Proceedings of a Workshop

WORKSHOP OVERVIEW1

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), enacted on March 23, 2010, has increased the number of people covered by health insurance. The ACA is the most significant change in health care policy in the United States in a half century, said Kathleen Sebelius, who oversaw the implementation of the ACA as secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) at the time. Sebelius noted that the main goals of the ACA were to expand access to affordable, high-quality health insurance; increase consumer insurance protections; improve the quality of health care; strengthen prevention and wellness; and support innovative care delivery models that reduce costs and/or improve quality.2

On March 1–2, 2021, the National Cancer Policy Forum of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened a 1.5-day virtual public workshop to examine the impact of the ACA on cancer prevention and care. Workshop participants discussed the available evidence to assess (1) the

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and this Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of the individual presenters and participants, and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

2 See https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/the-affordable-care-act-brief-summary.aspx (accessed May 19, 2021).

effects of the ACA on people at risk for or living with cancer and (2) lessons learned from the ACA’s design and implementation, looking to inform future efforts to improve and support the delivery of high-quality and equitable cancer care across the care continuum. Additionally, participants discussed new models of payment for cancer care delivery as well as the impact of new organizational infrastructures made possible by the ACA, including the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), to test innovative payment and delivery system models, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), to help patients and health care consumers make better informed health care choices.

A number of workshop speakers—including Sherry Glied, dean of the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service at New York University; Katie Keith, associate research professor at Georgetown University; and Nicole Huberfeld, professor of law at the Boston University School of Law and School of Public Health—spoke about patient protections provided by the ACA (see Box 1) and their implications for the care of people diagnosed with cancer (see Box 2).

In 2010 nearly 17 percent of the U.S. population was uninsured and could not obtain insurance coverage, said Huberfeld (Gluck and Huberfeld, 2018; Villegas and Galewitz, 2010). She said that the ACA was intended

to create a system with options for public and private insurance coverage that together would create near-universal coverage for U.S. citizens. The ACA increased the number of insured people by expanding eligibility for Medicaid—a health coverage program jointly funded by the federal government and state governments—and by establishing health insurance marketplaces. Health insurance marketplaces are platforms where people without employer-sponsored health insurance are able to compare different community-rated individual insurance plans and select the one that is best for their needs, based on cost and coverage options. The marketplaces are the centerpiece of the ACA, said Glied and Keith, who explained that the marketplaces include multiple interlocking reforms that work together to provide

protections and benefits for people diagnosed with cancer. The ACA also eliminates coverage restrictions for preexisting conditions and lifetime caps in coverage, facilitates access to clinical trials, allows children to remain on their parents’ insurance plans until they are 26, and improves access to preventive health care services with limited or no cost-sharing requirements.

These changes have altered the landscape of care delivery across the cancer care continuum—from early detection, diagnosis, and treatment through survivorship—but there are still many individuals who remain uninsured or underinsured, and questions remain as to whether new insurance mechanisms have resulted in improved access to high-quality cancer care or improvements in outcomes for patients with cancer. This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the issues that were discussed at the workshop and highlights suggestions from individual participants to build on the impact of the ACA on cancer prevention and care; these are included throughout the proceedings and summarized in Box 3. Appendix A includes the Statement of Task for the workshop. The workshop agenda is provided in Appendix B. Speaker presentations and the workshop webcast have been archived online.3

CONSUMER PROTECTIONS IN THE ACA

Provisions of the ACA provided important consumer protections, such as coverage for preexisting conditions, coverage of essential health benefits, limiting patients’ out-of-pocket health care expenses, and ensuring network adequacy.

Coverage for Preexisting Conditions

Glied and Keith explained that protection of people with preexisting conditions is one of the most popular components of the ACA. This protection dictates that an insurance company cannot consider an individual’s or family’s medical history in determining whether to provide insurance coverage, or when setting prices for premiums, determining benefits, or deciding whether to pay for services. This provision has extended access to coverage for cancer patients and survivors. Glied stated that prior to the ACA, a 48-year-old breast cancer survivor, for example, had a 43 percent chance of being denied coverage because of her preexisting condition (Pollitz and Levitt, 2002).

___________________

3 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/03-01-2021/the-impact-of-the-affordablecare-act-on-cancer-prevention-and-cancer-care-a-virtual-workshop-part-1#sl-three-columns-ae50cfbb-994c-41f7-99b7-71f6551ce37d (accessed September 7, 2021).

Benefit Design

Glied and Keith described the importance of coverage for the 10 essential health benefits.4 Glied explained that several of the essential health benefit categories—including prescription drugs; rehabilitative services, including physical therapy; and mental health care services, which are covered at parity with other health conditions—are important for cancer survivors. Keith pointed out that coverage of preventive services without cost sharing may play a key role in expanding access to preventive care, especially for people with

___________________

4 For more information on the 10 essential health benefits, see https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/what-marketplace-plans-cover (accessed October 13, 2021).

low and middle incomes and for communities of color. All marketplace plans have a prescription drug formulary, which is a list of generic and brand name prescription drugs covered by the plan. Glied pointed out that while all plans must cover specialty cancer drugs, the approach varies by state, and specialty cancer drugs are typically on the highest tier for patient cost sharing. Also, while the formulary is supposed to be transparent regarding the tier each drug is on, it is not always accurate, and people may not know all the medications they will need over the next year when selecting a plan.

Cost

The ACA has several provisions aimed at making health insurance and health care affordable for patients, including subsidies for purchasing insurance in the marketplace and limits on out-of-pocket expenses. Glied said the subsidies for purchasing health insurance bring the average cost for coverage to about $120 per month for standard coverage for a 40-year-old (McDermott and Cox, 2020). Costs and benefit levels vary across bronze, silver, gold, and platinum marketplace plans. Glied explained that platinum plans have the highest premiums but cost the least to use. Gold plans cover an average of 80 percent of expenses, slightly less than a typical employer-sponsored plan.5 Glied and Keith explained that premium costs remain high despite subsidies, and many low- and middle-income consumers who qualify for subsidies or who have incomes just above the limit to qualify can still find premiums unaffordable. Glied pointed out that for people with incomes below 138 percent FPL, who qualify for Medicaid, and those with incomes between 138–399 percent FPL, the ACA has brought down out-of-pocket costs for cancer care, but some costs remain high. However, the ACA has had less of an impact on bringing costs down for people with incomes of 400 percent FPL and above.

Glied noted that out-of-pocket maximums for individuals enrolled on marketplace plans can be quite high, especially among those with serious illness: “If you need a lot of care—if you are at the 99th percentile of that spending distribution—you may have to pay as much as $18,000 a year in combination for your premium and your out-of-pocket expenditures” (see also the section on Cost Sharing).

Network Adequacy

Network adequacy, another key dimension of coverage that Glied and Keith described, is based on how many care providers—including specialists—are in the network, where they are located, and how easily patients can access them. Glied noted that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) established quantitative network adequacy standards during the Obama administration, but they were rolled back during the Trump administration. Instead, states were given the authority to determine whether networks in qualified health plans in the marketplaces were adequate. Glied pointed out that while some states have strong quantitative network adequacy standards, others do not. Keith added that networks may vary by state, by insurer, and

___________________

5 See https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/how-aca-marketplace-premiums-are-changing-by-county-in-2021 (accessed May 27, 2021).

by plan, and that some networks exclude care provided at National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated cancer centers.

Enrollment

Glied stated that 8 million people enrolled in marketplace plans when the plans were first established in 2014, and coverage peaked in 2016 at about 13 million people (Tolbert et al., 2020). Enrollment has declined since then due to a variety of factors.

MEDICAID EXPANSION AND NON-EXPANSION

Several workshop speakers discussed the state of Medicaid coverage before passage of the ACA, the current status, and paths to Medicaid expansion.

The Status of Medicaid Coverage Before the ACA

Prior to the ACA, there was significant geographic variation in Medicaid income eligibility limits, said Robin Yabroff, scientific vice president of Health Services Research at the American Cancer Society. In approximately 12 states, parents had to earn less than 50 percent FPL to be eligible for Medicaid, while in most other states, the eligibility limit was between 51–137 percent FPL. Yabroff noted that across all states, the median income limit for Medicaid eligibility prior to the ACA, was 64 percent FPL, equal to about $12,000 for a family of three in 2010. Yabroff said one analysis reported that in 2010, about 23 million U.S. adults with low income were uninsured, accounting for nearly 10 percent of the population (KFF, 2021). This percentage varied significantly from state to state. There were also significant geographic disparities in cancer mortality prior to the ACA, Yabroff added. She stressed that, for example, the cancer mortality rate for men from 2002 through 2011 was nearly twice as high in the southeastern U.S. as in the Southwest and Midwest.

Current Status and Paths to Medicaid Expansion

The ACA called on states to expand Medicaid eligibility to adults with incomes up to 138 percent FPL. Originally a requirement, a Supreme Court ruling in 2012 effectively made Medicaid expansion an option.6 To date, almost three-quarters of states have opted to expand.

___________________

6 See https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/overview-of-the-affordable-care-act-and-medicaid (accessed October 13, 2021).

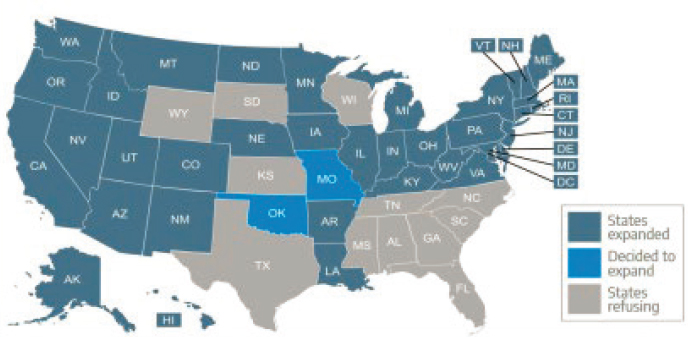

As shown in Figure 1, as of March 1, 2021, 36 states and the District of Columbia have implemented Medicaid expansion. Two additional states (Missouri and Oklahoma) have voted to expand through ballot initiatives but have not implemented their expansion. The 12 remaining states have not expanded Medicaid. Trish Riley, executive director of the National Academy for State Health Policy, stated that there have been 19 million new Medicaid enrollees since the passage of the ACA, including 15 million in expansion states and 4–5 million in non-expansion states (Guth et al., 2021). Riley said that about 20 percent of total Medicaid enrollment is the expansion population, but they represent only 16 percent of Medicaid spending.

Riley said that states have followed various paths to Medicaid expansion, including state legislative actions, citizen referenda, and Section 1115 demonstration projects (see Box 4). She explained that about half of the states have an accountable care organization (ACO) structure requiring health care providers to meet cost and quality standards and then share savings, while ten states use payment models based on episodes of care and focused on meeting cost and quality goals. Only one state, Ohio, includes breast cancer surgery as an episode of care, she added. The ACOs are groups of health care providers, including hospitals that coordinate care for the patient to avoid duplication of services. If an ACO provides quality care and saves money, then the ACO will get a portion of the funds it has saved the state Medicaid program.

Riley said that, given the breadth of Medicaid responsibilities, agencies do not generally use disease-specific approaches. However, all state Medicaid

SOURCES: Huberfeld presentation, March 1, 2021; see https://www.kff.org/nvolvin/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map (accessed September 14, 2021).

programs target primary care, including prevention, screening, and management of chronic illness. The ACA created health homes,7 which are another mechanism like ACOs to coordinate care, but few states have health homes for people with cancer, Riley noted. Exceptions include California, which has an initiative involving advanced care planning, pain management, mental health, and care coordination; and Washington State, which includes cancer in its complex care model. She pointed out that there is limited coverage for palliative care due to definitional challenges and some state budget constraints. She suggested that states could recognize cancer as a chronic illness and better incorporate cancer care into value-based payment models to incentivize high-quality cancer care. States could also consider lessons learned from the CMMI Oncology Care Model (OCM) episode of care payments and provide increased support for palliative care.

THE IMPACT OF THE ACA ON CANCER PREVENTION AND CARE

Workshop speakers discussed how the ACA has increased utilization of cancer preventive services and has helped to decrease inequities in coverage of cancer screening and care. Speakers also discussed remaining barriers and shared their ideas on potential strategies to provide equitable, high-quality cancer care.

Utilization of Cancer Screening, Prevention, and Treatment Services

Eliot Fishman, senior director of policy at Families USA, emphasized that insurance is the primary mechanism that allows people to access health care, and a lack of health insurance is a significant risk factor for cancer morbidity and mortality. This is because the cost of care for people without insurance impedes access to preventive services and the ability to seek care when symptoms arise, he added.

Multiple components of the ACA either directly or indirectly affect the provision of cancer preventive services. For example, the dependent coverage mandate under the ACA is associated with increased human papillomavirus vaccination and a decline in late-stage cervical cancer diagnoses among young adults (Moss et al., 2020; Sabik and Adunlin, 2017; Zhao et al., 2020), said Lindsay Sabik, associate professor and vice chair for research at the University of Pittsburgh. Sabik also explained that the ACA Medicaid expansion allowed

___________________

7 For information about health homes, see https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/longterm-services-supports/health-homes/index.html (accessed September 24, 2021).

many adults with low income (up to 138 percent FPL) who were previously uninsured to gain insurance coverage (Han et al., 2020; Jemal et al., 2017). Sabik said the ACA also requires coverage of cancer preventive services without any patient cost sharing, such as copayments, coinsurance, or deductibles, if those services have a grade of “A” or “B” from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). The ACA also requires coverage for annual screening mammography,8 although the USPSTF currently recommends biennial screening.9

To illustrate the importance of the ACA requirements for coverage of preventive services, Sabik shared the story of a woman from Indiana who was uninsured prior to the ACA and enrolled in the state’s expanded Medicaid program. After gaining Medicaid coverage, she saw a primary care provider, who referred her for a mammogram. The woman was subsequently diagnosed with and treated for stage 1 breast cancer. Without insurance to cover the costs of her screening and treatment, Sabik pointed out, the cancer would likely have progressed. Freddie White-Johnson, program director of the Mississippi Network for Cancer Control and Prevention at the University of Southern Mississippi, and founder and director of the Fannie Lou Hamer Foundation, also pointed out that many people who lack insurance in states that did not expand Medicaid, including Mississippi, do not get recommended cancer screenings because of the costs of the tests and subsequent treatment. As a result, she said, people are dying prematurely from cancer that is diagnosed at a late stage.

Kosali Simon, associate vice provost for health sciences at Indiana University, noted that most studies find an increase in at least one type of cancer screening among insured patients post-ACA, although findings vary by screening type, with evidence of increases in colorectal cancer screening being the most consistent (Huguet et al., 2019; Moss et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). Sabik pointed out that mixed findings across cancer types may reflect differences in safety net programs targeting screening for specific cancers. She added that the largest increases in screening rates are in states that expanded Medicaid early on, suggesting there may be lagged effects (Huguet et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2021; Simon et al., 2017).

But Sabik noted that although cancer screenings increased as a result of the ACA, leading to earlier detection of cancers, questions remain about the extent to which the increases in screening have benefited populations that have long experienced barriers to care, and whether patient outcomes are improving due to earlier detection of cancers. Simon said that although research on the

___________________

8 See https://www.hrsa.gov/womens-guidelines/index.html (accessed September 30, 2021).

9 See https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/breast-cancer-screening (accessed September 30, 2021).

impact of Medicaid expansion on cancer treatment and health outcomes is more limited, there is evidence that increasing access to cancer screenings leads to identification of tumors at early stages so treatment begins earlier, which can lead to improved patient outcomes and, in some cases, less impact on patient finances (Lin et al., 2021; Sabik and Adunlin, 2017). She said improvements were largest in the earlier implementation period (Adamson et al., 2019; Chu et al., 2021; Eguia et al., 2018; Jemal et al., 2017; Soni et al., 2018), so it is unclear if this trend will continue or if it was due to pent-up demand immediately following expansion.

Simon noted that prior to the pandemic, the availability of administrative claims data often lagged, making it difficult to assess utilization changes in a timely manner. However, the COVID-19 research database10 has provided data from large health care organizations (with more than 40 million patients) to researchers on a very rapid basis, enabling more timely analyses about how the pandemic has affected utilization of different health care services, including cancer screening and treatment.

Decreasing Inequities in Coverage of Cancer Screening and Surveillance

Fola May, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, described several components of the ACA that provide opportunities to reduce inequities in access to cancer screenings and other care services. She said that increasing access to health insurance through Medicaid expansion has had a positive effect on health outcomes. The ACA includes several reforms intended to reduce health inequities, including the elimination of many cost barriers to preventive services, requirements for insurance coverage of preventive services, use of care models with a patient-centered medical home, and increased funding for federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), May added. She said that the ACA has improved health insurance coverage for low-income and racial and ethnic minority populations. May added that uninsurance rates among individuals with low incomes declined the most in states that adopted Medicaid expansion (Mahal et al., 2020). May and Huberfeld noted that Medicaid expansion has reduced socioeconomic inequities in health care access because it has provided a disproportionate increase in coverage for Black, non-Hispanic and Hispanic populations (Chaudry et al., 2019).

May noted that research on the impact of the ACA on disparities in utilization of cancer screening services is limited. Screening rates improved post-ACA

___________________

10 See https://covid19researchdatabase.org (accessed October 4, 2021).

for all populations, and there was little to no reduction in disparities (Fedewa et al., 2019; Hendryx and Luo, 2018; Huguet et al., 2019). However, May pointed out that the ACA reduced rural–urban inequities in colorectal cancer screening by 40 percent between 2009 and 2012 (Haakenstad et al., 2019).

May emphasized that although screening rates for cervical and colorectal cancer increased across all race and ethnic groups in both expansion and non-expansion states, the rates remain suboptimal for patients who are socioeconomically disadvantaged. She also noted that the difference between current rates of colorectal cancer screening and the goal of the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable11—screening 80 percent of eligible people in every community—is wider for racial/ethnic minority populations, suggesting that substantial investments beyond the ACA are needed to reach screening goals.

Addressing the Remaining Barriers to Coverage of Preventive Services

Stacey A. Fedewa, scientific director of screening and risk factors research at the American Cancer Society, May, and Sabik described several remaining barriers to coverage of preventive services across insurance types, including cost-sharing loopholes in private plans and opportunities to expand and strengthen Medicaid policies. Fedewa said that one cost-sharing loophole is that “grandfathered plans,” which are private plans that existed before the enactment of the ACA, do not have to comply with ACA cost-sharing requirements. Fedewa noted that in 2018, 20 percent of employers surveyed said that they offered grandfathered plans, and 16 percent of their workers were enrolled in one.12 Fedewa, May, and Sabik agreed that there is a need for more data on grandfathered plans to inform policy. Sabik pointed out that there are many differences and inconsistencies in benefits and cost sharing across types of insurance, states, and specific plans, including grandfathered plans.

Another cost-sharing loophole Fedewa described is for follow-up after an abnormal result on a screening test. For example, if a person has a positive result on a stool test for colorectal cancer, they may incur costs for the recommended follow-up colonoscopy, she said. May added that the follow-up rate after a positive stool test is suboptimal, especially in low-income populations. In one community health center, she said that only 18 percent of individuals who received an abnormal stool test completed a colonoscopy (Bharti et al., 2019). Similarly, if a woman has an abnormal mammogram or has dense tissue identified on her mammogram, she may face out-of-pocket expenses for additional recommended testing. While some states have addressed cost

___________________

11 See https://nccrt.org (accessed September 23, 2021).

12 See https://www.kff.org/report-section/2018-employer-health-benefits-survey-section-13-grandfathered-health-plans (accessed May 23, 2021).

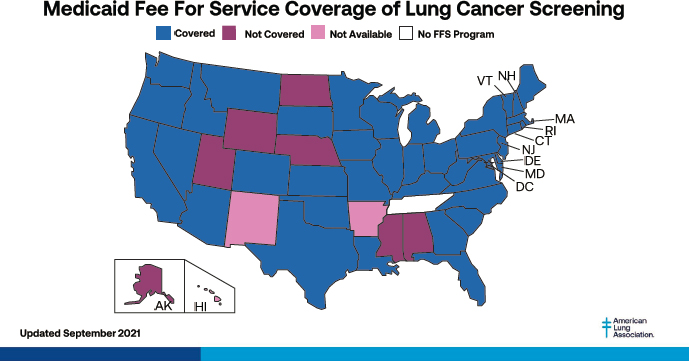

SOURCES: Fedewa presentation, March 1, 2021; https://www.lung.org/lung-healthdiseases/lung-disease-lookup/lung-cancer/saved-by-the-scan/resources/state-lungcancer-screening (accessed September 15, 2021).

sharing for follow-up testing for women with dense breast tissue, there is no federal regulation that addresses this problem (ACR, 2019).

Sabik and Fedewa explained that the ACA requires coverage without cost sharing for cancer screenings for average-risk individuals consistent with the USPSTF guidelines. However, Sabik noted, individuals who are at higher risk may require more frequent screening or additional tests and thus could face out-of-pocket costs that pose barriers to care. Melinda Buntin, professor and chair of health policy at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, suggested that the USPSTF expand its work to further consider the needs of diverse populations. Another gap in coverage of cancer preventive services is that states can decide whether or not to cover cancer screenings under traditional Medicaid. For example, Fedewa noted, current or former smokers, for whom lung cancer screening is recommended, are disproportionately likely to be enrolled in Medicaid, and in 12 states traditional Medicaid may not cover lung cancer screening at all, as shown in Figure 2.

PROTECTIONS FOR ADOLESCENT AND YOUNG ADULT POPULATIONS

Several speakers said that increasing the age limit for dependent coverage to age 26 is an important component of the ACA that has expanded health

care access for adolescents and young adults (AYAs). Other speakers noted that positive spillover effects have been seen. For example, children whose parents were covered by Medicaid after expansion are more likely to be up-to-date on their immunizations, to receive transition care, and to have a reduction in financial adverse effects.

Impact of the ACA on Children and Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer

Several speakers said that the ACA allowance for dependents to remain on their parent’s plan until age 26, as well as Medicaid expansion, has improved insurance coverage for the AYA population, which is defined by NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program13 as those diagnosed with cancer between 15 and 39 years of age (Alvarez et al., 2018; Barnes et al., 2020; Nogueira et al., 2019; Parsons et al., 2016). However, inequities persist, as there has been less improvement in coverage for racial and ethnic minority AYA populations and those in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities (Alvarez et al., 2018: Parsons et al., 2016).

Anne Kirchhoff, associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Utah; Elyse R. Park, professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital; and Shreya Roy, assessment and evaluation research associate at the Oregon Health & Science University, spoke about the impact of the ACA on AYA patients diagnosed with cancer. Kirchhoff noted that almost 90,000 AYA patients are diagnosed with cancer each year in the United States (Miller et al., 2020). She said that this population is often described as “lost in the gap” between pediatric and adult cancer care, and many experience developmental and social effects while dealing with their cancer diagnosis and treatment. Kirchhoff emphasized that AYA patients typically have fewer resources to manage medical costs and less experience with navigating the health care system than older adults with cancer. In the United States, AYA patients are also more likely to be uninsured than older cancer patients, she stressed.

Roy noted that an increase in Medicaid eligibility for parents under the ACA increases the likelihood of their children receiving an annual well-child visit (Gifford et al., 2005; Venkataramani et al., 2017). She said that parents who are insured are better able to navigate the health care system for themselves and their family members. Also, Medicaid expansion has helped to reduce family financial burdens and free up resources for families to access preventive care.

___________________

13 See https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/aya.html (accessed September 9, 2021).

Roy said that there is insurance inadequacy for children and young adults with special health needs and complex medical conditions (CAHMI, 2021). Adolescents and young adults with complex medical conditions (this population includes young adults with a progressive or metastatic malignancy that affects life function) need health care services necessary for transitioning from child to adult health care (White et al., 2018). She explained that transition services help to ensure that children with complex medical conditions have continuity of health care services into adulthood (Roy et al., 2021; White et al., 2018). However, Roy stated that more than three-fourths of young adults with complex medical conditions do not receive transition services, and reimbursement for receipt of transition services by health insurance plans is absent, limited, or inadequate (CAHMI, 2021; Roy et al., 2021). Roy noted that gaps in care, which occur during the transition period, may lead to an increase in hospitalizations (AHRQ, 2013; Sharma et al., 2014). She said one analysis found that adolescents who had an annual preventive care visit were twice as likely to receive transition preparation than those who did not (Roy, 2019). Moreover, Roy said that families of children and young adults with special health care needs often have significant out-of-pocket expenses, because health insurance may not cover all necessary medical and related services (Feldman et al., 2015; Parish et al., 2008). She emphasized that the ACA provisions, such as the elimination of annual or lifetime limits on the total cost of health care services, have helped to address this challenge and help ensure that individuals with preexisting health conditions have continuous coverage (Catalyst Center, 2017).

Park said an analysis from a survey of 698 survivors and 210 siblings from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study14 found that prior to implementation of the ACA, even insured survivors experienced challenges with high deductibles and out-of-pocket costs and with being able to work enough hours to maintain insurance coverage or stay in school. Also, prior to the ACA, uninsured AYA cancer survivors experienced barriers to acquiring health insurance coverage due to preexisting conditions (Park et al., 2012, 2015; Warner et al., 2013). The analysis also found that only 27 percent of survivors reported familiarity with the ACA,15 and only 21 percent of survivors believed the ACA would make it more likely that they would get quality insurance coverage. Compared with their siblings, survivors reported much higher out-of-pocket medical costs and were more likely to borrow money to pay for their medical care, worry about being able to pay for a needed medical procedure, or not fill a prescription. Insured survivors reported spending more on out-of-pocket

___________________

14 See https://ccss.stjude.org (accessed September 9, 2021).

15 Familiarity with the ACA did not differ significantly among cancer survivors and their siblings.

medical expenses than uninsured survivors, implying that uninsured survivors may not have access to all of the care they need. All these factors improved after implementation of the ACA, Park stressed.

Park noted that interventions are needed at the individual, community, and care system level to increase health insurance coverage and access to care for AYA cancer survivors. She suggested patient navigation as an intervention. Park said that patient navigation outcome measures could include perceived knowledge, perceived confidence in overcoming barriers to care, satisfaction with patient navigation services, measures of health insurance literacy, financial distress related to medical costs, and familiarity with ACA policies. She said there are remaining challenges and research gaps on the impact of the ACA on children and AYA patients with cancer. She said some of the gaps include the extent of underinsurance among AYA patients and its impact on access to care, the impact of narrow networks on AYA patient access to care and clinical trials, the lack of coverage and cost of onco-fertility services, lack of reimbursement for patient navigation, and the cost barriers of high-deductible health plans. Kirchhoff reiterated that access to onco-fertility services, in particular, is a challenge because fertility care during cancer treatment can cost tens of thousands of dollars and is often not covered by insurance. Kirchhoff and Park suggested the need for further research on subpopulations of AYA patients with cancer, such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC); lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer; and rural populations.

IMPACT OF ORGANIZATIONS CREATED BY THE ACA ON CANCER RESEARCH AND CARE

The ACA authorized the establishment of CMMI within CMS and PCORI. The activities of these two organizations have implications for cancer care and research.

CMMI

CMMI was designed to create and test innovative payment and service delivery models, including in oncology, that reduce program expenditures while preserving or enhancing quality of care. Lara Strawbridge, director of the Division of Ambulatory Payment Models at CMMI, said that aspects of cancer care CMMI has sought to address include chemotherapy, acute care utilization in the hospital and/or emergency room, end-of-life care, incorporation of value and evidence in drug prescribing, and whole-patient care, such as identifying and treating mental health comorbidities, addressing social determinants of health such as nutrition and transportation concerns, and care coordination.

Strawbridge described CMMI’s two oncology-specific payment models, the Oncology Care Model (OCM) and the Radiation Oncology (RO) Model.

The Oncology Care Model

OCM is a 6-year voluntary pilot that will end in the middle of 2022. Participating oncology practices represent approximately 25 percent of chemotherapy-related care in fee-for-service Medicare. OCM practices are required to perform six fundamental transformation processes aimed at redesigning their care, including provision of patient navigation, care planning, 24/7 access, use of national guidelines, use of data for quality improvement, and use of certified electronic health record (EHR) technology. Strawbridge said that OCM incorporates a two-part payment system to create incentives for participating practices to improve the quality of care and furnish enhanced services for beneficiaries who undergo chemotherapy treatment for a cancer diagnosis. The first is a monthly per-beneficiary payment of $160—called Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services (MEOS) payments—for delivery of enhanced services. The $160 MEOS payment assists participating practices in covering costs associated with effectively managing and coordinating care for oncology patients during episodes of care. The second is the potential for a performance-based payment or recoupment of costs based on whether the practice reduces cost in 6-month episodes of care and performs sufficiently well on a set of quality measures. As a result, oncology care providers may be incentivized to reduce unnecessary health care services to reduce treatment costs below a target, without negatively affecting patient outcomes.

Strawbridge said that OCM is a multipayer model with five commercial payers participating. She explained that this creates consistent incentives and requirements across as many patients as possible to encourage whole-practice transformation. She noted that the model has made adjustments post-implementation to improve cost targets, such as distinguishing between lower- and higher-risk patients with breast, prostate, and bladder cancers, and incorporating staging into risk adjustments.

Strawbridge said that although some health care providers say that the MEOS payments have allowed them to provide additional services not traditionally covered by Medicare, improve care coordination, address financial toxicity, improve communication, and address health-related social needs, such reports are not yet fully supported by evaluation data (see Box 5). She said that CMS has evaluation data available for care episodes ending through mid-2019, covering 5 of the 11 total OCM performance periods. Evaluations have found that there is no impact on hospital-based services, including hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Patients also did not report receiving better care, Strawbridge said. Furthermore, Strawbridge stated that

the overall reduction in episode cost has not been sufficient to overcome the MEOS and performance-based payments (Hassol et al., 2021).

Barbara L. McAneny, chief executive officer of New Mexico Oncology Hematology Consultants, Ltd, explained that from a clinician’s perspective, CMMI alternative payment models are not achieving the overall ACA goals of delivering better care and improving health. She said that another model, the Medicare Shared Savings Program16 with ACOs, led to overall net savings to Medicare of $313 million in 2017, equivalent to only $36 savings per beneficiary in 2017 and $78 in 2018 (Miller, 2018). However, McAneny said that the Community Oncology Medical Home (COME HOME)17 model (supported through a CMMI innovation award) resulted in decreased hospitalizations and better care of patients, and saved CMS about $36 million, equivalent to about $612 in savings per patient. This model was particularly impactful in the last 180 days of life, saving close to $6,000 per patient (Colligan et al., 2017; Dhopeshwarkar et al., 2016). She explained that the COME HOME model focused on improving health outcomes, enhancing patient care experiences, preventing hospitalizations, and reducing costs of care. She added that the model paid practices and nurses to manage patients and intervene early on side effects to support the goal of decreasing hospitalizations and emergency department visits (Waters et al., 2019).

Also, McAneny said that CMS pays hospitals at much higher rates than physicians, and that CMS’s payments for infusion are insufficient. McAneny

___________________

16 See https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram (accessed September 23, 2021).

17 See http://www.comehomeprogram.com (accessed September 9, 2021).

also said that she believes the target prices in OCM were inaccurate and OCM’s one-size-fits-all approach does not work. For example, she said OCM did not account for a significant difference in cost between patients with pancreatic cancer who had small-bowel obstruction symptoms and those who did not. As a result, participating practices could be penalized for factors outside their control.

The Radiation Oncology Model

Strawbridge also described the development of CMMI’s RO Model.18 She said that the model is proposed to start in January 2022 and will last 5 years. The model is intended to move away from fee-for-service and offer predictable, stable payments that do not vary by site of service or volume or type of care during a care episode, in order to support the delivery of high-quality, evidence-based care that will improve outcomes and reduce costs for beneficiaries. Strawbridge said that the RO Model requires the participation of approximately 1,000 physician group practices, freestanding radiation therapy centers, and hospital outpatient departments in randomly selected geographies, representing about 30 percent of care episodes nationally, or about 65,000 beneficiaries in the first year. She said that having a randomly selected, heterogeneous group of participants will ensure that the results are generalizable. However, there will be an option for low-volume entities to opt out on an annual basis, she added.

Strawbridge explained that the RO Model includes 16 cancer types that are most commonly treated with radiation therapy and the most common radiation treatment modalities. She said that the RO Model includes an episode-based approach, with 90-day treatment episodes focused on provision of radiation therapy services. She noted that the RO Model will focus only on radiation therapy services, to reflect the role of the radiation oncologist, and not total care as is the case in OCM. Strawbridge said that there will be payment parity between care provided in freestanding radiation therapy centers and hospital outpatient departments.

Options for Improving Alternative Payment Methodologies

Donald Berwick, president emeritus and senior fellow with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and former administrator of CMS, noted that of the 55 models CMMI has tested so far, only 4 have been certified for expansion

___________________

18 See https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/radiation-oncology-model (accessed September 9, 2021)

due to improvements in cost and/or quality and only 2 have been partially expanded. McAneny pointed out that none of CMMI’s current projects based on shared financial risk are resulting in savings. She suggested that CMMI consider new options for alternative payment methodologies. Buntin also urged that CMMI consider more comprehensive models for cancer patients, acknowledging that people with cancer may have more than one cancer care episode and often also have comorbidities that require care. She suggested that CMMI consider embedding people with cancer in other large demonstration projects and using value-based payment models to address social determinants of health that present barriers to people with cancer receiving quality care.

Strawbridge agreed that there is much to learn about why OCM has not achieved its intended outcomes, but noted that improvements in quality or health care utilization could still be realized before the model is completed. She said that CMMI would like to understand why OCM has not improved health equity, noting that while there is evidence that patient navigation can help to improve access to care and reduce inequities, it has not had this effect in OCM.

McAneny suggested that CMS adjust the payment differential based on site of service through the physician fee schedule. If not, she warned, more practices may move to hospitals, and costs for Medicare would increase. McAneny also pointed out that ACOs are starting to move high-cost patients to other systems. Additionally, she suggested that CMMI obtain accurate costs for optimal care before setting target costs or creating bundled payments, and include a cushion to cover practices with a margin.

PCORI

PCORI is an independent, nonprofit, nongovernmental research institute that was created by the ACA and has an independent board of governors. Steve Clauser, program director of Healthcare Delivery and Disparities Research at PCORI, said that the institute was initially authorized for 10 years and then reauthorized by Congress for another 10 years in December 2019. Clauser explained that PCORI implements a broad research program to respond to its core mission. He explained that some of the programs include funding comparative effective research that engages patients and other partners throughout the research process, and addressing “decisional dilemmas” about which therapies, drugs, and clinical-care strategies are best for patients and under what circumstances.

Clauser noted that PCORI was prohibited by statute from funding cost-effectiveness analysis, but since its reauthorization, the institute is allowed to consider costs and cost impacts on patients in its research. He said, for example, study outcomes can include the economic impacts of interventions,

including those that relate to the utilization of medical treatments and services. He said that costs may be broadly defined to include medical out-of-pocket costs, time costs, and other costs that patients and caregivers incur in the course of seeking care, such as child care, transportation, or lost time from work. Ellen V. Sigal, chairperson and founder of Friends of Cancer Research and a member of the PCORI board of governors, noted that the consideration of costs and cost impacts on patients in its research has allowed PCORI to define value and consider what outcomes are important to patients, in addition to cost.

Clauser outlined PCORI’s funding mechanisms to support comparative effectiveness research. They include competitive investigator-initiated research programs, broad and pragmatic clinical study funding announcements, and targeted announcements that address research topics and questions of national importance to patients and stakeholders, such as the opioid crisis, suicide prevention, and COVID-19. In addition, PCORI supports Phased Large Awards for Comparative Effectiveness Research (PLACER), which provides for a feasibility assessment of studies to address research questions of national significance that may involve more risks, such as enrolling hard-to-reach populations. The PLACER awards enable assessment of the feasibility of study implementation before committing substantial funds for full study implementation, he added.

Cancer-Related Initiatives at PCORI

Clauser said that as of January 2020, PCORI had committed $313 million to fund more than 80 comparative effectiveness research studies on cancer, which represents about 17 percent of all PCORI comparative effectiveness research awards.19 He stressed that cancer is second only to mental health in terms of its size and scope in the PCORI research portfolio. Clauser said that 70 percent of PCORI’s cancer-related research entails clinical trials. He said other cancer-related PCORI investments include 45 engagement awards designed to help build the capacity and skills to participate in comparative effectiveness research, three dissemination and implementation awards designed to put research findings into practice, and two systematic reviews on cancer topics to assess their research readiness.

Clauser noted that PCORI’s research awards cover the cancer care continuum and different cancer types and include a focus on patient and clinician education and care delivery strategies related to models of care, equitable access to screening, telemedicine, and patient navigation. PCORI research is

___________________

19 See https://www.pcori.org/topics/cancer (accessed September 24, 2021).

focused on the needs and preferences of people with cancer to improve health care decision making and outcomes, including caregiver outcomes, he said. He emphasized that having patients and family members engaged in defining the questions and key outcomes, and participating in the design of the studies can change the nature of research. Clauser said that more recently, PCORI has also begun to address research challenges related to social determinants of health at the levels of policy, community, and practice, through multicomponent, multilevel interventions focused on population health and initiatives focused on the upstream drivers of health disparities. Buntin urged PCORI to further engage with the cancer care community; federal agencies, including NCI and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and other national organizations relevant to cancer to better coordinate research priorities. Sigal suggested that PCORI could help to understand the long-term implications of COVID-19 for cancer patients and survivors, and by advocating for cancer clinical trials for patients with COVID-19 and other comorbid conditions.

PROGRESS, CHALLENGES, AND NEXT STEPS FOR HEALTH CARE REFORM

Using the Triple Aim framework of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Berwick explained that improving the health care system requires simultaneously improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita costs of health care. The Triple Aim framework20 serves as the foundation for organizations and communities to successfully navigate the transition from a focus on health care services to optimizing health for individuals and populations. Berwick outlined the four key factors that he considers when evaluating a proposed health care reform:

- Progress toward universal access to care

- Improvements in quality of care

- Impact on social determinants of health

- Reductions in health care cost, without causing harm or rationing care

Access to Care

Berwick said that health care reform should recognize health care as a human right, noting that the United States is the only Western democracy in which health care is not available to all by law. Berwick agreed with many

___________________

20 See http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx (accessed October 13, 2021).

other workshop speakers that the ACA fostered major gains in improving access to quality of health insurance coverage, noting that at least 20 million people gained coverage (CBPP, 2019). For example, the ACA improved the quality of insurance coverage by requiring coverage for preventive care without cost sharing and it eliminated lifetime limits. Berwick suggested that if the ACA had been fully implemented with Medicaid expansion in all 50 states, about 4 million more people would have insurance coverage. He said he has observed that the ACA has changed the mentality of many people in the country to begin thinking of health care as a human right. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of health insurance coverage, he added.

Sebelius agreed that the ACA has made significant progress toward universal coverage, but said that large gaps remain. She said that the most significant gap was created when a Supreme Court ruling made Medicaid expansion optional. Sebelius and Glied noted that some Americans who live in states that have not expanded Medicaid are left in the “Medicaid coverage gap” because their income is too low to quality for federally subsidized health insurance in the marketplaces. Sebelius said that another gap in coverage is the millions of workers who are not eligible for any health care benefits due to their immigration status, which can only be addressed by an immigration bill. There are too many people in the United States who are doing essential work but have no access to affordable health care, Sebelius stressed.

Berwick said federal regulations that were put in place in recent years have created new barriers to health insurance coverage and should be rolled back. In addition, he suggested, the dozen states that have not yet expanded Medicaid should do so for both moral and economic reasons. Berwick also suggested that there may be opportunities to expand coverage to more people through Medicare, either directly or via expansion of private coverage, such as Medicare Advantage. Sebelius agreed that a public option, such as through a further expansion of Medicaid or by lowering of the Medicare eligibility age, could significantly increase the number of people with insurance.

Quality of Care

Berwick noted that the dimensions of quality in health care as defined by a 2001 Institute of Medicine consensus study report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, are safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity of care (IOM, 2001). Using this definition of quality, Berwick said that the ACA has made good progress in improving quality of care, largely through CMMI, but challenges remain. Since its inception in 2011, CMMI has tested 54 models. Berwick said that successes include advancements in patient safety through Partnership for Patients, a public–private partnership implemented by

CMMI that offers support to physicians, nurses, and other clinicians working to improve the quality, safety, and affordability of health care. He explained that many of these quality improvements occurred through payment reforms linking payments to outcomes.

Looking into the future, Berwick suggested moving away from fee-for-service models that do not foster quality and continuity of care and investing in bold redesign of care delivery. He also suggested that it would be helpful for the cancer community to establish clear aims for quality improvement, to increase transparency, and to commit to adopt best practices for care. Additinally, Berwick suggested broadening the dimensions of quality and empowering patients by asking what matters most to them.

Patient Protections

Glied provided several suggestions for strengthening patient protections in marketplace plans. She suggested rolling back regulations that have undermined the marketplaces, including regulations related to short-term and association health plans that she said provide a “back door” to eliminating preexisting condition protections and provide inadequate coverage.

Responding to a question about what can be done to make the health care system more patient centered, Lori Pierce, president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), professor of radiation oncology, and vice provost for academic and faculty affairs at the University of Michigan, and Berwick emphasized the importance of transparency in providing equitable, high-quality care. However, Sebelius noted that transparency is not beneficial if people cannot act on the information to make the choices that reflect their priorities and circumstances. She said people do not want to process large amounts of complex information, so it is important to identify what patients, consumers, and others want to know, can understand, and can act on. She also suggested that increasing bundled care payments would prevent consumers from having to research relative prices for health care services at different facilities and would allow them to make decisions on the basis of quality measures. Pierce pointed out that treatment options may be limited for reasons other than lack of transparency, such as prior authorization rules, restrictive formularies, or step-therapy21 requirements.

Sebelius highlighted the important role that Medicare can play in improving cost transparency and coordinating with the private sector, noting that CMS data collection provides a platform for transparency across systems.

___________________

21 When an insurance company or pharmacy benefit manager requires a patient to try lower-cost medications without success before agreeing to cover a particular medication that the patient’s doctor prescribed.

Berwick also pointed out that transparency may be beneficial in fostering changes in clinical practice.

Network Adequacy

Glied suggested that network adequacy standards should go beyond transparency because consumers will not know what specialists they will need in the next year. She noted that network adequacy does not necessarily mean a broad network. Sebelius and Glied said that the size of the network matters less than the quality of the health care providers in it, noting that a narrow network with high-quality health care providers may be preferable to a broad network with many health care providers delivering suboptimal care.

Roy Jensen, director of the University of Kansas Cancer Center at the University of Kansas, pointed out that differences in survival rates between patients treated at NCI-designated cancer centers and non-NCI-designated cancer centers can be as large as 25 percent (Shulman et al., 2018), and asked why NCI-designated cancer centers are often excluded from networks. Sebelius answered that such decisions are made at the state and local levels, not at the federal level. Glied said that cancer centers should be innovators and developers of effective strategies, but they cannot be the only organizations delivering high-quality cancer care. Berwick suggested that the goal should be to raise the bar for everyone and ensure that all people with cancer receive high-quality care wherever they are treated. He added that cancer centers should be part of a holistic solution to American health care, and the initiatives around cost containment, improved care integration, and addressing disparities should be owned by the entire cancer community. Berwick suggested that CMMI could experiment with the role of cancer centers in the delivery of cancer care. Pierce and Sebelius suggested that an ideal solution could be a broad network with many hubs and spokes that lead to an NCI-designated cancer center, while still allowing patients to access care in their community.

Social Determinants of Health

Berwick stated that addressing social determinants of health is the “greatest frontier” in health and health care and that all health care reforms should invest in improving social determinants of health. He noted that most health harms come from issues beyond health care, such as environmental concerns, lack of educational opportunities, lack of security, and inadequate support for the well-being of children in a community. He emphasized that the actual causes of illness, injury, and disability lie in the structures of society and characteristics of the community, such as inadequate early childhood supports, education, workplace conditions and wages, the well-being of elders, com-

munity infrastructure, food insecurity, housing insecurity, lack of recreational opportunities, environmental threats, transportation inadequacy, and inequities in the criminal justice system. Unfair distribution of such factors creates health inequities, a topic discussed next.

Georges C. Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association (APHA), pointed out that social determinants of health include racism and other forms of discrimination. He said that race is a social construct that has no real biological basis, noting that it is racism that drives the distribution of the social determinants of health. He defined racism as a “false belief of superiority of one people over another based on race” that unfairly disadvantages the individuals that have been discriminated against. It also unfairly advantages the group that it is designed to benefit. He said that several types of racism exist in health care: structural racism, which includes societal barriers that lead to unequal access to care; personally mediated racism, which is the prejudice and discrimination against individuals; and internalized racism, which is the acceptance within the stigmatized group of the negative messages about their own abilities, capabilities, and worth (Jones, 2000).

Berwick stated that the greatest barrier to addressing social determinants of health is moving money from the current distributions to investments that address the social determinants of health and health inequities. He said that such a shift would require an “all-of-government” approach led by the White House and involving multiple cabinet departments, not only in the traditional health sectors like HHS and CMS. Pierce suggested that there is an opportunity to learn how social determinants of health interact, overlap, and influence cancer care to determine how best to improve outcomes for everyone. Sebelius also emphasized the importance of investments to address the social determinants of health, such as food and housing insecurity, and environmental concerns that affect people’s everyday lives and can lead to cancer.

Health Inequities

Benjamin said that there are many sources of health inequities, including differences in access to preventive, acute, and chronic care; differences in the quality of care received; individual differences in approach to health or health care; and differences in social, political, economic, or environmental exposures.

Benjamin shared a map of the Washington, DC, metro area, which shows that life expectancy varies by 8 years depending on the region in which one lives (VCU Center on Society and Health, 2016). He said that the situation is similar in other parts of the country, and he noted that U.S. communities are often segregated by race and income. For example, in St. Louis, Missouri, Delmar Boulevard acts as a dividing line between a lower-income,

less educated community and a more prosperous one, he said. The racial and economic disparities also mirror disparities in health, including rates of cancer and cardiovascular disease. Every community has a Delmar Boulevard, Benjamin said.

He emphasized that inequities in access to clean and safe water and clean air; lack of access to high-quality, nutritious foods; homelessness; levels of parental education; income; and environmental hazards all have an impact on societal health and well-being, including cancer risk. For example, lead exposure causes neural cancers, so access to clean, safe water is important for cancer prevention. Access to clean air is also important in reducing cancer risk because fine particulate matter in polluted air can cause lung cancer and brain cancer and is a major cause of poor health generally. Benjamin noted that some communities may be food deserts, with inadequate sources of fresh, healthy foods but an abundance of high-fat, high-salt, and low-nutrition foods in convenience stores and liquor stores, which also sell alcohol and tobacco products that are harmful in their own right. He noted that reducing tobacco sales and use could help to prevent cancer. Moreover, Benjamin said that people with more education and health literacy are more likely to seek out cancer screenings and high-quality care compared to people with less education. He added that income inequality also leads to health inequities, but several provisions in the ACA have helped to mitigate this relationship, such as coverage for preventive screenings without patient cost sharing. However, the cost of health care still presents a barrier to accessing care for many people.

Several speakers provided suggestions for improving equity in cancer prevention and care. Pierce outlined ASCO’s policy statement on cancer care disparities and health equity, which reviews the past 10 years of work in cancer disparities and provides recommendations for a path forward. She said that the four priority areas identified include equitable access to high-quality care, equitable access to research, addressing structural barriers, and increasing awareness of inequities and taking action. She added that COVID-19 has highlighted and intensified the challenges faced by people with cancer and highlighted preexisting health disparities. She said that ASCO convened a task force to explore clinical research and care delivery changes that can inform the “road to recovery” from COVID-19. ASCO’s report provides recommendations related to research, care delivery, and health insurance, including ways to make it easier for patients to participate in clinical research and clinical trials, ensuring that clinicians have the infrastructure to offer clinical trials, using virtual consent for trials and retaining expanded telemedicine access, integrating trials into routine care, streamlining regulatory requirements, and increasing access to affordable insurance (Pennell et al., 2021).

Sebelius suggested that interventions should be targeted at the community level to change the environment and social drivers to more effectively

address health disparities. She noted that President Biden has talked about the potential for increasing the number of community health workers and national initiatives to address disparities in a systematic way.

Huberfeld said that President Biden has issued several executive orders to address health equity. The executive order issued January 21, 2021, Ensuring an Equitable Pandemic Response and Recovery,22 created the COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force to make recommendations to mitigate inequities caused or exacerbated by COVID-19. She said that although the focus is on COVID-19, the task force has a broad mandate because nearly every health inequity has been exacerbated by COVID-19. Huberfeld noted that the executive order explicitly calls out structural racism in health care, stating that health and social inequities were particular problems during the pandemic. An executive order on January 28, 2021, Strengthening Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act,23 created an open enrollment period for the federal marketplace from February 15–May 15, 2021. In addition, the executive order directs HHS to perform a regulatory review to ensure that Medicaid is being implemented as intended, with year-round open enrollment and no additional barriers to access, such as work requirements.

Cathy Bradley, professor and associate dean for research at the Colorado School of Public Health and deputy director of the University of Colorado Comprehensive Cancer Center suggested that researchers should use rigorous research methods and quality data to document existing patterns and build a body of evidence for bold, creative solutions. Cleo Ryals, associate professor of health policy management and a health services researcher at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said that it would be helpful to prioritize equity in quality measurements so that efforts to improve overall quality do not unintentionally exacerbate inequities. Ryals emphasized the benefits of improving, standardizing, and synchronizing data collection on patient sociodemographic characteristics, such as race/ethnicity, gender identity, language proficiency, and social determinants of health; recording them in EHRs; and monitoring equity within and across practices and hospitals, health systems, and insurance plans.

Ryals also suggested gathering input from patients and community members about what measures are important to them. She also suggested reconsidering the analytic methods used to assess equity and quality. For example,

___________________

22 See https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/21/executive-order-ensuring-an-equitable-pandemic-response-and-recovery (accessed September 10, 2021).

23 See https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/28/executive-order-on-strengthening-medicaid-and-the-affordable-care-act (accessed September 10, 2021).

she said there are opportunities to incorporate social risk factors in quality measurement approaches that involve risk adjustment or risk stratification. Ryals also stressed that efforts to ensure clinician and hospital accountability for equitable care should not penalize facilities that care for a disproportionate share of BIPOC and other vulnerable patient populations. She further suggested aligning equity as a quality metric with payment and accreditation standards, noting that this would be critical to accountability.

Ryals described opportunities to address disparities using real-time health informatics tools. For example, a study at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill used a real-time registry to routinely monitor whether patient care milestones for breast and lung cancer were reached.24 If a patient did not receive care in the recommended time frame, an alert was automatically sent to the patient’s care team. Ryals noted that this model has been effective in closing gaps in the provision of timely care.

When asked how health care reform efforts can address structural racism and health equity, Strawbridge answered that it might be helpful to build on OCM’s investment in care coordination and management, with a focus on ensuring that the models are designed to promote health equity and justice. Three key components of such a model design could include (1) patient navigation and care planning, which are required in OCM for all patients; (2) quality measures, which OCM uses to address outcomes such as reduced emergency department use, increased hospice use, treatment for pain and depression, and improved patient experience; and (3) payment incentives, which could be structured to promote equity and justice.

A New Social Compact for Health

Benjamin spoke about the concept of a new social compact for health and how it relates to U.S. cancer care. He described this new social compact for health as an implicit agreement among members of a society to cooperate for the benefit of all. He acknowledged that this may involve sacrificing some individual freedoms for the good of the entire population, with a goal of movement from equality to equity to justice. Benjamin noted that the ACA is working toward justice by making sure everyone has access to high-quality health care and preventive services. He added that addressing racial discrimination and privilege is a fundamental part of the social compact. Benjamin said that APHA has a public health code of ethics that aligns with its core values, including ensuring equal access to health care for all. APHA addresses the social determinants of health through policies that enable income support

___________________

24 See https://chip.unc.edu/research/population-informatics (accessed September 24, 2021).

for accessing health care, criminal justice reform, affordable housing, and universal health care coverage, as well as strengthening environmental laws and strengthening education as a tool to allow people to better navigate the health care system.

Benjamin encouraged participants in cancer control to become community advocates and leaders, and to engage in the business sector on health issues from an economic perspective. For example, in his prior role as the head of the Maryland Department of Health, he said the power company was part of the cancer council and an effective tobacco control advocate, as an “unanticipated messenger.” Benjamin stated that the key to progress was to “change the hearts and minds of the vast middle,” because this is the group that has the economic and political clout to be impactful.

Reducing Costs

Berwick said that U.S. health care costs are about 18 percent of gross domestic product, more than in any other Western democracy. He noted that the ACA’s progress in reducing health care costs has been limited. It has bent the cost curve, but not enough, he emphasized. Berwick proposed using “global budgeting” for health care at the population level, noting that there is a lot of waste in health care. He suggested other ways to reduce health care costs, including simplifying or eliminating processes that do not add value, such as nonessential administrative tasks; coordinating and integrating care; and advancing virtual and home-based care, with a focus on access and equity.

Other speakers addressed patient cost sharing and value-based payments.

Cost Sharing

Glied emphasized the importance of addressing high premiums and out-of-pocket maximums in the marketplace plans. She said that expanding subsidies in the marketplace could benefit up to 4 million people, noting that out-of-pocket maximums in the marketplace are too high for all but very high-income Americans. For example, people with serious conditions like cancer might have to pay 30 percent of their income on premiums and out-of-pocket costs as their earning power is diminished by their illness. Huberfeld explained that the American Rescue Plan increases subsidies for low-income people purchasing commercial insurance in the exchanges. In addition, she noted that people earning just above 400 percent FPL, who are middle income and previously would not receive any financial support for purchasing insurance in the marketplace, would have a new limit on out-of-pocket health care costs.

Glied also explained that high deductibles can deter the use of effective care, but limiting out-of-pocket maximums is more important for people

with chronic conditions like cancer. Buntin also noted that a limit on out-of-pocket costs would particularly benefit cancer patients because some new therapies are very expensive and could otherwise cost Medicare beneficiaries thousands of dollars. She also suggested limiting price increases for drugs to the inflation rate.

Glied stressed that the out-of-pocket maximums should only be reduced after premium subsidies are increased. Otherwise, a reduction in out-of-pocket costs could lead to higher premiums and further reduce marketplace participation. Glied said that the current out-of-pocket maximum is about $8,500 for standard marketplace plans (Block, 2021). She explained that if premiums are instead capped at a share of income, as in the American Rescue Plan, the extra costs would be paid through subsidies, rather than premium increases. Sebelius also suggested providing increased premium supports for people in marketplace plans, including people with incomes above 400 percent FPL. Sebelius also lauded a provision in the American Rescue Plan that would cover the cost of continuation of health insurance through the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act25 for 1 year for people who are unemployed with incomes below 150 percent FPL.

Value-Based Payments

Sebelius suggested that outcome- and value-based payments should become the main way that Medicare and Medicaid pay for services. Sebelius cautioned that as long as Medicare uses fee-for-service payments, it will be challenging for the private sector to move toward paying for quality. Berwick and Glied agreed with moving away from fee-for-service, but also noted that challenges with risk adjustment and coding for value-based payments could allow gaming the system. Pierce emphasized the importance of incorporating the high cost of cancer care and cancer drugs into value-based payments to ensure that clinicians can treat patients effectively.

Effective Care Models

Pierce suggested that there are several successful models of care to scale and adopt. She described how the Delaware screening initiative, which was first implemented pre-ACA, is addressing the significant disparities in colorectal cancer screening and mortality rates between White and Black residents in the state. The program covered the costs of screening and care for people who

___________________

25 See https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/health-plans/cobra (accessed September 9, 2021).

were uninsured and resulted in the elimination of disparities in screening rates and incidence of colorectal cancer. It also reduced regional and distant spread of cancers in Black participants, and nearly eliminated the mortality differences between Black and White residents. The program saved $8.5 million in health care costs in the first year, more than enough to cover public and private payers’ spending on treatment for all types of cancer. Pierce noted that the program continues to be successful in improving health outcomes and is cost effective. She said that the program is an ideal example of the positive health outcomes and lower health care costs that can be achieved when a community of clinicians, patient navigators, social workers, policy makers, and other stakeholders come together to implement a screening program (Grubbs et al., 2013).

Pierce also discussed the Michigan Collaborative Quality Initiative (CQI).26 CQIs are statewide quality initiatives designed and carried out by physicians and focused on improving the standard of care for various metrics throughout the state, including some focused exclusively on cancer. Collaboratives develop comprehensive clinical registries that include patient risk factors, processes of care, and outcomes; collect data; and collaborate to measure and improve the standard of care. Michigan has the largest number of CQIs in the United States, with funding provided by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. Similar models are also implemented in other states and worldwide, Pierce stated. She explained that CQI models have saved money; lowered complication rates; and, in some cases, lowered mortality rates, resulting in substantial avoided costs. For example, the Michigan CQI saved Blue Cross Blue Shield $413 million over a 7-year period and resulted in about $1.4 billion27 in total statewide cost avoidance.

Sebelius asserted that CMMI is one of the most instrumental components of the ACA because it has administrative authority to test payment models and other strategies that could lower costs in Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. If a model is found to reduce cost or improve quality, without adversely affecting the other, CMS can administratively scale it nationwide, she added.

Randall Oyer, medical director of oncology at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health, asked how to make cancer patient navigation reimbursable, pointing out that patient navigation reduces the overall cost of care and emergency department visits, yet most programs are grant funded. Strawbridge responded that OCM requires all participating oncology practices to implement patient navigation activities as a condition of receiving the monthly MEOS

___________________

26 See https://ihpi.umich.edu/CQIs (accessed September 9, 2021).

27 See https://www.valuepartnerships.com/programs/collaborative-quality-initiatives (accessed September 15, 2021).