondants using specific lists of the most commonly consumed and frequently forgotten foods, along with additional details about food types (e.g., 100 percent fruit juice diluted with water); they also asked about the characteristics of interest to the FITS investigators (e.g., organic, consumed from a pouch). Improvements were also made to the food model booklet

that was mailed to respondents prior to conducting the recall to reflect current products and serving utensils for children 0 to 48 months of age.

Anater described the materials that respondents received by mail prior to completing the 24-hour dietary recalls. Intended to assist respondents with reporting accuracy, the materials included a 12-inch paper ruler to help estimate the thickness of foods, a plastic measuring cup with instructions for measuring the volume of the child’s most frequently used cup, and two items that were included in both English and Spanish: a visual aid booklet and a form to capture foods fed to the child by other adults.

The visual aid booklet included actual-size drawings of eating utensils and multiple sizes of drinking cups, pouches, plates, and bowls, as well as images of those plates and bowls containing various amounts and shapes of foods. Market research informed the 2016 version of the visual aid booklet, she added, so that it reflected widely available and commonly purchased sizes of infant and toddler foods, beverages, and serving vessels.

Describing the form for reporting foods fed by other adults, Anater explained that proxy reporters were instructed to complete it as they were able, based on information about the types, amounts, and eating occasions for foods and beverages provided by other caregivers. If FITS investigators determined that follow-up was required to clarify questionable data or collect missing data, they had 10 attempts to contact the nonproxy caregiver by phone or email before expiring the case. Anater noted a few cases where FITS investigators phoned nonproxy caregivers to complete the child’s recall but said that was a rare occurrence because of the significant time burden.

Anater provided more details about the NDSR database. With more than 18,000 foods, including brand-name products, and more than 163 nutrients, nutrient ratios, and food components, as well as serving counts for food groups, she said that the database’s foods and nutrient values are regularly updated to reflect the dynamic landscape of infant and toddler food and beverage products. FITS investigators also added several hundred brand-name infant and toddler food products to the 2016 study’s food and nutrient database prior to conducting the 24-hour recalls, she said, to reflect consumption habits and products available at that time. When a reported food was missing from the database, the FITS team resolved it with recipe calculations from ingredients and nutrient information on labels. In 2016, the dietary recalls resulted in the reporting of 4,623 unique foods and the addition of 351 new foods and 243 user recipes to the database.

The FITS 2016 24-hour recall protocol also queried respondents about the child’s intake of dietary supplements, including multivitamins, vitamins, and minerals; prescription vitamins or minerals; fiber supplements; and over-the-counter antacids. Anater reported that interviewers captured the product’s type, dosage, and frequency of use in the previous

24 hours. Participants were asked to gather dietary supplement product containers to facilitate accurate reporting, but if the container was not available during the interview the DSAM database defaulted to a closely matched generic product. For reported products that were not listed in the DSAM, Anater said that participants were asked to provide the name, ingredients, serving size quantity, and serving size unit to help the FITS team create a record for it.

In her summary of the FITS 2016 methodology, Anater briefly commented on the 24-hour recall’s extensive quality assurance and quality control procedures. For instance, the recalls were assessed for missing foods and reports of consumption of unrealistic quantities for foods or supplements. A record was considered complete if (1) no more than one unknown snack eating occasion was reported, and (2) basic information was provided for a meal or a food, so that the most commonly consumed food in that category could be imputed and an age-appropriate portion size assigned.

Anater outlined five summary points, first emphasizing that the evolving food and beverage market landscape calls for flexibility in keeping the food database used in dietary assessment research updated. She then highlighted the importance of having robust, flexible, and updated tools to improve respondents’ portion size reporting, which she called one of the biggest challenges for dietary assessment in young children. Strategies to improve portion size estimates are also important, she said, referencing the FITS example of additional prompts built into the 24-hour recall protocol to remind respondents to report only the foods actually consumed. Anater pointed out the importance of following systematic methods to maximize the quality of information obtained from multiple caregivers who feed the child. Lastly, Anater called for multiple levels of quality control to be executed throughout the data collection process in order to provide constant feedback.

LESSONS FROM OTHER DISCIPLINES: ANALYSIS OF DATA RECORDED FROM MULTIPLE INFORMANTS

Nicholas Horton, Beitzel Professor of Technology and Society (Statistics and Data Science) at Amherst College, discussed the analysis of data recorded from multiple informants and its relevance for dietary assessment in young children.

Beginning with an overview about analyzing multiple informant reports,2 Horton echoed prior speakers’ comments that multiple reports are often collected in studies of children because the children themselves

___________________

2 Multiple informant reports come from various sources and may include a parent as a proxy for a child, peers, teachers, caregivers, or trained observers.

are not reliable reporters. Discordance is expected when collecting data from multiple informants, he pointed out, noting that a lack of discordance would preclude the need to collect the (redundant) information. Horton highlighted two sources of discordance: random measurement error and the idea that each informant is tapping into different aspects of the underlying construct. In the second case, he elaborated, the potential existence of different measures warrants caution when combining data from the informants. Another important issue with analyzing multiple informant reports is that missing data are common and even expected because the measures collected are for others beyond those being directly queried. Data may be missing by design, as when investigators choose to not collect certain measures, or data may be missing by chance, such as when a reporter was too busy to take a photo of a meal in a study using food photography. Horton underscored the importance of careful analysis of data from multiple informants, joking that the inherent challenges of analyzing data from multiple informants provide job security for statisticians.

Horton next described two common analytical approaches to using information from multiple sources and explained why he does not believe that either approach adequately addresses the potential bias resulting from missing data. One approach is to pool the data, which he described as relatively simplistic but problematic for several reasons. One problem is that the optimal algorithm for combining reports depends on the type of measurement error present, which he said is typically unknown. A second problem is that pooling leads to loss of information about source-specific effects. As an example, Horton said that if the information provided by a child care provider differs from the information provided by the parent, it is desirable to try to correct for the discrepancies, but those discrepancies will not be apparent if the data are pooled. Third, he continued, pooling does not allow examination of differences and risk factor effects across sources, and fourth, many pooling algorithms are not clearly defined in the presence of missing data.

Another common approach is to conduct separate analyses, which Horton said yield multiple, often differing, sets of results for the various sources of information. Furthermore, he explained that separate analyses provide no formal way to evaluate the degree of similarities or differences among results from the different sources, nor do they provide a means to summarize them in a single set of results if they are similar. If some subjects are missing one data source and other subjects are missing another data source in some systematic way, he went on, the separate analyses will be based on different subsets of data.

Horton shifted to discuss two other approaches that he suggested are more suitable for analyzing dietary assessment data from multiple sources. The first is a unified regression model, which he described as a

flexible model that incorporates all multiple-source reports into a single multivariate regression analysis (Fitzmaurice et al., 1995; Horton and Fitzmaurice, 2004). This method can test for source differences in the outcome and estimate different source effects where necessary, he explained, and it can also test if there are source differences (e.g., sex of informants) in the effects of other risk factors on the outcome. Most importantly, Horton highlighted that the unified regression model includes partially observed data from subjects with missing source observations and reweights to account for systematic dropouts.

Another attractive analytic approach, he continued, is to use multiple informants as predictors (Horton and Fitzmaurice, 2004). Horton explained that this flexible model incorporates all multiple-source reports as predictors of an outcome not measured by multiple informants. As an example, Horton suggested that this approach could be used to examine the relationship between dietary intake (reported by multiple informants) and obesity status. This model can also test for source differences in associations with the outcome, as well as incorporate an estimation of different source effects where necessary.

Horton turned to analogies from other disciplines that he thought could inform the dietary assessment of food and supplement intake from multiple informants. For instance, an assessment of correlation between informants for measures of child psychopathology found fairly large correlations between informants of the same type (e.g., between two teachers or two mental health workers), but lower correlations between informants of different types (e.g., from parent to teacher) (Achenbach et al., 1987). These findings demonstrate that for some measures, relatively low correlation may exist between the data reported by different informants; findings of low correlation suggest that additional information could be unearthed through further analyses. In a study evaluating substance abuse, different levels of missingness were observed between self-report data and administrative data (Horton et al., 2002). Horton conveyed that these results suggest that collecting measures of the same variable from different sources allows for a more complete picture.

Horton shared two examples of synthesizing noncommensurate measures in a single unifying framework. In a study that aimed to synthesize multiple measures of depression, Horton explained that researchers considered how to harmonize results from studies that used noncommensurate measures (Siddique et al., 2015). Another study explored how to calibrate a measure that evolved over the course of a longitudinal study (Horton et al., 2001). Horton explained that this type of situation could play out in the realm of dietary assessment, for example, when researchers attempt to integrate different measures of the same underlying variable, such as both FFQ data and 24-hour recall data on the intake of fruits and vegetables.

Horton also raised the possibility of latent variables that are associated with certain indicators observed by different informants. This was the case in a study of the relationship between exposure to violence (as reported separately by parents and children) and respiratory outcomes in children (Horton et al., 2008). This study used latent variable modeling, he noted, to reduce measurement error. Horton also referenced a study that considered specific triggers for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing—some of which were only distally related indicators for such testing—and assessed the individual association of each trigger to predict testing (Liddicoat et al., 2004).

Horton shifted back to dietary assessment efforts and proposed several creative and efficient ways to account for missing data. These include having a “rescue question” (one or two carefully chosen items that tap key constructs while minimizing respondent burden) for those participants who would otherwise be lost to follow-up; combining parallel measures, when appropriate; capturing data through food photography or direct observation on a small subset of participants and extrapolating it to a larger population; and matrix sampling to minimize respondent burden. Horton also suggested that data fusion opportunities exist for noncommensurate measures, such as intakes from food versus supplements and total intake data from 24-hour recalls versus food diaries. He also mentioned the importance of addressing respondent bias and systematic sampling limitations and the potential for incorporating found (observational) data into systematically collected data.

To conclude his presentation, Horton offered a set of general, open questions to guide approaches to dietary assessment: What is the question of interest? What needs to be measured? What quantity are you trying to measure? How well do you want to measure it? How much effort and resources can be extended to assess the measures of interest? Analyzing measures from multiple informants can help to augment a primary assessment, he said in closing, and deepen understanding of nutrition and supplement use.

Q & A SESSION

Following their presentations, the four speakers answered questions from the members of the workshop series planning committee. The topics covered were estimating portion size using food photography, longitudinal assessment of dietary intake and health outcomes, addressing the challenges of analyzing data from multiple informants, exploring the consistency in the reporting biases of multiple informants, and integrating dietary supplements into assessment tools and analyzing the results.

Estimating Portion Size Using Food Photography

In response to a request from Anna Maria Siega-Riz, dean and professor in the School of Public Health and Health Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, to expound on the Healthy Environment Study’s use of food photography to calculate dietary intake, Johnson explained that a before-and-after photo allows for an estimation of the amount of food offered and consumed. The quantity consumed is then translated into nutrient and energy intake estimates. Adding that her group piloted this approach with families living in a rural area, Johnson noted that issues of broadband Internet access hindered real-time transmission of the photos to the research team. It was fortunate, she said, that participants had also received a tablet device on which to store food photos for the researchers to download later.

Longitudinal Assessment of Dietary Intakes and Health Outcomes

Dana Dabelea, professor of epidemiology and pediatrics and director of the Lifecourse Epidemiology of Adiposity and Diabetes Center at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, asked the speakers which dietary assessment method they would use for children 2 to 5 years of age if the research budget were unlimited and the goal was to explore longitudinal dietary intake and health outcomes. As a follow-up, Dabelea asked if the method would change for research examining the long-term health effects of a specific nutrient, such as vitamin D. Van Horn responded that her team has used 24-hour recalls in studies of 3- to 5-year-old children because that method offers greater precision to explore dietary patterns, dietary components, and nutrients. With respect to the vitamin D reference, Johnson noted that dietary intake alone would not provide sufficient insight, given that factors such as sun exposure and skin pigmentation affect status. She proposed combining dietary assessment techniques with other methods (e.g., biomarkers) for a more comprehensive understanding of the interface between nutrient intake and nutrient status.

Erica P. Gunderson, epidemiologist and research scientist in the Division of Research at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, wondered if specific dietary components are of particular interest in terms of potential association with future cardiovascular risk. Van Horn noted that dietary quality is increasingly recognized as an important influence on the microbiome and outcomes related to its composition, such as risk for obesity. She referred to the STRIP study as the sole example of an effort that has followed participants from birth to examine the potential effects of diet (measured longitudinally with food records and interviewer-assisted data collection) on longer-term health outcomes. Despite the important evidence this study

provides, Van Horn noted the value of additional studies, particularly the effect of maternal nutrition prenatally and during lactation on children’s health outcomes. Johnson maintained that a variety of health outcomes, including cognitive and motor development, could be considered in relation to dietary intake over the life course. Van Horn mentioned that the relationship between neurocognitive development and seafood intake, as reviewed by the 2020 DGAC, was the only area with a modicum of data, and that it was showing a positive relationship.

Addressing the Challenges of Analyzing Data from Multiple Informants

Siega-Riz noted that the same child’s eating habits may differ by caregiver, a point that Amy Herring, Sara and Charles Ayres Distinguished Professor of Statistical Science at Duke University, followed up on to ask Horton how to account for lack of knowledge about overlap in reports between informants. Horton affirmed this as an important consideration and reiterated the challenges that exist to obtaining complete records, such as participants’ failure to capture sufficient details about their dietary intake. He suggested that commensurate measures could be combined and that differences between informants could be examined by various characteristics (e.g., age groups). With an understanding of what types of information are measured well and consistently, he said that investigators can design studies to accommodate areas that are more prone to discrepancy.

Exploring the Consistency in Reporting Biases of Multiple Informants

Steve Daniels, professor and chair of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, pediatrician-in-chief, and L. Joseph Butterfield Chair in Pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Colorado, hypothesized that the multiple reporters of young children’s dietary intake might exhibit different tendencies to underreport information or to be influenced by social desirability bias in their reporting. He asked what is known about potential differences in reporting tendencies of parents versus child care workers, for example, and the implications for data analysis and interpretation. Anater said evidence suggests that parents tend to underestimate portions consumed at home compared with estimates of intake in child care settings and that analyses of FITS data and weighted day care intakes have confirmed these discrepancies. Horton referenced an example that he described as counterintuitive, where participants in the Black Women’s Health Study more reliably estimated their weight than their height compared with objective measures, although there was also a systematic bias of underreporting weight. He suggested that models could be built to account for observations of consistent reporting bias among certain

groups of people and that multiple dietary assessment methods could be used to triangulate on better measures. He added that this approach could be applied to a subsample of study participants and extrapolated to the full sample, although he cautioned that the analysis would be underpowered for various characteristics (e.g., differences by participant education level).

Integrating Dietary Supplements into Assessment Tools and Analyzing the Results

Cheryl Anderson, professor and dean of the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science at the University of California, San Diego, asked to what extent commonly used dietary supplements are integrated into assessment tools and what statistical implications exist if researchers have to manually create records for reported products. Anater said that FITS 2016 followed the same procedures as the study’s 2008 cycle of data collection, in which questions about dietary supplement intake were asked at the end of the 24-hour dietary recall. She said that investigators had to do additional work to classify commonly consumed dietary supplements, such as infant drops, gummies, and chewable products, in order to account for bioavailability, for example. FITS performed analyses of intakes both with and without dietary supplement intake, she added, to contrast intake from foods alone with total intakes. She also noted that current statistical tools are limited in their ability to integrate dietary supplement intake when characterizing intake distributions. Horton suggested that capturing dietary supplement intake from multiple informants can make matters “doubly complicated” because the challenges of integrating streams of information from different informants could manifest for both food and supplement intake reports. He proposed thinking of dietary intake and dietary supplement intake as two latent variables that could be related to a specific health outcome (e.g., weight status). To do this, he underscored the importance of collecting data with sufficient granularity to allow investigators to focus on specific dietary components and suggested that metabolomics may augment the dietary intake data.

PANEL DISCUSSION

Following the questions from the workshop series planning committee, audience members had an opportunity to submit questions for the speakers. The topics covered included study-specific improvements to food databases, FFQs for young children, strategies to improve the accuracy of the data provided by proxy reporters, telehealth technologies for conducting dietary assessments, methods for assessing young children’s dietary supplement use, and the variability in young children’s dietary intakes.

Study-Specific Improvements to Food Databases

An attendee asked if the infant and toddler-specific foods that FITS investigators added to the NDSR were available to all NDSR users. Anater reported that foods added by investigators are typically purged from the NDSR when a study is completed. Harnack added that NDSR users can create recipes, but unless researchers proactively share them with other colleagues, those recipes are only available in the context of each individual study.

FFQs for Young Children

Johnson responded to an attendee who asked if any validated FFQs are available for young children, remarking that food frequency screeners for this age group exist but that validation is difficult. In the absence of such tools, she encouraged doing “the best you can with the data you have.”

Strategies to Improve the Accuracy of the Data Provided by Proxy Reporters

In response to a question about whether caregivers actually use study-provided visual aids and other portion size estimation tools during 24-hour dietary recalls, Anater explained that although the majority of FITS proxy reporters used the box of interview aids they received in the mail, the dietary interviewers were also trained to help reporters if the materials were not accessible during the dietary recall. For example, interviewers referenced common kitchen tools, such as a tablespoon-sized measuring spoon, to help caregivers estimate quantity. She relayed that no appreciable differences existed in the accuracy of reporting between proxy reporters who did and did not use the study-provided interview aid materials.

Drawing on earlier conversations about multiple informants, Johnson noted that dietary recall aids are often provided to the primary caregiver but are not always provided to alternative reporters such as child care providers. Because alternative reporters have the potential to provide valuable information, Johnson proposed that investigators give greater consideration to these informants when designing studies. She suggested paying attention to details such as the guidance provided to alternative reporters, consideration of their ability to dedicate time and attention to recalling dietary intake for one of potentially many children in their care, and compensation for participation. Van Horn remarked that children in her studies whose weight trajectories did not improve often had multiple caregivers, who frequently provided snacks or meals each time a child transferred care. She

suggested this may result from caregivers’ lack of awareness of children’s dietary intakes during the time they were with a different caregiver.

Telehealth Technologies for Conducting Dietary Assessments

Siega-Riz referenced the rise of telehealth visits spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic and asked the speakers if such technologies might be used to conduct dietary recalls. Johnson hypothesized that videoconferencing technologies could enable 24-hour dietary recalls to be supplemented with other visual information. She suggested it may be valuable to take a subsample of participants and combine two methods of dietary assessment to determine if observed differences in the data reported are random or systematic. Horton concurred and added that although it would take considerable resources to conduct analyses that may feel redundant, the resulting insights could be valuable. Anater noted that caregivers tend to more accurately report intake by phone compared with in-person reporting and wondered how the visual element of videoconferencing technologies would affect reporting accuracy. Drawing on her experience with food photography studies, Johnson relayed that she has not observed a strong social desirability bias and thought the same may hold true for telehealth interviews. Dabelea emphasized that Internet connectivity and availability are essential logistical considerations for studies that employ telehealth strategies.

Methods for Assessing Young Children’s Dietary Supplement Use

Siega-Riz asked speakers to suggest an ideal approach for capturing dietary supplement intake data from young children. Van Horn espoused the value of collecting these data and reported that doing so has enabled her team to assess study participants’ dietary intakes both with and without contributions from supplements. Each analysis provides different information, she pointed out, elaborating that estimated total intakes (i.e., including intake from both food and supplements) provide a more comprehensive picture of the biological impact of the total intake, whereas estimated intakes from food alone inform preventive dietary recommendations. Van Horn anticipated that increasing interest in precision nutrition would fuel continued research to understand the interrelationships and synergies between nutrients. Johnson suggested that the collection of dietary supplement data could be augmented by merging methods. Specifically, she proposed the use of smartphones to capture and transmit real-time information, which investigators could use to ask the participant follow-up questions.

Variability in Young Children’s Dietary Intakes

Gunderson wondered if the day-to-day variability in young children’s dietary intakes is greater than that of other age groups and asked how many days of intake data would be ideal to get an accurate estimate of young children’s usual intake. Horton responded that the question about the number of days of intake applies to both dietary intake and dietary supplement intake and suggested that a more extensive assessment on a subset of participants would be informative. Van Horn indicated that “tremendous differences” exist between weekday and weekend dietary intakes, and Anater reminded attendees that young children are establishing taste preferences. Part of that process is frequent introduction to new foods, she added, and reasoned that this results in young children exhibiting more profound variability in dietary intake compared with adults.