The fourth and final workshop in this series, held May 24, 2021, featured five presentations about innovations and special considerations in assessing dietary intake during pregnancy and in children 2 to 11 years of age. It also included a question-and-answer session for the workshop sponsors and planning committee members to ask questions of the speakers, as well as a moderated panel discussion that included nine panelists, most of whom were speakers at one of the four workshops in the workshop series. Presentation topics included key considerations when developing and implementing dietary assessment methods, emerging technologies as opportunities to measure dietary intake, potential for ecological momentary assessment in dietary intake research, harmonization of methods for dietary assessment, and matching a research question to the appropriate dietary assessment method and statistical analyses.

Amy Herring, Sara and Charles Ayres Distinguished Professor of Statistical Science at Duke University and member of the workshop series planning committee, began the workshop with a recap of key points about the challenges associated with dietary assessment during pregnancy and childhood. According to Herring’s summary, these include unique characteristics of those life stages that influence intake (e.g., nausea and vomiting during pregnancy) and cognitive capacity to recall intake (e.g., limitations in these abilities during early childhood), uncertainty about the ideal frequency of data collection, and other challenges that are inherent to dietary assessment at all stages of life (e.g., variability of intake and the social desirability bias of respondents). Although these myriad challenges complicate decisions about study design, Herring conveyed that they also provide exciting challenges for analysts, statisticians, and data scientists after the data have been attained. As an example, she said that combining results from multiple studies in a systematic review and meta-analyses can be daunting, especially when the included studies used a variety of assessment approaches and tailored them to their study populations. Even when sophisticated statistical models are applied to help address bias, Herring maintained that they are no substitute for perfectly accurate intake data, if they were attainable.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR DEVELOPING AND IMPLEMENTING DIETARY ASSESSMENT METHODS

Carmen Pérez-Rodrigo, professor in the Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of the Basque Country in Bilbao, Spain, reviewed key considerations for developing and implementing dietary assessment methods. She focused on specific features of a participant group that can influence reporting about intake behaviors, such as diversity and food literacy, and suggested some approaches to designing a study to help minimize misreporting.

Pérez-Rodrigo started by briefly restating key points from the workshop series’ prior workshops, highlighting that that the ideal level of accuracy to be attained in dietary intake research depends on the research purpose, context, target population, and resources. For surveillance purposes, for example, she pointed out that although the target population might be quite diverse, researchers must collect the same amount of dietary intake data from its various subgroups to ensure that the data are of uniform quality. Resources available for that purpose are often limited, she admitted, which restricts the types of methods or technologies that may be incorporated. Researchers are tasked with striking a balance when making decisions about a dietary assessment method, level of information to collect, and population to include.

Pérez-Rodrigo reviewed six issues to consider when planning dietary assessment research with children. First, their cognitive abilities such as

memory, concept of time, and attention span vary by age. Children have limited abilities to report portion size and frequency of consumption in particular, she added, without help from a caregiver. Second, food literacy may be a constraining factor as children may have limited vocabulary for naming foods, as well as difficulties identifying food preparation methods, main ingredients in mixed dishes, and condiments. Third is surrogate reporting, Pérez-Rodrigo said, referencing the collection of data from multiple reporters such as parents and other caregivers. She indicated that involvement of multiple reporters could heighten the relevance of the fourth issue, social desirability bias, which she said may be introduced by both children and their surrogate reporters. Children’s dietary habits are a fifth issue, particularly for older children who regularly consume meals and snacks outside the home. Sixth, she noted other considerations that can influence dietary intake reporting, such as the child and parent’s weight status, body image concerns, and presence of restrictive eating behaviors. Lastly, she emphasized motivation as an overarching consideration, explaining that children’s attention to and active engagement in the reporting activity is critical.

Shifting to discuss misreporting, Pérez-Rodrigo highlighted the importance of considering who tends to misreport, what kind of foods are misreported most often, and why the misreporting occurs. Older children are more likely to underreport, she indicated, but minimal differences have been reported between gender of reporters. Children from families of lower socioeconomic and educational levels tend to underreport, she continued, but evidence is conflicting with regard to residential area and ethnicity. In terms of the types of foods more likely to be misreported, Pérez-Rodrigo flagged foods consumed outside the family context and snack foods. Overall, she noted that although underreporting is more common than overreporting (Murakami and Livingstone, 2016), children, particularly younger children, are more likely than adults to overreport by introducing foods that were not actually consumed (Forrestal, 2011). In light of these challenges, Pérez-Rodrigo maintained that methodological considerations to avoid or minimize misreporting are crucial, as is qualitative research to further parse questions of who, what, and why with regard to misreporting.

Pérez-Rodrigo turned her focus to the diversity of the population whose dietary intake is being assessed, which she said exists in terms of age, gender, socioeconomic level, residential area, education, ethnicity, culture, language, food literacy, and access to foods. Because food literacy is highly contextual, she pointed out, it is important for food lists and recipes in an assessment instrument to reflect foods likely to be reported by the population of interest. The food composition databases must be equipped with these foods as well. She pointed out a related issue, which is that different people may label the same foods with different names or list different

ingredients in recipes for the same dishes. It has been suggested that having respondents collect wrappers, labels, and packages to supplement children’s food records can aid researchers’ food coding and improve the records’ accuracy (Yonemori et al., 2017). This strategy is less conducive to food frequency questionnaires (FFQs), Pérez-Rodrigo acknowledged, suggesting an alternate strategy of including space on questionnaires for respondents to write in names of relevant foods.

Language and literary are other important components of diversity, Pérez-Rodrigo continued, as they can pose challenges to obtaining appropriately representative population samples.

It is desirable for all of a population’s subgroups to be represented at the same level, she said, but varying levels of literacy within subgroups may undermine their participation. Researchers are encouraged to consider aids that lower the burden of participation for such subgroups, such as involving teachers and social workers to help parents and caregivers report children’s school and other away-from-home intakes (Bartrina et al., 2013) and providing technology for participants to take food photos to supplement their intake reports (Norman et al., 2020).

EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES AS OPPORTUNITIES TO MEASURE DIETARY INTAKE

Carol Boushey, associate research professor in the epidemiology program at the University of Hawaii Cancer Center, shared examples of emerging technologies to measure dietary intake and shared results of studies that used such approaches with pregnant women and children.

Boushey began by contrasting active and passive approaches to improve dietary assessment with digital images. The passive approach employs a wearable camera or other device to collect lots of data (images), without the active engagement of the user. This approach generates an image about every 5 seconds, or around 400,000 images/day that need to be screened. Boushey noted that although most of those images are not related to food, those that do include eating occasions capture around several dozen images of both the before and after scenes to be used for recognition analysis and amounts consumed. Turning to describe the active approach, she explained that users are instructed to capture one image both before and after an eating occasion, typically using a mobile phone, resulting in 6–12 images/day. User engagement in this method generally results in more focused, better-quality images with useful contextual information.

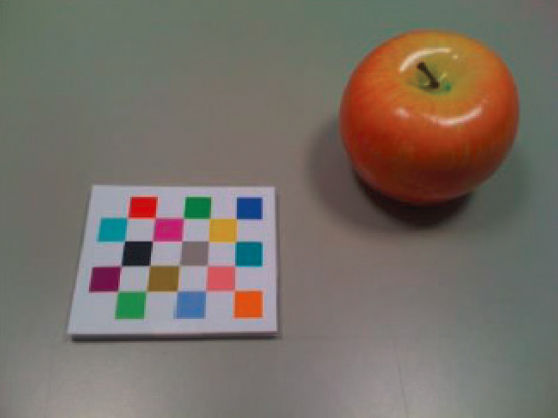

In the context of Boushey’s image-based dietary assessment studies, a fiducial marker which is a colorful checkerboard square that participants place in the camera’s field of view when they take before and after images of eating occasions, appears in each image as a point of reference (see

Figure 5-1). The fiducial marker helps identify the food in the image, she explained, because natural color is an important indicator and the standardized colors on the checkerboard square allow a classifier to designate the food’s original colors if they have been changed because of lighting or other influences when the image was captured (Xu et al., 2012).

Boushey next discussed two examples that used smartphone image-based dietary assessment among pregnant women. One instructed participants (n = 25) to photograph eating occasions (and to include the study’s fiducial marker in each image) and to record voice descriptions of the food and beverage items in each image. The technological infrastructure consisted of a mobile phone with an application called Nutricam where participants collected their pictures and audio voice descriptions. After these data were sent to the study’s website for analysis, she said, a structured follow-up phone call was conducted the following day to clarify the contents of the Nutricam dietary record and to probe for forgotten foods. Researchers compared intakes derived from the image-based assessment to intakes calculated from three 24-hour dietary recalls taken once weekly on random days following the image-based record, Boushey explained, and observed significant correlations between the two methods for energy, macronutrients, micronutrients, and fiber (Ashman et al., 2016; Rollo et al., 2015).

In Boushey’s second example of image-based dietary assessment during pregnancy, 23 obese pregnant women used a smartphone app to capture

SOURCE: Presented by Carol Boushey, May 24, 2021.

images of food consumed. They also underwent dosing with doubly labeled water, she said, to enable comparison of energy intake estimated from the app with energy expenditure from the doubly labeled water. Energy intake from the app was only 63 percent of energy from the doubly labeled water, which Boushey called an unexpected finding (Most et al., 2018). Participation was higher when users captured images with their own mobile phones, she said, and these users also reported significantly higher energy intake than users to whom the study provided a phone (because the study app did not work on those users’ own mobile phones). Carrying two mobile devices might have increased the burden and reduced compliance with the study protocol, she pointed out, therefore it is desirable to have an app that works on every mobile phone.

According to Boushey, studies addressing dietary intakes of pregnant women appear to underuse digital technology. It seems that self-administered web-based questionnaires are more widely used, she observed, and suggested that this method would complement an image-based method (either passive or active).

Shifting to focus on children 2 to 11 years of age, Boushey mentioned a study that assessed the validity and feasibility of an image-based dietary estimation method for preschool children in Head Start.1 Validity was determined in a metabolic research unit using actual weight of the food as the reference method, whereas feasibility of the image-based method was ascertained in Head Start and in the home by assessing three separate lunch and dinner meals. Based on significant correlation between estimated and actual weights, the image-based method was considered valid and feasible for assessing food intake of preschool children (Nicklas et al., 2012). Boushey also mentioned Bekelman’s study (see Chapter 4) in which parents were trained to use the remote food photography method to capture before- and-after dinner meal images for their preschoolers (Bekelman et al., 2019).

Lastly, Boushey described a study to support her contention that children 3–10 years old can use technology-assisted methods for dietary assessment. Conducted in Guam, the study trained children how to use the mobile food record, loaned them mobile devices, and provided fiducial markers to include in their before-and-after images of eating occasions (Aflague et al., 2015). Boushey displayed photos taken by study participants who were 3, 5, and 9 years old, characterizing all as usable images. Nearly three-quarters of the participating children who captured usable images (n = 57) were able to include all of the food and the full fiducial marker in their before-and-after images, she reported, and almost all of those children included all of

___________________

1 Head Start is a program of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that provides comprehensive early childhood education, health, nutrition, and parent involvement services to low-income children and families.

the food in their images. Based on these results, as well as positive child feedback on the mobile food record technology, (e.g., 89 percent said it was easy to use, and 87 percent were willing to do it again) and the fact that all of the children returned the mobile device undamaged, Boushey called this approach promising. Some children didn’t gather images, and younger children appeared to need more reminders to take the images, which Boushey said supported the benefit of enlisting parental or caregiver support and tailoring methods to the child’s age.

POTENTIAL FOR ECOLOGICAL MOMENTARY ASSESSMENT IN DIETARY INTAKE RESEARCH

Katie Loth, assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at the University of Minnesota, explored the potential for ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to be used in dietary intake research. EMA is a tool designed to collect real-time data on dynamic behaviors, psychological states, or environmental contexts, she said, and was designed to respond to the limitations of traditional assessment methods. She further elaborated on the term by breaking down each of its words:

- Ecological: Subjects are studied in their natural environment.

- Momentary: Subjects are asked to describe what they are doing at the near-exact time that the behavior of interest occurs, which helps to limit or avoid retrospective recall bias.

- Assessment: Participants completed multiple assessments per day, allowing for the understanding of within- and between-person variation in behavior.

Loth explained that data collection may be researcher initiated (“signal prompts”) or participant initiated (“event prompts”). In the first case, researchers initiate random assessments for participants to complete multiple times throughout the day. She explained that these typically assess predictors of interest, such as mood or context, at various times prescribed by the study protocol. Participants initiate the second type of data collection, she explained, based on the study’s instructions to report a particular event or behavior that relates to the outcomes of interest, such as dietary intakes and behaviors.

Loth listed several advantages of using EMA, beginning with the opportunity to study behaviors in their natural environment. This method also avoids or at least reduces problems with retrospective recall bias, she pointed out, reiterating that people are asked about behaviors of interest as they occur in near-real time, rather than at a later time. EMA also enables

study of temporal patterns of interest when signal prompts are viewed as predictors and event prompts as outcomes. This allows for the testing of momentary theoretical models that would not be possible to examine if longer time periods elapsed between assessments.

To illustrate the use of this method to assess dietary intake in children, Loth described the EMA protocol in the Family Matters study (Loth et al., 2021). This effort sought to understand how familial factors act as risk or protective factors for predicting childhood obesity among children 5 to 7 years of age, she said, using mixed methods and a longitudinal design. Researcher-initiated prompts asked parents to report on their mood and experience with stressors at various points throughout the day, she said, as well as whether the child had seen them modeling various behaviors that day (e.g., consuming certain types of foods, engaging in physical activity, or watching TV). Participant-initiated prompts asked parents to report any shared eating occasions with their child. When participants initiated a prompt, they were asked to select from a list the types of foods that were served (organized roughly by food group) and then asked which of those foods the child ate. They were also asked questions about other behaviors that occurred during the meal, Loth added, such as watching TV, using a computer or cell phone, or conversing with the child.

When children’s intake of selected food groups as reported by EMA was compared with their intakes as reported by parents using 24-hour dietary recall methodology, Loth reported that concordance was high but differed widely by type of food (Loth et al., 2021). Concordance was highest for sweets and lowest for refined grains, she elaborated, and participants were more likely to report the intake of most foods when reporting via 24-hour dietary recall than via EMA. Concordance was also highest for breakfast and snacks, which she suggested may be because fewer foods were being eaten at these occasions; it was also high when foods were prepared and eaten at home.

In summary, Loth recapped the advantages of EMA as the following:

- EMA is less expensive, and there is a lower burden, compared to 24-hour dietary recall methods.

- Momentary data collection is time stamped and context specific.

- Questions on specific foods or supplements can be included.

- EMA is amenable to temporal sequencing of predictors and outcomes.

She listed disadvantages such as limited details about food preparation and portion size, which precludes calculation of nutrient intake. It is unknown if EMA reduces recall bias or is affected by social desirability bias. The research question is of primary importance, she maintained, and

proposed that researchers consider whether EMA’s strengths bolster the study’s ability to answer the question, as well as whether its weaknesses detract from answering it. Another idea is to pair EMA with a different method such as digital image capture or 24-hour interviewer-led recalls, where she suggested that the strengths of EMA could enhance and complement the data from the other method.

HARMONIZATION OF METHODS FOR DIETARY ASSESSMENT

Diane Catellier, senior statistician at Research Triangle Institute (RTI) International, discussed the harmonization of data from dietary assessment methods. Dietary measures that might be considered for harmonization include intake of energy, micronutrients, or specific foods or food groups, she said.

The need for harmonization is propelled by the recognition that significant stakeholder investments in research warrant or even obligate data sharing and pooling across studies, she said, with the goal of expediting the speed of health-promoting scientific discoveries. A number of government entities are investing in activities to facilitate data aggregation and harmonization, she observed, as well as investing in tools and platforms for data access to maximize the usefulness of publicly funded projects. One example of the National Institutes of Health’s support for data harmonization is its funding of the Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) consortium. Sixty-nine ECHO cohorts representing racial, ethnic, and geographical diversity are contributing data on approximately 35,000 pregnancies and 58,000 children toward the primary objective of creating a harmonized, curated, combined database to help understand the effects of early life exposures (pregnancy to 5 years of age) on child health and development. Diet is one of the exposures of interest, Catellier noted, including intake from the maternal perinatal period through childhood and adolescence.

Catellier outlined the complex process of combining data across studies, which she said works best with a team-science approach that involves statisticians, the investigators involved in the original data collection, and subject matter experts. The first step, she began, is to carefully review the processes and procedures related to data collection. Even when the same measure is used across studies, Catellier cautioned that variation will exist related to the population, language, method of administration, and the processing algorithms. The next step is to document the harmonization process for the measure of interest and include pertinent metadata (e.g., mode of administration, reference period). The metadata step is critical, she emphasized, as it will allow the end user to select eligible studies based on the specific research question and evaluate the effects of measurement methods and

data collection procedures on the overall results. The final step is to evaluate the success of the harmonization process using analytical methods to explore heterogeneity in results and imbalances in the sample size caused by overinfluence of a particular study or subgroup. “Harmonization is not for the faint of heart,” she said as a caveat, emphasizing the commitment of time and resources and the scientific and technical challenges required to determine whether sufficient compatibility exists for aggregation.

Catellier listed examples of metadata that she said deserve consideration when trying to determine the compatibility of dietary data for aggregation. These include the life stage of the population, the informant (self- versus proxy-reported), data collection protocol (e.g., number of recalls, FFQ reference time frame), mode of administration (e.g., online, phone, in person), instrument used (e.g., FFQ, 24-hour recall, remote photography), and version of the instrument, because updates to the instrument itself and the nutrient databases it uses for analysis change over time.

In the remaining portion of her presentation, Catellier reviewed two examples from the ECHO study of harmonization of methods to measure different dietary variables: diet quality and nutrient intake during pregnancy. To preface these examples, Catellier explained that the available dietary data were collected via 24-hour recall (multiple versions of the Automated Self-Administered 24-hour [ASA24] Dietary Assessment Tool and the Nutrition Data System for Research) and FFQs (multiple instruments designed for use in different life stages, based on different reference periods, and some of which included study-specific improvements). The variation in dietary assessment instruments was a challenge for data harmonization.

The harmonization of methods to measure diet quality focused on the Healthy Eating Index (HEI)-2015, Catellier said, and involved a crosswalk2 of output from the various 24-hour recall instruments and versions and another crosswalk of output from the various FFQ instruments and versions. She directed attendees to a website that provides algorithms for calculation of HEI-2015 based on either 24-hour recall or FFQ data.3 According to the distributions of two HEI-2015 subscores (total vegetables and whole grains) for children 2 to 7 years of age and for women during pregnancy, Catellier reported that P values for tests of equality were all statistically significant with the exception of whole grains for children 2 to 7 years of age. Although ECHO deals primarily with extant data, she noted, there could be an opportunity to have cohorts collect both FFQ and ASA24 data from a subsample of participants. That would enable the use of regression calibration methods, she said, to correct for some of the measurement error.

___________________

2 A crosswalk is an anaytical technique to identify or map relationships between different data systems.

3 See https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/sas-code.html (accessed August 30, 2021).

For the example of harmonization of methods to measure nutrient intake during pregnancy, Catellier’s team incorporated data from 15 ECHO cohorts on prenatal diet assessed with either 24-hour recalls or FFQs. They did not combine the data across the two measurement methods, she explained, as the tests for differences in mean intake for each micronutrient between methodologies were all statistically significant. Despite the use of different methodologies and nutrient databases across cohorts and over time, food-based results were similar between methodologies (±10 percent) for most nutrients, including directionality in disparity analyses. The results for dietary supplements varied more between methodologies, she acknowledged, but suggested this might have been because sample sizes varied across analyses.

In her final thoughts, Catellier urged researchers to document harmonization methods, which she asserted is essential for transparency. She also suggested the application of tests of heterogeneity to identify factors that may have an effect on the dietary outcome of interest (stratifying analyses if appropriate). She emphasized the need for considering trade-offs between limiting analyses to a single measurement versus harmonizing, which she explained requires consideration of generalizability, selection bias, measurement error bias, and power. Applying sensitivity analyses is critical here, she emphasized, and can be done with a simple “leave-one-out” analyses (by measurement method or by study) to help understand the potential effect on the overall findings. Lastly, she reminded attendees that it is critical for analysis methods to account for the between-study heterogeneity.

MATCHING THE RESEARCH QUESTION TO THE APPROPRIATE DIETARY ASSESSMENT METHOD AND STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Angela Liese, professor of epidemiology at the University of South Carolina, discussed matching a research question to an appropriate dietary assessment method and statistical analysis. She centered her presentation around two primary themes: first, the concept of multidimensionality, which she described as the presence of multiple foods, nutrients, and other constituents represented in a diet, each of which could be considered its own dimension; and second, the integration of measurement error into study design and into the analysis of observational epidemiologic studies.

Liese addressed multidimensionality by providing three examples of research that each jointly considered food groups and nutrients in epidemiologic analyses. The first used a traditional interaction model to examine how different nutrients or foods interact in their effect on health outcomes (Steck et al., 2007). Researchers calculated postmenopausal breast cancer odds by lifetime intake of grilled, barbecued, and smoked meats, stratified by fruit and vegetable intake during the prior year. Stratification allowed

them to test the interaction between fruit and vegetable intake and that subcategory of meat, she explained, and indicated that intake of the meats was associated with increased odds of breast cancer only among women who reported low fruit and vegetable intake. Furthermore, no association was observed among women with high or typical fruit and vegetable intake, she added, calling the results a typical example of effect modification.

Liese’s second example used an approach based on food groups that explored whether the food source of a nutrient changes its effect on health. This study examined various food sources of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) reported in FFQs from participants in a cohort of youth with type 1 diabetes (Tooze et al., 2020). Using FFQ data, researchers derived the specific amounts of dietary PUFAs delivered by different food groups and modeled the association of each with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Not all of the PUFA-delivering food groups were associated in the same way with LDL, Liese reported, noting that some food group sources were negatively associated (e.g., nuts) and others were positively associated (e.g., refined grains and high-fat chicken). Researchers ran a substitution model to test the effect of replacing PUFA intake from high-fat chicken, for example, with PUFA from nuts, finding an impressive reduction in LDL cholesterol (7.4 milligrams/deciliter).

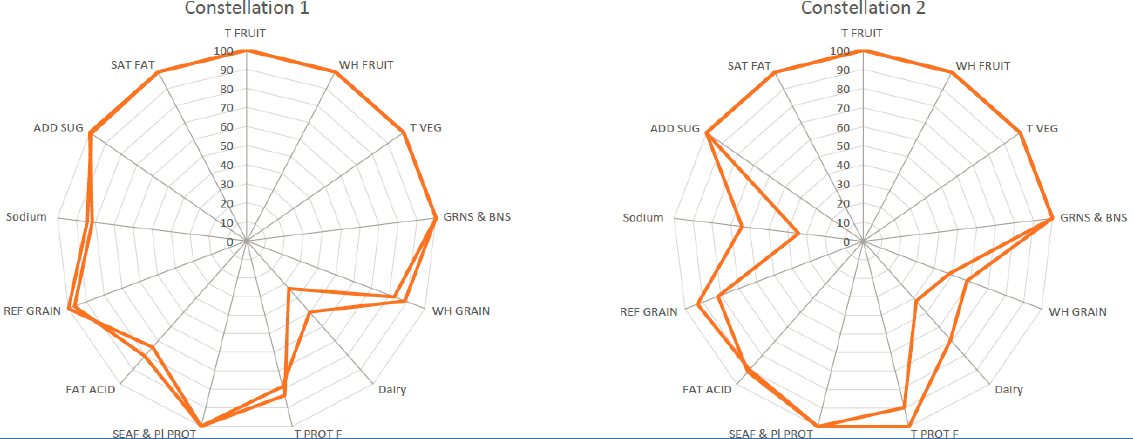

Liese’s third example explored how dietary quality indices can shed light on multidimensionality in dietary patterns. A multivariable analysis of all Mediterranean diet index components sought to identify which individual components predicted mortality and found that only olive oil and alcohol were predictive (Buckland et al., 2011). To increase intake of one dietary component while holding the others constant and controlling for calories, she explained that the change would have to be for a food not already considered in the analysis. Liese also referenced her group’s efforts to identify commonalities and differences in dietary patterns among individuals with very high-quality diets who meet the HEI-2015 recommendations (i.e., their HEI-2015 score falls into the top fifth of the distribution). Using a shape analysis technique, they generated constellations underlying HEI-2015 data and discovered distinct differences between constellations that represented high-quality diets (see Figure 5-2).

Liese shifted to speak to her presentation’s second theme—integrating measurement error into study design and analysis. She reminded attendees that dietary intakes estimated from self-report instruments often have substantial error owing to factors such as day-to-day dietary variation, reliance on memory, and biases such as social desirability (Freedman et al., 2011). Applying statistical methods to correct for random measurement error can lead to a substantial difference in outcomes, she explained, describing an example in which regression calibration was used to assess the association of sugar-sweetened beverage intake and lipid levels in youth with diabetes

NOTE: Add sug = added sugars; fat acid = fatty acids; grns & bns = greens and beans; ref grain = refined grains; sat fat = saturated fats; seaf & pl prot = seafood and plant proteins; t fruit = total fruits; t prot f = total protein foods; t veg = total vegetables; wh fruit = whole fruits; wh grain = whole grains.

SOURCE: Presented by Angela Liese, May 24, 2021.

(Liese et al., 2015). This technique was possible, she elaborated, because a subsample (n = 166) of the broader study cohort completed a second dietary assessment instrument (one to three 24-hour recalls) in addition to the study’s main instrument (an FFQ). Without adjusting for measurement error in intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, the model estimated minimal (not clinically meaningful) differences in lipid levels when consuming 0.07 servings/day or 0.5 servings/day of sugar-sweetened beverages. After applying the regression calibration, the model estimated more substantial (and clinically meaningful) differences in lipid levels between those two intake levels which is to be expected when using this diattenuation method to counter the effects of random error (though this method does not restore power). Liese recommended more widespread application of regression calibration methods, suggesting that it will result in finding stronger associations in research that examines diet–disease relationships.

To conclude her remarks, Liese said that joint consideration of multiple nutrients or food groups or combinations thereof is underused in nutritional epidemiology. Increased focus on the multidimensionality of diet and innovative approaches to its quantification is a promising area of research, as is the application of statistical methods such as regression calibration to correct for measurement error in observational epidemiologic studies. Lastly, she asserted that the widespread integration of such methods into the design and the analysis of dietary assessment studies is critical for advancing the field.

Q & A SESSION

Following their presentations, the five speakers answered questions from workshop series planning committee members and sponsors. The topics covered were motivating participants to complete dietary assessments, the burdens and benefits of EMA, multidimensionality in dietary research, open-source data sharing, and the challenges associated with dietary supplement intake data.

Motivating Participants to Complete Dietary Assessments

Anna Maria Siega-Riz, dean and professor in the School of Public Health and Health Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, asked the speakers how to motivate participants to complete dietary assessments and wondered about gamification as a strategy. Pérez-Rodrigo was aware of a few initiatives to introduce gaming elements as a strategy to engage children while they complete web-based, 24-hour recalls. In her own experience, she has conducted dietary assessment research in school settings where elements of competition and a food preparation contest were involved.

Burdens and Benefits of EMA

Dana Dabelea, professor of epidemiology and pediatrics and director of the Lifecourse Epidemiology of Adiposity and Diabetes Center at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, asked Loth to elaborate on the researcher and respondent burdens associated with EMA. As a follow-up, Dabelea asked what specific advantages could be gained by using EMA to complement another dietary intake method. Loth clarified that her research using EMA to collect children’s dietary intake has asked their parents to complete the EMA on behalf of the child. She reported that in her experience, most users—including low-income families and families from diverse backgrounds—have indicated that they are willing to complete the EMA and that they perceived the burden to be low. Parents routinely engage with their phones throughout the day, Loth added, but they wanted to be able to use their own phone and not have to carry an additional device to complete the EMA. In response to user feedback about how to improve the ease of using EMA, Loth said that her team implemented a “snooze button feature” that parents could click if they were too busy to complete a prompt when it arrived but wanted to be reminded to complete it a few minutes later.

In response to Herring’s question about the duration of participant interaction with EMA prompts, Loth responded that best practices are to keep each assessment no longer than 2 to 3 minutes. This obliges researchers to zero in on the specific information to be collected, she added, and to display the questions in a way that is easy for participants to answer. For example, she said that selecting options from a series of check boxes or sliding a bar within a single screen is an easy way for users to submit responses. Designing an interface that reduces participant burden is related to the technological aspect of developing EMA tools, she pointed out, and commented that her department at the University of Minnesota employs a computer programmer to help with these aspects of research studies. If onsite help is unavailable, Loth said that researchers can purchase apps or pay a fee to have an app’s developers help with the EMA setup.

Returning to Dabelea’s question about how EMA can complement other dietary intake methods such as 24-hour recalls and perhaps reduce the bias associated with that method, Loth responded that EMA can provide contextual information for the eating occasions reported in a 24-hour recall. This information can lead to insights about eating behaviors, she indicated, such as whether people eat differently in different settings, how mood affects eating habits, and how an individual engages with food. Loth acknowledged that this kind of contextual information addresses different questions than those underlying a 24-hour dietary recall (i.e., usual intakes of energy and nutrients in most cases), but she suggested that EMA could

also help reduce the retrospective recall bias associated with this method. Specifically, she proposed that EMA prompts could help capture eating occasions that people are more likely to forget, such as foods and beverages consumed while “on the go” or engaged in other activities. These EMA responses could supplement a 24-hour recall, she suggested, by alerting administrators to probe respondents about eating occasions that might otherwise go unreported.

Multidimensionality in Dietary Research

Responding to Dabelea’s request for an example of a research question that could be addressed with the multidimensionality framework, Liese suggested a question related to the translation of hypothetical population-level dietary intake guidelines. For instance, the guidelines may suggest a largely plant-based diet and be supported by research indicating the positive health effects of such a diet. But if a question comes up about the effects of integrating regular red meat consumption into an otherwise plant-based diet, she said in theory, such a question falls squarely into the realm of multidimensionality.

Open-Source Data Sharing

Siega-Riz asked Catellier for suggestions to promote open-source data sharing across different databases in order to establish more protocols for data harmonization. Consortiums have formed around the goal of standardizing data collection methods, Catellier mentioned, and such consortiums have established common methods for collecting data that can be combined on a central platform usable by the scientific community. It has been challenging to collect all of the ECHO cohorts’ data on one platform, she admitted, and shared her belief that it would be beneficial to stakeholders to coalesce around the best way to collect intake data, particularly for supplement use. With regard to data harmonization, she referenced an effort within the ECHO study to provide guidance for how to crosswalk source data on various dietary measures that flow into diet quality indices such as the Healthy Eating Index.

In response to a question from Herring about data repositories, Catellier was not aware of large repositories for dietary data, but shared that the data she previously referenced will be publicly available in 2022. Researchers invest substantial resources into data collection, she pointed out, which she suggested warrants granting them a reasonable amount of time to do their own analyses before turning over the data to a public database.

Challenges Associated with Dietary Supplement Intake Data

Catellier responded to a comment about the challenge of harmonizing FFQ data on dietary supplement use, suggesting that the difficulty stems from variation in the supplements included and in the level of detail about their nutrient composition. She maintained that this area is ripe for standardization across the various FFQ instruments in use.

In response to a question about how to address multidimensionality in the context of multi-dietary supplements, Liese affirmed that she recognized the complexity of this issue despite not having direct experience implementing it in her own research. It is difficult to quantify supplements properly, she said, let alone integrate them into an approach that explores whether the source of a nutrient changes its effects on health. Nonetheless, Liese thought this could potentially be accomplished by conceptualizing the dietary supplement as another layer of information to include in the analysis.

FINAL WORKSHOP PANEL DISCUSSION: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES TO STRENGTHEN DIETARY INTAKE DATA FROM PREGNANT WOMEN AND CHILDREN

The final session in the fourth workshop concluded the workshop series with a panel discussion on the challenges and opportunities to strengthen dietary intake data from pregnant women and children. The discussion featured nine panelists, consisting of eight speakers from the workshops in the workshop series as well as a new participant, Roberta De Vito, assistant professor in the Department of Biostatistics and at the Data Science Initiative at Brown University. Discussion topics included combining assessment methods and analyzing results, engaging young children as informants, plate waste, and the next steps for advancing dietary assessment research.

Combining Assessment Methods and Analyzing Results

Siega-Riz referred to the proliferation of apps for use during pregnancy that take a crowdsourcing approach to dietary assessment, and asked the panelists for their thoughts on partnering with app companies to leverage that expertise in technology and user engagement. She suggested that such partnerships might be an opportunity for researchers to combine dietary intake data from an app with data from 24-hour recalls, thereby enhancing the dietary assessment component of their research. Boushey concurred with the potential value of combining assessment methods to balance their strengths and limitations.

Herring asked panelists to comment on statistical or other techniques used in other disciplines to combine data from different sources. De Vito said that some attempts to combine nutrition data simply stack the data in one large, consolidated dataset and perform a factor analysis to find common characteristics across populations. Another approach, she proposed, is to perform separate factor analyses for each individual dataset to capture the differences. She referenced her group’s current effort to identify commonalities in data across multiple platforms but also called for a method to capture heterogeneity across platforms.

Daniela Sotres-Alvarez, associate professor in the Department of Biostatistics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, agreed that combining methods is imperative but pointed out that simply stacking and combining them leads to combining different sources of measurement error. As an alternative, she advocated for fitting joint models and making such models readily available for others to use. This is one of the advantages of the National Cancer Institute method for estimating usual intake from multiple data sources, she pointed out, which has macros that enable people to easily incorporate the method into their own work. Catellier agreed with the value of making data platforms more user-friendly and promoted moving toward a protocol that calls for multiple methods of data collection on a subsample of participants. It does not have to be a lot of data, she clarified, but repeated measurements across different studies would allow statisticians to fit more specific models.

Dabelea asked if groups of studies such as ECHO are available as a source of dietary intake data for researchers to use in developing the kinds of models that Catellier and Sotres-Alvarez suggested. That would prevent future studies from having to conduct dietary assessment via multiple methods in order to correct for measurement error, she suggested; instead, they could use a more simple or even self-reported method for dietary assessment and apply the model to correct for measurement error and address bias. According to Sotres-Alvarez, technological advances such as cloud-based platforms that can load data securely are helping move the field in that direction. As data become available from different sources and are added to central repositories, she suggested that it will be important to make researchers aware of its readiness for use. Catellier called for data repositories to specify a common data model so cohorts contributing data can provide them in a standardized format and specify the metadata to include.

Engaging Young Children as Informants

Siega-Riz referenced Boushey’s presentation in asking if researchers could increasingly attempt to engage younger children in image-based methods of dietary assessment. Children’s desire to take photos reflects their

mimicking of the people around them, Boushey pointed out, and expressed her support for “tapping into children as much as possible.” She qualified her statement by drawing the line at 2 years of age, noting that her group’s experience with 2-year-old children found them to be highly distractable and unable to keep track of the mobile photo-taking device. Although she indicated that slightly older children (e.g., 3 years of age) are capable of taking food images, Boushey acknowledged that they still need occasional parent reminders, which she suggested warrants engaging the whole family. Sotres-Alvarez wondered about the accuracy of before-and-after food images captured by children, maintaining that these objective images are still self-reported. The difference in the before-and-after food images may not necessarily translate to the exact amount the child consumed, she inferred, giving the hypothetical example of a child taking a before image and then throwing away some of the food or giving it to a friend before taking the after image.

Loth submitted that a prevailing belief has been that children cannot serve as informants of their own dietary intakes, particularly for eating occasions that do not occur in their parents’ presence (and thus cannot be supplemented with data from parents’ proxy reports). She suggested that using children as the sole reporters of intake data—albeit with some error—for these eating occasions is better than not having data at all.

Susan L. Johnson, professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and a speaker in the workshop series’ first workshop, asked how to ensure that child-collected images—particularly those captured with passive technologies—do not include sensitive content. Baranowski responded that in his work with this method, the images are encrypted immediately upon capture and de-identified after transmission to a central storage location. This means that anyone viewing the images cannot tell who is doing what, he explained, and added that everyone in the study subject’s family consents to the image-taking process. The camera also has an off button, he said, that can be engaged by the child at any time. About 30 children have participated in his research using passive technologies to collect images, he noted, each of whom captured images for 2 days.

Plate Waste

From a sustainability perspective, Herring asked Pérez-Rodrigo if the quality of dietary intake data collected for surveillance purposes is adequate to inform estimates of plate waste. Pérez-Rodrigo noted that most sustainability research has examined greenhouse gas emissions and water use, for example, but acknowledged that other dimensions of food sustainability (i.e., plate waste) have scarcely been addressed. Before-and-after photos of eating occasions could be used to calculate plate waste in a variety of

populations, she confirmed, but cautioned that if calculations were based on written intake data alone (not photos), misreporting could introduce errors into those calculations. For example, she noted that parents sometimes report children’s intakes as the food portion served rather than the portion consumed.

Advancing Dietary Assessment Research

Siega-Riz asked panelists to summarize their suggestions for advancing dietary assessment research. Baranowski urged creation of multidisciplinary teams (including diet researchers, engineers, and data scientists) and investment in technological approaches that could collect “virtually error-free” data. Acknowledging that this is a long-term, “25-year” perspective, he supported his view by contending that current self-report methods are flawed and require substantial statistical effort postcollection in order to mitigate errors. He asserted that in 25 years, it may be considered unacceptable to use self-reported methods for dietary assessment if more accurate passive or objective technological approaches are widely feasible. On that note, he mentioned that improvements are expected in artificial intelligence algorithms that classify passively collected images, meaning that only those most relevant to the study would be retained.

From the perspective of big data, De Vito said that because missing data is a concern when assessing dietary intakes, she proposed more routine collection of intake data using multiple methods and data integration. She added that when building strong models for integrating data coming from multiple methods, error can be removed by using, for example, techniques used in machine learning such as sparse principal component analyses.

Herring raised the topic of biospecimens and asked whether biomarkers or microbiome samples, for example, could be used to help correct for error and bias in dietary intake reports. Similarly, Siega-Riz wondered about the possibility to triangulate data from self-report, biomarkers, and microbiome measures. Sotres-Alvarez reminded attendees that only a handful of nutrient biomarkers are currently available, and Liese cautioned that integrating data from self-reports and biomarkers is to be done carefully. The use of biomarkers encompasses the pathways of foods postingestion, she explained, which brings many more factors into play. She further elaborated that the level of a nutrient measured inside the body is a different measure than the self-reported amount of a nutrient consumed.

Liese also proposed that greater openness to integrating data collected from multiple informants and methods would be “truly revolutionary” for the field of dietary assessment. Because no perfect instrument exists, she maintained, integrating measures from multiple good instruments and applying statistical approaches to correct for error would lead to greater

advancement than the use of single instruments perceived to be superior. With respect to integrating greater amounts of data, Herring said that it is challenging because although more data can provide more precise estimates, it could also lead to more inaccurate results if people are misreporting.

Anne-Sophie Morisset, researcher at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire at the Québec–Laval University Research Center and professor at the School of Nutrition at Laval University, suggested that while dietary assessment methods are being improved, researchers can use results from the methods available to make intervention decisions. As an example, she said that if intake data indicate that fruit and vegetable intake decreased from beginning to end of pregnancy, then addressing that decrease is an area for intervention. Even if researchers do not have all of the details about the specifics about the decrease, she elaborated, aiming to improve overall fruit and vegetable intake can help women have a healthier pregnancy (Murphy et al., 2014; USDA and HHS, 2020). She suggested assessing dietary intake during each trimester of pregnancy, given that trimester-specific recommendations exist for some dietary components.

HIGHLIGHTS4

Cheryl Anderson, professor and dean of the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science at the University of California, San Diego, and member of the workshop series planning committee, summarized a selection of key points from the workshop series’ four workshops before she adjourned the series. She grouped these points into three categories: unique features of different life stages of interest, considerations for choosing assessment methods and designing tools, and considerations for analyzing and sharing data.

Unique Features of Pregnancy, Early Childhood, and Later Childhood

- Pregnancy is a vulnerable time period during which women are willing to make dietary changes.

- 2 to 5 years of age are a period during which food preferences that affect health across the life course are established.

- 6 to 11 years of age are marked by heterogeneity in capacity to recall dietary intake information owing to gradual age-related development in cognitive abilities.

___________________

4 These points were made by the individual workshop participant identified above. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Considerations for Choosing Assessment Methods and Designing Tools

- The ultimate goal is to determine the bioavailable amounts of nutrients during these three different life stages. To more fully understand nutrient status, combining multiple dietary assessment methods and instruments (including those measuring dietary supplements) with measures of metabolic status is an important strategy.

- Because error or “noise” is inherent to any data collection effort, researchers are encouraged to consider trade-offs in the advantages and disadvantages of candidate methods. The optimal method and tool (or complementary combinations thereof) for a particular study depend on the research question and factors such as sample size, characteristics of the study population, desired level of accuracy in the reported data, staff and financial resources, and burden to staff and respondents.

- Rapid changes in new technologies may perhaps, eventually, make self-report methods unacceptable.

- Forming multidisciplinary teams that include experts such as engineers, data scientists, anthropologists, and other disciplines can help accelerate improvements in methods and tools, particularly those based on emerging technologies.

- The constantly evolving food, beverage, and dietary supplement market landscape necessitates flexibility to improve food databases used in dietary assessment research and to provide updated tools to improve reporting accuracy.

- Collecting data on children’s dietary intakes from multiple informants or proxy informants is helpful but comes with its own set of challenges related to measurement error and missing data.

- For both child-reported and caregiver-reported data on dietary intakes, examples of challenges include issues related to unobserved intake, food waste, forgotten foods, intrusion foods, portion size determination, and social desirability bias.

- Adopting a multidimensionality framework is a promising approach to address research questions about (1) the interaction of different nutrients or foods in their effects on health outcomes, (2) the effect of different food sources of a nutrient on the nutrient’s health effects, and (3) the use of diet quality indices to provide insights about multidimensionality in dietary patterns.

Considerations for Analyzing and Sharing Data

- Harmonizing intake from dietary supplements remains a challenge given the level of variability in these products’ composition.

- It will be beneficial to develop platforms that consolidate and integrate open-source, commonly collected, standardized data on repeated intake measures for the scientific community to use to answer questions across databases about dietary intakes of pregnant women and children. Such data repositories would also ideally include metadata for the dietary intake measures and could also be used to fit sophisticated analytic models.