5

A Redesigned Census

Chapters 2 and 3 identify two central problems with the current approach to taking the decennial census: costs have escalated rapidly while accuracy, as measured by both the overall and the differential undercount, has decreased. In this chapter, the panel identifies and makes recommendations for reducing the cost and improving the accuracy of the census.

Our overarching recommendation for a substantially redesigned census follows from three central conclusions:

-

The massive employment of enumerators, in an attempt to count every last household that fails to return a census mail questionnaire, cannot produce an accurate and cost-effective census. Long before that objective could be achieved, diminishing returns set in, so that only small gains are achieved at great budgetary cost.

-

After a reasonable and cost-effective effort to make a physical count of the population, the use of sample surveys and statistical estimation techniques to complete the count can produce greater accuracy than the traditional approach—especially with respect to the critical problem of differential undercount. We consider the use of statistical estimation to supplement the physical count to be the best possible realization of the actual enumeration required by the Constitution.

-

Once it is accepted that statistical estimation can be used with accuracy to complete the counting process, substantial cost savings can be achieved by redesigning the census process from the ground up to take advantage of this change.

As background to our detailed recommendations, this chapter first outlines two approaches to taking the decennial census: the traditional census and a redesigned census. The chapter then discusses the major components of the second approach, identifies the critical choices that will have to be made in designing such an approach, and makes specific recommendations for the basic strategy that should be used. The chapter then considers and recommends a number of additional measures that could improve the accuracy and lower the costs of the next census. Finally, it proposes a fundamental review and reengineering of all census procedures to take advantage of the full cost-reducing potential of the new approach.

TWO APPROACHES TO COUNTING THE POPULATION

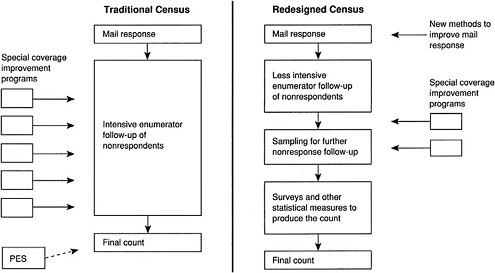

The traditional approach, used in the 1990 census, relies completely on intensive efforts to achieve a direct count (physical enumeration) of the entire population. The alternative approach, an integrated combination of enumeration and estimation, also starts with physical enumeration, but completes the count with statistical sampling and survey techniques. Figure 5.1 is a schematic presentation of the two approaches.

The enumerative approach, labeled the traditional census on the left-hand side of the figure, begins with the construction of an address register, including elaborate procedures to improve its comprehensiveness.1 Census forms are then mailed to a comprehensive list of residential addresses, with instructions to mail back the completed questionnaire. Not all households return their completed mail questionnaire within a reasonable period of time. For households that do not respond to the mail questionnaire (35 percent of all housing units and 26 percent of all occupied housing units in 1990), census enumerators undertake an intensive follow-up effort to determine whether the unit is occupied and, if so, to contact the household and elicit responses. Repeat visits are made, administrative records are sometimes examined, and special programs to contact particular groups (e.g., homeless people) are carried out. This process is continued for an extended period of time to enumerate physically every household and all the people in every household.

Extensive special programs have been directed toward coverage improvement in recent censuses. These programs are expensive, both in absolute terms and often in terms of the cost per person or housing unit. Special coverage improvement programs have included:

-

movers check—a follow-up of people reporting a change of address to the U.S. Postal Service during the census enumeration period;

-

prelist recanvass—in prelist areas, a recheck of the address list during the second stage of follow-up;

-

vacant/delete check—a recheck in the field of housing units originally

-

classified as vacant or as ''delete" because they were not residential—this was done on a sample basis in 1970 and for all units in 1980 and 1990;

-

causal count—a campaign to find persons missed from the census by contacting community organizations or visiting places frequented by transients; and

-

nonhousehold sources program—matching administrative records to census lists for selected areas.

Citro and Cohen (1985: Tables 5.2 and 5.3) present cost and effectiveness data on these programs for the 1970 and 1980 censuses.

The results from the mail response, enumerator follow-up, and intensive special coverage improvement efforts are combined to produce the actual enumeration of the U.S. population—both as a whole and for subdivisions down to the block level.

Even though a highly labor-intensive effort is undertaken to obtain a completed questionnaire for every household, the resulting estimates contain errors. As we noted in Chapter 2, the 1990 census produced a net undercount of 1.8 percent for the nation as a whole. This net undercount included overcounting in some areas and among some groups, which was more than offset by undercounting among other areas and groups. Blacks and Hispanics, Asian and Pacific Islanders, American Indians and Native Alaskans, renters, and residents of poor inner-city areas were undercounted by larger percentages than the nation as a whole. To detect these errors, a highly intensive survey of a representative sample of areas throughout the country was conducted after the physical enumeration efforts ceased.

In 1990, on the basis of a sample of areas, the difference between the census count and the count produced by the Post-Enumeration Survey (PES) was used to calculate statistical estimates—by area, racial group, and other relevant demographic characteristics—of the net undercount or overcount contained in the census data. After a series of legal battles, it was decided not to use the results of the PES to correct the initial 1990 census count, either nationally or in smaller areas. The enumerative count remained the official 1990 census estimate, used to make reapportionment and redistricting decisions and for other purposes.

This enumerative approach has been subject to the two basic failings discussed in Chapters 2 and 3: high and rapidly rising costs and high differential undercount. We therefore propose for the redesigned census the approach of statistical estimation to correct the enumerative count, not as a simple add-on to the traditional census but as a completely new point of departure. By so doing we address not only the issue of differential undercount (which could have been done in 1990), but also the issue of high costs. Statistical estimation, regarded not as an add-on as was done in 1990 but as an integrated aspect of census taking, allows a fundamental reengineering of the entire census design.

The alternative approach, labeled the redesigned census on the right-hand

side of Figure 5.1, combines an initial stage of direct counting (physical enumeration) with various statistical estimation techniques. Correctly designed, this approach involves more than a simple layering of a postenumeration survey on top of a traditional labor-intensive physical enumerative design. Rather, every stage of the census, including the initial stage of physical enumeration, is designed with the awareness that statistical sampling and estimation are available to remedy deficiencies and improve coverage. This approach permits the elimination of all operations that add relatively little to accuracy but have high unit costs. Indeed, it permits the reengineering of the entire traditional phase of the census with this guiding principle. Moreover, this approach produces an integrated single-number census, rather than the confusing and politically divisive result of the 1990 process, in which the enumeration produced an official census count, but the PES produced another set of numbers.

The redesigned census starts, just as in the first approach, with the mailing of census forms to an address list. The redesigned census includes new methods to improve the mail response. The new methods—including respondent-friendly questionnaires, Spanish-language questionnaires for Hispanic areas, use of reminder postcards, and motivational messages to increase mail return—will decrease costs by reducing the need for personal nonresponse follow-up. A substantial program to track down those who do not respond by the designated date is carried out using census enumerators, but with significantly less intensity and of shorter duration than in the first approach. The follow-up includes a judicious combination of a second mailing to nonrespondents, follow-up by telephone, and personal visit. The follow-up, area by area, is designed with four guiding principles: (1) a reasonable attempt should be made to follow up all nonresponding households; (2) all areas should have as an objective a reasonably high response rate; (3) follow-up should be terminated after a reasonable attempt (e.g., several calls to the same household rather than as many as six calls, as was done in the 1990 census); and (4) the entire duration of field operations should be limited (e.g., 4-5 months rather than 9 to 12 months, as was done in the 1990 census). The use of these physical enumerative techniques is truncated after a reasonable effort has been made (see below for a discussion of the criteria for when to truncate).

Once the follow-up is truncated, intensive surveys are taken of some sample fraction (e.g., one in four, or some fraction) of nonrespondents to get the full range of census information from the nonrespondents in those areas. On the basis of these results, statistical techniques are used to estimate, for all nonrespondents, what has to be added to the mail responses and the truncated follow-up to arrive at what the traditional census count would have been had the follow-up effort expended on the sample been implemented for all nonresponding households. The use of sampling techniques to follow up nonrespondents is called sampling for nonresponse follow-up.

The less intensive the 100 percent follow-up and the smaller the sampling

fraction, the larger the cost saving but the greater the probability of errors in the count for small geographical areas. A highly accurate count for the nation as a whole could be achieved with a modest degree of physical enumeration of households and a relatively small sampling fraction. But the possibilities of substantial sampling error in any given small area, which would result in either an overestimate or underestimate of the count for that area, would be high. More intensive 100 percent follow-up and higher sampling fractions would raise costs but reduce the spread of errors in small areas. It should be noted, however, that in the traditional approach, with its effort at full physical enumeration, the range of errors in the count for small areas is still substantial.

Independent of sampling for nonresponse, a further survey is taken of all households in a sample of areas to complete the census process by providing estimates of those people who were missed by previous operations. (These two important roles for the use of sampling are explained further in the box on page 81, which is based on Steffey and Bradburn, 1994.) Unlike the traditional census, in which a PES survey is taken to evaluate the final count, the redesigned census would have an integrated coverage measurement survey for the purpose of estimating the number and characteristics of those missed by the prior stages of the census.2 These are the people missed by all traditional census approaches (see Chapter 2). Overcounting, which is also detected by the PES, could also be taken into account by a coverage measurement survey. In addition, information on birth, death, and immigration might be used to check or supplement the surveys. It is this final count that is published as the official population count of the United States, for the nation, for all geographic areas, and for all the various demographic characteristics of the population.

There are various schemes for exactly how these various elements should be combined and what emphasis should be placed on each. But they would all substitute some degree of statistical estimation for the expensive 1990 effort to try to count by physically enumerating—with incomplete success—every last person. In spite of several decades of attempts to improve population coverage through direct enumeration, inequities continue to exist in the census undercount by race and for geographic areas. Statistical methods to detect these inequities now exist that are feasible for use in the 2000 census.

We endorse the goal of producing the best population census by counting, assignment (allocating households and persons based on good evidence—see below), and statistical estimation. In a new census environment whose last steps involve statistical estimation, the initial phases of the census would be constructed in such a way that every person would have an opportunity to be physically counted, and the Census Bureau would make a good-faith effort to count physically every person through the construction of an accurate and complete mailing list, the use of mail questionnaires, and reasonable efforts to follow-up all nonrespondent households. Following attempts to physically enumerate nonrespondents to the mail questionnaire, first through 100 percent follow-up and

|

The Roles of Sampling in the Census Bureau's One-Number Census In 1990, the official census figures were based on a census process that consisted of three basic steps: (1) constructing a list of addresses, (2) obtaining responses that could be linked to the address list, and (3) following up to obtain responses from those initially missed. In addition, a coverage measurement process was designed to estimate the size of the population that was missed in previous steps of the census process. Two sets of population totals were produced, with and without corrections based on coverage measurement, and an ex post facto decision was made about whether to accept the corrected totals. This "adjustment" decision proved to be controversial because it occurred in a highly politicized environment in which interested parties perceived themselves as winners or losers, depending on which set of numbers was chosen. For the 2000 census, the Census Bureau has proposed the concept of a "one-number census," one that will provide ''the best possible single set of results by legal deadlines, … based on an appropriate combination of counting, assignment, and statistical techniques" (Miskura, 1993). In the Census Bureau's definition, counting refers to all methods for direct contact with respondents, including mail questionnaires, personal visits, and telephone calls. Assignment refers to the use of information from administrative records to add people to the count for a specific geographic location without field verification. Statistical techniques for estimation include imputation procedures, sampling during follow-up of nonrespondents, and methods for measuring census coverage. These three components of a one-number census are designed to complement one another. In particular, the results from coverage measurement will be fully integrated into the official census estimates (Miskura, 1993). Sampling will be used in the new census process in two distinct ways. The first is in nonresponse follow-up. After initial contact and follow-up activities, a sample of households or blocks containing households that did not respond are selected for further follow-up. Estimates, based on the sample, are made of the numbers and characteristics of those who would have responded to the follow-up had it been conducted on the entire population. This use of sampling is proposed primarily to reduce costs by reducing the use of expensive follow-up procedures. It has other advantages too: it can reduce the time needed for the follow-up process, thereby allowing more time for coverage measurement. And, although it contributes to variability through sampling error, it can reduce other kinds of errors. The second way in which sampling will be used in the one-number census is in coverage measurement. A sample survey is conducted from which estimates are made of the numbers and characteristics of those not counted in previous steps of the census process, including those who are not accounted for in the nonresponse follow-up step. This use of sampling is designed to improve the accuracy of the census. In 1990, sampling was used in a coverage measurement process (See Figure 5.3) for evaluation purposes and for possible use as a basis for official population estimates, with a decision on the latter deferred until after the results of the sample were examined. The previous steps of the census process were designed to be used as the basis for reported census figures independently of the coverage |

|

measurement process. In the proposed one-number census, coverage measurement is conceived as an essential part of census-taking and not just as an evaluation of other census operations. In particular, it is not regarded as a method of producing a second set of population estimates that competes with the population estimates obtained without its use. Coverage measurement, which includes sampling, statistical estimation based on the sampling, and statistical modeling, will be integrated with the other census-taking operations. Hence, this phase of census-taking is called integrated coverage measurement. The fundamental innovation of a one-number census is that an appropriate methodology for integrated coverage measurement is established before the census is carried out, with the recognition that results at previous steps cannot be regarded on scientific grounds as viable alternatives to the final, best set of official population estimates. It also allows for more optimal design of other census operations. Source: Adapted from Steffey and Bradburn (1994). |

then through sampling, the census would use survey-based statistical estimation to complete the final official population count.

As mentioned earlier, there are several additional specific ways to achieve cost savings in the future integrated single-number census, including: respondent-friendly questionnaires and other improved procedures for increasing mail response rates, truncating census operations earlier to minimize the lengthy work period for district offices and census field staff, and increased use of U.S. Postal Service employees for such operations as vacancy checks of housing units. But, most important, statistical estimation at the final stage of census operations and abandonment of the target of physically counting everyone permit a complete reengineering of the basic census operation in light of the new census context. Thus, numerous expensive coverage improvement operations used in the 1990 census can be reviewed with an eye to elimination as unnecessary (compare the left and right sides of Figure 5.1).

As a guide to the exposition below, we note that there are four key stages in the redesigned census (see the right-hand side of Figure 5.1) leading to the final official population count: mail response, enumerator follow-up, sampling for further nonresponse follow-up, and a survey together with other statistical estimation techniques to complete the count. Ways to improve the mail response are described later in a section entitled "Improve Response Rates." Issues relating to enumerator follow-up are covered in several sections of the next major section, in which we discuss decreasing the intensity of nonresponse follow-up and truncation of enumeration after a reasonable effort. After describing a reasonable effort at enumerator follow-up, we discuss the role for "Sampling for Nonresponse Follow-Up" in a separate section. We describe the role of an integrated coverage survey in a later section entitled "Survey-Based Methods to

Complete the Count." With the use of statistical estimation (the integrated coverage measurement survey) built into the redesigned census, the entire process of census enumeration needs to be reengineered. Under the new procedures of a redesigned census, there would be a reduction of special coverage programs that are no longer cost-effective. The reengineered census, along with a review of some specific census operations, is presented below in a major section entitled "A Reengineered Census."

Census Bureau Plans

The panel would like to recognize that the Census Bureau is actively working on plans and conducting research on much of what is described in this chapter. Much of the material reported here is based on ongoing census research. The Census Bureau, however, has not yet prepared a specific proposal for the 2000 census design. Census Bureau plans for the 2000 census will be informed by results of census tests in 1995.

The Census Bureau will carry out a major test of census design options at four sites in 1995. The test will examine the following methods:

-

Sampling for the follow-up of nonrespondents to the mail questionnaire.

-

Statistical methods to estimate separately the number and characteristics of people missed because their housing unit was missed, people missed within enumerated housing units, and people who were erroneously enumerated.

-

Coverage questions for a complete listing of household members.

-

Mailout of Spanish-language questionnaires.

-

Target methods to count historically undercounted populations.

-

Counting persons with no usual residence.

-

Making census questionnaires more widely available by placing unaddressed questionnaires in accessible locations (e.g., stores and post offices).

-

Respondent-friendly questionnaire design and a full mail strategy for improved mail response.

-

Telephone response as a follow-up option.

-

Real-time automated matching for record linkage.

-

Using the U.S. Postal Service to identify vacant and nonexistent housing units.

-

Electronic imaging to scan respondent-friendly census forms and to capture data.

-

Cooperating with the U.S. Postal Service for the continuous updating of a national housing address file.

-

Collecting long form-type data using matrix sample forms (two or more sample forms with only a subset of the questions).

Results from the 1995 census tests, and continued tests from 1996 to 1998, will be important for operational plans for the 2000 census. At the moment, the Bureau of the Census (1993a) proposes to conduct a "one-number census" that will use statistical methods integrated into the census process. Except for a one-number census, the Census Bureau has not made a formal commitment to the specific recommendations that the panel makes in this chapter for a redesigned census. Moreover, we propose a much more extensive redesign of the 2000 census.

In recent congressional testimony, Harry Scarr, the acting director of the Bureau of the Census, stated that the 1995 census tests would provide important results for planning the 2000 census, including: (1) detailed evaluations of sampling for nonresponse follow-up and sampling as part of statistical estimation for census coverage, (2) operational and cost information for new sampling and estimation methods, and (3) evaluation of the effect of new methods on errors in census data (Scarr, 1994). The 1995 census test will also examine the quality of the census address lists, in a cooperative venture in which U.S. Postal Service delivery addresses are used

Legal Issues of Statistical Estimation

As part of its examination of alternative methods for counting the population, the panel examined the legal issues for the greater use of statistical estimation. The requirement for effort at complete enumeration does not necessarily rule out the increased use of sampling as part of the census. Sampling has several potential uses that are worth inspection for increased use in future censuses.

It is important to distinguish among three potential uses of sampling in the census. The first is to estimate the number and characteristics of people who were not found even after attempts at nonresponse follow-up and people who were counted more than once or should not have been counted. This use of sampling to complete the count is referred to as an integrated coverage measurement survey in Figure 5.1. The second broad use of sampling in a census is sampling within the actual process of physical enumeration. The number of nonresponding households is known, so the purpose of sampling the nonrespondents is to estimate their characteristics. The third broad use of sampling is to take a sample of the population at the beginning of the census. In such a "sample" census, no attempt would be made to enumerate every person. The panel discusses this option in Chapter 4.

In the panel's judgment, the spirit of the constitutional, legislative, and judicial history regarding enumeration is compatible with the use of sampling as part of the census process, so long as that process includes a reasonable effort to reach all inhabitants. Specifically, we believe that census designs that use sampling for the follow-up stage of census operations (after an initial reasonable

attempt has been made to collect a census questionnaire from everyone) and for the final stage of census operations for an estimate of the population not counted by physical enumeration (using an integrated coverage measurement survey for statistical estimation to complete the count) would meet both substantive and legislative requirements for reapportionment. Such designs also have the potential to increase census accuracy and reduce census costs (see Appendix C for a discussion of the legislative requirements for the census).

Precedents from previous censuses exist for the use of sampling. Several court cases have explicitly upheld the constitutionality of an adjustment based on a survey (such as the PES in the 1990 census), citing the importance of having data as accurate as possible for reapportionment and redistricting.3 The question of the legality of sampling for follow-up for nonresponse has never been explicitly raised in the courts; however, language used in the relevant court cases would clearly seem to be consistent with its use.

Court decisions on census issues have deferred to the Census Bureau on technical issues. The panel's review of legal issues in Appendix C does not provide grounds for concern that courts will question the expanded use of sampling in the census (i.e., sampling for nonresponse follow-up or a sample survey to estimate the number and characteristics of people missed in the physical enumeration). Courts have accepted the use of sampling in prior censuses, and we propose a more extensive use of sampling in the 2000 census. After a review of past court decisions, the panel expects that the courts will continue to accept the technical decisions made by Census Bureau staff, including the use of sampling in a good-faith effort to count the population, in a redesigned census.

BASIC ELEMENTS OF A NEW CENSUS DESIGN

The conventional mailout/mailback census operation that the Census Bureau has conducted for the 1970, 1980, and 1990 census can schematically be thought of as involving five stages: (1) the development and checking of a master address list prior to the census, (2) the physical enumeration of the population through the mailing of the census questionnaires several days before April 1 (Census Day) and the collection of the returned questionnaires, (3) the follow-up of those housing units that do not return the census questionnaire, (4) a variety of coverage improvement activities, and (5) checks on the census coverage. One critical area that would be affected by our proposal is point (3).

Decreasing the Intensity of Nonresponse Follow-Up

In practice, the follow-up of all nonrespondents is a costly procedure—the precise magnitude of the cost depends on the intensity of the effort. Follow-up of nonrespondents was directed by each of the 449 district offices in the 1990 census. Follow-up began about three weeks after Census Day, with enumerators

directed to contact households who had not yet returned their questionnaires. At the end, as a last resort, enumerators were directed to ask neighbors, landlords, or others who might be familiar with the household occupants to provide basic demographic and housing information.

Somewhat different procedures were followed in a small number of areas either in which mail addresses did not exist or in which it would not have been feasible to rely on mail questionnaires for the census. For areas lacking mail addresses—primarily rural areas with central postal mailboxes—census staff used a "list-enumerate" procedure. This procedure involved census staff's identifying each of the housing units in a geographic area, listing the units with an identifiable location (e.g., the three-story house on the northwest corner of the intersection of Belnap Road and County Road Five), and then directly enumerating the occupants. The list-enumerate procedure was also used in some inner-city areas for which the mail return rates had been very low and for which the population coverage had been poor under the traditional mailout/mailback approach.

Not only is there a direct expense to follow up each nonresponding household with the intensity employed in the 1990 census, but there are also substantial additional infrastructure costs when the duration of follow-up is prolonged.4 There has been a gradual increase in the length of time that census district offices remain open during the census, which increases costs for rental of the physical space and equipment and boosts the personnel costs for all district office employees. For the 1960 census, district offices were open for 3 to 6 months; for the 1970 census, offices were open for 4 to 6 months; for the 1980 census—coinciding with the large unit cost increases (discussed in Chapter 3)—offices were open for 6 to 9 months; finally, for the 1990 census, as a result of earlier opening to improve the address listing and lengthened follow-up of nonrespondent households, district offices were open for 9 to 12 months.

Sampling for Nonresponse Follow-Up

Reducing the intensity of the 100 percent follow-up of nonrespondents and a subsequent sample-based follow-up of the remaining nonrespondents can maintain an acceptable level of data quality while yielding major cost savings. A reduced effort on highly labor-intensive nonresponse follow-up, using less expensive telephone follow-up and having many fewer personal visits, would result in substantial cost savings.

After a reasonable effort at 100 percent follow-up, a sample of the remaining nonrespondents would be followed up intensively, perhaps with attempts to contact one of every three or four nonrespondents.5 The nonresponse follow-up would use the same census enumerators who worked on the initial census follow-up, although fewer enumerators would be needed for follow-up on a sample basis. This sample would be used to estimate the fraction of units vacant and the characteristics of all remaining nonrespondents. The sample might be based on

areas or on households: one of four census blocks in selected small areas or one of every four households might be selected. More intensive effort could be directed to obtaining information from these sampled nonrespondents, while still reducing aggregate follow-up costs. The sampled nonrespondents would be used to provide estimates for the other nonrespondents, assuming, as in other survey research, that they are a reasonable sample of all nonrespondents.

Truncation of Enumeration After a Reasonable Effort

Reduced intensity of physical enumeration, which we label truncation, when combined with statistical estimation techniques to complete the count, far from degrading the overall quality of the census, will improve the accuracy of the final count of the nation as a whole, for large demographic groups, and for populous areas. But in choosing the extent and the specific pattern by which the intensity of physical enumeration is reduced, two issues have to be considered. First, greater reliance on statistical estimation will increase the variability of the count in small areas. Second, excessively early truncation of physical enumeration would mean that only a modest fraction of the population would be directly counted in some hard-to-enumerate areas, and such truncation could lead both to unfavorable public reactions and to an erosion of the compliance with the mandatory nature of the census. It is important, therefore, to design a set of criteria for choosing the degree and methods of truncation that would minimize these problems, while still achieving significant cost-saving and improving the quality of the overall census results.

If the census data collection period is shortened or truncated, significant savings would result from the early curtailment of field operations. A truncated census would involve the closing of hundreds of district offices, with savings in staff and overhead expenses associated with the prolonged continuation of data collection.

It should be noted that consideration of a truncated census assumes some use of statistical estimation in order to produce the final census count. It makes no sense to curtail census operations when the counting of the population is not complete unless there are plans to conduct statistical surveys for completing the count as well as estimating the characteristics of nonrespondents.

A truncated census design should be considered in terms of two factors, completion rates (the percentage of households counted before 100 percent follow-up ceases and sampling begins) and public perceptions of the attempt to count everyone: the sooner that sampling for nonresponse follow-up begins, the greater the cost savings but the greater the risk of public perception that "not everyone was counted." As noted above, the panel's concern with a reasonable period of enumerator-intensive follow-up before moving to sampling for follow-up is not a worry about the quality of population coverage. Rather, the panel is concerned that an excessively early truncation of census follow-up activities

may be perceived by the public as not trying to count the entire population. This, in turn, could lower mail response rates, raise costs, and lower the quality of the census for small areas. The panel believes that it is important to maintain both the actuality and the public perception that the census is mandatory and that the census makes the attempt to count every person. We comment on this issue at the end of this chapter.

Alternative Techniques of Truncation

There are three possible ways to truncate full-scale direct enumeration after a reasonable effort: (1) after a given date, (2) after a given fraction of the population has been counted in an area, and (3) after a given amount of resources for enumeration has been used in each area. In practice, the most cost-efficient and politically feasible technique for truncation would be some combination of these or similar criteria.

In an approach using truncation after a given date, labor-intensive follow-up would be undertaken for a specified period of time, which would be the same for all areas of the country. Various dates for truncating census operations are possible. The problem, of course, is that with reasonable truncation dates, there would be wide variations in completion rates across geographic areas. Three possible dates—April 21, June 2, and June 30—are useful for illustration because in 1990 about two-thirds of census questionnaires were completed by April 21, about 90 percent by June 2, and almost all by June 30.

An alternative technique for truncation is to cease 100 percent follow-up operations in an area after a given fraction of the population has been counted. For example, if a goal of 90 percent enumeration is set as a goal for every area, then some areas with very high rates of return for the mail questionnaire might have personal visits for nonresponse follow-up only on a sample basis. Areas with low mail return rates would have 100 percent nonresponse follow-up until the 90 percent coverage goal is achieved. Attempting to achieve a minimum count implies a longer period of physical enumeration in low-response areas. Yet, even after prolonged attempts to count 90 percent of the housing units in an area, there may be some low-response areas that do not reach the goal. In those cases, it might be wise to consider the use of a given date for truncation.

Another technique for truncation would be to spend a set amount of resources for each estimated nonrespondent, by areas. Census staff would estimate prior to the census the probable size of the nonrespondent population, using results from the 1995 and other census tests, and allocate funds by areas, with roughly the same amount of money per nonrespondent. Areas with high mail return rates (and a lower number of nonrespondents) would receive fewer funds than areas with low mail return rates.

The optimal strategy is likely to involve a combination of all three techniques. Experience with the 1995 census tests and more detailed planning by

census staff will be needed to arrive at a combined strategy that is cost-efficient. A politically feasible strategy would also need to take into account the fact that some nonresponse follow-up would be desirable for all areas, regardless of how successful the response to the mail questionnaire, and that low-response areas should see a reasonable intensity of nonresponse follow-up rather than see physical enumeration terminate at a set date.

What Determines a Reasonable Effort

A critical issue for truncation of intensive 100 percent nonresponse follow-up is the determination of what constitutes a reasonable effort. The discussion above concluded that a redesigned census should involve a combination of truncation after a given date, after a given fraction of the population has been counted, and after a given amount of resources has been used. The objectives of the 100 percent follow-up should be: to achieve a minimum response rate, to terminate follow-up after reasonable attempts to contact nonrespondents, and to limit the duration of follow-up activity.

The optimal combination of procedures for an actual census requires information on each of the truncation approaches, separately and in combination. The panel has considered all various alternative strategies, but statistical information available to the panel has been limited to truncation by date. The panel searched for information to document other ways to truncate 100 percent follow-up but learned that data from the 1990 census provide only selected information. Analysis of data from the 1995 census tests and perhaps further testing are required to provide sufficient information for a final strategy.

The panel can illustrate the effects of truncation for the one approach for which data are available: truncation by date. Very early truncation would produce the most savings, but in many hard-to-enumerate areas early truncation would leave a large percentage of the estimated population uncounted. A large percentage of uncounted people has two serious effects. One effect is on statistical estimation: the use of survey-based methods to complete the census count is more accurate when a relatively high percentage of the population is counted through direct enumeration. A redesigned census should therefore aim to count a reasonably high proportion of the population through the mail questionnaire and nonrespondent follow-up.

The second serious effect of very early truncation is the problem of perception and misunderstanding, noted above. Early truncation in hard-to-enumerate areas may be seen as a lack of interest in achieving an accurate count in these areas, even though survey methods would be used to produce the final census count. Some residents of hard-to-enumerate areas may believe that the census is not mandatory, thereby further complicating efforts to achieve an accurate count.

Completion Rates. Considerable variation would exist for the completion rates

for a truncated census (before a sample of nonrespondents is taken) for geographic areas and for major racial groups. Table 5.1 presents coverage estimates in the 1990 census for various demographic groups. This table shows the percentage of population counted, for three dates and a nontruncated census, relative to the final PES population estimate. On April 21, three weeks after Census Day, most of the mail questionnaires were returned but little nonresponse follow-up occurred. Over two-thirds of the national population was counted by April 21, although there were substantial variations among major race and Hispanic groups: only one-half of the American Indians were counted but over 70 percent of the nonblack (primarily white) population was counted. On June 2, after about six weeks of 100 percent nonresponse follow-up, the national population was 89 percent counted. A gap in coverage rates persisted, however, with an 11 percentage point difference between blacks (79 percent coverage) and nonblacks (90 percent coverage). By June 30, as the census enumeration drew to a close, the national count was relatively complete (relative to the final PES estimate) and the race and Hispanic differences in coverage rates narrowed. In summary, if truncation were applied consistently by date across the nation, there would be substantial differences in coverage rates between race and Hispanic groups.

We can illustrate further what is known from the 1990 census about completion rates that would have occurred if the 1990 census had been truncated at various dates (see Table 5.2). The results are classified by some major census characteristics: list/enumerate areas, urban/rural, and census divisions. This table is based on tabulations from the PES clusters for the 1990 census. Each column shows the proportion of PES clusters with less than 50 percent of the final responses complete. As of April 21, three weeks after Census Day—when there would have been negligible follow-up of nonresponses to the mail questionnaire—16 percent of the PES clusters in the nation still had less than 50 percent of the final responses complete. By June 2, with about 6 weeks of nonresponse follow-up, only 3 percent of the nation's PES clusters still had less than 50 percent of the final responses complete.

There is considerable variation in completion rates by characteristics of PES clusters. The collection of household responses is much slower in clusters with list/enumerate procedures (list/enumerate procedures refer to census operations in which the enumerator personally lists housing units in an area, then distributes census questionnaires to each unit). List/enumerate operations are required in a few areas in which no adequate mailing list can be prepared prior to the census. Most list/enumerate areas are rural areas without individual mailboxes for each housing unit or American Indian lands with scattered housing units. In both rural areas and American Indian lands, census enumerators travel the area to list each housing unit and then enumerate it personally. As shown in the second row of Table 5.2, there was a higher proportion of list/enumerate clusters with less than 50 percent responses complete for the first several weeks of nonresponse

TABLE 5.1 Final PES Estimates and Population Coverage for Truncated Census Counts by PES Coverage Measurement for Major Race and Ethnic Groups, 1990 Census

|

Demographic Group |

April 21 Coverage (Percent) |

June 2 Coverage (Percent) |

June 30 Coverage (Percent) |

Nontruncated Census Coverage (Percent) |

Final PES Estimates (thousands)a |

|

|

Total |

68.7 |

88.5 |

96.3 |

98.4 |

252.713 |

|

|

American Indian |

50.2 |

82.0 |

93.2 |

95.5 |

2.052 |

|

|

Asian and Pacific Islander |

62.7 |

84.0 |

95.1 |

97.7 |

7,447 |

|

|

Black |

53.6 |

78.6 |

92.6 |

95.6 |

31,377 |

|

|

Hispanic |

57.3 |

80.5 |

92.1 |

95.0 |

23,521 |

|

|

Nonblack |

70.8 |

90.0 |

96.8 |

98.8 |

221,336 |

|

|

a The total number of people in each group is based on the final PES estimate. |

||||||

follow-up. After about 6 weeks of nonresponse follow-up, however, the completion rates for low-response clusters were similar for list/enumerate areas and other areas.

There were few substantial differences in the completion rates by date for larger and smaller urban areas and rural areas. Rural areas were affected by a higher proportion of areas requiring list/enumerate procedures. After several weeks of nonresponse follow-up, there were similar levels of clusters with less than 50 percent of final response complete for urban and rural areas.

Regional levels of clusters with less than 50 percent of final responses complete were affected by the requirements for list/enumerate procedures (which affects the New England area, for example) and regional patterns in the tardiness of nonresponse follow-up. There were particularly lengthy follow-up periods on American Indian lands before the response rates were adequate: even after 6 weeks of nonresponse follow-up, 21 percent of the PES clusters still had less than 50 percent of the final responses complete. Several regions—Northeast, Middle Atlantic, South Atlantic, East South Central, and Pacific—also required longer duration of follow-up, compared with the remaining regions, before the proportion of clusters with less than 50 percent of final response complete falls to relative low levels.

TABLE 5.2 Proportion of PES Clusters With Less Than 50 Percent of Final Responses Complete, by Date of Census Operations, 1990 Census

|

Type of PES Cluster |

Sample Size |

April 21 |

May 5 |

May 19 |

June 2 |

June 30 |

|

Total |

4,949 |

.16 |

.11 |

.07 |

.03 |

.00 |

|

List/Enumerate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

359 |

.52 |

.21 |

.06 |

.04 |

.00 |

|

No |

4,590 |

.13 |

.11 |

.07 |

.03 |

.00 |

|

Urban/Rural |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Urban, 250,000+ |

2,153 |

.15 |

.12 |

.08 |

.03 |

.00 |

|

Urban, < 250,000 |

1,730 |

.13 |

.10 |

.06 |

.02 |

.00 |

|

Rural |

1,066 |

.23 |

.12 |

.06 |

.03 |

.00 |

|

Census Divisions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

American Indian |

39 |

.54 |

.41 |

.31 |

.21 |

.00 |

|

Northeast |

297 |

.25 |

.15 |

.07 |

.03 |

.00 |

|

Middle Atlantic |

709 |

.20 |

.15 |

.10 |

.05 |

.00 |

|

South Atlantic |

652 |

.17 |

.14 |

.09 |

.04 |

.00 |

|

East South Central |

514 |

.13 |

.11 |

.08 |

.03 |

.00 |

|

West South Central |

674 |

.11 |

.09 |

.05 |

.01 |

.00 |

|

East North Central |

646 |

.12 |

.08 |

.04 |

.01 |

.00 |

|

West North Central |

420 |

.09 |

.04 |

.02 |

.01 |

.00 |

|

Mountain |

422 |

.19 |

.10 |

.04 |

.02 |

.00 |

|

Pacific |

576 |

.20 |

.14 |

.07 |

.03 |

.00 |

These illustrative results demonstrate the perceptual problems of attempting to use an automatic cutoff date for follow-up census operations. If all nonresponse follow-up were curtailed on May 19, after 4 weeks of follow-up operations, the final responses would be far from complete in a substantial proportion of small areas. This line of reasoning would therefore suggest that truncating census follow-up should, for reasons of cost-efficiency and political feasibility, be determined by a combination of date, percentage complete, and resources expended. We believe that a mixture of criteria for truncation would give a better combination of cost savings and coverage improvement.

We note that a purely truncated census does not seem feasible to the panel. A truncated census, in a pure form, would cease census physical enumeration before everyone had been physically enumerated and eliminate any sampling for follow-up, relying only on a postenumeration survey to estimate the uncounted population. We conclude that such a census would not, by design, represent a good-faith effort to count every resident and so would not meet the minimum legal requirements of a census of the U.S. population. But we conclude that decreasing the intensity of follow-up, in the context of attempting to contact every person, and using sampling to follow up the most difficult-to-locate nonrespondents, does represent a good-faith effort, and it would reduce costs.

Cost Savings. Cost estimates for a redesigned census under various truncation assumptions are available from the Census Bureau only for truncation by date. Further work is needed by census staff to develop the mix of physical enumeration, sample follow-up, and statistical estimation that would represent the best trade-off between the partly competing objectives of maintaining low sampling errors for small-area estimates and reducing census costs. However, the panel did work with Census Bureau staff, using the Bureau's census cost model, to develop a set of illustrative estimates of cost savings that could have been achieved in 1990 through a particularly simple combination of truncation and sampling for nonresponse follow-up. We selected four illustrative dates for truncation and applied them across the country: April 21, May 18, June 2, and June 30. We consider two alternative levels of sampling for nonresponse follow-up for illustration: 50 percent and 25 percent.

We examine illustrative cost savings assuming two levels of mail response rates. One level is the actual mail response rate experienced in the 1990 census (65 percent). The second level is an improved mail response rate that might be experienced in the 2000 census (71 percent). Of course, it is impossible to forecast the mail response rate for the 2000 census, partly because public cooperation with the census has been declining over time and may level off or worsen in the future, but also because the 2000 census should include a number of improvements that would increase mail response rates over what might have been expected if 1990 methods were used.

For these cost estimates, we assume a mail response rate for census questionnaires

that is higher than that experienced for the 1990 census. Based on the Simplified Questionnaire Test (SQT) and the Appeals and Long-Form Experiment (ALFE) (these recent tests are discussed in a later section), it is clear that mail response rates of census questionnaires can be increased with respondent-friendly questionnaires and the treatment of a prenotice letter, reminder postcard, and replacement questionnaire, either separately or in combination. We assume that a short form would have a mail return rate of 77 percent, the observed completion rate for a respondent-friendly short form with the appeal ''Your response is required by law" and a standard confidentiality emphasis (Tortora, 1993). The respondent-friendly long form was not tested with a variety of appeals in the ALFE study. A respondent-friendly long form had an observed completion rate of 56 percent, with no appeal (Tortora, 1993). We assume that the appeal had the same impact on long-form mail response rates as on the tested short-form rates. Because there was a 29 percent decline in the proportion of nonrespondents for the short form with appeal, we make a similar assumption for the long form: we assume that a respondent-friendly long form with an appeal "Your response is required by law" and a standard confidentiality emphasis would have a completion rate of 69 percent. The respondent-friendly forms and the use of an appeal have not been implemented in an actual census environment, in which the mail response rates are likely to be higher. We assume for cost estimates that there is a 5 percent higher overall response rate than in the test results. Combining the assumed mail return rates for the short and long forms, adjusting for vacant housing units, and assuming a higher response in a census environment, we assume an overall mail response rate of 71 percent as an estimate for the 2000 census.

The cost estimates also include the cost of a census evaluation survey, assuming that the cost is similar to the 1990 PES. We assume, therefore, that a truncated census with sampling for nonresponse follow-up would include the costs for a survey to complete the count.

Table 5.3 presents the estimated cost savings for the combination of truncation and sampling for nonresponse follow-up. The top panel shows the savings assuming the 1990 mail response rates; the lower panel shows the savings assuming a higher mail response rate, in the context of what might be expected for a redesigned 2000 census. For a census in which full-scale follow-up activities are terminated at a reasonably early date—around May 18, for example—significant cost savings can be expected—as well as high sampling errors in those areas in which the final count has to be based on sample follow-up to a significant extent. With the 1990 census response rates and 25 percent sampling for nonresponse follow-up, there would be a cost saving of $468 million. With extra efforts for improving the mail response rates (which cost more money), there would be an expected higher mail response rate (see lower panel of the table) and fewer nonrespondents for sampling. The cost saving in this situation, for a

TABLE 5.3 Cost Savings for the Census Long and Short Forms for Combinations of Truncation and Sampling for Nonresponse Follow-Up (in millions of 1990 dollars)

|

Truncation Date |

50 Percent Sampling for Nonresponse Follow-Up |

25 Percent Sampling for Nonresponse Follow-up |

|

Cost Savings With 1990 Census Mail Response Rate of 65 Percent |

||

|

June 30 |

$ 62 |

$ 64 |

|

June 2 |

$ 168 |

$ 224 |

|

May 18 |

$ 324 |

$ 468 |

|

April 21 |

$ 391 |

$ 557 |

|

Cost Savings Assuming Final Mail Response Rate of 71 Percent |

||

|

June 30 |

$ 89 |

$ 92 |

|

June 2 |

$ 183 |

$ 226 |

|

May 18 |

$ 303 |

$ 413 |

|

April 21 |

$ 351 |

$ 482 |

|

Source: Keller (1993a and 1993b); Neece (1993); Pentercs (1993a and 1993b); and Tortora (1993). |

||

census truncated on May 18 and with 25 percent of nonrespondents sampled for follow-up, would be $413 million.

The cost savings above for a census truncated by date and with 25 percent sampling for nonresponse range from $413 to $468 million, depending on assumptions about the census mail response rate. The panel believes that a redesigned census would best be conducted using a combination of criteria for truncating the 100 percent follow-up of nonrespondents. Using a combination of criteria might result in a longer period of 100 percent follow-up in hard-to-enumerate areas, which would decrease the projected cost savings. The panel's judgment is that cost savings of $300 to $400 million, in 1990 dollars, is a reasonable figure to use for contemplating the effect of truncation with sampling for nonresponse follow-up.

Higher response rates not only reduce the costs of nonresponse follow-up, but also reduce the number of questionnaires that would need to be sampled for follow-up or estimated from a survey to complete the count. However, the use of sampling for follow-up would introduce additional variation in sampling errors among different groups and areas. In assessing the importance of sampling errors, it is important to understand two points: (1) under present techniques, there are significant nonsampling errors for small areas (Appendix L presents information on imputation for missing responses—one type of nonsampling error) and (2) the new census design that the panel recommends will provide more

accurate measures of the population count for the total and for various groups for the nation as a whole and for larger geographic areas.

We have considered a variety of cost estimates, for different times of truncation, different rates of sampling for nonresponse follow-up, and different levels of mail response rates. The panel does not recommend any particular date for truncation, and indeed does not recommend a uniform national truncation date. Nevertheless, based on simulations that could be carried out using 1990 data, it is our belief that cost savings (in 1990 dollars) approaching $300 to $400 million might be achieved in the 2000 census through the use of a shorter period of full-scale follow-up and sampling for nonresponse follow-up.

Recommendation 5.1 The panel recommends that the Census Bureau make a good-faith effort to count everyone, but then truncate physical enumeration after a reasonable effort to reach nonrespondents. The number and characteristics of the remaining nonrespondents should be estimated through sampling.

Survey-Based Methods to Complete the Count

After the return of the mail questionnaire, a reasonable but truncated enumerator follow-up, and the use of sampling for further follow-up, surveys would be used to improve and complete the count. There are various design possibilities for the use of such surveys to estimate census undercoverage used to complete the count. One approach involves a postenumeration survey in which a sample of areas is revisited by specially trained enumerators who try to do a complete census count. This approach is "do it again, but better." A second approach involves an independent survey that is matched to the census to provide net coverage estimates. This survey approach is "do it again, independently."

The 1990 Post-Enumeration Survey followed the second approach of conducting a concurrent independent survey. We present, first, a simple overview of how the PES works to correct for coverage problems in the physical enumeration of the population. In 1990, the PES sample was a resurvey of the population (actually, people living in a sample of areas, in the 1990 design), independent of the census. The results of the PES were matched against census records, providing an estimate of the numbers erroneously included in the census (gross over-count) and a basis for estimating numbers missed from the census (gross undercount).6 For the undercount estimates, let Nc be the number of persons counted in the census, let Np be the number of persons counted in the PES, and let Ncp be the number of persons counted in both. Then, if being counted in the census is independent of being counted in the PES, the probability of being counted in both is the product of the probabilities of being counted in the census and in the PES: Ncp/N = (Nc/N)(Np/N), so that N = NcNp/Ncp, where N is the true population.

The actual conduct of the PES in the 1990 census was somewhat more complicated than just described. The postenumeration survey operation involves finding people who were omitted from the census and deleting people who were included in the census but found to be erroneously enumerated. The postenumeration survey-census match for people, as indicated above, is done for a variety of demographic groups and by selected types of residence. The postenumeration survey counts for a given group (e.g., black women ages 30-44 in urban areas of the Midwest who own their own homes) in the sample areas are compared with the estimated number of similar people obtained in the census. The comparison is used to estimate the net undercount for such people, producing a coverage measurement factor that can be used to correct estimates from other similar areas. The box on page 98 presents more detailed description of the steps that were taken in the PES and the preparation of adjustment factors for dealing with the census undercount. Hogan (1993) discusses the specific operations, methods, and results for the 1990 PES.

There are several important assumptions for the postenumeration survey-type adjustment of the physical enumeration of the census. The first assumption is that the probability of being recorded in the census is the same for each person in the population, and likewise the probability of being recorded in the postenumeration survey is the same for each person in the population. The second assumption is that the probability of a person's being recorded in the postenumeration survey is independent of whether he or she was recorded in the census. The notion of independence in sampling is a statistical one: independence means that the two events (census enumeration and postenumeration survey counting for the sample population) occur without relation to, and with no influence on, the occurrence of the other one. In practice, it means that the postenumeration survey needs to be operationally independent of census operations; it needs to develop its own address lists, to use enumerators who did not canvass the area for the census, and to arrive at its own count of the sample population. The third key assumption for the postenumeration survey is homogeneity (i.e., that each member of the population has an equal chance of being captured in the census enumeration or in the survey). Unfortunately, heterogeneity, or the lack of an equal chance of being in the census or survey, has the same effect as lack of independence, so that the effect of heterogeneity cannot be distinguished from lack of independence.

The 1990 PES calculations were, in practice, carried out for a strata of persons (defined by geographic location, sex, age, ethnicity, place size, and owner/renter status) within which the three key assumptions above are tenable. The 1990 design used 1,392 strata for the coverage estimates. Nonetheless, the existence of a group of people who, because of their residential situation or desire to evade authorities, have zero probability of being counted in the census or the postenumeration survey undermines the assumption of homogeneity and

|

The 1990 Census Correction Process Step 1. An area probability sample of about 5,000 blocks was selected. The "block" was essentially a city block in urban and suburban areas and a well-defined geography in rural areas. Step 2. The 5,000 sample blocks generated two probability samples of people. The "E" or enumeration sample consisted of all persons in the 1990 physical enumeration in those blocks. The "P" or population sample consisted of all persons counted in an independent enumeration of blocks conducted some time following the physical enumeration. Together, the two samples comprised the Post-Enumeration Survey (PES). Step 3. The P sample persons were matched to lists of persons counted in the physical enumeration. The objective was to determine which sample persons were counted in the physical enumeration and which were not. Step 4. Each E sample enumeration was either matched or not matched to a P sample enumeration. E sample enumerations were ultimately designated as correct or erroneous. Step 5. The data were screened for incomplete, missing, or faulty items. All missing data were completed by statistical imputation techniques. Step 6. Estimates of the total population were calculated within each of 1,392 poststrata based, in part, on the characteristics of the PES sample. The poststrata were mutually exclusive and spanned the entire U.S. population. Step 7. The 1,392 ratios, called raw "adjustment factors,'' were "smoothed" to reduce sampling variability. (Smoothed adjustment factors were obtained by shrinking the raw adjustment factors toward a predicted value from a multiple regression model, with the degree of shrinkage determined by the quality of the predictor and the inherent sampling variability in the raw factor.) Step 8. The smoothed adjustment factors were applied to the physical enumeration, block by block, for each of the 7 million blocks in the nation. Source: Fienberg (1992—adapted from Wolter, 1991). |

leads to a downward bias in the postenumeration survey estimate of the undercount.

The 1990 PES was used to produce ratio estimates from the sample of blocks (5,290 block clusters) to the rest of the population. But there were special problems with the 1990 evaluation survey because the sample was too small for use in preparing small-area adjustments and sampling variability led to elaborate forms of statistical smoothing. If plans for a one-number census in 2000 proceed, an adequate sample can be designed that will overcome the special statistical

problems of the 1990 survey. As the Census Bureau moves to implement a census that relies on survey methods to complete the count, it becomes even more important to have a method for coverage adjustment than it was in 1990. A redesigned one-number census will rely on the quality of its evaluation survey.

Alternatives to the postenumeration survey, such as CensusPlus (described below), also take the form of a ratio estimate from a sample of blocks to the nation. The nature of work in those blocks and the statistical estimation within them may be quite different from previous work with the 1990 PES. Alternative methods have different assumptions, and one aspect of the 1995 census test will be to make a comparison between a postenumeration survey estimate and CensusPlus. At the moment, the postenumeration survey has become the standard for census adjustment. The Census Bureau will need to acquire evidence that CensusPlus or some alternative is going to be superior.

Results from the postenumeration survey-type estimation would be used to produce estimates for small areas, down to the level of the individual census blocks, for all population groups throughout the country. The report of the Panel to Evaluate Alternative Census Methods (Steffey and Bradburn, 1994) contains a discussion of the methods that will be required for incorporating people and households into the individual blocks, including the creating of units in such a way that total number of counts for smaller areas equals the counts for larger areas comprising the collection of smaller areas.

The 1990 PES involved 165,000 housing units and identified a net undercount of 1.6 percent and substantial differential undercount related to age, sex, and racial groups and by geographic area. For the 1995 census tests, the Census Bureau currently proposes to use a survey-based method to complete the count, called CensusPlus, that is designed to run concurrently with the main census operations. The CensusPlus method would involve operating a survey behind the regular census operations in the same blocks. CensusPlus would carry out an intensive enumeration in a sample of blocks with the objective of obtaining a complete enumeration of the population. The assumption of complete coverage for CensusPlus would then be used for comparisons with the census enumeration to derive correction factors. But no final decision has been made about the survey method that would be used to complete the census count in the 2000 census. The PES was used in 1990 and much is known about its operational feasibility and costs; tests with CensusPlus in 1995 will provide comparable information about this alternative.

Whether a postenumeration survey, CensusPlus, or some combination of the two survey designs is used in the 2000 census, it is important to emphasize that its principal use is to complete the census—i.e., that the survey is not designed to evaluate the census but is an integral part of the census. This is a fundamental departure—it is the only feasible approach largely to eliminate the differential undercounts historically observed in U.S. censuses. Furthermore, the approach can serve as a springboard for a complete reengineering of the enumeration-based

part of the census. Indeed, traditionally the enumeration had to carry the full burden of producing a complete census. Using only physical enumeration resulted in a variety of extremely intensive and costly approaches, particularly when used in combination. Knowing that the count resulting from physical enumeration (with sample follow-up of nonrespondents) will be completed by a final survey should permit the Census Bureau to redesign all preceding operations with a view to reducing reliance on the less cost-effective approaches to enumeration. Indeed, as we've said, we are advocating a complete reengineering. We shall return to this point in the last two sections of this chapter.

A survey-based method to complete the count has several benefits for the redesigned census. A major one is reduced costs. The traditional census has, in recent decades, increased the use of intensive enumeration efforts in a futile attempt to physically count every person. This effort has produced diminishing returns. Trying to directly enumerate everyone in a large and diverse population has become prohibitively expensive, yet it is unlikely that spending more money will reduce net overall or differential undercoverage. A less expensive approach is to realize that modern statistical methods can assist in improving the census count and to rely on those methods for future U.S. censuses, thereby reducing the intensive follow-up effort that was used in the previous two censuses.

The second benefit of integrated statistical estimation is improved accuracy with respect to the count and differential undercount for the nation as a whole as well as large areas and groups. Using high-quality special surveys to complete the count will enable the Census Bureau to use data-quality enhancements (e.g., intensive efforts to find hard-to-enumerate persons) that would be too expensive to use for the entire population. Such a high-quality survey can then be used to estimate the number and characteristics of the people missed by the census and take them into account in completing the official count.

Although the use of statistical methods to complete the census count will increase variability for very small areas, there will be benefits from cost savings and improved overall coverage. Whatever the adjustment factors used in an integrated coverage measurement system, the adjustments will become much coarser as geographic detail becomes smaller. There is fervent debate among demographers and statisticians about the best methods to be used for completing the census count for small geographic areas. We note that the conventional 1990 census approach also produces large variability for small-area estimates (as described earlier). The panel believes that further work on the census methods to be used for producing small-area estimates is needed before a decision should be made.

The Census Bureau has published, for each modern census in the past 50 years, a comprehensive description of the procedures followed in enumerating the population, together with an assessment of the quality of the data. Separate census publications routinely note nonresponse rates and information on allocation rules and rates (Appendix L provides an example of allocation information

from the 1990 census, cited in this report for our panel's examination of the quality of data on race and ethnicity). The panel urges the Census Bureau to continue this tradition of conscientious documentation of census procedures and to provide for the redesigned 2000 census the materials needed for proper use of census data and for independent scrutiny of the accuracy of census data.

Recommendation 5.2 To improve the census results, and especially to reduce the differential undercount, the panel recommends that the estimates achieved through physical enumeration and sampling for nonresponse be further improved and completed through survey techniques. The census should be designed as an integrated whole, to produce the best single-number count for the resources available. The Census Bureau should publish the procedures used to produce its final counts, as well as an assessment of their accuracy.

ADDITIONAL MEASURES TO IMPROVE ACCURACY AND REDUCE COSTS

Improve Response Rates

Research by the Census Bureau in recent years provides evidence that the mail response rates to the census questionnaire can be improved, compared with the 1990 experience. Work with the Simplified Questionnaire Test and the Appeals and Long-Form Experiment suggest several improvements: respondent-friendly questionnaires, pre-and post-mailout reminders, use of replacement questionnaires, use of appeals to the mandatory nature of the census, and telephone reminders. Taken together, these changes could significantly improve the mail response rates for the 2000 census. Although the panel is not able to provide a specific estimate of the mail response rate for the 2000 census (none of these improvements has yet been used in a census environment), we believe that these improvements would at least halt the decline in census mail response rates in recent censuses.

A Simplified Questionnaire Design

Work on the SQT conducted by the Census Bureau in early 1992 was designed to address issues in relation to response rates for the short form. Chapter 6 discusses the results of the SQT tests.

Results from the SQT confirm that changes in the short-form content, design, and collection procedures can improve census response rates. Higher response rates reduce the need for follow-up interviews, including the time for follow-up interviewing and the training time for more interviewers. However, the use of replacement questionnaires—and other measures to improve response

rates—incur additional costs that need to be considered when weighing the benefits from higher response rates. Additional costs involve the mailing and printing costs of a reminder postcard or a replacement questionnaire, the possibly higher costs of printing and processing a respondent-friendly census questionnaire, and the use of telephone calls to urge nonrespondents to mail in their questionnaires. There may be additional costs to respondent-friendly forms that may increase machine costs for processing and tabulation. Optimizing for respondent ease may increase response rates, but it may also increase machine costs. All extra costs must be weighed against the cost savings from increased mail response rates. Some methods to increase mail response rates may not, after careful study, yield an overall net cost savings.

Respondent-Friendly Long Forms and the Use of Appeals

The Census Bureau conducted the Appeals and Long-Form Experiment in 1993 with two objectives: to determine the influence of two types of respondent-friendly construction on response rates for the census long form and to determine the influence of three types of appeals on response rates to the census short form. The ALFE work involved the use of methods to improve mail response rates that had been learned from the SQT. Results from the ALFE test are described in greater detail in Chapter 6.

The ALFE research leads to two conclusions for taking the census. First, it is possible to improve the census long form by designing it as a more respondent-friendly questionnaire. Second, stressing the mandatory nature of the census ("Your response is required by law") substantially improves the mail completion rates. Although the ALFE study did not test directly the use of a mandatory appeal with the long form, the results suggest that it may be possible to increase the long-form mail completion rates by as much as 15 percentage points by using a respondent-friendly questionnaire and stressing the mandatory and confidential nature of the census.

Recommendation 5.3 The panel recommends that the Census Bureau incorporate successfully tested procedures to increase the initial response rate in the 2000 census, including respondent-friendly questionnaires and expanded efforts to publicize the mandatory nature of the census.

Partnerships with State and Local Governments

In rethinking census operations for the future, the Census Bureau needs to develop new partnerships. One of the two most important partnerships needed is with state and local governments. The other is with the U.S. Postal Service, discussed in the next section.

The Census Bureau needs to work with state and local governments to improve understanding of the new methods for the 2000 census, changes in census enumeration operations, and the use of integrated coverage measurement. The 2000 census will have different methods for coverage improvement, with a decreased reliance on intensive and expensive direct enumeration. Local and state governments need to be informed about these new approaches and to understand how they will affect census operations in their areas. Congress should evaluate the Census Bureau for its success in establishing cooperative state and local programs.