The third workshop in this series, held May 19, 2021, featured four presentations about dietary assessment in children 6 to 11 years of age and included a question-and-answer session between the speakers and workshop series planning committee members as well as a panel discussion with the audience. Presentation topics included methods to collect dietary intake data in children 6 to 11 years of age, a comparison of two technology-based methods—the remote food photography method and the Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour (ASA24) Dietary Assessment tool—for measuring school-aged children’s dietary intake, objective passive ways to improve assessment of dietary intake in later childhood, and best practices for measuring dietary intake during this life stage.

Dana Dabelea, professor of epidemiology and pediatrics and director of the Lifecourse Epidemiology of Adiposity and Diabetes Center at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and member of the workshop series planning committee, provided opening remarks about the challenges and opportunities related to dietary assessment in children 6 to 11 years of age. This is a markedly heterogeneous age group in terms of ability to recall dietary intake information, she maintained, because of their gradual age-related development in cognitive abilities. Dabelea indicated that children are not able to reliably self-report their dietary intakes until they reach approximately 7 to 8 years of age, but even at that age, limitations persist in children’s cognitive capacity to rely on memory and estimate portion sizes.

These limitations introduce implications for the design of data collection tools intended for use by this age group.

Nutrient intake is at least two-fold more variable for children than for adults, Dabelea informed attendees, with even higher variability for nutrients consumed occasionally (versus habitually). These findings have informed the optimal number of recalls to be collected as well as the composition of the food databases used for analysis. Some evidence suggests tracking of nutrient intake over time in this age range, she said, which has implications for the choice of life stage during which to implement nutrition interventions.

The variation in cognitive abilities and nutrient intake among children in this age range affect the validity and accuracy of their reported intakes, Dabelea emphasized, with estimates likely biased in the direction of underreporting. Magnitude of bias varies by dietary assessment method and also appears to increase with the age of the child and the weight status of the child and/or parent but does not appear to vary by sex.

Dabelea used the Exploring Perinatal Outcomes among Children (EPOCH) observational cohort study to illustrate how the challenges of dietary intake reporting can bias observed associations between intake and health outcomes. She reported that her team observed an inverse relationship between sugar intakes at approximately 10 years of age (measured with a validated food frequency questionnaire) with hepatic fat at approximately 16 years of age (measured by magnetic resonance imaging). Because this relationship did not make biological sense, she said that the team used the Goldberg method1 to find that approximately one-quarter of the sample underreported their intake. Those who underreported were more likely to be Hispanic, have a higher BMI z-score, greater levels of both visceral fat and subcutaneous fat, and be offspring of mothers with higher levels of prepregnancy obesity. After excluding those who underreported, the association was no longer statistically significant. She suggested that the finding was likely caused by inaccurate reporting of sugar intake, which she said the study team plans to assess with different methods such as biomarker assays.

Dabelea pointed out several opportunities for improving dietary assessment among children 6 to 11 years of age. In terms of improvements to diet recall tools, she emphasized the importance of paying attention to the multiple dimensions of dietary assessment (e.g., accuracy, economic cost, respondent burden), the number of recalls, and multiple types of recall methods. Technology-based measures have the potential to reduce burden and improve accuracy, she pointed out, but present new challenges such as

___________________

1 This method compares the ratio of reported energy intake to estimated energy expenditure (via basal metabolic rate) to the 95% confidence interval of a physical activity level constant (Black, 2000).

selection bias caused by access issues, such as limited Internet connectivity of certain populations. She emphasized the need to validate reported dietary assessment measures, the potential role of biomarkers, and the importance of matching assessment tools with the research question(s).

METHODS FOR DIETARY ASSESSMENT IN CHILDREN 6 TO 11 YEARS OF AGE

Emma Foster, a nutrition consultant in Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom, discussed the challenges in assessing children’s dietary intake and shared examples of methods used with children 6 to 11 years of age, based on research conducted during her tenure at Newcastle University. The choice of assessment method depends on the research question (e.g., interest in a specific food group, food, or nutrient), the time frame of intake (e.g., usual intake or change following an intervention), and the budget, she said, and the offset between accuracy and participant burden should also be considered. In other words, the most accurate methods tend to require the most effort from respondents. As participant burden increases, she continued, so do costs and recruitment bias because only certain types of people are willing to thoroughly document their dietary intakes. At the same time, she said, those participating in more accurate assessment approaches are also likely to change their intake in response to participation, such as simplifying their meal preparation in an effort to minimize the amount of detail that is recorded.

Foster moved on to highlight the challenges of measuring children’s dietary intake and appealed to attendees to acknowledge those limitations and have realistic expectations of the accuracy that can be achieved when working with this age group. For instance, children often eat outside of their homes and have several caregivers involved in food provision. Furthermore, children may not know the names of the foods they have consumed, they may not be able to report how foods were prepared, and they may be attending to other stimuli instead of focusing on the food consumed during mealtimes. Measuring usual intake is challenging when children are in the midst of food jags (e.g., one week’s favorite food may be refused the following week), and leftovers, spillages, and swaps can also make estimation difficult. Social desirability bias may be heightened, she added, when parents want to convey the appearance of providing a healthy diet for their child and children want to convey that they have eaten everything on their plates.

Foster next presented methods that she and her colleagues at Newcastle University used and developed to assess children’s dietary intakes. In a school-based fruit and vegetable intervention that aimed to increase intake among children 4 to 11 years of age, Foster recounted how parents reported the foods consumed at home and observers collected data on intakes that

occurred at school. The team used a hybrid method consisting of a prospective food diary and a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) to gather the intake data; respondents selected from a checklist of foods commonly consumed among the study population and wrote in consumed foods that were not on the list. The reported foods were linked to a database of age- and gender-specific portion sizes, Foster continued, enabling the team to compare participants’ intakes with weighted intakes. Based on 4 days of intake data for 70 children, measured mean fruit intake was within 3 percent and mean fruits and vegetables intake was within 0.1 percent of weighed intakes (Adamson et al., 2003). Based on these results, Foster said the checklist approach was deemed appropriate for assessing population-level changes in fruit and vegetable intake among school-aged children.

In a study that examined children’s exposure to contaminants from food packaging, Foster explained that it was critical to collect detailed individual-level data, including accurate amounts and specifications for the size and type of packaging. Researchers asked caregivers to complete a weighed food diary for food consumed out of school, she said, and trained observers completed a weighted diary for food consumed during the school day (Foster et al., 2010a). Other studies have used estimated weight food diaries, she added, in which foods consumed are documented in real time but quantity estimates are completed via interview at the end of the reporting period. This approach has also been adapted for younger children, Foster noted, who draw pictures of items consumed away from home to be used as memory prompts when completing the diary with their caregivers at a later time.

Foster described her team’s techniques for dietary interviews with children, explaining that they have adapted approaches used with adults. It is important to focus on the things that children notice, she said, elaborating that children may not know the names of specific foods or preparation methods but can often answer questions about texture, color, or images on food packages. When her team first started collecting weighed food diaries from children, Foster said they used food portion images that had been designed for adults. After noticing that the pictures were not serving their intended purpose, the team developed and validated a series of food portion photographs for use in 24-hour dietary recalls or estimated food diary interviews with parents and/or children (Foster et al., 2010b). The photographs include 2,050 portion size images for 104 different foods, which can be used to estimate amounts of foods served and left over. Validation studies of the photographs indicated that mean intake of energy and macronutrients were within 5 percent of weighed intakes, and that by 11 years of age, children can report their dietary intakes with similar accuracy and precision as their parents (Foster et al., 2017).

In the final portion of her presentation, Foster described the development of a computerized 24-hour dietary recall system, INTAKE24, and

highlighted examples of its use among children. Food Standards Scotland funded her team to create the tool in 2010, Foster said, which links the team’s previously developed food photographs to food and nutrient composition codes and portion sizes. Similar to the ASA24, the INTAKE24 system is based on multiple-pass dietary recall methodology for self-report and intended for use by individuals 11 years of age and older. The interface is structured so respondents choose items using a free-text search, and it records intake by commonly consumed meals and snacks. Foster noted that food lists are simplified to improve usability among children, and that after they select a food item, respondents choose from a range of pictures depicting various portion sizes or container types.

The system also asks respondents about commonly forgotten items (e.g., sugar in tea, butter on toast) and verifies that long time gaps between reported intakes are not owing to omission of a snack or beverage. Additional questions may be added, she noted, to query respondents about the place they obtained certain foods or about dietary supplements consumed. INTAKE24 has been used in the Public Health England Sugar Smart campaign to assess sugars intake among children 5 to 11 years of age (Bradley et al., 2020), the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey for all age groups, the Scottish Health Survey for ages 11 and older, and in Australia, Portugal, Denmark, United Arab Emirates, and South Asia.

A COMPARISON OF TWO TECHNOLOGY-BASED METHODS FOR MEASURING SCHOOL-AGED CHILDREN’S DIETARY INTAKE

Traci Bekelman, research assistant professor in the Lifecourse Epidemiology of Adiposity and Diabetes Center and the Department of Epidemiology at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, discussed a study that compared two methods for measuring dietary intake among school-age children 7 to 8 years of age, and was conducted as part of the National Institutes of Health’s Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) program. The study was based on the idea that it is unclear how best to assess dietary intake in this population, she said for context, and its goal was to advance the science in this area. In addition to its comparison of dietary assessment methods, the study also aimed to identify opportunities to reduce misreporting and participant burden (Bekelman et al., 2021).

One of the tools examined was the remote food photography method (RFPM), in which participants take photographs of food offered and plate waste. The difference between the two photographs represents intake, Bekelman said, which is then used to estimate energy and nutrients consumed. Developed by the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, the RFPM SmartIntake smartphone application allows participants to include additional information about the food in the photographs, such as descrip-

tions (e.g., labeling milk as “whole milk”), source, and eating location. From Bekelman’s perspective, strengths of the RFPM include real-time data collection, which reduces misreporting owing to poor recall (memory); portion size estimation by study staff, which may be more accurate than participants’ estimation; and customized text reminders to submit images at participants’ usual meal and snack times, which helps reduce missing data.

The other tool examined was the 2018 version of the ASA24. This free, web-based dietary recall system is designed to maximize accuracy and minimize burden, she explained, with features such as a searchable food database of more than 7,000 items, portion size images, and standardized prompts for frequently forgotten foods. The ASA24 is frequently updated with new features, Bekelman added, including an enhanced capability to find misspelled foods.

To compare these two technology-based tools, Bekelman said that her team enrolled 40 children 7 to 8 years of age, consisting of approximately half female children and half children from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups; 26 percent of the children had a BMI above the 85th percentile (i.e., overweight classification). Each child’s parents were also enrolled to serve as proxy reporters to complete two 3-day dietary assessments—one using the RFPM, and one using the ASA24—in random order, 1 week apart. For the RFPM method, research staff photographed children’s lunch meals at school. Even though validation was not a goal of the study, Bekelman noted that each child’s Estimated Energy Requirement (EER) was calculated as a benchmark for actual intake. Reported energy intake with the ASA24 was 231 calories higher than the EER, she said, and reported energy intake with the RFPM did not differ significantly from the EER.

After parents reported their child’s dietary intake with both methods, they completed online surveys and participated in focus groups that sought to identify barriers to accurate reporting and perceived sources of participant burden for each method. Researchers also conducted individual interviews with school staff, she added, to identify opportunities and barriers to assessing what children eat in elementary school settings.

Bekelman reported that survey feedback on the tools revealed some differences by method. When asked which tool they preferred to record their child’s intake for 7 days, 61 percent of parents selected the RFPM, she said, and significantly more parents thought the ASA24 took more time to complete (74 percent) than the RFPM (26 percent). Nonetheless, she pointed out that Likert scale ratings indicated no significant differences between the two methods in respondent satisfaction, ease of use, and perceived burden (Bekelman et al., 2021).

Moving on to findings from the focus groups and interviews, Bekelman said that they revealed several strengths and opportunities for each dietary

assessment approach (see Tables 4-1 and 4-2). With regard to the RFPM, parents liked the phone app’s ease of use and customized text reminders, and they appreciated that they could capture data in real time—eliminating reliance on memory—and that they did not have to estimate portion size. They also noted that taking photos provided helpful insights into their children’s diet, especially portion size, but some found the process disruptive to routines (such as hectic weekday mornings or family dinners) or cumbersome (particularly if their child snacked frequently throughout the day). Parents also raised the issue of eating occasions that they were unable

TABLE 4-1 Parent Perceptions of the Remote Food Photography Method (RFPM) Assessed via Focus Groups

| Perceived Strengths of the RFPM | Opportunities to Improve the RFPM | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimize burden |

|

|

| Maximize accuracy |

|

|

SOURCE: Presented by Traci Bekelman, May 19, 2021.

| Perceived Strengths of ASA24 | Opportunities to Improve ASA24 | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimize burden |

|

|

| Maximize accuracy |

|

|

SOURCE: Presented by Traci Bekelman, May 19, 2021.

to capture because they simply forgot to take a picture or if food was consumed outside of the parent’s presence or provided by another caregiver. Bekelman highlighted this issue of unobserved intake as a unique challenge in this age group because children are old enough to eat unsupervised but not necessarily old enough to accurately self-report intake.

Turning to the ASA24, Bekelman indicated that parents liked the consolidated workload, structured data entry, and the availability of food images to help estimate portion size. On the other hand, they reported that entering each day’s intake was a significant time commitment (the study’s average time to complete the ASA24 was 26 minutes), that they were challenged to find some ethnic and restaurant foods in the food database, and that they lacked confidence in their ability to estimate portion sizes consumed. Bekelman inferred that parents’ portion size estimates for food consumed at school may be particularly prone to misreporting. Interviews with school staff also revealed concerns about unobserved intakes leading to misreporting; when asked how much parents know about what their children eat at school, one teacher replied “I really think they have no idea.”

In summary, Bekelman maintained that dietary assessments in which parents are proxy reporters for their children have unique challenges above and beyond dietary assessments in which adults report their own intake. When interpreting findings based on such assessments, it is important to account for the unique characteristics and limitations of each method. She urged future research to consider accuracy, cost, and burden on parents, children, schools, and researchers. Technology-based measures bring many advantages, but also new potential sources of misreporting and burden. Therefore, she contended that continued efforts to minimize the challenges parents face in documenting intake for both the RFPM and the ASA24 are justified, based on high acceptability among her study’s parent respondents.

OBJECTIVE PASSIVE METHODS TO ASSESS DIETARY INTAKE IN LATER CHILDHOOD

Tom Baranowski, distinguished emeritus professor at the Baylor College of Medicine, reviewed objective passive ways to improve assessment of dietary intake. He urged attendees to view his presentation’s content as interesting ideas for possible future methods but not as currently available, off-the-shelf methods for immediate application.

Baranowski echoed prior speakers’ sentiments about the limitations of existing methods to assess children’s dietary intakes and shared anecdotes from his own experiences. In one of his group’s efforts to compare children’s observed and self-reported intakes, he highlighted the findings that approximately 25 percent of the foods that the child ate were forgotten

foods (i.e., those foods were not recalled by the child the following day), and an additional 25 percent of the foods that the child reported eating were intrusions (i.e., those foods were not actually consumed based on data from adult observers of the eating occasion). Baranowski also remarked that reporting errors increase with length of time since the recalled meal was consumed and that in his experience, children were not able to provide reasonably accurate intake data until 10 years of age.

Highlighting the importance of developing methods that address these challenges, Baranowski turned to describe several innovative approaches that have been developed to quantify dietary intake. Much of the literature on this topic is from the engineering field, he commented, such as efforts to use sensors of chewing, swallowing, and arm and hand movement toward the face to detect eating events, as well as a tooth sensor that senses biochemical composition of food intake. Another strategy that has been developed is a camera, attached to an eyeglass frame or an earpiece, that photographs everything in front of the wearer at certain time intervals throughout the day. Continuous glucose monitoring and metabolomics have also been used to assess dietary intake, he added, and reiterated that the chosen method must be a good fit for the measure of interest.

Baranowski elaborated on a passive objective dietary assessment method called the eButton, which he described as a relatively small, chest-worn device that has been in development for nearly 15 years. The eButton incorporates multiple sensors, such as a camera, motion sensor, barometer, thermometer, and light sensor, which he said work together to detect and classify dietary intake. The camera is capable of producing images at 4-second intervals throughout the day, yielding 10,800 images during a 12-hour period.

Baranowski outlined an ideal approach to processing these images: initial encryption (at time of capture); transmission to central, local storage (at the end of a designated time interval, such as the end of the meal or the day); de-identification to protect confidentiality; and estimation of intake based on the images. Current efforts to estimate intake occur centrally at a research laboratory, Baranowski noted, but he proposed that it would be ideal to estimate intake locally and immediately in order to provide timely feedback to participants. The process of estimating intake is segmented into a five-step sequence that uses artificial intelligence, he continued, to identify images with food (step 1), identify the specific foods in those images (step 2), assess portion size and amounts consumed (step 3), assess food preparation undertaken during the day (step 4), and incorporate the information from steps 1–4 to estimate intake (step 5).

Baranowski reported that artificial intelligence techniques have made headway in the first three steps of the five-step process for estimating dietary intake. The techniques have been able to successfully identify images with

food (step 1), he said, but identifying the specific foods in those images (step 2) has been more challenging. Even though a couple thousand specific foods can be pinpointed to date, Baranowski acknowledged that much more work remains in order for the techniques to be able to identify the huge variety of foods that people consume. Alternatively, he suggested, some investigators may only need artificial intelligence to identify certain categories of foods, which he thought could be more feasible for existing technology.

Three approaches have been pioneered for estimating portion size (step 3), Baranowski continued, but pointed out that this is not necessarily equivalent to the amount consumed. One method is to impose a three-dimensional wire mesh on the perimeter of the two-dimensional food image and use an algorithm to quantify the amount within the wire mesh. The problem with this method, he explained, is that the third side of the image is unknown. A second method is a procedure that examines the concentration of dots in a food image to identify the dimensions of the food present, and a third method uses a matching procedure where a string of food images within a photo library is matched to the food image under investigation. He was optimistic about the potential for the third method but said it requires a photo library with lots of food images that have composites representing three-dimensional views of the image.

Work is under way to determine how best to incorporate images of food preparation (step 4) and to continue honing the accuracy for each step of the image-processing sequence. Errors that occur at any step in the sequence are additive, he explained, so having a good process at one step does not necessarily correct errors that occur elsewhere in the process.

EXPLORING BEST PRACTICES FOR MEASURING DIETARY INTAKE IN CHILDREN 6 TO 11 YEARS OF AGE

Wei Perng, assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the Colorado School of Public Health and assistant director of omics research at the Lifecourse Epidemiology of Adiposity and Diabetes Center at the Colorado University Denver Anschutz Medical Campus, discussed best practices for measuring dietary intake in children 6 to 11 years of age. She prefaced her presentation by acknowledging that the determination of a “best practice” hinges on the perceived goal of dietary assessment. According to an informal survey of a few of her nutrition researcher colleagues, Perng said that the perceived goals of dietary assessment vary. For example, the focus may be on individuals or populations, and the objective may be to ascertain absolute or relative intakes. Furthermore, she added, the precision and accuracy of the assessment may be more or less of a concern.

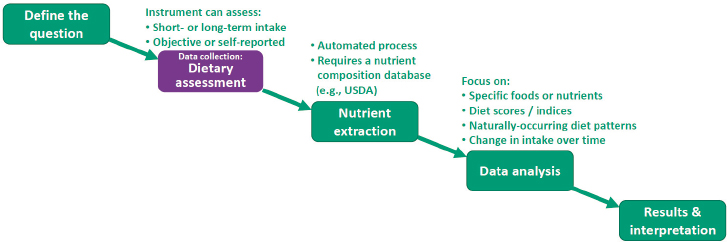

Perng shared a nutritional epidemiology road map to illustrate that dietary assessment occurs early in the research process (see Figure 4-1),

NOTE: USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture.

SOURCE: Presented by Wei Perng, May 19, 2021.

and she explained that threats to data quality at this step will flow down to affect subsequent processes.

The primary threats to data quality in epidemiologic research are error and bias, Perng stated, and maintained that error is the more benign of the two. This is because error manifests as random noise that might obscure associations, she explained, whereas bias can skew results either away from or toward the null. Perng emphasized that in any case, error and bias affect the quality of dietary data collected and are therefore important considerations for determining best practices.

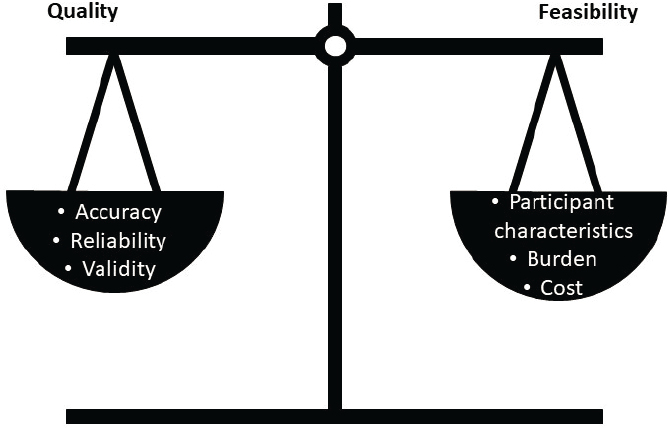

The best instrument for dietary assessment is based on a balance of quality and feasibility, Perng pronounced, regardless of the age of the study sample (see Figure 4-2). The quality of the data collected by an instrument is influenced by three determinants—accuracy, reliability, and validity—that are each affected by error and/or bias. Accuracy is the proximity of a measured value of dietary intake to the true measure, she explained, offering the analogy of the ability to place a dart in a bullseye. Reliability, she continued, refers to the consistency of results for an instrument when it is implemented repeatedly over time in the same population. This is analogous to placing the dart in the same location on the dartboard with each throw, she explained, even if the location is not the bullseye. Finally, validity is the extent to which the instrument captures the dietary construct that it is intended to reflect, both in the study sample and in other populations.

Perng next described three determinants, practical in nature, that influence the feasibility side of the balance and are drivers of error and/or bias: participant characteristics, burden, and cost. Examples of participant characteristics are literacy, cognitive capacity, and cultural norms, she said,

SOURCE: Presented by Wei Perng, May 19, 2021.

noting that such aspects are particularly prone to introducing bias into data when it is self-reported. Burden encompasses factors such as the time and resources available to train study staff as well as the time and effort required of participants to complete the assessment. She cautioned that burden on participants can affect the quality of data they provide, which can introduce error into measurement of dietary intake. Lastly, Perng noted that budgetary constraints clearly affect the affordability, and therefore, choice of instrument.

Perng moved into a summary of six conventional, validated instruments for measuring children’s dietary intakes: FFQ, 24-hour dietary recall, and weighed food record, which she said are the most commonly used instruments in epidemiological studies of children; as well as meal observations, biomarkers, and anthropometry. She briefly described each method, the type of data it collects, and its strengths and limitations. She also classified each method’s overall burden level as low, medium, or high (see Table 4-3).

Perng highlighted the weighed diet record for its reputation as the gold standard for assessing dietary intake, as well as its usefulness for validating other recall-based instruments. She also noted that biomarkers and anthropometry are different from the other instruments in that they are markers of nutritional status and intake (as opposed to intake alone, as is the case with the other instruments), and they are useful for supplementing dietary intake data. Reliable concentration biomarkers exist for the long-

TABLE 4-3 Comparison of Instruments for Dietary Assessment in Children 6 to 11 Years of Age

| FFQ | 24-Hour Recall | Weighted Diet Record | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methods |

|

|

|

| Data collected |

|

Intake over the past 24 hours | Actual intake recorded during a short-term period (2 days to 2 weeks) |

| Strengths |

|

|

|

| Limitations |

|

|

|

| Key points |

|

|

|

| Overall burden level | Low burden | Medium burden | High burden |

NOTE: ADP = air displacement plethysmography; BIA = bioelectrical impedance analysis; DXA = dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; FFQ = food frequency questionnaire.

SOURCE: Presented by Wei Perng, May 19, 2021.

| Meal Observations | Biomarkers | Anthropometry |

|---|---|---|

| Trained rater observes subject at mealtime | Biochemical measurement from tissues |

|

| Precise information about amounts and types of foods consumed | Biomarker concentration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| High (staff) burden | Low/medium burden | Low/medium burden |

term intake of iron, folate, and some fatty acids, she said; these may serve as objective assessments to validate instruments that rely on self-report.

Perng transitioned to discuss best practices for assessing children’s dietary intakes by saying that the best balance between quality and feasibility is the 24-hour recall. An interviewer-administered (versus automated) recall that covers 2 weekdays and 1 weekend day is preferred, she continued, and a caregiver proxy is ideal for children younger than 10 years of age. Evidence suggests that giving the child informal food records for use at school and providing a cafeteria menu to the interviewer are two strategies that improve quality of the data collected (Trolle et al., 2011). Perng also commended the FFQ for its high feasibility in large studies, driven largely by its low participant burden. FFQs are also well suited for ranking intakes of individuals within a population, which she noted as highly relevant for assessing associations with chronic disease risk. A caregiver proxy is ideal for this instrument as well, she added, as is using a validated FFQ for the sample’s age group and cultural norms. She highlighted two validated FFQs for youth in the United States, the Block Kids FFQ and the Youth Adolescent FFQ (Cullen et al., 2008; Rockett et al., 1997). Although these two tools have been validated only for older children and adolescents, she noted that some studies suggest that they yield reasonably reliable results for children younger than 9 (Metcalf et al., 2003), especially with the help of a caregiver.

Perng also suggested best practices for analytical approaches to further mitigate error and bias, beginning with adjusting for total energy intake to improve accuracy, reliability, and validity of estimates. Because total energy intake is positively correlated with intake of all nutrients, including those that do not provide energy (e.g., fiber, vitamins, and minerals) (Willett and Stampfer, 1998), she explained that incorporating total energy intake in the analysis controls for confounding and strengthens causal inference by simulating an isocaloric dietary intervention. Another best practice, she continued, is based on the recognition that children underestimate intake of foods typically enjoyed during childhood (cookies, juice, and possibly milk) and overestimate intake of calories, protein, and sodium (Raffoul et al., 2019). Accuracy can be improved by employing regression-based calibration equations that remove nondifferential error, she suggested, whereas correcting bias to improve reliability and validity can be accomplished by predictive algorithms to identify new thresholds of excessive, adequate, and inadequate intake. Lastly, she urged those who interpret these research findings to be aware of how random error and reporting bias may influence results, depending on the instrument used.

Finally, Perng said that dietary assessment efforts need to consider children’s dietary patterns in addition to their intake of specific nutrients and foods. The field of nutritional epidemiology is moving in this direction, she

observed, given that people eat combinations of foods and nutrients that interact at the biological level to affect health. She shared findings from the EPOCH cohort, noting that although reflective of data from older children, findings demonstrate a positive association between increasing compliance with a prudent dietary pattern over time and more favorable health outcomes among youth. Such analyses are useful for characterizing dietary patterns, which she said is particularly informative during childhood as flavor preferences and lifestyle habits are established during this time, setting the stage for future chronic disease risk.

Q & A SESSION

Following their presentations, the four speakers answered questions from members of the workshop series planning committee. The topics covered were assessing children’s dietary supplement use, the misreporting of sex differences in energy intake, choosing an optimal method to assess children’s dietary intake, using dietary assessment methods to assess diet quality, and advancing novel technologies for dietary assessment.

Assessing Children’s Dietary Supplement Use

Cheryl Anderson, professor and dean of the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science at the University of California San Diego, asked about best practices for assessing children’s dietary supplement use. Bekelman reported that parents in her study were instructed to take pictures of the containers of any supplements their child used but said that no such pictures were submitted to the researchers. The study team also opted to include a supplement question when they administered the ASA24, she added, and one participant reported supplement use on all three of the days for which intake was reported. She expressed uncertainty about whether these results suggest that supplement use was uncommon in the group or if the method was unable to detect participants’ use. Foster said her group had not assessed children’s supplement use extensively, but echoed prior speakers’ suggestions to ask participants to provide the containers of any supplements used and to collect data on frequency of use.

Sex Differences in Energy Intake Misreporting

Anna Maria Siega-Riz, dean and professor in the School of Public Health and Health Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, observed that Bekelman’s data on differences in reported energy intake from her study’s two methods (the ASA24 and the RFPM) compared with the EER was driven by boys’ misreporting. Bekelman confirmed that the

study observed significant differences between the ASA24 and the RFPM in reported energy intake among boys and also between each of those methods and the EER among boys. This finding was not observed for girls, which she said was unexpected based on an apparent lack of evidence to suggest sex-related bias or differential accuracy in children’s dietary intake reporting. The finding may be caused, at least in part, to the parents taking the photos, she suggested, unsure of a plausible mechanism by which reporting would be less accurate in boys. It would be interesting to see if this finding is replicated, she suggested, in studies with larger samples or with a gold standard of intake. Foster recalled her group’s finding of some differences in portion size estimation between boys and girls, but she said it was not significant and that it might be reasonably expected that girls may be more likely than boys to underreport their intake.

Choosing an Optimal Method to Assess Children’s Dietary Intake

Steve Daniels, professor and chair of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, pediatrician-in-chief, and L. Joseph Butterfield Chair in Pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Colorado, asked speakers to suggest optimal methods for dietary assessment in children 6 to 11 years of age. Foster replied that a study’s budget and the desired accuracy level of data collected are key factors for choosing a method. For one of her studies that needed highly accurate data, Foster said that the investigators trained observers to measure and record what children consumed at school. She also noted her team’s finding that child care staff were able to provide a reasonably accurate report of what children were served but could not provide adequate information about how much each child consumed.

Dabelea asked if Bekelman’s data indicated that either the ASA24 or the RFPM is better for assessing children’s dietary intakes or whether the choice of method depends on the study context. Bekelman’s response emphasized the importance of matching the assessment method and tool to the research question. Food photography is well suited to provide data on foods offered and plate waste, she pointed out, which offers insight into behaviors such as selective eating and food neophobia, for instance. She also urged consideration of a method’s unique characteristics such as accuracy, burden on both researchers and child participants, novel features, and costs. To put it another way, she suggested that researchers could think about what disadvantages of a method they are willing to tolerate as a trade-off for incorporating its unique advantages in a particular study.

According to Siega-Riz, further study on larger samples and different subpopulations will help indicate the generalizability of Bekelman’s findings. She also raised the issue of the “digital divide” and suggested that although most people own smartphones, the ability to navigate a food

photography app could be a challenge for some and will result in missing data if food photography methods are used. She reiterated what she called a “fundamental principle” of dietary assessment, which is the importance of using multiple methods to assess a dietary variable of interest.

If she were designing another study, Bekelman said it would be interesting to (1) validate the dietary aspect of interest against a gold standard (e.g., doubly-labeled water for energy intake), (2) to examine a diverse sample to learn how a method’s accuracy and burden may vary by population subgroups, and (3) to assess accuracy in parental and other caregiver reporting of intakes that they did not directly observe. In response to a question about videorecording meals from Erica Gunderson, epidemiologist and research scientist in the Division of Research at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Bekelman said that videorecording would provide rich data about multiple dimensions of eating behaviors and parent feeding practices. She cautioned that this approach comes with the concern that participants may change their behaviors as a result of being recorded. Foster added that securing approval to videorecord participants will involve discussion of ethical considerations.

Gunderson also asked if involving fathers could help improve reporting accuracy, especially among boys. Foster stated that her work with younger children has involved interviews with the child and a parent, which she reported was usually the mother although investigators did not specify which parent was to participate.

Dietary Assessment Across Life Stages and Settings

Dabelea asked Perng if her advice on best practices for assessing children’s dietary intake is also relevant for other age groups and life stages, and whether any age- or stage-specific considerations exist. Perng underscored that the designation of a best practice depends on the research question. As an example, she said that focusing on the outcome of dietary patterns is not ideal if the research question centers on the role of a specific food or nutrient.

Daniels next asked Perng if her advice on best practices would change if the dietary assessment was conducted in a clinical setting. The 24-hour recall is probably still the best option for this setting, Perng supposed, assuming that the goal is to assess health status, nutritional status, or intake of a specific dietary component. A weighed diet record is another excellent option, she added, although expensive, and an FFQ could also be valuable for child well visits as a source of contextual information for the clinical assessment of growth patterns.

Using Dietary Assessment Methods to Assess Diet Quality

Perng responded to a question from Gunderson about how the dietary assessment methods she presented could be applied to assess diet quality. As each method provides intake data on specific foods and nutrients, Perng explained, an automatic extraction process is performed to correlate intakes with existing indices or scores of diet quality such as the Healthy Eating Index. When associations are detected between a particular score or range of scores and a health outcome, she continued, this result can be translated into food-specific or food group-specific recommendations in relation to that health outcome.

As a follow-up question, Gunderson asked if any of the assessment methods can distinguish the proportions of naturally occurring and added sugars in a respondent’s intake.

Such information could be gleaned from 24-hour recall data, Perng suggested, when the nutrient profile of reported foods is extracted from the underlying food composition database. Potential for error and bias exists depending on the database used, she added, because data are supposed to be representative of foods in a given country or setting but that may not always be the case.

Advancing Novel Technologies for Dietary Assessment

Siega-Riz asked Baranowski what it will take to advance novel technologies for dietary assessment to the point of readiness for implementation in epidemiological research. This goal is still a long way off, Baranowski conceded, reiterating his presentation’s opening disclaimer that much more technical development is needed before these methods are ready for widespread application. A crucial step in passive image-taking methods is processing the images, he said as an example, and quipped that “the eButton wasn’t built in a day.”

On that note, Amy Herring, Sara and Charles Ayres Distinguished Professor of Statistical Science at Duke University, asked where funding agencies could prioritize investment to support development of novel technologies. According to Baranowski, measurement studies are often just a small component of the funding for a larger intervention or effort and less likely to be funded as a stand-alone project. He suggested more substantial investment in development of measures themselves, noting that previous funding from the National Cancer Institute for methods development helped to advance some of the novel technologies discussed during the workshop series. Huge advances are occurring in artificial intelligence, he pointed out, that could accelerate improvements in the accuracy of dietary assessment methods.

Daniels continued the topic as he asked what types of expertise would be important to include in such measurement studies. Baranowski stated that the teams working on novel dietary assessment methods have included engineers, data scientists and statisticians who are proficient in working with big data and using it to test hypotheses, and registered dietitians. A major step forward would be to incorporate images of at-home food preparation into the intake estimates from other assessment methods, which Baranowski implied would improve accuracy and perhaps warrant involvement of team members with culinary training.

Herring wondered if publicly available images or videos of foods and food preparation could be used in competitive events that engage technical developers in exploring methods to process and classify the data. This kind of tactic could raise interest and engage future collaborators, she suggested, using relevant sources of data. Baranowski noted that artificial intelligence algorithms are being trained on existing databases of food images, consisting mostly of images of foods available in stores or restaurants. However, food left at the end of a meal is typically not in standardized sizes, he pointed out, making it difficult for automated portion estimation procedures to produce accurate estimates.

Daniels asked Baranowski to elaborate on the ethical considerations of using objective passive methods to assess dietary intake, such as which parties need to consent. Baranowski explained that images captured with this method are encrypted immediately upon transmission to a central storage site and then de-identified. He relayed that his studies using this method have not encountered problems securing parental and child consent, and that his institutional review board deemed those parties’ consent sufficient in light of the confidentiality procedures woven into the image processing.

PANEL DISCUSSION

Following the questions from the workshop series planning committee, audience members had an opportunity to submit questions for the speakers. Question topics included the timing of dietary intake assessments, conducting dietary assessment in developing countries, and measuring intake of unprocessed foods.

Timing of Dietary Intake Assessments

In the interest of capturing seasonal variation in intake, Daniels wondered how to handle the timing of assessments for intakes that occur at school, given that most children are not in school year-round. Foster’s studies that have examined usual intake conducted assessments at different time points during the year. The same methods were used at each

time point, she said, and they were completed by parents for intakes that occurred out of school and by trained observers for intakes that occurred at school.

Bekelman pointed to evidence suggesting there are differences in children’s lifestyle behaviors (e.g., diet, physical activity, sleep) between the academic year and the summer, which she said is why her study was conducted during the academic year. Otherwise, she clarified, it would have been difficult to tease out the potential effects of summer vacation, such as the addition of alternate caregivers (e.g., summer camp counselors). She maintained that the issue of seasonality merits further discussion in the dietary assessment literature.

Siega-Riz emphasized that the research question drives decisions not only about the choice of method but also the timing of its administration. If the goal is to improve the child’s dietary intake and the child spends a majority of time with a parent, she said as an example, then it is important to assess at-home intakes. If the goal is to attain a broader perspective on the child’s eating habits, she said in contrast, then both at- and away-from-home intakes as well as seasonality are important. Dabelea said that children’s habitual intakes in relation to future health outcomes are of primary research interest, which she said calls for different methods than a research interest in examining the intake of specific nutrients during a specific time period. In any case, she continued, accuracy is critical but might be approached in different ways depending on the research question.

Conducting Dietary Assessment in Developing Countries

An attendee asked what unique considerations exist for dietary assessment conducted in developing countries. Baranowski referenced an effort to test technology-based methods in Ghana and described the challenges as “overwhelming.” As an example, he pointed out that the eButton needs a stiff collar for proper attachment, whereas many of the shirts worn in Africa are loose-fitting. Other challenges to obtaining suitable images are low lighting and lack of (or intermittent) electricity, while portion size estimation is complicated by cultural practices such as eating foods by hand, often directly from a common bowl. Foster echoed those challenges, drawing on her previous efforts to measure dietary intakes in Tanzania. She speculated that food eaten directly from a common pot was the main challenge because that practice makes it difficult to estimate the amount that any individual consumed. Obtaining recipe details was also a challenge, she relayed, because most participants did not have scales or household measuring tools to quantify amounts of ingredients.

Lisa Harnack, professor in the School of Public Health at the University of Minnesota, referred to her work in Nigeria and Brazil where she said

that sometimes only handwritten intake data is available because of limited technology. Another challenge, she added, is the availability of food databases that include the foods and nutrients consumed in different countries. She said that strategies to enable the calculation of food and nutrient intake include leveraging local databases or pairing them with databases from the United States or other countries.

Perng commented that it is important for FFQs used in developing countries to reflect some cultural knowledge of the study population, which she said is difficult in locations where little information on residents’ dietary practices is available. Echoing other panelists’ comments about the value of forming multidisciplinary teams to advance dietary assessment methods, she suggested that anthropologists would be a helpful addition and could advise on the types of foods to include in FFQs for use with diverse cultures.

Measuring Intake of Unprocessed Foods

An attendee mentioned the difficulty characterizing intake of whole unprocessed foods, particularly those consumed in away-from-home settings. Perng acknowledged that FFQs are often nuanced in their description of foods and include varying degrees of granularity depending on the research question they were designed to address. She gave the example of an entry for potatoes with additional identifiers such as “fried,” “whole,” or “mashed with butter,” noting that those kinds of preparation details can help characterize a reported food.

This page intentionally left blank.