The first workshop in this series, held May 6, 2021, featured four presentations about dietary assessment during pregnancy, question-and-answer sessions between the speakers and workshop series planning committee members, and a panel discussion with the audience. Topics included estimating the intake of dietary supplements, perspectives from a nutritional phenotyping cohort, a French-Canadian perspective, and analytical methods.

CHALLENGES TO ESTIMATING DIET DURING PREGNANCY

To set the stage for the speaker presentations, Anna Maria Siega-Riz, dean and professor in the School of Public Health and Health Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and member of the workshop series planning committee, reviewed pregnancy-specific considerations when assessing diet.

The first consideration, Siega-Riz began, is to recognize the common assumption that the overall type of diet does not change during the course of pregnancy. Experiences with cohorts and focus groups of pregnant women indicate increases in the amounts of foods normally eaten, as well as (1) slight reductions in the consumption of certain foods and beverages (e.g., those containing caffeine or alcohol, although she noted that consumption of the latter is often under-reported), (2) slight increases in dairy products (and for vegetarians, in protein sources), and (3) greater dietary changes overall among women whose incomes allow for it.

Siega-Riz highlighted two systematic reviews that examined dietary changes during pregnancy. The first included 11 articles from 9 studies published between 1998 and 2014 that evaluated dietary changes during pregnancy compared with the preconception period (Hillier and Olander, 2017). Most articles reported that women increased their energy intake during pregnancy, and most also found significant increases in the consumption of fruits and vegetables and decreases in the consumption of eggs, fried food, fast food, and coffee or tea. About half of the studies assessed sociodemographic characteristics associated with the dietary changes, Siega-Riz added, saying that age, education, and pregnancy intention were positively associated with healthy dietary changes.

The second systematic review assessed dietary changes between pregnancy and the postpartum period (Lee et al., 2020), she said; it included 17 articles published between 1992 and 2019, 8 of which evaluated diet once during each trimester. Findings were mixed with regard to changes in intakes of energy and micronutrients, although most studies reported significant decreases in consumption of fruits and vegetables, lower diet quality, less adherence to a healthier dietary pattern, and increases in discretionary foods and fat intakes during the transition from pregnancy to postpregnancy. Lower income and education levels as well as full-time employment status, Siega-Riz noted, were positively associated with poorer dietary behaviors postpregnancy. Taken together, she summarized, these two systematic reviews suggest that pregnancy is a vulnerable period during which women are willing to make some or certain dietary changes.

Siega-Riz turned to discuss a second consideration, which is to determine the number of assessments—and the timing of their administration—needed to characterize dietary intake throughout the duration of pregnancy. This time period is shorter than the time periods associated with other diet–disease relationships of high research interest, she pointed out, but multiple assessments conducted at specific time points are important because changes that occur during certain phases of pregnancy influence typical intake of food groups and nutrients. Such changes include the occurrence of nausea and vomiting, which often present during the first trimester but may persist throughout the entire pregnancy; development of cravings and a perceived

need to “eat for two,” both of which can alter typical dietary choices; development of complications as pregnancy progresses, such as gestational diabetes or hypertension, which typically result in dietary changes; and a decrease in appetite and physical activity level during the third trimester as the growing baby crowds the abdominal area. Siega-Riz also noted less time-specific considerations, such as the extent to which intakes of beverages and dietary supplements are assessed.

ESTIMATING INTAKE OF DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS DURING PREGNANCY

Kate Sauder, assistant professor of pediatric nutrition and assistant director for translation research at the Lifecourse Epidemiology of Adiposity and Diabetes Center at the University of Colorado, discussed best practices for estimating the intake of dietary supplements during pregnancy.

Sauder began by highlighting the importance of considering dietary supplements in pregnancy research, explaining that micronutrient inadequacies during this life stage are common. Four in five pregnant women get insufficient vitamin D, vitamin E, and iron from food sources, she elaborated, and one in four get insufficient vitamin B6, folate, vitamin C, calcium, magnesium, and zinc (Bailey et al., 2019b). Adherence to a vegan diet is associated with higher risk of inadequate intake of vitamin B12, vitamin D, calcium, iron, iodine, and omega-3 fatty acids (Sebastiani et al., 2019), and all women—regardless of dietary pattern—face barriers to consuming a nutritionally adequate diet during pregnancy. Examples include shortcomings in knowledge and in cooking skills, time and cost barriers, morning sickness, and obstetric complications. Risks of inadequate micronutrient intake during pregnancy are well known, Sauder said, and include neural tube defects (inadequate folic acid intake) (De-Regil et al., 2015), low birth weight (insufficient iron) (Keats et al., 2019), and other maternal and child outcomes associated with insufficient vitamin A (van den Broek et al., 2010), vitamin D (Palacios et al., 2019), calcium (Buppasiri et al., 2015), and omega-3 fatty acids (Middleton et al., 2018).

The prevalence and implications of inadequate micronutrient intakes during pregnancy are widely reported, Sauder said, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends preconceptional and prenatal micronutrient supplementation (ACOG, 2011, 2017, 2019). Most (75 percent) pregnant women in the United States take a prenatal vitamin on a given day (Bailey et al., 2019b; Sullivan et al., 2009), she reported, and nearly all (95 percent) pregnant women report prenatal vitamin use at some point during pregnancy (Dubois et al., 2017; Sauder et al., 2016). Therefore, failure to assess dietary supplement use during pregnancy results in an incomplete picture of nutrient intake.

Sauder moved on to review best practices for assessing dietary supplement use during pregnancy. She provided suggestions related to the frequency of assessment, preparing respondents for assessment, critical details to collect, instrument-specific tips, and interpreting results in the context of an assessment tool’s limitations.

More frequent assessments can limit reliance on longer-term recalls and is preferable for additional reasons, such as capturing increases in dietary supplement use as pregnancy proceeds (based on reported prevalence of 63 percent during the first trimester to 91 percent during the third trimester [Branum et al., 2013]) and recording changes in specific products used based on personal preferences, provider recommendations, or manufacturer changes in formulation (Rifas-Shiman et al., 2006). Sauder suggested that women can provide more precise reporting of their dietary supplement intake if they are encouraged to bring the supplement containers to their appointment or provide a picture of them. Critical details to collect include the brand name, product name, dose, frequency, and time period (i.e., specific dates) taken.

When assessing dietary supplement use in the context of specific dietary assessment instruments, Sauder urged researchers to consider each instrument’s strengths and limitations to discern which is best matched to their resources and research question(s). She described three types of dietary assessment instruments in more detail, beginning with 24-hour dietary recall tools. The first option for assessing dietary supplement use in this context is to have the dietary supplement databases embedded in the recall system, although Sauder warned that a key limitation of this approach is that abnormal supplement use (e.g., missed or extra dose) during the target period can bias results. The second option, she continued, is to use an external dietary supplement log, which she said requires more postcollection data processing and cleaning because it is a stand-alone component. She said that the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) takes a two-pronged approach of combining 24-hour recalls with an in-home inventory of dietary supplement use (including brand, product name, dose, and frequency) during the prior 30 days.

Turning to discuss food frequency questionnaires (FFQs), which she suggested are better suited than 24-hour recalls for accurately capturing episodic dietary supplement use during pregnancy, Sauder explained that interviewers can use an FFQ tool with embedded questions about dietary supplements or an external dietary supplement log. Using the questions embedded in an FFQ tool offers the benefit of direct linkage to supplement databases that provide micronutrient content, she pointed out, but a limitation of using embedded questions in FFQs is that the restricted answer options preclude collection of detailed information. As an example, she stated that the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Diet History Question-

naire III asks users to read a list of vitamins and dietary supplements and mark those that they took at least once during the prior month. The generic nature of list’s response options and inability to indicate a specific brand or formulation lead to relatively imprecise intake estimates, she explained, because they are based on an average of available products. Other FFQs may allow respondents to write in specific brand names and product information, she pointed out, but may still miss data if the number of supplements used exceeds the number of write-in slots.

Sauder briefly discussed food records, which she indicated could easily be set up to incorporate dietary supplement use during the target period. If assessment is desired for a longer period of time than is covered by typical food record tools (i.e., 3 days or 7 days), she suggested establishing a separate supplement log to capture such intake for 30 days or multiple months as one example.

Sauder moved on to review limitations that she described as inherent to assessing micronutrient intake from dietary supplements, urging stakeholders to consider these limitations when analyzing, interpreting, and disseminating findings. First, she emphasized that some women are unable or unwilling to accurately report what and how much they consume. More frequent assessments can help them recall details about their intake during the target period, but this does not obviate the need for a plan to handle missing or incomplete data (e.g., exclusion or imputation). A second limitation, she continued, is that regulatory guidance permits a dietary supplement’s labeled (quantitative) contents to vary from its actual contents by up to 20 percent. The Dietary Supplement Ingredient Database developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the National Institutes of Health provides adjusted values for all supplements based on lab analyses of each product type;1 Sauder acknowledged that discrepancies between labeled and true contents invariably introduce error into micronutrient intake analyses. Moreover, she added, a supplement may contain contaminants that interact with its other ingredients or have implications for the health outcomes under study. Sauder appealed for the use of biomarkers of nutrient intake to mitigate the limitations of estimating intake using standard dietary assessment tools.

DIETARY ASSESSMENT DURING PREGNANCY: PERSPECTIVE FROM A NUTRITIONAL PHENOTYPING COHORT

Beth Widen, assistant professor in the Department of Nutritional Sciences at The University of Texas at Austin, discussed a study in progress called the Mother and Infant Nutrition Study (MINT), with an emphasis on

___________________

1 See https://dietarysupplementdatabase.usda.nih.gov/index.php (accessed August 24, 2021).

its dietary assessment methods and preliminary learnings. Widen explained that MINT, an intensive nutritional phenotyping cohort, was designed to examine weight and body composition changes and their determinants (including diet and physical activity) during pregnancy. A second objective, she said, is to examine interrelationships between maternal body composition and weight change trajectories and how each type of change relates to neonatal adiposity.

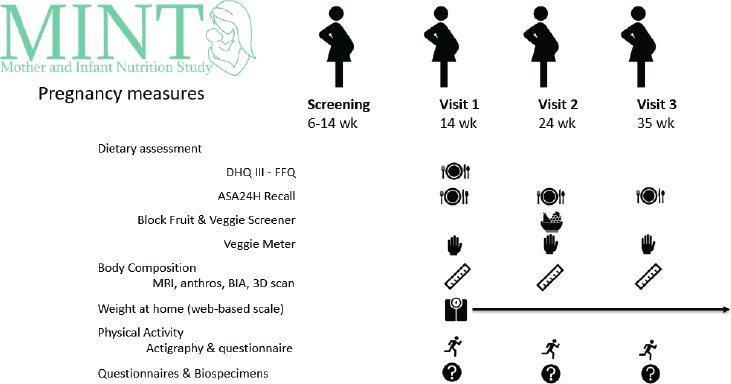

Widen described the study’s methods for assessing weight, body composition, diet, physical activity, and related measures (see Figure 2-1), emphasizing that participant burden was a key consideration when choosing assessment tools and timing.

Screening of prospective participants aligns with early prenatal care (6–14 weeks gestation), she said, and enrolled participants’ first study visit occurs after the first trimester, at 14 weeks. Ideally, this timing also coincides with a subsiding of the nausea and vomiting that commonly occur during the first trimester. The visit at week 14 includes a series of body composition measures—whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) assessment of body composition, anthropometry, bioelectrical impedance analysis, and a three-dimensional body scan to calculate percent body fat—along with the provision of a web-based scale for participants to take home

NOTE: anthros = anthropometry; ASA24H = Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Dietary Assessment Tool; BIA = bioelectrical impedance analysis; DHQ III-FFQ = Diet History Questionnaire III-Food Frequency Questionnaire; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; wk = week.

SOURCE: Presented by Beth Widen, May 6, 2021.

for weekly monitoring; physical activity assessment with actigraphy and a questionnaire; and biospecimen collections and additional questionnaires assessing demographic variables, weight and medical histories, diet and eating behaviors, sleep, stress, depression, and beliefs about pregnancy. The second (week 24) and third (week 35) study visits repeat the body composition, physical activity, and biospecimen assessments completed during the first visit to track changes over time.

Widen elaborated on MINT’s dietary assessment strategy and explained how it evolved beyond the study team’s initial plans. Participants’ first visit (week 14) includes both an FFQ and a 24-hour dietary recall, she said, but only the latter is repeated at the second and third study visits in an effort to balance the need to track changes over time with the desire to mitigate participant burden. The study context called for the FFQ to be web based, relatively low in cost, and available in English and Spanish, which led to the choice of the Diet History Questionnaire III (DHQ-III) tool. During the study’s design phase, the DHQ-III was available in versions that assessed the prior month or prior year of intake. The 1-month version was selected based on its potential to focus more narrowly on the period encompassing the first trimester, Widen said, in order to document early pregnancy-specific dietary changes that may have resulted from food aversions, nausea, or other changes that would not necessarily be reflected in the FFQ covering the prior year. A web-based, 3-month, or even trimester-specific FFQ would have been ideal, she commented, but such FFQs were not available at the time. For currently enrolled MINT participants, Widen reported a DHQ-III completion rate of 89 percent for participants who completed their baseline visit prior to May 2021.

The 24-hour dietary recalls are self-administered by participants using NCI’s Automated Self-Administered 24-hour (ASA24) Dietary Assessment Tool, Widen said; the recalls are performed at each of the three study visits. An interviewer-administered 24-hour recall tool would have been preferred, she reflected, but the ASA24 was selected for its advantages with regard to cost (free), participant burden (relatively low), format (web based), and language availability (English and Spanish). According to Widen, two limitations of the tool for the MINT study population are a lack of foods from a broad variety of Hispanic cultures and the challenges and time burden associated with coding mixed dishes from other cultures, such as chicken masala curry. Even though the ASA24 is designed to be automated and self-administered, she said, participants initially completed at least the first visit’s recall alongside a member of the study team in case they needed help navigating the web-based interface. Because the COVID-19 pandemic has limited the duration of in-person visits, Widen said that participants are now instructed to complete the assessment at home for a typical day of eating. She reported a current ASA24 completion rate of 91 percent for visits completed prior to May 2021.

Widen next touched on two rapid dietary assessment tools that were not part of MINT’s initial design but which were added later in the study planning process: a fruit and vegetable screener and the Veggie Meter. The Block Fruit/Vegetable/Fiber screener (Block et al., 2000) is administered at the second visit (week 24) and enables the ranking of participants’ fruit and vegetable intakes based on consumption during the prior month. The study’s completion rate for the screener is 92 percent prior to May 2021. The Veggie Meter, Widen continued, is a noninvasive device that quickly assesses skin carotenoid status using reflectance spectroscopy. She characterized the measure as exploratory, as she was unaware of other studies that have used or calibrated it among pregnant women. The tool is administered at all three study visits, with a completion rate of 100 percent among women who have had in-person visits.

Widen briefly reviewed MINT’s additional dietary-related measures as well as a separate measure intended to help contextualize the data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Mindful Eating Questionnaire (Framson et al., 2009) and the U.S. Adult Food Security Survey (Bickel et al., 2000) are administered at all three study visits. The Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (Fairburn and Beglin, 1994) is included during the first visit, and two brief questions on pica are asked at both the second and third visits. Because the study was implemented both pre- and post-COVID, Widen pointed out, the team designed semistructured qualitative interviews to assess how the pandemic affected eating behaviors, diet, activity, mood, and health among participants who enrolled prior to the pandemic.

Information about prenatal outcomes, medications, and complications are also collected, Widen said, which may be affected by diet and vice versa. Separate medication and supplement questionnaires are administered at all three study visits and augment information captured in the ASA24 dietary recall. Medications to control nausea are of particular interest, she said, as that information can provide insight into appetite and eating behaviors. The MINT study team also collects general pregnancy information at the third study visit, including information about development of any complications (e.g., gestational diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia), the study team creates abstracts of the information contained in prenatal care and hospital records to supplement that information.

Although MINT is still collecting data, Widen explained, the study team has developed initial guidelines for data cleaning and analysis. These include checking for missing data and adapting the low and high calorie cut points for implausible intakes based on trimester-specific needs. Widen said the team checks the 24-hour recalls for outliers in both portion size and nutrient intakes, checks for large gaps in timing between meals and snacks, and adjusts for weekend day recalls. Season of intake is also considered, she added, for both the 24-hour recall and the FFQ. These considerations

will not only help the team interpret the study’s findings but will also help the team compare results from each of the dietary assessment measures to assess concordance.

In summary, Widen emphasized that MINT’s best dietary assessment tool options were web based in light of the study’s logistics and participant burden considerations. Other desirable characteristics of the web-based tools, she said, were rapid administration, linkage to updated food databases, and the integration of questions on nausea and vomiting.

A FRENCH-CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE ON DIETARY ASSESSMENT DURING PREGNANCY

Anne-Sophie Morisset, researcher at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire at the Québec–Laval University Research Center and professor at the School of Nutrition at Laval University, provided a French-Canadian perspective on dietary assessment during pregnancy. She described a web-based tool to assess dietary intakes, presented information about a study that aimed to validate the tool in pregnant women, shared results from dietary assessments during pregnancy, and offered lessons learned.

A self-administered, web-based, 24-hour dietary recall tool for the French-Canadian population (Jacques et al., 2016) was inspired by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Automated Multiple-Pass Method (Moshfegh et al., 2008), Morisset said. This recall tool was validated to evaluate adherence to Canadian dietary guidelines (Lafrenière et al., 2018, 2019). The tool uses a meal-based approach, she explained, and allows study participants to select from a large, structured list of food items and recipes representative of common foods among Quebec consumers. The tool also asks questions about a meal’s context, includes pictures alongside the response options for portion size, and provides an opportunity for participants to select additions that they might otherwise forget to report for certain food and beverage items (e.g., added ingredients or toppings, such as cheese or hummus on a bagel).

To improve response rates and minimize errors, she said that the tool sends emails to participants instructing them to complete the recall; if they do not complete it within 24 hours, a new recall date is automatically updated in the system. Completion of a single day of recall takes about 20 to 30 minutes, Morisset reported, and studies ideally aim to collect three recalls, two on weekdays and one on a weekend day. The tool’s data report includes nutrient intakes, food group servings based on the 2007 Canada’s Food Guide, and diet quality based on the Canadian Healthy Eating Index (C-HEI) (Garriguet, 2009).

Morisset described an additional web-based questionnaire that gathers information about dietary supplement intake. Participants answer five ques-

tions about their dietary supplement use (including product name, drug identification number, dose with units of measure, and frequency) during the prior month and may enter up to 10 different dietary supplements. The drug identification number connects to the product’s micronutrient content data in Health Canada’s Natural Health Products Database. Data from that questionnaire can be added to the dietary data from the dietary recall, thus providing an estimate of total nutrient intakes from food and supplements.

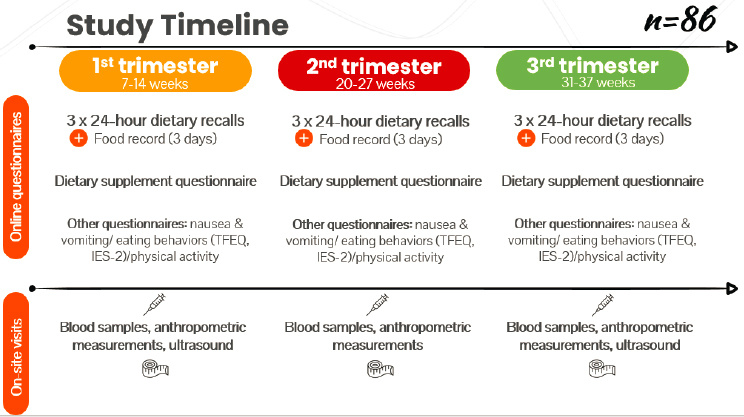

Morisset turned to discuss her lab’s Apports Nutritionnels durant la Grossesse (ANGE) study, which in English translates to Nutritional Intakes During Pregnancy. Its objectives are to validate the web-based, 24-hour dietary recall tool among pregnant women and to assess and measure changes in dietary intakes throughout trimesters and compare intakes with Canadian dietary guidelines. During each trimester of pregnancy, the study used online tools to administer three 24-hour dietary recalls, one 3-day food record, a dietary supplement questionnaire, and other questionnaires to assess nausea, vomiting, and eating behaviors as well as physical activity. During the on-site visits that occurred each trimester, the study collected blood samples and anthropometric measures, and at the first and third visits it also conducted ultrasounds (see Figure 2-2).

Morisset presented results from the ANGE study, beginning with validation of the web-based, 24-hour dietary recall tool among pregnant women.

NOTE: IES-2 = Intuitive Eating Scale-2; TFEQ = Three-Factors Eating Questionnaire.

SOURCE: Presented by Anne-Sophie Morisset, May 6, 2021.

The final sample was restricted to data from women who completed both the food record and all three 24-hour dietary recalls in each trimester, she said, and results indicated that the tool is a valid method to assess intakes of energy and most nutrients (Savard et al., 2018b).

The study team also examined trimester-specific dietary intakes based on data from 79 women and estimated that energy intake was stable over time (Savard et al., 2018a). This suggests that most women exceeded energy needs during the first trimester, she said, whereas the contrary occurred during the third trimester. Morisset shared additional study findings for macronutrients: relatively stable macronutrient intake over time, protein intake within the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR), carbohydrate intake below the AMDR for approximately one-quarter of participants, and total fat intake over the AMDR for approximately half of participants.

With respect to micronutrients, Morisset said that most women in the ANGE study reported taking at least one dietary supplement, typically a multivitamin and mineral product. She emphasized that these supplements made an important contribution to achieving the recommended levels of key micronutrients during pregnancy, such as folic acid, vitamin D, and iron. For example, folic acid intakes from food alone were below the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) for about 60 percent of participants, but only 10 percent of participants had intakes below the EAR after adding intakes from dietary supplements. Similarly, the highest women’s intakes of vitamin D and iron from food alone were below the EAR for those micronutrients, but only 20 percent had total intakes below the EAR after adding intakes from dietary supplements.

The ANGE investigators also assessed changes in participants’ diet quality using the 2007 C-HEI (Savard et al., 2019). Morisset pointed out an apparent decrease over the course of pregnancy in overall dietary quality, along with statistically significant decreases in the index’s subscores for adequacy, total vegetables and fruits, unsaturated fats, and saturated fats. Lower C-HEI scores were observed among younger women with no university degree and with poorer nutrition knowledge.

Morisset finished by offering lessons learned for studies of dietary assessment during pregnancy, beginning with the affirmation that use of a web-based dietary recall was informative to, and appreciated by, participants. She emphasized both the importance of recruitment strategies to enroll women early in pregnancy and conducting on-site visits to build trust between participants and investigators. Despite finding stability in dietary intake during the course of pregnancy, Morisset contended that additional longitudinal assessments are warranted to better understand the apparent consistency in overall dietary intake and explore observed decreases in diet quality. She noted that the ANGE study’s relatively small sample size pre-

cluded observation of associations between dietary intake and pregnancy outcomes or gestational weight gain. In closing, Morisset reminded the audience that no dietary assessment tool is perfect, underscoring the importance of combining traditional tools with objective measures to obtain a clearer picture of intake (e.g., Savard et al., 2021).

ANALYTICAL METHODS TO ESTIMATE DIETARY INTAKE DURING PREGNANCY

Daniela Sotres-Alvarez, associate professor in the Department of Biostatistics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, rounded out the discussions about dietary assessment during pregnancy with a presentation on analytical methods, which she noted were applicable to populations beyond pregnant women.

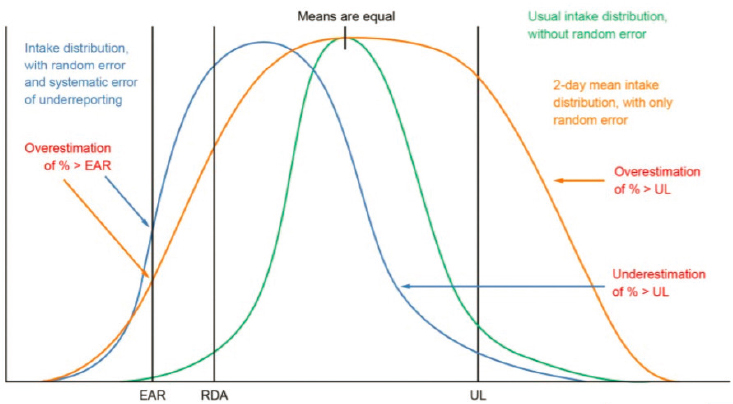

Beginning with the types of measurement error in self-reported dietary intake (usual intake), Sotres-Alvarez described random error and systematic error. Random error results from day-to-day variability in intake, she explained, whereas systematic error arises for various reasons such as general bias, person-specific bias (e.g., by age, body mass index, social desirability), or intake-related bias (e.g., individuals with high intakes underreport and individuals with low intakes overreport). The effect of measurement error depends on the type of error present and the type of results reported, such as distribution of usual intakes or association between dietary intake and a health outcome.

Sotres-Alvarez reviewed additional types of information needed to account for measurement error. Repeated measures of dietary intake, for instance, can reduce the variability in intake for an individual. Covariates can also be used to identify specific biases, she continued, and recovery or concentration biomarkers can also be used to help validate self-reported instruments. Sotres-Alvarez pointed out that biomarkers are typically only assessed for a subsample of participants because of cost (e.g., doubly-labeled water to estimate energy expenditure) or high participant burden (e.g., 24-hour urinary collection to estimate sodium intake).

Sotres-Alvarez displayed a graph to describe the effect of random error in estimating usual intake distribution (see Figure 2-3). Compared to the true intake distribution, an intake distribution affected by random error will report the same mean intake but will have a wider distribution. When systematic error is present, even with multiple days of recall, which makes the tails less wide (compared with the true intake), the curve will shift and bias estimates. Consideration of bias is critical when the tails of a distribution are of interest, she noted, such as for estimating the proportion of a population meeting a particular dietary requirement or exceeding the Tolerable Upper Intake Level for a nutrient.

NOTE: EAR = Estimated Average Requirement; RDA = Recommended Dietary Allowance; UL = Tolerable Upper Intake Level.

SOURCES: Presented by Daniela Sotres-Alvarez, May 6, 2021; Bailey et al., 2019a.

Sotres-Alvarez shifted to discuss estimating usual intake from foods and beverages using multiple 24-hour recalls or food records. From a list of six well-known methods, she focused on the NCI method to model usual intake (Tooze et al., 2006, 2010), which she said is the most widely used in the United States. The NCI method can be used for nutrients or food groups that are consumed daily (where it models the amount consumed) or episodically (where two steps are performed to model the amount as well as the probability of consuming that specific food on any given day). According to Sotres-Alvarez, this analytic technic accounts for day-to-day variability in individual intakes and accommodates highly skewed variables; it also helps explain some of the variability in an estimate by relating covariates to usual intake. This method estimates distribution for a population or subpopulation, she said, and at least partially corrects bias caused by measurement error in estimated associations between usual dietary intakes and health outcomes.

Sotres-Alvarez pointed out a major caveat of the NCI method, which is that it assumes the reference instrument is unbiased of the true usual intake. She alerted the audience to the availability of SAS macros for the NCI method,2 which facilitate modeling of single nutrients or food

___________________

2 See https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/diet/usualintakes/method.html (accessed September 14, 2021).

groups, ratios of two dietary components that are consumed on a near-daily basis (e.g., usual sodium intake per 1,000 calories), and multiple dietary components whether consumed daily or episodically (e.g., Healthy Eating Index).

Additional analytic considerations come into play, Sotres-Alvarez said, when estimating usual intake from not only foods and beverages but also from dietary supplements (Bailey et al., 2019b). Measurement error from both foods and supplements is important to consider, although the structure of measurement error from dietary supplements is not as well characterized as it is for foods. Including supplements in intake distributions can lead to more skewing, spiking (resulting from common dosages of the supplement), and multimodal distributions (if supplement users have higher dietary intakes, compared with nonusers, of the same nutrient present in the supplement). Furthermore, dietary supplement users are more likely to have greater access to health care and higher educational attainment, Sotres-Alvarez noted, which can lead to differential measurement error between supplement users and nonusers.

Sotres-Alvarez reviewed methods to account for dietary supplement use in estimates of total usual intake of foods and supplements. No single method exists, she said, explaining that the best method for a given situation is context specific in that it depends on the research question, population characteristics, sample size, and proportion of the population consuming dietary supplements. She summarized three categories of methods for estimating total usual intake, accounting for dietary supplements (Bailey et al., 2019a). One is the combined method, which adds dietary supplement intake to dietary intake to generate the distribution with users and nonusers examined together as one group. Within-person variability can be captured before including the supplements in the intake distribution (i.e., the “shrink then add” approach, which Sotres-Alvarez said is the preferred approach) or after they are included (i.e., the “add then shrink” approach).

A second category is the stratified analysis, in which separate distributions are generated for dietary supplement users and nonusers. A third category is a hybrid model, which uses a three-part approach that first models intake from either foods plus supplements or foods only (depending on whether the participant is a supplement user or nonuser) and then estimates the probability of consuming a dietary supplement on a given day. She highlighted one analysis of total usual dietary intakes of pregnant women in the United States (Bailey et al., 2019b), which indicated that dietary supplement users (compared to nonusers) were far less likely to have intakes below EAR values for both folate and iron.

Sotres-Alvarez next explained that if measurement error is not taken into account, then associations between usual dietary intake and a health outcome can be attenuated or inflated; most of the time, they are attenu-

ated. This limitation can be mitigated with a technique called regression calibration if recovery biomarkers are available. In this technique, she explained, a recovery biomarker is regressed on the estimated intake as measured by a dietary assessment instrument (i.e., with error) to calibrate the intakes. Typically, recovery biomarkers are available for only a subsample of the study population, so the predictive value of the biomarker is applied to the full population to assess any association that may exist. Sotres-Alvarez said that this approach helps reduce bias in any reported associations. Resources to learn more about these topics include the NCI’s measurement error webinar series and dietary assessment primer.3,4

Q & A SESSION

Following the four presentations, speakers answered questions from the members of the workshop series planning committee. These questions were about a variety of topics, including dietary supplements when exploring associations between nutrient intakes and outcomes, strategies to address social desirability bias, strength of current reference values for nutritional intake during pregnancy, assessing sugar-sweetened beverage intake during pregnancy, including ethnic- and culture-specific foods and beverages in assessment tools, approaches to account for pregnancy-associated changes in taste preferences, modifying administration of dietary assessment tools based on social factors, using biomarkers and other analytical strategies to improve estimates of usual intake, and choosing complementary assessment tools and combining data.

Including Dietary Supplements When Exploring Associations Between Nutrient Intakes and Outcomes

In the context of a high prevalence of dietary supplement use among pregnant women, Siega-Riz asked if supplement intakes should be included in the examination of associations between nutrient intake and health outcome of interest. Morisset suggested that it depends on the research question and outcome of interest. For instance, an outcome such as insulin resistance would benefit from examination of vitamin D intakes from supplements, but if the goal relates to healthy eating habits during and beyond pregnancy, perhaps only intakes of food and beverages could be used. Building on this concept, Sauder suggested that assessing dietary supplements is critical when they make key contributions to intakes during pregnancy. Evidence suggests that this is the case for folic acid, she said,

___________________

3 See https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/events/measurement-error (accessed August 30, 2021).

4 See https://dietassessmentprimer.cancer.gov (accessed August 30, 2021).

and pointed out that this vitamin’s role as a methyl donor makes it important to assess intakes from both food and supplements in examination of the relationship between micronutrient intakes and DNA methylation, for example. Widen added that she thought it would be informative to show results both with and without inclusion of dietary supplements in analyses.

Strategies to Address Social Desirability Bias

Lisa Harnack, professor in the School of Public Health at the University of Minnesota, asked the speakers how they have tried to minimize social desirability bias in pregnant women’s reporting of dietary intake. Morisset responded that her team’s web-based dietary recall and questionnaires do not require direct interaction with the researchers but acknowledged that this approach does not necessarily preclude participants from providing socially desirable responses. Nonetheless, based on the low diet-quality scores reported by participants in the ANGE study, she contended that this dietary assessment method maintains some accuracy. Widen and Sauder both emphasized the importance of building rapport and creating mutually respectful, nonjudgmental relationships with study participants as a strategy to encourage disclosure of complete and accurate information.

Strength of Current Reference Values for Nutritional Intake During Pregnancy

Dana Dabelea, professor of epidemiology and pediatrics and director of the Lifecourse Epidemiology of Adiposity and Diabetes Center at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, wondered about the strength of current guidelines for intakes of energy, macronutrients, and micronutrients during pregnancy, particularly in light of the ANGE study’s results indicating stable intakes of some components. She asked what type of studies would be helpful to support potentially revised recommendations for energy and nutrient needs during pregnancy, including the role that dietary supplements play. Morisset admitted that her team was surprised by the observation of stable energy intake over the course of pregnancy, and the team is currently examining regulators of appetite and measuring basal metabolic rate during pregnancy. She hypothesized that estimated increases in energy requirements during pregnancy may not correspond to what is possible because of changes in appetite. Widen called for consideration of individual variation in energy intakes and suggested that the relative energy needs during pregnancy may need to account for prepregnancy weight status and energy intake. Sauder pointed out that approximately 20 micronutrients have pregnancy-specific Dietary Reference Intakes values, only about half of which are derived from studies conducted in pregnant

populations. Rather than simply characterizing pregnant women’s intakes, Sauder appealed for rigorous studies—ideally including the assessment of both food and supplement intakes as well as biomarkers—that follow women from preconception through delivery to appropriately determine their energy and nutrition needs during pregnancy.

Assessing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake During Pregnancy

Erica Gunderson, epidemiologist and research scientist in the Division of Research at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, raised the topic of sugar-sweetened beverage intake during pregnancy and its relationship to child health outcomes. She asked the speakers if intake of these beverages during pregnancy would be a valuable screening question. Siega-Riz relayed an anecdote of a study participant who reported excessive consumption of a sugar-sweetened beverage, but not until nearly halfway into an 8-week intervention because she did not consider it a food. Siega-Riz reiterated speakers’ previous comments about creating rapport with study participants and emphasized the importance of considering both food and beverages in intake assessment. Morisset noted that her team has not assessed sugar-sweetened beverage intake specifically but could use existing ANGE data to do so in the future.

Including Ethnic- and Culture-Specific Foods and Beverages in Assessment Tools

Esa Davis, associate professor of medicine and clinical and translational science at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, asked about the diversity of ethnic and cultural foods and beverages in dietary assessment tools. Widen said that her team often has to manually code certain ethnic foods into the 24-hour recall system, which she admitted is challenging because it requires substantial estimation and time, even for commonly consumed ethnic foods. Sauder suggested that if a particular food or beverage is not present in the assessment system, researchers could store away the information on the chance that the food or beverage may be included in the system’s next update, at which point it could be added to the participant’s record retrospectively (but if not, the staff-coded version of the item may be put in). With respect to the tool used in the ANGE Study, Morisset noted that it was created to reflect dietary habits of Quebec consumers but recognized there was room for improvement and future updates in response to changes in habits.

Approaches to Account for Pregnancy-Associated Changes in Taste Preferences

Steve Daniels, professor and chair of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, pediatrician-in-chief, and L. Joseph Butterfield Chair in Pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Colorado, asked how researchers could consider the effects of pregnancy-specific changes in taste preferences on dietary intake. Widen suggested that such information could be obtained through qualitative interviews, although she acknowledged the challenge of implementing this strategy in a large study population. Morisset’s team uses a web-based questionnaire about cravings and food aversion, both of which she said tended to decrease during the course of pregnancy and do not appear to be associated with diet quality or total intakes. Sauder added that one of the challenges to understanding cravings and food aversions is the lack of a preconception baseline to be able to identify actual shifts in dietary preferences and intakes.

Modifying Administration of Dietary Assessment Tools Based on Social Factors

Cheryl Anderson, professor and dean of the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science at the University of California, San Diego, asked the speakers how the use of dietary assessment tools might be modified based on participants’ sociodemographic or socioeconomic status. Widen reported that her team provides hands-on support and extra assistance to participants with lower levels of education and socioeconomic indicators, but she admitted that the time burden of this approach makes it not feasible to apply to all study participants. Sauder noted that with dietary supplements, participants from all backgrounds can be educated on what constitutes a dietary supplement and encouraged to bring their products to interviews rather than relying on memory. She referenced a lack of evidence to suggest the influence of factors such as education and socioeconomic status on pregnant women’s ability to accurately recall dietary intake.

Using Biomarkers and Other Analytical Strategies to Improve Estimates of Usual Intake

Potischman followed up on Sotres-Alvarez’s comments about recovery biomarkers by questioning the appropriateness of using concentration biomarkers in a similar manner, given large within-person variation in plasma volume expansion during the course of pregnancy. Sotres-Alvarez agreed that such variation poses a challenge to using concentration biomarkers to

validate dietary intake, in addition to the limitation that few recovery or concentration biomarkers for nutrients exist.

Gunderson asked Sotres-Alvarez what could be done to reduce error in estimates of usual intake in the absence of biomarkers, particularly when considering diet quality. Sotres-Alvarez acknowledged that predictive biomarkers have not been identified for the intake of specific foods and food groups, but she reiterated the value of combining results from different dietary assessment instruments to mitigate effects of random error. Emphasizing that within-person variability typically affects distributions of intakes and attenuates relationships between intake and outcomes, she advocated for the collection of repeated measures of dietary intake (at least in sub-samples of the study population) and use of the NCI analytical method to reduce this variability. As an example, Sotres-Alvarez said that a food propensity questionnaire could be included as a covariate or indicator of whether a participant is taking a dietary supplement.

Choosing Complementary Assessment Tools and Combining Data

Dabelea asked how to approach combining data on the intake of micronutrients from foods and beverages and from dietary supplements when different tools were used to assess those two sources, such as in the context of a large study population. Sotres-Alvarez explained that in addition to the strategy of collecting multiple records for total food and beverage intake, it is ideal to have dietary supplement intake data for the same time period. She suggested that data from different tools could be complementary. For instance, dietary supplements may not be taken on a 24-hour recall day, but they may still be consumed—a questionnaire with a longer reference period (e.g., previous 30 days) could capture this information that would otherwise be missing if based on recall data alone. The more information collected, she reiterated, the more confidence that a less biased estimate is being obtained.

PANEL DISCUSSION

In the final segment of the workshop, audience members submitted questions for the speakers. The questions centered around considerations related to assessing dietary supplement intake, suggestions to address limitations of food frequency questionnaires, and frequency of dietary assessment during pregnancy.

Considerations Related to Assessing Dietary Supplement Intake

An attendee pointed out that nutrient biomarkers do not necessarily provide information about the relative contributions of foods and dietary supplements to total intake and asked how to interpret biomarker data when trying to differentiate the effects of intake from foods versus from supplements. Sauder explained that total intake of a nutrient and the amount bioavailable for maternal and fetal nutrient stores are the exposure of interest, regardless of source. When asked if micronutrients consumed in dietary supplements have the same biological effect if consumed in food, Sauder suggested that most do but emphasized that the amount consumed at one time is an important factor because maximal absorption and storage capability differs among micronutrients.

The same attendee also asked how to account for factors that could affect bioavailability, such as interactions between nutrients in a dietary supplement or existence of different chemical compositions for a particular nutrient across supplement brands, particularly in the absence of biomarker data. Sauder referenced the interdependence of both micronutrients and macronutrients in admitting that this is a broad challenge in nutrition research, and she pointed out the importance of considering this limitation when interpreting findings. She suggested that more highly controlled, mechanistic studies during pregnancy are warranted to improve understanding in this area.

Another attendee questioned the state of knowledge on prevalence and frequency of prenatal dietary supplement use. Siega-Riz recounted her early research that examined this topic using a supplement container cap that monitored frequency of use, which she said found little correlation with self-reported intake (Jasti et al., 2005). She suggested that the discrepancy could result from social desirability bias and possibly from decreased compliance with dietary supplement use as pregnancy progresses. In terms of the feasibility of objective measures of intake, Siega-Riz noted that the cost of supplement container cap monitors would likely preclude their widespread use and suggested that a biomarker assay may be a more feasible strategy to differentiate dietary supplement users from the nonusers.

Suggestions to Address Limitations of Food Frequency Questionnaires

Another attendee questioned the usefulness and accuracy of food frequency questionnaires, referencing this tool’s reliance on the respondent’s memory combined with what is usually a short time allotment for the respondent to complete the assessment. Sauder remarked that many investigators opt to use 24-hour recalls or food records in light of the limitations

of FFQs, although some research groups have developed and validated FFQs that cover a shorter reference period (e.g., less than 1 year). Nonetheless, she continued, even modified FFQs come with challenges to obtaining accurate assessment of an individual’s dietary intake, particularly when seasonality is a factor.

Another participant wondered if adding a list of common prenatal supplements to FFQ tools would helpful for pregnant populations. Widen suggested it might be beneficial, but cautioned that frequent changes in supplement availability and formulations might outpace a tool’s ability to reflect the current state of the marketplace.

Frequency of Dietary Assessment During Pregnancy

With evidence from the ANGE study about stability in intakes over the course of pregnancy, an attendee questioned the necessity of conducting dietary assessment in each trimester. Siega-Riz inferred that if additional evidence indicates that dietary intakes are stable throughout pregnancy, then future studies could reduce participant burden by collecting fewer dietary assessments. Nonetheless, she appealed for collecting multiple intakes on a subsample of the study population to account for variability among the entire sample. Sotres-Alvarez agreed and added that the number of dietary recalls or food records needed for this purpose depends on the nutrient of interest.

Building on this point, Widen suggested that assessment timing depends on whether the nutrient of interest is known to have a specific effect at a specific time. Rather than administer a full dietary assessment at the time period of interest, she suggested that a strategy such as asking brief screening questions could provide the information needed for the specific research question. Gunderson illustrated Widen’s suggestion with the example of folate, noting that adequate intake during the periconceptional period is critical to helping prevent neural tube defects.

Dabelea guided the discussion back to the need to validate the ANGE study’s findings about stability of dietary intake over the course of pregnancy in larger and more diverse populations. If validated, she proposed collecting dietary intake using several different types of tools during the time period that is most critical to the research question, rather than focusing solely on multiple longitudinal methods of assessment.