U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

National Institute of Justice

National Institute of Justice

|

Violence in Cornet: A Case Study by Patricia Kelly With contributions from Jeffrey Roth, Ph.D. Prepared for the National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice, by Abt Associates Inc., under contract#OJP-89-C-009. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. The National Institute of Justice is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Assistance, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for Victims of Crime. |

LIST OF EXHIBITS: PART A

-

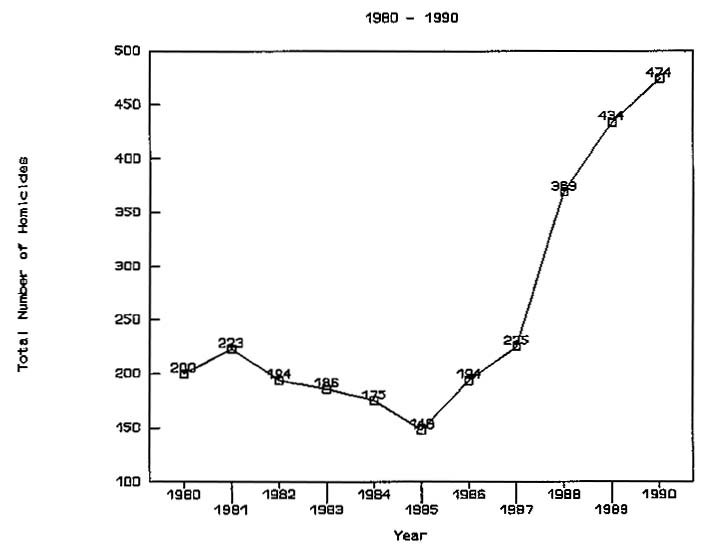

Homicide, 1980 - 1990.

-

Percent Arrestees Testing Positive for Drug Use, 1986 - 1990.

-

Drug Use Among Victims, 1985 - 1988.

-

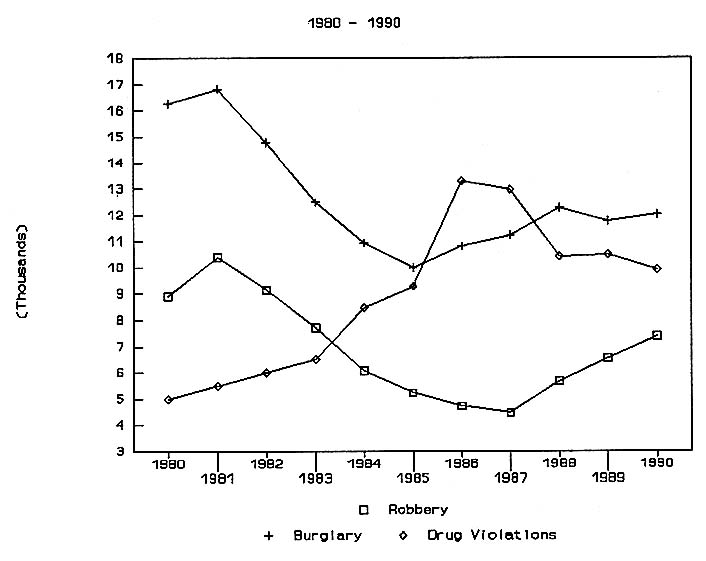

Robbery, Burglary and Drug Violations, 1980 - 1990.

-

Weapons Used in Homicides, 1980, 1985, 1989.

-

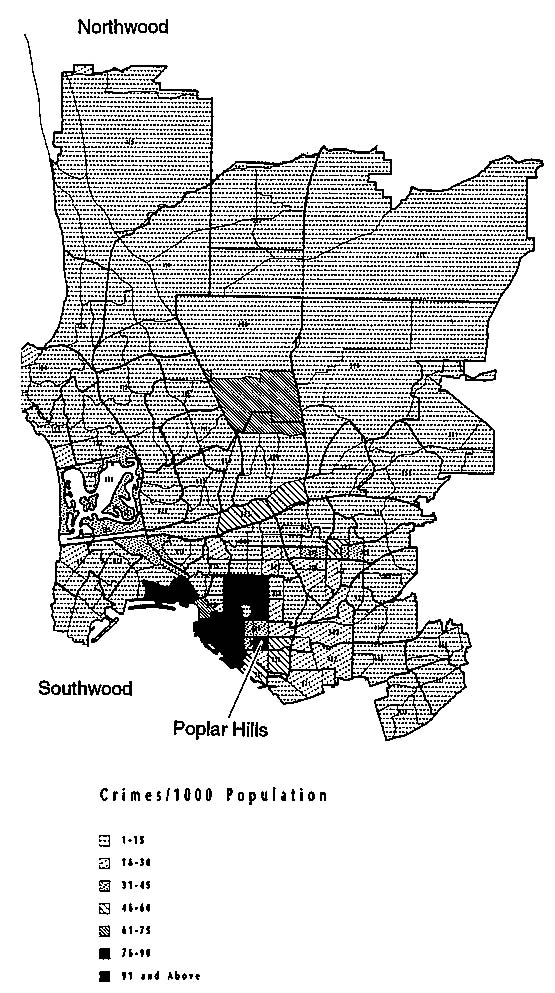

Map of the City of Cornet

-

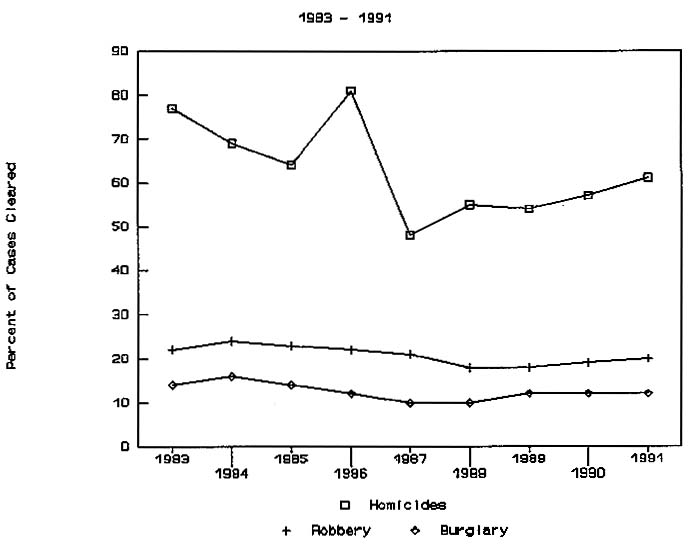

Clearance Rates for Part I Offenses and Drug Violations, 1983 - 1990.

-

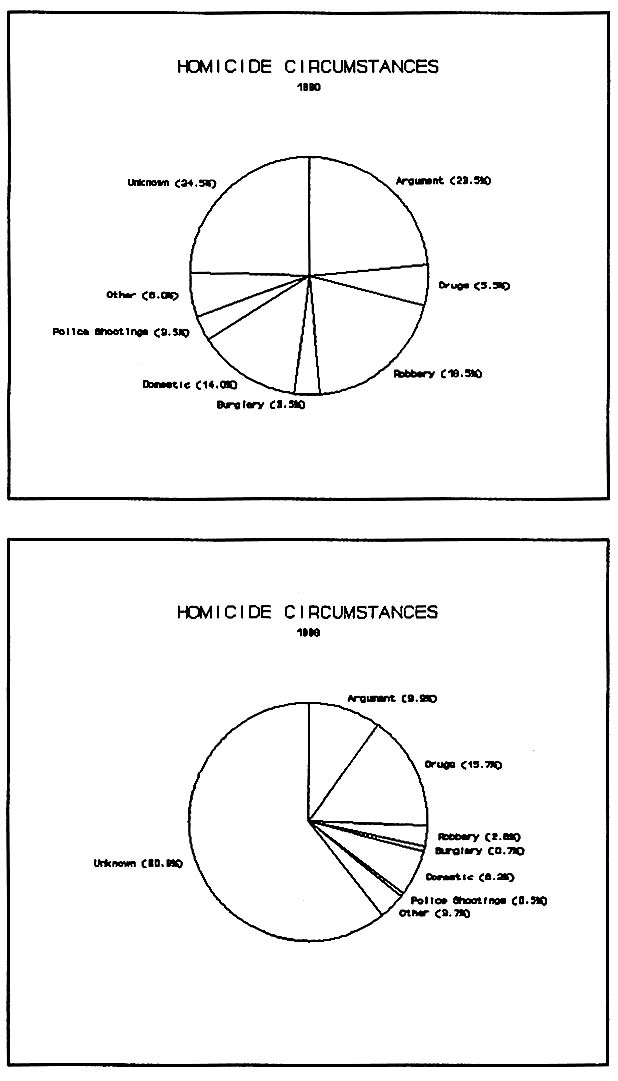

Homicide Circumstances, 1980, 1989.

-

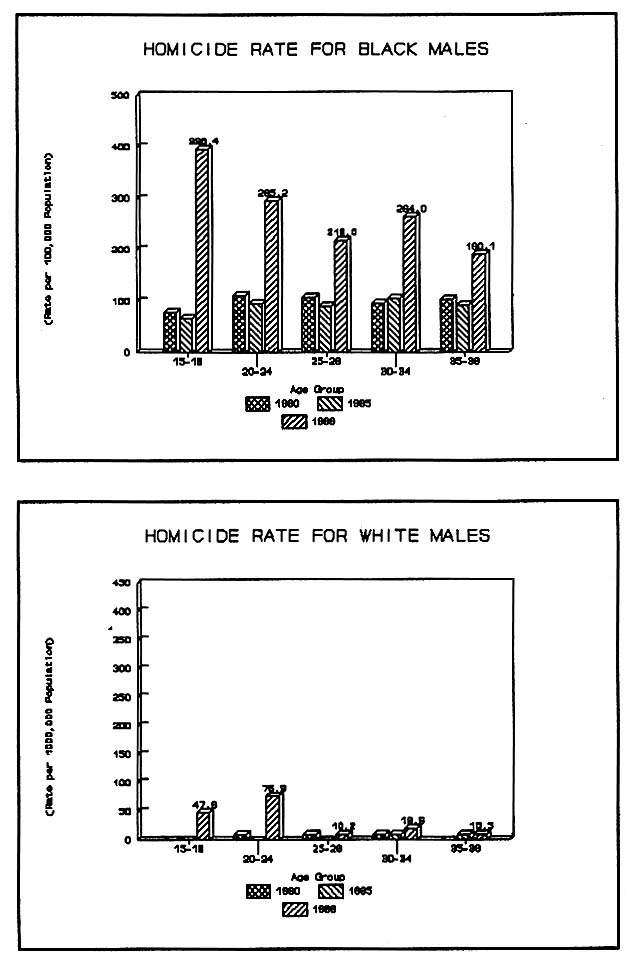

Homicide Rates for Black and White Males, 1980, 1985, 1989.

-

Major Causes of Death in Cornet, 1980, 1985, 1990.

-

Murder Assailants Under the Age of 18, 1986 - 1990.

-

Relationship of Victim to Offender

-

Cases Dismissed Due to Evidence Problems, 1974, 1990.

-

Cases Dismissed Due to Witness Problems, 1974, 1990.

PART A: THE PROBLEM

A. THEMURDEROFANITAWOODS

There were 12 shots: six in rapid succession; a pause; and then six more. Lydia Davis reached for the phone and dialed 911. There was a recording.

''You have reached the Cornet City Police Department. All of our operators are currently handling emergency calls. Please stay on the line and your call will be answered. Thank you."

Davis was not surprised that the line was busy. She had called the police on a number of occasions and this was not the first time she had gotten a recording. She was mad, however. How on earth could the emergency number ever be busy? The message was repeated 5 times before an operator answered. "Hello, how may I help you?"

"Gunshots in the 700 block of Forten Street, NW." Davis said wearily.

"How many gunshots, ma'am."

"Twelve, I think."

"We'll send someone right away."

She hung up. Davis called her neighbor, Martha. "Did you hear those gunshots?" she asked.

"Yeah. I can see whoever it is lying in a pool of blood right across the street from my house. I'm tellin' you, Lyd, I don't know how much more of this I can take." Martha Heywood lived on Forten Street, the main

hangout of the neighborhood's drug dealers. There were times when Heywood was kept awake all night by the constant traffic: cars driving up with their stereos blaring, dealers shouting to one another, the sound of bottles breaking. She was glad that at least she was retired and didn't have to get up for work the next day. She would get her sleep before noon, when the next shift of drug dealers began appearing.

"I'm coming around in a minute," Davis replied. She pulled on a jogging suit over her pajamas and grabbed her coat. As she was locking her door she saw other neighbors walking toward Forten Street, one block north of them. Davis was a 46-year-old office administrator who was relatively new to the neighborhood, having moved there 10 years ago.

This section of Southwood, called Poplar Hills, was populated by middle-income African-American families who had initiated the area's racial "turnover" in the 1940s. Poplar Hills was a mixture of semi-detached and row homes with small lawns and porches. The turn-of-the century residences had recently attracted a handful of young whites to the area, including college students looking for cheap housing away from the State University's main campus. However, the white population was still too small—and too 'poor,' in relative terms—to cause any real gentrification of the neighborhood. There was still a "small town" air in Poplar Hills, a sense of everyone knowing everyone else—which, indeed, they did. It was one of the things that attracted Lydia Davis to the place. She had never imagined that there was a drug problem in a neighborhood where small vegetable gardens could be found in many backyards, and a tricycle forgotten on the front lawn overnight went undisturbed.

"Here we go again," she said to herself, "we all come out here after there's been a shooting. We shouldn't be living this way. We know who these boys are. We know what they're doing. We shouldn't put up with this. We shouldn't." Davis joined a crowd of people standing a few yards away from the body.

"Who is it?" she asked her friend Martha.

"That Woods boy's sister." Mark Woods was 19 years old, and the youngest of four children. He and his sister Anita lived with their grandmother several blocks north of Forten Street. Mark was one of about a dozen neighborhood youths who hung out in front of a string of abandoned businesses on Forten Street, stepping up to cars to make unhurried drug sales. He was a 'lieutenant' in the street hierarchy: an intermediary between the local supplier and the boys and young men—and a few females—who made the actual drug transactions. It was clear from the way he carried himself, and the way others treated him, that he was powerful.

"Why on earth would they kill Anita? She wasn't dealin' those drugs, was she? I thought she was just usin' drugs. Are they starting to kill their customers now?"

"Maybe the ones who don't pay up," someone in the crowd commented drily.

"Or maybe they tryin' to get back at the brother," said Mr. Leonard Francis, who lived on 6th Street, a few houses down from Davis. "Gettin' back at him for something he did, through her." Francis was a retired government employee who was active in local politics. He had recently been elected the representative for Section 4C10 in the Southwood Civic Association.

"I don't care what the reason is, it don't make no sense."

Lydia turned to Mr. Francis. "Maybe we should form one of those neighborhood patrol groups like they have out in Northwood. We have enough people, don't you think?"

Francis shifted uneasily. "Yeah, sure, that would probably be all right."

Davis was dismayed by his tepid reaction. He was one of the most outspoken people at all the community meetings, talking about how we shouldn't wait for the police to do things, we should take the matter into our own hands. But he had never tried to form a citizens' group.

"We too old to be out here standin' on the corner against these boys. You see how ruthless they are. What makes you think they're gonna pay attention to us?" This comment was from Hattie Mason, a retired school teacher who also lived on Forten Street, two doors down from Martha Heywood.

As Davis stood there, listening to her neighbors, she began to feel increasingly frustrated. Why couldn't they all band together and try to do something? Of course, some of these people were the parents or grandparents of the children who were tearing the neighborhood apart; it wouldn't be surprising if they were against a patrol group. But what about the others?

The young women who had been shot was loaded into the ambulance. Her brother Mark, the drug dealer, was pacing angrily, his eyes glassy with tears. "I'm gonna get 'em," he kept saying, his teeth clenched. "I swear I'm gonna get 'em." His friends stood nearby, hands deep in their pockets.

B. A WEEKENDOFVIOLENCEANDTHEGOVERNMENT'SRESPONSE

The next morning, the death of Anita Woods made the front page of the Cornet Courier:

Six Slain in Weekend Murders Victims Include 3-Year-Old

In the city's bloodiest weekend this year, six people died under circumstances ranging from child abuse to robbery.

On Friday evening there was an emergency call to an apartment in the Southwood section of the city, where police found a 3-year-old girl on the livingroom floor. The child had broken bones and multiple skull fractures, and was pronounced dead at the scene. Frank Cartwell, the common-law husband of the child's mother, was taken into custody. The mother has not yet been located.

In a second domestic matter a woman was shot by her estranged husband as she left her apartment. The previous week Teresa Cordoba had tried to get her husband arrested for threatening to kill her. A restraining order had been issued, according to Superior Court officials.

On Saturday night a convenience store clerk was shot twice in the head after being robbed by two men. Sung K. Suk, father of the slain man and the store's owner, witnessed the murder. He said that his son had offered no resistance. "He had given them [the] money and he was on his knees with his hands on [his] head. But the guy stood there…shot him point-blank. It was really brutal."

Early Sunday morning an argument in the parking lot of a local bar left one man dead of multiple knife wounds. His assailant, Lawrence J. Peterson, also was wounded during the altercation and is listed in stable condition at the County Hospital. Patrons of the Hitching Post said the fight started when Peterson and the deceased, Michael Harrington, tried to leave the parking lot at the same time and had a minor collision. This was the third violent altercation at the bar so far this month.

A 17-year-old restaurant employee who was fired last week returned to his former place of work and opened fire on employees in the kitchen. The restaurant's owner was killed and several employees were wounded, one seriously. The youth, whose name is being withheld because of his age, fled the scene but was later arrested at his home.

Finally, 22-year-old Anita Woods was gunned down in the 700 block of Forten Street, in an ageing section of Southwood known as Poplar Hills. CCPD detectives report that they have no motive at this time…

The article provoked a political firestorm; city officials were deluged with calls from citizens demanding action. Commissioner Willie Farnsworth, chairman of the Public Safety Sub-Committee, said that his office alone received 300 calls within hours after the story was published. "The people who have been calling my office are just fed up. This violence is getting totally out of control, and they want something done about it," he said, "we have got to get these criminals off our streets.

"I have been calling for a tougher approach to law enforcement for years, and maybe now the mayor will listen. This latest bloodbath makes it clear that the criminals control our city, and we need to take back our streets from them. I am calling once again for reinstatement of the death

penalty. We also need to lower the age when you can try as adults these young thugs out here who are literally getting away with murder. We are living in extreme times, and we need extreme measures to bring this situation under control.

"We've also got to have longer sentences to keep these violent criminals in prison, where they belong. Let's give the streets back to the lawabiding people. We've got it backwards right now—it's the good people who are locked up in their homes, and the criminals who are roaming the streets freely. This has got to be rectified. The people of Cornet deserve better, and I hope that the City Commission is ready to do what's necessary to stop the insanity in the streets."

In his oblique criticism of the City Commission, Farnsworth was targeting Martin McCafferty, chairman of the Commission's Human Services Sub-Committee. McCafferty was often pegged as the Commission "liberal" because of his voting record on the "law-and-order" issues—particularly his efforts for stringent gun control. He, too, made a statement to the press.

"It is easy to get emotional when these kinds of tragedies occur, but we need to look at the facts. In four of the six murders we had this weekend, guns were used. One of them, I believe, was a young man who, in a fit of rage, went home and got his father's gun to kill his boss. The only reason that that man is dead, and the only reason the other people in the restaurant are in the hospital today, is because the young man had access to a gun. That's the only reason. The way to stop the carnage is not just to say we're gonna lock people up after they've already killed someone. The answer is to take away the means to kill. We are not going to eliminate homicides in this city, but at least we'll prevent a lot of them."

The mayor's office also was swamped with telephone calls and even a few telegrams from angry citizens. By the end of the day, mayor Chris Warren had called a press conference. Flanked by the Deputy Mayor and the Chief of Police, Warren read from a prepared statement.

"This weekend's spate of murders in our city has been a wake-up call for all of us. I have heard from every group in the city: the old and the young; working and retired; male and female; black and white. I have heard from the citizens of Northwood, and those of Southwood, from the business community and from government workers. The citizens of Cornet agree, and I am in full accord, that something must be done. This city—indeed, this nation—is awash in blood. It must stop.

"Today, I am charging 12 people to come up with a plan in 100 days to deal with the problem of violence in Cornet. The members of the AntiViolence Task Force will be: Police Chief Tony Burnett; two of my colleagues from the Commission, Willie Farnsworth, who chairs the Public Safety Sub-Committee, and Susan Wolfe, chair of the Tourism and Economic Development Sub-Committee; the Honorable Connor Bradley, senior

judge in the Juvenile Court Division; David Silver, chief prosecutor; Thomas Eckert, Commissioner of Prisons; Stephen Balliet, President of the Chamber of Commerce; Samuel Lee of the Small Business Association; Sheila Robinson, Commissioner of Public Housing; the Reverend Aaron Weems; and Dr. Gail Hodges, professor of urban studies at the State University. Chairing the Task Force will be Deputy Mayor John Canady."

The duties of the Task Force were threefold: first, to attend community meetings throughout the city to get firsthand knowledge of the nature of the problems faced by different constituencies, and to gather information on effective grassroots initiatives. Second, the Task Force would hold citywide public hearings to obtain testimony from "experts" as well as local citizens. Finally, the Task Force had to review the history of antiviolence and anticrime initiatives before developing a strategy. They could also evaluate efforts in other states, as well as any national programs and policies.

"This Task Force will look at the causes for the skyrocketing homicide rate, and it will develop concrete solutions. I am authorizing and requiring that they mobilize every member of this city, from the grassroots level to the government bureaucracy. Every one of us has got to be a part of this effort, because crime and violence are the number one problems facing this city and this nation. Violence affects everyone, and stopping the violence has got to be everyone's priority."

C. THEVIEWFROMTHEPOLICEDEPARTMENT

After the press conference Chief Anthony Burnett got into his car and returned to the office. He felt a little subdued. More than anyone else, he knew that violence was now a commonplace in Cornet. Although he wanted to see an end to the problem as much as anyone else, it worried him that such an important public policy issue was taking place in a highly-charged, politicized context. There also would be intense pressure to solve the six weekend murders. Burnett used his car phone to call Deputy Chief Jerry Rauss.

"Hello, Jerry, this is the Chief. I'm calling about this Task Force thing. Yeah, it's going to be hell. Listen, I want you to call each of the precincts where those six weekend murders took place, and tell them that we're sending our best homicide detectives to their areas and I want full cooperation from everybody. Next, I want you to call down to ODA [the Office of Data Analysis] and tell them to bring me everything they've got from 1980 to now on homicides: number of people, motives, weapons used. Everything. I want to meet first thing tomorrow morning."

1. The Office of Data Analysis

ODA was located in a large room shared by Jack Newman, the Director; Sylvia Patton, a Research Analyst; a data entry clerk; and a secretary. There were printouts everywhere, and boxes of papers were stacked in every corner. Newman and Patton had stayed late to get the Chief's data. They walked into his office the next morning with a sheaf of documents.

"Well," Newman began, "including the death of Anita Woods this past weekend, a total of 452 have died in Cornet this year." "If this keeps up, we'll have another record-breaking number of deaths. We've only got a population of 600,000 so if this continues, our homicide rate will rival that in urban areas like the District of Columbia, Chicago and New York City."

"That's a distinction we definitely don't want," the Chief replied. ODA data showed that, after several years of decreasing homicide rates, in 1985 the number of murders in Cornet began to climb precipitously, from 148 in 1985 to more than three times that number by the end of 1990. (See Exhibit 1.) More than half the victims were black, mirroring national trends.

Exhibit 1:

HOMICIDES IN THE CITY OF CORNET

Exhibit 2:

PERCENT ARRESTEES TESTING POSITIVE FOR DRUG USE 1986 - 1990

|

|

1986 |

1987 |

1988 |

1989 |

1990 |

|

|

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

|

Homicide Arrestees Testing Positive for: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Any Drug Use |

44 |

49 |

64 |

35 |

26 |

|

Cocaine Use |

25 |

31 |

49 |

32 |

23 |

|

PCP Use |

24 |

25 |

25 |

5 |

3 |

|

All Arrestees Testing Positive for: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Any Drug Use |

68 |

72 |

73 |

67 |

56 |

|

Cocaine Use |

40 |

50 |

64 |

63 |

53 |

|

PCP Use |

39 |

43 |

33 |

17 |

7 |

Newman continued. "When you look at the information we're getting—from lock-up, the coroner, the Supplementary Homicide Reports—you see that drugs see to be the main problem." First, the number of homicide arrestees testing positive for any drug use rose from 44% in 1986 to 64% in 1988 and declined after that. (See Exhibit 2.) In the general population of arrestees—for violent and property crimes—drug use was even more prevalent: a record 73% tested positive for any drug use in 1988, with small decreases observed since then.

A significant number of murder victims also had some type of drug or alcohol in their systems at the time of death. Toxicological data for the period 1985-1988 showed that PCP, cocaine or alcohol was found in the bodies of almost two-thirds of all murder victims. (See Exhibit 3.) While the overall fraction of victims using any drug had remained roughly constant over the period, a review of victims' drug use trends showed substantial differences by type of drug:

-

victims' use of alcohol, while still among the highest of all psychoactive

Exhibit 3:

DRUG USE AMONG VICTIMS, 1985 – 1988

|

Substance |

1985 |

1986 |

1987 |

1988 |

|||||

|

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

||

|

PCP |

23 |

15 |

55 |

27 |

73 |

30 |

26 |

22 |

|

|

Cocaine |

26 |

17 |

54 |

26 |

70 |

29 |

54 |

45 |

|

|

Heroin |

21 |

14 |

25 |

12 |

8 |

3 |

8 |

7 |

|

|

Marijuana |

19 |

12 |

60 |

29 |

57 |

24 |

27 |

23 |

|

|

Alcohol |

59 |

38 |

60 |

29 |

57 |

24 |

27 |

23 |

|

|

Other |

17 |

11 |

2 |

1 |

12 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

|

|

None |

56 |

35 |

78 |

37 |

93 |

38 |

39 |

32 |

|

|

No. Cases Tested |

156 |

|

207 |

|

242 |

|

119 |

|

|

|

Source: Homicide in Cornet City, December 1988, p. 10. |

|||||||||

-

drugs, had been declining, from a high of 38% in 1985 to 23% in 1988;

-

heroin use had fallen by half, from 14% in 1985 to 7% in 1988;

-

marijuana use had almost doubled, from 12% in 1985 to 23% in 1988;

-

use of PCP fluctuated during that period but was very high, ranging from 15% in 1985, peaking at 30% in 1987 and dropping to 22% in 1988;

-

cocaine had become the most commonly used drug, its use increasing dramatically from 17% in 1985 to 45% in 1988.

Next, there were more drug arrests than commissions of either robbery or burglary. (See Exhibit 4.) Starting in 1985 there had been a dramatic increase in the number of drug violations and the following year drug arrests exceeded the number of actual robberies or burglaries. These data did not necessarily indicate that the number of drug-related crimes was overtaking the numbers for other Part I Offenses—only the fact that apprehension rates for robberies and burglaries remained low. Nevertheless, homicides continued to rise even as arrests for drug violations began to fall.

Finally, Newman presented data on murder weapons. "As you can see, firearms continued to be the weapon of choice. Over the last decade, the percentage of homicides involving gun use rose from 62% to 76%." (See

Exhibit 4:

ROBBERY BURGLARY AND DRUG VIOLATIONS

Exhibit 5.) The Chief recalled hearing one of the Commission members talk about gun control on the previous day, and wondered how the ODA information would be put to use.

Now that he had the big picture, Burnett began to consider the individual cases. Two domestic situations; one robbery with a possible racial component; a disgruntled employee; a barroom brawl. Then there was that young woman gunned down in Southwood.

"I want to be informed on a daily basis about the progress of these cases," he told the Deputy Chief. "The whole city is watching. Use whatever resources are necessary to get the cases solved. Especially that 22-year-old woman, Woods. She's the only one with an unknown motive at this time, is that right?"

"Yes, sir. Detective Soames has been assigned to it."

Exhibit 5:

WEAPONS USED IN HOMICIDES 1980, 1985, 1989

|

Weapons Used |

1980 |

1985 |

1989 |

|

Firearms |

124 |

95 |

331 |

|

All Other |

76 |

53 |

103 |

|

Total Homicides |

200 |

148 |

434 |

2. Investigating the Murder of Anita Woods

Detective Franklin Soames had arrived at the murder scene not long after Anita Woods' body was taken away. In his inspection of the site he found one bullet lodged in the side of the building where the woman had been standing just before she was killed. Several bullet shells were found in the street.

The only other clues Soames could hope to obtain would be from members of the dead woman's family, or people who lived in the neighborhood. He was not at all hopeful that he would in fact get information from any of them. An officer on the scene had told Soames that the girl's brother had been walking around crying, and talking about avenging her death. But the young man had been unwilling to talk to the police and had even dismissed them angrily, spitting out that they were never around when you really needed them. There seemed to be more to his unwillingness to cooperate than just grief, though. Soames discovered that the brother had a record: possession with intent to distribute cocaine. It seemed likely that Mark Woods was a drug dealer and that this was a factor in his sister's murder.

''Very few of the cases I see now are, you know, the typical murders that we were dealing with ten or even five years ago." Soames was speaking to a reporter from the Courier who was doing a follow-up story.

"Now there's almost always a drug connection. It's drug dealers beefing with each other over territory. Or it's a dealer killing off a customer who won't pay up—the dealer feels he's got to kill the person otherwise he's gonna be considered a punk [weakling] on the street. And it's really hard to solve these cases because nobody wants to come forward—they can't, really, because then they'd be admitting that they're involved in something illegal. The people on both sides are 'bad' individuals, and there's no incentive for anybody to cooperate."

Soames drove back to his office and stuck a pin in the map in back of his desk. (See Exhibit 6.) Anita Woods' death had occurred in Southwood,

one of the prime drug-dealing sectors of the city. "Look at this," he said. We've had, what, 450 murders so far? Over half have been here in Southwood." Both geography and demography made the Southwood area a magnet for drug activities, for it was not only the poorest section of the city, it was on the state border, attracting carloads of out-of-state buyers and sellers.

Soames turned his attention back to the Woods murder, and the unlikelihood of getting any evidence to solve it. The families of the victim had no incentive to cooperate with the police, and members of the community faced real disincentives. "I know that somebody in that neighborhood—lots of people—know something, or heard something. But I can't get them to tell me. And you know what? I don't blame them. Not really. Because if word got out that they said anything then these people could get killed." Intimidation and murder of witnesses had become so common that when Soames wanted to get information he would never approach the person in public. He knew from personal experience that drug dealers would not hesitate to kill a 'snitch.'

"We're just not dealing with the same kinds of criminals," he lamented. "They will kill people on mere suspicion of talking to the cops. I used to tell informants that they didn't have to worry about anything happening to them, but I don't anymore. Because some people I swore to protect got popped. You can't imagine what that does to a police officer, someone who is out there to protect people. When you give people your word, lay down your honor like that and then you're not able to come through…" he trailed off, shaking his head. He understood why law-abiding citizens refused to "get involved." He understood their fear because he, too, was afraid.

"I've been on the force for 19 years, and doing homicide for 6 years. When I started out in this job I wasn't afraid, not at all. I mean, sometimes I would be outnumbered by the crooks, you know, but I wasn't afraid because number one, they didn't used to have guns; and number two, I had this… you know, authority. I don't mean that I was abusive or anything. Just that people had some kind of respect for police officers. Both the 'good' people and the 'bad' people. Now, though… these guys out here are better-armed than I am. Not only that, they're not afraid to kill. Even if you're a police officer." The data did indicate that police work was dangerous, with 138 assaults on police officers in 1990, 13% of them involving a gun.

Without witnesses or other information, it was going to be very hard to solve the Woods case. As shown in Exhibit 7, the police department's closure rate for homicide cases peaked in 1986 at 81%, but by 1990 the rate was only 57%. Clearance rates for other Part I offenses, while lower, had remained virtually constant since 1983, ruling out a general "police overload" explanation. It seemed clear that it was the nature of the murders that

Exhibit 7:

CLEARANCE RATES-PART I/DRUG VIOLATIONS

was making it difficult to solve them. "In the old days you had lovers' quarrels, or maybe an argument between friends," Soames explained. "You would usually get the murderer to confess right there on the spot. But now you've got nothing to go on. No witnesses, no anguished parents demanding justice, nothing."

An examination of known circumstances for murders over the last decade supported him. (See Exhibit 8.) In 1980, police were able to determine the circumstances under which death occurred in 75% of their cases, including: arguments/altercations (23%); robbery (19%); domestic disputes (14%); drugs (5%); burglary (3%); and police shootings (3%). By 1989, police were recording the reasons for less than half their cases: only 39% had a known motive or assailant. Even more intriguing, in cases where police could determine neither the reason nor the offender, the majority of victims (76%) were black males between the ages of 16 and 39.

Indeed, homicide among black males was noted with alarm by many groups; these rates were many times higher than that for white males, at

every age. (See Exhibit 9.) In the last decade, homicide had become the major cause of death among black males, particularly young men between 15 and 19 years of age. (See Exhibit 10.) High rates of homicide for other age groups were lower but still significant.

Not only were the victims young, so were the assailants: the fraction of murderers under age 18 had tripled in the last five years, from 6% in 1986 to 20% in 1990. (See Exhibit 11.)

With killers and victims both being so young, journalists often tried to portray the killings as a gang problem. Soames remembered trying to explain the situation to a tabloid reporter a month earlier. "Look, kids do everything else dressed alike and traveling in groups, so they commit crimes and do drugs dressed alike and traveling in groups. But that's got nothing to do with big, formal gangs with initiation rituals, turf staked out, protection rackets, and all the stuff you read about in places like Chicago and Los Angeles. Here in Cornet City, you might have 6 or 8 guys hanging out together for a few months, maybe dealing some drugs or knocking over a liquor store or two. It's serious stuff, but they don't hang together for long, and there's no organized leadership. Maybe we'd have less violence if the

Exhibit 10:

MAJOR CAUSES OF DEATH IN CORNET BY YEAR

Age 15-19 at Death

|

|

Black Males |

White Males |

Black Females |

White Females |

|

1980 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total Deaths |

26 |

2 |

10 |

1 |

|

Homicide |

18 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

|

All Other |

8 |

2 |

7 |

1 |

|

1985 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total Deaths |

19 |

2 |

6 |

0 |

|

Homicide |

12 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

All Other |

7 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

|

1990 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total Deaths |

84 |

6 |

7 |

1 |

|

Homicide |

70 |

5 |

5 |

1 |

|

All Other |

14 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

Exhibit 11:

MURDER ASSAILANTS UNDER THE AGE OF 18

|

1986 |

1987 |

1988 |

1989 |

1990 |

|||||

|

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

8 |

6 |

9 |

7 |

26 |

14 |

63 |

19 |

67 |

20 |

kids were better organized… they'd work out their own rules so there would be fewer 'beefs' to turn violent. When there was a gang hassle that turned violent, you could expect the leaders to work it out like they did after the riots in LA. Here in Cornet City, no one's in charge, so there's no telling what's going to set off a chain of killings, and it's awfully hard to turn things around." Despite this detailed explanation, the day after the interview the headline read: GANG VIOLENCE PLAGUES CORNET CITY, POLICE SAY. "No offense to you, but reporters are really a pain."

Soames worried about all the publicity, and the pressure to solve this murder. Even as he had watched yesterday's press conference, he knew that Chief Burnett would be expecting results. He jotted down a few notes and put them in a file marked "WOODS, A. - 12/11/90." He then began to review his other cases, most of them unsolved. "No, we're just not dealing with the same kinds of cases anymore."

D. THEVIEWFROMTHEPUBLICHEALTHDEPARTMENT

Another person who had watched the mayor's press conference was Dr. William Freis, Commissioner of Public Health. Freis noted with dismay that the mayor had named representatives of all the usual law enforcement perspectives to the Task Force: police, courts, prisons. Only two or three people from the 'human services' view were represented. Freis decided to ask the Mayor and ask to be included on the Task Force.

"Mayor Warren," he began, "there are compelling reasons why I should be part of this initiative. Let me put it to you this way: last year there were roughly 200 deaths from pneumonia or the flu, and almost 200 deaths from diabetes. But so far this year, more people have been victims of homicides than from these other two sources combined. If you consider the flu and diabetes to be serious health problems, why aren't we looking at homicide as a serious health problem? If the public health community is concerned that 458 people died from tuberculosis, which is preventable, we should be just as concerned that an equal number of our citizens are dying from guns, knives, and beatings. These deaths are also preventable. We need to start

looking at the problem of violence differently, as a public health issue and not just a law enforcement issue."

Freis was part of a growing movement among health professionals to broaden the definition of public health to "get the topic of violence into the 'mainstream' of public health policy." They argued for a mandate "from the highest levels of government to the individual members of society" to address violence as a health problem that had ramifications for the entire nation. For example, the economic costs of violence include not only expenditures to arrest, try and imprison offenders. They also include medical and psychiatric care for victims; their lost earnings; and, most important, years of potential life lost. It was estimated that homicides and non-fatal violent injuries cost the nation $180 billion dollars in 1990.

In his discussion with the mayor, Freis pointed out that he would like to apply the same epidemiologic procedures to address violence as a cause of death as he would to investigate any other disease or condition. "The issues we need to be concerned with are: who is this 'disease' of violence affecting? What are the risk factors? Where is the violence taking place? Are certain groups more affected than others? What are the circumstances surrounding these deaths? What would be the appropriate interventions for each of these circumstances? These are the things we need to be looking at."

A cursory epidemiological analysis of homicide and violence produced two important observations. First, much of the victimization occurred among black and low-income populations. Freis was concerned that these simple descriptive statistics would be interpreted causally— as confirming the stereotype that African Americans were more violent than whites. He showed, however, that once one controlled for socioeconomic differences between blacks and whites, the racial differences disappeared. This led him to the view that the real explanation for the high rates of violence lay with poverty and inequality rather than race. It was important to know that the worst consequences of violence were accumulating within the African-American community. But that should not be taken as evidence that African Americans were inherently more violent than whites: they were neither more nor less violent than whites of a similar socioeconomic status.

Second, although a lot of attention was focused on drug-related murders, and in particular the extremely high murder rate among young black males, outside of these special circumstances, most victims were killed by people they knew—very often family members.

"Most family homicides involve spouses and occur in the home," Freis explained. "Citywide hospital data show that when women are killed by the men in their lives, it's usually after many, many assaults. Doctors' offices, clinics and hospitals are a real flash point. They should be considered 'sentinel' points because they offer an opportunity for prevention. When

Exhibit 12:

RELATIONSHIP OF VICTIM TO OFFENDER

|

Percent of Victims Killed by: |

MALE VICTIMS |

FEMALE VICTIMS |

|

|

Spouse/Lover |

6% |

30% |

|

|

Other Family Member |

8% |

12% |

|

|

Friend/Acquaintance |

45% |

25% |

|

|

Stranger |

16% |

9% |

|

|

Unknown |

30% |

27% |

|

|

Source: Understanding and Preventing Violence, NRC, Table 2.6, p. 80 (1993). |

|||

we fail to break these cycles of spouse assault, the burden falls back on women."

An analysis of the relationship of the victim to the offender showed that women were more likely to be killed by a spouse, lover or other family member; while men were more likely to be killed by friends or acquaintances. (Exhibit 12.) "You see, the circumstances of murder are very different, so the strategies would be different. A violence prevention strategy for women, for example, might focus on therapy for their partners on anger management, or couples therapy."

And familial abuse wasn't just limited to husbands and wives. The number of Cornet children dying of abuse or neglect had doubled in the last two years: from half a dozen in 1989 to 13 in 1990. The mother was as likely to be the perpetrator as the father. Cornet saw almost 1800 reported cases of child abuse in that same year. At the same time, social service workers could only respond to the most extreme cases: budget cuts in the Department of Human and Rehabilitative Services had reduced the number of child abuse case workers by half. Without the money to hire appropriate staff, the agency had little time for prevention.

Freis concluded his pitch, hoping that his frustration wasn't too apparent. "The fact is, the law enforcement system is not adequately addressing the violence issue. It isn't even a question of giving them more resources, or whatever, because most violent incidents don't pass through the law enforcement agencies. We have battered women in our hospitals who don't press charges against the men who abuse them, so the police aren't intervening there. We see a lot of children with Shaken Baby Syndrome in our clinics. We've got doctors and teachers and social service people who, for whatever reason, aren't reporting suspected cases of child abuse. So the police aren't able to protect that population. Mayor Warren, we can't ignore the fact that the health care system sees more preventable violence,

there isn't any reason to wait until there's a homicide for the criminal justice system to step in. Then it's too late. You've got to do more than just get additional cops and longer prison terms. That approach isn't going to reach everybody who needs help.''

From a practical standpoint it was impossible to ignore violence as a public health issue because medical professionals were already dealing with the problem. Public medical facilities like the County Hospital in Cornet were overwhelmed, for example, with multiple gunshot wound cases. These patients, many of whom had no health care, were an additional burden in financial as well as medical terms; hospitals were reeling from the large increase in AIDS patients and a poor population that was often forced to use emergency rooms as a source of primary health care.

Freis had one last request. "I must tell you Mayor Warren that I'm surprised that someone representing the schools isn't on the Task Force. We need to include the schools in this dialogue for two basic reasons. First, we have an awful lot of violence taking place in the schools. Second, the schools can be part of the solution: they can teach young people about conflict resolution. I think someone from the School Board needs to be represented."

With some misgivings, Mayor Warren appointed Freis to the Task Force. He was worried that the Health Commissioner's prescription would require expensive programs that were no longer feasible in the current fiscal climate. Large funding requests by both law enforcement and social service agencies might force a trade-off between the two approaches, or a compromise where neither of them would get enough money to do anything effectual.

Warren also agreed to appoint School Board President Monica Reeves to the Task Force. He hoped this would end the lobbying for "a place at the table." Warren could not spend too much time worrying about it, in any case. He had to make some immediate decisions about which of many community meetings held throughout the city should be attended by Task Force members, and who should testify at the public hearings scheduled for the next 3-1/2 months. One certainty was that Southwood would be a major focus.

E. A COMMUNITYMEETINGINPOPLARHILLS

Lydia Davis had also been making decisions. After being questioned by Detective Soames, she asked for the name of the local district police commander and, after consulting with several neighbors, arranged to meet him at the local church. Because of the publicity surrounding the death of Anita Woods, this was one of the community meetings that Task Force

members had been asked to attend. The prosecutor and Chief Burnett sat quietly in the last pew.

Representing the local precinct was Captain Michael McDougal, a 22-year veteran of CCPD who had found himself attending a lot of community meetings in the last few years. His approach was never to make excuses for the police but to present residents with all of the facts. He began his meeting with Lydia Davis and her neighbors by talking about the lack of resources in the police department.

"I know you probably don't want to hear this, but resources are the number one reason why we can't do as much as we want, and what really needs to be done, in your neighborhood—or any other for that matter. Last month we only had 7 cruisers out of 19 available, because the others were either in the shop or they had been totaled in accidents.

"And then there's the problem with not enough police officers. Every neighborhood is asking for more officers on the beat, more foot patrols. But my number one priority is to make sure we have the ability to respond quickly to a crime in any part of this district. Sometimes I only have half the force available to me at any one time—officers are either out injured, or they're on maternity leave, whatever. If I only have a handful at roll-call I can't put two officers on foot in this area, because if we get a call all the way over on Wyckoff [several miles away] there's no way they can get over there as fast as a squad car."

But it wasn't just cars that were outdated or insufficient in number. The bulk of the paperwork was still being done by hand. There were very few computers and no money available in the police budget to buy more. Indeed, there was no attempt by the top brass at CCPD to develop a strategy to show how and why this new technology would bring efficiency and more time for actual law enforcement. Officers complained that even though they might want to clear a particular street corner of drug dealers, they were reluctant to do so when the arrestee had often paid the fine for "incommoding" and was back on the street before the paperwork had been completed.

Teams of foot patrolmen were sometimes sent out with one walkie-talkie between them. This could be extremely dangerous if they had to pursue a suspect on foot and became separated. Officers complained that Cornet was "in the Stone Age" compared to other cities as far as crime-fighting technology was concerned. In cities on the West Coast for example, they had portable machines which could take fingerprints on the scene and immediately identify suspects with prior criminal records. Cornet officers said there were times when they could not serve a warrant because they could not prove the person standing before them was the one they sought; the suspect, of course, denied being that person.

Resources were especially lacking for the kind of long-term investigation needed to do serious damage to a drug operation. First, there was only

a handful of undercover officers available. With so many citizens complaining about street-corner drug trafficking, the police department decided that the high-visibility buy-bust was necessary politically even if it was futile from a law enforcement perspective. At least the police could say that they had made "x" number of raids in a given locality. They could not be accused of "doing nothing." Because CCPD lacked the surveillance equipment necessary for a long-term investigation, officers even used their own video cameras to do police work.

Police officers were frustrated and cynical and so was the public, which felt besieged and frightened not only by the violent criminals but also by corrupt police officers. In 1990 there was an unprecedented number of indictments of police officers, for crimes which included drug distribution, robbery and murder. The increase in criminal cops was attributed to a confluence of factors. First, hundreds of officers were hired in the 1980s without any background check; not surprisingly, many had criminal records. Moreover, a policy change during that time meant that a prior criminal record was no longer reason for disqualification for police work. In addition, both the length of training and its content had been reduced significantly. The combination of youth and poor training was at the root of many of the department's problems. And at the same time that there was an influx of young, inexperienced officers, many of the department's most experienced people were retiring. There weren't enough senior officers around who could be partnered with new recruits. The net result was low morale on the force and a public that distrusted the police and believed it to be thoroughly corrupt. The subject of 'bad cops' was one of the first raised in the meeting with McDougal.

"We got a cop patrols right in this neighborhood, and I swear there's something 'funny' about him," said Leonard Francis. "Just the other day I saw him over here on his private time—it must of been, because he wasn't wearing his uniform—but he was talkin' to those drug boys. In broad daylight. You can't tell me somethin' isn't goin' on with that. You scared to even trust the police 'cause half of 'em are in on all this mess." Several people agreed.

"Make no mistake," McDougal stated, "there are some bad cops out there. If you have some information please give it to us and we'll have our Special Investigations Unit look into it." Francis noted silently that he wasn't going to give any information to anybody, and end up dead in an alley.

McDougal continued, "but one thing that I really want to stress in this meeting is that we need the help of the community. The police can't be everywhere at once, and the only way we can start to solve these problems is if the law-abiding citizens help us. We need your help. If you have information, please let us know about it. Maybe you see certain cars con-

stantly stopping at a particular house. Well, you can write down the tag number, the date, the time—pass that information on to our Vice Unit. The more information we have, the better the evidence we can get to lock these guys up."

A man in the back of the room, Dennis Pettibone, stood and pointed at McDougal angrily. "I can't believe you're comin' in here and tellin' us to snitch on our own people. People in the community should refuse to get involved with cops. If you-all were serious about stopping this drug problem, you could do it. Black people don't own the planes that bring the drugs into this country. Black people don't own the gun shops in Virginia where all these weapons are coming from. My personal opinion is that this society wants black people out here sellin' drugs and killin' each other over a piece of rock. —And if we don't kill each other off, then the police are right there to do it for us. You askin' us to help you lock up more black men, more young black men? No, I don't think so."

Another resident entered the fray. "Now wait a minute Denny, I can understand what you're sayin' about the police brutality and all, but one thing you're forgetting is that these black people are out here killing other black people." The observation was correct: 93 percent of black victims were killed by other black people; the rate for whites killing other whites was 86 percent.

"I agree with you that if all this drug abuse and murder was happening to whites then they would have solved it yesterday."

"You got that right," said Pettibone.

"It's just like with the AIDS thing: as long as it was only killing off gay people and people in Africa and poor blacks and Puerto Ricans here, nobody cared. But now that you got these celebrities and other famous people dying, all of a sudden everybody's got all this sympathy for AIDS people.

"But I do want all this foolishness in the community to stop, and I'm willing to get involved. But the only thing is I don't want to give any evidence no matter what I see, because I'm scared of retaliation."

Getting tangible evidence and witnesses was a major problem in the prosecution of drug trafficking and other crimes. A review of the cases dismissed after an initial decision to prosecute showed that an exceedingly high proportion were dropped because of evidence or witness problems. (See Exhibits 13 and 14.) For example, in 1974 only 1% of victimless crimes including drug trafficking were dismissed for evidence problems, and 2% for witness problems. By 1990 26% of victimless crimes were being dismissed for evidence-related reasons, and 24% for witness-related reasons. These trends held for robbery and other violent crimes.

McDougal conceded, however, that there was good reason for citizens to be wary of testifying in drug cases. The intimidation and murder of

Exhibit 13:

CASES DISMISSED DUE TO EVIDENCE PROBLEMS*

|

Type of Crime |

1974 |

1990 |

|

Robbery |

2% |

19% |

|

Other Violent (Homicide, Rape, Assault) |

1% |

36% |

|

Victimless (Drugs, Gambling, Sex Offenses |

1% |

26% |

|

* Cases dismissed after initial acceptance by prosecutor. |

||

Exhibit 14:

CASES DISMISSED DUE TO WITNESS PROBLEMS*

|

Type of Crime |

1974 |

1990 |

|

|

Robbery |

20% |

43% |

|

|

Other Violent (Homicide, Rape, Assault) |

33% |

58% |

|

|

Victimless (Drugs, Gambling, Sex Offenses |

2% |

24% |

|

|

* Cases dismissed after initial acceptance by prosecutor. |

|||

witnesses was now common. "I can understand how the people in this neighborhood would be afraid to come forward with information," he told those at the meeting. "I don't know exactly how to fix the problem but I know there has got to be some remedy available."

A woman in the front row spoke up. "You know, it's not just in these drug cases that people don't think the police do any good, or can protect you. The woman who used to live next door to me was beaten for years by her husband. The police would come but they wouldn't do anything—just tell him to go out and cool off or stupid things like that. She couldn't get a restraining order or anything. She eventually had to move because the man would not stay away. Lord, I remember that man would beat her something terrible and the police wouldn't do anything about it. I mean, you may not know how to protect people against drug dealers, but you should be able to protect a woman against somebody right in her own home who is trying to hurt her or kill her."

"You're right ma'am, the laws used to be really inadequate. But now

we have special procedures for domestic violence cases. We don't even necessarily have to have the woman herself sign a complaint against him. If the officer sees that the woman is bruised, and the house is all torn up—he can make the arrest based on his own judgment."

Although their meeting with Captain McDougal did not satisfy Lydia Davis and her neighbors completely, some good did result from it. They got to know one of the officers on a personal basis and were willing to provide information on suspicious vehicles and other goings-on in the neighborhood. This led to several busts and the closing of three crack houses. Once residents saw that there would be confidentiality and visible results they were even more willing to work with the police. They began talking seriously about starting a neighborhood patrol group.

Burnett and Silver felt they had learned a great deal at the meeting, and were anxious to have other Task Force members hear some of the arguments that had been made. They asked Lydia Davis and some of her neighbors if they would attend the public hearings once they got underway. They were eager to do so.

"It's about time the Mayor started paying attention," said Martha Heywood. "It's just too bad they always wait for something bad to happen."